1. Introduction

Among other things, each building envelope serves to protect the interior from the effects of the natural environment. Maintaining adequate comfort inside a building involves defining several appropriate parameters such as temperature, humidity, daylight, sunlight, etc. Furthermore, interior and exterior equipment can also impact interior spaces and require energy delivery to the building. Some of the most important challenges are preventing heat loss during cold seasons and excessive temperature rise during hot periods and providing adequate amounts of energy, usually electricity, for the ongoing operation of building equipment.

The moderate climate of Central Europe makes it advisable to modernize many buildings, both in terms of the thermal insulation of building envelopes and ecological sources of electricity and equipment. Thermal modernization of building envelopes results from the relatively low average temperature of the external environment during three cool and cold seasons [

1]. Modernization involving installation of ecological energy sources, including photovoltaic installations (PVIs), is possible due to the relatively high solar potential of the natural environment [

2].

Therefore, actions based on the analysis of needs in terms of preventing the impact of the urban environment and using the potential of photovoltaic installations, green humidifying and cooling layers of housing, and thermal insulation seem justified in synergy with nature as part of a broader strategy of sustainable development of urban areas.

The results obtained by E. De Cristo et al. [

3] indicate the effectiveness of green roofs in mitigating heat stresses, enhancing building energy efficiency, and counteracting urban temperature fluctuations, reinforcing their function in urban strategy. The authors analyzed the potential of green roofs to promote sustainable urban environments in Mediterranean regions. Their review identifies critical gaps regarding the adoption of green roofs. Finally, they found that the integration of green roofs and green façades in the built environment enhances thermal comfort, improves air quality, minimizes building energy needs, optimizes stormwater management, and increases urban biodiversity.

B. Maurer et al. [

4] performed a detailed analysis related to a holistic comparison of different roof PV installation types, including horizontal. The obtained results indicate the possibility of saving up to 49% more energy than the conventional systems, which led to a search for solutions related to the increasing substitution of energy supplied from external networks by electricity production using PVI. An analogous approach is proposed by Y. Movahhed et al. [

5], who expanded the topic to include other technical and economic aspects of designing green roofs. A parametric multi-criteria decision analysis that allows optimal results to be obtained is an important aspect indicated by the authors.

The modernization of buildings located on the Central European Plain in Central Europe is being carried out on a large scale due to the rising costs of building operation, mainly heating costs, and the normative legal acts developed by the European Commission [

6,

7]. These standards have a significant impact on undertaking activities to reduce the harmful impact of the building operation on the surrounding natural environment.

Tall buildings pose a particular challenge when it comes to modernizing their envelopes and installing exterior equipment. Working at high altitude significantly increases modernization costs. On the other hand, the student dormitory’s function increases the demand for electricity during continuous 24 h use of the building, which allows for the size and payback time of modernization investments to be optimized.

In Poland, a relatively large proportion of modernized student residences are equipped with gas-powered central heating systems and lack central mechanical ventilation and air-conditioning systems. Such systems are becoming increasingly necessary as average outdoor temperatures rise annually during the hot summer season [

8].

This article examines modernization, the key step of which is the balance of electrical energy produced by photovoltaic panels (PV panels) mounted on building envelopes. This modernization involves replacing a portion of the electrical energy supplied from an external grid with the electricity produced by PVI.

2. Critical Analysis of the Present Knowledge

The amount of solar radiation incident on a building’s envelope over a period of time is called the solar potential of the building. The potential for solar irradiation decisively justifies the use of PV panels for electricity production. A. Barman et al. [

9] analyzed the performance of photovoltaic building systems integrated with horizontal or vertical surfaces of high-rise buildings. Their analysis also showed that the vertical walls can harness almost 49% more energy than conventional horizontal-based systems. They also investigated the cloud shadow impact, which is highly significant for horizontally-mounted photovoltaic panels where losses can amount to 26%.

The quantity of solar radiation depends on the magnitude of its components, which are direct, diffuse, and reflected solar radiation [

10]. Of these components, direct solar radiation has a decisive influence on the electricity produced by PVI. The direction of the radiation is its characteristic property. The intensity of this radiation depends on the following: (1) the properties of the Earth’s atmosphere, such as its transparency, density, and moisture dispersing a beam of parallel solar rays; (2) the angle of incidence on a building envelope, and the properties of the envelope and PV panels, which influence the efficiency of capturing energy from solar radiation [

11].

Because of the complex rotation of the Earth around its axis and around the Sun, the change in the direction of solar radiation falling on a stationary building envelope is large and continuously changes throughout each day and each season [

12]. This article considers only stationary building envelopes and attached PV panels, which requires optimization of the orientation of the PV panel planes to achieve their effective operation depending on their location, azimuth, and tilt. R. Mueller et al. [

13] presented the diverse solar potential of various areas on the Earth’s surface. D. Buchalova et al. [

14] presented an effective method for calculating the solar potential of irradiated building envelopes using geographical information systems.

L. Tao et al. [

15] described a relationship between solar potential on building façades and urban morphology and a design of the façades with integrated photovoltaics. They presented a Random Forest algorithm combined with the Shapley Additive Explanations method, deserving special attention to assess the impact of urban morphology. They employed non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II to obtain optimal results referring to the south façade with 77 opaque PV panels and 49 semi-transparent ones that offer an optimal payback period of 8.44 years and power generation of 55,961 kWh, which can be considered as a configuration pattern for effective installations.

S. I. Kaitouni et al. [

16] elaborated an analogous method for parametric determination of the solar potential of tall buildings and energy-driven optimization modeling. The specific advantage of this method is the automatic iterative change in a series of predefined design parameters. Two important variables related to building geometry deserve special attention: the shape and orientation of buildings. These turn out to be crucial in optimizing the solar potential of building envelopes and electricity production. The researchers found that PVI was able to improve the renovated buildings by up to 12.4%.

M. Súri et al. [

17] presented a method for determining a GIS-based solar irradiation model to estimate the solar irradiation potential for the Central European Plain area, which ranges from 850 to 1050 kWh/m

2. This range is consistent with the range of values defined by Ł. Kolendo and A. Krawczyk [

18] for the Central European Plain areas located in Poland. All basic parameters of the environment in which the building is to be constructed can be downloaded from the websites of several ground-based meteorological stations and meteorological web portals [

19,

20]. In this article, the location of the buildings studied was assumed to be in Poland, i.e., in Rzeszów, with geographical coordinates of 22° N and 54° E and an altitude of 300 m above sea level.

N. Aste et al. [

21] performed dynamic computer simulations of PVI operation to achieve the net zero energy target in residential multi-story buildings located in various geographical zones. The authors investigated the effect of shape and orientation of multi-story building envelopes on the amount of energy supplied to these buildings. They proved that the net zero energy target can be achieved for energy-efficient buildings with up to three and five stories, in Nordic and Mediterranean climatic conditions, respectively. Thus, the electricity produced by PVI can only partially replace the energy delivered to tall multi-story dormitories via external networks.

M. Asif et al. [

22] analyzed four different PVIs in terms of the rearrangement of rooftop obstacles, potential for future PVI expansion, overall complexity of PVI construction and installation, the shapes of the examined envelopes, and financial aspects A. Young-Sub et al. [

23] performed analogous research regarding renovations of envelopes of tall buildings with increasing surface areas of photovoltaic panels distributed on vertical façades and skew roofs. They analyzed and simulated the power generation rates of buildings with integrated PVI. Ch. Xiang et al. [

24] developed a holistic architectural method supporting the integrative design of façade integrated photovoltaics (FIPVs) for residential high-rise buildings based on balcony prototypes and position arrangements The performed solar radiation analysis based on a series of simulations revealed the fact that the estimated annual energy generated by FIPV together with roof-integrated PVI can even cover up to 60% of household energy consumption in an 11-floor high-rise apartment block.

The difference in solar potential between different building forms results, among other things, from different azimuths and inclinations of envelopes’ surfaces and causes a corresponding difference in the electrical energy production of PV panels. The difference can be reduced by increasing the efficiency and size of PVI.

A slightly different approach was presented by G. Evolaa and G. Margani [

25]. They applied the solar potential of PV modules to balance the annual electricity need for artificial lighting, electric appliances, and space heating and cooling determined through dynamic energy simulations of high buildings located in Mediterranean and temperate zones. Their parametric analysis was performed by virtually changing the orientation of the buildings and the number of floors. The authors confirmed an almost-standard nine-year payback period calculated for renovating an eight-floor apartment block, if considering the current fiscal incentives and a 50% self-consumption rate. V. Shekar et al. [

26] increased the scope of the analysis by presenting a new method of determining the optimal azimuth for solar-ready buildings. The method was based on computer simulations minimizing the economic costs of PVI in Finland. The authors proved that the annual energy balance performed with the help of their method can increase the surplus energy generated via renewable energy systems by 46% compared with conventional energy production.

P. Bakmohammadi et al. [

27] described two parametric case studies for a multi-story building at the University of Alberta campus in Canada. They analyzed the impact of five parameters related to the horizontal and vertical distances between individual PV panels, azimuth, tilt, and rotation angles of the panels on the payback periods of renovations using a quasi-stationary method during simulations, convolutional neural networks during statistical calculations, and multi-criteria decision-making in defining the relations found during simulations. Their results showed relatively long payback periods of 36 or 31 years.

To obtain a universal description of the electrical energy balance of various modernized buildings, a parametric analysis should be carried out based on parametric qualitative and quantitative models configured with the help of the relationships found during tests and simulations [

28]. Complex parametric descriptions of the relationships are often accomplished with various artificial neural networks. In addition, optimizing processes are realized with genetic algorithms. S. Luo et al. [

29] conducted such a sensitivity analysis with their proprietary parametric building model, using as many as fifteen independent variables and three dependent variables to improve the optimization efficiency of building retrofits. A new parametric model of typical high-rise residential buildings with photovoltaic panels elaborated by H. Wu et al. [

28] was employed to improve the calculation efficiency of building’s total air-conditioning and heating load in a multi-objective optimization process. The process was based on the Wallacei software (V 2.7) module embedded with the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) and the nine selected input parameters related to geometric, physical, and location parameters of building and PV panels.

Very important research was carried out by M. K. Ansah et al. [

30]. The authors presented a significant role of the integrated photovoltaic façades (BIPVs) of high-rise buildings in terms of the increase in global warming potential (GWP) for the material production, maintenance phases, and building service. They showed that about a 21% reduction in GWP can be achieved by means of BIPV compared with the reference models and a payback period of about four to five years.

The short description included in

Table 1 represents a synthesis of the research results presented above related to the energy renovation of multi-story buildings. It compares the results of the examined research to date and indicates the directions taken by the researchers.

Based on the above review, the following gaps and critical remarks were identified. The first is the automation of calculations performed during each energy efficiency modernization process of tall residential buildings located in temperate climate zones. Such automation can be implemented, e.g., in the Rhino/Grasshopper programming environment [

31]. It is desirable to extend this automation to include parameterization of the created models to obtain multiple effective solutions, from which optimal ones could be found. The optimal solutions should be associated with maximizing the electricity produced by photovoltaic installations or minimizing the costs incurred for modernizations. Automation supporting optimal solutions is particularly desirable when a single and most effective solution is sought without the need to analyze the impact of individual parameters on this solution and without searching for a number of similar effective solutions. The authors proved that such automation is possible using parametric procedures available in Rhino/Grasshopper.

