The reliable operation of distribution networks in open-pit mines is strongly affected by single-phase short circuits to ground. These faults are among the most common and hazardous in such environments. They typically occur when a conductor breaks at the insulator point and comes into direct contact with the ground. In such situations, zero-sequence voltage and current become key indicators for assessing protection system performance and power-receiver stability. In these cases, the zero-sequence voltage and current parameters play a decisive role in determining the performance of protection systems and the stability of power receivers. To ensure accurate assessment, it is necessary to develop equivalent replacement schemes that can reflect the physical conditions of the fault and capture the transient processes in the network.

In this study, a series of replacement schemes were designed to investigate zero-sequence voltages and currents for earth faults on the power receiver’s side. The models assume a symmetrical electromotive force. The distributed capacitances are replaced with concentrated parameters. Line and transformer impedances are considered negligible. These simplifications allow the analytical derivation of equations for fault currents and voltages. The resulting relations are validated using characteristic amplitude- and phase-variation curves. The obtained dependencies provide a theoretical foundation for evaluating the behavior of protective systems under different network insulation conditions and transient resistances.

4.1. Selection of the Replacement Schemes

A phase short to ground on the power-receiver side occurs when one of the overhead line conductors breaks. This situation is typical for distribution networks in open-pit mining operations. In most cases, the break occurs at the insulator—the mechanical fixing point. There, the conductor encounters a grounded, non-insulated surface [

15,

43,

44]. As a result, the two undamaged phases at the fault location are connected to the ground through the impedances of the power receiver and the transient resistance.

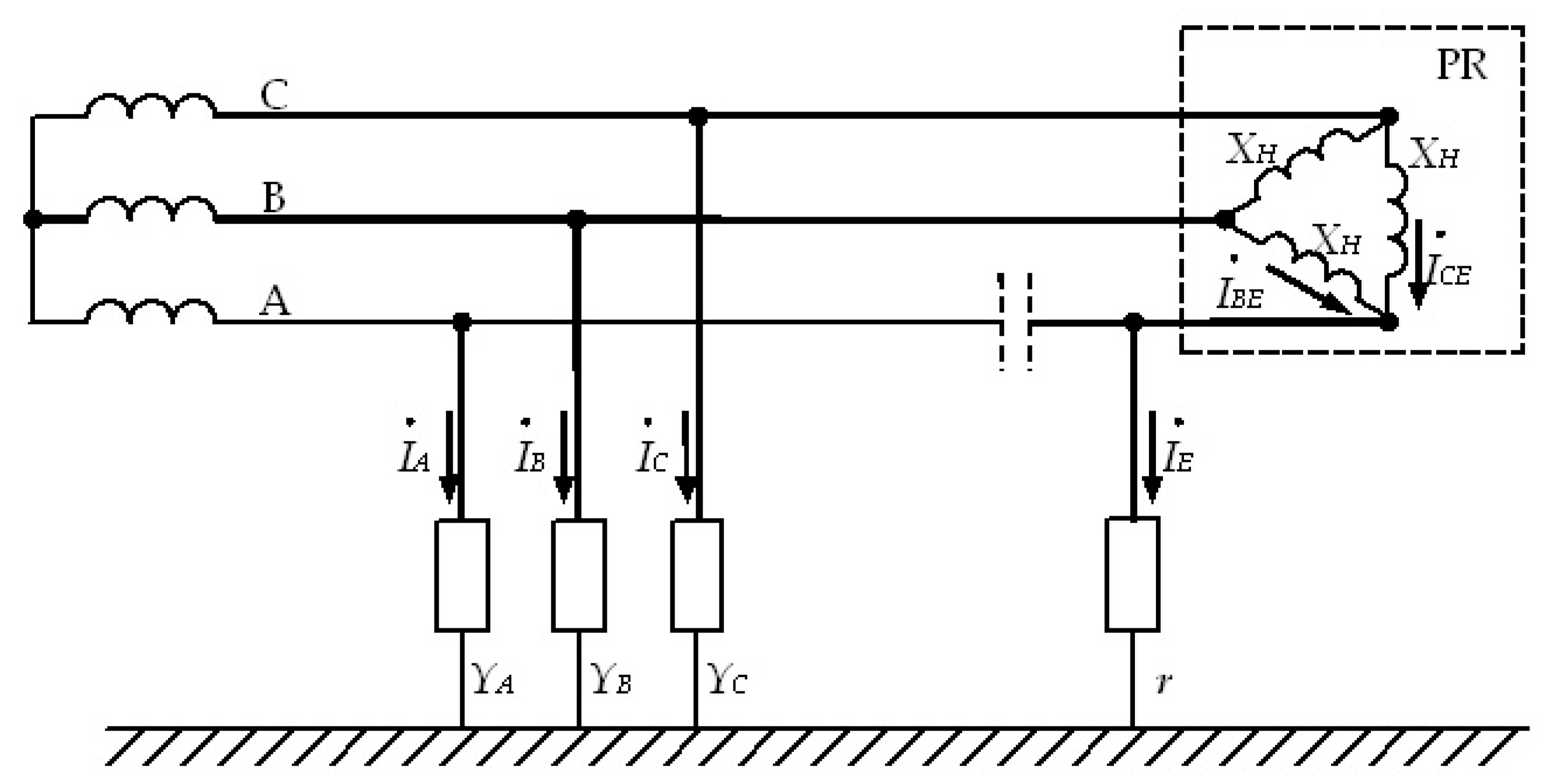

To investigate the behavior of zero-sequence voltages and currents during earth faults on the power receiver (PR) side, replacement schemes were developed (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In these schemes, the insulation conductivity of the damaged line section behind the fault point is assumed to be zero. This modeling approach allows for the systematic study of fault conditions while simplifying the complex interactions in the network.

Several limitations and assumptions were introduced to make the analysis tractable [

15,

43]. These assumptions include the following. The electromotive force of the power supply is symmetrical and free of higher harmonics. The distributed capacitance and insulation resistance of the phases relative to ground are replaced by concentrated values. The resistance and reactance of the line conductors are considered negligible. The resistance and inductance of the transformer windings are also taken as zero.

The diagrams (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) indicate:

Y1 and

Y′—the conductivity of the phase insulation of the protected connection and the remainder of the distribution network, respectively;

r1 and

r′—transient resistance at the point of damage in the protected connection and the remainder of the distribution network;

XH1 and

XH′—inductive reactance of the phase-to-phase winding of the power receivers.

Figure 1.

Distribution network replacement scheme for research zero-sequence voltages for earth faults on the side of the power receiver (PR): YA, YB, YC—conductivity of the insulation relative to the earth of the respective phases, r—transient resistance at the place of damage, XH = ωLH—inductive reactance of the phase-to-phase winding of the power receiver, IBE, ICE—ground-fault currents of phases B and C through load resistance and transient.

