Abstract

Photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) solar collector technologies are considered a highly efficient solution for sustainable energy generation, capable of producing electricity and heat simultaneously. This paper reviews and discusses different aspects of PVT collectors, including fundamental principles, materials, diverse classifications, such as air-type and water-type, and different cooling mechanisms to boost their performance, such as nano-fluids, Phase Change Materials (PCMs), and Thermoelectric Generators (TEGs). At the system level, this paper analyses PVT technologies’ integration in buildings and industrial applications and gives a comprehensive market overview. The methodology focused on evaluating advancements in design, thermal management, and overall system efficiency based on existing literature published from 2010 to 2025. From the findings of various studies, water-based PVT systems provide electrical efficiencies ranging from 8% to 22% and thermal efficiencies between 30% and 70%, which are almost always higher than air-based alternatives. Innovations, including nanofluids, phase change materials, and hybrid topologies, have improved energy conversion and storage. Market data indicates growing adoption in Europe and Asia, stressing significant investments led by Sunmaxx, Abora Solar, Naked Energy, and DualSun. Nonetheless, obstacles to PVT arise regarding aspects such as cost, design complexity, lack of awareness, and economic incentives. According to the findings of this study, additional research is required to reduce the operational expenses of such systems, improve system integration, and build supportive policy frameworks. This paper offers guidance on PVT technologies and how they can be integrated into different setups based on current normativity and regulatory frameworks.

1. Introduction

Solar energy has been and is expected to remain a major contributor to the growth of renewable energy technologies, which have been propelled by the increasing urgency to reduce environmental damage brought on by the excessive usage of fossil fuels. Photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) systems are a notable development among them. PVT systems maximise energy yield and space efficiency by combining photovoltaic (PV) cells and solar thermal (ST) technologies to produce heat and electricity at the same time. This dual-purpose technology offers a promising way to fulfil growing energy demands while lowering greenhouse gas emissions, making it especially relevant in urban settings with limited space [1]. PVT systems address a significant issue with conventional solar PV systems: operational temperature increase and the dissipation of excess heat, which lowers PV cell performance and represents wasted energy. PVT systems increase overall energy efficiency by using this heat for thermal purposes while decreasing the cell temperature, making them perfect for various uses, such as space heating, hot water heating in homes, and heat pump integration. Despite PVT advantages, they face particular challenges, such as high investment costs, design complexity, and lack of awareness, ultimately resulting in PVT having a much smaller market presence than standalone PV or thermal systems. Recent advancements in materials, system designs, and cooling techniques address these issues, enhancing electrical and thermal performance. This study explores the evolution, applications, and technological advancements in PVT collectors and systems, focusing on their performance, application, struggles, and future potential in the global energy landscape. Through an extensive literature review, this paper will highlight the key drivers behind adopting PVT systems and the innovations that enhance their efficiency and cost-effectiveness. In addition, it presents the current market and outlook of PVT technologies worldwide and in Europe, highlighting large PVT projects commissioned by market leaders.

2. Fundamentals of PVT Systems

To clarify the core principles, the operation of a PVT system involves a heat transfer fluid (e.g., water, air, or a nanofluid) that circulates through an absorber component, cooling the PV cells and maintaining their electrical performance, which leads to higher overall energy conversion efficiency compared to separate PV and solar thermal collectors [1,2].

A conventional PV module converts only 6–22% of incident solar radiation into electricity, with the remaining dissipating as heat, significantly reducing the PV efficiency. In PVT collectors, a thermal absorber circulates water/air or nanofluids underneath the PV module [3]. The exposure to sunlight increases the temperature of the PV cells, decreasing electrical efficiency, while the thermal collector absorbs and transfers excess heat, preventing this reduction [4]. The operating temperature of the PV cells primarily governs electrical efficiency in PVT systems. Dubey et al. [3] provided a linear model for PV electrical efficiency, presented as Equation (1):

where is the instantaneous electrical efficiency of the PV module, is the rated electrical efficiency at a defined reference temperature ( typically 25 °C), and is the temperature coefficient of efficiency (typically around 0.004 K−1 for crystalline silicon modules). This term is the reason for the linear decrease in electrical efficiency as the cell temperature () rises above the reference temperature, primarily due to increased internal carrier recombination rates within the semiconductor material.

Equation (2) by Hosouli et al. [5], is used to characterise the useful heat gain per unit area of a PVT collector:

In this equation, represents the useful heat gain, is the gross collector area, is the optical efficiency (representing the fraction of incident solar radiation converted into useful heat at zero temperature difference), and is the hemispherical solar irradiance incident on the collector surface. The terms and quantify the thermal losses from the collector, where is the mean collector fluid temperature, is the ambient temperature, and are linear and quadratic heat loss coefficients, respectively. These coefficients are determined experimentally, often under steady-state or quasi-dynamic testing protocols defined by standards such as ISO 9806:2017 [6], which confirms consistent and comparable thermal performance data across different solar thermal technologies.

PVT systems are commonly classified by their heat transfer medium into four types which are: air-based, water-based, a combination of air/water-based, and nanofluid-based. Air-based PVT uses air as the medium to extract heat from the PV panels. They have thermal efficiencies between 20% and 70% and are simpler to implement but less effective in heat transfer compared to liquid-based systems [2,7].

Water-based PVT systems use water or a water-glycol mixture to prevent freezing, serving as the heat transfer medium. They can be more effective since water has a higher heat capacity, resulting in electrical efficiencies of 8–17% and thermal efficiencies of 30–70% [8].

Manssouri et al. [9] investigated a novel bi-fluid (air and water) PVT collector designed to cool the PV cells and enhance performance. By using a one-dimensional steady-state numerical model, the authors simulated the electrical and thermal performance of this system. The simulation results showed that the bi-fluid PVT collector increased the thermal energy transferred to the liquid side by 20% and the overall energy yield by 15.3% when compared to a water-based PVT collector.

Nanofluid-based PVT involves using nanofluids (liquids with nanoparticles) to improve thermal conductivity and enhance overall efficiency. For instance, one study found that in specific setups, using eco-friendly graphene nanoplatelet (GNP) nanofluids in tube designs improved electrical efficiency by up to 5.8% and thermal efficiency by 55.22% [10]. Nonetheless, the widespread implementation of nanofluid-enhanced heating systems in solar thermal technologies has been significantly constrained by issues related to environmental sustainability, operational practicalities, and increased economic costs.

The findings of Widyolar et al. [11] and Samykano [12] demonstrated that while PVT systems are efficient, they face challenges such as high costs, complexity in design, and, in some collectors, the need for advanced cooling techniques to prevent performance degradation. There are significant opportunities for further research in enhancing material properties, system integration with building structures, and innovative thermal management strategies using advanced fluids and materials.

The incorporation of PVT systems in sports centre infrastructures has demonstrated significant potential due to their capacity to meet constant thermal energy requirements. This continuous heat demand facilitates the operation of PVT collectors at low temperature levels (<60 °C), thereby optimising the thermodynamic efficiency of both heat and power generation. Such integration underscores the potential for enhanced performance metrics and energy efficiency in high-demand thermal environments, emphasising the importance of system design parameters tailored to sustained heat loads [13]. Moreover, as previously mentioned, PVT systems could have a greater decarbonisation potential in terms of avoided CO2 emissions per roof/facade area, depending on the displaced fuel.

PVT systems are highly versatile, finding applications in a range of settings from space heating and water heating to cooling, desalination, and greenhouse temperature control. Their design makes them particularly suitable for urban environments where space is limited, as they generate both electricity and thermal energy from a single installation, thus optimising land and rooftop use. PVT technologies are capable of superior specific energy output (kWh/m2) compared to stand-alone PV or ST systems.

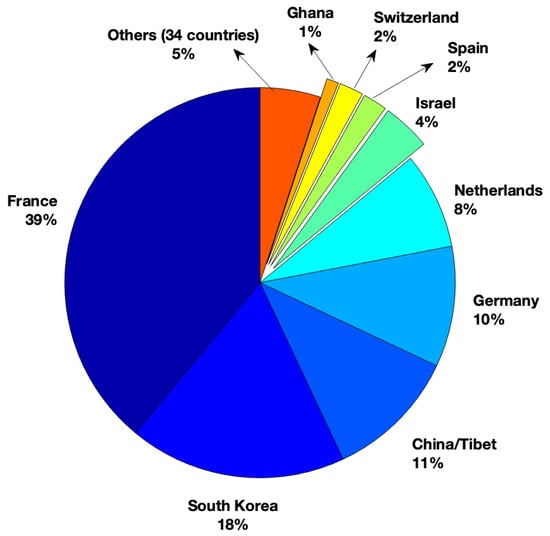

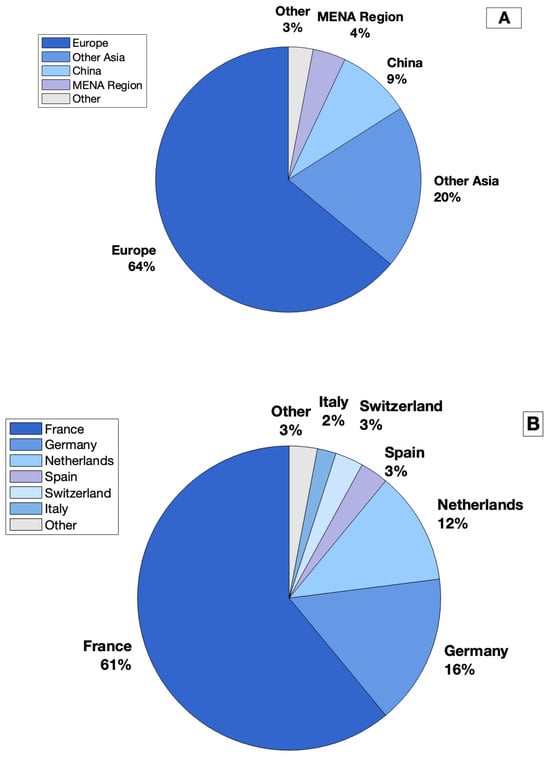

Figure 1 illustrates the global distribution of PVT installations in regions where renewable energy policies and incentives drive adoption [14].

Recent technological advancements are addressing some of these issues, with innovations such as the integration of thermoelectric generators (TEGs), which convert temperature differences into additional electrical energy. These developments promise to further improve the efficiency and sustainability of PVT systems. As the technology matures, it is expected to play a key role in meeting future energy needs, particularly in regions like the UK, where decarbonization of the heating sector is a critical priority [15].

Figure 1.

Global distribution of PVT systems in different countries at the end of 2023; the total is almost 1.6 million m2 [16].

Figure 1.

Global distribution of PVT systems in different countries at the end of 2023; the total is almost 1.6 million m2 [16].

3. Performance and Cooling Mechanisms

The performance of solar collectors is a critical parameter that determines their viability and competitiveness across different applications. Effective cell cooling mechanisms play a pivotal role in maintaining and sometimes increasing PV cell efficiency by mitigating thermalisation losses while simultaneously enhancing thermal energy recovery. The literature on PVT systems is extensive and can be broadly categorised into studies focusing on the PVT collector itself and those examining the integration of the collector into larger energy systems.

3.1. Collector-Level Advancements

Research in this field primarily focuses on enhancing the thermal and electrical performance of PVT collectors. This includes advancements in cooling mechanisms, absorber designs, and the use of novel materials and working fluids.

3.1.1. Cooling Mechanisms, Absorber Designs, and Working Fluids

Numerous studies have demonstrated that absorber geometry, flow configurations, and the use of advanced working fluids (such as nanofluids and PCMs) affect the efficiency of PVT collectors. Optimal designs, including bionic channel structures [17] and dual oscillating absorbers, have been identified as promising configurations for enhancing thermal and electrical performance.

Hermann et al. [18] analysed ST, PV, and PVT modules, focusing on three different absorber designs: serial, parallel, and bionic. Both experimental and numerical simulations were used to compare the energy and exergy efficiencies of these systems. The results showed that the bionic absorber outperforms the others in terms of solar-to-electrical efficiency and lower pressure losses. While the PVT system with bionic channels achieved higher electrical efficiency (up to 14.5%) compared to the others, its thermal efficiency was lower than that of the ST module due to structural differences like the air gap between the absorber and front glass.

Abdullah et al. [19] examined a new water-based PVT system featuring a specialised dual oscillating design for copper absorbers to improve both electrical and thermal performance. The results showed that increasing the flow rates of water from 2 to 6 litres per minute and sunlight intensity from 500 to 1000 W/m2 improved the system’s ability to generate electricity and heat, achieving a peak electrical efficiency of 11.97%, thermal efficiency of 58.43%, and total efficiency of 66.87%.

