Experimental Investigation of Radiation Shielding Competence of Bi2O3-CaO-K2O-Na2O-P2O5 Glass Systems

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparations

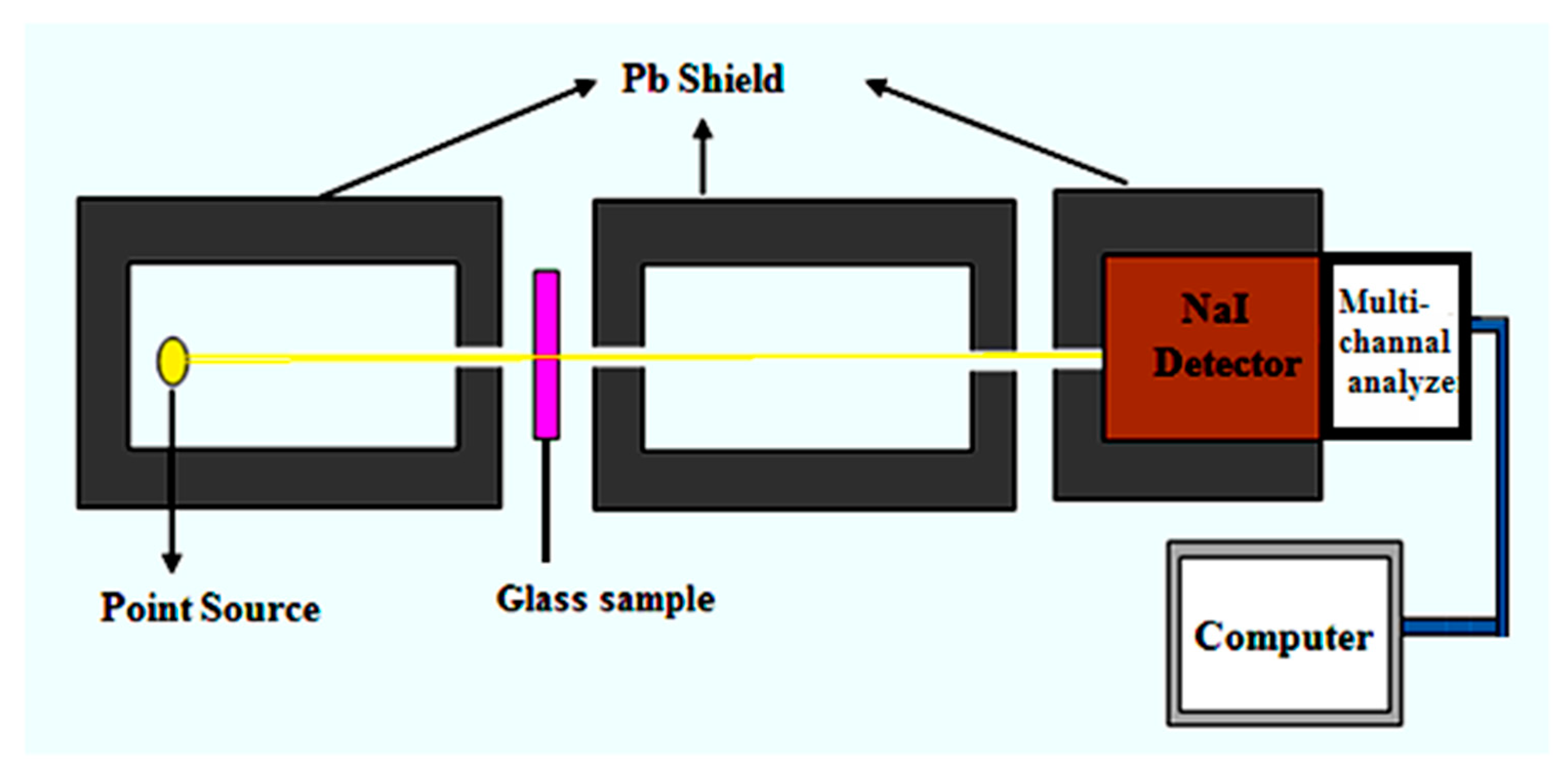

2.2. Measurement of Gamma Ray