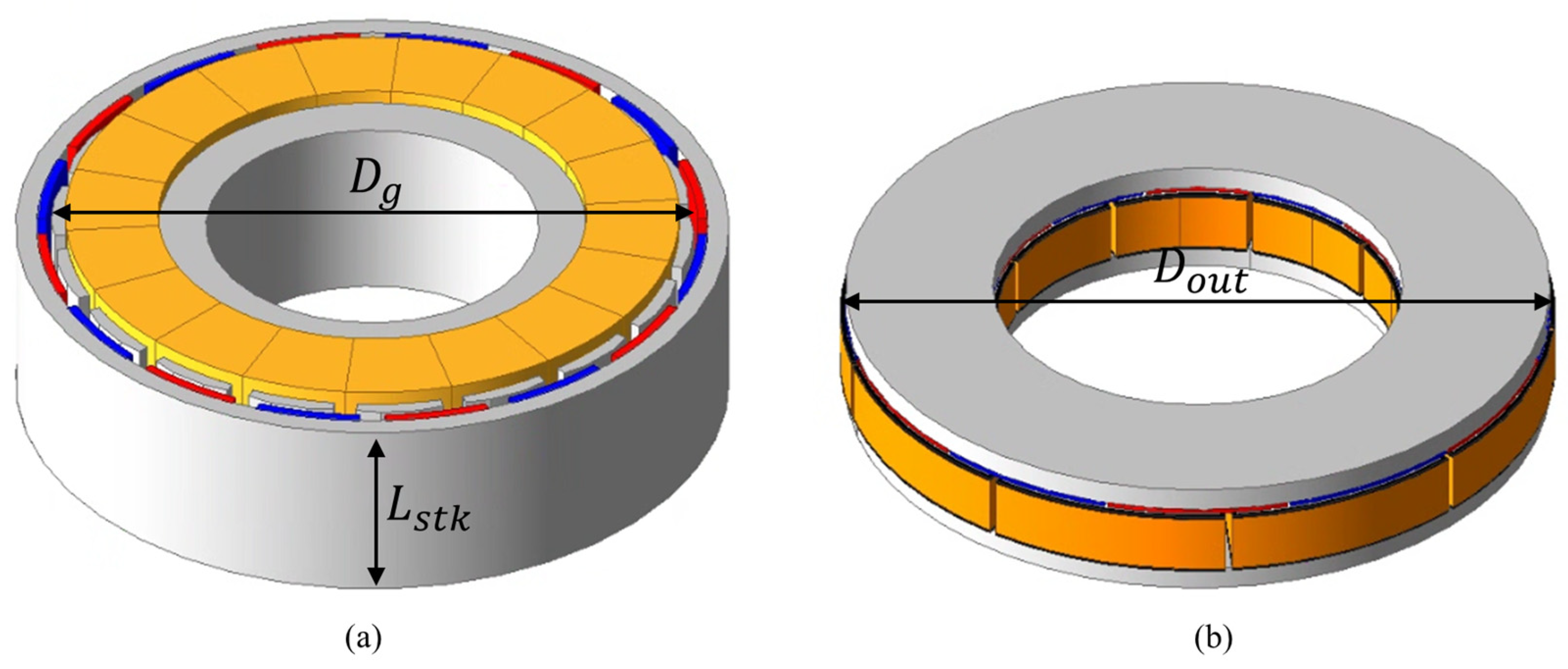

The in-wheel motor for the AMR has its entire drive system housed within the wheel, which restricts dimensional changes during design. The motor’s outer and inner diameters must be fixed to match the wheel structure and the internal drive system. This means that the outer and inner diameters of the end turns must also remain fixed in the AFPMSM design.

