1. Introduction

Aluminum and its alloys are used in a wide range of industrial applications. Duralumins, are employed in the aerospace industry. Due to an ideal combination of low density, high strength, good corrosion resistance, and high resistance to fatigue crack propagation, these special alloys take precedence over other structural materials [

1]. Aluminum alloys of the 2000 and 7000 series are widely used for primary and secondary aircraft structures, such as frames, spares, and ribs, where any damage has a crucial impact on safety.

The high strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu 7475 is an alloy with controlled toughness made in the form of sheets and plates, that has an ideal combination of high strength, good fracture toughness, and resistance to fatigue crack propagation. The 7475 alloy has almost 40% greater fracture toughness than the previous version, 7075 [

2]. This progress in mechanical properties is a result of the reduction of the content of iron, silicon, and magnesium, and application of thermo-mechanical and heat treatments which achieve a refined grain size [

3]. The 7475 alloy, in the form of plates, is usually available in different tempered conditions such as T651, T7351, and T7651 [

4]. However, among modifying the chemical composition of the alloys, the mechanical properties of Al-based alloys can also be enhanced via severe plastic deformation (SPD) methods, including high pressure torsion (HPT) [

5], equal channel angular pressing (ECAP) and its modifications [

6,

7,

8], or rotary swaging (RS) [

9].

As the significant portion of components made of alloy 7475-T7351 are processed by different machining strategies, it is difficult to determine the mechanisms of the severe plastic deformation imposed by the each machining process.

The machining process is generally characterized by chip formation as the direct result of the force interactions between the tool and the workpiece. To achieve chip separation, the stress applied between the tool and the workpiece in the chip formation zone must exceed the ultimate strength of the workpiece material. This force interaction is highly dependent on the studied material, the geometry and material of the tool, the cutting environment, and on the defined cutting conditions. However, during chip formation, three zones of plastic deformation can be always observed: (1) a primary deformation zone in front of the cutting tool edge with extreme shear deformation (

γ = 2–5) and deformation rates (10

3–10

8 s

−1), (2) a secondary deformation zone between the chip and the tool rake face, and (3) a tertiary deformation zone between the machined surface and the tool flank face. In the zone of primary plastic deformation, the chip reaches a high temperature over its entire cross-section (in some cases near to the melting point). As a result of this elevated temperature, the metallurgical and mechanical properties change, the chip softens, the frictional force and the cutting resistance between tool and workpiece decreases, the shear plane angle increases, the chip cross section becomes thinner, and the chip speed increases. In the zone of tertiary plastic deformation, the cutting edge of the tool initiates a stress concentration at the contact zone between the tool and the workpiece [

10,

11,

12]. The machined surface layer is subjected to elastic and plastic deformation at a temperature lower than the temperature of recrystallization. Therefore, material is not melted and any material texture change is permanent and the surface layer is hardened. The imposed force interaction and the thermal load result in residual stress concentration at different depths of the surface layer. These residual stresses can be compressive, increasing the fatigue limit, or tensile, reducing the fatigue limit [

13]; they can also alter other mechanical and utility properties [

14,

15].

As it is well known that nuclei of fatigue cracks are mostly observed on the free surface of the loaded component, all previously described factors have to be taken into consideration while choosing an appropriate machining strategy and machining conditions. Initiation of fatigue cracks on the machined surface is usually closely associated with the combination of severe plastic deformation and the presence of material inclusions or severe plastic deformation and significantly deteriorated surface topography [

16].

Ojolo at al. [

17] presented results of the four-point bending fatigue testing of a end-milled specimen of alloy 2024. The important fatigue life increase (from 2.67 × 10

3 to 3.6 × 10

3 cycles to failure) was observed for samples machined with use of higher cutting speeds (from 3.77 m/min to 48.25 m/min). A decrease of the surface roughness was observed with an increase of the cutting speed, which may be the result of the thermal softening effect due to accumulated heat which caused a temperature rise in the machining zone. The feed speed was described as the most influential factor affecting the fatigue life. The increase of fatigue life was observed with a decrease of the feed speed (from 60 mm/min to 7 mm/min). Surface topography, on the other hand, deteriorated with increase of the feed speed. Ojolo therefore supposed that while using higher feed speeds, the teeth of the end-mill cutter do not perform perfect swiping of the entire surface of the machined zone to make a perfectly smooth surface. It was also observed that an increase in rake angle from 30° to 45° resulted in a better surface finish and increased the fatigue life of the specimens (from 2.53 × 10

3 to 3.49 × 10

3 cycles to failure).

Many other studies have been devoted to determining the effect of machining strategies on the fatigue life. Some have demonstrated the influence of the surface topography. The effect of machining and surface integrity on the fatigue life has been summarized by Novovic et al. [

18]. They reported that a large dispersion of results has been found in the literature; however, fatigue life increase was mostly observed with decreasing surface roughness. Koster [

19] found that for a roughness parameter (

Ra) between 2.5 and 5 μm, the residual stress imposed by the machining process is the most important factor affecting the fatigue life of structural alloys. Koster [

19] also reported that this effect was suppressed by elevated temperature, which allowed relaxation of imposed residual stresses. However, a study of progressive milling technology on the surface topography and fatigue life of aluminum alloy 7475 of Piska et al. [

20] showed that in the case of the presence of material inclusions or secondary phases larger than standard topography parameters (such as average roughness of the profile, maximum depth of the valley of the roughness profile, and others), the effect of the surface topography is usually suppressed.

Regarding ever-increasing safety requirements, it is necessary to carefully analyze the effect of the surface quality, including material structure and surface topography together with residual stresses and severe plastic deformation, imposed by the machining process before releasing components into operation.

This study is, therefore, focused on the influence of the different cutting conditions and tool inclination of the face milling strategy applied on the bottom wing panel made of alloy 7475-T7351 with regard to its fatigue life during operational use. The main goal of this study is therefore to define the milling condition range that allows maintaining the optimum balance between the productivity of the production process, the quality of machined surface, and the required fatigue properties.

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

The aluminum alloy 7475-T7351 in the form of 70 mm thick plates was used in this study. The heat treatment with designation T7351 denotes solution heat treatment at 470 °C, water quenching, controlled stretching, and artificial ageing (over-aged in two stages: first at 121 °C for 25 h, second at 163 °C for a period of 24–30 h). The average chemical composition of the alloy is presented in

Table 1 and its basic mechanical properties are shown in

Table 2.

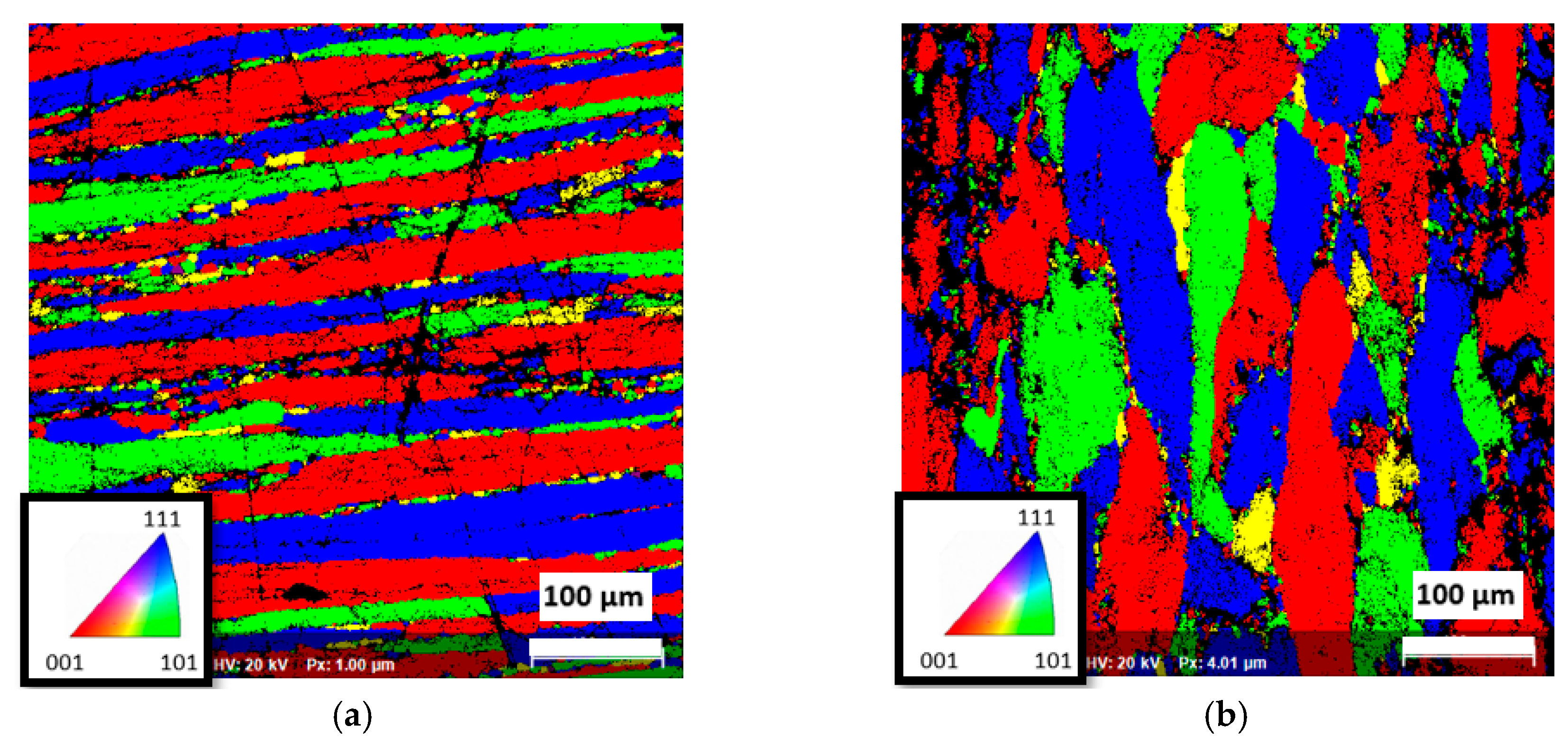

The electron back scattered diffraction mapping (EBSD) study showed a heavily deformed structure with high anisotropy and texture of the grains (and very fine subgrains), as shown in

Figure 1.