Figure 1.

Distribution network replacement scheme for research zero-sequence voltages for earth faults on the side of the power receiver (PR): YA, YB, YC—conductivity of the insulation relative to the earth of the respective phases, r—transient resistance at the place of damage, XH = ωLH—inductive reactance of the phase-to-phase winding of the power receiver, IBE, ICE—ground-fault currents of phases B and C through load resistance and transient.

As shown in

Figure 1, the equivalent circuit demonstrates the electrical behavior of the distribution network during an earth-fault event on the side of the power receiver. The insulation of each phase relative to ground is represented by the corresponding conductivities (

YA,

YB,

YC), which determine how leakage currents may appear under fault conditions. The point of insulation breakdown is modeled by a transient resistance (

r), reflecting the dynamic nature of the fault path as it forms and stabilizes. The inductive reactance of the phase-to-phase windings of the power receiver (

XH =

ωLH) influences the phase shift between voltage and current, thus affecting the overall fault current distribution. As the diagram illustrates, the ground-fault currents in phases

B and

C (

IBE and

ICE) flow through both the load resistance and the transient resistance, indicating a redistribution of current within the network. This provides a clearer understanding of how the system responds to insulation degradation and helps identify the critical parameters affecting zero-sequence voltage behavior during fault conditions.

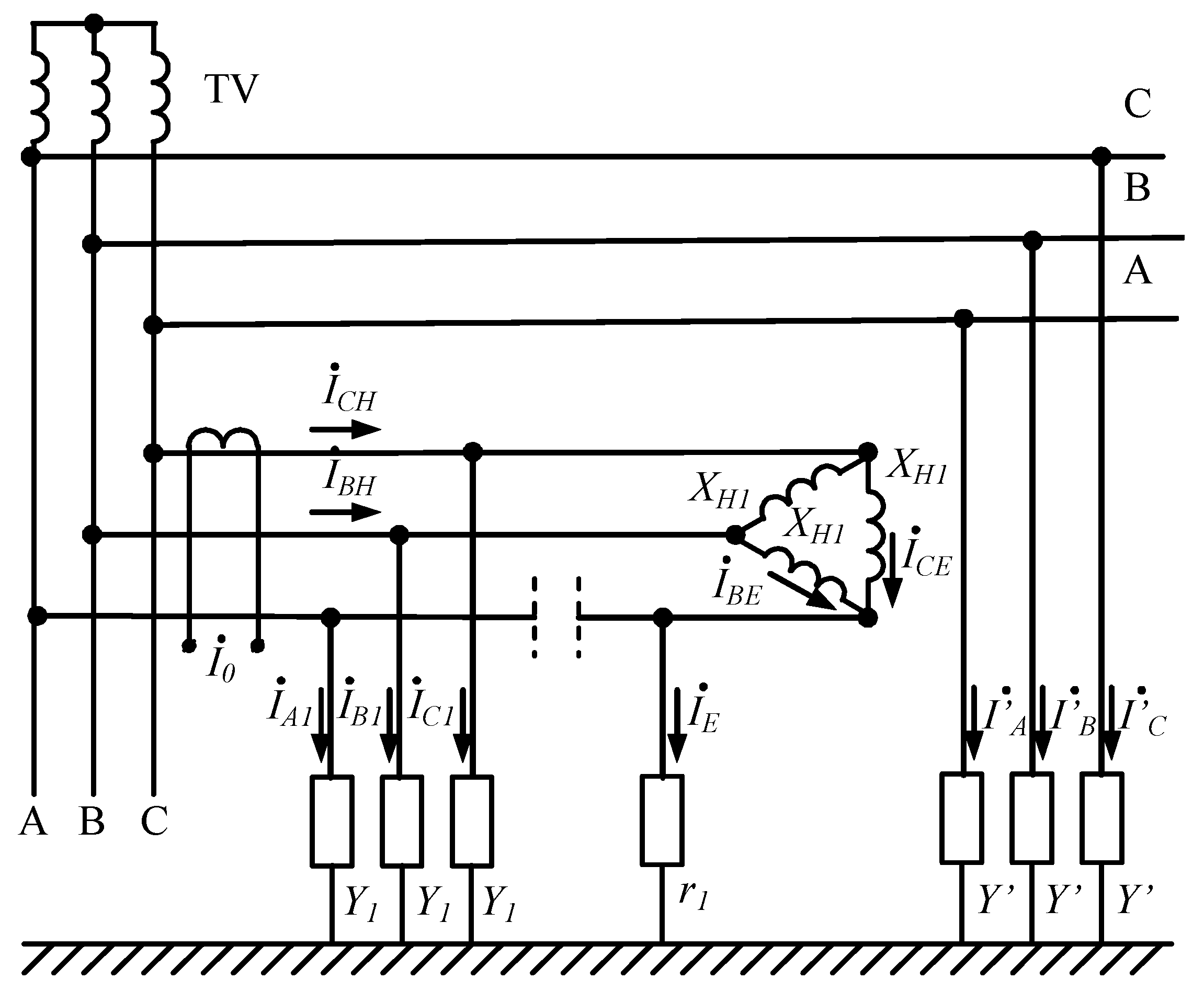

Figure 2.

Network replacement scheme for investigation of the zero-sequence current for earth faults on the power receiver’s side.

Figure 2.

Network replacement scheme for investigation of the zero-sequence current for earth faults on the power receiver’s side.

As shown in

Figure 2, the equivalent circuit model is employed to analyze the behavior of zero-sequence currents that arise during earth faults on the side of the power receiver. In this configuration, the inductive reactance of each phase winding is taken to correspond to the typical parameters of standard distribution transformers (400 kVA, 6/0.4 kV). The active resistance of the windings is disregarded due to its relatively small value compared with the reactance, allowing the analysis to focus primarily on the magnetic coupling effects within the circuit. This simplification enables clearer interpretation of how zero-sequence components are generated and propagate through the network under unbalanced fault conditions. The model therefore serves as a practical tool for identifying the relationship between fault impedance, system asymmetry, and current redistribution among the affected phases.

Figure 3.

Network replacement scheme for the investigation of the self-current protected line when closing in the external network.

Figure 3.

Network replacement scheme for the investigation of the self-current protected line when closing in the external network.

Figure 3 presents the equivalent scheme developed to investigate the self-current characteristics of the protected line when the circuit is closed through the external network. In this model, the conductivities (

Y1 and

Y′) represent the insulation of the protected connection and the remaining part of the network, respectively, while the transient resistances (

r1 and

r′) correspond to the fault points within each section. The inductive reactance of the phase-to-phase windings (

XH1 and

XH′) determines the electromagnetic interaction between the protected and external circuits. The resulting analysis reveals how current redistribution occurs between the local and external parts of the system, emphasizing the influence of inductive coupling and insulation integrity on the network’s overall stability. Such an approach provides valuable insight into the protective behavior of the line and the potential for energy feedback during external network interactions.

