Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insights for Future Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

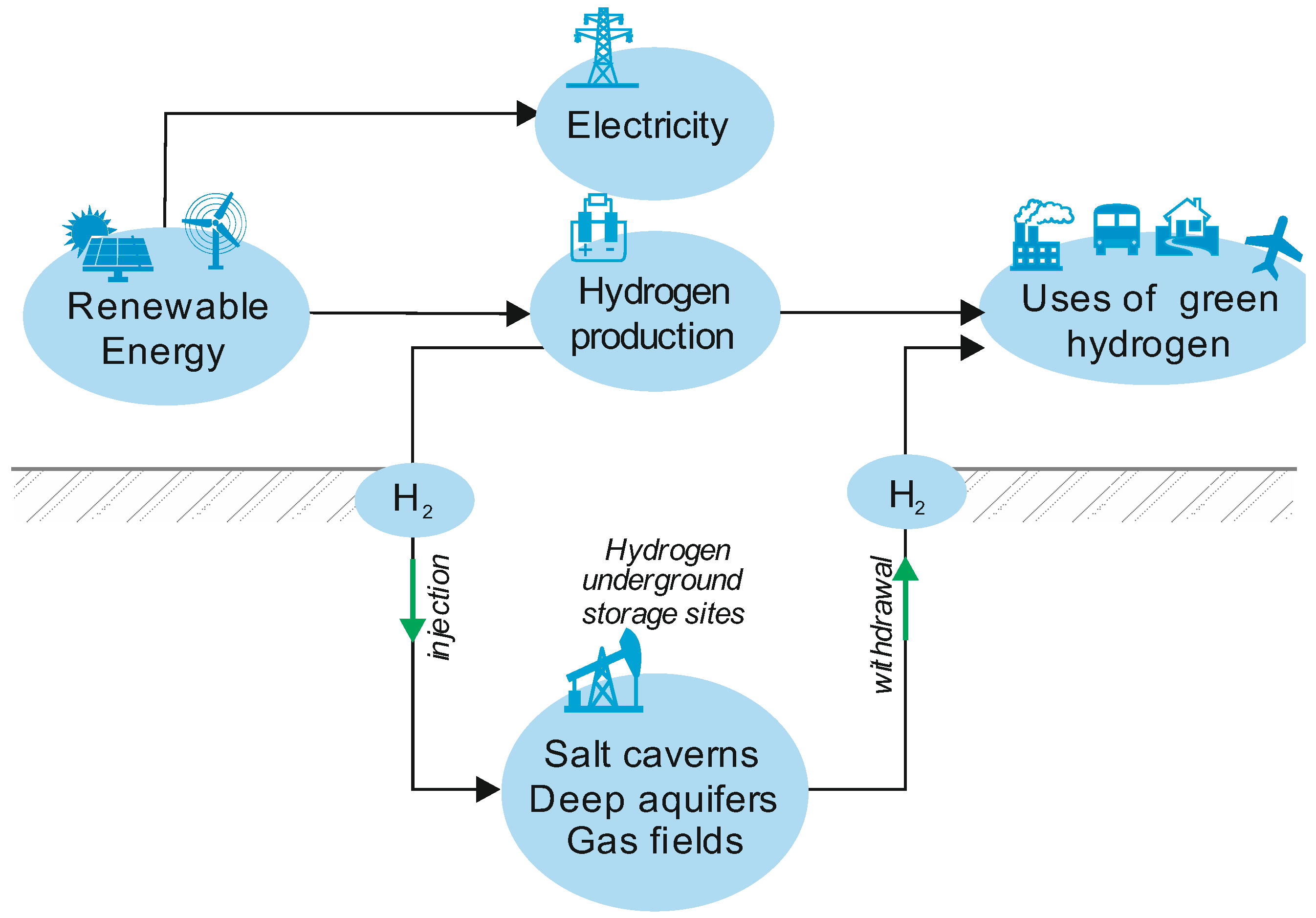

1.1. Underground Hydrogen Storage

1.2. Purpose and Scope of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

- A literature review was conducted to identify key scientific findings summarising the state-of-the-art UHS technologies for different types of geological structures. This review included articles that provided a broader view of UHS and the major issues identified by various authors across the eight topic areas considered (see Table 1). Publications that presented at least three of the eight aspects analysed were included.

- Identification and definition of thresholds and challenges facing UHS in the thematic areas considered.

