The erosion modelling in this work is based on a physics-based LEE model. In the model, the turbine blade’s leading-edge layer structure is simplified by assuming it consists of only two primary constituent layers: an outer protective coating and an inner structural reinforcement layer. This simplification is motivated by three key factors: first, it enables a concise erosion classification system, as presented in

Table 1; second, it facilitates the classification of erosion in the field; and third, it enables the erosion modelling approach discussed in

Section 2.1.1. The category is defined by erosion in the outer 5% of the blade length, where the erosion is expected to be most severe due to the high speed at the tip. Towards the root it will generally decline in severity.

2.1.1. Physics-Based Modelling of Leading Edge Erosion

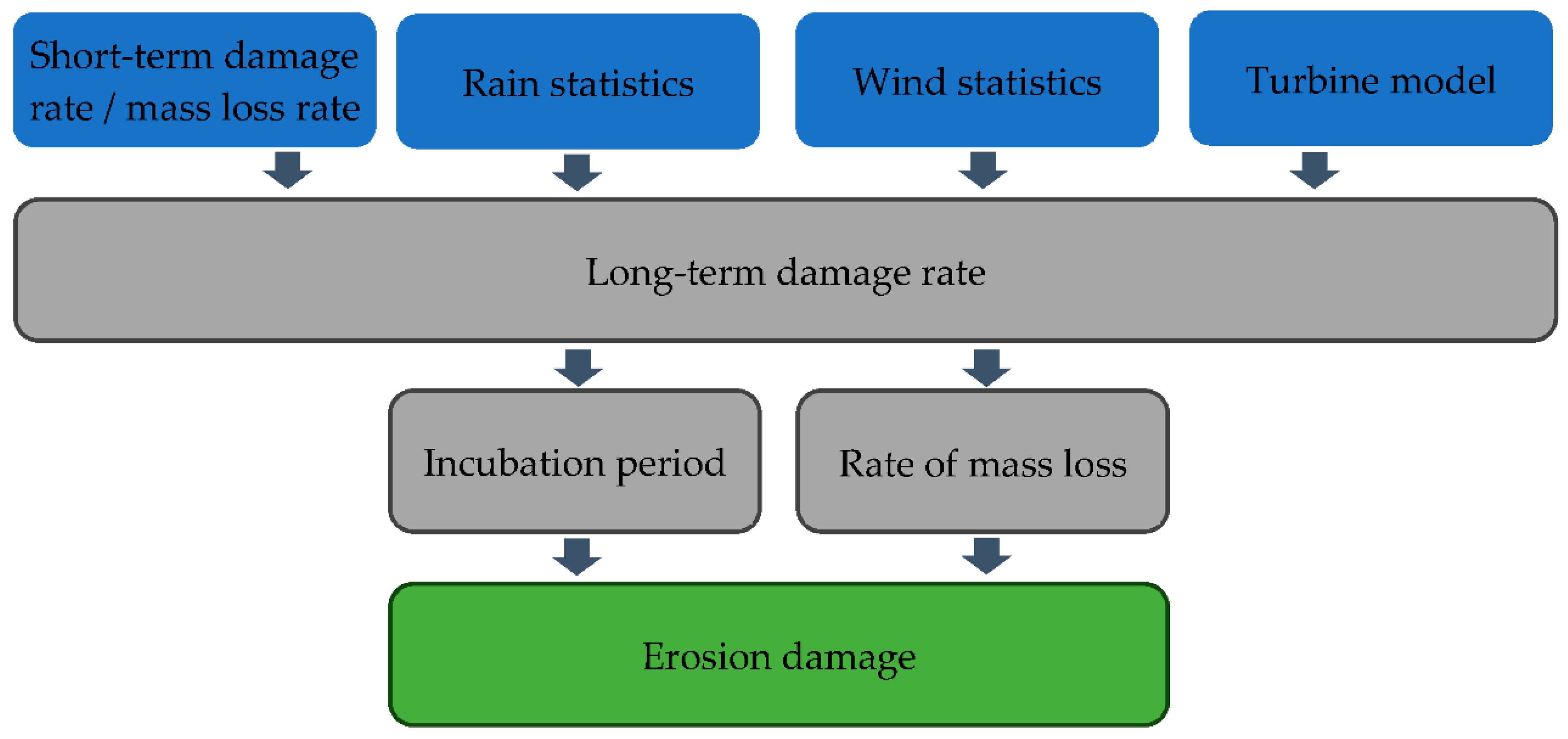

To model the physical process of rain erosion initiation and progression for a specific site, the method developed by Verma et al. [