The three equivalent circuit models (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) provide a comprehensive representation of the distribution network’s behavior under earth-fault conditions.

Figure 1 highlights the mechanisms of zero-sequence voltage formation due to insulation degradation and fault current redistribution.

Figure 2 extends this analysis by examining the generation and flow of zero-sequence currents within the power receiver’s side, emphasizing the dominant role of inductive reactance in fault dynamics.

Figure 3 integrates these findings into a broader system perspective, demonstrating how self-currents develop in the protected line coupled with an external network. Together, these models show how insulation parameters, transient resistance, and electromagnetic coupling interact. This provides a deeper understanding of the factors that determine fault response and network stability.

4.2. Zero-Sequence Voltage

In accordance with the replacement scheme shown in

Figure 1 and considering the earth as the reference node of the circuit, the analysis of the system can be properly conducted. By applying the first Kirchhoff law to this configuration, one can derive the corresponding current relationships and equations [

15,

45]. This approach allows for a systematic investigation of the electrical behavior of the network under various operating conditions:

where

İBE and

İCE—the earth fault currents of the phase

B and

C through the load resistance and transient resistance.

By replacing the currents with their values and the necessary substitutions, we obtain:

where

Y—conductivity of the insulation relative to the earth;

y—the conductivity of phases B and C in the place of damage, taking into account the resistance of power receiver windings and transient resistance.

The expression for the voltage of the zero sequence at earth fault on the side of the power receiver is determined by the solution of the previous equation relative

and taking into account

After substitution instead of conductivity their values, expressed through insulation parameters

Y = 1/

R +

jωC,

y = 1/(

r +

jωLH) and performing the necessary transformations, we obtain:

where

R,

C—active resistance and capacitance of insulation of one phase of the network relative to the ground;

LH—the inductive resistance of the phase-to-phase winding of the transformer;

r—transient resistance at the place of damage.

The calculation formulas for the effective value of the zero-sequence voltage and the angle between its vector and the voltage vector of the damaged phase have the following form:

where

UP—phase voltage.

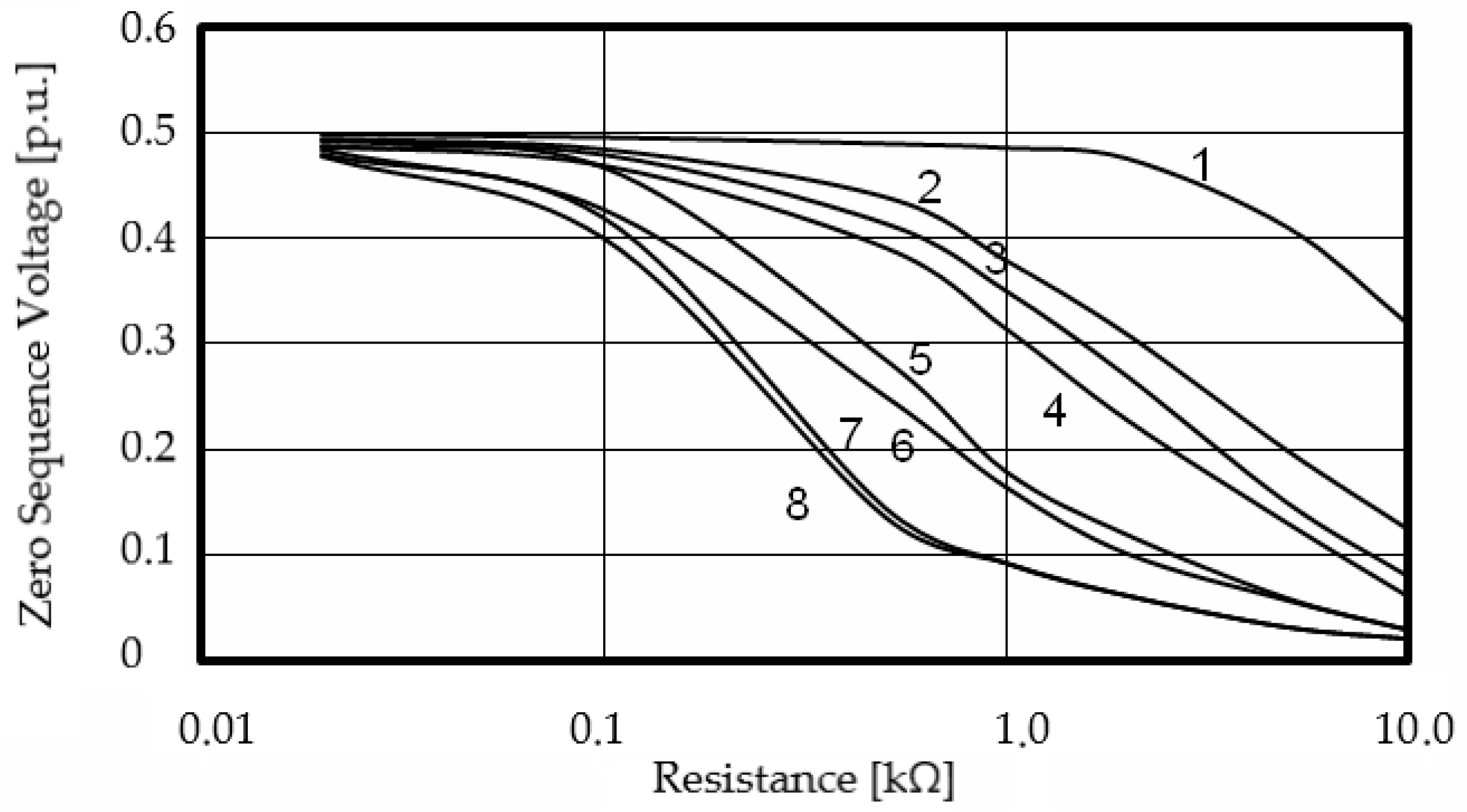

In

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the characteristic curves of the variation in the effective value of the voltage and the angle between the zero-sequence voltage and the damaged phase vectors for different values of the transient resistance at the point of damage and the network insulation parameters relative to the earth.

Figure 4 illustrates the variation in the zero-sequence voltage magnitude as a function of transient resistance

r in the case of a fault on the power receiver side. The data indicates a clear inverse dependence between the transient resistance

r and the zero-sequence voltage magnitude. At low resistance values (e.g.,

r = 0.02 kΩ), the voltage amplitude remains nearly constant across different insulation parameters, reflecting a strong capacitive coupling with the ground. As

r increases beyond 1 kΩ, the voltage decreases sharply, especially for larger capacitances, confirming the dominant effect of capacitive current leakage on fault voltage formation.

