Hotspots of Current Energy Potential in the Southwestern Tropical Atlantic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hotspot Identification from Climatology

2.2. Daily Extraction and CPD Computation Restricted to Hotspots

2.3. Statistical Analysis

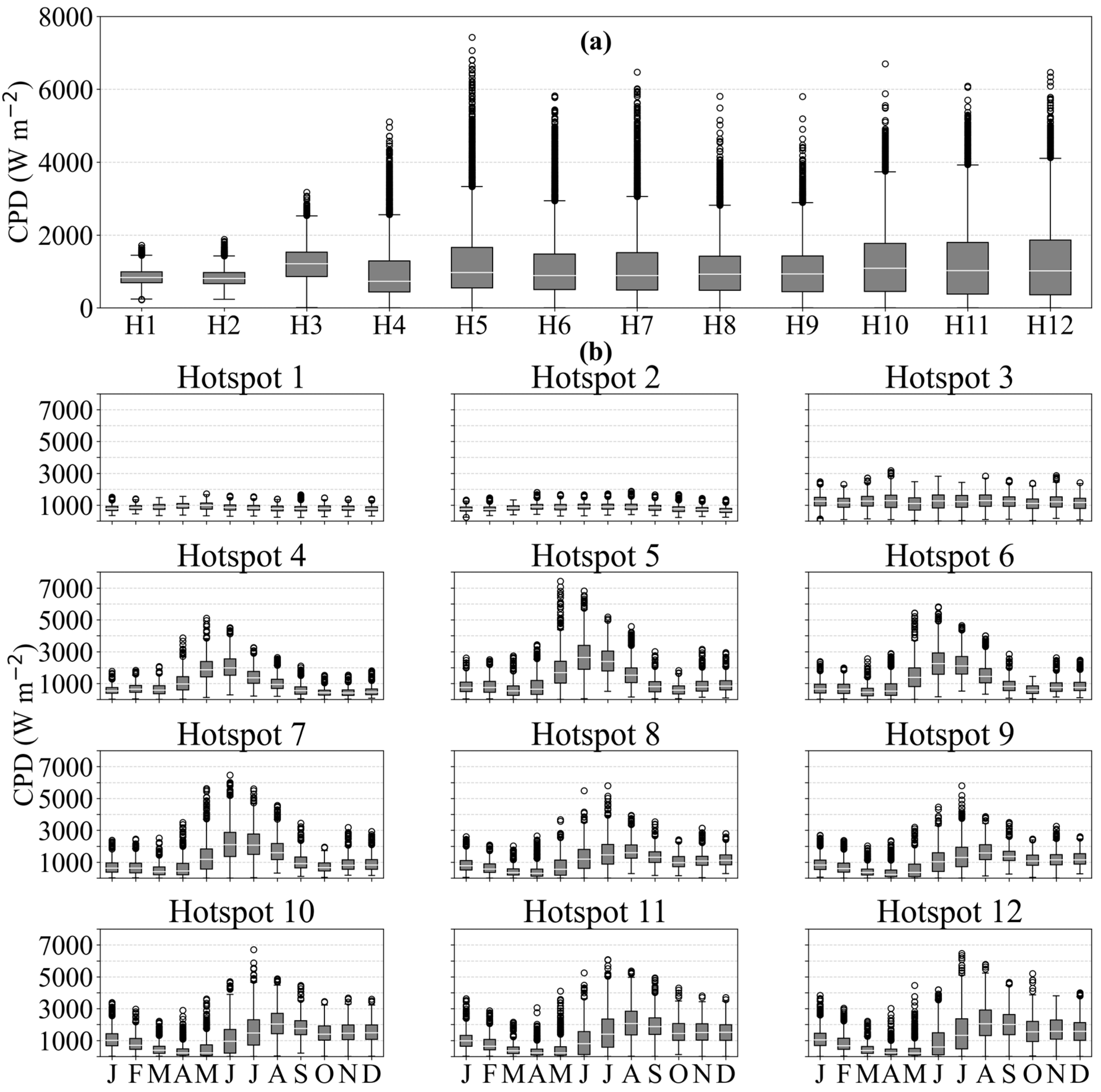

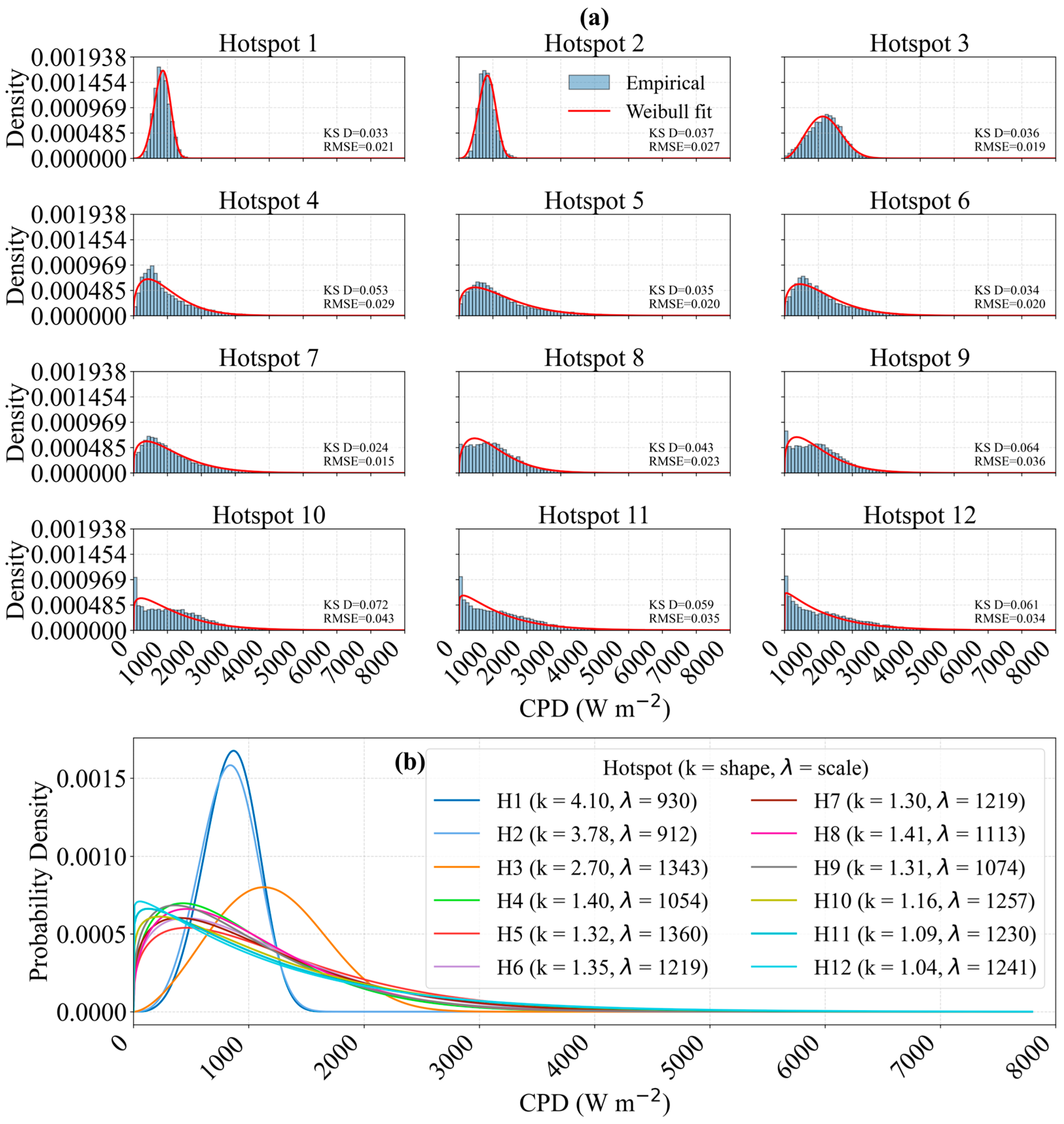

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Gaps and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAIW | Antarctic Intermediate Water |

