1. Introduction

The transition toward sustainable and decentralized energy systems has become a fundamental tool for addressing climate change, reducing inequalities, and promoting socio-economic development. The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted in 2015, outlines 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as an integrated framework for global prosperity and environmental stewardship. At the heart of this framework is SDG 7, which aims to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. Traditional centralized energy systems have often failed to address disparities in energy access and have been limited in their capacity to integrate renewable energy sources at the community level.

In contrast, energy sharing mechanisms, enabled by advancements in digital infrastructure, smart grids, and distributed energy resources (DERs), represent a transformative shift in how energy is generated, exchanged, and consumed [

1]. These mechanisms include models such as peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading, where prosumers can sell the electricity that they do not use, to other users in a decentralized market; virtual power plants (VPPs); and renewable energy communities, which promote collective ownership and governance of energy assets [

2]. Collectively, such approaches enhance the resilience and flexibility of energy systems, reduce energy poverty, and empower local stakeholders [

3].

Recent studies highlight the fundamental role of community-based energy models in advancing not only SDG 7, but also SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). As an example, energy cooperatives and energy communities led by citizens have been demonstrated to foster social acceptance, democratic governance, and equitable participation in the energy transition [

4]. Beyond the environmental and economic benefits, energy sharing mechanisms are increasingly recognized for their contribution to energy justice and social innovation, enabling marginalized groups to access clean and affordable energy [

5].

Technological innovations such as blockchain-based trading platforms and advanced metering infrastructures further expand the potential of local energy markets, as demonstrated in recent reviews of P2P energy trading architectures, pricing strategies, and enabling technologies [

6,

7]. These cases illustrate how digitalization can enhance transparency, trust, and efficiency in decentralized markets, thereby accelerating their scalability.

However, regulatory and institutional barriers remain a major challenge. Studies reveal that inconsistent transposition of EU directives, administrative complexity, and limited grid access hinder the widespread implementation of renewable energy communities, and that an extensive spread would require a holistic approach [

8]. Moreover, socio-technical barriers, such as a lack of technical skills and limited awareness among citizens, restrict broader participation [

9,

10]. Overcoming these challenges requires coordinated policy support, financial incentives, and capacity-building programs, alongside efforts to integrate energy sharing mechanisms within broader strategies of sustainable urban and rural development.

Against this background, this paper provides a comprehensive review of the role that energy sharing mechanisms can play in supporting the SDGs, with particular attention to SDGs 7, 11, and 13. It explores the current landscape of energy sharing initiatives, their alignment with sustainability objectives, and the enabling conditions necessary for scaling up these models globally.

To ensure analytical transparency and reproducibility, this study adopts a structured review approach. The selection and synthesis of literature and policy documents follow defined criteria concerning data sources, time frame, and thematic relevance.

Building on the literature reviewed, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: How do energy-sharing mechanisms contribute to the advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) outlined in the 2030 Agenda?

RQ2: Which governance frameworks and regulatory instruments most effectively enable renewable-energy communities (RECs) across Italy and Europe?

RQ3: How can territorial governance in fragile and inner areas, such as the Central Apennines, integrate energy-sharing models into broader strategies for resilience and sustainable reconstruction?

These questions fill a gap in the existing literature, where institutional and socio-territorial aspects of RECs are often underexplored compared with their technical or financial dimensions.

Details on the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion parameters, and classification framework are provided in

Section 2.

2. Methodology

This review follows a structured approach designed to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and balance in the selection and synthesis of the analyzed literature. The methodology draws from established review protocols used in environmental and energy studies.

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, all selected sources were then classified according to four analytical dimensions: (i) technical and infrastructural aspects, (ii) regulatory and governance frameworks, (iii) socio-economic mechanisms including justice, equity and territorial cohesion, and (iv) psychological and behavioral drivers of citizen participation. Only sources providing substantial evidence in at least one of these categories were included in the final synthesis.

The time frame used for the literature search was between January 2014 and August 2025 using the databases Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect (Elsevier), and MDPI Open Access, complemented by official institutional repositories such as the European Commission (EU Energy Community Portal), REScoop Europe, Gestore dei Servizi Energetici (GSE), and national regulatory websites.

The main keywords applied, individually and in Boolean combinations, were:

“renewable energy communities”, “energy sharing”, “peer-to-peer trading”, “local energy markets”, “distributed generation”, “energy justice”, “social innovation”, “sustainable development goals”, “Central Apennines”, and “Next Appennino”.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Only peer-reviewed journal articles, official EU or national policy documents, and authoritative statistical datasets were included. Conference proceedings were considered when they presented original models or data not available elsewhere. Grey literature, opinion pieces, and non-verifiable online content were excluded.

Studies were required to address at least one of the following dimensions:

Design and operation of renewable or local energy communities;

Energy sharing mechanisms or peer-to-peer exchange systems;

Regulatory or socio-economic frameworks linked to the 2030 Agenda SDGs.

2.3. Classification and Evidence Synthesis

The analyzed documents (approximately 180 sources from which 69 were selected) were classified by:

Geographical scope (Italy, Europe, or Global);

Analytical dimension (technical, socio-institutional, regulatory, or psychological);

SDG alignment, following the UN’s official indicator set.

Evidence was summarized through qualitative synthesis rather than quantitative meta-analysis, since the reviewed material combines heterogeneous empirical and conceptual sources. Figures and tables were re-designed to convey comparative and thematic relationships, not numerical scoring, avoiding any impression of unverified quantitative weighting.

2.4. Limitations

While the review aims for comprehensive coverage, the literature on emerging mechanisms such as energy communities evolves rapidly. Therefore, the selection reflects the state of knowledge up to mid-2025. Data referenced from GSE and EU repositories correspond to the most recent releases available at the time of writing.