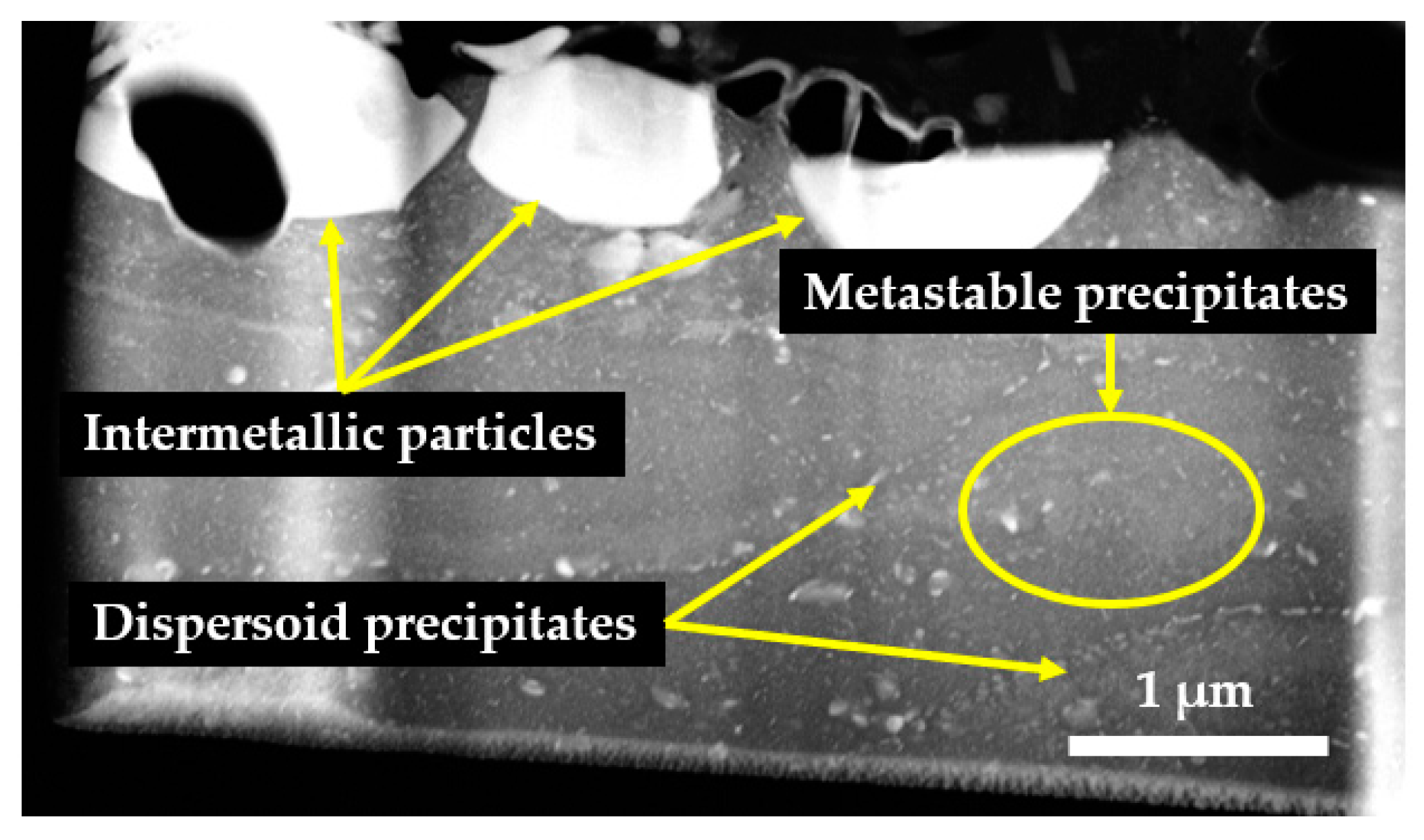

During STEM (Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy) lamella analysis, three different secondary phases have been observed in the material matrix, as indicated in

Figure 2. Coarse intermetallic particles Al-Cu-Fe (possibly Al

7Cu

2Fe) [

21,

22] and Al-Cr-Fe-Cu-Si in the range from 2 µm up to 20 µm were formed during solidification phase. Precipitated Al-Fe-Si and Al-Mg-Cr dispersoids (possibly Al

12Fe

3Si; Al

12Mg

2Cr) were formed by solid state precipitation in the grain boundaries. Third, observed secondary phases can be described as fine metastable precipitates in the material matrix (sizes from 2 nm up to 0.6 µm) and these are responsible for strengthening of the alloy (via

GP,

ή or

η) [

22,

23].

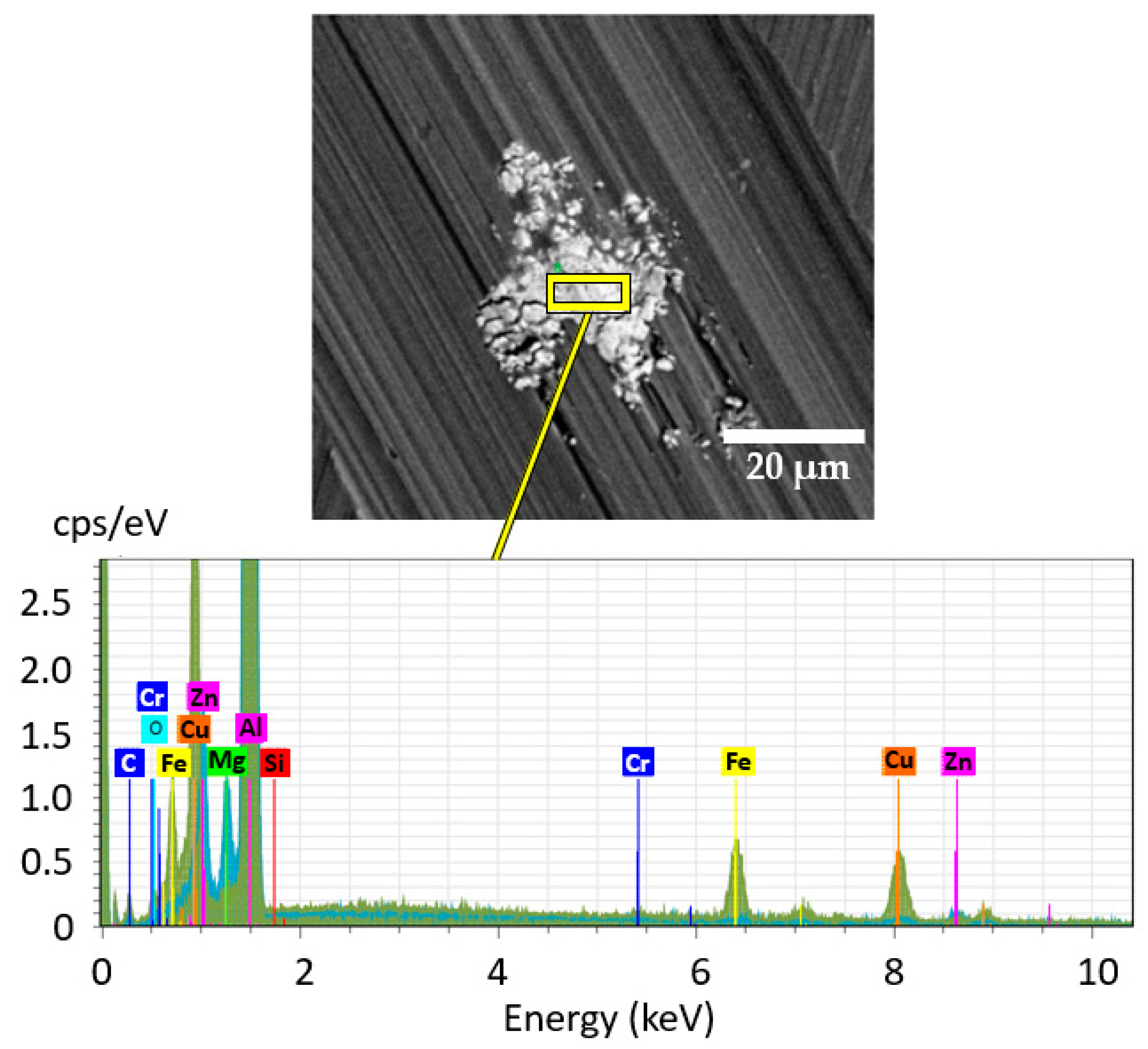

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was used for elemental analysis of the large intermetallic particles, as shown in

Figure 3.

2.2. Tool Geometry

The end-milling whole carbide tool ⌀16×55-115 mm JHF 980 Special provided by SECO Tools company, with (Ti, Al)N coating was used for advanced high feed face milling of the specimens. To exclude any potential impact of inaccurate tool geometry, optical 3D tool geometry analysis was performed using a special software subprogram of the ALICONA-IF G5 optical microscope called “Alicona Edge Master”. The principle of this analysis was a gradual positioning of the reference plane perpendicular to the cutting edges of the tool. The measured results of the intersection of the reference plane with the cutting edges were statistically processed to obtain final results of the mean radius of the mean cutting edges and information about the mean cutting angles.

2.3. Surface Topography Analysis

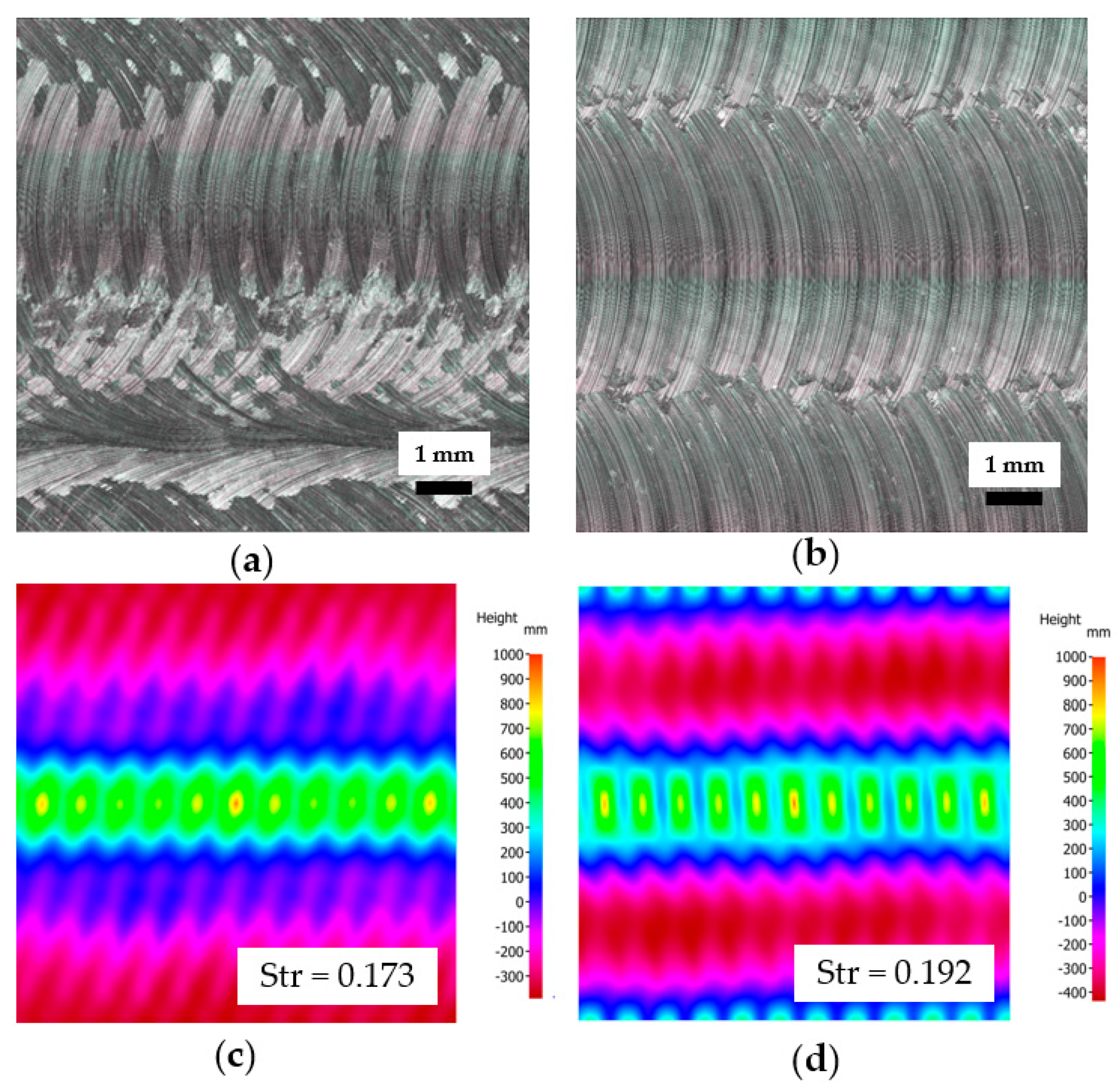

Complex measurement of the surface topography was performed on a set of samples machined by different cutting parameters of face milling, as presented in

Table 3, with the tool positioned perpendicular to the machined surface. Measurement of the surface topography for a set of samples with tool inclination of 1° was also performed. The high-resolution optical microscope ALICONA IF-G5 was used for analysis of roughness parameters (“

R”), waviness parameters (“

W”), Firestone–Abbott parameters, and other advanced 3D surface texture parameters (“

S“). The measurement methodology was based on the combination of the small depth of focus of the optical system with vertical scanning. In order to perform complex detection of the surface, the high-precision optics moved vertically along the optical axis and continuously captured data from the surface. A corresponding algorithm converted the acquired sensor data into 3D information and true colour images with full depth of field [

24]. Nonmeasured points in the datasets were not taken into consideration for further processing or for calculation of corresponding parameters due their low ratio (flat surfaces of samples, good fits of data with the Gaussian distribution, very low occurrence of nonmeasured points in the whole dataset). The measurement methodology was in accordance with the standard EN ISO 25178-606 [

25].