40] is used, where the probability distribution of wind and rain statistics are integrated into the Springer model [

29] to produce a long-term average damage rate to predict erosion initiation for a specific wind farm site and turbine. Assumptions of this model include the following: 1. the material acts linearly elastic; 2. erosion from solid particles such as sand and hail are neglected; 3. sequence effects in fatigue are neglected; and 4. the material architecture of a turbine blade’s leading edge is assumed to consist of only two main layers, an outer coating and inner structural reinforcement material. We have extended Verma et al.’s [

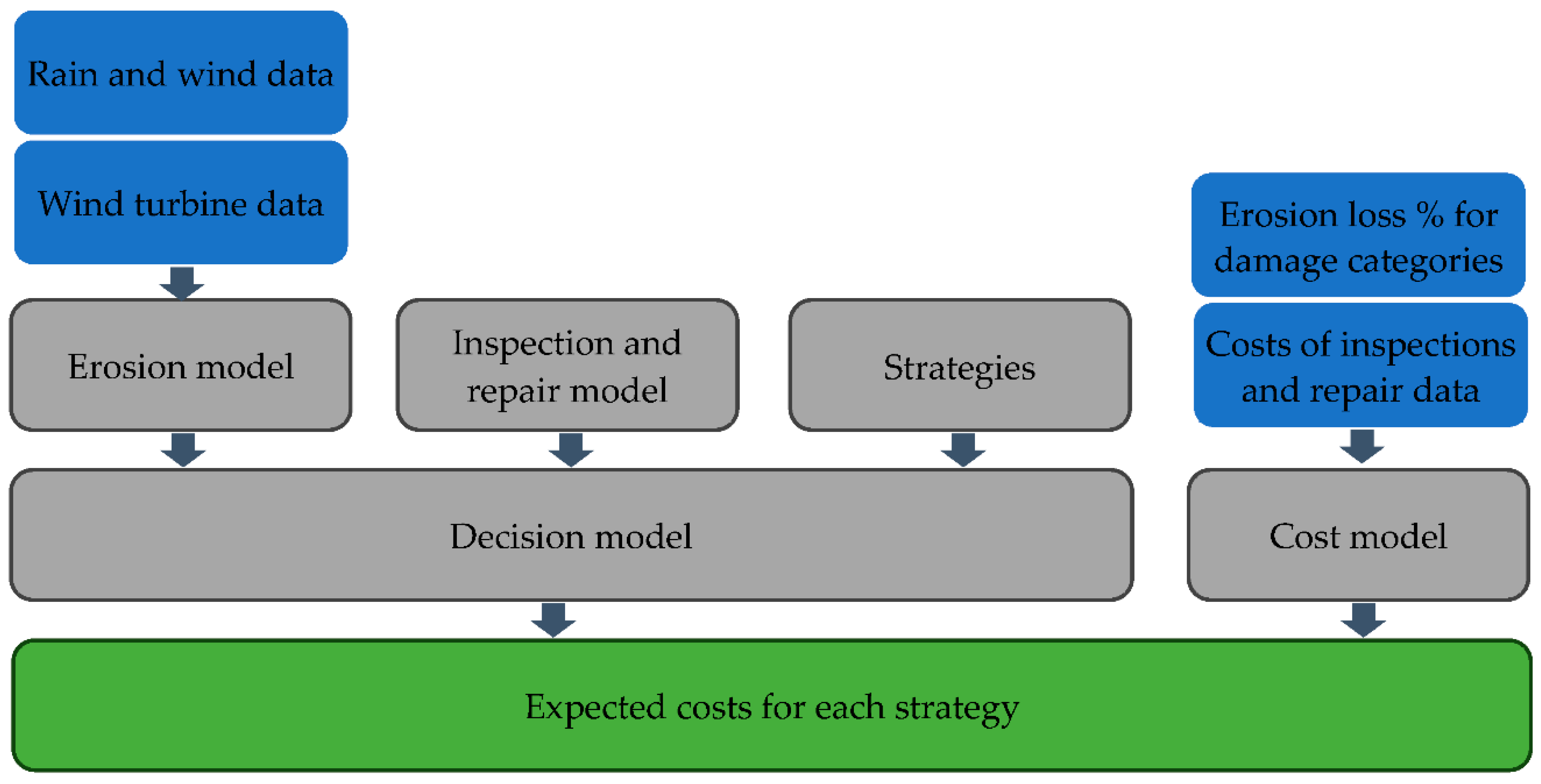

40] method to include erosion of coated materials (instead of a single homogeneous material) and to predict mass loss rate in addition to damage initiation. A brief explanation and mathematical description of the site-specific damage initiation and progression model is presented below. An overview of the calculation procedure is shown in

Figure 2.

