Optimization Study of Air-Based Cooling Photovoltaic Roofs: Experimental and Numerical Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aim and Objectives

3. Methodology

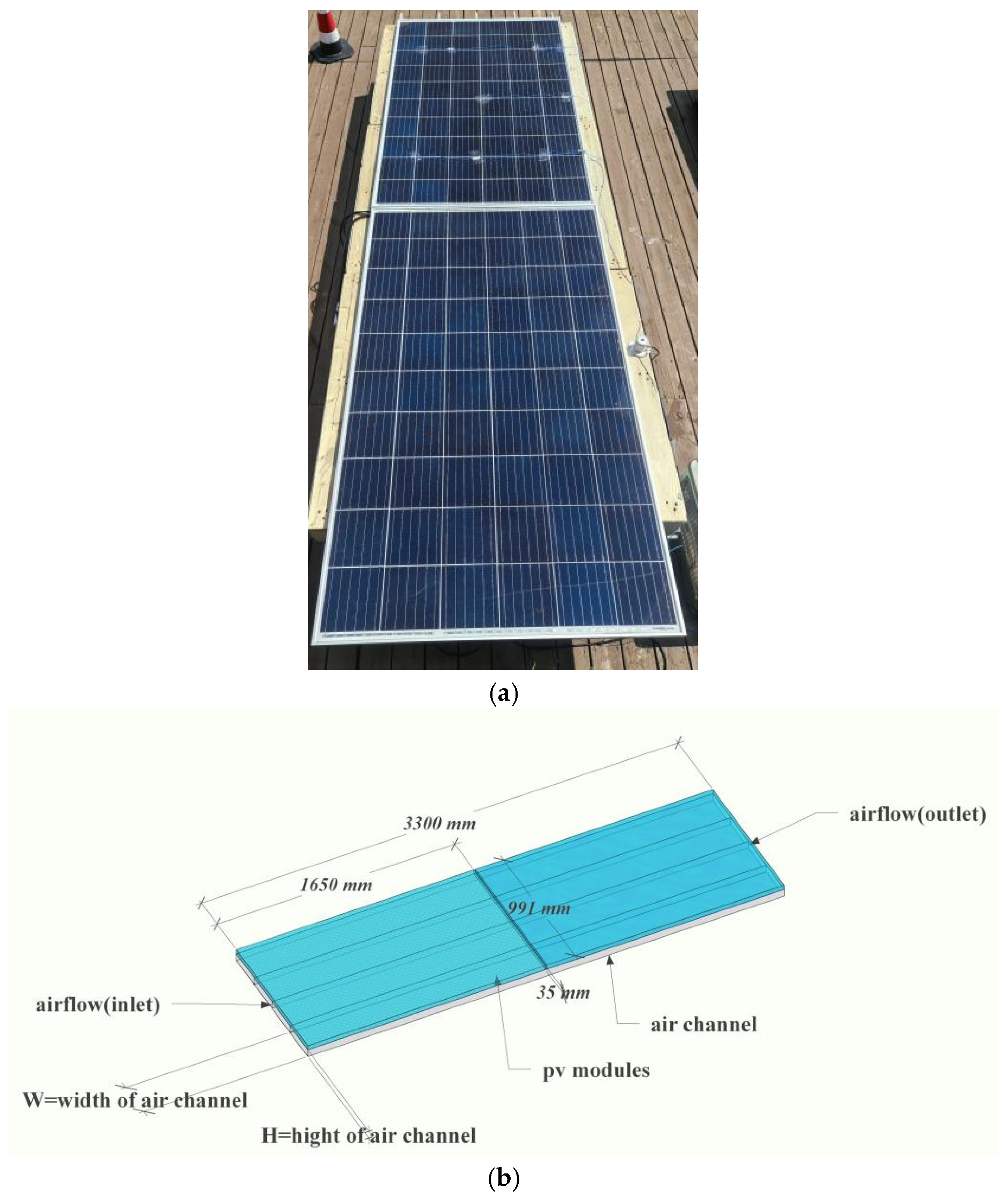

3.1. Experimental Setup and Procedure

3.2. Numerical Models for the Air-Based Cooling PV Roofs

3.2.1. Physical Model

3.2.2. Mathematical Formulation

3.3. Boundary Conditions

3.4. Grid Independence

3.5. Parametric Studies on Air Channel