3. Domains Relevant for UHS Development

3.1. Geological Aspects

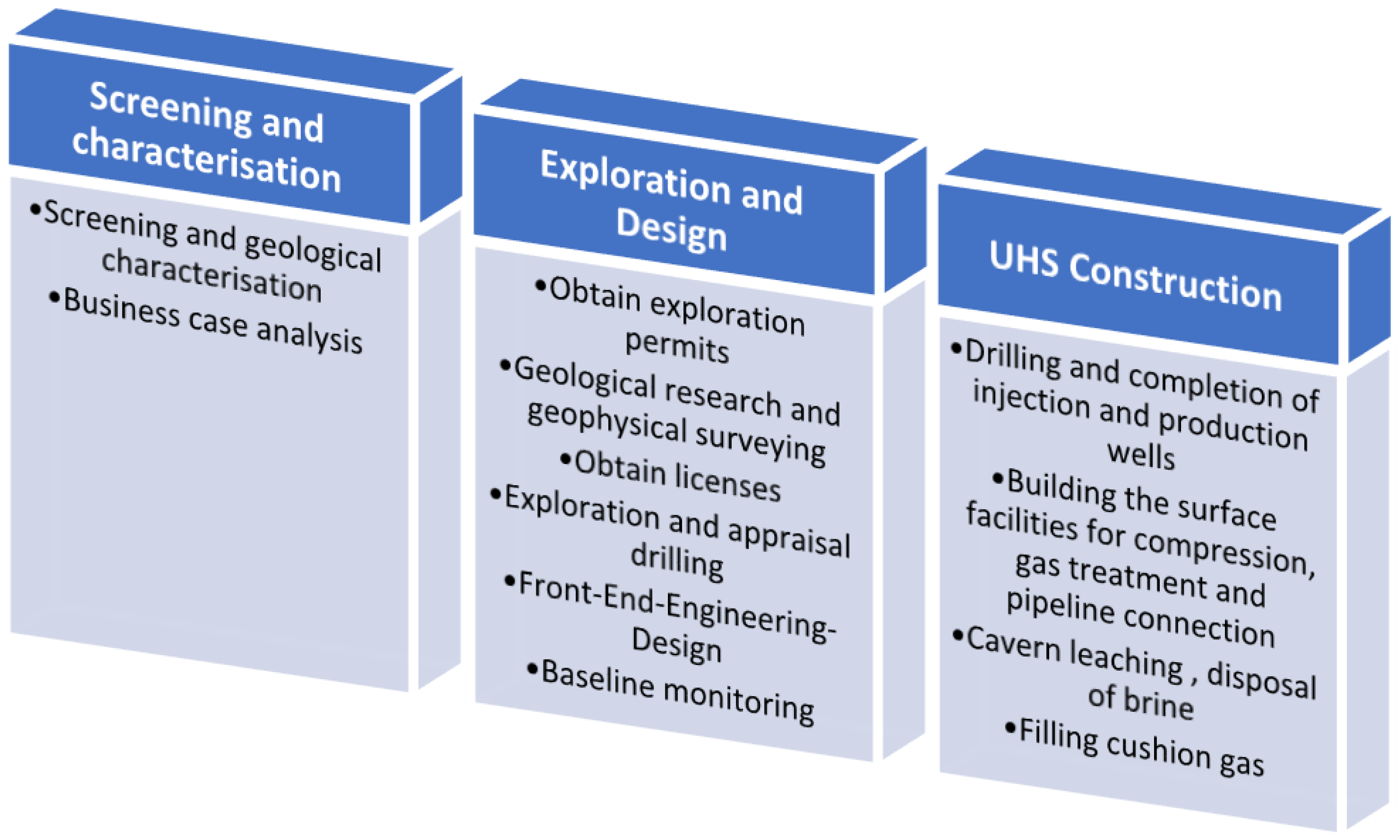

3.1.1. Screening, Selection, and Characterisation of Storage Sites

3.1.2. Storage Capacity

3.1.3. Hydrogen Interactions with Storage Complex

3.2. Technological Aspects

3.2.1. Storage Infrastructure

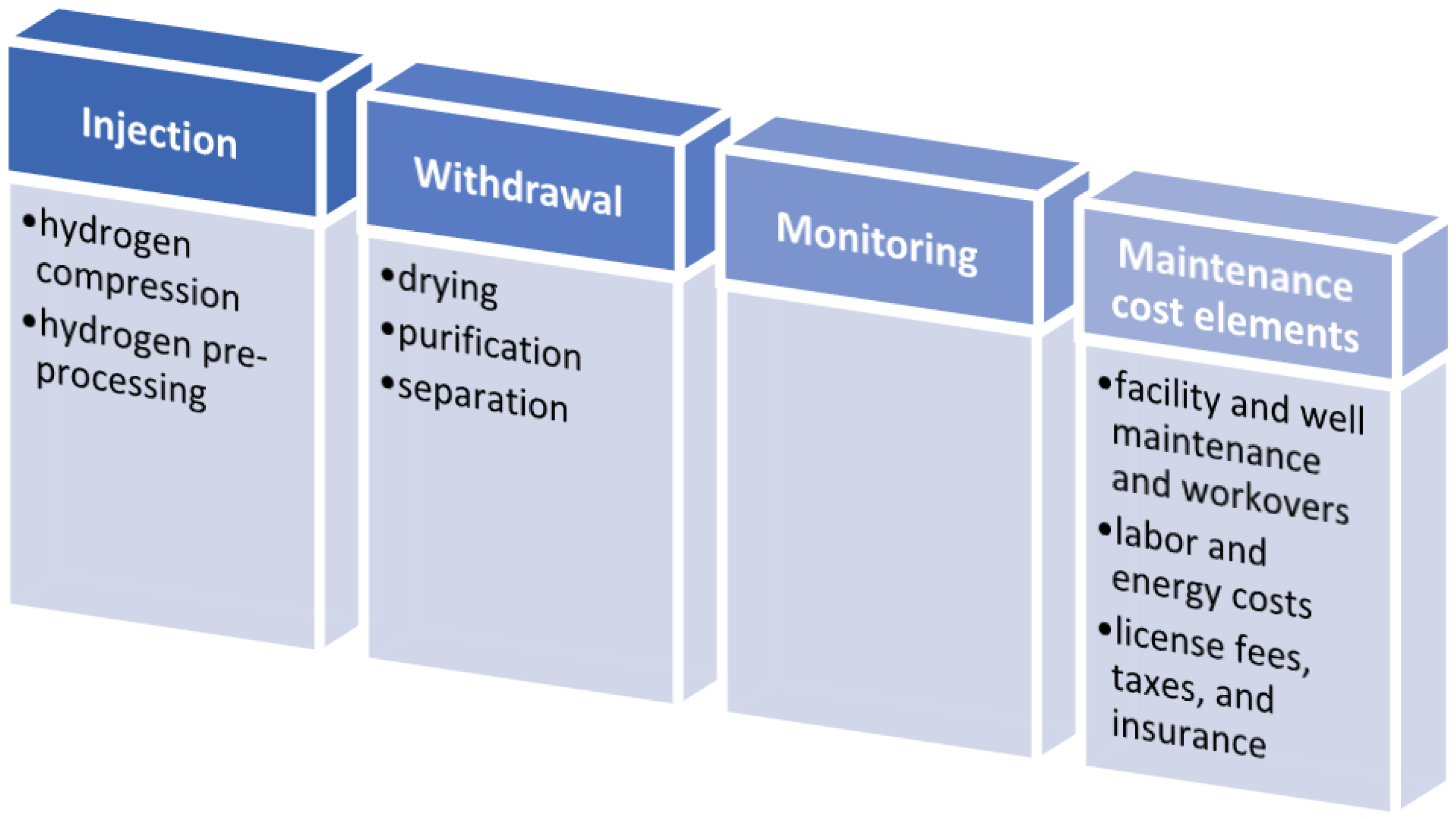

3.2.2. Storage Management

3.2.3. Storage Monitoring

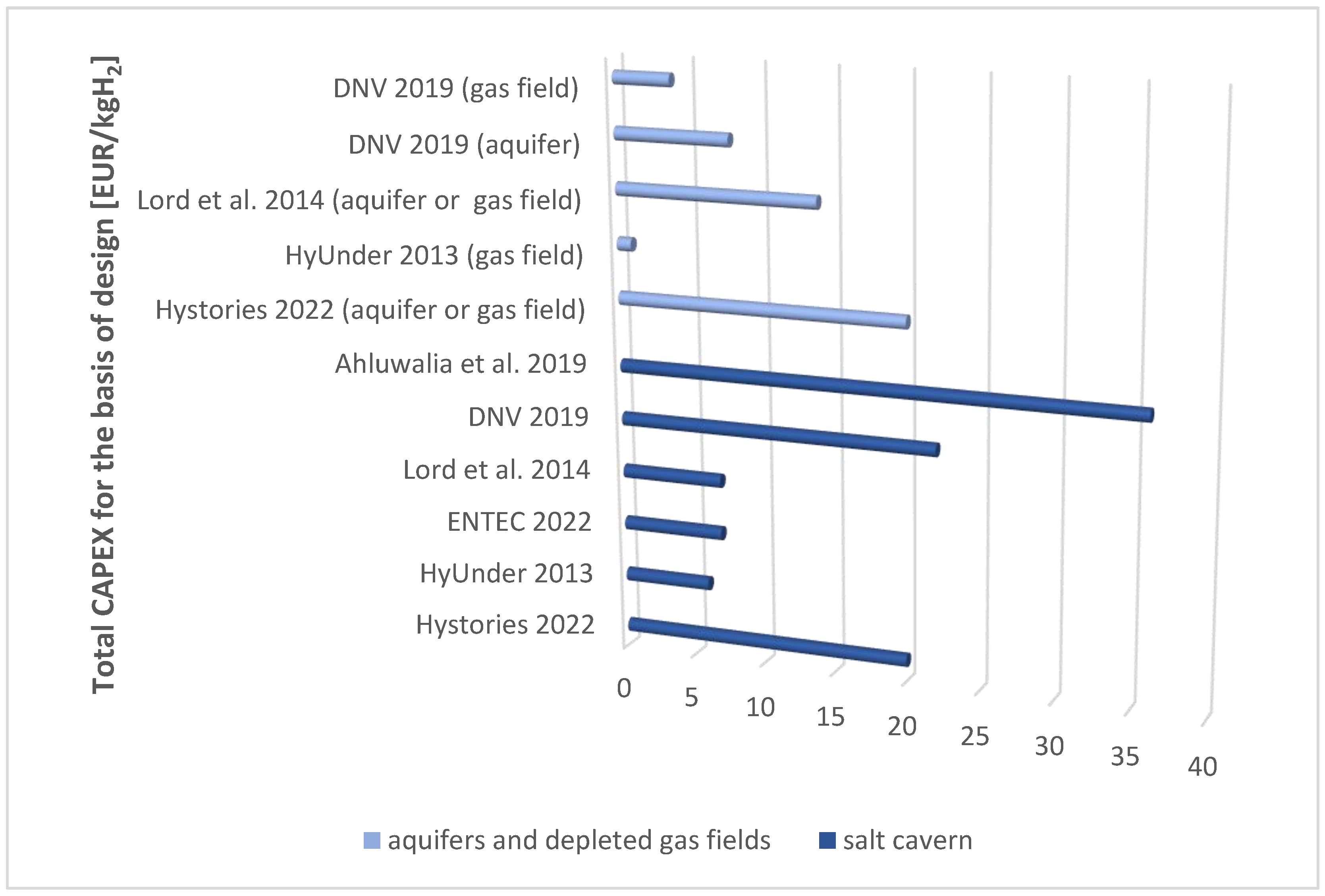

3.3. Economic Aspects

3.4. Policies and Regulations

4. Towards Underground Hydrogen Storage

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAPEX | Capital expenditure |

| CG | Cushion gas |

| OPEX | Operational expenditure |

| RES | Renewable energy source |

| UGS | Underground natural gas storage |

| UHS | Underground hydrogen storage |

References

- IRENA. International Co-Operation to Accelerate Green Hydrogen Deployment; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. COM/2019/640 Communication from the Commission—The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Council European Green Deal. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- European Commission. COM/2020/301 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions a Hydrogen Strategy for a Climate-Neutral Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for Energy in Focus: Hydrogen—Driving the Green Revolution. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/news/focus-hydrogen-driving-green-revolution-2021-04-14_en (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- European Commission. COM(2022) 230 Final Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions REPowerEU Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cihlar, J.; Mavins, D.; van der Leun, K. Picturing the Value of Underground Gas Storage to the European Hydrogen System; Gas Infrastructure Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shafi, M.; Massarweh, O.; Abushaikha, A.S.; Bicer, Y. A Review on Underground Gas Storage Systems: Natural Gas, Hydrogen and Carbon Sequestration. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 6251–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Characteristics and Prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Saddam, M.; Khan, H.; Kabir, A.; Amin Tuhin, R.; Azad, A.K.; Farrok, O. Hydrogen Energy Storage and Transportation Challenges: A Review of Recent Advances. In Hydrogen Energy Conversion and Management; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 255–287. ISBN 9780443153297. [Google Scholar]

