Barriers to the Diffusion of Clean Energy Communities: Comparing Early Adopters and the General Public

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Overview of Existing Research on Barriers and Adopter Categories in Clean Energy Diffusion

3. Methodology

3.1. Qualitative Study with CEC Members

3.2. Citizen Survey on CECs

4. Results

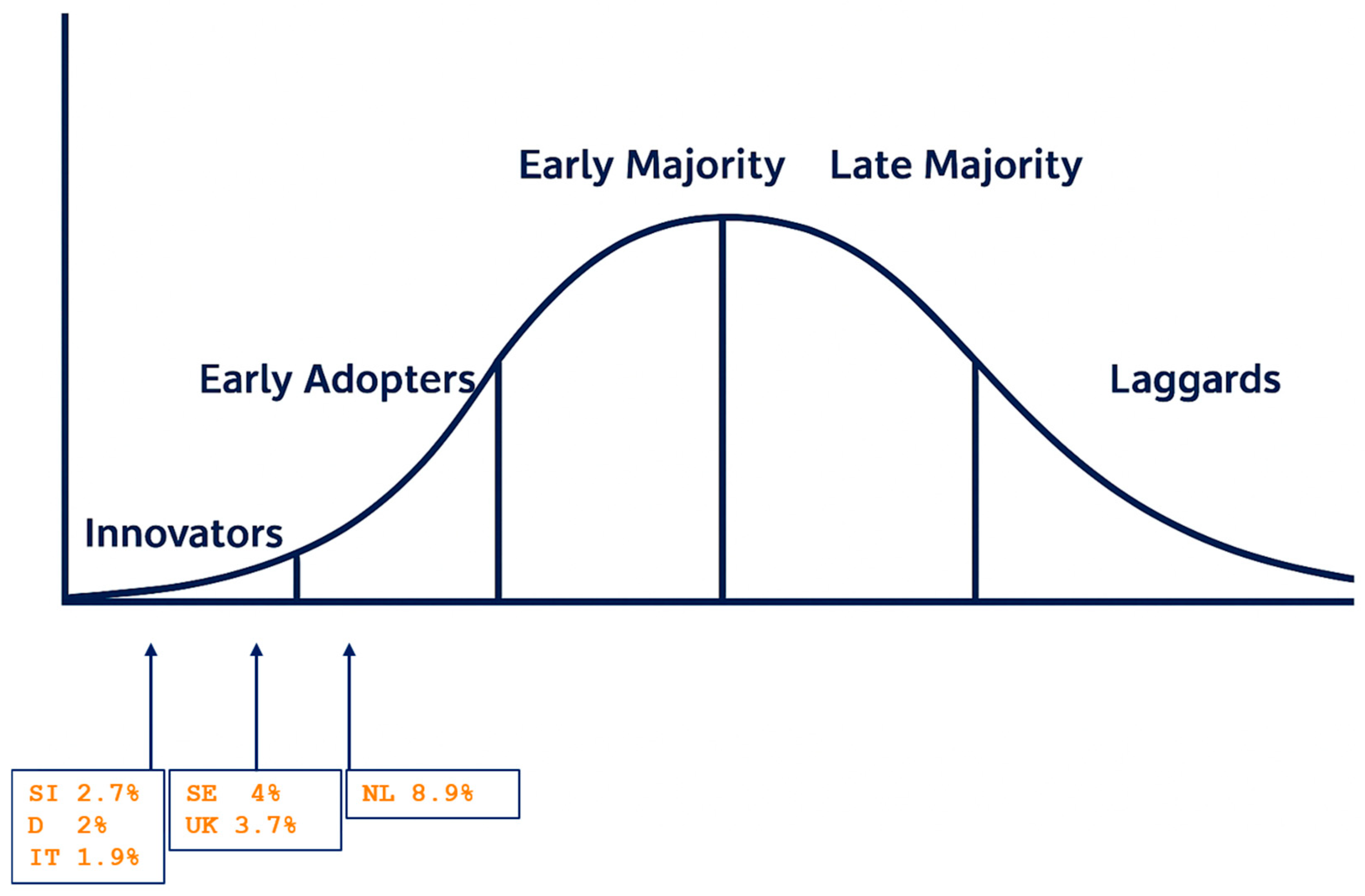

4.1. Awareness of CECs’ Existence in the Studied Countries