3. Energy Sharing Mechanisms in Italy

The European Union has pledged to become the world’s first climate-neutral continent by 2050. To reach this target, it is steering its policies toward a system increasingly based on renewable resources and distributed generation. Within this framework, the smart grid model has gained importance, as it helps the deployment and management of small-scale renewable energy units rather than relying solely on large, centralized plants. Such a model enables interventions that are closer to end-users, creating greater responsiveness and efficiency in the energy supply chain.

At the same time, demand-side management solutions make it possible for consumers to overcome their traditional passive role and become active players in the energy market. Citizens can in this way engage in the energy transition by adopting practices such as load shifting, peak shaving, and energy storage, that together enhance the reliability and adaptability of renewable energy systems.

This environment has provided fertile ground for the development of Renewable Energy Communities (RECs), which are emerging worldwide at different rates. Similar to Citizen Energy Communities (CECs) defined in Directives 2018/2001 and 2019/944 under the Clean Energy for All Europeans package [

11], in Italy, RECs have gained momentum also thanks to the transposition of EU Directive RED II through Legislative Decree 199/2021 [

12].

Several Italian regions have enacted specific laws to promote the establishment and consolidation of RECs, with measures ranging from legal recognition to direct financial support. For instance, Abruzzo (LR 8/2022) has introduced grants prioritizing disadvantaged areas and established a permanent committee for monitoring, while Basilicata (LR 12/2022) supports municipalities with start-up subsidies and a technical platform. Other regions, such as Emilia-Romagna (LR 5/2022) and Umbria (LR 6/2024), provide substantial non-repayable grants and revolving funds for feasibility studies, infrastructure, and implementation. Lombardy (LR 2/2022) has adopted one of the most comprehensive frameworks, allocating more than €10 million annually between 2023 and 2024, coupled with technical support platforms and cooperative assistance. In contrast, some regions, such as Molise, have yet to adopt dedicated REC legislation and rely mainly on national- or EU-level funding.

A comparative analysis reveals significant variation across Italian regions in terms of financial allocations, governance mechanisms, and supporting measures. While Sicily has earmarked over €61 million under the FESR 2021–2027 program to fund up to 40% of capital costs for REC projects, Valle d’Aosta has opted for more localized subsidies, covering up to 100% of project costs for public RECs with a maximum of €50,000 per project. Other regions, like Liguria and Veneto, provide mainly legal and organizational support rather than direct subsidies, emphasizing regulatory coordination, observatories, and best practice sharing. These diverse approaches demonstrate the fragmented but dynamic governance of energy communities in Italy, reflecting both regional priorities and socioeconomic contexts.

In Italy, alongside regulatory and financial frameworks, the number of operational Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) is steadily increasing. According to the Gestore dei Servizi Energetici (GSE) public dataset (March 2025), 212 RECs are currently active, corresponding to an installed capacity of approximately 18 MW and involving around 1956 users. However, the number of initiatives at various stages of planning or development is significantly higher, with nearly 600 additional projects identified as under construction or awaiting connection (according to GSE definitions, “active” RECs are those already authorized and connected to the distribution grid, while “under construction” includes projects that have completed the qualification phase but are pending grid connection or operational testing; the data are aggregated nationally and refer to configurations within the low- and medium-voltage distribution networks). These figures derive from the GSE statistical dashboard [

13] and reflect data collected at the distribution transformer level, as defined in GSE’s national monitoring framework. These communities display a heterogeneous composition, ranging from small rural initiatives such as the CER in Gagliano Aterno (Abruzzo) with fewer than 250 inhabitants, to larger urban projects like the “CER Solidale Napoli Est” (Campania) involving about 25,000 residents. The scope of renewable sources also differs, there are many RECs based predominantly on photovoltaic generation and others integrate wind, biomass, hydropower, or energy storage systems, as seen in projects in Calabria and Puglia. Moreover, building types and user profiles are also different, including residential, educational, commercial, and public administration facilities, often with a focus on social inclusion and the involvement of vulnerable groups.

The combination of regional legislation, financial support, and collective initiatives outlines the effective use of energy sharing mechanisms as a tool to promote social cohesion, reduce energy poverty, and accelerate the achievement of climate and energy targets. At the same time, the uneven distribution of resources and capacities across regions suggests the need for greater policy harmonization and coordinated support to fully exploit the transformative potential of energy communities.

Beyond the regulatory framework, many authors have investigated Italian RECs both from technical and socio-institutional perspectives. Grignani et al. (2021) emphasize the suitability of cooperative models for REC governance, demonstrating how community cooperatives enhance social trust, democratic participation, and the acceptance of distributed renewable generation in Italy [

14]. A study promoted by the European Union provide an EU-wide perspective but highlight Italy as one of the frontrunners in integrating social innovation into energy sharing initiatives [

15].

Politecnico di Milano’s Energy and Strategy group (2022–2023) mapped 14 regional incentive schemes for RECs, including Lombardy, Sardinia, Campania, and Sicily, highlighting that most schemes are publicly directed at municipalities and local authorities, and provide both technical and financial support. At the national level, the 2023 ministerial decree signaled a €5.7 billion dedicated budget to REC incentive programs, effective January 2024, marking a turning point in enabling bottom-up and top-down REC deployment nationally [

16].

Case-study approaches have offered detailed insights into local REC dynamics. For example, Di Fazio et al. (2022) developed the ComER project, which introduced decision-support tools for REC operations under Italian regulations, including optimization of storage management, tariff allocation, and member coordination [

17]. Moretti et al. (2023) demonstrated that renewable energy communities, when supported and guided by public administrations, can overcome many implementation barriers in Italy [

18]. From a technical perspective, recent contributions have examined the impact of RECs on distribution grids. Dimovsky et al. (2023) analyzed two real-life networks, an urban and a rural distribution grid, with the aim of evaluating the impact of ECs on the electric system [

19]. Similarly, Conte et al. (2023) proposed an optimal coordination strategy for household-level RECs, showing that demand-side flexibility and smart scheduling can maximize shared consumption and minimize community-level costs under Italy’s incentive scheme [

20]. Carraro et al. (2023) analyzed the potential economic and environmental gains of Energy Communities by integrating demand response strategies and combining diverse user profiles [

21]. Tortorelli et al. (2024) developed a multi-agent control framework using reinforcement learning to manage distributed renewable and storage systems within Energy Communities, including shared storage assets [

22]. Gianaroli et al. (2024) simulated a virtual Renewable Energy Community compliant with Italian energy-sharing regulations, introducing dynamic allocation algorithms that distribute shared energy on an hourly basis, even under unbalanced conditions between generation and consumption [

23].