- Aftab, A.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Xie, Q.; Machuca, L.L.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Toward a Fundamental Understanding of Geological Hydrogen Storage. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 3233–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.F.; Amro, M.M.; Nassan, T.; Alkan, H. Reservoir Engineering Aspects of Geologic Hydrogen Storage. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, IPTC 2024, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 12–14 February 2024; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hematpur, H.; Abdollahi, R.; Rostami, S.; Haghighi, M.; Blunt, M.J. Review of Underground Hydrogen Storage: Concepts and Challenges. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 7, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, N.; Scafidi, J.; Pickup, G.; Thaysen, E.M.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Wilkinson, M.; Satterley, A.K.; Booth, M.G.; Edlmann, K.; Haszeldine, R.S. Hydrogen Storage in Saline Aquifers: The Role of Cushion Gas for Injection and Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 39284–39296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruck, O.; Crotogino, F. Benchmarking of Selected Storage Options—“HyUnder” Project; IEA: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammed, N.S.; Haq, B.; Al Shehri, D.; Al-Ahmed, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Zaman, E. A Review on Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insight into Geological Sites, Influencing Factors and Future Outlook. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 461–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaid, H.B.; Emadi, H.; Watson, M.; Herd, B.L. A Comprehensive Literature Review on the Challenges Associated with Underground Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 10603–10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, C.; Dudun, A.; Samuel, S.A.; Esenenjor, P.; Muhammed, N.S.; Haq, B. A Review on Worldwide Underground Hydrogen Storage Operating and Potential Fields. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 22840–22880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B.; Tarkowski, P. Storage of Hydrogen, Natural Gas, and Carbon Dioxide—Geological and Legal Conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 20010–20022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, S.R.; Emadi, H.; Hussain, A.; Patange, P.; Watson, M. A Comprehensive Review of the Mechanisms and Efficiency of Underground Hydrogen Storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xin, Y.; Kou, Z.; Qu, Y.; Wang, L.; Ning, Y.; Ren, D. Numerical Study of the Efficiency of Underground Hydrogen Storage in Deep Saline Aquifers, Rock Springs Uplift, Wyoming. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivar, D.; Kumar, S.; Foroozesh, J. Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 23436–23462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, N.; Alcalde, J.; Miocic, J.M.; Hangx, S.J.T.; Kallmeyer, J.; Ostertag-Henning, C.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Thaysen, E.M.; Strobel, G.J.; Schmidt-Hattenberger, C.; et al. Enabling Large-Scale Hydrogen Storage in Porous Media—The Scientific Challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Arif, M.; Glatz, G.; Mahmoud, M.; Al Kobaisi, M.; Alafnan, S.; Iglauer, S. A Holistic Overview of Underground Hydrogen Storage: Influencing Factors, Current Understanding, and Outlook. Fuel 2022, 330, 125636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, R.; Wei, M.; Bai, B.; Xie, J.; Li, Y. A Comprehensive Review of Site Selection, Experiment and Numerical Simulation for Underground Hydrogen Storage. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 118, 205105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, A.; Mignard, D.; Wilkinson, M. Seasonal Storage of Hydrogen in a Depleted Natural Gas Reservoir. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 5549–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantakis, N.; Peecock, A.; Shahrokhi, O.; Pitchaimuthu, S.; Andresen, J.M. A Review of Analogue Case Studies Relevant to Large-Scale Underground Hydrogen Storage. Energy Reports 2024, 11, 2374–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpotu, W.F.; Akintola, J.; Obialor, M.C.; Philemon, U. Historical Review of Hydrogen Energy Storage Technology. World J. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maury Fernandez, D.; Emadi, H.; Hussain, A.; Thiyagarajan, S.R. A Holistic Review on Wellbore Integrity Challenges Associated with Underground Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 57, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miocic, J.; Heinemann, N.; Edlmann, K.; Scafidi, J.; Molaei, F.; Alcalde, J. Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Review. Geol. Soc. London, Spec. Publ. 2022, 528, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.S.A. A Review of Underground Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Gas Reservoirs: Insights into Various Rock-Fluid Interaction Mechanisms and Their Impact on the Process Integrity. Fuel 2023, 334, 126677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, A.; Zeng, L.; Nguele, R.; Sugai, Y.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Review on Using the Depleted Gas Reservoirs for the Underground H2 Storage: A Case Study in Niigata Prefecture, Japan. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 10579–10602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, L.K.; Kiran, R.; Okoroafor, E.R.; Wood, D.A. Review of Reservoir Challenges Associated with Subsurface Hydrogen Storage and Recovery in Depleted Oil and Gas Reservoirs. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Suo, S.; Hong, Y.; Wang, L.; Gan, Y. Gas Storage in Geological Formations: A Comparative Review on Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen Storage. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 26, 100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglayan, D.G.; Weber, N.; Heinrichs, H.U.; Linßen, J.; Robinius, M.; Kukla, P.A.; Stolten, D. Technical Potential of Salt Caverns for Hydrogen Storage in Europe. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 6793–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankof, L.; Tarkowski, R. Assessment of the Potential for Underground Hydrogen Storage in Bedded Salt Formation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 19479–19492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankof, L.; Urbańczyk, K.; Tarkowski, R. Assessment of the Potential for Underground Hydrogen Storage in Salt Domes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozarslan, A. Large-Scale Hydrogen Energy Storage in Salt Caverns. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 14265–14277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfilov, M. Underground and Pipeline Hydrogen Storage. In Compendium of Hydrogen Energy; Gupta, R.B., Basile, A., Veziroglu, T.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B. Use of Underground Space for the Storage of Selected Gases (CH4, H2, and CO2)—Possible Conflicts of Interest. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. Resour. Manag. 2021, 37, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitenbach, V.; Ganzer, L.; Albrecht, D.; Hagemann, B. Influence of Added Hydrogen on Underground Gas Storage: A Review of Key Issues. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 6927–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miocic, J.M.; Heinemann, N.; Alcalde, J.; Edlmann, K.; Schultz, R.A. Enabling Secure Subsurface Storage in Future Energy Systems. Geol. Soc. London Spec. Publ. 2023, 528, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruck, O.; Crotogino, F.; Prelicz, R.; Rudolph, T. A Overview on All Known Underground Storage Technologies for Hydrogen; IEA: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kalam, S.; Abu-Khamsin, S.A.; Kamal, M.S.; Abbasi, G.R.; Lashari, N.; Patil, S.; Abdurrahman, M. A Mini-Review on Underground Hydrogen Storage: Production to Field Studies. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 8128–8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gessel, S.; Hajibeygi, H. Hydrogen TCP-Task 42: Underground Hydrogen Storage—Technology Monitor Report 2023; IEA Hydrogen Technology Collaboration Program Task 42; IEA: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Global Hydrogen Review 2023; IEA: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- HyUnder Project HYUNDER. Available online: https://hyunder.eu/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- HyStock Project HyStock. Available online: https://www.hystock.nl/en (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- HyPSTER HyPSTER—1st Demonstrator for H2 Green Storage. Available online: https://hypster-project.eu/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Bauer, S. Underground Sun Storage: Final Report Public; Underground Sun Storage: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amirthan, T.; Perera, M.S.A. The Role of Storage Systems in Hydrogen Economy: A Review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 108, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, S.O.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Meenakshisundaram, A.; Ferron, P.; Oni, B.A. Economic, Social, and Regulatory Challenges of Green Hydrogen Production and Utilization in the US: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, C.; Patwardhan, S.D.; Iglauer, S.; Ben Mahmud, H.; Ali, M.F.J. A Critical Review on Parameters Affecting the Feasibility of Underground Hydrogen Storage. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 11658–11696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Song, K.; Sun, Y.; He, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, J. An Overview of Hydrogen Underground Storage Technology and Prospects in China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2014, 124, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhan, C.; Chen, W.; Cao, M.; Thanh, H.V.; Soltanian, M.R. Exploring Hydrogen Geologic Storage in China for Future Energy: Opportunities and Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 196, 114366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, E.; Tyrologou, P.; Couto, N.; Carneiro, J.F.; Scholtzová, E.; Koukouzas, N. Underground Hydrogen Storage: The Techno-Economic Perspective. Open Res. Eur. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari Raad, S.M.; Leonenko, Y.; Hassanzadeh, H. Hydrogen Storage in Saline Aquifers: Opportunities and Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, M.; Omirbekov, S.; Riazi, M. A Comprehensive Review of Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Oil and Gas Reservoirs: Parameters, Experiments, and Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 225, 116123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, G.; Yan, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Deng, P.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Qi, H. Technical Challenges and Opportunities of Hydrogen Storage: A Comprehensive Review on Different Types of Underground Storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhao, W.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Large Scale of Green Hydrogen Storage: Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulky, L.; Srivastava, S.; Lakshmi, T.; Sandadi, E.R.; Gour, S.; Thomas, N.A.; Shanmuga Priya, S.; Sudhakar, K. An Overview of Hydrogen Storage Technologies—Key Challenges and Opportunities. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 325, 129710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakipunda, G.C.; Franck Kouassi, A.K.; Ayimadu, E.T.; Komba, N.A.; Nadege, M.N.; Mgimba, M.M.; Ngata, M.R.; Yu, L. Underground Hydrogen Storage in Geological Formations: A Review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 6704–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Yin, X.; Ju, Y.; Iglauer, S. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Influencing Parameters and Future Outlook. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 294, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Al-Shargabi, M.; Wood, D.A.; Longe, P.O.; Mehrad, M.; Rukavishnikov, V.S. Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Review of Technological Developments, Challenges, and Opportunities. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, G.O.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Oni, B.A. A Comprehensive Review of Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insight into Geological Sites (Mechanisms), Economics, Barriers, and Future Outlook. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Vialle, S.; Ennis-King, J.; Esteban, L.; Sarmadivaleh, M.; Sarout, J.; Dautriat, J.; Giwelli, A.; Xie, Q. Role of Geochemical Reactions on Caprock Integrity during Underground Hydrogen Storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 65, 107414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliasz-Misiak, B.; Misiak, J. Underground Gas Storage in Saline Aquifers: Geological Aspects. Energies 2024, 17, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOE/NETL BEST PRACTICES: Risk Management and Simulation for Geologic Storage Projects; National Energy Technology Laboratory: Albany, OR, USA, 2017.