Shielding Parameters

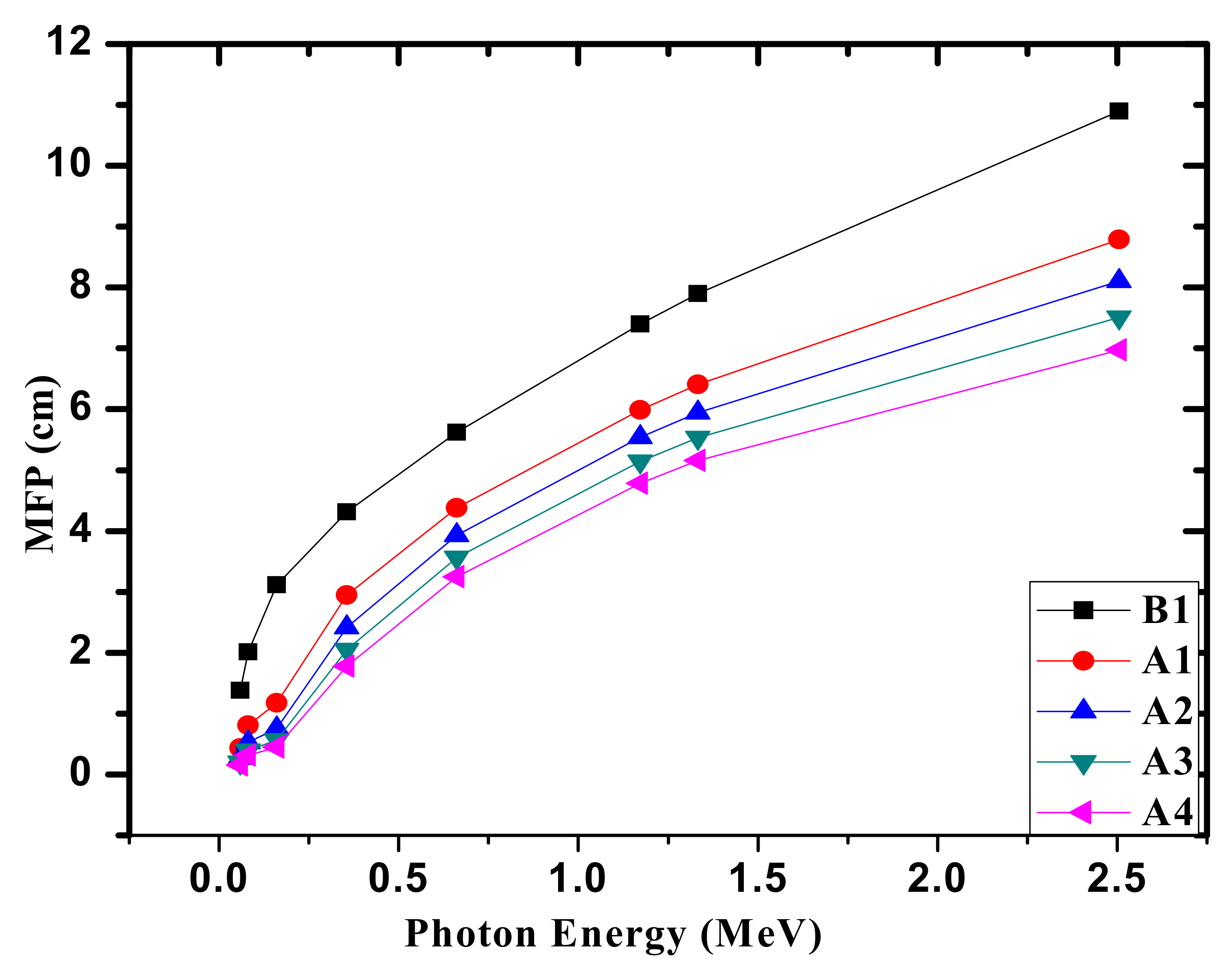

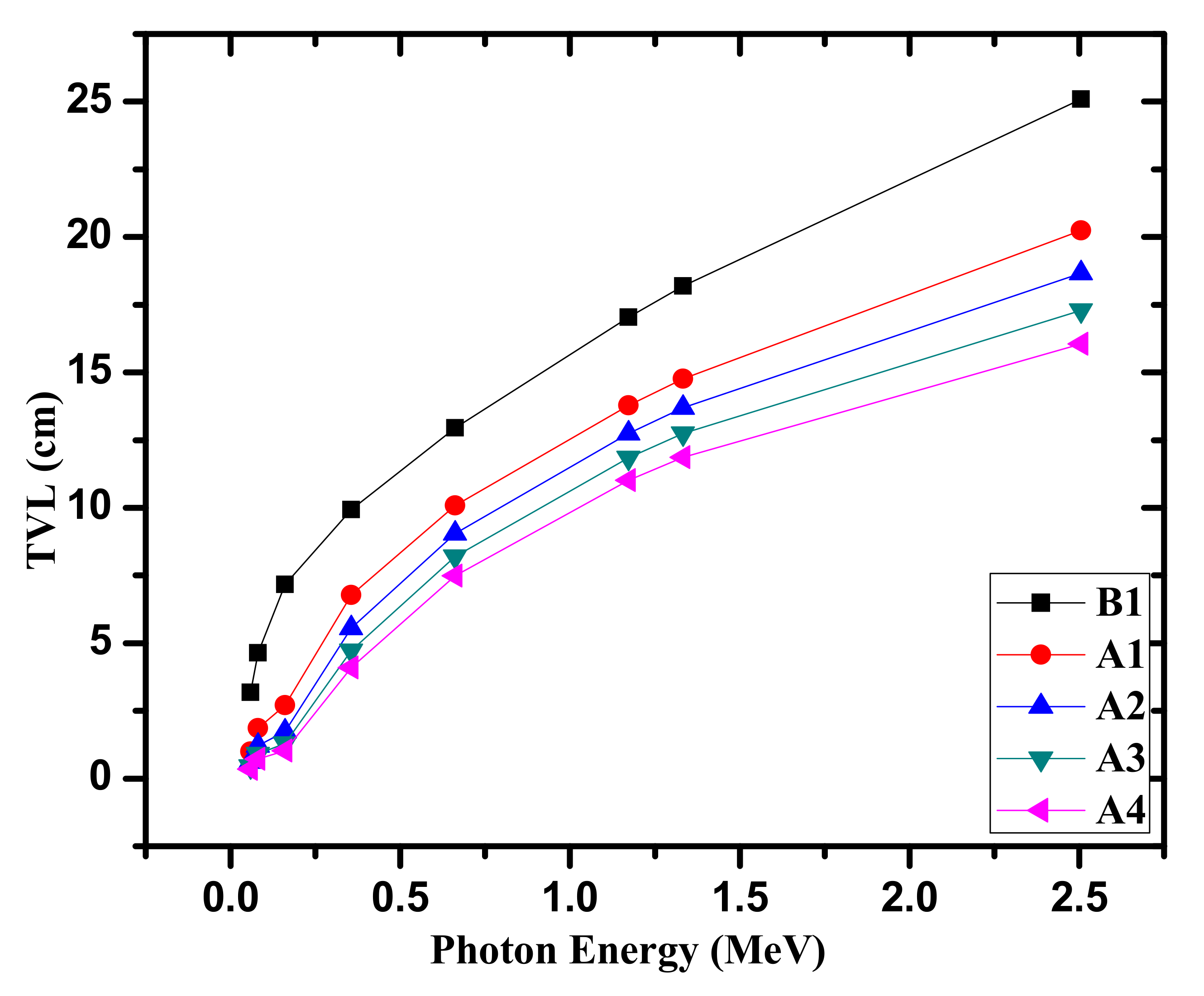