| ADCP | Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler |

| AMOC | Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BC | Brazil Current |

| CapEx | Capital Expenditure |

| CE | Ceará (State of Brazil) |

| CF | Capacity Factor |

| CPD | Current Power Density |

| CSAM | Cross-stream Active Mooring |

| cSEC | Central South Equatorial Current |

| H1–H12 | Hotspots 1 to 12 |

| HSD | Honestly Significant Difference |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| ITCZ | Intertropical Convergence Zone |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| MA | Maranhão (State of Brazil) |

| MCED | Marine Current Energy Device |

| MCPD | Maximum Current Power Density |

| MHK | Marine Hydrokinetic |

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| NBC | North Brazil Current |

| NBUC | North Brazil Undercurrent |

| OpEx | Operational Expenditure |

| PA | Pará (State of Brazil) |

| PB | Paraíba (State of Brazil) |

| Probability Density Function | |

| PE | Pernambuco (State of Brazil) or Potiguar Eddy (context-dependent) |

| RN | Rio Grande do Norte (State of Brazil) |

| SEC | South Equatorial Current |

| sSEC | Southern South Equatorial Current |

| SUW | Subtropical Underwater |

| SWTA | Southwestern Tropical Atlantic |

| WBC | Western Boundary Current |

References

- Lewis, A.; Estefen, S.; Huckerby, J.; Musial, W.; Pontes, T.; Torres-Martinez, J. Ocean Energy. In IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Seyboth, K., Kadner, S., Zwickel, T., Eickemeier, P., Hansen, G., Schlömer, S., von Stechow, C., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.; Wei, Y.-M.; de la Vega Navarro, A.; Garg, A.; Hahmann, A.N.; Khennas, S.; Azevedo, I.M.L.; Löschel, A.; Singh, A.K.; Steg, L. Energy Systems. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 613–746. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Energy Statistics 2025; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.J.; Vijayamohan, V.; Field, R.W. On the potential of ocean energy technologies to contribute to future sustainability. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, N.D.; Epps, B.P. Hydrokinetic energy conversion: Technology, research, and outlook. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Błaszczak, B.; Godawa, S.; Kęsy, I. Human Safety in Light of the Economic, Social and Environmental Aspects of Sustainable Development—Determination of the Awareness of the Young Generation in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copping, A.E.; Martínez, M.L.; Hemery, L.G.; Hutchison, I.; Jones, K.; Kaplan, M. Recent Advances in Assessing Environmental Effects of Marine Renewable Energy Around the World. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2024, 58, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.L.; Chávez, V.; Silva, R.; Heckel, G.; Garduño-Ruiz, E.P.; Wojtarowski, A.; Vázquez, G.; Pérez-Maqueo, O.; Maximiliano-Cordova, C.; Salgado, K.; et al. Assessing the potential of marine renewable energy in Mexico: Socioeconomic needs, energy potential, environmental concerns, and social perception. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadman, M.; Silva, C.; Faller, D.; Wu, Z.; de Freitas Assad, L.; Landau, L.; Levi, C.; Estefen, S. Ocean Renewable Energy Potential, Technology, and Deployments: A Case Study of Brazil. Energies 2019, 12, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.-C.; Feng, A.-H.; Hsieh, C.; Fan, K.-H. Marine current power with Cross-stream Active Mooring: Part I. Renew. Energy 2017, 109, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, P.L. Power from marine currents. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2002, 216, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.A.; Khan, H.A.; Aziz, M. Harvesting Energy from Ocean: Technologies and Perspectives. Energies 2022, 15, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, L.I.; Ponta, F.L.; Chen, L. Advances and trends in hydrokinetic turbine systems. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2010, 14, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, T.; Nagaya, S.; Shimizu, M.; Saito, H.; Murata, S.; Handa, N. Development and demonstration test for floating type ocean current turbine system conducted in Kuroshio Current. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2018 MTS/IEEE Kobe Techno-Oceans (OTO), Kobe, Japan, 28–31 May 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rourke, F.O.; Boyle, F.; Reynolds, A. Marine current energy devices: Current status and possible future applications in Ireland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanZwieten, J.H.; Baxley, W.E.; Alsenas, G.M.; Meyer, I.; Muglia, M.; Lowcher, C.; Bane, J.; Gabr, M.; He, R.; Hudon, T.; et al. SS Marine Renewable Energy—Ocean Current Turbine Mooring Considerations. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 4–7 May 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.-W.; Liau, J.-M.; Liang, S.-J.; Tzang, S.-Y.; Doong, D.