The damage initiation phase is split into two models: a damage initiation model for the coating, and a damage initiation model for the substrate. Using Springers model for coated materials the dimensionless number of impacts until damage initiation,

, is calculated as:

where

S is the erosive strength of the coating material,

is pressure felt at the interface of the rain droplet and coating,

is the number of reflections that occur while the droplet is impacting the coating, and

is the relative impedance between the substrate and the coating. A similar process is used to calculate the dimensionless number of impacts until damage initiation of the substrate:

The dimensionless number of impacts until damage initiation is then converted into number of impacts until failure per unit area with the following equation, where

is the diameter of the rain droplet.

Another key component to fatigue analysis is determining the rate of loading, in this case the rate of rain droplet impacts on the leading edge,

. To calculate this Equation (4) is used, where

q is the number of rain droplets per metre cubed, which is dependent on droplet diameter, wind speed

, and rain intensity

I.

is the velocity at which the rain droplets impact the blade leading edge and is dependent on droplet diameter and wind speed.

is the impingement efficiency and is dependent on the droplet diameter.

With both the impacts until failure and impact rate calculated, Palmgren–Miner’s rule can then be applied with Equation (5) to determine the “short-term damage rate” with units of

. The short-term damage rate is computed for both coating and substrate materials.

Once the short-term damage rate for both the coating and substrate can be determined, a long-term averaged damage rate for a specific site can be computed using Equation (6). The joint probability distribution of droplet size and rain intensity

is computed by multiplying the lognormal distribution of rain intensity with the two-parameter Weibull distribution of droplet size distribution (DSD). The parameters of DSD are defined conditional on the rain intensity by parameters

and

.

is the two-parameter Weibull distribution of wind speed, and

is the probability of occurrence of rain at a given intensity for a specific site and is modelled as a step function.

The long-term damage rate also has units of

and when

, the coating or substrate has failed. See refs. [

1,

2,

12,

13] for additional information and insight into the derivation and inputs into Equations (1)–(6).

A model of damage progression, once damage has been initiated, is also needed for a risk-based maintenance strategy. To calculate this, the dimensionless mass loss rate relationship to the dimensionless number of impacts for both the coating and substrate taken from Springer [

28,

29] is used as shown in Equation (7).

The dimensionless mass loss rate is then converted to a short-term mass loss rate with Equation (8). The short-term mass loss rate,

has units of

, and

is the density of the rain droplet.

The long-term mass loss rate is then computed using a similar expression as was used to determine the long-term damage initiation rate in Equation (6) and can be seen in Equation (9).

Finally, the mass loss per unit area for a given time can be calculated with Equation (10), where

has units of

.

A key assumption in this analysis is that the substrate is fatiguing towards initiation while the coating is still covering it. However, the substrate cannot begin to lose mass until the coating in the unit area being analyzed has eroded away completely. For the model to be applicable within a risk-based maintenance strategy, it must be transformed into a stochastic framework. Although the model incorporates probability distributions for weather data, the results are deterministic, as it consolidates the results into an average damage and mass loss rate. To transition to a stochastic approach, the Weibull parameters for droplet size and rain intensity, along with wind speed and the mean and standard deviation for rain intensity, are treated as time-variant stochastic variables characterized by normal distributions. These variables are re-evaluated annually within Monte Carlo simulations, allowing the recalibration of damage initiation and mass loss rates to reflect minor annual variations in weather conditions.

2.1.2. Probabilistic Bayesian Network Model

Evaluating the physics-based erosion model through Monte Carlo simulations is computationally intensive and inefficient for integration within a decision model. To enable efficient decision-making, the erosion process is instead represented using a Bayesian network formulation. However, constructing the conditional probability tables (CPTs) for the Bayesian network still requires numerous runs of the erosion model.

Importantly, the erosion model’s outputs of interest are limited to the statistical description of three key parameters: the annual erosion damage rate , the coating mass loss rate , and the laminate mass loss rate , as all environmental information is condensed into these parameters. These parameters effectively represent the influence of environmental conditions, making them suitable for a simplified probabilistic representation.