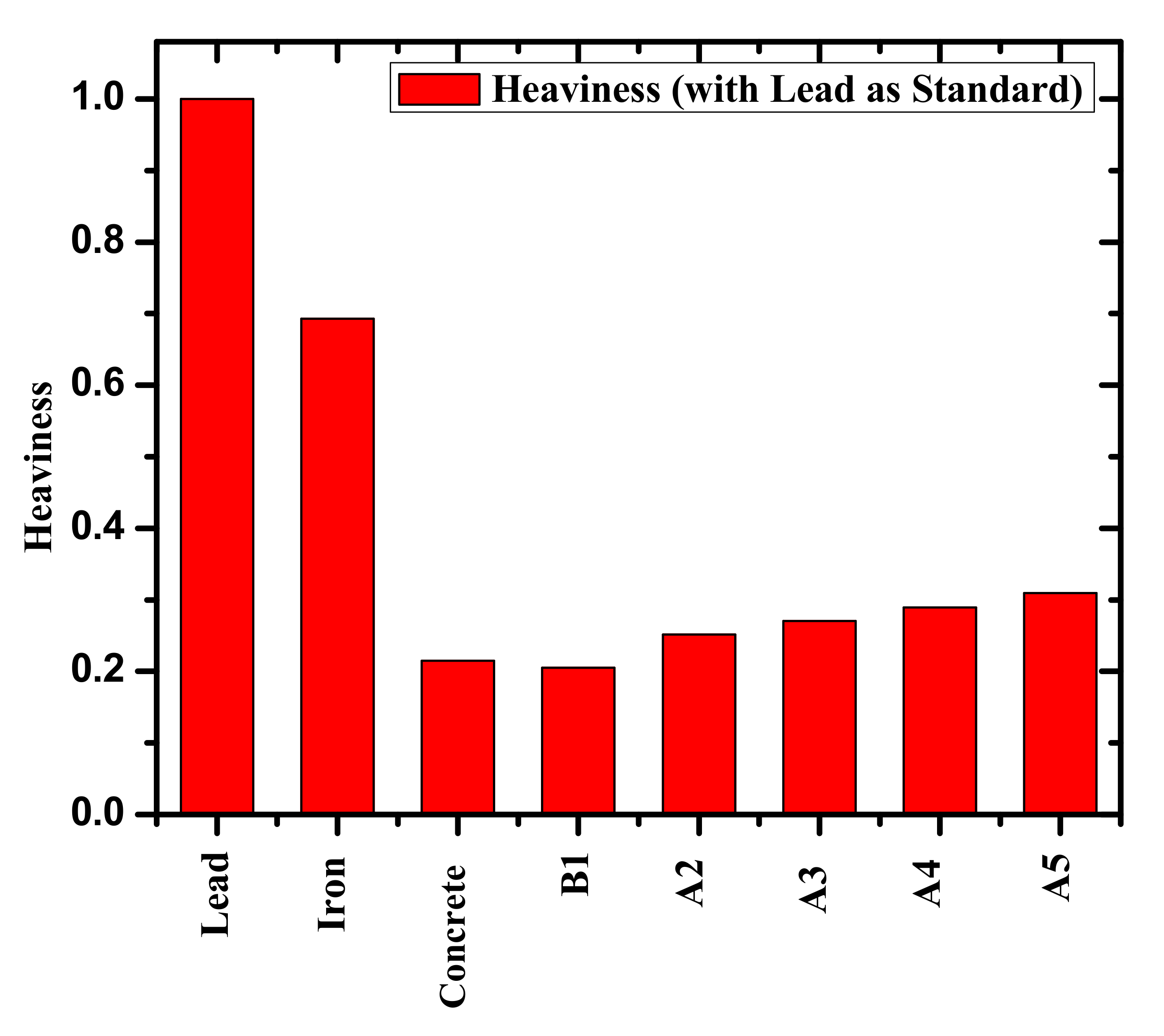

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MAC | mass attenuation coefficient |