Figure 4.

Changing the voltage of the zero sequence in case of damage on the part of the power receiver at C (μF) and R (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—0.1 and 100.0; 2—0.1 and 10.0; 3—1.0 and 100.0; 4—1.0 and 10.0; 5—3.0 and 100.0; 6—3.0 and 10.0; 7—6.0 and 100.0; 8—6.0 and 10.0.

Figure 4.

Changing the voltage of the zero sequence in case of damage on the part of the power receiver at C (μF) and R (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—0.1 and 100.0; 2—0.1 and 10.0; 3—1.0 and 100.0; 4—1.0 and 10.0; 5—3.0 and 100.0; 6—3.0 and 10.0; 7—6.0 and 100.0; 8—6.0 and 10.0.

The parameter r denotes the transient (fault) resistance at the point of a single-phase ground fault and is expressed in kiloohms (kΩ). It reflects the quality of electrical contact between the damaged phase conductor and the grounding medium. At low resistance values (r = 0.02–0.1 kΩ), the fault path exhibits high conductivity, characteristic of solid or metallic ground faults. In this regime, the capacitive component of the fault current dominates, and the voltage-current phase approaches 360°, indicating an almost purely reactive response. At intermediate resistance levels (r = 0.2–0.5 kΩ), the fault becomes transient or semi-conductive. The resistive current component increases, resulting in a perceptible phase shift and a reduction in the zero-sequence voltage magnitude. At high resistance values (r = 1.0–2.0 kΩ), the fault path is weakly conductive, typical of arc-type or surface-leakage faults occurring through contaminated or moist insulation. In this range, the zero-sequence voltage decreases sharply, while the phase angle drops to 280–300°, indicating that the active component of the current becomes comparable to the capacitive one.

The characteristics obtained show that for

r < 0.1 kΩ the zero-sequence voltage remains nearly constant across all insulation parameter configurations, confirming the predominance of capacitive leakage currents. As r increases, the voltage declines steeply, particularly at higher capacitance values, reflecting stronger attenuation of the capacitive current. For

r > 1.0 kΩ, the zero-sequence voltage asymptotically approaches zero, indicating that the fault current becomes negligible and the system tends to restore symmetrical operating conditions. The nonlinear voltage decay highlights the significant influence of both insulation capacitance and transient resistance on zero-sequence voltage behavior underground-fault conditions. This tendency demonstrates the transition of the network behavior from capacitive to mixed resistive–capacitive as the fault resistance rises. The variation in the zero-sequence voltage phase angle in the event of a fault on the power receiver side for different values of network insulation parameters

C (μF) and

R (kΩ) is presented in

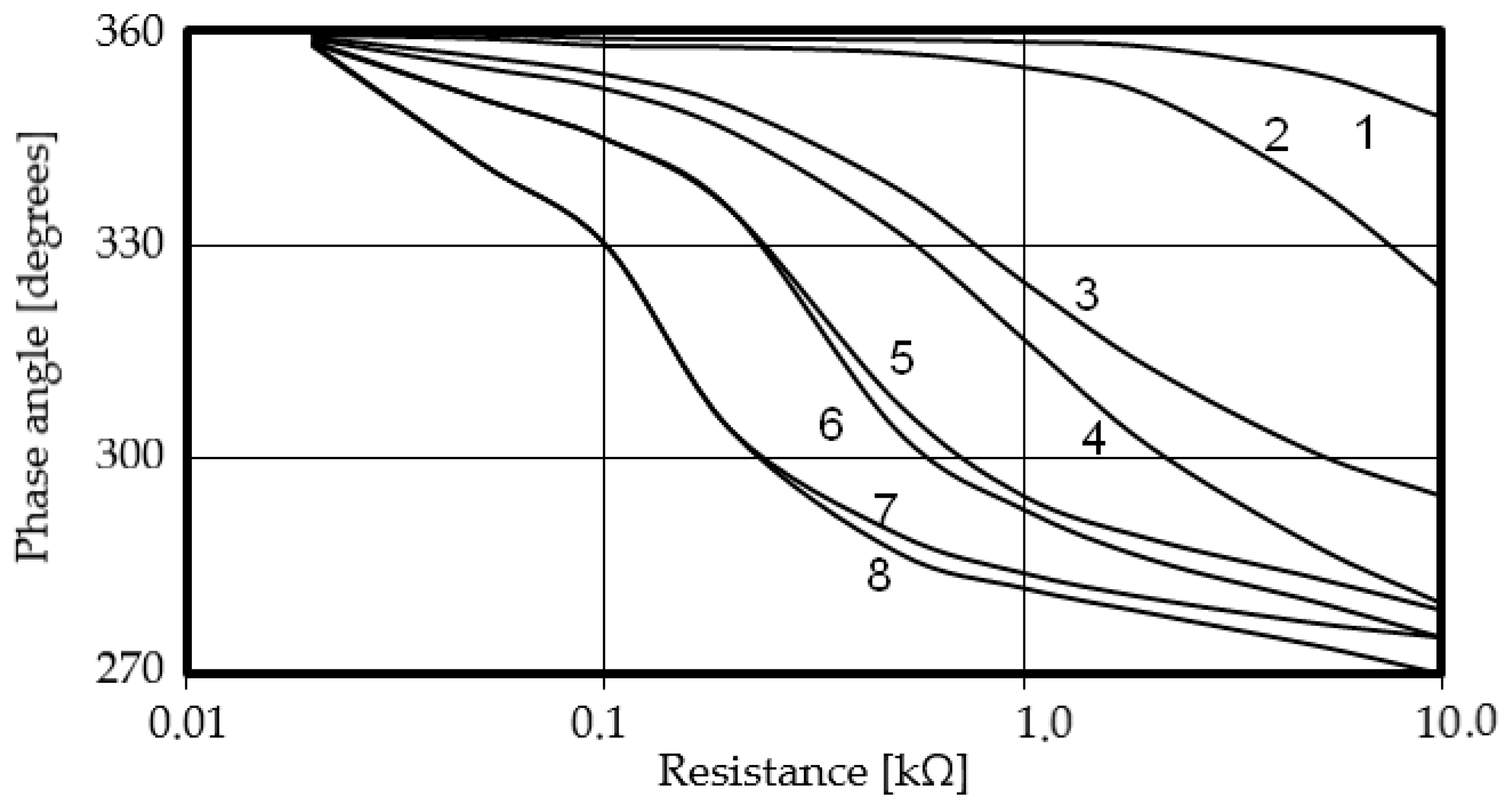

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Changing the phase of the zero-sequence voltage in case of damage on the part of the power receiver at C (μF) and R (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—0.1 and 10.0; 2—0.1 and 100.0; 3—1.0 and 10.0; 4—1.0 and 100.0; 5—3.0 and 10.0; 6—3.0 and 100.0; 7—6.0 and 10.0; 8—6.0 and 100.0.