Since , , and are not statistically independent, their interdependencies must be captured. From Equation (7), it is evident that depends linearly on , and from Equations (3), (5), and (8) it can be seen that also exhibits a linear relationship with . A similar relationship is expected for the long-term parameters, albeit with added uncertainty.

In this study,

is modelled as a stochastic variable with a probability distribution fitted to values obtained from the erosion model. The parameters

and

are then modelled as stochastic variables conditioned on

.

Figure 3a presents a PDF-scaled histogram of

values generated by the erosion model along with a fitted generalized extreme value distribution.

Figure 3b illustrates the linear relationship between

,

, and

, confirming the expected correlation. Linear regression is used to estimate the coefficients of this relationship, and a three-parameter Weibull distribution is fitted to the residuals. This approach yields a condensed probabilistic representation of the erosion model, enabling efficient integration into the Bayesian decision framework.

The erosion model described above incorporates physical uncertainties; however, model uncertainties must also be considered. To account for these, additional uncertainty factors are introduced into the calculation of the damage rate, which influences both the incubation period and the mass loss rates through the relationships previously described.

Model uncertainty comprises both time-variant and time-invariant components. The time-variant component is primarily associated with uncertainties in the load model—such as the exclusion of hail—which may vary in impact from year to year. In contrast, the time-invariant component is largely related to uncertainties in the resistance model and includes physical uncertainties in the model parameters.

To incorporate these uncertainties, the annual (long-term) damage rate is expressed as the following:

where

is the time-variant load model uncertainty and

is the time-invariant resistance model uncertainty.

