Advances in North American CCUS-EOR Technology and Implications for China’s Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

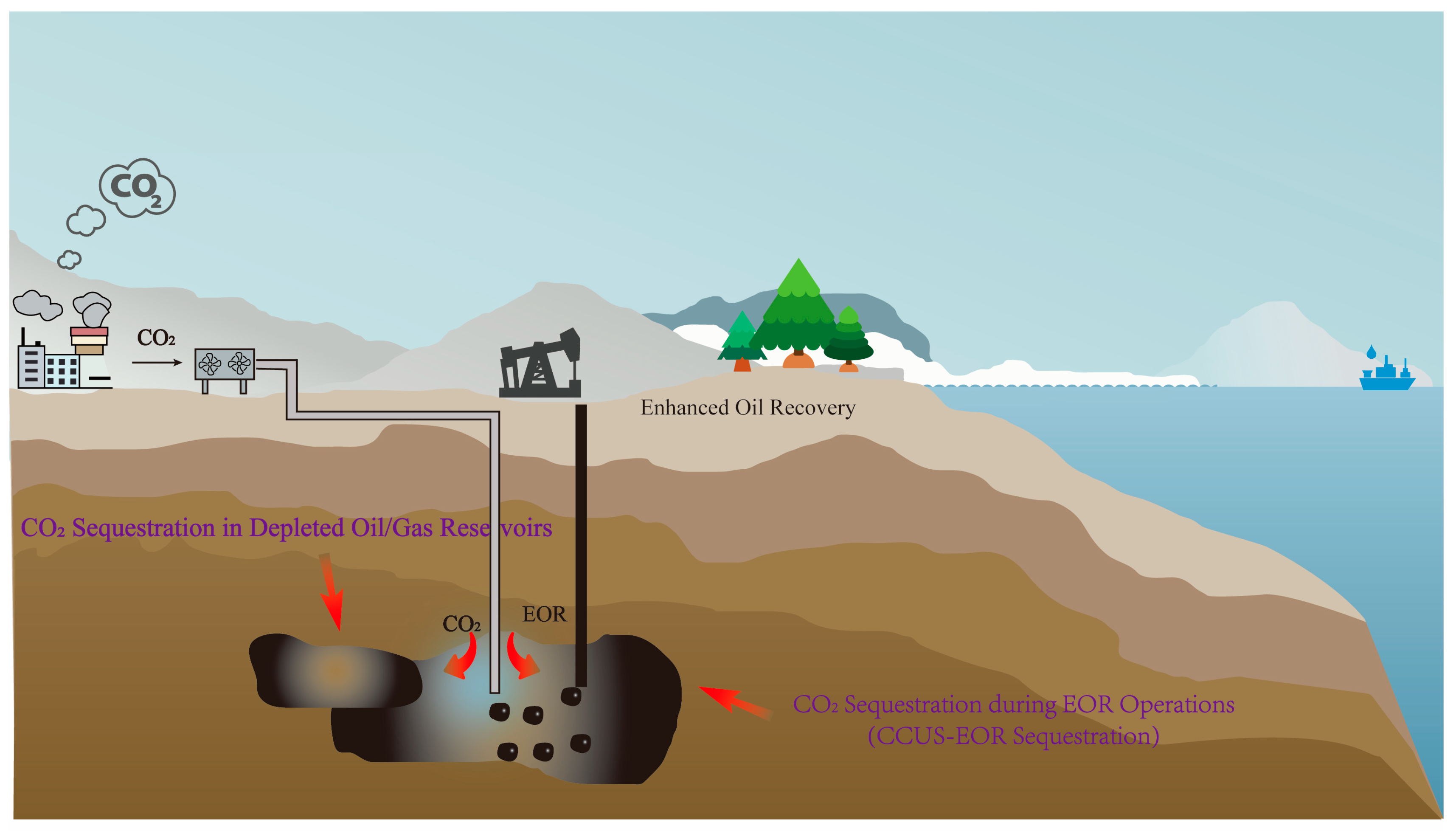

2. CCUS-EOR Technology Process

2.1. CO2 Capture

| CO2 Capture Technology | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applicable Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-combustion Capture | Captured CO2 has high concentration [41]; CO2 is easily separable [42]; Purified hydrogen can be used as fuel for fuel cells and as feedstock for synthesizing high-value chemicals [31,43]; Water consumption is lower [44]. | Separation process equipment requires high investment costs [45]; Gasification processes may generate polluting gases; Existing equipment requires retrofitting [31]. | Integrated Coal Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) power plants, steel, cement, glass industries, etc. [46] |

| Oxy-fuel combustion | Reduces emissions of pollutants such as nitrogen oxides; compared to air combustion, nitrogen oxide emissions decrease by 60–70% [46]; High combustion efficiency, low consumption. | Separating oxygen from air consumes significant energy, impacting overall power plant efficiency [46]. | Combustion systems such as boilers, furnaces, and gas turbines |

| Post-combustion capture | Technologically flexible and cost-effective, applicable for retrofitting existing power plants; additionally removes nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides. | Low partial pressure of CO2 in flue gas, requiring large gas volumes to be treated, resulting in higher costs [44]. | Suitable for existing coal-fired power plants |

| Direct air capture | Flexible site selection reduces subsequent transportation costs. | Expensive equipment, relatively low efficiency | Distributed emission sources (e.g., transportation vehicles) |