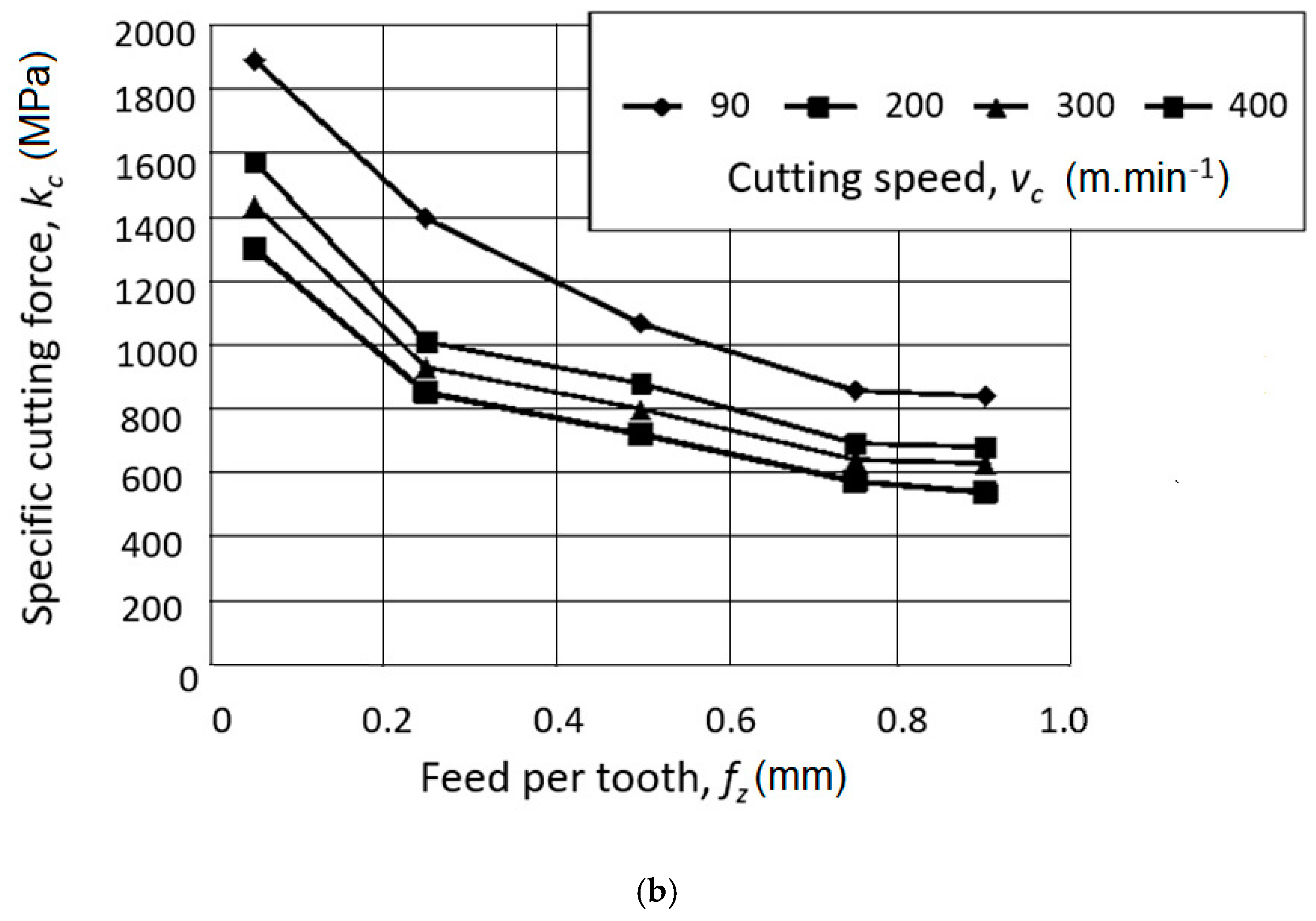

2.4. Force Loading Analysis of High Feed Face Milling and Induced Severe Plastic Deformation

Cutting experiments for various cutting speeds and cutting feeds were carried out with a five-axis milling center MCV 1210/Sinumerik 840D. A stationary KISTLER 957B/SW dynamometer was used for measurement of the force loading during high feed face milling for the different cutting conditions, as presented in

Table 4. The results have been analyzed with DynoWare software (type 2825A, Kistler, Wintherthur, Switzerland), where mean values of the maximal instantaneous force loading in the X, Y, and Z directions were used for graphical determination of the resultant force

F1M and its vector decomposition to the cutting force

FC and the force perpendicular

FCN. The cutting force and non-deformed chip cross section

AD was used for calculation of the specific cutting energy

kc for a given material characterized by the constants

co, the axial depth of cut

ap, the radial with of cut

ae, a angular tooth engagement

ϕ and the effect of chip thickness on specific force loading expressed with the parameter

mc:

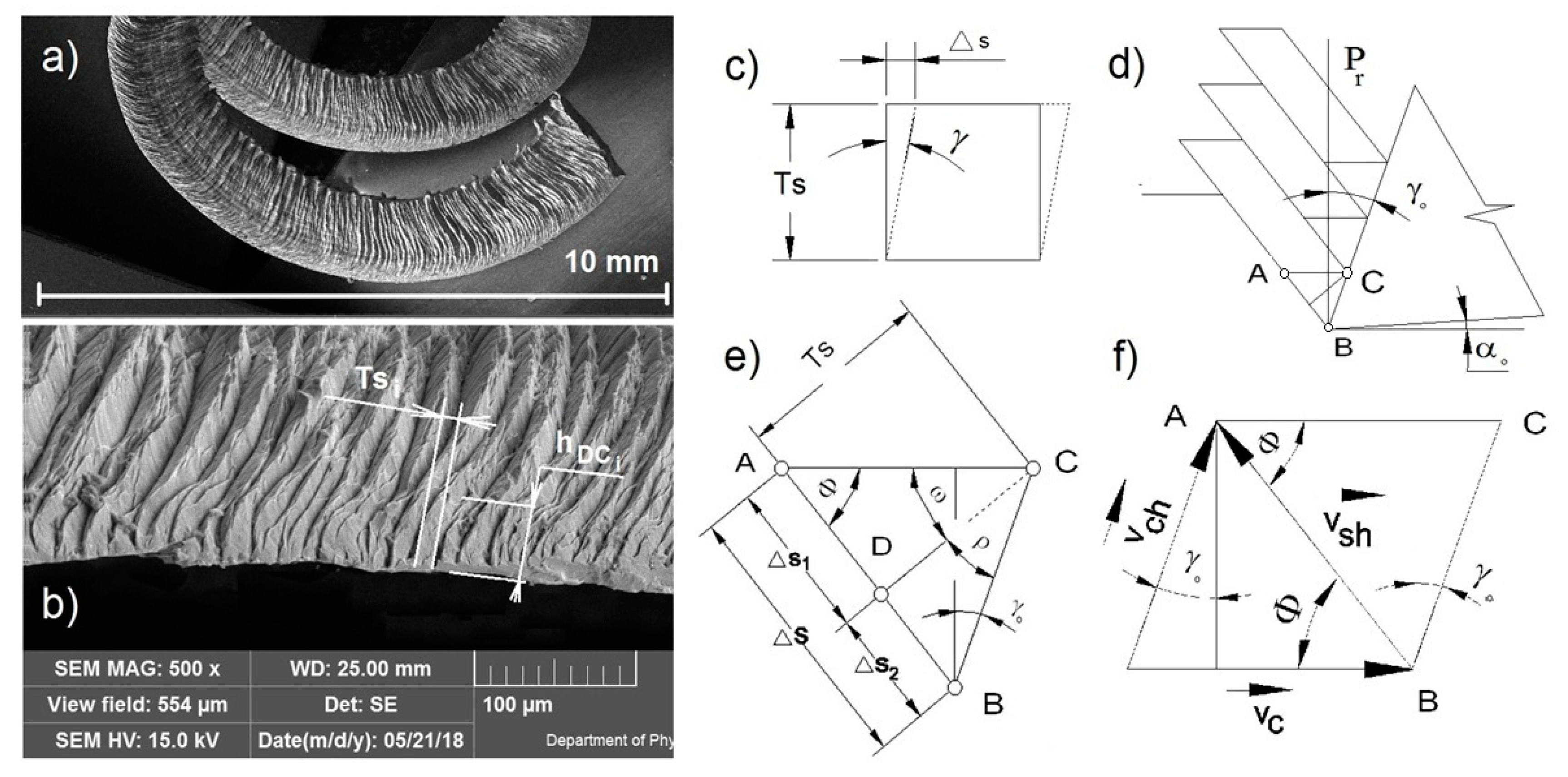

The basic model of continuous chip formation and the individual parameters for shear deformation and rate of the deformation can be seen in

Figure 4.

The plastic flow of the material is defined with the condition of a constant volume of machined material V passing through the first deformation zone and converted to the chip:

where

AD is the cross section of the undeformed material entering with cutting speed v

c and

ADC is the cross section of the material converted to a chip, leaving with speed of chip v

ch. The other variables can be understood according to

Figure 4a–f.

The angle of the shear plane

φ is defined as

where the orthogonal cutting angle

δo is sum of the orthogonal flank angle and orthogonal cutting edge angle

βo, i.e.,

δo = αo + βo, and Λ means the chip thickness coefficient, which is expressed as

The shear deformation

γ in the primary zone can be derived as function of shear angle φ and orthogonal rake angle

γo

and the rate of shear deformation sequentially as

The average thickness

Ts and thickness

hDC of the material lamella can be measured and calculated statistically by electron microscopy, as seen in

Figure 4, and the orthogonal rake angle

γo can be measured with the Alicona G5 microscope. The parameter

hD corresponds to the feed per tooth.

