Reassessing the International Competitiveness and Economic Sustainability of China’s Solar PV Industry: A Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis

Abstract

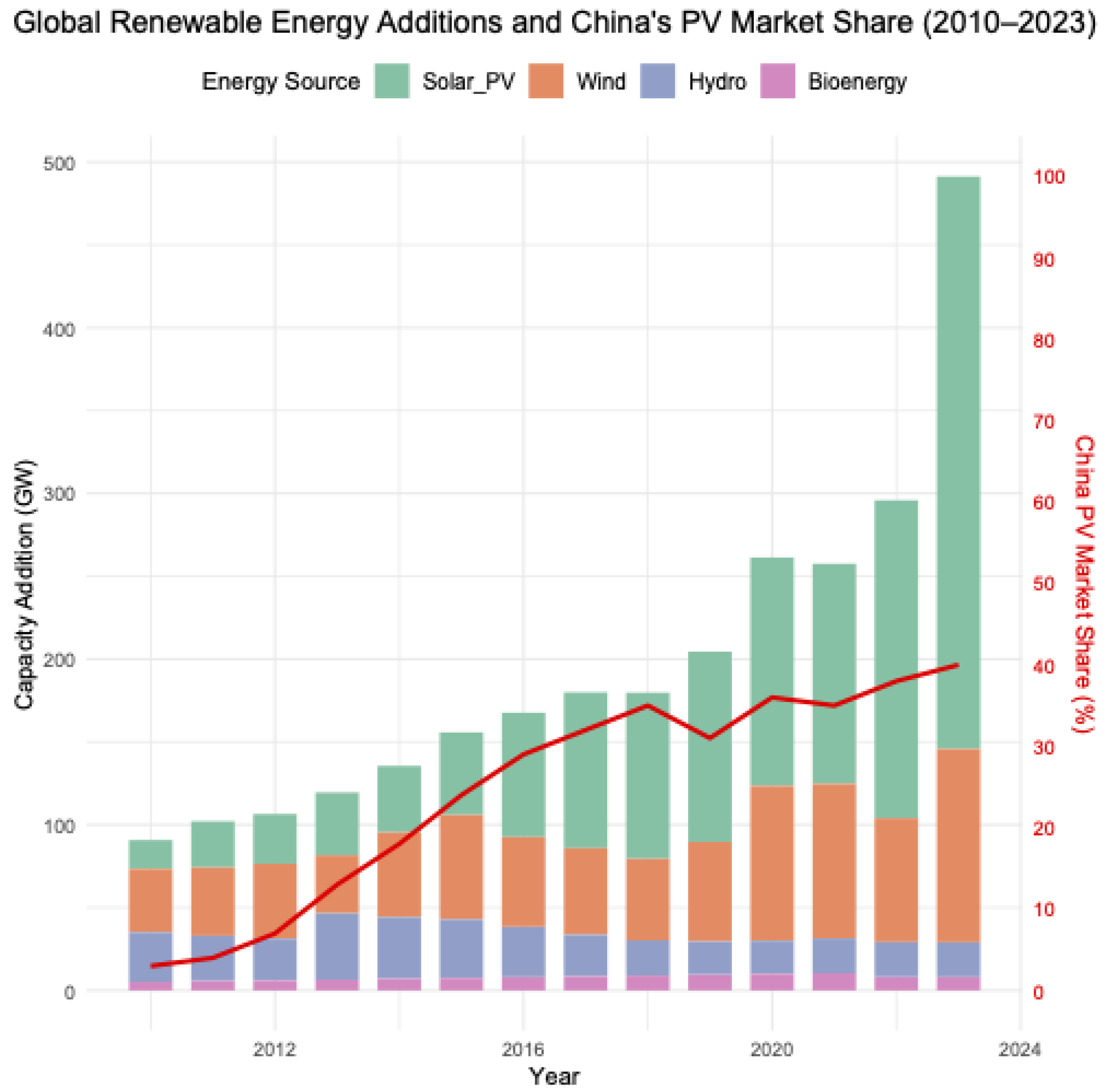

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

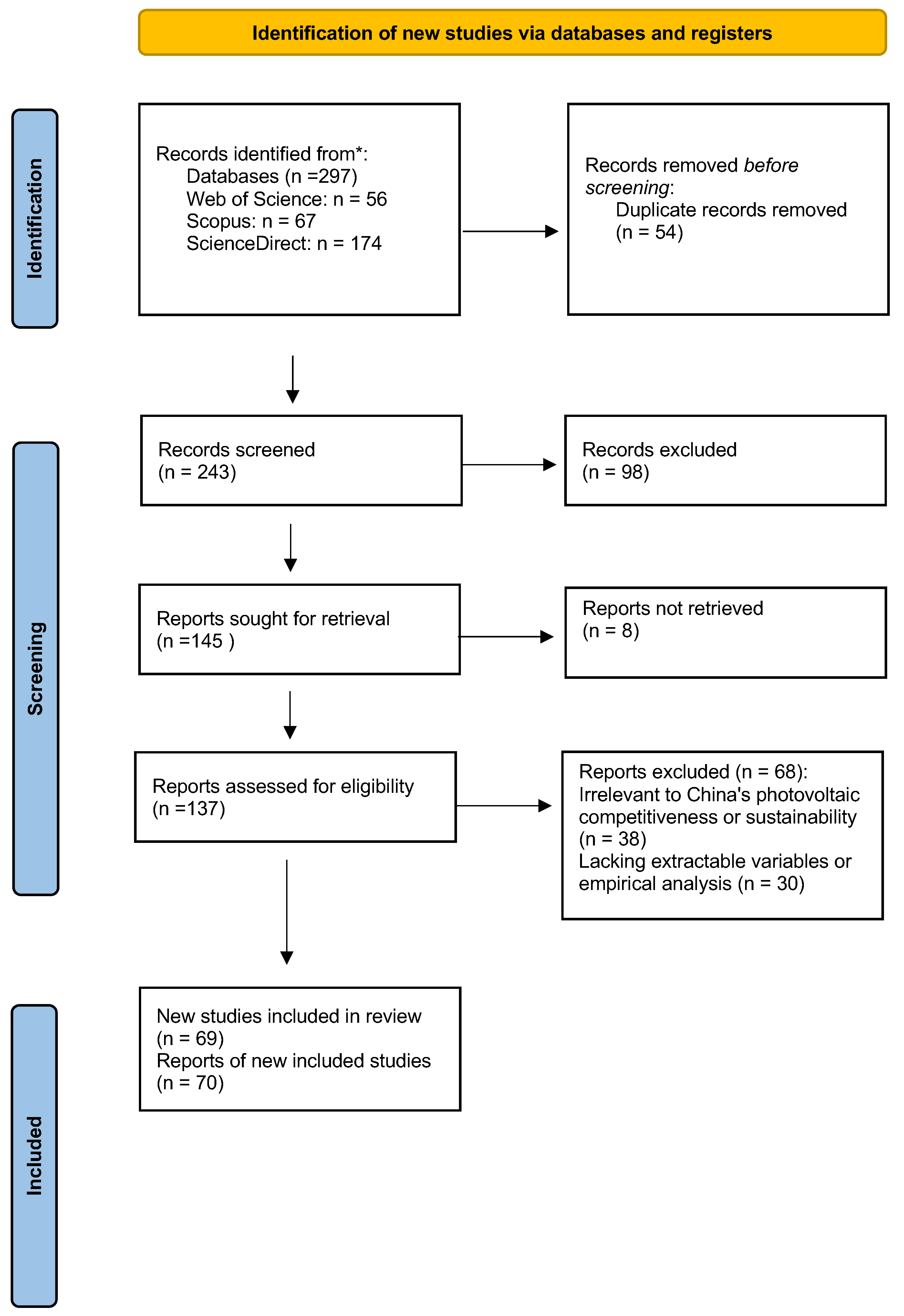

2.1. Literature Search and Screening Process