3.1. Flow of the AFPMSM Design Procedure

Table 1 presents the definitions of the variables used in

Section 3.1, and

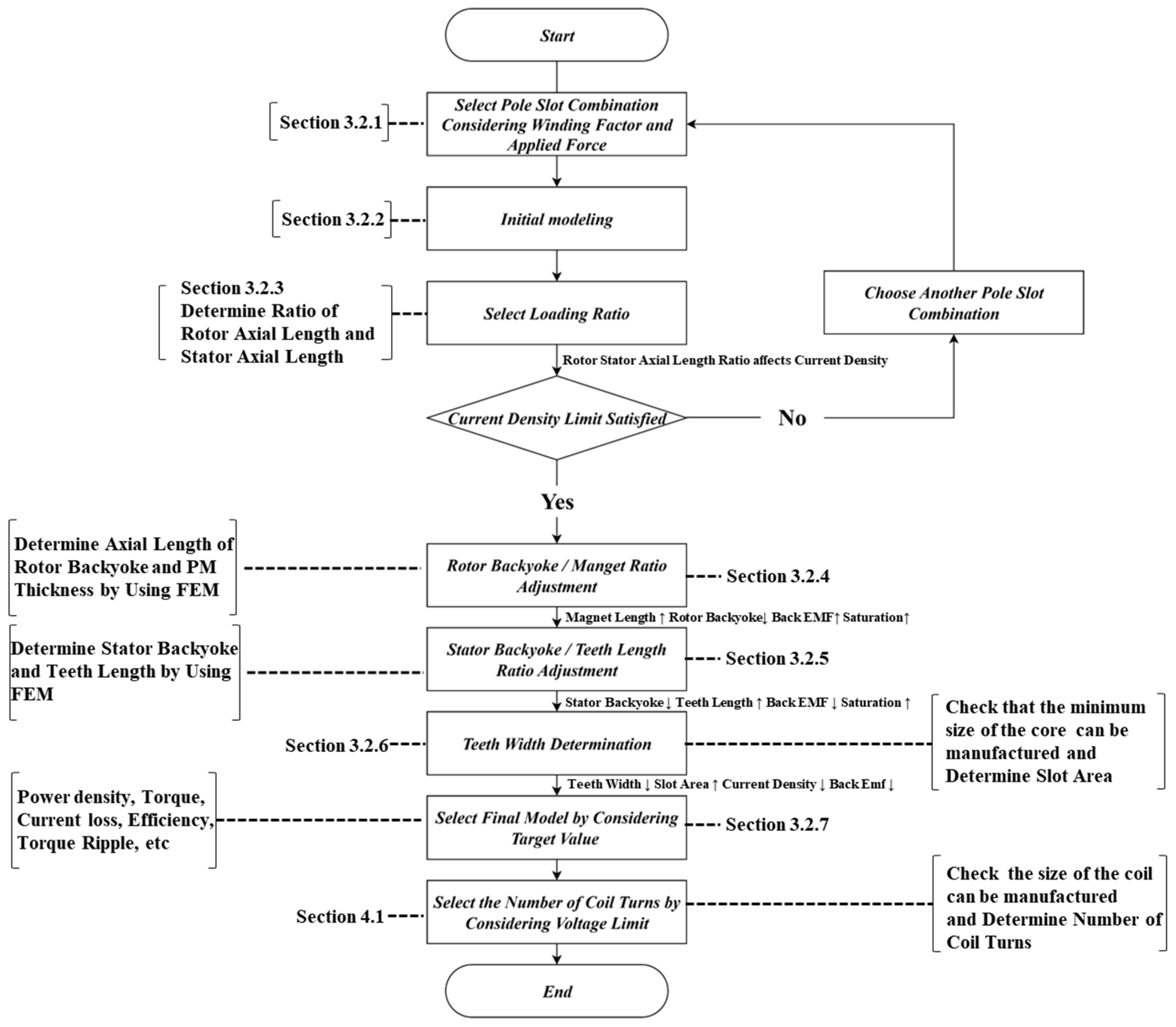

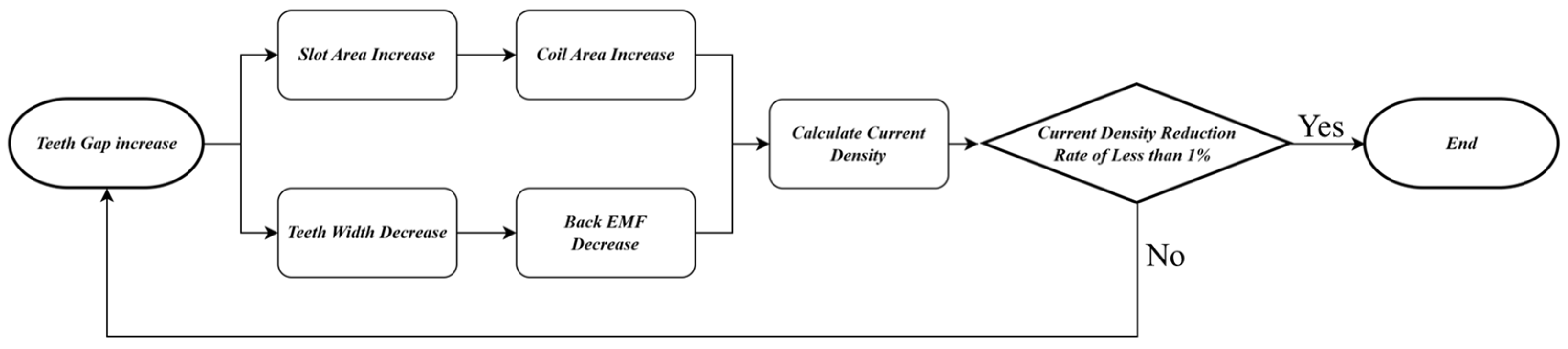

Figure 5 illustrates the AFPMSM design process. The design flow in Fig. 5 was organized to clarify the interdependence among design variables, showing how each step influences the subsequent one. The process begins with the selection of the pole–slot combination. Since the pole–slot combination influences the motor’s electromagnetic performance, control characteristics, and vibration characteristics, an appropriate combination must be selected based on the intended application. The first factor to consider when selecting a pole–slot combination is the winding factor

. The winding factor

represents the reduction in the magnetomotive force (MMF) induced in the motor due to the distribution and short-pitching of the windings. It is expressed as the product of the distribution factor

and the pitch factor

. The distribution factor

represents the ratio of the MMF produced by a distributed winding to that of a concentrated winding. When the winding forming one phase is distributed across

slots, the MMF induced in each slot decreases to approximately

of that in the concentrated winding. However, these MMFs have phase differences and combine, resulting in a composite MMF waveform that more closely approximates a sine wave. The ratio of the resultant MMF of the distributed winding to the maximum MMF of the concentrated winding is defined as the distribution factor. The pitch factor

represents the reduction in MMF of a short-pitched winding relative to that of a full-pitched winding.

A full-pitch winding refers to the case where the pole pitch and coil pitch are equal, maximizing the resultant magnetomotive force (MMF). A short-pitch winding refers to the case where the coil pitch is smaller than the pole pitch, as shown in

Figure 6, resulting in a reduced MMF compared with a full-pitch winding. Consequently, the winding factor

quantifies the overall impact on motor performance when both distributed and short-pitched windings are employed, directly relating to the electromagnetic output. Therefore, selecting pole–slot combinations that yield the highest possible winding factor is essential for applications requiring high output.

Additionally, the lowest-order radial force harmonic is also a critical consideration when selecting pole–slot combinations. Since the lowest spatial harmonic corresponding to the greatest common divisor (GCD) of the number of slots

and the number of poles P contributes most significantly to stator vibration, it is recommended to select the pole–slot combination with the largest possible GCD for vibration and noise reduction [

13]. Finally, when selecting pole–slot combinations, using a higher pole number reduces the magnetic flux per pole, allowing for a thinner rotor back-yoke. However, when the motor’s mechanical speed

[rpm] is fixed, the electrical frequency

is given by

Therefore, increasing the number of poles proportionally increases the electrical frequency

. Consequently, although using more poles is generally advantageous, the increase in

also increases the iron loss

Thus, motor efficiency and output performance deteriorate. Furthermore, as the electrical frequency increases, the inverter’s switching frequency must also increase, leading to higher switching losses and electromagnetic interference (EMI). This raises the performance requirements of the inverter and increases the controller cost. Therefore, the number of poles must be selected by comprehensively considering the combined effects of this electrical frequency increase.

After completing the selection of the pole–slot combination, the basic geometry must be determined to proceed with the design. Owing to the nature of in-wheel motors, where the drive system is integrated inside the wheel, geometric constraints such as the motor’s outer diameter, inner diameter, and axial length must be clearly defined at the initial design stage, taking into account components such as the reducer and control module to be housed internally. To begin with, the thickness of the rotor permanent magnets must be specified in accordance with the minimum manufacturing requirements. In addition, when the shoe-type stator winding method is adopted, the slot opening size must be secured to a sufficient level to accommodate this. Finally, magnetic saturation must be evaluated under the established geometric constraints using the selected pole–slot combination. This prevents nonlinear effects caused by magnetic saturation in the stator and rotor back yoke and tooth and facilitates parameter adjustments during subsequent design iterations.

After the basic geometry of the model is finalized, the ratio of electric loading to magnetic loading—that is, the distribution ratio of the axial dimensions—is determined to define the ratio of rotor axial thickness to stator axial thickness when the total axial length is fixed. To illustrate this process, the case of the RFPMSM is first explained. The air-gap flux per pole in an RFPMSM is given as

as expressed in (3), and the flux linkage produced by the total permanent magnets is

This can be expressed by (4). The magnetomotive force (MMF) in one phase is

Since the electromagnetic torque of the RFPMSM can be expressed as

where

denotes the specific electric loading, defined as the total electric loading divided by the air-gap circumference, and

is associated with the specific magnetic loading, it follows that the electromagnetic torque of the RFPMSM can be adjusted through both electric and magnetic loadings. At this stage, the electric and magnetic loadings are given, respectively, as

To convert the above relationship for the RFPMSM to the AFPMSM, the expressions for electric and magnetic loadings must be modified to account for the geometric differences between the two topologies. Accordingly, the electric and magnetic loadings are expressed as

The air-gap flux in an AFPMSM is given as

is ratio coefficient of the maximum and average values of the magnetic flux density. If you express the force acting in the direction of Equation (9) in amperes, it’s like Equation (10)

Integrating Equation (10) is as follows.

Equation (11) indicates that the torque, i.e., the output operating point, can be determined by appropriately adjusting the electric and magnetic loadings.

Figure 7 shows the geometric differences between RFPMSM and AFPMSM and the corresponding variations in parameters.

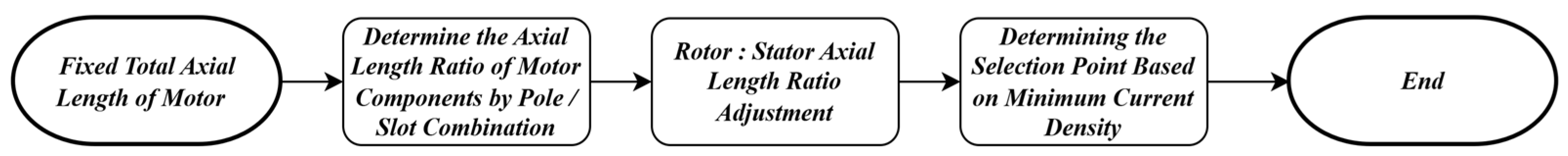

The adjustment of electric and magnetic loadings, namely the load ratio, is carried out by proportionally varying the rotor back yoke and stator back yoke with respect to the permanent magnet thickness while keeping the total axial length fixed. As the permanent magnet thickness changes, the available slot area for winding is determined; consequently, this process can be regarded as fixing the ratio of rotor axial length to stator axial length. The target load ratio is determined as follows. First, considering manufacturability, the minimum permanent magnet thickness is specified as the reference. Based on this, the stator and rotor back yokes are calculated in proportion, and the air gap is fixed. Within the limited axial length, the axial lengths of the stator and rotor are then redistributed. For each redistributed ratio, it is assumed that a winding of the same size as the slot area is wound for one turn. After analysis, the current required to achieve the target output is obtained from the no-load back EMF. Dividing this current by the slot area yields the current density, and the ratio corresponding to the lowest current density is selected. The reason for selecting the point of minimum current density is that it represents the condition requiring the least current to produce the same output, which indicates that the load ratio is most suitably distributed at this point. Through this procedure, the load ratio that satisfies the target performance with minimum current density is identified while keeping the total axial length constant by means of geometric ratio division.