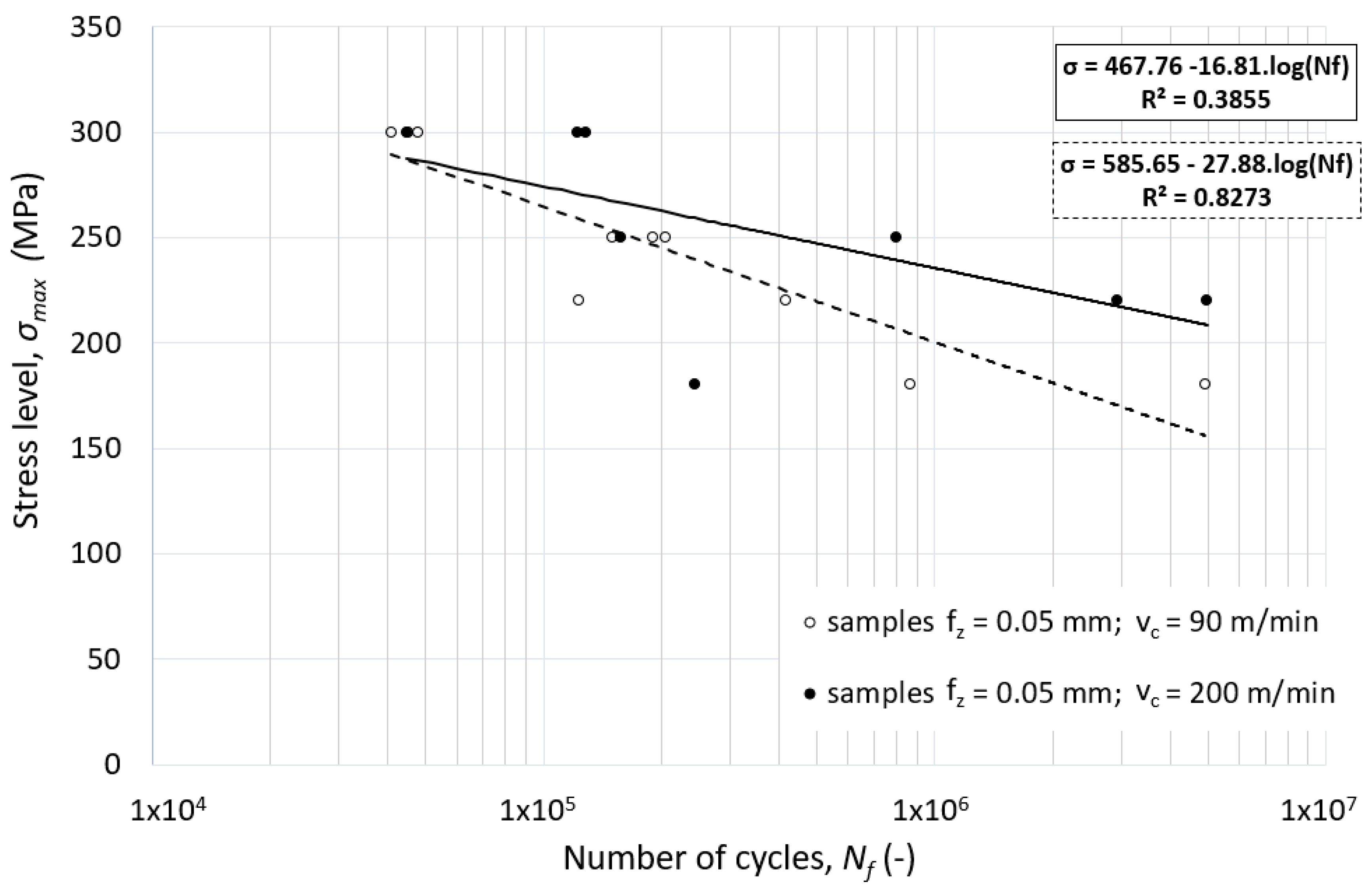

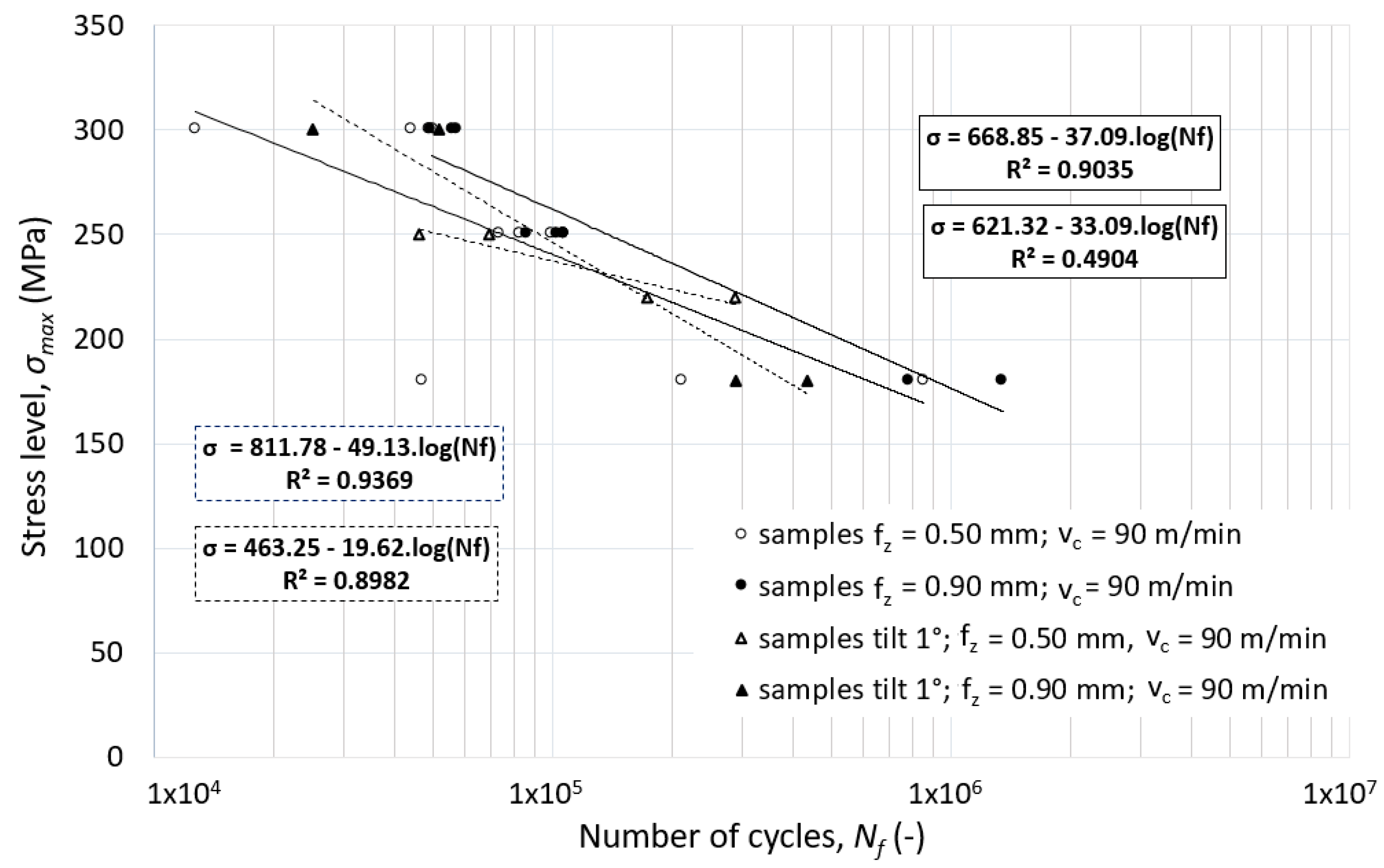

2.5. Fatigue Testing and Frature Surface Analysis

The objective of the fatigue testing was to examine the influence of the defined cutting conditions of the face milling on the fatigue life, as summarized in

Table 5. The effect of tool inclination of 1° has also been examined.

The geometry of the fatigue specimens was chosen to achieve the best match with final operational use of the bottom wing panel. The main criteria for appropriate specimen geometry are defined as follows:

Specimen must allow performance analysis of the effect of the high feed face milling on the fatigue life. Therefore, the flat specimen with largest possible functional area must be chosen.

Specimen must allow simulation of the tensile cyclic loading during operation.

Specimen must comply with ASTM E466-15 [

26] and EN 6072 [

27] aviation standards.

All specimens were oriented in the L-T direction of the rolled plate. Specimens were machined at the five-axis MCV 1210/Sinumerik 840D milling center (TAJMAC ZPS, share company, Zlin, Czech Republic/Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). Specimens were specially protected against bending or torsion during machining, and excess heating was limited by use of CIMSTAR 597 coolant (Cimcool Industrial Products B.V., Vlaardingen, the Netherlands) of 10% volume concentration, 20 bar pressure, and 20 L/min flow rate. All functional areas of the specimens have been protected against scratches, all sharp edges rounded to 0.3 mm radius, and all other stress concentrators have been removed.

Fatigue testing has been performed at special axial testing machine BISS and parameters of the testing are defined as follows:

Fluctuating tensile cycle with stress ratio, R = 0.1.

Frequency, f = 10 Hz.

Stress levels: 180 MPa, 220 MPa, 250 MPa, and 300 MPa.

