Lapping Quality Prediction of Ceramic Fiber Brush Based on Gaussian-Restricted Boltzmann Machine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Prediction Model of Brush-Lapping Quality

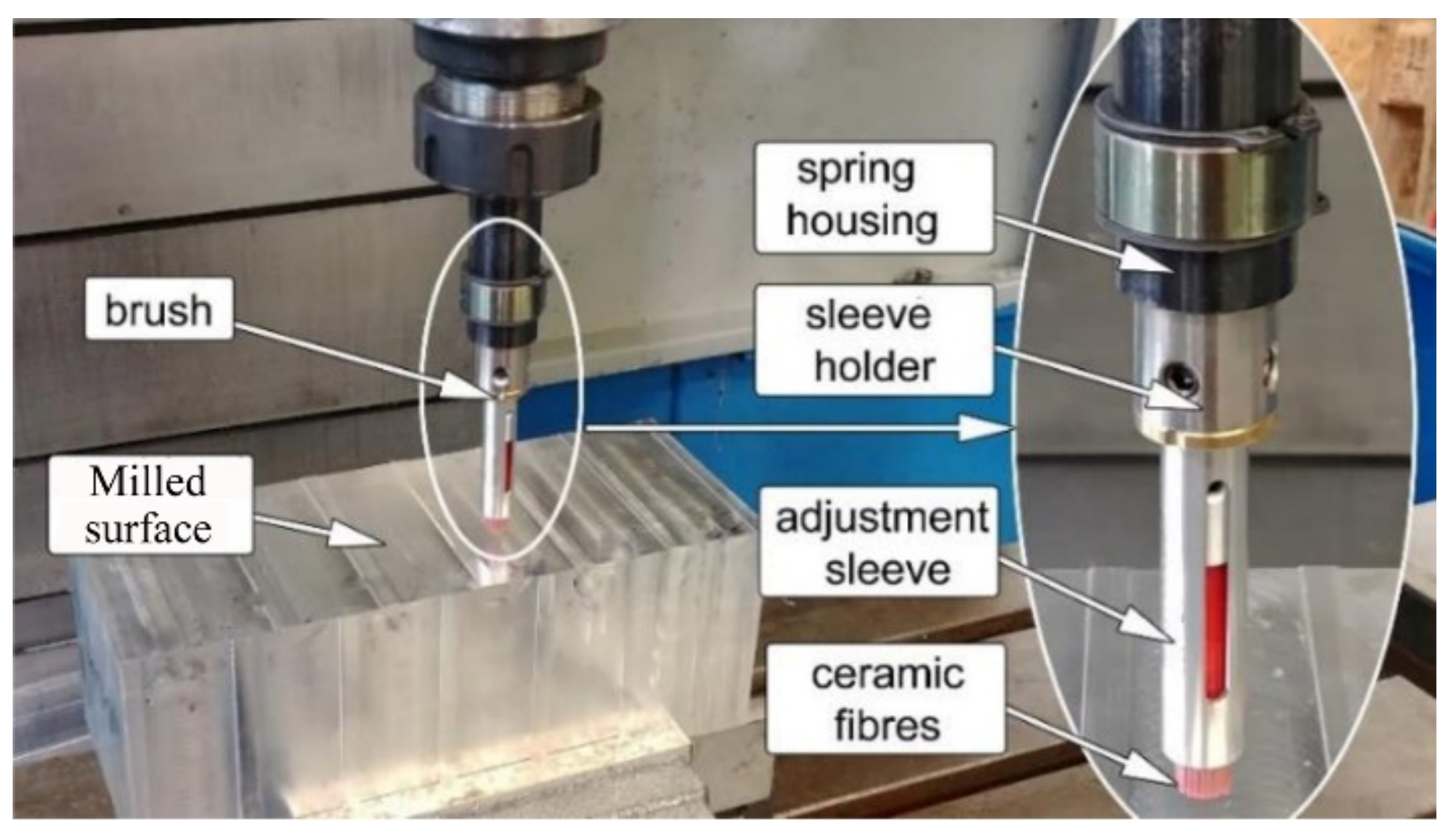

