Abstract

Industrial process heat typically requires large amounts of fossil fuels. Solar energy, while abundant and free, has low energy density, and so large collector areas are needed to meet thermal needs. Land costs in developed areas are often prohibitively high, making rooftop-based concentrating solar power (CSP) attractive. However, limited rooftop space and the low energy density of solar power are usually insufficient to meet a facility’s demands. Maximizing annual CSP energy generation within a bounded rooftop space is necessary to mitigate fossil fuel consumption. This is a different optimization objective than minimizing the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) in typical open-land, utility-scale heliostat layout optimization. Innovative designs are necessary, such as compact, energy-dense central receiver systems with non-flat heliostat field topographies that use spatially efficient Tilt–Roll heliostats or multi-rooftop and multi-height distributed urban systems. A novel ray-tracing simulation tool was developed to evaluate these unique scenarios. For compact systems, optimized annual energy production occurred with maximum heliostat spatial density, and the best non-flat heliostat field topography found is a shallow section of a parabolic cylinder with an East–West focal axis, yielding a 10% optical energy improvement. Tightly packed Tilt–Roll heliostats showed a double improvement in optical energy at the receiver compared to Azimuth–Elevation heliostats.

1. Introduction

Concentrating solar power (CSP) can be used to generate high-quality process heat and steam for industrial processes such as food production; heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC); combined heat and power (CHP); hospital laundry services; food and biomaterial drying; distillation; dairy production; paper production; cement production; automobile paint curing; waste treatment; and pyrolysis [1,2]. Some estimate that thermal energy for industrial process heat within the range of 50–250 °C accounts for 35% of the world’s fossil fuel usage [3]. Worldwide, it is estimated that 15% of all Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions come from industrial processes, with most occurring due to process heat generation [4], typically directly from burning coal, natural gas, and oil [5] and also indirectly through utility-based electrical generation. In developing countries, forest groves are often completely cut down for firewood, destabilizing slopes, contributing to landslides [6] and other natural disasters, and depleting carbon removal capacity.

Rooftop-based CSP is especially attractive in urban areas and in already built-up areas, for example, at an established, growing hospital with ever-increasing energy usage and costs [7]. In many areas of the world, land costs in built-up areas are prohibitively high for ground-level deployment. Rooftop-based systems are ideal in that regard, as the receiver(s) can be located near to thermal loads. Additionally, although solar energy is a near-infinite resource, the relatively low energy density of sunlight requires a significant spatial area to collect enough energy for industrial thermal processes. Even then, a typical rooftop area is often inadequate for fully powering most industrial thermal applications and completely offsetting the use of non-renewable energy sources. Therefore, such solar thermal systems need to be both compact and energy-dense, optimizing available rooftop space and maximizing solar thermal energy capture. Alternatively, certain types of solar thermal systems permit the distribution of modules across multiple rooftops, such as in urban areas, without excessive thermal piping and consequent losses.

The temperatures needed for industrial processes have a wide range, as seen in Table 1, with most temperature references sourced from [1] unless noted otherwise.

Table 1.

Industrial processes and temperature requirements.

The following solar thermal technologies can provide temperature ranges as specified below in Table 2, with temperatures again referenced from [1] unless noted otherwise.

Table 2.

Solar thermal technologies vs. temperature range.

Common rooftop solar thermal systems, such as non-concentrating flat plate and evacuated-tube collectors, are common in the developing world and are used primarily to heat water for bathing. Compound parabolic collectors (CPCs) are similar to evacuated-tube collectors, additionally employing a small amount of reflective concentration. A series of the evacuated-tube CPC, shown in Figure 1 [16], was used to heat water to 98 °C for use in a solar-powered absorption chilling system [20].

Figure 1.

Rooftop mounted CPC. Photograph by primary author.

Parabolic troughs use a parabolic shape to concentrate sunlight onto a tubular focal receiver and smaller troughs can be used in rooftop systems, as shown in Figure 2 [21].

Figure 2.

Rooftop-scale parabolic trough. Photograph by primary author.

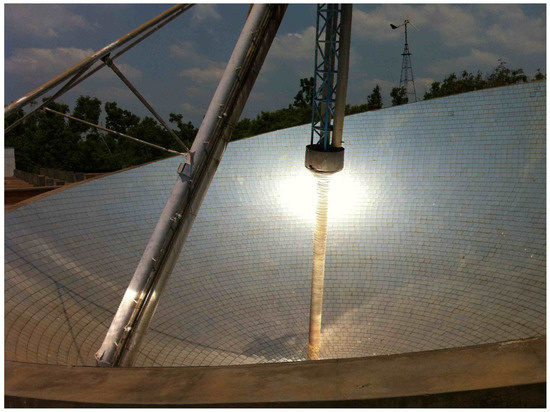

At smaller scales such as rooftops, the research for concentrating solar thermal is sparse, despite the tremendous potential. Multiple rooftop solar thermal cooking systems are used in India [22], predominately employing Scheffler dishes [17], to produce steam to cook rice and other foods on a small industrial scale [23,24,25], as shown in Figure 3. These rooftop systems are simple, low-cost, and reliable, but use available space inefficiently and often require supplemental heat from wood or oil. Remote villagers use a single Scheffler dish for solar-powered distillation to produce saleable lemongrass essential oil [26] to earn a sustainable livelihood.

Figure 3.

A Scheffler dish system at Brahma Kumari Headquarters, Rajastan, India. Dual-sided receivers are under the steam tube. Photograph by the primary author.

One disadvantage of some solar thermal systems such as flat plate, CPC, parabolic trough, and Scheffler dish systems is that the water, steam, or heat transfer fluid must be piped through each module. This can lead to significant additional losses of heat [23], especially if piped over long distances.

Another rooftop system in Auroville, Puducherry, India [18], shown in Figure 4, uses a single large, hemispherical, fixed bowl to reflect sunlight onto a long, tubular receiver mounted onto a heliostat drive to track the sun, generating steam for cooking. The building must be specifically designed for this type of system, however, making it difficult to replicate commercially.

Figure 4.

Auroville Solar Bowl Cooker. Photograph by primary author.

Central receiver, or power tower, systems employ a number of movable mirrors, called heliostats, which track the sun to reflect light onto one or more receivers. Central receivers are a type of 3D concentration that have a “point” as a focus, as opposed to a “linear” focus in 2D concentration systems such as parabolic troughs. Therefore, central receivers typically involve higher concentration ratios and thereby higher temperatures [27], as previously indicated in Table 2. They are thus able to support higher-temperature applications such as cement and glass manufacturing, metal processing, fuel distillation, and materials research, as shown in Table 1. Some claim that in the Indian scenario, representative of developing countries worldwide, central receiver systems have the best financial potential amongst all CSP types [28].

A large portion of these central receiver systems are used for electricity generation, for example, at utility-scale facilities such as PS10 [29], Gemasolar [30], and Ivanpah [31], shown in Figure 5, with thousands of heliostats and multiple, skyscraper-height receivers, often covering hundreds or even thousands of acres of land.

Figure 5.

Ivanpah Utility-Scale Central Receiver Facility. Photograph by primary author.

Very little research has been focused on small, rooftop-scale central receiver systems, although [32] describes a small-scale central receiver system for pressurized water heating for low- to medium-temperature industrial applications, which can be installed locally and disassembled for movement to another location.

Considerable research has focused exclusively on how to design optimized heliostat field layouts for one or more centralized receivers at a utility scale, with a good summary given in [33] and a few notable examples provided in [34,35,36,37]. This research on larger scale systems, however, does not necessarily transfer to smaller, rooftop-scale systems.

Rooftop-scale systems make possible designs impractical in larger systems due to physical constraints and cost. For example, blocking and shading losses can be reduced by implementing non-flat heliostat field topographies, such as increasingly elevating heliostats distanced further away from the receiver, creating an artificial amphitheater or slope-like shape in the heliostat field topography, somewhat similar to Figure 3. At a rooftop scale, the exact topography shape can be intentionally designed and incorporated into the building or an additional structure to maximize annual energy capture. And, as mentioned in the abstract, rooftop-scale systems for process heat need to be maximally energy-dense to offset as large an amount of fossil fuels as possible within a limited space, which is a very different optimization goal than minimizing LCOE in a large, utility-scale system in open desert landscapes. This difference drives innovative and alternative solutions.

Non-flat heliostat topographical layouts have only been lightly explored in the literature and this has exclusively been on large, utility-scale systems focusing on local geography, such as hillsides. The Odielle, France, solar furnace [13] has 63 large heliostats positioned on a south-facing hillside, reflecting light onto a fixed, secondary reflector and then onto a much smaller receiver. The hillside increases the concentration of light by reducing blocking and shading while keeping the system somewhat more compact. Noone et al. [38] and Kiwan [39] present research for optimizing heliostat placement on hillsides for large central receiver systems. Buck et al. [40] describe the design and optimization of a hillside central receiver system in South Africa. Lee and Lee [33] analyze the effect of using hills with large PS10 sized systems. Figure 6 shows a rough concept of a rooftop-scale central receiver system designed to fit on top of four small, adjacent buildings for a solar cooking and material research application, which was the initial impetus for this research.