Figure 5.

Changing the phase of the zero-sequence voltage in case of damage on the part of the power receiver at C (μF) and R (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—0.1 and 10.0; 2—0.1 and 100.0; 3—1.0 and 10.0; 4—1.0 and 100.0; 5—3.0 and 10.0; 6—3.0 and 100.0; 7—6.0 and 10.0; 8—6.0 and 100.0.

The dependencies demonstrate a nonlinear inverse relationship between the transient resistance and the zero-sequence voltage magnitude. At low resistance values (below 0.1 kΩ), the voltage remains practically constant (≈0.5 p.u.) for all parameter sets, which indicates that the fault current is dominated by the capacitive component and the system retains quasi-symmetrical behavior. For high resistance values (above 1.0 kΩ), the zero-sequence voltage approaches near-zero values, corresponding to a weak current flow through the fault path. In this region, the influence of insulation parameters becomes less significant, and the system gradually transitions toward a symmetrical steady-state regime. The higher insulation capacitance (curves 5–8) leads to a faster decay of voltage with resistance, while networks with lower capacitance (curves 1–2) retain a higher zero-sequence voltage at equivalent fault conditions.

The obtained numerical results clearly illustrate the sensitivity of the zero-sequence voltage phase characteristics to both the insulation parameters and the transient resistance, which is essential for accurate fault localization and for assessing the degree of insulation degradation in isolated neutral systems.

4.3. Zero-Sequence Currents

To assess the performance of earth fault protection system it is essential to investigate the amplitude and phase dependencies of the zero-sequence currents. For single-phase earth fault on the power receiver’s side two cases of damage should be considered:

- -

the earth fault on the side of the power receiver in the monitored line;

- -

the earth fault on the side of the power receiver outside the monitored line (in the external network).

The current of the zero sequence in the monitored line in the event of damage at the same connection is defined as the sum of all currents flowing in the line and according to the replacement scheme

Figure 2 is described by the expression:

where

İA1,

İB1,

İC1—currents in phases A, B, C, respectively, of the protected connection;

İBH and

İCH—the load currents, respectively, in phase B and C, in phase A the load current is zero due to a circuit break.

Given that the currents between phases B and C, determined by the magnitude of the linear voltage and the load resistance, are equal in value and counter-directed, the zero-sequence current is determined by:

where

İBE and

İCE—the earth fault currents of the phase B and C through the load resistance and transient resistance.

Performing the appropriate substitutions and transformations, we obtain the expression for the current of the zero sequence:

where

Y—the conductivity of the whole network phase insulation relative to the ground;

y—conductivity (taking into account the power receiver) of undamaged phases of the network relative to the ground in the place of damage;

Y1—insulation conductivity of the protected connection.

To express the current of the zero sequence through the parameters of the network installation and monitored connection, replace the conductivities with their values

Y = 1/

R +

jω

C,

Y1 = 1/

R1 +

jω

C1,

y = 1/(

r +

jω

LH) and after the corresponding transformations we obtain:

where

R1—insulation resistance of the protected connection;

P = 3

r + 2

R − 3ω

2CLHR and

Q = 3

ω (

LH +

CRr)—additional symbols entered to simplify the expression.

The effective value of the current of the zero-sequence expressed through the phase voltage

U and the installation parameters of the network of the protected connection of the power receiver and the value of the transient resistance at the point damage determined by the formula:

The angle between the zero-sequence current vector and the voltage vector of the damaged phase:

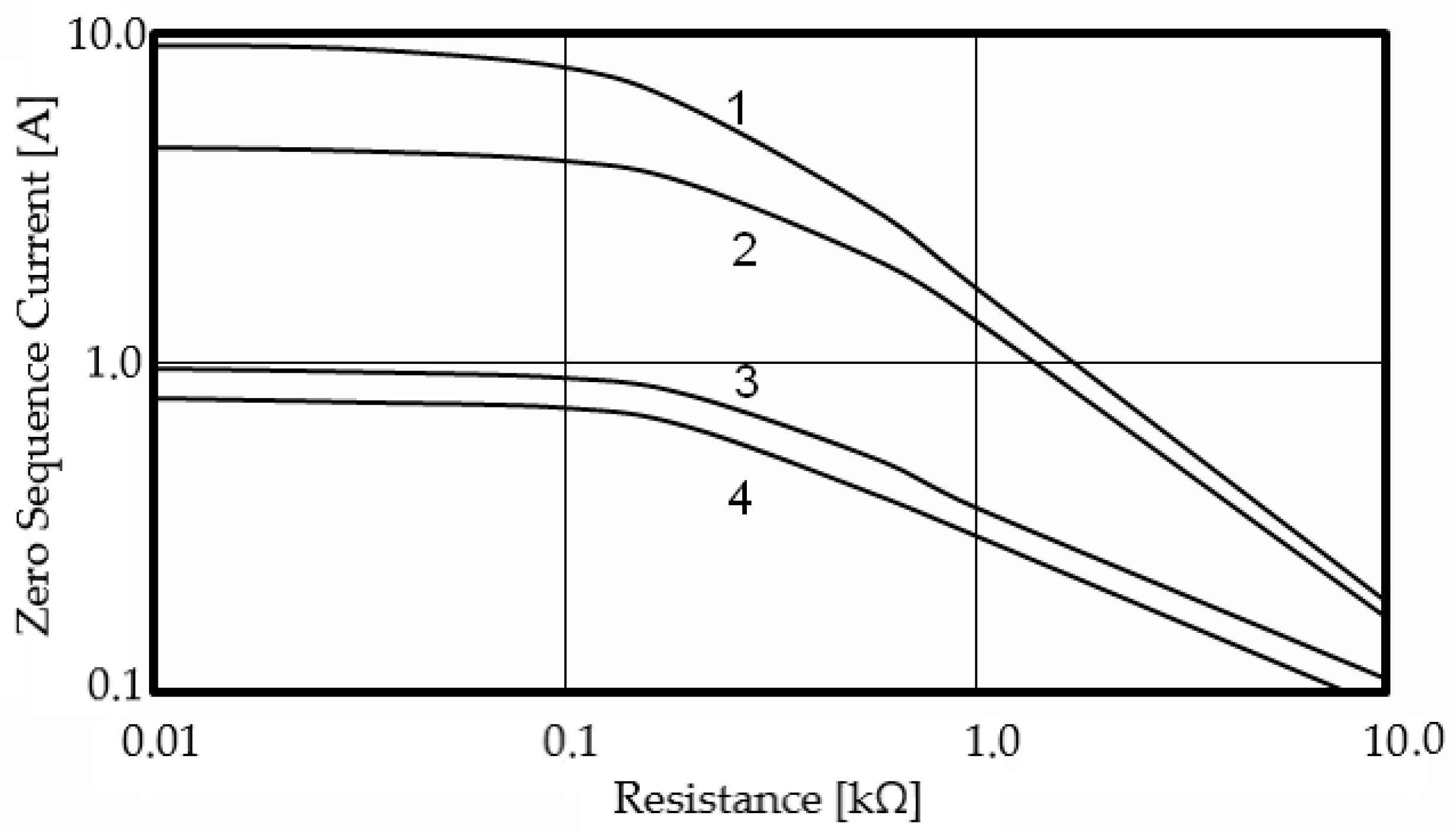

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the characteristic dependencies of the change in the effective value of current of zero sequence and the value of the angle between the vector of the investigate current and the vector of the voltage of the damaged phase, corresponding to the normal mode of a symmetrical three-phase system.

