Energy Cooperatives as an Instrument for Stimulating Distributed Renewable Energy in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Energy Cooperatives

2.2. Cooperatives as a Method of Solving Energy Problems

- Voluntary and open membership—they are voluntary organizations available to all people who can use their services and are ready to accept the obligations of membership;

- Democratic member control—these are democratic organizations controlled by their members, who actively participate in setting rules and making decisions;

- Autonomy and independence—they are autonomous, self-help organizations controlled by their members;

- Education, training, and information—cooperatives provide education and training for their members, elected representatives, managers, and employees so that they can effectively contribute to the development of the cooperative;

- Care for the community—the goals of the cooperative are consistent with those regarding the sustainable development of local communities.

- Inspiring rural residents to undertake cooperative activities;

- Promoting the social role of cooperative forms of management;

- Substantive support for cooperative members aimed not only at increasing their awareness of the use of renewable energy sources but also at improving the cooperative management system in a competitive market.

2.3. Legal Aspects of the Organization and Functioning of Energy Cooperatives in Poland

3. Methodology

- The assessment of the state of legal regulations in the field of energy cooperatives;

- The identification of features enabling the assessment of the nature and current situation of energy cooperatives and their division into groups showing their development potential;

- The identification of factors influencing the development of energy cooperatives in Poland.