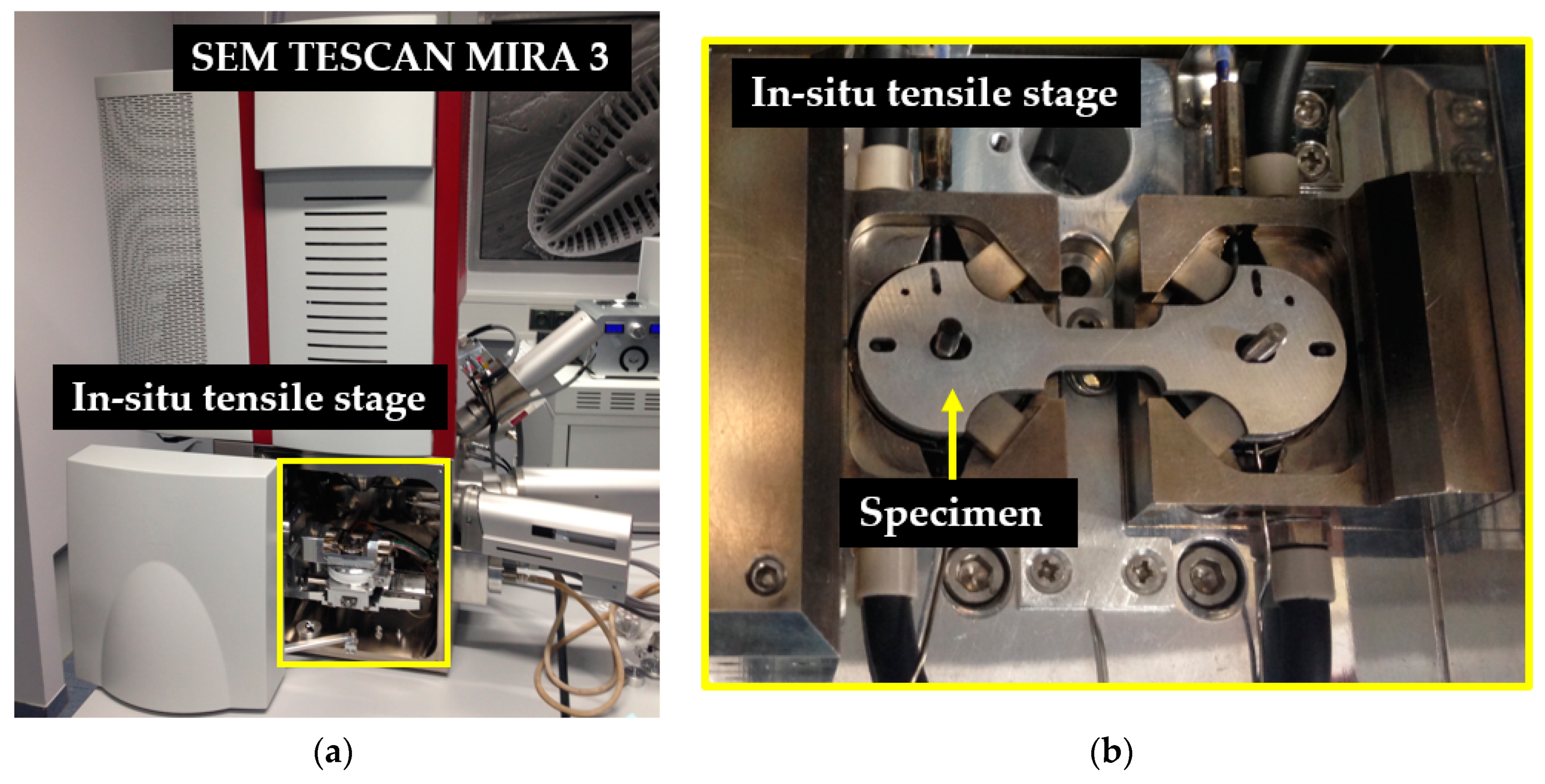

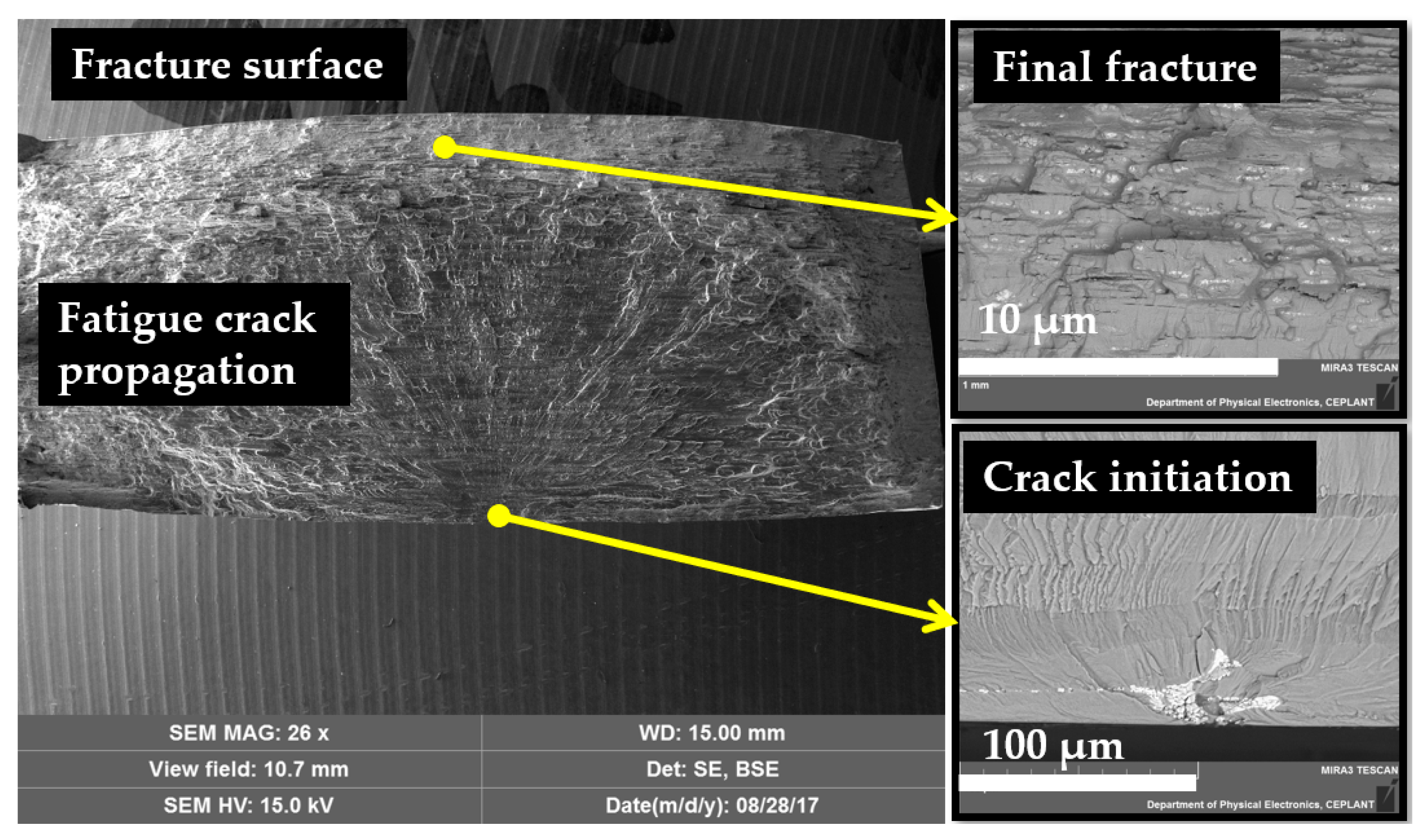

The source of fatigue crack nucleation was examined with the scanning electron microscope (TESCAN ORSAY HOLDING share company, Brno, Czech Republic) TESCAN MIRA 3 operating in both secondary and backscattered electron mode. The fatigue crack initiation and propagation mechanism and the integrity of the adjacent surfaces were investigated.

2.6. In Situ Testing

A specimen with special geometry was designed for in situ tensile mechanical testing. Profiles of the specimen were cut by EDM wire cutting (Electrical Discharge Machining) and polished. Flat functional surface areas were face milled with a special high feed end-mill (SECO tool JHF 980 Special, fz = 0.05 mm, vc = 200 m/min, ap = 0.2 mm), and all sharp edges were rounded and polished.

Testing was performed on a special in situ tensile stage MT1000 made by NewTec (10 kN, a tensile stage) and all analyses were carried out with the SEM TESCAN MIRA 3, equipped with the NewTec SoftStrain software (version 1, NEWTEC, Nîmes, France), as shown in

Figure 5.