2.2. CO2 Transport

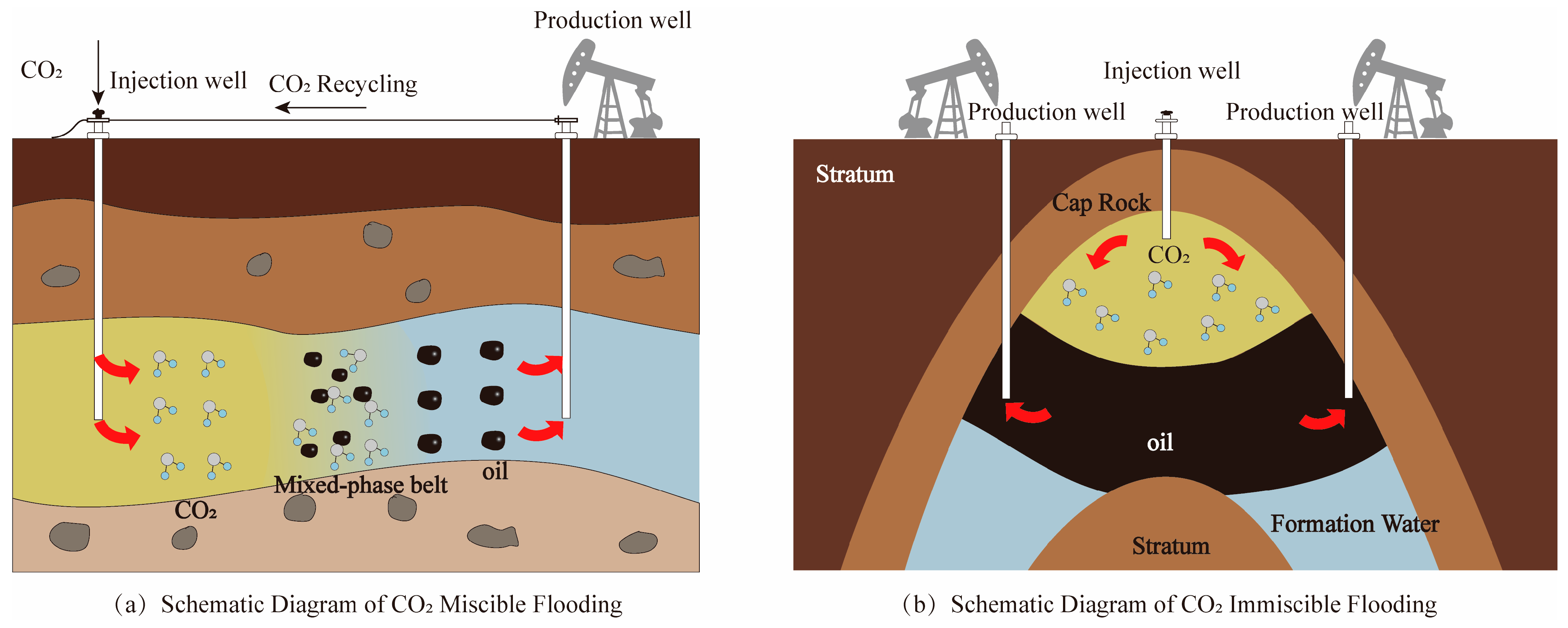

2.3. CO2-EOR Mechanism

2.4. CO2 Geological Sequestration

3. North American CCUS-EOR Technology Advancements and Applications

3.1. Data Sources and Statistical Methods

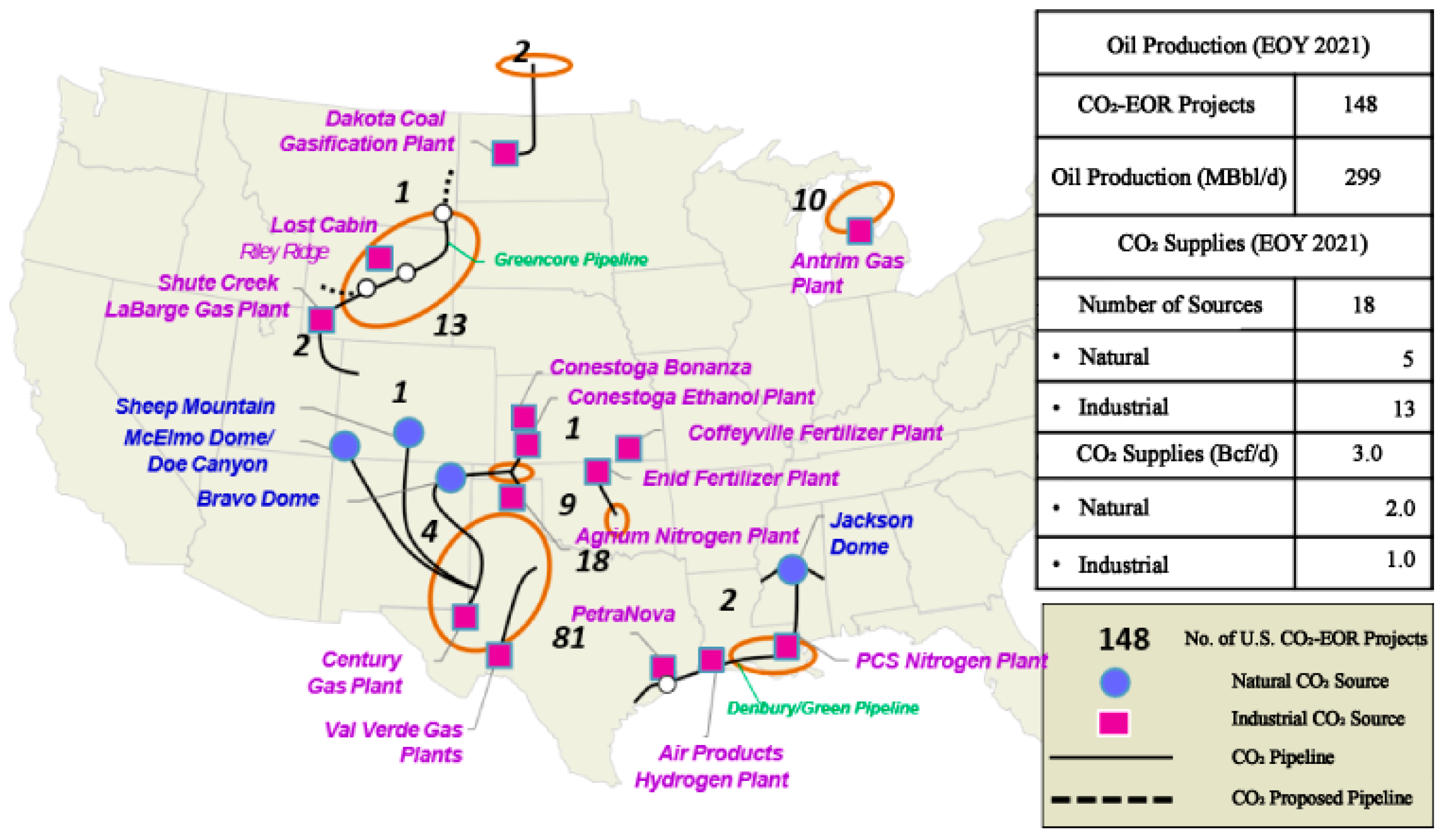

3.2. Overview of CO2 Source Supply in the United States

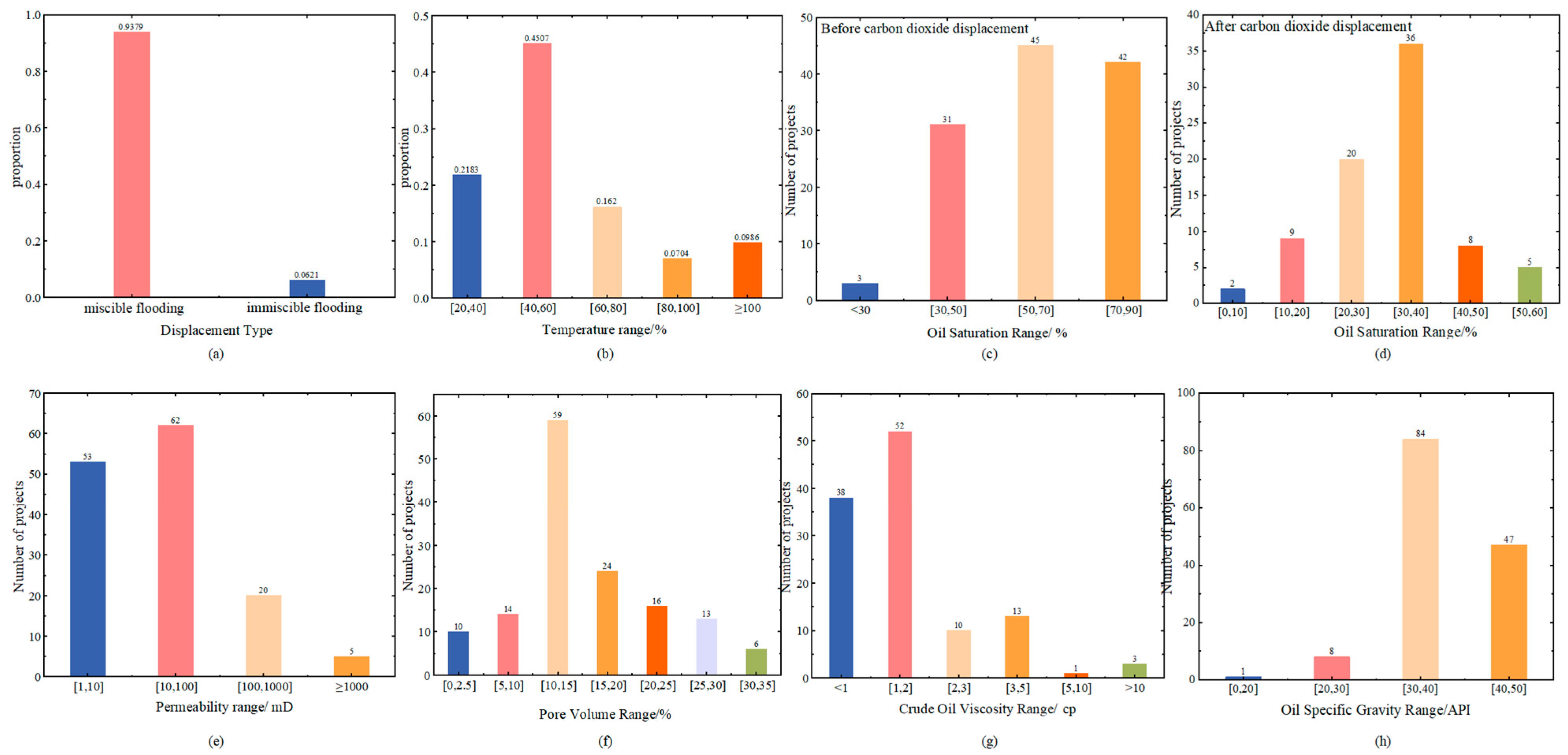

3.3. Analysis of North American CO2-EOR Technical Indicators

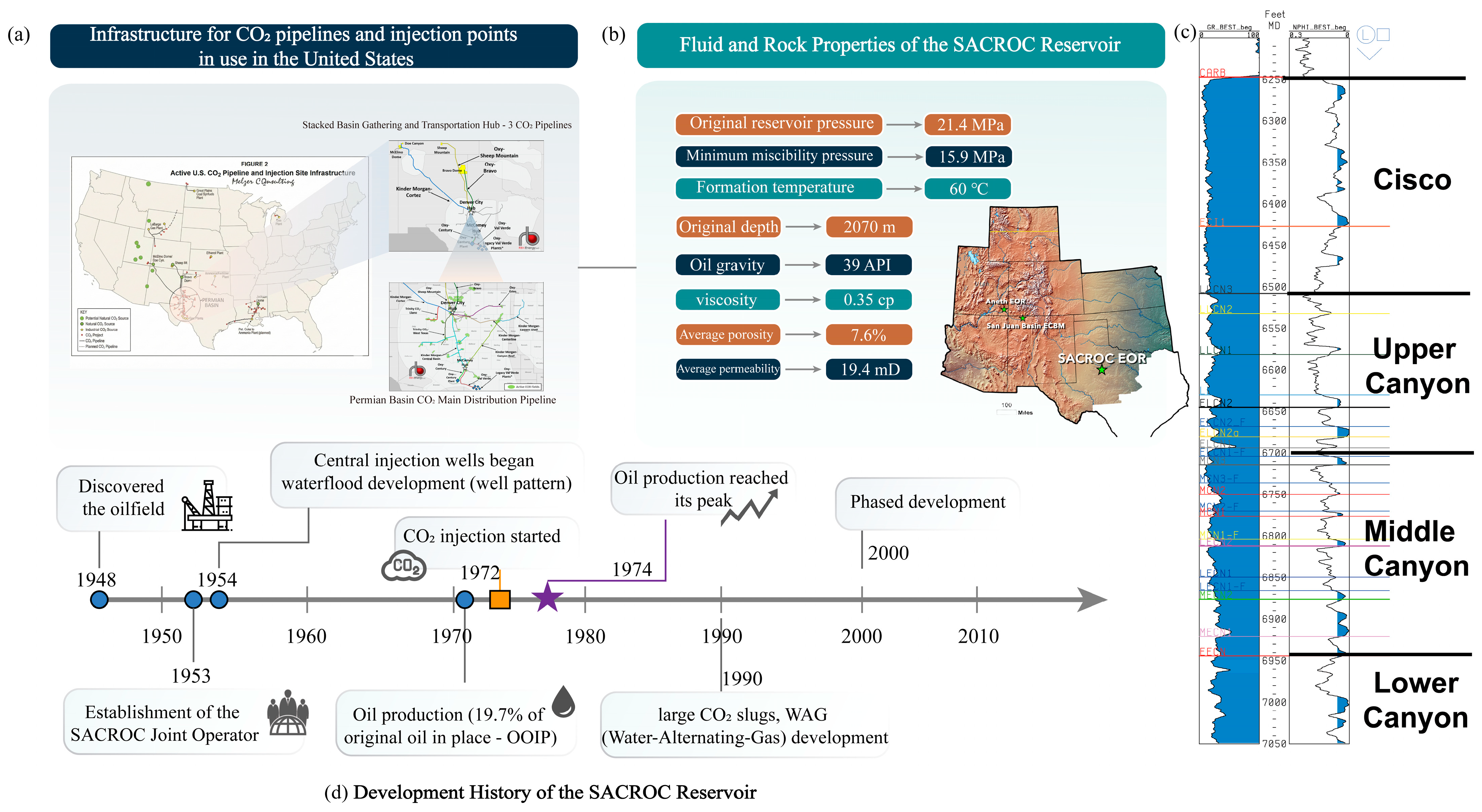

3.4. Key Block Technology Application: Case Study of the SACROC Formation in the Permian Basin

3.5. Scientific Advances in North American CCS-EOR Technology

4. Challenges and Prospects for China’s CCUS-EOR Technology Development

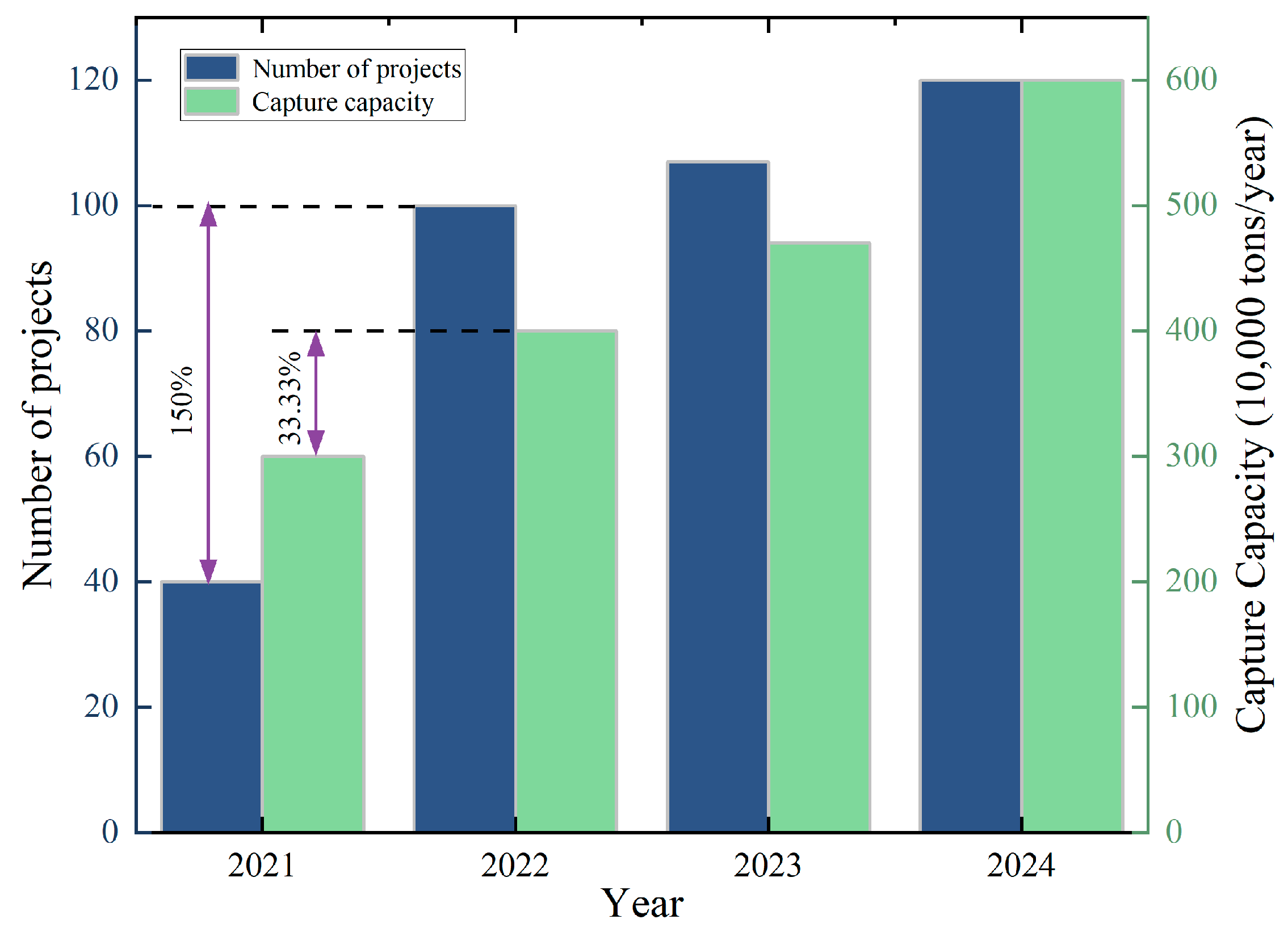

4.1. Current Progress of China’s CCUS-EOR Technology

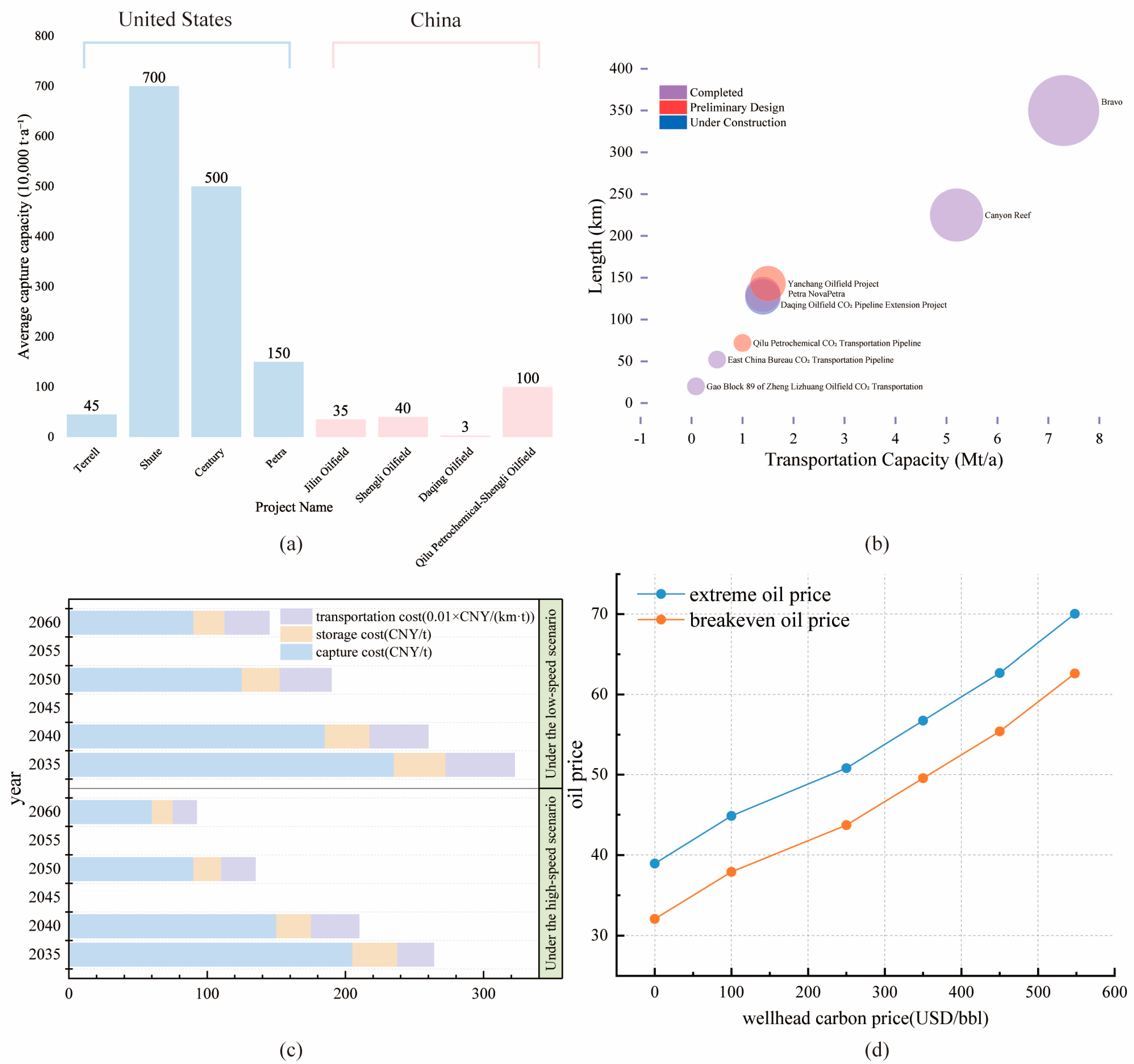

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Key Characteristics of CO2-EOR in China and the United States

4.2.1. Comparison of Typical Project Parameters

4.2.2. Infrastructure and Economic Viability Comparison

4.2.3. Policy Incentive Mechanisms and Oil Price Sensitivity Analysis

4.3. Challenges Faced

4.4. Outlook

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCUS | Carbon capture, utilization, and storage |

| EOR | Enhanced oil recovery |

| DAC | direct air capture |

References

- Hurlbert, M.; Osazuwa-Peters, M. Carbon Capture and Storage in Saskatchewan: An Analysis of Communicative Practices in a Contested Technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Hao, T.; Zhu, J. Discussion on Action Strategies of China’s Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2022, 37, 423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Jacoby, H. The Paris Agreement|MIT Climate Portal. Available online: https://climate.mit.edu/explainers/paris-agreement (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- IEA—International Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.iea.org (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Reisinger, A.R., IPCC, Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 17, ISBN 978-92-9169-160-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fam, A.; Fam, S. Review of the US 2050 Long Term Strategy to Reach Net Zero Carbon Emissions. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltsev, S.; Morris, J.; Kheshgi, H.; Herzog, H. Hard-to-Abate Sectors: The Role of Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) in Emission Mitigation. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, M.V.; Hoadley, S.F.; Young, D.N. Definitive CO2 Flooding Response in the SACROC Unit. In Proceedings of the SPE/DOE Enhanced Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 17–20 April 1988; OnePetro: Richardson, TX, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, L.; Feng, L.; Ma, Y. Comprehensive Evaluation of CCUS Technology: A Case Study of China’s First Million-Tonne CCUS-EOR Project. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Y.; Gao, X.; Xie, J.-J. Comparison and Clarification of China and US CCUS Technology Development. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, J.; Nichols, C.; Adamantiades, M.; Bistline, J.; Huster, J.; Iyer, G.; Johnson, N.; Patel, P.; Showalter, S.; Victor, N.; et al. Could Congressionally Mandated Incentives Lead to Deployment of Large-Scale CO2 Capture, Facilities for Enhanced Oil Recovery CO2 Markets and Geologic CO2 Storage? Energy Policy 2020, 146, 111775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindi, A.; Coddington, K.; Garofalo, J.F.; Wu, W.; Zhai, H. Policy-Driven Potential for Deploying Carbon Capture and Sequestration in a Fossil-Rich Power Sector. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9872–9881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Chen, T.; Ma, Z.; Tian, H.; Meguerdijian, S.; Chen, B.; Pawar, R.; Huang, L.; Xu, T.; Cather, M.; et al. A Review of Risk and Uncertainty Assessment for Geologic Carbon Storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, H.C.; Ramakrishna, S.; Zhang, K.; Radhamani, A.V. The Role of Carbon Capture and Storage in the Energy Transition. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 7364–7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Han, H.; Liu, X. Application and Enlightenment of Carbon Dioxide Flooding in the United States of America. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Vo Thanh, H.; Wood, D.A.; Mehrad, M.; Rukavishnikov, V.S.; Dai, Z. Machine-Learning Predictions of Solubility and Residual Trapping Indexes of Carbon Dioxide from Global Geological Storage Sites. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2023, 222, 119796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.; House, K. Every Dollar Spent on This Climate Technology Is a Waste. The New York Times. 16 August 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/16/opinion/climate-inflation-reduction-act.html (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, S.-Y.; Li, H.; Cai, J.; Olabi, A.G.; Anthony, E.J.; Manovic, V. Recent Advances in Carbon Dioxide Utilization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 125, 109799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Han, H.; Yang, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, G. A Review of Recent Progress of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) in China. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Deng, S.; Li, H.; Kitamura, Y. Cryogenic-Based CO2 Capture Technologies: State-of-the-Art Developments and Current Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shargabi, M.; Davoodi, S.; Wood, D.A.; Rukavishnikov, V.S.; Minaev, K.M. Carbon Dioxide Applications for Enhanced Oil Recovery Assisted by Nanoparticles: Recent Developments. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 9984–9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, C.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Huang, M.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Zhou, H.; Ma, H.; et al. Recent Advances, Challenges, and Perspectives on Carbon Capture. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2024, 18, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Z.; Shaojie, O.; Yingjie, Z.; Hui, S. CCS Technology Development in China: Status, Problems and Countermeasures—Based on SWOT Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, S.M.; Cloete, J.H.; Cloete, S.; Amini, S. Efficient Hydrogen Production with CO2 Capture Using Gas Switching Reforming. Energy 2019, 185, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.; Deng, Y.; Dewil, R.; Baeyens, J.; Fan, X. Post-Combustion Carbon Capture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Luo, L.; Liu, T.; Hao, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhu, T. A Review of Low-Carbon Technologies and Projects for the Global Cement Industry. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 136, 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Li, B.; Chen, D.; Wenga, T.; Ma, W.; Lin, F.; Chen, G. An Investigation of an Oxygen-Enriched Combustion of Municipal Solid Waste on Flue Gas Emission and Combustion Performance at a 8 MWth Waste-to-Energy Plant. Waste Manag. 2019, 96, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczyk, W.P.; Bialecki, R.A.; Ditaranto, M.; Gladysz, P.; Haugen, N.E.L.; Katelbach-Wozniak, A.; Klimanek, A.; Sladek, S.; Szlek, A.; Wecel, G. CFD Modeling and Thermodynamic Analysis of a Concept of a MILD-OXY Combustion Large Scale Pulverized Coal Boiler. Energy 2017, 140, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilberforce, T.; Olabi, A.G.; Sayed, E.T.; Elsaid, K.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Progress in Carbon Capture Technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Hefny, M.; Abdel Maksoud, M.I.A.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Rooney, D.W. Recent Advances in Carbon Capture Storage and Utilisation Technologies: A Review. Env. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 797–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, R.; Yang, B.; Wu, Z. Research Progress on Direct Air Capture of CO2 Technology. Clean Coal Technol. 2021, 27, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahimi, V.; Ho, M.; Croiset, E. From Lab to Fab: Development and Deployment of Direct Air Capture of CO2. Energies 2023, 16, 6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Krishnamoorti, R.; Bollini, P. Technological Options for Direct Air Capture: A Comparative Process Engineering Review. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2022, 13, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, N.; Gomes, K.V.; McCormick, C.; Blumanthal, K.; Pisciotta, M.; Wilcox, J. A Review of Direct Air Capture (DAC): Scaling up Commercial Technologies and Innovating for the Future. Prog. Energy 2021, 3, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, P.; Tan, H. Research Progress on CO2 Capture, Utilization and Storage Technology. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 50, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, S.; Yogo, K.; Goto, K.; Kai, T.; Yamada, H. Advanced CO2 Capture Technologies: Absorption, Adsorption, and Membrane Separation Methods; Springer Briefs in Energy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-18857-3. [Google Scholar]