On the socio-economic dimension, Wirth (2014) analyzed barriers and drivers for REC development in Italy, identifying the centrality of trust, fairness in benefit distribution, and the role of municipalities as key promoters [

24]. Other authors have studied the regional policy landscape: Candelise et al. (2023) reviewed the heterogeneity of REC initiatives across Italian regions, showing how decentralized governance and local incentives have accelerated diffusion in Lombardy, Sardinia, and Sicily, while also highlighting disparities in institutional capacity [

25]. Zhu et al. (2025) proposed a structured three-step framework to examine the development of Renewable Energy Communities [

26]. Sciullo et al. (2023) examined the key drivers and barriers influencing the diffusion of Energy Communities, analyzing three main aspects: the structure of the energy market, the institutional and policy framework, and societal attitudes toward environmental cooperation [

27].

Large-scale participatory renewable projects are also important in the Italian landscape, offering hybrid models of community involvement. As example, projects like Enel’s Trino solar farm in Piedmont, partially financed through citizen crowdfunding, represent a complementary pathway where community participation extends beyond small-scale RECs into utility-scale renewables [

28]. In parallel, insular contexts such as Procida and other minor Mediterranean islands are being studied as laboratories for REC implementation, integrating photovoltaics and storage under microgrid schemes to enhance resilience and reduce dependence on imported fossil fuels [

29]. Battaglia et al. showed that Italy’s geothermal capacity offers a renewable resource that can be leveraged in REC contexts, especially for local heating through district heating networks and microgrid designs in rural or small-town clusters [

30]. Research on socioecological marginality within the Apulo Campano Apennines highlights how wind energy investments, when integrated through RECs or cooperative frameworks, can valorize peripheral territories by addressing inequality and spurring local benefits [

31].

In general, the Italian panorama shows a heterogeneous but growing portfolio of REC implementations, ranging from solidarity-based initiatives in disadvantaged urban neighborhoods to inter-municipal projects in rural and mountain areas, and from condominium-scale collective self-consumption to island microgrids. The increasing number of papers on the subject underlines that Italy has become a key testing ground where regulatory innovation, technical optimization, and community governance interact to accelerate the transition toward distributed, renewable-based energy systems. Importantly, these initiatives also resonate with the Sustainable Development Goals: REC projects in earthquake-affected areas or fragile rural territories contribute to SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by ensuring local access to reliable, renewable energy while supporting resilience and reconstruction. Solidarity-based RECs, such as those targeting energy poverty in urban districts, directly advance SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by redistributing energy benefits and fostering social inclusion. Furthermore, the coupling of RECs with storage, digital platforms, and smart grids aligns with SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), underscoring the dual role of Italian RECs as both technological laboratories and social innovations for sustainable development.

Compared with leading European frontrunners such as Austria and Germany, where national coordination frameworks and long-standing cooperative traditions ensure regulatory uniformity, the Italian model shows both pioneering potential and structural fragmentation. Its strengths lie in its capacity to activate RECs in post-disaster and inner-area contexts, where energy transition is linked to resilience and demographic regeneration. However, regional asymmetries and administrative complexity reduce its immediate scalability and suggest that replicability outside Italy may require adaptation to national governance capacity and territorial cohesion policies.

Renewable Energy Communities in the Central Apennines: The Next Apennines Laboratory

The Central Apennines region, severely affected by the 2016–2017 seismic sequence, presents a unique context for energy sharing mechanisms, particularly Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) acting as tools for resilient reconstruction and community empowerment. The Next Appennino program, a regional initiative launched after the 2016 earthquakes, explicitly aims at integrating socio-economic recovery, territorial redevelopment and sustainable energy deployment in the seismic “crater” areas supporting REC development alongside reconstruction efforts [

32]. The number of involved administrations has reached 84. The financial allocation has been significant: €47.3 million was assigned to Abruzzo, €51.5 million to Marche, €8 million to Lazio, and €33 million to Umbria. These investments primarily target interventions such as energy efficiency retrofitting of buildings, renewable energy production, centralized smart energy systems, and community-based energy sharing models. The overarching policy goal of these measures is twofold: to counter demographic decline and to stimulate new socio-economic opportunities across the Apennine regions [

33].

The case of Abruzzo is particularly emblematic. Pre-existing social and institutional conditions had already created fertile ground for energy community initiatives, largely due to the regional law of 2015 on community cooperatives (RL 2, 8 October 2015), which drew upon long-standing traditions of local cooperation and territorial resource management. This framework contributed to strengthening local social capital and laid the groundwork for REC diffusion. Building on this foundation, the introduction of the Complementary Fund enabled the allocation of over €47 million to the region. Following the approval of a specific regional law on RECs in 2022, this financial support helped the establishment of 18 communities, expected to install an aggregate capacity of 19,582 kWp. These initiatives are led predominantly by municipalities or other public entities and involve 2646 private participants. Photovoltaic (PV) technology is the dominant source, although one project incorporates a wind turbine in the municipality of Popoli. In the Marche region, REC legislation was introduced in 2021 In the Marche region, regional law (B.U. 17 June 2021) established the framework for Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) and as of the latest mapping in 2024, 3 CERs have been financed, involving 1044 private participants and achieving an installed capacity of approximately 11,517 kW across photovoltaic and hydroelectric solutions, for a total investment of about €51.5 million. The Lazio region passed its REC law in 2020 and subsequently launched a call in 2022 for feasibility studies with a dedicated budget of €1 million. With the aid of €8 million in complementary funding, three RECs were established. These projects collectively involve 309 private participants and an installed capacity of 1531 kW derived from both PV and hydroelectric plants [

34].