Figure 6.

Concept drawing of rooftop central receiver system.

While supporting the additional weight of a solar thermal system may require up-front modifications to the building design or structure, as shown in Figure 6, the installation of large solar PV systems and smaller, low-temperature solar thermal systems on existing industrial rooftops is exceedingly common [41], and industrial buildings and rooftops are widespread in nearly every part of the world. A framework, such as that shown in Figure 7, could be employed to support heliostats, but this should be made non-flat with possibly additional room under the taller parts of the structure.

Figure 7.

An example of an additional rooftop structure at the Tirupati temple Scheffler Dish installation for cooking food. Photograph by the primary author.

The thermal aspects of the urban or rooftop solar thermal system will also likely need to be reviewed during the design stage. It is especially important that world-class safety protocols and fail-safe control software design be implemented to ensure the concentrated solar energy is only appropriately focused on designated receivers. Rooftop areas covered with heliostats will see a reduction in temperatures as much of the solar energy is prevented from reaching the roof and is instead reflected away to the receivers. The building areas where the receivers and thermal piping for the working fluid are located will indeed need to be designed to meet the relevant industrial thermal plumbing standards.

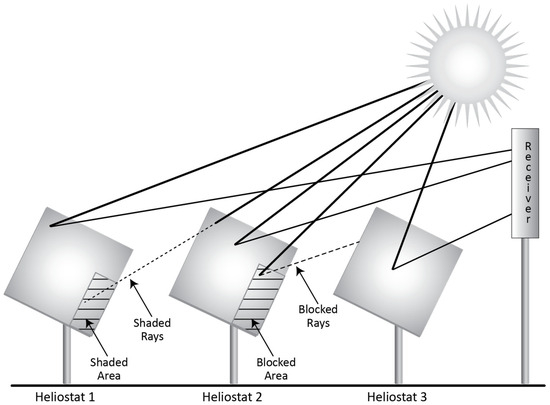

With non-flat heliostat field topographies, there is a strong emphasis on reducing blocking and shading losses. Shading losses occur when one heliostat is shaded by another heliostat, while blocking losses occur when the rays reflected from one heliostat are blocked by another before they can reach the receiver, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Blocking and shading in a solar thermal optical system.

Raising the heliostats up through a non-flat heliostat field topography allows us to reduce or eliminate the blocking and shading losses, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Elevated outer heliostats eliminating blocking and shading.

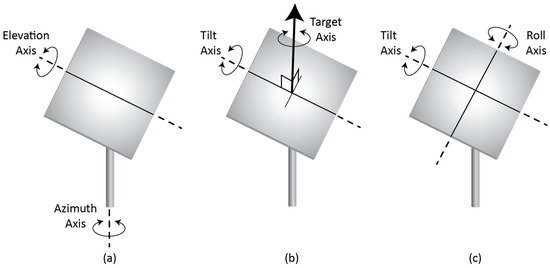

Heliostats for central receiver systems require at least two degrees of freedom of movement to track the daily and seasonal movements of the sun across the sky and reflect direct normal irradiation (DNI) onto a fixed receiver.

Nearly all heliostat field layout research employs Azimuth–Elevation (Az-El) heliostats, which have typically rectangular reflecting surfaces rotating about vertical azimuth and horizontal elevation axes, as per Figure 10a. These require significant areas to swing, leading to comparatively low spatial utilization. This is less problematic in installations where land is low-cost and readily available, and the heliostat field can be made sparser and larger to avoid inter-heliostat blocking and shading effects.

Figure 10.

Types of heliostat: (a) Azimuth–Elevation; (b) Target-Aligned; and (c) Tilt–Roll.

Target-Aligned heliostats [42,43] rotate about a primary axis pointing directly to the receiver and a secondary axis perpendicular to the first and tangential to the reflector, as in Figure 10b, reducing the astigmatism or distortion of the reflected solar image and leading to a reduced receiver size.

The Tilt–Roll heliostat, also known as Tilt–Tip or Pitch–Roll heliostat [44,45,46,47], articulates about a horizontal tilt axis and a second, translated orthogonal roll axis to reflect light onto the target receiver, as shown in Figure 10c. Due to the lack of azimuthal rotation or swing in the horizontal plane, this type of heliostat yields advantages of very dense spatial utilization [48]. While [49,50] describe the general requirements of dense heliostat packing, no studies we found optimizing layouts for Tip–Tilt heliostats. Very thorough arbitrary axis heliostat kinematics were developed in [51]. While these were not used in this work, they would be helpful for working out the kinematics of other alternative heliostat designs.

Larger reflective areas are a predominant trend for heliostat design. These reduce the number of individual heliostat installation occurrences and maximize the value of expensive azimuthal and elevation drives, which results in a lower LCOE [52,53], similar to the trends seen in wind turbines [54,55]. Notable exceptions [56] use mass-produced, existing, off-the-shelf components to create small heliostats, minimizing wind load and structural costs.

In this work, rooftop-scale central receiver systems using non-flat heliostat field topographies, such as shallow parabolic curves in the North–South and/or East–West directions, and small, densely packed Tilt–Roll heliostats are systematically studied to determine the best methods for minimizing blocking and shading losses and maximizing annual energy at the receiver(s). A novel and custom simulation tool was required, developed, and validated to facilitate this research.

2. Materials and Methods

The main focuses of this research were analyzing the impact of various (1) non-flat heliostat field topographies on efficiency and annualized energy collected and (2) quantities, sizes, and spacing arrangements of densely packed Tilt–Roll heliostats. We also aimed to (3) develop a tool to facilitate this analysis.

At the start of this work, the authors were unable to find flexible, low-cost, easily available software tools to precisely simulate tightly packed Tilt–Roll heliostats with non-flat topographies. Therefore, a novel, custom Monte Carlo ray-tracing tool was developed using MATLAB R2023b [57] and Zemax OpticStudio Premium (2023) [58]. OpticStudio has powerful, industry-validated ray-tracing capabilities, and while not focused on solar applications, the native 3D graphics greatly aid development and visualization of both traditional and novel optical systems. MATLAB is well suited for supervisory control of OpticStudio’s inbuilt API (application programming interface).

Monte Carlo ray tracing generates very large numbers of randomly generated, directed light rays and calculates their paths through the optical system using predictable physics interactions such as reflection and absorption. It precisely captures the shading, cosine, blocking, and other effects in a CSP system, albeit with a longer computation time compared to analytical, formula-based simulation methods. An excellent review of the various solar thermal simulation tools available and their capabilities is given in [59].

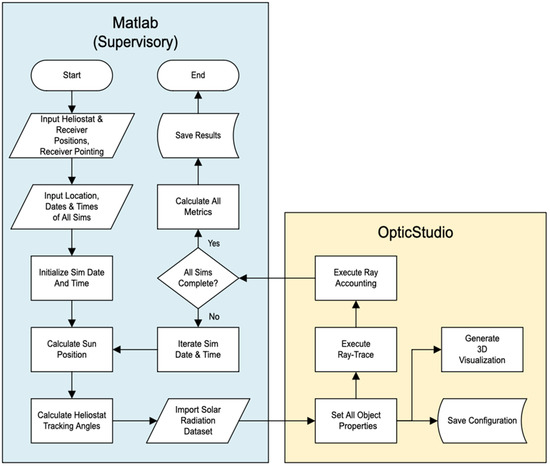

The custom tool software flow is described below and in Figure 11:

Figure 11.

Developed simulation tool flowchart.

- MATLAB receives the input of the simulation’s global location, date, time, and heliostat and receiver locations, calculates the sun’s position to high precision with the NREL’s SPA (National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Solar Position Algorithm) [60], and determines the heliostats’ time-based tracking angles and inverse kinematics as developed by the primary author in [46], importing the Himawari solar radiation dataset [61].

- The sun’s position and power and the heliostat and receiver positions and tracking angles are passed to OpticStudio’s ray-tracing engine. OpticStudio’s 3D visualization tools are used to verify the heliostat field’s tracking and topography.

- OpticStudio executes the ray trace, counts the rays interacting with the same optical objects in the same order (ray accounting), and then passes the data back to MATLAB.

