Overview of Materials Used for the Basic Elements of Hydraulic Actuators and Sealing Systems and Their Surfaces Modification Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

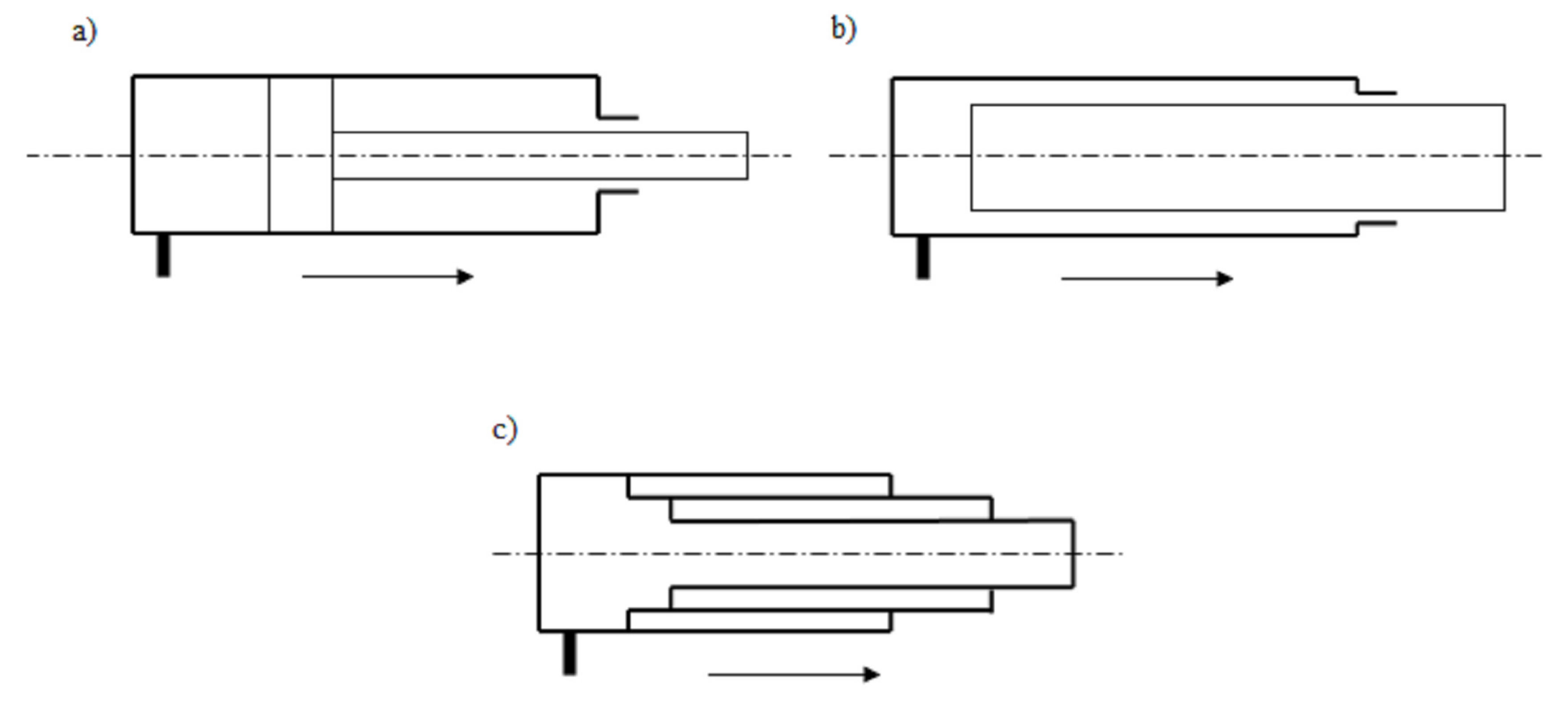

- piston actuator;

- plunger actuator;

- telescopic actuator.

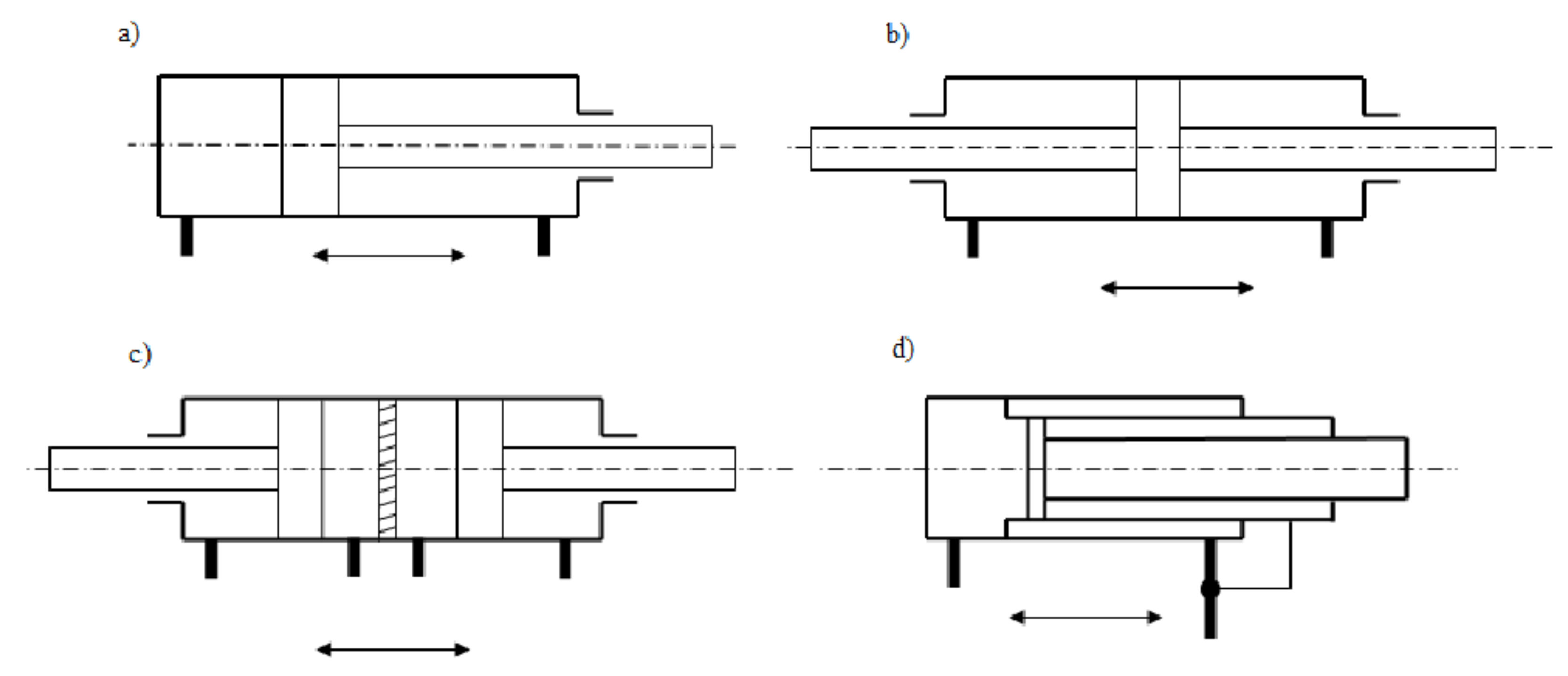

- piston actuator with one piston rod (with one-sided piston rod);

- piston actuator with two-piston rods (with double-sided piston rod);

- multi-piston actuator;

- telescopic actuator.