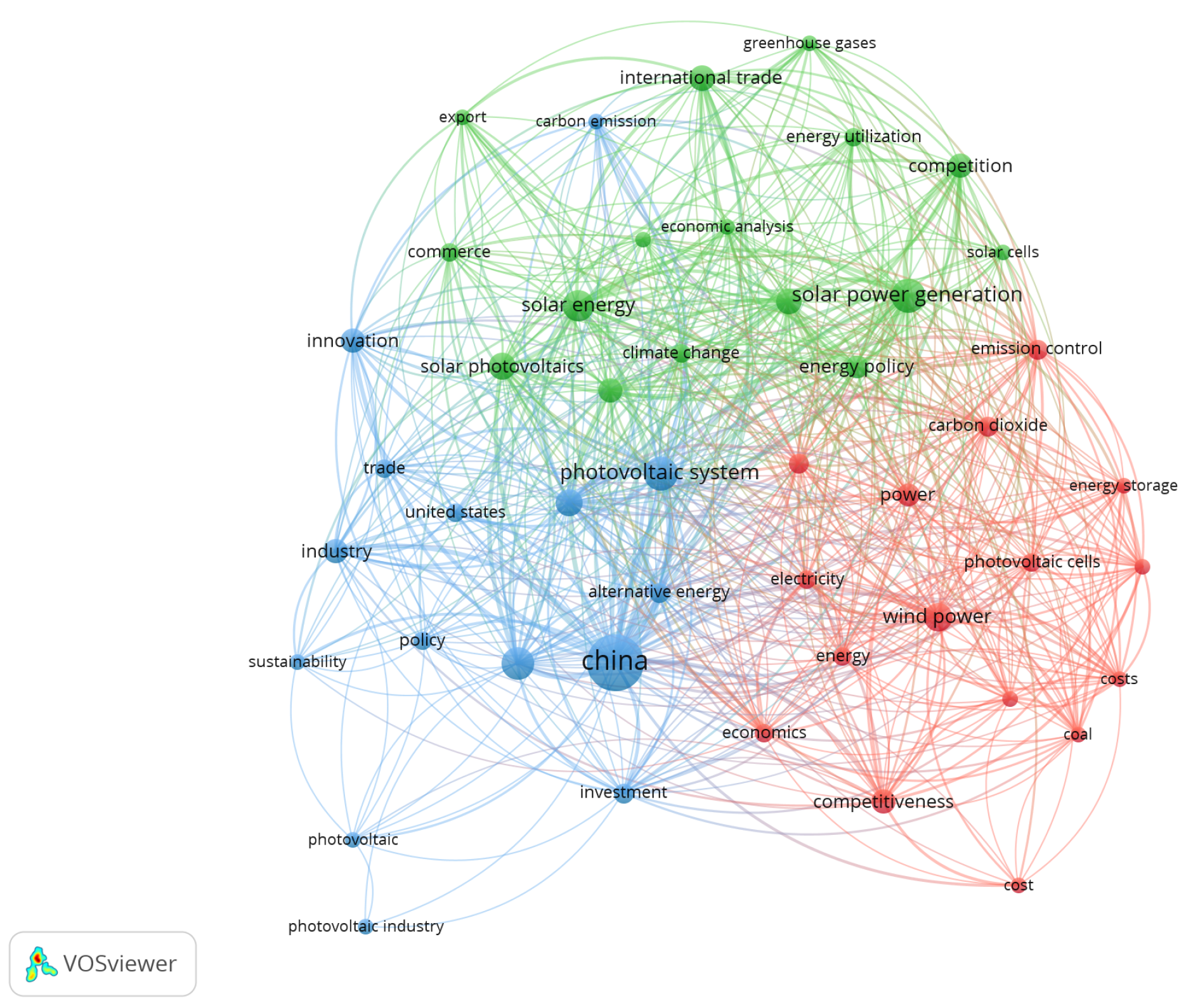

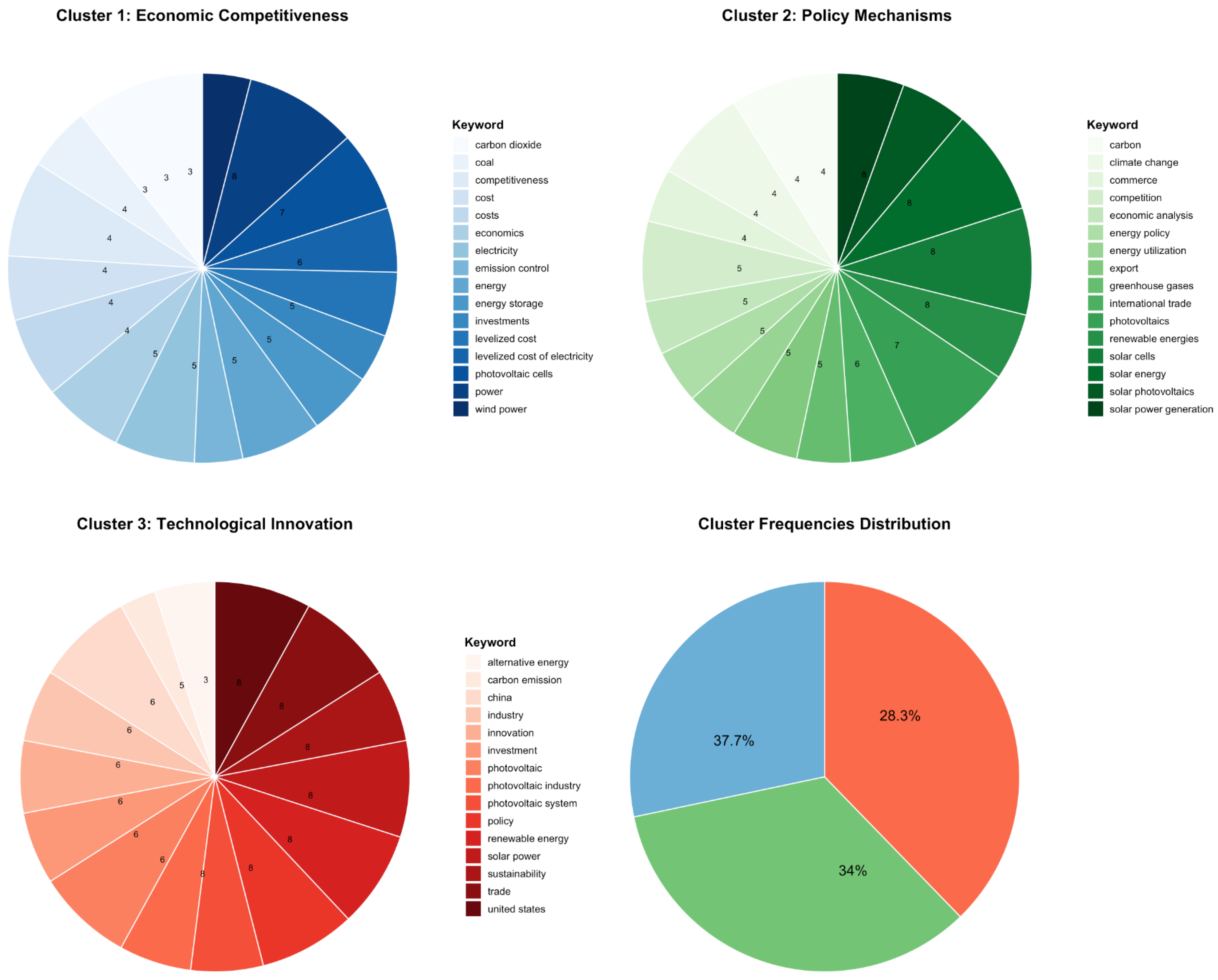

2.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis and Thematic Clustering