Umbria, which only approved its REC legislation in 2024, has also mobilized substantial resources. A €33 million allocation has supported the creation of the Bacino Imbrifero Umbro REC, engaging 940 private participants and achieving a combined capacity of 8549 kW through a diversified energy mix that includes PV, hydroelectric, and biomass integrated into district heating. Furthermore, the Chamber of Commerce of Umbria has promoted REC participation among companies by financing technical and economic feasibility studies with an additional €400,000 [

35]. With the most recent ordinance signed on 2 July 2025, the number of financed projects in this regions has risen to 40, with a total value of approximately €126 million, supported by €59 million in public contributions already granted. The newly financed entities are: in Marche, the municipalities of Tolentino (€3.4 million), Servigliano (€716,000), Fabriano (€1.1 million), Montegiorgio (€2.2 million), Pieve Torina (€254,000), and Montalto delle Marche (€880,000); in Umbria, Spoleto (€463,000); in Lazio, Leonessa (€658,000), Cittaducale (€316,000), Borgo Velino (€685,000), and Rieti (€1.2 million); in Abruzzo, Arsita (€328,000), Collarmele (€277,000), Popoli (€2.5 million), Montebello di Bertona (€462,000), Rocca Santa Maria (€190,000), and Isola del Gran Sasso d’Italia (€371,000) [

36].

Case studies from the Marche and Lazio regions demonstrate how solar PV with storage and integrated seismic-energy retrofits contribute to sustainable development goals, notably SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Studies further show how energy-sharing helps counter rural depopulation and promotes economic revitalization in quake-affected municipalities.

The technical aspects related to the implementation of RECs in the central Apennines area have been addressed by several scholars. Brunelli and colleagues (2025) introduced a novel simulation framework aimed at supporting the design of hybrid Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) that integrate multiple renewable energy sources, thereby filling a notable gap in existing planning tools. The model was applied to a case study in a forested area of the Central Apennines (Italy), where the sustainable exploitation of locally available resources points to a combination of biomass and photovoltaic plants as suitable energy solutions. Beyond the technical dimension, the REC concept is also framed as an instrument to mitigate rural depopulation by generating new services and opportunities consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals. Scenario analyses, which tested different community compositions and plant capacities, indicate that the configuration including a 600 kW biomass facility achieves the most substantial outcomes, with estimated CO

2 emission reductions of up to 1660 tonnes per year and levels of energy self-sufficiency exceeding 80% across all modeled cases [

37].

Di Paolo et al. (2023) proposed a set of design criteria for establishing Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) in a small-to-medium-sized Italian city located in the Apennine hinterland [

38].

Marchetti, Vitali, and Biancini (2024) analyzed the first REC pilot projects in the Marche region, demonstrating how energy sharing in earthquake-affected areas (Castelraimondo and the Unione Montana dei Monti Azzurri) can simultaneously address depopulation, employment shortages, and high energy costs while generating approximately 6.1 GWh/year of renewable energy [

39].

As a final review of the central Appenines experience, the independent ReSTART sustainability assessment applied within the CITI4GREEN framework, assessed over one thousand public interventions across Abruzzo, Lazio, Marche, and Umbria to evaluate their alignment with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda. The assessment found that, while all three pillars of sustainability were represented, the energy and economic dimensions were under-represented. In particular, SDG 7, “Affordable and Clean Energy”, ranked second-lowest among all Goals impacted by the 1278 reconstruction interventions, whereas SDG 4 and SDG 11 were most prominent. The authors concluded that additional policies would be needed for a more integrated sustainable development path. In the subsequent cycle, the Next Appennino programme (2023–2025) introduced specific funding lines for RECs and energy efficiency in public/social infrastructure. The 2 July 2025 ordinance increased the number of financed REC-related projects to 40, for a total value of about 126 million € with around 59 million € in public contributions already granted. These measures align policy intent with SDG 7 by explicitly supporting shared energy in the inner seismic areas; however, official indicators (e.g., MW installed, REC users, shared energy) that assess the exact situation before and after have not yet been published and the scale of improvement relative to the 2022 baseline remains to be measured. Therefore, the integration of energy-transition objectives into the reconstruction policy can be considered an evolving process, partially addressing the deficiencies identified in the ReSTART assessment but still awaiting measurable confirmation [

40].

Energy communities represent a strategic response to both depopulation and energy poverty in marginal areas of the Apennines. By enabling citizens, local authorities, and small businesses to collectively generate and manage renewable energy, primarily solar photovoltaics, small hydro, and biomass, they enhance resilience and reduce dependency on external energy supply. These forms of cooperation are crucial not only for decarbonization (SDG 13) but also for fostering inclusive governance models that strengthen local cohesion (SDG 16) and new economic opportunities consistent with sustainable growth (SDG 8).

The assessment conducted within the ReSTART project demonstrates that although reconstruction policies promoted environmental protection and social services, the energy dimension remains underrepresented. Incorporating energy sharing schemes into reconstruction frameworks could ensure that future investments not only rebuild infrastructure but also empower communities through decentralized energy systems. This would align regional resilience strategies with European Union directives on renewable energy communities and amplify their contribution to the SDGs. Ultimately, advancing RECs in the Central Apennines could transform post-disaster recovery into a long-term driver of climate action, territorial cohesion, and sustainable development.

