1. Introduction

To prevent replacement of high-price sensitive metal products such as turbine blades, rotor shafts, tools and moulds, Additive Manufacturing is growing [

1,

2]. The driving idea is to provide additional metal over worn-out surfaces to restore nominal dimensions, thus preventing part disposal.

In this framework, a number of laser-based methods have been employed in demanding environments such as aerospace, defense, petrolchemical and nuclear industries [

3,

4]. In Directed Energy Deposition (DED), a laser beam is used as a heat source to scan the surface: a melting pool over an existing substrate is created and metal impinging of the pool is fed concurrently (i.e., in single stage processing) [

5]. A deposited metal trace results, with metallurgical bonding to the substrate thanks to fusion and diffusion. Resistance metallic coatings can be laid [

6]; functionally graded material parts can be manufactured by means of a dual powder feeding system [

7]; and the fabrication of a 3D part is even possible by means of layer-by-layer deposition of consecutive, overlapping traces [

8]. Reduction of waste is benefited in comparison with subtractive technologies [

9]. Different names have been given to the same technology, depending on the Authors or the company [

10].

In general, a number of advantages are reported in DED with respect to conventional welding technologies for repairing, such as tungsten inert gas or gas metal arc [

5,

11]. As focused heat is provided, thermal affection and residual stresses are reduced, and precision and production flexibility are enhanced [

3]. New opportunities are hence expected for parts of complex geometry and difficult-to-cut materials [

12].

At present, both powder and wire are being considered as feedstock. It is worth noting that metallic wires are considered to be easier to stock and to produce in comparison with powder [

13]; on the other hand, process stability, proper surface quality, bonding strength and soundness are reported to be challenging [

14]. Since powder feeding has been proven to be flexible in materials [

15], as well as robust and effective, several studies in the literature have discussed the outcome as a function of the processing parameters [

16,

17].

Regarding steel deposition in the form of powder, the influence of the particle size distribution on the resulting relative density has been investigated [

18]. Interestingly, since the cost of metal powder is among the main barriers in DED, the feasibility of a raw feedstock consisting of coarse and irregular steel swarf or chips resulting from machining has been proposed [

19].

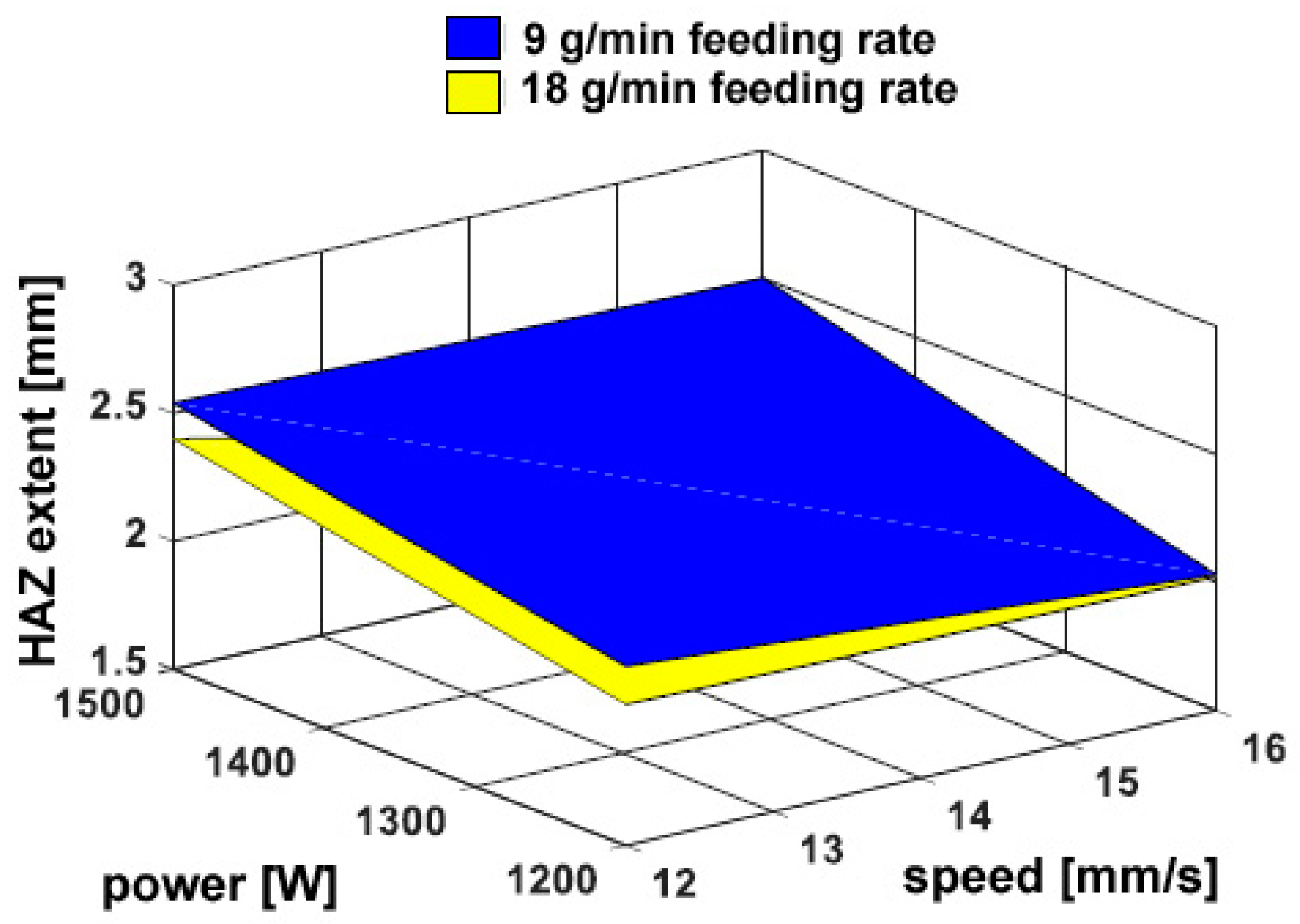

Clad thickness, depth of penetration and extent of the heat-affected zone (HAZ) are governed by the main parameters such as the laser power, the scanning speed and the specific energy of the beam [

5,

6]. In addition, depending on the carbon content and irrespective of the feedstock form [

20], martensitic transformation occurs in the base metal [

21], i.e., the microstructure morphology in terms of grain size and the mechanical properties in turn [

22] have been found to definitely depend on solidification velocity and the temperature gradient as a consequence of the processing parameters [

23], mainly the scanning speed [

10]. The latter has been reported to significantly influence dilution [

3], i.e., the percentage index of the affection of the substrate with respect to the reported metal [

11]. Minor porosity and micro-cracking have been observed [

6] due to residual thermal stresses, although these are not deemed to result in rejection of parts during quality checks when referring to usual international or customer standards for quality in laser welding [

24], since no specific regulations are available at present for DED [

25].

It is worth noting that, as for any emerging technology in the industry [

26,

27], flexible thermal modeling is crucial to prevent the usual trial-and-error approach. Indeed, much effort has been made in the literature to model the process of DED in terms of resulting geometry and induced thermal cycles [

28].

Numerous studies have been conducted over flat surfaces. These results are suitable for actual applications in repair process chains, where damaged areas or cracks are preliminarily removed by milling, then reconditioned with new material deposition [

29]. Nevertheless, processing of sharp edges is required to be investigated as well, since this processing configuration is expected to be useful in many applications, e.g., for the purpose of overhauling cores and mould sections for investment casting. As a consequence, deposition over both flat surfaces and corners has been considered in this paper.

2. Materials and Methods

A base metal corresponding to standard UNS S43100 chromium-nickel stainless steel in terms of nominal chemical composition (

Table 1) has been considered. Pre-alloyed, spherical shaped, gas-atomized virgin commercial powder of the same composition has been used; the particle size ranges from 20 µm to 60 µm. Since a steady feeding rate must be provided consistently [

11], the powder has been preliminary dried, in furnace, 180 °C, 2 h, to flow properly via an antistatic conveyor to the working area.