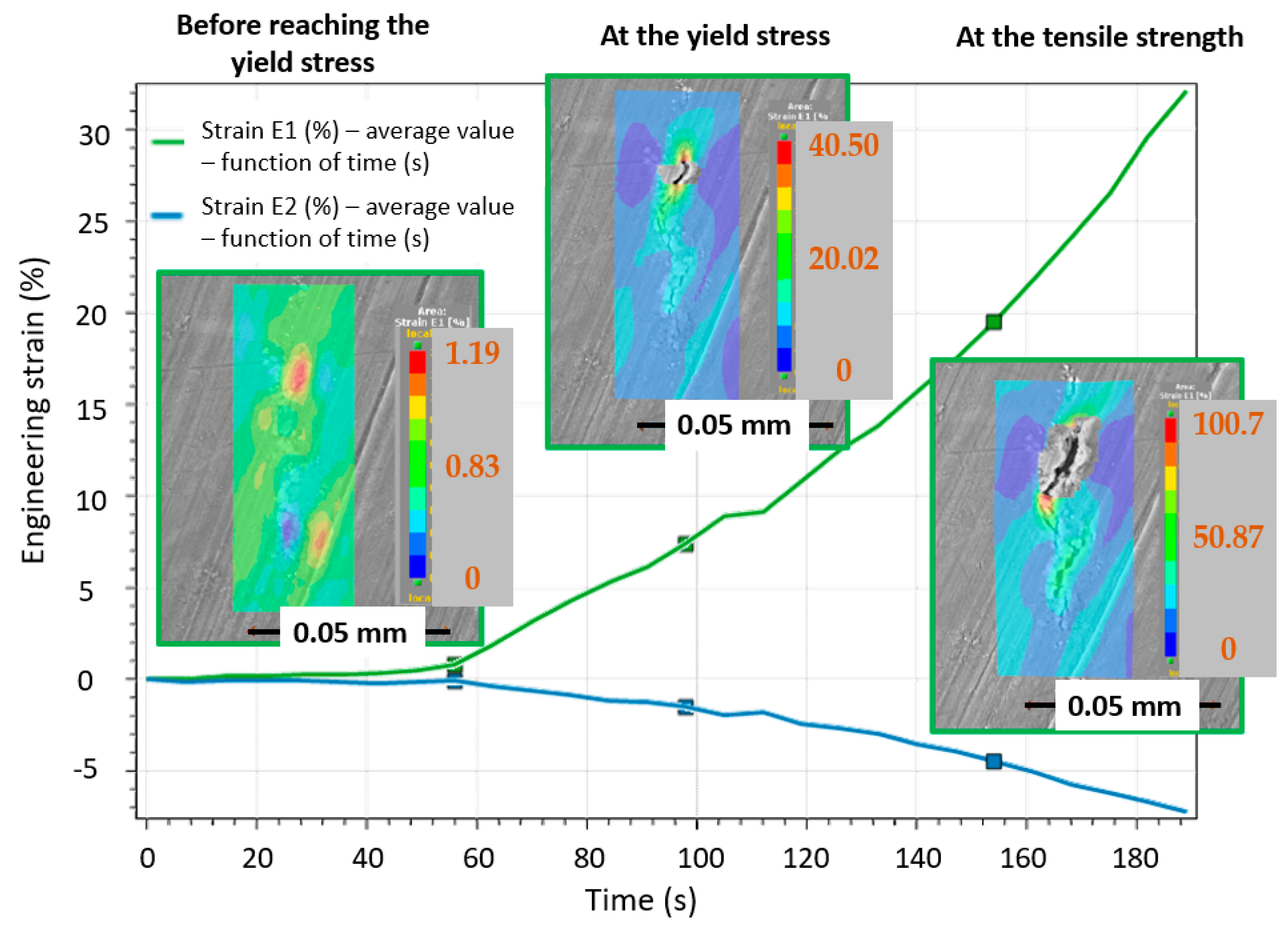

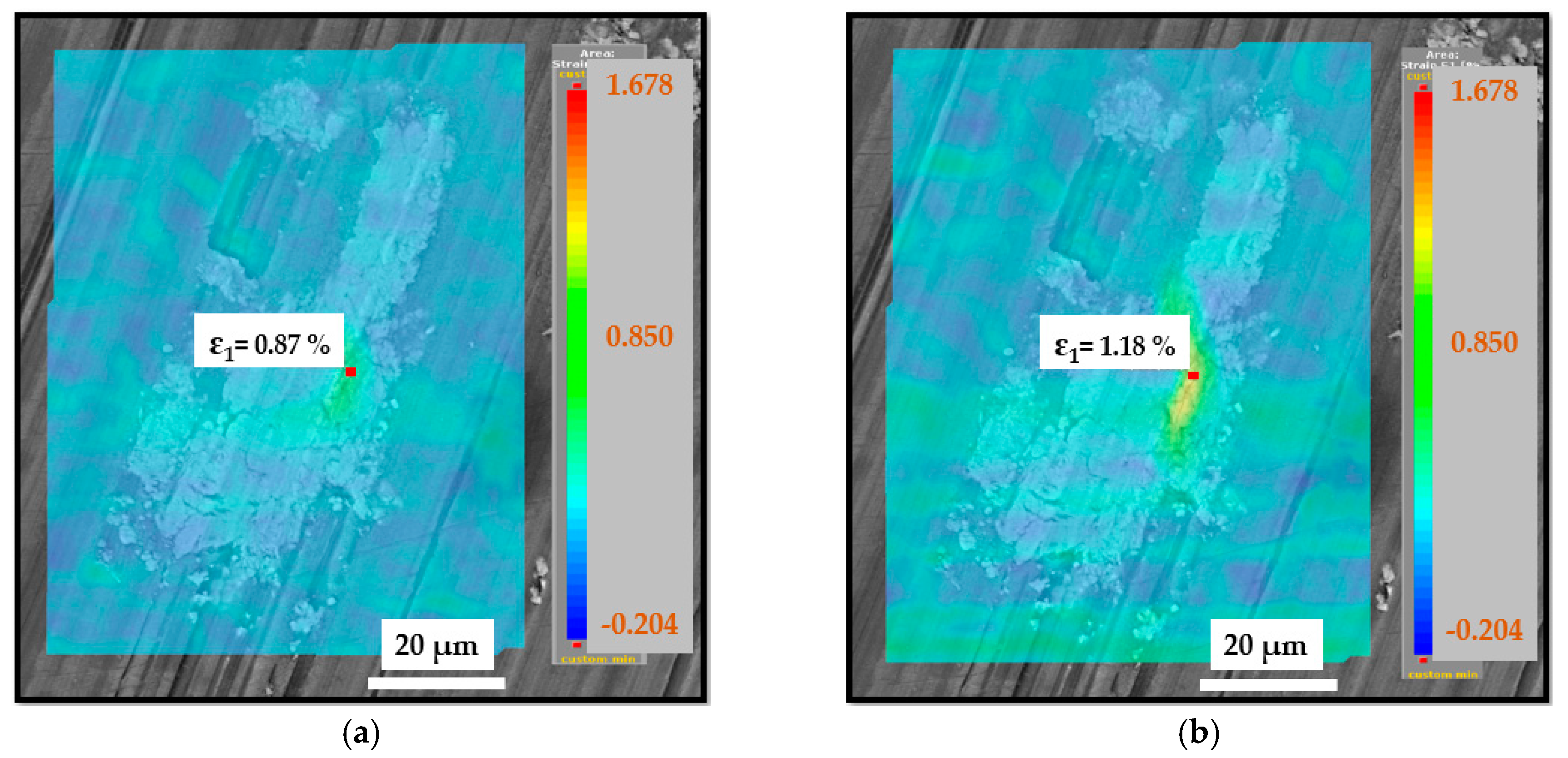

2.6.1. In Situ Tensile Testing

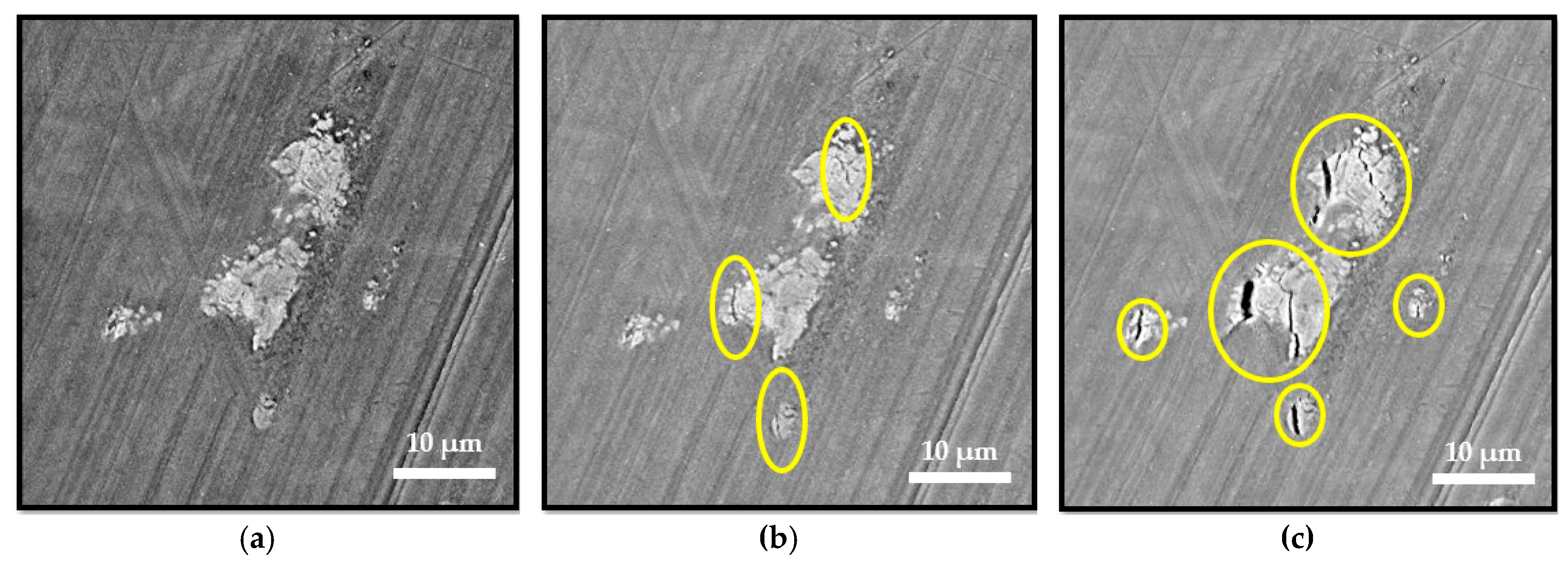

The main scope of the in situ tensile testing was to observe the crack initiation and propagation mechanism in the 7475-T7351 alloy. Two main analyses were performed: (a) Observation of the entire functional area of the specimen; and (b) detailed observation of selected intermetallic particles located at the free machined surface of the specimen. Engineering strain distribution under tensile loading in selected particle was analyzed by DIC (Digital Image Correlation) in MERCURY real-time tracking software.

2.6.2. In Situ Cyclic Testing

The aim of the in situ tensile cyclic loading was to simulate cyclic loading under the operation mode and to observe crack nucleation and short crack propagation. Detailed observation of twenty selected large intermetallic particles was performed in parallel. Parameters of the fatigue loading were defined as follow:

4. Discussion

The observations from the experimental machining, surface analyses, and fatigue testing confirm similar results as those of Ojolo et al. [

17] and Novovic et al. [

18].

