4.1. PCA

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to calculate composite indicators of digitalization and energy to avoid multicollinearity and to reduce the number of parameters that will be used in Path Analysis. Before conducting PCA, several diagnostic procedures were performed to ensure that the data met the key statistical assumptions for multivariate analysis. First, the univariate normality of all variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Because PCA is based on the covariance (or correlation) structure, substantial departures from normality can bias the estimation of principal components. The Shapiro–Wilk statistic was calculated for each variable to test the null hypothesis of normal distribution. Variables with p-values below 0.05 were considered to deviate from normality. Although PCA has generally robust-to-moderate non-normality, this step provided an important diagnostic for identifying variables that did not meet the normality assumption and were therefore logarithmically transformed to achieve normality. Logarithmic transformation was applied to the following variables: Energy productivity (log_E13), Gross electricity production/GDP (log_E3), Residential electricity consumption/GDP (log_E5), Industrial electricity consumption/GDP (log_E6), Share of renewable energy consumption (log_E7), Employed ICT specialists (log_D4), Total number of people receiving education (log_D10), Business enterprise R&D expenditure in high-tech sectors/GDP (log_D11), and Number of patent applications (log_D19).

After addressing issues of univariate non-normality, the dataset was further examined for multivariate outliers, which can disproportionately affect covariance estimates and, consequently, the orientation of principal components. For this purpose, the Minimum Covariance Determinant (MCD) method [

60] was employed. In this study, the detection was performed using the leverage diagnostics option, which identifies influential cases based on robust leverage values. According to the results, Ireland was identified as a multivariate outlier for PCA, so it was removed from the dataset.

In PCA, each principal component (factor) is expressed as a linear combination of the observed variables weighted by their respective coefficients. The general form of the

-th component is

where

is the

i-th principal component (factor score),

represents the original observed variable

j,

denotes the coefficient (loading weight) of the variable

for component

i, and

p is the total number of variables.

To select variables suitable for the Principal Component Analysis (PCA), we examined the overall Kaiser’s Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA). This measure indicates whether the analyzed data are appropriate for applying factor analysis. If the value of this measure is below 0.6, the correlations between variable pairs cannot be explained by other variables, and factor analysis is therefore not applicable. In our final models, the overall MSA value exceeded 0.7 for all the years under study, which confirms that the available data are suitable for conducting factor analysis.

In addition, we examined the individual MSA for each variable, which indicates whether a variable should be included in the factor analysis. If the value of this measure is below 0.5, the variable is recommended to be excluded. Therefore, only those variables with an MSA value greater than 0.5 were included in the analysis. Based on these criteria, separate PCAs were conducted for the energy and digitalization parts.

To determine how many factors could be retained, the eigenvalues of the correlation matrix were evaluated. According to the Kaiser criterion, only the factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained for further analysis. For both the energy and digitalization parts, two factors were extracted, indicating that the data structure could be effectively represented by two latent dimensions in each case. Furthermore, we examined the proportion of total variance explained by the extracted factors and the Final Communality Estimates, which indicate the proportion of each variable’s variance explained by the retained factors (i.e., the common variance). The obtained results demonstrated that the extracted factors accounted for a substantial share of the total variance (all cases more than 0.5), confirming the adequacy and interpretability of the factor solutions.

PCA was conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) extraction method, which allows estimation of the underlying factor structure that best reproduces the observed covariance matrix. This method was chosen because it provides statistical measures of model fit and enables the evaluation of factor loadings’ significance, offering greater inferential flexibility compared to others. To enhance the interpretability of the extracted components, orthogonal Varimax rotation was applied. The Varimax procedure maximizes the variance of squared loadings within each component, thereby achieving a simpler and more interpretable factor structure where each variable tends to load highly on one factor and minimally on others.

The rotated factor loadings represent the correlations between the observed variables and the extracted components, showing how strongly each variable contributes to a particular factor. Loadings close to ±1 indicate a strong association, while loadings near 0 suggest little or no relationship. For interpretation purposes, rotated loadings in our case were used. Typically, loadings with absolute values above 0.70 are considered very strong, 0.50–0.69 as moderate, and 0.30–0.49 as weak but meaningful contributions [

61]. Each factor was interpreted and named based on the variables with the highest loadings, assuming that such variables share a common conceptual dimension.

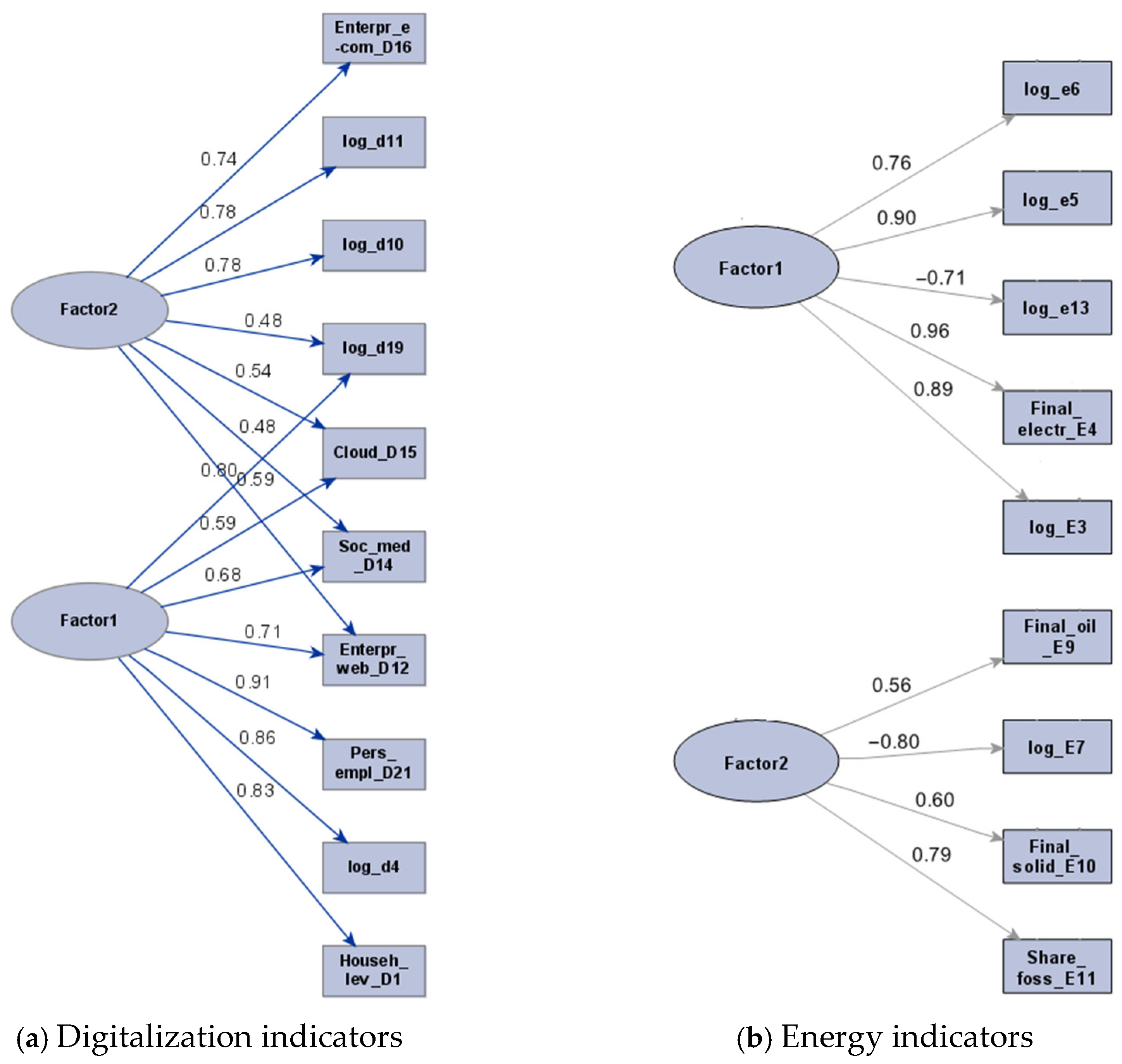

The graphical results of PCA for digitalization (a) and energy (b) indicators for 2023 are presented in

Figure 2.