2.1. Lapping Experiment of Ceramic Fiber Brush

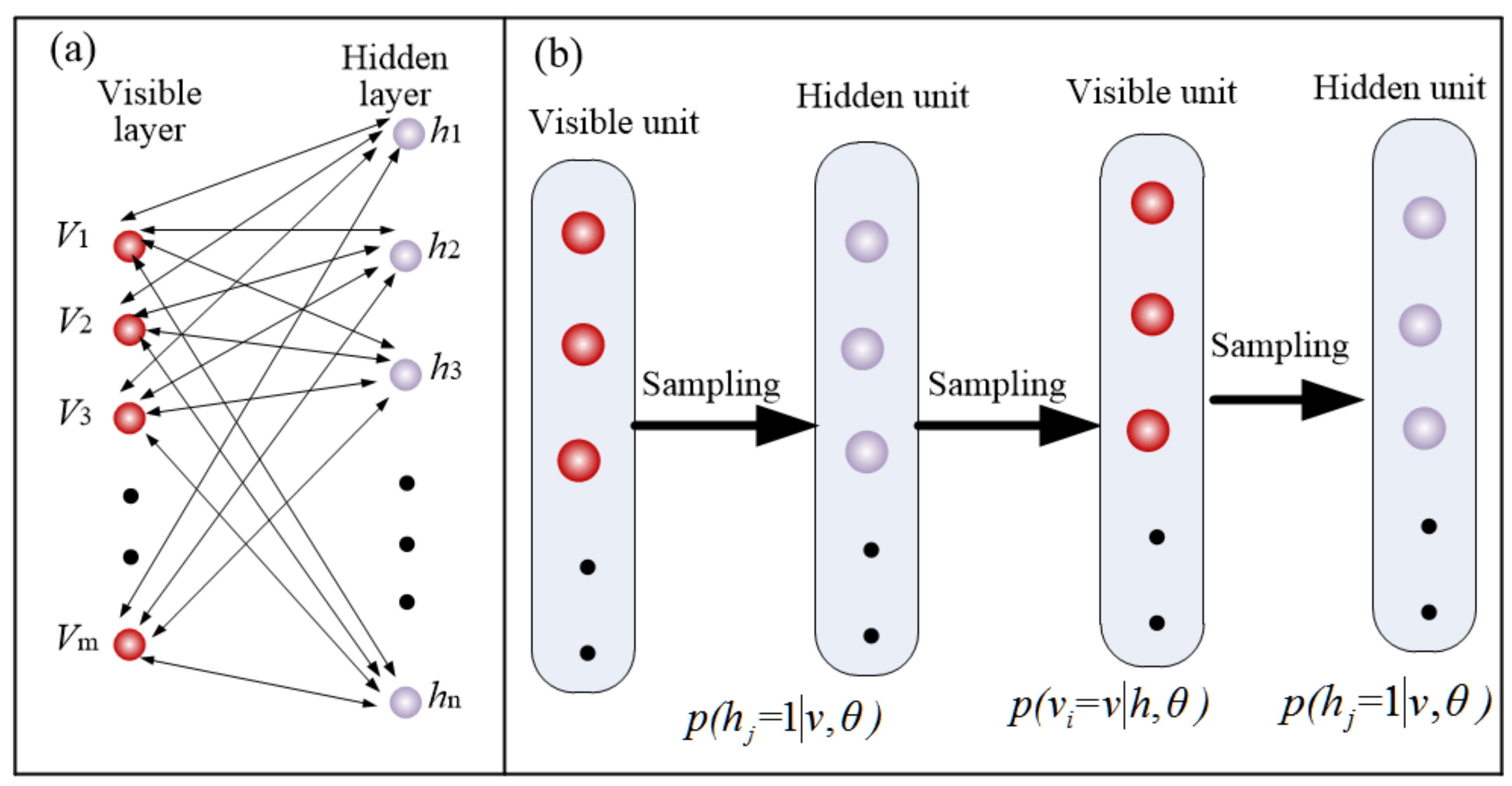

2.2. Prediction Model Based on Gaussian-Restricted Boltzmann Machine

2.2.1. Structure Design of the Prediction Model

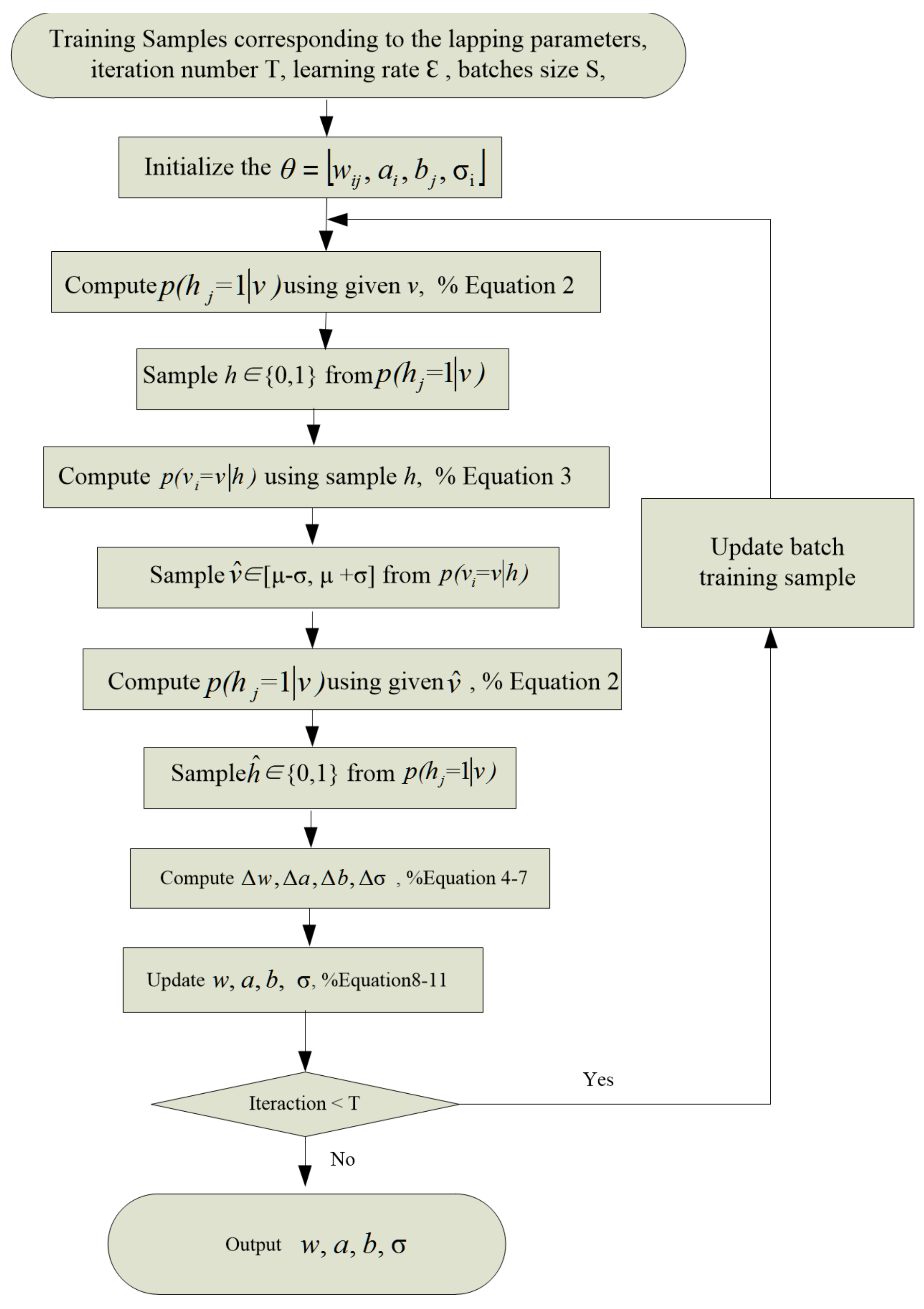