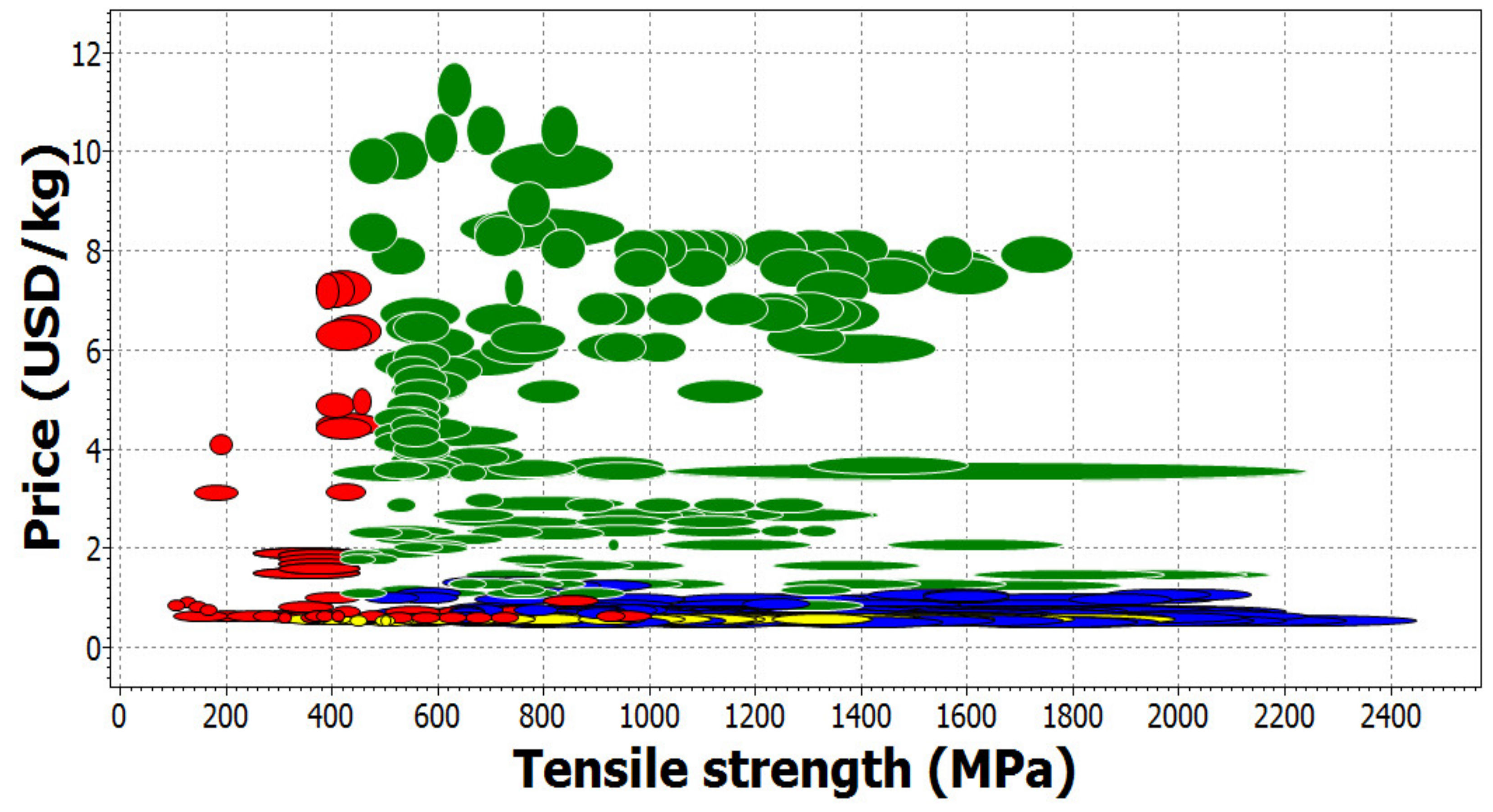

2. Selection of the Appropriate Material and Its Influence on the Operation and Durability of the Hydraulic Actuator

3. Failures of Hydraulic Actuators

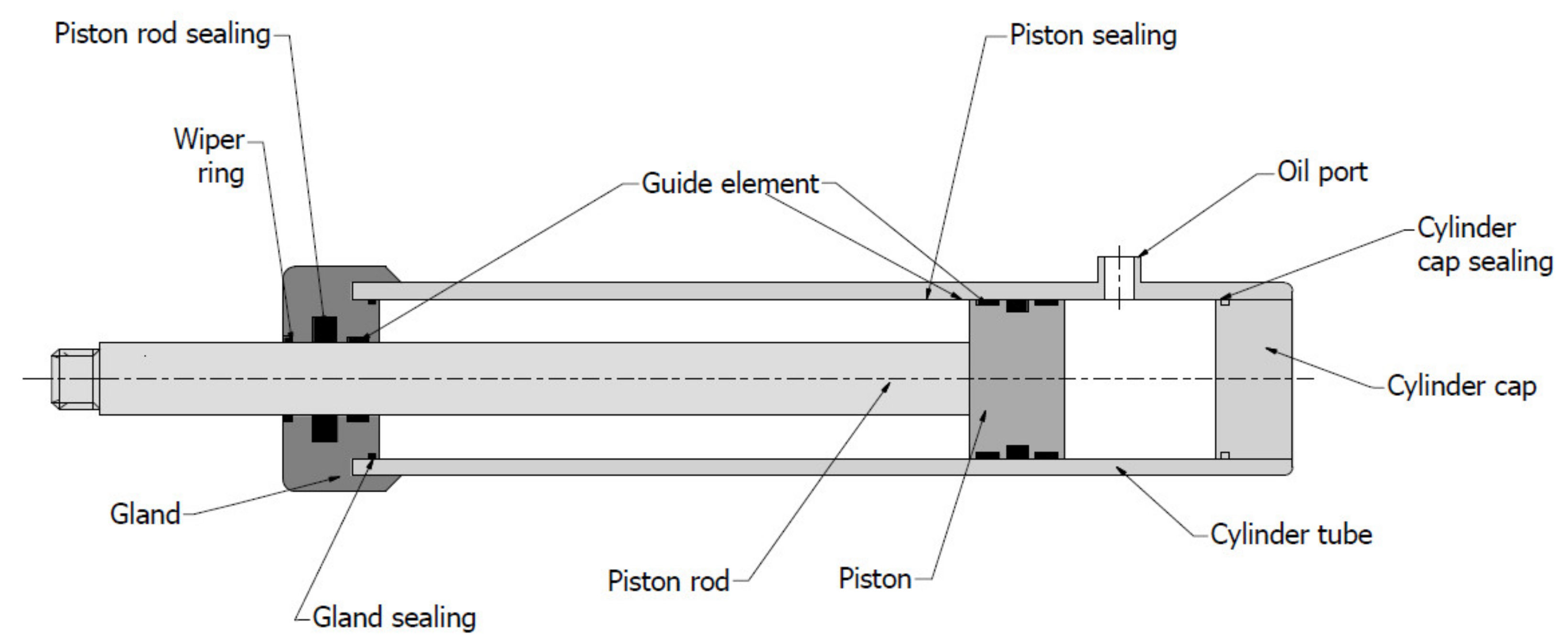

3.1. Failures of Cylinders

3.2. Failures of Piston Rods and Pistons

3.3. Failures of End Caps and Glands

3.4. Failures of Sealing Systems

4. Materials and Surface Modifications Used for Hydraulic Actuator Elements

4.1. Cylinders

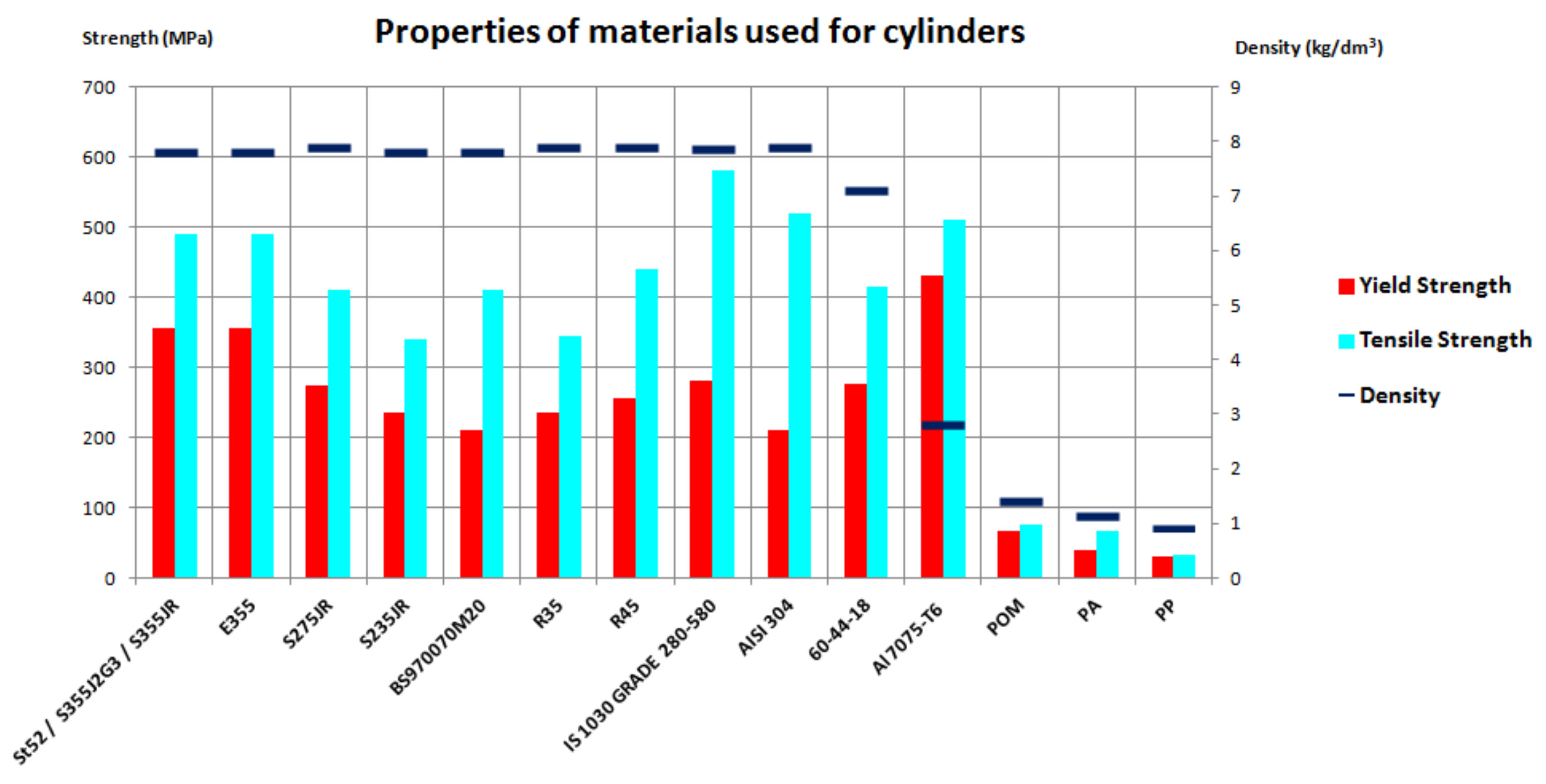