Table 1 reports the regulatory, technical, and socio-economic dimensions of Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) in Italy and their contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The table highlights how EU and national policies, regional legislative frameworks, operational projects, governance models, and technical innovations collectively shape the Italian REC landscape, demonstrating their potential to advance SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

4. Renewable Energy Communities in Europe

The European Union’s energy transition considers Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) and energy sharing mechanisms as key instruments to promote decentralization, social inclusion, and decarbonization. They represent a shift from centralized systems dominated by large utilities to distributed, citizen-driven energy models aligned with the European Green Deal and the Clean Energy for All Europeans package. The Renewable Energy Directive (RED II, 2018/2001/EU) and the Internal Electricity Market Directive (IEMD, 2019/944/EU) formally recognized RECs and Citizen Energy Communities (CECs) as legal entities enabling citizens, local authorities, and small enterprises to jointly produce, share, and manage renewable energy within open and voluntary frameworks [

41]. These directives aim to democratize access to clean energy while enhancing public participation and acceptance of renewables. The subsequent REPowerEU plan and RED III (Directive 2023/2413/EU) have strengthened these commitments, increasing the EU’s renewable target to 42.5% by 2030 and urging Member States to embed community participation in their national energy strategies [

42].

Historically, the development of community-based energy systems in Europe can be traced to early cooperative movements in Germany, Denmark, and Italy, where local associations sought to electrify rural areas in the early 20th century [

43]. However, the formal institutionalization of RECs only began with the Clean Energy Package (2019), which defined their legal, governance, and operational framework. Current estimates indicate the presence of 3500–4000 active energy communities across Europe, involving nearly one million citizens [

44]. These communities take diverse forms, from rural cooperatives to urban multi-apartment systems and inter-municipal consortia, but share common objectives of enhancing energy independence, social equity, and environmental sustainability [

15].

National transpositions of RED II have produced a heterogeneous policy landscape. Germany, with its long cooperative tradition, remains a leader through projects such as Feldheim Energy Village, which achieved complete energy self-sufficiency via local wind, biomass, and solar systems [

45]. Austria’s Erneuerbaren-Ausbau-Gesetz (EAG 2021) provided a clear legal structure for RECs and CECs, coupled with a national coordination office to facilitate community participation and data transparency [

46]. In Italy, the national regulatory framework under the Decreto MASE n. 414/2023 (in force 24 January 2024) establishes incentives on the energy shared within a renewable energy community (CEC or CACER) that varies depending on plant size and market price of electricity [

47]. In the Netherlands, the Subsidieregeling Coöperatieve Energieopwekking (SCE) grants cooperative subsidies per kilowatt-hour of renewable energy produced [

48]. Meanwhile, Spain and Portugal revised their restrictive frameworks in 2019 to allow collective self-consumption and energy sharing at the neighborhood scale, while Belgium and France have prioritized regulatory simplification and municipal partnerships [

49]. Ireland’s Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (RESS) and Austria’s Coordination Office for Energy Communities exemplify enabling instruments combining financial and administrative assistance [

50].

Technological innovation and market mechanisms underpin the functioning of RECs. Across Europe, peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading and local energy markets have emerged as viable energy sharing mechanisms. The Quartierstrom project in Switzerland pioneered blockchain-based trading among 37 households, showing that dynamic pricing can double local self-consumption rates compared to standard net-metering arrangements [

51]. Similar experiments have been carried out in Denmark, where the Lolland Hydrogen Community integrates wind generation with hydrogen storage for community use, and in Austria’s Erzeugungsgemeinschaften (GEA), which coordinate neighborhood-scale generation and consumption [

52].

Policy design decisively shapes the evolution of these technical and social systems. The REScoop Transposition Tracker reveals that Austria, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands score highest for both regulatory clarity and enabling frameworks, providing incentives, financing tools, and administrative support. Conversely, several Eastern and Southern European countries exhibit delays in transposition or incomplete enabling frameworks, constraining REC development [

53]. Governance models also differ: cooperative and citizen-led structures prevail in Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands, whereas municipal or public-utility-driven RECs dominate in Italy and Spain. National policies influence whether communities adopt profit-sharing or solidarity-based models, affecting citizen engagement and social legitimacy. Studies confirm that legal certainty and transparent governance increase participation and long-term viability [

54].

Figure 1 qualitatively illustrates that countries with more advanced and transparent regulatory frameworks (e.g., Austria, Germany, Italy) generally show higher REC diffusion and technological diversity. Values are based on comparative evidence from the REScoop Transposition Tracker and national legislation analyses rather than quantitative scoring. The figure highlights how higher policy readiness (e.g., in Austria, Germany, and Italy) correlates with greater REC proliferation and technological diversification.

Economic incentives and benefit redistribution models are equally policy-dependent. In Italy, energy sharing follows a virtual model, where the amount of shared electricity within a community is determined each hour as the lowest value between total energy fed into the grid and total energy consumed by community members [

55]. Using cooperative game theory, researchers have proposed fair allocation methods (e.g., Shapley values) to distribute revenues among members according to their contribution to shared consumption [

56]. Such schemes encourage behavioral adaptation, promoting self-consumption and equitable benefit sharing. Comparative analyses indicate that harmonized definitions of “shared energy” and standardized financial instruments across Member States would enhance cross-border learning and scalability [

57].

Several recent studies have employed empirical approaches to investigate the tangible outcomes of Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Krug et al. [

58] conducted a comparative policy analysis of the transposition of the recast Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) in Germany and Italy, focusing on the enabling frameworks for RECs and their alignment with national implementation contexts. Their work combined context analysis, multi-level governance (MLG) assessment, and extensive document review, providing insight into how policy coherence and stakeholder coordination shape REC development across Member States.

Guetlein et al. [

59] adopted a quantitative, survey-based design to empirically examine factors influencing citizen investments in RECs in France. Using discrete-choice and contingent-valuation experiments with over a thousand participants, they identified ownership, governance, and return-on-investment features that either encourage or hinder community participation—thus offering evidence on how social and financial incentives affect REC scalability.