- Qazvini, O.T.; Babarao, R.; Telfer, S.G. Selective Capture of Carbon Dioxide from Hydrocarbons Using a Metal-Organic Framework. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Song, W.; Yang, P. Current Status and Application Prospects of CCUS Technology-Sci-Tech Innovation for Sustainable Development Research Institute. Available online: https://sisd.org.cn/express/express598.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Sun, N.; Han, S.; Wang, X.; Su, Q.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Yu, X.; Du, S.; et al. Hydrate Technologies for CO2 Capture and Sequestration: Status and Perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 10363–10385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, M.; Adjiman, C.S.; Bardow, A.; Anthony, E.J.; Boston, A.; Brown, S.; Fennell, P.S.; Fuss, S.; Galindo, A.; Hackett, L.A.; et al. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS): The Way Forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1062–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omodolor, I.S.; Otor, H.O.; Andonegui, J.A.; Allen, B.J.; Alba-Rubio, A.C. Dual-Function Materials for CO2 Capture and Conversion: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 17612–17631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Deka, T.J.; Baruah, D.C.; Rooney, D.W. Critical Challenges in Biohydrogen Production Processes from the Organic Feedstocks. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2023, 13, 8383–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhenawy, S.E.M.; Khraisheh, M.; AlMomani, F.; Walker, G. Metal-Organic Frameworks as a Platform for CO2 Capture and Chemical Processes: Adsorption, Membrane Separation, Catalytic-Conversion, and Electrochemical Reduction of CO2. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Al-Shargabi, M.; Wood, D.A.; Rukavishnikov, V.S.; Minaev, K.M. Review of Technological Progress in Carbon Dioxide Capture, Storage, and Utilization. Gas. Sci. Eng. 2023, 117, 205070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajire, A.A. CO2 Capture and Separation Technologies for End-of-Pipe Applications–A Review. Energy 2010, 35, 2610–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Hou, L.; Du, M.; Jia, N.; Lü, W. Research Progress and Development Prospect of CCUS-EOR Technology in China. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2023, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Xie, W.; Ni, S.; He, X. Comparative Study of A106 Steel Corrosion in Fresh and Dirty MEA Solutions during the CO2 Capture Process: Effect of NO3−. Corros. Sci. 2020, 167, 108521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X. Progress in the Application of Mixed Matrix Membranes in CO2/CH4 Separation. Polym. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 41, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, K.R.; Hansen, D.S.; Pedersen, S. Challenges in CO2 Transportation: Trends and Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh Government. A Carbon Capture, Utilisation, and Storage Network for Wales. Available online: https://www.gov.wales/carbon-capture-utilisation-and-storage-network-wales-report (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Enhance Energy; Wolf Midstream. Enhance Energy and Wolf Midstream Sign Agreement to Finance and Construct the Alberta Carbon Trunk Line. Wolf Midstream. 2 August 2018. Available online: https://www.wolfmidstream.com/enhance-energy-and-wolf-midstream-sign-agreement-to-finance-and-construct-the-alberta-carbon-trunk-line/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Pang, S. China’s Longest Carbon Dioxide Pipeline Put Into Operation. Science and Technology Daily. 12 July 2023, p. 1. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=fvaKTeWl6eJ24EByPpFGIW_tn_k9IP3oN9VdPRlAGG4RBVjmkfYpcJV_3MFuM2knsGWWo-4p5pHmvJqjWspL4EqhfTqyb-74eu47ajKRyMwTPZtZu3KF74m4-kWiqfS4Wye3pkctHNvnsKOZ5eDc3OcxFwuLuxATLJRaAxcxWa3ui9N2zbd_ex82fugmaWm7&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese) [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, M.D.; Mukherjee, S.; Brown, S. Linking CO2 Capture and Pipeline Transportation: Sensitivity Analysis and Dynamic Study of the Compression Train. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 2021, 111, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, W.; Franciò, G.; Scott, M.; Westhues, C.; Langanke, J.; Lansing, M.; Hussong, C.; Erdkamp, E. Carbon2Polymer–Chemical Utilization of CO2 in the Production of Isocyanates. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2018, 90, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Miao, X.; Gan, M.; Li, X. Geochemistry in Geologic CO2 Utilization and Storage: A Brief Review. Adv. Geo-Energ. Res. 2019, 3, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Sun, Y.; Yin, H.; Liu, W. Progress and Prospect of Carbon Dioxide Capture, Oil Displacement and Storage Technology. Pet. Sci. Technol. Forum 2024, 43, 58–65. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzjW0Iau1WsIJo3lsMWTzq5AE-80I5xYiBC4-4CklZ_a_sOXZqja28WSGkq9gr15T9oCpx4nDJcctQda1AAxU0TKSaQ2JecZCW4Q5vfgdYVD4DbD82WbK1IaYznHSa3aF4pdhpFZ_V0RkNaOMeLkvlWt-8pOeBksdq5QcgJE47gu3g==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Hao, M.; Song, Y. Research Status of CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery Technology. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2010, 33, 59–63. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYziM-8OSD0CUbfTjxEU2FeRNBRmAZhrYhfkQt3hf-i_7sZ1i5-hdqXTaZunB-CNCWmeGrAx3I1KDyttMiVNh48Y3LxDyryuqULlPFkDVstmD_oDHR40PUrRtz6hop5p8xwBftZzzlkje5sW52RXqW4WE19MNUtIZ_4LjNzBGnz5UBg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Tan, F.; Jiang, R.; Ma, C.; Jing, Y.; Chen, K.; Lu, Y. CO2 Oil Displacement and Geological Storage Status and Prospects. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 475–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, F.; Ma, D.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Y. Progress and Prospect of Carbon Dioxide Capture, Oil Displacement and Storage Technology in PetroChina. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Jiang, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Feng, J.; Chu, B.; Zeng, F.; Zhu, G. Determining CO2 Diffusion Coefficient in Heavy Oil in Bulk Phase and in Porous Media Using Experimental and Mathematical Modeling Methods. Fuel 2020, 263, 116205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Yuan, H.; Yang, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, Y. A review on the mechanism of CO2 in the process of oil displacement. Petrochem. Ind. Appl. 2016, 35, 1–5. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzh8rSe_UVxOQoFkXbmNhxhXQq_04kjsCGKVPAsPEyh7kea3Fxg60Dm8Mc_UtZYiixIxEYgb0DGhXK87vLFZIwIEm5p9FZqQGj-9PUMRa-LBxcnYkP5PSFDTP0Cfp3AFqY0UcbIHJSMkh0jGKtYSQkklEg0zPvAIh9VpY3sYx8ODcQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, G. Numerical Simulation Study on Mechanism and Development Effect of Near-Miscible Displacement with Non-Pure CO2. China Offshore Oil Gas 2020, 32, 77–81. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzgdiJcbde6X6gKsly_hYgPfJLfoPH9bTlu5pbEuoesw6MR8nZJ7msMePsXSCStpzo73FS4nSDqF9TL5B30rpDr1aVMWtKjmL1XpMeY5gs3-7-AmmZGz9kCPdd9gL87gu7fv3Cpy8R74YrWjAwsOLRaJG-B-kZdSZ4VcNk-SMfM1DQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Zhang, Y.-Q.; Yang, S.-L.; Bi, L.-F.; Gao, X.-Y.; Shen, B.; Hu, J.-T.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, J. A Technical Review of CO2 Flooding Sweep-Characteristics Research Advance and Sweep-Extend Technology. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liang, J.; Tuo, L. Development and Challenges of CO2 Flooding Technology. Prog. Fine Petrochem. 2025, 26, 22–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Li, N.; Wang, X. Research Status of CO2 Injection Technology for Enhanced Oil Recovery in Tight Reservoirs. Shandong Chem. Ind. 2022, 51, 133–135. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=fvaKTeWl6eKQUxlAN4mSYgACUeW3A5V78ao6Beg3nAFq4TDEIEm6mDjRWe2S77wQGXVKgpfPrOBwr_DW_Isd5hSwN7BcMn75k-GovrRY3Wp3jk2YjuDIVZSq9oV4yuc2mlAsQ46qFRtNVs5wgR2ndd5qOTP8l0_JFNLYCVdouyY=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese) [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; He, Y. Practice and Understanding of CO2 Flooding in Low-Permeability Reservoirs of Sinopec. Reserv. Eval. Dev. 2021, 11, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Jin, Y.; He, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wu, G. Development and Application of CO2 Flooding Enhanced Oil Recovery Technology for Different Reservoir Types in Sinopec under the Vision of Carbon Neutrality and Carbon Peaking. Pet. Reserv. Eval. Dev. 2021, 11, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L. The Application of Double Tube Pulse Steam Injection Technology in Girasol Oilfield. J. Oil Gas Technol. 2019, 41, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuskraa, V.A.; Godec, M.L.; Dipietro, P. CO2 Utilization from “Next Generation” CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery Technology. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 6854–6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jang, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, J. Prediction of Storage Efficiency on CO2 Sequestration in Deep Saline Aquifers Using Artificial Neural Network. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, R.J.; Vandeweijer, V.P.; Hofstee, C.; Pluymaekers, M.P.D.; Loeve, D.; Kopp, A.; Plug, W.J. The Feasibility of CO2 Storage in the Depleted P18-4 Gas Field Offshore the Netherlands (the ROAD Project). Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 2012, 11, S10–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Li, Y.; Xue, Z.; Liu, Y. Suggestions on the Development of Key Technologies for CO2-Enhanced Oil and Gas Recovery and Geological Storage. Front. Sci. Technol. 2023, 2, 145–160. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzjGF9gzUJnsVTXW5i-mHgyd0ajkQR4wr6V6bV9Xg6G9BTRSqOqRx8bYysY7rPzxH-uTiVdkCDyeaqTseoU4afra32ULs-LOnZ2rRnyW3Sfc0eMTv1xry8_qBNpt_SZ2a4Zuo0TUkGUoZCacrUnrtkvDnXOFSJ4gN8mRExy1akCGmg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Gershenzon, N.I.; Ritzi, R.W.; Dominic, D.F.; Mehnert, E.; Okwen, R.T. Capillary Trapping of CO2 in Heterogeneous Reservoirs during the Injection Period. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 2017, 59, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Chen, C.; Jia, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zha, Y.; Wang, R.; Meng, Z.; Wang, H. Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) in Oil and Gas Reservoirs in China: Status, Opportunities and Challenges. Fuel 2024, 375, 132353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Jia, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Qin, J.; Tang, Y. Study on Calculation Method for CO2 Storage Potential in Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Pet. Reserv. Eval. Dev. 2021, 11, 858–863. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=fvaKTeWl6eLX9JWP2wvk6WGsEyfOy-pkW_5eKiL5tMYhEKW5cCoZHuZQZYfqdD8ZhPnDDkgpAiAwjYbSOSFXjPKL8SLGrtWvLUlBslQDkdCvCUiaA14e1XDBQg-lco2pKJ8A2FEJPbOvwujZmckcdpZzaYwRRq5SZk4Wbzi0YQtsNG60LG6u1w==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese) [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Yao, Z. A State-of-the-Art Review of CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery as a Promising Technology to Achieve Carbon Neutrality in China. Environ. Res. 2022, 210, 112986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, A.; Ali, M.; Patil, S.; Aljawad, M.S.; Mahmoud, M.; Al-Shehri, D.; Hoteit, H.; Kamal, M.S. Comprehensive Review of CO2 Geological Storage: Exploring Principles, Mechanisms, and Prospects. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 249, 104672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, T.M. Carbon Dioxide Emissions, Capture, Storage and Utilization: Review of Materials, Processes and Technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 89, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannis, S.; Lu, J.; Chadwick, A.; Hovorka, S.; Kirk, K.; Romanak, K.; Pearce, J. CO2 Storage in Depleted or Depleting Oil and Gas Fields: What Can We Learn from Existing Projects? Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 5680–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminu, M.D.; Nabavi, S.A.; Rochelle, C.A.; Manovic, V. A Review of Developments in Carbon Dioxide Storage. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 1389–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrell, P.M.; Fox, C.E.; Stein, M.H.; Webb, S.L. Practical Aspects of CO2 Flooding; Society of Petroleum Engineers; OnePetro: Richardson, TX, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-55563-096-6. [Google Scholar]