Figure 8 shows the loading ratio determination flowchart used to select the rotor–stator axial length ratio corresponding to the minimum current density.

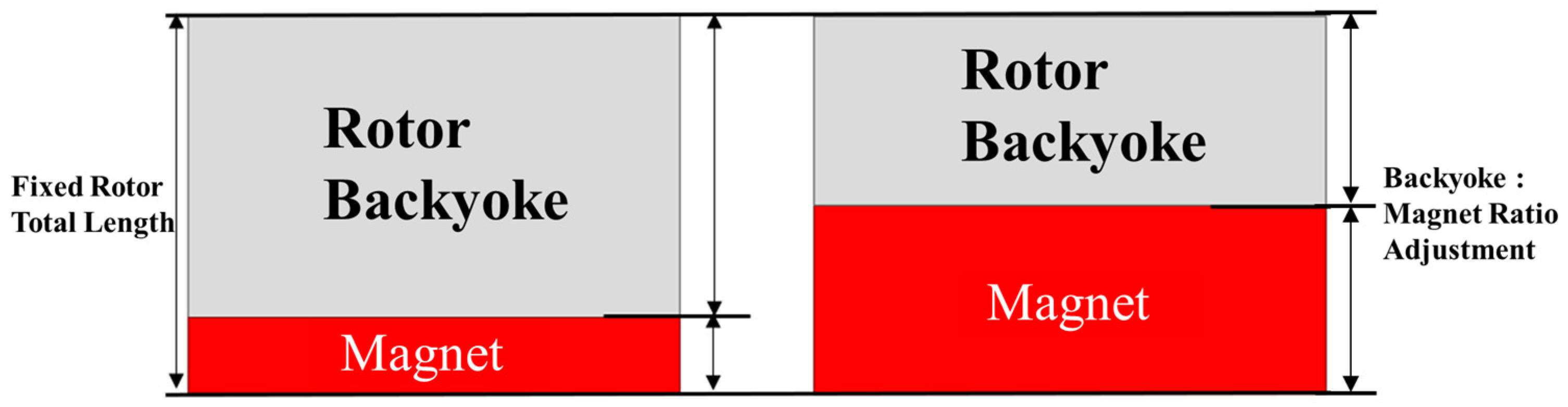

After determining the axial lengths of the rotor and stator through the selection of the load ratio, the axial dimensions are determined and fixed. Subsequently, the axial thicknesses of the rotor back yoke and permanent magnet are allocated. This approach ensures higher output capability while minimizing magnetic saturation under load. To achieve this, the thickness of each element is adjusted. The no-load back EMF for a 1-turn winding is evaluated using FEM, and the magnet thickness is determined accordingly. As the magnet thickness increases, the thickness of the rotor back yoke decreases, thereby increasing the 1-turn back EMF.

Figure 9 shows the variation in rotor back-yoke thickness with respect to permanent magnet thickness.

Since the total rotor length is fixed, the 1-turn back EMF does not increase indefinitely as the magnet thickness increases. Instead of increasing indefinitely, the iron core begins to undergo magnetic saturation, and eventually a point is reached where the 1-turn back EMF decreases. Such points are excluded from selection because magnetic saturation has already occurred even under no-load conditions. Specifically, once the rate of increase drops below 0.1%, further increases in magnet thickness no longer provide meaningful performance improvement but only intensify the effects of magnetic saturation. Therefore, the design point is defined as the first point at which the incremental increase in 1-turn back EMF falls below 0.1% as the magnet thickness increases. Through this procedure, the design ensures suppression of magnetic saturation under load while achieving the target performance within the constraint of fixed axial length.

Figure 10 shows the flowchart of permanent magnet thickness determinaition flowchart.

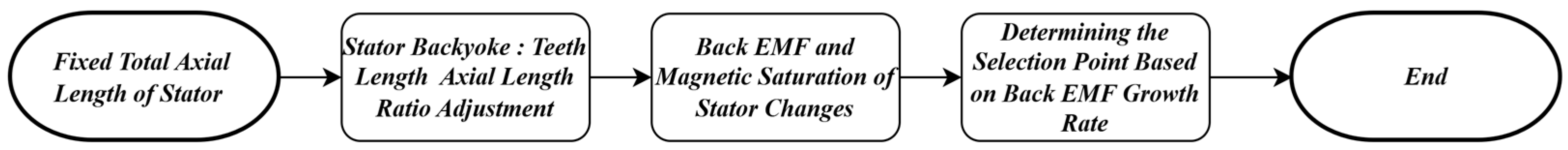

Subsequently, in the stator, the axial lengths of the tooth and the stator back yoke are distributed. This step also aims to secure output while minimizing the risk of magnetic saturation underload. As in the previous case, the distribution lengths are determined based on the no-load back EMF for a 1-turn winding. As the tooth length increases, the thickness of the stator back yoke decreases, eventually reaching magnetic saturation. At this stage, the design point is likewise defined as the point where the incremental increase in the no-load one-turn back EMF falls below 0.1%.

Figure 11 shows the flowchart of teeth length determination flowchart.

The adjustment of the tooth width of the stator is a key design element directly linked to securing electric loading in the AFPMSM. As shown in

Figure 12, reducing the tooth width increases the slot area, allowing for more winding space.

This reduces the required current density at the same voltage, thereby raising the output limit of the motor. However, due to the characteristics of the tape-wound core structure, there are physical limitations on the size of the tooth width. As the cross-sectional area of the tooth decreases, securing the magnetic flux path becomes more difficult, which reduces the magnetic flux linkage and consequently decreases output. Therefore, it is important to find a balance point between the increase in electric loading achieved by enlarging the slot area and the reduction in magnetic flux linkage caused by the decrease in tooth cross-sectional area. For each tooth width condition, a no-load FEM analysis was conducted by placing one turn of winding with the same cross-sectional area as the slot area. The current density was then calculated based on the back-EMF. As the tooth width decreases, the current density rapidly decreases, but after a certain point, the rate of reduction slows. The design tooth width was selected at the point where the current density reduction rate falls below 1%. Beyond this point, the benefits of increasing slot area are offset by the reduction in magnetic flux linkage. As a result, the selected tooth width represents a geometry that minimizes current density while also considering the need to secure magnetic flux paths and manufacturability.

Figure 13 shows the flowchart of teeth width determination.