- Annualized results are created by repeating steps 1–3 for each sunlit hour of the day, for 21 March, 21 June, 21 September, and 21 December, similar to [62]. Testing shows that in these rooftop system scenarios, increasing the simulation interval from every month to every three months reduces simulation time by 2/3rds with a minor 1.3% increase in net efficiency and total energy (see Appendix A, Rows 1 and 2), while still producing usable annual results. This is expected as the simulation outputs vary in a smooth and continuous manner as the sun’s position moves throughout the day and year. The months above capture the bounding points of the insolation and simulation space: the maximum insolation of the summer solstice, the minimum insolation of the winter solstice, and the equal day and night lengths of the equinoxes. Since this work is comparing heliostat layouts, increasing the simulation interval does not appreciably affect final results.

- MATLAB post-processes the simulation year’s data, first totaling the hourly flux for the various ray paths to determine instantaneous/hourly efficiencies, as per [62,63]. These hourly results are aggregated into daily results using a minor variation of the methods in [38]. The daily results are then annualized to yearly results. Individual and collective heliostat metrics are calculated (such as shading, cosine, blocking, optical intercept, and total optical efficiencies) on an hourly, daily/monthly, and annualized basis.

Several assumptions and simplifications were made which did not appreciably alter the results since the analysis was comparative amongst similar systems:

- Sun shape: This is a pillbox shape with an angular extent of 0.25 degrees (4.3633 milliradians). A pillbox shape is a common sun shape that is simpler to model in the OpticStudio software, which is not intrinsically designed for solar applications. The angular extant value used is approximately 1% less than the typical value of 4.65 milliradians [63].

- Heliostat articulation: It is first rotated about one axis (aligned with the North–South or East–West axis) and then about the translated, orthogonal axis. Pivot joints to surface offsets are set to 1 mm, while real world systems would be slightly larger and potentially at both the 1st and 2nd joints below the reflector surface on the center pedestal, shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Tilt–Roll heliostat prototype built earlier for inverse kinematics validation [46].

Figure 12. Tilt–Roll heliostat prototype built earlier for inverse kinematics validation [46]. - Heliostat range of motion: Full necessary range of motion allowed, not constrained by any type of physical actuator or drive geometry limitations, as per Figure 12.

- Heliostat-aiming algorithm: Pointed to the center of the closest receiver for simplification, although it is understood that in practical applications aiming techniques can be employed to prevent hot-spots on the receiver.

- Canting: No heliostat canting or focusing of the reflective surface of the heliostat, implying that the heliostat’s optical image on the receiver has not undergone any concentration. Canting or focusing can be employed later to increase concentration ratios and output temperatures.

- Heliostat packing: Arranged in a simple rectangular grid layout when viewed from above, as in Figure 13. This type of layout packs well with Tilt–Roll heliostats, although other layouts are possible.

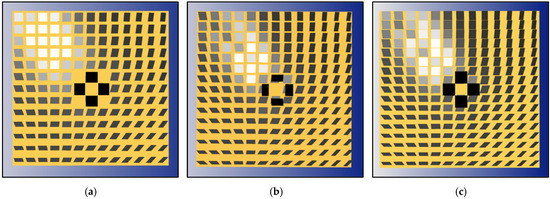

Figure 13. Base, flat, Tilt–Roll heliostat field layouts: (a) 160, (b) 194, (c) 220-Max. Heliostats were shown post-simulation and the heliostats were oriented to reflect the sun’s rays onto the receivers.

Figure 13. Base, flat, Tilt–Roll heliostat field layouts: (a) 160, (b) 194, (c) 220-Max. Heliostats were shown post-simulation and the heliostats were oriented to reflect the sun’s rays onto the receivers. - Receiver aiming: The receiver for a group of heliostats is pointed to the heliostat closest to the geometric center or arithmetic mean of the position of those heliostats. In an ideal world, the receiver normal would be pointed directly towards each heliostat. As this is not possible for the standard flat receivers simulated here, they are instead pointed to the geometric center of the group of heliostats they are closest to.

- The various losses in a CSP system are described below and they are as per those of [62,63].

- Cloudiness: this is due to clouds preventing the sun’s direct rays from hitting the heliostats.

- Shading: this is the result of one heliostat preventing the sun’s direct rays from hitting the reflective surface of another heliostat, as per Figure 8.

- Cosine: this is the reduction in a heliostat’s reflected area as viewed from the sun and is equal to the cosine of the angle of incidence, which is the angle between the heliostat’s normal and the ray from the sun to the center of the heliostat, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Cosine loss/efficiency due to angle of incidence.

Figure 14. Cosine loss/efficiency due to angle of incidence. - Reflectivity: due to imperfect heliostat surface reflector optics (surface flatness/specularity) and dust soiling, this often includes an availability term for reliability and maintenance.

- Blocking: this describes rays that are reflected from a heliostat and then hit the backside of another heliostat instead of the receiver target, again as per Figure 8.

- Atmospheric attenuation: This occurs due to the natural absorption and scattering of the sun’s rays as they strike gas molecules in the atmosphere between the heliostat and receiver. Due to the small physical dimensions of the optical systems studied here, the atmospheric losses in these rooftop systems were calculated to be less than 0.0018% using the methods in [64], and were therefore not included.

- Spillage: this is unblocked radiation that is reflected from the heliostats but misses the intended receiver aperture.

- Absorption/receiver: This relates to energy striking the receiver that is not absorbed by the heat collection media. This thermal aspect is not included in this study, which is focused on the optical properties of the system.

- Minor optical error sources, such as the heliostat pedestal installation accuracy (clocking, height, verticality/plumbness), and other similar error sources, such as those given in [65,66], are not addressed in this work.

To test the impact of heliostat density within a 26 m × 26 m bounded, rooftop-scale area and the consequent blocking and shading efficiencies, a number of base Tilt–Roll heliostat field layouts were created using simple, grid-based, rectangular tiling, as shown in Figure 13.

- 160: 13 × 13 matrix of 1.5 m × 1.5 m Tilt–Roll heliostats.

- 194: 13 × 15 matrix of 1.5 m × 1.5 m Tilt–Roll heliostats.

- 220: 13 × 17 matrix of 1.5 m × 1.5 m Tilt–Roll heliostats, with the heliostat size along one axis maximized to the largest possible degree without interference during articulation in that direction; this is the largest number of this size heliostat that will fit within the bounded area.

- 220-Max: the same 13 × 17 matrix with the dimensions of the second axis of the heliostat also maximized, to 1.5 m × 1.625 m, which is to the largest possible degree without interference between adjacent heliostats during articulation movement about both axes.

Figure 13 also shows that each of these base scenarios had the following parameters: (1) four, 2.0 m × 2.0 m, central tower mounted receivers; (2) central heliostats removed for the tower; and a (3) 30 mm minimum gap between heliostats under all circumstances. The assumptions and simplifications previously described for the validation were again applied here, since they are common to the various field topographies and layouts and do not appreciably affect comparative results.

We created a large quantity and variety of layouts where heliostat heights increased the further they were from the center of the field along the North–South and/or East–West axes. Parabolic shapes were introduced to the flat heliostat field topography as the height of the heliostats increased according to the familiar quadratic equation, y = a × x2 + b, with b = 0, and they were permutated by varying the constant a in increments of 0.005, which was empirically determined to provide sufficient simulation resolution and granularity when using units of meters, without being overly burdensome. This is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Height vs. distance from center for varying constant “a”.

This work aims to maximize the annual optical power at the receiver for a constrained, fixed rooftop area. When reviewing the data from the many simulation runs (see Appendix A for abbreviated efficiency and performance data for each of the approximately 180 simulation runs), it became clear that the most relevant metrics for evaluating different heliostat field topographies with the same number and size of heliostats were the shading, cosine, and blocking efficiencies and their cumulative multiples. This gave us the formula for SCB Efficiency:

SCB Efficiency = Shading Efficiency × Cosine Efficiency × Blocking Efficiency.

This eliminates the effects of other fundamentally less relevant system optical properties, such as receiver size, shape, heliostat canting and focusing, and others, and also eliminates other losses in all simulation scenarios. These would often need to be individually modified to give equal optical intercept efficiencies for each simulation, but would require greatly increased and unnecessary complexity to do so. The SCB Efficiency is an indicator of how much energy hitting the heliostats could potentially reach the receiver, permitting a fair, apples-to-apples efficiency comparison of similar heliostat field layout topographies.

Calculations to determine blocking and shading are typically computationally intensive [37]. Numerous works [67,68,69] discuss methods to simplify the blocking and shading calculations, while others [70] use this information to design more efficient systems without blocking losses. This work implemented a novel method of separately calculating blocking and shading which will be published separately.

Another key metric used is the Effective SCB Area, permitting the comparison of the combined impact of SCB Efficiency with differing quantities and sizes of heliostats, and this is a measure of how much solar energy incident on an area could reach the receiver:

Effective SCB Area = SCB Efficiency × Number of Heliostats × Area per Heliostat.