4.1.1. Digitalization Indicators

A Varimax-rotated PCA was applied to identify the structure of digitalization indicators. Given the scope of this paper, a detailed discussion is provided only for the PCA results of the year 2023. The analysis revealed two distinct factors that together represent the main dimensions of digitalization:

The quality criteria of the final PCA model indicate its adequacy and reliability. These criteria are presented in the tables below, including the overall and individual MSA values (

Table 3), the number of extracted factors (

Table 4) and the final communality estimates (

Table 5), which show an acceptable level of variance explained. In determining the number of factors to retain, we followed the commonly applied eigenvalue-greater-than-one rule (Kaiser criterion), complemented by a theoretical assessment of the interpretability of the extracted components. This approach ensured that the retained PCA factors were both statistically sound and meaningful for subsequent Path Analysis.

PCA confirmed two factors of digitalization indicators. The developed composite indicators (factors) of digitalization are presented in

Figure 2a. In general, the goal of the PCA used in our study was to reduce the number of initial indicators that are required for Path Analysis when having a limited number of observations, as well as to calculate the PCA-based weighted composite ones and mitigate the subjective weighting techniques. It should be highlighted that some of the digitalization indicators, such as Cloud computing, Social media or Enterprises with a website are overlapped between both factors; thus, both factors have relatively high loadings on these indicators. However, the first factor has the highest loadings on indicators of (1) connectivity: Internet access level by households (0.83), (2) the human capital required for successful digital business: Employed ICT specialists (0.86), Persons employed in science and technology (0.91) and (3) the extent to which businesses use digital tools: Enterprises with a website (0.71); Social media (0.68); Cloud/Cloud computing utilization (0.59). According to the framework of EC Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) that was used in the studies of [

6,

24], our first factor contains the data that are related to the three different dimensions of DESI: (1) Connectivity (Internet access level by households), (2) Human capital (Employed ICT specialists, Persons employed in science and technology) and (3) Digital technologies for business (Enterprises with a website; Social media; Cloud/Cloud computing utilization). Following this framework, we combine the name for our first factor from all the three dimensions and call it “Connectivity, human capital and digital technologies for business” (pca1_D).

The second factor is more general, related to the education (Total number of people receiving education (0.78)) and technological development level of a country (Business enterprise R&D expenditure in high-tech sectors (0.78); Enterprises with e-commerce trading activities (0.74) and Total number of patent applications (0.48)). We follow [

47] who named education-related indicators Education level. For the second group of related indicators, we align with the framework of [

62], who referred to patent application-related indicators as technological effect, and [

15], who classified R&D expenditure-related indicators as technological progress; collectively, we refer to this assemblage of indicators as technological development level. Furthermore, Enterprises with e-commerce trading activities are also included into the technological development level group, as this measure pertains to the exchange of goods or services through digital technologies. In conclusion, we call the second factor of PCA “Education and technological development level” (pca2_D).

4.1.2. Energy Indicators

Similarly to the digitalization dimension, two factors were extracted for the energy dimension. For brevity, only the PCA results based on the 2023 data are presented and discussed in detail with retained factors.

The final PCA model for the energy indicators was found to be adequate and reliable, as shown in the tables below presenting the overall and individual MSA values (

Table 6), the number of extracted factors (

Table 7) and final communality estimates (

Table 8). According to the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1), two components were retained for further analysis. The variable Final_solid_fosil_E10 was retained in the model even though its individual MSA value was at the threshold, as the overall quality and adequacy of the PCA model remained higher when this variable was included.

PCA confirmed two groups (factors) of energy indicators that clearly separated (

Figure 2b). The first group represents energy intensity (pca1_E), and the second group is dedicated to energy structure (pca2_E). The negative values of the indicators mean that the factor is inversely proportional to the variable. The energy intensity group contains an indicator of energy productivity (with the loading of −0.71)—the ratio of GDP to total energy consumption, as well as electricity production and electricity consumption intensity indicators. energy productivity is inverse to all other indicators of Energy intensity factor, as the more energy is consumed, the lower the value this indicator has. In that way, the energy intensity factor is inverse to energy efficiency. This factor has the highest loadings on Final electricity consumption/GDP (0.96), Residential electricity consumption/GDP (0.90), and Gross electricity production/GDP (0.90).

The factor of energy structure includes the Share of renewable energy as well as fossil fuel-related indicators. In the same way—Share of renewable energy here is inverse to all other indicators of the energy structure factor, as it measures the proportion of energy from renewable sources in total energy, while other indicators of this group measure proportions of fossil fuel-related energy. Thus, the factor of energy structure is dedicated to measuring the fossil fuel-based energy structure, which is opposite to renewable energy. This factor has the highest loadings on Share of renewable energy consumption (−0.80) and Share of fossil fuels in gross available energy (0.79).

As the analysis revealed that there are only two factors of energy indicators, the individual indicator Primary energy consumption per capita (E2), which was not suitable for factor analysis, is used to represent the energy consumption in this study. Primary energy consumption per capita [

24,

26,

47] measures energy needs and covers the energy consumption by end users such as industry, transport, and households [

63]; thus, it is a suitable representative for energy consumption of a country.

