Experimental Evaluation of the Bioenergy Potential of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Orejero) Fruit Peel Residue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

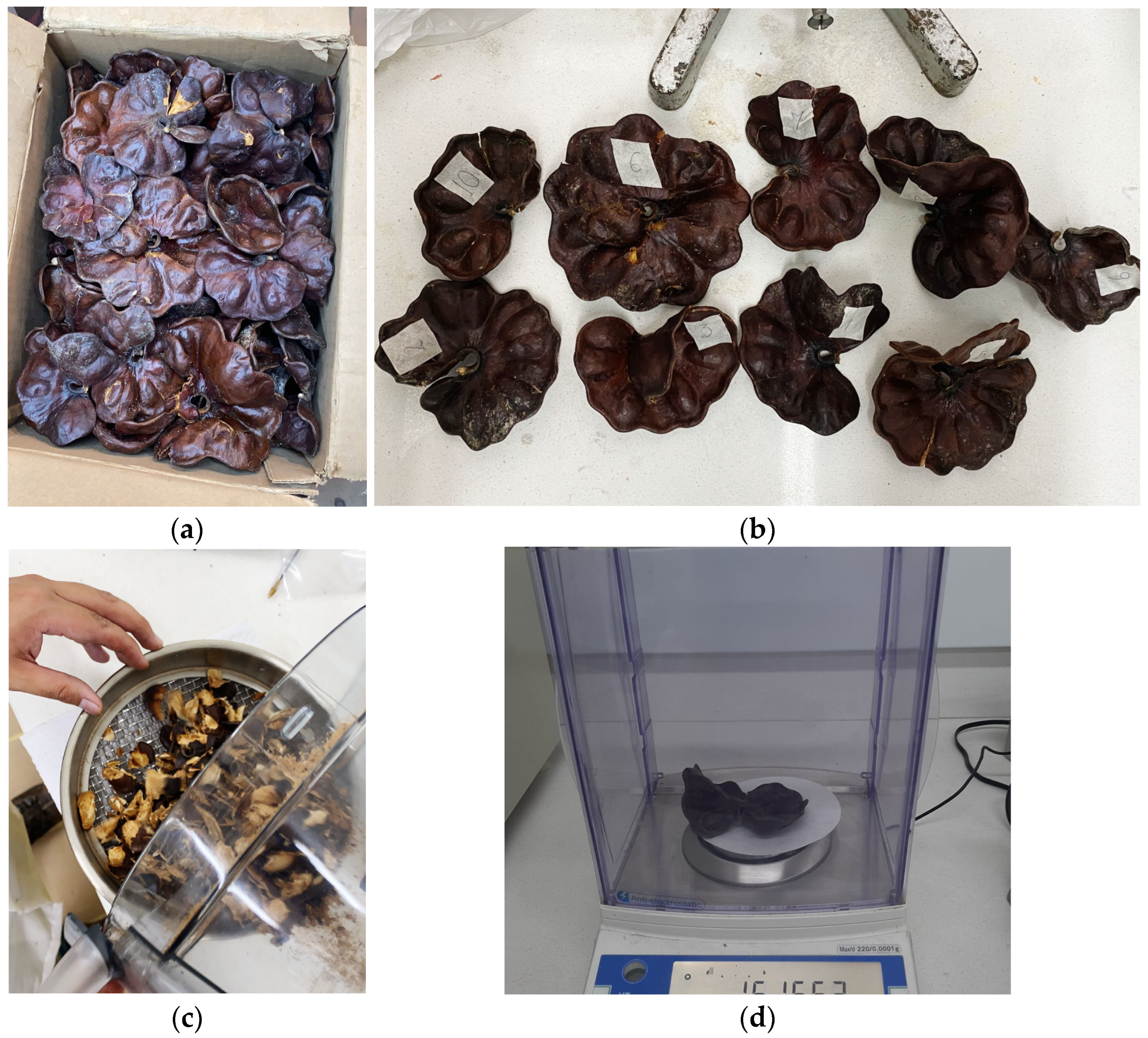

2.1. Residue Percentage and Moisture Content

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis

2.3. Theoretical Energy Potential Calculation Methodology

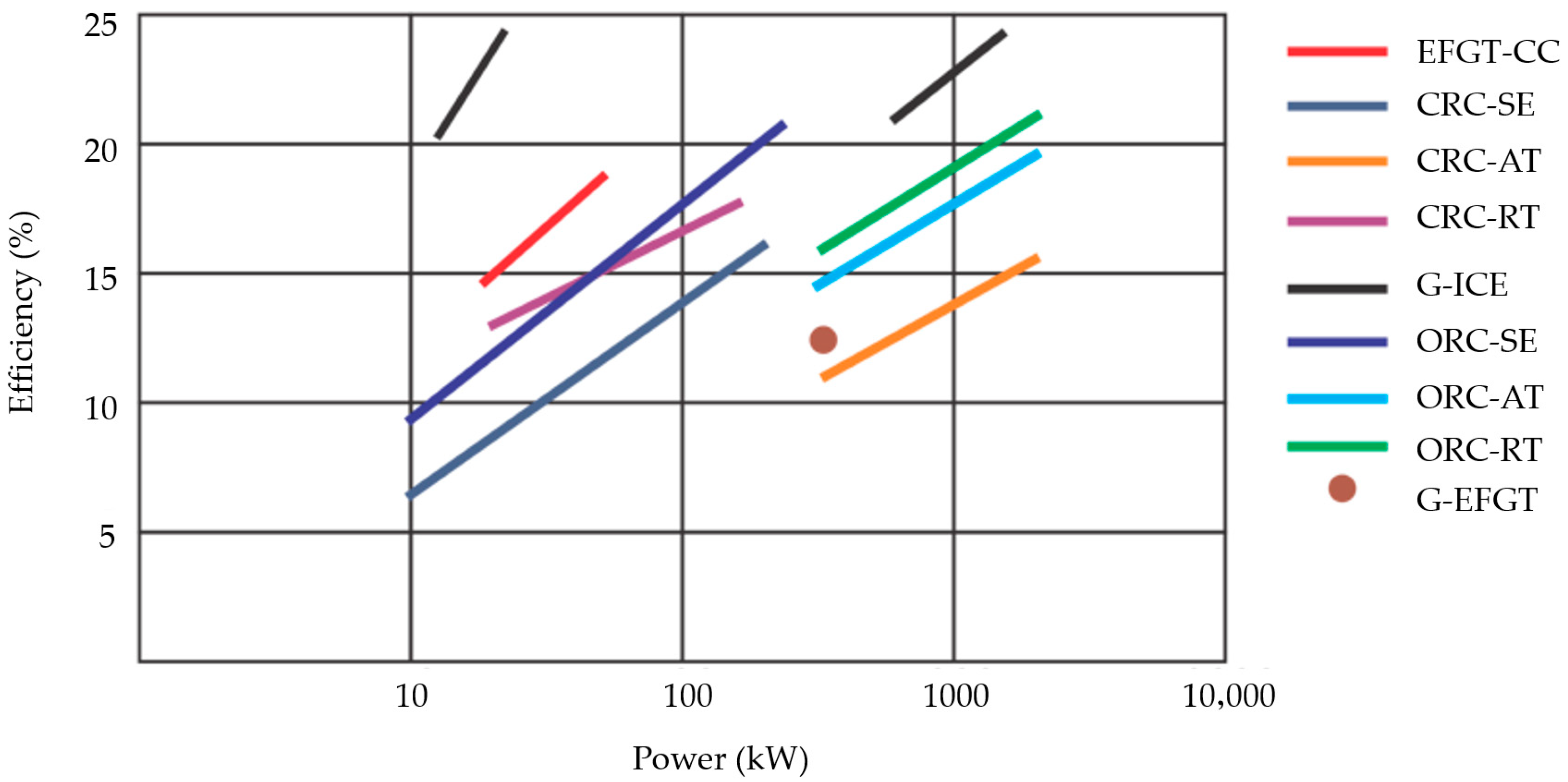

2.4. Selection of Energy Conversion Technologies

2.5. Technical Energy Potential Calculation Methodology

2.6. Emissions Estimation Methodology

a CO2 + (b/2) H2O + (d/2) N2 + e SO2 + 3.76 νO2 N2

νCO CO + νCO2 CO2 + νH2 H2 + νCH4 CH4 + νH2O H2O + νN2 N2 + νH2S H2S

3. Results

3.1. Residue Percentage and Moisture Content

3.2. Physicochemical Analysis

3.3. Theoretical Energy Potential

3.4. Technical Energy Potential

3.5. Emissions Estimation

4. Discussion

4.1. Energy Potential of E. cyclocarpum Peel in the Context of Residual Biomass

4.2. Technical Assessment of Conversion Technologies

4.3. Environmental Implications and CO2-Equivalent Emissions

4.4. Limitations of the Study

4.5. Perspectives for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonzales, E.; Hamrick, J.L.; Smouse, P.E.; Trapnell, D.W.; Peakall, R. The impact of landscape disturbance on spatial genetic structure in the Guanacaste tree, Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Fabaceae). J. Hered. 2010, 101, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Ortiz, M.K.; Duarte-Quintero, L.P. Uso del fruto orejero (Enterolobium cyclocarpum) en la alimentación bovina. In Proceedings of the IV Foro-DIE 2022 (Zootecnia–Ocaña), Ocaña, Colombia, 20 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Falowo, O.A.; Oloko-Oba, M.I.; Betiku, E. Biodiesel production intensification via microwave irradiation-assisted transesterification of oil blend using nanoparticles from elephant-ear tree pod husk as a base heterogeneous catalyst. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2019, 140, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bout, A.E.; Pfau, S.F.; van der Krabben, E.; Dankbaar, B. Residual Biomass from Dutch Riverine Areas—From Waste to Ecosystem Service. Sustainability 2019, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Martínez, G.; Buriticá Arboleda, C.; Silva Lora, E. Electric Power from Agricultural Residual Biomass (ARB) in Colombia—Option of Rural Development after the Armed Conflict. In Proceedings of the 26th European Biomass Conference and Exhibition (EUBCE), Copenhagen, Denmark, 14–17 May 2018; pp. 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, N.S.; Felby, C.; Thorsen, B.J. Agricultural residue production and potentials for energy and materials services. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2014, 40, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcıoğlu, A.O.; Dayıoğlu, M.A.; Türker, U. Assessment of the energy potential of agricultural biomass residues in Turkey. Renew. Energy 2019, 138, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética. Plan Energético Nacional Colombia: Ideario Energético 2050; Ministerio de Minas y Energía: Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. Available online: https://www1.upme.gov.co/documents/pen_idearioenergetico2050.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Solano, I.; Aguilar, O.; Dominguez, C.; Ramirez, G.; Aguilar, O. Evaluación del rendimiento energético del bagazo de caña de un ingenio azucarero vs su aprovechamiento mediante gasificación. Rev. Inic. Cient. 2020, 6, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, O.A.; Cárdenas, G.J.; Mentz, L.F. Poder calorífico superior de bagazo, médula y sus mezclas, provenientes de la caña de azúcar de Tucumán, R. Argentina. Rev. Ind. Agric. Tucumán 2010, 87, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza Rojas, E. Pirólisis de la Fibra de Palma Africana de Aceite; Universidad de los Andes (Uniandes): Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Saad, M.J.; Solís-Chaves, J.S.; Murillo-Arango, W. Suitable municipalities for biomass energy use in Colombia based on a multicriteria analysis from a sustainable development perspective. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarra-Mojica, D.M.; Prada-Soto, M.L.; Monroy-Sarmiento, L.S.; Duarte-Rodríguez, L.A. Energy potential of agricultural residual biomass in municipalities of the highlands of the Santurbán Páramo, Colombia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1672988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Romero, T.E.; Cabello Eras, J.J.; Sagastume Gutierrez, A.; Mendoza Fandiño, J.M.; Rueda Bayona, J.G. The Energy Potential of Agricultural Biomass Residues for Household Use in Rural Areas in the Department La Guajira (Colombia). Sustainability 2025, 17, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.A.; Ortiz, G.A. Estimación del Potencial Energético a Partir de la Biomasa Primaria Agrícola en el Departamento de Putumayo; Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11349/30055 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Vergara, J.C.; Rojas, G.; Ortegon, K. Sugarcane straw recovery for bioenergy generation: A case of an organic farm in Colombia. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 7950–7955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özyuğuran, A.; Yaman, S. Prediction of calorific value of biomass from proximate analysis. Energy Procedia 2017, 107, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajdak, M.; Velázquez-Martí, B.; López-Cortés, I. Quantitative and qualitative characteristics of biomass derived from pruning Phoenix canariensis hort. ex Chabaud and Phoenix dactylifera L. Renew. Energy 2014, 71, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bača, P.; Mašán, V.; Vanýsek, P.; Burg, P.; Binar, T.; Suchý, P.; Vaňková, L. Evaluation of the Thermal Energy Potential of Waste Products from Fruit Preparation and Processing Industry. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Jia, D.; Evrendilek, F.; Liu, J. Pyrolytic Valorization of Polygonum multiflorum Residues: Kinetic, Thermodynamic, and Product Distribution Analyses. Processes 2025, 13, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.S.; Liew, R.K.; Cheng, C.K.; Rasit, N.; Ooi, C.K.; Ma, N.L.; Ng, J.H.; Lam, W.H.; Chong, C.T.; Chase, H.A. Pyrolysis production of fruit peel biochar for potential use in treatment of palm oil mill effluent. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 213, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajoo, A.; Wong, Y.L.; Khoo, K.S.; Chen, W.-H.; Show, P.L. Biochar production via pyrolysis of citrus peel fruit waste as a potential usage as solid biofuel. Chemosphere 2022, 294, 133671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collí Pacheco, J.P. Estudio del Efecto del Contenido y Tamaño de Partículas de la Testa de la Semilla del Fruto de Pich (Enterolobium cyclocarpum) Sobre las Propiedades de un Almidón Termoplástico a Base de Dicho Fruto. Master’s Thesis, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán (CICY), Posgrado en Materiales Poliméricos, Mérida, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arango Osorno, S.E.; Montoya Restrepo, J.; Vásquez, Y.; Flor, D.Y. Análisis fisicoquímico del proceso de co-compostaje de biomasa de leguminosa y ruminaza. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Hortíc. 2017, 10, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, J.C.; Riquelme Espergue, F.; Acuña Aroca, B. Antecedentes iniciales para la utilización de especies de Salix como biomasa para energía en la Región de Aysén. Cienc. Investig. For. 2021, 27, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética (UPME). Anexo D: Modelos Matemáticos para Evaluar Potencial Energético de Biomasa Residual. In Atlas del Potencial Energético de la Biomasa Residual en Colombia; UPME: Bogotá, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt. Programa Nacional para la Conservación y Restauración del Bosque Seco Tropical en Colombia: Plan de Acción 2020–2030; Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021.