4. Research Results and Discussion

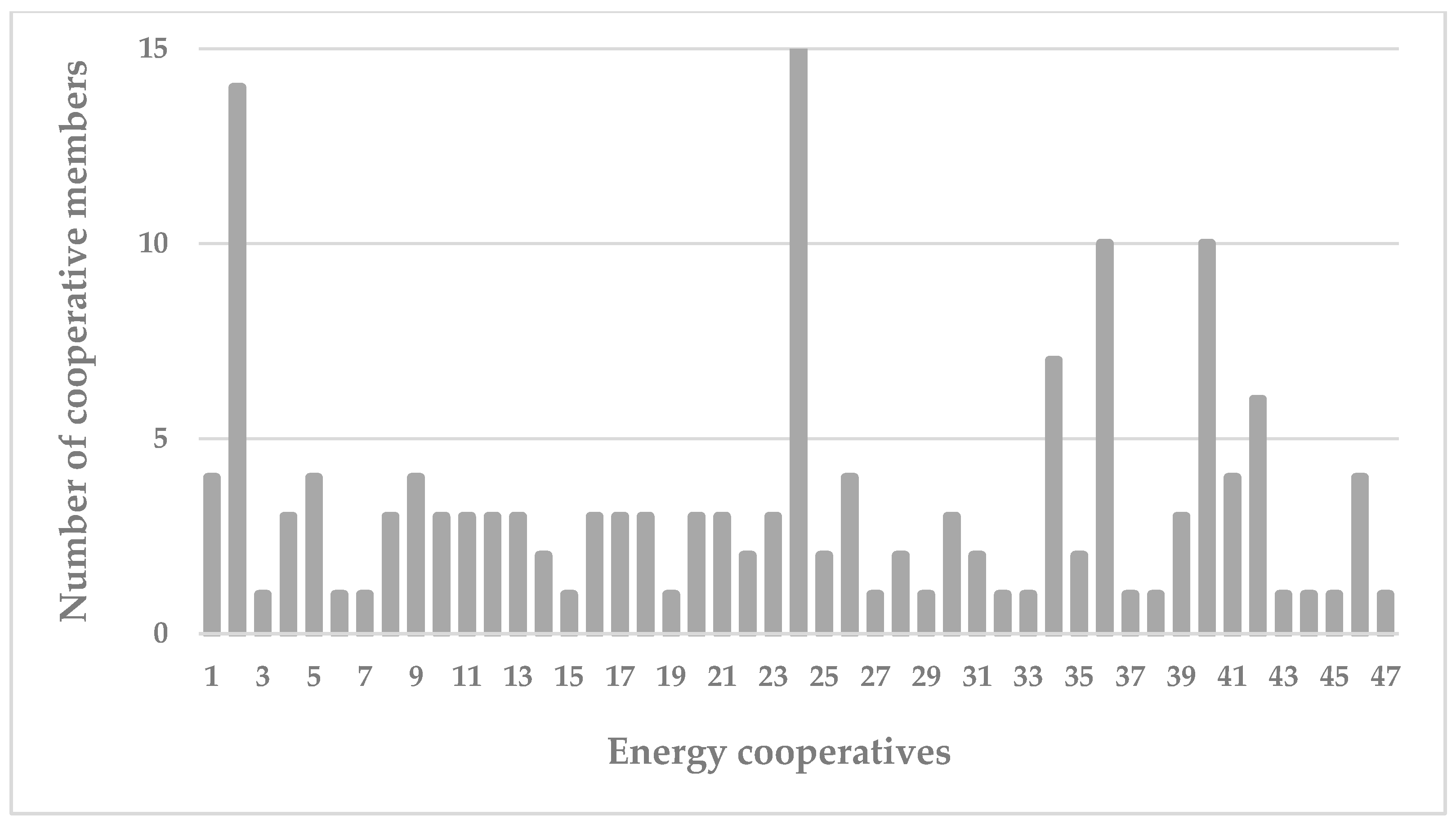

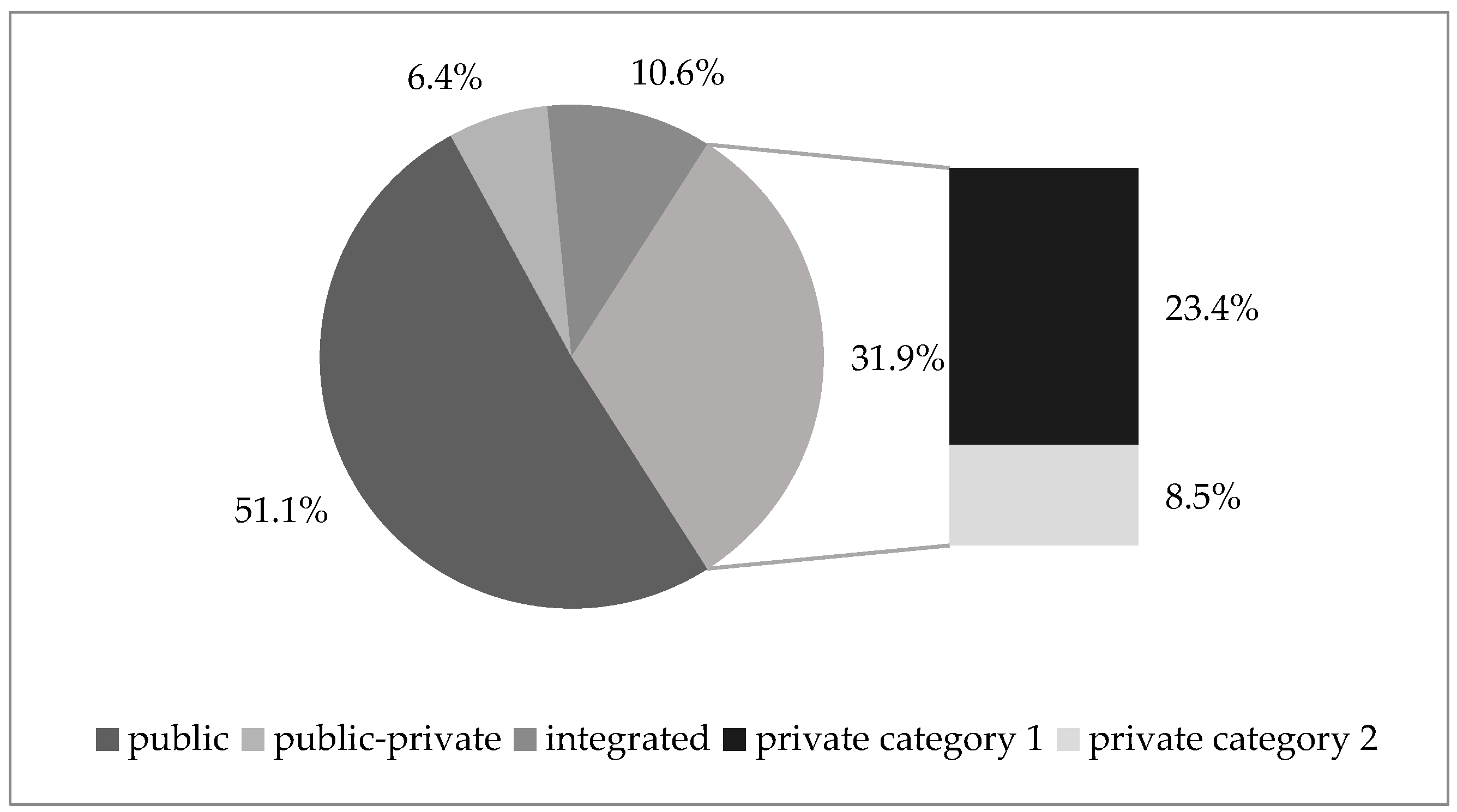

- The type of entities included in the cooperative—among those participating in the research were cooperatives of local government units (public entities), cooperatives of private entities, and public–private entities, as well as cooperatives of integrated entities, i.e., those that were established as the next stage of cooperation, e.g., social cooperatives, producer groups, etc.;

- The creation procedure and/or management method—in this case, we can distinguish between energy cooperatives that were established and managed by external entities (most often, they were companies providing consulting services) and cooperatives created and managed bottom-up by cooperative members themselves;

- The method of operation—four groups of cooperatives can be distinguished: leaders, i.e., developing cooperatives and producing and settling energy; active cooperatives, which are at various stages of development but have a vision and human resources to achieve their adopted goals; and cooperatives in stagnation and cooperatives at risk of collapse.

- Cooperatives established by private entities that are energy producers, which, due to limited sales opportunities (such as power plant shutdowns during the summer period), lose the potential to increase revenue through this form of cooperation (category 1).

- Cooperatives involving one or several business entities collaborating with individuals (category 2).