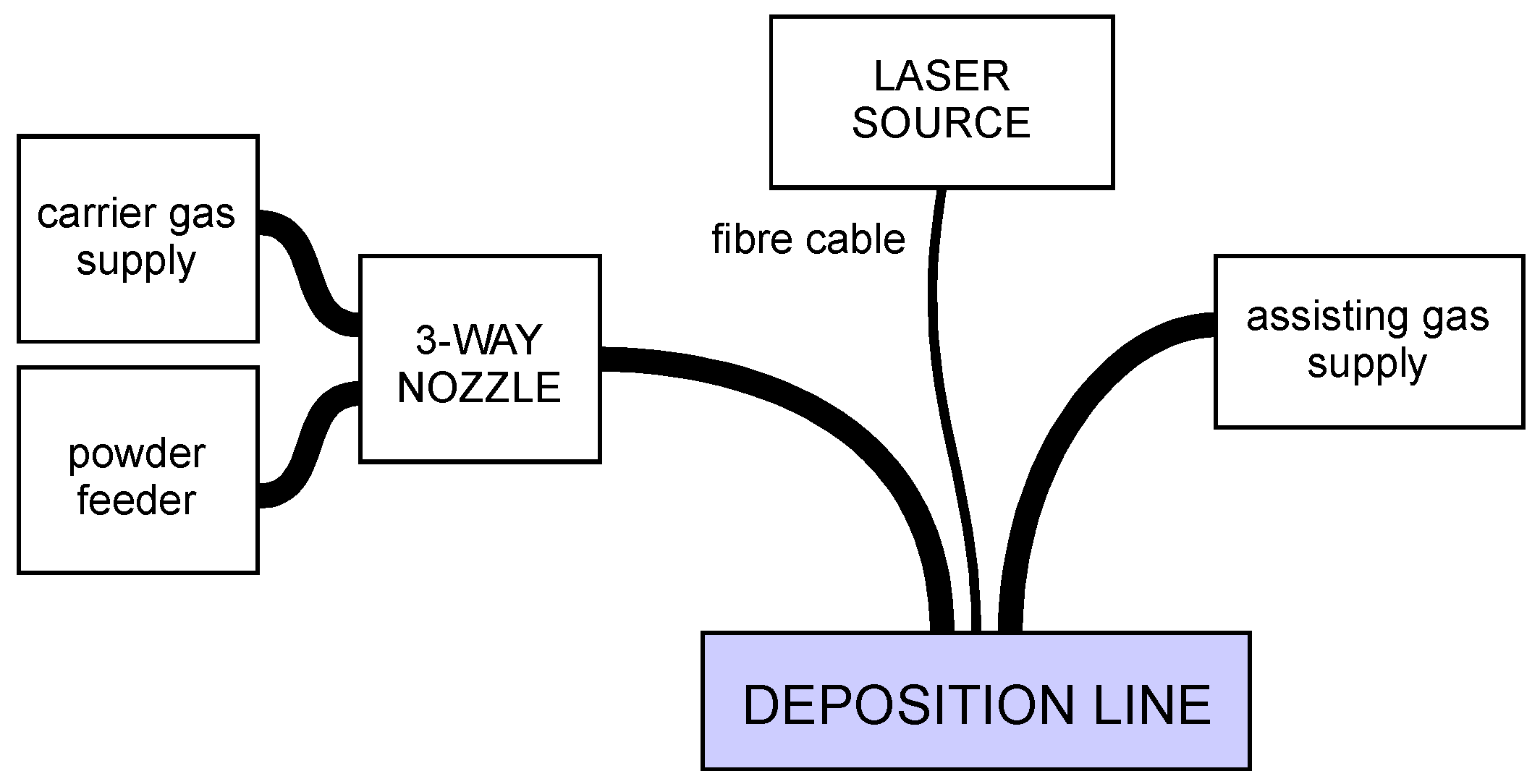

To perform DED, a deposition line (

Figure 1) is required, and a number of base components must be arranged [

25], irrespective of the form of the feedstock supply. For the purpose of this work, a fibre-delivered Yb:YAG disc laser source, operating in continuous wave emission (

Table 2), has been considered. The movement of the laser head has been accomplished by a 6-axis industrial robot with a dedicated controller, and an in-built 3-way feeding nozzle has been moved with the laser head (

Figure 2); the base metal has been provided by a powder feeder with oscillating conveyor.

Argon has been supplied: it has been injected with each stream of powder as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 3 L/min; it has been blown coaxially to the laser beam at a flow rate of 10 L/min as a shielding gas over the melting pool. A tilting angle of 4° has been set for the laser head, in agreement with common practice to process high-reflective metals [

30] to prevent back-reflections from entering the optics train. A given positive defocusing providing a processing laser beam diameter of 3 mm on the substrate has been set, thus benefiting from reduced irradiance and increased catchment of powder in the melting pool with respect to a focused condition.