In case of closure outside the monitored line, the self-connection current based on the replacement scheme (

Figure 3) is defined:

Performing the appropriate substitutions and transformations, we obtain the expression for self-current of connection:

By replacing the conductivities with their values, we obtain:

Further research presents the calculated values of the zero-sequence current amplitude under conditions of a single-phase ground fault on the power receiver side. The parameter r represents the transient resistance (kΩ) at the fault location, which corresponds to different combinations of insulation capacitance C and resistance R. The data show a monotonic decrease in the zero-sequence current magnitude as transient resistance r increases. At very low resistance (r = 0.01–0.03 kΩ), the current reaches its maximum values, about 9.2 A for case 1 and 4.5 A for case 2, indicating a strong capacitive coupling and low impedance of the fault path.

As the resistance increases to r = 0.2–1.0 kΩ, the current declines significantly, and for r > 1.0 kΩ, it becomes nearly negligible, with values below 0.4 A. This behavior reflects the transition from a capacitive to a resistive–capacitive fault regime, in which the leakage current through the insulation decreases sharply due to reduced charge–discharge effects of the line-to-ground capacitance. At the highest resistance value (r < 10.0 kΩ), the zero-sequence current stabilizes at minimal levels (0.09–0.19 A), confirming that the system approaches a symmetrical state with almost no current flow through the ground path.

Figure 6 presents the variation in the zero-sequence current magnitude as a function of the transient resistance

r for several combinations of insulation capacitance

C and resistance

R. The results reveal a pronounced nonlinear inverse dependence between the zero-sequence current and the transient resistance.

Figure 6.

Changing the current of the zero-sequence depending on the transient resistance in case of damages on the side of the power receiver at C (μF) and R (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—6.0 and 10.0—100.0; 2—3.0 and 10.0—100.0; 3—1.0 and 10.0; 4—1.0 and 100.0.

Figure 6.

Changing the current of the zero-sequence depending on the transient resistance in case of damages on the side of the power receiver at C (μF) and R (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—6.0 and 10.0—100.0; 2—3.0 and 10.0—100.0; 3—1.0 and 10.0; 4—1.0 and 100.0.

At very low resistances (r ≤ 0.03 kΩ), the zero-sequence current reaches its maximum value, determined primarily by the capacitive leakage through the network insulation. In this region, the network behaves as a strongly capacitive system, and the current amplitude for the highest capacitances significantly exceeds that of configurations with smaller insulation capacitance.

As the transient resistance increases beyond 0.1 kΩ, the current decreases rapidly. This decline is caused by the diminishing capacitive coupling between the damaged phase and ground, with the rate of decay strongly influenced by the value of the insulation capacitance:

- -

networks with larger capacitance exhibit higher initial currents and a slower decrease,

- -

while networks with smaller capacitance show both lower initial currents and a steeper attenuation.

For high transient resistances (r ≥ 1.0 kΩ), the zero-sequence current approaches near-zero values, corresponding to weakly conductive or intermittent faults. In this region the contribution of the fault path to the overall current flow becomes negligible, and the system gradually approaches a symmetrical state. These findings confirm that zero-sequence current amplitude is highly sensitive to both insulation parameters and transient resistance, making it a reliable diagnostic indicator for ground-fault detection in isolated-neutral systems.

Figure 7 illustrates the dependence of the zero-sequence current phase angle on the transient resistance for the same insulation parameter sets. The results show a monotonic decrease in the phase angle as the transient resistance increases.

Figure 7.

The dependence of the phase of the zero-sequence current from the transient resistance in case of damages on the side of the power receiver at C (μF) and R (kΩ), respectively, equal to:1—6.0 and 10.0—100.0; 2—3.0 and 10.0—100.0; 3—1.0 and 10.0; 4—1.0 and 100.0.

Figure 7.

The dependence of the phase of the zero-sequence current from the transient resistance in case of damages on the side of the power receiver at C (μF) and R (kΩ), respectively, equal to:1—6.0 and 10.0—100.0; 2—3.0 and 10.0—100.0; 3—1.0 and 10.0; 4—1.0 and 100.0.

The results reveal a monotonic nonlinear decrease in the phase angle with increasing transient resistance. At low resistance values (r ≤ 0.05 kΩ), the phase angle remains close to 260–270°, indicating that the zero-sequence current is predominantly capacitive and lags the voltage of the damaged phase by approximately 90°.

As the transient resistance increases to the range of 0.1–1.0 kΩ, the phase angle gradually decreases to 210–240°, reflecting the transition from a capacitive to a mixed resistive–capacitive regime of current flow.

For high resistance values (r ≥ 2.0 kΩ), the phase angle stabilizes around 185–190°, which corresponds to a predominantly resistive behavior of the fault current and indicates that the reactive component becomes almost negligible. Overall, the figure demonstrates that the phase displacement between zero-sequence current and voltage depends strongly on both the insulation capacitance and the transient resistance.

Higher capacitance values (curves 3–4) lead to larger phase angles and a slower decline with increasing r, while lower capacitances (curves 1–2) result in smaller phase angles and a faster transition toward resistive behavior. These dependencies quantitatively describe the dynamic evolution of fault current characteristics in isolated-neutral networks and provide a theoretical basis for identifying the fault regime and estimating insulation condition.