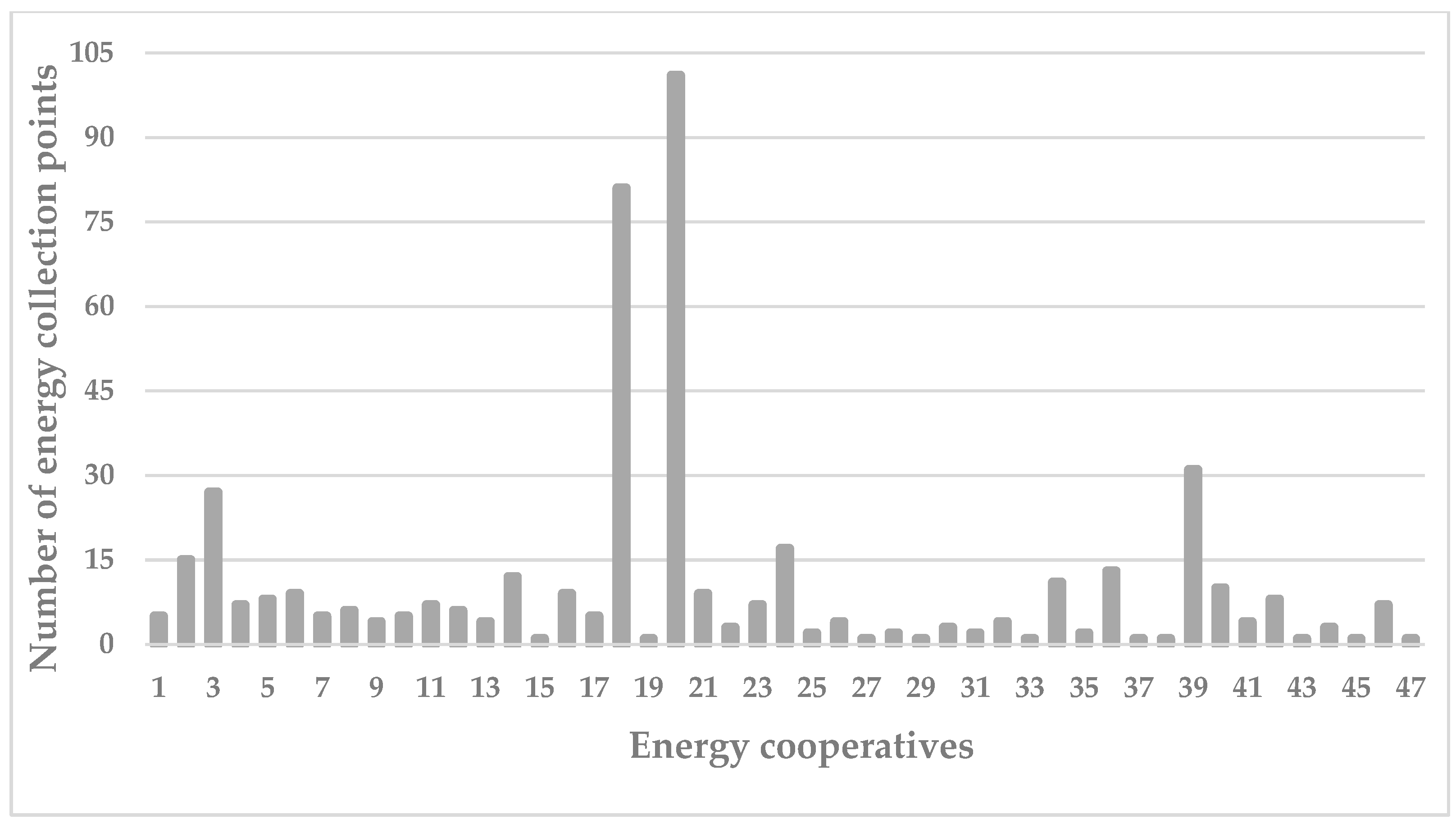

- The number of collection points;

- The development stage (functioning on the market, implemented billing system, and energy);

- Investment plans, mainly in the field of the diversification of renewable energy sources and the scope of services provided;

- Human capital (experience in the field of renewable energy and conducting cooperative initiatives);

- The pro-social nature of the project.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatzistamoulou, N.; Koundouri, P. Is Green Transition in Europe Fostered by Energy and Environmental Efficiency Feedback Loops? The Role of Eco-Innovation, Renewable Energy and Green Taxation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 87, 1445–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.K.; Gozgor, G.; Mahalik, M.K.; Patel, G.; Li, J. Introducing a New Measure of Energy Transition: Green Quality of Energy Mix and Its Impact on CO2 Emissions. Energy Econ. 2023, 122, 106702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, E. The Energy Transition in the Visegrad Group Countries. Energies 2021, 14, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozowska, S.; Wendt, J.A.; Tomaszewski, K. The Challenges of Poland’s Energy Transition. Energies 2021, 14, 8165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bórawski, P.; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A.; Holden, L.; Rokicki, T. The Role of Renewable Energy Sources in Electricity Production in Poland and the Background of Energy Policy of the European Union at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Crisis. Energies 2022, 15, 8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suproń, B.; Łącka, I. Research on the Relationship between CO2 Emissions, Road Transport, Economic Growth and Energy Consumption on the Example of the Visegrad Group Countries. Energies 2023, 16, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łącka, I.; Suproń, B.; Śmietański, R. Effects of Social and Economic Development on CO2 Emissions in the Countries of the Visegrad Group. Energies 2024, 17, 5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEO Rynek Fotowoltaiki w Polsce 2024. Available online: https://ieo.pl/raporty (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Gajdecka, D.; Kiełboń, M. Opłacalność Prosumenckich Mikroinstalacji Fotowoltaicznych w Aspekcie Zastosowania Polskich Programów Wsparcia—Rynek Energii—Tom Nr 3 (2021)—BazTech—Yadda. Rynek Energii 2021, 3, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, M.; Majewski, J.; Sobolewska, A.; Stawicka, E.; Suchoń, A. Wybrane Ekonomiczne i Prawne Aspekty Wytwarzania Energii z Instalacji Fotowoltaicznych w Gospodarstwach Rolnych Województwa Mazowieckiego; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; ISBN 978-83-8237-119-2. [Google Scholar]