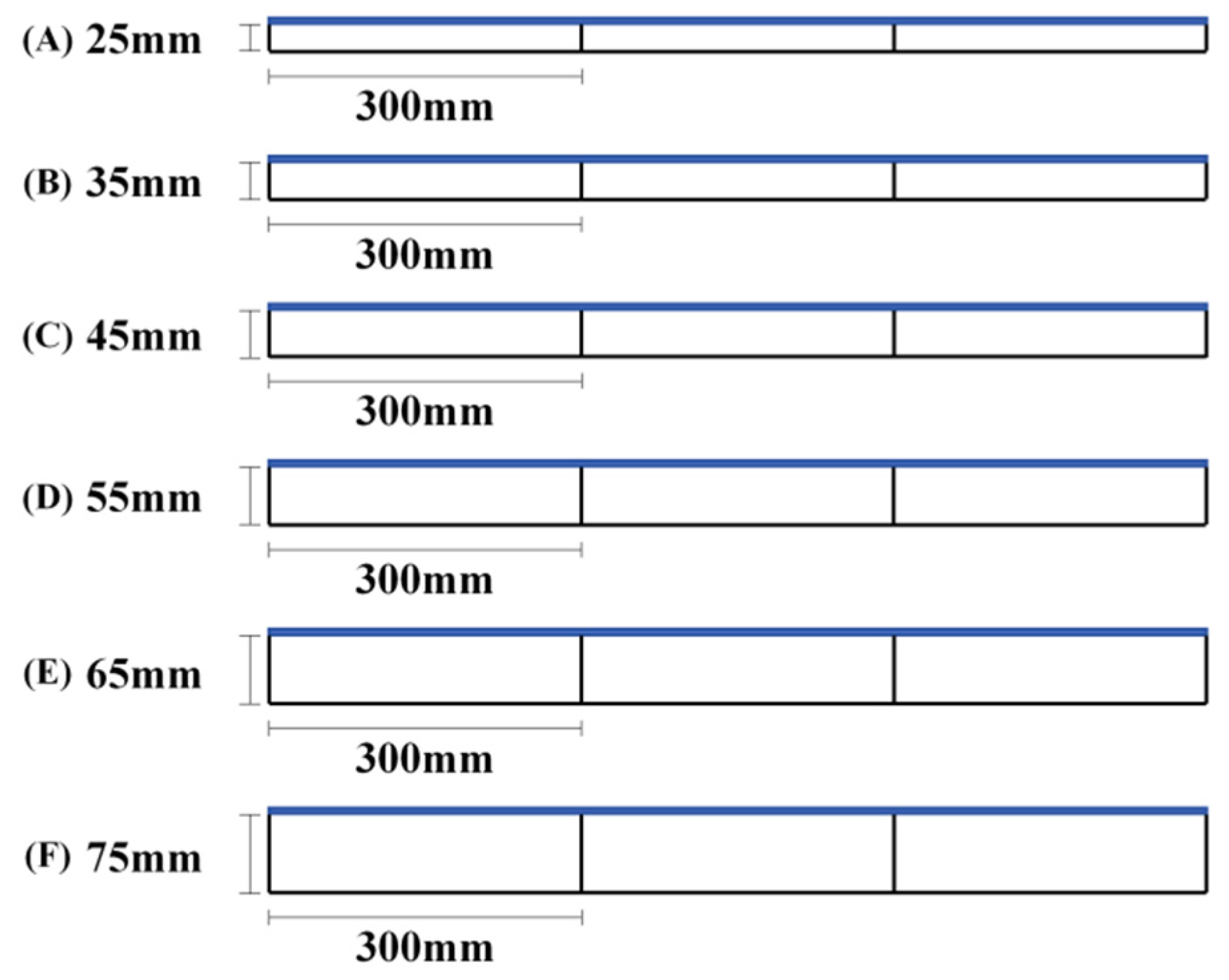

3.5.1. Case 1 Varying Air Channel Heights

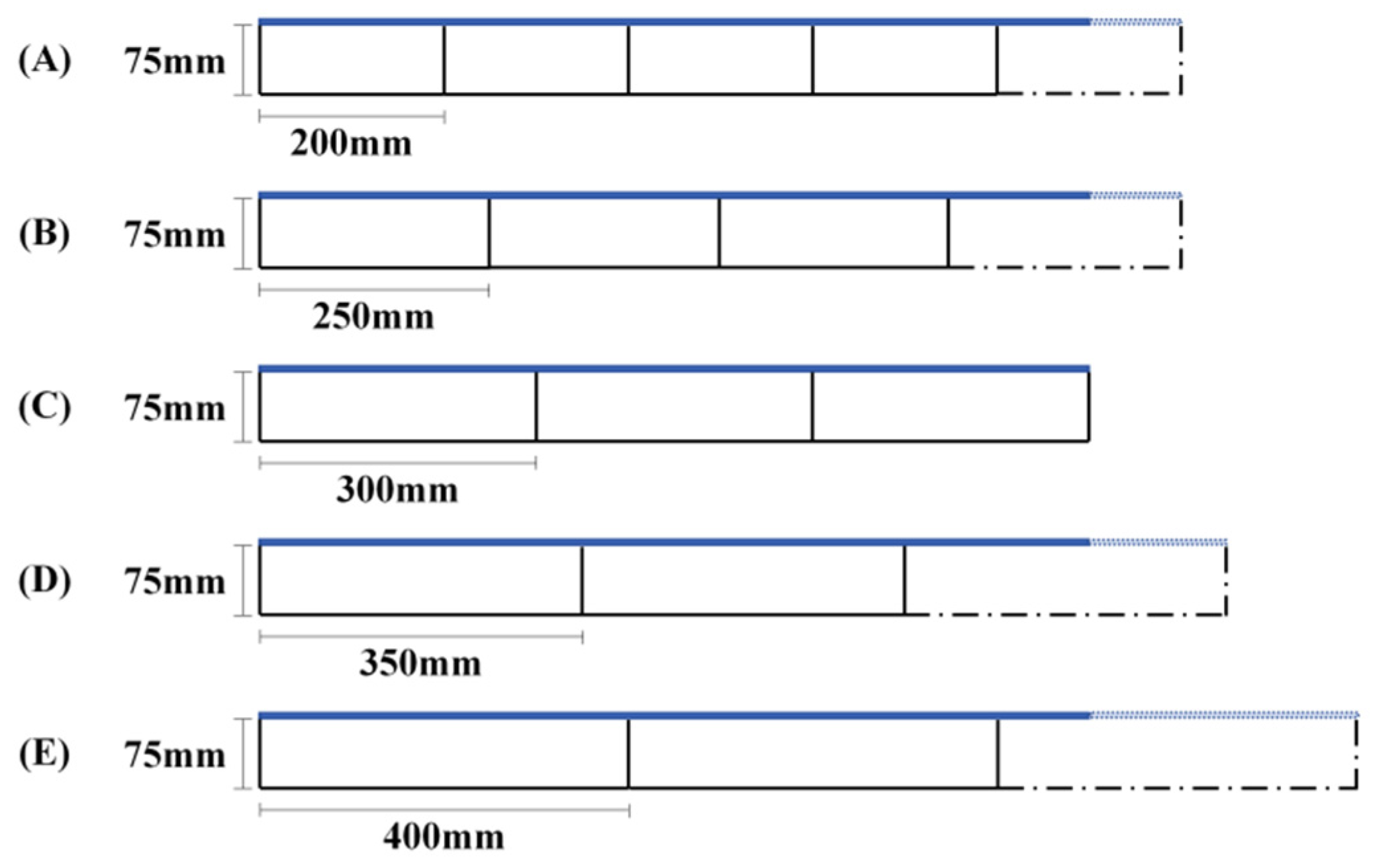

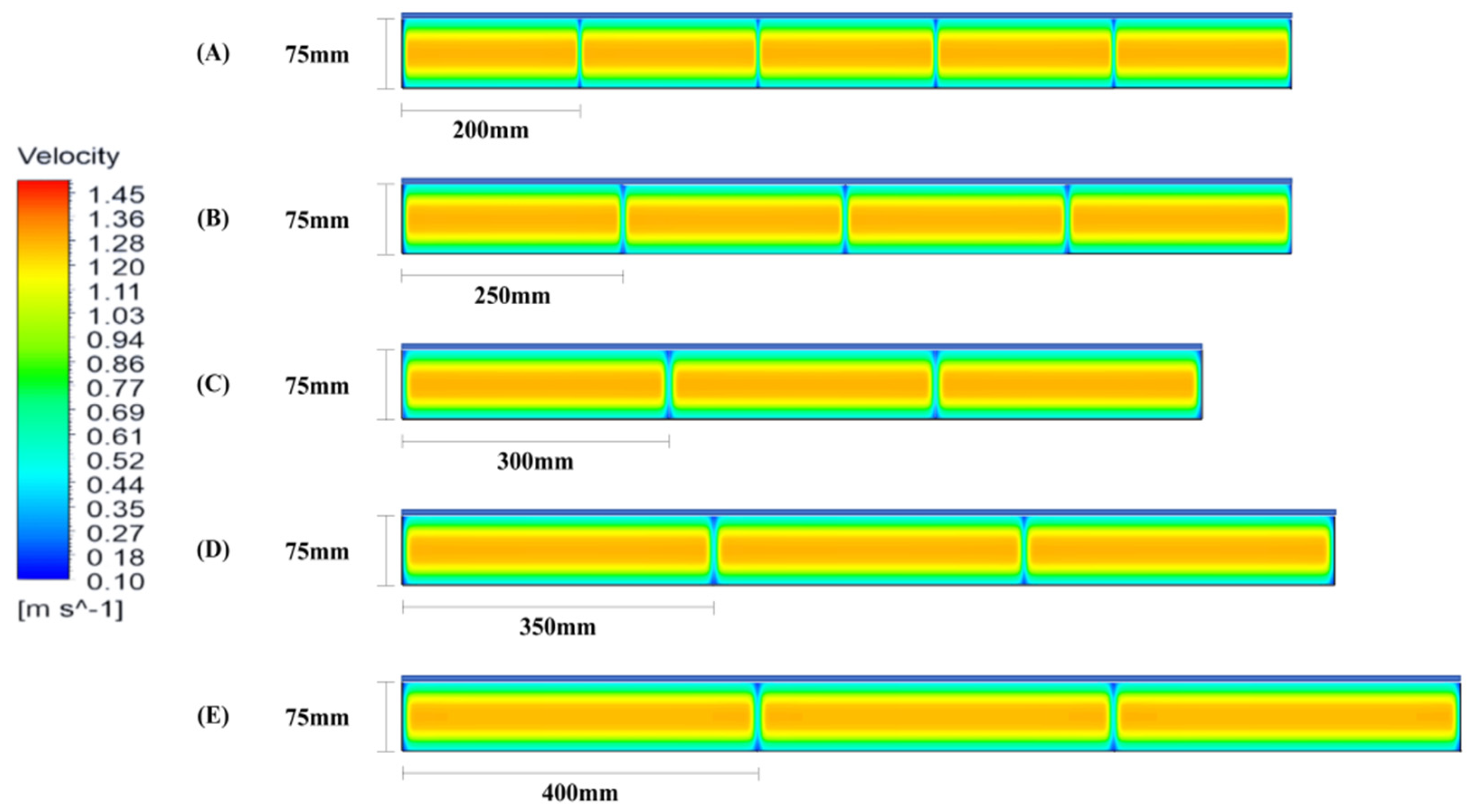

3.5.2. Case 2 Varying Air Channel Widths

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Results

4.1.1. Model Validation

4.1.2. Non-Uniformity of Surface Temperature

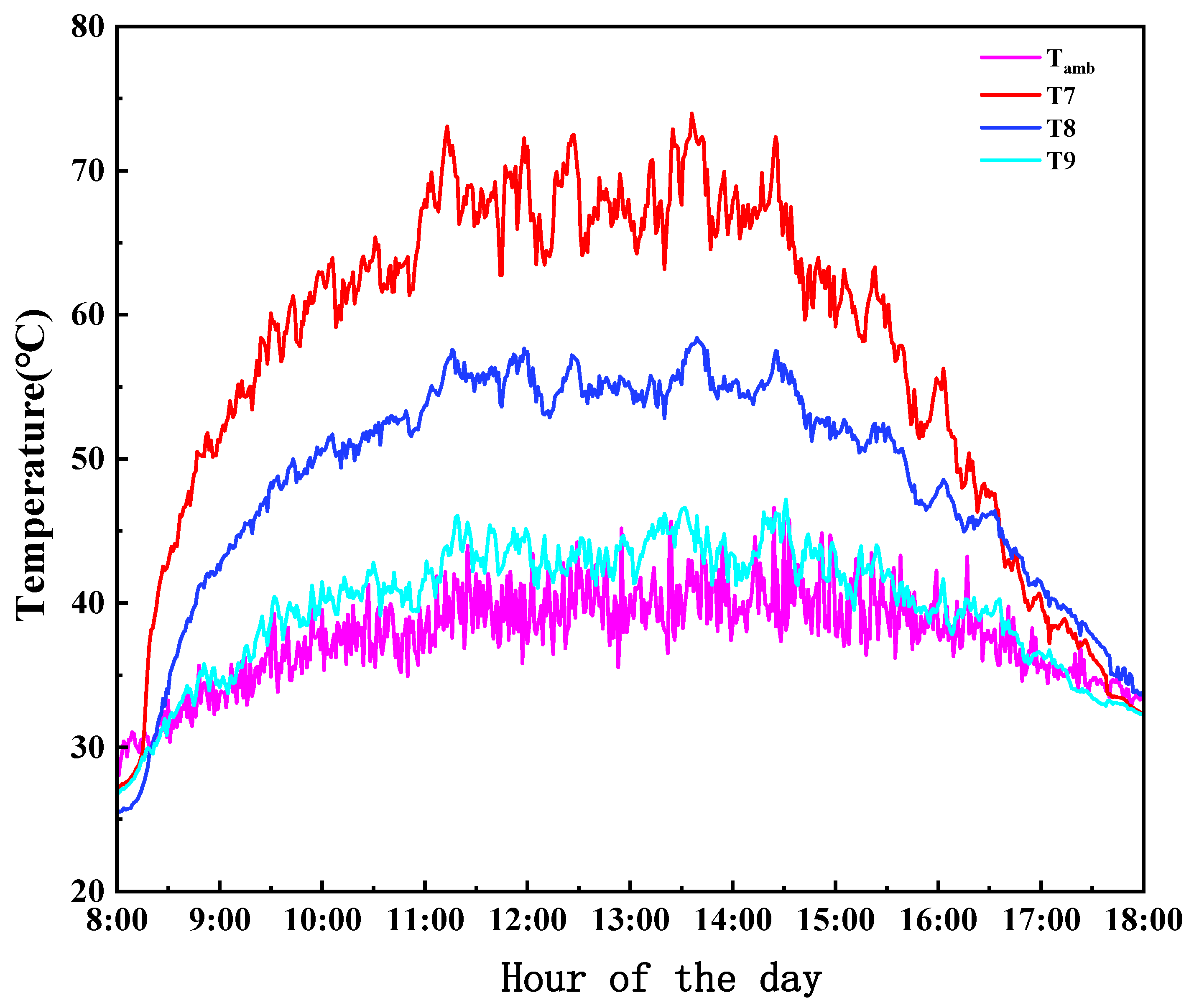

4.1.3. Shade Effect

4.1.4. Electrical Performance

4.2. Simulation Results