Tyagi et al. [20] examined how various geometric channel layouts, such as the channel shape and flow configurations on the backside of the modules, affect PVT system performance. The helical flow channel was identified as the most effective design because of its multiple bend sections, which enhanced heat transfer by disrupting the thermal boundary layer.

In PVT panels, the selection of the absorber’s channel configuration—serial, parallel, or bionic—significantly impacts thermal and electrical performance. Zhang et al. [21] showed that bionic absorber configurations offer a unique performance profile, achieving the lowest average effluent temperature of 44.1 °C combined with the least pressure loss compared to both serial and parallel configurations.

Building on recent advancements in PVT research, these studies have shown that absorber geometry and flow configuration play a crucial role in enhancing PVT system performance. Bionic and helical channel designs have demonstrated superior heat transfer characteristics, improved electrical efficiency, and reduced pressure losses compared to conventional serial or parallel layouts. Dual oscillating absorber designs also significantly improve combined electrical and thermal efficiencies under varying flow rates and irradiance conditions. Overall, optimised absorber geometries significantly contribute to improving the overall energy conversion efficiency of PVT collectors.

Gomes [22] investigated a C-PVT design where strings of series-connected solar cells are encapsulated with silicone in an aluminium receiver, inside of which the heat transfer fluid flows, and presents an evaluation on structural integrity and performance of the cells, after reaching temperatures of 220 °C during eight rounds. This study built eight test receivers where the following properties were varied: Size of the PV cells, type of silicone used to encapsulate the cells, existence of a strain relief between the cells, size of the gap between cells, and type of cell soldering (line or point) and concludes on several aspects such as the protective function of the different encapsulating silicons. Electroluminescence testing also shows that under thermal stress, larger cells are more prone to develop microcracks, and existing microcracks tend to grow in size relatively fast.

Ramdani et al. [23] discussed an innovative water-based PV collector designed to enhance solar energy collection efficiency. The system’s key feature was a water layer over the PV cells that cools them and filters solar radiation, converting infrared to thermal energy while allowing visible light to go towards the PV cells and generate electricity. The results showed that this novel PVT system outperforms previous designs in both energy and exergy efficiencies, with an optimal cooling channel height of 3.61 cm.

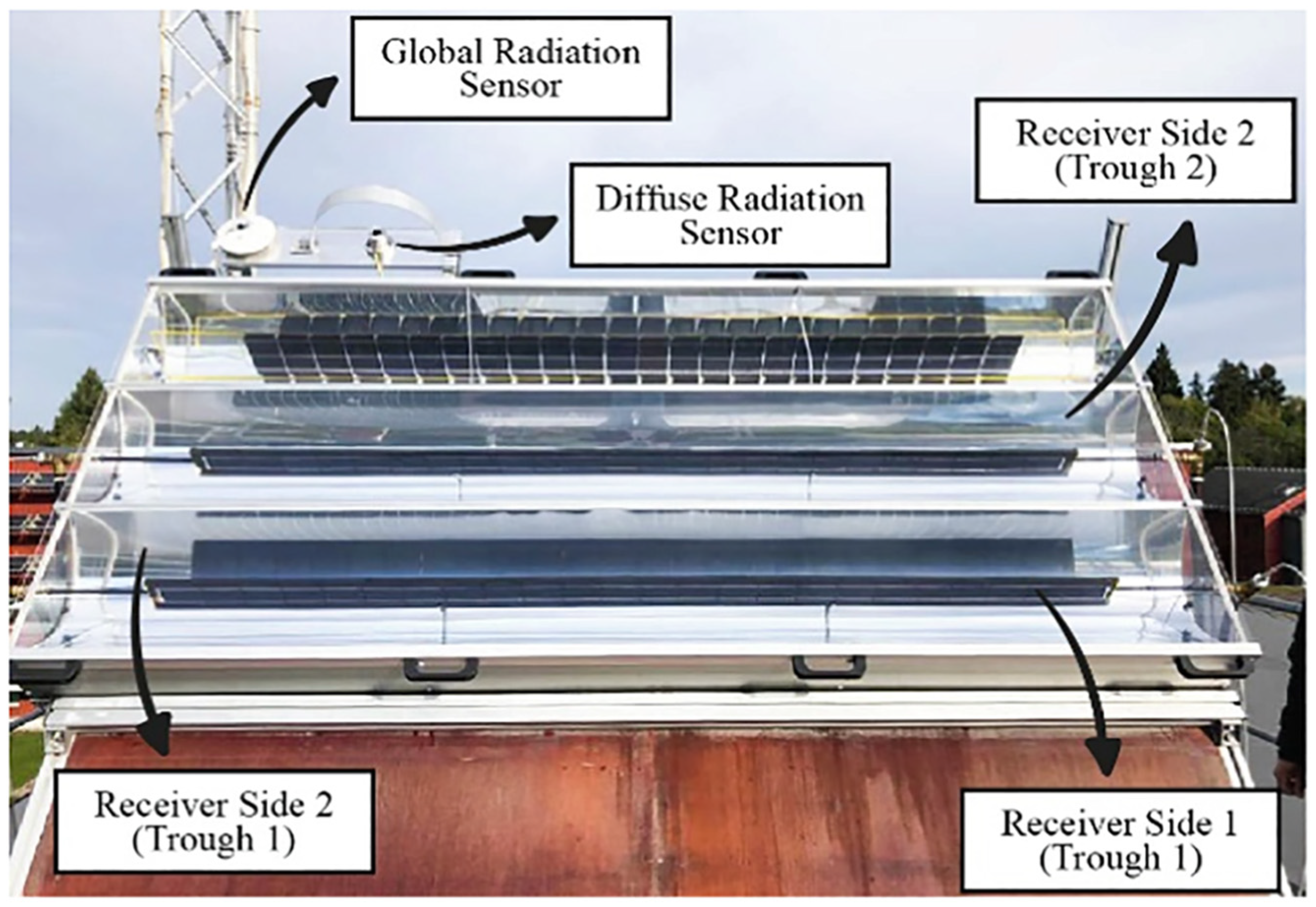

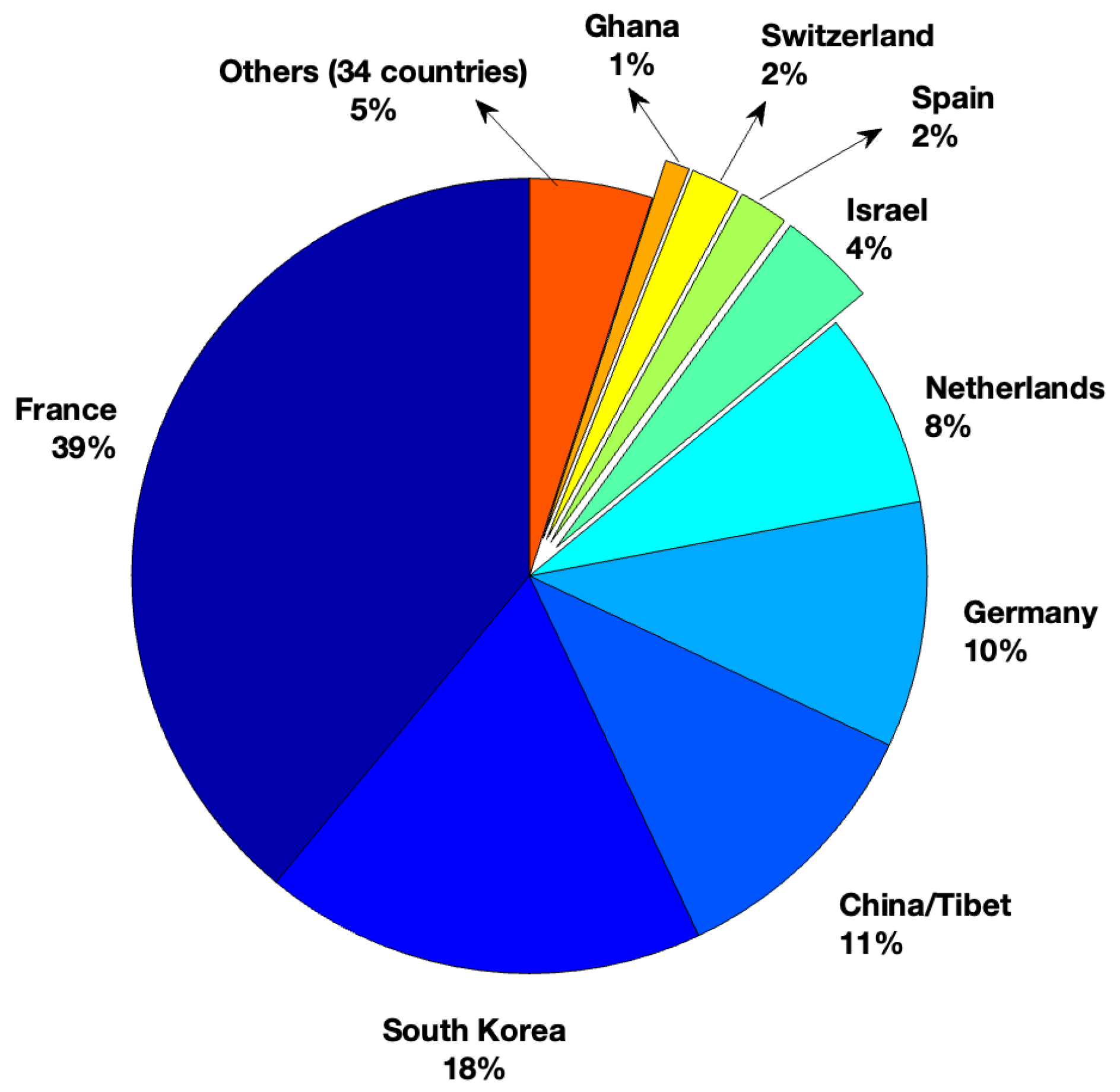

Cabral et al. [24] presented an experimental investigation on a low-concentration PVT solar collector based on a parabolic reflector geometry with a wedge PVT receiver (Figure 2). Electrical and thermal outdoor experiments were carried out, and several parameters were presented, such as the daily instantaneous electrical and thermal performance efficiency diagram. Additionally, an electrical Incidence Angle Modifier (IAM); for both transversal and longitudinal directions was reported. The study estimated an overall heat loss coefficient of 4.1 W/m2 °C and a thermal optical and electrical efficiency of 59% and 8%, respectively. The study shows that the placement of the wedge receiver is susceptible to high incidence angles, as the electrical transversal Incidence Angle Modifier factor decreases significantly after reaching its electrical peak efficiency at 10 °.

Figure 2.

Absorber Solar collector test apparatus for the transversal electrical IAM testing procedure with both pyranometers for global and diffuse radiation measurement [24].

A PVT system with direct water-PV contact developed by Rahaei et al. [25] demonstrated strong thermal and electrical performance for district heating and power generation applications. The system achieved a maximum thermal efficiency of 58% and a daily average efficiency of 49%, while electrical efficiency improved by 15–21.5% compared to conventional PV modules. The study found that higher water flow rates enhanced system performance due to better cooling, but additional investigation is needed to determine the optimal flow rates that maximise efficiency. Furthermore, research is required to assess the economic feasibility and payback durations for large-scale implementation of such systems.

Chaouch et al. [26] introduced a dynamic model of a roll-bond PVT solar collector for North African climates, which demonstrated system performance. The new dynamic roll-bond PVT model offered a higher annual exergy of 13.84% and achieved average annual thermal and electrical efficiencies of 33.7% and 12.27%, respectively, showing better performance than standalone PV and ST systems. However, the development of precise dynamic models for roll-bond systems remains limited. The performance enhancement of absorber plate heat transfer requires better solutions, and TRNSYS needs updated tools to accurately evaluate roll-bond PVT modules.

These studies on PVT collector development have focused on enhancing both structural integrity and energy performance through innovative designs and materials. Studies have explored encapsulation methods, spectral filtering layers, and direct water-PV contact to improve cooling efficiency and overall conversion performance. Experimental and modelling investigations into low-concentration and roll-bond configurations have achieved notable gains in thermal and electrical efficiency. However, gaps remain in optimising system design for large-scale deployment, particularly regarding economic feasibility, long-term durability, and accurate dynamic modelling tools to predict real-world performance under varying operating conditions.

Hissouf et al. [27] examined the PVT performance of two different fluids, pure water and an ethylene glycol-water mixture, with three types of fluid channel geometries (circular, half tube, and square tube). Using pure water as the working fluid instead of the ethylene glycol-water mixture resulted in a thermal efficiency increase of 4.5% and a 1.85% rise in electrical efficiency, due to its higher heat capacity and lower viscosity.

Sopian et al. [28] presented a comparative analysis of four different PVT systems incorporating various energy storage materials, evaluated for energy, exergy, and efficiency in the tropical climate of Malaysia. The nanofluid-PCM-based PVT exhibited the highest performance, achieving a total efficiency of 85.7%, thermal efficiency of 72%, and electrical efficiency of 13.7%.