3. Aim

The aim is to present a novel method for optimizing energy production and costs concerning renovations of multi-story cuboid student dormitories equipped with photovoltaic installations arranged on vertical façades. The method’s algorithm requires defining novel discrete and parametric input and output models before and after renovation. The elaborated parametric models allowed for computer simulations and full automation of calculations related to the optimization of electricity production by the designed new photovoltaic installation. Automation of the calculations for energy-efficient building renovation is possible within a single computational optimizing process, during which several subsequent iterative simulations of the photovoltaic installation’s operation are performed.

The innovative, qualitative model of renovated buildings was configured using computer simulations and real meteorological data provided in *.epw files by ground-based meteorological stations and online services. The accuracy of this model was verified based on a few selected discrete models built using online tools provided by the European Commission. The reliability of the developed model was also verified by comparing the results with the characteristics of a real, modernized, multi-story student dormitory located in Rzeszów in Central Europe at the geographical coordinates 50.20° N and 21.98° E and 300 m above sea level.

In the future, the final optimized parametric quantitative model of the renovated building can be used (1) to perform a parametric description of renovations of multi-story buildings producing electricity using PV panels, (2) to carry out various types of similar modernizations of buildings, and (3) to extend the applied method, based on the developed parametric model, with new possibilities related to electricity production and an increase in the thickness of thermal insulation of the building envelope.

4. Methodology

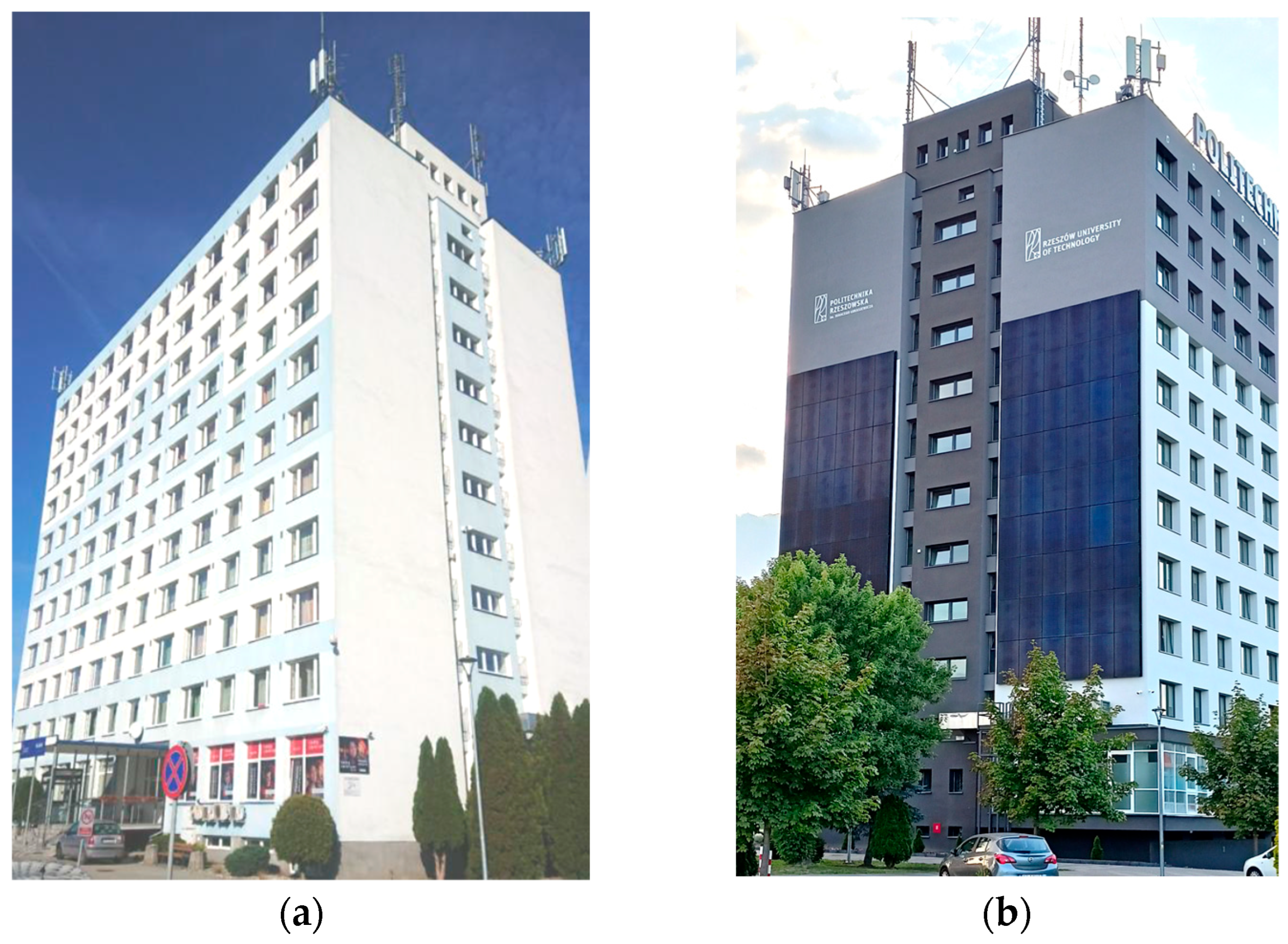

To renovate the high-rise student residence hall presented in

Figure 1, a process of optimizing the energy produced by PVI was proposed. The azimuth of the building, the surface area and orientation of the PV panels arranged on the southern and eastern façades of the modernized building were five optimized independent variables. To perform an optimizing process, it was necessary to develop a few parametric input and output models of building modernizations. Therefore, there were adopted: (a) eight input parameters in the form of independent variables Xi defining selected geometric and economic properties of the building and the photovoltaic panels fastened on its façades; (b) eight output parameters in the form of dependent variables Yi defining the state of the building after the modernization; (c) boundary conditions and optimizing conditions used in the simulations and the optimizing processes; (d) a load model.

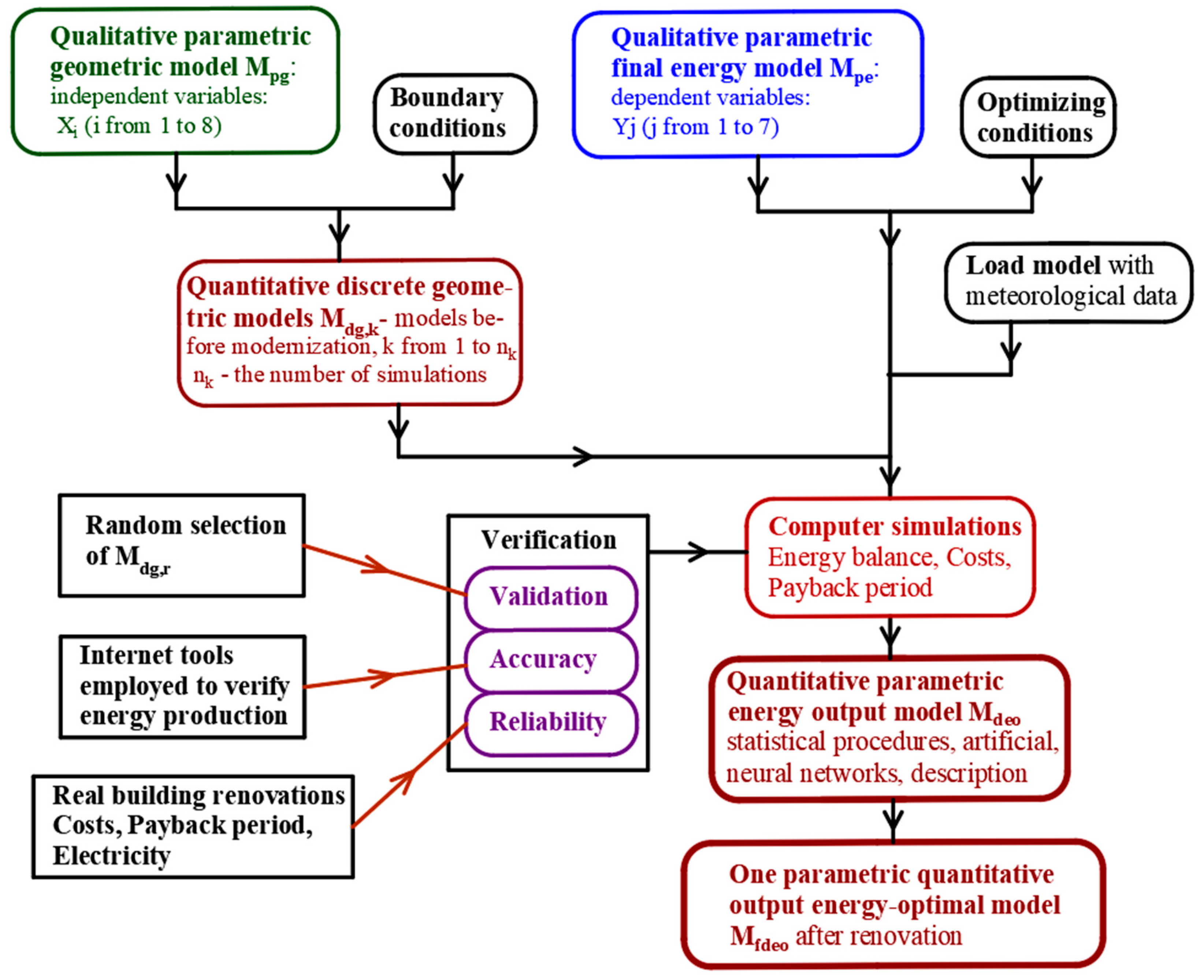

To define a qualitative parametric M

pg model of the modernized building the values of each input parameter Xi and the boundary condition were adopted, as shown in

Figure 2. This model was based on eight independent variables (input parameters): X1—the building azimuth; X2—the ratio of the PV panel area to the south façade area; X3—the ratio of the PV panel area to the east façade area; X4—the panel plane inclination angle to the south façade area; X5—the panel plane inclination angle to the east façade; X6—the energy replacement rates resulting from the replacement of a part of the net energy with the electricity produced by PVI; X7—the cost of 1 kWh of grid electricity; and X8—the ratio of the total costs of constructing 1 m

2 of PVI to the product of 1000 and the price of 1 kWh of grid electricity.

The examined boundary conditions refer to the range of discrete values to be assumed for the subsequent Xi variables in simulations and calculations. These conditions are constant. Their values are shown in

Table 2.