- Lankof, L.; Tarkowski, R. GIS-Based Analysis of Rock Salt Deposits’ Suitability for Underground Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27748–27765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska-Śmierzchalska, J.; Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B. Screening and Ranking Framework for Underground Hydrogen Storage Site Selection in Poland. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 4401–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barison, E.; Donda, F.; Merson, B.; Le Gallo, Y.; Réveillère, A. An Insight into Underground Hydrogen Storage in Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteldja, M.; Le Gallo, Y. From Hydrogen Storage Potential to Hydrogen Capacities in Underground Hydrogen Storages. In Proceedings of the 84th EAGE Annual Conference & Exhibition, Vienna, Austria, 5–8 June 2023; Volume 2023, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, B.; Mapar, M.; Davarazar, P.; Zandi, S.; Davarazar, M.; Jahanianfard, D.; Mohammadi, M. A Sustainable Approach for Site Selection of Underground Hydrogen Storage Facilities Using Fuzzy-Delphi Methodology. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2020, 2020, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaysen, E.M.; Armitage, T.; Slabon, L.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Edlmann, K. Microbial Risk Assessment for Underground Hydrogen Storage in Porous Rocks. Fuel 2023, 352, 128852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteldja, M.; Acosta, T.; Carlier, B.; Reveillere, A.; Jannel, H.; Fournier, C. Definition of Selection Criteria for a Hydrogen Storage Site in Depleted Fields or Aquifers; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Behrouz, T.; Askari, A.; Forghaani, S.; Basirat, R.M.; Teymouri, A.; Bonyad, H. Fast Screening Method to Prioritize Underground Gas Storage Structures for Site Selection. In Proceedings of the International Gas Union Research Conference (IGRC 2014), Copenhagen, Denmark, 17–19 September 2014; Volume 3, pp. 2378–2386. [Google Scholar]