-J. Assessment of Kuroshio current power test site of Green Island, Taiwan. Renew. Energy 2015, 81, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, K.; Fritz, H.M.; French, S.P.; Neary, V.S. Assessment of Energy Production Potential from Ocean Currents Along the United States Coastline; Report No. DOE/EE/2661-10; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoughipour, M.; VanZwieten, J.; Tang, Y. Drifter-based global ocean current energy resource assessment. Renew. Energy 2025, 244, 122576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, F.A.; Fischer, J.; Stramma, L. Transports and Pathways of the Upper-Layer Circulation in the Western Tropical Atlantic. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1998, 28, 1904–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bane, J.M.; He, R.; Muglia, M.; Lowcher, C.F.; Gong, Y.; Haines, S.M. Marine Hydrokinetic Energy from Western Boundary Currents. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2017, 9, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowcher, C.F.; Muglia, M.; Bane, J.M.; He, R.; Gong, Y.; Haines, S.M. Marine Hydrokinetic Energy in the Gulf Stream Off North Carolina: An Assessment Using Observations and Ocean Circulation Models. In Marine Renewable Energy; Yang, Z., Copping, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, F.A.; Dengler, M.; Zantopp, R.; Stramma, L.; Fischer, J.; Brandt, P. The Shallow and Deep Western Boundary Circulation of the South Atlantic at 5°–11° S. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2005, 35, 2031–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleda, D.; Araujo, M.; Zantopp, R.; Montagne, R. Intraseasonal variability of the North Brazil Undercurrent forced by remote winds. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2012, 117, C11024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Gabioux, M.; Almeida, M.M.; Cirano, M.; Paiva, A.M.; Aguiar, A.L. The Bifurcation of The Western Boundary Current System of The South Atlantic Ocean. Rev. Bras. Geophys. 2014, 32, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, A.N.; Silva, A.C.; Chaigneau, A.; Eldin, G.; Araujo, M.; Bertrand, A. Near-surface western boundary circulation off Northeast Brazil. Prog. Oceanogr. 2021, 190, 102475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, I.C.A.; de Miranda, L.B.; Brown, W.S. On the origins of the North Brazil Current. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1994, 99, 22501–22512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramma, L.; Fischer, J.; Reppin, J. The North Brazil Undercurrent. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1995, 42, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummels, R.; Brandt, P.; Dengler, M.; Fischer, J.; Araujo, M.; Veleda, D.; Durgadoo, J.V. Interannual to decadal changes in the western boundary circulation in the Atlantic at 11° S. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 7615–7622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, A.; Pelegrí, J.L.; Vallès-Casanova, I. Subtropical-Tropical Transfer in the South Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 4820–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.R.; Rothstein, L.M.; Wimbush, M. Seasonal Variability of the South Equatorial Current Bifurcation in the Atlantic Ocean: A Numerical Study. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2007, 37, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlès, B.; Molinari, R.L.; Johns, E.; Wilson, W.D.; Leaman, K.D. Upper layer currents in the western tropical North Atlantic (1989–1991). J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1999, 104, 1361–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.V.N.; da Silva, A.C. Seawater temperature changes associated with the North Brazil current dynamics. Ocean Dyn. 2014, 64, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, W.E.; Lee, T.N.; Beardsley, R.C.; Candela, J.; Limeburner, R.; Castro, B. Annual Cycle and Variability of the North Brazil Current. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1998, 28, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.O.; Cirano, M.; Mata, M.M.; Goes, M.; Goni, G.; Baringer, M. An assessment of the Brazil Current baroclinic structure and variability near 22° S in Distinct Ocean Forecasting and Analysis Systems. Ocean Dyn. 2016, 66, 893–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleda, D.; Araújo, M.; Silva, M.; Montagne, R. Seasonal and interannual variability of the southern south Equatorial Current bifurcation and meridional transport along the eastern brazilian edge. Trop. Oceanogr. 2011, 39, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasceno, Ú.M.; Cintra, M.M.; Gomes, M.P.; Vital, H. Interactions between the North Brazilian Undercurrent (NBUC) and the Southwest Atlantic Margin. Implications for Brazilian shelf-edge systems. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 54, 102486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembruscki, S.G.; Barreto, H.T.; Palma, J.C.; Milliman, J.D. Estudo preliminar das províncias geomorfológicas da margem continental brasileira. An. Congr. Bras. Geol. 1972, 26, 187–209. Available online: https://www.sbgeo.org.br/assets/admin/imgCk/files/Anais/ANAIS%20DO%20XXVI%20CBG_1972_V2.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Coutinho, P.N. Levantamento do Estado da arte da Pesquisa dos Recursos Vivos Marinhos do Brasil-Oceanografia Geológica; Região Nordeste; Programa REVIZEE; Ministério Do Meio Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 1996; 97p.