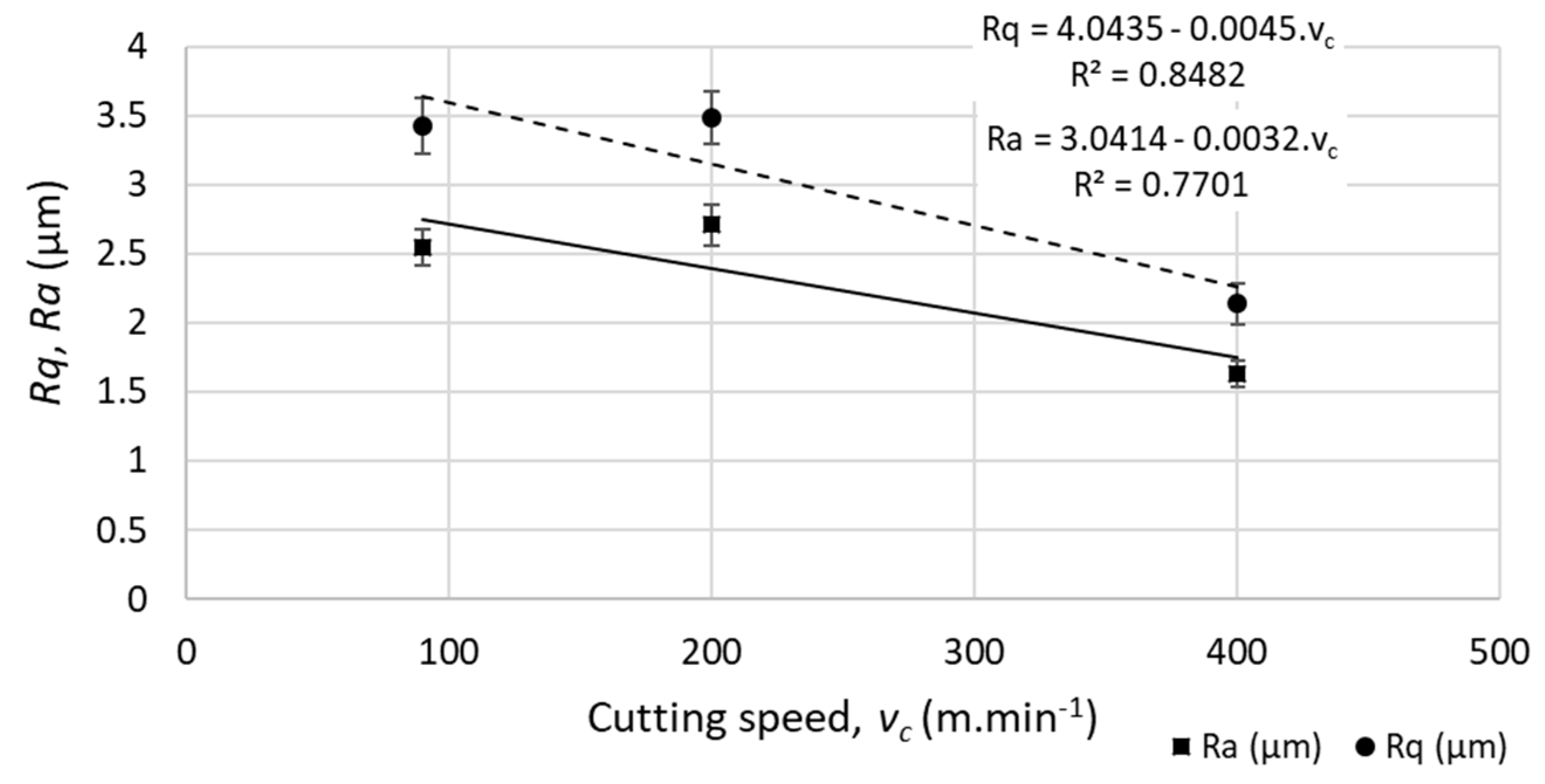

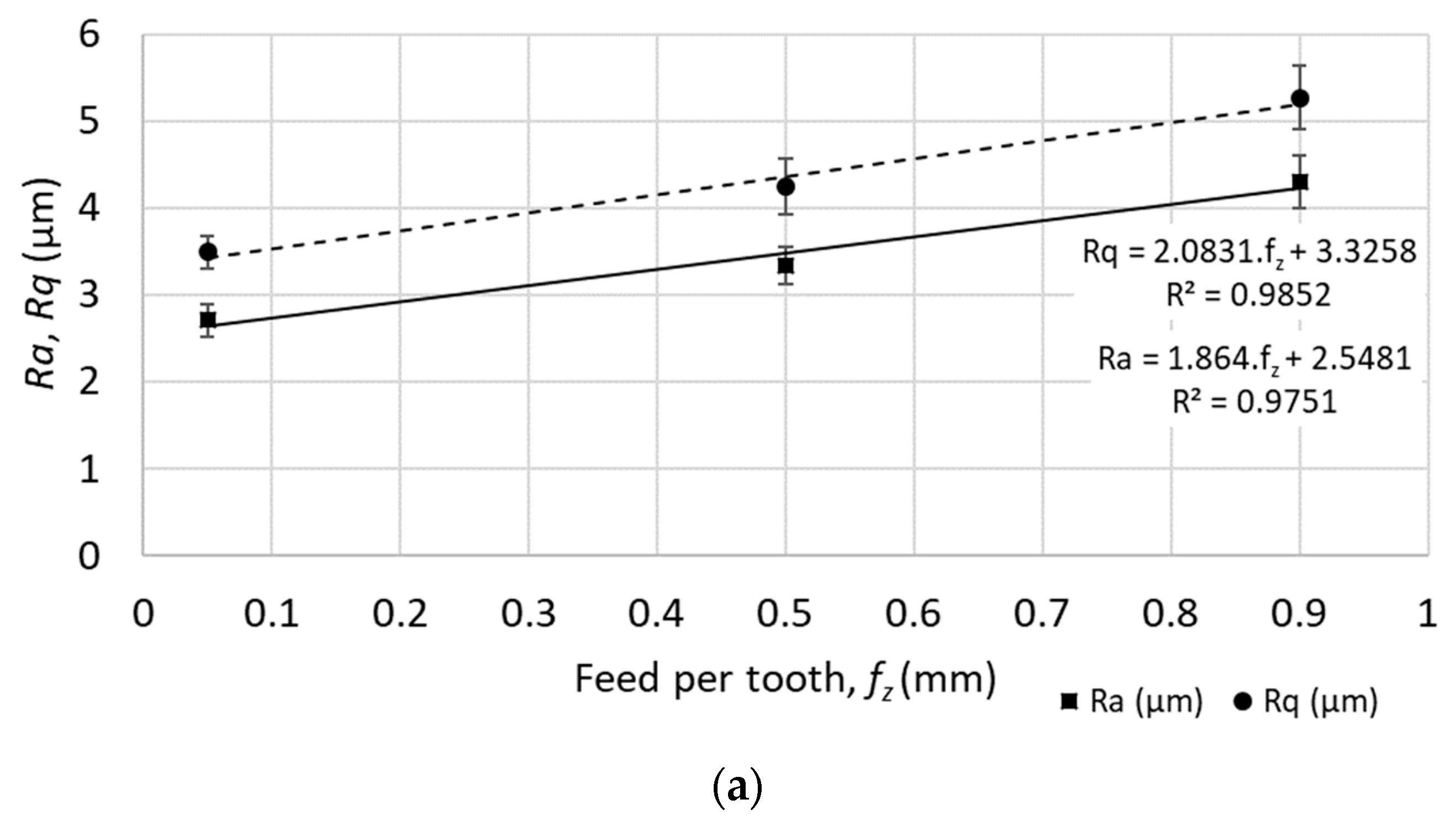

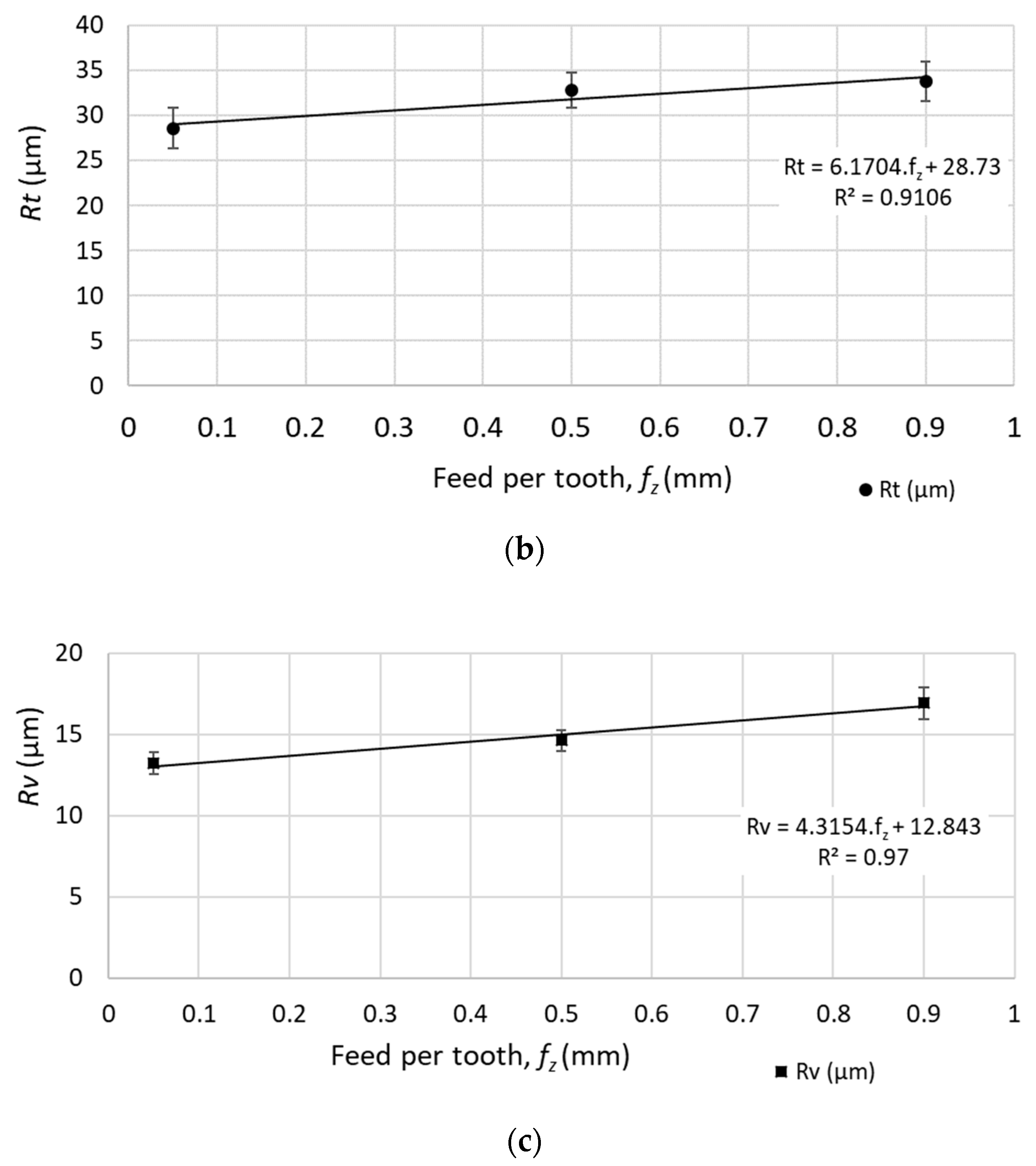

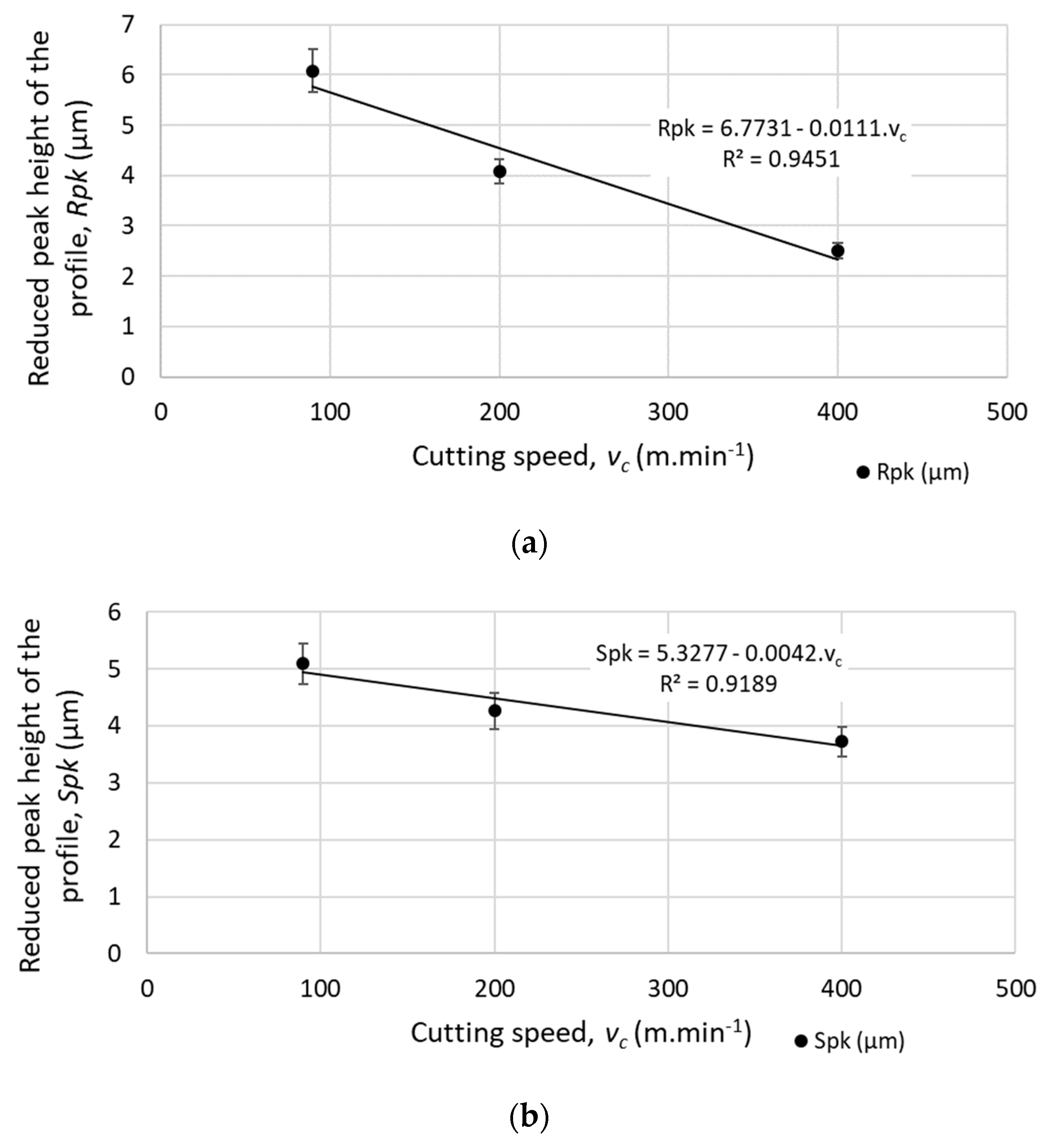

Surface topography analysis confirmed that the roughness parameters increase with the increase of the feed speed (feed per tooth). The increase of the cutting speed caused a decrease of the surface roughness parameters. This result partially confirms the observation of Ojolo et al. [

17].