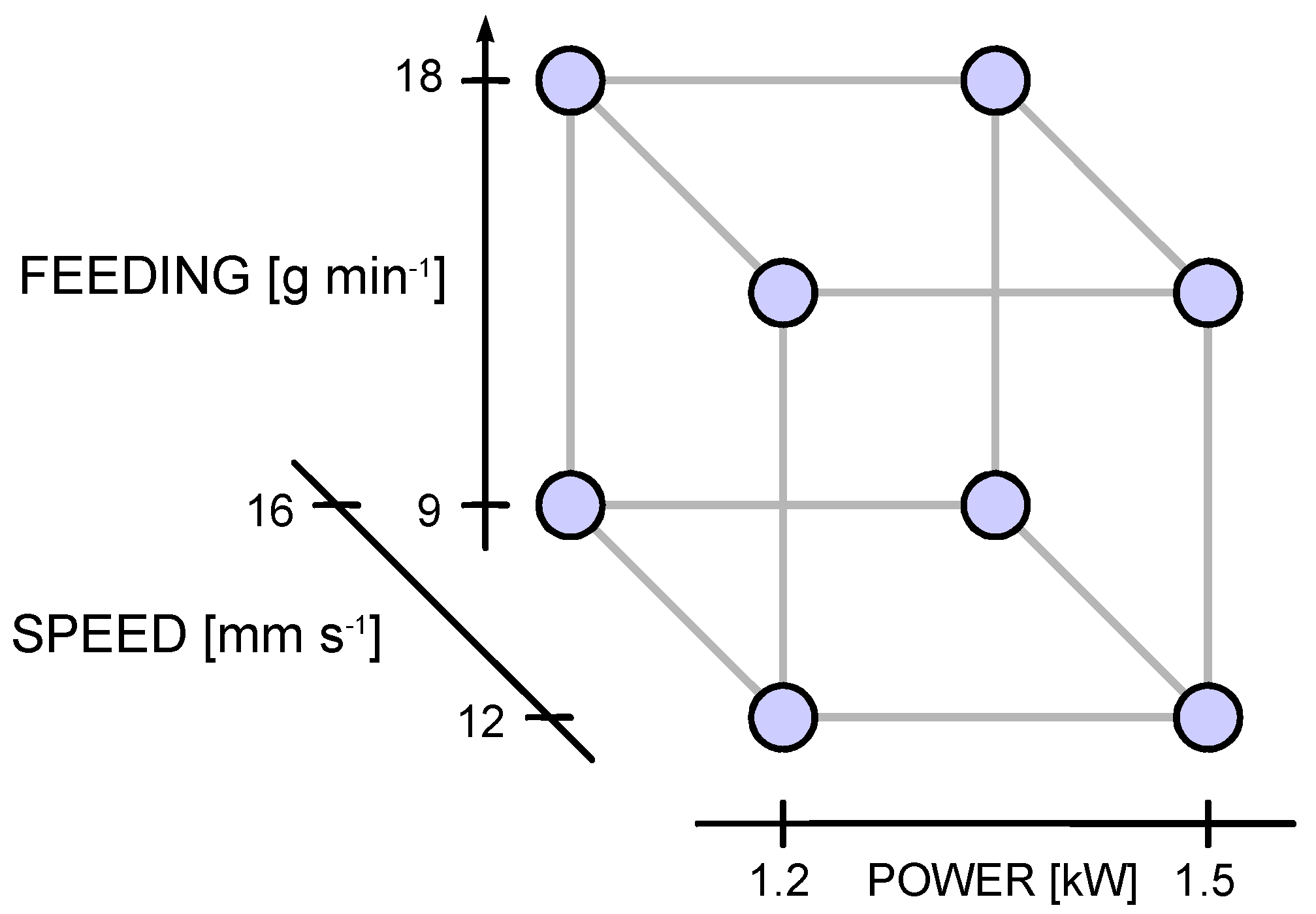

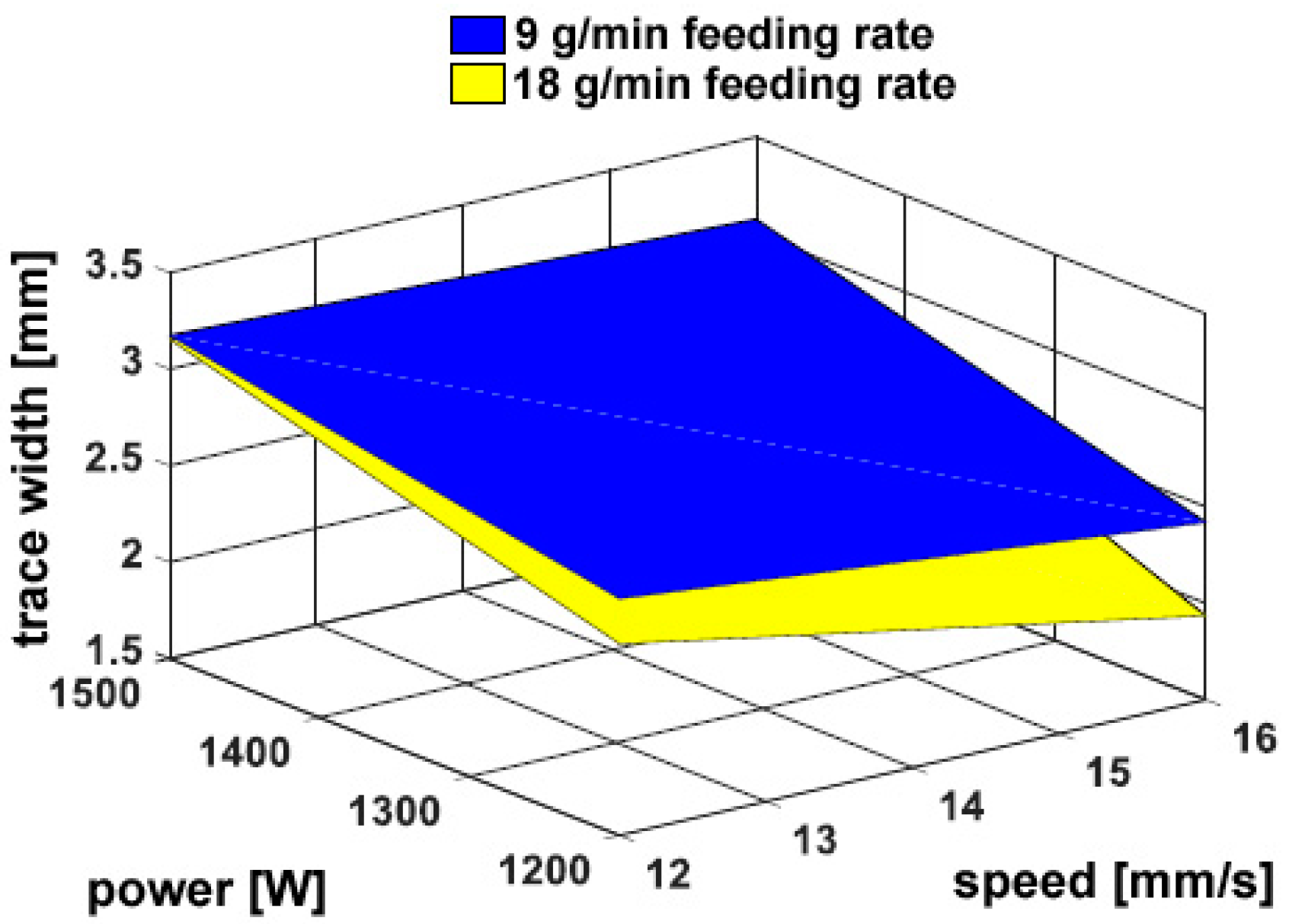

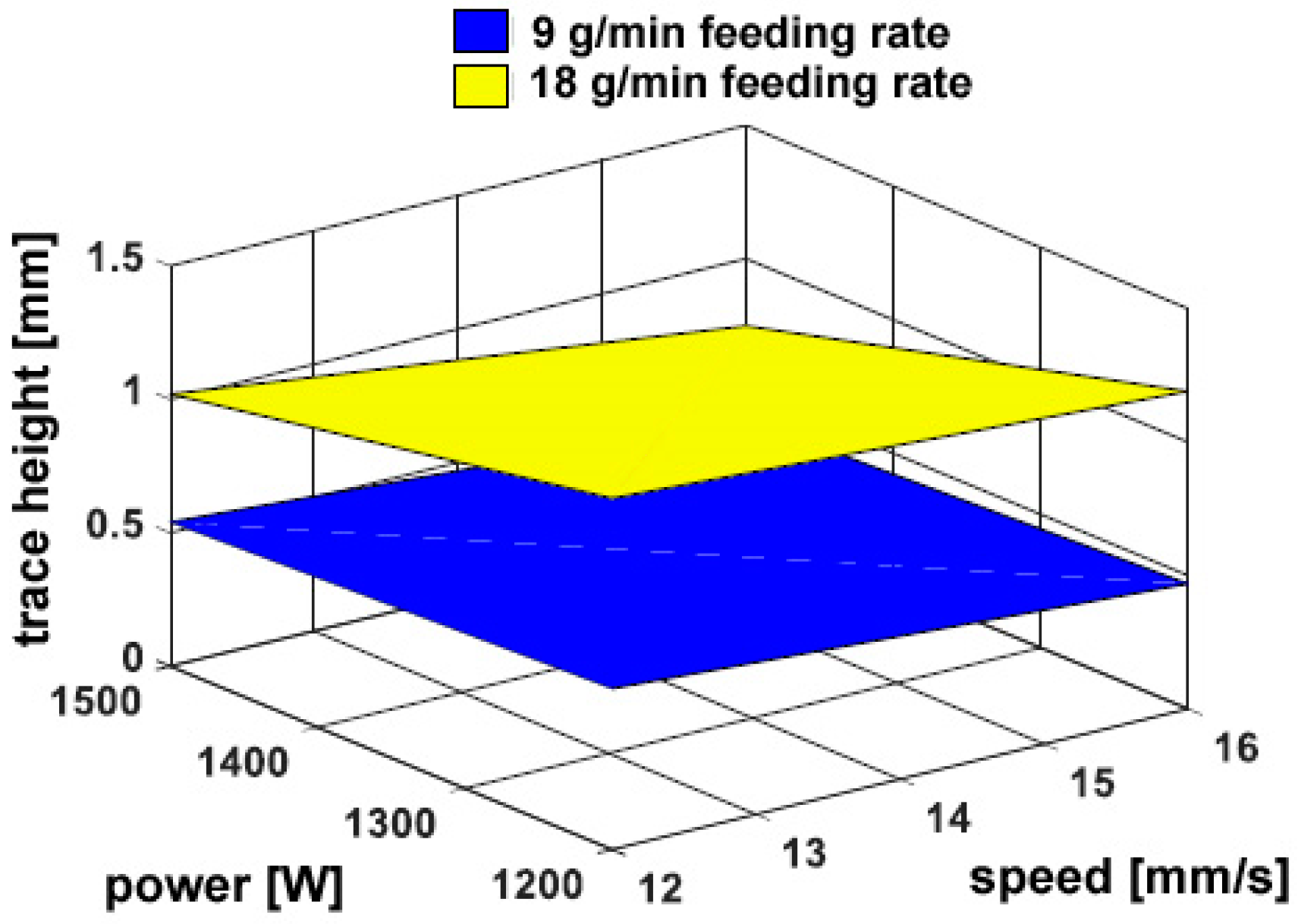

The main processing factors of the experimental plan have been selected based on the literature and past experience: namely, laser power