- Buarque, B.V.; Barbosa, J.A.; Magalhães, J.R.G.; Cruz Oliveira, J.T.; Filho, O.J.C. Post-rift volcanic structures of the Pernambuco Plateau, northeastern Brazil. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2016, 70, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.V.B.; Ferreira, B.; Maida, M.; Queiroz, S.; Silva, M.; Varona, H.L.; Araújo, T.C.M.; Araújo, M. Flow-topography interactions in the western tropical Atlantic boundary off Northeast Brazil. J. Mar. Syst. 2022, 227, 103690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramma, L.; Schott, F. The mean flow field of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 1999, 46, 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramma, L.; England, M. On the water masses and mean circulation of the South Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1999, 104, 20863–20883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, L.D. Antarctic intermediate water in the South Atlantic. In The South Atlantic; Wefer, G., Berger, W.H., Siedler, G., Webb, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lellouche, J.-M.; Eric, G.; Romain, B.-B.; Gilles, G.; Angélique, M.; Marie, D.; Clément, B.; Mathieu, H.; Olivier, L.G.; Charly, R.; et al. The Copernicus Global 1/12° Oceanic and Sea Ice GLORYS12 Reanalysis. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 698876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassignet, E.P.; Hurlburt, H.E.; Smedstad, O.M.; Halliwell, G.R.; Hogan, P.J.; Wallcraft, A.J.; Baraille, R.; Bleck, R. The HYCOM (HYbrid Coordinate Ocean Model) data assimilative system. J. Mar. Syst. 2007, 65, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forget, G.; Campin, J.M.; Heimbach, P.; Hill, C.N.; Ponte, R.M.; Wunsch, C. ECCO version 4: An integrated framework for non-linear inverse modeling and global ocean state estimation. Geosci. Model Dev. 2015, 8, 3071–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowles, G.W.; Hakim, A.R.; Churchill, J.H. A comparison of numerical and analytical predictions of the tidal stream power resource of Massachusetts, USA. Renew. Energy 2017, 114, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, P. Étude comparative de la distribution florale dans une portion des Alpes et des Jura. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 1901, 37, 547–579. [Google Scholar]