The diagram in

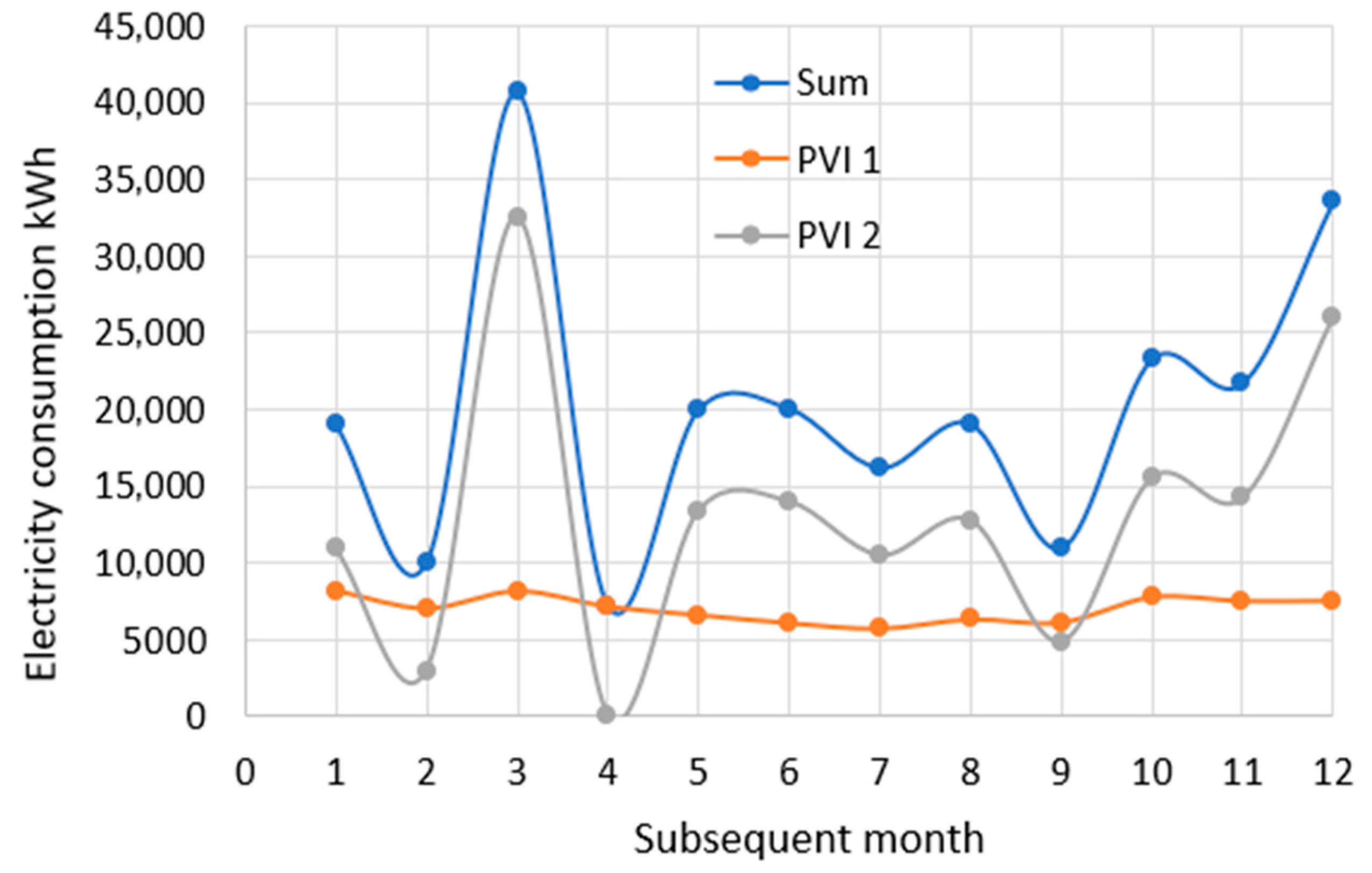

Figure A1 in

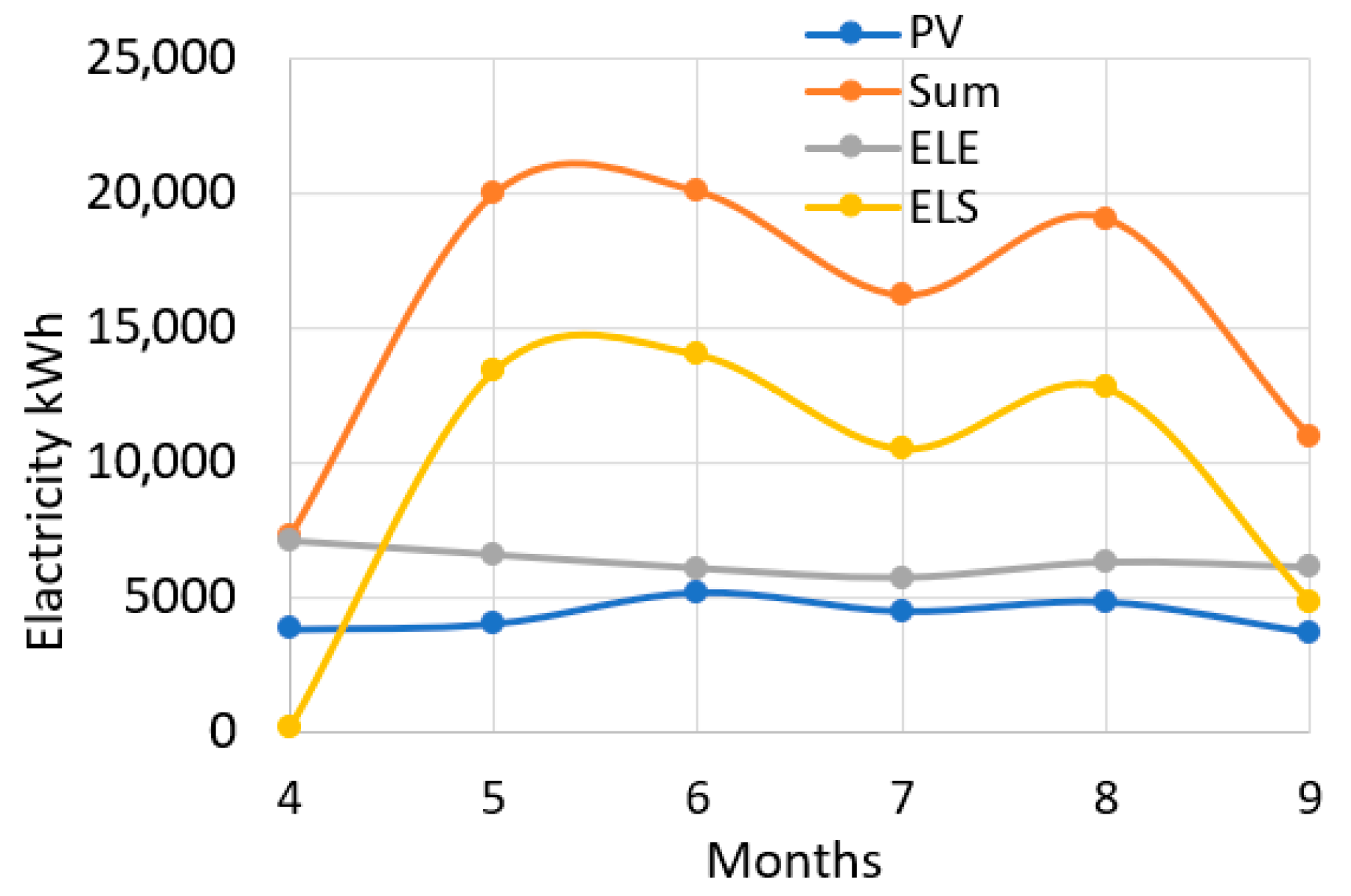

Appendix A presents the monthly electricity demand of the IKAR dormitory under consideration. The Sum line represents the dormitory’s electricity demand during each of the twelve months of the assumed annual period. The ELE1 line represents the electricity demand for the IKAR dormitory’s student rooms. On the other hand, the ELE2 line illustrates the demand for the IKAR dormitory’s service spaces, including the gas heating system equipment. Therefore, Sum is the sum of the ELE1 and ELE2 demand over the subsequent months of the entire year.

Figure 3 shows the electricity production from the panels mounted on the façade of the IKAR student residence hall. The electricity production began in April 2025, i.e., in the fourth month and is measured in the subsequent five months until September. The PV line represents the electricity produced with PVI arranged on IKARS’s south-eastern façade. This line presents an electricity production of 23.5∙10

3 kWh over 5 months. Crystalline silicon PV panels with a power of 50 kWh, system loss of 14%, angle of incidence up to 4°, and a total surface area of 250 m

2 were mounted vertically to the wall in the form of two large rectangles, as shown in

Figure 1b. The final sum of the obtained losses does not exceed 23% if the panels are well maintained.

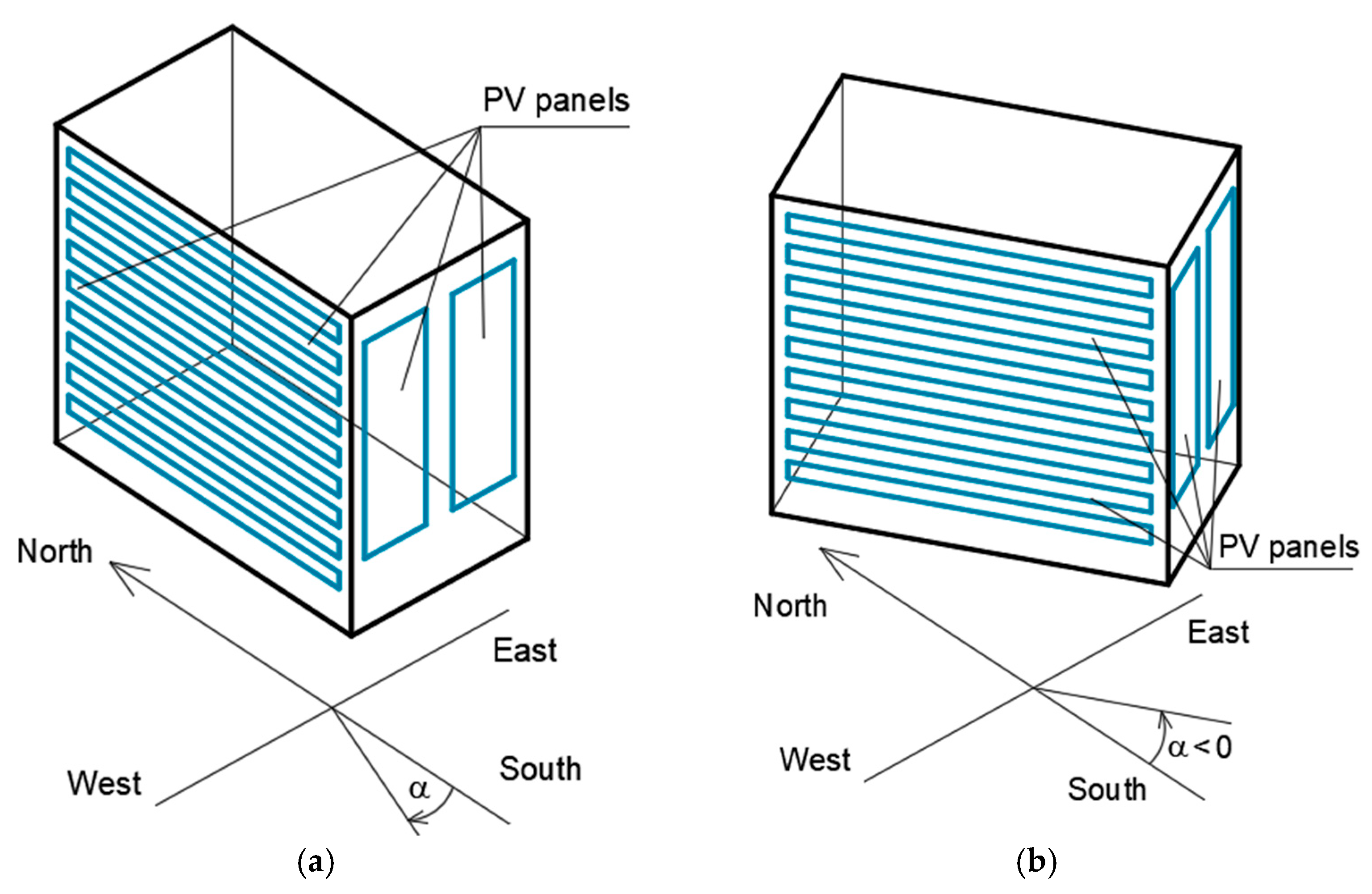

Figure 4a presents a geometric parametric model of a multi-story student residence hall modernized with a PVI distributed as horizontal strips on the western façade and as two large vertical rectangles on the southern façade.