4.1.1. CEC Members’ Perspective on Barriers to Joining or Starting CECs

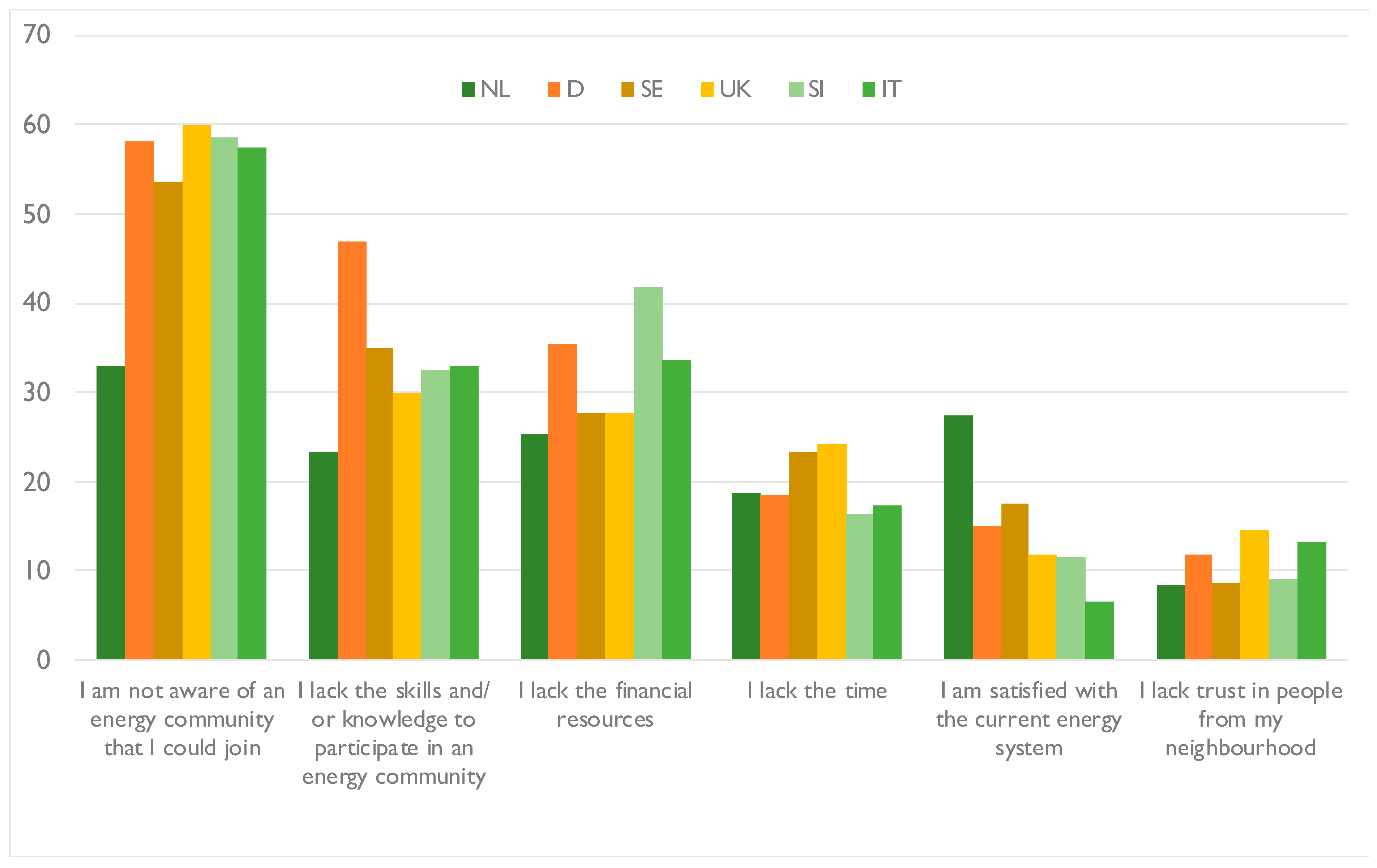

4.1.2. Barriers to Joining CECs as Perceived by the General Public Across Countries

4.1.3. Comparison of Barriers Identified by CEC Members and the Potential Adopters of Clean Energy

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings and Implications for Policy and Practice