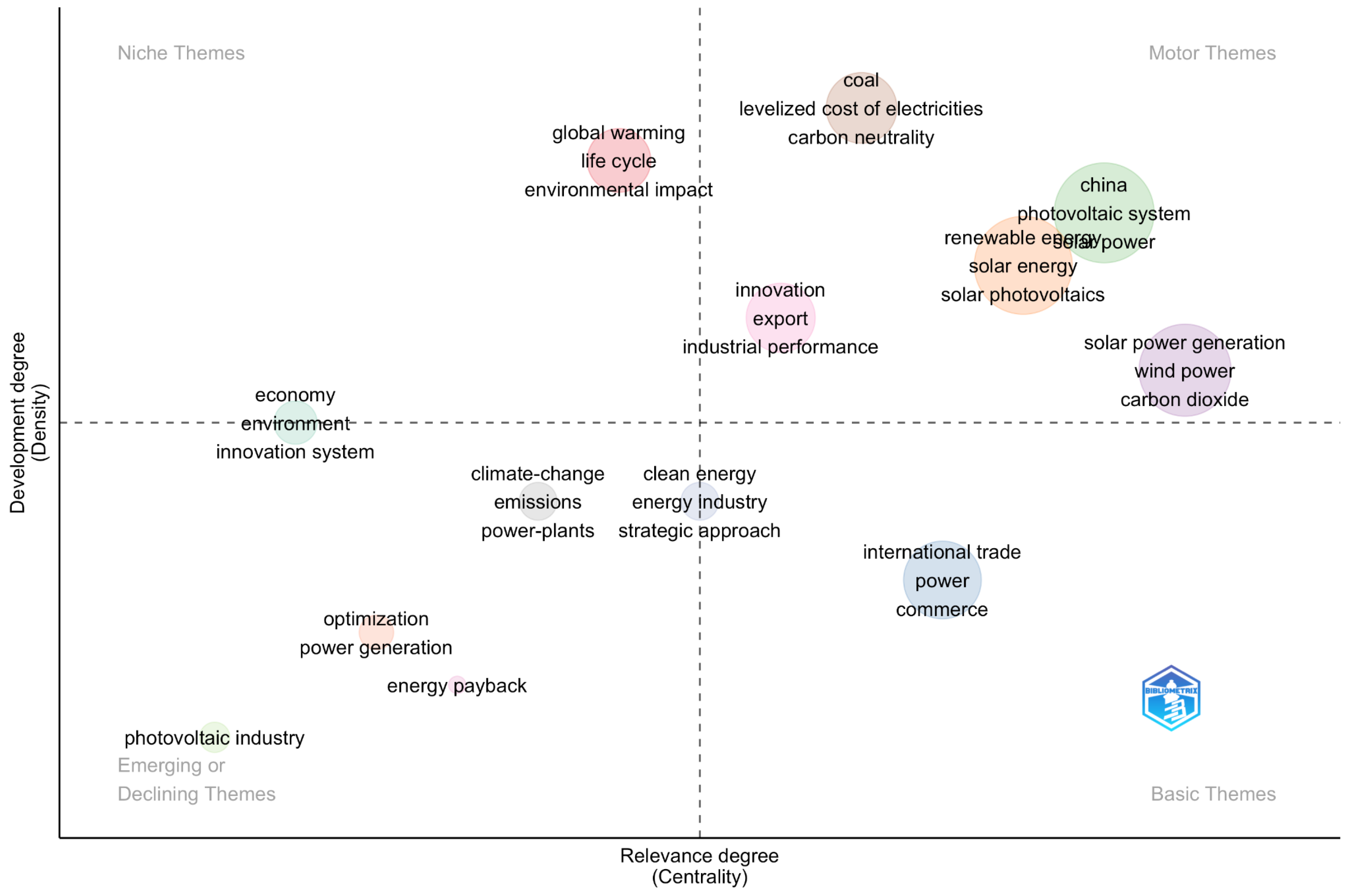

2.3. Thematic Maturity and Evolutionary Trends

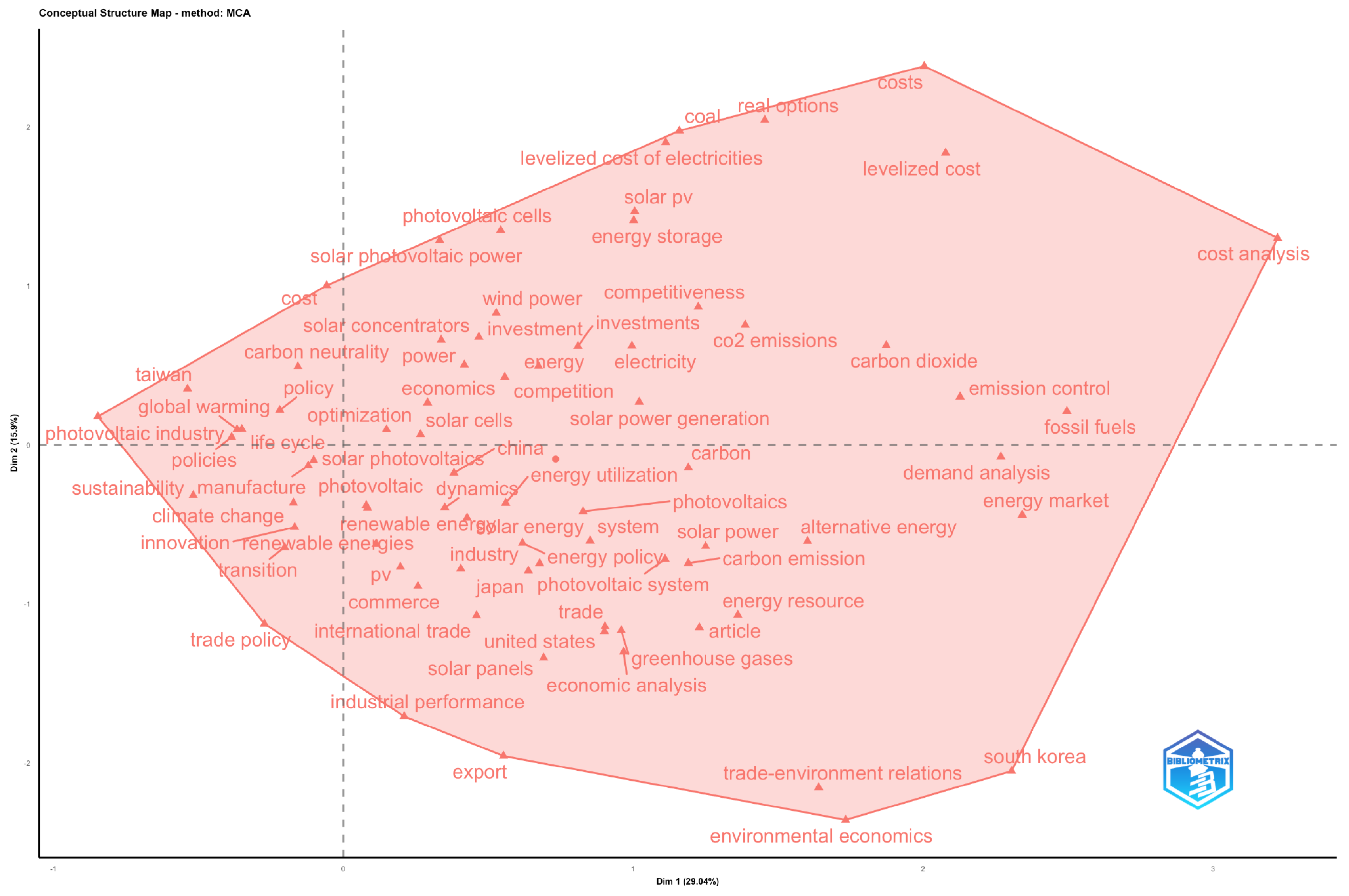

2.4. Conceptual Framework and Semantic Dimensions

2.5. Data Extraction and Coding Strategy

Quality Appraisal and Evidence Weighting

3. Thematic Synthesis and Mechanism Analysis

3.1. Research Topic Structure and Keyword Cluster Analysis

3.2. Topic Maturity and Evolutionary Trends

3.3. Conceptual Structure and Semantic Dimensions

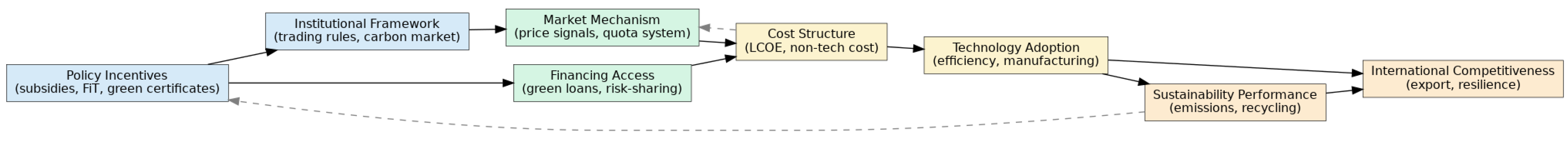

3.4. Mechanism Structure and Variable Analysis

3.4.1. Policy Mechanism Evolution

3.4.2. Economic Feasibility and Cost Structure

3.4.3. Technology and Environmental Sustainability

3.4.4. Market Coordination and Institutional Adaptation

3.4.5. Synergy Mechanisms of Competitiveness and Sustainability

4. Critical Discussion and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2023; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Energy Statistics 2023; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Liu, Y. Global carbon neutrality and China’s contribution: The impact of international carbon market policies on China’s photovoltaic product exports. Energy Policy 2024, 193, 114299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEA. National Energy Administration Statistical Bulletin; National Education Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IEA PVPS. Energy Investment and Transition Outlook; Technical Report; Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis: Lakewood, OH, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, K.; Fang, Y. A Gravity Model Analysis of China’s Trade in Renewable Energy Goods With ASEAN Countries as Well as Japan and South Korea. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 953005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. The impact of green trade barriers on China’s photovoltaic products exports to ASEAN. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1459950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Trade Organization. World Trade Report 2023: Re-Globalization for a Secure, Inclusive and Sustainable Future; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/wtr23_e/wtr23_e.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, M.; Akbar, S. Contribution of international photovoltaic trade to global greenhouse gas emission reduction: The example of China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, M.; Giunta, A.; Ruberto, S.; Scalera, D. Global value chains and energy-related sustainable practices. Evidence from Enterprise Survey data. Energy Econ. 2023, 127, 107068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xie, Z. International trade barriers, export and industrial resilience: An empirical study based on the EU and USA antidumping and countervailing policies on photovoltaic products. Energy Policy 2025, 201, 114556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, S.; Santibañez-Aguilar, J.E.; Shapiro, B.B.; Powell, D.M.; Peters, I.M.; Buonassisi, T.; Kammen, D.M.; Flores-Tlacuahuac, A. Sustainable silicon photovoltaics manufacturing in a global market: A techno-economic, tariff and transportation framework. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martulli, A.; Gota, F.; Rajagopalan, N.; Meyer, T.; Quiroz, C.; Costa, D.; Paetzold, U.; Malina, R.; Vermang, B.; Lizin, S. Beyond silicon: Thin-film tandem as an opportunity for photovoltaics supply chain diversification and faster power system decarbonization out to 2050. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 279, 113212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Li, S.; Xiong, B.; Liu, H.; Ma, F. Revolution and significance of “Green Energy Transition” in the context of new quality productive forces: A discussion on theoretical understanding of “Energy Triangle”. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1611–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Du, D.; Duan, D.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, Q. A network analysis of global competition in photovoltaic technologies: Evidence from patent data. Appl. Energy 2024, 375, 124010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; He, X.; Qin, Y.; Chen, L.