Figure 4b shows an identical model of the building with a vertical PV installation, but its azimuth is negative, which results from the rotation of the model, as shown in

Figure 4a, by an angle α, the measure of which is negative.

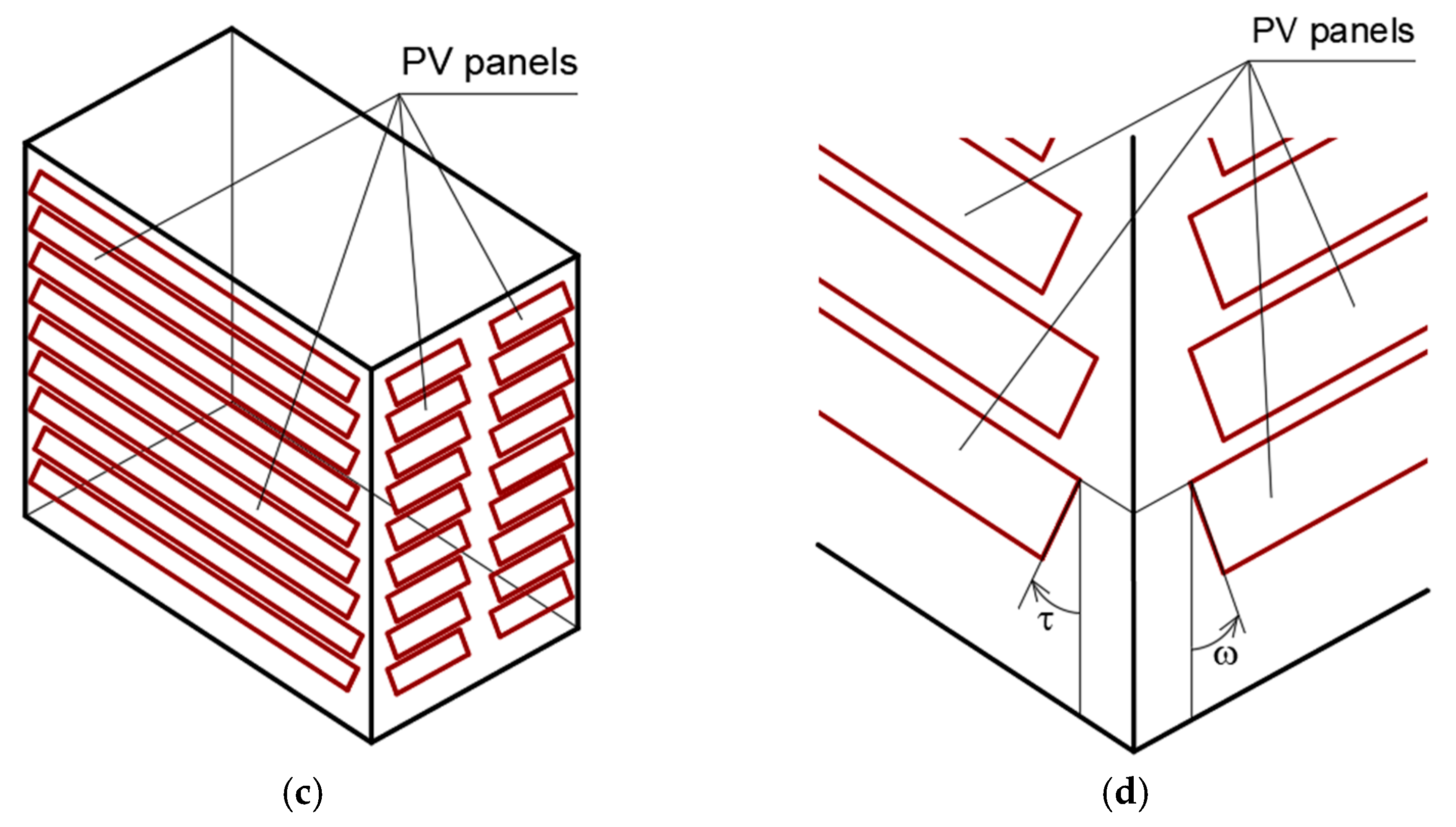

A model of the building with panels inclined to the vertical is shown in

Figure 4c.

Figure 4d presents a detail of the inclination of PV panels on the south-west façade, where the angle of inclination of these panels to the vertical is τ. This figure also shows details of the inclination of PV panels on the south-east façade, where the angle of inclination of these panels to the vertical was denoted as ω.

The angles τ and ω of the PV panels’ inclinations to the vertical and the total surface areas of these panels define four independent variables Xi (i = 2 to 5) of the M

pg model. The fifth independent variable X1 is defined by the angle α, as shown in

Figure 4b.

To define a qualitative parametric output model M

pe, eight output parameters Yj (j = 1 to 8) were adopted as shown in

Figure 2. Their values describe the state of a building after modernization. These dependent variables Yj (output parameters) are related to the following: Y1—the purchase and installation costs of PVI; Y2—the payback period of the modernization investment; Y3—the total surface area of PVs mounted on the south-facing façade; Y4—the total surface area of the PV panels mounted on the east-facing façade; Y5—the total cost of constructing 1 m

2 of the PVI; Y6—the amount of electricity produced from the PVI in kWh; Y7—the amount of electricity from the grid replaced by electricity produced with the PVI; Y8—the price of the net energy replaced by that produced by PVI during the year.

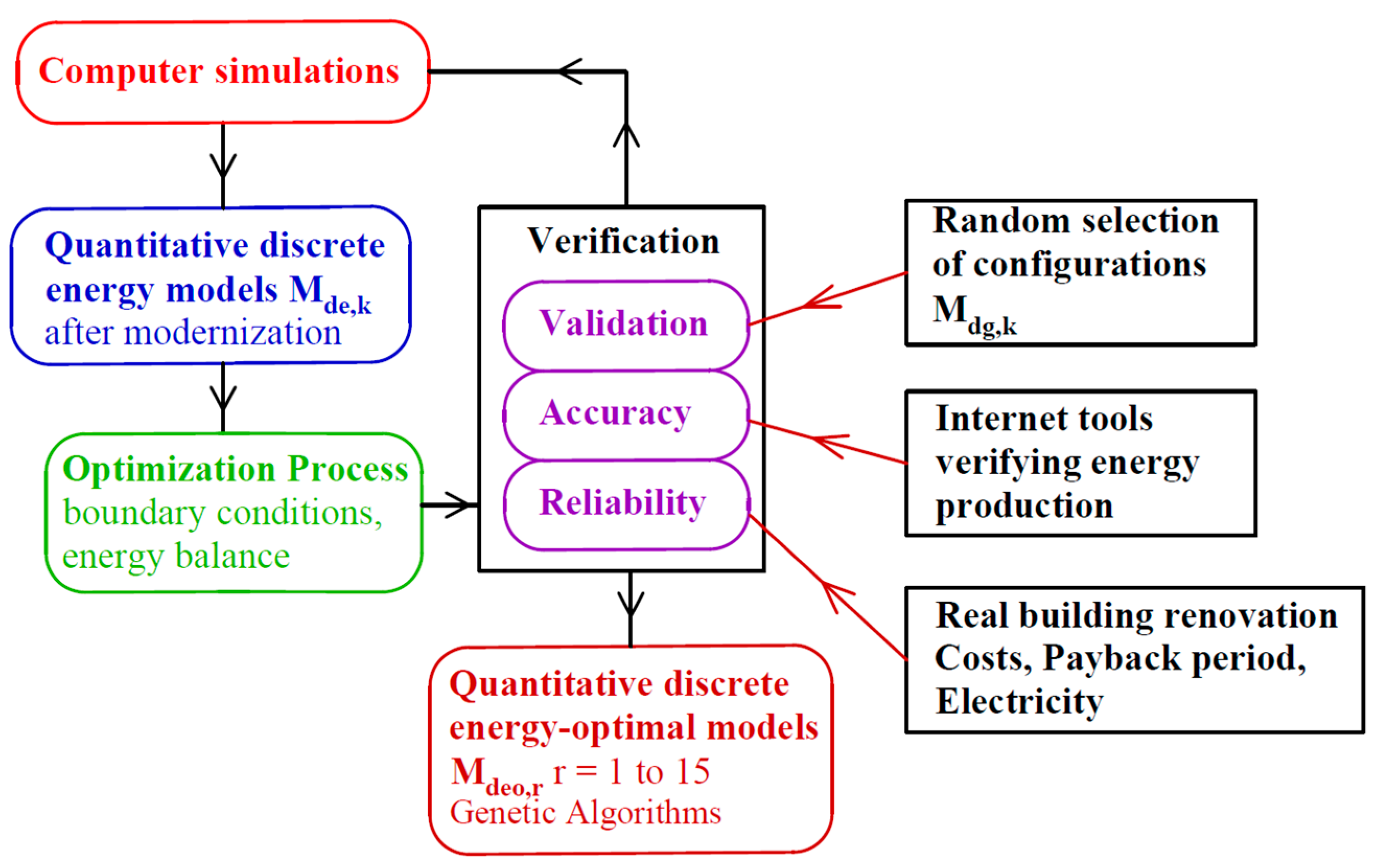

To be able to create different models of renovated buildings, optimized for electricity production, r = 15 simulations were executed with different cost conditions determined by variables X6 to X8. Sets {Xi} (i = 1 to 8) of values of Xi selected from the assumed variability ranges, defining the M

dg,k models, were adopted as the input data for the simulations: see

Figure 2. In total, r = 15 sets {Yi} of values were obtained of eight dependent variables Yj defining the discrete optimal M

deo models of buildings after renovation and constituting the output data. The performed computer simulations allowed for a few main relationships between variables Xi and Yj (between the Mpg and M

pe models) to be defined. They led to fifteen discrete optimal M

deo models of buildings after renovation, corresponding to the adopted sets {Xi} as shown in

Figure 2.

The optimizing condition employed in each iterative simulation was based on a balance of the energy produced by PVI and the grid energy being replaced. By comparing the portion X6 of the energy Etot supplied with the grid with the energy Y6 produced by the designed PV panels, one can calculate the values of the individual variables Xi using Equation (1). This condition was implemented in the proprietary computer application. It guarantees that the adopted optimizing condition is met. At this step of comparison (electricity energy balances), it was assumed that the relative annual increases in the prices of materials, labor, and energy are identical; and inflation and discounts are not taken into account.

where Y7 is calculated in each iteration to obtain the optimal value at the end of each optimizing process.

The costs of purchasing and fixing the PVI can be calculated using Equation (2)

where Y3 and Y4 are calculated in each iteration and their optimal values are saved at the end of each optimizing process.

The annual cost Y8 of the electric energy Y7 replaced by the energy Y6 produced by the PV panels can be calculated using Equation (3).

The payback period Y2 can be calculated using Equation (4).

where Y2 is measured in months.

The calculations concerning the building’s modernization included the portion of electricity used for equipment and service of the building, excluding the energy generated by gas combustion and used for central heating. The variable X6 was used to define the portion of electricity supplied with the grid before modernization, that is to be replaced by energy produced by the new PVI.

Based on the solar irradiation of PV panels, obtained from the files available on publicly available websites, and the panel efficiency, the amount of energy produced by 1 m2 of these PV panels was calculated with the proprietary application. In the parametric analysis, the price X7 of 1 kWh of electricity supplied with the grid was assumed at three levels in Polish currency known as PLN. It has been assumed that EUR 1 is worth PLN 4.3. The payback period Y2 of the modernization costs Y1 was calculated.