The Effective SCB Area is related to the Total Heliostat Aperture Area used in [71], which includes cosine efficiency, but also includes the impact of shading and blocking efficiencies. The Effective SCB Area thus gives a solid indicator of a particular heliostat field’s optical energy capture potential. Note that the Effective SCB Area also equals the optical power at the receiver, in kW, assuming 1000 W/m2 insolation, 100% heliostat reflectivity, and 100% optical intercept efficiency.

Heliostat Density is defined below:

Heliostat Density = (Number of Heliostats × Area per Heliostat)/(Total Heliostat Field Bounded Area).

Finally, Solar Utilization also provides an indication of how effectively the total solar power falling on a bounded area is utilized in terms of kWh/m2/year:

Solar Utilization = (Total Annual Energy at the Receiver)/(Total Heliostat Field Bounded Area).

This metric allows for comparisons of layouts covering different rooftop areas.

3. Results

3.1. Developed Tool Validation

Due to the large capital and time costs of implementing physical CSP systems, new solar thermal simulation tools are typically benchmarked to existing tools which have already been validated with physical systems. For example, the NREL’s SolTrace ray-tracing tool was successfully validated with their physical High Flux Solar Furnace in Golden, Colorado [72] and is frequently used as the benchmark for many other tools due to its maturity and accuracy [34,73,74,75].

SolarPILOT (Solar Power Tower Integrated Layout and Optimization Tool) 1.6.0 (beta) [71] is a modern build of the NREL’s lineage of analytical software which optionally uses the SolTrace ray-tracing engine. The NREL’s well-used SAM (System Advisory Model) tool [76,77] activates SolarPILOT for CSP analysis. Testing by the primary author revealed that, on smaller systems with high degrees of blocking and shading, SolarPILOT’s ray-tracing method was significantly more accurate than their analytical method. Therefore, the custom-developed MATLAB/OpticStudio tool was benchmarked against SolarPILOT when running the SolTrace ray-tracing engine.

While SolarPILOT’s dynamic grouping feature greatly increases processing speed at the cost of slightly reduced accuracy and works well for utility scale systems, noticeable errors are introduced for smaller, rooftop-scale systems. A beta version of SolarPILOT which included the option to disable dynamic heliostat grouping was graciously provided by Bill Hamilton at the NREL, allowing for effective, apples-to-apples validation.

SolarPILOT can currently utilize only Azimuth–Elevation heliostats and not alternatives like Tilt–Roll, while the developed tool can work with both types. A simplified, triangular-shaped flat field of 48 Azimuth–Elevation heliostats with one receiver, illustrated in Figure 16—approximating one quadrant of the larger 26 m × 26 m Tilt–Roll rooftop system featured later in this work—was used for benchmarking. All parameters were set identically, such as heliostat and receiver locations, sizes and reflectivity, availability, and absorption efficiencies.

Figure 16.

Validation system layout (flat, 48 Az-El heliostats, 1 receiver): (Left)—Zemax/Optic Studio (pre-simulation); (Right)—SolarPILOT (post-simulation, with coloring for heliostat net efficiency).

We then ran a full year of simulations for the same scenario using both the SolarPILOT and MATLAB/OpticStudio tools, with simulations ran for each sunlit hour of the four cardinal days of the year, 21 March, 21 June, 21 September, and 21 December. Averaging the hours of each day, and then averaging the four simulation days, provided the following yearly results shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Simulation tool results comparison—annualized, yearly results.

The largest individual differences were seen on the solstice days, when the elevation angle was very low, in the mornings and evenings. This was believed to be due to the custom MATLAB/OpticStudio tool being set up to count rays which fall directly onto the receivers from the sun vs. the SolarPILOT tool which uses the simplification of allowing these rays to pass to the heliostats and then be reflected to the receiver(s). The custom tool was set up in this manner as with smaller, rooftop-scale heliostat fields, a receiver that was slightly larger than the heliostats would capture a measurable, although still low, set of rays coming directly from the sun. The net effect is that the further the sun was from being directly overhead, the greater this difference became. However, these individual differences represented at most only small single-digit percents.

3.2. Simulation Results

Approximately 180 yearly simulations, each with single-parameter, small-step changes, were performed to understand the impact on efficiency of (1) various quantities and sizes of Tilt–Roll heliostats and (2) non-flat heliostat field topographies, and to optimize the annualized energy from the bounded rooftop area. The following key observations for these spatially compact rooftop systems were derived from the simulations:

- Non-flat heliostat field shape: SCB Efficiencies for the non-flat, linear scenarios were significantly lower than for both the flat and non-flat parabolic scenarios and were characterized by lower cosine and blocking efficiencies.

- Parabolic heliostat field shape: Parabolic layouts had decreased cosine efficiencies which were countered by significantly increased blocking efficiencies, leading to a strong net efficiency gain over the flat and non-flat linear scenarios.

- Parabolic heliostat field shape direction: A parabolic heliostat field shape with a its curve along the North–South direction (focal line in the East–West direction) always performed better than when the parabolic curve lay along the East–West direction (focal line in the North–South direction).

- Separate North–South parabolic heliostat field shape: The SCB Efficiency could be very slightly further optimized by using separate parabolic constants for the Northern and Southern halves of the heliostat field, raising Northern-half heliostat heights and lowering Southern-half heliostat heights.

- “Bowl” heliostat field shape: Additional minor improvements could be made by combining parabolic curves in both the North–South and East–West directions to create a “bowl” shape, yielding another very minor improvement in SCB Efficiency. The shading efficiency of the bowl shape was better than that with only the North–South or East–West parabolas alone, although the blocking efficiencies were worse by a similar amount, effectively negating any gains.

A more detailed discussion of these results follows. Due to the numerous parameters that could be varied for optimization, it was not possible to run a matrix of all permutations. Therefore, a manual optimization approach was employed, where one parameter was modified and understood, and then that optimized result was used as a starting point for understanding the next parameter varied. This flow generally consisted of (1) understanding the impact of heliostat density, (2) understanding the shape of the non-flat topography (e.g., flat, linear, parabolic), and (3) understanding what led to optimization of that particular, non-flat shape. Additional simulations were run to verify and cross-check results, ensuring that the conclusions drawn were applicable to other scenarios. Table 4 provides an overview of the investigative methodology, simulations performed, and key learnings. Detailed performance and efficiency data for all simulations are given in Appendix A.

Table 4.

Description of manual optimization process and simulation rows listed in Appendix A.

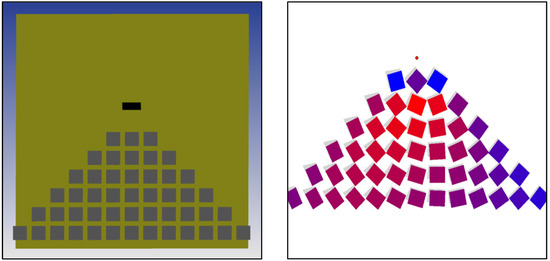

Through 11 key simulations of the 179 which represent various levels of optimization, Figure 17 summarizes the simulations detailed in Table 4 and Appendix A. Columns 1–6 are for the flat base layouts, with the only changes being to the number and size of the Tilt–Roll heliostats and their initial rotation. Columns 7–11 then show sequential changes, starting from the best-case 220-Max scenario (Column 6), which further modify and optimize the non-flat heliostat field topography.

Figure 17.

Efficiency and area utilization metrics throughout the optimization process. Column legend: number of heliostats (size), initial heliostat articulation axis, topography shape, receiver height (m). (Appendix A, Row Number).

As mentioned previously, the Effective SCB Area is a metric for the amount of solar energy which could potentially reach the receiver amongst layouts with differing numbers of heliostats. Running and annualizing the simulations for a full year’s results gives the receiver energy in MWh/year, relating the improvements in the Effective SCB Area to real-world optical power output at the receiver.

Cosine and blocking efficiencies and total power output are increased by raising the receiver’s height, a well-known effect in central receiver systems [27,32]. The receiver height was simulated between approximately 4 m and 10 m, keeping with the small heliostat field size of 26 m × 26 m, with diminishing returns seen as the receiver height approached 10 m. The 7.38 m receiver height was used for most optimized scenarios as it captures most of the gains and is still easily feasible on rooftops.

The Effective SCB Area, an indicator of how much solar energy falling on the bounded rooftop area can potentially reach the receivers under ideal circumstances, increases continuously through all simulations in Figure 17, from left to right, as the number of heliostats, density, and size increases, coinciding with topography changes.