P, scanning speed

s and powder feeding rate

m′ have been considered. Two levels for each factor have been set upon preliminary trials and adjusted to result in valuable outcomes, preventing detachment, balling, lack of clad or excessive dilution. A full-factorial, 3-factor, 2-level experimental plan has been arranged (

Figure 3); eight deposition conditions have resulted (

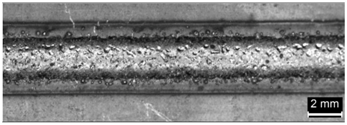

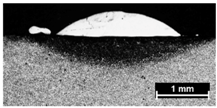

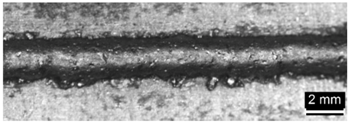

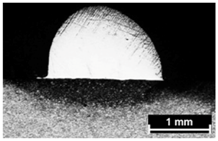

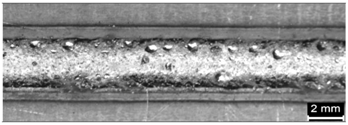

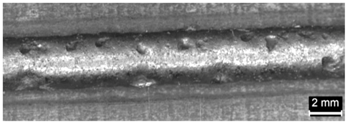

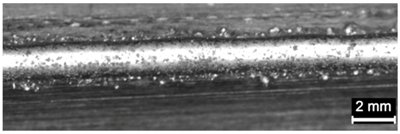

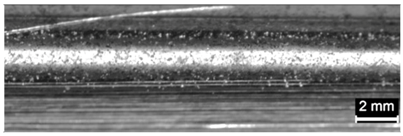

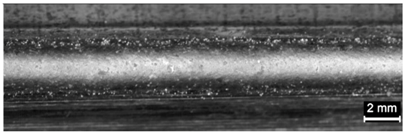

Table 3) and have been performed over both flat surfaces and edges. A total deposition length of 100 mm has been set. A 0.3 mm beveled edge has been produced by machining prior to deposition to resemble an actual condition of wear. Three runs have been planned for each processing condition in random order. The geometry has been evaluated upon cross-cutting and mechanical preparation; three samples from each trace have been considered, the results have been averaged to assess the statistical significance. Polishing to mirror finish and chemical etching with a solution consisting of 5% nitric acid and 95% ethanol at room temperature [

31] have eventually been performed.