- Burzyńska, D. Dylematy Atrakcyjności Inwestycji Podmiotów Prywatnych w Odnawialne Źródła Energii. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2023, 67, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryszk, H.; Kurowska, K.; Marks-Bielska, R.; Bielski, S.; Eźlakowski, B. Barriers and Prospects for the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland during the Energy Crisis. Energies 2023, 16, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutel, B.; Pierzyńska, A.; Dębowski, M.; Bukowski, P.; Dyjakon, A. Assessment of Energy Storage from Photovoltaic Installations in Poland Using Batteries or Hydrogen. Energies 2020, 13, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Poland Electricity Security Policy—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/articles/poland-electricity-security-policy (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Skotarek, K. Problemy Rozwoju Infrastruktury Przesyłowej w Elektroenergetyce. Myśl Ekon. Polit. 2023, 76, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Andruszków, E. Mapping Renewable Energy Sources Potential, Challenges, and Opportunities in Poland. Available online: https://www.euki.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Mapping-Renewable-Energy-Sources-potential-challenges-and-opportunities-in-Poland.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Kocór, M.; Worek, B.; Micek, D.; Lisek, K.; Szczucka, A. Społeczny Wymiar Rozwoju Energetyki Rozproszonej w Polsce—Kluczowe Czynniki i Wyzwania. Energetyka Rozproszona 2021, 5, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarski, S. Priorytety Transformacji Energetyki Na Początku 2024 r. Nowa Energ. 2024, 1, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kostecka-Jurczyk, D.; Marak, K.; Struś, M. Economic Conditions for the Development of Energy Cooperatives in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecka-Jurczyk, D.; Struś, M.; Marak, K. The Role of Energy Cooperatives in Ensuring the Energy and Economic Security of Polish Municipalities. Energies 2024, 17, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Rational Choice Theory. In Understanding Contemporary Society: Theories of the Present; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2000; pp. 126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Herfeld, C. The Diversity of Rational Choice Theory: A Review Note. Topoi 2018, 39, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chustecki, J. Rational Choice Theory in Light of Biopolitics. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. K—Politol. 2023, 30, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepański, M.; Wojtkun, J.; Śliz, A. Teoria Wymiany Społecznej. In Współczesne Teorie Społeczne: W Kręgu Ujęć Paradygmatycznych; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego: Opole, Poland, 2014; pp. 107–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, D.M. Philosophy of Economics. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: San Diego, CA, USA, 1961; ISBN UOM:39015000670094. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Wymiana Społeczna. In Współczesne Teorie Socjologiczne. Tom 1; Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2006; pp. 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Szykuła-Piec, B. Propozycja Zastosowania Wybranych Elementów Teorii Wymiany w Celu Identyfikacji Procesów Integracji Społecznej w Kontekście Kształtowania Bezpieczeństwa. Zesz. Nauk. SGSP 2018, 68, 277–290. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.H. Struktura Teorii Socjologicznej, 1st ed.; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; p. 314. ISBN 8301140720. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Perspektywa Racjonalnego Wyboru w Socjologii Ekonomicznej. In Współczesne Teorie Socjologiczne; Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2006; pp. 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Shucksmith, M. Endogenous Development, Social Capital and Social Inclusion: Perspectives from Leader in the UK. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M. The Place of Social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic Outcome. Can. J. Policy Res. 2001, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Storberg, J. The Evolution of Capital Theory: A Critique of a Theory of Social Capital and Implications for HRD. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2002, 1, 468–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak, T.; Rymsza, M. (Eds.) Kapitał Społeczny: Ekonomia Społeczna; Instytut Spraw Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2007; ISBN 978-83-89817-17-4. [Google Scholar]

- Robison, L.J.; Schmid, A.A.; Siles, M.E. Is Social Capital Really Capital? Rev. Soc. Econ. 2002, 60, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuberer, J. Social Capital Theory: Towards a Methodological Foundation; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-531-17626-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brummer, V. Of Expertise, Social Capital, and Democracy: Assessing the Organizational Governance and Decision-Making in German Renewable Energy Cooperatives. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 37, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geskus, S.; Punt, M.B.; Bauwens, T.; Corten, R.; Frenken, K. Does Social Capital Foster Renewable Energy Cooperatives? J. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 24, 887–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Teasdale, S. Ekonomia Spoleczna, Przedsiebiorstwo Spoleczne i Teoria Demokracji Stowarzyszeniowej. Ekonomia Społeczna. Ekon. Społeczna 2011, 2, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Szulecki, K.; Overland, I. Energy Democracy as a Process, an Outcome and a Goal: A Conceptual Review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 9780804747899. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Collaboration and Partnerships in Tourism Planning. In Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships. Politics, Pracitice and Sustainability; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2000; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pulit, M. Socjologiczne Teorie Konfliktu i Wymiany w Pryzmacie Konstruowania Interakcji Społecznych—Eruditio et Ars—Volume 5, Issue 2 (2022)—CEJSH—Yadda. Erud. Ars 2022, 5, 150–168. [Google Scholar]