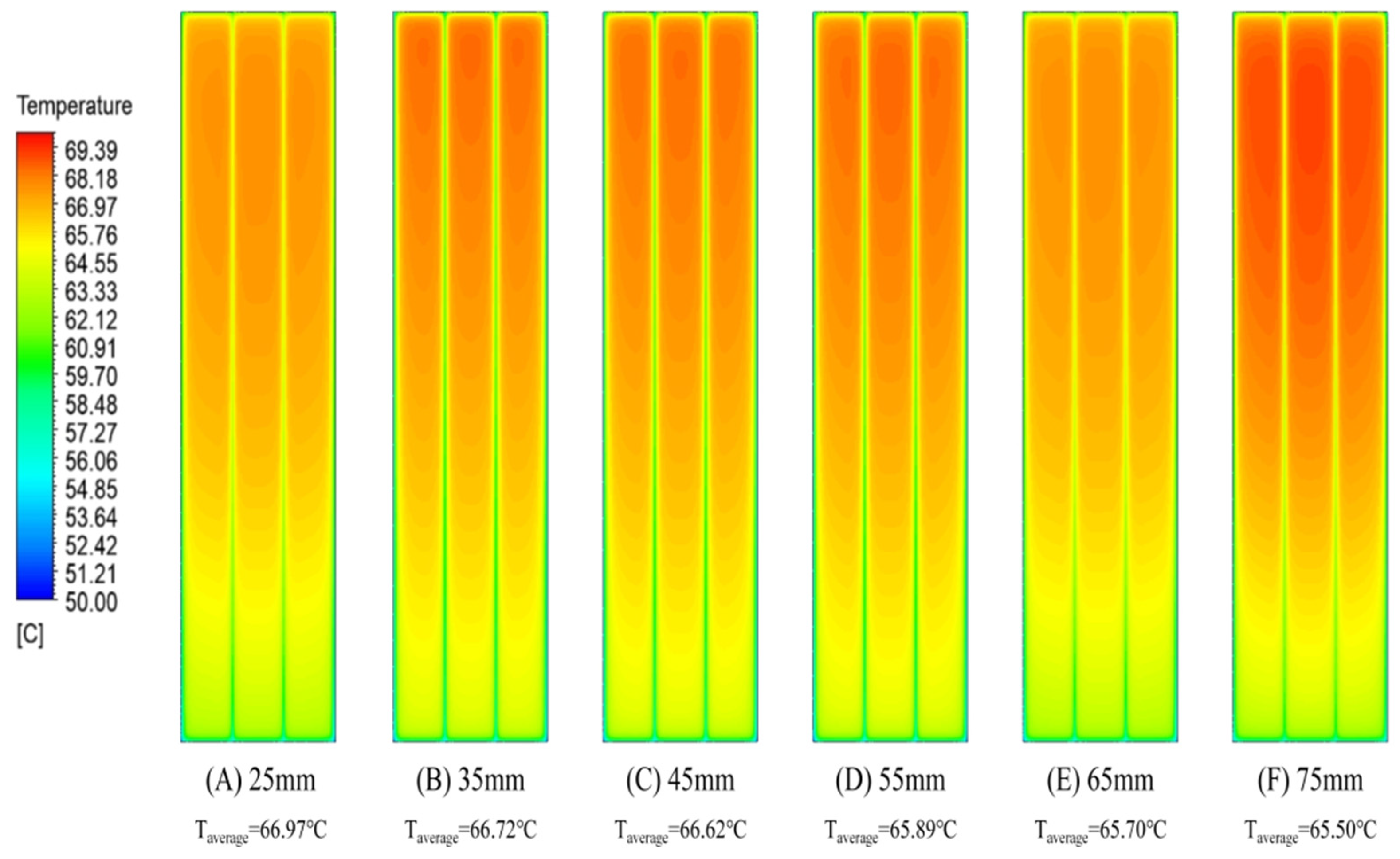

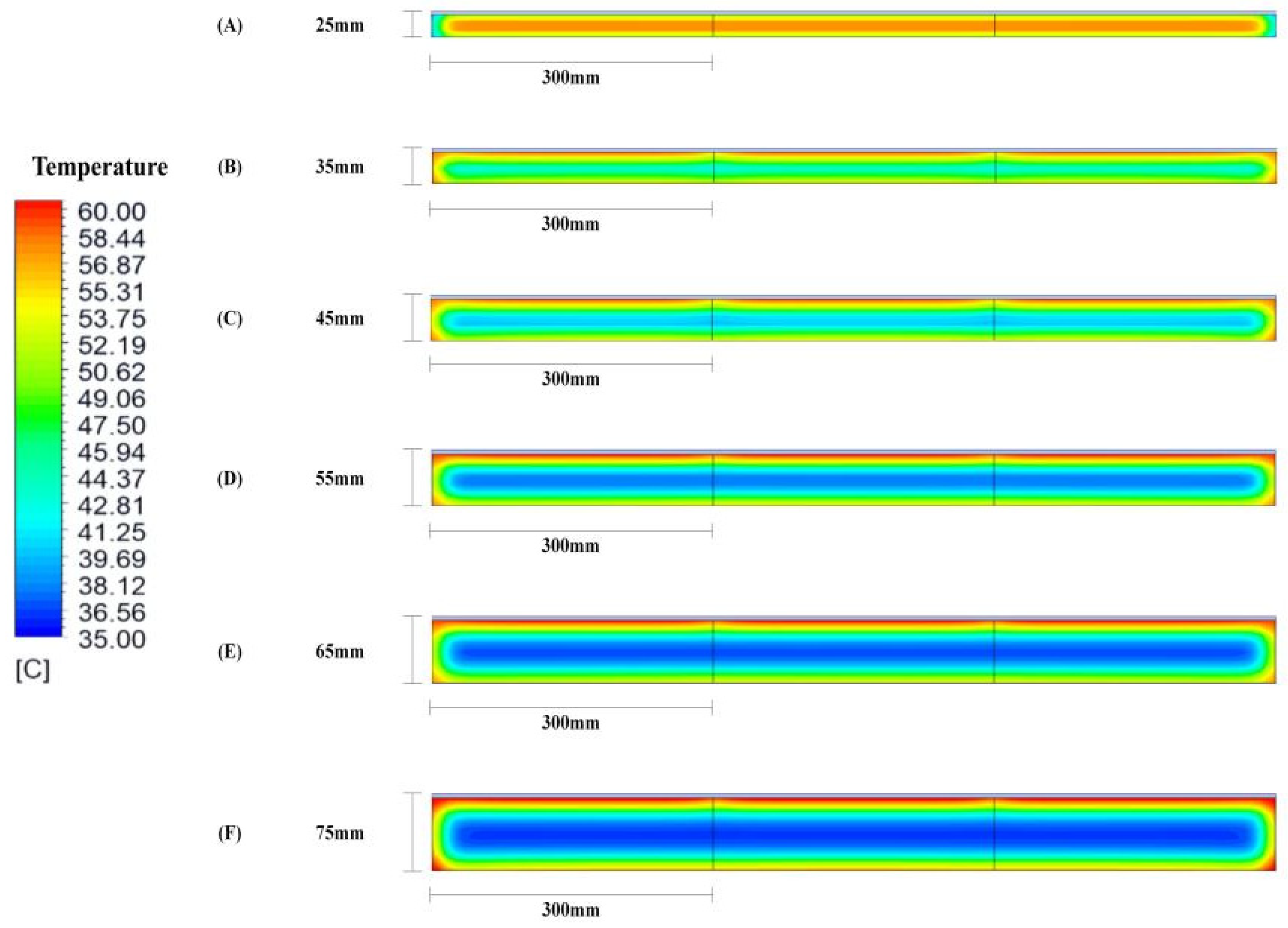

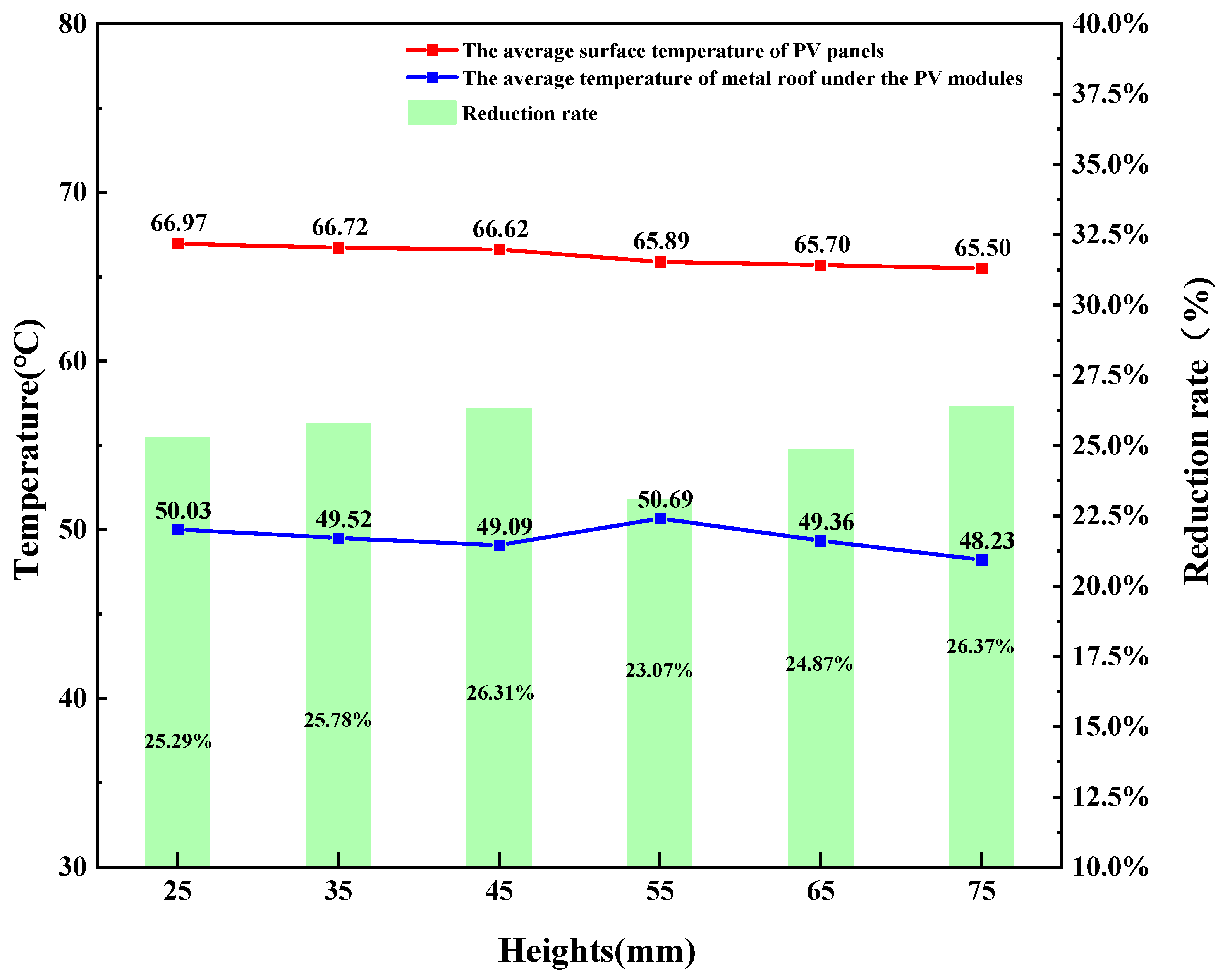

4.2.1. Case 1 Varying Air Channel Heights

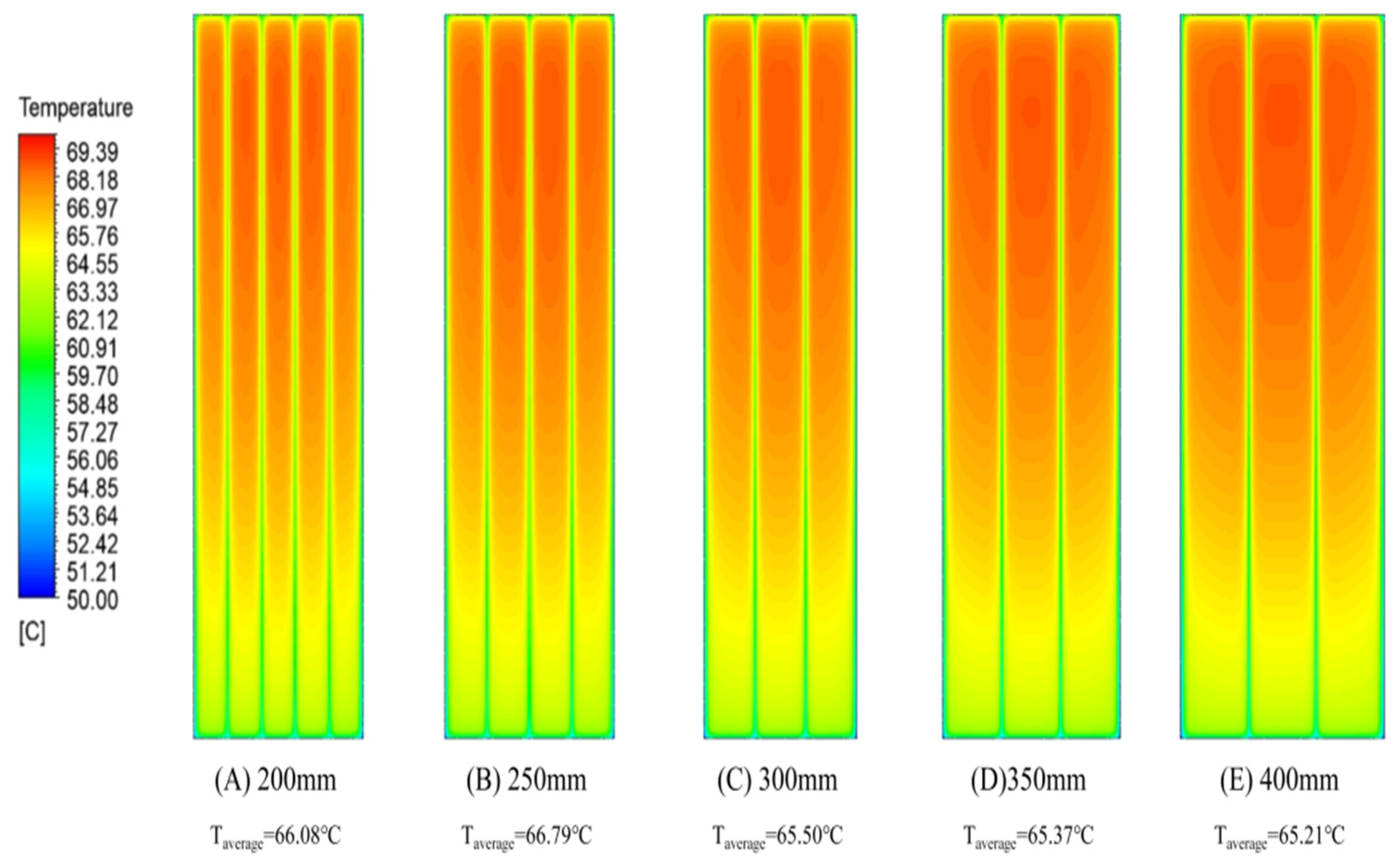

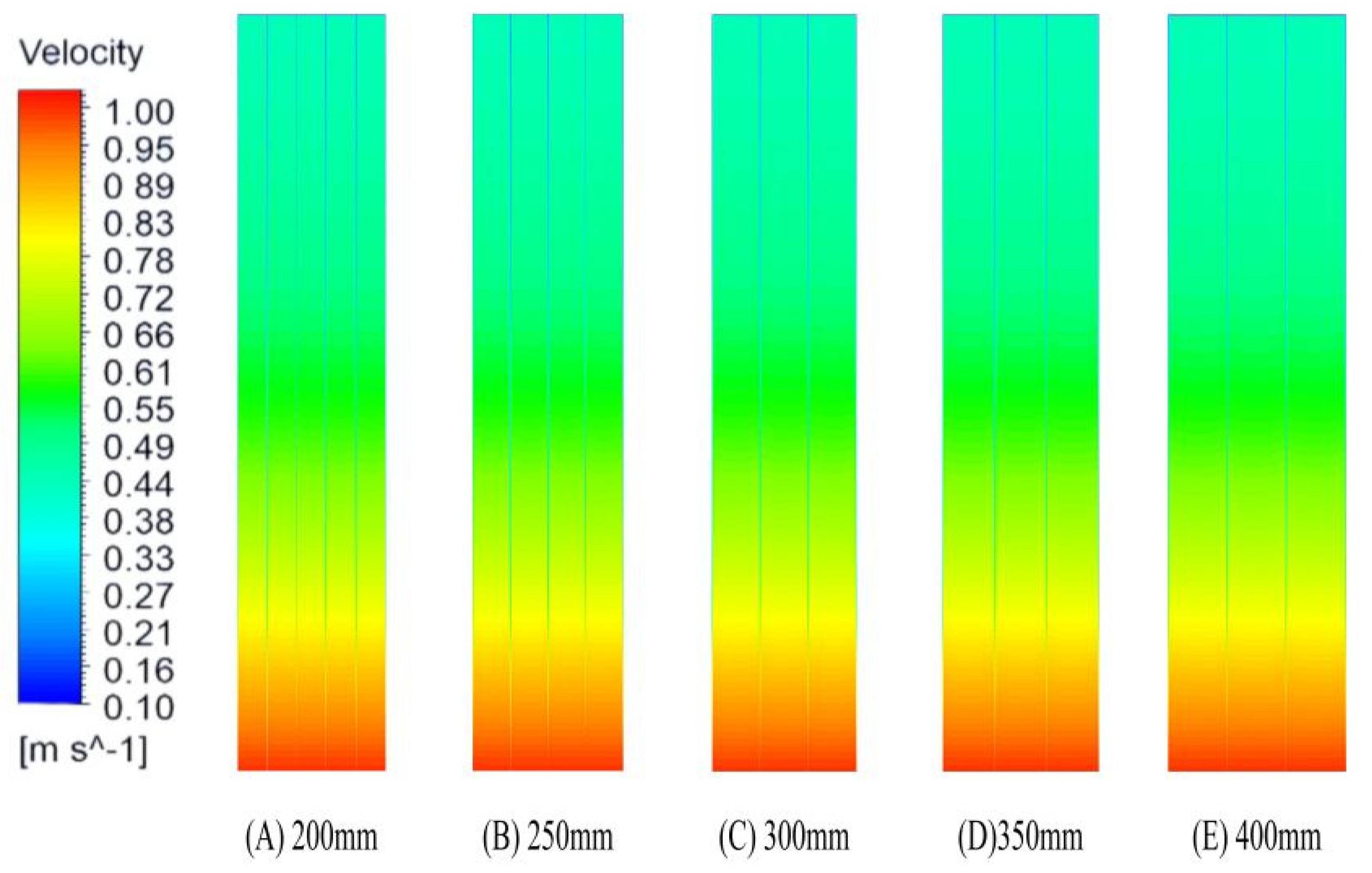

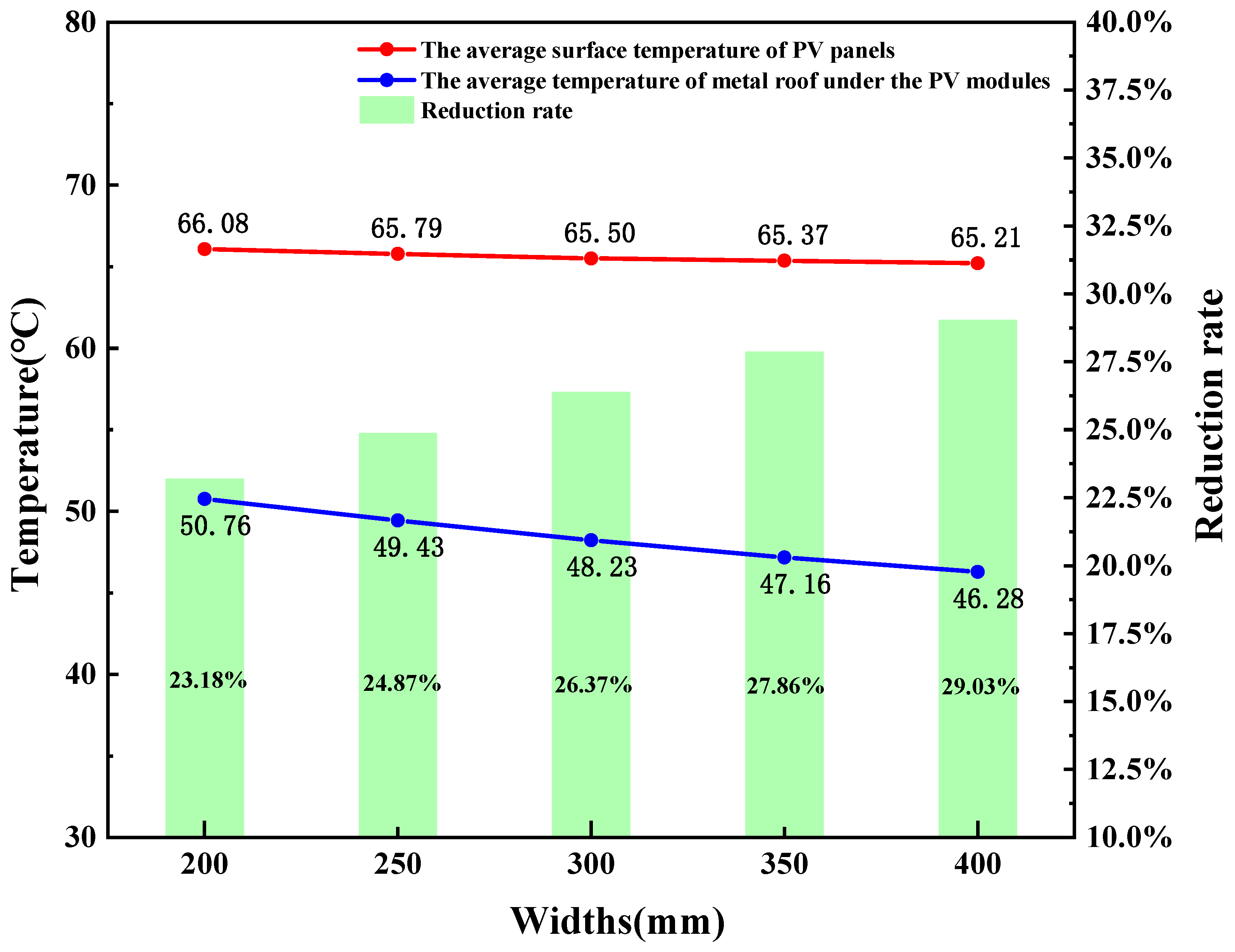

4.2.2. Case 2 Varying Air Channel Widths

5. Discussion

5.1. Cooling for Metal Roof

5.2. Cooling Performance Comparison for Varying Physical Geometry