The effective value and the angle between the zero-sequence current vector and the voltage vector of the damaged phase are defined by the expressions:

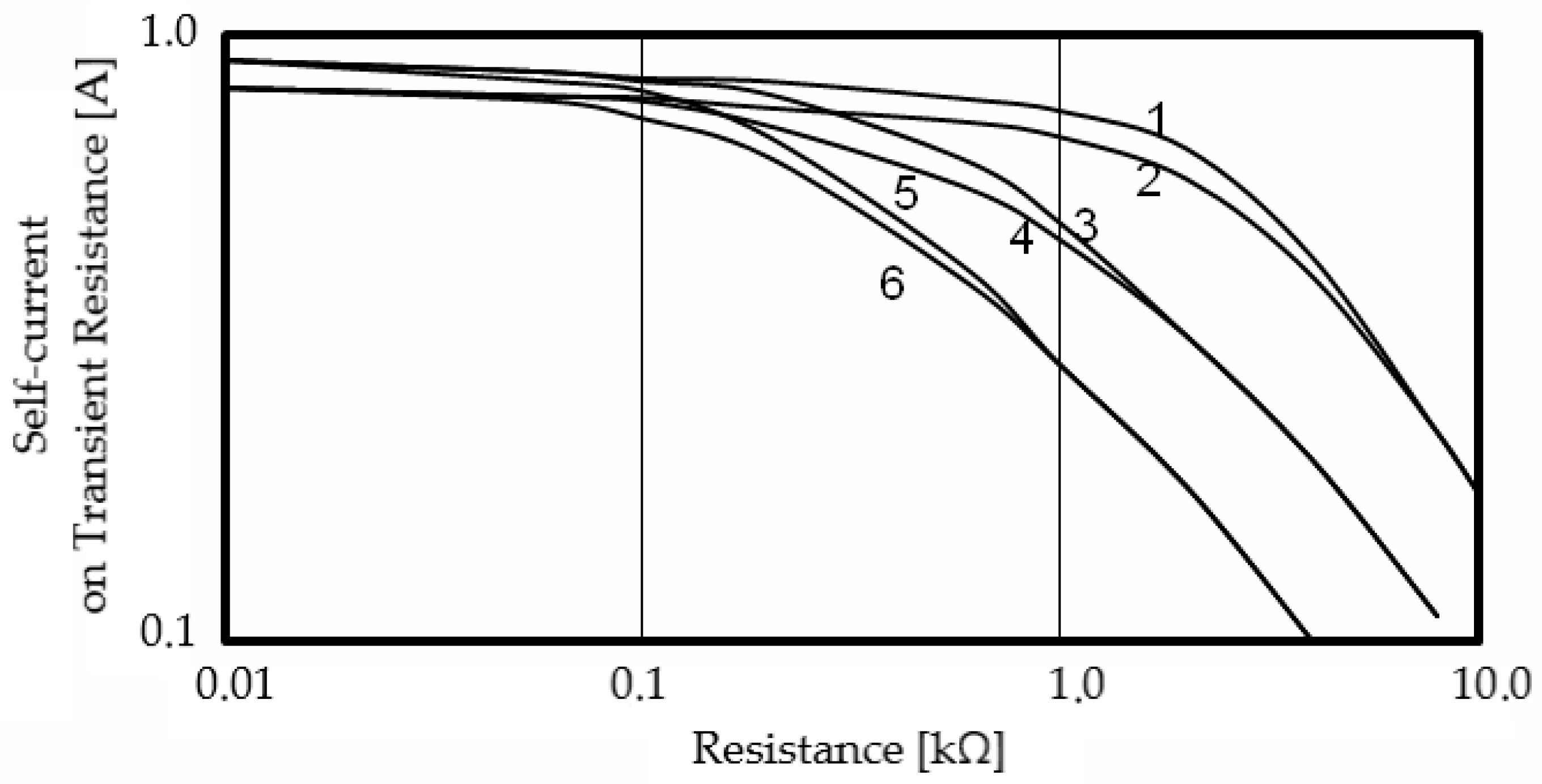

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the characteristic dependencies of the effective value and the angle between the zero-sequence current vector for damage outside the monitored line and the voltage vector of the damaged phase.

Values of the self-current amplitude depending on the transient resistance r at the point of fault for different combinations of insulation capacitance C, resistance R, and equivalent resistance of the adjacent line R1 shows that, at low resistance values (r = 0.01–0.1 kΩ), the self-current reaches its maximum amplitude (0.8–0.9 p.u.), which indicates a strong conductive coupling between the faulted phase and the ground. As transient resistance increases (r = 0.2–1.0 kΩ), the self-current decreases gradually, reflecting a reduction in capacitive leakage and a shift toward resistive current flow. At r > 1.0 kΩ, the current amplitude drops sharply and becomes almost negligible for r ≥ 4.0 kΩ, where values fall below 0.2 p.u. This trend demonstrates a nonlinear inverse relationship between the transient resistance and the self-current magnitude. Moreover, the results show that higher insulation capacitance (C = 3.0–6.0 μF) leads to greater initial current values and slower attenuation, while higher insulation resistance (R = 100 kΩ) causes a faster decline of current with increasing r.

Overall, the data provides a quantitative assessment of the current attenuation mechanism under different insulation conditions. The observed dependencies confirm that the self-current magnitude is primarily governed by the interplay between transient resistance and insulation capacitance, which defines the system’s response to ground faults in isolated neutral networks. The dependence of the self-current on transient resistance for different combinations of network insulation parameters

C (μF),

R (kΩ), and

R1 (kΩ), is presented in

Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Dependence of the self-current on the transient resistance at C (μF), R (kΩ) and R1 (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—1.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 2—1.0; 100.0 and 200.0; 3—3.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 4—3.0; 100.0 and 200.0; 5—6.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 6—6.0; 100.0 and 200.0.

Figure 8.

Dependence of the self-current on the transient resistance at C (μF), R (kΩ) and R1 (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—1.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 2—1.0; 100.0 and 200.0; 3—3.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 4—3.0; 100.0 and 200.0; 5—6.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 6—6.0; 100.0 and 200.0.

The observed dependencies exhibit a strong nonlinear inverse relationship between transient resistance and self-current amplitude. Curves corresponding to higher capacitance values (5–6) display greater initial current levels and a slower attenuation rate, while systems with higher insulation resistance (curves 1–2) show smaller initial currents and a steeper decline with increasing r. These patterns highlight the dominant influence of the network’s insulation parameters on fault current behavior, providing an analytical basis for evaluating ground fault severity and insulation condition in isolated neutral power systems.

