Vacancy Defects in Ga2O3: First-Principles Calculations of Electronic Structure

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

3. Results

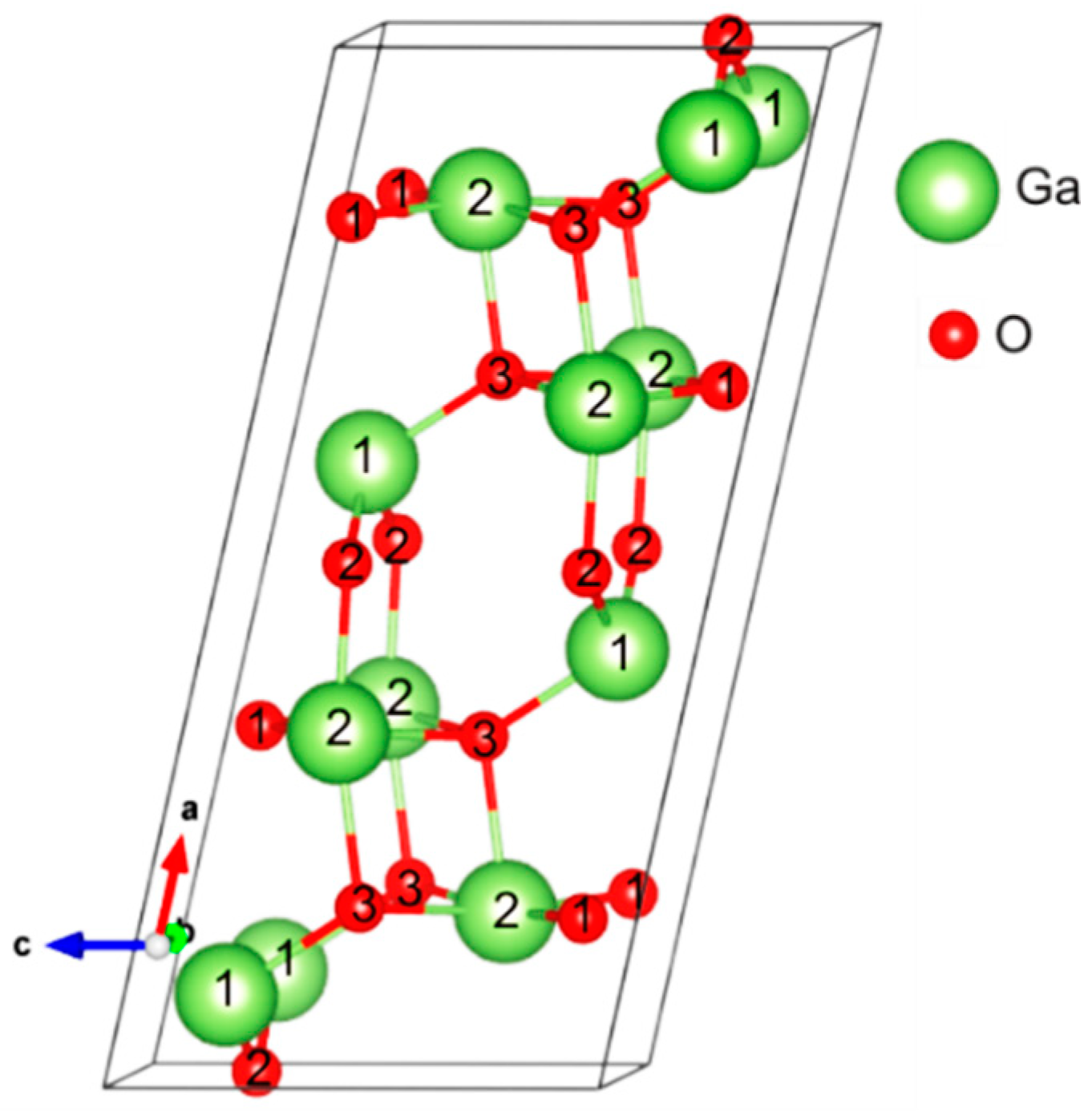

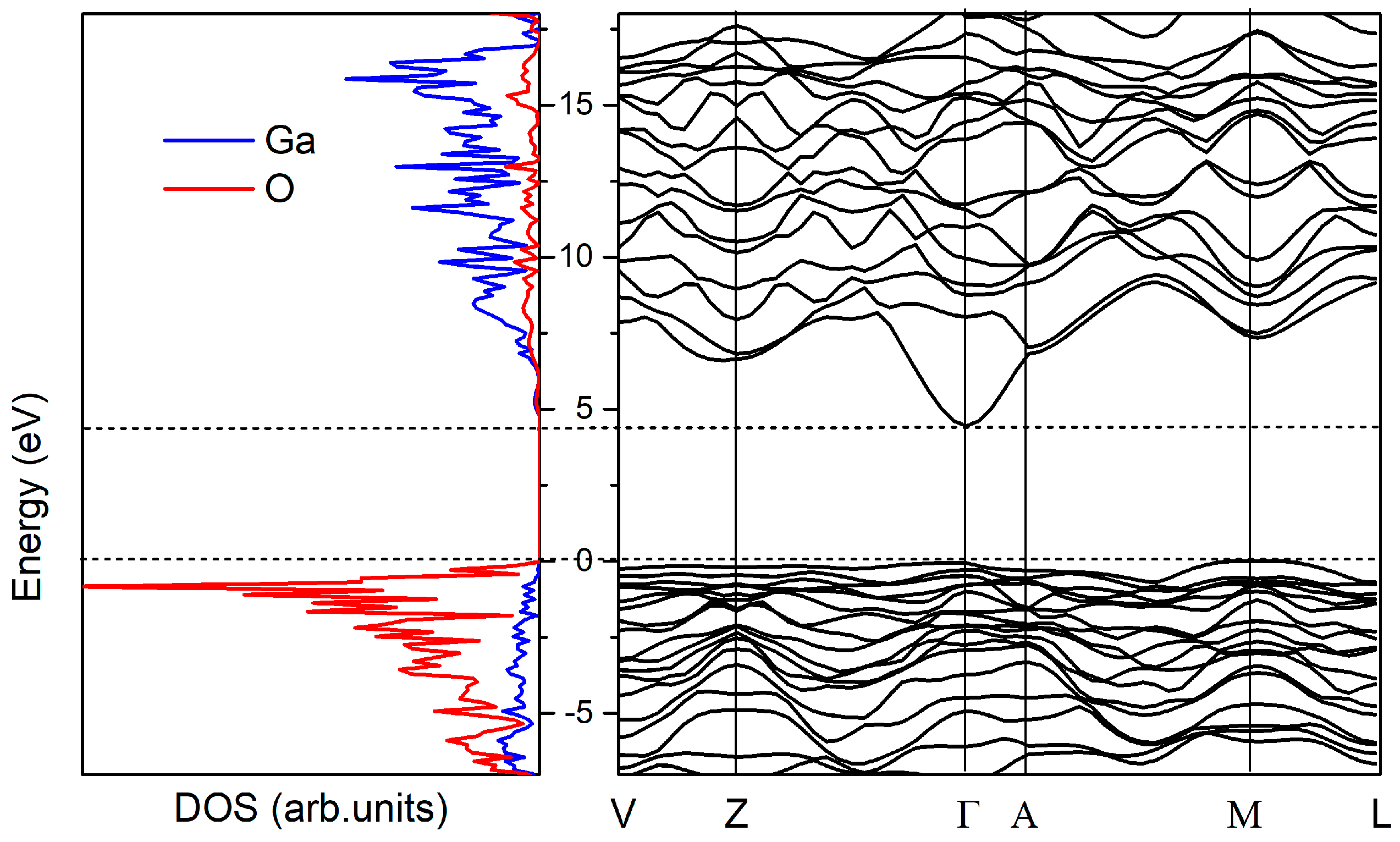

3.1. Atomic and Electronic Structure of Bulk β-Ga2O3

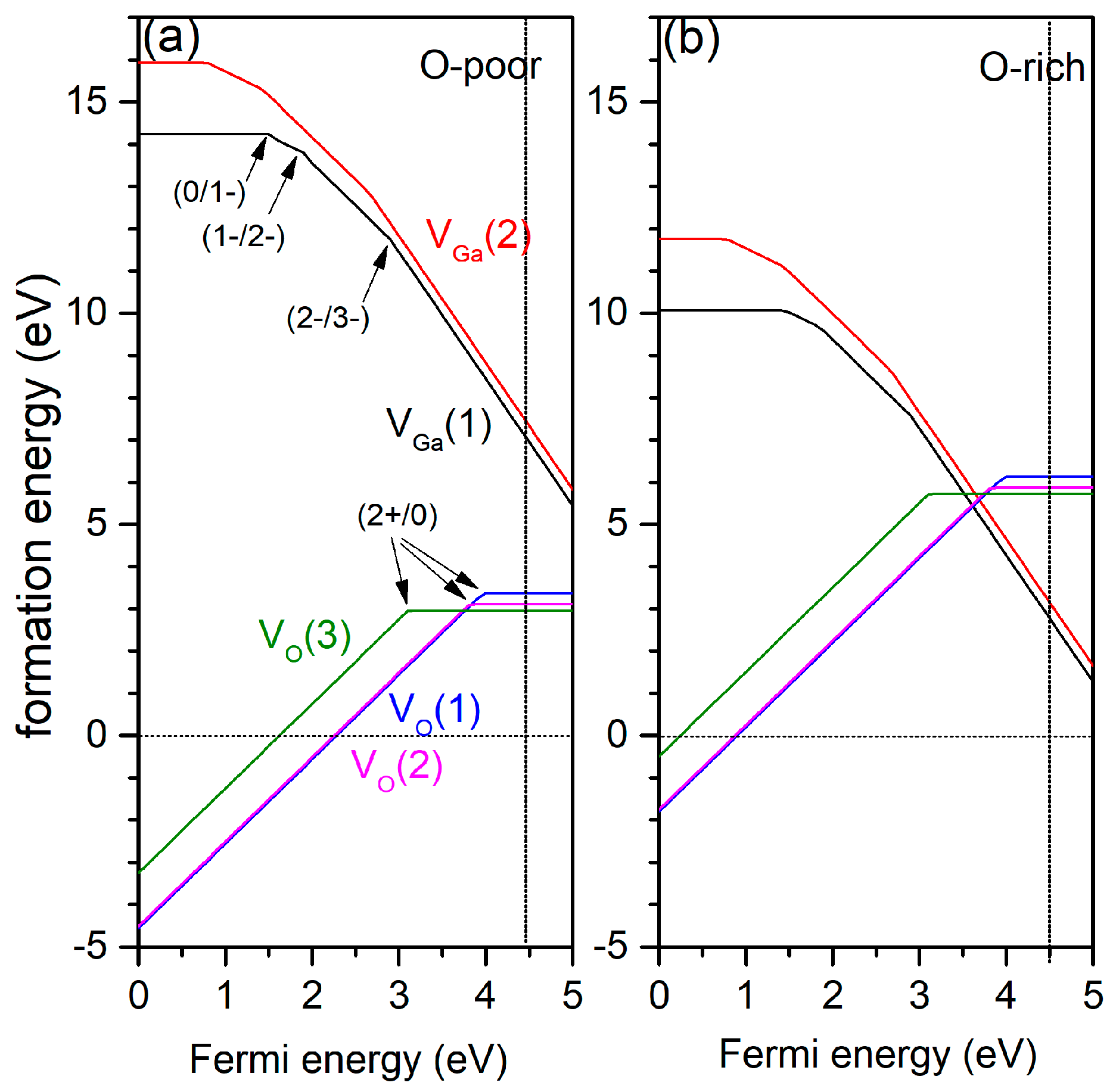

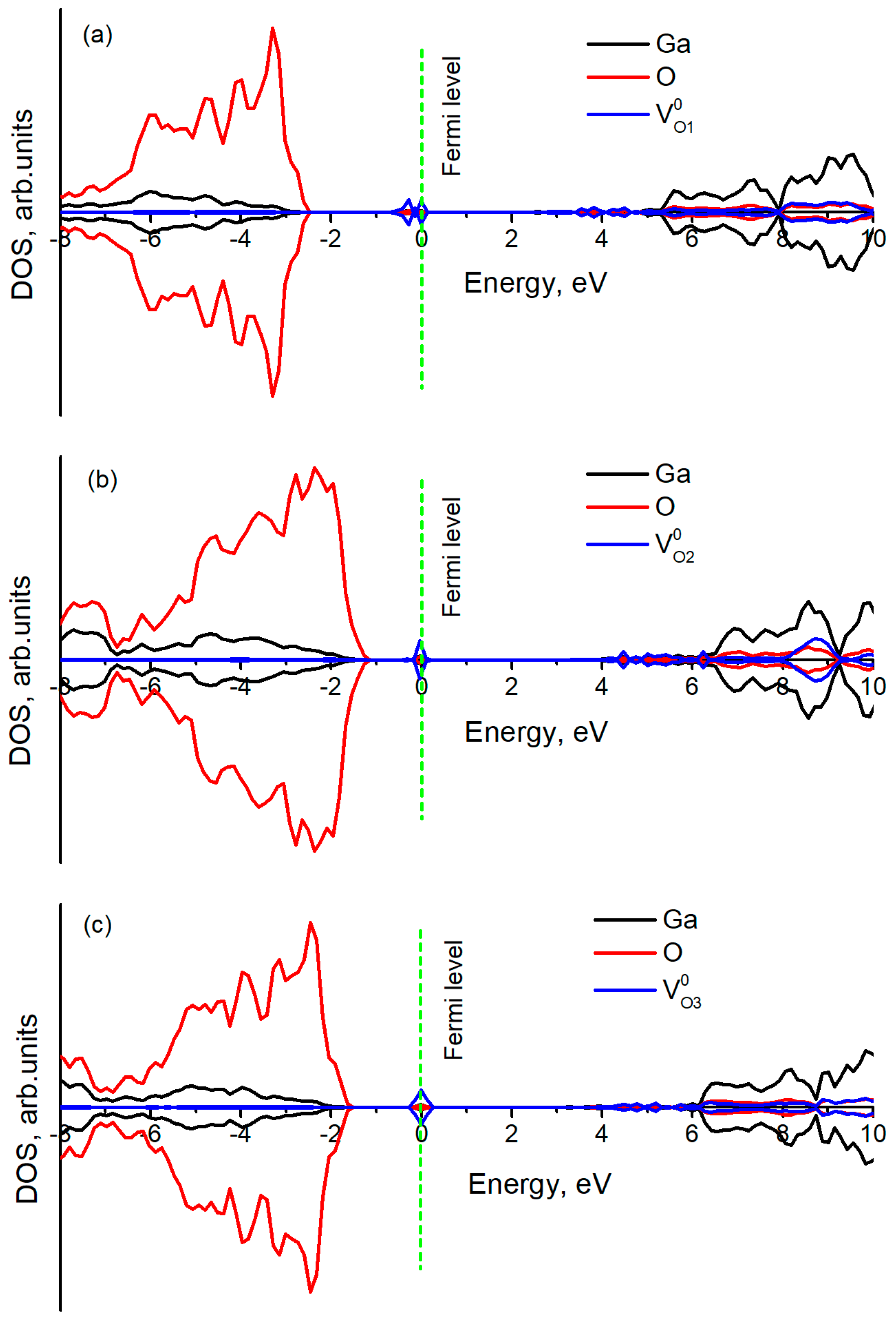

3.2. Oxygen Vacancy

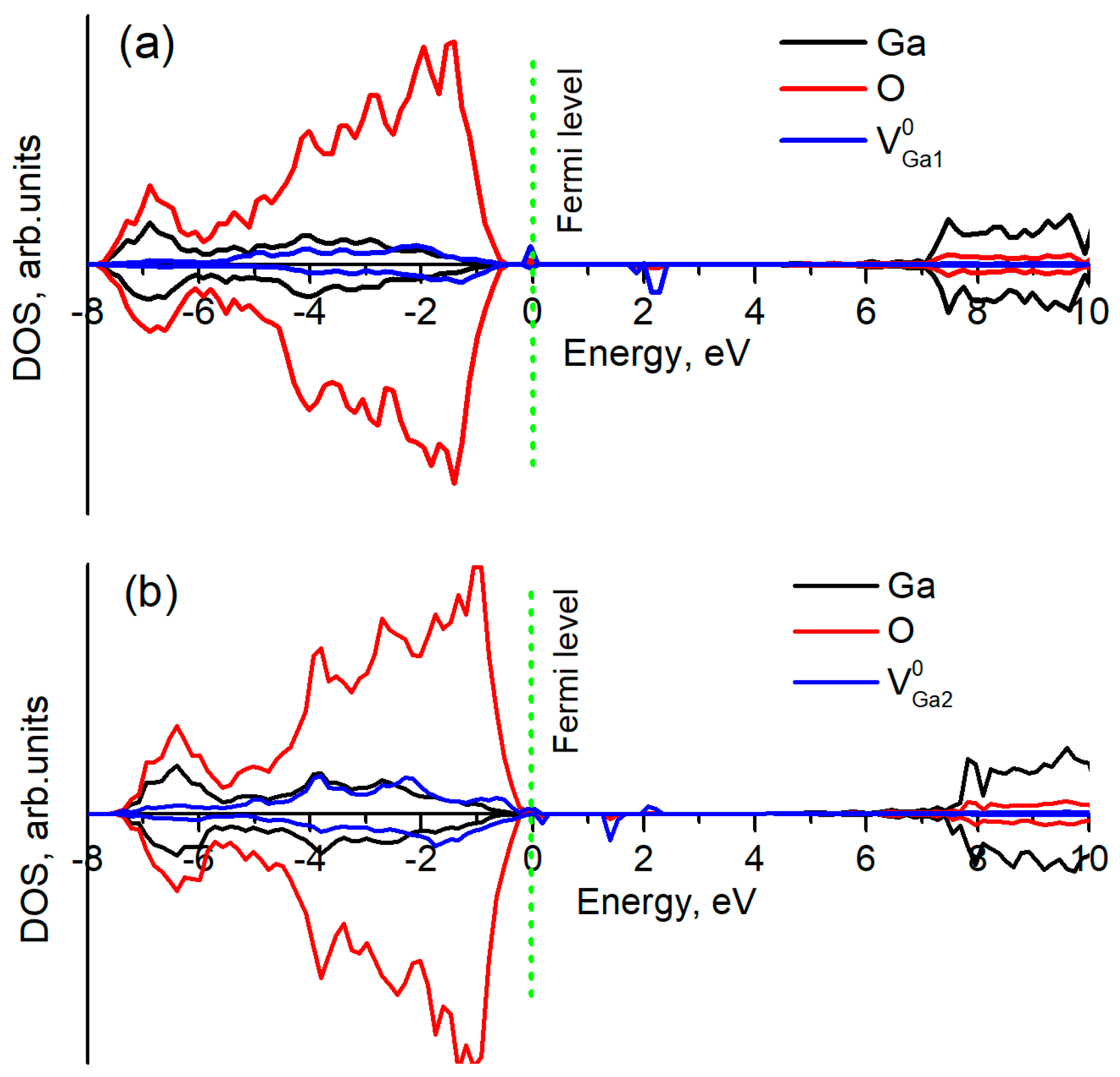

3.3. Gallium Vacancy

4. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Higashiwaki, M.; Sasaki, K.; Kuramata, A.; Masui, T.; Yamakoshi, S. Gallium oxide (Ga2O3) metal-semiconductor field-effect transistors on single-crystal β-Ga2O3 (010) substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 013504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearton, S.J.; Yang, J.; Cary, P.H.; Ren, F.; Kim, J.; Tadjer, M.J.; Mastro, M.A. A review of Ga2O3 materials, processing, and devices. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 011301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, J.; Qi, D.-C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, K.H.L. Recent progress on the electronic structure, defect, and doping properties of Ga2O3. APL Mater. 2020, 8, 020906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konishi, K.; Goto, K.; Murakami, H.; Kumagai, Y.; Kuramata, A.; Yamakoshi, S.; Higashiwaki, M. 1-kV vertical Ga2O3 field-plated Schottky barrier diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Guo, D.; Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Yan, H.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Tang, W.; Guo, X.; An, Y.; et al. Fabrication of β-Ga2O3 thin films and solar-blind photodetectors by laser MBE technology. Opt. Mater. Express 2014, 4, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchechko, A.; Vasyltsiv, V.; Kostyk, L.; Tsvetkova, O.; Popov, A.I. Shallow and deep trap levels in X-ray irradiated β-Ga2O3: Mg. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 2019, 441, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdowski, W.; Makowski, M.; Witkowski, M.E.; Wojtowicz, A.J.; Galazka, Z.; Irmscher, K.; Schewski, R. β-Ga2O3:Ce as a fast scintillator: An unclear role of cerium. Radiat. Meas. 2019, 121, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, J.; Yang, G. On optical properties and scintillation performance of emerging Ga2O3: Crystal growth, emission mechanisms and doping strategies. Mater. Res. Bull. 2021, 144, 111494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lei, M.; Huang, K.; Liang, C.; Xu, J.C.; Shangguan, Z.C.; Yuan, Q.X.; Ma, L.H.; Du, Y.X.; Fan, D.Y.; et al. A facile route to porous beta-gallium oxide nanowires-reduced graphene oxide hybrids with enhanced photocatalytic efficiency. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 623, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binet, L.; Gourier, D.; Minot, C. Relation between electron band structure and magnetic bistability of conduction electrons in β-Ga2O3. J. Solid State Chem. 1994, 113, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tu, W.; Ma, X.; Pei, Y.; Wang, G. β-Ga2O3 versus ε-Ga2O3: Control of the crystal phase composition of gallium oxide thin film prepared by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 420, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacherle, T.; Schmidt, P.C.; Martin, M. Ab initio calculations on the defect structure of β-Ga2O3. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2013, 87, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, J.B.; Peelaers, H.; Janotti, A.; Van De Walle, C.G. Hydrogenated cation vacancies in semiconducting oxides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2011, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.L.; Li, M.K.; Yu, D.Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Qian, C.; Yang, Z. Fabrication and characteristics of N-doped β-Ga2O3 nanowires. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2010, 98, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L.; Jia, R. First-principles calculations of electronic and optical properties of aluminum-doped β-Ga2O3 with intrinsic defects. Results Phys. 2017, 7, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Jia, R.; Li, C.; Xin, B.; Zhang, Y. Ab initio study of N-doped β-Ga2O3 with intrinsic defects: The structural, electronic and optical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 712, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, J.B.; Weber, J.R.; Janotti, A.; Van De Walle, C.G. Oxygen vacancies and donor impurities in β-Ga2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 142106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usseinov, A.; Koishybayeva, Z.; Platonenko, A.; Akilbekov, A.; Purans, J.; Pankratov, V.; Suchikova, Y.; Popov, A.I. Ab-Initio Calculations of Oxygen Vacancy in Ga2O3 Crystals. Latv. J. Phys. Tech. Sci. 2021, 58, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.Z.; Wang, L.L.; Xu, L.; Wan, Q.; Zou, B.S. Electronic structure and magnetic interactions in Ni-doped β-Ga2O3 from first-principles calculations. Scr. Mater. 2009, 61, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Jin-Liang, Y.; Li-Ying, Z.; Gang, Z.; Chao, L.; Jin-Liang, Y.; Li-Ying, Z.; Gang, Z. Electronic structures and optical properties of Zn-doped β-Ga2O3 with different doping sites. Chin. Phys. B 2012, 21, 127104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Yan, J.L.; Zhang, Y.J.; Li, T. Effects of N-doping concentration on the electronic structure and optical properties of N-doped β-Ga2O3. Chin. Phys. B 2012, 21, 67102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zheng, W.; Hu, P.; Cao, W.; Yang, B. Synthesis