5.2. Study Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEC | Clean energy community |

| RES | Renewable energy source |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

Appendix A

| Country | Legal Framework for CECs | Support Mechanisms/Incentives | Key Systemic Barriers Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Legal frameworks exist; cooperative law facilitates CEC formation | FiT, smart meter act, feed-in premiums, cooperative law | Complex legislation, high grid connection cost, administrative burden |

| Italy | Law n.8/2020 introduces legal framework for RECs (Renewable Energy Community) | Municipal/regional incentives, FiT for RECs, tax credits | Low awareness, scepticism, outdated legislation, eco-gentrification |

| The Netherlands | Legal framework for renewable electricity production and CECs | SDE+, postal code scheme, tax deduction for community energy | Administrative burden, unclear regulatory roles, scalability |

| Slovenia | REC defined in recent by-law | Net metering, FiT/premium tariffs, operational support | Small market, limited resources, unclear roles, no umbrella org. |

| Sweden | No specific legal framework for CECs | Tradable green certificates, tax deductions, infrastructure subsidies | No EC definition, lack of specific support, low institutional focus |

| UK | CEC defined in national strategy; early strategy in place | Former FiT, community energy funds, R&D support programs | Policy instability, diminishing support, reliance on volunteers |

References

- Blasch, J.; van der Grijp, N.M.; Petrovics, D.; Palm, J.; Bocken, N.; Darby, S.J.; Mlinarič, M. New Clean Energy Communities in Polycentric Settings: Four Avenues for Future Research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, T.; Devine-Wright, P. Positive Energies? An Empirical Study of Community Energy Participation and Attitudes towards Renewable Energy. Energy Policy 2018, 118, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Jones, D.; Wang, T.; Blasch, J. Energy Communities and Prosumerism: Emerging Trends in Citizen Participation. Energy Policy 2024, 179, 113421. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, F.; Campana, P.; Censi, R.; Di Renzo, M.; Tarola, A.M. Energy Communities in the Transition to Renewable Sources: Innovative Models of Energy Self-Sufficiency through Organic Waste. Energies 2024, 17, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nucci, M.R.; Krug, M.; Schwarz, L.; Gatta, V.; Laes, E. Learning from Other Community Renewable Energy Projects: Transnational Transfer of Multi-Functional Energy Gardens from the Netherlands to Germany. Energies 2023, 16, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummer, V. Community Energy—Benefits and Barriers: A Comparative Literature Review of Community Energy Projects. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2018, 8, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Obuseh, F.; Reuter, M.; Hahnel, U.J.J. Social Acceptance of Community Renewable Energy: A Review of Empirical Studies in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 176, 113214. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, T.; Wilson, C. Why Aren’t We Prosuming? Reviewing Contemporary Challenges and Opportunities for Community Energy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 106, 103301. [Google Scholar]

- Boostani, P.; Pellegrini-Masini, G.; Klein, J. The Role of Community Energy Schemes in Reducing Energy Poverty and Promoting Social Inclusion: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2024, 17, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- De Franco, A.; Campana, P.; Censi, R.; Di Renzo, M.; Tarola, A.M. Drivers, Motivations and Barriers in the Creation of Energy Communities: Insights from the City of Segrate, Italy. Energies 2024, 17, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Koirala, B.P.; van Oost, E. A Review of the Role of Community Energy in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Energies 2024, 17, 367. [Google Scholar]

- Horstink, L.; Gährs, S.; Fraaij, A. The Role of Energy Communities in the European Energy Transition: A Comparative Analysis. Energ. 2021, 14, 6016. [Google Scholar]

- Lazdins, A.; Zilans, A.; Barda, I. Exploring the Role of Intermediaries in Promoting Community Renewable Energy Projects. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112441. [Google Scholar]

- De Franco, A.; Spina, G.; Nicita, A. Trust, Norms and the Adoption of Renewable Energy Communities: Evidence from Italy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 101, 102404. [Google Scholar]