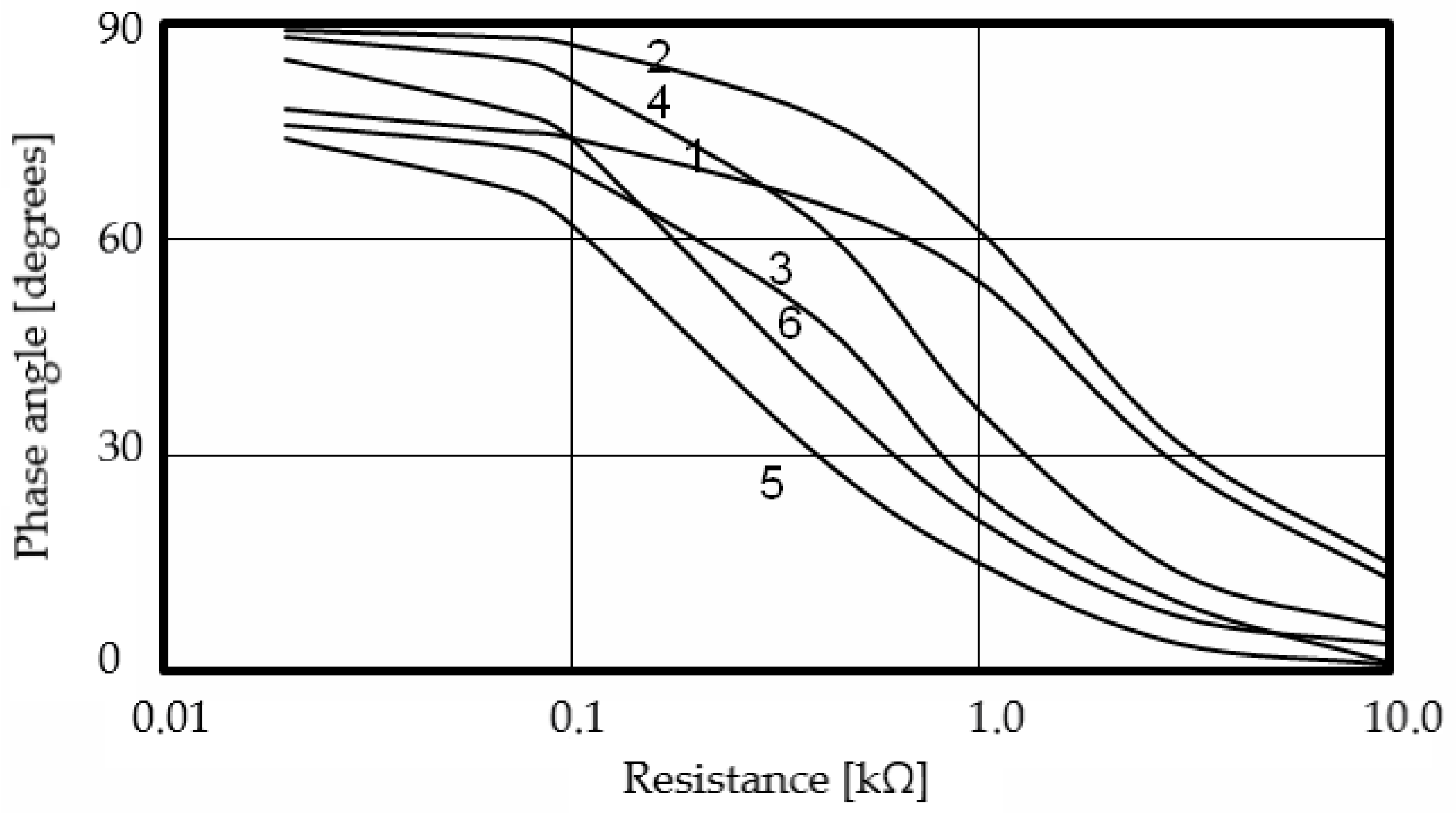

Values of the phase angle of the self-current φ3 (in degrees) as a function of the transient resistance r at the fault location shows, that at low transient resistance values (r = 0.02–0.1 kΩ), the phase angle remains relatively high (74–89°), indicating a predominantly capacitive character of the self-current. In this range, the current vector leads the voltage vector by approximately 90°, which corresponds to the behavior of an isolated neutral network dominated by capacitive leakage currents. As the resistance increases (r = 0.4–0.1 kΩ), the phase angle decreases sharply to 30–77°, reflecting a transition from capacitive to resistive–capacitive behavior. The rate of decrease depends on the capacitance C: higher capacitance leads to faster phase reduction, as the capacitive reactance becomes comparable to the fault resistance.

At high transient resistances (r ≥ 3.0 kΩ), the phase angle drops below 20° and eventually approaches 1–6° for r = 10.0, kΩ, confirming that the current becomes almost purely resistive, and the reactive component is negligible. Overall, the data show a strong nonlinear relationship between the transient resistance and the phase angle of the self-current.

This behavior highlights the sensitivity of the fault current phase to both the insulation parameters and the coupling resistance. The observed dependencies are crucial for identifying the transition from capacitive to resistive fault regimes and for developing diagnostic models of ground-fault dynamics in isolated neutral systems. The variation in the phase angle φ3 with transient resistance for different combinations of insulation parameters

C (μF),

R (kΩ), and

R1 (kΩ), is presented in

Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Change angle φ3 from the transient resistance at C (μF), R (kΩ) and R1 (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—1.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 2—1.0; 100.0 and 200.0; 3—3.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 4—3.0; 100.0 and 200.0; 5—6.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 6—6.0; 100.0 and 200.0.

Figure 9.

Change angle φ3 from the transient resistance at C (μF), R (kΩ) and R1 (kΩ), respectively, equal to: 1—1.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 2—1.0; 100.0 and 200.0; 3—3.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 4—3.0; 100.0 and 200.0; 5—6.0; 10.0 and 50.0; 6—6.0; 100.0 and 200.0.

Overall, the figure demonstrates a strong nonlinear relationship between transient resistance and the phase angle of the self-current. Higher capacitance values (curves 5–6) cause a faster decline in φ3, whereas higher insulation resistance (curves 1–2) stabilizes the phase angle at larger values. These dependencies reveal the gradual transformation of the system’s behavior from capacitive to resistive with increasing fault resistance, offering valuable insight into the diagnostic assessment of insulation and transient fault dynamics in isolated neutral networks.

The analytical and computational results demonstrate that insulation parameters and transient fault resistance critically govern the behavior of zero-sequence voltage, zero-sequence current, and self-current in isolated-neutral distribution networks. The derived dependencies indicate a distinctly nonlinear relationship between the transient resistance and both the magnitude and phase angle of the resulting fault currents. At low resistance values, the network operates in a quasi-capacitive mode, characterized by high current amplitudes and phase angles approaching 90°, which reflects the predominance of displacement currents through insulation. As the transient resistance increases, the system response shifts toward a mixed resistive–capacitive regime, accompanied by rapid current attenuation and a corresponding reduction in phase angle.

These results confirm that the combined effects of insulation capacitance, insulation resistance, and fault-path impedance dictate the electrical response of the network ground-fault conditions. The characteristic curves obtained for zero-sequence and self-currents (

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) provide a solid theoretical basis for diagnosing insulation degradation, evaluating protection sensitivity, and optimizing ground-fault detection settings in isolated and compensated neutral systems. The proposed models and identified patterns can be effectively applied to enhance the reliability of open-pit mining power networks, enabling more accurate identification of fault regimes and improving the resilience of electrical infrastructure operating under harsh industrial conditions.