Yazdanifard et al. [29] investigated the use of a nanofluid and nano-enhanced phase change material (NEPCM)-based spectral splitting PVT system. The study evaluated five possible configurations of a layered filter design using silver (Ag) and gold (Au) nanoparticles suspended in glycerol and NEPCM. The parametric study found that a nanofluid channel placed above the NEPCM achieves the best performance in energy storage, energy conversion, and exergy efficiency, with optimal nanoparticle volume fractions and flow rates identified for maximising system performance.

Tembhare et al. [30] debated the application of PVT, which is mostly domestic hot water, space heating, industrial processes, and even desalination, offering improved efficiency by utilising both electrical and thermal outputs. Nanofluids increase the system’s energy efficiency by improving heat absorption and reducing overheating due to their superior heat transfer capabilities, ensuring optimal operation of photovoltaic panels.

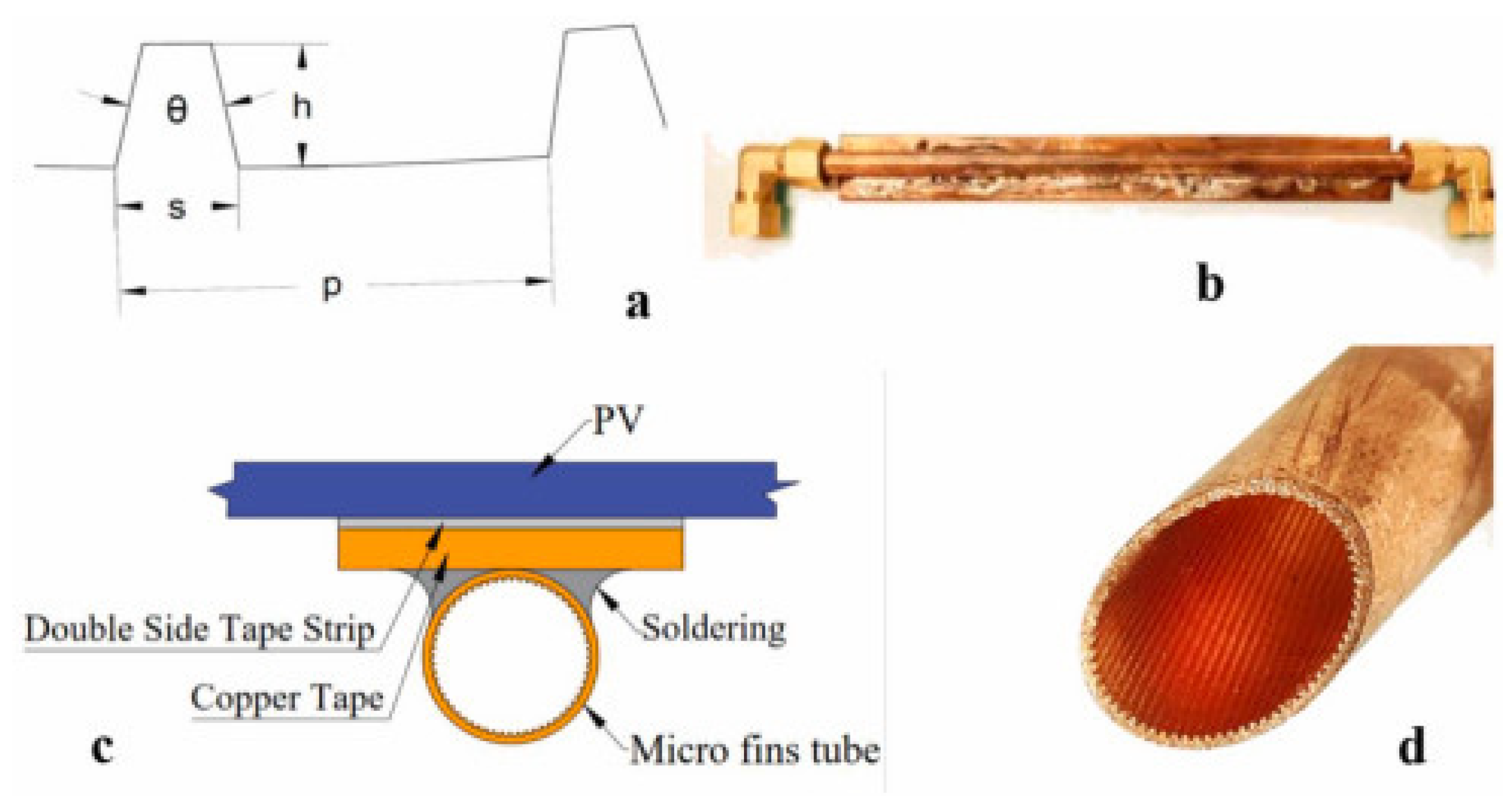

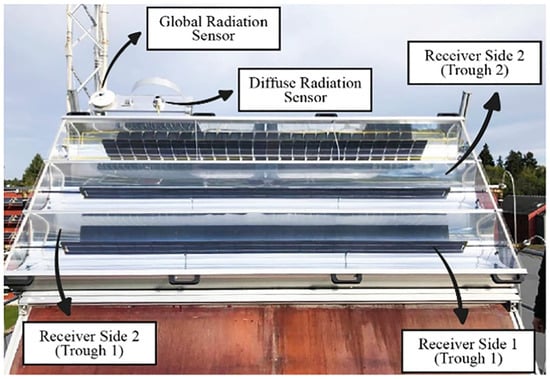

Bassam et al. [31] analysed a PVT system augmented with nano-phase change material (nano-PCM) and micro-fin tubes employing nanofluids using a cooling nanofluid circulation system with micro-fin tubes encased with nano-PCM. The results demonstrated that silicon carbide (SiC) nanoparticles increased the fluids’ thermal conductivity, resulting in higher heat transfer efficiency. When micro-fins, nanofluids, and nano-PCM were combined in the PVT configuration, the maximum thermal efficiency was 77.5%, while the highest electrical efficiency was 9.6%. Figure 3 illustrates the micro-fin tube configuration used in a PVT system, showing how enhanced surface geometry and internal flow structures contribute to improved thermal conductivity and overall system efficiency.

Figure 3.

(a) Micro-fine details, (b) pipe sample, (c) cross-section pipe, (d) micro-fins view. Reproduced from Bassam et al. [31], Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 2023, under CC BY license.

The studies highlighted above have focused on enhancing PVT performance through innovative thermal management strategies. The use of high-performance fluids and nano-enhanced phase change materials has been shown to improve heat transfer, energy storage, and overall system efficiency. Incorporating advanced geometries, such as micro-fin tubes, in combination with these materials further optimises thermal conductivity and cooling effectiveness. These studies indicate significant potential for performance gains; however, further investigation is needed on optimal nanoparticle concentrations, flow configurations, and long-term operational stability to enable reliable and scalable deployment of these systems.

3.1.2. High-Concentration and Asymmetric PVT Collectors

Several studies have focused on high-efficiency systems, such as high-concentration photovoltaic-thermal (HCPVT) and double MaReCo photovoltaic-thermal (DM-CPVT), which use solar concentration and optimised geometries to maximise energy yield, despite inherent complexities and limitations. Note that these collectors utilise reflective surfaces to focus solar radiation onto a smaller receiver area. This approach enables CPVT systems to achieve higher thermal energy outputs compared to traditional flat-plate PVT collectors, particularly at elevated operating temperatures [24].

Moreno et al. [32] presented a HCPVT module that offers higher efficiency than traditional PVT systems by using concentrated solar power. In Almería (Spain) and Lancaster (USA), HCPVT produced up to 18.6% more electricity and 55% more thermal energy than the conventional PVT system, demonstrating their efficiency for urban environments. However, the necessity for a two-axis tracking system remained a challenge for practical building integration. Figure 4 presents an HCPVT module with both passive and active cooling systems, demonstrating the structural integration of optical and thermal components designed to enhance energy conversion efficiency.

Figure 4.

(a) Photograph of the CPV module; (b) Original passive cooling system and designed active cooling system (updated version). The insulation layer atop of the cell has been drawn transparent to distinguish the secondary optical element, the cell, the cell holder and the plate. Reproduced from Moreno et al. [32] under CC BY license.

Hosouli et al. [5] discussed the design and development of the DM-CPVT solar collector. Outdoor tests were conducted in Sweden and Greece in 2020, with results showing high annual energy outputs due to the design’s ability to minimise shading and maximise thermal and electrical performance. This configuration has been suggested for PVT systems located at higher latitudes.

3.1.3. Modelling Approaches for Performance Prediction

Ahmadi et al. [33] investigated the use of hybrid machine learning models to predict the thermal performance of a PVT solar collector. Various models, such as artificial neural networks (ANN), least squares support vector machines (LSSVM), and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS), were developed to predict electrical efficiency based on key parameters like inlet temperature, flow rate, solar radiation, and sun heat.

3.2. System-Level Integration

This section assesses studies focused on the integration of PVT collectors with other technologies to enhance system efficiency and adaptability across diverse climatic conditions and application scenarios. Several investigations explore hybrid systems incorporating phase PCM, ST collectors, TEGs, and energy storage units to optimise thermal regulation and energy output. These integrative approaches highlight the versatility of PVT technology and its growing role in achieving sustainable energy goals, although challenges remain subjects of ongoing research.

3.2.1. Hybrid System and Integration with Other Technologies

Findings on PVT systems, which are combined with other energy technologies, such as ST collectors, heat pumps, and desalination systems, are discussed in recent studies. Integration with phase change materials (PCM) helps control temperature, further optimising system performance [34]. Based on a study in Malaysian weather conditions, PV performance was increased by integrating a PCM. While the PVT’s electrical and thermal efficiency were found to be 14.57% and 75.29%, respectively, the maximum electrical and thermal efficiency for PVT-PCM was measured at 15.32% and 86.19%, respectively [35].

Ma et al. [36] introduced a novel system, called PVT-ST, which uses the PVT module to preheat water, further heat it by the ST collector, and provides high-temperature water for household or industrial use. Experimental validation showed that the PVT-ST system offers satisfactory thermal and electrical performance by producing 298.50 kWh of electricity and 2096.51 kWh of thermal energy annually in Shanghai. The key is maintaining the temperature of the PVT as low as possible and further upgrading the outlet temperature with solar thermal collectors.

Kazemian et al. [37] presented a novel PVT integrated with a solar thermal collector enhancer (PVT-STE), designed to overcome limitations of conventional PVT and standalone solar thermal systems, which partially cover its absorber plate with photovoltaic cells and optimise the ratio of photothermal energy conversion using a 3-dimensional transient model. Results showed that the PVT-STE system achieved significantly higher thermal power and exergy compared to traditional PVT units, with improvements of up to 48.3% in thermal power and 31.24% in overall power.

Kazemian et al. [38] discussed a PVT system that combines PCMs and a PVT-STE for effective thermal storage and energy production. Results showed that the PVT-STE system stored around double the thermal power and achieved up to 5 times higher thermal exergy compared to standalone PVT systems.

Li et al. [39] investigated the integration of a PVT module with an ST collector connected in series, aimed at producing both electricity and high-temperature thermal energy using a two-dimensional transient model, which was developed to analyse four configurations. The findings revealed that the system’s superior energy and exergy performance, with case 1 (glazed PVT and glazed ST), achieved the highest overall efficiency at 41.51% energy efficiency and 17.63% exergy efficiency.

Ghazy et al. [40] investigated a hybrid system that combines a PVT collector with an adsorption desalination system (ADS). The PVT collector produces electricity and thermal energy, improving its performance through cooling by chilled water produced during the ADS desalination process. This cooling increases the electrical efficiency of the PV cells, while the thermal energy from the PVT collector enhances the desalination process. The system demonstrated notable performance improvements, including a 17.5% increase in electrical efficiency and a 19.69% rise in specific water production.

Ali et al. [41] explored the integration of a PVT system with a solar pond to enhance overall energy efficiency. The innovative system involved cooling the PV panels through heat exchangers and transferring the excess heat to the lower layer of a solar pond, where thermal energy is stored. An experimental setup in Kirkuk, Iraq, evaluated the system over five months. Results indicated that the highest total system efficiency was 37.67%, with peak thermal and electrical efficiencies recorded in September and December, respectively.

Emmi et al. [42] investigated a solar-assisted ground source heat pump (SAGSHP) system for residential buildings, comparing ST and PVT panels. Results indicate that PVT panels improve the overall efficiency of the heat pump, particularly in warmer climates, and integration of renewable technologies can optimise energy performance.

Wang et al. [43] compared air source heat pump (ASHP) systems that use three different types of solar energy: photovoltaic (PV), hybrid PVT, and solar thermal. According to the comparison, PV-ASHP systems exhibit the best techno-economic performance, with a moderate cost, payback period, and an average coefficient of performance (COP) of 3.75.