4.1.1. Materials Used for Cylinders

4.1.2. Surface Modifications of Cylinder

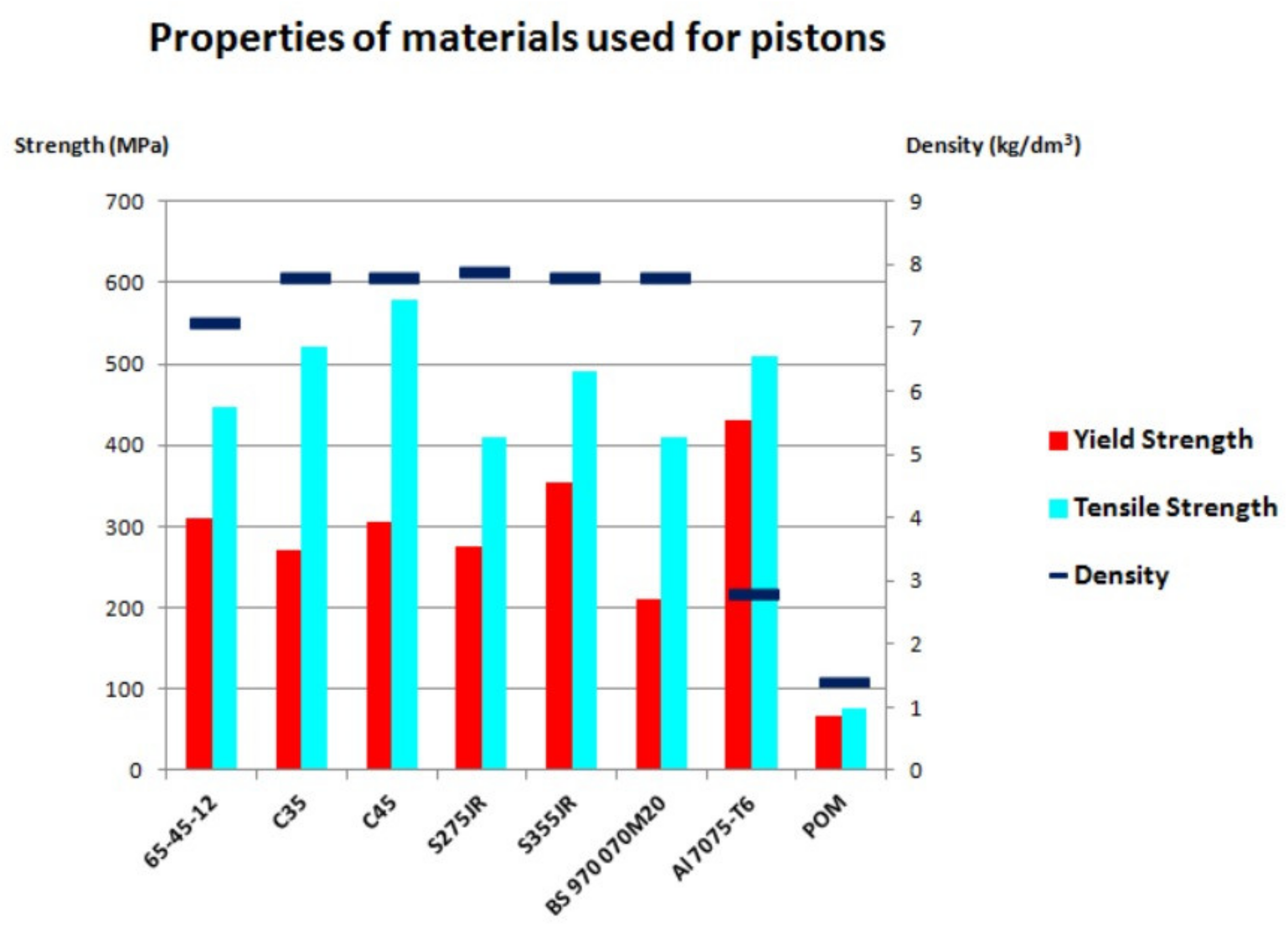

4.2. Pistons

4.3. Piston Rods

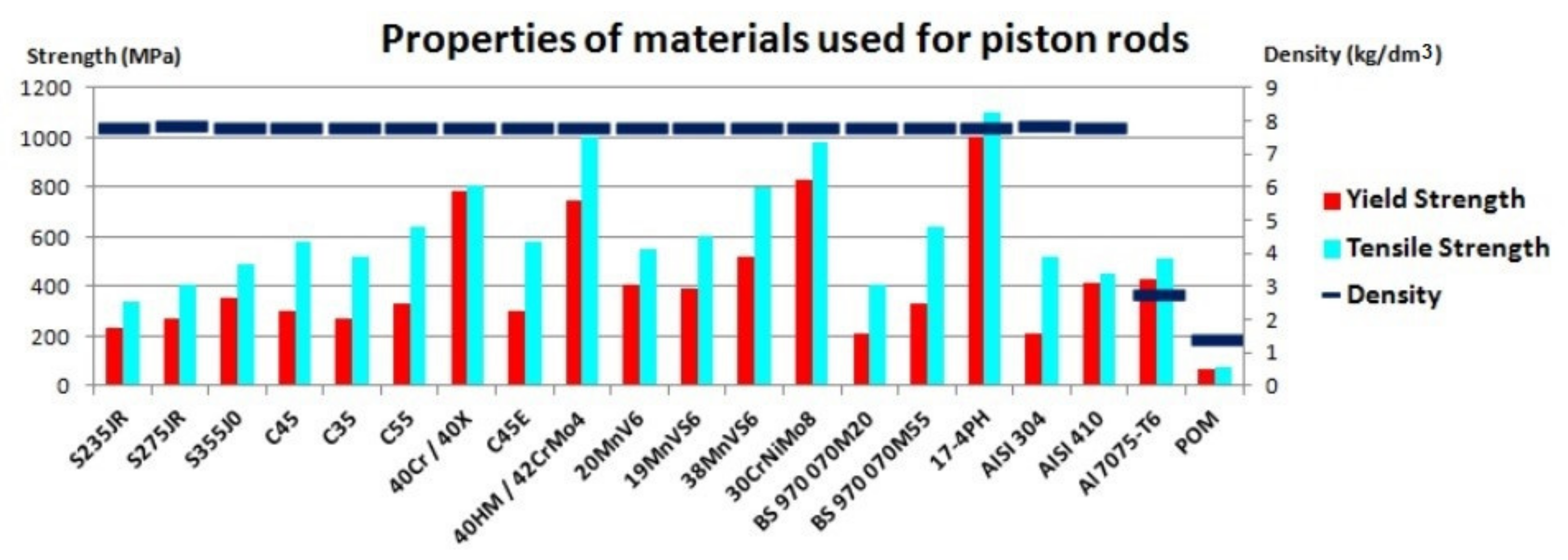

4.3.1. Materials Used for Piston Rods

4.3.2. Surface Modifications of Piston Rods

4.4. End Caps and Glands

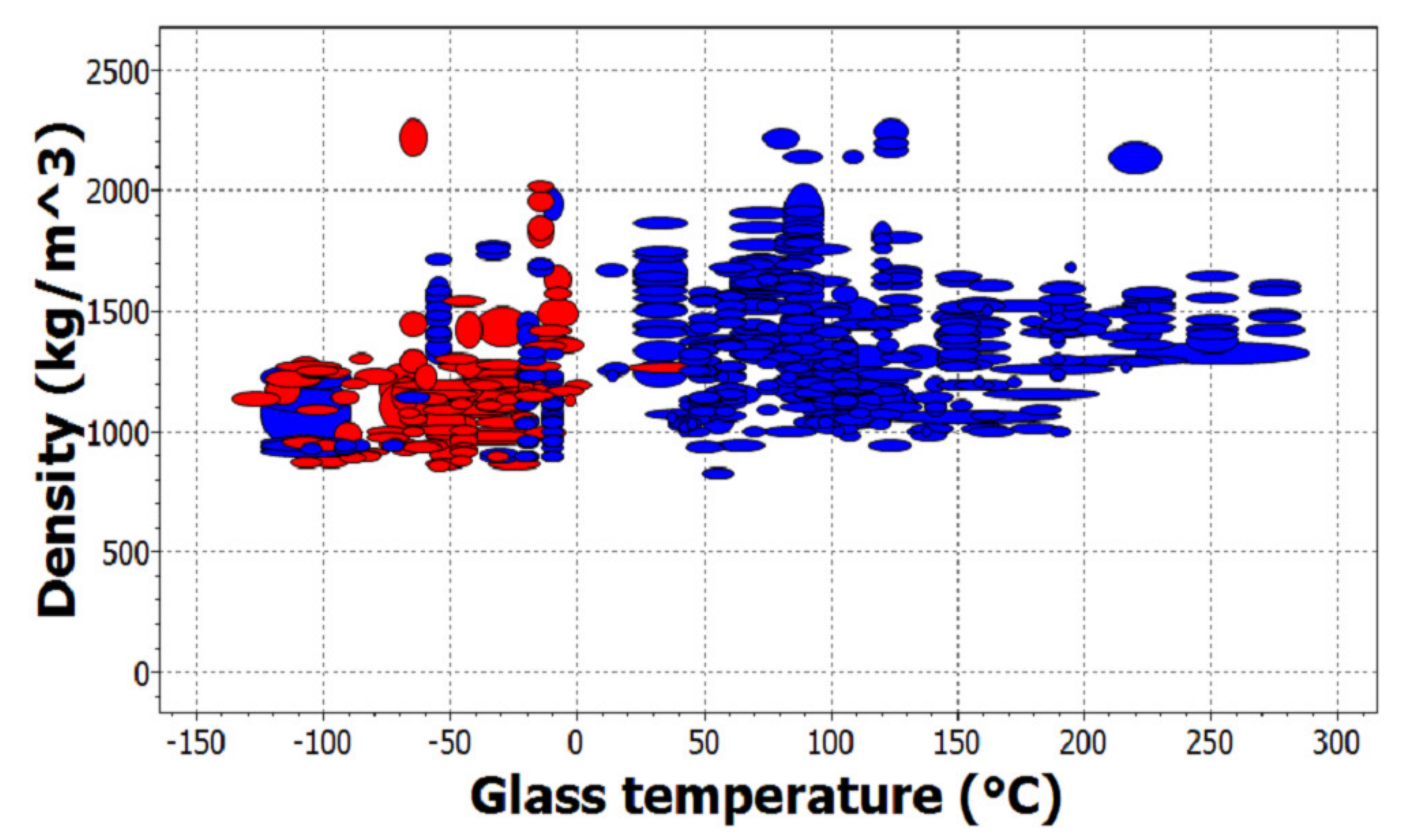

4.5. Seals

- combined sealing system consisting of:

- flexible sealing element;

- two rings to prevent squeezing of the seals;

- two piston guide rings.

- seal with a Glyd ring consisting of:

- Glyd ring, pre-compressed by the O-ring;

- backup ring to protect against contact between metal and metal.

- U-profile sealing for double-acting actuators consisting of:

- U-profile seals;

- backup ring to protect against contact between metal and metal.

- wiper ring;

- a standard U-profile piston rod seal;

- guide ring.

- (a)

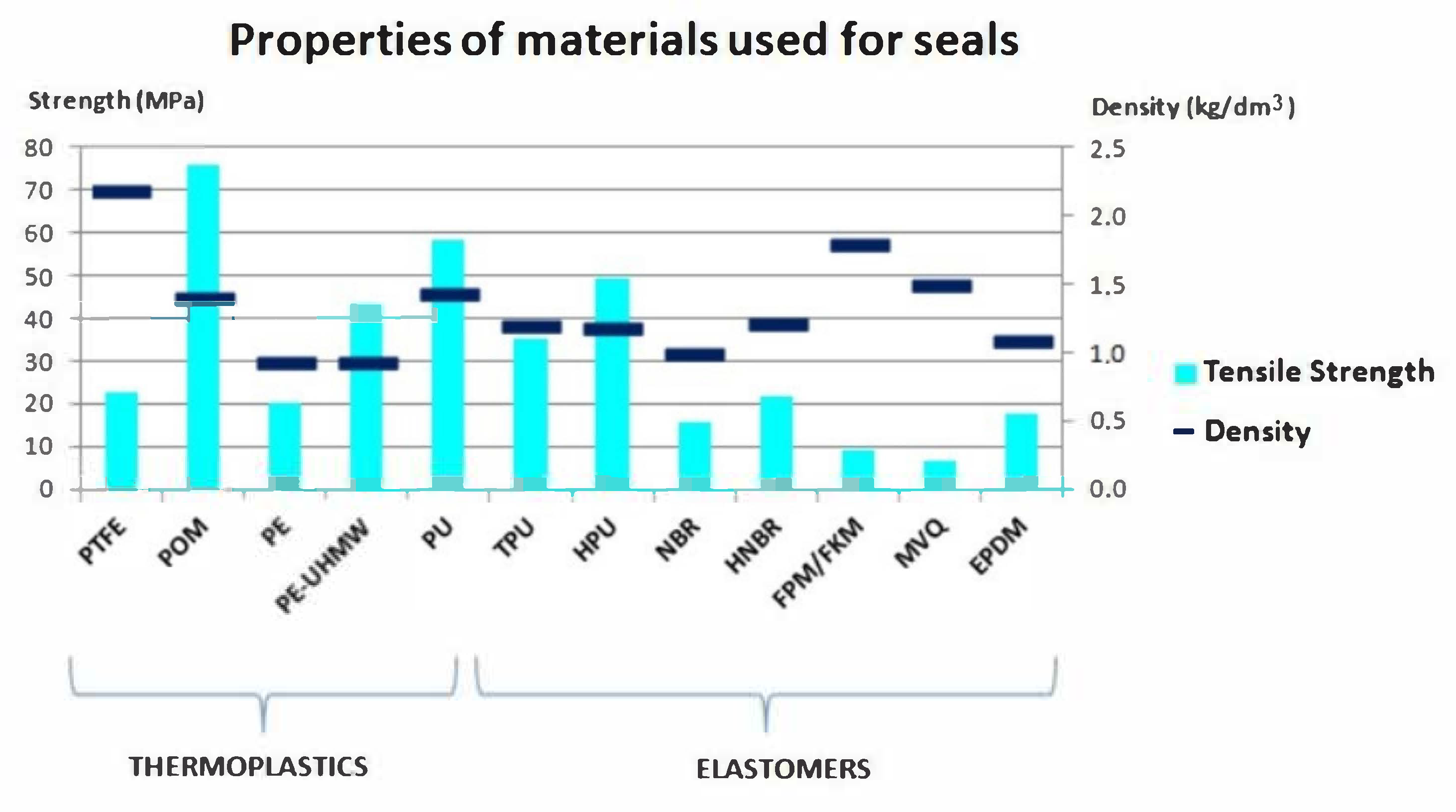

- thermoplastics (thermoplastic polymers)—under the influence of higher temperature they become plastic and after cooling down they harden again;