- Tsasis, P. The Social Processes of Interorganizational Collaboration and Conflict in Nonprofit Organizations. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2009, 20, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbroińska, B. Wkład Ekonomii Kosztów Transakcyjnych i Teorii Kontraktów Do Nauki o Zarządzaniu. Stud. I Materiały. Misc. Oeconomicae 2013, 17, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bentkowska, K. Optymalizacja Kosztów Transakcyjnych Jako Sposób Na Podniesienie Konkurencyjności Przedsiębiorstw. Kwart. Nauk. Przedsiębiorstwie 2020, 57, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economic Intstitutions of Capitalism; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 9780684863740. [Google Scholar]

- Landreth, H.; Colander, D.C. Historia Myśli Ekonomicznej; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2005; ISBN 8301144726. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, P.A. Community and Cooperation: The Evolution of Cooperatives Towards New Models of Citizens’ Democratic Participation in Public Services Provision. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2014, 85, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Energy Transition Can Save Democracy. Available online: https://www.ews-schoenau.de/energiewende-magazin/zum-glueck/the-energy-transition-can-save-democracy/ (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Holstenkamp, L. The Rise and Fall of Electricity Distribution Cooperatives in Germany. SSRN Electron. J. 2015, 22, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeliou, N.; Balkanski, Y.; Cozic, A.; Hao, W.M.; Møller, A.P. Wildfires in Chernobyl-Contaminated Forests and Risks to the Population and the Environment: A New Nuclear Disaster about to Happen? Environ. Int. 2014, 73, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neureiter, N.P.; Garrick, B.J.; Bari, R.A.; Beard, J.; Percy, M.; Brewster, M.Q.; Corradini, M.L. Lessons Learned from the Fukushima Nuclear Accident for Improving Safety of U.S. Nuclear Plants; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; ISBN 030927253X. [Google Scholar]

- Puławski, Ł.M.; Żuchowski, I. Spółdzielczość Rolnicza Jako Czynnik Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich. In Czynniki Rozwoju Rynku Odnawialnych Źródeł Energii i Obszarów Wiejskich w Polsce; Wydawnictwo Ostrołęckiego Towarzystwa Naukowego im. Adama Chętnika: Ostrołęka, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens, T.; Gotchev, B.; Holstenkamp, L. What Drives the Development of Community Energy in Europe? The Case of Wind Power Cooperatives. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, Ö.; Rommel, J.; Debor, S.; Holstenkamp, L.; Mey, F.; Müller, J.R.; Radtke, J.; Rognli, J. Renewable Energy Cooperatives as Gatekeepers or Facilitators? Recent Developments in Germany and a Multidisciplinary Research Agenda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punt, M.B.; Bauwens, T.; Frenken, K.; Holstenkamp, L. Institutional Relatedness and the Emergence of Renewable Energy Cooperatives in German Districts. Reg. Stud. 2021, 56, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CATF Clean Energy from the Ground Up: Energy Communities in the European Union—Clean Air Task Force. Available online: https://www.catf.us/resource/clean-energy-ground-up-energy-communities-european-union/ (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Schwanitz, V.J.; Wierling, A.; Arghandeh Paudler, H.; von Beck, C.; Dufner, S.; Koren, I.K.; Kraudzun, T.; Marcroft, T.; Mueller, L.; Zeiss, J.P. Statistical Evidence for the Contribution of Citizen-Led Initiatives and Projects to the Energy Transition in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błażejowska, M.; Gostomczyk, W. Warunki Tworzenia i Stan Rozwoju Spółdzielni i Klastrów Energetycznych w Polsce Na Tle Doświadczeń Niemieckich. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW W Warszawie—Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2018, 18, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzwa, D. Miejsce Sektora Spółdzielczego w Gospodarce Narodowej Polski. Rocz. Nauk. Rolniczych. Ser. G Ekon. Rolnictwa 2010, 97, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrzykowska, B. Trendy i Zmiany Strukturalne w Spółdzielczości. Zagadnienia Doradz. Rol. 2014, 1, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, P.; Gorlach, K. Rolnicy i Spółdzielczość w Polsce: Stary Czy Nowy Ruch Społeczny? Wieś Rol. 2015, 1, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- All Nobel Prizes. 2024. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/all-nobel-prizes-2024/ (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Klimatu i Środowiska z Dnia 23 Marca 2022 r. w Sprawie Dokonywania Rejestracji, Bilansowania i Udostępniania Danych Pomiarowych Oraz Rozliczeń Spółdzielni Energetycznych, (Dz. U. 2022 Poz. 703). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20220000703/O/D20220703.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Ustawa z Dnia 20 Lutego 2015 r. o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii, t.j. (Dz. U. 2024, Poz. 1361). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20240001361/T/D20241361L.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Ustawa z Dnia 16 Września 1982 r.—Prawo Spółdzielcze (Dz. U. 2021, Poz. 648 i Dz. U. 2023, Poz. 1450). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20210000648/U/D20210648Lj.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Ustawa z Dnia 4 Października 2018 r. o Spółdzielniach Rolników (Dz. U. 2018, Poz. 2073 i Dz. U. 2023, Poz. 1681 i 1762). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20180002073/T/D20182073L.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Augustyńska, I.; Błażejowska, M.; Brodzińska, K.; Brodziński, Z.; Stolarska, A. Obszary Wiejskie w Polsce—Współczesne Wyzwania i Możliwości Rozwoju; Oficyna Wydawnicza ASPRA-JR: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-8209-288-2. [Google Scholar]

- Marzec, T. Prawne Perspektywy Rozwoju Spółdzielni Energetycznych w Polsce. Internetowy Kwart. Antymonop. I Regul. 2021, 10, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Recast) PE/48/2018/REV/1OJ L 328; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2018; pp. 82–209.