Wen et al. [44] found that a PVT-ST system with PCM and TEG improves energy output, achieving 65.22% thermal and 10.65% electrical efficiency using a 1.1 m2 Fresnel lens. It delivers 321.53 kJ of extra energy via TEG and raises water tank temperature by 5 °C compared to a PVT-PVT setup. Optimal PV output (1.653 × 103 kJ) occurs at 800 W/m2, with TEG output increasing by 6.69 × 102 kJ from 100 to 900 W/m2. At 2.4 × 10−3 kg/s flow, the system reaches 97.17% overall and 20.65% exergy efficiency. Further study is needed for experimental validation, night antifreeze behaviour, and cost reduction.

Madurai Elavarasan et al. [45] provided an extensive review of different techniques to improve the efficiency of PV panels, including active, passive, and hybrid cooling methods. Researchers identified hybrid systems as a promising solution for maximising overall energy efficiency, as they capture both electrical and thermal energy.

Zeng et al. [46] optimised a combined cooling, heating, and power (CCHP) system coupled with ground source heat pump, photovoltaic, and solar thermal technologies. The optimal load ratio for the thermal demand strategy is 0.2, yielding a 33.33% comprehensive performance improvement, while the electric demand strategy performs best at a 0.4 load ratio, achieving a 39.52% improvement.

Monjezi et al. [47] report a new off-grid solar-powered reverse osmosis desalination system coupled with a PVT cooling system. Although the system shows promise in producing freshwater continuously with improved energy efficiency, further research is required to address the management or reduction in concentrate discharge, which is still a significant environmental challenge. Further, the scalability of the suggested system for use in bigger solar desalination plants is not assessed, and an aspect of understanding its applicability at a broader scale is left behind.

3.2.2. Evaluating PVT System Efficiency Across Different Climates

The performance of PVT systems has been evaluated in a variety of global locations, with numerous studies focusing on hot climates where cooling PV modules is most critical. In Malaysia’s tropical environment, research has explored advanced designs; for instance, Sopian et al. [28] tested a PVT system using nanofluids and nano-PCM, achieving a thermal efficiency of 72% and a combined efficiency of 85.7%. Also in Malaysia, another study by [31] reporting a thermal efficiency of 77.5%, while Abdullah et al. [19] developed a dual oscillating absorber that reached a total efficiency of 66.87%.

Kuefouet Alexis et al. [48] evaluated the electrical and thermal performance of a hybrid PVT water solar collector in Cameroon, using different solar module brands. The study showed significant electrical energy gains (ranging from 11.1% to 12.3%) and thermal output (up to 12 litres of hot water at temperatures over 41 °C) compared to conventional solar systems. This dual capability makes PVT systems particularly suitable for areas where both electricity and hot water are in demand. Abdul-Ganiyu et al. [49] compared the performance of a PVT module to that of a traditional PV system in Ghana’s hot, muggy tropical climate. Results showed that while the PV produced 194.79 kWh/m2 annually, the PVT module generated 149.92 kWh/m2 of electricity and 1087.79 kWh/m2 of heat. The PVT had a lower electrical performance ratio (51.6%) compared to the PV (79.2%), but achieved a much higher combined efficiency of 56.1%.

Research in the hot, arid climates of the Middle East has also shown promising results. Kazem et al. [50] explored the performance of a new PVT system with a hybrid collector to address non-uniform heat distribution. The hybrid collector achieved an electrical efficiency of 12.7% and a thermal efficiency of 60.7%, which shows that such systems can be effectively applied in regions with high solar irradiance, like Oman, and the findings are also applicable to the UK.

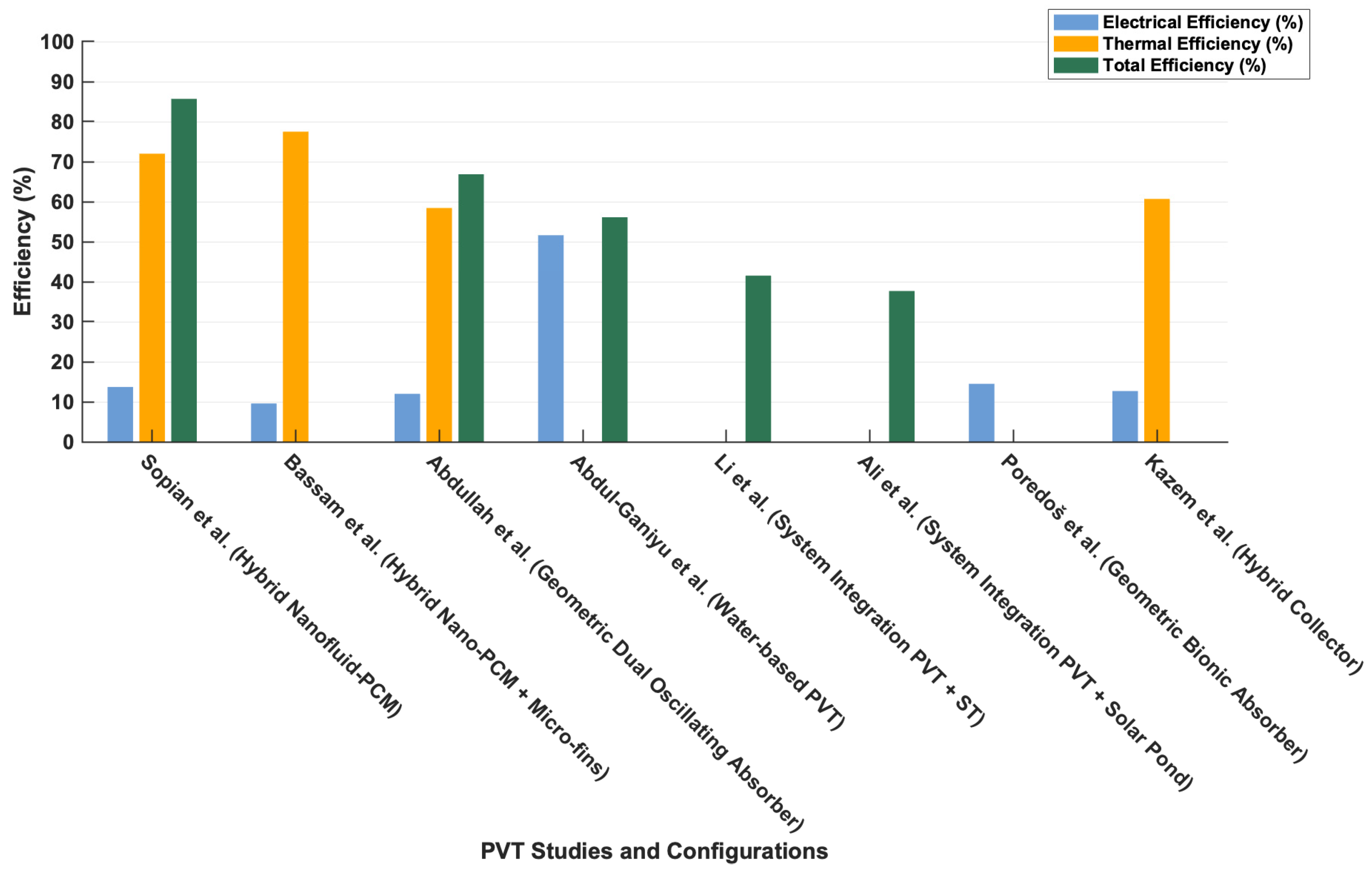

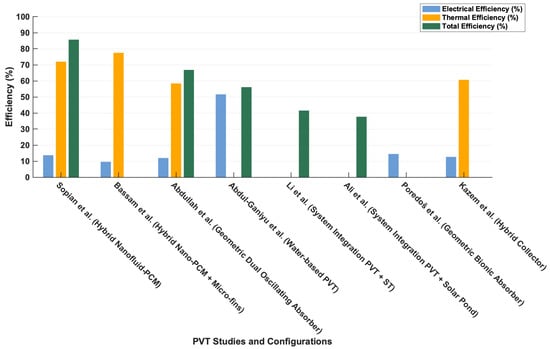

Figure 5 and Table 1 illustrate the electrical, thermal, and overall efficiency percentages reported in various PVT system research papers referenced in this section.

Figure 5.

Comparative comparison of electrical, thermal, and overall efficiency of diverse PVT system configurations from studies in Section 3 [2,17,19,31,39,41,49,50].

Table 1.

Summary of Part 3: Performance and Cooling Mechanisms.

Current research in PVT technology shows a concerted effort to enhance system performance through a two-divided approach: advancements at the collector level and strategic integration at the system level. Collector-level innovations are primarily focused on improving thermal management to boost both electrical and thermal efficiency. Key developments include the optimisation of absorber geometries, with designs such as bionic and helical channels showing promise in enhancing heat transfer, alongside the application of advanced working fluids like nanofluids and PCMs to maximise energy recovery. Concurrently, system-level research has emphasised the integration of PVT modules into hybrid configurations with technologies like ST collectors, heat pumps, and desalination units. This trend seeks to maximise the utility of the collected energy by cascading it through multiple processes, thereby increasing the overall resource efficiency of a single installation area.

Despite these advancements, the field faces significant challenges that slow down valid comparative analysis and widespread commercial adoption. Perhaps the most critical issue is the lack of a standardised methodology for reporting overall system performance. The common practice of summing electrical efficiency and thermal efficiency is fundamentally imperfect, as it incorrectly equates high-grade electrical energy with low-grade thermal energy. While the summation of electrical and thermal correctly accounts for the total energy captured under the First Law of Thermodynamics, it fundamentally violates the principles of the Second Law by ignoring the concept of energy quality, or exergy. The Second Law dictates that the potential of an energy stream to perform useful work is not solely dependent on its magnitude but on its form. Electrical energy is a form of pure work with an exergy content nearly equal to its energy content. In contrast, the exergy of the thermal energy produced by a PVT system is significantly lower than its energy content, as its ability to be converted into work is thermodynamically constrained by the Carnot factor. For typical low-temperature outputs from PVT systems, this factor is very small. Therefore, equating a unit of high-exergy electricity with a unit of low-exergy heat is thermodynamically inconsistent. This practice results in a misleadingly inflated metric that masks the true useful output of the system and is an inappropriate basis for rigorous technical comparison or optimisation. This inconsistency impacts direct and meaningful comparisons between different technologies and studies. Furthermore, a significant portion of the literature demonstrates high technical efficiency without a corresponding economic analysis. There remains a substantial gap in understanding the long-term financial viability, payback periods, and scalability of these complex systems, which is a critical barrier to moving from laboratory-scale success to market-ready products. The long-term durability of novel components, such as the stability of nanofluids and the cyclic degradation of PCMs, also remains under-investigated. Finally, the development of precise simulation tools continues to lag behind hardware innovation, with existing platforms often lacking the capability to accurately model novel designs like roll-bond collectors.

The trajectory of future research and development is expected to directly address these gaps. A crucial step will be the widespread adoption of exergy analysis as a standard performance metric. By accounting for the quality of energy, exergy provides a thermodynamically sound basis for comparing the true work potential of different systems. The focus of materials science research is anticipated to shift from solely demonstrating efficiency gains to make sure that the long-term stability, reliability, and cost-effectiveness of nanofluids and PCMs. To manage the increasing complexity of hybrid systems, the development of intelligent control systems, using AI and machine learning, will be essential for optimising real-time energy dispatch based on dynamic conditions. Ultimately, as these methodological and technological challenges are resolved, the application scope for PVT technology is expected to expand into more demanding sectors, including providing low-to-medium temperature industrial process heat, contributing to district energy networks, and driving solar-powered cooling and desalination processes.

4. Applications and Market Trends

Aside from targeting specific advances to push the conversion efficiency boundaries of PVT collectors and systems, there have been studies aimed at understanding their applications in different areas and processes. PVT integration and interaction with other subsystems such as heat pumps, thermal storage-ranging from conventional water-based systems to borehole thermal storage—smart control systems, and other conventional solar technologies like PV, is an interesting area that has been studied worldwide. Researchers seek to understand their energy generation capacity, decarbonization potential, and competitiveness compared to other technologies. Additionally, their application, collector selection, and integration scheme are strongly influenced by geographical considerations such as available solar resources, energy (heat and electricity) demand profiles, local availability of PVT technologies, and installation resources.

This section aims to review and analyse different works found in the literature that have approached such areas and have contributed to understanding the potential and limitations of PVT collectors and systems, focusing on applications in buildings and industry.