Complementing these macro- and behavioural analyses, Blečić et al. [

60] presented an integrated case study of the first REC established in Cagliari (Italy), where a participatory design methodology was used to engage residents in a social-housing neighbourhood. Their multidisciplinary approach empirically evaluated design and implementation phases, highlighting the role of community-led energy initiatives in addressing energy poverty and promoting local sustainability.

In a broader empirical context, Kilinc-Ata et al. [

61] examined the time-quantile effects of technological innovation, foreign direct investment, economic growth, renewable-energy consumption, and financial development on CO

2 emissions in newly industrialised economies. Their findings demonstrate the crucial moderating role of renewable-energy use and innovation in reducing emissions, providing complementary quantitative evidence on how technological and financial dynamics influence the environmental dimension of the SDGs.

Collectively, these studies demonstrate how diverse empirical methodologies, ranging from policy analysis and surveys to participatory case studies, can capture the multidimensional contribution of RECs to SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and to broader sustainability objectives.

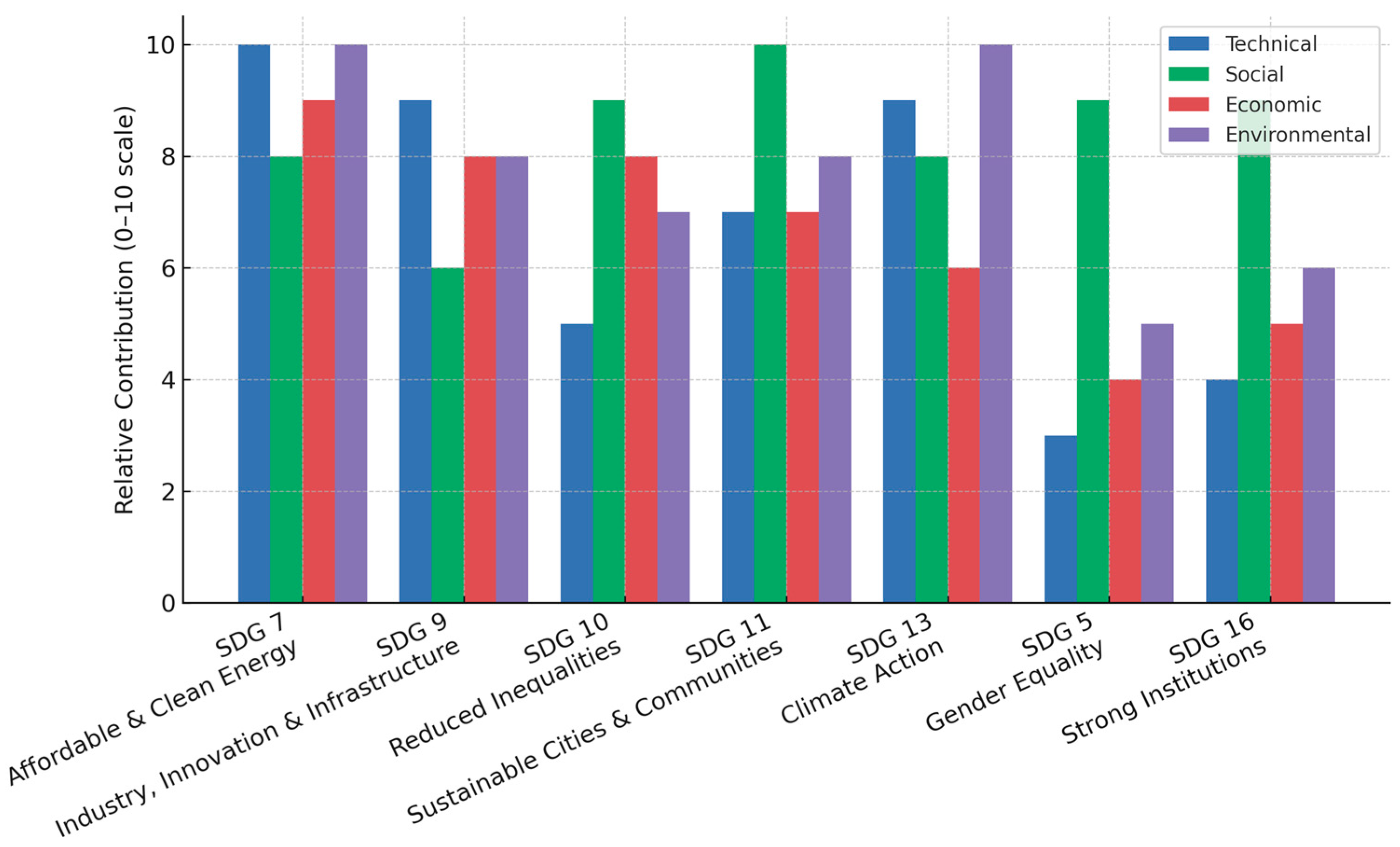

Figure 2 summarizes the main contribution areas, technical, social, economic, and environmental, and their alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 7—Affordable and Clean Energy; SDG 9—Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure; SDG 10—Reduced Inequalities; SDG 11—Sustainable Cities and Communities; SDG 13—Climate Action), derived from literature synthesis. The visual uses qualitative relationships, not numeric weights, to represent the strength of each linkage to specific SDGs.

Table 2 shows representative examples of Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) across Europe, showing their technological diversity and governance models. References correspond to the main scientific or institutional sources detailing each case [

62].

In conclusion, European experience highlights that the influence of policy on REC development is multidimensional, affecting governance, technology, and economics. Where enabling frameworks, such as Austria’s fee reductions, Italy’s premium tariff, or the Netherlands’ cooperative subsidies, combine with social innovation and technological readiness, RECs thrive as pillars of the distributed energy transition. Conversely, incomplete transpositions, lack of financing, and regulatory fragmentation impede progress. Coherent multi-level governance, coupled with harmonized EU standards, will be crucial for ensuring that RECs contribute effectively to Europe’s decarbonization goals, social inclusion, and long-term energy resilience [

63].