| HVL | half value layer |

| Zeff | effective atomic number |

| I0 | Initial intensity |

| I | transmitted intensity |

| fi | molar fraction of the ith constituent element |

| Ai | atomic weight of the ith constituent element |

| Zi | atomic number of the ith constituent element |

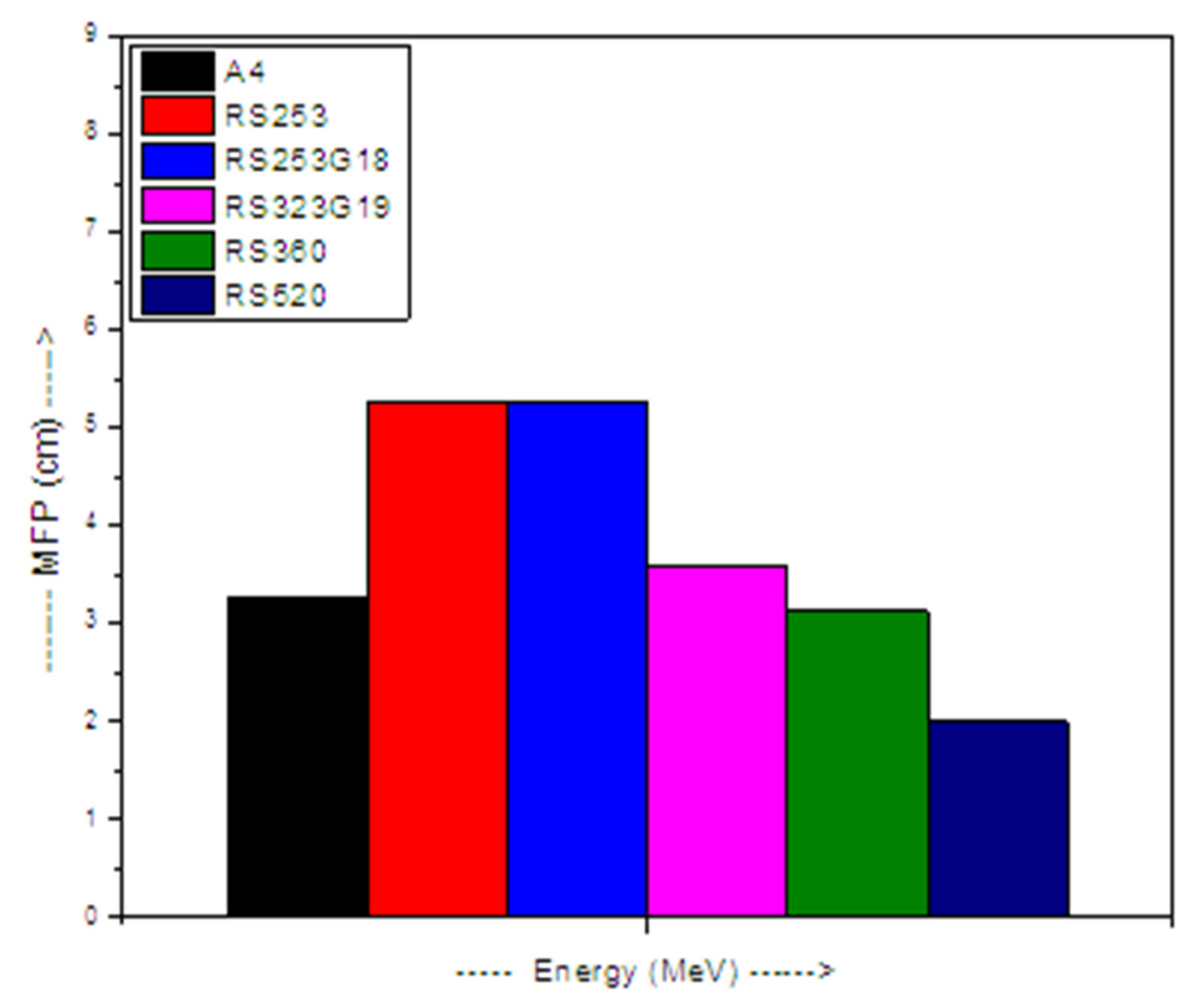

| MFP | mean free path |

| RPE | radiation protection efficiency |

References

- Boukhris, I.; Kebaili, I.; Al-Buriahi, M.; Sayyed, M. Radiation shielding properties of tellurite-lead-tungsten glasses against gamma and beta radiations. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 2021, 551, 120430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zhou, S.; Xue, X.; Feng, X.; Sayyed, M.; Khandaker, M.; Bradley, D. The potential use of boron containing resources for protection against nuclear radiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2021, 188, 109601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Buriahi, M.; Bakhsh, E.M.; Tonguc, B.; Khan, S.B. Mechanical and radiation shielding properties of tellurite glasses doped with ZnO and NiO. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 19078–19083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhaswa, A.; Mhareb, M.; Alalawi, A.; Al-Buriahi, M. Physical, structural, optical, and radiation shielding properties of B2O3-20Bi2O3-20Na2O2-Sb2O3 glasses: Role of Sb2O3. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 2020, 543, 120130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, S.A.; Saddeek, Y.B.; Saddeek, M.I.; Sayyed, H.O.; Tekin, O.K. Radiation shielding features using MCNPX code and mechanical properties of the PbO-Na2O-B2O3-CaO-Al2O3-SiO2 glass systems. Compos. Part B 2019, 167, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Saddeek, Y.B.; Issa, S.A.; Alharbi, T.; Elsaman, R.; Elfadeel, G.A.; Mostafa, A.; Aly, K.; Ahmad, M. Synthesis and characterization of lead borate glasses comprising cement kiln dust and Bi2O3 for radiation shielding protection. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 242, 122510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, O.; Madbouly, A.; Elalaily, N.; Ezz-Eldin, F. Physical properties and radiation shielding parameters of bismuth borate glasses doped transition metals. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 843, 156056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirdsiri, K.; Kaewkhao, J.; Chanthima, N.; Limsuwan, P. Comparative study of silicate glasses containing Bi2O3, PbO and BaO: Radiation shielding and optical properties. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2011, 38, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limkitjaroenporn, P.; Kaewkhao, J.; Limsuwan, P.; Chewpraditkul, W. Physical, optical, structural and gamma-ray shielding properties of lead sodium borate glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2011, 72, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadeethi, Y.; Sayyed, M.I.; Rammah, Y.S. Fabrication, optical, structural and gamma radiation shielding characterizations of GeO2-PbO-Al2O3–CaO glasses. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 2055–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, R.; Adeli, R. Gamma-ray shielding properties of phosphate glasses containing Bi2O3, PbO, and BaO in dif-ferent rates. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020, 174, 108918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, N.; Sayyed, M.I.; Kurtulus, R.; Kamışlıoğlu, M.; Kumar, A.; Alhuthali, A.M.; Kavas, T.; Al-Hadeethi, Y. Understanding the role of Bi2O3 in the P2O5–CaO–Na2O–K2O glass system in terms of physical, structural and radiation shielding properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 11649–11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.I.; Elsafi, M. NaI cubic detector full-energy peak efficiency, including coincidence and self-absorption corrections for rectangular sources using analytical method. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2021, 327, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, M.S.; Noureddine, S.; Kopatch, Y.N.; Abbas, M.I.; Ruskov, I.N.; Grozdanov, D.N.; Thabet, A.A.; Fedorov, N.A.; Gouda, M.M.; Hramco, C.; et al. Characterization of the efficiency of a cubic nai detector with rectangular cavity for axially positioned sources. J. Insturm. 2020, 15, P02013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.I.; Badawi, M.S.; Thabet, A.A.; Kopatch, Y.N.; Ruskov, I.N.; Grozdanov, D.N.; Noureddine, S.; Fedorov, N.A.; Gouda, M.M.; Hramco, C.; et al. Efficiency of a cubic NaI(Tl) detector with rectangular cavity using standard radioactive point sources placed at non-axial position. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2020, 163, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharshan, G.; Aloraini, D.; Elzaher, M.; Badawi, M.; Alabsy, M.; Abbas, M.; El-Khatib, A. A comparative study between nano-cadmium oxide and lead oxide reinforced in high density polyethylene as gamma rays shielding composites. Nucl. Technol. Radiat. Prot. 2020, 35, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, K.; Sayyed, M.; Tashlykov, O. Gamma ray shielding characteristics and exposure buildup factor for some natural rocks using MCNP-5 code. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2019, 51, 1835–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, M.A.; Ahmadi, S.J.; Outokesh, M.; Adeli, R.; Kiani, H. Study on physico-mechanical and gamma-ray shielding character-istics of new ternary nanocomposites. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2019, 143, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçal, M.; Akman, F.; Sayyed, M. Evaluation of gamma-ray and neutron attenuation properties of some polymers. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2019, 51, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.E.; El-Khatib, A.M.; Badawi, M.S.; Rashad, A.R.; El-Sharkawy, R.M.; Thabet, A.A. Fabrication, characterization and gamma rays shielding properties of nano and micro lead oxide-dispersed-high density polyethylene composites. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2018, 145, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammah, Y.; Ali, A.; El-Mallawany, R.; El-Agawany, F. Fabrication, physical, optical characteristics and gamma-ray competence of novel bismo-borate glasses doped with Yb2O3 rare earth. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2020, 583, 412055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuqrin, A.H.; Sayyed, M.I. Radiation shielding characterizations and investigation of TeO2–WO3–Bi2O3 and TeO2–WO3–PbO glasses. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Energy MeV | MAC (B1) | ∆ (%) | MAC (A1) | ∆ (%) | MAC (A2) | ∆ (%) | MAC (A3) | ∆ (%) | MAC (A4) | ∆ (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXP | XCOM | EXP | XCOM | EXP | XCOM | EXP | XCOM | EXP | XCOM | ||||||