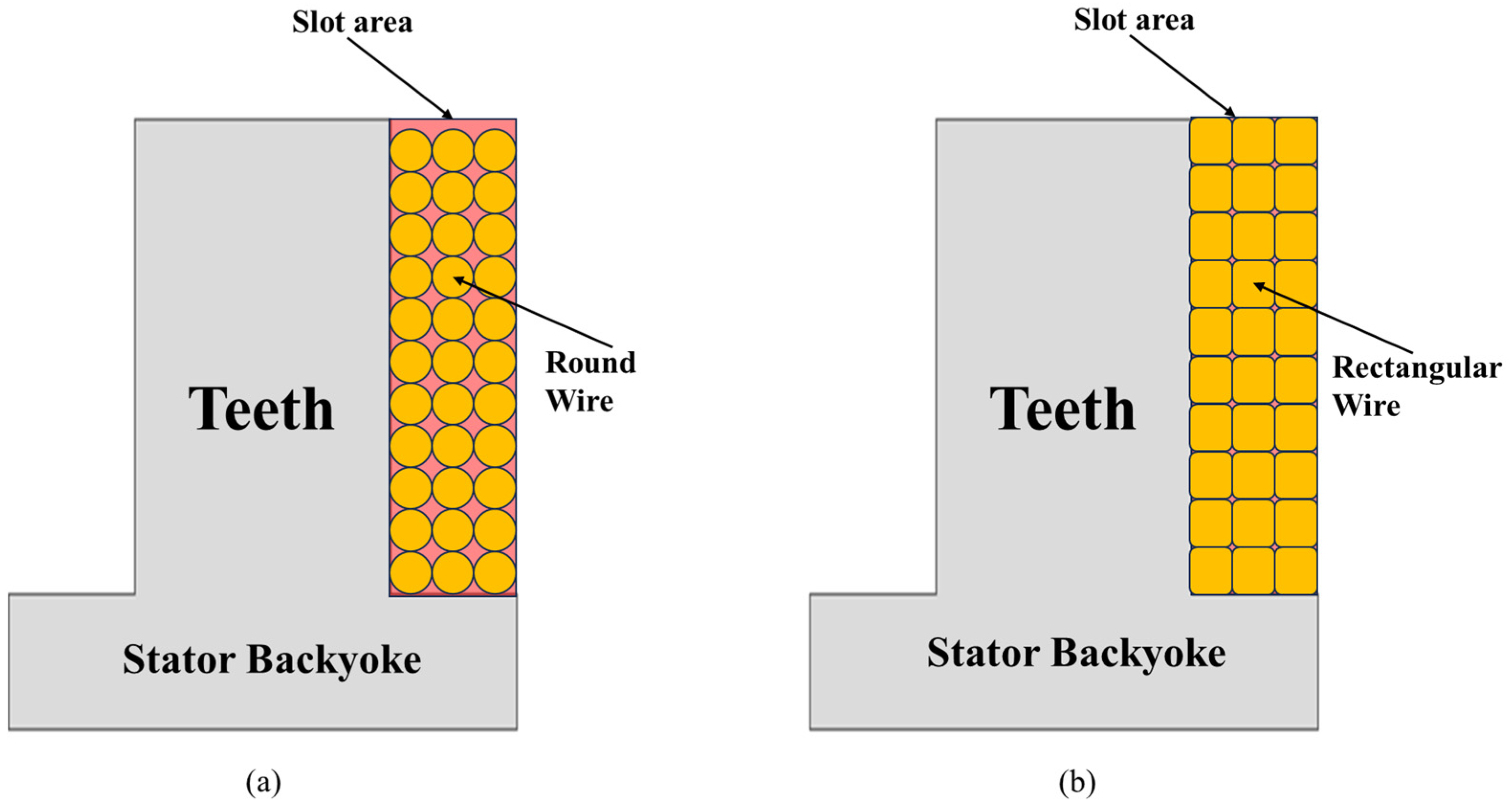

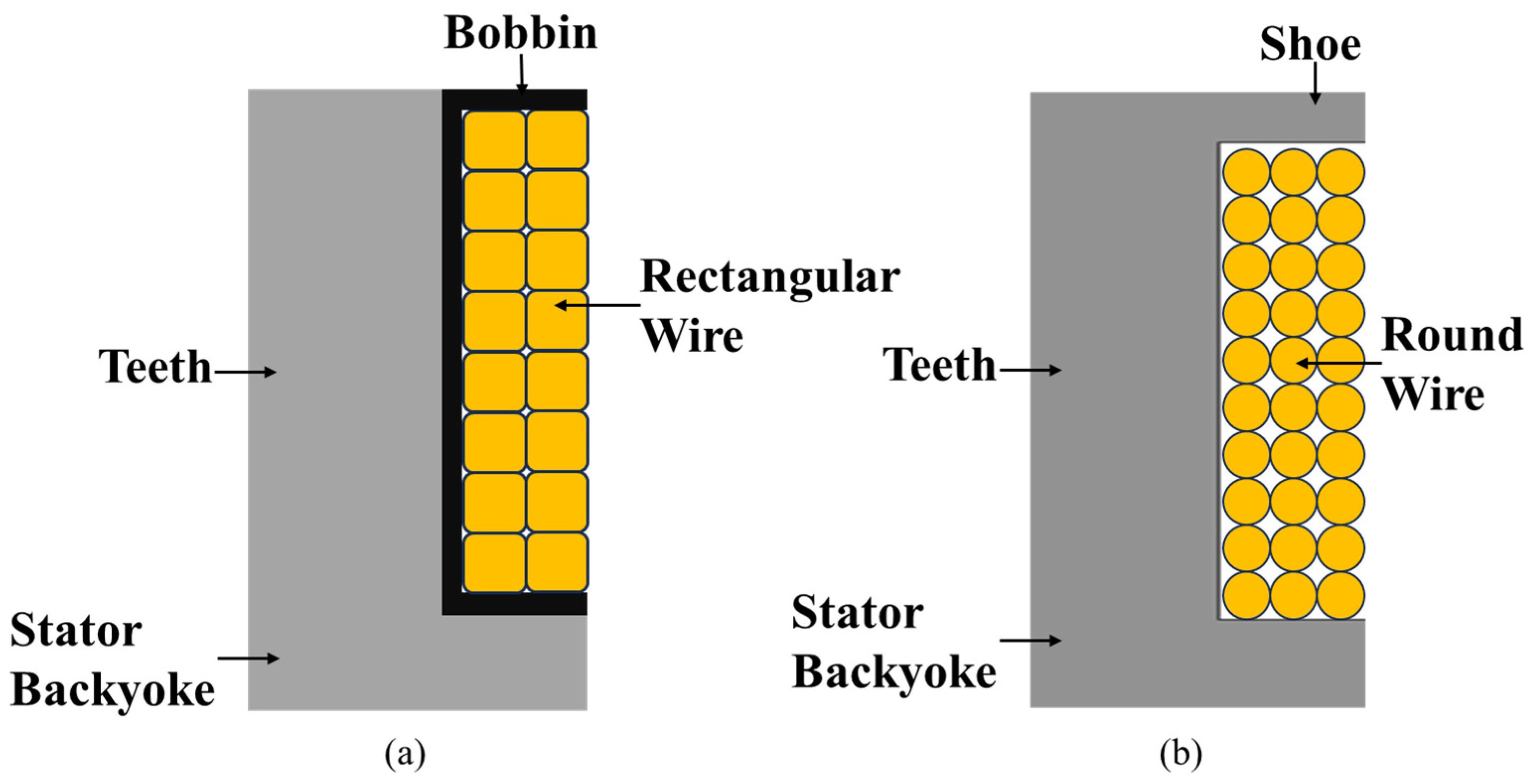

Accordingly, this section establishes a design process applicable to both types of in-wheel AFPMSM (shoe-type round wire winding and bobbin-type rectangular wire winding without shoes). However, for the shoe-type round wire winding, the significant impact of manufacturing constraints such as mold design, insertion process, and size-dependent stiffness makes it difficult to apply the process uniformly. Therefore, the shoe geometry is treated as a consideration dependent on the manufacturing environment, and a method prioritizing the derivation of common variables was adopted. In the subsequent stages, among the multiple design options derived based on the target performance, the model with characteristics most aligned with the requirements was selected as the final design. The overall design procedure was then completed by calculating the number of winding turns while considering voltage limitation conditions. Furthermore, based on the selected base model, complementary designs were performed in parallel to improve manufacturability and pursue additional performance enhancements, thereby finalizing the structure.

Section 3.2 applies the unified design process established in this section to the base model numerically. Through FEM-based analysis, it presents process-specific data along with graphs, clearly defining the selection criteria.