3.2.1. Quantity and Size of Tilt–Roll Heliostats

Columns 1–6 of Figure 17 show that the highest efficiencies and annual energy capture occur when the heliostat density is highest. The SCB Efficiency of the heliostat field was always highest when the initial rotation of this Tilt–Roll heliostat design [46] was in the East–West direction, leading to denser packing in the North–South direction. This effect is seen in parabolic trough systems which have their axis of rotation along the North–South direction, tracking the sun from East to West, where the “dense” (continuous) packing is along the North–South axis and the movement space is along the East–West axis [78]. Therefore, all further analysis in Columns 7–11 start with the 220-Max heliostat scenario in Column 6.

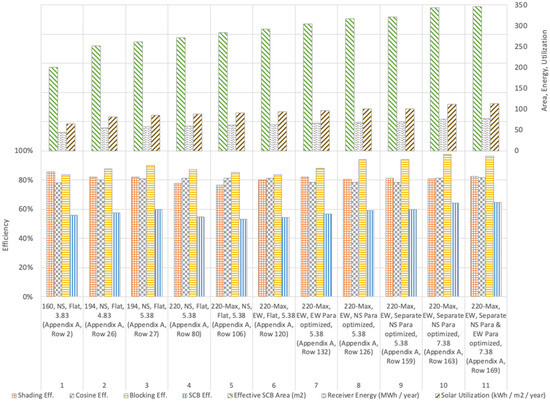

Figure 18 is provided to show an example of the impact of changes to the parabolic constant, as per Figure 15, for the scenario of 220-Max heliostats, North–South parabola, and East–West initial heliostat articulation. The first column is for the flat scenario, a = 0, also shown in Figure 17, Column 6 and Appendix A, Row 120. It can be seen that the SCB Efficiency is highest for a = 0.030, which is shown in Figure 17, Column 8, and Appendix A, Row 126, and this is 4.7% higher than the value seen in the flat scenario.

Figure 18.

Efficiencies vs. North–South parabolic constant “a”.

3.2.2. Non-Flat Heliostat Topographies

Proceeding through Columns 6–11 of Figure 17, we see a scenario with (1) increased blocking efficiency (reduced blocking losses), that (2) shading and cosine efficiency/losses remain roughly the same, and a scenario with (3) increasing SCB Efficiency and receiver energy with reduced overall losses.

Figure 19 helps to understand these insights by comparing the flat (Figure 17, Column 6) and optimized North–South parabolic (Figure 17, Column 8) topographies. Figure 19a shows hourly changes in the shading, cosine, blocking, and SCB Efficiencies (averages of the monthly results). The optimized North–South parabolic topography (Figure 17, Column 8) has significantly increased mid-day SCB Efficiency over the flat scenario (Figure 17, Column 6), where improved blocking efficiency outweighs reduced cosine efficiency, with shading efficiency remaining constant. Figure 19b shows the monthly changes (averaged over the daily sunlit hours) for the same scenarios. The blocking efficiency for the optimized North–South parabolic topography is dramatically higher and flatter, especially during the year’s summer half with higher insolation. This improvement outweighs the mildly reduced cosine efficiency, while the shading efficiency is again largely unchanged.

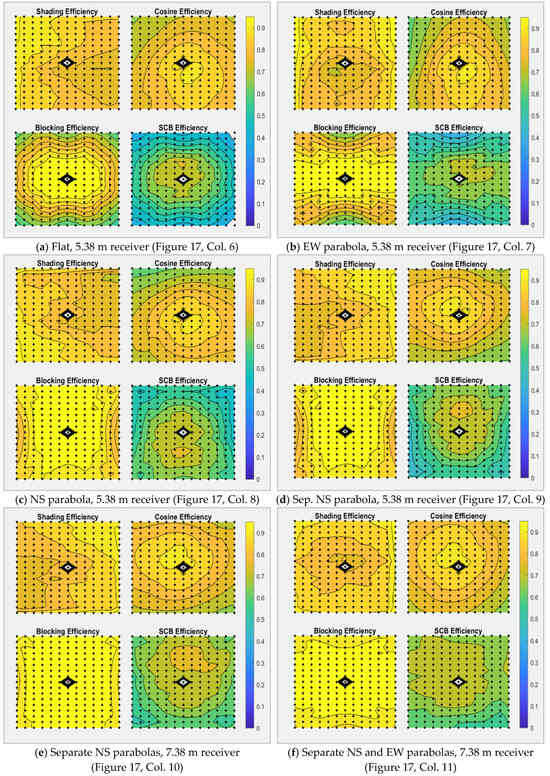

Figure 20 shows contour plots for some of the 220-Max Tilt–Roll heliostat layouts shown in Figure 17, with (e,f) especially showing bigger islands of higher blocking and SCB Efficiencies.

Figure 20.

Shading, cosine, blocking, and SCB Efficiency contour plots for the 220-Max Tilt–Roll heliostat layouts in Figure 17.

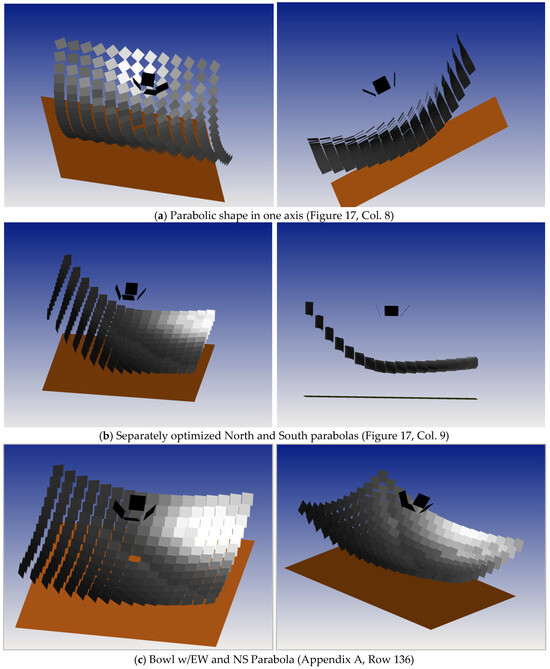

Figure 21 shows 3D CAD figures of various non-flat heliostat field topographies with heliostats in their post-simulation orientations.

Figure 21.

Three-dimensional CAD drawings of sample non-flat topographies, shown post-simulation, with heliostats oriented to reflect the sun’s rays onto the receivers.

3.3. Summary of Optimization for Non-Flat Topographies with Tilt–Roll Heliostats

The heliostat field modifications in Figure 17, culminating in Column 11 (220-Max heliostat layout with separately optimized North and South parabolic constants), yield a 57.7% improvement in Effective SCB Area and a similar increase in annualized receiver energy over the base 160-heliostat scenario. Of this increase, approximately 40% is due to modifying the flat heliostat layout to increase the quantity and size of the heliostats, 10% is due to non-flat topography improvements, and 7% is due to the mild increase in receiver height.

These combined efficiency improvements yield significant gains in the amount of DNI which can be collected within a bounded rooftop area and put to practical use, greatly improving the effectiveness of the solar thermal system by maximizing solar energy collection and utilization and the reduction in polluting conventional fuels and energy sources with ever-increasing energy costs.

3.4. Comparison with Azimuth–Elevation Heliostats

To briefly compare between Tilt–Roll and Azimuth–Elevation heliostat types, Table 5 shows three flat heliostat field layouts of 1.5 m × 1.5 m Az-El heliostats, which were generated in SolarPILOT using different layout optimization algorithms, compared with two different flat heliostat field layouts of the Tilt–Roll heliostats of the same size, as described earlier. These scenarios all fit within the same 26 m × 26 m bounded area, leaving the approximate same area open for the receivers.

Table 5.

Comparison of annualized Effective SCB Area for Tilt–Roll vs. Az/El heliostat fields.

Amongst the Az-El scenarios evaluated, the 113 heliostat radial stagger layout has the highest Effective SCB Area of 133 m2 due to higher blocking efficiency, even though it has fewer heliostats than the maximum dense packing of 137 heliostats. As previously shown in Figure 17, the 220 heliostat Tilt–Roll layout with North–South initial rotation has an Effective SCB Area of 271 m2, which is 2.04 times higher than the best-case result for Az-El. The last row, not shown in Figure 17 for brevity, uses 220 Tilt–Roll heliostats in the alternate rotation scenario and gains more in shading efficiency than it loses in blocking efficiency, for an Effective SCB Area of 281 m2, which is 2.11 times higher than that in the best-case Az-El scenario evaluated.

This illustrates that the use of Tilt–Roll heliostats in the rooftop scenario can more than double the amount of annualized optical energy potentially available at the receiver(s) vs. using the same-sized, traditional Azimuth–Elevation heliostats. While not within the scope of discussion here, it is theorized that Tilt–Roll heliostat articulations may present a smaller aperture with regard to blocking and shading than Az-El heliostats, which are always upright.