- (b)

- duroplastics (thermo-set or chemo-set polymers)—after being exposed to temperature or chemical substance, they become hard, their formation is irreversible;

- (c)

- elastomers—they deform to a large extent under low stress, it is possible to return to their original shape.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bohman, E. Understanding Buckling Strength of Hydraulic Cylinders. The Hydraulics & Pneumatics Article 2017. Available online: http://www.hydraulicspneumatics.com/technologies/cylinders-actuators/article/21887243/understanding-buckling-strength-of-hydraulic-cylinders (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Nicoletto, G.; Marin, T. Failure of a heavy-duty hydraulic cylinder and its fatigue re-design. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2011, 18, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzny, S.; Kutrowski, Ł. Strength analysis of a telescopic hydraulic cylinder elastically mounted on both ends. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Mech. 2019, 18, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiecki, A. Hydrostatyczny Napęd Maszyn, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1998; pp. 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, W. Hydropneumatic Suspension Systems, 1st ed.; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 95–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Hu, J.; Tan, S. Design and Realization of Hydraulic Cylinder. Reg. Water Conserv. 2018, 1, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Salant, R.F. Numerical analysis of a hydraulic rod seal: Flooded vs. starved conditions. Tribol. Int. 2015, 92, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealing system for piston rods. Seal. Technol. 1995, 18, 4. [CrossRef]

- Peppiatt, N.; Seals, H. The influence of the rod wiper on the leakage from a hydraulic cylinder gland. Seal. Technol. 2003, 12, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, T. Seals for Hydraulic Cylinders. The Hydraulics & Pneumatics Article 2019. Available online: https://www.hydraulicspneumatics.com/technologies/seals/article/21118898/seals-for-hydraulic-cylinders (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Barth, S. Sealing the Deal in Hydraulic Cylinders. P.I. Process Instrumentation Article 2018. Available online: https://www.piprocessinstrumentation.com/bearings-seals/article/15564050/sealing-the-deal-in-hydraulic-cylinders (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Uzny, S.; Kutrowski, Ł. Obciążalność rozsuniętego teleskopowego siłownika hydraulicznego przy uwzględnieniu wyboczenia oraz wytężenia materiału. Modelowanie Inżynierskie 2018, 37, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, K.; Złoto, T. Exploitation and Repair of Hydraulic Cylinders Used in Mobile Machinery. Teka Comm. Mot. Energetics Agric. 2014, 14, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chalamoński, M. Równomierność ruchu tłoka siłownika hydraulicznego. Diagnostyka 2004, 30, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Skowrońska, J.; Zaczyński, J.; Kosucki, A.; Stawiński, Ł. Modern Materials and Surface Modification Methods Used in the Manufacture of Hydraulic Actuators. In Advances in Hydraulic and Pneumatic Drives and Control 2020; Stryczek, J., Warzyńska, U., Eds.; Spinger: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F. Materials Selection in Mechanical Design, 4th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijewska, A.; Bluszcz, A. Analiza poziomów śladu węglowego dla świata i krajów UE. Syst. Wspomagania W Inżynierii Prod. 2017, 6, 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, F. New Technology Could Slash Carbon Emissions from Aluminium Production. The Guardian Article 2018. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/may/10/new-technology-slash-aluminium-production-carbon-emissions (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Solazzi, L. Stress variability in multilayer composite hydraulic cylinder. Compos. Struct. 2021, 259, 113249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solazzi, L. Design and experimental tests on hydraulic actuator made of composite material. Compos. Struct. 2020, 232, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solazzi, L.; Buffoli, A. Telescopic Hydraulic Cylinder Made of Composite Material. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2019, 26, 1189–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formicola, R.; Solazzi, L.; Buffoli, A. The Multi-Parametric Weight Optimization of a Hydraulic Actuator. Actuators 2020, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, M.; Ozimina, D.; Pająk, M. Właściwości powłok węglowych uzyskiwanych w procesach fizycznego osadzania z fazy gazowej. Mechanik 2015, 88, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Ma, G.; Xu, B.; Yong, Q.; He, P. Design and application of friction pair surface modification coating for remanufacturing. Friction 2017, 5, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, L.; Martini, C.; Ceschini, L. Improvement of wear resistance of components for hydraulic actuators: Dry sliding tests for coating selection and bench tests for final assessment. Tribol. Int. 2017, 115, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczak, H.; Rojek, J. Zmęczeniowe pękanie siłowników hydraulicznych. Diagnostyka 2005, 36, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek, T.; Sosnowski, W. Practical fatigue analysis of hydraulic cylinders—Part II, damage mechanics approach. Int. J. Fatigue 2010, 32, 1591–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchen, P. Analiza nierównomierności ruchu tłoka siłownika hydraulicznego. Diagnostyka 2005, 33, 277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczyk, J.; Kosucki, A. Hydrostatic drive of the ferry approach bank. Transp. Probl. 2007, 2, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sochacki, W.; Bold, M. Damped Vibrations of Hydraulic Cylinder with a Spring-damper System in Supports. Procedia Eng. 2017, 177, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zh Aizhambaeva, S.; Maximova, A.V. Development of control system of coating of rod hydraulic cylinders. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 289, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryczek, S. Napęd Hydrostatyczy, 4th ed.; Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 260–281. [Google Scholar]