- Alipour, M.; Salim, H.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O. Predictors, Taxonomy of Predictors, and Correlations of Predictors with the Decision Behaviour of Residential Solar Photovoltaics Adoption: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 109749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruokamo, E.; Kinnunen, J.; Luoma, A.; Vainio, A. Diffusion of Renewable Energy Communities: A Review of Trends and Needs for Future Research. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 174, 113108. [Google Scholar]

- Faiers, A.; Neame, C. Consumer Attitudes Towards Domestic Solar Power Systems. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Varnhagen, S.; Campbell, K. Faculty Adoption of Teaching and Learning Technologies: Contrasting Earlier Adopters and Mainstream Faculty. Can. J. High. Educ. 1998, 28, 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataray, T.; Nitesh, B.; Yarram, B.; Sinha, S.; Cuce, E.; Shaik, S.; Roy, A. Integration of Smart Grid with Renewable Energy Sources: Opportunities and Challenges–A Comprehensive Review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 58, 103363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, I.M.; Anagnostopoulou, E.G. Identifying Barriers in the Diffusion of Renewable Energy Sources. Energy Policy 2015, 80, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, A.K.; Kafizadeh Kashan, M.; Maleki, A.; Jafari, N.; Hashemi, H. Assessment of Barriers to Renewable Energy Development Using Stakeholders Approach. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2526–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiasoumas, G.; Berbakov, L.; Janev, V.; Asmundo, A.; Olabarrieta, E.; Vinci, A.; Baglietto, G.; Georghiou, G.E. Key Aspects and Challenges in the Implementation of Energy Communities. Energies 2023, 16, 4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitern, A. Participation in Energy Communities: Findings from Estonia. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2022, 12, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Lazdins, R.; Mutule, A.; Zalostiba, D. PV Energy Communities—Challenges and Barriers from a Consumer Perspective: A Literature Review. Energies 2021, 14, 4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, J. Household Installation of Solar Panels–Motives and Barriers in a 10-Year Perspective. Energy Policy 2018, 113, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Ganguly, S. Opportunities, Barriers and Issues with Renewable Energy Development—A Discussion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, L.; Schöne, N.; Flessa, A.; Fragkos, P.; Heinz, B. Costs and Benefits of Citizen Participation in the Energy Transition: Investigating the Economic Viability of Prosumers on Islands—The Case of Mayotte. Energies 2024, 17, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbes, C.; Brummer, V.; Rognli, J.; Blazejewski, S.; Gericke, N. Responding to Policy Change: New Business Models for Renewable Energy Cooperatives—Barriers Perceived by Cooperatives’ Members. Energy Policy 2017, 109, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2020; VERBI Software: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kamin, T.; Golob, U.; Medved, P.; Kogovšek, T. Benefits for Community Members in Terms of Increased Access to Clean, Secure and Affordable Energy. Deliverable 6.1 Developed as Part of the NEWCOMERS Project, Funded Under EU H2020 Grant Agreement 837752. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5d793f2e9&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Andor, M.A.; Blasch, J.; Cordes, O.; Hoenow, N.C.; Karki, K.; Koch, B.Y.; Micke, K.; Niehues, D.; Tomberg, L. Report on Cross-Country Citizen Survey. Deliverable 6.3 Developed as Part of the NEWCOMERS Project, Funded Under EU H2020 Grant Agreement 837752. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5e7c12599&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Eurostat. European Statistics Database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- European Social Survey (ESS). European Social Survey Round 9. European Social Survey 2018. Available online: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Medved, P.; Golob, U.; Kamin, T. Learning and Diffusion of Knowledge in Clean Energy Communities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2023, 41, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, T. Energy Communities in Different National Settings—Barriers, Enablers and Best Practices. Deliverable 3.3. Developed as Part of the NEWCOMERS Project, Funded Under EU H2020 Grant Agreement 837752. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5ddd7efb8&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Musolino, M.; Maggio, G.; D’Aleo, E.; Nicita, A. Three Case Studies to Explore Relevant Features of Emerging Renewable Energy Communities in Italy. Renew. Energy 2023, 210, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.; Busch, H.; Hansen, T.; Isakovic, A. Context and Agency in Urban Community Energy Initiatives: An Analysis of Six Case Studies from the Baltic Sea Region. Energy Policy 2021, 148, 111956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Key Barriers Identified in the Literature | Incentives/Support Mentioned | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Legal complexity, grid connection bureaucracy, lack of authority support, financing barriers | Feed-in Tariffs (FiTs), RES cooperatives | Di Nucci et al. [5] |