2.2.2. Pretraining Process of Gaussian-Restricted Boltzmann Machine

2.2.3. Fine-Tuning Process

3. Results and Discussion

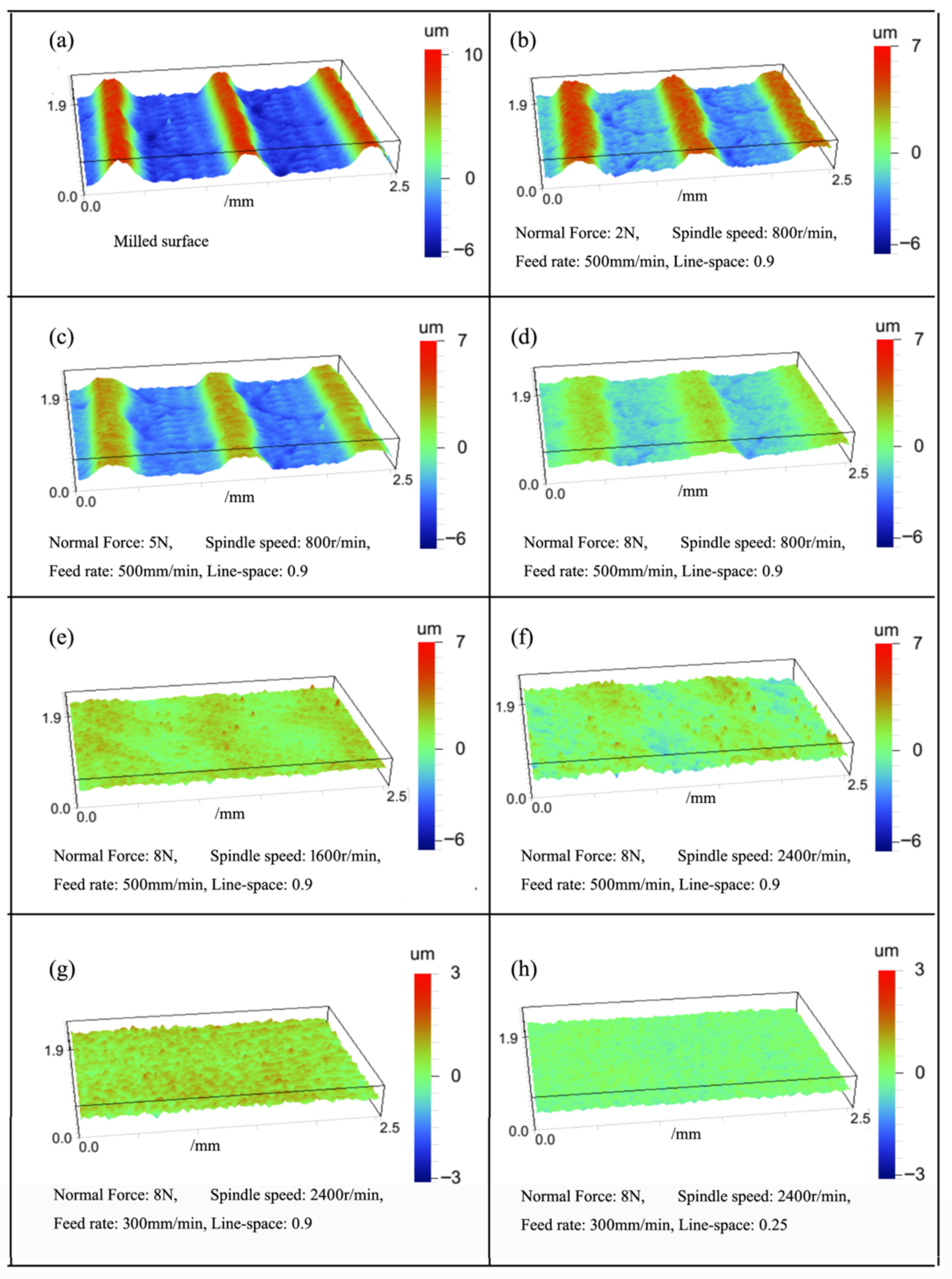

3.1. The Experiment Result

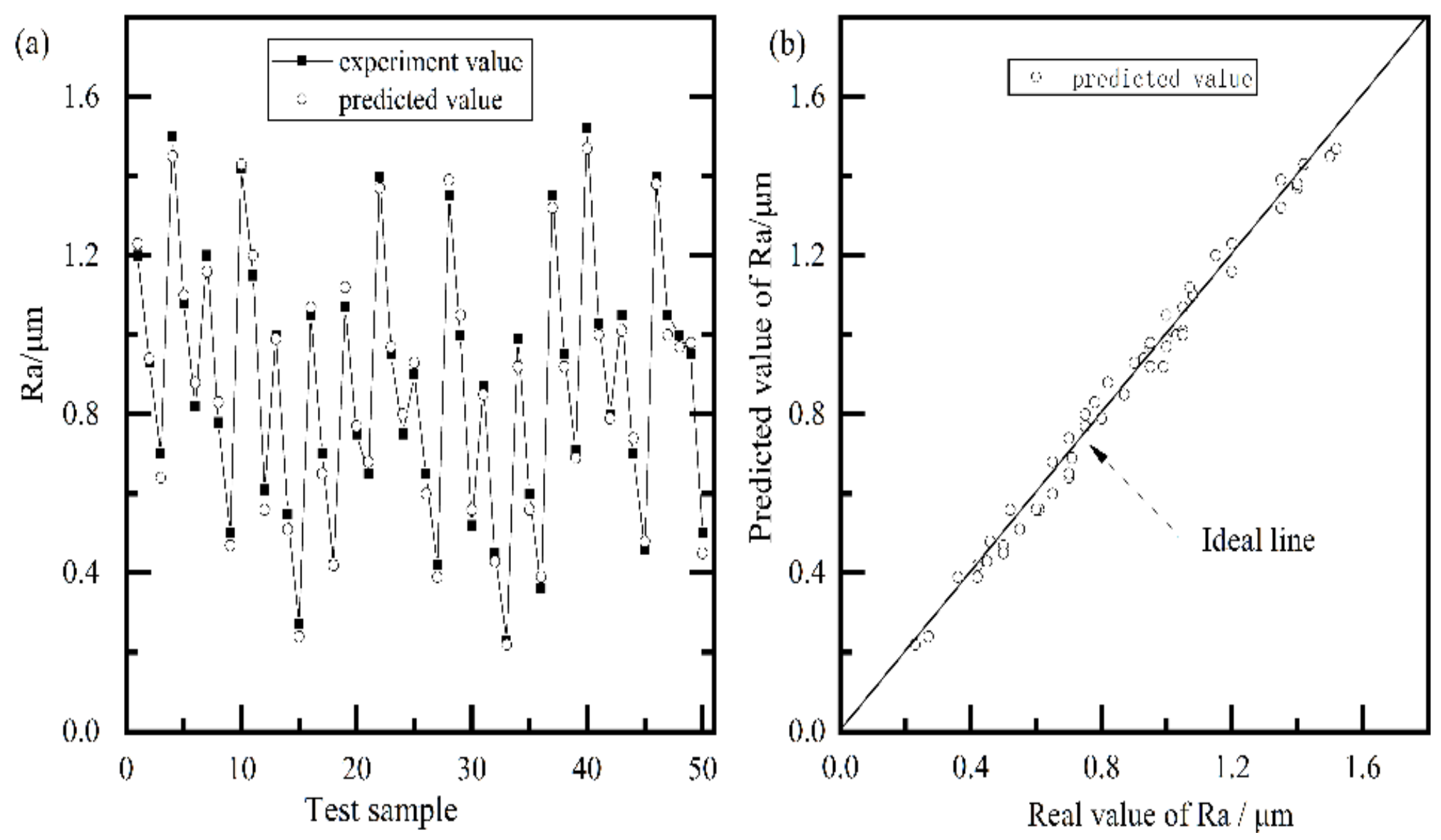

3.2. Network Training and Prediction Performance