- Danzer, E. Guidelines to Avoid Those Hydraulic-Cylinder Headaches. The Hydraulics & Pneumatics Article 2018. Available online: https://www.hydraulicspneumatics.com/technologies/cylinders-actuators/article/21887578/guidelines-to-avoid-those-hydrauliccylinder-headaches (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Denisov, L.V.; Boitsov, A.G.; Siluyanova, M.V. Surface Hardening in Hydraulic Cylinders for Airplane Engines. Russ. Eng. Res. 2018, 38, 1080–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczewska, I.; Bednarek, T.; Marczewski, A.; Sosnowski, W.; Jakubczak, H.; Rojek, J. Practical fatigue analysis of hydraulic cylinders and some design recommendations. Int. J. Fatigue 2006, 28, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyakevych, A.; Orlov, L.; Pokhmurs’ka, H. Restoration of the rods of hydraulic cylinders of mining equipment (in Ukrainian). In Abstract of the 11th International Symposium of Ukrainian Mechanical Engineers in Lviv; Andreykiv, O., Hrytsai, I., Kindratsky, B., Kuzio, I., Kushnir, R., Pavlishche, V., Palash, V., Panasyuk, V., Pokhmursky, V., Stotsko, Z., et al., Eds.; Kinpatri LTD: Lviv, Ukraine, 2013; p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Wang, W.; Yan, W.; Jiang, Z.; Shan, Y.; Yang, K. Cracking due to Cu and Ni segregation in a 17-4 PH stainless steel piston rod. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 65, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelson, P. Better Steels Make Better Cylinders. The Hydraulics & Pneumatics Article 2016. Available online: https://www.hydraulicspneumatics.com/technologies/cylinders-actuators/article/21885260/better-steels-make-better-cylinders (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Moreira, D.C.; Furtado, H.C.; Buarque, J.S.; Cardoso, B.R.; Merlin, B.; Moreira, D.D.C. Failure analysis of AISI 410 stainless-steel piston rod in spillway floodgate. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 97, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rütti, T.F.; Wentzel, E.J. Investigation of failed actuator piston rods. In Failure Analysis Case Studies II; Jones, D.R.H., Ed.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, W.; Yan, W.; Jiang, Z.; Shan, Y.; Yang, K. Microstructure characteristics of segregation zone in 17-4PH stainless steel piston rod. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2017, 24, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, S.M.O.; Viriato, N.; Vaz, M.; de Castro, P.M.S.T. Failure analysis of the rod of a hydraulic cylinder. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2016, 1, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, M.; Glodež, S.; Kramberger, J. Fatigue assessment of piston rod threaded end. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2009, 16, 1977–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefed’ev, S.P.; Dema, R.R.; Kharchenko, M.V.; Pelymskaya, I.S.; Romanenko, D.N.; Zhuravlev, G.M. Experience in Restoring Hydraulic Cylinder Rods by Plasma Powder Surfacing. Chem. Pet. Eng. 2017, 52, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, T.; Adeyemi, O.; Emagbetere, E. Design and Finite Element Analysis of Double—Acting, Double—Ends Hydraulic Cylinder for Industrial Automation Application. Am. J. Eng. Res. 2017, 6, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, C.; Xi, N.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y. Fatigue failure of hold-down bolts for a hyraulic cylinder gland. Eng. Fail. Anal. 1998, 5, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaconescu, T.; Daconescu, A. An analysis of the sealing element—Hydraulic cylinder tribosystem. In The Annals of University ‘Dunărea De Jos’ of Galaţi, Fascicle VIII: Tribology; University ‘Dunărea De Jos’ of Galaţi: Galati, Romania, 2002; pp. 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.; Chung, K.H. Accelerated wear testing of polyurethane hydraulic seal. Polym. Test. 2017, 63, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasiak, E. Napędy i Sterowania Hydrauliczne i Pneumatyczne, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2001; pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Papatheodorou, T.; Hannifin, P. Influence of hard chrome plated rod surface treatments on sealing behavior of hydraulic rod seals. Seal. Technol. 2005, 4, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heipl, O.; Murrenhoff, H. Friction of hydraulic rod seals at high velocities. Tribol. Int. 2015, 85, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Ouyang, X.; Guo, S.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, H. Numerical analysis of the traction effect on reciprocating seals in the hydraulic actuator. Tribol. Int. 2020, 143, 105966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatte, A.; Salant, R. Transient EHL analysis of an elastomeric hydraulic seal. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Yi-bo, L.; Jiang, X.; Huang, M. Experimental investigation of friction behaviors for double-acting hydraulic actuators with different reciprocating seals. Tribol. Int. 2021, 153, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; He, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, P. Research on pressure compensation and friction characteristics of piston rod seals with different degrees of wear. Tribol. Int. 2020, 142, 105999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, X.B.; Hafizah, N.; Yanada, H. Modeling of dynamic friction behaviors of hydraulic cylinders. Mechatronics 2012, 22, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanters, A.F.C.; Visscher, M. Lubrication of reciprocating seals: Experiments on the influence of surface roughness on friction and leakage. Tribol. Ser. 1989, 14, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Meng, X.; Peng, X.; Chen, Y. Experimental investigations on the effect of rod surface roughness on lubrication characteristics of a hydraulic O-ring seal. Tribol. Int. 2021, 156, 106791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaraggi, M.; Angerhausen, J.; Dorogin, L.; Murrenhoff, H.; Persson, B. Influence of anisotropic surface roughness on lubricated rubber friction with application to hydraulic seals. Wear 2018, 410–411, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraki, M.; Kinbara, E.; Konishi, T. A laboratory simulation for stick-slip phenomena on the hydraulic cylinder of a construction machine. Tribol. Int. 2003, 36, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.S.; Sayles, R.S. An experimental study on the friction behaviour of aircraft hydraulic actuator elastomeric reciprocating seal. Tribol. Interface Eng. Ser. 2005, 48, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dašić, P.; Manđuka, A.; Pantić, R. Research of optimal parameters of machining big hydraulic cylinders from the aspect of quality. In Annals of the Oradea University—Fascicle of Management and Technological Engineering VII (XVII); Editura Universităţii din Oradea: Oradea, Romania, 2008; pp. 1563–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Solazzi, L. Feasibility study of hydraulic cylinder subject to high pressure made of aluminum alloy and composite material. Compos. Struct. 2019, 209, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, W. Zastosowanie obróbki nagniataniem w technologii siłowników hydraulicznych. Postępy Nauk. I Tech. 2011, 6, 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Balavignesh, V.N.; Balasubramaniam, B.; Kotkunde, N. Numerical investigations of fracture parameters for a cracked hydraulic cylinder barrel and its redesign. Mater. Today Proc. Part A 2017, 4, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsima, M. Material Selection Process for Hydraulic Cylinder. Eat309 Mechanical Design. Part 5, Materials Review and Selection. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272506787_Material_Selection_Process_for_Hydraulic_Cylinder (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Pawłowski, W.; Kępczak, N. Teoretyczne badania właściwości dynamicznych łóż obrabiarki wykonanych z żeliwa i hybrydowego połączenia żeliwa z odlewem mineralnym. Mechanik 2015, 8, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tubielewicz, K.; Turczyński, K.; Szyguła, M.; Chlebek, D.; Michalczuk, H. Indywidualny siłownik hydrauliczny wykonany ze stopów lekkich. Mechanik 2015, 7, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mantovani, S. Feasibility Analysis of a Double-Acting Composite Cylinder in High-Pressure Loading Conditions for Fluid Power Applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zwingmann, B.; Schlaich, M. Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer for Cable Structures—A Review. Polymers 2015, 7, 2078–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubecki, M. Selected design issues in hydraulic cylinder made of composite materials. In Badania i Rozwój Młodych Naukowców w Polsce: Nauki Techniczne i Inżynieryjne: Materiały, Polimery, Kompozyty; Leśny, J., Chojnicki, B.H., Panfil, M., Nyćkowiak, J., Eds.; Młodzi Naukowcy: Poznań, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, S.; Kroll, L. Nanocomposite glide surfaces for FRP hydraulic cylinders—Evaluation and test. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 61, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryczek, P.; Przystupa, F.; Banaś, M. Research on series of hydraulic cylinders made of plastics. In Proceedings of the 2018 Global Fluid Power Society PhD Symposium, Samara, Russia, 18–20 July 2018; p. 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryczek, J.; Banaś, M.; Krawczyk, J.; Marciniak, L.; Stryczek, P. The Fluid Power Elements and Systems Made of Plastics. Procedia Eng. 2017, 176, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnisch, M. Kunststoffe n fluidtechnischen Antrieben. Oelhydraulik Und Pneum. 2013, 11–12, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzański, L.A. Podstawy Nauki o Materiałach i Metaloznawstwo, 2nd ed.; Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2006; pp. 523–684, 947–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Kula, P. Inżynieria Warstwy Wierzchniej, 1st ed.; Monografie: Łodź, Poland, 2000; pp. 79–243. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, P. Analiza modelu matematycznego układu sterowania kierownicą turbiny wodnej małej mocy. Logistyka 2014, 6, 10823–10831. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, B. Pressure Ratings and Design Guidelines for Ductile Iron Manifolds. In 2014 IFPE Technical Conference: Where All the Solutions Come Together and Connections Are Made; NFPA: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk, J.; Stryczek, J. Układ hydrauliczny z elementami wykonanymi z tworzyw sztucznych. Górnictwo Odkryw. 2013, 54, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wach, P.; Michalski, J.; Tacikowski, J.; Kowalski, S.; Betiuk, M. Gazowe azotowanie i jego odmiany w przemysłowych zastosowaniach. Inżynieria Mater. 2008, 29, 808–811. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.-Y.; Lin, S.-F.; Yang, S.-Z.; Pan, G.-F.; Guo, N.; Dai, L.-L. Cracking cause analysis of 45 steel piston rod. Heat Treat. Met. 2011, 36, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bobzin, K.; Öte, M.; Linke, T.F.; Malik, K.M. Wear and Corrosion Resistance of Fe-Based Coatings Reinforced by TiC Particles for Application in Hydraulic Systems. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2015, 25, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevagin, S.; Mnatsakanyan, V.U. Ensuring the required manufacturing quality of hydraulic-cylinder rods in mining machines. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019; Institute of Physics Publishing: Sevastopol, Russia, 2020; p. 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawiak, M. Spawanie tłoczyska siłowników hydraulicznych. Przegląd Spaw. 2013, 85, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Liu, D.; Han, D. Improvement of corrosion and wear resistances of AISI 420 martensitic stainless steel using plasma nitriding at low temperature. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 2577–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, J.; Näkki, J.; Pajukoski, H.; Miettinen, J.; Peltola, T.; Vuoristo, P. Wear and corrosion resistant laser coatings for hydraulic piston rods. J. Laser Appl. 2015, 27, 022009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Ju, D. Modeling and Simulation of Quenching and Tempering Process in steels. Phys. Procedia 2013, 50, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; Hultgren, J.; Roberts, W. Increased Resistance to Buckling of Piston Rods Through Induction Hardening, OVAKO Article 2018. Available online: http://www.ovako.com/globalassets/products/hard-chromed/ih_buckling_wp.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Gayathri, N.; Karthick, N.; Shanmuganathan, V.K.; Adhithyan, T.R.; Madhan Kumar, T.; Gopalakrishnan, J. Productivity Improvement and Cost Reduction in Hydraulic Cylinders. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeman, D.; Jagadeesha, T. Tribological characterization of electrolytic hard chrome & WC-C0 coatings. Mater. Today Proc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgornik, B.; Massler, O.; Kafexhiu, F.; Sedlaček, M. Crack density and tribological performance of hard-chrome coatings. Tribol. Int. 2018, 121, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.C.; Constant, S.L.; Patierno, S.R.; Jurjus, R.A.; Ceryak, S.M. Exposure to particulate hexavalent chromium exacerbates allergic asthma pathology. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2012, 259, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardelle, A.M. LCA F18 Hard chrome and HVOF coating. In Proceedings of the International Thermal Spray Conference and Exposition 2008—ASM Thermal Spray Society, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2–4 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Flitney, B. Alternatives to chrome for hydraulic actuators. Seal. Technol. 2007, 10, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolelli, G.; Giovanardi, R.; Lusvarghi, L.; Manfredini, T. Corrosion resistance of HVOF-sprayed coatings for hard chrome replacement. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 3375–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picas, J.A.; Forn, A.; Matthäus, G. HVOF coatings as an alternative to hard chrome for pistons and valves. Wear 2006, 261, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, C.; Settles, G. The High-Velocity Oxy-Fuel (HVOF) thermal spray—Materials processing from a gas dynamics perspective. In Proceedings of the Fluid Dynamic Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 19–22 June 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutsaylyuk, V.; Student, M.M.; Zadorozhna, K.; Student, O.; Veselivska, H.; Gvosdetskii, V.; Maruschak, P.; Pokhmurska, H. Improvement of wear resistance of aluminum alloy by HVOF method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 16367–16377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyakevych, A.A.; Orlov, L.M.; Pokhmurs’ka, H.V.; Student, M.M.; Chervins’ka, N.R.; Khyl’ko, O.V. Influence of the Phase Composition of the Layers Deposited on the Rods of Hydraulic Cylinders on Their Local Corrosion. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuk, Y. Nanostructured CVD Tungsten Carbide Coating on Aircraft Actuators and Gearbox Shafts Reduces Oil Leakage and Improves Durability. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 1914–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalibón, E.L.; Pecina, J.N.; Moscatelli, M.N.; Ramírez Ramos, M.A.; Trava-Airoldi, V.J.; Brühl, S.P. Mechanical and Corrosion Behaviour of DLC and TiN Coatings Deposited on Martensitic Stainless Steel. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros. 2019, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F.; Jones, D.R.H. Materiały Inżynierskie, 2nd ed.; Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1996; Volume 2, pp. 266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Golchin, A.; Simmons, G.; Glavatskih, S. Breakaway friction of PTFE materials in lubricated conditions. Tribol. Int. 2012, 48, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Salant, R. Simulation of a Hydraulic Rod Seal with a Textured Rod and Starvation. Tribol. Int. 2016, 95, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Density (kg/dm3) | Minimum Yield Strength (MPa) | Minimum Tensile Strength (MPa) | Maximum Carbon Content (%) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St52/S355J2G3/S355JR | 7.8 | 355 | 490 | 0.2 | low-carbon structural steel |