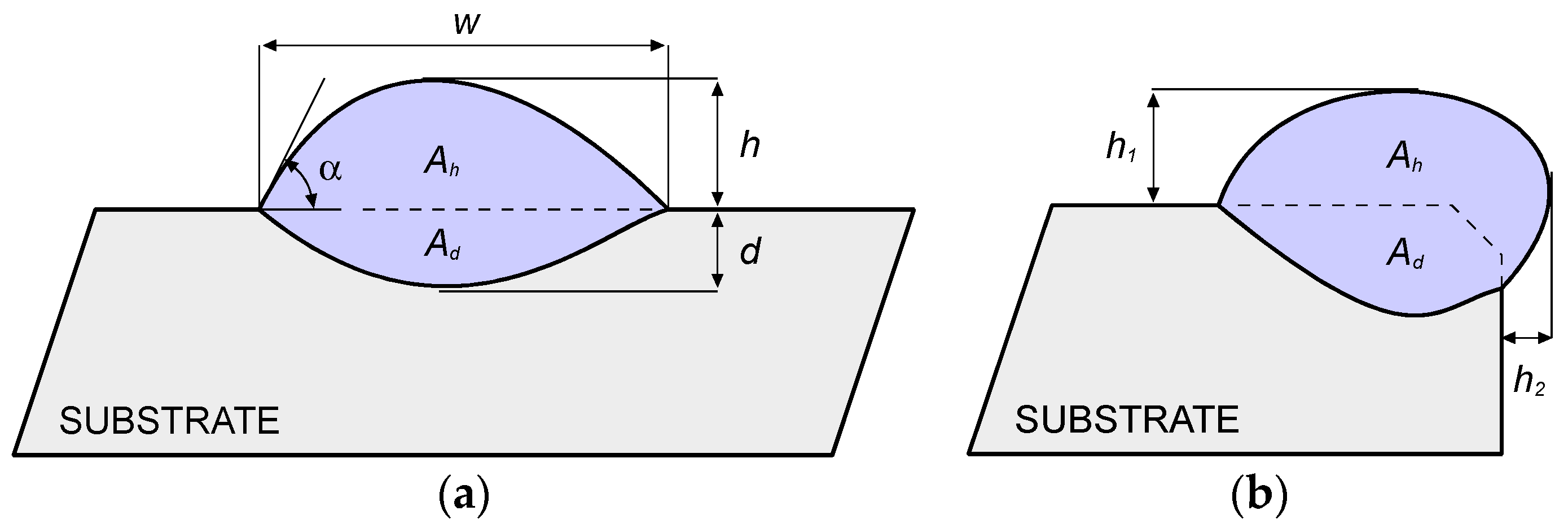

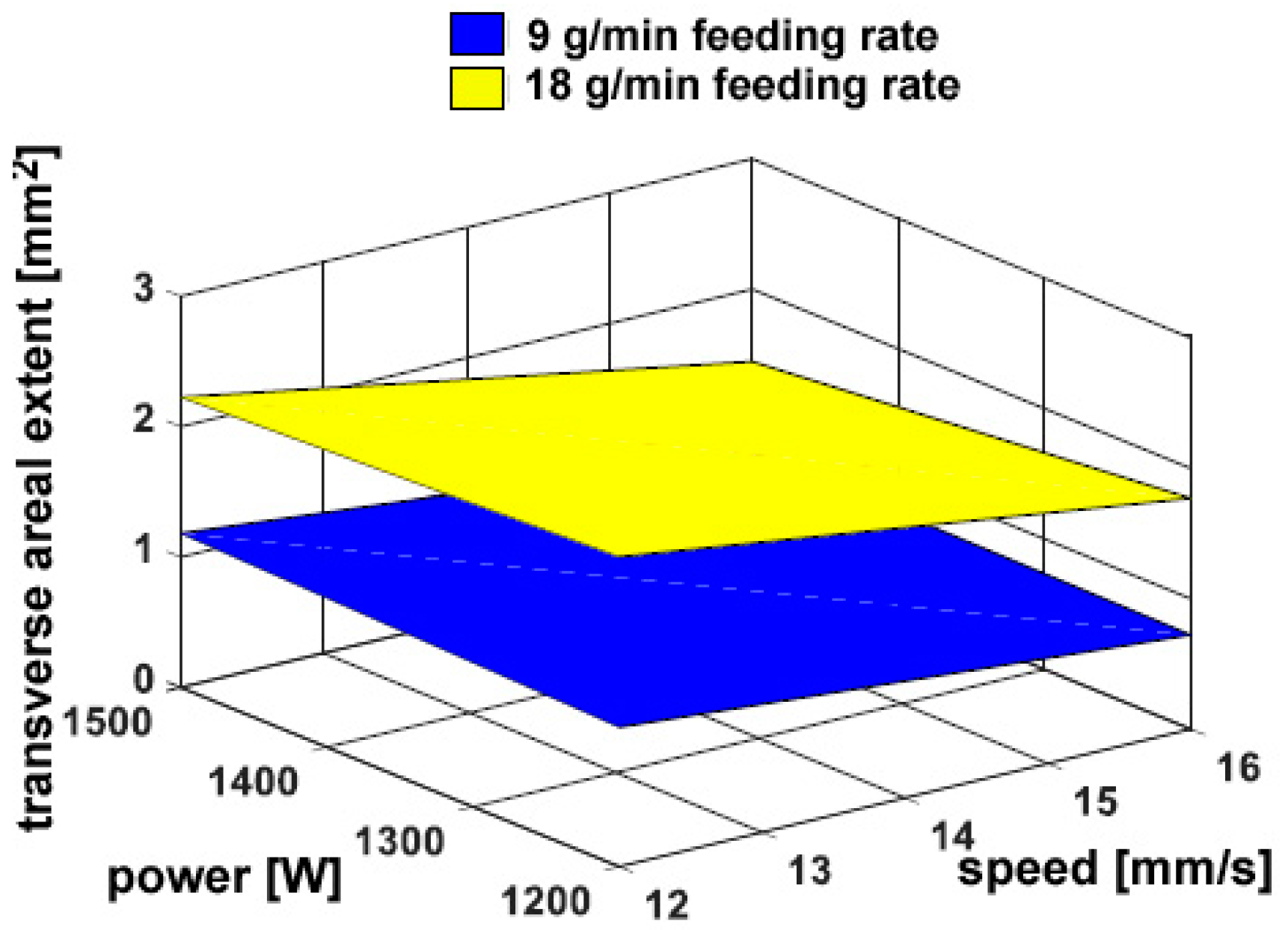

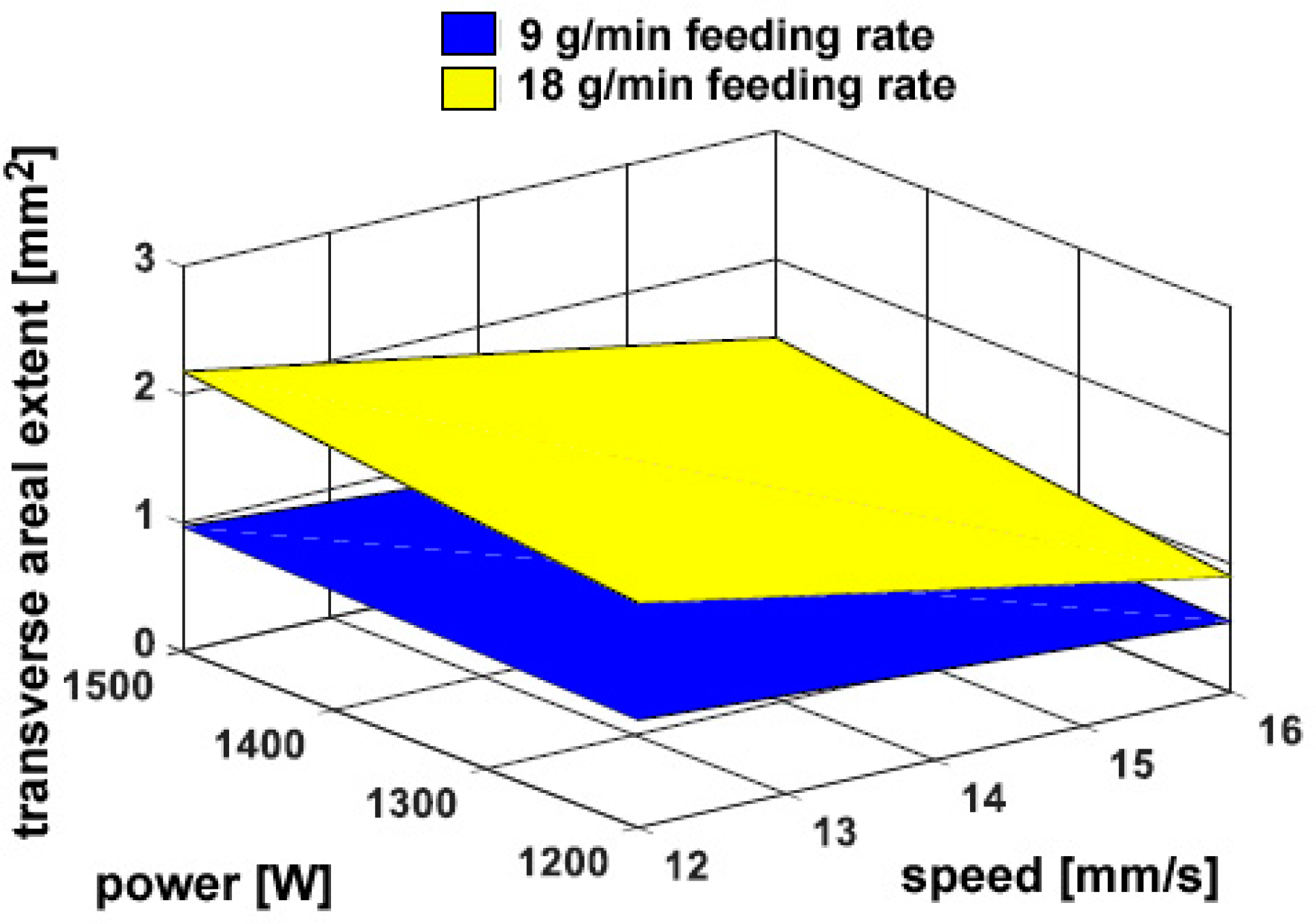

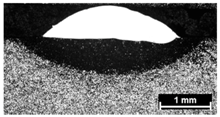

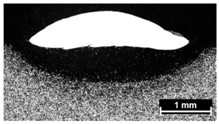

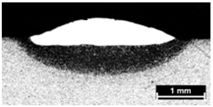

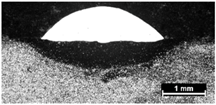

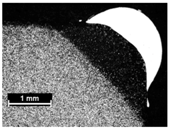

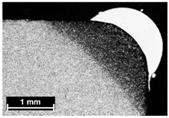

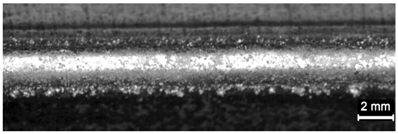

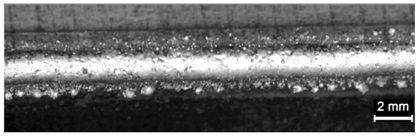

In agreement with common practice in DED, a number of geometrical responses in the cross-sections have been measured using conventional optical microscopy. Namely, in case of deposition over flat surfaces (

Figure 4a): width

w, height

h, depth

d, shape angle α at both sides of the trace, areal extent

Ah and

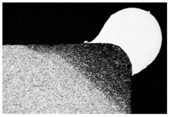

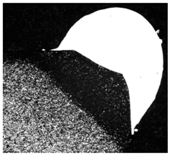

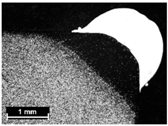

Ad of the deposition above and below the reference plane, respectively. In case of deposition over edges (

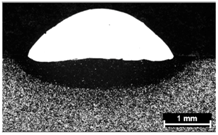

Figure 4b): height

h1 and

h2 with respect to the reference planes, areal extent

Ah and

Ad of the deposition outside and inside the theoretical edge, respectively.