4.1. PVT in Buildings and Industry

4.1.1. PVT in Buildings

PVT systems offer a sustainable solution for meeting the growing energy demands of buildings by simultaneously generating electricity and useful heat from a single solar collector. Unlike conventional PV panels, PVT systems enhance overall energy efficiency by utilising the heat that would otherwise be wasted. This makes them ideal for space-constrained building environments where both electrical and thermal energy are needed, such as for lighting, appliances, water heating, and space conditioning. Their integration into building designs supports the development of energy-efficient and low-carbon structures, contributing to the goals of green building standards and nearly zero-energy buildings (nZEBs).

Joo et al. [51] conducted a PVT system experiment via laboratory and extended field trials on a residential rooftop in South Korea, demonstrating its efficient performance and overheating-prevention safety. The work of thermal actuators on seasonal efficiency variation and the coalescence with heat pump systems calls for additional studies. However, the study did not take into account the module’s life under the changing climatic conditions, and at the same time, they were unaware of the optimisation strategies that were designed for various roof shapes and installation sizes.

Behzadi et al. [52] modelled a PVT system using TRNSYS to evaluate a smart building energy solution, which also included a heat storage tank and grid interaction without batteries. The system performance under actual weather variability and usage patterns has to be validated in a long-term field by further research. The investigation, however, has not made an effort to explore architectural integration issues in different building typologies as well as real-time control strategies and the possibility of scaling up the study to larger building clusters.

Braun et al. [53] did a simulation-based study to see if hybrid PVT systems with reversible heat pumps could work for trigeneration in office buildings in different climate zones. They showed that these systems could theoretically save energy and money, but no one has tested them in the real world yet. More research is needed to find out how reliable the system is, how its performance changes with the seasons, and how to control it in real-world conditions, especially in hot and dry areas.

Polito et al. [54] tested a thermally coupled hybrid photovoltaic-thermal window (PVTW) that can make electricity and hot water for homes in cities. The study shows that spectral-splitting PV materials have good energy outputs and can be easily integrated into existing systems. However, it also shows that more research is needed on their long-term durability and cost-performance optimisation. We still do not know enough about how these systems work in the real world, especially when the sun is not shining as much and the sky changes a lot. More research is needed.

Elaouzy et al. [55] give strong evidence that building-integrated PVT systems work better in a variety of Moroccan climates. The work is all based on simulations and has not been tested in real-world conditions, even though the results look good, with low carbon payback periods (0.59–0.84 years) and low LCOE (0.027–0.039 $/kWh). The analysis also does not look at different types of liquid-based PVT technologies (like flat-plate vs. glazed/un-glazed) or at optimising components like the absorber material, flow rate, or insulation. Future research should focus on testing PVT integration in hot, dry areas, improving the thermal–electrical coupling, and using new cost and degradation models to look at the system’s performance over its entire life cycle.

Ma et al. [36] came up with and tested a hybrid PVT-ST system that works well for making electricity and high-quality heat for homes. This study is mostly about steady-state performance in a single climate (Shanghai), but it does show that primary energy saving efficiency is much better than in standalone systems. More research is needed to look into how dynamic performance works in changing conditions, how well real-time control strategies work, and how possible they are in different climates, especially colder ones, where there is more demand for heat.

A PVT-based solar CCHP system was theoretically analysed by Herrando et al. [56] for a university campus in Bari, showing its suitability for urban building applications with limited roof space. The system demonstrated significant potential for CO2 reduction and multi-energy supply. However, further research is required on long-term system stability under real operating conditions and fluctuating demand. The study did not perform experimental validation nor assess seasonal variations in energy balance. Additionally, lifecycle environmental impacts and advanced cost-reduction strategies for the hybrid setup were not investigated.

A combined smart energy system based on PVT, ejector cooling, and micro-gas turbine technologies was simulated under the climatic conditions of Tehran by Ranjbar Golafshani et al. [57]. The system showed significant technoeconomic potential without battery dependency and obtained significant exergy efficiency enhancements with optimisation. Nevertheless, experimental verification of system dynamics and reduction in high exergy destruction in the PVT units are needed through additional studies. Long-term operational stability and load fluctuations in real-time were not evaluated in the study, although their influence by seasonal variation and complete environmental impact by lifecycle analysis is still unknown.

A comprehensive summary of PVT applications in buildings is provided in Table 2, which also includes information on collector types, operating temperatures, use cases, and geographic contexts. It highlights important research gaps related to flexibility, affordability, system efficiency, and stability over time. It also presents system performance results, such as thermal and electrical outputs.

Table 2.

Summary of PVT system applications and research gaps in buildings and specific sectors.

PVT systems in buildings are among the most widely studied applications that different researchers have explored over the last decade. Despite this field being extensively investigated in the literature, there is a lack of validation and experimental evidence of the performance of such systems in real-life scenarios. Although the deployment and adoption of PVT technologies have gained momentum in recent years, as shown in Section 4.3, the installed systems have not been shared or made their historical data available to allow researchers and technology developers to assess their performance.

Integrating various PVT technologies with other renewable energy sources (RES), such as heat pumps, thermal energy storage systems, and advanced control mechanisms, constitutes a critical area of research focused on evaluating the performance and efficiency of hybrid solar energy systems. Flexibility emerges as a fundamental attribute in the development of next-generation energy systems, particularly in the context of building applications where energy demand profiles are increasingly dynamic and responsive to electrification trends. Hybrid systems capable of simultaneously generating heat, electricity, and cooling offer significant advantages in terms of operational versatility and system resilience. Such multi-output renewable configurations are particularly attractive when their integration into urban energy infrastructures is optimised to minimise disruption and enhance stability. The role of sophisticated control strategies is thus pivotal in managing the complex interactions among these components, ensuring optimal performance and resilience of integrated energy systems in urban environments.

4.1.2. PVT in Industry

PVT technologies offer cost-effective solutions compared to other solar options. In industrial contexts, the required outlet temperatures may exceed 60 °C, which is higher than those typically found in building systems. In industrial settings, where space is less constrained, the need for integrated solutions is reduced, favouring specialised technologies. This section examines the potential of PVT in industry, supported by case studies, and discusses key technical and economic barriers to wider adoption. Depending on the application, industrial setups may require much more robust collector designs to withstand harsh environments with heavy and complex dust particles to remove.

Bacha et al. [58] designed a PVT-RO desalination system with a cooling and preheating mechanism to evaluate its operational effectiveness and financial feasibility. Further research is required to properly tackle the major issues of extreme water shortage and current energy shortages in MENA, which represents the key area for technology application. The study, however, did not analyse the major reduction in renewable energy production that occurs because of climate variability, particularly in desert areas. The research gaps demonstrate a requirement for enhanced regional evaluation of system endurance and connection strategies for desalination systems utilising renewable energy.

Acosta-Pazmiño et al. [59] studied the hybridisation of a parabolic trough collectors-based solar thermal plant to a low concentrating PVT (LCPVT) system to produce industrial heat and electricity. Although the system demonstrated solid performance in comparison with the solar thermal system, the economic viability was based on a fractional cost of the hybrid absorber relative to the PVT collector’s final costs. Thus, the financial assessment has a strong limitation given the low technology readiness level of the studied collector.

Gorjian et al. [60] assessed how PVT technologies operate in agricultural greenhouses while pointing out their potential advantages. The study presents that the high initial cost of spectrum splitters combined with their dependence on parabolic concentrator costs above 75% restricts their economic viability. The study found that utility prices strongly influence economic performance and that the payback durations span between 13 and 25 years. The expansion of spectral splitting technology requires additional research to minimise expenses and enhance its efficiency for wider adoption.

Herrando et al. [61] conducted an analysis of hybrid PVT systems within the food processing industry to demonstrate their capability for both thermal and electrical integration. The current system framework focuses on replacing fossil fuels rather than substituting grid-supplied electricity. The utilisation of PVT systems for grid electricity replacement demands further optimisation to achieve better performance in industrial processes with high energy needs.

Gu et al. [62] developed theoretical research about a new CPC solar thermal collector which shows potential for methanol reforming. However, the research contains no experimental tests, and further research is required to investigate performance variations across different operating parameters. The practical implementation of the system remains restricted since vacuum component durability together with scalability for larger applications, has not been studied.

A PVT system was tested by Murali et al. [63] at an Italian livestock farm, demonstrating its feasibility for agricultural applications. The study showcased the potential of PVT systems to be integrated with other RES such as heat pumps, to meet the electrical and thermal energy demand in livestock applications. Nevertheless, the experiments were only carried out during the summer. Further research is necessary to assess long-term performance and to evaluate seasonal heat production, storage, and extraction efficiency. Moreover, this work did not address its scalability for implementation across multiple agricultural operations.

Hosouli et al. [64] conducted a numerical evaluation of a PVT system used in German dairy farming. Further research is required to provide detailed information about the energy performance of the present heat recovery system HRS through its temperature and energy output analysis. The CPVT system employed still holds opportunities to enhance its total performance capabilities. Moreover, experimental data is needed to validate the models developed within this work.

The integration of a LCPVT system as the main energy source for water desalination was studied by Santana et al. [65]. The LCPVT-VMD system achieved promising results during evaluations of solar-powered water desalination. The research provides no evidence of a working prototype, nor does it include pilot-scale demonstrations. The cost-effectiveness analysis focused solely on Acapulco, which restricted its general applicability. The system’s integration methods for combining it with different solar technologies have not been investigated yet.

Calise et al. [66] introduced a solar trigeneration system by linking PVT collectors to seawater desalination through dynamic simulation and economic evaluation. The system shows promise yet requires better design and operational methods to achieve effective winter performance. The system depends strongly on feed-in tariffs together with public subsidies for its economic viability, and research should examine biomass integration for better hybrid system operation.

Chen et al. [67] completed numerical research on solar district heating systems with PVT collectors and pit thermal storage to demonstrate excellent theoretical performance. The research lacks real-world testing and used only a high-solar-resource location (Lhasa) that might not generalise to other regions. System parameters require additional optimisation to achieve a proper balance between system dimensions and performance metrics, and environmental sustainability aspects.

Atiz [68] explored PV- Proton Exchange membrane (PEM) and PVT-PEM system integration for hydrogen production, which proved they have a lot of potential to be utilised in clean energy technologies. The study does not yield a comprehensive analysis of the system performance under various operating conditions. System efficiency improvement under various climate regions, the fabrication of improved components, along with effective integration approaches, should be the focus of research activities.

Barthwal et al. [69] proposed a spectral beam splitting-based PVT system using a nanofluid optical filter to achieve higher thermal output without compromising electrical efficiency. While the system showed promising results with a splitting ratio of 1.6, the study assumed ideal nanofluid behaviour and did not assess real-world factors such as long-term stability or varying solar conditions. Further research is needed to evaluate the collector’s durability, performance under dynamic weather, and integration with tracking systems for practical deployment.

A comprehensive summary of PVT applications in different industries is provided in Table 3, which also includes information on collector types, operating temperatures, use cases, and geographic contexts. It presents important research gaps related to flexibility, affordability, system efficiency, and stability over time. It also highlights system performance results, such as thermal and electrical outputs.

Table 3.

Summary of PVT system applications and research gaps in industrial and specific sectors.

This section underscores that the deployment of PVT technologies within industrial environments remains under-investigated, primarily due to the paucity of PVT collectors explicitly designed for such applications. Despite this, existing research indicates concentrated interest in evaluating the performance of commercially available PVT systems across various industrial processes, including water desalination, food processing, district heating, and boiler water pre-heating. Nonetheless, the current state of research is predominantly theoretical, relying heavily on numerical modelling owing to the low technology readiness level (TRL) associated with these integrations. This reliance highlights a significant research gap in empirical validation and performance assessment under real-world operational conditions, which is critical for advancing the practical adoption of PVT solutions in industrial settings.

4.2. Environmental and Policy Considerations

Gomes et al. [73] explored the legal and incentive frameworks for PVT systems across various parts of Europe. The findings highlight the use of PVT with concentrators (CPVT) and flat plate collectors with water-cooling methods for their heat recovery capabilities based on Directives 2009/28/EC and 2018/844/EU, under existing renewable energy source (RES) regulations for electricity (RES-E) and heating (RES-H). Incentives vary significantly between countries, ranging from tax reductions and feed-in tariffs to investment subsidies. The UK supports RES-E through a feed-in tariff, Contracts for Difference scheme, and tax regulation mechanisms implementing the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI). The Non-Domestic RHI provides payments to businesses and public sector organisations, while the Domestic RHI is open to homeowners and landlords. Notably, while most RES technologies are eligible for these incentives, the Domestic RHI does not currently support PVT systems specifically.

Acosta-Pazmiño et al. [74] presented a prospective analysis of the technical and CO2 abatement potential of industry-grade PVT collectors in the Food and Beverages (F&B) sector in Mexico. The collectors were based on a conceptual low-concentrating PVT collector (LCPVT). The study found that, in Mexico, such technology has a technical potential of 7.3 million m2 by 2030 and could lead to a greenhouse gas emission reduction of up to 51.7% in the F&B sector. This outcome highlights the increased decarbonization potential of PVT technologies compared to conventional solar technologies, particularly when space is a limiting factor. However, the analysis did not consider the environmental impact of the production, usage, and end-of-life stages of the collectors.