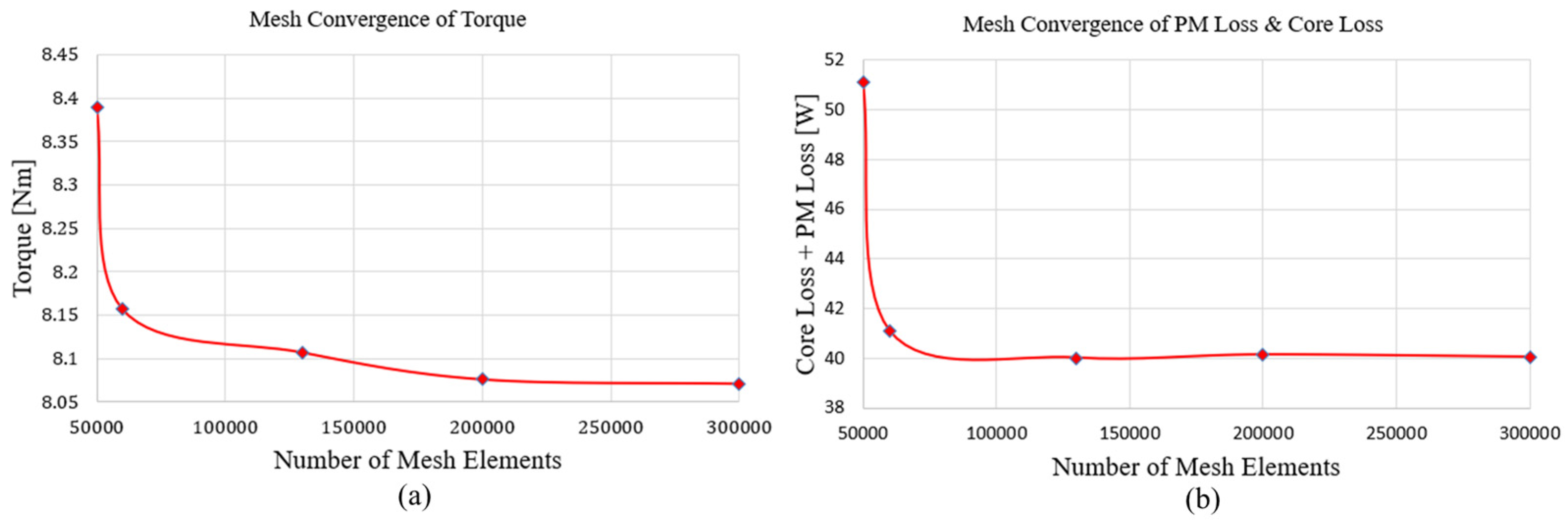

3.2. FEM Verification of the Process

To verify the validity of the proposed process, FEM results obtained by sequentially performing its steps are presented. FEM analysis was performed using ANSYS Maxwell’s 3D model. After allocating the moving band, Transient Magnetic analysis was performed, and the model was reorganized in consideration of symmetry after designing the entire shape. Accordingly, a detailed mesh was given to secure calculation accuracy. Magnetic insulation conditions were applied to the background surrounding the entire motor, and mesh subdivision was performed near the air gap. The current excitation method used a balanced three phase current based on a current source.

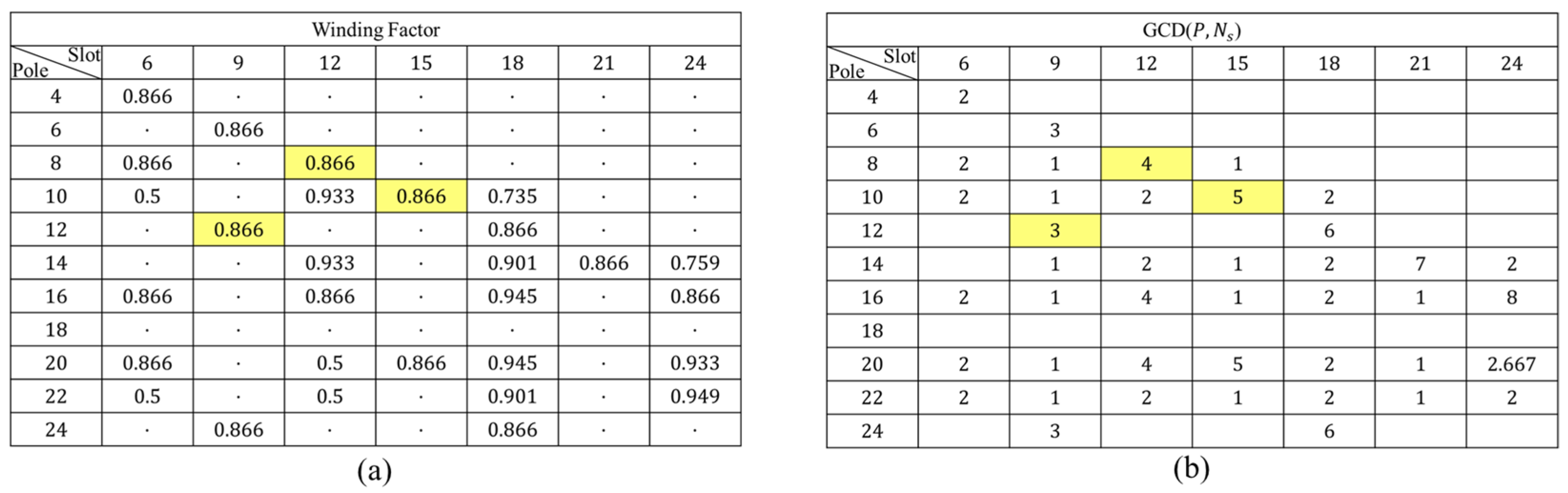

3.2.1. Pole/Slot Combination Selection

As mentioned earlier, the process begins with selecting the pole/slot combination. Since the model is an AMR in-wheel motor, the mechanical robustness of the entire drive system is critical. To achieve this, it was necessary to select a pole/slot combination that reduces excitation force at the motor stage [

14]. Furthermore, as the number of poles increases, the number of teeth must also increase to utilize the pitch factor which complicates stator core manufacturing. Therefore, using

Figure 14, three pole-slot combinations were selected that suppress cogging torque while keeping the pole and slot count as low as possible: 8-pole 12-slot, 10-pole 15-slot, and 12-pole 9-slot. As mentioned in

Section 2, two structures were selected and compared: the shoe-type round wire winding and the bobbin-type rectangular wire winding without shoes.

3.2.2. Initial Modeling

Initial modeling was carried out based on the proposed design procedure, applying the actual constraints. Considering the in-wheel motor application, the outer diameter was set to 180 mm, the inner diameter to 100 mm, and the axial length to 40 mm. This considers the structural characteristics of the AFPMSM: the outer diameter was set larger than the axial length to ensure torque density, while the inner diameter was sufficiently large to accommodate the gearbox and drive system. In addition, the values including the winding end turns were applied to reflect the actual manufacturing geometry. Furthermore, with the axial length constrained, the adjustable axial length variables were limited to tooth length, shoe thickness, rotor back yoke thickness, stator back yoke thickness, and permanent magnet thickness. Among these, tooth length can be derived from the remaining variables within the total axial length constraint, and shoe thickness has low design freedom due to manufacturability issues. Therefore, the ratios of the stator back yoke, permanent magnet, and rotor back yoke were defined as the primary design variables. Accordingly, for the 8-pole 12-slot combination, the ratios of the axial length were set to 2.04:1:2.4; for the 10-pole 15-slot, 1.7:1:2; and for the 12-pole 9-slot, 1.36:1:1.6. These ratios show that as the number of poles increases, the magnetic flux per pole decreases, allowing the rotor back yoke thickness to be reduced. In addition, during the following stages of the process, the outer and inner diameters of the AFPMSM, including the winding end turns, were kept fixed by parameterization, enabling progression through the subsequent procedures.

Figure 15 shows the setting of design variables for fixing the outer and inner diameters, including the end turns.

Table 2 presents the design constraints and target specifications. Since the current density is directly related to the thermal characteristics of the motor, it must be carefully determined. The reference motor used water cooling with a current density of 18 A/mm

2, whereas in this study the same cooling method was adopted but the current density was conservatively limited to 15 A/mm

2 to ensure thermal stability. The reference motor is a mass-produced model with verified performance under the same cooling configuration, and thus, maintaining the same cooling structure while reducing the current density further enhances thermal reliability.