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. Assessing China’s solar power potential: Uncertainty quantification and economic analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, T.; Huo, M.; Neuhoff, K. Survey of photovoltaic industry and policy in Germany and China. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, N.; Laurent, A.; Krebs, F. Ecodesign of organic photovoltaic modules from Danish and Chinese perspectives. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2537–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liao, B.; Yang, S.; Pardalos, P.M. Evolutionary game analysis on government subsidy policy and bank loan strategy in China’s distributed photovoltaic market. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2022, 90, 753–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Du, H.; Ren, J.; Sovacool, B.K.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, G. Market dynamics, innovation, and transition in China’s solar photovoltaic (PV) industry: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, R. Structural Holes and Good Ideas. Am. J. Sociol. 2004, 110, 349–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.; López-Herrera, A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory field. J. Inf. 2011, 5, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Sun, H.; Koh, L. Global solar photovoltaic industry: An overview and national competitiveness of Taiwan. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ge, Z. An Appraisal on China’s Feed-In Tariff Policies for PV and Wind Power: Implementation Effects and Optimization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wei, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhong, P.; Zhang, X. Comparison of the LCOE between coal-fired power plants with CCS and main low-carbon generation technologies: Evidence from China. Energy 2019, 176, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubbak, M. The technological system of production and innovation: The case of photovoltaic technology in China. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 993–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Ding, N. Life-cycle assessment of China’s multi-crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules considering international trade. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 94, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Ahmad, F.; Abid, N.; Khan, I. The impact of digital inclusive finance on the growth of the renewable energy industry: Theoretical and logical Chinese experience. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, F.; Geall, S.; Wang, Y. Solar PV and solar water heaters in China: Different pathways to low carbon energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Turner, W.A.; Bauin, S. From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1983, 22, 191–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Andrews-Speed, P.; He, Y. The development trajectories of wind power and solar PV power in China: A comparison and policy recommendations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.S.; Hsiao, C.T.; Chang, D.S.; Hsiao, C.H. How the European Union’s and the United States’ anti-dumping duties affect Taiwan’s PV industry: A policy simulation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, C.; Anadon, L.D. Unrelated diversification in latecomer contexts: Emergence of the Chinese solar photovoltaics industry. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2018, 28, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, S.; Nielsen, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Song, F.; Wei, C.; et al. Combined solar power and storage as cost-competitive and grid-compatible supply for China’s future carbon-neutral electricity system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2103471118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Yang, Y.; Elia Campana, P.; He, J. City-level analysis of subsidy-free solar photovoltaic electricity price, profits and grid parity in China. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.; Castán Broto, V. Co-benefits, contradictions, and multi-level governance of low-carbon experimentation: Leveraging solar energy for sustainable development in China. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 59, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Mou, S.; Wei, S.; Qiu, L.; Hu, H.; Zhou, H. Research on the evolution of China’s photovoltaic technology innovation network from the perspective of patents. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 51, 101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Mo, J.; Betz, R.; Cui, L.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y. Achieving grid parity of solar PV power in China- The role of Tradable Green Certificate. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hua, H.; Zhang, J. The impact of phasing out subsidy for financial performance of photovoltaic enterprises: Evidence from “531 new policy” on China’s photovoltaic industry. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1486351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, A.L.; Sovacool, B.K.; Bambawale, M.J. And then what happened? A retrospective appraisal of China’s Renewable Energy Development Project (REDP). Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 3154–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voituriez, T.; Wang, X. Real challenges behind the EU-China PV trade dispute settlement. Clim. Policy 2015, 15, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïd, R.; Bahlali, M.; Creti, A. Green innovation downturn: The role of imperfect competition. Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.; Lewis, J.; Zhang, X. A green expansion: China’s role in the global deployment and transfer of solar photovoltaic technology. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 60, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Lin, B. The impact of removing cross subsidies in electric power industry in China: Welfare, economy, and CO2 emission. Energy Policy 2021, 148, 111994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chai, Q.; Zhang, X.; He, J.; Yue, L.; Dong, X.; Wu, S. Economical assessment of large-scale photovoltaic power development in China. Energy 2012, 40, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Marino, M.; Reinoso, J.; Paggi, M. A continuum large-deformation theory for the coupled modeling of polymer–solvent system with application to PV recycling. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2023, 187, 103842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Chen, X.; Luo, X.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Z.; Lai, W.; Xu, Y.; Lu, C. Analysis of the impact of China’s energy industry on social development from the perspective of low-carbon policy. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, H.; Yu, X.; Wang, L. Economic evaluation of grid-connected micro-grid system with photovoltaic and energy storage under different investment and financing models. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhi, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Su, J. China’s solar photovoltaic industry development: The status quo, problems and approaches. Appl. Energy 2014, 118, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; He, J.; Hu, S. Driving force model to evaluate China’s photovoltaic industry: Historical and future trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Z. Life-cycle assessment of multi-crystalline photovoltaic (PV) systems in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, P.T.; Salvia, A.L.; Rebelatto, B.G.; Brandli, L.L. Promoting sustainability in the solar industry: Bibliometric and systematic analysis of alternatives for the end-of-life of photovoltaic modules. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; He, Y. Insights for China from EU management of recycling end-of-life photovoltaic modules. Sol. Energy 2024, 273, 112532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Deng, J.; Mi, Q.; Li, J. How much carbon dioxide has the Chinese PV manufacturing industry emitted? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhu, K.; Wang, S. The potential for reducing China’s carbon dioxide emissions: Role of foreign-invested enterprises. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 35, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latunussa, C.E.; Ardente, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Mancini, L. Life Cycle Assessment of an innovative recycling process for crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 156, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quitzow, R.; Huenteler, J.; Asmussen, H. Development trajectories in China’s wind and solar energy industries: How technology-related differences shape the dynamics of industry localization and catching up. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 158, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, L.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Xie, K. Technological progress and coupling renewables enable substantial environmental and economic benefits from coal-to-olefins. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Shaping the solar future: An analysis of policy evolution, prospects and implications in China’s photovoltaic industry. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zou, H.; Qiu, Y.; Du, H. Consumer reaction to green subsidy phase-out in China: Evidence from the household photovoltaic industry. Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukarica, V.; Tomsic, Z. Energy efficiency policy evaluation by moving from techno-economic towards whole society perspective on energy efficiency market. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Virtuous cycle of solar photovoltaic development in new regions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandor, D.; Fulton, S.; Engel-Cox, J.; Peck, C.; Peterson, S. System Dynamics of Polysilicon for Solar Photovoltaics: A Framework for Investigating the Energy Security of Renewable Energy Supply Chains. Sustainability 2018, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Qi, S.; Xu, T. In the post-subsidy era: How to encourage mere consumers to become prosumers when subsidy reduced? Energy Policy 2023, 174, 113451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onabowale, O. Energy policy and sustainable finance: Navigating the future of renewable energy and energy markets. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 25, 2235–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, N.M.; van den Bergh, J.C.; Lacerda, J.S. Allocating subsidies to R&D or to market applications of renewable energy? Balance and geographical relevance. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2013, 17, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tang, G.; Wang, R.; Sun, Y. Multi-Objective Optimization for China’s Power Carbon Emission Reduction by 2035. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 28, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Fan, W.; Lin, H.; Li, N.; Li, P.; Ju, L.; Zhou, F. A Risk Aversion Dispatching Optimal Model for a Micro Energy Grid Integrating Intermittent Renewable Energy and Considering Carbon Emissions and Demand Response. Processes 2019, 7, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhou, R.; Li, J. Rushing for subsidies: The impact of feed-in tariffs on solar photovoltaic capacity development in China. Appl. Energy 2021, 281, 116007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlet, T.; Ribeiro, J.; Savian, F.; Siluk, J. Value chain in distributed generation of photovoltaic energy and factors for competitiveness: A systematic review. Sol. Energy 2020, 211, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L. Research on Coupling Coordination Development for Photovoltaic Agriculture System in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, D.; Fang, Z.; Shui, L. An analysis on investment policy effect of China’s photovoltaic industry based on feedback model. Appl. Energy 2014, 135, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Gu, Z.; He, C.; Chen, W. The impact of the belt and road initiative on Chinese PV firms’ export expansion. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 25763–25783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutert, W. Innovation through iteration: Policy feedback loops in China’s economic reform. World Dev. 2021, 138, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Dimension | Definition | Representative Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Support | Policy Mechanism | Government incentives such as subsidies, tax reliefs, and policy mandates | Jia et al. (2016) [28] |