| Italy | Scepticism, low awareness, financial uncertainty, eco-gentrification | Municipal and regional incentives | De Franco et al. [11] |

| The Netherlands | High administrative burden, unclear regulatory roles, split incentives, scalability issues, financial viability risk | Net metering, zip code regulation, regulatory exemption pilot | Meitern [24], Di Nucci et al. [5] |

| Sweden | Shift in adopter motivation, eco-gentrification in PV diffusion | PV subsidies noted in passing | Palm [26] |

| UK | Policy instability, modest awareness, trust concerns | FiT | UK cases reviewed in Brummer [6] |

| Country | Interviewees (Male/Female) |

|---|---|

| Germany | 5 (5/0) |

| Italy | 8 (4/4) |

| The Netherlands | 13 (7/6) |

| Slovenia | 4 (3/1) |

| Sweden | 5 (2/3) |

| United Kingdom | 7 (4/3) |

| Total | 42 |

| Country | Sample Size | Mean Age | Gender (Male %) | Gender (Female %) | Below Upper Secondary Education (%) | Upper Secondary/Non-Tertiary Education (%) | Tertiary Education (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 1500 | 45.79 | 50.53 | 49.47 | 19.53 | 54.47 | 26 |

| Italy | 1500 | 45.05 | 48.07 | 51.93 | 26.47 | 54.4 | 19.13 |

| United Kingdom | 1500 | 44.61 | 49.73 | 50.27 | 16 | 42.13 | 41.87 |

| Sweden | 1500 | 43.34 | 46.6 | 53.4 | 14.93 | 50.47 | 34.6 |

| The Netherlands | 1499 | 45.3 | 50.23 | 49.77 | 17.14 | 46.7 | 36.16 |

| Slovenia | 1500 | 44.93 | 51.8 | 48.2 | 3.93 | 66.73 | 29.33 |

| Total | 8999 | 44.84 | 49.49 | 50.51 | 16.34 | 52.48 | 31.18 |

| Country | Survey: Top Perceived Barriers | Interviews: Key Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | Lack of awareness; lack of knowledge/skills (47%); financial constraints; moderate trust concerns | Legislative barriers; high perceived complexity; financial viability issues; low awareness |

| Italy | Lack of awareness; financial constraints; dissatisfaction with current system; moderate trust concerns | Lack of regulation; administrative red tape; low awareness; eco-gentrification; financial burden |

| The Netherlands | Relatively high awareness (30%); satisfaction with current system; low trust concerns | Regulatory barriers; red tape; difficulty scaling; awareness issues; financial expectations |

| Slovenia | Lack of awareness (~60%); high financial concern; moderate dissatisfaction with energy system | Lack of legal frameworks; heavy improvisation; awareness/education gaps; affordability |

| Sweden | Lack of awareness; minor concern about time; low trust concern | Time commitment; internal consensus challenges; awareness challenges |

| UK | Lack of awareness; some time constraints; dissatisfaction with current system; slight trust concern | Consensus building; management challenges; media misinformation; time demands |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamin, T.; Golob, U.; Kogovšek, T. Barriers to the Diffusion of Clean Energy Communities: Comparing Early Adopters and the General Public. Energies 2025, 18, 2248. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18092248

Kamin T, Golob U, Kogovšek T. Barriers to the Diffusion of Clean Energy Communities: Comparing Early Adopters and the General Public. Energies. 2025; 18(9):2248. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18092248

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamin, Tanja, Urša Golob, and Tina Kogovšek. 2025. "Barriers to the Diffusion of Clean Energy Communities: Comparing Early Adopters and the General Public" Energies 18, no. 9: 2248. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18092248

APA StyleKamin, T., Golob, U., & Kogovšek, T. (2025). Barriers to the Diffusion of Clean Energy Communities: Comparing Early Adopters and the General Public. Energies, 18(9), 2248. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18092248