of two-dimensional β-Ga2O3 nanosheets for high-performance solar blind photodetectors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 3254–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Guo, Y.; Song, Q.; Chen, Y. First-principles study on electronic structure and optical properties of Cu-doped β-Ga2O3. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2014, 434, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dovesi, R.; Erba, A.; Orlando, R.; Zicovich-Wilson, C.M.; Civalleri, B.; Maschio, L.; Rérat, M.; Casassa, S.; Baima, J.; Salustro, S.; et al. Quantum-mechanical condensed matter simulations with CRYSTAL. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 8, e1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Jaffe, J.E.; Harrison, N.M. Ab initio study of high pressure phase transition in GaN. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1994, 55, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towler, M.D.; Allan, N.L.; Harrison, N.M.; Saunders, V.R.; MacKrodt, W.C.; Aprà, E. Ab initio study of MnO and NiO. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 5041–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulliken, R.S. Electronic population analysis on LCAO-MO molecular wave functions. II. Overlap populations, bond orders, and covalent bond energies. J. Chem. Phys. 1955, 23, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makov, G.; Payne, M.C. Periodic boundary conditions in ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 51, 4014–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lany, S.; Zunger, A. Assessment of correction methods for the band-gap problem and for finite-size effects in supercell defect calculations: Case studies for ZnO and GaAs. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2008, 78, 235104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scherz, U.; Scheffler, M. Density-Functional Theory of sp-Bonded Defects in III/V Semiconductors. Semicond. Semimetals 1993, 38, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orita, M.; Ohta, H.; Hirano, M.; Hosono, H. Deep-ultraviolet transparent conductive β-Ga2O3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 77, 4166–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Orlando, R.; Blanco, M.A.; Pandey, R.; Amzallag, E.; Baraille, I.; Rérat, M. First-principles study of the structural, electronic, and optical properties of Ga2O3 in its monoclinic and hexagonal phases. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2006, 74, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rebien, M.; Henrion, W.; Hong, M.; Mannaerts, J.P.; Fleischer, M. Optical properties of gallium oxide thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 81, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Passlack, M.; Schubert, E.F.; Hobson, W.S.; Hong, M.; Moriya, N.; Chu, S.N.G.; Konstadinidis, K.; Mannaerts, J.P.; Schnoes, M.L.; Zydzik, G.J. Ga2O3 films for electronic and optoelectronic applications. J. Appl. Phys. 1995, 77, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wenckstern, H. Group-III Sesquioxides: Growth, Physical Properties and Devices. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2017, 3, 1600350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, S.I.; Nikolaev, V.I.; Bougrov, V.E.; Romanov, A.E. Gallium oxide: Properties and applications—A review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2016, 44, 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Osipov, A.V.; Grashchenko, A.S.; Kukushkin, S.A.; Nikolaev, V.I.; Osipova, E.V.; Pechnikov, A.I.; Soshnikov, I.P. Structural and elastoplastic properties of β-Ga2O3 films grown on hybrid SiC/Si substrates. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 2018, 30, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.; Böttcher, K.; Galazka, Z.; Schreuer, J. Numerical Modelling of the Czochralski Growth of β-Ga2O3. Crystals 2017, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adachi, K.; Ogi, H.; Takeuchi, N.; Nakamura, N.; Watanabe, H.; Ito, T.; Ozaki, Y. Unusual elasticity of monoclinic β-Ga2O3. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 085102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.; Korlacki, R.; Knight, S.; Hofmann, T.; Schöche, S.; Darakchieva, V.; Janzén, E.; Monemar, B.; Gogova, D.; Thieu, Q.-T.; et al. Anisotropy, phonon modes, and free charge carrier parameters in monoclinic β-gallium oxide single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 125209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onuma, T.; Saito, S.; Sasaki, K.; Goto, K.; Masui, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Honda, T.; Kuramata, A.; Higashiwaki, M. Temperature-dependent exciton resonance energies and their correlation with IR-active optical phonon modes in β-Ga2O3 single crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichelis, R.; Suto, H.; Noël, Y.; Sogawa, H.; Naoi, T.; Koike, C.; Chihara, H.; Shimobayashi, N.; Ferrabone, M.; Dovesi, R. The infrared spectrum of ortho-enstatite from reflectance experiments and first-principle simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 420, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Víllora, E.G.; Morioka, Y.; Atou, T.; Sugawara, T.; Kikuchi, M.; Fukuda, T. Infrared reflectance and electrical conductivity of β-Ga2O3. Phys. Status Solidi Appl. Res. 2002, 193, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuhata, T.; Shimada, K. Polar phonons in β-Ga2O3 studied by IR reflectance spectroscopy and first-principle calculations. Appl. Phys. Express 2017, 10, 081101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, M.D. Point defects in Ga2O3. J. Appl. Phys 2020, 127, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Ganguli, S.; Roy, A.K.; Badescu, S.C. Density functional tight binding study of β-Ga2O3: Electronic structure, surface energy, and native point defects. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, P.; Albe, K.; Nieminen, R.M.; Puska, M.J. Intrinsic n-Type Behavior in Transparent Conducting Oxides: A Comparative Hybrid-Functional Study of In2O3, SnO2, and ZnO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 245501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kuklja, M.M.; Stefanovich, E.V.; Kotomin, E.A.; Popov, A.I.; González, R.; Chen, Y. Ab initio and semiempirical calculations of H− centers in MgO crystals. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zakharov, D.M.; Tropin, E.S.; Osinkin, D.A.; Farlenkov, A.S.; Porotnikova, N.M.; Ananyev, M.V. H/D isotopic exchange and electrochemical kinetics of hydrogen oxidation on Ni-cermets with oxygen-ionic and protonic electrolytes. J. Power Sources 2022, 517, 230708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farlenkov, A.S.; Vlasov, M.I.; Porotnikova, N.M.; Bobrikov, I.A.; Khodimchuk, A.V.; Ananyev, M.V. Hydrogen diffusivity in the Sr-doped LaScO3 proton-conducting oxides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 23455–23468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, R.; González, R.; Colera, I.; Vila, R. Protons and deuterons in magnesium-doped sapphire crystals. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1997, 80, 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge, M.A.; González, R.; Popov, A.I.; Pareja, R.; Chen, Y.; Kotomin, E.A.; Kuklja, M.M. The Dynamics of the Hydride Ion in MgO Single Crystals. Defect Diffus. Forum 1999, 169–170, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HF | PBE | B3LYP | Exp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a, Å | 12.19 | 12.34 | 12.34 | 12.12 ÷ 12.34 [2] |