4.3. PVT Market Overview

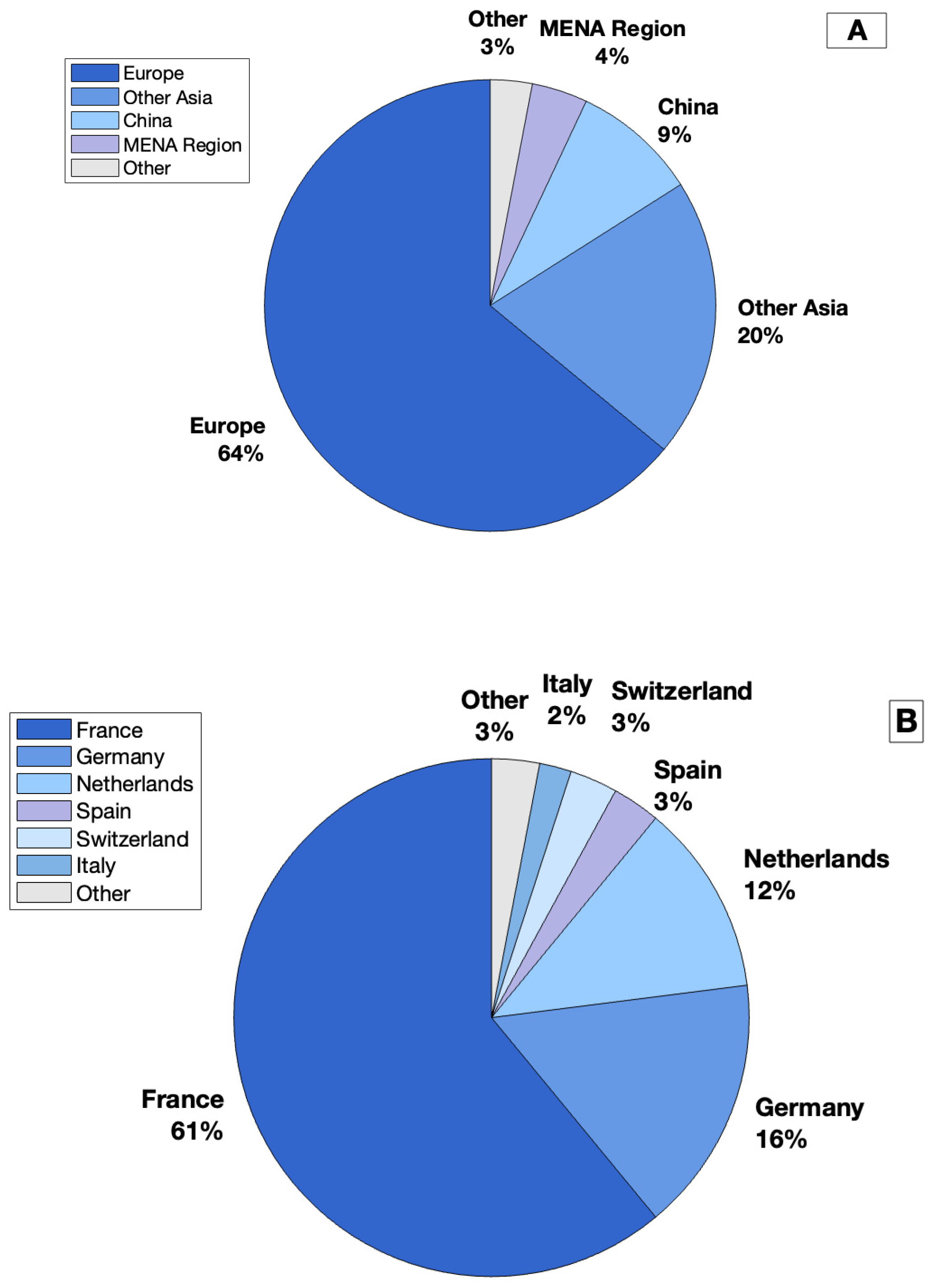

Based on the report by Weiss and Spörk-Dür [16], the total PVT collector area in 2023 was 1,589,553 m2. As illustrated in Figure 6A, Europe accounted for the great majority of this installation, 1,011,212 m2 (representing a peak capacity of 292 MW and a total capacity of 822 MW), followed by Other Asia (318,329 m2) and China (146,926 m2). The rest of the installed area was distributed by the MENA countries (Iraq, Egypt, and Israel) (70,130 m2), Sub-Saharan countries (South Africa, Ghana, and Lesotho; 22,926 m2), the United States and Canada (11,133 m2), Australia (3576 m2), Latin America (766 m2), and other regions (4555 m2).

Figure 6.

Regional share of total installed PVT area in 2023 ((A): Worldwide, (B): Europe).

Within Europe, France leads the European market in the installed collector area (616,551 m2); Germany and the Netherlands follow with 162,549 m2 and 127,303 m2, respectively. Spain, Switzerland, and Italy are the followers, with collector areas ranging 25,915 m2 to 34,192 m2. while other European countries accounted for 23,664 m2 (see Figure 6B for a detailed regional breakdown).

Figure 6 shows that in the leading countries, most installations are uncovered PVT water collectors (63%), with air PVT collectors at 33% and covered PVT water collectors at 4%. Further details on thermal and electrical power capacities are presented in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

The top cumulative area by type of PVT collector by 2023.

Table 5.

Thermal and electrical PVT capacity installed in 2023.

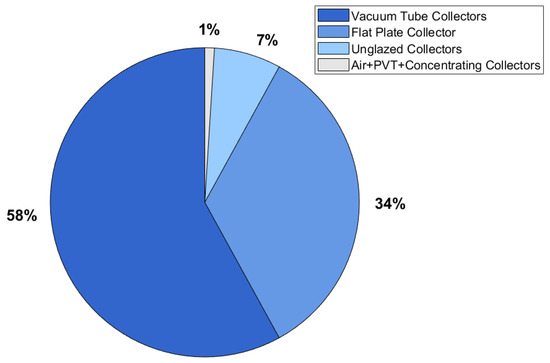

4.3.1. Global PVT Market Statistics and Trends

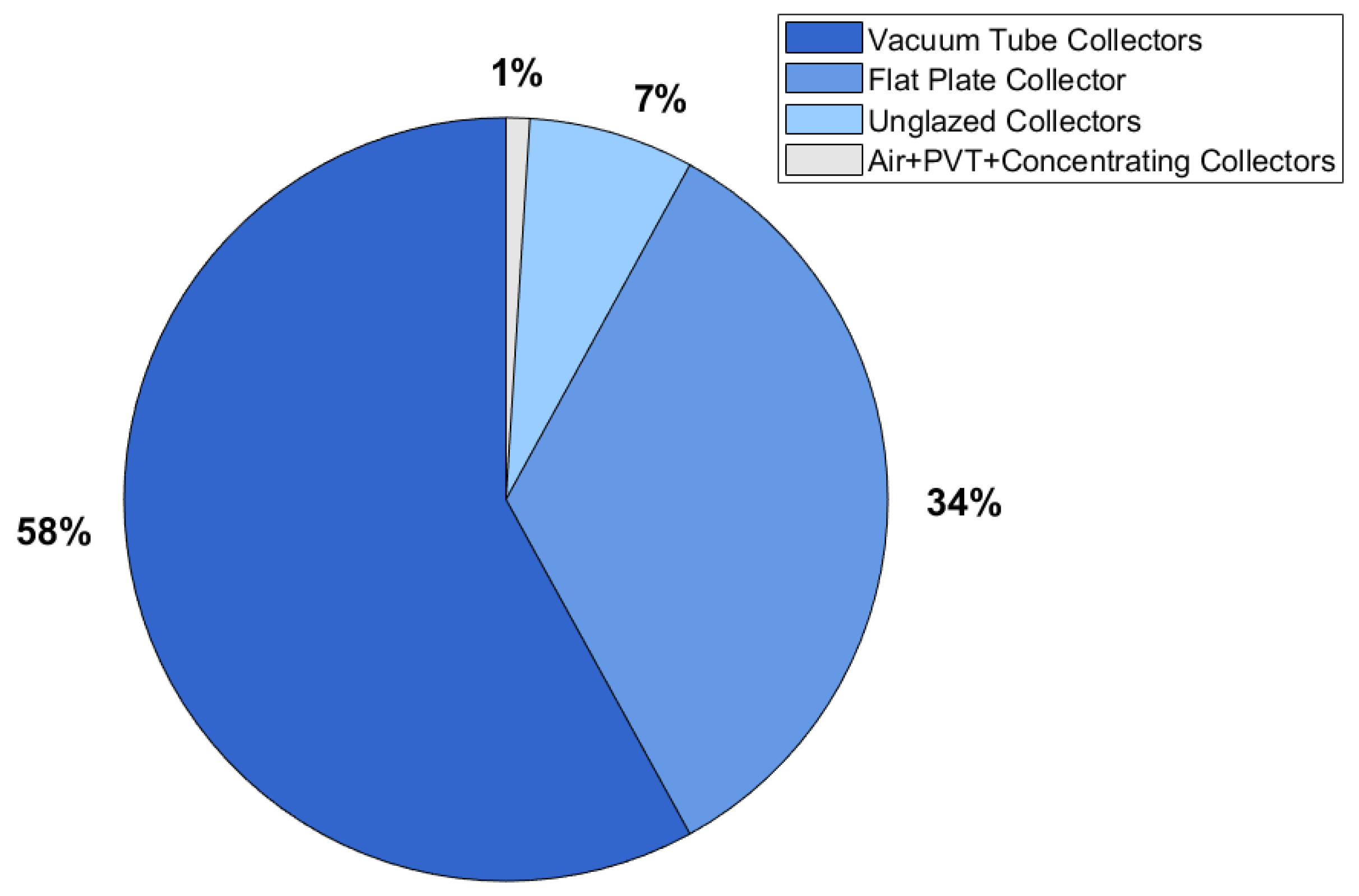

Based on the Weiss and Spörk-Dür [16] report, various aspects of PVT technology’s application and installation were investigated. The pie chart in Figure 7 shows the market distribution of solar collector technologies for various heat applications. Vacuum tube collectors dominate with 58% of the market share, valued for their high efficiency, especially in colder climates. Flat plate collectors follow at 34%, offering a simpler and often more cost-effective solution. Unglazed collectors, typically used for low-temperature needs like pool heating, account for 7%. The remaining 1% is split between more specialised technologies: air collectors, PVT collectors, and concentrating collectors. This breakdown illustrates that vacuum tube and flat plate collectors are the most widely adopted solutions, while other technologies serve niche markets or specific heat requirements.

Figure 7.

Different collector technologies’ contribution for various heat needs in 2023.

4.3.2. PVT Market Growth

An overview of PVT systems’ present state and impact is given in Figure 7. By generating three to four times as much combined energy (heat and electricity) as a traditional PV system in the same space, PVT technology provides a notable energy efficiency benefit. Currently, 1.6 million square meters of PVT collection areas worldwide demonstrate the widespread use of this technology. Belgium and Spain have experienced notable growth in the adoption of PVT systems. In 2023, the leading markets for PVT installations include China, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Spain. Furthermore, the use of PVT collectors is expanding in public and commercial buildings, showcasing the growing integration of this dual-function technology in diverse applications.