- Advanced Resources International, Inc. U.S. CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery Survey 2021 Update. Available online: https://www.eoriwyoming.org/projects-resources/publications/publications/314-co2-eor-survey-update-2021 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Advanced Resources International, Inc. The U.S. CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery Survey. Available online: https://www.adv-res.com/pdf/ARI-EOY-2023-CO2-EOR-Survey-JUL-22-2025.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Hill, L.B.; Li, X.; Wei, N. CO2-EOR in China: A Comparative Review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 2020, 103, 103173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Tang, Y.; Pan, Y. Re-discussion on the Development of Reservoir Engineering Concepts and Development Modes for CO2 Flooding to Enhance Oil Recovery. Pet. Reserv. Eval. Dev. 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, M. Study on Influencing Factors of Technical Effects of CO2 Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Inn. Mong. Petrochem. Ind. 2019, 45, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. Study on the Influence of Different Permeabilities on the Oil Displacement Effect of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. China Pet. Chem. Ind. Stand. Qual. 2018, 38, 114–115. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzjcvQN-VeMVzQ3BpCCxhB_dJxPC-foCQm0o6likMARYBeOB6Z2-gju6a9PTxqob4EZW2CWseD3i542c26_DrUD7pJlxk96MLmpAm2JBrM8mKxLApGrWfh3b5i-gGFDjAJuWueD4-aww9K3eQsFq_p0XCEcmqs5Z7Vdh7Ttvhznujw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Zhanbolat, Z. Study on Influencing Factors of CO2 Flooding in Low-Permeability Multi-Layer Reservoirs—A Case Study of the Mao 3 Reservoir. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Wu, X.; Hou, Y.; Hou, Z. Mechanism and influencing factors of CO2 miscible flooding in low-permeability reservoirs. J. China Univ. Pet. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 35, 99–102. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzguHGMMDy_0wet59Tbums9HgIYLbilWtPW7OYG7rTo0_44hje0ABMOscUvUlgDcoA6O2sevIXbGcRsIsoNzzw-BfFInhvAER4UVCUSnxLj6W4irVEECRpSKd8ods15JiqVj_cmKDypRiE41VIhzi25gO1wh5LIH95jj19l7p1ZRHQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Sun, Z. Study on Influencing Factors of CO2 Flooding Effect. Master’s Thesis, Daqing Petroleum Institute, Daqing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Zheng, W.; Baihly, J.; Dwivedi, P.; Shan, D.; Utech, R.; Miller, G. Permian Basin Production Performance Comparison Over Time and the Parent-Child Well Study. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 5–7 February 2019; p. D021S004R004. [Google Scholar]