| b, Å | 3.05 | 3.11 | 3.09 | 3.03 ÷ 3.04 [2] |

| c, Å | 5.82 | 5.90 | 5.87 | 5.80 ÷ 5.87 [2] |

| Eg, eV | 13.8 | 2.36 | 4.49 | 4.9 [33] |

| Ecoh, eV | −4.33 | −7.08 | −8.36 | −11.3 [34] |

| ε∞(average) | 2.38 | 3.67 | 3.14 | 3.57, 3.38, 3.53 [34] |

| ε0(average) | 8.06 | 10.61 | 9.6 | 10.2 |

| C11 | C12 | C13 | C15 | C22 | C23 | C25 | C33 | |

| This work (B3LYP) | 235.3 | 123.9 | 138 | −12.8 | 357.2 | 75.8 | 6.9 | 356.5 |

| PBESOL [39] | 208 | 118 | 146 | 0 | 335 | 83 | 0 | 318 |

| Exp [40] | 238 | 130 | 152 | −4 | 359 | 78 | 2 | 346 |

| Exp [41] | 243 | 128 | 160 | −1.6 | 344 | 71 | 0.4 | 347 |

| C35 | C44 | C46 | C55 | C66 | BH | EH | GH | |

| This work (B3LYP) | 12 | 54.7 | 15.2 | 80.9 | 101.4 | 179 | 213.5 | 82 |

| PBESOL [39] | 19 | 50 | 9 | 77 | 96 | 171 | 192 | 73 |

| Exp [40] | 19 | 49 | 6 | 91 | 107 | 184 | 213 | 82 |

| Exp [41] | 1 | 48 | 5.6 | 89 | 104 | 183 | 210 | 80 |

| Mode | This Work | [42] | [43] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | Calc | Calc | Exp | Exp |

| Au(1) | 173 | 155 | 154 | - |

| Bu(1) | 241 | 202 | 213 | - |

| Bu(2) | 280 | 260 | 262 | 272 |

| Bu(3) | 283 | 289 | 279 | 287 |

| Au(2) | 287 | 327 | 296 | 301 |

| Bu(4) | 362 | 365 | 356 | 357 |

| Bu(5) | 434 | 446 | 432 | 448 |

| Au(3) | 457 | 475 | 448 | 486 |

| Bu(6) | 573 | 589 | 572 | 573 |

| Au(4) | 664 | 678 | 663 | 671 |

| Bu(7) | 687 | 705 | 692 | 716 |

| Bu(8) | 737 | 753 | 743 | 774 |

| Defect | Transition | This Work (B3LYP) | Zacherle et al. (HSE06) [12] | Varley et al. (HSE06) [13,17] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO1 | 2+/0 | 4 | 3 | 3.31 |

| VO2 | 2+/0 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| VO3 | 2+/0 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 3.57 |

| VGa1 | 0/1− | 1.49 | 2 | 1.65 |

| 1−/2− | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.9 | |

| 2−/3− | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.3 | |

| VGa2 | 0/1− | 0.74 | 1.3 | 2 |

| 1−/2− | 1.43 | 1.8 | 2.5 | |

| 2−/3− | 2.7 | 2.45 | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Usseinov, A.; Koishybayeva, Z.; Platonenko, A.; Pankratov, V.; Suchikova, Y.; Akilbekov, A.; Zdorovets, M.; Purans, J.; Popov, A.I. Vacancy Defects in Ga2O3: First-Principles Calculations of Electronic Structure. Materials 2021, 14, 7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14237384

Usseinov A, Koishybayeva Z, Platonenko A, Pankratov V, Suchikova Y, Akilbekov A, Zdorovets M, Purans J, Popov AI. Vacancy Defects in Ga2O3: First-Principles Calculations of Electronic Structure. Materials. 2021; 14(23):7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14237384

Chicago/Turabian StyleUsseinov, Abay, Zhanymgul Koishybayeva, Alexander Platonenko, Vladimir Pankratov, Yana Suchikova, Abdirash Akilbekov, Maxim Zdorovets, Juris Purans, and Anatoli I. Popov. 2021. "Vacancy Defects in Ga2O3: First-Principles Calculations of Electronic Structure" Materials 14, no. 23: 7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14237384

APA StyleUsseinov, A., Koishybayeva, Z., Platonenko, A., Pankratov, V., Suchikova, Y., Akilbekov, A., Zdorovets, M., Purans, J., & Popov, A. I. (2021). Vacancy Defects in Ga2O3: First-Principles Calculations of Electronic Structure. Materials, 14(23), 7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14237384