5.3. Electrical Performance Enhancement

6. Conclusions

- Non-uniform surface temperatures on PV panels were observed, with the center points exhibiting temperatures notably higher than the surroundings, reaching a maximum temperature difference of 16.50 °C, attributed to heat transfer;

- PV panels effectively shade and cool the metal roof, resulting in an average surface temperature reduction of 12.90 °C, with peak reductions up to 29.25 °C around noon under intense sunlight;

- Increasing air channel heights correlated with reduced PV panel temperatures, achieving a minimum mean temperature of 65.50 °C and a temperature reduction of 0.41 °C compared to a height of 25 mm. A height of 75 mm was identified as optimal for air channels in PV roofs;

- Similarly, widening the air channels reduced PV panel temperatures, with a width of 400 mm yielding the lowest mean temperature of 65.21 °C and a maximum temperature drop of 0.58 °C compared to a configuration of 75 mm × 250 mm;

- Parametric studies revealed that varying air channel heights had a more pronounced cooling effect compared to width variations. Case A, with varying heights, showed a temperature reduction of 1.47 °C and a reduction rate of 2.11%, whereas Case B, with varying widths, resulted in reductions of 0.87 °C and 1.32%, respectively. This demonstrates better temperature uniformity on PV panels with larger cooling spaces;