5. Human and Psychological Aspects of Renewable Energy Communities Development and Proliferation

The diffusion of renewable energy communities (RECs) across Europe has been shaped not only by technological and institutional innovations but also by the complex set of humans, social, and psychological factors that make citizens willing to engage in collective energy action. At their core, RECs represent a social innovation in the energy sector, transforming citizens from passive consumers into “energy citizens” or prosumers who jointly manage, produce, and consume renewable energy. This transition involves profound psychological and cultural changes, as it requires individuals to adopt new perceptions of energy ownership, cooperation, and environmental responsibility. From a psychosocial perspective, De Simone et al. (2025) [

64] conceptualize RECs as multilevel phenomena shaped by individual, community, and macro-systemic factors. Individual-level drivers include pro-environmental attitudes, altruism, and readiness to modify consumption behaviors, while community-level enablers encompass social capital, local trust, and shared identity. The motivation that pushes citizens to cooperate in collective energy management often comes from a desire for autonomy from centralized energy suppliers and from the perception that local energy production enhances fairness and self-determination. These elements pair with broader theories of social participation, where collective efficacy and perceived competence strengthen engagement in cooperative action. Conversely, low trust in institutions, limited social cohesion, and lack of experience in collaborative projects can hinder participation and lead to community disengagement. Psychological barriers also arise from inequality in participation, gender biases, perceived exclusion from decision-making, or low technical literacy, which may reproduce traditional power imbalances within communities.

The emotional dimension of participation is also relevant. Environmental concern, attachment to place, and moral responsibility act as catalysts for engagement, but emotional attachment can also generate resistance when local landscapes are perceived to be threatened by renewable infrastructures. This ambivalence illustrates that place attachment functions as both a driver and a barrier, depending on its affective orientation. Similarly, the emotional rewards associated with collective success, such as pride, trust, and solidarity, reinforce the social identity of community members, sustaining participation beyond financial payback. These findings emphasize that REC proliferation depends on cultivating a psychological climate of mutual trust, recognition, and fairness, elements that foster long-term commitment and resilience [

65].

Empirical evidence indicates that motivations to join a REC are rarely driven by economic incentives alone; rather, they emerge from a multidimensional interaction of environmental values, social trust, and a sense of belonging to a community [

64]. Such psychosocial dynamics influence not only the decision to participate but also the long-term success and resilience of RECs.

At a broader level, human capital plays a decisive role in enabling these psychosocial mechanisms. As demonstrated by Rădulescu et al. (2025), human capital development, through education, technical competence, and social awareness, acts as a catalyst for sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11) [

66]. Societies with higher human capital indices exhibit stronger environmental engagement and institutional trust, both of which are crucial for collective energy initiatives. However, the relationship is non-linear: in contexts where education and wealth are high, motivation may shift toward individualistic rather than communal goals, potentially weakening participation. This suggests that human capital must be coupled with participatory education and inclusive governance to translate technical skills into cooperative behavior. The intersection of human and psychological dimensions thus reveals that REC success is contingent upon aligning cognitive competencies with affective and social capacities for collaboration.

The psychosocial structure of RECs also contributes to the achievement of multiple Sustainable Development Goals beyond SDG 7 and 11, notably SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Women’s leadership and inclusive participation have been found to enhance procedural justice and energy democracy within communities [

67]. Furthermore, RECs generate social learning processes that reinforce environmental citizenship and local empowerment, creating positive feedback loops between individual awareness and collective sustainability outcomes. These mechanisms illustrate the reciprocal nature of human factors in RECs: while social capital and trust enable participation, participation itself enhances social cohesion and psychological well-being, fostering a virtuous circle of empowerment and sustainability.

Finally, the human and psychological dimensions underline that REC proliferation cannot rely solely on economic or technical optimization. Policies promoting RECs must incorporate behavioral insights and participatory governance frameworks that nurture citizens’ sense of agency and belonging. Training programs, inclusive decision-making, transparent communication, and recognition of emotional and cultural values are essential to building trust and commitment. In this sense, RECs are not merely energy infrastructures but socio-psychological systems in which cooperation, identity, and learning constitute the real engines of the energy transition. Their expansion across Europe, particularly in rural and inner-mountain areas such as the Central Apennines, offers an opportunity to reconnect energy transition with community regeneration and human development, transforming energy sharing into a pathway toward collective resilience and sustainable well-being.

Figure 3 shows the main psychological and social enablers and barriers influencing the development and proliferation of Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) in Europe. Positive drivers (e.g., trust, education, identity, fair governance) and critical obstacles (e.g., administrative complexity, low technical literacy, inequality) are presented qualitatively to reflect insights from empirical studies rather than quantitative scoring.

These findings underline that psychological drivers such as trust, place attachment, and perceived fairness are not merely conceptual descriptors but have direct implications for Renewable Energy Community (REC) policy design. Specifically, they inform the need for (i) participatory governance structures where citizens are involved in decision-making from the early design phase; (ii) transparent and equitable benefit-sharing models that visibly prevent asymmetries among members; (iii) tailored communication and engagement strategies that emphasize collective identity and long-term territorial value rather than purely financial incentives; and (iv) capacity-building and technical facilitation programs to support less experienced or vulnerable groups. These behavioral insights are therefore essential to reducing participation barriers and ensuring long-term stability and legitimacy of RECs, especially in rural, post-disaster, or socio-economically fragile territories.

A significant example of the intersection between social resilience, human psychology, and energy transition is offered by the post-2016 earthquake reconstruction in the Central Apennines. As Castelli (2024) [

68], highlights, the NextAppennino program was conceived not merely as an infrastructure initiative but as a cultural and social project aimed at revitalizing communities and restoring the human–nature balance that has long defined these territories. The promotion of Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) within this framework represents a profound innovation: by enabling citizens to collectively produce and share clean energy, RECs encourage a renewed sense of belonging, cooperation, and shared responsibility toward the land.