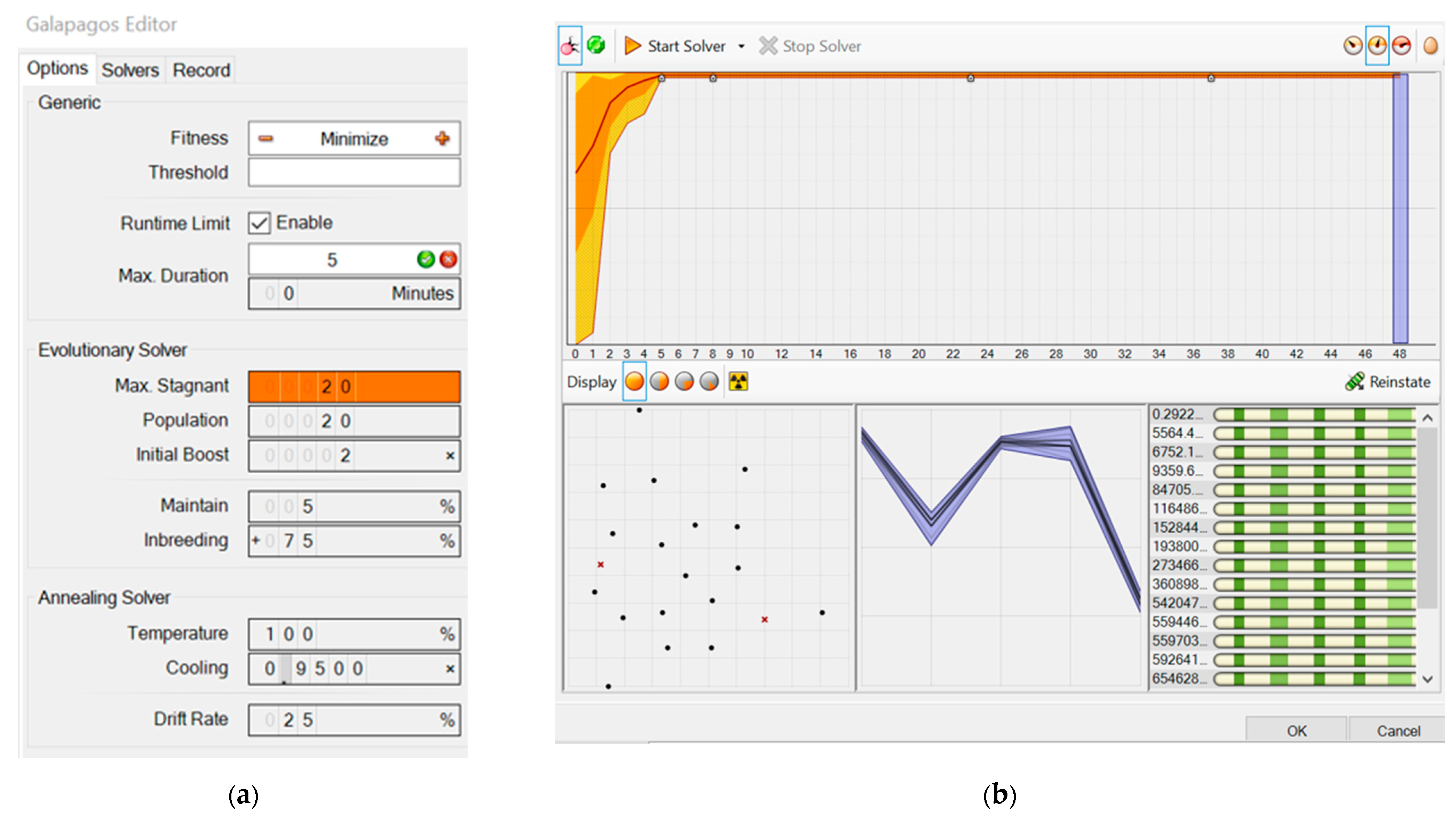

The input and output models before and after renovations, simulations, calculations, and optimizing processes were produced using the Rhino/Grasshopper program [

31], which allows for parametric programming and optimizing using graphical objects called containers and wires. To perform a number of computer simulations and obtain the optimal result, iterative calculations were conducted as a single optimizing process using a genetic algorithm implemented in the Galapagos container, as shown in

Figure 5, using the above-mentioned objects. Each iteration process was terminated when the appropriate calculation accuracy was achieved. To this end, the genetic algorithm searched for the minimum value of the difference between Y6 and X6 ∙

* Etot, the square of which should fall within the range of calculation accuracy that was assumed at the level of 0.1%.

The qualitative parametric model M

pe used to create the optimized models M

deo,r during the simulations was validated using online tools available on the European Commission website [

32]. To increase the robustness of the models M

deo,r, the real-world values used during the energy renovation of the IKAR student residence hall located in Rzeszów were also utilized, with the overall dimensions shown in

Table 1. These dimensions were adopted for the models employed in the simulations. Similarly, the characteristics of the PV panels under consideration were identical to those in the real-world modernization of the above-mentioned student residence hall.

5. Simulation Results and Their Analysis

Fifteen computer simulations were conducted to obtain fifteen optimized models M

deo,r of the modernization process of a multi-story student residence hall by distributing PVIs on two façade walls. Fifteen different sets of values of the input parameters {Xi} were used in these processes, as shown in

Table 3. Three values for each variable X6 to X8 were selected as input data in each optimizing process (each r simulation; r = 1 to 15) so that the middle value corresponds to the value used during the real renovation of the IKAR dormitory. The values of variables X1 to X5 were selected from the assumed ranges by the genetic algorithm in each iteration of a single optimizing process, which in the final step provided these optimized values. They are given in columns two to six. The test ranges of all independent variables were defined by the limiting values of these parameters given in

Table A1 in

Appendix A. The first column of

Table 3 presents the symbol of the model defined with the help of X1 to X8, whose values are the result of a single simulation.

The resultant models M

deo,r (r = 1 to 15) were defined by fifteen sets {Yj} of the dependent variables Yj calculated in each optimizing process, whose values are shown in

Table 4. Columns four and six provide the total surface area of the PV panels on two façades. Column six shows the cost of constructing 1 m

2 of PVI. Columns seven and eight present the amount of energy produced by the respective PVI and the grid energy being replaced. The equality of these values in each row demonstrates the accuracy achieved by meeting the optimizing condition. Column nine provides the annual profits resulting from replacing the grid energy.

In each optimizing process, iterative calculations and one optimization were performed using the Galapagos application of the Rhino/Grasshopper program [

31]. The interface (internal input menu) of the Galapagos application based on genetic algorithms is shown in

Figure 6. The Max Stagnat option indicates the maximum number of generations without fitness improvement. Population indicates the number of individuals in each generation. Initial Boost defines the number of individuals generated randomly in the first phase of calculations. Maintain determines the probability of mutation. Inbreeding defines how similar individuals are during crossbreeding.

The simulation results were the basis for defining several relations occurring between the parametric input model M

pg(Xi) and the parametric output model M

pe(Yj). These relations led us to configure each quantitative discrete energy model M

deo,r selected as the most efficient among all the models M

de,k obtained in each optimizing process using the genetic algorithm implemented in the Rhino/Grasshopper program. The fifteen most effective models M

deo,r were created as a result of fifteen optimizing processes, where Equation (1) was the optimizing condition in each process. Based on these models, a few novel relations are presented in the diagrams shown in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 presented below. The presented diagrams were created using Excel [

33].