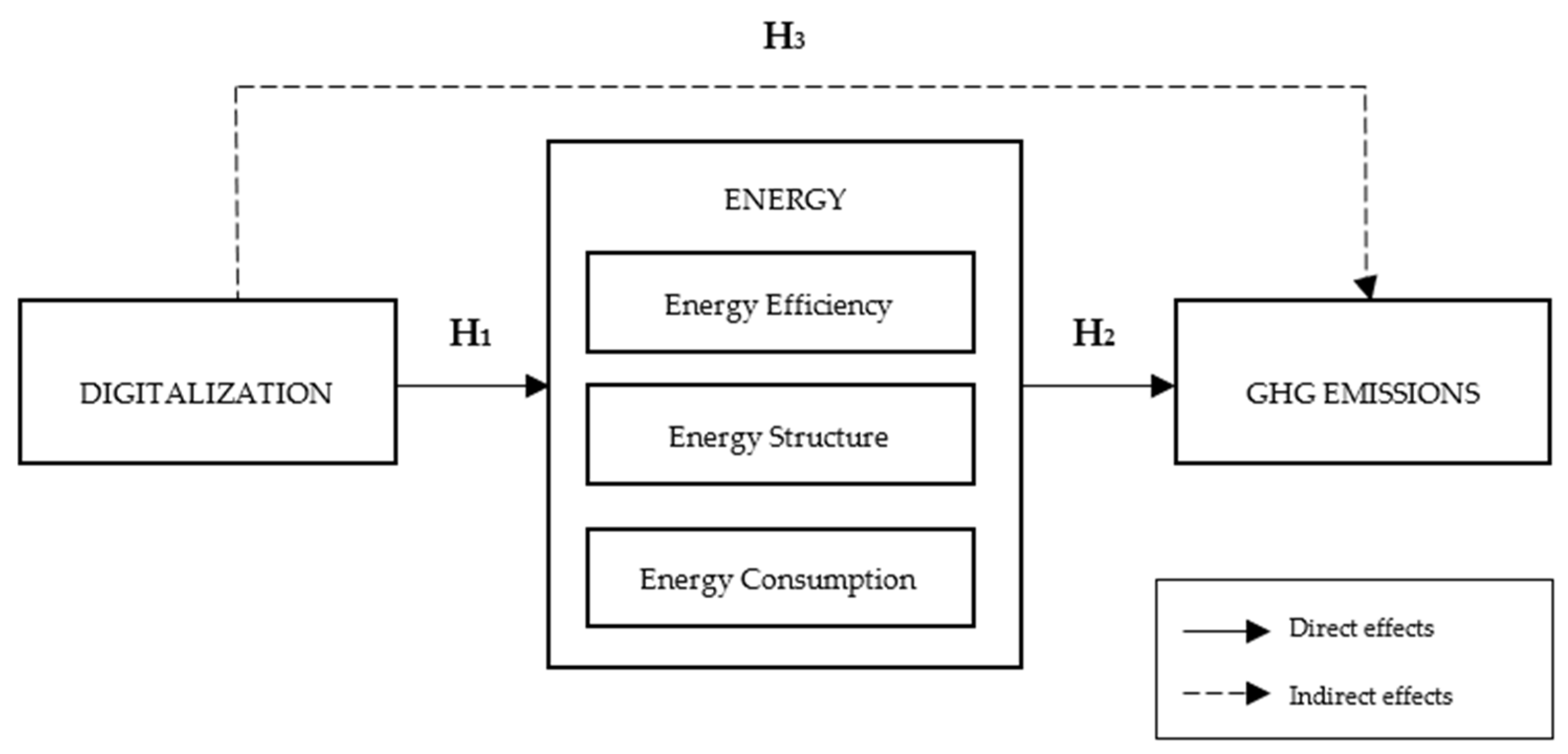

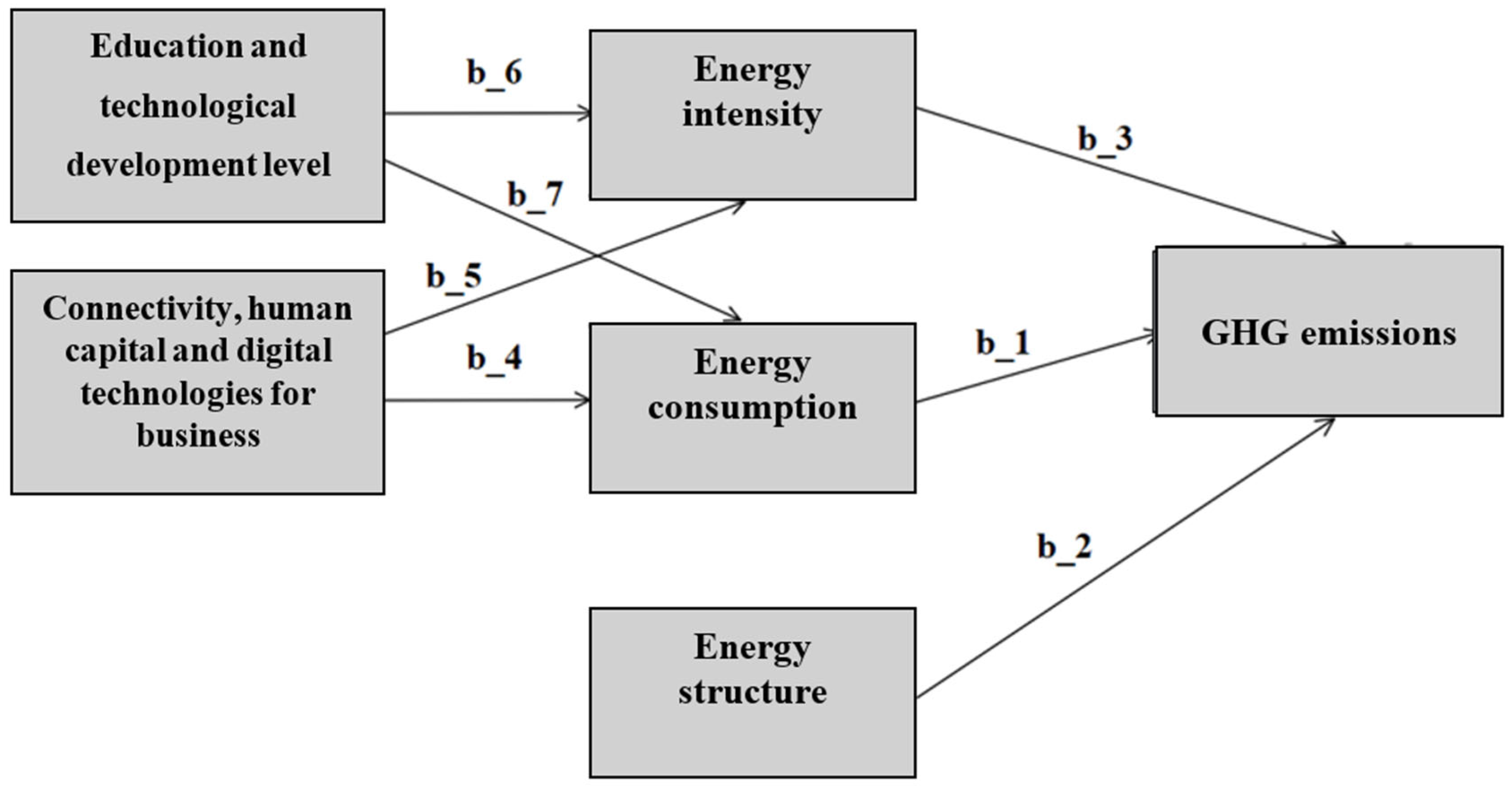

4.2. Path Analysis

The linear equations for the Path Analysis were developed in accordance with the theoretical hypotheses, forming the conceptual basis for the structural model. After the theoretical framework had been defined, the structure of the equations was specified to ensure consistency between the theoretical model and statistical identifiability. In Path Analysis, the structure of equations is determined by the number of estimated parameters to ensure that the model remains identified. The final model represents a case of an over-identified model, where the number of estimated parameters is smaller than the number of moments. The number of moments is calculated as k(k + 1)/2, where k is the number of observed variables. The difference between the number of moments and the number of estimated parameters represents the model’s degrees of freedom (df). In this study, the Path model was constructed so that df > 0, ensuring that the model is over-identified and that its fit can be statistically evaluated. In such a case, it is possible to assess not only the parameter estimates themselves but also the overall quality of the model by comparing the estimated covariance matrix with the empirical covariance matrix. Although including additional variables would be theoretically desirable, doing so would have reduced the model’s degrees of freedom to zero, resulting in a just-identified model where fit cannot be statistically assessed. Therefore, the current, more parsimonious model was retained to preserve over-identification, enable empirical evaluation of model fit, and ensure stable estimation given the small sample size.