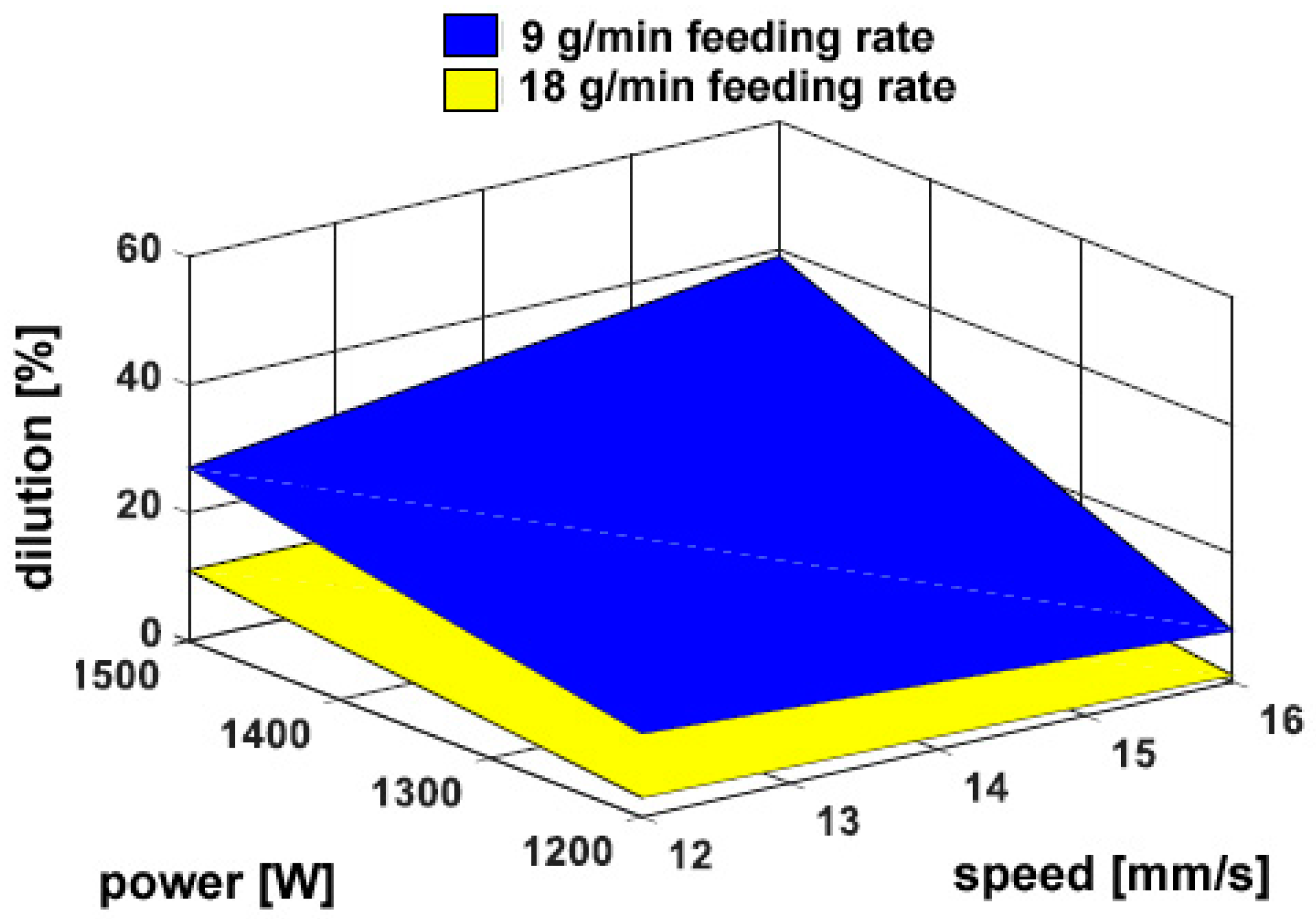

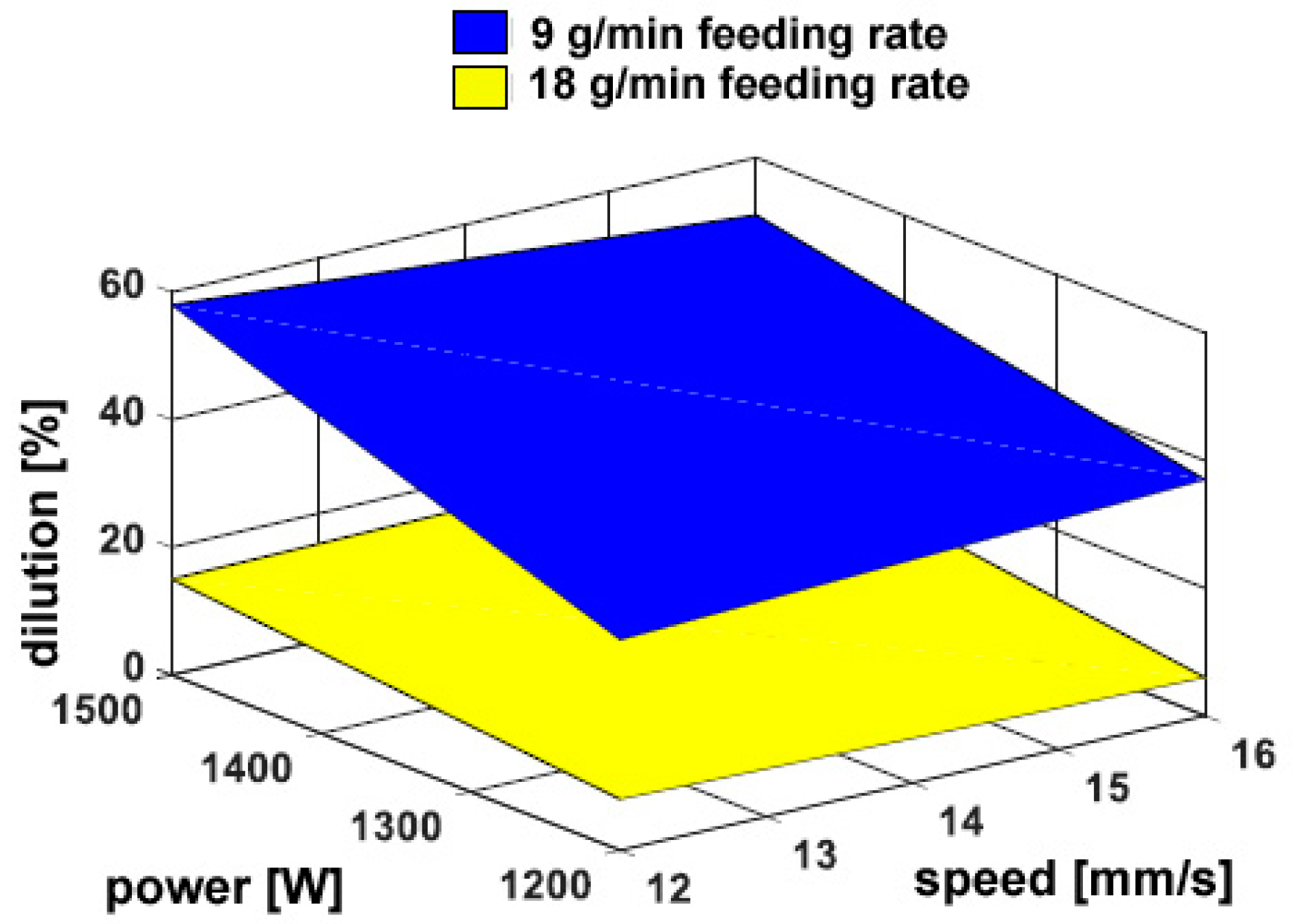

Dilution has been considered as well: Although a chemical definition is usually given involving the weight percentage composition of the main alloying elements in the substrate with respect to the reported metal [

11], it has been shown that an alternative geometric definition can be given [

32]; namely, the ratio of the fused (i.e., mixing) area of the substrate to the total area in the transverse cross-section can be measured. Therefore, dilution in this paper has been evaluated as:

Moreover, the catching efficiency η has been rated as a measure of the process effectiveness [

11]: the ratio of the deposited metal

md to the total amount of delivered powder

mt in the processing time has been evaluated. The higher this ratio, the better the efficiency, since a larger amount of powder is caught by the fused pool.