- Maison, D. Jakościowe Metody Badań Społecznych. Podejście Aplikacyjne; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; ISBN 978-83-01-22253-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, M.U. Hypothetico-Deductive Method: A Comparative Analysis. J. Basic Appl. Res. Int. 2015, 7, 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Siagian, F.E. The Principles of Four Basic Steps of Scientific Stage: Problem, Hypothesis, Trial, Report. Asian J. Adv. Res. Rep. 2023, 17, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nola, R.; Sankey, H. Theories of Scientific Method: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781317493488. [Google Scholar]

- Caramizaru, E.; Uihlein, A. Energy Communities: An Overview of Energy and Social Innovation. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC119433 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Orłowska, J.; Trembaczowski, Ł. Spółdzielnie Energetyczne w Polsce. Społeczne Uwarunkowania Ich Powstawania. Available online: http://bomiasto.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Spoldzielnie-energetyczne-w-Polsce.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Suchoń, A.; Marzec, T. (Eds.) Energy Cooperatives in Selected Countries of the World. Legal and Economic Aspects; Adam Mickiewicz University Press: Poznań, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-232-4171-3. [Google Scholar]

- Chyra-Rolicz, Z. Rola Lidera Społecznego w Tworzeniu Lepszej Jakości Życia. Nierówności Społeczne a Wzrost Gospod. 2020, 64, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Providing Clean Energy and Energy Access Through Cooperatives; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Duvignau, R.; Heinisch, V.; Göransson, L.; Gulisano, V.; Papatriantafilou, M. Benefits of Small-Size Communities for Continuous Cost-Optimization in Peer-to-Peer Energy Sharing. Appl. Energy 2021, 301, 117402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodziński, Z.; Brodzińska, K.; Szadziun, M. Photovoltaic Farms—Economic Efficiency of Investments in North-East Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, D.; Circuit, G. Australian Government Support for Renewable Energy. In Sixteenth European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 2760–2763. [Google Scholar]

- Soltek Energy Relief for Solar. Available online: https://www.soltekenergy.com.au/rebates/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Koukoufikis, G.; Schockaert, H.; Paci, D.; Filippidou, F.; Caramizaru, A.; Della Valle, N.; Candelise, C.; Murauskaite-Bull, I.; Uihlein, A. Energy Communities and Energy Poverty; European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arnould, J.; Quiroz, D. Energy Communities in the EU: Opportunities and Barriers to Financing; Profundo: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hanzelka, Z.; Skomudek, W. Strategia Rozwoju Energetyki Rozproszonej w Polsce Do 2040 Roku—Obszar Techniczno-Technologiczny. Energetyka Rozproszona 2022, 8, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.J.; Azarova, V.; Kollmann, A.; Reichl, J. Preferences for Community Renewable Energy Investments in Europe. Energy Econ. 2021, 100, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, J.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Sołtysik, M. Determinants of Energy Cooperatives’ Development in Rural Areas—Evidence from Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdzik, B.; Jaciow, M.; Wolniak, R.; Wolny, R.; Grebski, W.W. Diagnosis of the Development of Energy Cooperatives in Poland—A Case Study of a Renewable Energy Cooperative in the Upper Silesian Region. Energies 2024, 17, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MDDP Tax Challenges for Renewable-Energy Sector Investors in Poland. Available online: https://bpcc.org.pl/tax-challenges-for-renewable-energy-sector-investors-in-poland/ (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Orłowska, J.; Suchacka, M.; Trembaczowski, Ł.; Ulewicz, R. Social Aspects of Establishing Energy Cooperatives. Energies 2024, 17, 5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capellán-Pérez, I.; Campos-Celador, Á.; Terés-Zubiaga, J. Renewable Energy Cooperatives as an Instrument towards the Energy Transition in Spain. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delicado, A.; Pallarès-Blanch, M.; García-Marín, R.; del Valle, C.; Prados, M.-J. David against Goliath? Challenges and Opportunities for Energy Cooperatives in Southern Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 103, 103220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodziński, Z. Rola Doradców Publicznych Jednostek Doradztwa Rolniczego w Rozwoju Spółdzielczych form Działalności Gospodarczej i Społecznej Na Obszarach Wiejskich. In Spółdzielczość w Świadomości Rolników i Doradców Oraz Praktyczne Wykorzystywanie Idei Spółdzielczej do Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości na Obszarach Wiejskich; Centrum Doradztwa Rolniczego w Brwinowie: Kraków, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leśniak, L. (Ed.) Rola i Znaczenie Doradztwa Publicznego w Wykorzystaniu Idei Spółdzielczej Do Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości Na Obszarach Wiejskich; Centrum Doradztwa Rolniczego w Brwinowie, Oddział w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Czternasty, W. The Position of Cooperatives in the New Social Economy. Management 2014, 18, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z Dnia 10 Kwietnia 1997 r. Prawo Energetyczne t.j. (Dz. U. 2024, Poz. 266, 834, 859). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20240000266/U/D20240266Lj.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity and Amending Directive 2012/27/EU (recast) PE/10/2019/REV/1 OJ L 158; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2019; pp. 125–199.

- Directive (EU) 2023/2413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 Amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as Regards the Promotion of Energy from Renewable Sources, and Re-Pealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652 PE/36/2023/REV/2 OJ L; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2023.