After evaluating all quality and suitability criteria, only the equations demonstrating the most meaningful and theoretically justified relationships were included in the Path model. Given the structure of the available data and the small sample size, the number of regressors had to be deliberately kept limited to ensure that the Path model would remain identifiable and retain positive degrees of freedom. We used the adjusted coefficient of determination (

Appendix B) as a diagnostic tool to verify that each equation contributed sufficient explanatory power, since equations with very low R

2 values would undermine model fit. For these reasons, only relations with the highest adjusted R

2 values and clear theoretical relevance were selected for inclusion in the model.

In certain cases, variables with statistically non-significant

p-values were retained in the regression equations, as their inclusion was theoretically substantiated and consistent with the conceptual framework of the study. This approach is also justified by the small sample size, where

p-values may lack sufficient power to detect existing effects. Ref. [

64] highlights that in mediation models, the primary focus should be placed on the magnitudes of the direct and indirect effects rather than on

p-values, further supporting the suitability of this approach for the aims of our study.

Regression analysis (

Appendix B) has shown that GHG emissions (

Table A2) can be predicted using the data of energy intensity and energy structure composite indicators, as well as the individual indicator of energy consumption (Adj. R-Sq = 0.4517). However, GHG emissions regression with predictors of digitalization (

Table A3) had a very low value of Adj. R-Sq (0.1521); thus, the direct effects of Digitalization on GHG emissions were not included in the final model. Regression analysis also revealed that energy intensity (Adj. R-Sq = 0.5132) (

Table A4) and energy consumption (Adj. R-Sq = 0.2683) (

Table A5) can be predicted using the composite indicators of Connectivity, human capital and digital technologies for business as well as Education and technological development level, while these were not suitable predictors for the energy structure (Adj. R-Sq = 0.0510) (

Table A6).