4. Discussion

The approximately 10% (5.4% net) efficiency improvement seen due to non-flat heliostat field topography modifications is meaningful, especially in the context of the 1% to 15% total optical efficiency gains typically seen in well-accepted heliostat layout optimization papers such as [34,35,36]. The costs to implement this over a rooftop-scale area would be feasible and likely recoverable with the energy gains, especially in regions of the world with low fabrication and labor costs.

Tilt–Roll heliostats enable significantly tighter packing than typical Azimuth–Elevation heliostats, with the potential to double gains in annual energy at the receiver within a bounded system. Tightly packing the Tilt–Roll heliostats resulted in a significant increase in Effective SCB Area and consequently in annualized energy at the receivers. SCB Efficiency was reduced with the denser layouts, as expected since blocking and shading losses went up. This was more than counteracted by the increased heliostat area, which led to a 40% higher Effective SCB Area over the base scenario. Including parabolic, non-flat heliostat field topographies facilitates additional 10% improvements in efficiency and annual energy.

Making rooftop-scale systems more powerful, compact, and efficient enables the concentration of solar thermal energy to meet the needs of a greater range of industrial applications and scenarios than is possible today, especially amidst rising energy costs and growing pressure to reduce GHG emissions. Since a rooftop solar thermal system can rarely meet industrial process heat needs alone, maximizing the annual solar thermal energy capture within a bounded space has the important effect of offsetting the most polluting, non-renewable resources, creating a healthier future for everyone. At the same time, this increases the resiliency of communities and institutions in the face of natural disasters and energy shortages [79].

The use of central receiver systems for rooftop-scale solar applications for industrial processes permits the inclusion of distributed groups of heliostats, which can be placed on multiple buildings and levels without the need for piping between them; only the central receivers need piping. The developed custom, novel simulation tool enables the evaluation of these non-flat and distributed heliostat field layout scenarios, along with the usage of alternative heliostat types such as Tilt–Roll.

Additional research into highly compact and efficient CSP central receiver systems could include (1) the further optimization of heliostat size and surface shape, e.g., flat, canted, parabolic, square, or hexagonal shapes, etc.; (2) the optimization of heliostat layouts, including quantity, arrangement pattern, surface-based spacing, non-standard orientation and articulation axes, and the location of the tower; (3) researching distributed heliostat layouts on multiple buildings for urban solar thermal process heat scenarios; (4) implementing a simulation space, as per [12], to improve data fidelity over a simulated day; and (5) fuller development of the benefits of Tilt–Roll vs. Azimuth–Elevation heliostats, including indicated blocking and shading benefits. As more research is focused on rooftop-scale CSP systems, additional innovations will come to light, increasing the feasibility and sustainability of industrial process heat.

5. Conclusions

This work significantly extends the understanding of methods of maximizing annual energy production for rooftop-scale solar thermal systems. Useful metrics are defined, aiding in the evaluation of high spatial utilization systems. Innovative, non-flat topographies for tightly packed Tilt–Roll heliostat field layouts are systematically analyzed and understood. Novel methods of rooftop-scale CSP simulation and analysis were developed and validated to facilitate this research, resulting in numerous insights.

A doubling in annual energy production was shown for tightly packed Tilt–Roll heliostat vs. conventional Azimuth–Elevation heliostats of the same size. An additional 10% improvement can be gained by using simple, non-flat heliostat field topographies that are feasible at a rooftop scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.; methodology, J.F. and W.S.; software, J.F.; validation, J.F. and W.S; formal analysis, J.F.; investigation, J.F.; resources, K.A.; data curation, J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.; writing—review and editing, J.F. and K.A.; visualization, J.F.; supervision, K.A. and W.S.; project administration, K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express sincere gratitude to the Mata Amritanadamayi Devi for suggesting research with potential to help the environment and for support driving the work to completion. Acknowledgement goes to William (Bill) Hamilton of the NREL for help modifying and using SolarPILOT and SolTrace. After this work was underway, the NREL released SolarPILOT and SolTrace as open-source software, including a SolTrace-API with modern graphics capabilities, enabling potential future development for alternative heliostat configurations. Gracious thanks to Helena Wolfe for implementing the custom heliostat illustrations. Ansys OpticStudio helped make this work possible by providing a short-term, free-of-cost academic license.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Abbreviated Simulation Data

Table A1.

Abbreviated simulation data to compare and optimize the Tilt–Roll heliostat field layouts. All simulations run for the cardinal days of 3/21, 6/21, 9/21, & 12/21 unless otherwise noted.

Table A1.

Abbreviated simulation data to compare and optimize the Tilt–Roll heliostat field layouts. All simulations run for the cardinal days of 3/21, 6/21, 9/21, & 12/21 unless otherwise noted.

| Number | Initial Heliostat Articulation | South Shape | South Shape Constant | North Shape | North Shape Constant | East–West Shape | East–West Shape Constant | Bowl Calculation Type | Receiver Height (m) | Number of Heliostats | Heliostat Length (y-axis, m) | Heliostat Width (x-axis, m) | Latitude North (Degrees) | Shading Efficiency (%) | Cosine Efficiency (%) | Blocking Efficiency (%) | S × C × B Efficiency (%) | Effective SCB Area (m2) | Heliostat Density (%) | Annual Energy at the Receivers (kWh) | Solar Utilization (kWh/m2/year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 * | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.6 | 78.4 | 83.6 | 56.7 | 204 | 53.3 | 437,827 | 2591 |

| 2 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.5 | 78.2 | 83.6 | 55.9 | 201 | 53.3 | 436,985 | 2586 |

| 3 * | NS | Para | 0.005 | Para | 0.005 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.8 | 77.8 | 85.8 | 58.0 | 209 | 53.3 | 447,944 | 2651 |

| 4 * | NS | Para | 0.010 | Para | 0.010 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.8 | 77.3 | 87.9 | 59.0 | 212 | 53.3 | 456,240 | 2700 |

| 5 * | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.8 | 76.7 | 89.8 | 59.7 | 215 | 53.3 | 462,149 | 2735 |

| 6 * | NS | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.020 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.7 | 76.1 | 91.3 | 60.2 | 217 | 53.3 | 465,497 | 2754 |

| 7 * | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.4 | 75.4 | 92.5 | 60.3 | 217 | 53.3 | 465,886 | 2757 |

| 8 * | NS | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.2 | 74.8 | 93.2 | 60.0 | 216 | 53.3 | 463,948 | 2745 |

| 9 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0.025 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.5 | 78.2 | 83.6 | 55.9 | 201 | 53.3 | 436,985 | 2586 |

| 10 * | NS | Linear | 0.360 | Linear | 0.360 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.4 | 73.0 | 82.3 | 51.9 | 187 | 53.3 | 398,447 | 2358 |

| 11 * | NS | Linear | 0.300 | Linear | 0.300 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.6 | 74.0 | 82.9 | 53.2 | 192 | 53.3 | 407,566 | 2412 |

| 12 * | NS | Linear | 0.250 | Linear | 0.250 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 86.8 | 74.9 | 83.3 | 54.1 | 195 | 53.3 | 414,668 | 2454 |

| 13 | NS | Linear | 0.250 | Linear | 0.250 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.9 | 74.8 | 83.4 | 53.6 | 193 | 53.3 | 414,265 | 2451 |

| 14 | NS | Linear | 0.250 | Linear | 0.250 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 4.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.8 | 76.9 | 90.0 | 59.5 | 214 | 53.3 | 464,234 | 2747 |

| 15 | NS | Linear | 0.250 | Linear | 0.250 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.8 | 78.8 | 94.2 | 63.7 | 229 | 53.3 | 501,551 | 2968 |

| 16 | NS | Linear | 0.250 | Linear | 0.250 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 6.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.8 | 80.3 | 96.9 | 66.7 | 240 | 53.3 | 528,442 | 3127 |

| 17 | NS | Linear | 0.250 | Linear | 0.250 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.6 | 81.6 | 98.4 | 68.8 | 248 | 53.3 | 547,233 | 3238 |

| 18 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 3.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.6 | 78.0 | 84.8 | 56.6 | 204 | 53.3 | 442,262 | 2617 |

| 19 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 4.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.6 | 79.7 | 90.7 | 61.9 | 223 | 53.3 | 489,081 | 2894 |

| 20 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.6 | 81.2 | 94.5 | 65.7 | 237 | 53.3 | 522,975 | 3095 |

| 21 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 6.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.6 | 82.4 | 97.0 | 68.4 | 246 | 53.3 | 547,064 | 3237 |

| 22 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.6 | 83.3 | 98.4 | 70.2 | 253 | 53.3 | 564,191 | 3338 |

| 23 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 8.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.6 | 83.8 | 99.0 | 71.1 | 256 | 53.3 | 571,574 | 3382 |

| 24 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 9.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.7 | 84.6 | 99.6 | 72.2 | 260 | 53.3 | 581,621 | 3442 |