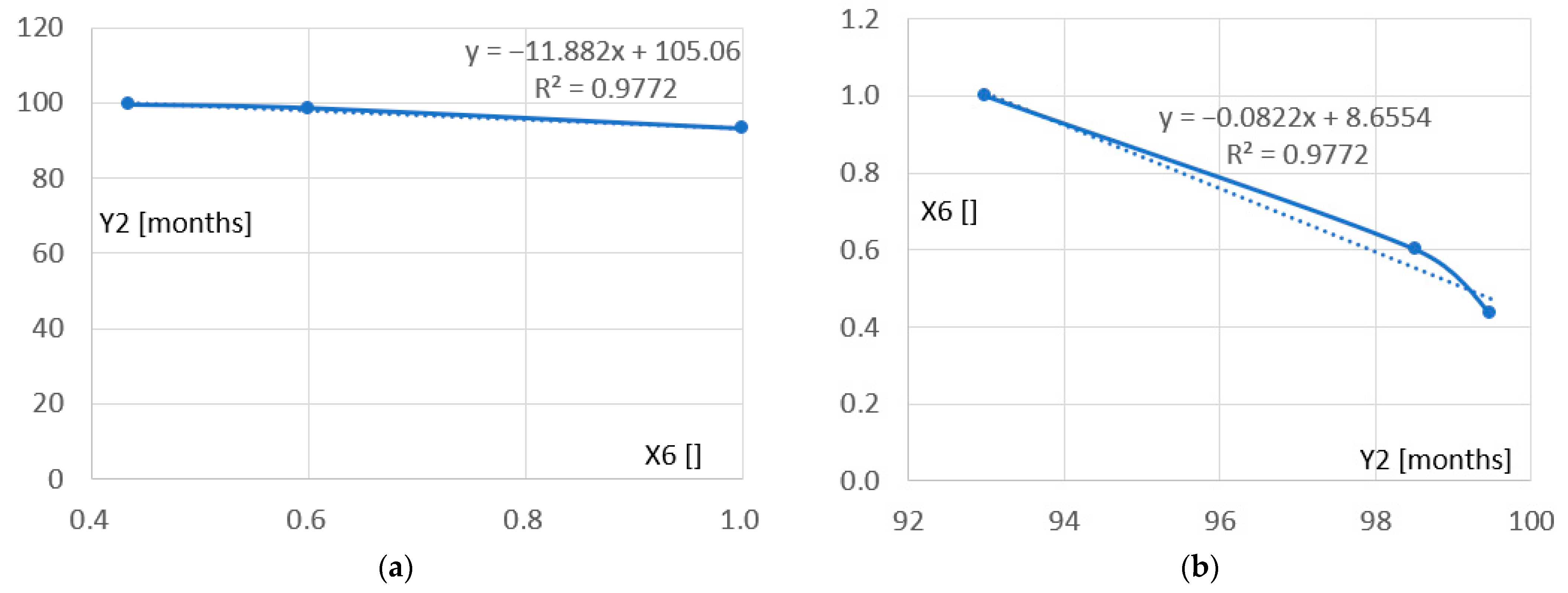

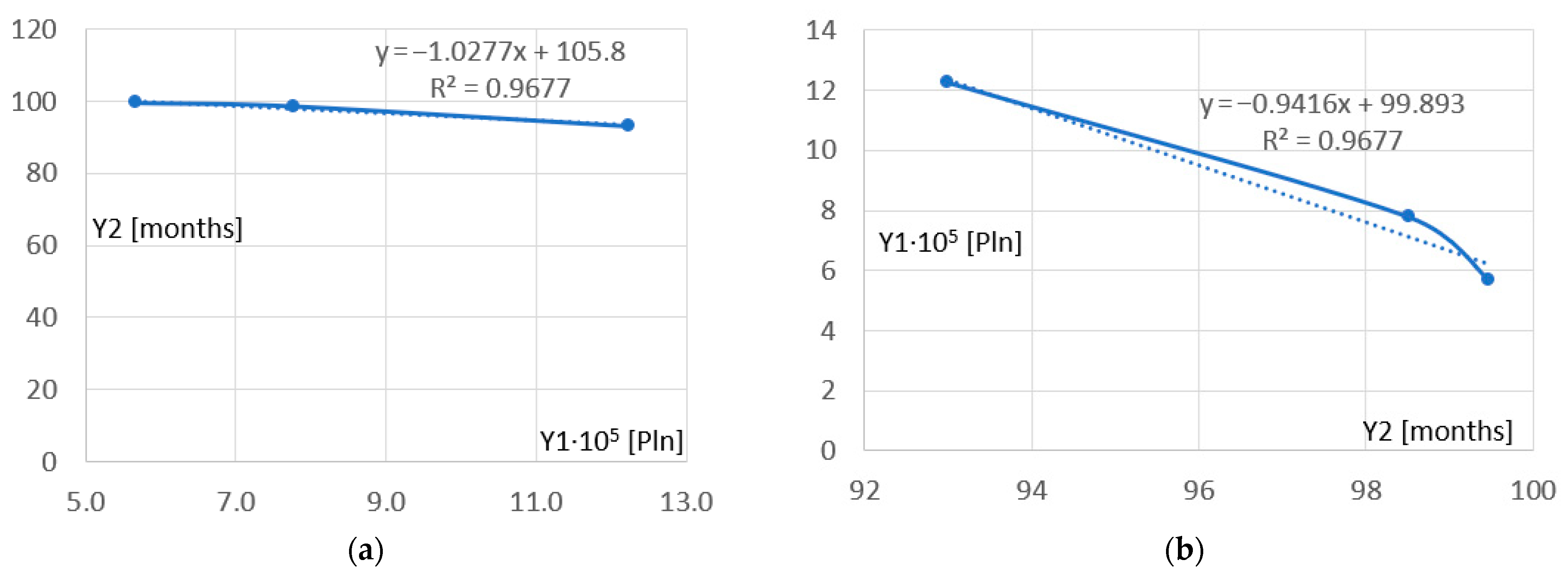

Figure 7a presents a relationship between the independent variable X6 of the M

pg model and the dependent variable Y2 of the M

pe model. This relationship is one of the relationships constituting the sought-after final quantitative parametric model M

deo. The line presented in this diagram shows a non-linear relationship between the payback period Y2 and the electricity X6 supplied by an external grid during the year and replaced by the electricity produced by PVI. This relationship is close to linear at a significance level of

p < 0.05 with a relatively large explained variance of R

2 = 0.9772, making the diagram useful in engineering applications.

The non-linearity of the relationship between X6 and Y2 can be seen in

Figure 7b, where the values of Y2 are measured along the x-axis and the corresponding values of X6 along the y-axis. The difference in the curvatures of the above curves results from the different absolute value ranges of X6 and Y2. This difference can be standardized by normalizing these values. However, this is beyond the scope of this article and will be performed during broader future activities related to various building renovations.

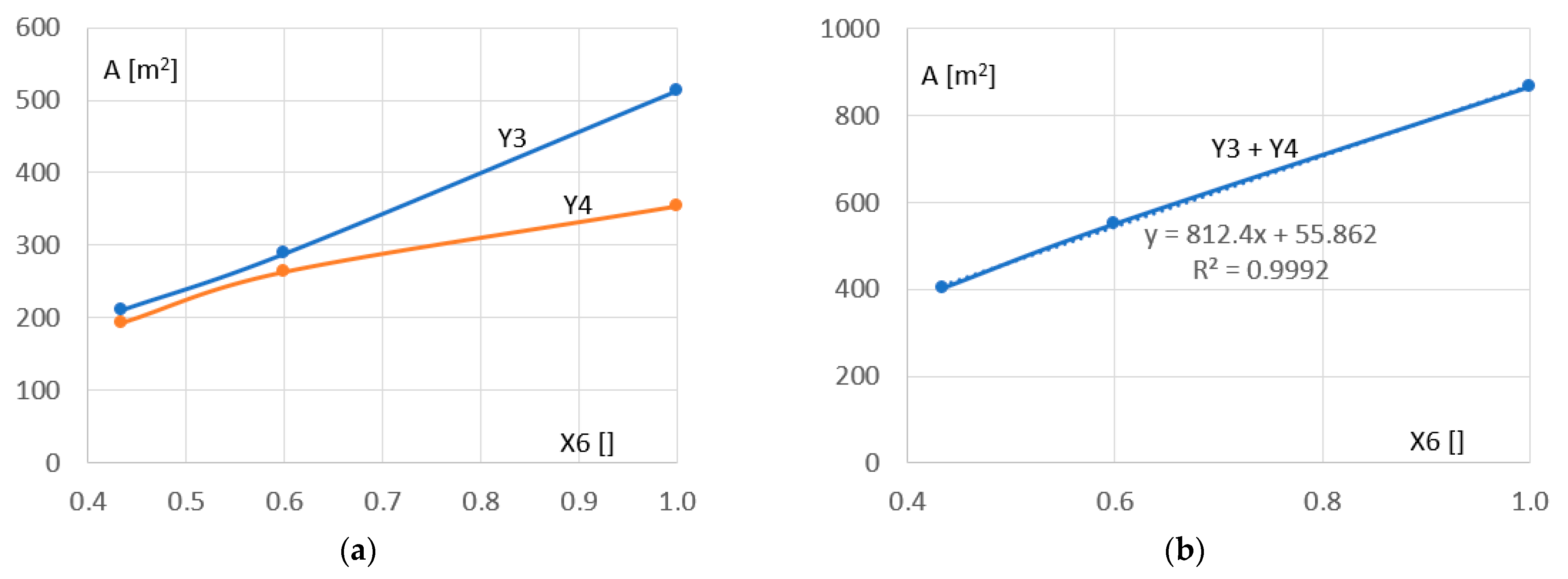

Figure 8a shows two curves Y3 and Y4 representing two relationships between the surface area of PV panels on each of two south-facing and east-facing façades and the production of electricity with PVI. These relationships are non-linear; however, if we consider the total surface area of PV panels (referring to Y3 and Y4), then the relationship is linear, as shown in

Figure 8b. This implies that if we want to effectively increase the share of the grid energy with the energy from the PV panels, we need to increase the surface area of the PV panels on the south wall more than that of the PV panels on the east wall, with a –30° optimal building azimuth.

The diagrams shown in

Figure 9a,b and

Figure 10a,b are analogous to those presented in

Figure 7a,b. Each of the lines presented in

Figure 9a,b indicates a non-linear relationship between the costs Y1 and the payback period Y2 of the modernization investment by the respective optimizing and boundary conditions. It can be seen that as the modernization costs Y1 increase, the payback period decreases, although the change is not very large and concerns a maximum of 6 months for r from 1 to 9, where the value of X8 did not change.

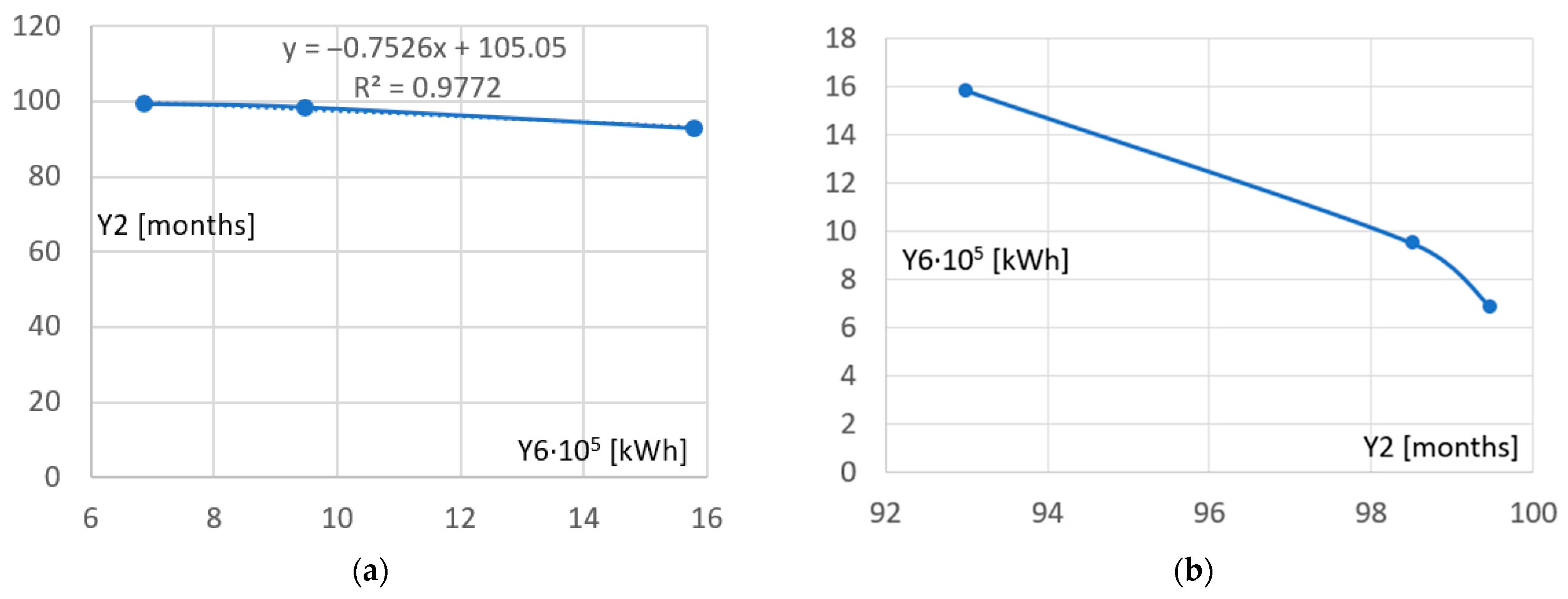

The two lines shown in

Figure 10a,b indicate non-linear relationships between the amount of energy Y6 produced by the respective PVI and the payback period Y2. It can be seen that with the increase in electricity production, Y6, the payback period decreases.