4. Conclusions

- During the brush lapping of aluminum alloy, the surface roughness decreased with the increasing of normal force and spindle speed, and increased with the increasing of the feed rate and line-space. Moreover, the minimum of surface roughness can be reduced to 0.24 μm.

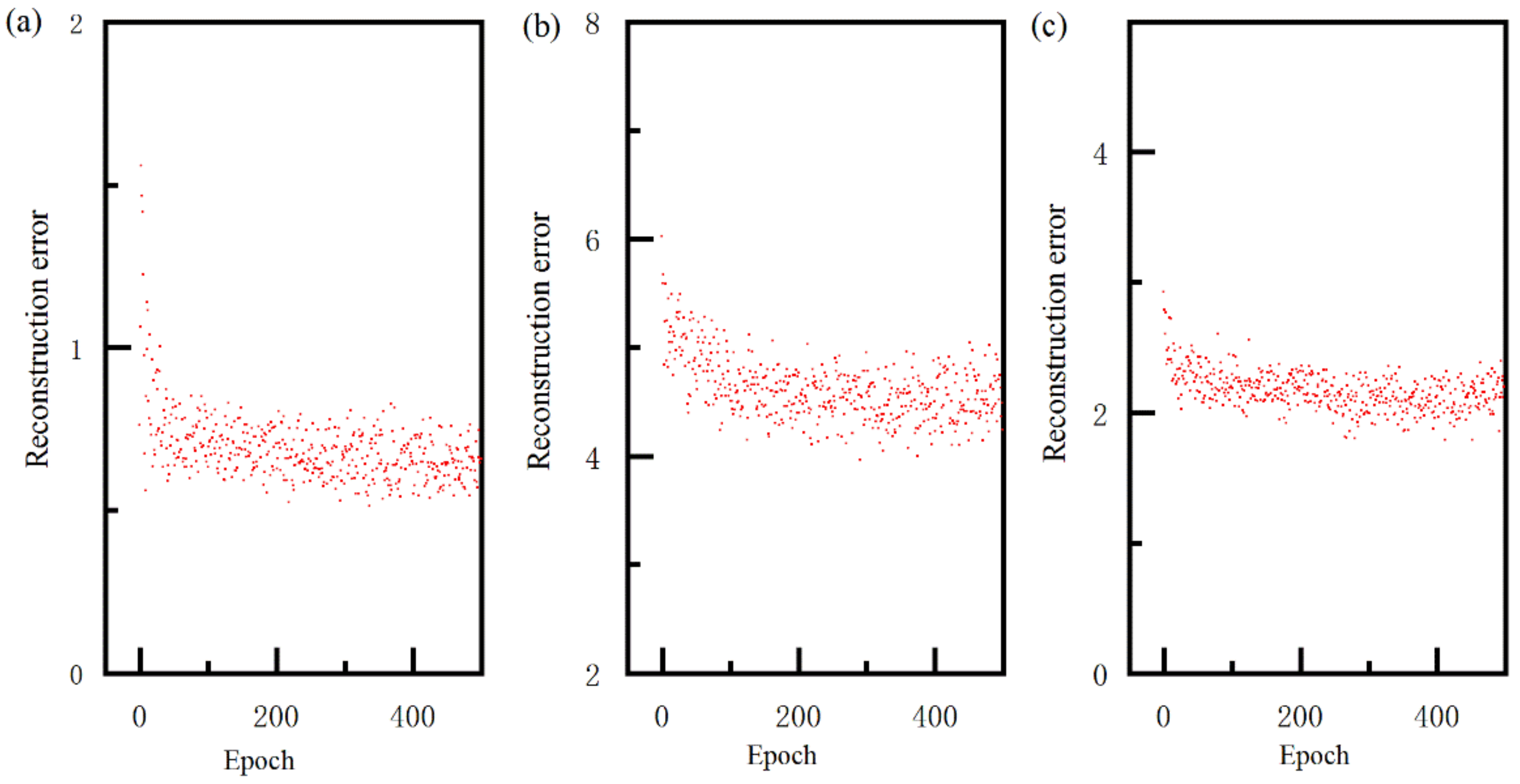

- In the unsupervised pre-training stage, the reconstruction error of GRBM decreased with an increase in epoch, and minorly changed when the epoch was larger than the 100th.