- Pizano, C.; García, H. (Eds.) El Bosque Seco Tropical en Colombia; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH): Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E.; Gil-Tobón, C.; Gutiérrez, J.P.; Alcázar-Caicedo, C.; Moscoso-Higuita, L.G.; Becerra, L.A.; Loo, J.; González, M.A. Genetic diversity of Enterolobium cyclocarpum in Colombian seasonally dry tropical forest: Implications for conservation and restoration. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropical Forages. Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. (Species Profile/Fact Sheet). 2020. Available online: https://tropicalforages.info/pdf/enterolobium_cyclocarpum.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- PCE Ibérica. Balanza de Humedad Mini Serie PCE-MB C. 25 February 2023. Available online: https://www.pce-iberica.es/medidor-detalles-tecnicos/balanzas/balanza-humedad-pce-mb-c.htm (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- ASTM D5373-16; Standard Test Methods for Determination of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Nitrogen in Analysis Samples of Coal and Carbon in Analysis Samples of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM E711-06(2018); Standard Test Method for Gross Calorific Value of Refuse-Derived Fuel by the Bomb Calorimeter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- European Commission. Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for Large Combustion Plants. Industrial Emissions Directive 2010/75/EU (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control); JRC Science for Policy Report; EUR 28836 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Estudios Tecnológicos Prospectivos. Documento de Referencia Sobre las Mejores Técnicas Disponibles en el Ámbito de las Grandes Instalaciones de Combustión; Centro Común de Investigación: Sevilla, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rincón Martínez, J.M.; Silva Lora, E.E. Bioenergía: Fuentes, Conversión y Sustentabilidad; Red Iberoamericana de Aprovechamiento de Residuos Orgánicos en Producción de Energía: Bogotá, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Aguilar, D. Tecnologías para la Generación de Energía a Partir de la Biomasa Forestal; Universidad Nacional de Ciencias Forestales: Siguatepeque, Honduras, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rettig, A.; Lagler, M.; Lamare, T.; Li, S.; Mahadea, V.; McCallion, S.; Chernushevich, J. Application of Organic Rankine Cycles (ORC). In Proceedings of the World Engineers Convention, Geneva, Switzerland, 4–9 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arnavat, M. Performance Modeling and Validation of Biomass Gasifiers for Trigeneration Plants. Doctoral Thesis, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres-Martínez, L.E.; Guío-Pérez, D.C.; Rincón Prat, S.L. Potencial energético teórico y técnico de biomasa residual disponible en Colombia para el aprovechamiento en procesos de transformación termoquímica. In Proceedings of the 3er Congreso de Energía Sostenible, Bogotá, Colombia, 24–26 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scarlat, N.; Martinov, M.; Dallemand, J.-F. Assessment of the availability of agricultural crop residues in the European Union: Potential and limitations for bioenergy use. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. World crop residues production and implications of its use as a biofuel. Environ. Int. 2005, 31, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornweg, D.; Bhada-Tata, P. What a Waste: A Global Review of Solid Waste Management; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/17388 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Demirbaş, A. Biomass resource facilities and biomass conversion processing for fuels and chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2001, 42, 1357–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, P. Energy production from biomass (part 1): Overview of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 83, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Bioenergy and Food Security: The BEFS Analytical Framework; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Global Bioenergy Supply and Demand Projections: A Working Paper for REmap 2030; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E870-82(2013); Standard Test Methods for Analysis of Wood Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- ASTM D3176-24; Standard Practice for Ultimate Analysis of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- González Garcia, R.A. Simulación del Proceso de Gasificación de Biomasa; Universidad EAFIT: Medellín, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, P.E.R. Espécies Arbóreas Brasileiras; Embrapa Florestas: Colombo, Brazil, 2008; Available online: http://jbb.ibict.br/handle/1/1476 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Orwa, C.; Mutua, A.; Kindt, R.; Simons, A.; Jamnadass, R. Agroforestree Database: A Tree Species Reference and Selection Guide; World