Effects of Pulsating Wind-Induced Loads on the Chaos Behavior of a Dish Concentrating Solar Thermal Power System

Abstract

1. Introduction

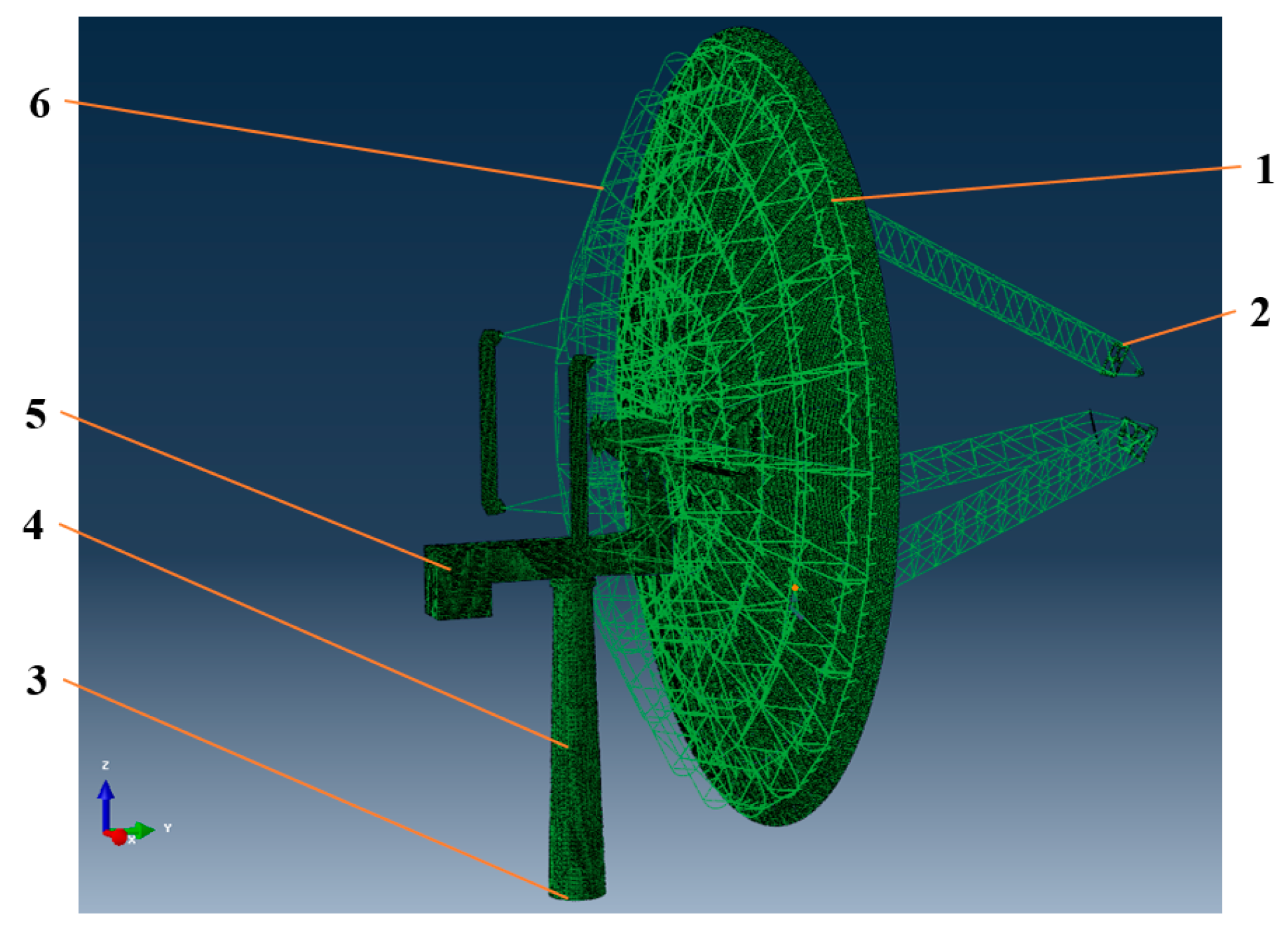

2. Simulation Model and Its Verification

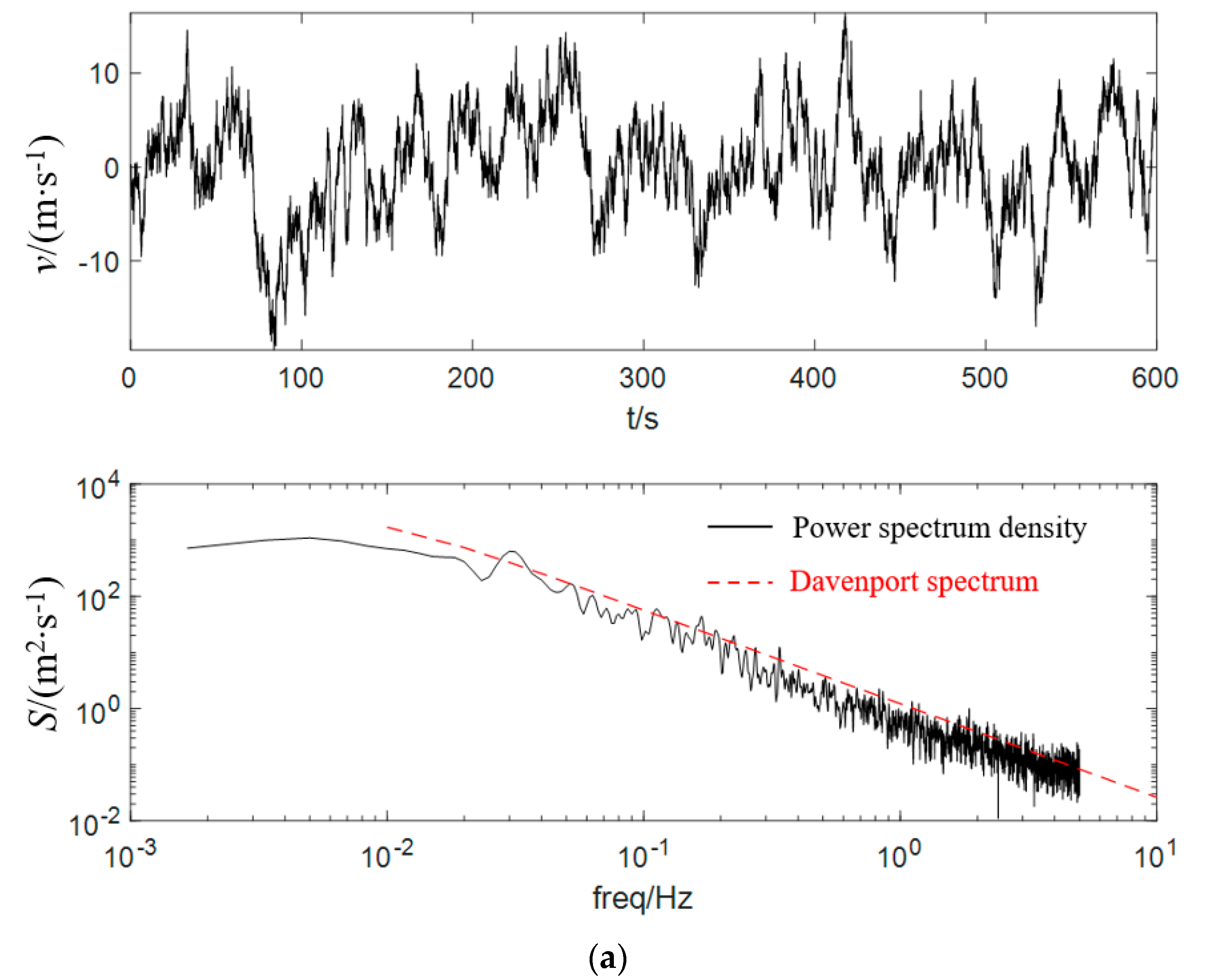

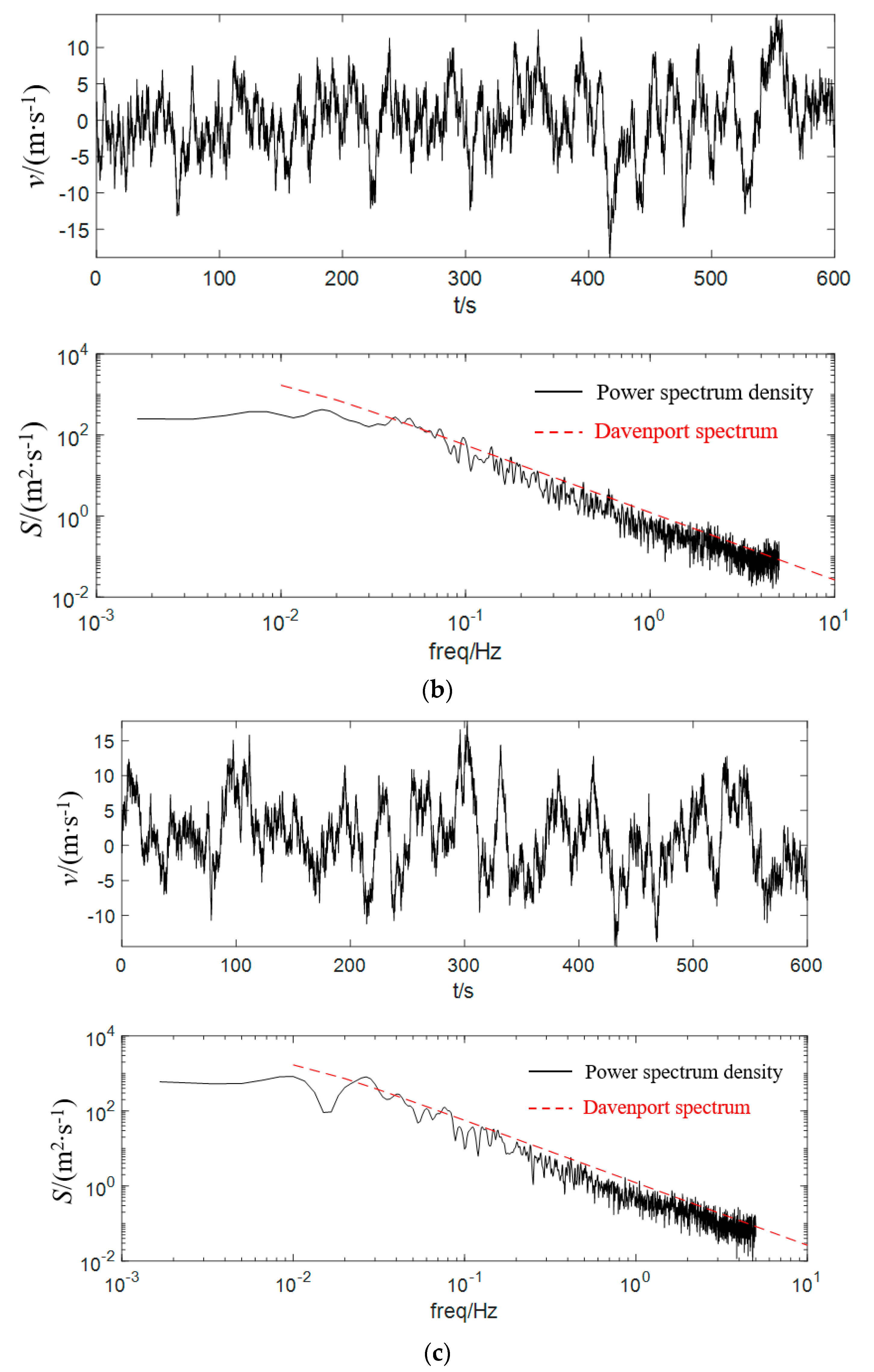

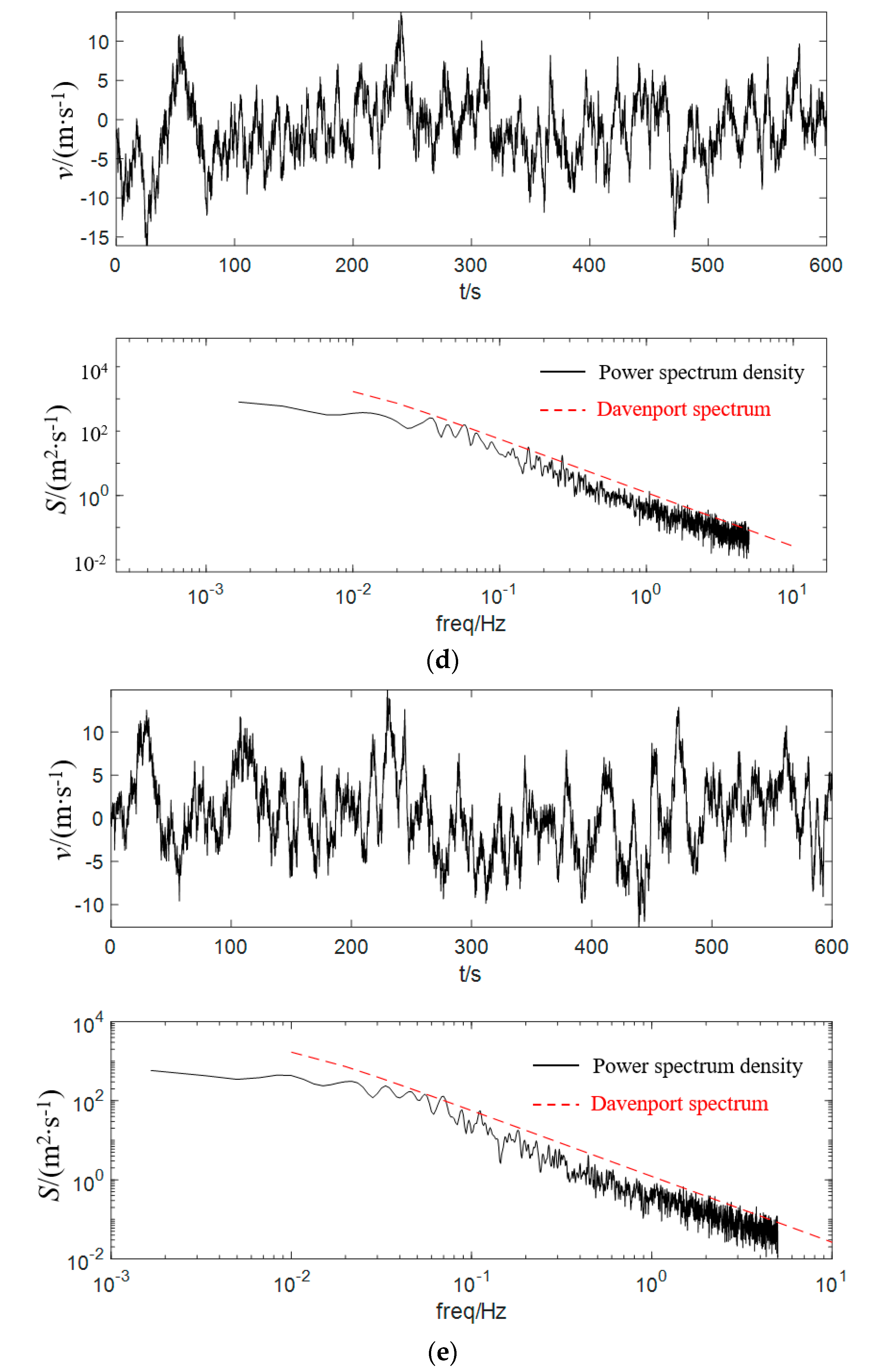