| Feed-in Tariff | Policy Mechanism | Guaranteed electricity price to ensure return on investment for renewables | Song et al. (2023) [29] |

| Carbon Border Tax | Institutional–Market | Cross-border tax applied to imports based on carbon content | Chen (2024) [7] |

| LCOE | Economic & Cost Structure | Levelized cost of electricity across life-cycle costs | Fan et al. (2019) [30] |

| Production Cost | Economic & Cost Structure | Total manufacturing cost including labor and materials | Castellanos et al. (2018) [12] |

| Technology Innovation | Tech & Sustainability | Advancement and diffusion of novel PV technologies | Shubbak (2019) [31] |

| Carbon Emissions | Tech & Sustainability | Lifecycle GHG emissions associated with PV modules | Yang et al. (2015) [32] |

| Green Finance | Institutional–Market | Financial mechanisms enabling environmental investment | Wei et al. (2023) [33] |

| Institutional Coordination | Institutional–Market | Harmonization of policy, regulation, and market implementation | Urban et al. (2016) [34] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Pereira, M.E.T. Reassessing the International Competitiveness and Economic Sustainability of China’s Solar PV Industry: A Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis. Energies 2026, 19, 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020508

Liu L, Pereira MET. Reassessing the International Competitiveness and Economic Sustainability of China’s Solar PV Industry: A Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis. Energies. 2026; 19(2):508. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020508

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lijing, and Maria Elisabeth Teixeira Pereira. 2026. "Reassessing the International Competitiveness and Economic Sustainability of China’s Solar PV Industry: A Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis" Energies 19, no. 2: 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020508

APA StyleLiu, L., & Pereira, M. E. T. (2026). Reassessing the International Competitiveness and Economic Sustainability of China’s Solar PV Industry: A Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis. Energies, 19(2), 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020508