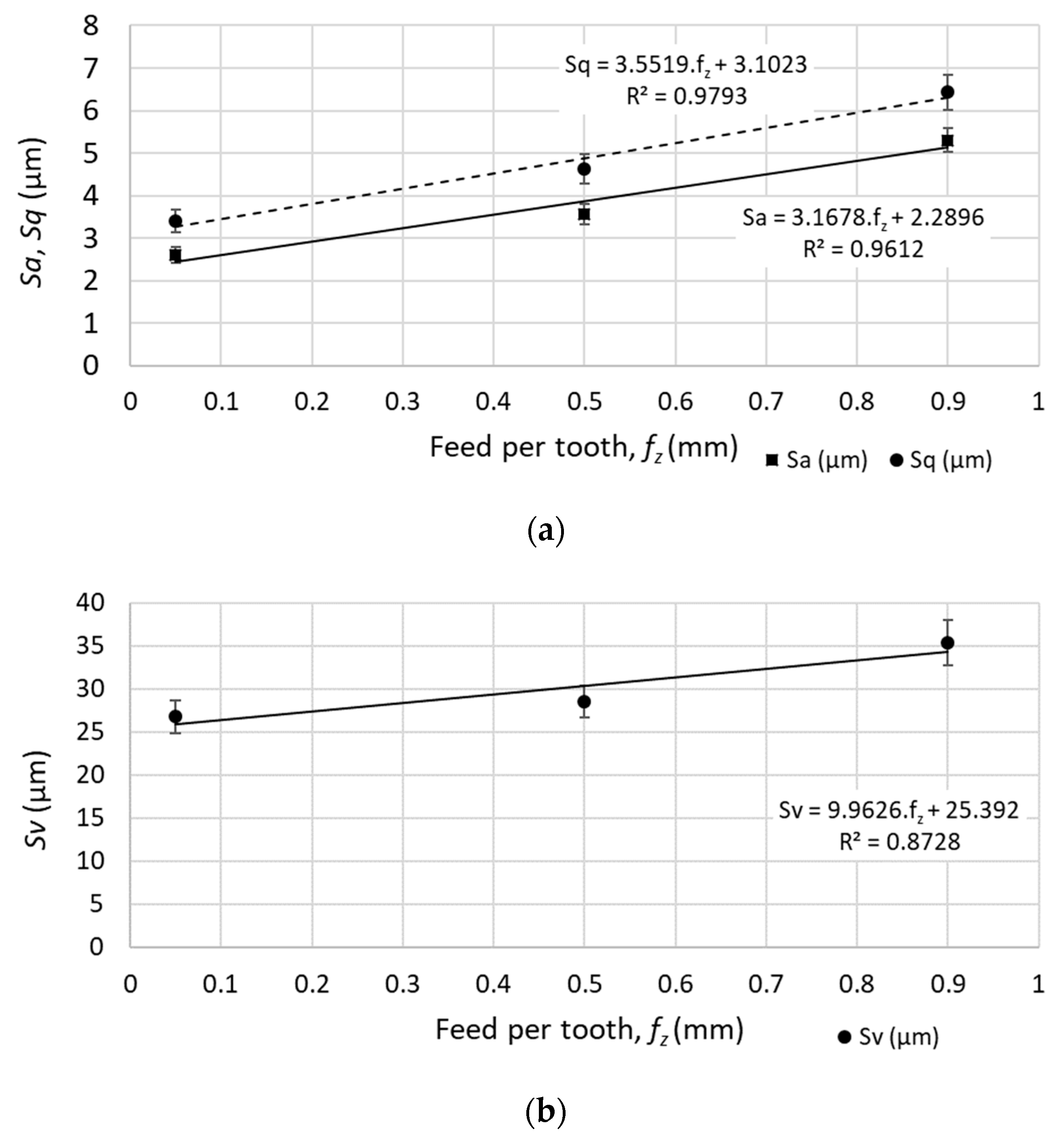

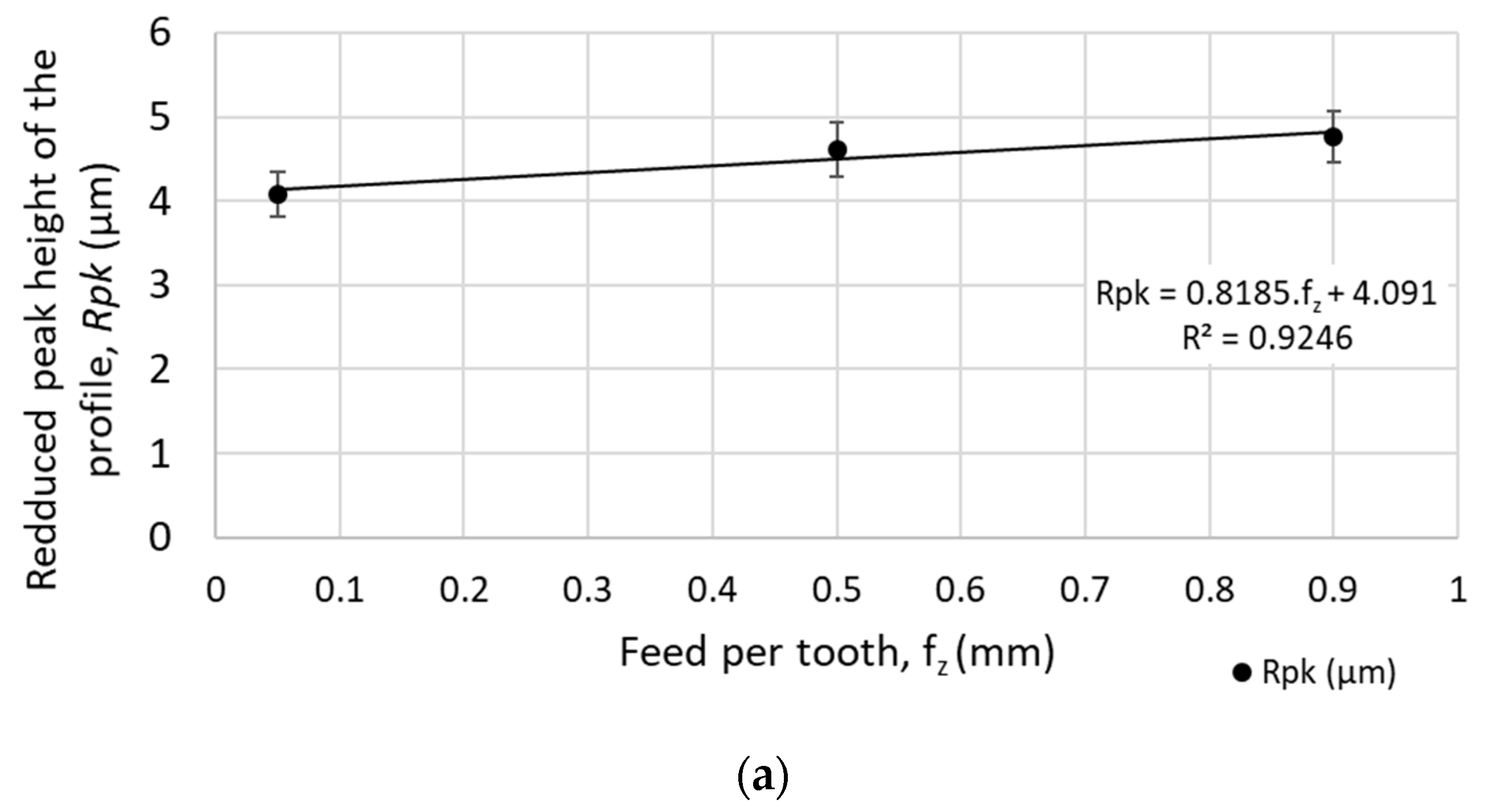

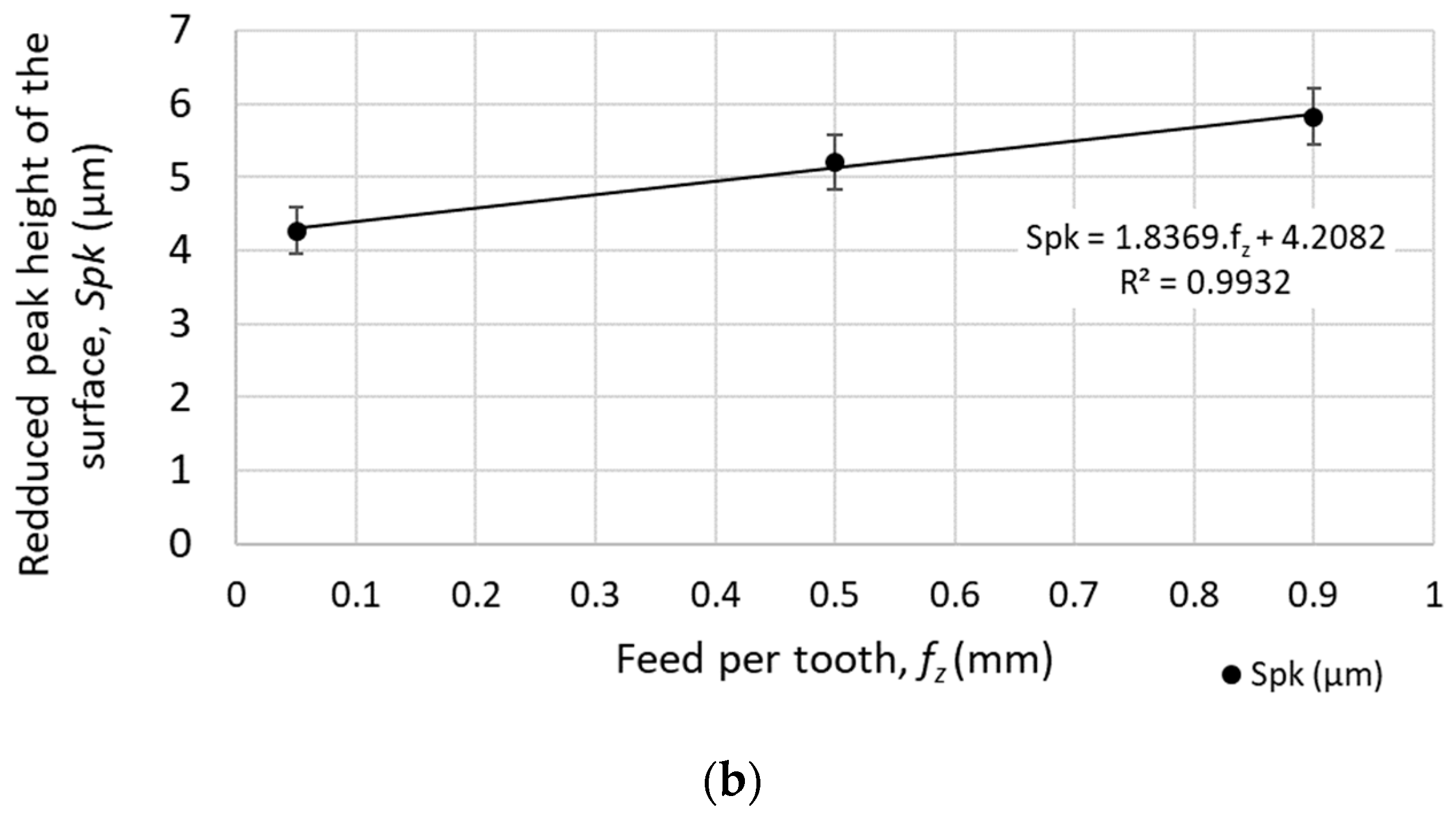

The increase of the feed speed increases surface topography parameters such as average height of the selected area (Sa), root-mean-square height of the selected area (Sq), or maximum valley depth of the selected area (Sv). The roughness parameters were found to be similar for both strategies (perpendicular and inclined by 1°); however, a greater increase of roughness parameters was observed while using higher feed speeds for samples machined with the tool inclined by 1°. The average height of the selected area (Sa) showed higher values for samples machined with the tool inclined by 1°. This parameter was not adequate, considering that maximum valley depth of the selected area (Sv) was higher for samples machined by a tool positioned perpendicularly to the machined surface.

The trends of specific cutting force and shear deformation confirm a reduction of plastic deformation with increasing cutting speed, but more intensive deformation with reduction of feed per tooth. In other words, the intensity of plastic deformation is higher for shallow cuts and higher cutting speeds.

The highest fatigue resistance was observed at samples machined with the highest cutting speed (vc =200 m.min−1) and lowest feed per tooth (fz = 0.05 mm). A decrease of the fatigue life of specimens machined with higher feed rates while keeping the same cutting speed was observed (increase from feed per tooth fz = 0.05 mm to fz = 0.90 mm). This decrease of the fatigue life may be caused by the severe plastic deformation achieved in the smallest chip cross sections and machined at the highest cutting speeds (vc = 200 m.min−1).

Slight inclination of the cutting tool (1°) resulted in reduction of the total cycles for specimens machined with cutting speed vc = 90 m.min−1 and different feed speeds. This reduction may be caused by plastic deformation caused by teeth not engaged in the cut, as in the case of face milling perpendicular to the machined surface. This plastic deformation may impose beneficial compressive residual stresses into the machined surface and thus increase the fatigue life.

Therefore, the cutting conditions can affect the material removal rate, but a more serious impact can be seen in terms of the surface quality and the resistance to mechanical loading. The effect of inclusions is very serious, and materials used for dynamic loading should be carefully analyzed not only in view the surface integrity, but also considering the occurrence of the phases, which confirms the results of Piska et al. [

20]. The effect of material hardening and thermal softening when cutting should be studied further in terms of the density and arrangement of dislocations, stacking fault energy, and other atomic hardening or softening mechanisms.