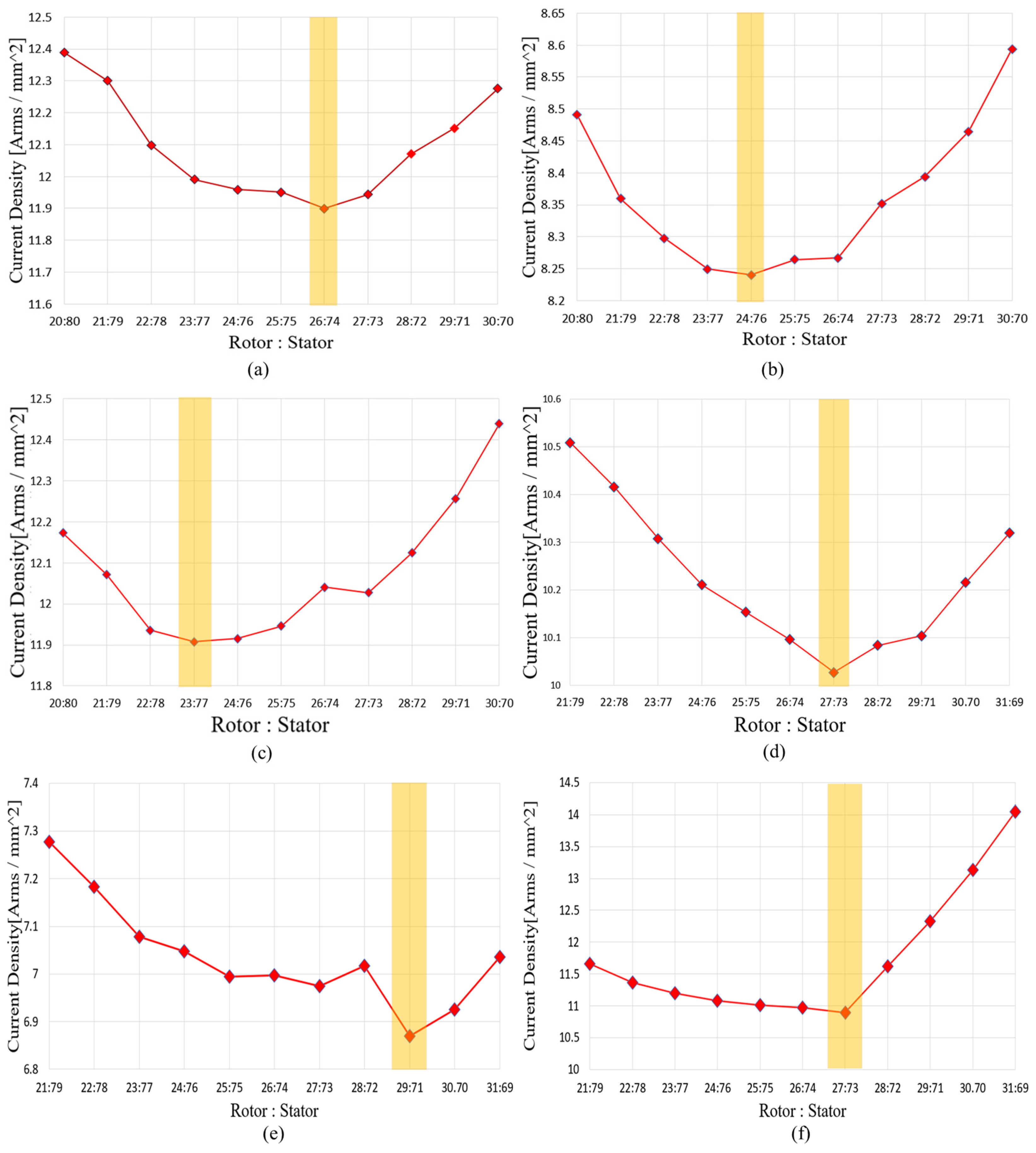

3.2.3. Selection of Loading Ratios

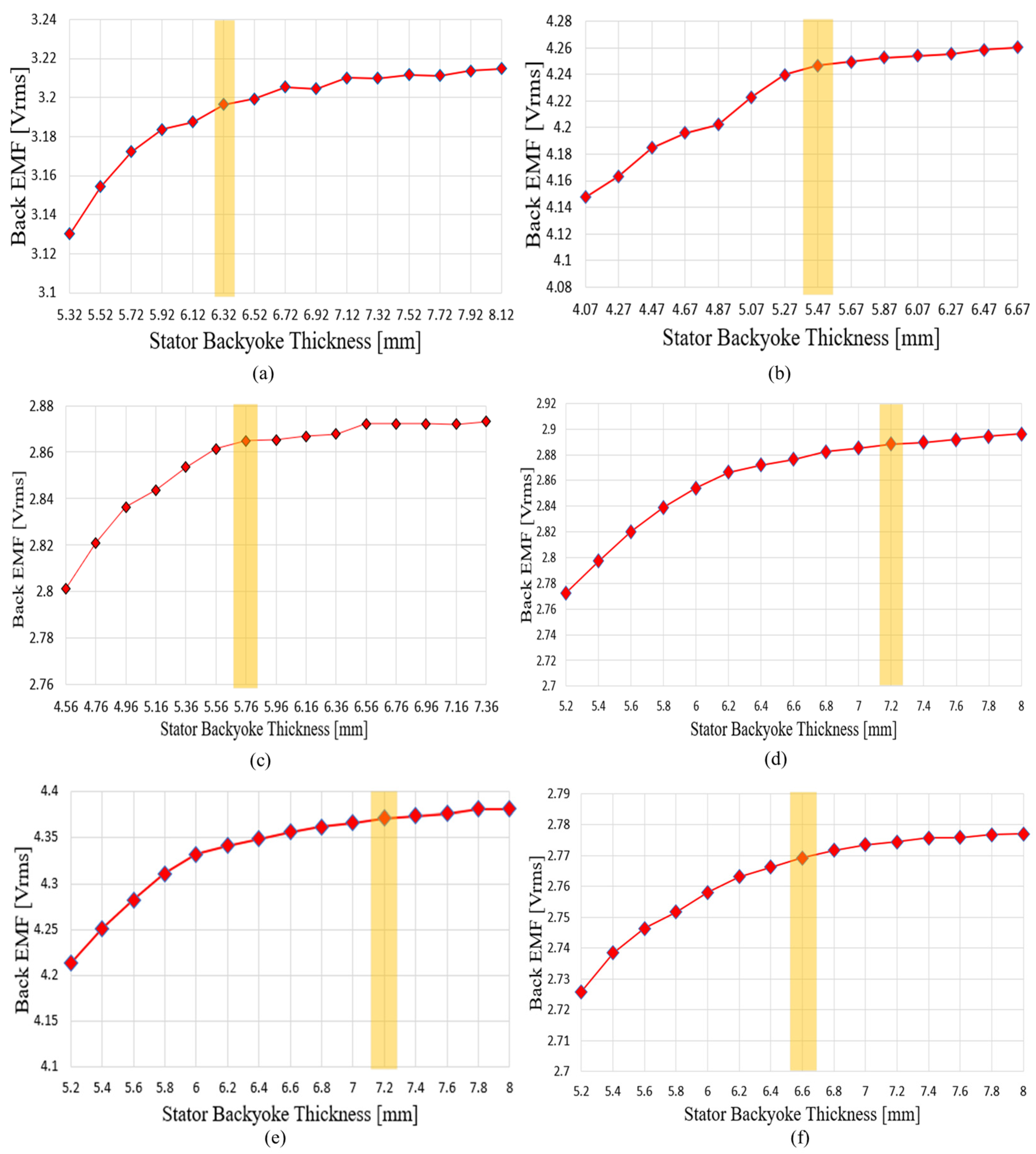

Figure 16 shows the variation in current density and the selected points based on the rotor–stator ratio during the loading ratio process and the x-axis of

Figure 16. represents the ratio of the axial length occupied by the rotor and the stator, with the total active axial length (excluding the air gap) normalized to 100%. The loading ratio selection was performed based on the ratio of the stator back yoke, permanent magnet, and rotor back yoke defined in the initial model. First, the initial model was constructed by applying the ratios defined in

Section 3.2.2. Then, the ratio of the total rotor length to the total stator length was varied by adjusting the permanent magnet thickness. The winding types selected were the shoe-type round wire structure and the shoe-less bobbin-type rectangular wire structure, as described in the previous section. The winding cross-sectional area used in the FEM analysis was defined as follows: For the shoe-type round wire structure, the winding cross-sectional area was calculated as the slot area multiplied by a 40% fill factor. For the shoe-less bobbin-type rectangular wire structure, the winding cross-sectional area was defined as the remaining slot area after subtracting the bobbin’s occupied volume. Based on these defined cross-sectional areas, no-load FEM analysis was performed to obtain the phase BEMF under no-load conditions. Using this result, the current required to achieve the target output was calculated according to Equation (10) (excluding losses):

where

is the no-load phase BEMF and

is the phase current. The calculated current was then divided by the winding cross-sectional area to derive the current density. The point at which the current density was minimized was selected as the design point by adjusting the rotor-to-stator ratio.