In practice, the mass of deposited metal has been found by mere weighing of the samples, whereas the total mass of delivered powder has been found based on the flow rate

m′ and the deposition time

td to provide the trace length

L:

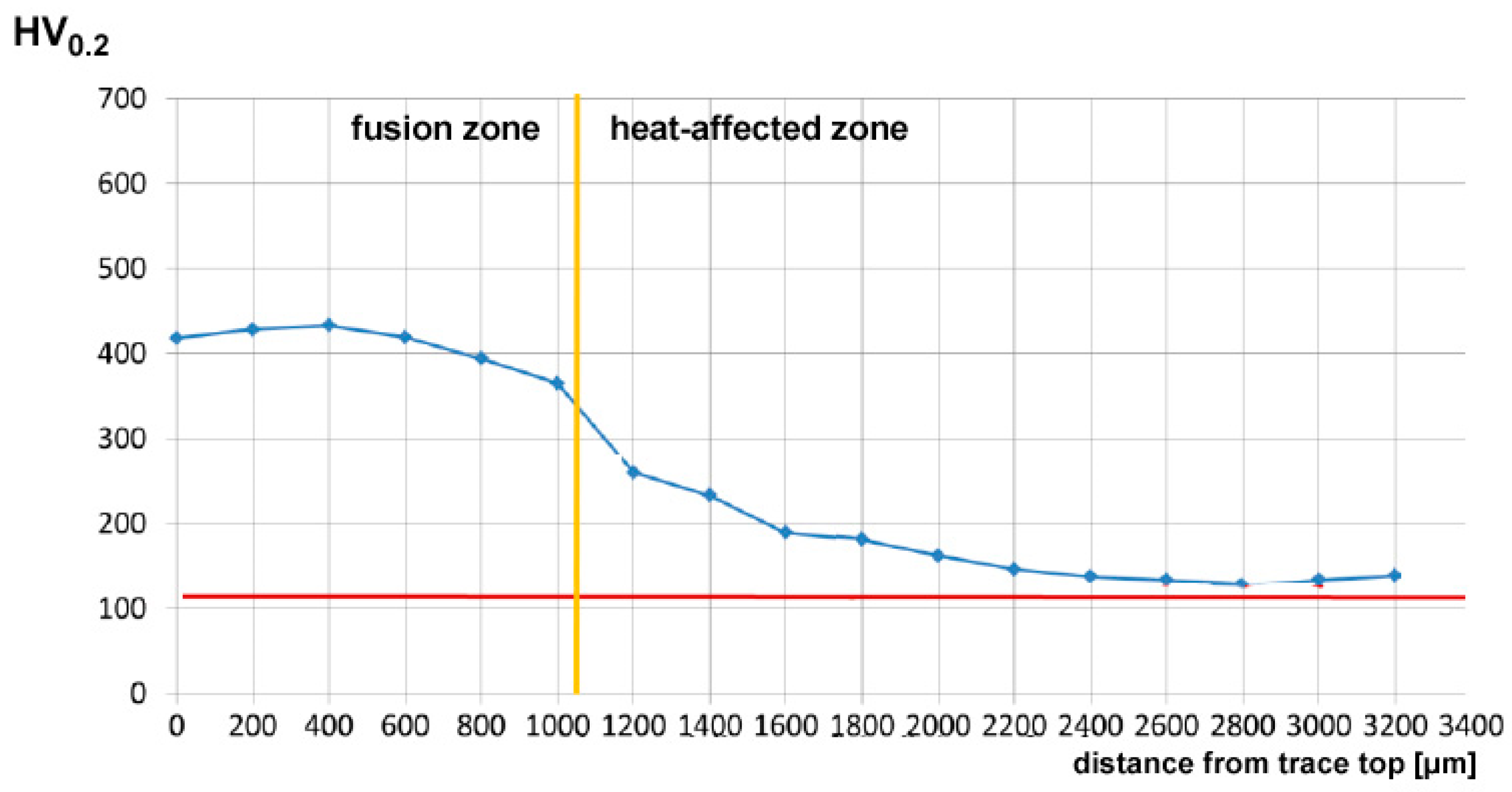

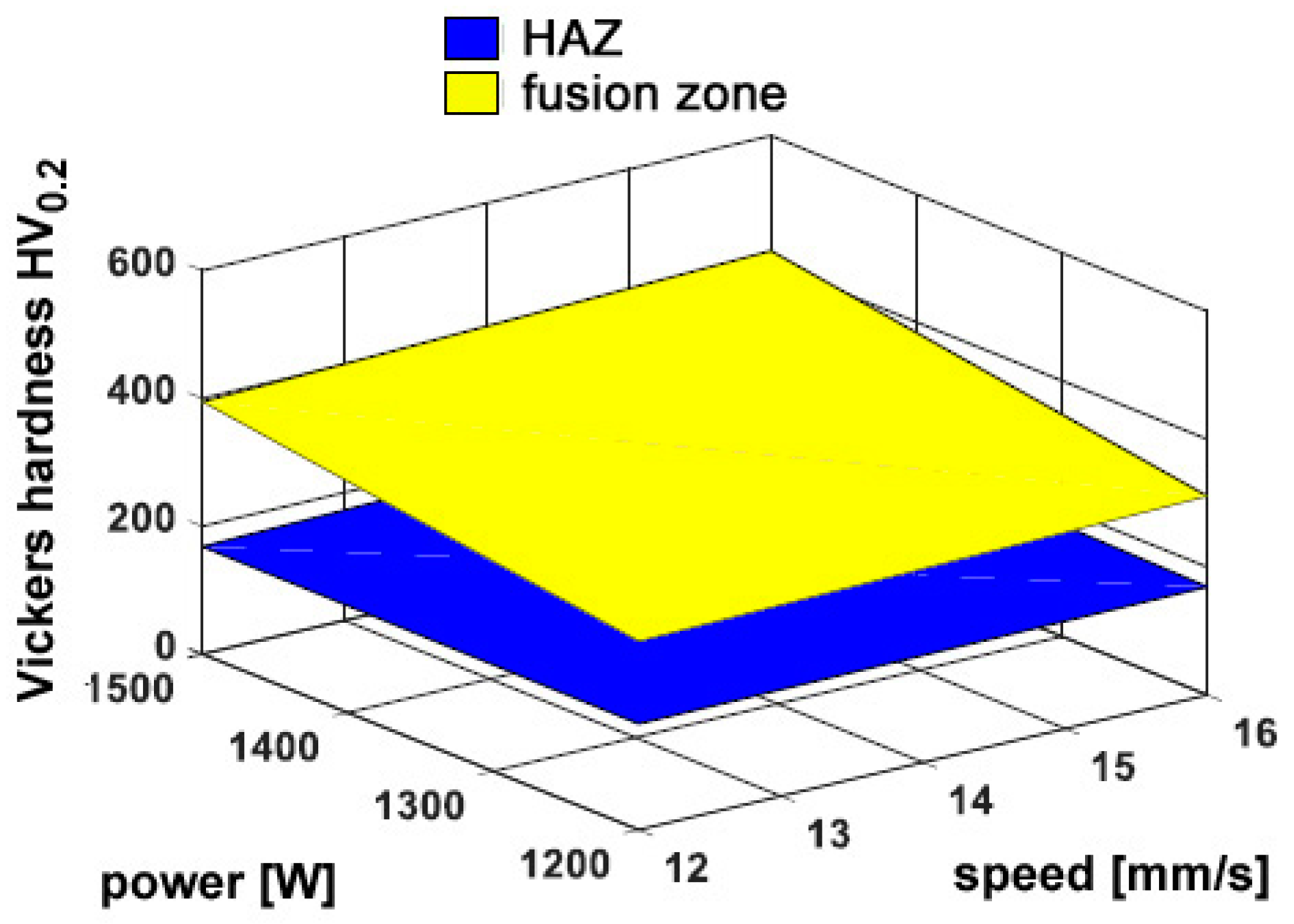

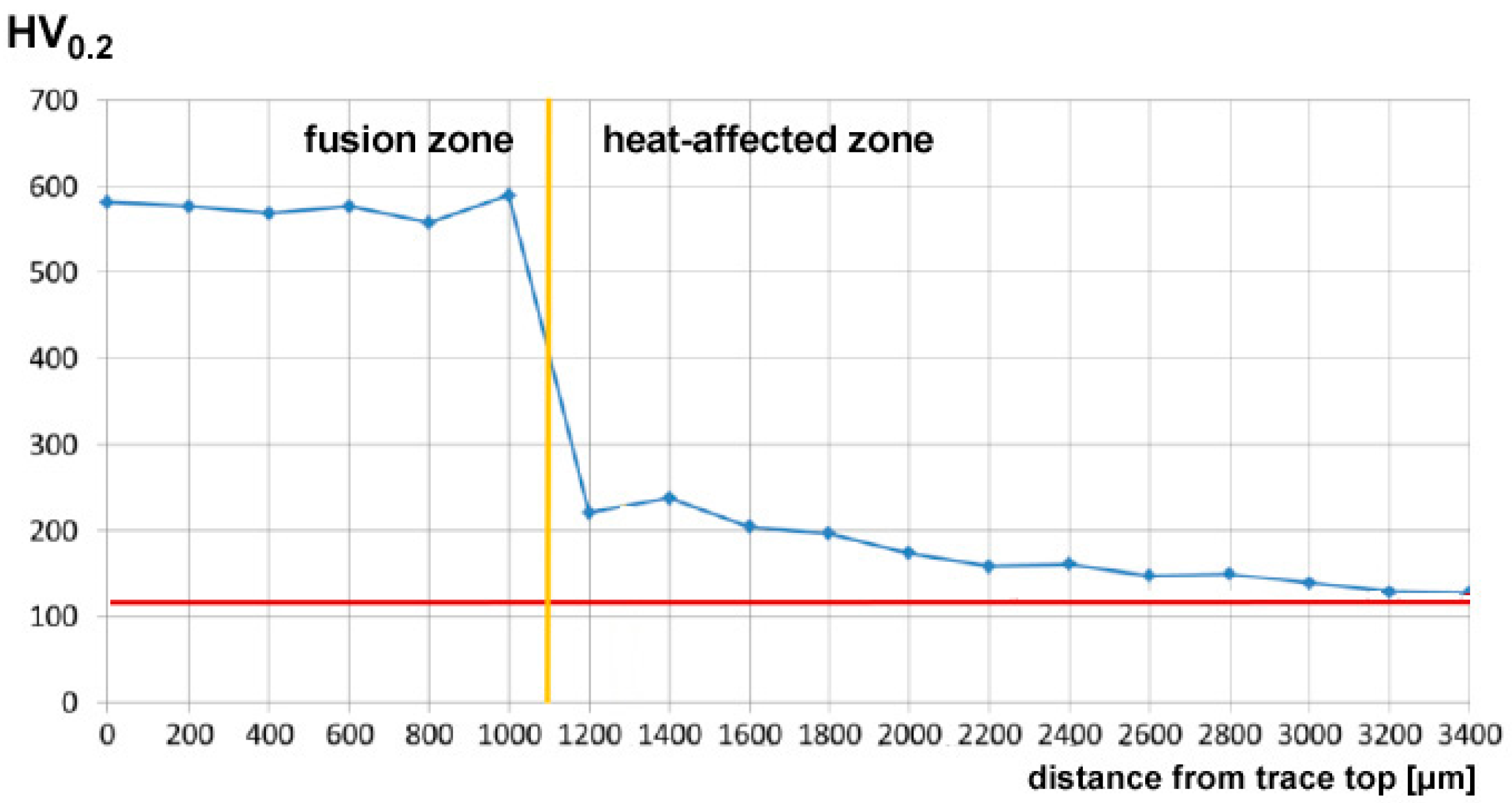

Eventually, Vickers microhardness testing has been performed to assess the extent of the HAZ between the fusion zone and base material, as well as to discuss the microstructural changes upon deposition; an indenting load of 0.2 kg has been used for a dwell period of 10 s, a step of 200 μm has been allowed between consecutive indentations, in compliance with the usual ISO standard [

33] for hardness testing of metallic materials.

4. Conclusions

The effectiveness of the process of Directed Energy Deposition has been addressed over both flat surfaces and edges, aimed at real applications where coating or overhauling for the purpose of restoring the nominal dimensions is required. Convincing findings have been achieved.