| 25 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 10.83 | 160 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.7 | 85.2 | 99.9 | 73.0 | 263 | 53.3 | 588,560 | 3483 |

| 26 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 4.83 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.0 | 80.2 | 87.6 | 57.6 | 252 | 64.6 | 549,039 | 3249 |

| 27 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 84.0 | 81.0 | 89.6 | 61.0 | 266 | 64.6 | 582,500 | 3447 |

| 28 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.0 | 81.0 | 90.1 | 59.9 | 261 | 64.6 | 575,000 | 3402 |

| 29 | NS | Para | 0.005 | Para | 0.005 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.2 | 80.6 | 91.9 | 60.9 | 266 | 64.6 | 584,539 | 3459 |

| 30 | NS | Para | 0.010 | Para | 0.010 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.4 | 80.1 | 93.4 | 61.7 | 269 | 64.6 | 590,499 | 3494 |

| 31 | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.4 | 79.7 | 94.4 | 62.0 | 271 | 64.6 | 592,097 | 3504 |

| 32 | NS | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.020 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.3 | 79.2 | 95.1 | 61.9 | 270 | 64.6 | 589,213 | 3486 |

| 33 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.005 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.7 | 80.6 | 91.4 | 60.9 | 266 | 64.6 | 585,908 | 3467 |

| 34 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.010 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.2 | 80.1 | 92.6 | 61.7 | 269 | 64.6 | 593,828 | 3514 |

| 35 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.5 | 79.6 | 93.7 | 62.3 | 272 | 64.6 | 598,586 | 3542 |

| 36 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.020 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.8 | 79.1 | 94.5 | 62.6 | 273 | 64.6 | 600,013 | 3550 |

| 37 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.9 | 78.5 | 95.1 | 62.7 | 274 | 64.6 | 598,301 | 3540 |

| 38 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.030 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 84.0 | 78.0 | 95.6 | 62.6 | 273 | 64.6 | 593,985 | 3515 |

| 39 | EW | Para | 0.005 | Para | 0.005 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 84.4 | 80.6 | 91.5 | 62.2 | 271 | 0.0 | 594,139 | 3516 |

| 40 | EW | Para | 0.010 | Para | 0.010 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 84.6 | 80.1 | 93.1 | 63.1 | 276 | 0.0 | 603,133 | 3569 |

| 41 | EW | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 84.6 | 79.7 | 94.5 | 63.7 | 278 | 0.0 | 608,150 | 3599 |

| 42 | EW | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 84.5 | 79.2 | 95.6 | 63.9 | 279 | 0.0 | 608,491 | 3601 |

| 43 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.020 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 84.3 | 78.7 | 96.2 | 63.8 | 278 | 0.0 | 605,291 | 3582 |

| 44 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.005 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 84.8 | 80.5 | 90.9 | 62.1 | 271 | 0.0 | 592,555 | 3506 |

| 45 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.010 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.3 | 80.1 | 92.0 | 62.8 | 274 | 0.0 | 599,159 | 3545 |

| 46 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.7 | 79.5 | 92.9 | 63.3 | 276 | 0.0 | 601,864 | 3561 |

| 47 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.020 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.9 | 79.0 | 93.5 | 63.4 | 277 | 0.0 | 600,746 | 3555 |

| 48 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 5.38 | 194 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 85.9 | 78.4 | 93.9 | 63.3 | 276 | 0.0 | 596,019 | 3527 |

| 49 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 4.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 81.9 | 80.3 | 82.8 | 54.5 | 270 | 73.2 | 581,716 | 3442 |

| 50 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 81.9 | 81.1 | 85.4 | 56.7 | 281 | 73.2 | 611,042 | 3616 |

| 51 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 81.9 | 81.7 | 87.1 | 58.3 | 289 | 73.2 | 632,051 | 3740 |

| 52 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 6.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.0 | 82.8 | 90.1 | 61.2 | 303 | 73.2 | 669,830 | 3963 |

| 53 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.0 | 83.7 | 92.2 | 63.3 | 313 | 73.2 | 697,527 | 4127 |

| 54 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 8.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 81.9 | 84.5 | 93.8 | 65.0 | 322 | 73.2 | 719,013 | 4255 |

| 55 | EW | Para | 0.005 | Para | 0.005 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.2 | 80.7 | 87.5 | 58.0 | 287 | 73.2 | 625,453 | 3701 |

| 56 | EW | Para | 0.010 | Para | 0.010 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.4 | 80.3 | 89.5 | 59.2 | 293 | 73.2 | 637,648 | 3773 |

| 57 | EW | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.4 | 79.8 | 91.4 | 60.1 | 298 | 73.2 | 647,497 | 3831 |

| 58 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.020 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.4 | 79.3 | 93.1 | 60.8 | 301 | 73.2 | 653,762 | 3868 |

| 59 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.3 | 78.8 | 94.4 | 61.2 | 303 | 73.2 | 656,028 | 3882 |

| 60 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.1 | 78.3 | 95.4 | 61.3 | 304 | 73.2 | 654,364 | 3872 |

| 61 | EW | Para | 0.035 | Para | 0.035 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 81.8 | 77.8 | 96.0 | 61.1 | 302 | 73.2 | 648,329 | 3836 |

| 62 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 4.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.3 | 77.9 | 92.6 | 59.3 | 294 | 73.2 | 629,599 | 3725 |

| 63 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.2 | 79.5 | 95.6 | 62.5 | 310 | 73.2 | 674,591 | 3992 |

| 64 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 6.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.2 | 80.9 | 97.5 | 64.8 | 321 | 73.2 | 706,597 | 4181 |

| 65 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.1 | 82.1 | 98.5 | 66.4 | 329 | 73.2 | 728,828 | 4313 |

| 66 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 8.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.0 | 83.1 | 99.1 | 67.5 | 334 | 73.2 | 744,640 | 4406 |

| 67 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 9.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 81.9 | 83.9 | 99.5 | 68.4 | 339 | 73.2 | 756,191 | 4475 |

| 68 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.005 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.7 | 80.7 | 86.5 | 57.7 | 286 | 73.2 | 622,036 | 3681 |

| 69 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.010 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.3 | 80.2 | 87.4 | 58.3 | 289 | 73.2 | 629,399 | 3724 |

| 70 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.6 | 79.7 | 88.1 | 58.7 | 290 | 73.2 | 632,534 | 3743 |

| 71 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.020 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.8 | 79.1 | 88.6 | 58.7 | 291 | 73.2 | 631,344 | 3736 |

| 72 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.7 | 78.6 | 88.8 | 58.4 | 289 | 73.2 | 625,242 | 3700 |

| 73 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 4.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.7 | 78.8 | 86.1 | 56.8 | 281 | 73.2 | 607,509 | 3595 |

| 74 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 5.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.5 | 80.3 | 89.4 | 60.0 | 297 | 73.2 | 649,668 | 3844 |

| 75 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 6.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.3 | 81.6 | 91.4 | 62.2 | 308 | 73.2 | 679,258 | 4019 |

| 76 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 7.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.2 | 82.7 | 92.7 | 63.8 | 316 | 73.2 | 700,190 | 4143 |

| 77 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 8.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 83.0 | 83.6 | 93.6 | 65.0 | 322 | 73.2 | 716,651 | 4241 |

| 78 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 9.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 82.9 | 84.4 | 94.5 | 66.1 | 327 | 73.2 | 730,515 | 4323 |

| 79 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 4.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.7 | 80.4 | 84.4 | 52.7 | 261 | 73.2 | 567,384 | 3357 |

| 80 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.6 | 81.1 | 87.1 | 54.8 | 271 | 73.2 | 595,916 | 3526 |

| 81 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.5 | 81.7 | 89.0 | 56.4 | 279 | 73.2 | 616,349 | 3647 |

| 82 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 6.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.4 | 82.8 | 92.2 | 59.1 | 292 | 73.2 | 652,760 | 3862 |

| 83 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.2 | 83.7 | 94.4 | 61.1 | 302 | 73.2 | 679,281 | 4019 |

| 84 | NS | Para | 0.005 | Para | 0.005 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.8 | 80.7 | 89.0 | 55.9 | 277 | 73.2 | 606,705 | 3590 |

| 85 | NS | Para | 0.010 | Para | 0.010 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.9 | 80.3 | 90.5 | 56.6 | 280 | 73.2 | 613,756 | 3632 |

| 86 | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 78.0 | 79.8 | 91.5 | 56.9 | 282 | 73.2 | 616,096 | 3646 |

| 87 | NS | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.020 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.8 | 79.3 | 92.1 | 56.8 | 281 | 73.2 | 613,267 | 3629 |

| 88 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.005 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 78.2 | 80.7 | 88.5 | 55.8 | 276 | 73.2 | 608,775 | 3602 |