All subsequent analyses were based on a single turn per slot. This is because as the number of turns increases, the no-load phase BEMF increases proportionally, and the required current decreases inversely. Consequently, the final current density remains unchanged. Therefore, pre-calculating the number of turns is unnecessary in this stage where the core shape and permanent magnet usage are continuously varied. Calculating the current density using a 1-turn model thus provides consistent results regardless of the final number of turns. This assumption simplifies the analysis while maintaining sufficient validity for the relative comparison of rotor–stator ratios and the derivation of design points.

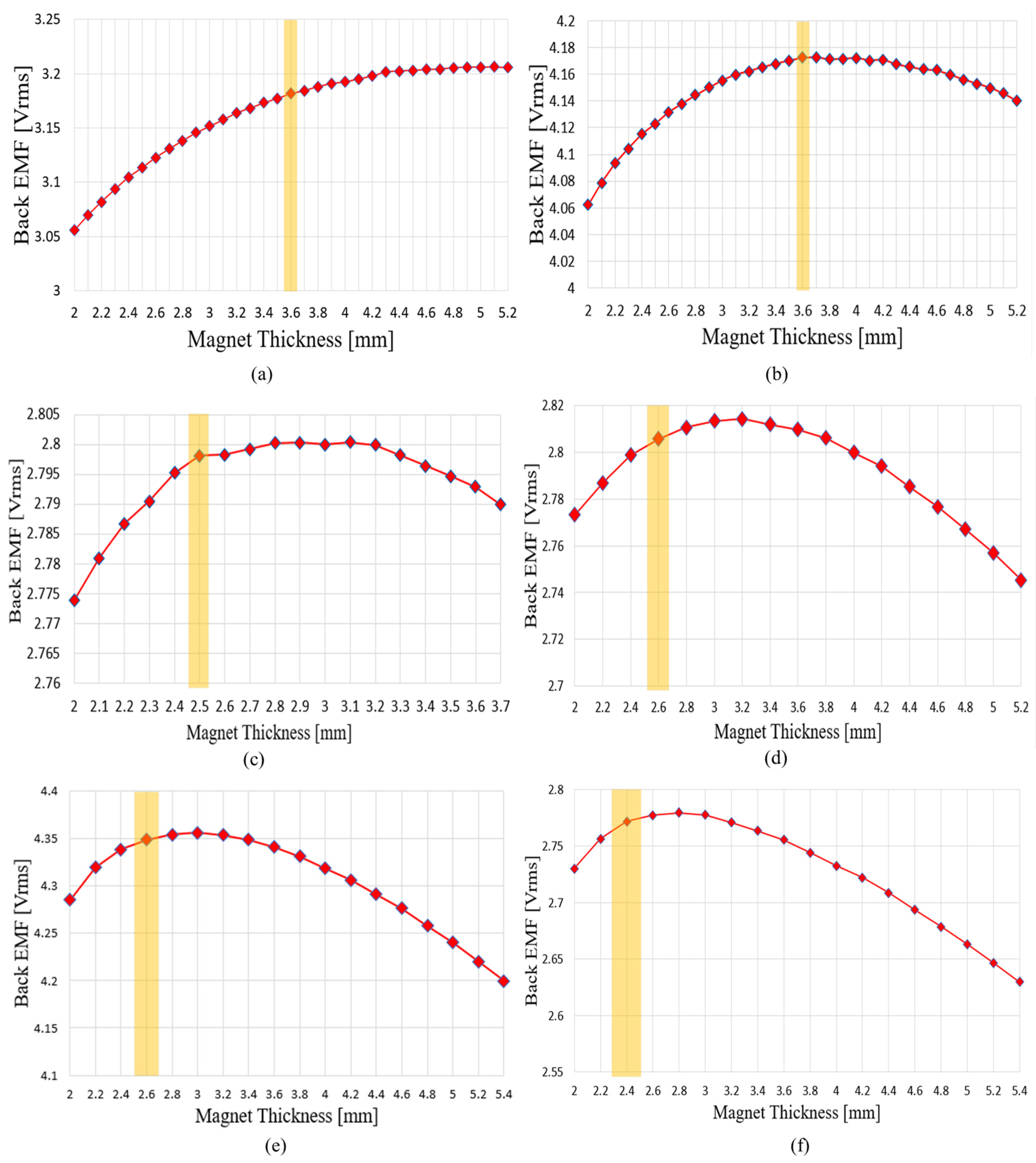

3.2.4. Adjustment of the Ratio of Permanent Magnet Thickness to Rotor Back Yoke Thickness

Figure 17 shows the variation in no-load phase BEMF and the selected points based on adjustments to the permanent magnet thickness and rotor back-yoke thickness. Since the total axial length of the rotor and stator was determined in the previous section, this section adjusted the ratio of the rotor back-yoke thickness to the permanent magnet thickness. FEM analysis performed while stepwise varying the permanent magnet thickness revealed that the no-load phase BEMF initially increased significantly as the magnet thickness increased. However, as the permanent magnet thickened and the rotor back yoke thinned, magnetic saturation occurred, causing the rate of increase to gradually diminish. Therefore, increasing the magnet thickness indefinitely only raises material costs and losses due to magnetic saturation, rather than improving output. Consequently, the permanent magnet thickness was defined as the value at which the rate of increase in no-load phase BEMF first drops below 0.1%. Under this condition, the ratio between the rotor back-yoke thickness and the permanent magnet thickness was determined. This selection method suppresses the risk of magnetic saturation under load while ensuring efficient magnet utilization.