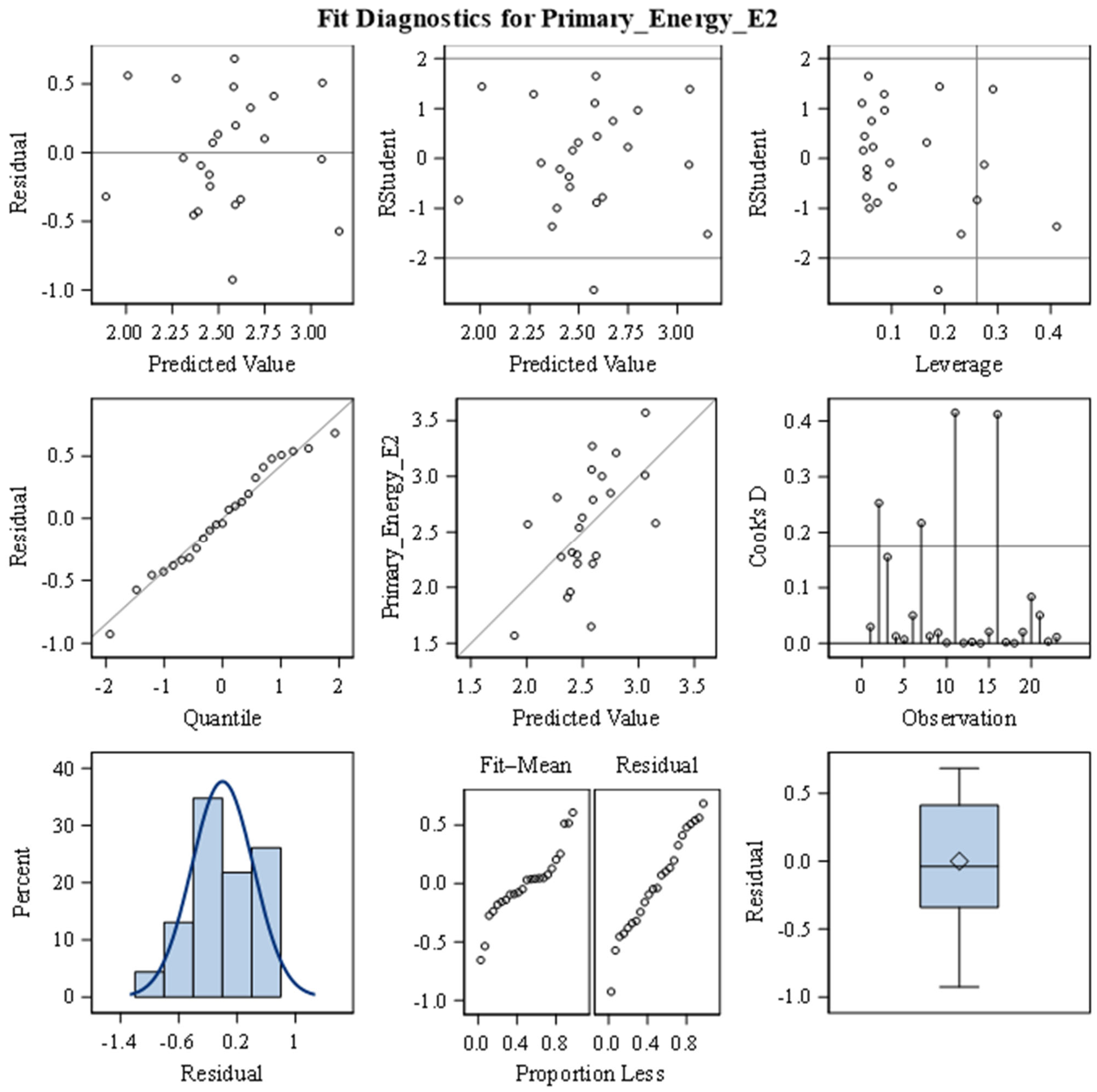

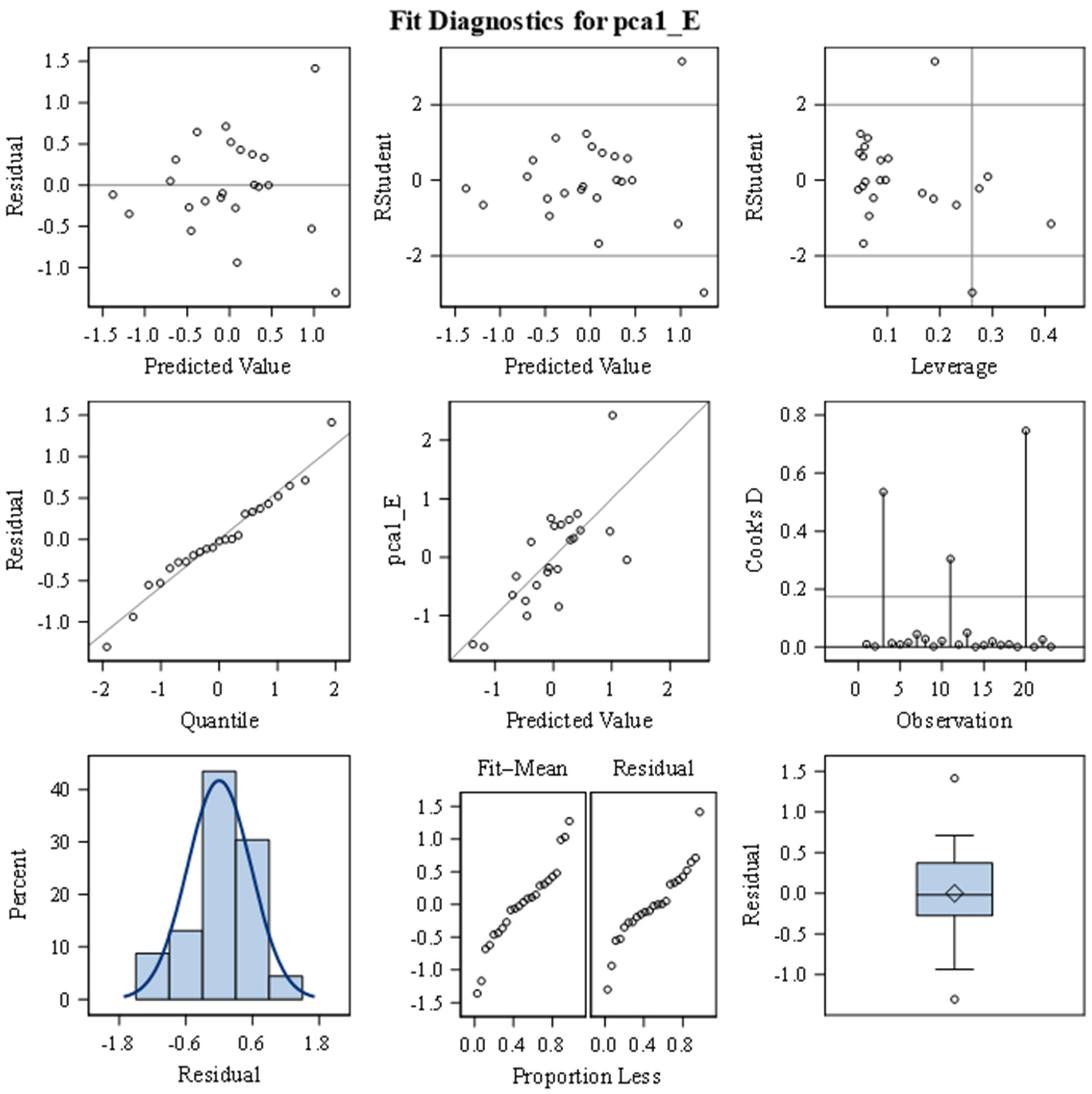

In parallel, by adjusting the regression equations of the Path Analysis model according to the theoretical hypotheses and the requirements of model identifiability, a corresponding regression analysis model equation was constructed and tested to verify whether it met all regression model assumptions. This procedure was carried out to ensure the reliability of the regression equations and to prevent poor model quality in the Path Analysis. For this purpose, potential outliers were examined, and cases of Sweden, Finland, and Luxembourg were identified as strong outliers and, therefore, were excluded from the analysis to ensure the robustness and reliability of the estimated Path coefficients. All these countries had extremely high technological development levels according to their indicators, while Sweden and Finland were also extremely good in terms of renewable energy. During the estimation of the Path Analysis models, these countries proved to be highly influential observations that exerted an unusually strong impact on the estimated coefficients. Influence diagnostics (e.g., leverage and residual patterns) showed that their presence substantially distorted the regression relationships. As is well-established, Path Analysis and OLS-based regression models become unreliable when dominated by such influential cases, because parameter estimates become unstable and the mediation structure is compromised.

Additionally, the multicollinearity of the independent variables in the equations was examined using the variance factor (VIF), which quantifies how much the variance of a regression coefficient is increased due to collinearity among predictors. All calculated VIF values were below 4, indicating an acceptable level of multicollinearity. In addition, the absence of autocorrelation in the regression residuals was tested using the Durbin–Watson (D) statistic. The obtained D value was approximately 2, and the corresponding

p-value was not statistically significant, indicating that neither positive nor negative autocorrelation was present in the residuals. In addition, the heteroscedasticity of the regression model residuals was examined using the test of first- and second-moment specification, which indicated adequate model properties and confirmed that the assumption of homoscedasticity was satisfied. Moreover, the normality of residuals (Shapiro–Wilk test) and the equality of their means to zero (

t-test) were tested, confirming that the residuals met the assumptions of normal distribution and zero-mean. The corresponding hypotheses regarding the normality and zero-mean value of residuals were verified and not rejected, indicating that the model satisfies the classical linear regression assumptions. The results of the regression analysis and the assessment of its assumptions for 2023 are provided in

Appendix C, supporting the adequacy of the model specification.

This led to the following structural linear equations with standardized coefficients of the final Path Analysis model (

Table 9).

The codes of composite and single indicators used in the Path Analysis model are given in

Table 10.

The coefficients b

1 to b

7 in

Table 9 represent the direct standardized effects among variables in the Path Analysis model, where each b quantifies the direct influence of one variable on another while controlling for all other relationships in the model. The standardized effects generally range in magnitude from −1 to +1, representing the full possible span of relationships from strongly negative to strongly positive.

According to the conventions proposed by [

65], standardized effect sizes of around 0.10 are considered small, those of around 0.30 are moderate, and those of 0.50 or greater are large in practical significance. Negative (inverse) coefficients indicate that as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease, suggesting an opposing or reversing relationship between them. The closer a negative value is to −1, the stronger the inverse association. In contrast, positive coefficients imply that increases in one variable are associated with increases in another, with values near +1 representing a powerful direct connection. Occasionally, standardized coefficients greater than 1 can appear when variables share very high correlations or when measurement error inflates relationships. Such coefficients do not indicate a computational mistake, but they should be interpreted cautiously as indicators of exceptionally strong relationships.

In this investigation, we focus exclusively on standardized effects, as they allow for the direct comparison of the relative strength and direction of relationships across variables measured on different scales. Standardization removes the influence of measurement units, making it possible to evaluate which Path exert the strongest impact within the overall model. Because all coefficients are expressed on the same standardized scale, the direct, indirect, and total effects can be meaningfully compared to assessing the relative contribution of each pathway to the dependent variable. This comparability enables a clearer understanding of how much of the total influence is transmitted through mediating variables versus direct causal links.

The formulas used to calculate the indirect standardized effects are presented in

Table 11.

Furthermore, the goodness of fit of the Path Analysis model was evaluated for each year of the study (from 2014 to 2023, excluding 2021 and 2022 due to insufficient data). The models were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method, with an identical structure across years, including three endogenous and six exogenous variables and a total of nineteen parameters. The key fit indices assessed were the Chi-square (χ2) statistic and its probability (p-value), the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) and its adjusted version (AGFI), the Root Mean Square Residual (RMR/SRMR), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence interval, and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), and Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI).

Across all years, Chi-square test p-values were greater than 0.05, indicating that the models did not significantly differ from the observed data and could therefore be considered an acceptable fit. Other indices generally supported this conclusion: most GFI values exceeded 0.90, SRMR values remained below 0.08, CFI was not less than 0.9, and RMSEA confidence interval [0; 0.05], suggesting a satisfactory overall model fit.

However, the number of observations was relatively small, which limits the reliability and generalizability of the fit indices. With such sample sizes, fit statistics can become unstable, and goodness-of-fit measures may either overestimate or underestimate the true model quality [

58]. For this reason, we focused on the magnitude of effects, rather than on

p-values or fit indices. All interpretations are therefore based on the estimated direct and indirect effects. Nevertheless, the overall fit indices across the analyzed years indicate that the specified Path model provides a reasonably good fit to the available data (a detailed summary of fit indices for each year is presented in

Appendix D).

For each year, both the direct and indirect standardized effects were calculated to evaluate the structure and strength of relationships among the model variables over time. To assess the stability of the estimated coefficients, the bootstrap method was applied, generating 1000 resamples of similar size. For each resample, both the Path model coefficients and the corresponding effect estimates were recalculated, and their confidence intervals were estimated. The summarized results of all Path Analysis effects are presented in

Appendix E, while the Path Analysis model diagram with the corresponding coefficients is shown in

Figure 3.