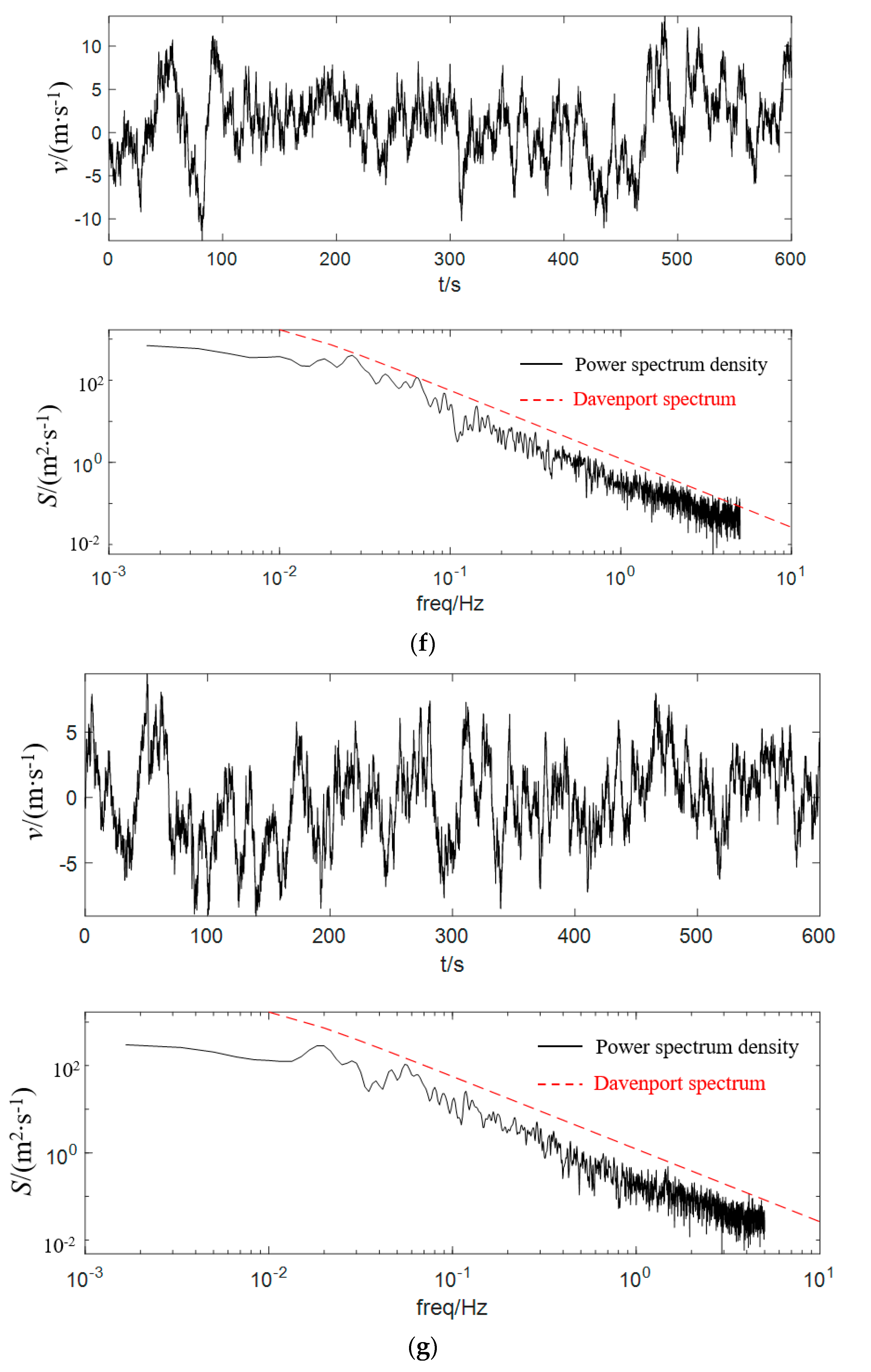

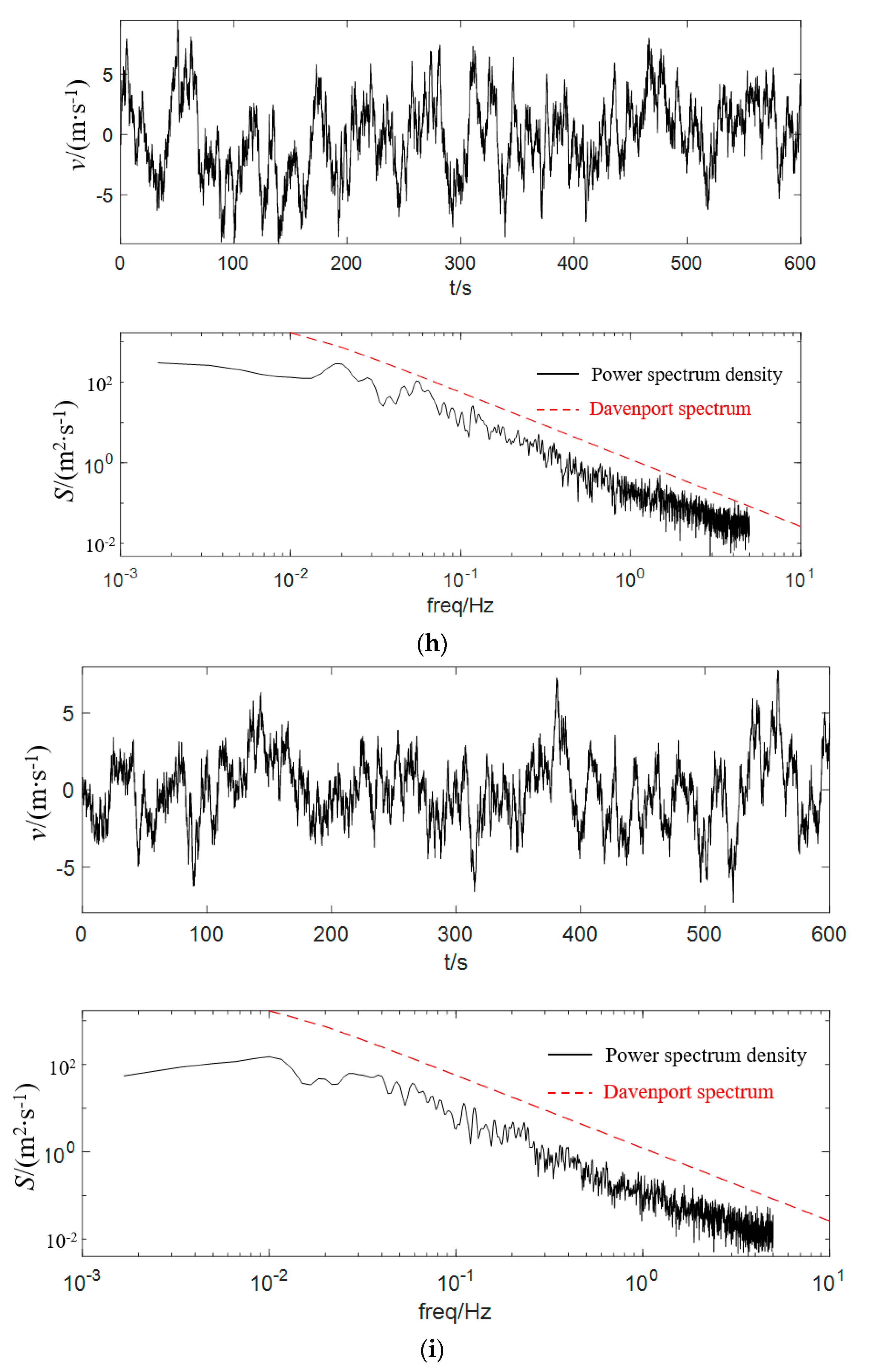

2.1. Pulsating Wind Speed Spectrum

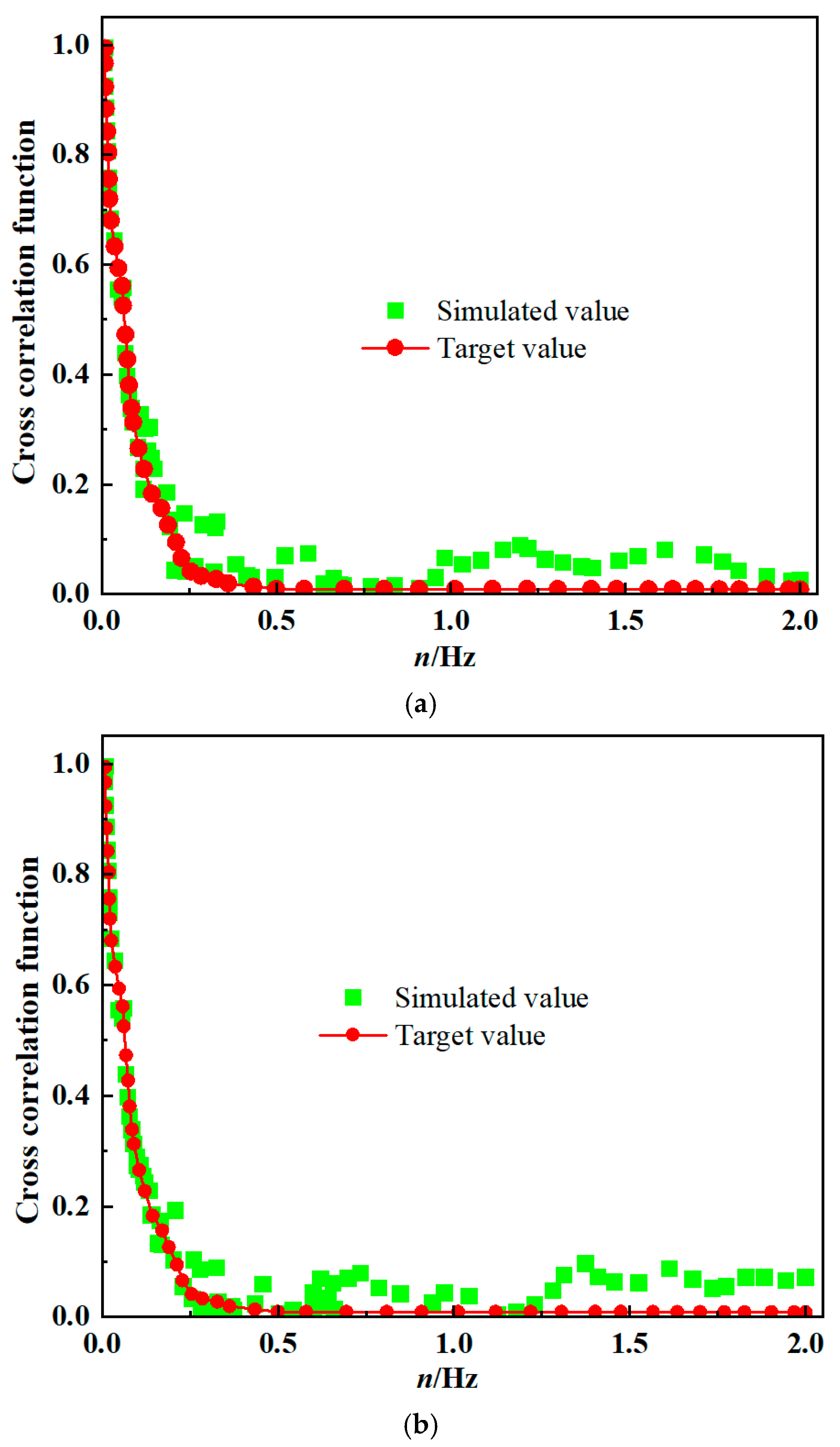

2.2. Simulation of Pulsating Wind Based on Autoregressive Method and Development of User-Defined Function

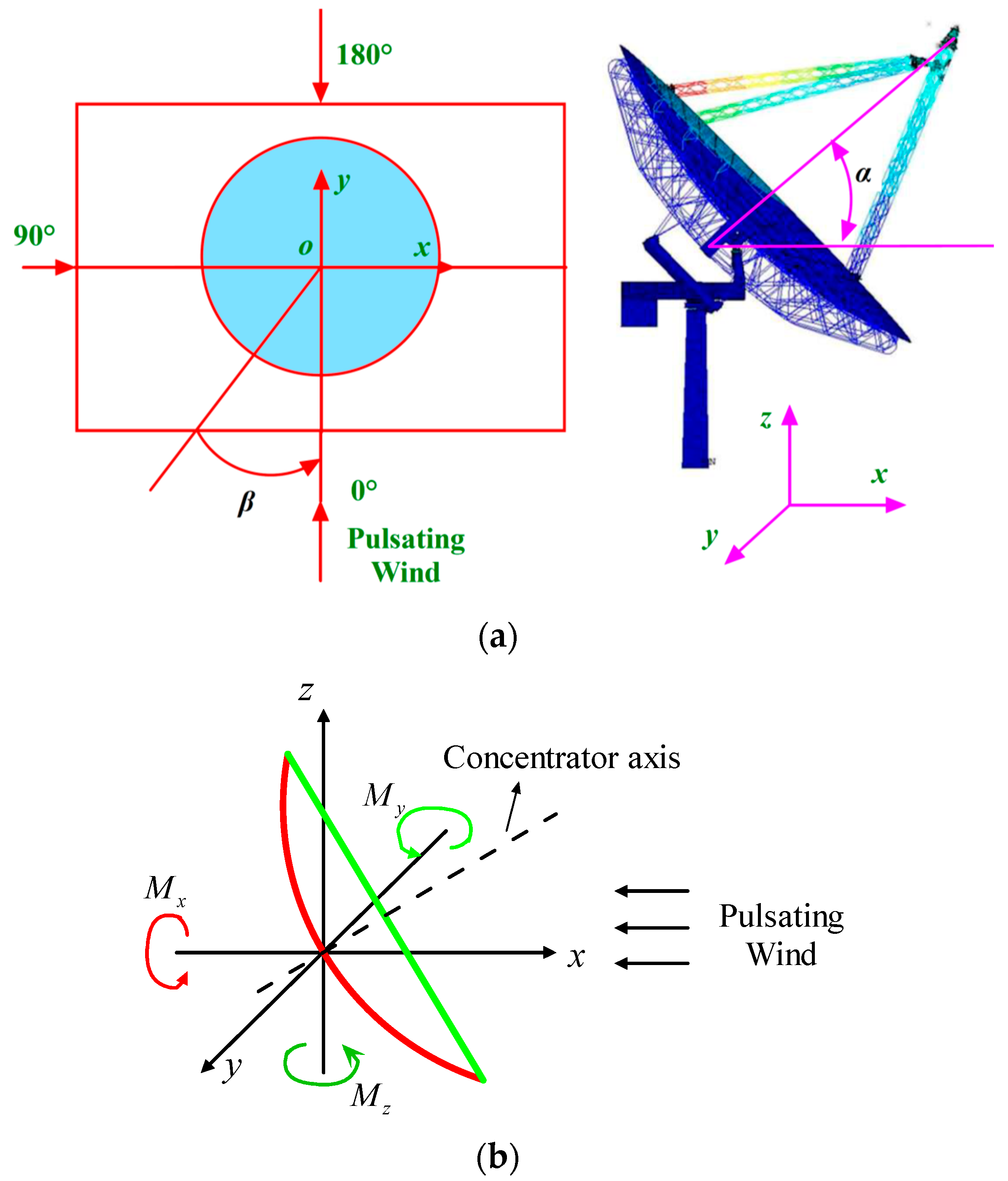

2.3. Wind-Induced Vibration Characteristic Parameters

- (1)