- Kokal, S.; Al-Kaabi, A. Enhanced Oil Recovery: Challenges & Opportunities; Environment and Sustainability: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bidhendi, M.M.; Kazempour, M.; Ibanga, U.; Nguyen, D.; Arruda, J.; Lantz, M.; Mazon, C. A Set of Successful Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery Trials in Permian Basin: Promising Field and Laboratory Results. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 22–24 July 2019; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Denver, CO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Melzer, L.S. Carbon Dioxide Enhanced Oil Recovery (CO2 EOR): Factors Involved in Adding Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) to Enhanced Oil Recovery; Center for Climate and Energy Solutions: Arlington, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Basin Oriented Strategies for CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery: Rocky Mountain Region|Electronic University Archive. Available online: https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=213298 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ryan, W.J.; Edwards, M.A. Infrastructure to Enable Deployment of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E8815–E8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Ma, D.; Li, J.; Zhou, T.; Ji, Z.; Han, H. Progress and Prospects of Carbon Dioxide Capture, EOR-Utilization and Storage Industrialization. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, G.; Shahab, M.D.; Mohammad, M. Smart Proxy Modeling of SACROC CO2-EOR. Fluids 2019, 4, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Progress and Development Direction of Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage Technology in China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2024, 45, 325–338. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYziKe6JVoyCDjHOItYNvozRpEvLbf0oBk8qQVFnVvsq01-Gr6El1_qj954NJjpktunDAY-rYNOoVpQ7Zxk923IppqLebuhEM7A1Nc5qlsrOFxBpoRo_kZ6fV9Pn-SuH0AL4shgvHegb8noOLVTQ7yRTgZfSfzxXsUe8NvzDlzsCTtw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- The World’s Largest Chemical Looping Carbon Capture Equipment has Successfully Passed the Test; Chemical Industry Management: Jalan Samulun, Singapore, 2024; Volume 88.

- Cai, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, M. Progress and Prospect of CCUS-EOR Engineering Technology. Pet. Sci. Technol. Forum 2023, 42, 49–56. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzgWQR4elcYCam6Yew2nXnW3nOARcmOsLqE_NFn_mfd49EzzUxwnGmUg5S33pCjtnSHb0xzKfJTnakOSWZLxm8qvLo9MUc0B7mxAnPH7BEnKqwUCM9cIMpkVrnqQorrSw5PG28h-NkTV71jcTAi6ETJ5ag5m8ejKnrcXdTaFTdqUYg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Chinese Society for Environmental Sciences Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage Professional Committee. China Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage Progress Series Report 2025—New Progress, New Stage, New Trends; Chinese Society for Environmental Sciences Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage Professional Committee: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Lü, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Ren, M. Current Status and Future Research Directions of CO2 Flooding Technology in Shengli Oilfield. Reserv. Eval. Dev. 2020, 10, 51–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, P.; Dai, L.; Sun, L. Developing gas injection technology to enhance oil recovery. J. Southwest Pet. Inst. 2000, 3, 41–45. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYziylwvdDsnoV1n_AMt2IpdyK9HI2t3hQLsgZ69ZgGLy4ctA9-XESeRUvG1ViLscdXrhHaA7KwemIvgQ8yqzPxBkRBnNsTvJM_C15j3z0CZP2KFHQbae7VYvdFrzCuYNntCw5_kaio6Dd0SGq8Du6x1Y4dQXRDpQ8yjbgNmxV1Qb1w==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research, Beijing Institute of Technology. Layout Planning and Outlook of China’s CCUS Transportation Pipeline Network-Annual Forecast Report-Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research. Available online: https://ceep.bit.edu.cn/zxcg/ndycbg/43a64c9e68ad4d09a117899900440d46.htm (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Hu, H.; Guo, C.; Luo, M.; Ma, J.; Guo, F.; Huang, Z. Current Development Status, Economic Benefits and Future Prospects of the CCUS-EOR Industry. China Min. Ind. 2025, 34, 190–203. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzguNWyFVnbUYqlpMmJSjmzzy39R3zFACb7UshuRVyEGh5l3kHwmAbwIIrVdmiuObtpmd_zeUNbWL3G23dfcFd8OaanxnQvLcQiXXLoFiR_c_yj1RdBeqyrP6vqbY4KXU-G9i9HQ1uj781rZ0FCuxKLpGMRpBQ7c5K_lDAoqCMt6Kw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Yang, J.; Luo, M.; Luo, J.; Fu, N.; Yang, L. Research on Economic Benefits and Case Analysis of CCUS-EOR Projects under the Background of “Double Carbon”. Pet. Sci. Technol. Forum 2025, 44, 98–106. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzgXtwUCJIOVp3cCzKiR8N5YQ7rwPlfFDqEUcsODTqG8UT-bcaZB30E3f7BogKNNNoz3mK1L4fRQRdBQpbm4Vl-g5JOigojLQKb9acZVmiYy_sBeW-xq-oonSLBI50RrImcX88adfeUPI7TI4TIsPPTU1Dl70d0TQRwKEhMI4nSQDA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Lun, X.X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, B. Global innovations in carbon dioxide capture, utilization, and storage technology. J. Saf. Environ. 2025, 25, 3362–3370. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=fvaKTeWl6eL9tJ_N04-h_peLv4Dzz2PNpeT4APO-q3tZRLcwx8wCElBCvy-R0Sjgd7-EwEMxZ7c927JoWaEWVXh3ucUHrj5NUHXeeZcoZK055VkPsmczzurFgGELrAM78oV4KevXjV6qYrU9chV0jNa2nu2YwmS-BMzUbNEXtx0=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese) [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.J.; Zhang, J.J.; Yang, F.; Wang, F.; Liu, M.M.; Gong, Y.P.; Fan, Z.N.; Fang, Q.Q.; Li, Q.F.; Chen, H.F. Progress and future development trend of CO2 pipeline transportation technology. J. Nanjing Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 58, 944–952. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhang, X.; Peng, X.; Da, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xiang, X.; Kong, J.; Fan, J. Research on Historical Development Experience of International CCUS Policy Systems. Clean Coal Technol. 2025, 31, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingping, S.; Xinwei, L.; Qiujie, L. Methodology for Estimation of CO2 Storage Capacity in Reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2009, 36, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Xin, C. Research on CO2 Storage Capacity in Reservoirs. Unconv. Oil Gas 2020, 7, 72–76. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzhXh1R-lVl_HctE2KjFc8YSPo-qNYL__QqNETs7M1bwqfMjYQ-qcUUQJckTvhRvdukTxc7z6S435nlAzhnJQHhLV2mJVL-3rQwwI1y_Crt6JGd-3aO1HBBIi8kTwwDsGIYU3Ppo12YAbrrRkPdRr1fcb7p8AFgwjpMXa5RvrVwETQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Li, P.; Feng, Q. Numerical Simulation Study on CO2 Flooding and Storage in Low-Permeability Reservoirs Considering Sealing Mechanisms. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Petroleum and Petrochemical Technology Conference (IPPTC), Beijing, China, 25 March 2025; pp. 406–413. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Xiong, Y.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y. A synergistic evaluation method for CO2 flooding and storage in low-permeability and tight oil reservoirs. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2023, 30, 44–52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liao, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, C. Evaluation Model of Carbon Dioxide Storage Potential and Determination of Key Parameters. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2013, 20, 72–74. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzjRxJlp8R3pqmFOMw-sgp3A-opOufQDOsdByd2RrYe94Rz7fXMuwxUiVvUsCoYJqkZigGPJfZYwXZaM9BvmiLH5bLk-TJcZ0tbmV2au-Fg9gYcq7YCtr8wh0tlVka0ceiNokHtoztdPY9Wywd4e-gPDGntSM6Kv2MMNfZiDLGeD-A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Liu, B. Challenges and Countermeasures for Oil and Gas Field Enterprises in Promoting the Application of CCUS Technology. Pet. Sci. Technol. Forum 2022, 41, 34–42. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzgHBQyCm9IqKGmtotWm4jtDN3uB__39YA_XIVhTpNw9B8DfEZBDs4eZTp-MQe7Jzud-_7psdjQFy8CnkO4bamTDQ40t2j5CUS-P_vZGEBNoMmIqcESeRVJ0yMnzR4ssQ7VYAFXbTko2TpttR74VU2hNveI5HvDCDq__pfadQqtj1g==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- “Annual Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) in China (2023)” released. Polyvinyl Chloride 2023, 51, 42. Available online: https://www.acca21.org.cn/trs/000100170002/16690.html (accessed on 30 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Yuan, S.; Ma, D.; Li, J.; Zhou, T.; Ji, Z.; Han, H. Industrialization Progress and Prospect of Carbon Dioxide Capture, Oil Displacement and Storage. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 828–834. [Google Scholar]