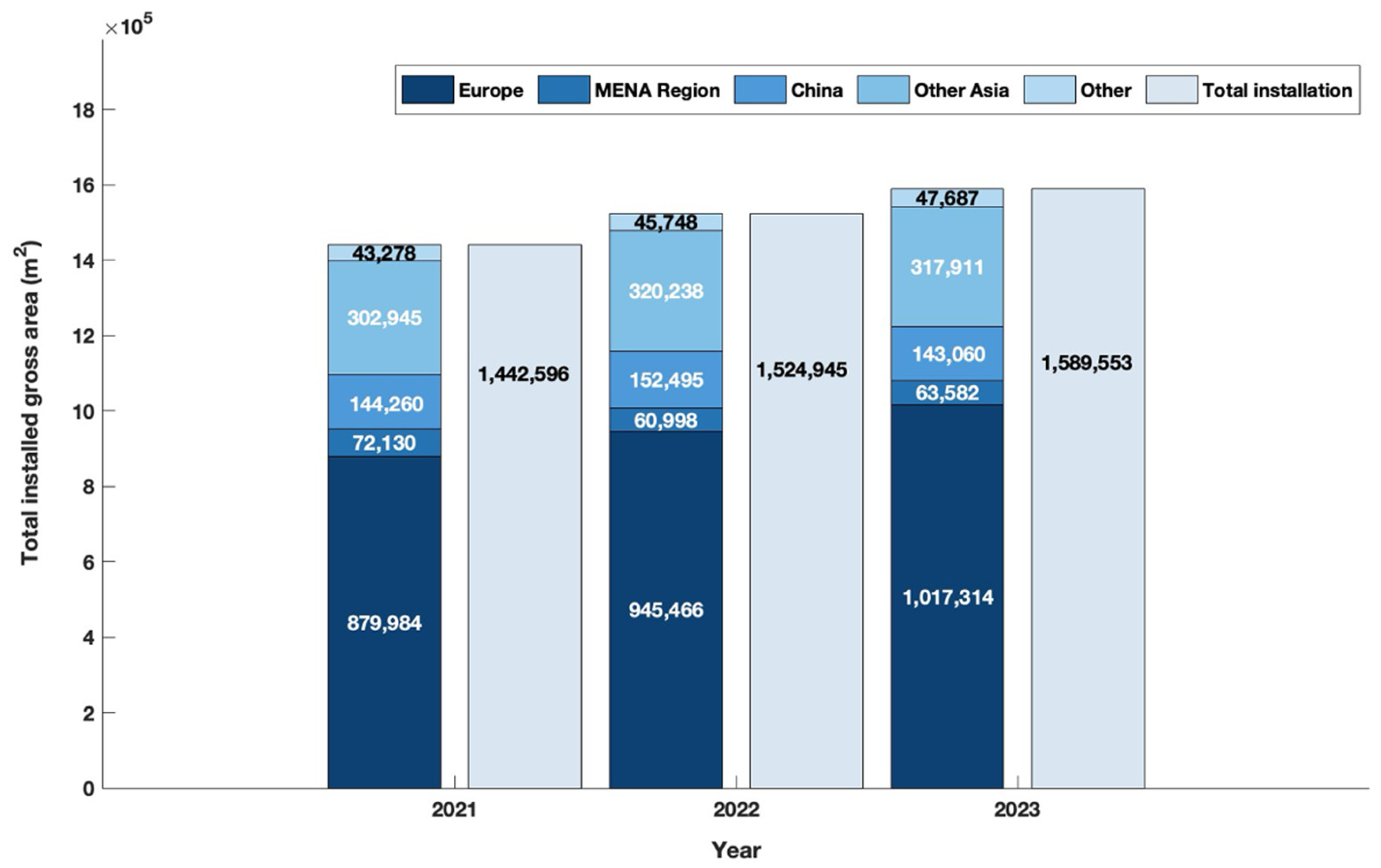

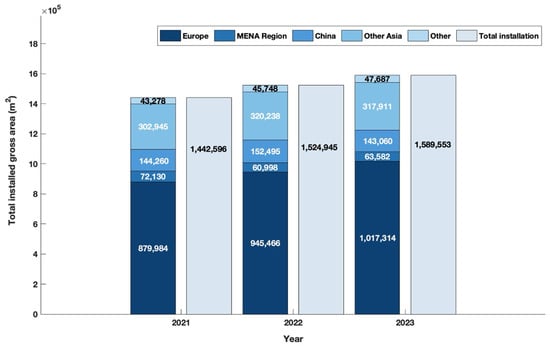

The graph in Figure 8 illustrates the global growth in the installed gross area (in square meters) of PVT collectors from 2021 to 2023. During this period, the total installed gross area of PVT systems increased steadily across all regions, with notable contributions from Europe, China, and other parts of Asia [16,75,76].

Figure 8.

Global market development of PVT collectors’ area [16,75,76].

Global PVT systems grew steadily from 2017 to 2021, supported by various subsidies. The sector faced significant setbacks in 2022, with a steep 37% decline attributed to supply chain disruptions, rising material costs, and geopolitical uncertainties. Regrettably, this downward trend continued into 2023. In that year, newly installed PVT capacity amounted to 29.5 MWth, with a peak electrical output of 14.5 MW. Compared to 2022, this number represents a 30.4% decrease in installed thermal capacity [77]. Despite the decline in new installations, the cumulative growth in both thermal and electrical capacities continued, albeit at a slower rate. In 2023, the total installed electrical capacity reached nearly 1200 MWp, indicating that the expansion of the PVT market is ongoing, although at a slower pace. The French market’s collapse was the primary cause of the notable worldwide drop that began in 2022. The market collapse of Air PVT collectors in 2022 (−90%) and 2023 (−16%) was caused by changes in the French funding structure. Germany (−22%) and the Netherlands (−59%), two other historically robust PVT markets in Europe, both announced market reductions in 2023. Positively, PVT markets were expanding in some European nations. Belgium saw a 20% increase (1018 m2), whereas Spain reported a +34% increase (7832 m2). Nevertheless, the rise in these nations was insufficient to offset the general market downturns [16].

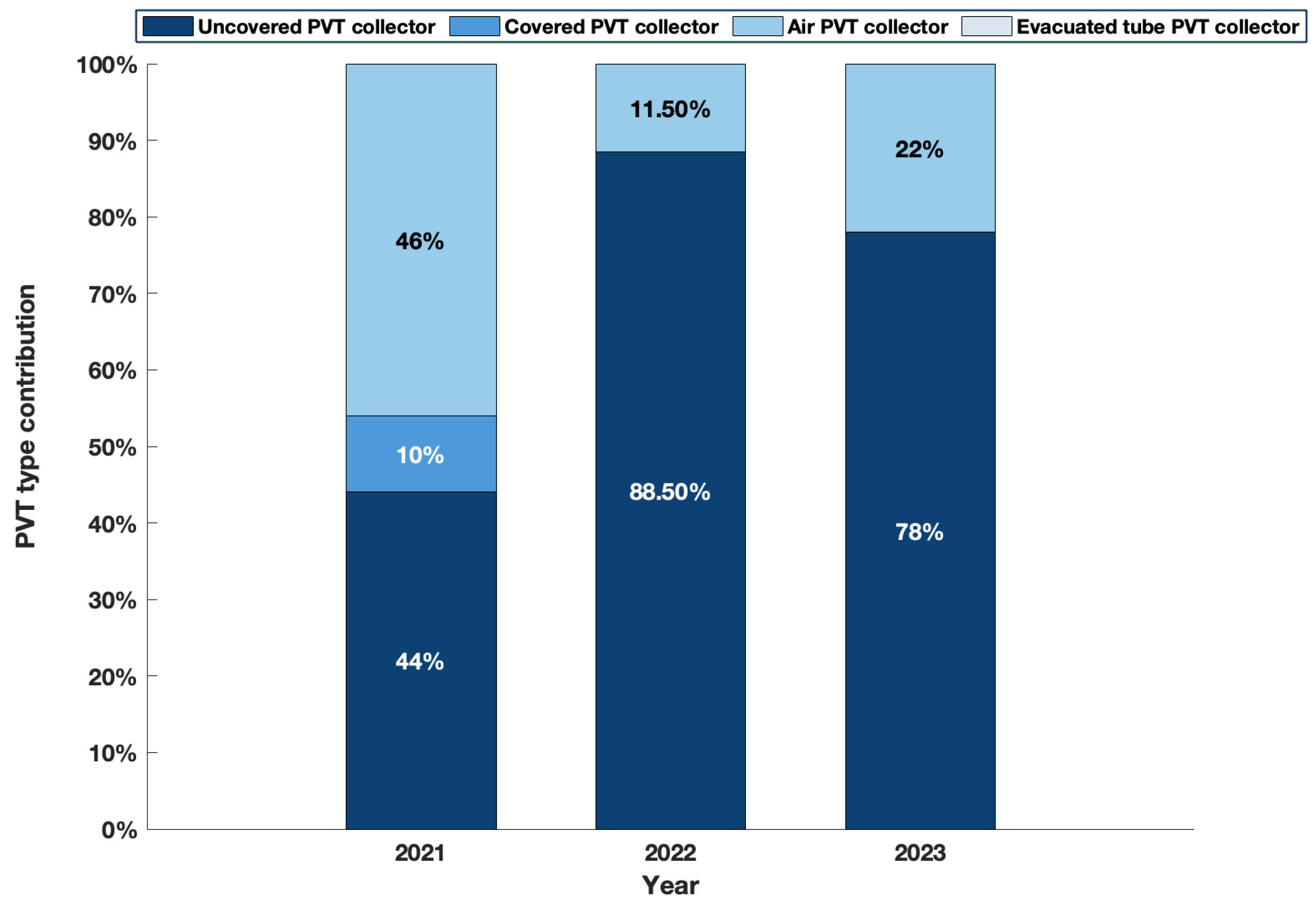

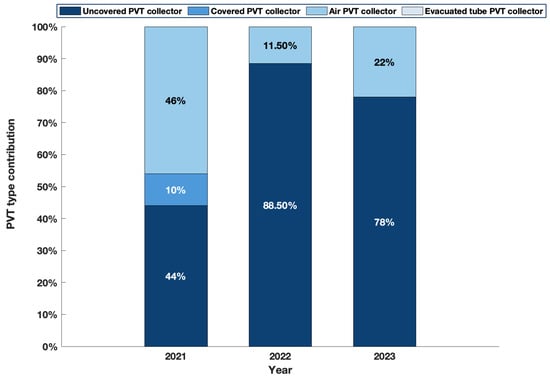

Figure 9 shows the breakdown of the different types of PVT collectors over the period of the last three years. In 2021, air PVT collectors made up 46% of all collectors, surpassing uncovered PVT collectors at 44%. France had a significant market fall in air PVT collectors in 2022. Instead, the uncovered type expanded its share of the market, standing at 88.5%. In 2023, the contribution of covered PVT increased by 10%, but the percentage of uncovered PVT dropped little, from 88.5% to 78%. Concentrated, evacuated tube, and air-based PVT collectors have almost vanished from the marketplace [16].

Figure 9.

Distribution by type of newly installed PVT collectors worldwide [16].