- Wind coefficient

- (2)

- Wind moment coefficient

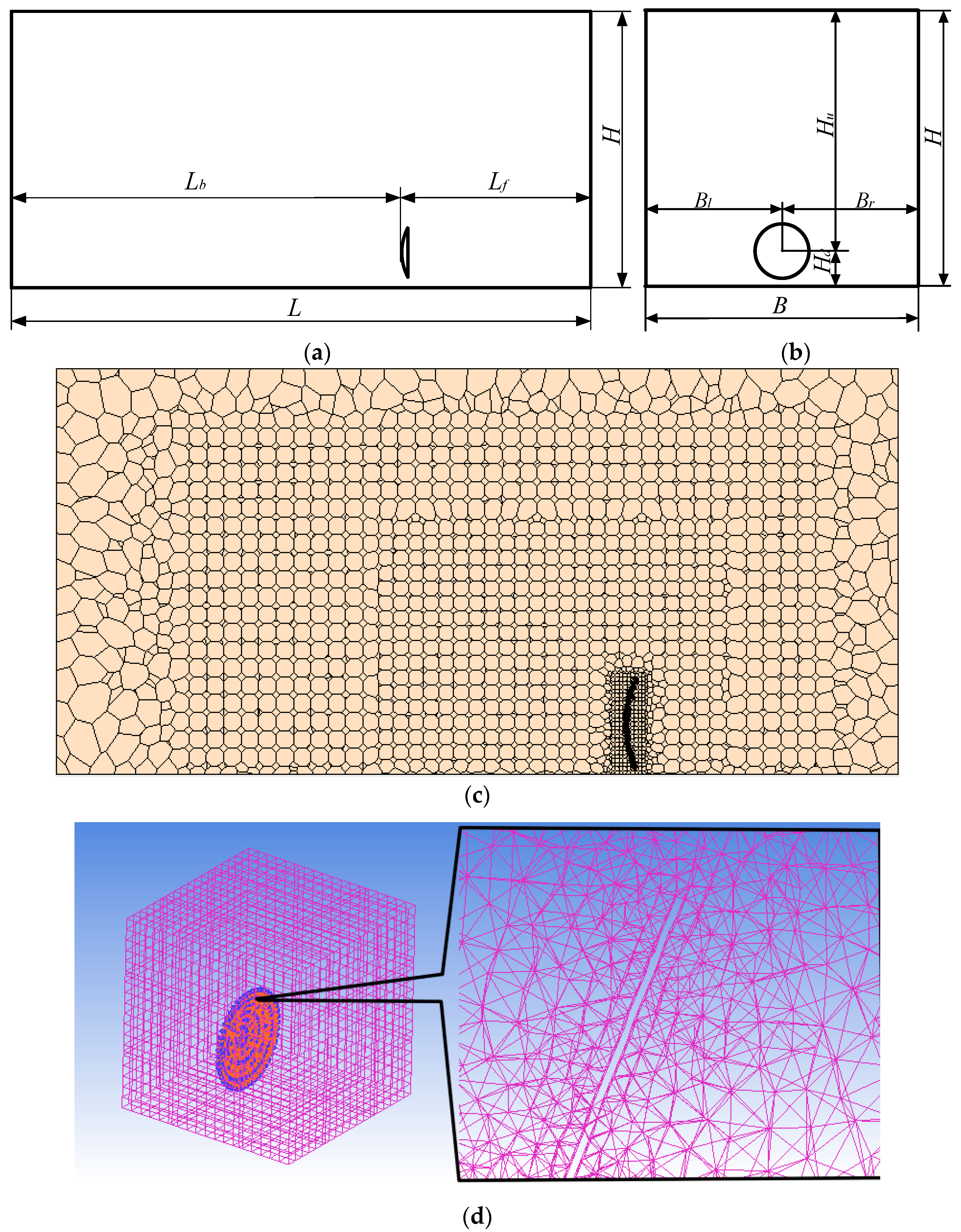

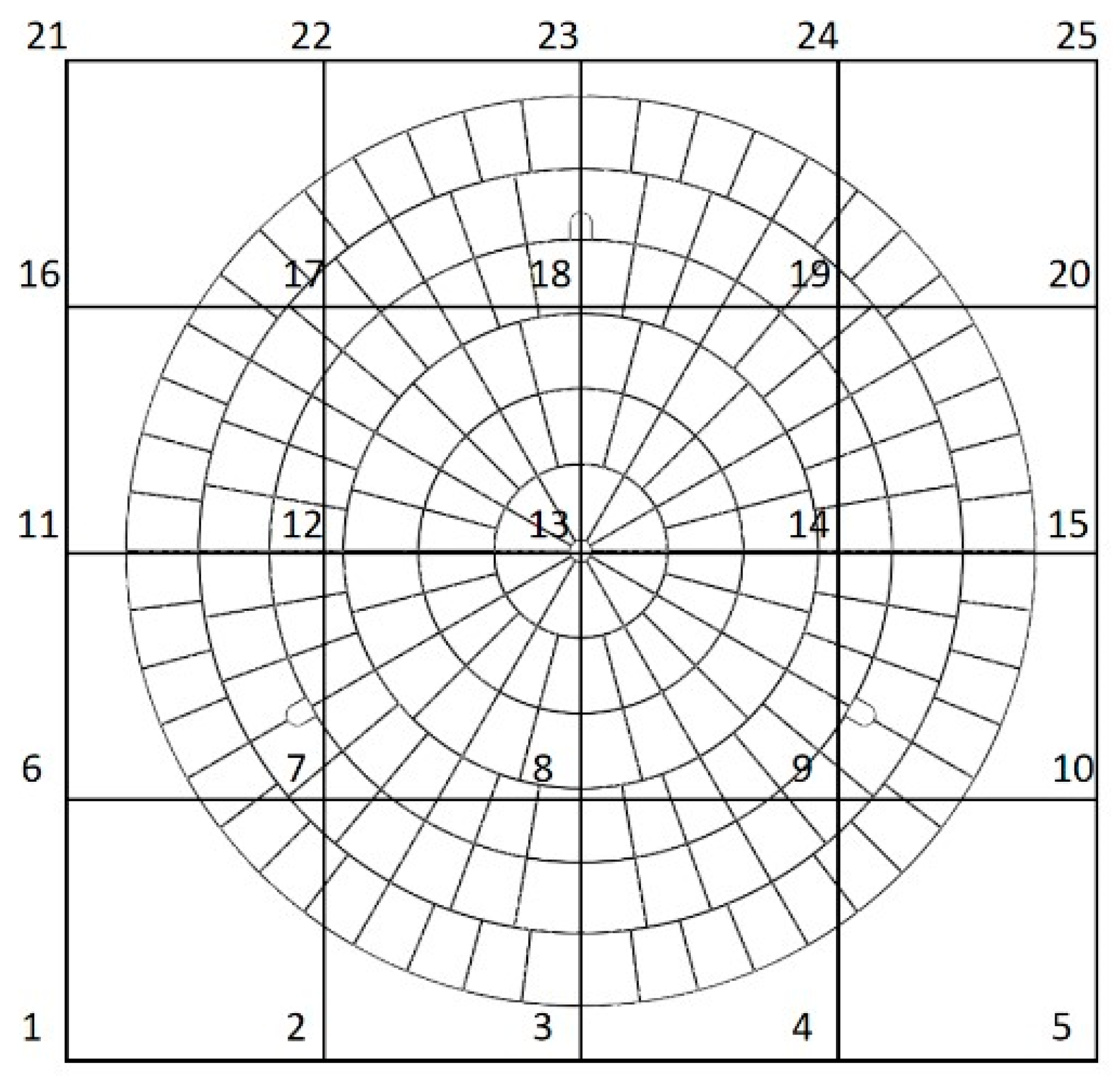

2.4. Fluid Domain Mesh Division of the Dish Concentrating Solar Thermal Power System

2.5. Fluid Domain Simulation Condition Settings

- (1)

- Inlet boundary conditions: The fluid flow in this area is incompressible, and the inlet wind speed is simulated using a pulsating wind simulation program developed on the MATLAB platform. A UDF program for Fluent has also been developed.

- (2)

- Outlet boundary conditions: At the outlet, a pressure outlet boundary condition is adopted, with a pressure of one standard atmospheric pressure.

- (3)

- Wall conditions: The roughness of the fluid domain surface and the condenser surface is set to be smooth. The velocity on the non-slip wall is zero, and the fluid velocity at the wall is zero. The surface and ground of the concentrator adopt non-slip wall conditions. Sliding boundary conditions are adopted at the top, front, and back of the fluid domain.