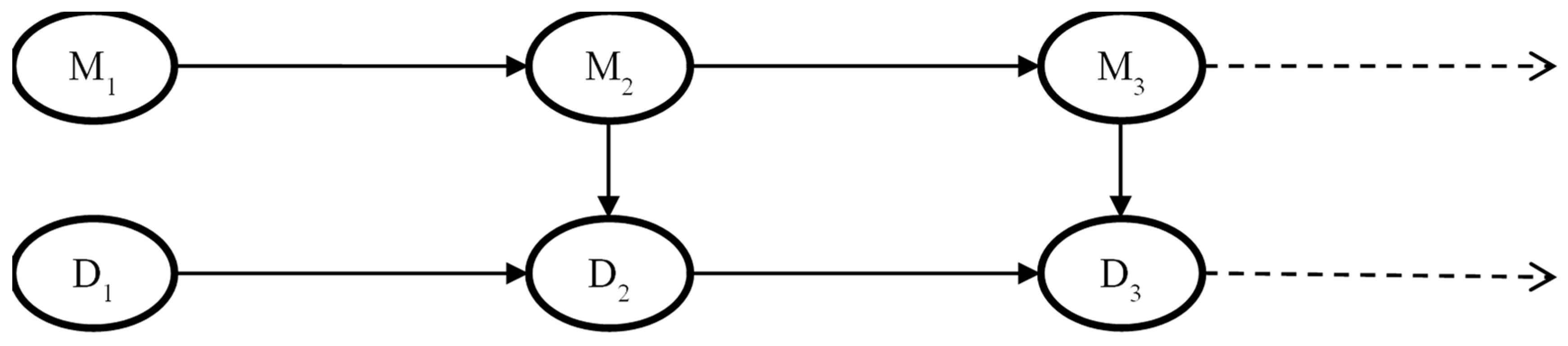

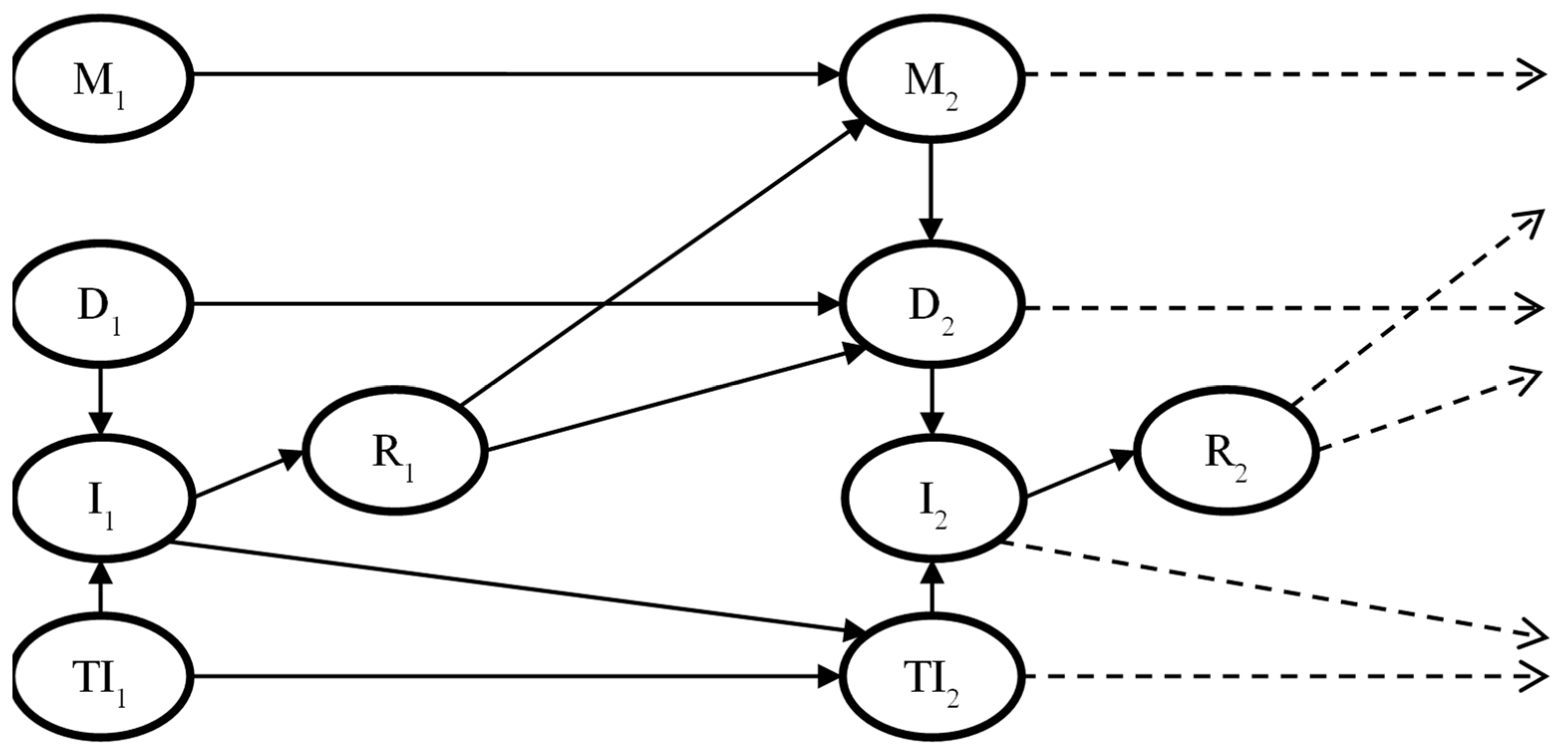

Figure 4 illustrates the structure of a simplified dynamic Bayesian network (DBN) degradation model. Each time slice consists of two nodes: D, representing damage, and M, representing the time-invariant model uncertainty, here corresponding to

.

The erosion model consists of three distinct phases: the incubation period, the coating mass loss phase, and the laminate mass loss phase. Accurate representation of these phases—including correct incubation timing and mass loss behaviour—requires a DBN model with a sufficient number of states to capture the progression within each phase. For instance, modelling the incubation period with a single state would imply a geometric distribution for the transition time, as the probability of moving to the next phase would remain constant at each time step. Instead, a damage number is used to represent the progression of damage during the incubation period. The node is used to model the damage through all phases by defining relative intervals for each phase:

: Incubation phase;

: Coating mass loss phase;

: Laminate mass loss phase.