- Compared with the BP neural network, the prediction error of the proposed model was reduced from 7.6% to 4.5%, and the R2 was increased from 0.96 to 0.98, respectively, showing the better performance of generalization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Process parameters | Measure Value Ra /μm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter /mm | Spindle Speed /r/min | Feed Rate /mm/min | Line-Space | Normal Force /N | ||

| 1 | 25 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 2 | 1.32 |

| 2 | 25 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.55 |

| 3 | 25 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.42 |

| 4 | 25 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 11 | 0.60 |

| 5 | 25 | 800 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 1.25 |

| 6 | 25 | 2400 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.29 |

| 7 | 25 | 3200 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.32 |

| 8 | 25 | 2400 | 700 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.86 |

| 9 | 25 | 2400 | 500 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.59 |

| 10 | 25 | 2400 | 100 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.29 |

| 11 | 25 | 2400 | 300 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.32 |

| 12 | 25 | 2400 | 300 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.40 |

| 13 | 25 | 2400 | 300 | 0.9 | 8 | 0.52 |

| 14 | 40 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 2 | 1.55 |

| 15 | 40 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.78 |

| 16 | 40 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.55 |

| 17 | 40 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 11 | 0.54 |

| 18 | 40 | 800 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 1.1 |

| 19 | 40 | 2400 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.31 |

| 20 | 40 | 3200 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.29 |

| 21 | 40 | 2400 | 700 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.66 |

| 22 | 40 | 2400 | 500 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.43 |

| 23 | 40 | 2400 | 100 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.28 |

| 24 | 40 | 2400 | 300 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.24 |

| 25 | 40 | 2400 | 300 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.37 |

| 26 | 40 | 2400 | 300 | 0.9 | 8 | 0.40 |

| 27 | 60 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 2 | 1.62 |

| 28 | 60 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 5 | 1.23 |

| 29 | 60 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.80 |

| 30 | 60 | 1600 | 300 | 0.5 | 11 | 0.65 |

| 31 | 60 | 800 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 1.0 |

| 32 | 60 | 2400 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.38 |

| 33 | 60 | 3200 | 300 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.31 |

| 34 | 60 | 2400 | 700 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.93 |

| 35 | 60 | 2400 | 500 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.78 |

| 36 | 60 | 2400 | 100 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.29 |

| 37 | 60 | 2400 | 300 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.32 |

| 38 | 60 | 2400 | 300 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.45 |

| 39 | 60 | 2400 | 300 | 0.9 | 8 | 0.55 |

| No | Process Parameters | Measured Value Ra/μm | Predicted Value Ra/μm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter/mm | Spindle Speed /r/min | Feed Rate /mm/min | Line-Space | Normal Force /N | |||

| 1 | 25 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 3 | 1.20 | 1.23 |

| 2 | 25 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| 3 | 25 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.70 | 0.64 |

| 4 | 25 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 3 | 1.50 | 1.45 |

| 5 | 25 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 6 | 1.08 | 1.10 |

| 6 | 25 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| 7 | 25 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.20 | 1.16 |

| 8 | 25 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.78 | 0.83 |

| 9 | 25 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.50 | 0.47 |

| 10 | 25 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.42 | 1.43 |

| 11 | 25 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 6 | 1.15 | 1.20 |

| 12 | 25 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.61 | 0.56 |

| 13 | 25 | 2800 | 200 | 0.3 | 4 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| 14 | 25 | 2800 | 200 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| 15 | 25 | 2800 | 200 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.29 | 0.24 |

| 16 | 25 | 2800 | 400 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.05 | 1.07 |

| 17 | 25 | 2800 | 400 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.70 | 0.65 |

| 18 | 25 | 2800 | 400 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| 19 | 40 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 4 | 1.07 | 1.12 |

| 20 | 40 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.75 | 0.77 |

| 21 | 40 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.65 | 0.68 |

| 22 | 40 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 4 | 1.40 | 1.37 |

| 23 | 40 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| 24 | 40 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.75 | 0.80 |

| 25 | 40 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

| 26 | 40 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.65 | 0.60 |

| 27 | 40 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| 28 | 40 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.35 | 1.39 |

| 29 | 40 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 6 | 1.00 | 1.05 |

| 30 | 40 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.52 | 0.56 |

| 31 | 40 | 2800 | 200 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.87 | 0.85 |

| 32 | 40 | 2800 | 200 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| 33 | 40 | 2800 | 200 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.28 | 0.27 |

| 34 | 40 | 2800 | 400 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.99 | 0.92 |

| 35 | 40 | 2800 | 400 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.60 | 0.56 |

| 36 | 40 | 2800 | 400 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.36 | 0.39 |