2.6. Pulsating Wind Simulation Verification of the Dish Concentrating Solar Thermal Power System

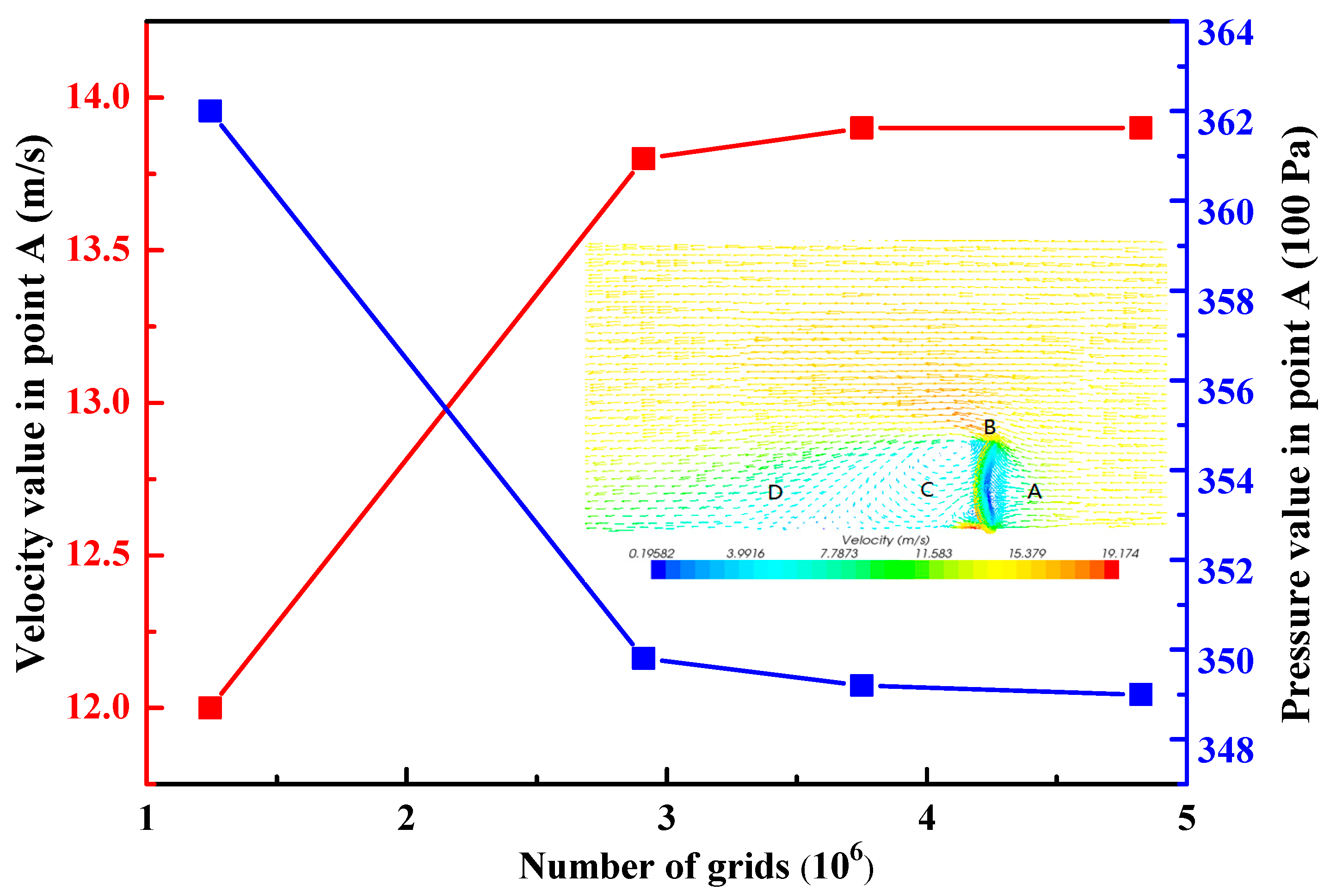

2.7. Verification of the Grid Independence

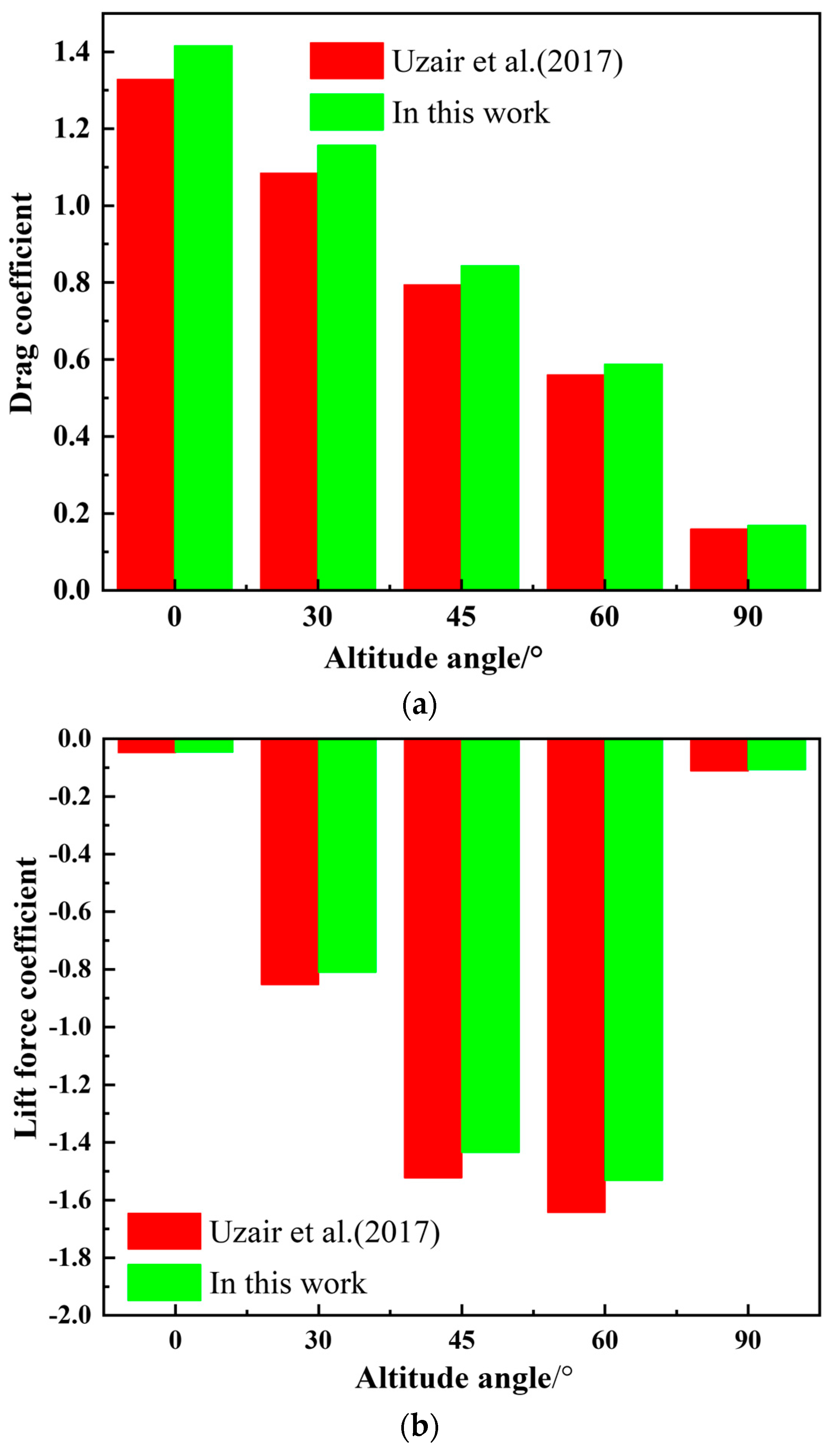

2.8. Verification of the Simulation Model

3. Analysis and Discussion

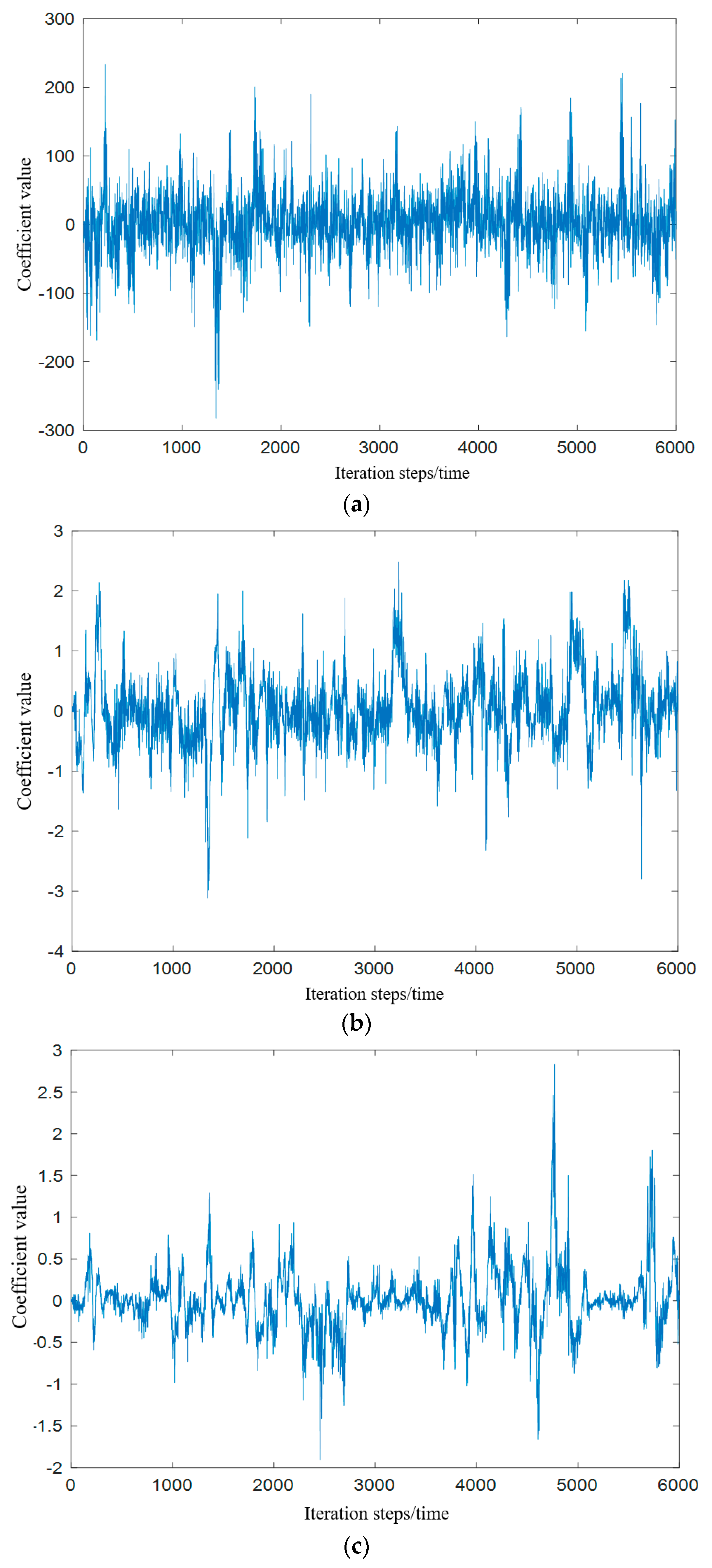

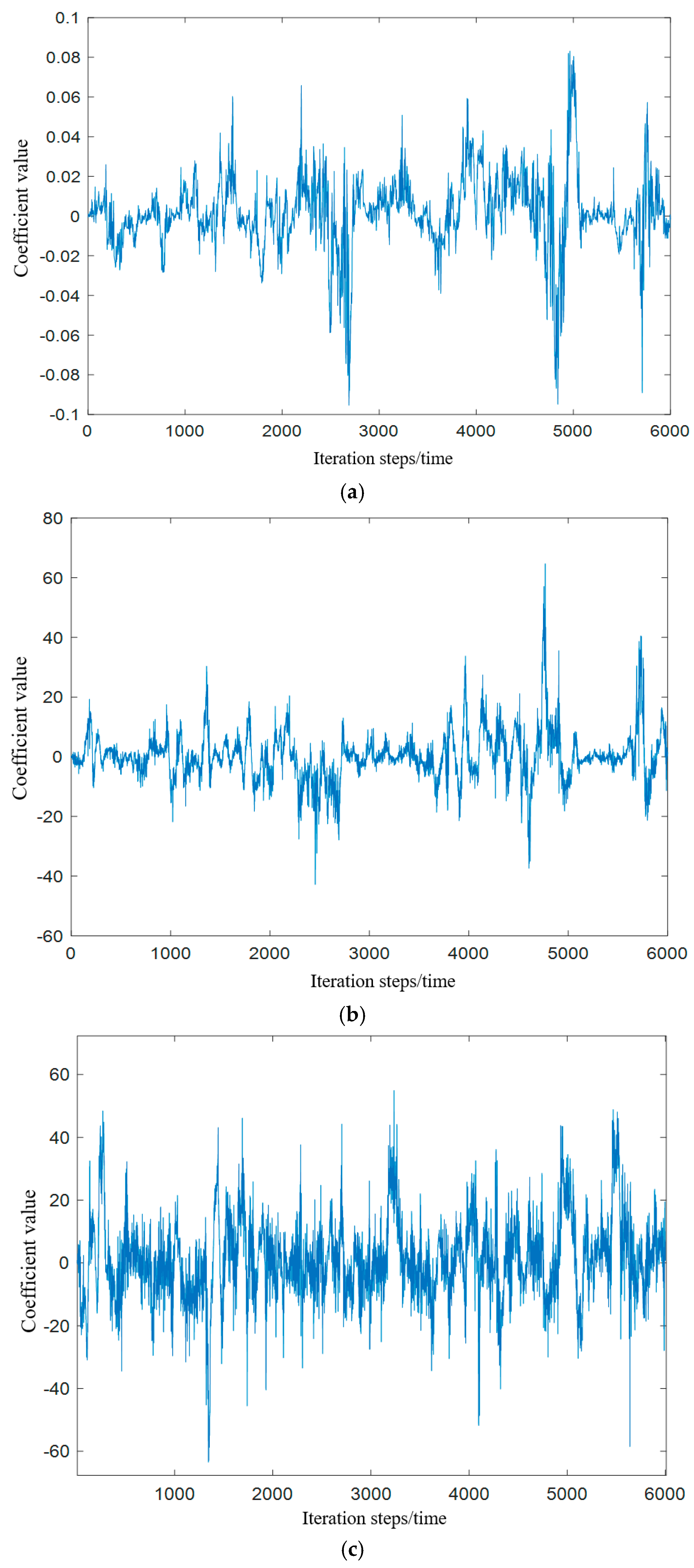

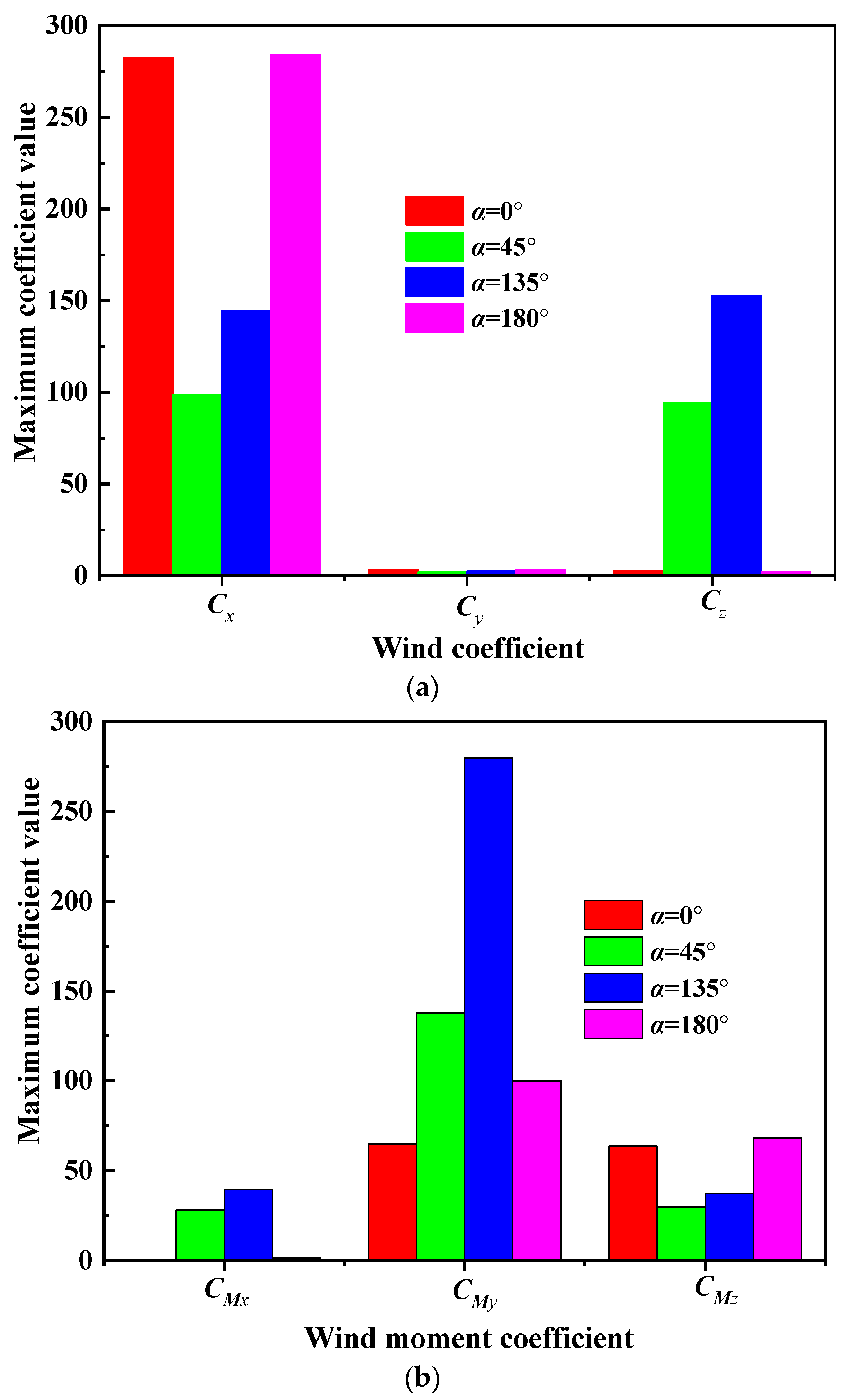

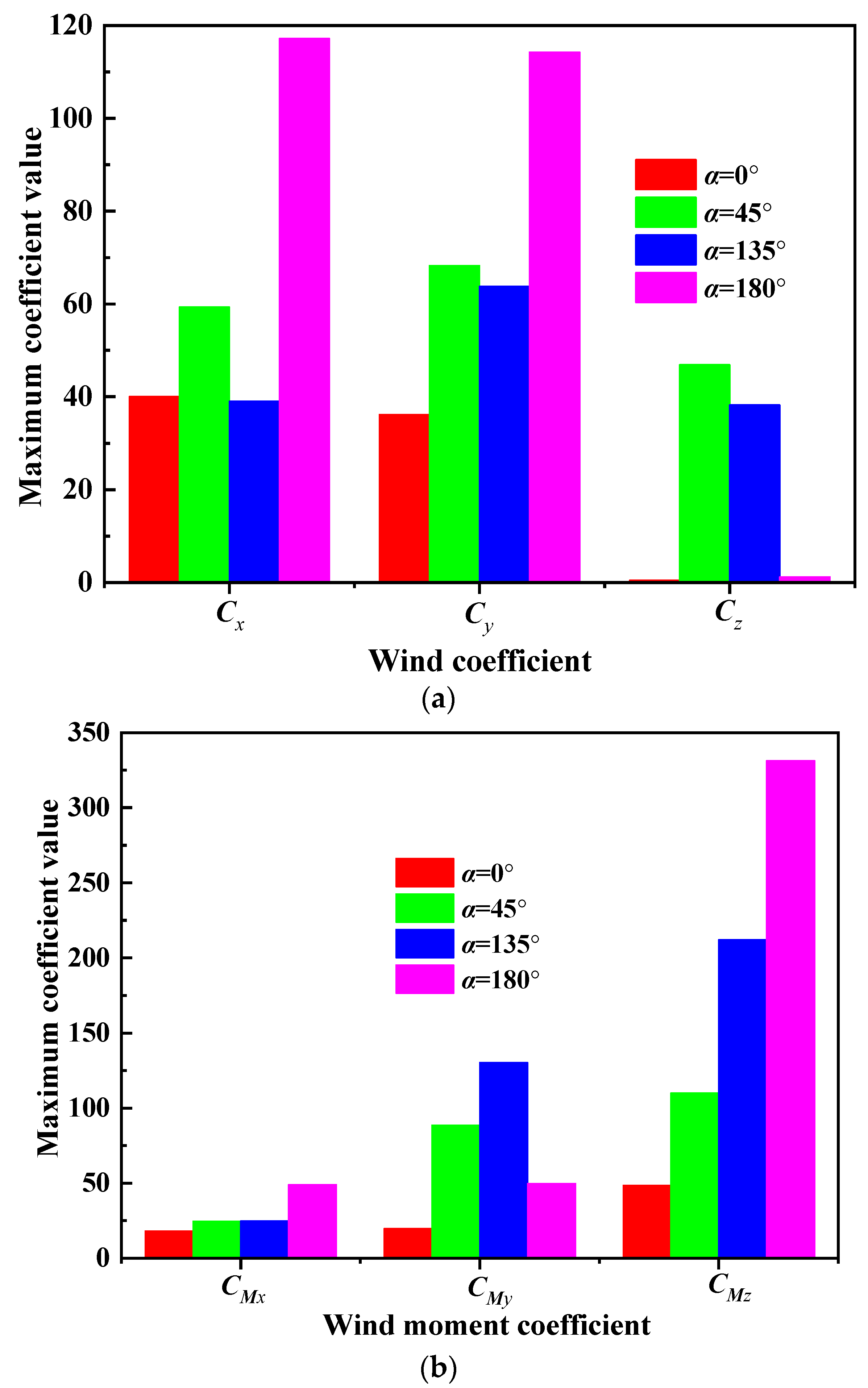

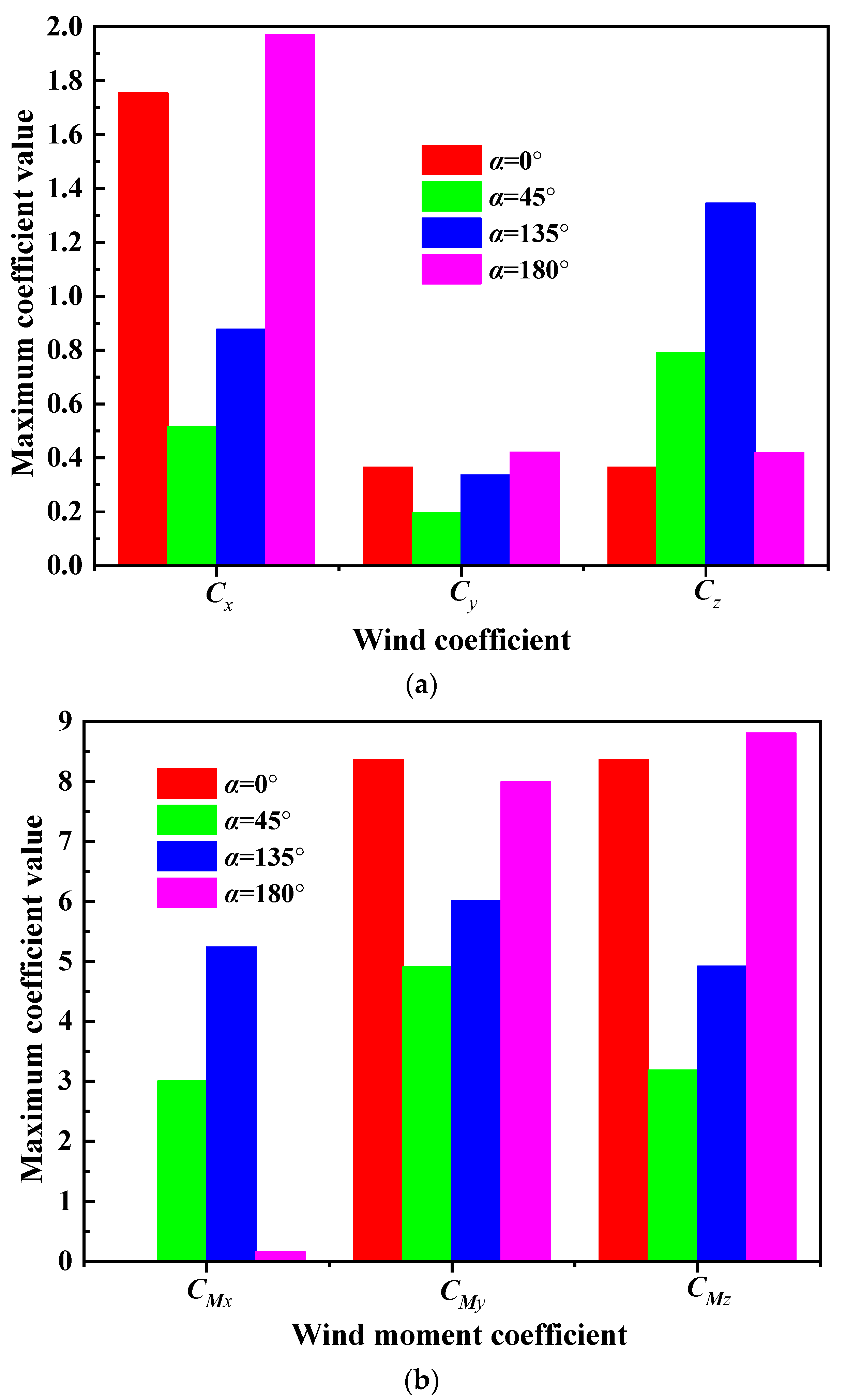

3.1. Effects of Pulsating Wind Action on Wind Force Coefficient and Wind Moment Coefficient

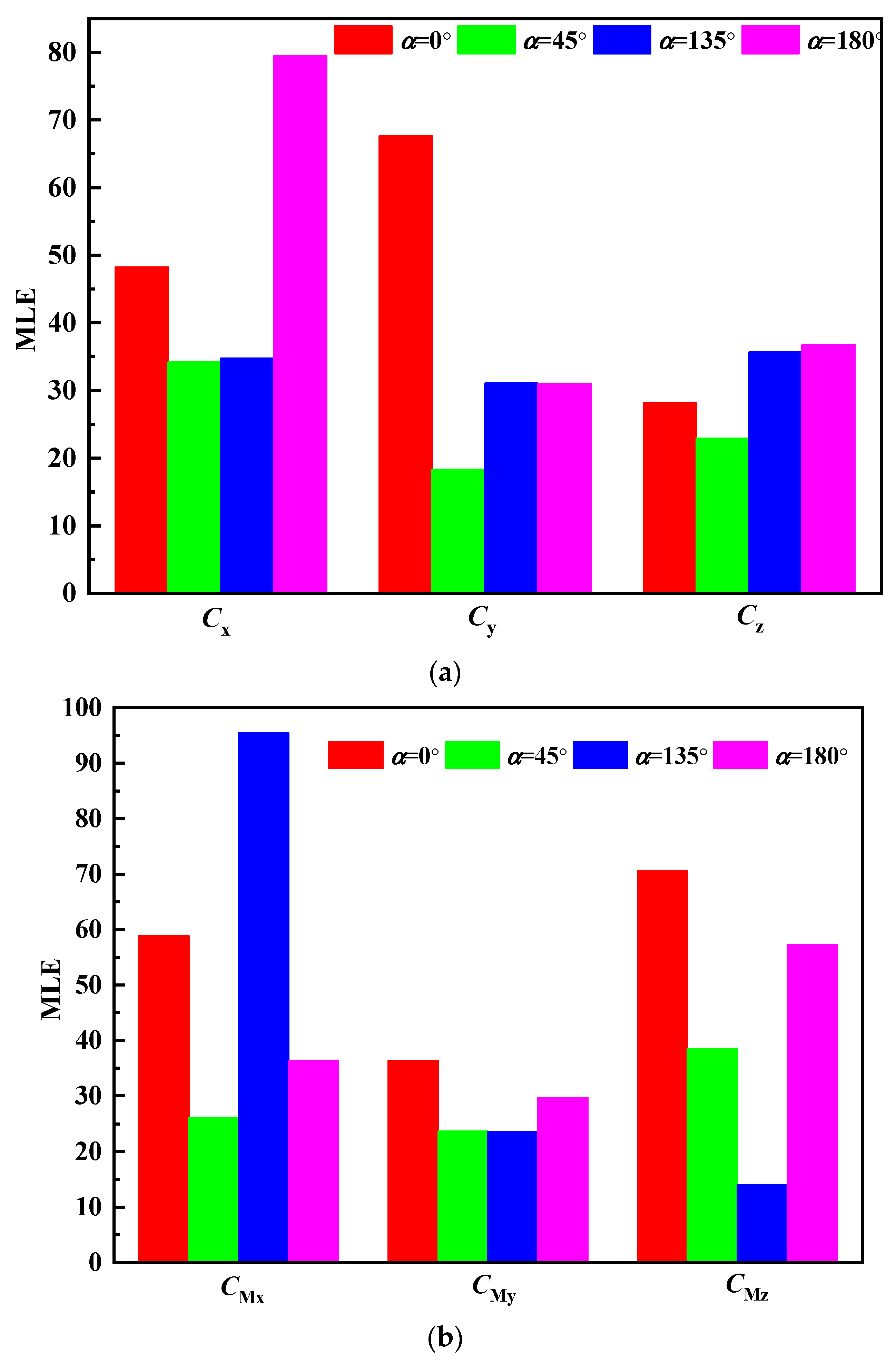

- (1)

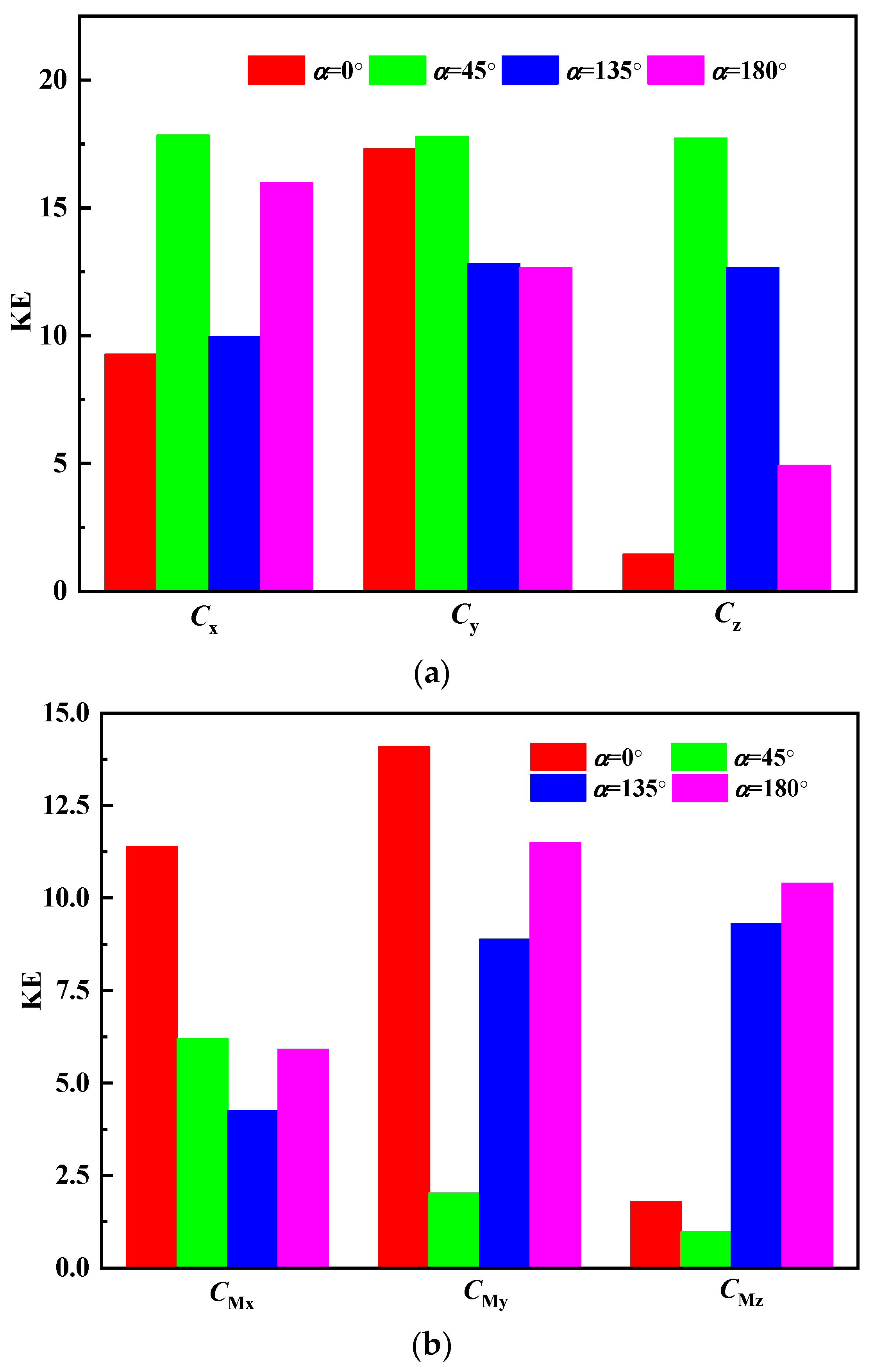

- For azimuth angle β = 0°, the maximum values of the lateral force coefficient Cy remain basically unchanged at different altitude angles. When the altitude angles are 0° and 180°, the drag coefficient Cx, lateral force coefficient Cy, and lift force coefficient Cz are of approximately equal maximum values, and the lift force coefficient Cz and drag coefficient Cx are close to each other when the altitude angles are 45° and 135°. And the maximum pitch moment coefficient CMy changes most significantly at different altitude angles, while the maximum pitch moment coefficient CMy at altitude angles of 45° or 135° is significantly greater than the maximum pitch moment coefficients at altitude angles of 0° and 180°.

- (2)

- For azimuth angle β = 45°, the drag coefficient, lateral force coefficient, and lift force coefficient are of approximately equal maximum values when the altitude angles are 45° and 135°. When the altitude angles are 0° and 180°, the lift force coefficient is close to 0, and the maximum pitch moment coefficients are also significantly smaller than the maximum pitch moment coefficients altitude angles of 45° and 135°.