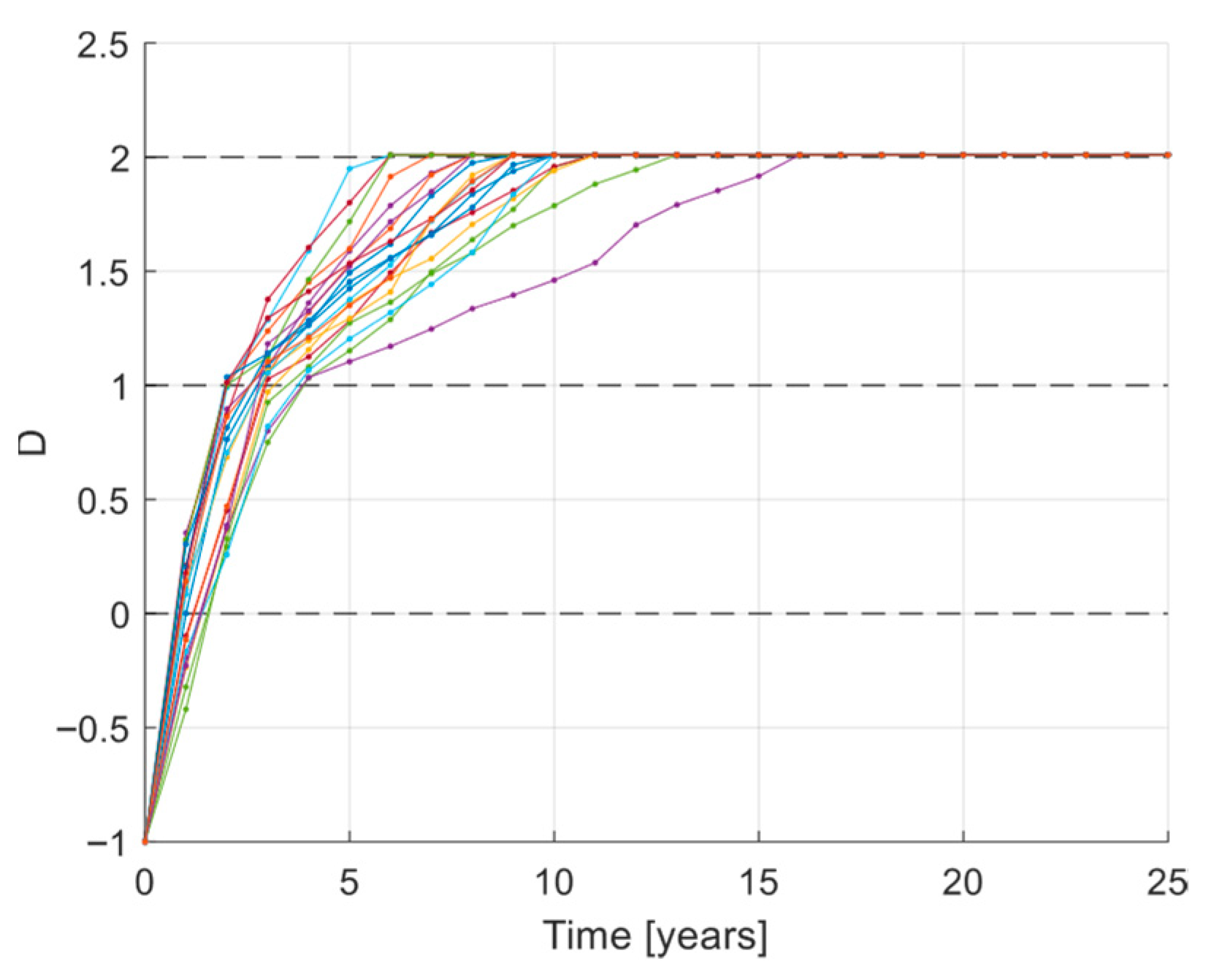

With this definition of

, sampling from the condensed model with included model uncertainties leads to

Figure 5.

The DBN erosion model is defined by the conditional probability table

and by the tables for the initial damage state

and model uncertainty

. The number of states for each node is selected using a convergence analysis, ensuring that the distribution for the predicted time to initiation, time to coating failure, and time to laminate failure correspond to the distributions obtained using Monte Carlo simulations. For the base model presented in

Section 3, it was found sufficient to model

by 151 states and

by 10 states. As the erosion model explicitly models the incubation period, the initial damage state is always the first state, thus

is a vector with one in the first entry, while the rest are zeros.

is calculated directly from the lognormal distribution.

is calculated using the condensed probabilistic model. For each combination of states for

and

,

samples were drawn (by dividing both into 50 subintervals, and drawing 100 samples in each subinterval), and the condensed probabilistic model was used to calculate the damage state the following year

The distribution for

was then established based on which states the samples ended in.

In total, the condensed model was called

times, resulting in a CPT calculation time of 200 s. Using the DBN model, the probabilistic progression of erosion over 20 years was calculated in 0.02 s, and in

Figure 6 the time to initiation, time to coating failure, and time to laminate failure (hole in the blade) is shown. The figure also shows the results obtained using 1000 Monte Carlo simulations using the condensed model, which took 150 times longer. It is seen that the two models yield almost identical results. The physical model would take

times longer than the DBN model for 1000 simulations.