- Justus, C.G.; Hargraves, W.R.; Mikhail, A.; Graber, D. Methods for Estimating Wind Speed Frequency Distributions. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1978, 17, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirinus, E.P.; Marques, W.C. Viability of the application of marine current power generators in the south Brazilian shelf. Appl. Energy 2015, 155, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazy, Y.; Gildor, H. On the probability and spatial distribution of ocean surface currents. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2011, 41, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguro, J.V.; Lambert, T.W. Modern estimation of the parameters of the Weibull wind speed distribution for wind energy analysis. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2000, 85, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, R.V.; Silva, A.C.; Roy, A.; Bourlès, B.; Silva, C.H.S.; Ternon, J.-F.; Araujo, M.; Bertrand, A. 3D characterisation of the thermohaline structure in the southwestern tropical Atlantic derived from functional data analysis of in situ profiles. Prog. Oceanogr. 2020, 187, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krelling, A.P.M.; da Silveira, I.C.A.; Polito, P.S.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Martins, R.P.; Lima, J.A.M.; Marin, F.O. A Newly Observed Quasi-stationary Subsurface Anticyclone of the North Brazil Undercurrent at 4° S: The Potiguar Eddy. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2020, 125, e2020JC016268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, D.L.; Tao, L. On the motion of linearly stratified rotating fluids past capes. J. Fluid Mech. 1987, 180, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doglioli, A.M.; Griffa, A.; Magaldi, M.G. Numerical study of a coastal current on a steep slope in presence of a cape: The case of the Promontorio di Portofino. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2004, 109, C12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaldi, M.G.; Özgökmen, T.M.; Griffa, A.; Chassignet, E.P.; Iskandarani, M.; Peters, H. Turbulent flow regimes behind a coastal cape in a stratified and rotating environment. Ocean Model. 2008, 25, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelao, R.M.; Luo, H. Upwelling jet separation in the California Current System. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, C.; Schafer, H.; Podesta, G.; Zenk, W. The Vitória Eddy and its relation to the Brazil Current. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1995, 25, 2532–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.E.; Adrian, E. Atmosphere-Ocean Dynamics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman-Roisin, B.; Beckers, J.-M. Introduction to Geophysical Fluid Dynamics: Physical and Numerical Aspects; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huthnance, J.M. Circulation, exchange and water masses at the ocean margin: The role of physical processes at the shelf edge. Prog. Oceanogr. 1995, 35, 353–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, K.H. Cross-Shelf Exchange. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2016, 8, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, J.C. The nature and consequences of oceanic eddies. In Ocean Modeling in an Eddying Regime; Hecht, M.W., Hasumi, H., Eds.; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.G.; Heap, A.D. National-scale wave energy resource assessment for Australia. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Assad, L.P.; Toste, R.; Böck, C.S.; Nehme, D.M.; Sancho, L.; Soares, A.E.; Landau, L. Ocean climatology at Brazilian Equatorial Margin: A numerical approach. J. Comput. Sci. 2020, 44, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, S.P.; Hashemi, M.R. Wave power variability over the northwest European shelf seas. Appl. Energy 2013, 106, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Neill, S.P.; Robins, P.E.; Hashemi, M.R. Resource assessment for future generations of tidal-stream energy arrays. Energy 2015, 83, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, S.P.; Hashemi, M.R.; Lewis, M.J. Tidal energy leasing and tidal phasing. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reikard, G.; Robertson, B.; Bidlot, J.