- Ustawa z Dnia 11 września 2019 r. Prawo zamówień publicznych (Dz.U. 2019, Poz.2019 z Późn.zm.). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20190002019/T/D20192019L.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

| Legal Regulations Before the Amendment | Legal Regulations as Amended |

|---|---|

| No ability to trade energy among cooperative members. | Expanded scope to include energy trading and storage |

| Maximum of 1000 members allowed | Removal of the 1000 member limit |

| No option to integrate multiple energy sources (natural gas, agricultural biogas, biomethane) into a single distribution system | Expansion of the area of activity of energy cooperatives to include agricultural biogas or biomethane |

| No preferential treatment for grid connection | Introduction of mandatory grid connection |

| No specified deadline for concluding agreements with grid operators | Obligatory agreements with grid operators within 90 days |

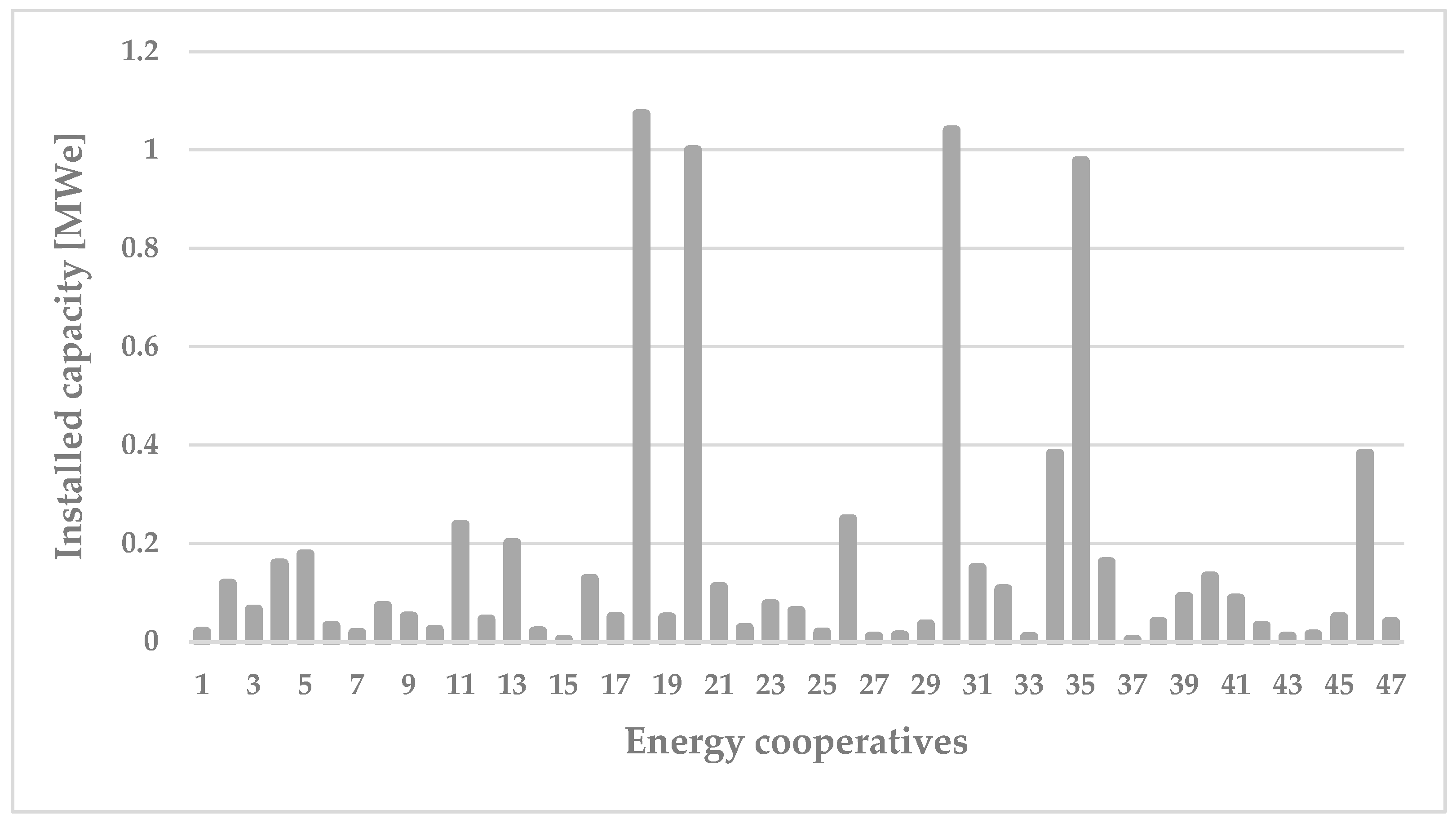

| The total installed capacity of renewable energy systems must cover at least 70% of the cooperative’s and its members’ annual needs and not exceed 10 MWe | Transition period until 31 December 2025, with a reduced requirement of 40% |

| No obligation or timeframe for meter installation | Mandatory installation of a remote meter within 4 months |

| Year of Registration | Number of Cooperatives | Total Installed Capacity at Disposal [MWe] |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2 | 0.138 |