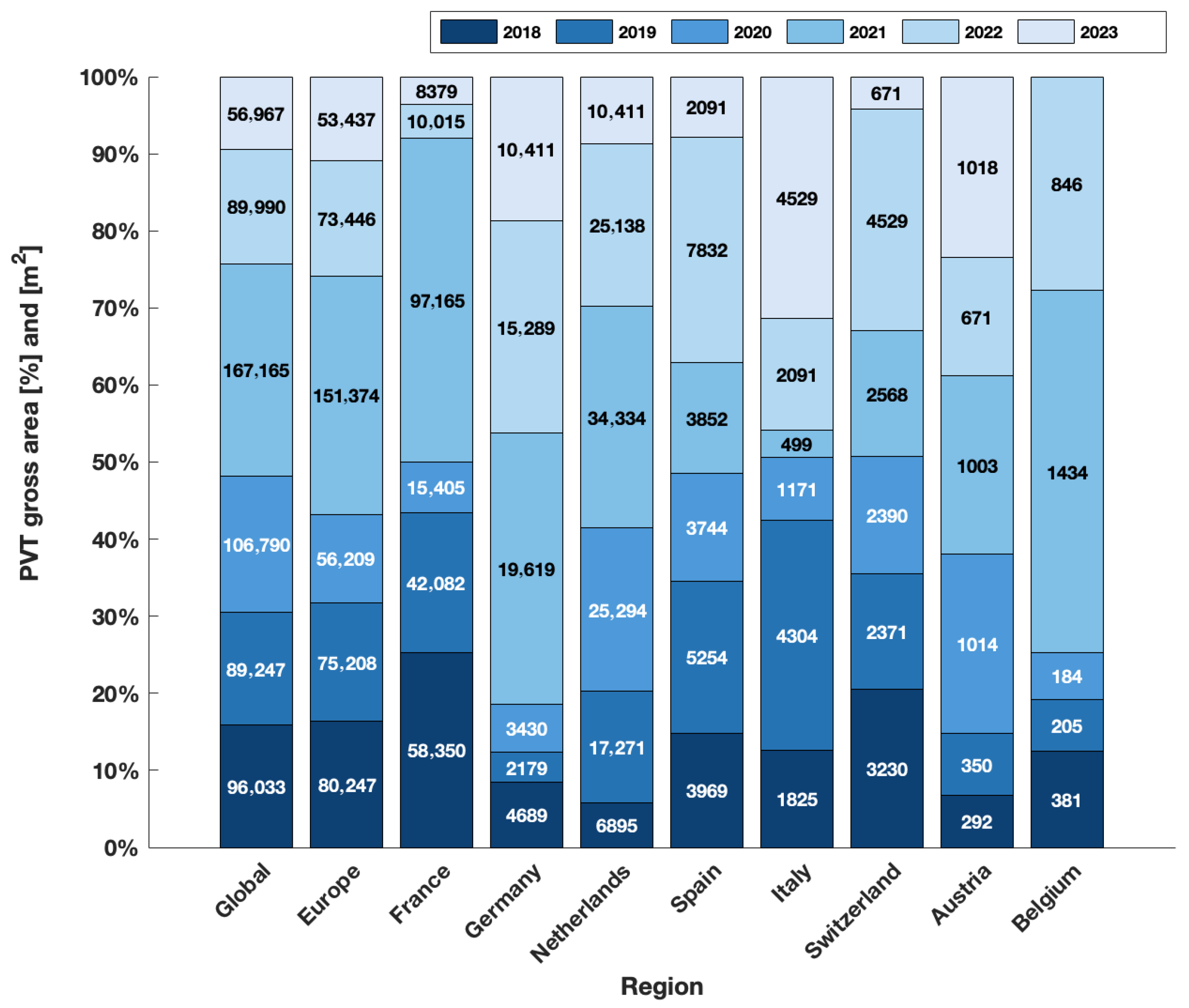

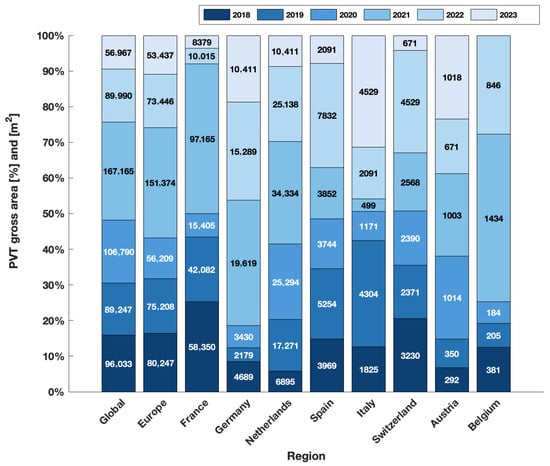

Figure 10 illustrates the growth of PVT collector installations across various regions globally and in specific countries. It represents the cumulative PVT gross area in square meters (m2) and percentage versus the regions and countries. Each bar is segmented by year (2018 to 2023), with darker shades representing earlier years and lighter shades indicating recent years. The data shows a clear upward trend in PVT installations, particularly significant in global and European totals, with notable surges in France, Germany, and the Netherlands from 2020 on. Other countries like Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, and Belgium also demonstrate smaller but steady growth in installed PVT areas, especially in the last two years.

Figure 10.

PVT collector areas newly installed in leading countries [16].

4.4. Large-Scale PVT Projects

European PVT producers and developers are scaling up their operations to meet the growing demand for integrated solar solutions that provide both electricity and heat. Several manufacturers across Europe are heavily investing in the development of higher-efficiency PVT products, focusing on innovation to increase performance and feasibility. These companies are expanding their production capacities with two key goals: to lower costs through economies of scale and to meet the rising demand for renewable energy resources. In response to Europe’s commitment to solar energy, many companies are rapidly constructing large-scale PVT plants. Below are three leading companies and market players in the European PVT industry, along with their flagship projects [78].

4.4.1. Sunmaxx PVT-Germany

Sunmaxx is a global leader in the development and production of cutting-edge PVT systems. Leveraging a unique combination of solar and automotive technologies, Sunmaxx focuses on sector coupling to transform the energy landscape. Their vision is to achieve climate-neutral solutions for residential, commercial, and industrial buildings. Sunmaxx’s PVT modules, particularly when paired with heat pumps, offer a sustainable and efficient approach to heating and cooling without reliance on fossil fuels. Since 2021, the company has been operating in Dresden, where it has been developing cost-effective PVT systems designed for mass production, playing a key role in decarbonising the heating sector [79].

Sunmaxx has been involved in several notable PVT installation projects across Europe, contributing to decarbonisation efforts by providing both electricity and heat through their innovative photovoltaic-thermal modules. One prominent project is in Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. In this project, Sunmaxx is supplying PVT modules for a municipal heat network, using 156 of their highly efficient PX-1 modules to provide low-temperature heat and electricity for a historical building as part of a local heating network initiative. This project is expected to accelerate the decarbonization of the building sector by replacing conventional energy sources with renewable energy.

Additionally, Sunmaxx is working with MAHLE, a major automotive supplier, to decarbonise their production facilities in Vaihingen an der Enz, Germany. This project, which involves the integration of PVT modules, aims to fully replace fossil fuel-based energy at the site. Furthermore, Sunmaxx has partnered with Kütro GmbH & Co. KG, a solar and heating specialist, to install PVT modules for both private and municipal heat networks, with plans for large ground-mounted PVT systems in the future. Sunmaxx PVT has started expanding its automated module production facility in Saxony. Having the ability to produce 120,000 panels annually, equal to 50 megawatts, this is the largest PVT production in the world [78].

4.4.2. Abora Solar-Spain

Abora is a Spain-based company specialising in the design, development, and manufacturing of hybrid solar panels, with a team possessing extensive expertise in the solar energy sector. The company’s commitment to sustainability reflects its broader mission to drive the utilisation of renewable energy sources while contributing to these global objectives [80]. Table 6 shows a list of major recent projects developed by Abora Solar.

Two strategies are behind the Abora Solar factory’s significantly higher production capacity. Initially, Abora Solar optimised the existing production line, resulting in an increased output volume of 180,000 collectors each year—up from 100,000 previously. Furthermore, Abora has set up a second production line for a brand-new PVT collector that is scheduled to launch in 2025 [81].

Table 6.

Overview of Large-Scale Projects Developed by Abora Solar [82].

Table 6.

Overview of Large-Scale Projects Developed by Abora Solar [82].

| Project | Sector | Location/Installation Year | Usage | Number of Panels | Total Savings of Emissions | Electrical Production | Thermal Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swimming Club—Barcelona | Sports centre | Spain/2023 | Swimming pool and DHW heating | 1041 | 774,809 kgCO2/year | 543,438 kWh | 1,641,095 kWh |

| Kungsbacka | Rest Home | Sweden/2023 | DHW + Heating + Electricity | 126 | 55,640 kgCO2/year | 42,716 kWh | 120,054 kWh |

| Babylon Hotel | Hotel | The Netherlands/2023 | DHW + Electricity | 31 +104 PV | 18,368 kgCO2/year | 47,310 kWh | 27,919 kWh |

| Ruigrok | Hotel | The Netherlands/2023 | Hot water + electricity | 44 | 14,723 kgCO2/year | 14,546 kWh | 39,676 kWh |

| Hospital La Maz | Hospital | Zaragoza/2023 | DHW + Electricity | 90 | 66,684 kgCO2/year | 51,881 kWh/year | 137,320 kWh/year |

| Hotel Iberostar Albufera Park | Hotel | Spain/2023 | DHW + Pool | 180 | 174,693 kgCO2/year | 70,988 kWh/year | 274,068 kWh/year |

4.4.3. DualSun-France

DualSun is a French startup that is well-known for producing uncovered PVT collectors. The DualSun facility, which can readily be expanded to meet market demand, can currently produce 30,000 PVT elements, or 15 MWel, of output. DualSun’s flagship product, the SPRING panel, is a highly efficient 2-in-1 hybrid panel that optimises energy output per square meter, producing up to four times more energy than conventional photovoltaic systems. The SPRING panel recovers heat power from the solar panel and channels it to hot water, making it ideal for residential, commercial, and industrial applications, including heating systems, swimming pools, and domestic hot water [83].

Table 7 summarizes their hybrid PVT projects across Europe, detailing panel counts, energy outputs, and applications in residential and commercial buildings, emphasizing the role of hybrid panels in integrated solar solutions.

Table 7.

Overview of PVT projects in Europe by Dualsun [83].

Literature has a developing interest in applying PVT systems in a variety of settings, from offices, residences, and convenience stores to industrial processes like desalination, wastewater reuse, and de-dust reduction processes. In buildings, PVT has been credited with the ability to provide energy requirements for both building space conditioning and electricity, enabling building infrastructures to approach almost zero energy building (nZEB) ratings. PVT case studies in diverse climatic conditions, across South Korea, India, Italy, and Morocco, show functional performance and economic viability. In industries, PVT technology has been explored in electricity supply and supply with higher-grade process conditions, like boiler water pre-heating. While the preliminary evidence is reassuring, an overbearing research void continues, where empirical confirmation under real-world conditions, with few exceptions, has been undertaken. The large majority remains hypothetical, where computational simulations alone are utilised without longer-term experimental information, focusing on durability, as well as reliability under variable operational conditions. Economic viability remains equally underdeveloped, with cost-efficiencies sometimes modelled after lower-readiness technology, and geographically isolated, often omitting geographical expansion. Accordingly, future research should focus more on real-world prototype realisation, with longer-term performance characterisation, comprehensive lifecycle assessment, and an intention to bridge theoretical promise, with practical realisation. An exergy-based approach is essential for economic analysis and financial modelling to determine a system’s value proposition accurately. Simple energy summation inflates projected revenue streams and shortens calculated payback periods by failing to account for the substantial market value difference between high-grade electricity and low-grade heat. Similarly, in LCA, a system’s environmental benefit is measured by the emissions it displaces. Future LCA must differentiate between the carbon intensity of the grid electricity being offset and that of the fuel (e.g., natural gas) being replaced for heating. Engineers and investors require bankable performance data to plan large-scale installations, such as in industrial parks or district energy networks. An exergy-defined output provides this clarity, enabling correct sizing of infrastructure and reducing capital investment risks, thereby opening the way for PVT technology to transition from a niche solution to a significant contributor to future energy systems.

5. Technological Challenges and Future Opportunities

Hosouli et al. [84] offers a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method for choosing the best PVT collectors based on several performance metrics, including cost, thermal efficiency, and electrical efficiency. The study uses advanced methods to compare different PVT modules available for sale and rank them based on how well they fit specific uses. The criteria considered include electrical efficiency, thermal performance, maximum working temperature, and price per unit area. A MATLAB-based tool was also developed to facilitate this selection process. The findings demonstrate the effectiveness of these MCDM methods in identifying the best PVT collectors, with the results providing insights into optimising renewable energy system design and deployment.

Chandrasekar et al. [85] analysed the PVT technology changes over the last 50 years, emphasising its advancement and useful uses in a range of industries, including desalination, drying, refrigeration, power production, and building thermal comfort. Design, building integration, concentrated PVT, phase change materials, nanofluids, and energy and environmental analysis are some of the categories under which the review divides the development of PVT systems. It emphasises the advancements in material science and integration techniques, such as the use of nanofluids and PCMs, which have significantly enhanced thermal and electrical efficiencies of PVT systems. The study also points out the ongoing challenges, including the need for standardisation, cost reduction, and addressing stability and long-term reliability issues.

Kazem et al. [86] provided a systematic review of integrating PVT systems with heat pumps. The study categorised different PVT-HP configurations, including direct and indirect solar-assisted heat pumps, and explored the use of innovative materials like nanofluids and advanced refrigerants to optimise system performance. While these integrated systems show promise for enhancing energy sustainability in buildings and industrial processes, challenges such as high installation costs, complex system design, and the need for specialised maintenance persist.

Kumar et al. [87] investigated heat removal mechanisms in concentrated PVT systems using spectral beam splitting (SBS) technology, which optimises the use of the solar spectrum for both electrical and thermal energy generation. SBS divides the solar spectrum into two segments, directing the optimal part to photovoltaic cells for electricity generation while using the rest for thermal applications. The paper discusses various methods of SBS, including thin-film and nanofluid-based filters, as well as the use of solar cells as reflectors. Nanofluids show promise for improving thermal efficiency. The study highlights recent advancements in SBS technology and its potential to enhance PVT system performance, particularly in industrial applications requiring high-temperature outputs. However, challenges remain in developing cost-effective, stable, and efficient SBS filters for widespread use.

6. Conclusions

This paper provides a review of PVT solar technologies, including their categories, capabilities, integrating methods, and developments from over 80 studies, indicating their growing role in residential and industrial applications. Research findings suggest that by circulating a heat transfer fluid (like water, air, or nanofluids), PVT collectors cool the PV cells and enhance their electrical performance while generating useful thermal energy simultaneously. Water-based PVT systems typically achieve electrical efficiencies of 8–17% and thermal efficiencies of 30–70%, while nanofluid-based systems, especially with eco-friendly GNP nanofluids, have shown greater enhancements, and increased electrical efficiency by up to 5.8% and thermal efficiency by 55.22% in specific setups.

Integrating PCMs and TEGs further enhances system performance by helping in temperature control. PVT systems are flexible in different settings, from space heating, hot water heating in homes, and heat pump integration to cooling, desalination, and greenhouse drying. They are increasingly integrated into buildings as BIPVT systems on facades, windows, or rooftops, providing self-energy supply and improving insulation. The evolution of technologies such as SBS and PVT-HP also shows promise for optimising solar spectrum use for both electrical and thermal energy, though cost-effective, stable, and efficient filters are still needed for widespread adoption.