-R. Combining wave energy with wind and solar: Short-term forecasting. Renew. Energy 2015, 81, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, V.S.; Lawson, M.; Previsic, M.; Copping, A.; Hallett, K.C.; Labonte, A.; Rieks, J.; Murray, D. Methodology for Design and Economic Analysis of Marine Energy Conversion (MEC) Technologies; SAND2014-9040; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bedard, R.; Previsic, M.; Polagye, B.; Hagerman, G.; Casavant, A.; Tarbell, D. North America Tidal In-Stream Energy Conversion Technology Feasibility Study; EPRI Report TP-008-NA; Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI): Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, L.; Howland, M.F. Quantitative Evaluation of Reanalysis and Numerical Weather Prediction Models for Wind Resource Assessment in Offshore Environments. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2025JD043490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, A.; Tahir, Z.U.R.; Asim, M.; Hayat, N.; Farooq, M.; Abdullah, M.; Azhar, M. Evaluation of reanalysis and analysis datasets against measured wind data for wind resource assessment. Energy Environ. 2023, 34, 1258–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, R.K. Assessment of wind energy potential using reanalysis data: A comparison with mast measurements. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsley, R.C.; Candela, J.; Limeburner, R.; Geyer, W.R.; Lentz, S.J.; Castro, B.M.; Cacchione, D.; Carneiro, N. The M2 tide on the Amazon Shelf. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1995, 100, 2283–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell Geyer, W.; Beardsley, R.C.; Lentz, S.J.; Candela, J.; Limeburner, R.; Johns, W.E.; Castro, B.M.; Dias Soares, I. Physical oceanography of the Amazon shelf. Cont. Shelf Res. 1996, 16, 575–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabioux, M.; Vinzon, S.B.; Paiva, A.M. Tidal propagation over fluid mud layers on the Amazon shelf. Cont. Shelf Res. 2005, 25, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bars, Y.; Lyard, F.; Jeandel, C.; Dardengo, L. The AMANDES tidal model for the Amazon estuary and shelf. Ocean Model. 2010, 31, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestes, Y.O.; Silva, A.C.; Jeandel, C. Amazon water lenses and the influence of the North Brazil Current on the continental shelf. Cont. Shelf Res. 2018, 160, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianca, C.; Mazzini, P.L.; Siegle, E. Brazilian offshore wave climate based on NWW3 reanalysis. Braz. J. Oceanogr. 2010, 58, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espindola, R.L.; Araújo, A.M. Wave energy resource of Brazil: An analysis from 35 years of ERA-Interim reanalysis data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beserra, E.R.; Mendes, A.L.T.; Estefen, S.F.; Parente, C.E. Wave Climate Analysis for a Wave Energy Conversion Application in Brazil. In Proceedings of the ASME 2007 26th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–15 June 2007; pp. 837–844. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, P.; Hahn, J.; Schmidtko, S.; Tuchen, F.P.; Kopte, R.; Kiko, R.; Bourlès, B.; Czeschel, R.; Dengler, M. Atlantic Equatorial Undercurrent intensification counteracts warming-induced deoxygenation. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seager, R.; Simpson, I.R. Western boundary currents and climate change. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 7212–7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lohmann, G.; Wei, W.; Dima, M.; Ionita, M.; Liu, J. Intensification and poleward shift of subtropical western boundary currents in a warming climate. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 4928–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Gupta, A.; Stellema, A.; Pontes, G.M.; Taschetto, A.S.; Vergés, A.; Rossi, V. Future changes to the upper ocean Western Boundary Currents across two generations of climate models. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hotspot | Min. Lon | Max. Lon | Min. Lat | Max. Lat | Min. Depth | Max. Depth | Mean Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34.50311794° W | 34.33045040° W | 7.105770018° S | 6.882931110° S | 131 | 266 | 198 |