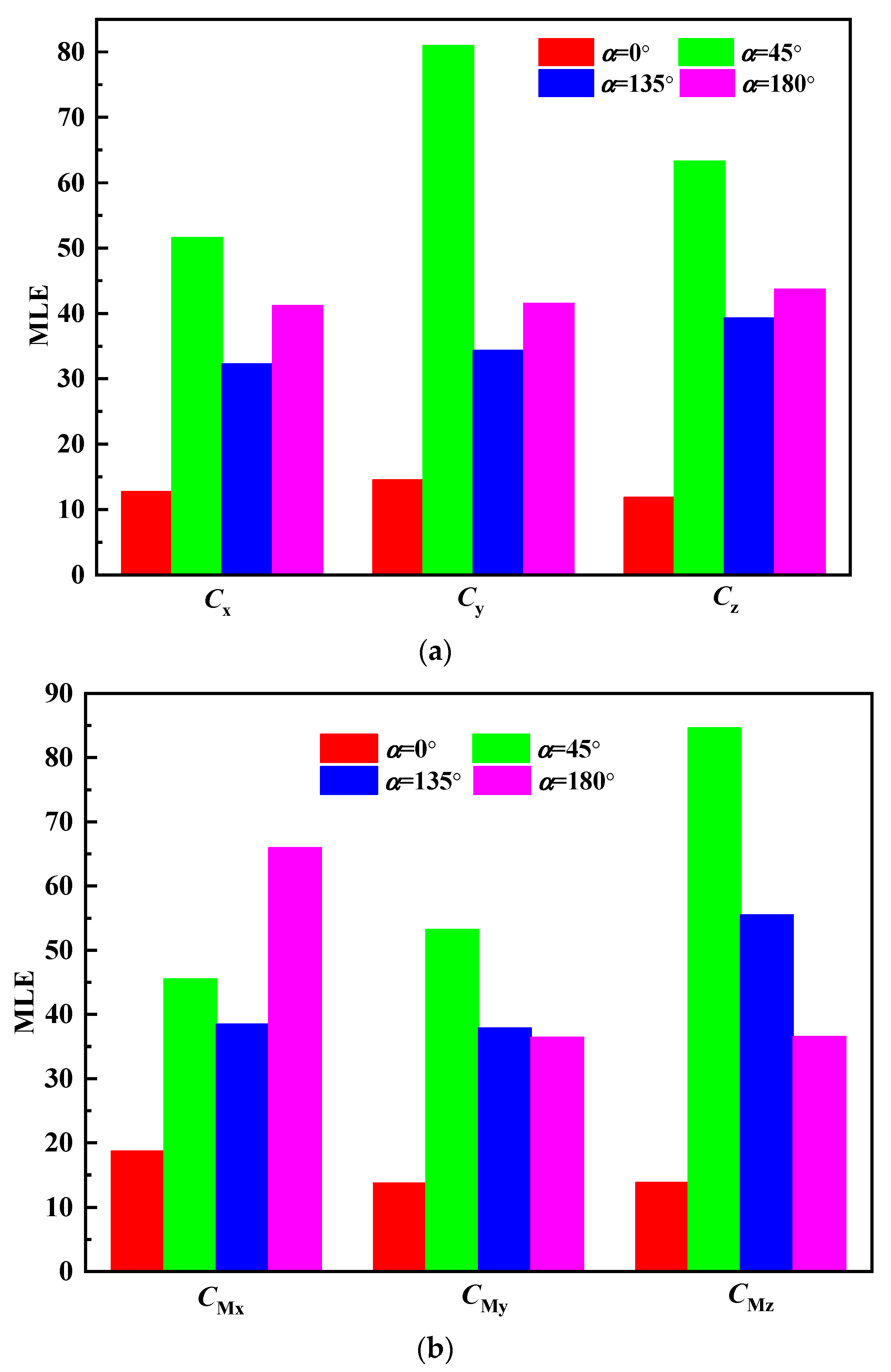

- (1)

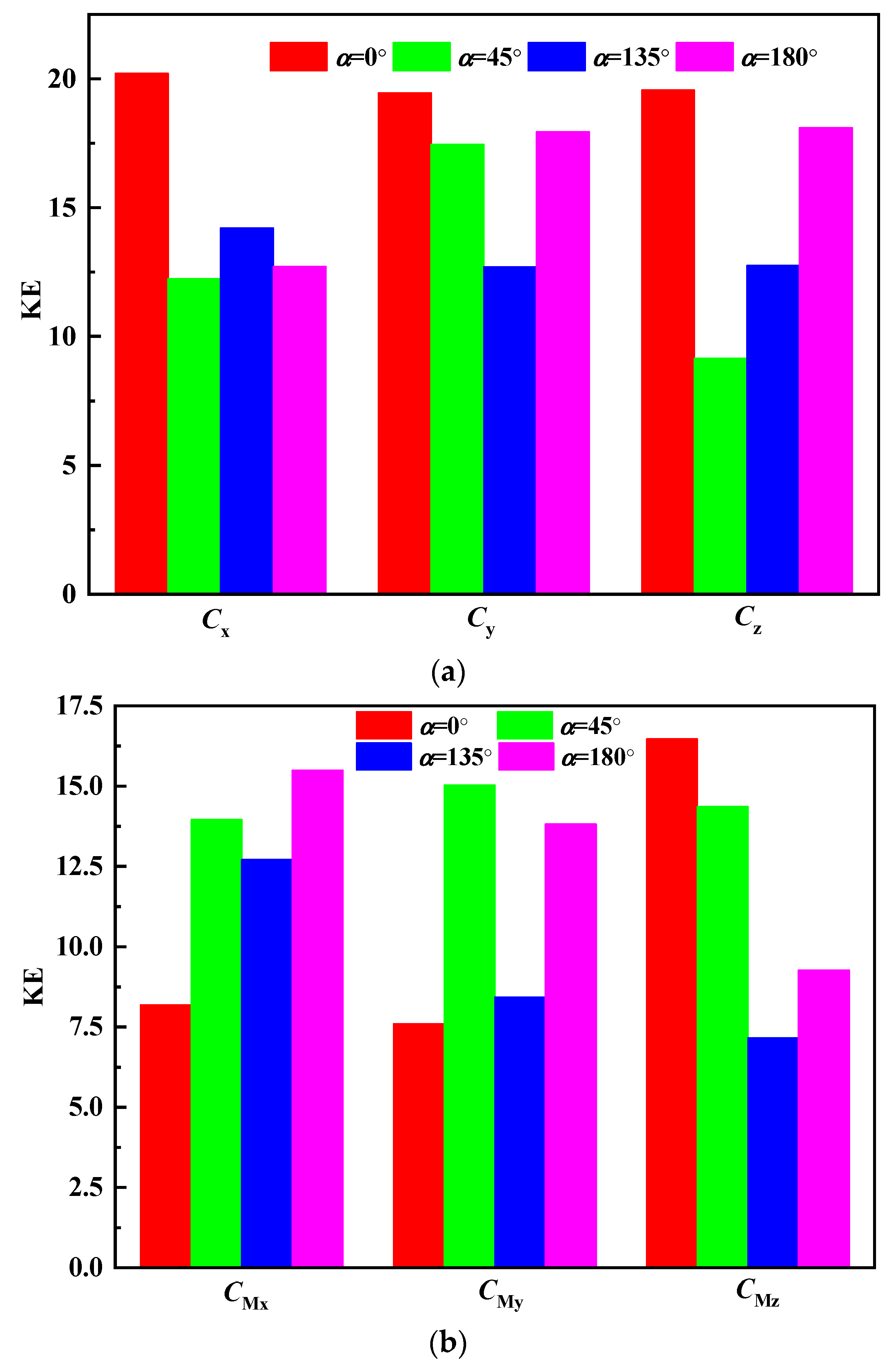

- For azimuth angle β = 0°, the maximum lateral force coefficient Cy at different altitude angles is of the smallest value among the coefficients, and the change in the altitude angle has a relatively small impact on the maximum lateral force coefficient Cy. When the altitude angle is 0° or 180°, the drag coefficient Cx, lateral force coefficient Cy, and lift force coefficient Cz of the DCSTPS are of approximately equal maximum values. And the maximum drag coefficient will decrease, while the maximum lift force coefficient of the DCSTPS will increase when the altitude angle is 45° and 135°, respectively.

- (2)

- When the altitude angles are 0° and 180°, the maximum roll moment coefficients are also significantly smaller than the maximum roll moment coefficient altitude angles of 45° and 135°, but the maximum pitch moment coefficient and maximum azimuth moment coefficient are significantly greater than the maximum roll moment coefficient altitude angles of 45° and 135°.

3.2. Chaos Behavior of Wind-Induced Vibration Characteristic of a Dish Solar Thermal Power System

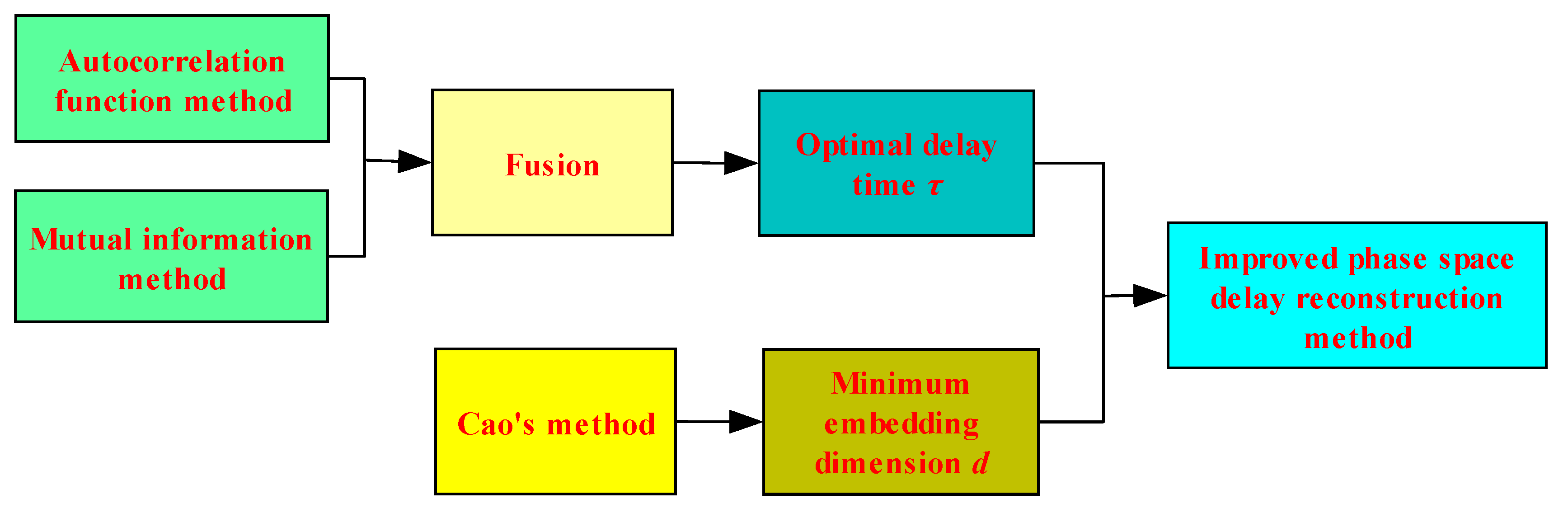

3.2.1. Improvement and Verification of Phase Space Delay Reconstruction Method

- (1)

- Steps of phase space delay reconstruction method

- (2)

- Improved phase space delay reconstruction method

- (a)

- Characteristics of the time series: If the time series is of strong nonlinear and chaotic characteristics, a mutual information method is more effective in this case because it can capture nonlinear relationships. At the same time, the mutual information method is usually more sensitive to nonlinear and complex systems than the autocorrelation method, and a higher proportion of mutual information method should be given. On the contrary, if the time series is linear or is of obvious periodicity, a higher proportion of the autocorrelation method should be given.

- (b)

- Noise level: In situations with high noise levels, the mutual information method may be more robust, so its proportion increase should be considered.

- (c)

- Expert experience: In the absence of clear guidance, the experience and intuition of experts are also important factors in determining the different weights w1 and w2 to the two delay times τ1 and τ2. Experts can propose reasonable weighting suggestions based on their understanding of data characteristics and analysis objectives.