- Thaysen, E.M.; McMahon, S.; Strobel, G.J.; Butler, I.B.; Ngwenya, B.T.; Heinemann, N.; Wilkinson, M.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; McDermott, C.I.; Edlmann, K. Estimating Microbial Growth and Hydrogen Consumption in Hydrogen Storage in Porous Media. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA GHG. CCS Site Characterisation Criteria; IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme: Cheltenham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alms, K.; Ahrens, B.; Graf, M.; Nehler, M. Linking Geological and Infrastructural Requirements for Large-Scale Underground Hydrogen Storage in Germany. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1172003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, A.J.; Yousefi, S.H.; Wilkinson, M.; Groenenberg, R.M. Hydrogen Storage Potential of Existing European Gas Storage Sites in Depleted Gas Fields and Aquifers; IEA: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Luboń, K.T.; Tarkowski, R. Numerical Simulation of Hydrogen Storage in the Konary Deep Saline Aquifer Trap. Gospod. Surowcami Miner.–Miner. Resour. Manag. 2023, 39, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scafidi, J.; Wilkinson, M.; Gilfillan, S.M.V.; Heinemann, N.; Haszeldine, R.S. A Quantitative Assessment of the Hydrogen Storage Capacity of the UK Continental Shelf. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 8629–8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventisky, E.; Gilfillan, S.M.V. Assessment of the Onshore Storage Capacity of Hydrogen in Natural Gas Fields in Argentina. Geoenergy 2023, 18, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmel, B.; Bjørkvik, B.; Frøyen, T.L.; Cerasi, P.; Stroisz, A. Evaluating the Hydrogen Storage Potential of Shut down Oil and Gas Fields along the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 24385–24400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Joonaki, E.; Edlmann, K.; Haszeldine, R.S. Offshore Geological Storage of Hydrogen: Is This Our Best Option to Achieve Net-Zero? ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 2181–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouli-Castillo, J.; Heinemann, N.; Edlmann, K. Mapping Geological Hydrogen Storage Capacity and Regional Heating Demands: An Applied UK Case Study. Appl. Energy 2021, 283, 116348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hévin, G. Underground Storage of Hydrogen in Salt Caverns. In Proceedings of the European Workshop on Underground Energy Storage, Paris, France, 7–8 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tarkowski, R.; Lankof, L.; Luboń, K.; Michalski, J.; Le Gallo, Y.; Tarkowski, R. Hydrogen Storage Capacity of Salt Caverns and Deep Aquifers versus Demand for Hydrogen Storage: A Case Study of Poland. Appl. Energy 2024, 355, 122268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotogino, F.; Donadei, S.; Bünger, U.; Landinger, H. Large-Scale Hydrogen Underground Storage for Securing Future Energy Supplies. In Proceedings of the WHEC, Essen, Germany, 16–21 May 2010; Institute of Energy Research-Fuel Cells: Essen, Germany, 2010; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, C.; Smith, N.; Kirk, K.; Bow, J.; Vosper, H.; Rautenberg, S.; Cartwright, C.; Anthonsen, K.; Bader, A.G.; Dudu, A.; et al. Opportunities in Europe for Geological Storage of Hydrogen in Depleted Hydrocarbon Fields and Saline Aquifers. D1.4-1-Project Hystories. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384013260_Opportunities_in_Europe_for_geological_storage_of_hydrogen_in_depleted_hydrocarbon_fields_and_saline_aquifers (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- HyUnder. Assessment of the Potential the Actors and Relevant Usiness Cases for Large Scale and Long Term Storage of Renewable Electricity by Hydrogen Underground Storage in Europe: Executive Summary; IEA: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mouli-Castillo, J.; Edlmann, K.; Thaysen, E.; Scafidi, J. Enabling Large-Scale Offshore Wind with Underground Hydrogen Storage. First Break 2021, 39, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juez-Larré, J.; van Gessel, S.; Dalman, R.; Remmelts, G.; Groenenberg, R. Assessment of Underground Energy Storage Potential to Support the Energy Transition in the Netherlands. First Break 2019, 37, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliasz-Misiak, B.; Lewandowska-Śmierzchalska, J.; Matuła, R. Hydrogen Storage Potential in Natural Gas Deposits in the Polish Lowlands. Energies 2024, 17, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, J.M.; English, K.L. Overview of Hydrogen and Geostorage Potential in Ireland. First Break 2023, 41, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankof, L.; Luboń, K.; Le Gallo, Y.; Tarkowski, R. The Ranking of Geological Structures in Deep Aquifers of the Polish Lowlands for Underground Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 62, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Czapowski, G. Salt Domes in Poland—Potential Sites for Hydrogen Storage in Caverns. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 21414–21427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.; Bünger, U.; Crotogino, F.; Donadei, S.; Schneider, G.S.; Pregger, T.; Cao, K.K.; Heide, D. Hydrogen Generation by Electrolysis and Storage in Salt Caverns: Potentials, Economics and Systems Aspects with Regard to the German Energy Transition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 13427–13443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Ma, Z.; Nasrabadi, H.; Chen, B.; Saad Mehana, M.Z.; Van Wijk, J. Capacity Assessment and Cost Analysis of Geologic Storage of Hydrogen: A Case Study in Intermountain-West Region USA. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 9008–9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackey, G.; Freeman, G.M.; Buscheck, T.A.; Haeri, F.; White, J.A.; Huerta, N.; Goodman, A. Characterizing Hydrogen Storage Potential in U.S. Underground Gas Storage Facilities. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2022GL101420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotta, M.; Tassinari, C.; Larizatti Zacharias, L.G.; van der Zwaan, B.; Peyerl, D. Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Offshore Gas Fields in Brazil: Potential and Implications for Energy Security. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 39967–39980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemme, C.; van Berk, W. Potential Risk of H2S Generation and Release in Salt Cavern Gas Storage. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 47, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Jiang, D.; Liu, C. Computed Tomography Analysis on Cyclic Fatigue and Damage Properties of Rock Salt under Gas Pressure. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 134, 105523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijnenburg, R.P.J.; Verberne, B.A.; Hangx, S.J.T.; Spiers, C.J. Inelastic Deformation of the Slochteren Sandstone: Stress-Strain Relations and Implications for Induced Seismicity in the Groningen Gas Field. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2019, 124, 5254–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truche, L.; Jodin-Caumon, M.C.; Lerouge, C.; Berger, G.; Mosser-Ruck, R.; Giffaut, E.; Michau, N. Sulphide Mineral Reactions in Clay-Rich Rock Induced by High Hydrogen Pressure. Application to Disturbed or Natural Settings up to 250 °C and 30 Bar. Chem. Geol. 2013, 351, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarrasa, V.; Makhnenko, R.; Gheibi, S. Geomechanical Analysis of the Influence of CO2 Injection Location on Fault Stability. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 8, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Jun, S.; Na, Y.; Kim, K.; Jang, Y.; Wang, J. Geomechanical Challenges during Geological CO2 Storage: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 456, 140968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutqvist, J. The Geomechanics of CO2 Storage in Deep Sedimentary Formations. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2012, 30, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Jadhawar, P.; Bagala, S. Geochemical Effects on Storage Gases and Reservoir Rock during Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Depleted North Sea Oil Reservoir Case Study. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekta, A.E.; Pichavant, M.; Audigane, P. Evaluation of Geochemical Reactivity of Hydrogen in Sandstone: Application to Geological Storage. Appl. Geochem. 2018, 95, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Z.; Zeng, L.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Q. Geochemical Reactions-Induced Hydrogen Loss during Underground Hydrogen Storage in Sandstone Reservoirs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 19998–20009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannayebi, N.; Azizmohammadi, S.; De Lucia, M.; Ott, H. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Application of Geochemical Modelling in a Case Study in the Molasse Basin, Upper Austria. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackie-Otoo, B.N.; Haq, M.B. A Comprehensive Review on Geo-Storage of H2 in Salt Caverns: Prospect and Research Advances. Fuel 2024, 356, 129609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Adie, K.; Cowen, T.; Thaysen, E.M.; Heinemann, N.; Butler, I.B.; Wilkinson, M.; Edlmann, K. Geological Hydrogen Storage: Geochemical Reactivity of Hydrogen with Sandstone Reservoirs. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 2203–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemme, C.; van Berk, W. Hydrogeochemical Modeling to Identify Potential Risks of Underground Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Gas Fields. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labus, K.; Tarkowski, R. Modeling Hydrogen—Rock—Brine Interactions for the Jurassic Reservoir and Cap Rocks from Polish Lowlands. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 10947–10962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truche, L.; Berger, G.; Albrecht, A.; Domergue, L. Engineered Materials as Potential Geocatalysts in Deep Geological Nuclear Waste Repositories: A Case Study of the Stainless Steel Catalytic Effect on Nitrate Reduction by Hydrogen. Appl. Geochem. 2013, 35, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvoisin, B.; Baumgartner, L.P. Mineral Dissolution and Precipitation Under Stress: Model Formulation and Application to Metamorphic Reactions. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2021, 22, e2021GC009633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier, M.; Leone, L.; Greneche, J.M.; Giffaut, E.; Charlet, L. Adsorption of Hydrogen Gas and Redox Processes in Clays. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3574–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelli, C.; Bardelli, F.; Vitillo, J.G.J.G.; Didier, M.; Brendle, J.; Cavicchia, D.R.D.R.; Robinet, J.-C.J.C.; Charlet, L. Hydrogen Adsorption and Diffusion in Synthetic Na-Montmorillonites at High Pressures and Temperature. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 2698–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, C.J.; Hangx, S.J.T.; Niemeijer, A.R. New Approaches in Experimental Research on Rock and Fault Behaviour in the Groningen Gas Field. Geol. Mijnb./Neth. J. Geosci. 2017, 96, s55–s69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentinck, H.M.; Busch, A. Modelling of CO2 Diffusion and Related Poro-Elastic Effects in a Smectite-Rich Cap Rock above a Reservoir Used for CO2 Storage. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2017, 454, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappa, F.; Rutqvist, J. Modeling of Coupled Deformation and Permeability Evolution during Fault Reactivation Induced by Deep Underground Injection of CO2. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, W.S.; Huang, L.N. Microbial Diversity in Extreme Environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 20, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopffel, N.; An-Stepec, B.A.; Bombach, P.; Wagner, M.; Passaris, E. Microbial Life in Salt Caverns and Their Influence on H2 Storage—Current Knowledge and Open Questions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 58, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopffel, N.; Jansen, S.; Gerritse, J. Microbial Side Effects of Underground Hydrogen Storage—Knowledge Gaps, Risks and Opportunities for Successful Implementation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 8594–8606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, S.P.; Barnett, M.J.; Field, L.P.; Milodowski, A.E. Subsurface Microbial Hydrogen Cycling: Natural Occurrence and Implications for Industry. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thullner, M.; Regnier, P. Microbial Controls on the Biogeochemical Dynamics in the Subsurface. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2019, 85, 265–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Pickup, G.; Sorbie, K.; de Rezende, J.R.; Zarei, F.; Mackay, E. Bioreaction Coupled Flow Simulations: Impacts of Methanogenesis on Seasonal Underground Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, A.; Alsop, E.B.; Lomans, B.P.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Head, I.M.; Tsesmetzis, N. Succession in the Petroleum Reservoir Microbiome through an Oil Field Production Lifecycle. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2141–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardez, L.A.; De Lima, L.R.P.A.; De Jesus, E.B.; Ramos, C.L.S.; Almeida, P.F. A Kinetic Study on Bacterial Sulfate Reduction. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 36, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, B.B.; Isaksen, M.F.; Jannasch, H.W. Bacterial Sulfate Reduction Above 100C in Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Sediments. Science 1992, 258, 1756–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machel, H.G. Bacterial and Thermochemical Sulfate Reduction in Diagenetic Settings—Old and New Insights. Sediment. Geol. 2001, 140, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G.; Hagemann, B.; Huppertz, T.M.; Ganzer, L. Underground Bio-Methanation: Concept and Potential. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 123, 109747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeland, R.H.; Rosenzweig, W.D.; Powers, D.W. Isolation of a 250 Million-Year-Old Halotolerant Bacterium from a Primary Salt Crystal. Nature 2000, 407, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Galinski, E.A.; Grant, W.D.; Oren, A.; Ventosa, A. Halophiles 2010: Life in Saline Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, L.; Popp, D.; Nowack, G.; Bombach, P.; Vogt, C.; Richnow, H.H. Structural Analysis of Microbiomes from Salt Caverns Used for Underground Gas Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 20684–20694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmigáň, P.; Greksák, M.; Kozánková, J.; Buzek, F.; Onderka, V.; Wolf, I. Methanogenic Bacteria as a Key Factor Involved in Changes of Town Gas Stored in an Underground Reservoir. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990, 73, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremosa, J.; Jakobsen, R.; Le Gallo, Y. Assessing and Modeling Hydrogen Reactivity in Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Review and Models Simulating the Lobodice Town Gas Storage. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1145978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Beyer, C.; Dethlefsen, F.; Dietrich, P.; Duttmann, R.; Ebert, M.; Feeser, V.; Görke, U.; Köber, R.; Kolditz, O.; et al. Impacts of the Use of the Geological Subsurface for Energy Storage: An Investigation Concept. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 70, 3935–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, M. Underground Sun Storage Results and Outlook. In Proceedings of the EAGE/DGMK Joint Workshop on Underground Storage of Hydrogen, Celle, Germany, 24 April 2019; European Association of Geoscientists and Engineers, EAGE: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 2019, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Vavra, C.L.; Kaldi, J.G.; Sneider, R.M. Geological Applications of Capillary Pressure: A Review. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 1992, 76, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veil, J.A.; Puder, M.G.; Elcock, D.; Redweik, J.R.J. A White Paper Describing Produced Water from Production of Crude Oil, Natural Gas, and Coal Bed Methane; Argonne National Laboratory: Lemont, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Jie, C.; Deyi, J.; Xilin, S.; Yinping, L.; Daemen, J.J.K.; Chunhe, Y. Tightness and Suitability Evaluation of Abandoned Salt Caverns Served as Hydrocarbon Energies Storage under Adverse Geological Conditions (AGC). Appl. Energy 2016, 178, 703–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, W.A.; Mackenzie, A.S.; Mann, D.M.; Quigley, T.M. The Movement and Entrapment of Petroleum Fluids in the Subsurface. J. Geol. Soc. London 1987, 144, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh Kumar, K.; Honorio, H.; Chandra, D.; Lesueur, M.; Hajibeygi, H. Comprehensive Review of Geomechanics of Underground Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Reservoirs and Salt Caverns. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautriat, J.; Gland, N.; Guelard, J.; Dimanov, A.; Raphanel, J.L. Axial and Radial Permeability Evolutions of Compressed Sandstones: End Effects and Shear-Band Induced Permeability Anisotropy. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2009, 166, 1037–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermeier, R.M. Deepwater Gulf of Mexico Turbidites—Compaction Effects on Porosity and Permeability. SPE Form. Eval. 1995, 10, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckale, J. Moderate-to-Large Seismicity Induced by Hydrocarbon Production. Lead. Edge 2010, 29, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangx, S.; Bakker, E.; Bertier, P.; Nover, G.; Busch, A. Chemical–Mechanical Coupling Observed for Depleted Oil Reservoirs Subjected to Long-Term CO2-Exposure—A Case Study of the Werkendam Natural CO2 Analogue Field. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2015, 428, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, D. Comprehensive Review of Caprock-Sealing Mechanisms for Geologic Carbon Sequestration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Shi, L.; Li, C.; Tang, L.; Zhong, R. Injection–Production Mechanisms and Key Evaluation Technologies for Underground Gas Storages Rebuilt from Gas Reservoirs. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2018, 5, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teatini, P.; Castelletto, N.; Ferronato, M.; Gambolati, G.; Janna, C.; Cairo, E.; Marzorati, D.; Colombo, D.; Ferretti, A.; Bagliani, A.; et al. Geomechanical Response to Seasonal Gas Storage in Depleted Reservoirs: A Case Study in the Po River Basin, Italy. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2011, 116, F02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhao, K.; Li, C.; Shi, L.; Tang, L. Key Evaluation Techniques in the Process of Gas Reservoir Being Converted into Underground Gas Storage. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2017, 44, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardelli, F.; Mondelli, C.; Didier, M.; Vitillo, J.G.; Cavicchia, D.R.; Robinet, J.C.; Leone, L.; Charlet, L. Hydrogen Uptake and Diffusion in Callovo-Oxfordian Clay Rock for Nuclear Waste Disposal Technology. Appl. Geochem. 2014, 49, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noort, R. Effects of Clay Swelling or Shrinkage on Shale Caprock Integrity. In Proceedings of the 80th EAGE Conference and Exhibition 2018, Copenhagen, Denmark, 11–14 June 2018; Volume 2018, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, H.B.J.; Veldhuis, I.; Richardson, R.N. Underground Hydrogen Storage in the UK. Geol. Soc. London Spec. Publ. 2009, 313, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US-DOE. Ensuring Safe and Reliable Underground Natural Gas Storage Final Report of the Interagency Task Force on Natural Gas Storage Safety; US Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Peach, C.J. Influence of Deformation on the Fluid Transport Properties of Salt Rocks; Facultiet Aardwetenschappen der Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; ISBN 9789071577314. [Google Scholar]