| 2 | 35.56277799° W | 34.69037451° W | 5.215420883° S | 3.915738822° S | 131 | 222 | 167 |

| 3 | 35.95514930° W | 35.77659456° W | 3.874762168° S | 3.714923816° S | 156 | 186 | 163 |

| 4 | 39.97185287° W | 39.46325126° W | 2.251789859° S | 1.958868063° S | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 44.52622439° W | 44.36119833° W | 0.054347462° N | 0.244547919° N | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 44.87359625° W | 44.58225517° W | 0.296538033° N | 0.528225899° N | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 45.35399403° W | 45.31772390° W | 0.825741777° N | 0.841547764° N | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 46.83971696° W | 46.38451470° W | 1.452077887° N | 1.876376457° N | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 47.37466777° W | 46.93515169° W | 1.876413530° N | 2.295590423° N | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 47.71816236° W | 47.43446094° W | 2.322092614° N | 2.619202279° N | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 47.93009985° W | 47.82045592° W | 2.732593635° N | 2.845629499° N | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 48.09052323° W | 48.06963931° W | 2.987223703° N | 3.015971091° N | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hotspot | Min (W·m−2) | Max (W·m−2) | Mean (W·m−2) | Std (W·m−2) | Q1 (W·m−2) | Median (W·m−2) | Q3 (W·m−2) | IQR (W·m−2) | Whisker Low (W·m−2) | Whisker High (W·m−2) | N Outliers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 222 | 1720 | 845 | 223 | 688 | 831 | 991 | 303 | 244 | 1443 | 72 |

| 2 | 233 | 1877 | 826 | 231 | 662 | 808 | 968 | 306 | 233 | 1425 | 151 |

| 3 | 9 | 3175 | 1197 | 477 | 862 | 1211 | 1527 | 665 | 9 | 2524 | 37 |

| 4 | 3 | 5103 | 956 | 725 | 440 | 730 | 1287 | 848 | 3 | 2559 | 496 |

| 5 | 0 | 7425 | 1249 | 985 | 548 | 970 | 1661 | 1113 | 0 | 3330 | 569 |

| 6 | 1 | 5823 | 1114 | 859 | 505 | 886 | 1479 | 974 | 1 | 2938 | 534 |

| 7 | 0 | 6473 | 1125 | 894 | 486 | 885 | 1514 | 1028 | 0 | 3055 | 515 |

| 8 | 1 | 5807 | 1020 | 701 | 481 | 924 | 1415 | 934 | 1 | 2817 | 224 |

| 9 | 0 | 5802 | 998 | 700 | 442 | 931 | 1422 | 980 | 0 | 2891 | 170 |

| 10 | 0 | 6701 | 1202 | 906 | 451 | 1085 | 1770 | 1319 | 0 | 3733 | 127 |

| 11 | 0 | 6086 | 1193 | 964 | 378 | 1024 | 1799 | 1420 | 0 | 3922 | 136 |

| 12 | 0 | 6465 | 1224 | 1023 | 356 | 1014 | 1859 | 1503 | 0 | 4106 | 119 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lima, T.S.; Queiroz, S.; Américo Ishimaru, M.E.; Correia Lima, E.J.A.; Moura, M.d.C.; Araujo, M. Hotspots of Current Energy Potential in the Southwestern Tropical Atlantic. Energies 2026, 19, 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020329

Lima TS, Queiroz S, Américo Ishimaru ME, Correia Lima EJA, Moura MdC, Araujo M. Hotspots of Current Energy Potential in the Southwestern Tropical Atlantic. Energies. 2026; 19(2):329. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020329

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Tarsila Sousa, Syumara Queiroz, Maria Eduarda Américo Ishimaru, Eduardo José Araújo Correia Lima, Márcio das Chagas Moura, and Moacyr Araujo. 2026. "Hotspots of Current Energy Potential in the Southwestern Tropical Atlantic" Energies 19, no. 2: 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020329

APA StyleLima, T. S., Queiroz, S., Américo Ishimaru, M. E., Correia Lima, E. J. A., Moura, M. d. C., & Araujo, M. (2026). Hotspots of Current Energy Potential in the Southwestern Tropical Atlantic. Energies, 19(2), 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020329