This approach also addresses the psychological and demographic challenges of inner areas affected by depopulation and environmental neglect. In regions where human presence is rapidly declining, the act of rebuilding through energy communities helps re-anchor individuals to place and identity, transforming energy transition into a process of territorial care. The need for active stewardship arises not only from economic necessity but from the ecological fragility of landscapes undergoing rapid transformation, where land abandonment and unmanaged reforestation have amplified climate-related risks.

In this perspective, energy communities serve as catalysts for both environmental adaptation and social cohesion. They offer a participatory model in which technical innovation merges with collective memory and emotional attachment to place, strengthening the community’s psychological resilience. Preventing land abandonment thus becomes more than a policy objective, it becomes an ethical and existential commitment to preserve the living relationship between people and their environment. As Castelli (2024) reminds us, the landscapes of the Apennines are “artificialized natures”, shaped through centuries of human interaction; sustaining them through cooperative energy initiatives is not only an act of environmental responsibility but also a reaffirmation of cultural continuity and shared identity [

68].

Figure 4 shows a conceptual map illustrating the interconnections between energy sharing mechanisms, such as Renewable Energy Communities (RECs), peer-to-peer trading, and local energy markets, and their contribution to key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), reduced inequalities (SDG 10), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), and climate action (SDG 13).

The illustration conveys conceptual relationships synthesized from reviewed literature; no numerical weights or indices are applied.

6. Conclusions

The global shift toward decentralized and participatory energy systems marks a critical juncture in the transition toward sustainable development. This review demonstrates that energy sharing mechanisms, such as Renewable Energy Communities (RECs), peer-to-peer trading, virtual power plants, and local energy markets, represent transformative instruments capable of accelerating progress toward multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Beyond their environmental contributions, these mechanisms advance social inclusion (SDG 10), innovation and infrastructure development (SDG 9), and poverty alleviation (SDG 1) through cooperative governance and equitable benefit redistribution. In particular, renewable Energy Communities (RECs) emerge as the most multi-dimensional mechanism, advancing SDG 7 (clean energy access), SDG 11 (resilient communities), and SDG 13 (climate action), while also supporting SDG 1 and 10 through energy poverty alleviation and social inclusion. Peer-to-peer (P2P) trading primarily contributes to SDG 7 and SDG 9 by enabling market-based decentralization and innovation. Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) enhance grid flexibility and system resilience, contributing to SDG 9 and SDG 13. Local Energy Markets (LEMs) act as an integration platform, linking technical optimization with user participation, bridging SDGs 7, 9, and 11.

At the European level, the evolution of RECs reveals a diverse but converging landscape shaped by the transposition of the Clean Energy Package and the subsequent RED III Directive. Countries such as Austria, Germany, and Italy exhibit mature regulatory and financial frameworks that have enabled thousands of communities to actively participate in the energy market. Conversely, several Member States still face structural and administrative barriers that limit access and scalability. These asymmetries underline the importance of harmonized definitions, standardized incentives, and multi-level localization to enhance resilience, community participation, and territorial cohesion. Regional legislation, targeted funding, and grassroots initiatives have created a fertile environment for REC proliferation, while case studies in the Central Apennines demonstrate that energy sharing can serve as a driver for post-disaster reconstruction and demographic revitalization. Integrating RECs into broader recovery and territorial planning strategies can transform reconstruction efforts into long-term engines of sustainability, aligning with EU decarbonization goals and the Next Appennino program’s integrated vision of energy, environment, and society. Technological progress, ranging from blockchain-enabled energy trading to AI-based management systems, has proven essential for the efficient operation of RECs, optimizing self-consumption, energy storage, and grid stability. Yet, technology alone cannot secure their success. The human and psychological dimensions play a decisive role in shaping participation, trust, and social legitimacy. Evidence across Europe shows that environmental values, place attachment, and perceptions of fairness drive citizens’ willingness to cooperate, while social inequalities, limited technical literacy, and administrative complexity act as barriers. Hence, RECs must be understood as socio-technical systems, where collective identity, transparency, and education are as vital as technical optimization.

Looking forward, energy sharing mechanisms can act as laboratories for systemic innovation, linking climate action with inclusive growth but to strengthen their contribution mechanisms to the Sustainable Development Goals requires coherent, multi-level policy action. At the national and regional levels, Italy should prioritise (i) the integration of Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) into municipal and regional resilience strategies, especially in vulnerable or peripheral regions and post-seismic areas such as the Central Apennines; (ii) the simplification of permitting, grid-connection, and metering procedures; (iii) the introduction of long-term fiscal incentives and technical assistance schemes for small municipalities and public bodies; (iv) the promotion of participatory governance and gender-inclusive leadership to enhance procedural justice; (v) the integration between energy, digitalization, and social policy to ensure that community energy remains a tool for empowerment rather than exclusion; and (vi) the encouragement of cross-border cooperation and knowledge exchange within the EU to accelerate learning and harmonization.

At the European level, greater policy coherence is needed to accelerate the scaling of RECs. This involves (a) harmonising definitions, reporting standards, and eligibility criteria under the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II and its recast); (b) strengthening cross-border learning and access to financing through instruments such as the Energy Communities Repository and the REScoop EU network; and (c) incorporating REC-specific indicators into the EU monitoring frameworks for SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

Ultimately, the proliferation of RECs and other energy sharing schemes represents a paradigmatic shift from centralized supply to distributed responsibility, embodying the principles of democratization, resilience, and sustainability. By coupling technological innovation with social participation, these mechanisms can turn the energy transition into a broader human transition; one that reconciles environmental goals with social justice and collective well-being, fully aligned with the ambitions of the 2030 Agenda.