- Analysis of the outlet demonstrated significant temperature reduction and air velocity limitations without mechanical ventilation. For instance, the outlet of the air channel with dimensions of 25 mm × 300 mm exhibited a maximum temperature of 55.73 °C and the lowest air velocity of 0.53 m/s. Increasing heights improved heat dissipation, with heights of 75 mm maintaining mean temperatures and velocities at the outlet near 44.20 °C and 1 m/s, similar to inlet velocity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | |

| BAPV | Building Attached Photovoltaic |

| BIPV | Building-Integrated Photovoltaic |

| BIPV/T | Building-Integrated Photovoltaic/thermal |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| PCM | Phase Change Material |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PV/T | Photovoltaic/Thermal |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| STC | Standard Test Conditions |

| Symbols | |

| velocity vector, m/s | |

| specific mass, kg/m3 | |

| kinematic viscosity of fluid, m2/s | |

| force per unit mass, N/kg | |

| temperature, K | |

| thermal conductivity, W/m2·k | |

| viscous dissipation | |

| actual measured value | |

| predicted value. |

References

- Wheeler, V.M.; Kim, J.; Daligault, T.; Rosales, B.A.; Engtrakul, C.; Tenent, R.C.; Wheeler, L.M. Photovoltaic windows cut energy use and CO2 emissions by 40% in highly glazed buildings. One Earth 2022, 5, 1271–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, D.P.; Stehfest, E.; Gernaat, D.E.H.J.; Maarten, V.D.B.; Bijl, D.L.; De Boer, H.S.; Daioglou, V.; Doelman, J.C.; Edelenbosch, O.Y.; Harmsen, M.; et al. Alternative pathways to the 1.5 °C target reduce the need for negative emission technologies. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Ma, X.; Cai, W.; Cai, W.G. Low carbon roadmap of residential building sector in China: Historical mitigation and prospective peak. Appl. Energy 2020, 273, 115247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, A.; Akbari, M. Potential of solar energy in developing countries for reducing energy-related emissions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizuka, G.M.I. Trends in Photovoltaic Applications 2020; IEA Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rajoria, C.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, A.; Singh, D.; Suhag, S. Development of flat-plate building integrated photovoltaic/thermal (BIPV/T) system: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 5342–5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangherini, G.; Diolaiti, V.; Bernardoni, P.; Andreoli, A.; Vincenzi, D. Review of Façade Photovoltaic Solutions for Less Energy-Hungry Buildings. Energies 2023, 16, 6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, A.; Sevinc, H. The energy performance of building integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) by determination of optimal building envelope. Build. Environ. 2021, 199, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khencha, K.; Biara, R.W.; Belmili, H. Techno-economic study of BIPV in typical Sahara region in Algeria. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2020, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetaković, M.; Djordjević, D.; Radojević, M.; Krstić-Furundžić, A.; Burduhos, B.-G.; Martinopoulos, G.; Neagoe, M.; Lobaccaro, G. Photovoltaics on landmark buildings with distinctive geometries. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, S.; Out, D.; Guillevin, N.; Hurtado Ellmann, M.; Ribberink, M.; Valckenborg, R. Outdoor Performance Analysis of Semitransparent Photovoltaic Windows with Bifacial Cells and Integrated Blinds. Sol. RRL 2024, 8, 2400515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, G.; L’Epine, M.d.; Kaizuka, I. Trends in Photovoltaic Applications 2023; IEA Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Shukla, A.K.; Sudhakar, K.; Mamat, R. Experimental exergy analysis of water-cooled PV module. Int. J. Exergy 2017, 23, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, M.K.; Jakhar, S.; Sharma, V. A comparative study on photovoltaic/thermal systems with various cooling methods. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Pei, G.; Yang, M.; Ji, J. Experiment investigation on electrical and thermal performances of a semitransparent photovoltaic/thermal system with water cooling. Int. J. Photoenergy 2014, 2014, 360235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zou, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhang, B.; Wu, X. Temperature effect of photovoltaic cells: A review. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 2675–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohestani, S.S.; Nižetić, S.; Santamouris, M. Comparative review and evaluation of state-of-the-art photovoltaic cooling technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 136953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Kant, K.; Sharma, A.; Biwole, P.H. Cooling methodologies of photovoltaic module for enhancing electrical efficiency: A review. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 160, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, M.; Yousef, M.S.; Huzayyin, A.S. Review of cooling techniques used to enhance the efficiency of photovoltaic power systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 26131–26159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nižetić, S.; Papadopoulos, A.; Giama, E. Comprehensive analysis and general economic-environmental evaluation of cooling techniques for photovoltaic panels, Part I: Passive cooling techniques. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 149, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lu, L.; Yang, H.; Cheng, Y. Thermal regulation of PV façade integrated with thin-film solar cells through a naturally ventilated open air channel. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A.; Zamora, B.; Mazón, R.; García, J.; Vera, F. Experimental study of cooling BIPV modules by forced convection in the air channel. Appl. Energy 2014, 135, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Pande, R.R.; Sharma, S.K.; Kalamkar, V.R. Effect of forced convection cooling on performance of solar photovoltaic module in rooftop applications. In Advances in Energy Research, Volume 1: Selected Papers from ICAER 2017; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, A.; Ali, N.; Bossuyt, J.; Calaf, M.; Cal, R.B. Utility-scale solar PV performance enhancements through system-level modifications. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mays, A.; Ammar, R.; Hawa, M.; Abou Akroush, M.; Hachem, F.; Khaled, M.; Ramadan, M. Improving photovoltaic panel using finned plate of aluminum. Energy Procedia 2017, 119, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Waqas, A.; Ahmad, N.; Mahmood, M.; Shahzad, N.; Sajid, M.B. Thermal management of solar PV module by using hollow rectangular aluminum fins. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2020, 12, 063501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, M.; Abdelhafez, E.; Al Aboushi, A.; Othman, A.; Al-Saleh, S.; Ajib, S. Enhancing PV modules performance using L-shaped aluminum fins. Int. Rev. Mech. Eng. (IREME) 2023, 17, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, M.; Abdelhafez, E.; Musa, A.; Ajib, S. Estimation of Photovoltaic Module Performance with L-Shaped Aluminum Fins Using Weather Data. J. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 25, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeh-e-Sheyda, P.; Rahimi, M.; Parsamoghadam, A.; Masahi, M.M. Using a wind-driven ventilator to enhance a photovoltaic cell power generation. Energy Build. 2014, 73, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Moghaddam, H.; Tkachenko, S.; Yeoh, G.H.; Timchenko, V. A newly designed BIPV system with enhanced passive cooling and ventilation. In Building Simulation; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2023; pp. 2093–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, R.; Haddad, T.; Zayed, M.; Juaidi, A.; Salameh, T. An evaluation of the use of air cooling to enhance photovoltaic performance. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 47, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Han, T. Optimization analysis of flow path arrangement in snake shaped flow path solar air collector. Renew. Energy Resour. 2019, 37, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Tian, Z.; Zhou, B.; Wu, J.; Li, R.; Li, W.; Ma, N.; Kang, J. Experimental research on the convective heat transfer coefficient of photovoltaic panel. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankani, K.; Chaudhry, H.N.; Calautit, J.K. Optimization of an air-cooled heat sink for cooling of a solar photovoltaic panel: A computational study. Energy Build. 2022, 270, 112274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Ahmed, K.; Han, X.; Saleem, A. A novel prediction error-based power forecasting scheme for real pv system using pvusa model: A grey box-based neural network approach. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 87196–87206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddouda, A.; Ihaddadene, R.; Boukhari, A.; Atia, A.; Arıcı, M.; Lebbihiat, N.; Ihaddadene, N. Experimental and numerical modeling of photovoltaic modules temperature under varying ambient conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 312, 118563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangherini, G.; Bernardoni, P.; Baccega, E.; Andreoli, A.; Diolaiti, V.; Vincenzi, D. Design of a ventilated façade integrating a luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic panel. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, S.K.; Elumalai, N.; Natarajan, P.P. Numerical model and experimental validation of the heat transfer in air cooled solar photovoltaic panel. Therm. Sci. 2016, 20, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Dimension | 1650 mm × 991 mm × 35 mm (including frame) |