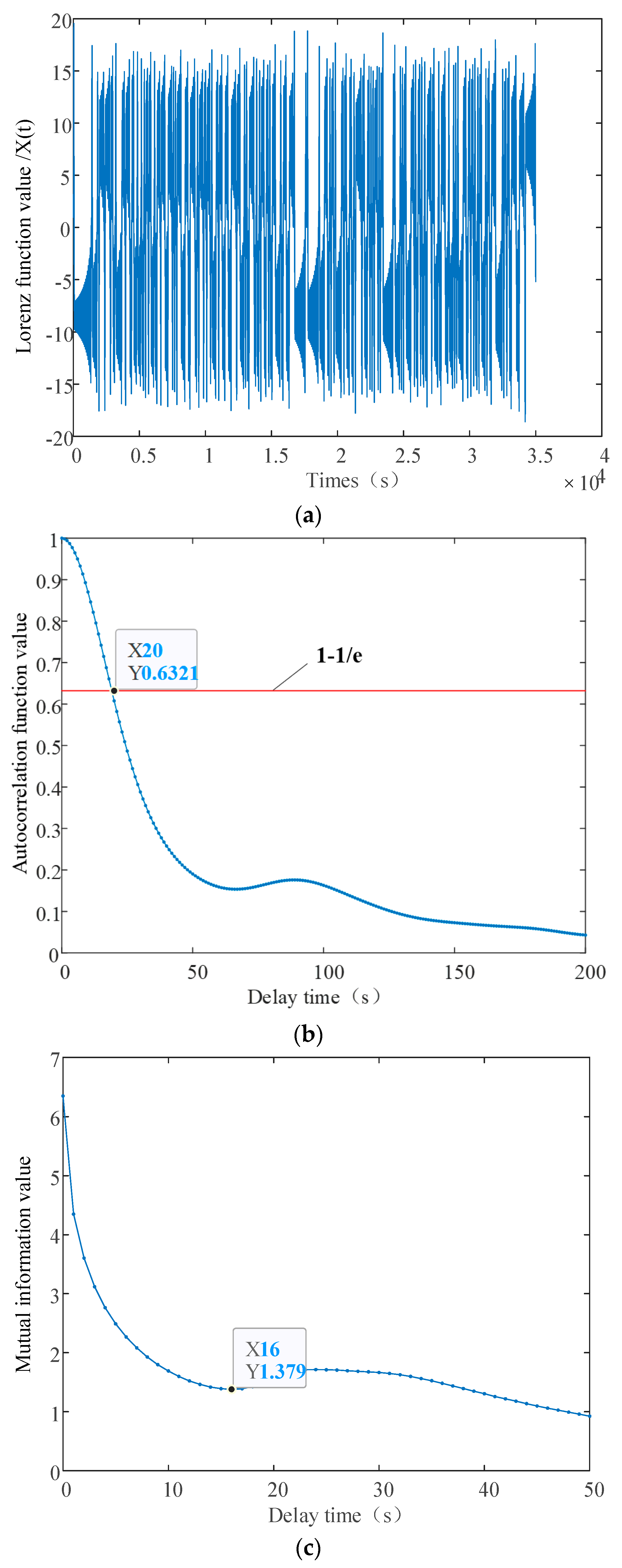

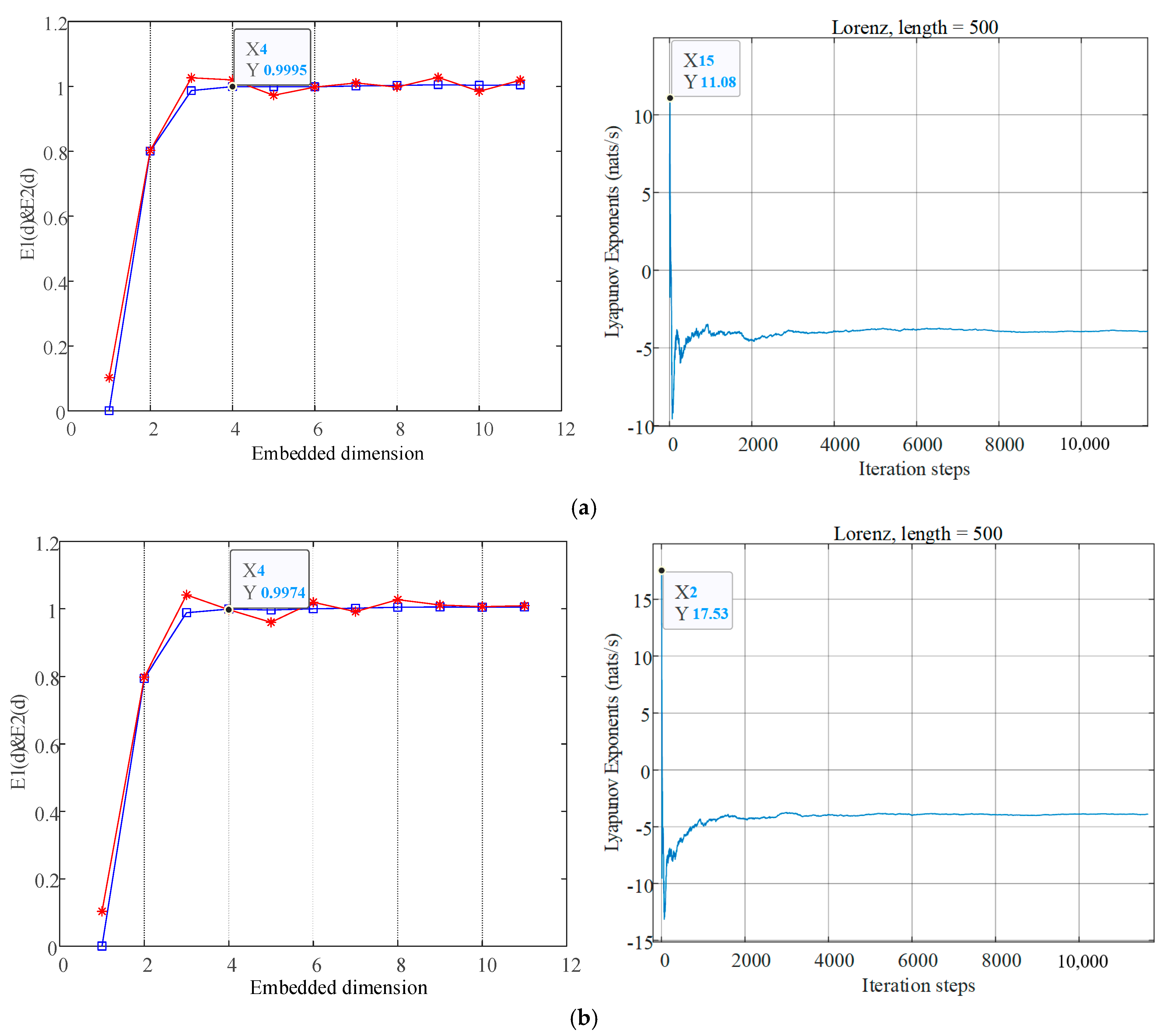

- (3)

- Verification of the improved phase space delay reconstruction method

3.2.2. Chaos Behavior of the Wind Vibration Characteristic Parameters of a Dish Solar Thermal Power System

- (1)

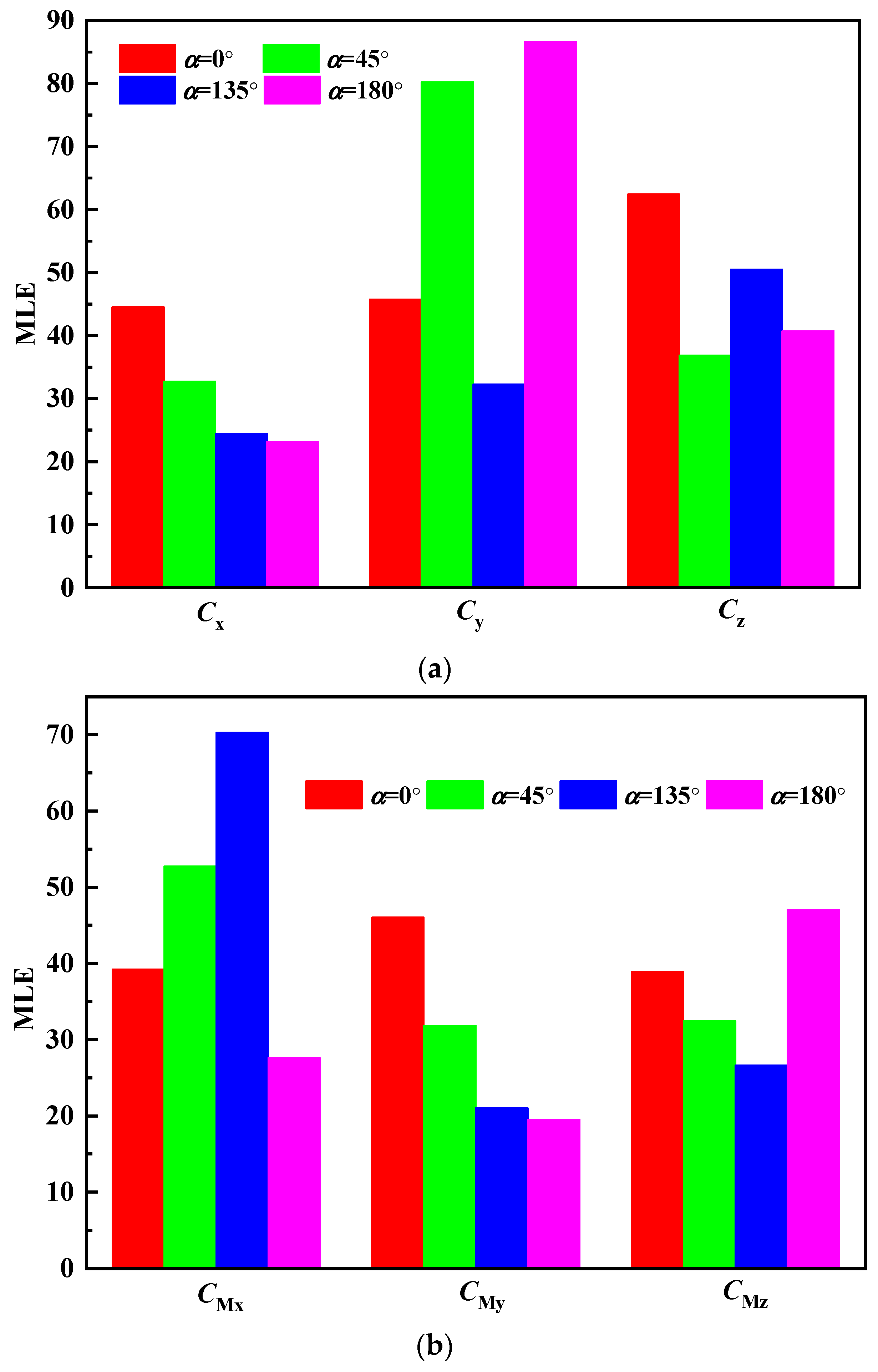

- Chaos behavior of wind vibration characteristic parameters based on Lyapunov exponent.

- (2)

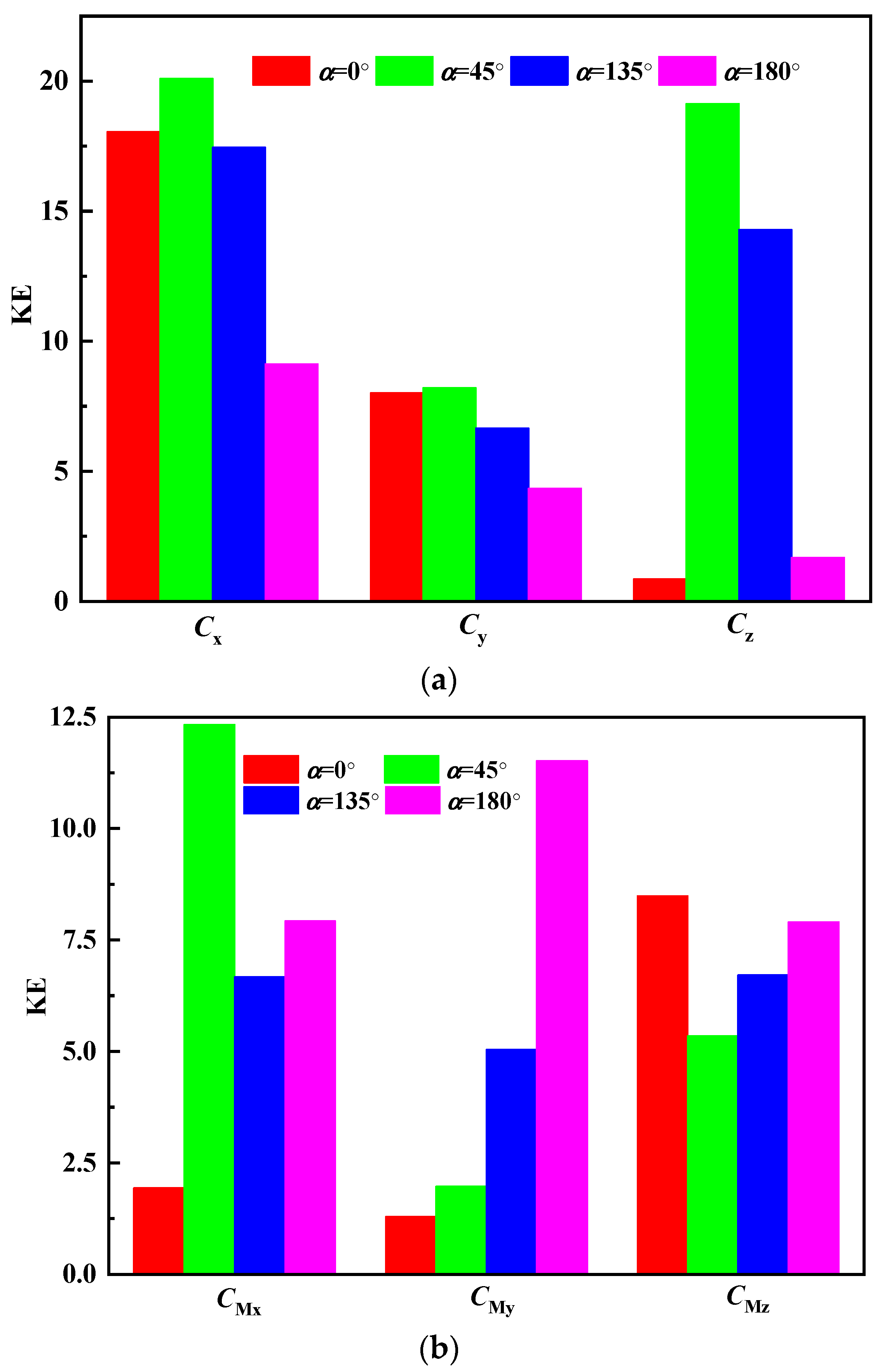

- Chaos behavior of wind vibration characteristic parameters based on Kolmogorov entropy.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

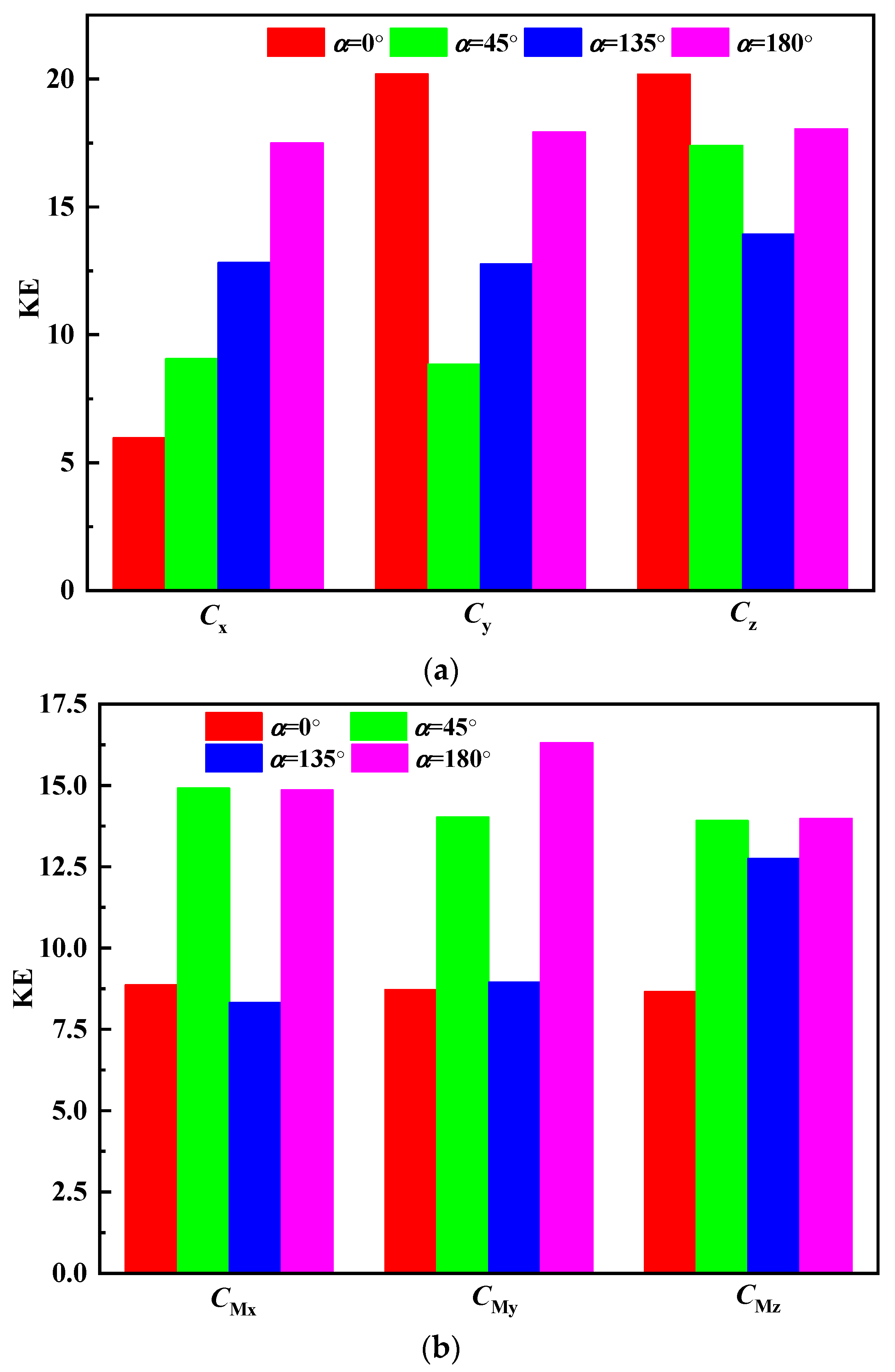

- Under the pulsating wind action, the maximum values of the wind coefficient- and wind moment coefficient-related components of the DCSTPS are affected by changes in the altitude angle and azimuth angle during the pulsating wind action time. The law is similar to the changes under stable wind action; that is, for the DCSTPS, increases in its altitude angle leads to a reduction in its drag coefficient and increase in its lift force coefficient, and the pitch moment increases with an increase in the altitude angle. Moreover, the drag coefficient Cx1, the pitch moment coefficient CMy1, and the azimuth moment coefficient CMz1 under β = 0° are much greater than the drag coefficient Cx2, the pitch moment coefficient CMy2, and the azimuth moment coefficient CMz2 under β = 45°, respectively. And maximum rate of their change is −364%, −524%, and −432%, respectively.