| 37 | 60 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 3 | 1.35 | 1.32 |

| 38 | 60 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.95 | 0.92 |

| 39 | 60 | 1200 | 200 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| 40 | 60 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 3 | 1.52 | 1.47 |

| 41 | 60 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 6 | 1.03 | 1.00 |

| 42 | 60 | 1200 | 400 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| 43 | 60 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.05 | 1.01 |

| 44 | 60 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.70 | 0.74 |

| 45 | 60 | 2000 | 200 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| 46 | 60 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.40 | 1.38 |

| 47 | 60 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 6 | 1.05 | 1.00 |

| 48 | 60 | 2000 | 400 | 0.6 | 9 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| 49 | 60 | 2800 | 200 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

| 50 | 60 | 2800 | 200 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.50 | 0.45 |

References

- Mathai, G.; Melkote, S. Effect of process parameters on the rate of abrasive assisted brush deburring of microgrooves. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Manu. 2012, 57, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai, G.; Melkote, S.; Rosen, D. Material removal during abrasive impregnated brush deburring of micromilled grooves in NiTi foils. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Manu. 2013, 72, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Liu, K. Experimental investigation of surface integrity during abrasive edge profiling of nickel-based alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2019, 39, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, N.; Hill, S.; Soshi, M. Characterization of surface polishing with spindle mounted abrasive disk-type filament tool for manufacturing of machine tool sliding guideways. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tec. 2016, 86, 2069–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, R.; Soshi, M. Surface polishing of hardened grey cast iron with a compliant abrasive filament tool. Procedia Cirp. 2016, 46, 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Novotný, F.; Horák, M.; Starý, M. Abrasive cylindrical brush behaviour in surface processing. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Manu. 2017, 118, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stary, M.; Novotny, F.; Horak, M.; Stara, M.; Hotar, V.; Matusek, O. Summary of the properties and benefits of glass mechanically frosted with an abrasive brush. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 206, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, C.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, L. Numerical and experimental research on the brushing aluminium alloy mechanism using an abrasive filament brush. Materials 2021, 14, 6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierlak, P. The manipulator tool state classification based on inertia forces analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 2018, 107, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierlak, P.; Burghardt, A.; Szybicki, D.; Szuster, M.; Muszyńska, M. On-line manipulator tool condition monitoring based on vibration analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 2017, 89, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulisze, M.; Zagórski, I.; Matuszak, J.; Kłonica, M. Properties of the surface layer after trochoidal milling and brushing experimental study and artificial neural network simulation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszak, J.; Kłonica, M.; Zagórski, I. Measurements of forces and selected surface layer properties of AW-7075 aluminum alloy used in the aviation industry after abrasive machining. Materials 2019, 12, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.K. Investigation of surface uniformity machined by ceramic brush. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tec. 2017, 94, 2593–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhakumar, J.; Iqbal, U.M. Role of trochoidal machining process parameter and chip morphology studies during end milling of AISI D3 steel. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, T.; Feng, P.; Wei, S.; Zhao, H. Investigation on surface morphology model of Si3N4 ceramics for rotary ultrasonic grinding machining based on the neural network. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 396, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Yan, Y.; Guo, D. Activation functions selection for BP neural network model of ground surface roughness. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1825–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Wang, J.; Gao, H.; Yang, L.; Xiao, P. Optimization of lapping process parameters of CP-Ti based on PSO with mutation and BPNN. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 117, 2859–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Liu, L.; Wu, B.; Gao, Y.; Qu, D. Process optimization of high-speed dry milling UD-CF/PEEK laminates using GA-BP neural network. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2021, 221, 109034–109049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Effects of process parameters on cutting temperature in dry machining of ball screw. ISA T. 2020, 101, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, T.; Xu, P.; Zhao, J. An intelligent sustainability evaluation system of micro milling. Robot. Cim-Int. Manuf. 2022, 73, 102239–102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gza, B.; Xu, Y. Efficient face detection and tracking in video sequences based on deep learning—ScienceDirect. Inform. Sci. 2021, 568, 265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Deng, L.; Wang, B.; Li, G.; Xie, Y. A comprehensive and modularized statistical framework for gradient norm equality in deep neural networks. IEEE. Trans. Pattern. Anal. 2020, 44, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Ding, S.; Zhang, J.; Xue, Y. An overview on restricted boltzmann machines. Neurocomputing 2018, 275, 1186–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Sun, S. Multi view graph restricted boltzmann machines. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 12414–12428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Liu, G. Knowledge-based deep belief network for machining roughness prediction and knowledge discovery. Comput. Ind. 2020, 121, 103262–103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Gu, Y.; Wang, Y. Supervised deep belief network for quality prediction in industrial processes. IEEE. Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 2503711–2503722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, N.; Scippa, A.; Sallese, L.; Montevecchi, F.; Campatelli, G. On the generation of chatter marks in peripheral milling: A spectral interpretation. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Manu. 2018, 133, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Ni, J.; He, L.; Cui, Z.; Feng, K. Influence of micro-structured milling cutter on the milling load and surface roughness of 6061 aluminum alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 110, 3201–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Zhu, L.-M. Wall thickness error prediction and compensation in end milling of thin-plate parts. Precis. Eng. 2020, 66, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Han, D.; Li, K.-C.; Liu, X.; Duan, L.; Castiglione, A. An intrusion detection approach based on improved deep belief network. Appl. Intell. 2020, 50, 3162–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosarac, A.; Mladjenovic, C.; Zeljkovic, M.; Tabakovic, S.; Knezev, M. Neural-network-based approaches for optimization of machining parameters using small dataset. Materials 2022, 15, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Brush Diameter /mm | Spindle Speed /r/min | Feed Rate /mm/min | Line-Space /Pitches/Diameter | Normal Force /N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 800 | 100 | 0.25 | 2 |