| E355 | 0.22 | low-carbon quality steel | |||

| S275JR | 7.9 | 275 | 410 | 0.21 | low-carbon structural steel |

| S235JR | 7.8 | 235 | 340 | 0.2 | low-carbon structural steel |

| BS970070M20 | 7.8 | 210 | 410 | 0.24 | low-carbon structural steel |

| R35 | 7.9 | 235 | 345 | 0.16 | low-carbon structural steel for pipes |

| R45 | 7.9 | 255 | 440 | 0.22 | low-carbon structural steel for pipes |

| IS 1030 GRADE 280-580 | 7.85 | 280 | 580 | 0.25 | non-alloy steel, general purpose |

| AISI 304 | 7.9 | 210 | 520 | 0.08 | austenitic stainless steel |

| 60-40-18 | 7.1 | 276 | 414 | 3.4–3.8 | spheroidal cast iron |

| Al 7075-T6 | 2.8 | 430 * | 510 | – | Al-Zn alloy |

| POM | 1.41 | 67–69 | 67–85 | – | polyoxymethylene |

| PA | 1.13 | 40 | 67 | – | polyamide |

| PP | 0.92 | 30 | 32 | – | polypropylene |

| Material | Average Hardness | Impact Energy (J) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| St52/S355J2G3/S355JR | 180 HB | 27 (−20 °C) | 22 |

| E355 | |||

| S275JR | 160 HB | 27 (20 °C) | 22 |

| S235JR | 140 HB | 27 (20 °C) | 26 |

| BS970070M20 | 140 HB | 24 (10 °C) | 21 |

| R35 | 112 HB | 27 (0 °C) | 24 |

| R45 | 142 HB | 22 (20 °C) | 22 |

| IS 1030 GRADE 280-580 | 220 HB | 22 (20 °C) | 18 |

| AISI 304 | 215 HB | 60 (−196 °C) | 45 |

| 60-40-18 | 160 HB | 12 (−20 °C) | 18 |

| Al 7075-T6 | 150 HB | 17 (23 °C) | 10 |

| POM | 81 (Shore D) | - | 30 |

| PA | 76–82 (Shore D) | - | 20–200 |

| PP | 70–83 (Shore D) | - | 150–600 |

| Material | Density (kg/dm3) | Minimum Yield Strength (MPa) | Minimum Tensile Strength (MPa) | Maximum Carbon Content (%) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65-45-12 | 7.1 | 310 | 448 | 3.50–3.90 | spheroidal cast iron |

| C35 | 7.8 | 270 | 520 | 0.32–0.39 | medium-carbon structural steel |

| C45 | 7.8 | 305 | 580 | 0.42–0.5 | medium-carbon structural steel |

| S275JR | 7.9 | 275 | 410 | 0.21 | low-carbon structural steel |

| S355JR | 7.8 | 355 | 490 | 0.2 | low-carbon structural steel |

| BS970070M20 | 7.8 | 210 | 410 | 0.24 | low-carbon structural steel |

| Al 7075-T6 | 2.8 | 430 * | 510 | – | Al-Zn alloy |

| POM | 1.41 | 67–69 | 67–85 | – | polyoxymethylene |

| Material | Average Hardness | Impact Energy (J) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 65-45-12 | 131–220 HB | 14 (23 °C) | 12 |