- (2)

- The time history data of the relevant wind vibration coefficient shows irregular changes under the action of pulsating wind. And by using an improved phase space delay reconstruction method to calculate the delay time, the maximum Lyapunov exponent and Kolmogorov entropy of the DCSTPS are greater than zero under the action of pulsating wind. With an increase in the maximum Lyapunov exponent and Kolmogorov entropy of the DCSTPS under the action of pulsating wind, the divergence speed of the DCSTPS trajectory will accelerate, and the time for the system to enter the chaotic state will be shortened.

- (3)

- The DCSTPS will enter a chaotic state under the action of pulsating wind, and the time of entering the chaotic state and the degree of subsequent chaotic states will be significantly affected by the relevant wind vibration coefficients, but without regularity. In future research, the challenge is to elucidate the catastrophic physical essence of the chaotic behavior of the DCSTPS under pulsating wind-induced loads and explore how to reduce or control nonlinear effects through design optimization of the DCSTPS.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DCSTPS | Dish concentrating solar thermal power system |

| UDF | User-defined function |

| AR | Autoregressive |

| DSC | Dish solar concentrator |

| KE | Kolmogorov entropy |

| MLE | Maximum Lyapunov exponent |

References

- Ramanan, C.J.; King, H.L.; Jundika, C.K.; Sukanta, R.; Bhaskor, J.B.; Bhaskar, J.M. Towards sustainable power generation: Recent advancements in floating photovoltaic technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 194, 114322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, X.; Sun, X.; Qin, M.; Pan, R.; Yang, Y. The diffusion path of distributed photovoltaic power generation technology driven by individual behavior. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 651–658. [Google Scholar]

- Bayon, A.; Bader, R.; Jafarian, M.; Fedunik-Hofman, L.; Sun, Y.; Hinkley, J.; Miller, S.; Lipiński, W. Techno-economic assessment of solid–gas thermochemical energy storage systems for solar thermal power applications. Energy 2018, 149, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K.; Iverson, B.D. Review of high-temperature central receiver designs for concentrating solar power. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Haussener, S. Radiative transfer in luminescent solar concentrators. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2024, 319, 108957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, W.; Abbasi-Shavazi, E.; Chen, J.; Coventry, J.; Hangi, M.; Iyer, S.; Kumar, A.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Pye, J.; et al. Progress in heat transfer research for high-temperature solar thermal applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 184, 116137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lipiński, W.; Pye, J. A method for in situ measurement of directional and spatial radiosity distributions from complex-shaped solar thermal receivers. Sol. Energy 2020, 201, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, K.K.; Krishna, C.N.V.V.; Sendhil, K.N. Solar thermal energy technologies and its applications for process heating and power generation—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 125296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K. A review of high-temperature particle receivers for concentrating solar power. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 109, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, R.; González-Aguilar, J.; Merrouni, A.A.; Romero, M. Soiling effect in solar energy conversion systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Garcia, F.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, J.; Tamayo-Pacheco, S.; Olalde, G.; Romero, M. Numerical Analysis of Radiation Attenuation in Volumetric Solar Receivers Composed of a Stack of Thin Monolith Layers. Energy Procedia 2014, 57, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Aziz, M.T.; Alauddin, M.; Kader, Z.; Islam, M.R. Site suitability assessment for solar power plants in Bangladesh: A GIS-based analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) approach. Renew. Energy 2024, 220, 119595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylili, A.; Fokaides, P.A.; Ioannides, A.; Kalogirou, S. Environmental assessment of solar thermal systems for the industrial sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K. Advances in central receivers for concentrating solar applications. Sol. Energy 2017, 152, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K.; Khalsa, S.S.; Kolb, G.J. Methods for probabilistic modeling of concentrating solar power plants. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyele, D.; Babatunde, O.; Monyei, C.; Olatomiwa, L.; Okediji, A.; Ighravwe, D.; Abiodun, O.; Onasanya, M.; Temikotan, K. Possibility of solar thermal power generation technologies in Nigeria: Challenges and policy directions. Renew. Energy Focus 2019, 29, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Shi, X.; Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, D. Research on the sintering temperature and absorptivity of corundum-based endothermic ceramics for solar thermal power generation. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 24415–24428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wu, T.; Wang, J.; Ling, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Guo, S.; Wei, X. Study of enhanced gasification of biochar by non-thermal concentrating solar power using novel high-flux solar simulator thermogravimetric analyzer system. Renew. Energy 2025, 242, 122436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.B.; Majó, M.; Mondragón, R.; Díaz-Heras, M.; Canales-Vázquez, J.; Almendros-Ibáñez, J.A.; Barreneche, C.; López, L.H. Experimental evaluation of carbon-coated sand as solar-absorbing and thermal energy storage media for concentrated solar power applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 269, 126082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Asfand, F.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G.; Bicer, Y.; Khan, M.; Farooq, M.; Pesyridis, A. Realizing the promise of concentrating solar power for thermal desalination: A review of technology configurations and optimizations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 115022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Rahbari, A.; Taheri, M.; Pottas, R.; Wang, B.; Hangi, M.; Matthews, L.; Yue, L.; Zapata, J.; Kreider, P.; et al. Experimental evaluation of an indirectly-irradiated packed-bed solar thermochemical reactor for calcination–carbonation chemical looping. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basem, A.; Moawed, M.; Abbood, M.H.; El-Maghlany, W.M. The design of a hybrid parabolic solar dish–steam power plant: An experimental study. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1949–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouhi, H.; Allouhi, A.; Bentamy, A.; Zafar, S.; Jamil, A. Solar Dish Stirling technology for sustainable power generation in Southern Morocco: 4-E analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pardo, A.; González-Aguilar, J.; Romero, M. Analysis of glint and glare produced by the receiver of small heliostat fields integrated in building façades. Methodology applicable to conventional central receiver systems. Sol. Energy 2015, 121, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernández, A.; Conceição, R.; Asselineau, C.-A.; Romero, M.; González-Aguilar, J. Advanced surface reconstruction method for solar reflective concentrators by flux mapping. Sol. Energy 2023, 266, 112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loghmari, I.; Milidonis, K.; Lipiński, W.; Papanicolas, C.N. Single- and multi-facet variable-focus adaptive-optics heliostats: A review. Sol. Energy 2025, 290, 113339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosens, P. Oscillations of a rigid heliostat mirror caused by fluctuating wind. Sol. Furn. Support Stud. 1960, 2, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.E.; Thayer, D.A.; Sahl, H.B. Design and characterization of solar concentrators. In Proceedings of the First Southeastern Conference, Huntsville, AL, USA, 24–26 March 1975; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cutting, F.M. Heliostat survivability and structural stability for wind loading. In Proceedings of the Miami International Conference, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 5–7 December 1977; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, J.H.; Matty, R.R.; Barton, G.H. Vortex shedding from square plates perpendicular to a ground plane. AIAA J. 1980, 18, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, W.H.; Mahmood, M. Some aspects of the flow past a square flat plate at high angle of attack. Dev. Mech. 1985, 13, 481–482. [Google Scholar]

- Bhumralkar, C.M.; Slemmons, A.J.; Nitz, K.C. Numerical study of local regional atmospheric changes caused by a large solar central receiver power plant. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1981, 20, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B. Collector deflections due to wind gusts and control scheme design. Sol. Energy 1980, 25, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, J.A.; Bienkiewicz, B.; Hosoya, N.; Cermak, J.E. Heliostat mean wind load reduction. Energy 1987, 12, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.E.; McBride, D.D.; Tate, R.E. Steady-state wind loading on parabolic trough solar collectors. In Proceedings of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Century 2 Solar Energy Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–15 August 1980; pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, L.M. Wind loading on tracking and field mounted solar collectors. ASME Sol. Eng. 1981, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeenia, N.; Yaghoubi, M. Analysis of wind flow around a parabolic collector (1) fluid flow. Renew. Energy 2007, 32, 1898–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paetzold, J.; Cochard, S.; Vassallo, A.; Fletcher, D.F. Wind engineering analysis of parabolic trough solar collectors: The effects of varying the trough depth. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2014, 135, 118–128, Correction in J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2016, 148, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emes, M.J.; Arjomandi, M.; Nathan, G.J. Effect of heliostat design wind speed on the levelised cost of electricity from concentrating solar thermal power tower plants. Sol. Energy 2015, 115, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, M.; Mier-Torrecilla, M.; Wüchner, R. Numerical simulation of wind loads on a parabolic trough solar collector using lattice Boltzmann and finite element methods. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2015, 146, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benammar, S.; Tee, K.F. Structural reliability analysis of a heliostat under wind load for concentrating solar power. Sol. Energy 2019, 181, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaabia, B.; Langlois, S.; Maheux, S. Effect of structure configurations and wind characteristics on the design of solar concentrator support structure under dynamic wind action. Wind. Struct. 2018, 27, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Guo, F.; Wu, S.; Chen, Z. A comprehensive simulation on optical and thermal performance of a cylindrical cavity receiver in a parabolic dish collector system. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christo, F.C. Numerical modelling of wind and dust patterns around a full-scale paraboloidal solar dish. Renew. Energy 2012, 39, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachicha, A.A.; Rodríguez, I.; Lehmkuhl, O.; Oliva, A. On the CFD&HT of the Flow around a Parabolic Trough Solar Collector under Real Working Conditions. Energy Procedia 2014, 49, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, L.C.; Bello-Ochende, T.; Meyer, J.P. Three-dimensional analysis and numerical optimization of combined natural convection and radiation heat loss in solar cavity receiver with plate fins insert. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 101, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, J.Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zuo, H.; Hu, W.; Wei, K. Harmonic response analysis of a large dish solar thermal power generation system with wind-induced vibration. Sol. Energy 2019, 181, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; E, J.Q.; Liu, T.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, Q. Effects of different poses and wind speeds on the flow field of the dish solar concentrator based on virtual wind tunnel experiment with constant wind. J. Cent. South Univ. 2018, 35, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Gong, J.; Cai, H. Numerical simulation of impact on wind load due to mirror gap effect for parabolic dish solar concentrator. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A-J. Power Energy 2019, 233, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Jin, L.; Wei, J. Multiphysics-coupled study of wind load effects on optical performance of parabolic trough collector. Sol. Energy 2020, 207, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Liu, G.; E, J.Q.; Zuo, W.; Wei, K.; Hu, W.; Tan, J.; Zhong, D. Catastrophic analysis on the stability of a large dish solar thermal power generation system with wind-induced vibration. Sol. Energy 2019, 183, 18340–18349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schär, S.; Marelli, S.; Sudret, B. Emulating the dynamics of complex systems using autoregressive models on manifolds (mNARX). Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 208, 110956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Zhu, W.; Li, H.; Ji, W.; Soares, C.G.; Wang, J. Failure warning for offshore wind turbines based on Autoregressive models. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 332, 121448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Su, Y.; Liang, J.; Jia, G.; Chen, M.; Nie, D.; E, J. Wind-Induced Stability Identification and Safety Grade Catastrophe Evaluation of a Dish Concentrating Solar Thermal Power System. Energies 2025, 18, 6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Tan, J.; Wei, K.; Huang, Z.; Zhong, D.; Xie, F. Effects of different poses and wind speeds on wind-induced vibration characteristics of a dish solar concentrator system. Renew. Energy 2021, 168, 1308–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzair, M.; Anderson, T.N.; Nates, R.J. The impact of the parabolic dish concentrator on the wind induced heat loss from its receiver. Solar Energy 2017, 151, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.; Hua, Z.; Sun, G.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, C. A study on methods for determining phase space reconstruction parameters. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 20, 011006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, V.S.; Spano, M.L.; Lockhart, T.E. Effect of data length on time delay and embedding dimension for calculating the Lyapunov exponent in walking. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20200311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Some Data on Force and Moment Coefficients | α = 0° | α = 45° | α = 135° | α = 180° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cx1 under β = 0° | 1.75 | 0.517 | 0.876 | 1.97 |

| Cx2 under β = 45° | 0.377 | 0.292 | 0.224 | 1.02 |

| η1 = (Cx2 − Cx1)/Cx1 | −3.64 | −0.770 | −2.91 | −0.930 |

| CMy1 under β = 0° | 8.36 | 4.91 | 6.01 | 7.99 |

| CMy2 under β = 45° | 1.34 | 2.47 | 0.980 | 3.01 |

| η2 = (CMy2 − CMy1)/CMy1 | −5.24 | −0.990 | −5.13 | −1.65 |

| CMz1 under β = 0° | 8.36 | 3.18 | 4.92 | 8.81 |

| CMz2 under β = 45° | 1.87 | 0.325 | 0.924 | 6.68 |

| η3 = (CMz2 − CMz1)/CMz1 | −3.47 | −8.78 | −4.32 | −0.319 |

| α = 0°, β = 0° | α = 45°, β = 0° | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ1 | τ2 | τ | d | τ1 | τ2 | τ | d | |

| Cx | 3 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| Cy | 3 | 12 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 12 |

| Cz | 36 | 18 | 32 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

| CMx | 17 | 17 | 17 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| CMy | 26 | 19 | 24 | 13 | 27 | 13 | 24 | 8 |

| CMz | 3 | 11 | 5 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 12 |

| Cx(9) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

| Cy(9) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

| Cz(9) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 10 |

| CMx(9) | 30 | 20 | 28 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| CMy(9) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 8 |

| CMz(9) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zuo, H.; Liang, J.; Su, Y.; Jia, G.; Nie, D.; Chen, M.; E, J. Effects of Pulsating Wind-Induced Loads on the Chaos Behavior of a Dish Concentrating Solar Thermal Power System. Energies 2026, 19, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010182

Zuo H, Liang J, Su Y, Jia G, Nie D, Chen M, E J. Effects of Pulsating Wind-Induced Loads on the Chaos Behavior of a Dish Concentrating Solar Thermal Power System. Energies. 2026; 19(1):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010182

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuo, Hongyan, Jingwei Liang, Yuhao Su, Guohai Jia, Duzhong Nie, Mang Chen, and Jiaqiang E. 2026. "Effects of Pulsating Wind-Induced Loads on the Chaos Behavior of a Dish Concentrating Solar Thermal Power System" Energies 19, no. 1: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010182

APA StyleZuo, H., Liang, J., Su, Y., Jia, G., Nie, D., Chen, M., & E, J. (2026). Effects of Pulsating Wind-Induced Loads on the Chaos Behavior of a Dish Concentrating Solar Thermal Power System. Energies, 19(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010182