In the following sections, we provide a more detailed discussion of the direct and indirect effects observed throughout all investigated years.

4.2.1. Direct Effects

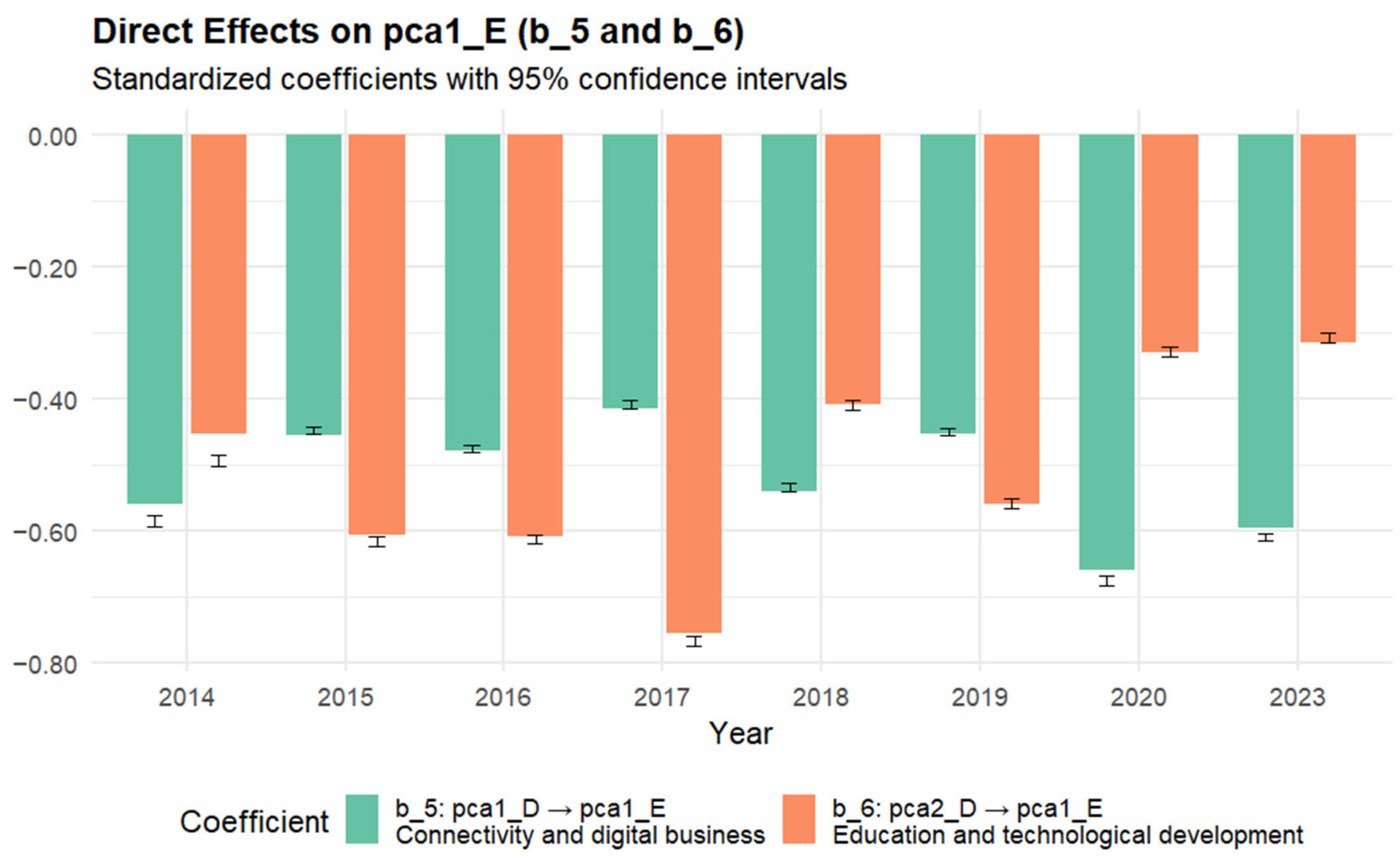

Both digitalization components, Connectivity, human capital and digital technologies for business (parameter b

5), as well as Education and technological development level (parameter b

6), had direct effects on energy intensity composite indicator (

Appendix E). As parameter values are negative, this means that the higher the digitalization level is, the lower the energy intensity we have. Thus, digitalization has positive direct effects on energy efficiency. Digitalization improves energy efficiency via automation, continuous monitoring, and systematic optimization. This is in line with [

3], who investigated the impact of digitalization on haze pollution and emphasized that digitalization contributes to a reduction in energy intensity.

Figure 4 illustrates the estimated sample coefficients, shown as the bar height, along with the bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the mean coefficient estimates, with the bootstrapped mean value located at the center of the interval.