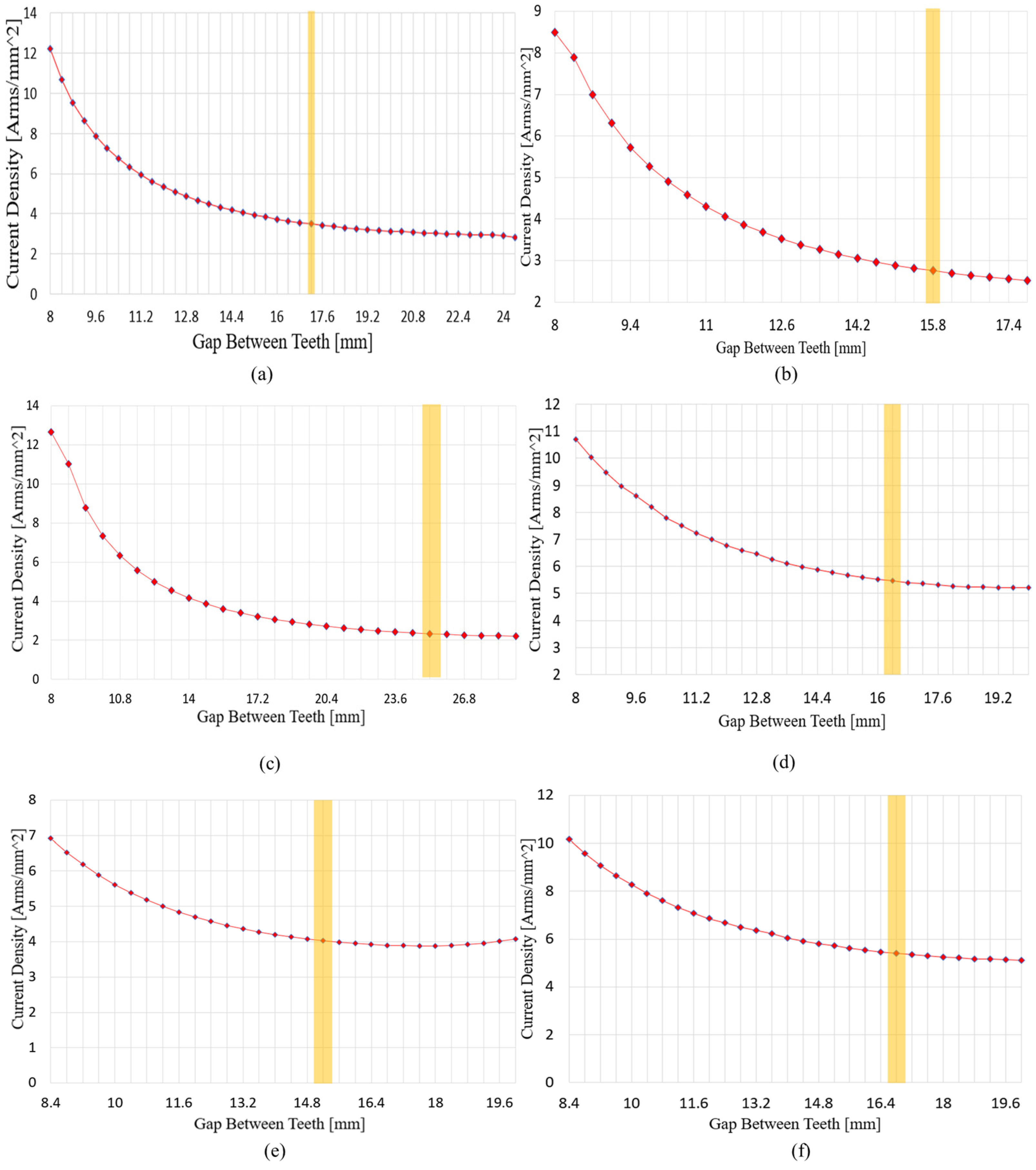

3.2.5. Adjustment of Tooth Length and Stator Back-Yoke Thickness Ratio

Figure 18 shows the variation in no-load phase BEMF and the selected points according to adjustments in stator back-yoke thickness and tooth length. In this section, the ratio between stator tooth length and stator back-yoke thickness was adjusted. As the stator back-yoke thickness increased, the magnetic flux path was secured, resulting in an increase in the no-load phase BEMF obtained from FEM analysis. However, once a certain back-yoke thickness was reached, further increases provided only limited expansion of the flux path, leading to a plateau in the no-load phase BEMF. Increasing the back-yoke thickness beyond this point reduced the slot area, thereby increasing current density for the same output. Therefore, the selection point was defined as the initial point at which the rate of increase in no-load phase BEMF falls below 0.1%. By determining the ratio between tooth length and back-yoke thickness based on this criterion, the design secures the magnetic flux path while suppressing the risk of magnetic saturation.

3.2.6. Tooth Width Adjustment

Figure 19 shows the variation in current density and the selected points according to tooth gap adjustment.

After the axial length–related variables were fixed, motor performance was adjusted by varying the stator tooth width. The tooth width was controlled through changes in the tooth gap and served as a key variable affecting both the slot area and the magnetic flux path. As the tooth width increased, the slot area decreased, limiting winding space and raising current density, while magnetic flux linkage increased, which favored flux path formation. Conversely, as the tooth width decreased, the slot area expanded and current density decreased, but magnetic saturation of the teeth intensified, leading to a plateau in the increase in no-load phase BEMF obtained from FEM analysis. The FEM results indicated that the reduction in current density due to decreasing tooth width was significant initially, but the rate of reduction declined sharply beyond a certain point. Therefore, the first point at which the current density reduction rate dropped below 1% and the no-load phase BEMF ceased to increase meaningfully was selected as the design point. This represents a balance between securing slot area and maintaining flux paths, reflecting a compromise that accounts for both electromagnetic performance and manufacturability.

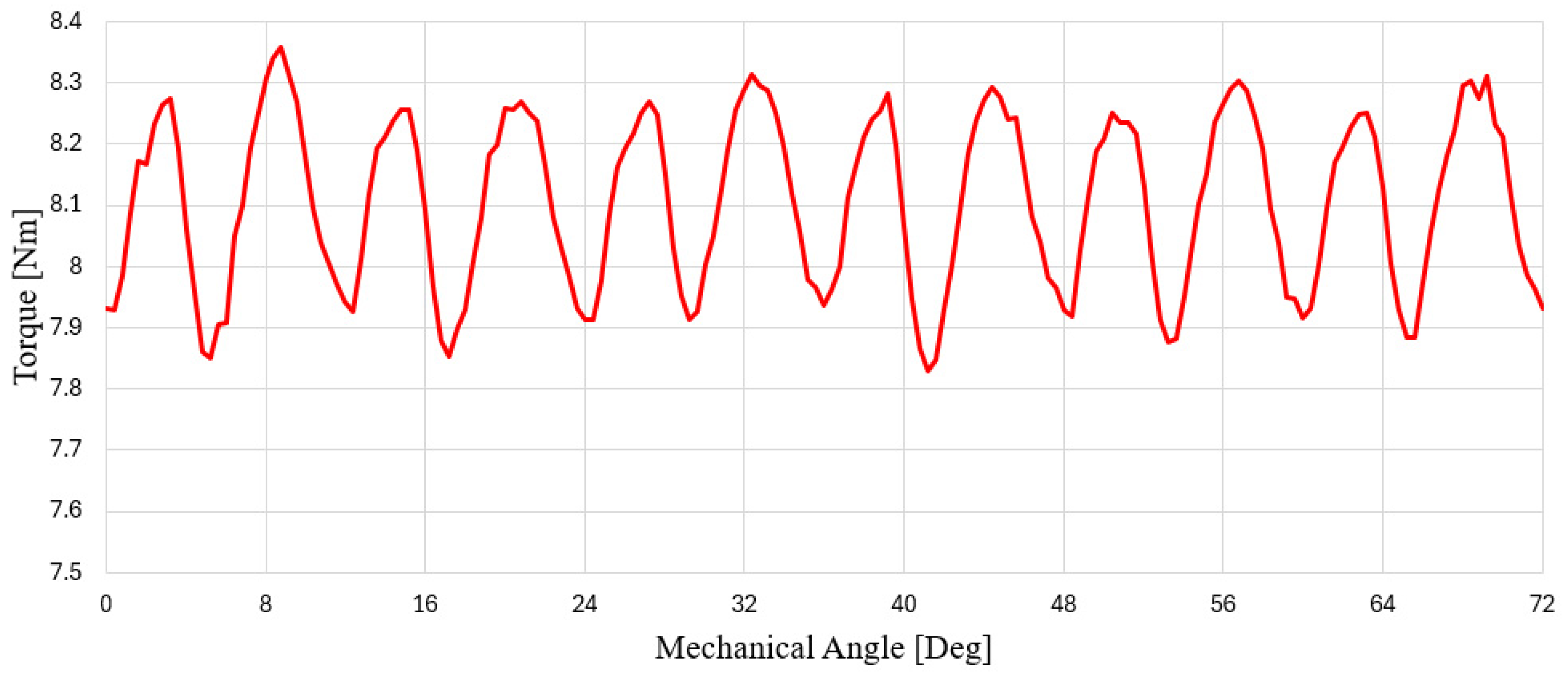

3.2.7. Final Model Selection

In the preceding sections, the ratios of rotor and stator axial lengths and the thicknesses of the permanent magnet and rotor back yoke, as well as the stator tooth length, stator back-yoke thickness, and tooth width, were adjusted to derive the values of each variable. The candidate models obtained through this process all satisfied the external geometric constraints and target output conditions, but differences remained in terms of output and efficiency.

Table 3 presents the performance of the bobbin type after the design process, while

Table 4 presents the performance of the shoe type.

According to the process, the final model should be selected and the number of turns determined by considering the above factors. However, since the drive system employing the in-wheel motor integrates multiple components, additional design steps such as reducing the outer diameter and minimizing torque ripple were carried out to meet the demand for further downsizing. This was possible because the initial design exhibited a higher output than the target value, allowing the outer diameter to be reduced and torque ripple to be minimized without compromising performance. When the outer diameter of the motor is reduced, the amount of magnet material decreases, leading to a reduction in the no-load phase BEMF. Consequently, the number of turns must be redefined with consideration of the voltage limitation. Therefore, after this section, additional designs focusing on outer diameter reduction and torque ripple mitigation were carried out, and the final model was selected based on these results.