| C35 | 160 HB | 23 (23 °C) | 17 |

| C45 | 200 HB | 25 (23 °C) | 14 |

| S275JR | 160 HB | 27 (20 °C) | 22 |

| S355JR | 165 HB | 27 (20 °C) | 22 |

| BS970070M20 | 140 HB | 24 (10 °C) | 21 |

| Al 7075-T6 | 150 HB | 17 (23 °C) | 10 |

| POM | 81 (Shore D) | – | 30 |

| Material | Density (kg/dm3) | Minimum Yield Strength (MPa) | Minimum Tensile Strength (MPa) | Maximum Carbon Content (%) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S235JR | 7.8 | 235 | 340 | 0.2 | low-carbon structural steel |

| S275JR | 7.9 | 275 | 410 | 0.21 | low-carbon structural steel |

| S355J0 | 7.8 | 355 | 490 | 0.2 | low-carbon structural steel |

| C45 | 7.8 | 305 | 580 | 0.42–0.5 | medium-carbon structural steel |

| C35 | 7.8 | 270 | 520 | 0.32–0.39 | medium-carbon structural steel |

| C55 | 7.8 | 330 | 640 | 0.5–0.6 | medium-carbon structural steel |

| 40Cr/40X | 7.8 | 785 | 810 | 0.37–0.44 | alloy steel |

| C45E | 7.8 | 305 | 580 | 0.42–0.5 | medium-carbon structural steel |

| 40HM/ 42CrMo4 | 7.8 | 750 * | 1000 | 0.38–0.45 | alloy steel |

| 20MnV6 | 7.8 | 410 | 550 | 0.22 | low-alloy structural steel |

| 19MnVS6 | 7.8 | 390 | 600 | 0.15–0.22 | non-alloy special steel |

| 38MnVS6 | 7.8 | 520 | 800 | 0.34–0.41 | alloy steel |

| 30CrNiMo8 | 7.8 | 830 | 980 | 0.26–0.34 | alloy structural steel |

| BS970070M20 | 7.8 | 210 | 410 | 0.24 | low-carbon structural steel |

| BS970070M55 | 7.8 | 330 | 640 | 0.52–0.6 | medium-carbon structural steel |

| 17-4PH | 7.8 | 1000 | 1100 | 0.07 | martensitic stainless steel |

| AISI 304 | 7.9 | 210 | 520 | 0.08 | austenitic stainless steel |

| AISI 410 | 7.8 | 415 | 450 | 0.15 | martensitic stainless steel |

| Al 7075-T6 | 2.8 | 430 * | 510 | – | Al-Zn alloy |

| POM | 1.41 | 67–69 | 67–85 | – | poly-oxymethylene |

| Material | Average Hardness | Impact Energy (J) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S235JR | 140 HB | 27 (20 °C) | 26 |

| S275JR | 160 HB | 27 (20 °C) | 22 |

| S355J0 | 165 HB | 27 (0 °C) | 18 |

| C45 | 200 HB | 25 (23 °C) | 14 |

| C35 | 160 HB | 23 (23 °C) | 17 |

| C55 | 225 HB | 25 (23 °C) | 15 |

| 40Cr/40X | 200 HB | 47 (23 °C) | 9 |

| C45E | 207 HB | 25 (23 °C) | 16 |

| 40HM/ 42CrMo4 | 218 HB | 30 (23 °C) | 10 |

| 20MnV6 | 220 HB | 27 (−20 °C) | 19 |

| 19MnVS6 | 255 HB | 24 (23 °C) | 16 |

| 38MnVS6 | 275 HB | 20 (20 °C) | 12 |

| 30CrNiMo8 | 250 HB | 30 (23 °C) | 13 |

| BS970070M20 | 140 HB | 24 (10 °C) | 21 |

| BS970070M55 | 220 HB | 25 (23 °C) | 12 |

| 17-4PH | 305 HB | 42 (23 °C) | 16 |

| AISI 304 | 215 HB | 60 (−196 °C) | 45 |

| AISI 410 | 217 HB | 30 (23 °C) | 20 |

| Al 7075-T6 | 150 HB | 17 (23 °C) | 10 |

| POM | 81 (Shore D) | – | 30 |

| Material | Density (kg/dm3) | Minimum Yield Strength (MPa) | Minimum Tensile Strength (MPa) | Maximum Carbon Content (%) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S355/S355JR | 7.8 | 355 | 490 | 0.2 | low-carbon structural steel |

| S275JR | 7.9 | 275 | 410 | 0.21 | low-carbon structural steel |

| Al 7075-T6 | 2.8 | 430 * | 510 | – | Al-Zn alloy |

| IS 1030 GRADE 280-580 | 7.85 | 280 | 580 | 0.25 | non-alloy steel |

| BS970070M20 | 7.8 | 210 | 410 | 0.24 | low-carbon structural steel |

| POM | 1.41 | 67–69 | 67–85 | – | poly-oxymethylene |

| C45 | 7.8 | 305 | 580 | 0.42–0.5 | medium-carbon structural steel |

| 42CrMo4 | 7.8 | 750 * | 1000 | 0.38–0.45 | alloy steel |

| AISI304 | 7.9 | 210 | 520 | 0.08 | austenitic stainless steel |

| G25 | 7.2 | 165 | 250 | 3.2–3.5 | grey cast iron |

| Material | Average Hardness | Impact Energy (J) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S355/S355JR | 165 HB | 27 (20 °C) | 22 |

| S275JR | 160 HB | 27 (20 °C) | 22 |

| Al 7075-T6 | 150 HB | 17 (23 °C) | 10 |

| IS 1030 GRADE 280-580 | 220 HB | 22 (20 °C) | 18 |

| BS970070M20 | 140 HB | 24 (10 °C) | 21 |

| POM | 81 (Shore D) | – | 30 |

| C45 | 200 HB | 25 (23 °C) | 14 |

| 42CrMo4 | 218 HB | 30 (23 °C) | 10 |

| AISI 304 | 215 HB | 60 (−196 °C) | 45 |

| G25 | 215 HB | 12 (−20 °C) | 0.5 |

| Material | Density (kg/dm3) | Minimum Tensile Strength (MPa) | Minimum Service Temperature (°C) | Maximum Service Temperature (°C) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THERMOPLASTICS | |||||

| PTFE | 2.2 | 17–28 | −200 | 250 | polytetrafluoroethylene |

| POM | 1.41 | 67–85 | −50 | 90 | polyoxymethylene |

| PE * | 0.91–0.94/ 0.95–0.98 | 7–17/ 20–37 | −50/−50 | 75/80 | polyethylene |

| PE-UHMW | 0.94 | 38.6–48.3 | −150 | 90 | polyethylene (ultra high molecular weight) |

| ELASTOMERS | |||||

| PU | 1.45 | 20.7–96.0 | −60 | 90 | polyurethane |

| TPU | 1.2 | 30–40 | −40 | 80 | thermoplastic polyurethane |

| HPU | 1.19 | 49.2 | −30 | 110 | hydrolysis resistant polyurethane |

| NBR | 1.0 | 6.89–24.1 | −30 | 120 | nitrile butadiene rubber |

| HNBR | 1.23 | 21.7 | −30 | 150 | hydrogenated nitrile butadiene rubber |

| FPM/FKM | 1.8 | 9 | −35 | 220 | fluorocarbon rubber |

| MVQ | 1.5 | 6.4 | −60 | 200 | methylvinyl silicone rubber |

| EPDM | 1.1 | 17.4 | −45 | 125 | ethylene-propylene-diene monomer |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skowrońska, J.; Kosucki, A.; Stawiński, Ł. Overview of Materials Used for the Basic Elements of Hydraulic Actuators and Sealing Systems and Their Surfaces Modification Methods. Materials 2021, 14, 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14061422

Skowrońska J, Kosucki A, Stawiński Ł. Overview of Materials Used for the Basic Elements of Hydraulic Actuators and Sealing Systems and Their Surfaces Modification Methods. Materials. 2021; 14(6):1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14061422

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkowrońska, Justyna, Andrzej Kosucki, and Łukasz Stawiński. 2021. "Overview of Materials Used for the Basic Elements of Hydraulic Actuators and Sealing Systems and Their Surfaces Modification Methods" Materials 14, no. 6: 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14061422

APA StyleSkowrońska, J., Kosucki, A., & Stawiński, Ł. (2021). Overview of Materials Used for the Basic Elements of Hydraulic Actuators and Sealing Systems and Their Surfaces Modification Methods. Materials, 14(6), 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14061422