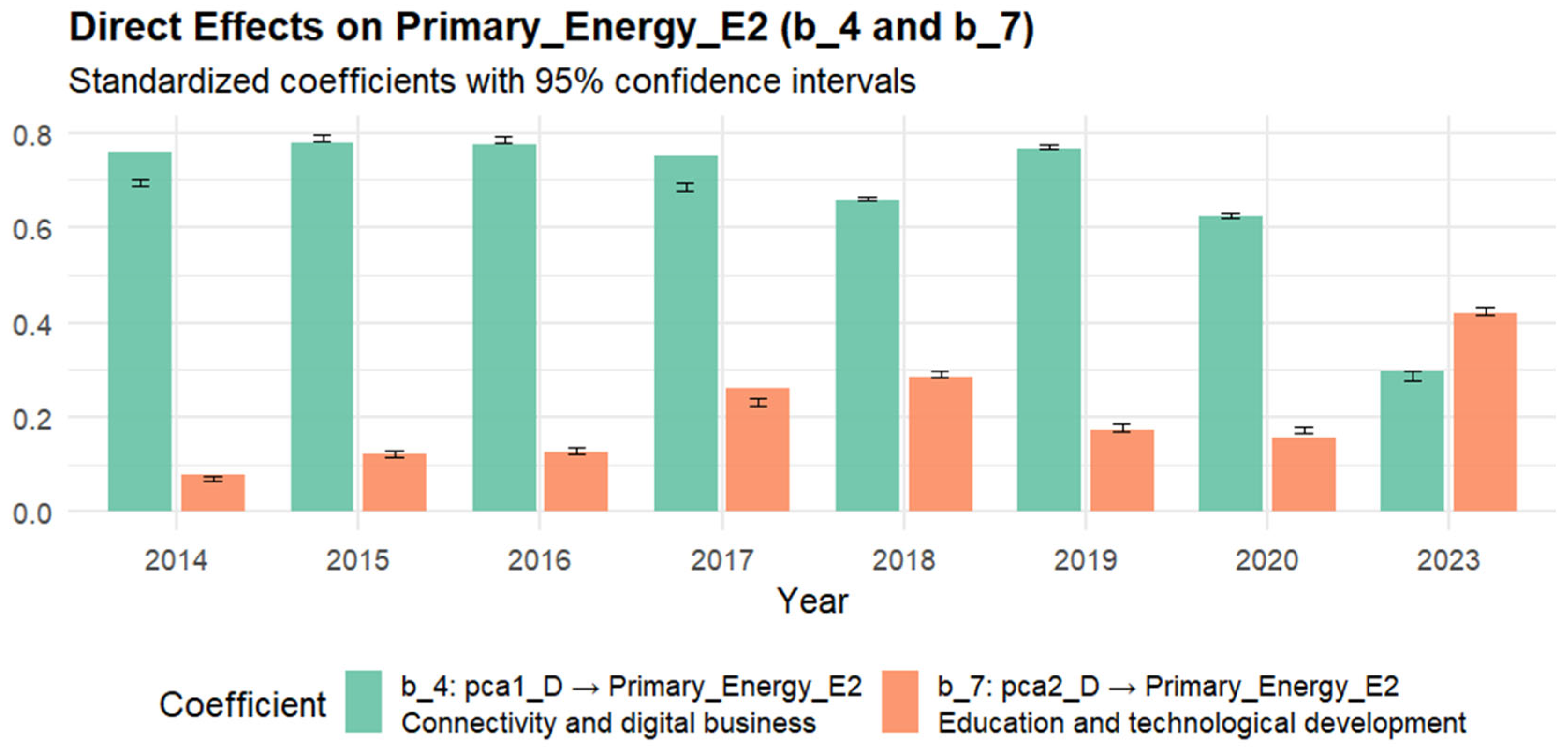

The positive direct effects of Connectivity, human capital and digital technologies for business (parameter b

4) were determined on energy consumption in 2014–2023, while the Education and technological development level (parameter b

7) was not significant for the years 2014–2020, but it became significant and even higher than Connectivity, human capital and digital technologies for business in 2023 (

Appendix E). This shift could reflect a transition from digital expansion in data centers, devices, and networks that require energy to smart transformation when education and sustainable technology matter more. Nevertheless, both digitalization factors had positive direct effects on energy consumption in 2023 (the higher the level of digitalization is, the more energy is consumed).

This can be explained by the two main effects: First, it is in line with [

35], who emphasized that the implementation of energy digitalization requires a lot of computational power and is associated with high energy consumption; and second, it can be explained by consumer behavior. Since improvements in energy efficiency led to a reduction in the marginal costs of energy services, it can be anticipated that the utilization of such services will increase, consequently offsetting some of the expected reduction in energy consumption. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as the direct rebound effect [

66]. However, even if there is no direct rebound effect, there exist numerous additional factors that may contribute to the economy-wide reduction in energy consumption being less pronounced. For instance, the financial savings accrued from reduced energy consumption may be allocated towards the acquisition of alternative goods and services that similarly necessitate energy for their provision. Depending on the context in which energy efficiency improvement is realized, these so-called indirect rebound effects may manifest in various forms, including increases in the output of certain sectors, transitions towards more energy-intensive goods and services, and increases in energy consumption attributable to decreased energy prices and accelerated economic growth [

66]. The comprehensive rebound effect resulting from an improvement in energy efficiency encapsulates the aggregation of these direct and indirect effects.

Figure 5 displays the estimated coefficients together with the bootstrapped 95% confidence interval for parameters b

4 and b

7.

As the regression analysis has shown that there is no linear relation between digitalization and energy structure (

Appendix B), the direct effects of digitalization on energy structure were not tested in Path Analysis. On the other hand, the literature review suggested that digital technologies can be a powerful tool for fostering renewable energy as digital forecasting techniques and smart grid coordination mitigate intermittency and stabilize the contributions of renewable energy sources [

2], blockchain-enabled systems foster transparent peer-to-peer energy trading [

31] and digital platforms engender competitive markets for renewable energy [

32]. However, the insignificant linear relationship between digitalization and energy structure may reflect nonlinear or lagged effects as renewable integration requires years of investment and the integration of renewable technologies to the existing power grids requires substantial upgrades, such as smart meters, advanced sensors, real-time data platforms, and digital control systems. These upgrades involve high costs, complex coordination among utilities, and technical challenges; thus, grid integration progresses slowly, limiting its immediate impact of digitalization on the overall energy structure. Also, it could be influenced by national energy policies, pricing systems and regulatory frameworks and require more governmental initiatives for pushing renewable energy forward. All these obstacles can weaken any direct statistical relationship between digitalization and changes in the national energy structure.

To summarize, the hypothesis “H1: Digitalization has direct effects (positive or negative) on energy consumption, energy efficiency and energy structure” was partially confirmed as digitalization had direct effects on energy intensity and energy consumption, but there was no significant impact of digitalization on energy structure.

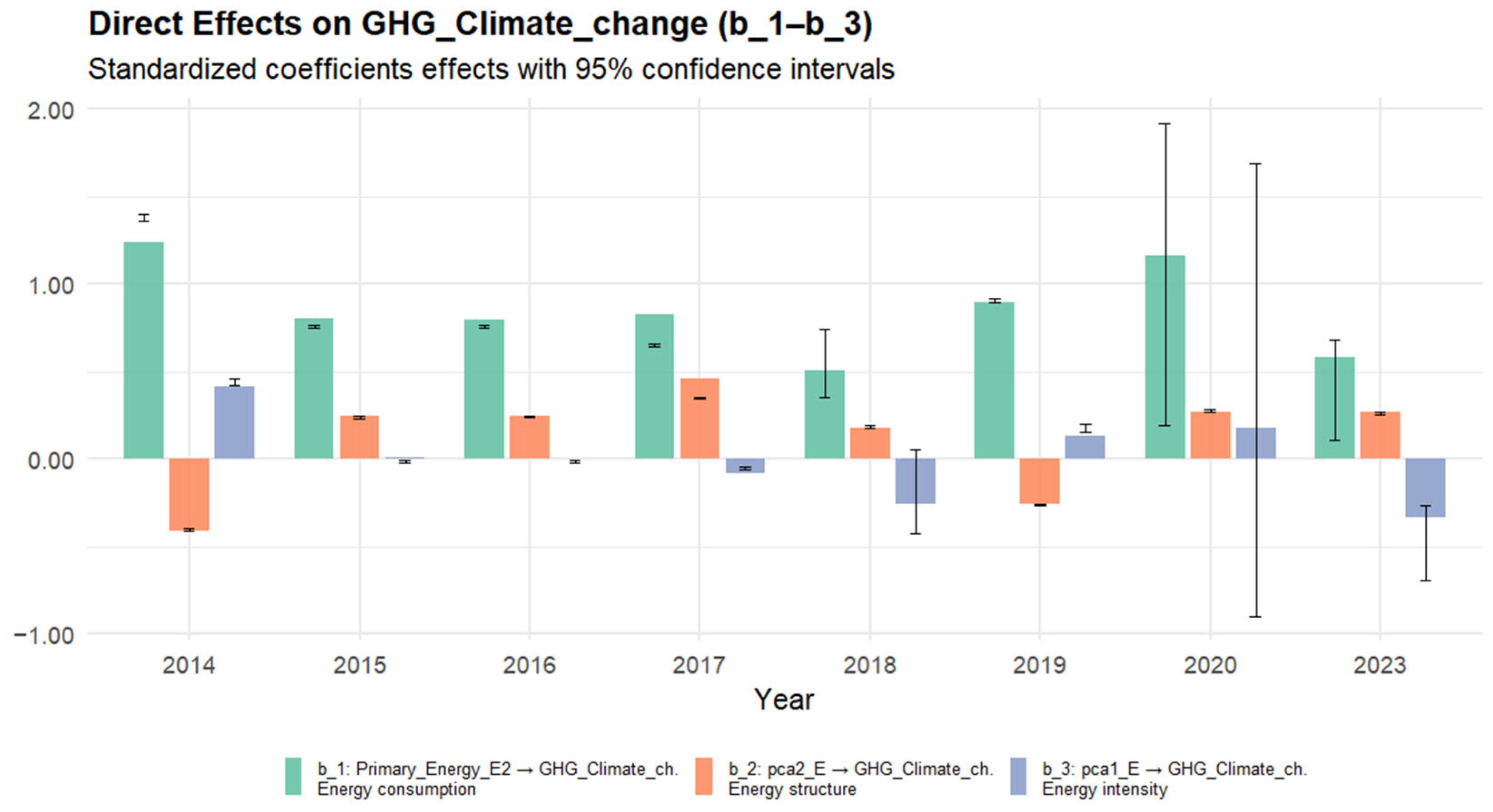

The Path Analysis has revealed that direct effects of energy intensity (parameter b