| 0.059 | 0.304 | 0.310 | 2.12 | 0.789 | 0.805 | 1.99 | 1.188 | 1.214 | 2.22 | 1.534 | 1.558 | 1.53 | 1.806 | 1.850 | 2.44 |

| 0.081 | 0.209 | 0.213 | 1.9 | 0.443 | 0.433 | −2.3 | 0.603 | 0.614 | 1.88 | 0.750 | 0.767 | 2.21 | 0.883 | 0.897 | 1.52 |

| 0.161 | 0.140 | 0.138 | −1.55 | 0.293 | 0.297 | 1.55 | 0.435 | 0.429 | −1.25 | 0.531 | 0.540 | 1.66 | 0.613 | 0.635 | 3.52 |

| 0.356 | 0.097 | 0.099 | 2.3 | 0.115 | 0.119 | 2.9 | 0.136 | 0.135 | −0.98 | 0.151 | 0.148 | −1.75 | 0.163 | 0.160 | −1.8 |

| 0.662 | 0.074 | 0.076 | 3.5 | 0.079 | 0.080 | 1.55 | 0.081 | 0.083 | 1.66 | 0.084 | 0.085 | 1.66 | 0.089 | 0.087 | −1.46 |

| 1.173 | 0.057 | 0.058 | 0.88 | 0.059 | 0.058 | −1.55 | 0.057 | 0.059 | 3.78 | 0.060 | 0.059 | −1.22 | 0.058 | 0.059 | 2.52 |

| 1.332 | 0.055 | 0.054 | −0.99 | 0.055 | 0.055 | −0.98 | 0.055 | 0.055 | −0.19 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 1.22 | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.92 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aloraini, D.A.; Almuqrin, A.H.; Sayyed, M.I.; Al-Ghamdi, H.; Kumar, A.; Elsafi, M. Experimental Investigation of Radiation Shielding Competence of Bi2O3-CaO-K2O-Na2O-P2O5 Glass Systems. Materials 2021, 14, 5061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14175061

Aloraini DA, Almuqrin AH, Sayyed MI, Al-Ghamdi H, Kumar A, Elsafi M. Experimental Investigation of Radiation Shielding Competence of Bi2O3-CaO-K2O-Na2O-P2O5 Glass Systems. Materials. 2021; 14(17):5061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14175061

Chicago/Turabian StyleAloraini, Dalal Abdullah, Aljawhara H. Almuqrin, M. I. Sayyed, Hanan Al-Ghamdi, Ashok Kumar, and M. Elsafi. 2021. "Experimental Investigation of Radiation Shielding Competence of Bi2O3-CaO-K2O-Na2O-P2O5 Glass Systems" Materials 14, no. 17: 5061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14175061

APA StyleAloraini, D. A., Almuqrin, A. H., Sayyed, M. I., Al-Ghamdi, H., Kumar, A., & Elsafi, M. (2021). Experimental Investigation of Radiation Shielding Competence of Bi2O3-CaO-K2O-Na2O-P2O5 Glass Systems. Materials, 14(17), 5061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14175061