| 2 | 40 | 1600 | 300 | 0.50 | 5 |

| 3 | 60 | 2400 | 500 | 0.75 | 8 |

| 4 | - | 3200 | 700 | 0.9 | 11 |

| No | Process Parameters | Replicate | Average Ra µm | Standard Deviation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Force N | Spindle Speed r/min | Feed Rate mm/min | Line-Space | Diameter mm | Ra 1 µm | Ra 2 µm | Ra 3 µm | Ra 4 µm | Ra 5 µm | |||

| 1 | 2 | 800 | 100 | 0.25 | 25 | 1.94 | 1.95 | 2.07 | 2.05 | 1.99 | 2.00 | 0.039 |

| 2 | 2 | 1600 | 500 | 0.90 | 40 | 1.81 | 1.75 | 1.80 | 1.84 | 1.77 | 1.79 | 0.044 |

| 3 | 2 | 2400 | 700 | 0.50 | 60 | 1.32 | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.39 | 1.35 | 1.35 | 0.041 |

| 4 | 2 | 3200 | 300 | 0.75 | 25 | 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.16 | 1.09 | 1.10 | 0.045 |

| 5 | 5 | 800 | 300 | 0.50 | 40 | 1.43 | 1.48 | 1.45 | 1.49 | 1.45 | 1.46 | 0.034 |

| 6 | 5 | 1600 | 700 | 0.75 | 25 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.049 |

| 7 | 5 | 2400 | 500 | 0.25 | 25 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.034 |

| 8 | 5 | 3200 | 100 | 0.90 | 60 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.028 |

| 9 | 8 | 800 | 500 | 0.75 | 60 | 1.27 | 1.23 | 1.21 | 1.31 | 1.23 | 1.25 | 0.009 |

| 10 | 8 | 1600 | 100 | 0.50 | 25 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.038 |

| 11 | 8 | 2400 | 300 | 0.90 | 25 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.025 |

| 12 | 8 | 3200 | 700 | 0.25 | 40 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.031 |

| 13 | 11 | 800 | 700 | 0.90 | 25 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.036 |

| 14 | 11 | 1600 | 300 | 0.25 | 60 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.034 |

| 15 | 11 | 2400 | 100 | 0.75 | 40 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.026 |

| 16 | 11 | 3200 | 500 | 0.50 | 25 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.034 |

| Source | DOF | Sum of Squares | Variance | F-Value | p | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal force | 3 | 2.367 | 0.789 | 63108 | 0.003 | Yes |

| Spindle speed | 3 | 1.438 | 0.479 | 38345 | 0.004 | Yes |

| Feed rate | 3 | 0.161 | 0.054 | 4296 | 0.011 | Yes |

| Line-space | 3 | 0.021 | 0.007 | 566 | 0.031 | Yes |

| Diameter | 2 | 0.077 | 0.038 | 3073 | 0.013 | Yes |

| Error | 1 | 0.00012 | 0.00012 | - | - | - |

| Total | 16 | 18.126 | - | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, X.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Sun, Q. Lapping Quality Prediction of Ceramic Fiber Brush Based on Gaussian-Restricted Boltzmann Machine. Materials 2022, 15, 7805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217805

Yuan X, Wang C, Li M, Sun Q. Lapping Quality Prediction of Ceramic Fiber Brush Based on Gaussian-Restricted Boltzmann Machine. Materials. 2022; 15(21):7805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217805

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Xiuhua, Chong Wang, Mingqing Li, and Qun Sun. 2022. "Lapping Quality Prediction of Ceramic Fiber Brush Based on Gaussian-Restricted Boltzmann Machine" Materials 15, no. 21: 7805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217805

APA StyleYuan, X., Wang, C., Li, M., & Sun, Q. (2022). Lapping Quality Prediction of Ceramic Fiber Brush Based on Gaussian-Restricted Boltzmann Machine. Materials, 15(21), 7805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217805