Agroforestry: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, V.C.; Lorenzi, H. Botânica Sistemática: Guia Ilustrado para Identificação das Famílias de Angiospermas da Flora Brasileira, Baseado em APG II; Plantarum: Nova Odessa, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Valencia, N.; Zambrano Franco, D.A. Los subproductos del café: Fuente de energía renovable. Av. Tec. Cenicafé 2010, 393, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética (UPME). Anexo B. Muestreo Caracterización Biomasa Residual. In Atlas del Potencial Energético de la Biomasa Residual en Colombia; UPME: Bogotá, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética (UPME). Anexo A: Biomasa, Fuente Renovable de Energía. In Atlas del Potencial Energético de la Biomasa Residual en Colombia; UPME: Bogotá, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, L.; Hu, Y.; Naterer, G. Critical review of the role of ash content and composition in biomass pyrolysis. Front. Fuels 2024, 2, 1378361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Urbina, A. Caracterización de biomasas lignocelulósicas y su procesamiento térmico: Estado y oportunidades en el Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica. Rev. Tecnol. Marcha 2022, 35, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño Martínez, P.E. Vegetable residual biomass: Technologies of transformation and current status. Innovaciencia 2014, 2, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiano, M. Estudio de Emisión de Gases Procedentes de un Sistema de Aprovechamiento de Biomasa. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Escuela Politécnica Superior (Linares), Linares, Jaén, Spain, 25 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, P. Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis: Practical Design and Theory; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Knoef, H.A.M. (Ed.) Handbook Biomass Gasification; BTG Biomass Technology Group: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Turns, S.R. An Introduction to Combustion: Concepts and Applications, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative. Scoping Elements for Biogenic Carbon in Life Cycle Assessment; United Nations Environment Programme/SETAC: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IEA Bioenergy. Carbon Accounting in Bio-CCUS Supply Chains; IEA Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kludze, H.; Deen, B.; Weersink, A.; Van Acker, R.; Janovicek, K.; De Laporte, A.; Mcdonald, I. Estimating sustainable crop residue removal rates and costs based on soil organic matter dynamics and rotational complexity. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 56, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Bioenergy. Agricultural Residues for Energy in Sweden; (Task 43 Report TR2016-05); IEA Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; He, Y.; Ren, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, N.; Li, L. The crop residue removal threshold ensures sustainable agriculture in the purple soil region of Sichuan, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouemara, K.; Shahbaz, M.; McKay, G.; Al-Ansari, T. The review of power generation from integrated biomass gasification and solid oxide fuel cells: Current status and future directions. Fuel 2024, 360, 130511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patuzzi, F.; Basso, D.; Vakalis, S.; Antolini, D.; Piazzi, S.; Benedetti, V.; Cordioli, E.; Baratieri, M. State-of-the-art of small-scale biomass gasification systems: An extensive and unique monitoring review. Energy 2021, 223, 120039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, Y.A.; Zhao, Z.; Yoshida, A.; Abudula, A.; Guan, G. Small-scale biomass gasification systems for power generation (<200 kW class): A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 117, 109486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarini, M.; Bocci, E.; Di Carlo, A.; Savuto, E.; Pallozzi, V. The case study of an innovative small scale biomass waste gasification heat and power plant contextualized in a farm. Energy Procedia 2015, 82, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GHG Protocol. Stationary Combustion Guidance; World Resources Institute (WRI): Washington, DC, USA; World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD): Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zampori, L.; Pant, R. Suggestions for Updating the Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) Method; Joint Research Centre, European Commission: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, P.J.P.; Venturini, O.J.; Escobar Palacio, J.C.; Costa Silva, R.A.; Renó, M.L.G. Biomass based Rankine cycle, ORC and gasification system for electricity generation for isolated communities in Bonfim city, Brazil. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2019, 13, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feedipedia. Guanacaste (Enterolobium cyclocarpum). 2025. Available online: https://www.feedipedia.org/node/296 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