Namely, a proper processing window has been found to perform the process over UNS S43100 chromium-nickel stainless steel. Based on the application, the proper condition must be selected in a multi-constraint optimization approach. Nevertheless, a number of main findings can be given here:

the approximation of a parabolic profile in the cross-section is suitable in case of flat deposition; hence, a simple description is benefited when setting a proper deposition strategy for overlapping, multi-layer traces at the pre-processing stage;

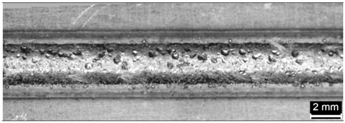

no cracks or pores are produced in random cross-sections of the samples in the suggested processing window;

the catching efficiency depends on the processing parameters; half the amount of the total delivered powder is effectively deposited on average for both flat and edge depositions;

dilution, hence the affection of the parent metal, is mainly governed by the thermal input and is increased when moving from flat to edge deposition as a consequence of modified thermal exchange.

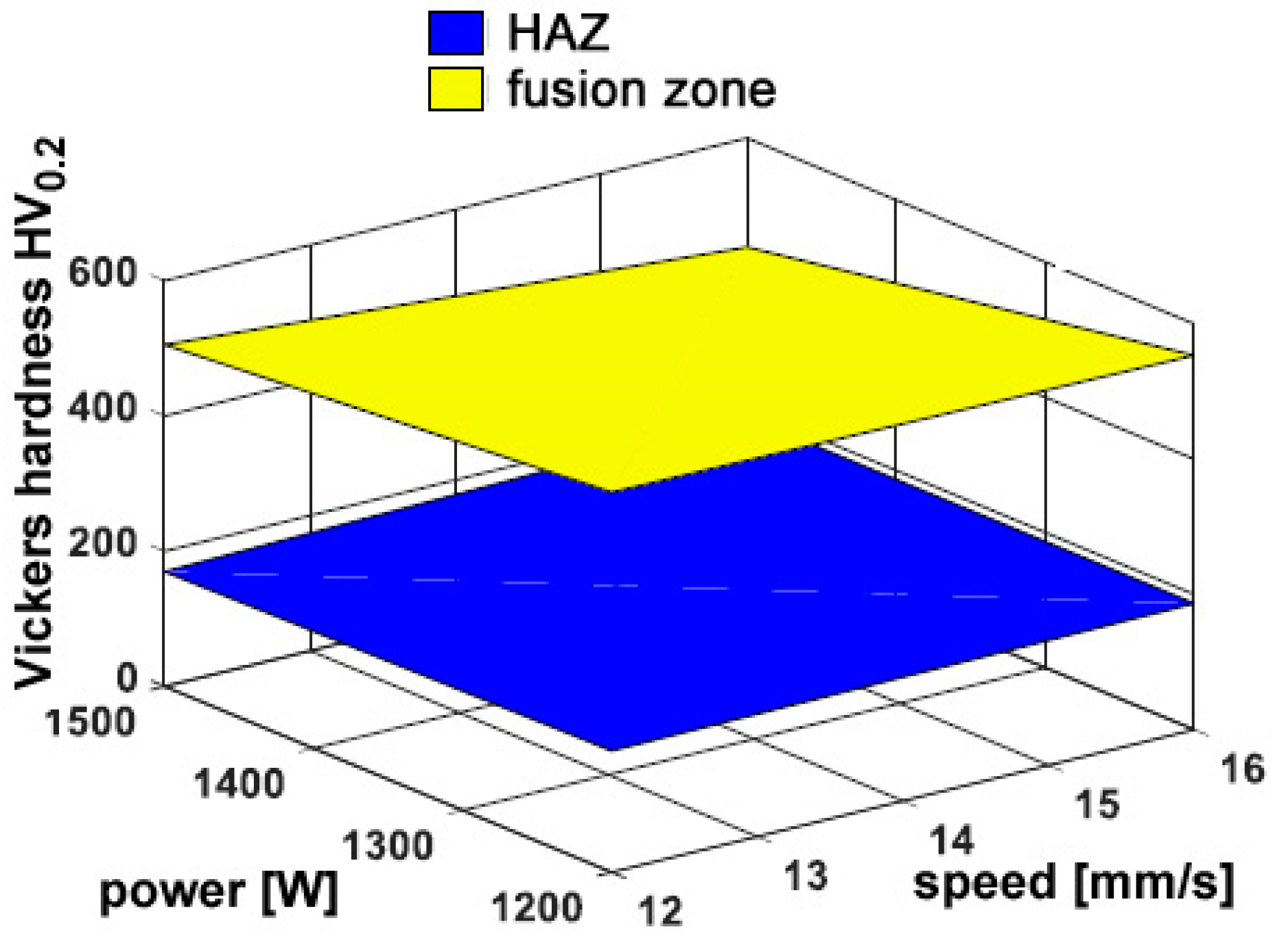

Tensile and fatigue strengths are expected to depend on the processing condition of deposition. Dependence of the Vickers microhardness on the thermal input has been found.