| 2022 | None | NA |

| 2023 | 19 | 3.521 |

| 2024 | 26 | 4.203 |

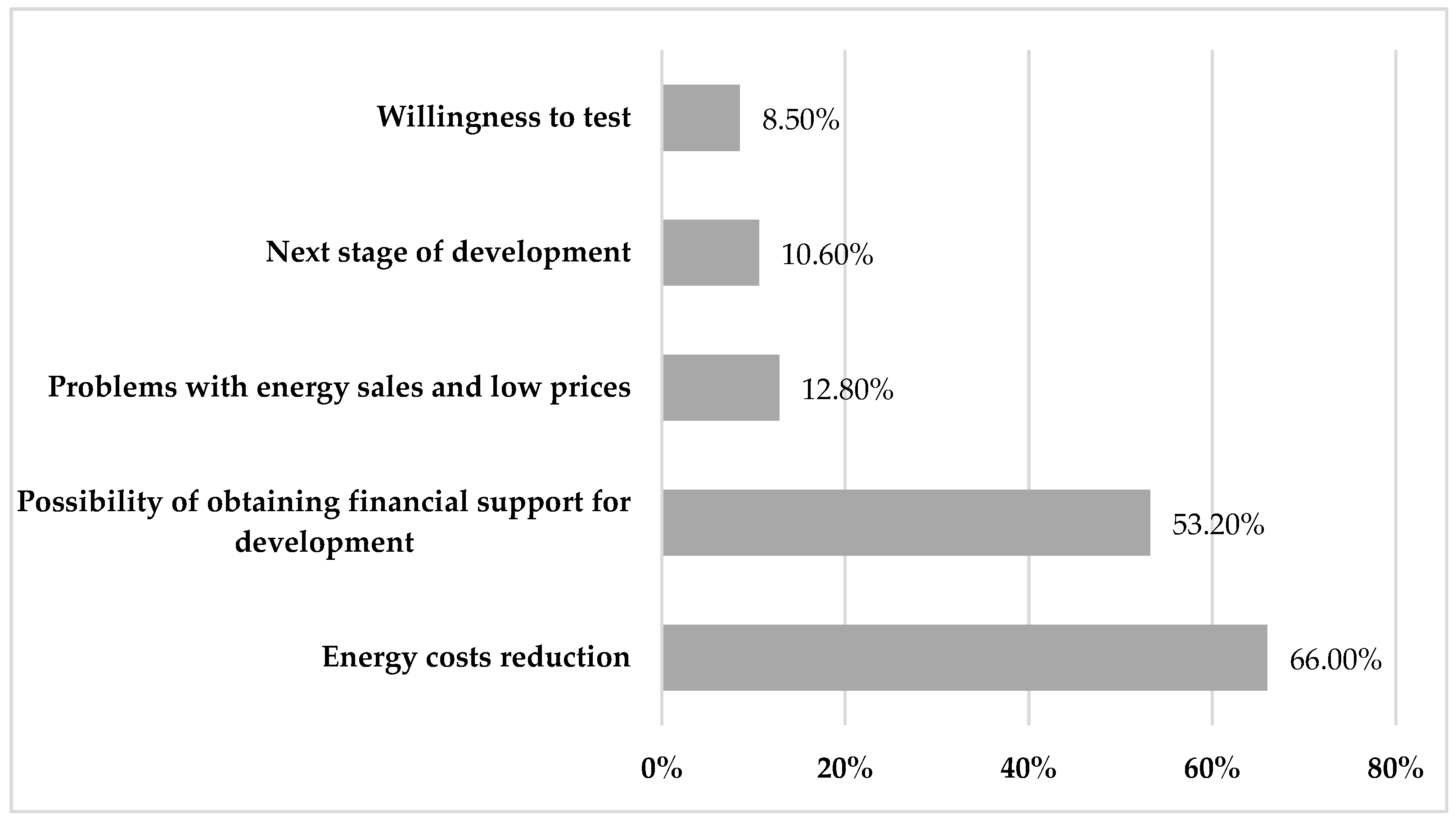

| Specification | Characteristic | Share [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Leaders | Cooperatives with multiple installations and consumption points, active in the market, with an implemented energy settlement system, they have investment plans regarding both the diversification of energy sources and the scope of services provided. | 10.6 |

| Active/development cooperatives | This group includes cooperatives that have professional management staff and promising business plans. These cooperatives pursue both business and social goals. Their further development is limited by lack of capital. | 44.7 |

| Cooperatives in stagnation | These are cooperatives that were most often initiated by external entities, and their members do not really identify with them. They are characterized by a survival orientation, lack of decision-making on the part of members, no idea for further operation, and lack of capital. | 36.2 |

| Cooperatives at risk of collapse | This group includes not only cooperatives in a state of bankruptcy but also those that do not have the nature of business ventures, and it is difficult to consider the adopted goals to be of a social nature. | 8.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brodzińska, K.; Błażejowska, M.; Brodziński, Z.; Łącka, I.; Stolarska, A. Energy Cooperatives as an Instrument for Stimulating Distributed Renewable Energy in Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040838

Brodzińska K, Błażejowska M, Brodziński Z, Łącka I, Stolarska A. Energy Cooperatives as an Instrument for Stimulating Distributed Renewable Energy in Poland. Energies. 2025; 18(4):838. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040838

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrodzińska, Katarzyna, Małgorzata Błażejowska, Zbigniew Brodziński, Irena Łącka, and Alicja Stolarska. 2025. "Energy Cooperatives as an Instrument for Stimulating Distributed Renewable Energy in Poland" Energies 18, no. 4: 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040838

APA StyleBrodzińska, K., Błażejowska, M., Brodziński, Z., Łącka, I., & Stolarska, A. (2025). Energy Cooperatives as an Instrument for Stimulating Distributed Renewable Energy in Poland. Energies, 18(4), 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040838