| Injection Method | Principle | Advantages and Disadvantages | Typical Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous gas injection production | Continuously inject CO2 to replenish energy for the formation. | Simple to operate; can quickly replenish energy to the formation. However, it consumes a large amount of CO2, and is prone to gas channeling affected by production pressure differences and fractures. | Block 38 of Subei Basin Muma (China); Petra-Nova (USA) [67] |

| Water-Air Alternation (WAG) | Water preferentially enters high-permeability channels, increasing the seepage resistance of gas and forcing CO2 to flow toward low-permeability areas. | CO2 can enter low-permeability zones and small-pore throats, expand the swept volume, and delay gas channeling. However, water injection in low-permeability reservoirs is difficult (high startup pressure), and the water shielding effect prevents the mobilization of remaining oil at the wellbore. | Caoshe Oilfield in Subei Basin |

| CO2 Huff and Puff | An unstable pressure field forms between high-permeability and low-permeability areas, with continuous changes in flow direction, leading to fluid redistribution. During well shutdown, CO2 can fully contact crude oil. | Interferes with the advancement of the CO2 front, delays gas channeling, gives full play to CO2 diffusion, and increases swept volume. However, parameters such as gas injection rate, cycle, and gas slug need to be optimized. | Block Q7P1 of Jiangsu Oilfield [68] |

| Pulsed Gas Injection | Create an unstable dynamic environment through pressure field fluctuations, suppress front expansion, and delay gas channeling. | CO2 miscibility can be achieved by controlling pressure. However, it is not suitable for fracture-vuggy reservoirs, as CO2 tends to channel along fractures due to pressure fluctuations. | Girasol Oilfield [69] |

| Project | Funded Entity | Focused Technology | Web Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning-Based Completion Optimization for CO2 Injection Wells | University of North Dakota | Improving Displacement Profiles and Enhancing Monitoring | https://netl.doe.gov/node/9773 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| Chemical-Assisted CO2 Displacement | Battelle Memorial Institute | Fluidity Control, Enhanced Multiphase Flow | https://netl.doe.gov/node/9504 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| CO2 Enriched Gas Enhanced Recovery | University of North Dakota | Enhanced Multiphase Flow | https://netl.doe.gov/node/11785 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| Optimization of Oil-Water Transition Zone Development | University of Texas at Austin | Improving Displacement Profiles, Strengthening Monitoring, and Enhancing Reservoir Simulation | https://www.netl.doe.gov/node/1426 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| CO2 Viscosity Enhancers | University of Pittsburgh | Fluidity Control, Enhanced Displacement Profiles, and Improved Reservoir Modeling | https://netl.doe.gov/node/2635 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| Formation and Distribution of Oil-Water Transition Zones | University of Texas at Austin (PB) | Enhanced Reservoir Simulation | https://netl.doe.gov/node/2686 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| Next-Generation CO2 Flood Reservoir Simulator | University of Texas at Austin | Advanced Reservoir Simulation | https://netl.doe.gov/node/2717 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| CO2-EOR Reservoir Planning Software (COZView/COZSim) | NITEC | Advanced Reservoir Simulation | https://netl.doe.gov/node/2714 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| Nano-Foam Enhanced Oil Recovery | New Mexico Tech | Flow ability Control, Enhanced Displacement Profile | https://netl.doe.gov/node/2695 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| Aerosol Surfactant Foam | University of Texas at Austin | Flow Control, Enhanced Displacement Profiles, Enhanced Reservoir Simulation | https://netl.doe.gov/node/2699 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| SPI Gel | New Mexico Tech | Fluidity Control, Improved Displacement Profile | https://netl.doe.gov/node/3861 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| Water-Soluble Surfactant Foam | University of Texas at Austin | Flow Control, Improved Displacement Profile | https://netl.doe.gov/node/3945 (accessed on 25 August 2025) |

| Country | Typical Project | Permeability (mD) | Porosity (%) | Reservoir Depth (m) | Reservoir Temperature (°C) | Oil Viscosity (cP) | API Gravity (°) | Displacement Regime | Recovery Factor Increase (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | SACROC | 19.0 | 9.2 | 2040 | 57 | 0.7 | 40 | Miscible Flood | >15.0 |

| Wasson | 3.0 | 9.41 | 1500 | 41 | 1.2 | 33 | Miscible Flood | 17.2 | |

| Salt Creek | 52 | 19.0 | 670 | 38 | 0.6 | 37 | Miscible Flood | >15.0 | |

| China | Caoshe Oilfield | 46 | 14.8 | / | 104 | 12.8 | 29.5 | Miscible Flood | 3.25 |

| Shengli Oilfield Block Ga89-1 | 4.7 | 12.5 | 2700–3100 | 126 | 1.59 | 60.2 | Near-Miscible Flood | 5.4 | |

| Sulige Block Ma38 | 15.7 | 16 | / | 81 | 12.3 | 36.8 | Immiscible Flood | 1.14 | |

| Zhangjia Oilfield Block Zhang1 | 5.0 | 17.0 | 3200 | 112 | 1.7 | 45.4 | Miscible Flood | 4.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, K.; Gao, M.; Yu, H.; Wei, J.; Song, Z.; Shi, J.; Jiang, L. Advances in North American CCUS-EOR Technology and Implications for China’s Development. Energies 2025, 18, 6406. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246406

Tan K, Gao M, Yu H, Wei J, Song Z, Shi J, Jiang L. Advances in North American CCUS-EOR Technology and Implications for China’s Development. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6406. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246406

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Kesheng, Ming Gao, Hongwei Yu, Jiangfei Wei, Zhenlong Song, Jiale Shi, and Lican Jiang. 2025. "Advances in North American CCUS-EOR Technology and Implications for China’s Development" Energies 18, no. 24: 6406. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246406

APA StyleTan, K., Gao, M., Yu, H., Wei, J., Song, Z., Shi, J., & Jiang, L. (2025). Advances in North American CCUS-EOR Technology and Implications for China’s Development. Energies, 18(24), 6406. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246406