- Houben, M.E.; ten Hove, A.; Peach, C.J.; Spiers, C.J.; Houben, M.E.; ten Hove, A.; Peach, C.J.; Spiers, C.J. Crack Healing in Rocksalt via Diffusion in Adsorbed Aqueous Films: Microphysical Modelling versus Experiments. Phys. Chem. Earth 2013, 64, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arson, C.; Xu, H.; Chester, F.M. On the Definition of Damage in Time-Dependent Healing Models for Salt Rock. Géotechnique Lett. 2015, 2, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsche, U.; Hampel, A. Rock Salt—The Mechanical Properties of the Host Rock Material for a Radioactive Waste Repository. Eng. Geol. 1999, 52, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, C.J.; Schutjens, P.M.T.M.; Brzesowsky, R.H.; Peach, C.J.; Liezenberg, J.L.; Zwart, H.J. Experimental Determination of Constitutive Parameters Governing Creep of Rocksalt by Pressure Solution. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 1990, 54, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urai, J.L.; Spiers, C.J. The Effect of Grain Boundary Water on Deformation Mechanisms and Rheology of Rocksalt during Long-Term Deformation. In The Mechanical Behavior of Salt—Understanding of THMC Processes in Salt, Proceedings of the 6th Conference on the Mechanical Behavior of Salt (SaltMech6), Hannover, Germany, 22–25 May 2007; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urai, J.L.; Spiers, C.J.; Zwart, H.J.; Lister, G.S. Weakening of Rock Salt by Water during Long-Term Creep. Nature 1986, 324, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh Kumar, K.; Makhmutov, A.; Spiers, C.J.; Hajibeygi, H. Geomechanical Simulation of Energy Storage in Salt Formations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Essen, H. Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World the Environmental Impacts of Increased International Road and Rail Freight Transport—Past Trends and Future Perspectives. In Proceedings of the OECD/ITF Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World, Guadalajara, Mexico, 10–12 November 2008; OECD/International Transport Forum: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran, R.; Teodoriu, C.; Dadmohammadi, Y.; Nygaard, R.; Wood, D.; Mokhtari, M.; Salehi, S. Identification and Evaluation of Well Integrity and Causes of Failure of Well Integrity Barriers (A Review). J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 45, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritto, C.; De Simoni, M.; Roccaro, E.; Pontiggia, M.; Panfili, P.; del Gaudio, L.; Visconti, L.; Iorio, V.S.; dell’Elce, G. Underground Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Gas Reservoirs: Opportunity Identification and Project Maturation Steps. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 96, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Jessen, K.; Tsotsis, T.T. Impacts of the Subsurface Storage of Natural Gas and Hydrogen Mixtures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8757–8773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgaddafi, R.; Ahmed, R.; Shah, S. Corrosion of Carbon Steel in CO2 Saturated Brine at Elevated Temperatures. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherik, A.M. Trends in Oil and Gas Corrosion Research and Technologies; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; ISBN 9780081011058. [Google Scholar]