3) on GHG emissions were not significant (

Appendix E). Thus, our research did not confirm the conclusions of [

2], who emphasized that significant improvements in the efficiency of energy production, distribution, and consumption not only optimizes the use of resources but also enables the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite this, the positive direct effects of energy consumption (parameter b

1) on GHG emissions were detected (

Appendix E). This means that the higher the energy consumption is, the more GHGs are emitted. Thus, the effects of energy efficiency on GHG emissions are not as important as the rebound effects of energy consumption, and this is in line with [

9], who highlights the complex and potentially varying impacts of digital technologies on energy efficiency in manufacturing, as while some technologies can lead to reduced energy intensity, others may increase energy demand.

Energy structure (parameter b

2) has significant effects on GHG emissions (

Appendix E). During most of the period of analysis, the effects are positive, meaning that the more fossil fuel-based energy structure there is, the more GHG are emitted. Thus, a renewable energy-based energy structure helps to reduce the amount of GHG emissions and adds its value to climate change mitigation. It confirms the positive repercussions of renewable energy consumption on environmental outcomes [

36]; thus, structural transformation serves to bolster sustainability. It is highlighted that in some years (2014, 2018), parameter b

2 is negative, and that generally means that even renewable energy systems entail lifecycle emissions, particularly during their production and maintenance phases.

In conclusion, the hypothesis “H2: energy consumption, energy efficiency and energy structure have direct effects (positive or negative) on GHG emissions” was partially confirmed. However, it is notable that the effects of energy consumption on GHG emissions are much higher than those of Energy structure, as b

1 > b

2 in all the year models (

Figure 6); thus, the rebound effect of energy consumption undermines the benefits associated with renewable energy.

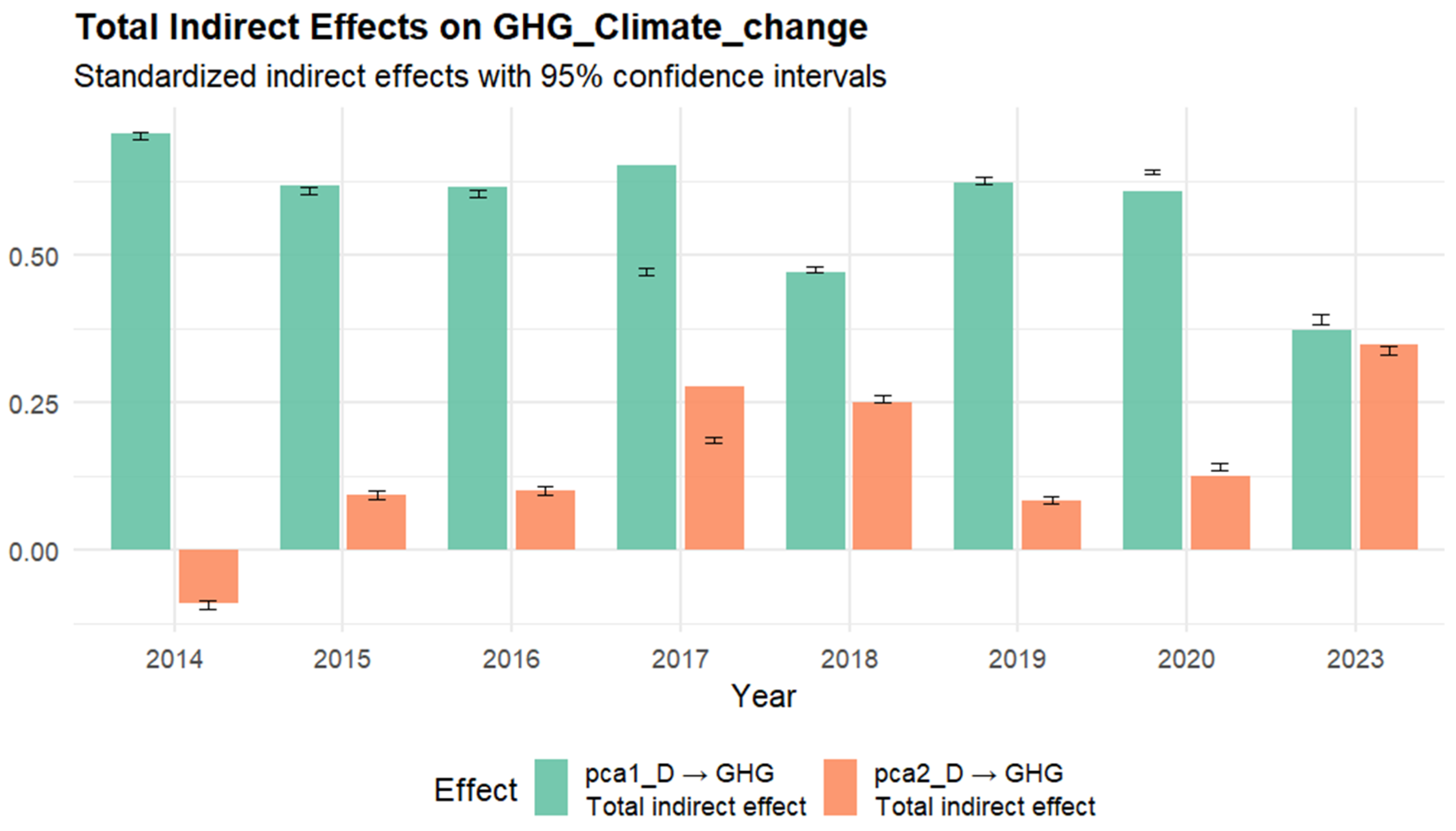

4.2.2. Indirect Effects

The indirect impacts of digitalization on GHG emissions were also evaluated. Connectivity, human capital and digital technologies for business had significant positive indirect effects on GHG emissions, while the effects of Education and technological development level were not significant for the period of 2014–2020 and became significant in 2023 (

Appendix E). Thus, the hypothesis “H3: Digitalization has indirect effects on GHG emissions, as energy is a mediating factor” was confirmed.

The indirect effects of digitalization on GHG emissions are illustrated in

Figure 7. The positive effects mean that the higher the level of digitalization is, the more GHGs are emitted. These indirect effects can be explained by the mediating effect of energy consumption: The higher the digitalization level, the more energy is consumed, and this leads to higher GHG emissions. These findings are in line with other authors [

8,

10], who stated that while digital technologies can improve efficiency in some areas, they also require substantial energy and carbon-intensive materials, leading to increased overall emissions [

8]; also, due to improvements in digitalization, the costs are reduced, and this leads to increased energy demand and pollution of the environment [

10]. Our study has shown that the rebound effect plays a crucial role here, as energy efficiency and renewable energy penetration benefits gained because of digitalization are outweighed by increased energy consumption and this results in higher GHG emissions.