| Weight | 18 kg |

| Cell | 6 × 10 polycrystalline solar cells |

| Maximum power (W) | 270 (STC) |

| Short circuit current (V) | 9.08 |

| Open circuit voltage (A) | 37.8 |

| Efficiency (%) | 16.5 |

| Temperature coefficients of Pmax | −0.40%/°C |

| Label | Type | Description | Marked |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red-1 | Surface temperature | Front-PV-Near top left | T1 |

| Red-2 | Surface temperature | Front-PV-Near top right | T2 |

| Red-3 | Surface temperature | Front-PV-Middle point | T3 |

| Red-4 | Surface temperature | Front-PV-Near left bottom | T4 |

| Red-5 | Surface temperature | Front-PV-Near right bottom | T5 |

| Red-6 | Air temperature | Around the solar irradiance meter | Tamb |

| Green-7 | Surface temperature | Color steel tile exposed to the sun (without shading) | T7 |

| Green-8 | Surface temperature | Color steel tile inside the inlet of the air channel (with shading) | T8 |

| Green-9 | Surface temperature | Color steel tile inside the outlet of the air channel (with shading) | T9 |

| Red-10 | Surface temperature | Rear-PV-Near top point | T10 |

| Red-11 | Surface temperature | Rear-PV-Middle point | T11 |

| Red-12 | Surface temperature | Rear-PV-Near bottom point | T12 |

| Orange-13 | Air temperature | Inlet of the air channel | T13 |

| Orange-14 | Air temperature | Middle of the air channel | T14 |

| Orange-15 | Air temperature | Outlet of the air channel | T15 |

| Layer | Thickness (mm) | Thermal Conductivity [w/(m·K)] | Density (kg/m3) | Specific Heat Capacity [J/(kg·K)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermally pre-stressed glass | 3.2 | 1.8 | 3000 | 500 |

| EVA | 0.5 | 0.35 | 960 | 2090 |

| Polycrystalline solar cells | 0.2 | 148 | 2330 | 677 |

| Tedlar(PVF) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1200 | 1250 |

| Frame | 35 | 238 | 2700 | 875 |

| Layer | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Thermally pre-stressed glass | Emissivity | 0.88 |

| Absorption coefficient | 26 for <4.25 μm | |

| Polycrystalline solar cells | Refractive index | 1.526 |

| Emissivity | 0.85 for 4.25 μm | |

| Tedlar | Refractive index | 1.45 |

| Number of Elements | Average Temperature of PV (°C) | Maximum Temperature of PV (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| 92,010 | 39.62 | 42.13 |

| 111,300 | 39.70 | 42.13 |

| 164,110 | 39.60 | 42.13 |

| 254,800 | 39.65 | 42.13 |

| 340,380 | 39.57 | 42.13 |

| 426,930 | 39.48 | 42.13 |

| Case | Geometry | Nodes | Elements | Maximum Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 Varying air channel heights | (A) 25 mm | 171990 | 109610 | 0.87673 |

| (B) 35 mm | 195390 | 129200 | 0.95288 | |

| (C) 45 mm | 217815 | 150544 | 0.95288 | |

| (D) 55 mm | 261690 | 194970 | 0.87673 | |

| (E) 65 mm | 284115 | 216310 | 0.87673 | |

| (F) 75 mm | 306540 | 237650 | 0.87673 | |

| Case 2 Varying air channel widths | (A) 200 mm | 348860 | 268300 | 0.97906 |

| (B) 250 mm | 343200 | 263060 | 0.95361 | |

| (C) 300 mm | 306540 | 237650 | 0.87673 | |

| (D) 350 mm | 356660 | 274320 | 0.96273 | |

| (E) 400 mm | 405800 | 312920 | 0.96779 |

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | Taverage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 0.30 °C | 0.27 °C | 0.16 °C | 0.23 °C | 0.20 °C | 0.24 °C |

| Solar Radiation (W/m2) | Panel Temperature (°C) | Power Output (W) | Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1100 (as boundary conditions) | 67.02 | 335.98 | 10.75% |

| 734 (Min) | 56.60 | 216.06 | 10.36% |

| 726 (Max) | 72.80 | 353.44 | 10.15% |

| 737 | 55.89 (Min) | 218.74 | 9.53% |

| 1185 | 73.04 (Max) | 320.56 | 10.45% |

| 734 | 56.60 | 216.06 (Min) | 10.36% |

| 1200 | 72.69 | 361.68 (Max) | 10.61% |

| 837 | 56.60 | 216.06 | 9.34% (Min) |

| 995 | 68.50 | 326.92 | 11.31% (Max) |

| Geometry | Average Velocity (m/s) | Maximum Velocity (m/s) | Average Temperature (°C) | Maximum Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 mm × 300 mm | 0.53 | 1.34 | 53.73 | 59.70 |

| 35 mm × 300 mm | 0.65 | 1.31 | 49.84 | 59.40 |

| 45 mm × 300 mm | 0.72 | 1.35 | 47.59 | 59.80 |

| 55 mm × 300 mm | 1.00 | 1.34 | 45.82 | 61.17 |

| 65 mm × 300 mm | 1.00 | 1.30 | 44.63 | 61.18 |

| 75 mm × 300 mm | 1.00 | 1.27 | 44.20 | 62.26 |

| Geometry | Average Velocity (m/s) | Maximum Velocity (m/s) | Average Temperature (°C) | Maximum Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 mm × 200 mm | 1.00 | 1.27 | 44.20 | 61.67 |

| 75 mm × 250 mm | 1.00 | 1.27 | 44.20 | 61.97 |

| 75 mm × 300 mm | 1.00 | 1.27 | 44.20 | 62.26 |

| 75 mm × 350 mm | 1.00 | 1.27 | 44.20 | 61.97 |

| 75 mm × 400 mm | 1.00 | 1.27 | 44.20 | 61.97 |

| Case | Geometry | Average Temperature of PV (°C) | Power Output (W) | Efficiency (%) | Influence Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 25 mm × 300 mm | 66.97 | 309.99 | 10.84% | −0.47% |

| 35 mm × 300 mm | 66.72 | 312.85 | 10.94% | −0.37% | |

| 45 mm × 300 mm | 66.62 | 313.99 | 10.98% | −0.33% | |

| 55 mm × 300 mm | 65.89 | 322.34 | 11.27% | −0.04% | |

| 65 mm × 300 mm | 65.70 | 324.52 | 11.35% | 0.04% | |

| 75 mm × 300 mm | 65.50 | 326.81 | 11.43% | 0.12% | |

| B | 75 mm × 200 mm | 66.08 | 320.17 | 11.19% | −0.12% |

| 75 mm × 250 mm | 65.79 | 326.92 | 11.31% | Measured value | |

| 75 mm × 300 mm | 65.50 | 326.81 | 11.43% | 0.12% | |

| 75 mm × 350 mm | 65.37 | 328.29 | 11.48% | 0.17% | |

| 75 mm × 400 mm | 65.21 | 330.12 | 11.54% | 0.23% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y. Optimization Study of Air-Based Cooling Photovoltaic Roofs: Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051168

He Y, Xue Y, Zhang Y. Optimization Study of Air-Based Cooling Photovoltaic Roofs: Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Energies. 2025; 18(5):1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051168

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yi, Yibing Xue, and Yingge Zhang. 2025. "Optimization Study of Air-Based Cooling Photovoltaic Roofs: Experimental and Numerical Analysis" Energies 18, no. 5: 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051168

APA StyleHe, Y., Xue, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Optimization Study of Air-Based Cooling Photovoltaic Roofs: Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Energies, 18(5), 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051168