- Askari, M.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Jafari, R.; Hamghalam, P.; Hajizadeh, A. Downhole Corrosion Inhibitors for Oil and Gas Production—A Review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 6, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfilov, M. Underground Storage of Hydrogen: In Situ Self-Organisation and Methane Generation. Transp. Porous Media 2010, 85, 841–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, N.S.; Haq, M.B.; Al Shehri, D.A.; Al-Ahmed, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Zaman, E.; Iglauer, S. Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Gas Reservoirs: A Comprehensive Review. Fuel 2023, 337, 127032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautmann, A.; Oberndorfer, M.; Mori, G.; Bauer, S. Susceptibility of Selected Steel Grades to Hydrogen Embrittlement—Simulating Field Conditions by Performing Laboratory Wheel Tests with Autoclaves. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 2019, Nashville, TN, USA, 24–28 March 2019; p. NACE-2019-13402. [Google Scholar]

- Loder, B. Summary Report on Steels K55, L80 Including H2S Containing Atmosphere and a Quenched Reference Material; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Patel, H.; Salehi, S. Numerical Modeling and Experimental Study of Elastomer Seal Assembly in Downhole Wellbore Equipment: Effect of Material and Chemical Swelling. Polym. Test. 2020, 89, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Salehi, S. Failure Mechanisms of the Wellbore Mechanical Barrier Systems: Implications for Well Integrity. J. Energy Resour. Technol. Trans. ASME 2021, 143, 073007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Salehi, S.; Ezeakacha, C.; Teodoriu, C. Experimental Investigation of Elastomers in Downhole Seal Elements: Implications for Safety. Polym. Test. 2019, 76, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.M. Degradation of Elastomers. In Latex Dipping; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, H.J. Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Monomer (EPDM) and Fluorocarbon (FKM) Elastomers in the Geothermal Environment. J. Test. Eval. 1983, 11, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadrami, H.; Emadi, H.; Hussain, A. Investigating the Effects of Hydrogen on Wet Cement for Underground Hydrogen Storage Applications in Oil and Gas Wells. Int. J. Struct. Constr. Eng. 2022, 16, 252–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bihua, X.; Bin, Y.; Yongqing, W. Anti-Corrosion Cement for Sour Gas (H2S-CO2) Storage and Production of HTHP Deep Wells. Appl. Geochem. 2018, 96, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutchko, B.G.; Strazisar, B.R.; Hawthorne, S.B.; Lopano, C.L.; Miller, D.J.; Hakala, J.A.; Guthrie, G.D. H2S–CO2 Reaction with Hydrated Class H Well Cement: Acid-Gas Injection and CO2 Co-Sequestration. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Lv, F.; Feng, Q.; Zheng, Y. Enhancing the CO2-H2S Corrosion Resistance of Oil Well Cement with a Modified Epoxy Resin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugarte, E.R.; Tetteh, D.; Salehi, S. Experimental Studies of Well Integrity in Cementing during Underground Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbakhsh, A.; Liu, Q.; Mosleh, M.H.; Agrawal, H.; Farooqui, N.M.; Buckman, J.; Recasens, M.; Maroto-Valer, M.; Korre, A.; Durucan, S. An Investigation into CO2–Brine–Cement–Reservoir Rock Interactions for Wellbore Integrity in CO2 Geological Storage. Energies 2021, 14, 5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemet, N.; Pironon, J.; Lagneau, V.; Saint-Marc, J. Armouring of Well Cement in H2S–CO2 Saturated Brine by Calcite Coating—Experiments and Numerical Modelling. Appl. Geochem. 2012, 27, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemet, N.; Pironon, J.; Saint-Marc, J. Mineralogical Changes of a Well Cement in Various H2S-CO2(-Brine) Fluids at High Pressure and Temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhamis, M.; Imqam, A. A Simple Classification of Wellbore Integrity Problems Related to Fluids Migration. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 6131–6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yan, Y.; Wang, P.; Yan, X. A Risk Analysis Model for Underground Gas Storage Well Integrity Failure. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2019, 62, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Shen, A.; Meng, L.; Zhu, J.; Song, K. Well Completion Issues for Underground Gas Storage in Oil and Gas Reservoirs in China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 171, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Agostini, F.; Skoczylas, F.; Jeannin, L.; Potier, L. Poromechanical Properties of a Sandstone Under Different Stress States. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 3699–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harati, S.; Rezaei Gomari, S.; Ramegowda, M.; Pak, T. Multi-Criteria Site Selection Workflow for Geological Storage of Hydrogen in Depleted Gas Fields: A Case for the UK. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhawar, P.; Saeed, M. Mechanistic Evaluation of the Reservoir Engineering Performance for the Underground Hydrogen Storage in a Deep North Sea Aquifer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luboń, K.; Tarkowski, R. The Influence of the First Filling Period Length and Reservoir Level Depth on the Operation of Underground Hydrogen Storage in a Deep Aquifer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 1024–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luboń, K.; Tarkowski, R. Influence of Capillary Threshold Pressure and Injection Well Location on the Dynamic CO2 and H2 Storage Capacity for the Deep Geological Structure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 30048–30060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luboń, K.; Tarkowski, R. Numerical Simulation of Hydrogen Injection and Withdrawal to and from a Deep Aquifer in NW Poland. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 2068–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luboń, K.; Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B. Impact of Depth on Underground Hydrogen Storage Operations in Deep Aquifers. Energies 2024, 17, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marousi, G.E. Hydrogen and Energy Storage within Porous Rocks. Ph.D. Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki School of Geology, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ershadnia, R.; Singh, M.; Mahmoodpour, S.; Meyal, A.; Moeini, F.; Hosseini, S.A.; Sturmer, D.M.; Rasoulzadeh, M.; Dai, Z.; Soltanian, M.R. Impact of Geological and Operational Conditions on Underground Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 1450–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünger, U.; Michalski, J.; Crotogino, F.; Kruck, O. Large-Scale Underground Storage of Hydrogen for the Grid Integration of Renewable Energy and Other Applications. In Compendium of Hydrogen Energy; Ball, M., Basile, A., Veziroğlu, T.N., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 133–163. ISBN 978-1-78242-364-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sainz-Garcia, A.; Abarca, E.; Rubi, V.; Grandia, F. Assessment of Feasible Strategies for Seasonal Underground Hydrogen Storage in a Saline Aquifer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 16657–16666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foh, S.; Novil, M.; Rockar, E.; Randolph, P. Underground Hydrogen Storage, Final Report; Brookhaven National Laboratory: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lysyy, M.; Fernø, M.; Ersland, G. Seasonal Hydrogen Storage in a Depleted Oil and Gas Field. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 49, 25160–25174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaani, M.; Sedaee, B.; Asadian-Pakfar, M. Role of Cushion Gas on Underground Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Oil Reservoirs. J. Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. Numerical Simulation of the Impact of Different Cushion Gases on Underground Hydrogen Storage in Aquifers Based on an Experimentally-Benchmarked Equation-of-State. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domonik, A.; Dziedzic, A.; Jarząbkiewicz, A.; Łukasiak, D.; Łukaszewski, P.; Pinińska, J. Zintegrowany System Gromadzenia, Przetwarzania i Wizualizacji Danych Geomechanicznych-Baza Danych Geomechanicznych. Górnictwo Geoinżynieria 2009, 33, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 27914:2017; Carbon Dioxide Capture, Transportation and Geological Storage—Geological Storage. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Zeng, L.; Sarmadivaleh, M.; Saeedi, A.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Xie, Q. Storage Integrity during Underground Hydrogen Storage in Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 247, 104625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugarte, E.R.; Salehi, S. A Review on Well Integrity Issues for Underground Hydrogen Storage. J. Energy Resour. Technol. Trans. 2022, 144, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, K.; van Unen, M.; Brunner, L.G.; Groenenberg, R.M. Inventory of Risks Associated with Underground Storage of Compressed Air (CAES) and Hydrogen (UHS), and Qualitative Comparison of Risks of UHS vs. Underground Storage of Natural Gas (UGS); Underground Storage of Natural Gas: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020.

- Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Javadpour, F.; Feng, Q.; Cha, L. Hydrogen Diffusion in Clay Slit: Implications for the Geological Storage. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 7651–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C.J.; Roberts, J.J.; Johnson, G.; Edlmann, K.; Flude, S.; Shipton, Z.K. Natural Hydrogen Seeps as Analogues to Inform Monitoring of Engineered Geological Hydrogen Storage. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2023, 528, 461–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Niasar, V.; Ma, L.; Xie, Q. Effect of Salinity, Mineralogy, and Organic Materials in Hydrogen Wetting and Its Implications for Underground Hydrogen Storage (UHS). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 32839–32848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, A.S.; Kobos, P.H.; Borns, D.J. Geologic Storage of Hydrogen: Scaling up to Meet City Transportation Demands. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 15570–15582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou, A.; Bader, A.G.; Lanoix, J.C.; Nadau, L. Relevance and Costs of Large Scale Underground Hydrogen Storage in France. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 22987–23003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.B.; Alderson, J.E.A.; Kalyanam, K.M.; Lyle, A.B.; Phillips, L.A. Technical and Economic Assessment of Methods for the Storage of Large Quantities of Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1986, 11, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, S.H.; Groenenberg, R.; Koornneef, J.; Juez-Larré, J.; Shahi, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of Developing an Underground Hydrogen Storage Facility in Depleted Gas Field: A Dutch Case Study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 28824–28842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorre, J.; Ruoss, F.; Karjunen, H.; Schaffert, J.; Tynjälä, T. Cost Benefits of Optimizing Hydrogen Storage and Methanation Capacities for Power-to-Gas Plants in Dynamic Operation. Appl. Energy 2020, 257, 113967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, C.; Deane, P.; Yousefian, S.; Monaghan, R.F.D. The Hydrogen Storage Challenge: Does Storage Method and Size Affect the Cost and Operational Flexibility of Hydrogen Supply Chains? Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, R.K.; Papadias, D.D.; Peng, J.-K.; Roh, H.S. System Level Analysis of Hydrogen Storage Options. In Proceedings of the 2019 Annual Merit Review and Peer Evaluation Meeting, Crystal City, VA, USA, 29 April–1 May 2019; U.S.DOE Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ENTEC. The Role of Renewable H2 Import & Storage to Scale up the EU Deployment of Renewable H2; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- DNV. CO2QUALSTORE Guideline for Selection and Qualification of Sites and Projects for Geological Storage of CO2; Det Norske Veritas: Oslo fjord at Høvik, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hystories Project Hystories. Available online: https://hystories.eu/project-hystories/ (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Talukdar, M.; Blum, P.; Heinemann, N.; Miocic, J. Techno-Economic Analysis of Underground Hydrogen Storage in Europe. iScience 2024, 27, 108771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.; Simon, J. Hystories D.6.1-1—Assessment of the Regulatory Framework; IEA: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, H.; Kushwaha, O.S. Policy Implementation Roadmap, Diverse Perspectives, Challenges, Solutions Towards Low-Carbon Hydrogen Economy. Green Low-Carbon Econ. 2024, 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Delagated Regulation (EU) 2023/1184 of 10 February 2023 Supplementing Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Establishing a Union Methodology Setting out Detailed Rules for the Production of Renewable liquid and gaseous transport fuels of non-biological origin. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, 157, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Delagated Regulation (EU) 2023/1185 of 10 February 2023 Supplementing Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Establishing a Minimum Threshold for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Savings of Recycled Carbon Fuels and by specifying a methodology for assessing greenhouse gas emissions savings from renewable liquid and gaseous transport fuels of non-biological origin and from recycled carbon fuels. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, 157, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Koteras, A.; Chećko, J.; Urych, T.; Magdziarczyk, M.; Smolinski, A. An Assessment of the Formations and Structures Suitable for Safe CO2 Geological Storage in the Upper Silesia Coal Basin in Poland in the Context of the Regulation Relating to the CCS. Energies 2020, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliasz-Misiak, B.; Przybycin, A. Present and Future Status of the Underground Space Use in Poland. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliasz-Misiak, B.; Przybycin, A. The Perspectives and Barriers for the Implementation of CCS in Poland. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Shi, X.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, K.; Wei, X.; Bai, W.; Liu, X. Hydrogen Loss of Salt Cavern Hydrogen Storage. Renew. Energy 2023, 218, 119267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.J.; Johnson, T.L.; Keith, D.W. Regulating the Ultimate Sink: Managing the Risks of Geologic CO2 Storage. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 3476–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B. Towards Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Review of Barriers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.-t.; Gong, X.-l.; Guo, Y.-h.; Yang, Y.-s.; Dong, J. Regulatory Mechanism Design of GHG Emissions in the Electric Power Industry in China. Energy Policy 2019, 131, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Geological Aspects | Technology Aspects | Economic Aspects | Policies and Regulations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site Assessment | Capacity | Interactions | Infrastructure | Management | Monitoring | |||

| Aftab et al., 2022 [11] | ||||||||

| Amirthan and Perera, 2023 [51] | ||||||||

| Bade et al., 2024 [52] | ||||||||

| Bagchi et al., 2025 [53] | ||||||||

| Bai et al., 2014 [54] | ||||||||

| Diamantakis et al., 2024 [27] | ||||||||

| Du Z. et al., 2024 [55] | ||||||||

| Ekpotu et al., 2023 [28] | ||||||||

| Gianni et al., 2024 [56] | ||||||||

| Heinemman et al., 2021 [23] | ||||||||

| Hematpur et al., 2023 [13] | ||||||||

| Jafari Raad et al., 2022 [57] | ||||||||

| Kalam et al., 2023 [44] | ||||||||

| Khanjani et al., 2026 [58] | ||||||||

| Leng et al., 2025 [59] | ||||||||

| Ma N. et al., 2024 [60] | ||||||||

| Maury Fernandez et al., 2024 [29] | ||||||||

| Miocic et al. 2022 [30] | ||||||||

| Miocic et al., 2023 [42] | ||||||||

| Muhammed et al., 2022 [16] | ||||||||

| Mulky et al., 2024 [61] | ||||||||

| Mwakipunda et al., 2025 [62] | ||||||||

| Navaid et al., 2023 [17] | ||||||||

| Pan et al., 2021 [63] | ||||||||

| Raza et al., 2022 [24] | ||||||||

| Sekar et al., 2023 [33] | ||||||||

| Shadfar et al., 2025 [64] | ||||||||

| Taiwo et al., 2024 [65] | ||||||||

| Tarkowski 2019 [9] | ||||||||

| Tarkowski and Uliasz-Misiak, 2021 [40] | ||||||||

| Tarkowski et al., 2021 [19] | ||||||||

| Thiyagarajan et al., 2022 [20] | ||||||||

| Van Gessen et al., 2023 [45] | ||||||||

| Wang J. et l., 2023 [25] | ||||||||

| Zeng et al., 2023 [66] | ||||||||

| Zivar et al., 2021 [22] | ||||||||

| Aspect | Challenges | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| Site screening, selection, and characterisation |

|

|

| Hydrogen storage capacity |

|

|

| Hydrogen interactions with storage complex |

|

|

| Hydrogen storage infrastructure |

|

|

| Hydrogen storage management |

|

|

| Hydrogen storage monitoring |

|

|

| Economic aspects of UHS |

|

|

| Policies and regulations of UHS |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insights for Future Development. Energies 2025, 18, 5724. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215724

Tarkowski R, Uliasz-Misiak B. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insights for Future Development. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5724. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215724

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarkowski, Radosław, and Barbara Uliasz-Misiak. 2025. "Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insights for Future Development" Energies 18, no. 21: 5724. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215724

APA StyleTarkowski, R., & Uliasz-Misiak, B. (2025). Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insights for Future Development. Energies, 18(21), 5724. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215724