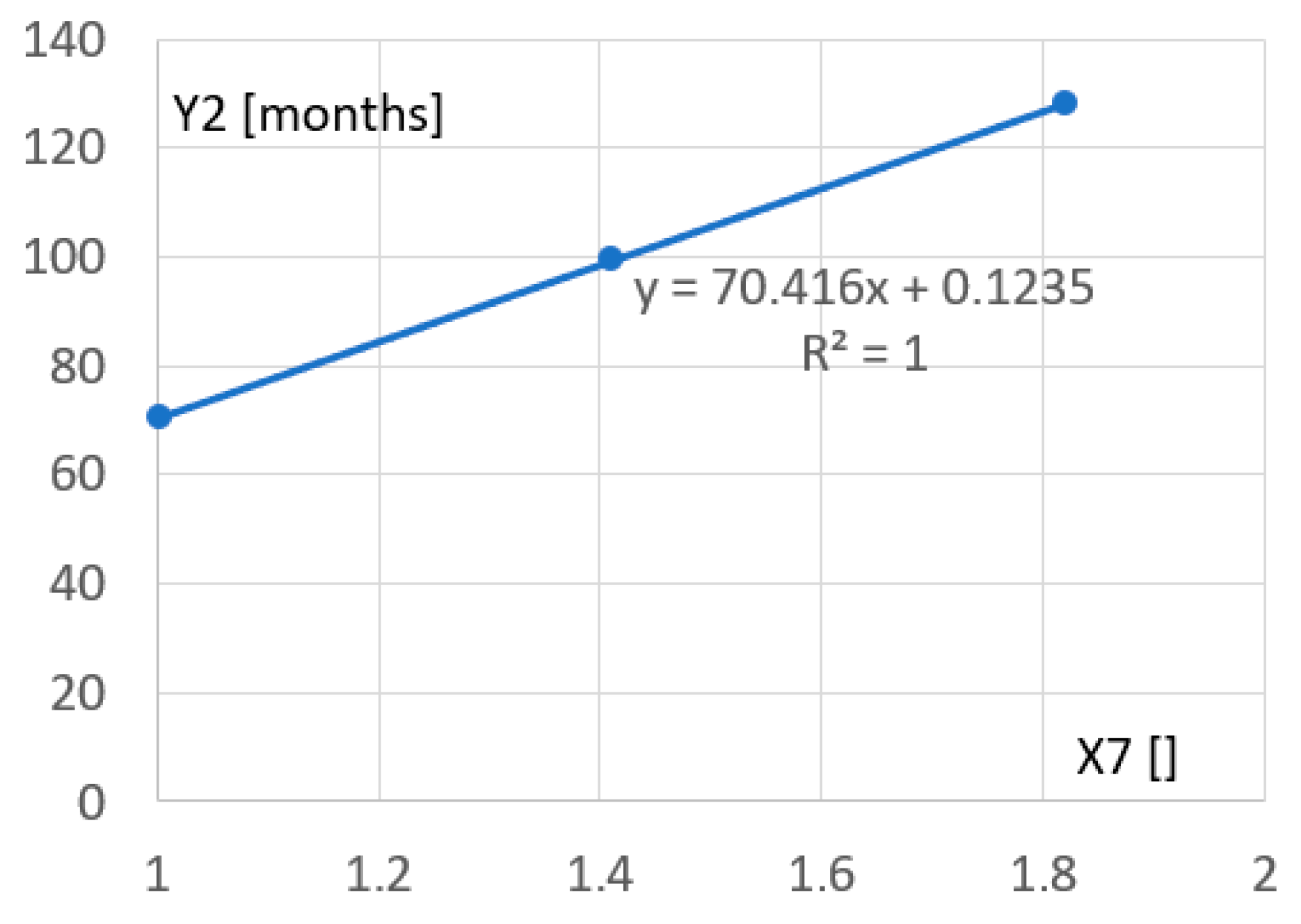

As shown in

Figure 11, there is a strongly linear relationship between the ratio X8 of the cost of purchasing and fixing 1 m

2 of PV panel surface with the price of 1 kWh of electricity supplied by a grid multiplied by 1000 using Equation (2). This relation shows that if the costs of PVI increase or the prices of net energy decrease, then the payback period significantly increases up to two times with relatively reasonable cost changes.

6. Discussion

Because the fifteen optimizing processes resulted in both the south-facing and east-facing façades having to be involved in the PV panel arrangement, the panels on one façade and others on the second façade produced greater electricity depending on the time of the day and the season. The diversification of the X4 and X5 angles of inclination between the PV panels and the respective façade was also necessary to obtain the most effective result in terms of optimal electricity production.

Analysis of the simulation results and optimizing processes revealed that the optimized relationships found between independent and dependent variables can be linear and non-linear. The achieved relations allow for further economic optimization of building modernization to be carried out based on the payback period. The diagrams presented in the previous section indicate that the optimal solution is to adopt shorter payback periods, which indicates greater initial costs of the predicted renovations, as shown in

Figure 8a,b and

Figure 9a,b.

A drastically greater variety of possible renovations of multi-story student residence halls shall be achieved by considering a number of effective solutions instead of considering one optimal solution Mdeo,r. The parametric models and the method presented in this article can also be employed to define a number of effective diversified parametric resulting models for which various optimizations and boundary conditions can be set. The new conditions should lead to a selection of several diversified effective solutions. In addition, the parametric process of searching for many solutions similar to each other requires the use of statistical procedures such as correlation, linear regression, and non-linear estimation or artificial intelligence including neural networks. The authors anticipate a number of solutions to these issues in the near future.

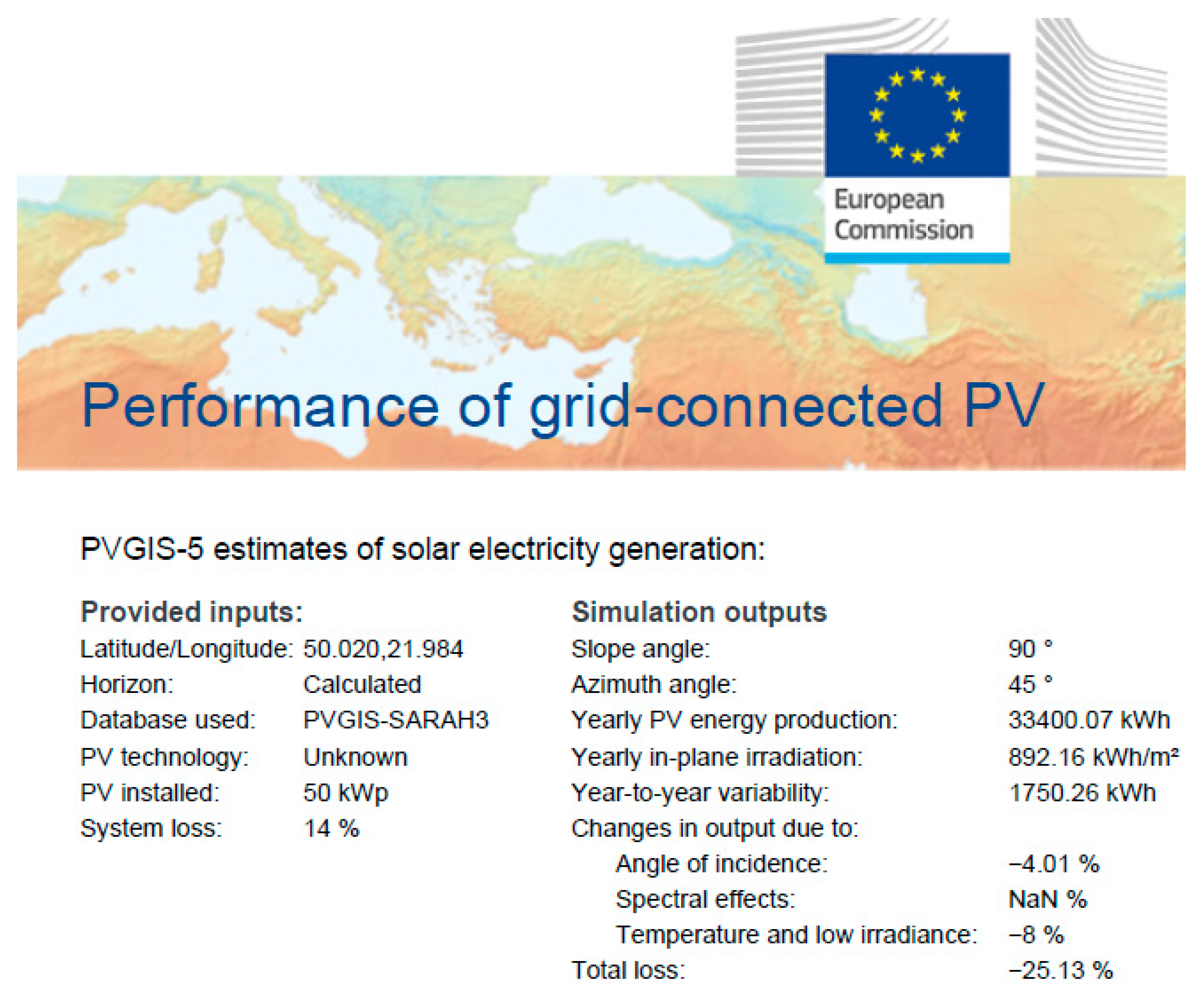

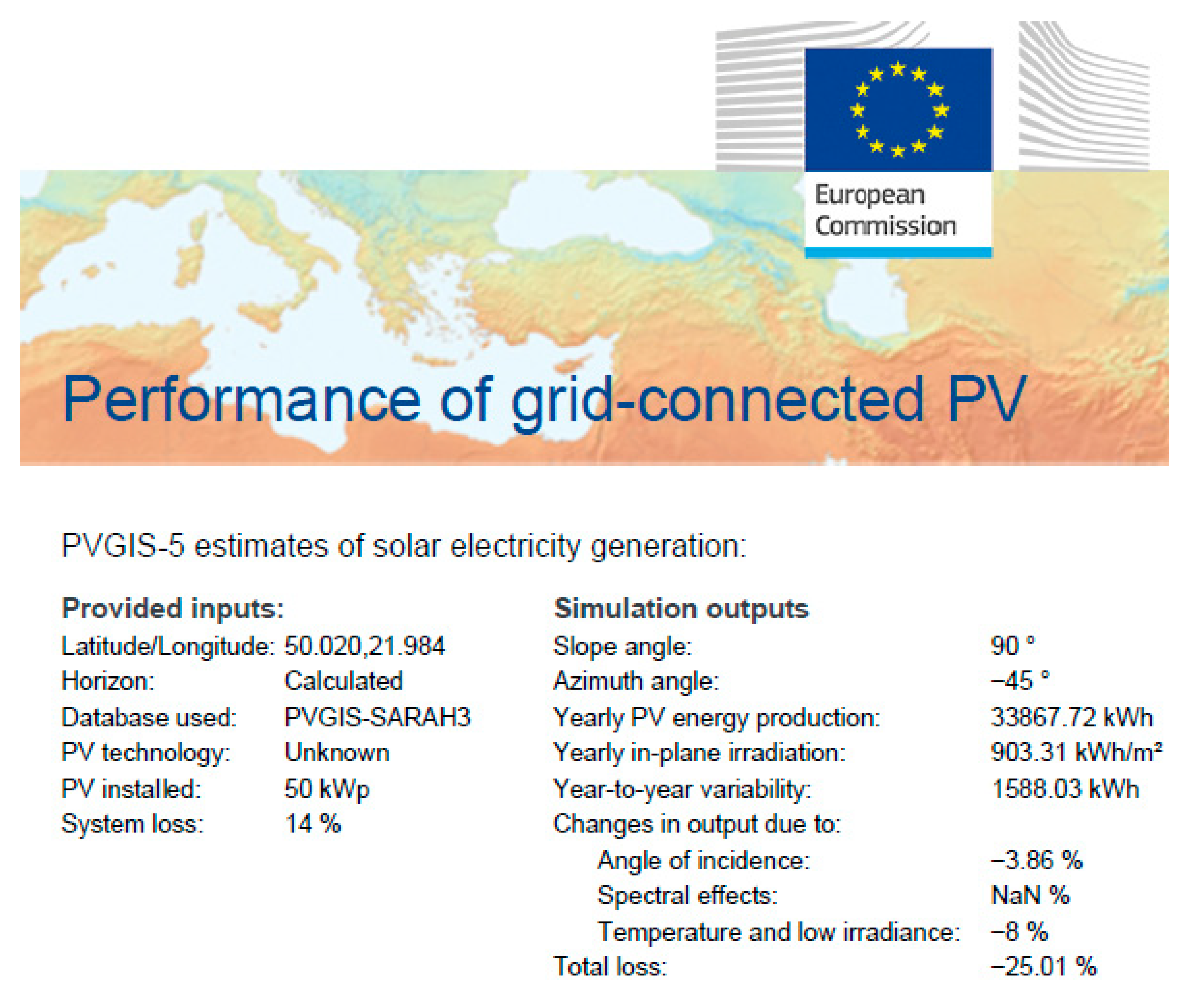

Comparison of the parametric results obtained automatically using several Rhino/Grasshopper procedures with the discrete results calculated for vertical panels using the European Commission’s online tools leads to the conclusion that they are within the accuracy range required by the European Commission (EC) [

32]. The results of annual production calculations using these online tools for the south-east façade of the IKAR student residence hall are presented in

Figure A2 in

Appendix A; the results for the south-west façade are shown in

Figure A3 in

Appendix A. For the selected discrete photovoltaic configurations, the accuracy between 591 and 457 kWh was calculated using the online tools. However, the accuracy required by EC due to weather variability is 1850 kWh for south-eastern façades and 1896 kWh for south-western façades.