| Technologies | Electrical Efficiency (%) | Nominal Capacity (MW) |

|---|---|---|

| Small-scale gas engines | 20–32% | <0.5 |

| Large-scale gas engines | 26–36% | 0.5–3.0 |

| Diesel engines | 23–38% | >3.0 |

| Steam turbine | 15–35% | 1–50 |

| Small-scale gas turbine | 24–31% | 0.8–10 |

| Large-scale gas turbine | 26–31% | 10–100 |

| Combined cycle (Brayton + Rankine) | 30–45% | 1–30 |

| Combined cycle (Gas engine + Rankine) | 40–50% | 1–10 |

| Fuel cell | 35–60% | 0.01–1 |

| Stirling engine | 11–20% | <0.1 |

| Sample No. | Fruit Weight with Peel (g) | Seed Weight (g) | Peel Residue Weight (g) | Residue Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19.91 | 7.12 | 12.79 | 64.24 |

| 2 | 19.13 | 8.67 | 10.46 | 54.68 |

| 3 | 18.14 | 6.74 | 11.39 | 62.79 |

| 4 | 13.02 | 4.57 | 8.45 | 64.90 |

| 5 | 20.98 | 8.51 | 12.47 | 59.44 |

| 6 | 28.10 | 12.81 | 15.29 | 54.41 |

| 7 | 15.15 | 4.37 | 10.79 | 71.22 |

| 8 | 20.81 | 11.15 | 9.66 | 46.42 |

| 9 | 11.76 | 2.28 | 9.48 | 80.61 |

| 10 | 12.75 | 5.20 | 7.54 | 59.14 |

| Average | 17.98 | 7.14 | 10.83 | 60.26 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Cultivated area (A) [ha/year] | 1 |

| Crop yield (Rc) [t fruit per ha·year] | 450 |

| Residue-to-product ratio (Mrg) [t wet peel per t fruit, experimental] | 0.60 |

| Dry matter fraction of the residue (Yrs) [t dry peel per t wet peel, from moisture content] | 0.89 |

| Parameter | Result | Units | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Heating Value | 0.015 | TJ/t | ASTM E711-06 [33] |

| Elemental Analysis | |||

| Nitrogen | 0.45 | % dry basis (DB) | ASTM D5373-16 [32] |

| Carbon | 37.2 | ||

| Sulfur | 0.13 | ||

| Hydrogen | 4.09 | ||

| Oxygen | 55.1 | ASTM D3176-24 [49] ASTM E870-82 [48] | |

| Ash | 3 | assumed | |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Theoretical Energy Potential (EP) [TJ/year] | 3.6 |

| LHV of Enterolobium cyclocarpum [BTU/lb] | 6435 |

| LHV of Enterolobium cyclocarpum [kcal/kg] | 3577.4 |

| LHV of Enterolobium cyclocarpum [TJ/t] | 0.015 |

| Crop | Residue | Theoretical Energy Potential Per Hectare (TJ/Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Sugarcane | Bagasse | 2.49 |

| Oil palm | Fiber | 0.35 |

| Coffee | Husk | 0.0043 |

| E. cyclocarpum | Peel | 3.6 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Technical energy potential—Combustion (TJ/year) | 0.18 |

| Technical energy potential—Gasification (TJ/year) | 0.21 |

| Theoretical energy potential (EP) (TJ/year) | 3.6 |

| IAR—Industrial agricultural residue | 0.6 |

| Constant | 0.4 |

| Technology efficiency—Combustion | 0.21 |

| Technology efficiency—Gasification | 0.25 |

| Technology | CO2 Equivalent (t CO2 eq/TJ) |

|---|---|

| Combustion | 0.0007 |

| Gasification | 3.5898 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gómez-Rosales, Z.-E.; Hernández-Mejía, P.-A.; Forero-González, A.-G.; Solano-Meza, J.-K.; Rodrigo-Ilarri, J.; Rodrigo-Clavero, M.-E. Experimental Evaluation of the Bioenergy Potential of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Orejero) Fruit Peel Residue. Energies 2026, 19, 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020360

Gómez-Rosales Z-E, Hernández-Mejía P-A, Forero-González A-G, Solano-Meza J-K, Rodrigo-Ilarri J, Rodrigo-Clavero M-E. Experimental Evaluation of the Bioenergy Potential of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Orejero) Fruit Peel Residue. Energies. 2026; 19(2):360. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020360

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez-Rosales, Zully-Esmeralda, Paola-Andrea Hernández-Mejía, Andrés-Gonzalo Forero-González, Johanna-Karina Solano-Meza, Javier Rodrigo-Ilarri, and María-Elena Rodrigo-Clavero. 2026. "Experimental Evaluation of the Bioenergy Potential of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Orejero) Fruit Peel Residue" Energies 19, no. 2: 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020360

APA StyleGómez-Rosales, Z.-E., Hernández-Mejía, P.-A., Forero-González, A.-G., Solano-Meza, J.-K., Rodrigo-Ilarri, J., & Rodrigo-Clavero, M.-E. (2026). Experimental Evaluation of the Bioenergy Potential of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Orejero) Fruit Peel Residue. Energies, 19(2), 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020360