For the real student dormitory considered in this article and located in Rzeszów, the electricity production using PV panels was assumed to be at the level of 33,900 kWh for the south-eastern façade and at the level of 33,400 kWh for the south-western façade of this dormitory in accordance with EC guidelines [

32]. In this case, the calculated optimal payback period was equal to 99.5 months for typical modernization costs. The key discrete results calculated for the most effective three models M

deo,r are presented in

Table 5.

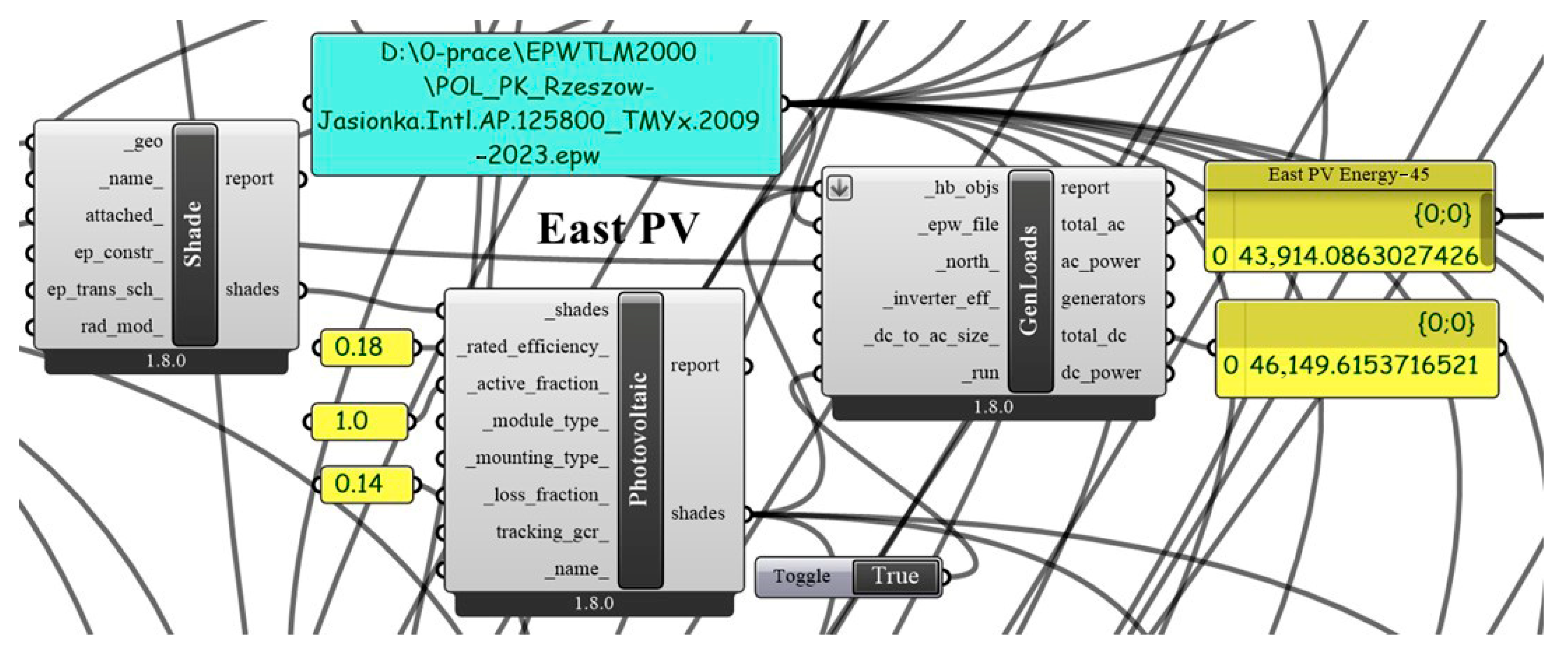

An example of a code fragment of the proprietary application in Rhino/Grasshopper is presented in

Figure 12. This fragment concerns shaping the geometry of the PV panels (Shade module), PVI configuration (Photovoltaic module) and electricity production (GenLoads module). The files containing meteorological data were automatically downloaded from the dedicated websites, and then opened using an internal module. The Evolutionary Solver of Galapagos was employed to perform the optimizing calculations. The configuration parameters of the Galapagos program were determined and their values are presented in

Figure 5.

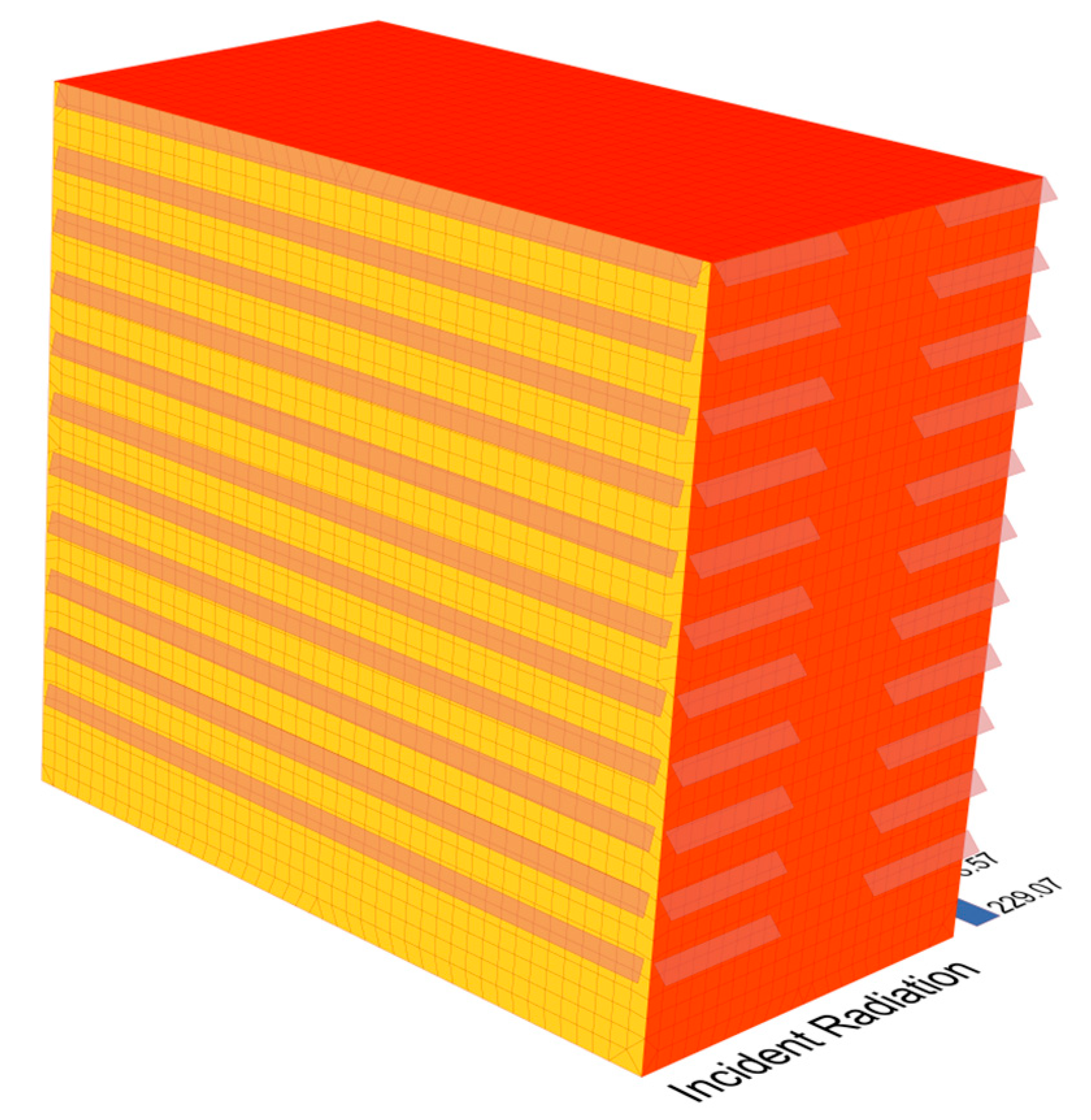

A simplified model of the examined real dormitory IKAR determined with the proprietary novel application in Rhino/Grasshopper is presented in

Figure 13.

M. Asif et al. [

22] pointed out that economic aspects are the most important in ranking of priority variables related to the modernization of residential buildings with PVI. Therefore, the current study presents the cost calculation, too. V. Shekar et al. [

26] showed the crucial importance of minimizing economic costs using an increased function of PVI. The current study shows the impact of changes in energy, material prices, and construction costs on PVI’s costs and payback period of modernization investments.

In the present study, a payback period of 66 to 128.3 months was analyzed. It is consistent with the payback periods predicted by other authors. L. Tao et al. [

15] indicated an optimal payback period of 101 months for the energy of 55,961 kWh produced by PVI for multi-story residential buildings. G. Evolaa and G. Margani [

25] performed calculations with payback periods ranging from 108 to 380 months for an eight-floor apartment building. P. Bakmohammadi et al. [

27] achieved a return on investment after 370 months of operation of PVI producing 1307 MWh. M. K. Ansah et al. [

30] analyzed an effective building modernization with a payback period of 60 months.

In the current article, varying energy production with PV panels ranging from 43.4% to 100% was taken into account. V. Shekar et al. [

26] proposed a grid energy substitution of 45%. In the case of the analysis conducted by H. Wu et al. [

28], the minimum substitution factor was approximately 70% and the maximum 90%. A. Young-Sub et al. [

23] offered calculations leading to a grid energy substitution of 45%.

7. Conclusions

An automated process of modernization of multi-story student dormitories located in temperate climate was defined to optimize the energy delivered with external nets to meet the current needs related to internal and external equipment. This process was based on proprietary computer simulations using several innovative models. In particular, this automation involved novel iterative calculations performed with the help of the novel proprietary Rhino/Grasshopper application related to the following: (1) creating a qualitative parametric input model of the modernized building, defined by eight independent variables Xi (i = 1 to 8), (2) defining new multiple quantitative discrete input models of the modernized buildings by assigning specific values to Xi, (3) simulating the energy performance of the above discrete models equipped with PV panels, (4) obtaining novel discrete quantitative output models as a result of the original computer simulations, defining discrete states after modernization, and (5) creating a qualitative parametric output model defined using a number of the dependent variables Yj describing the energy and costs of modernization of student dormitories. Finally, the resulting optimal quantitative model of dormitories after modernization was shaped, meeting the assumed boundary and optimizing conditions.

The calculated optimal modernization of the student dormitory was obtained for the following values of five geometric independent variables Xi: the azimuth X1 equal to −30°, the quotient of the PV panel area to the surface of the southern façade X2 equal to 0.176, the quotient of the PV panel area to the surface of the eastern façade X3 equal to 0.295, the angle of inclination of the PV panel planes to the plane of the southern façade X4 equal to 14°, and the angle of inclination of the PV panel planes to the plane of the eastern façade X5 equal to 42° assuming that the remaining independent variables related to the prices and costs of individual modernized elements are identical to those incurred for the real modernization of the dormitory. The final cost of the designed photovoltaic installation was PLN 112 074. The total electricity supplied to the real dormitory was equal to 68,490 kWh. The calculated payback period was 99 months and 15 days.