| 89 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.010 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 78.7 | 80.2 | 89.8 | 56.7 | 281 | 73.2 | 619,138 | 3664 |

| 90 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 79.1 | 79.8 | 91.1 | 57.4 | 284 | 73.2 | 627,234 | 3711 |

| 91 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.020 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 79.5 | 79.2 | 92.3 | 58.1 | 288 | 73.2 | 633,057 | 3746 |

| 92 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 79.8 | 78.7 | 93.4 | 58.6 | 290 | 73.2 | 635,750 | 3762 |

| 93 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.030 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 80.1 | 78.1 | 94.4 | 59.0 | 292 | 73.2 | 635,498 | 3760 |

| 94 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.035 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 80.3 | 77.6 | 94.9 | 59.1 | 292 | 73.2 | 632,056 | 3740 |

| 95 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 4.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 80.0 | 77.8 | 91.1 | 56.7 | 281 | 73.2 | 610,172 | 3610 |

| 96 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 5.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 79.6 | 79.4 | 94.9 | 60.0 | 297 | 73.2 | 653,662 | 3868 |

| 97 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 6.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 79.2 | 80.8 | 97.1 | 62.2 | 308 | 73.2 | 684,248 | 4049 |

| 98 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 7.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 78.9 | 82.0 | 98.4 | 63.7 | 315 | 73.2 | 705,430 | 4174 |

| 99 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 8.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 78.7 | 83.0 | 99.1 | 64.8 | 321 | 73.2 | 719,961 | 4260 |

| 100 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 9.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 78.5 | 83.9 | 99.5 | 65.6 | 324 | 73.2 | 730,696 | 4324 |

| 101 | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 4.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 78.0 | 78.9 | 89.6 | 55.2 | 273 | 73.2 | 592,748 | 3507 |

| 102 | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.9 | 80.4 | 92.7 | 58.1 | 287 | 73.2 | 631,826 | 3739 |

| 103 | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 6.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.7 | 81.7 | 94.4 | 60.0 | 297 | 73.2 | 658,725 | 3898 |

| 104 | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.5 | 82.8 | 95.5 | 61.3 | 303 | 73.2 | 678,392 | 4014 |

| 105 | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 8.83 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15.55 | 77.4 | 83.7 | 96.3 | 62.4 | 309 | 73.2 | 694,403 | 4109 |

| 106 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 76.6 | 81.2 | 85.1 | 53.0 | 284 | 79.3 | 618,969 | 3663 |

| 107 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.005 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 77.2 | 80.8 | 86.5 | 53.9 | 289 | 0.0 | 632,379 | 3742 |

| 108 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.010 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 77.7 | 80.3 | 87.7 | 54.7 | 294 | 0.0 | 643,203 | 3806 |

| 109 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 78.1 | 79.8 | 88.9 | 55.5 | 297 | 79.3 | 651,811 | 3857 |

| 110 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.020 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 78.5 | 79.3 | 90.1 | 56.1 | 301 | 79.3 | 658,099 | 3894 |

| 111 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 78.9 | 78.7 | 91.2 | 56.6 | 304 | 79.3 | 661,329 | 3913 |

| 112 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.030 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 79.1 | 78.2 | 92.3 | 57.1 | 306 | 79.3 | 661,905 | 3917 |

| 113 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.035 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 79.3 | 77.6 | 93.0 | 57.2 | 307 | 79.3 | 659,667 | 3903 |

| 114 | NS | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.040 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 79.5 | 77.0 | 93.4 | 57.1 | 306 | 79.3 | 654,355 | 3872 |

| 115 | NS | Para | 0.005 | Para | 0.005 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 77.0 | 80.8 | 87.0 | 54.1 | 290 | 79.3 | 631,865 | 3739 |

| 116 | NS | Para | 0.010 | Para | 0.010 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 77.2 | 80.3 | 88.8 | 55.0 | 295 | 79.3 | 641,975 | 3799 |

| 117 | NS | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 77.2 | 79.9 | 90.2 | 55.6 | 298 | 79.3 | 647,666 | 3832 |

| 118 | NS | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.020 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 77.0 | 79.4 | 91.2 | 55.8 | 299 | 79.3 | 648,321 | 3836 |

| 119 | NS | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 76.8 | 78.8 | 91.8 | 55.6 | 298 | 79.3 | 643,549 | 3808 |

| 120 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.0 | 81.2 | 83.8 | 54.4 | 292 | 79.3 | 631,560 | 3737 |

| 121 | EW | Para | 0.005 | Para | 0.005 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.3 | 80.8 | 85.9 | 55.7 | 299 | 79.3 | 646,823 | 3827 |

| 122 | EW | Para | 0.010 | Para | 0.010 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.5 | 80.3 | 87.9 | 56.9 | 305 | 79.3 | 659,770 | 3904 |

| 123 | EW | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.015 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.6 | 79.9 | 89.8 | 57.8 | 310 | 79.3 | 670,291 | 3966 |

| 124 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.020 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.5 | 79.4 | 91.5 | 58.5 | 314 | 79.3 | 677,363 | 4008 |

| 125 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.4 | 78.9 | 92.9 | 59.0 | 316 | 79.3 | 680,495 | 4027 |

| 126 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.3 | 78.4 | 94.0 | 59.1 | 317 | 79.3 | 679,762 | 4022 |

| 127 | EW | Para | 0.035 | Para | 0.035 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.1 | 77.8 | 94.6 | 59.0 | 316 | 79.3 | 675,054 | 3994 |

| 128 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.005 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.7 | 80.7 | 84.9 | 55.4 | 297 | 79.3 | 643,514 | 3808 |

| 129 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.010 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.3 | 80.3 | 85.9 | 56.0 | 300 | 79.3 | 652,383 | 3860 |

| 130 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.015 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.7 | 79.8 | 86.7 | 56.5 | 303 | 79.3 | 657,868 | 3893 |

| 131 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.020 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 82.0 | 79.2 | 87.3 | 56.7 | 304 | 79.3 | 659,807 | 3904 |

| 132 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.025 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 82.1 | 78.7 | 87.8 | 56.7 | 304 | 79.3 | 657,408 | 3890 |

| 133 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Para | 0.030 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 82.1 | 78.1 | 88.2 | 56.5 | 303 | 79.3 | 650,999 | 3852 |

| 134 | EW | Para | 0.035 | Para | 0.035 | Para | 0.025 | Max | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.3 | 76.6 | 94.7 | 58.9 | 316 | 79.3 | 673,660 | 3986 |

| 135 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.025 | Min | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.9 | 80.0 | 88.1 | 57.0 | 306 | 79.3 | 663,139 | 3924 |

| 136 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.025 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 82.1 | 78.6 | 92.1 | 59.4 | 319 | 79.3 | 690,366 | 4085 |

| 137 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.025 | Avg ** | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.5 | 77.5 | 93.4 | 59.0 | 316 | 79.3 | 678,235 | 4013 |

| 138 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.020 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.9 | 78.9 | 91.7 | 59.2 | 318 | 79.3 | 688,229 | 4072 |

| 139 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.015 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.6 | 79.1 | 91.4 | 59.0 | 316 | 79.3 | 685,013 | 4053 |

| 140 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.010 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.3 | 79.4 | 90.9 | 58.7 | 315 | 79.3 | 680,889 | 4029 |

| 141 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.005 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.9 | 79.6 | 90.4 | 58.3 | 312 | 79.3 | 675,987 | 4000 |

| 142 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.025 | Max | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.5 | 77.0 | 93.9 | 58.9 | 316 | 79.3 | 676,805 | 4005 |

| 143 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.020 | Max | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.3 | 77.4 | 94.0 | 59.2 | 318 | 79.3 | 681,426 | 4032 |

| 144 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.015 | Max | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.1 | 77.8 | 94.1 | 59.3 | 318 | 79.3 | 682,677 | 4040 |

| 145 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.010 | Max | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.8 | 78.1 | 94.1 | 59.4 | 318 | 79.3 | 683,062 | 4042 |

| 146 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.005 | Max | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.5 | 78.2 | 94.1 | 59.3 | 318 | 79.3 | 681,456 | 4032 |

| 147 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.025 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.500 | 15.55 | 83.2 | 77.0 | 95.1 | 60.9 | 301 | 73.2 | 645,665 | 3821 |

| 148 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.020 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.500 | 15.55 | 83.1 | 77.4 | 95.3 | 61.3 | 303 | 73.2 | 652,216 | 3859 |

| 149 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.015 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.500 | 15.55 | 82.9 | 77.7 | 95.5 | 61.5 | 304 | 73.2 | 655,160 | 3877 |

| 150 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.010 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.500 | 15.55 | 82.6 | 78.0 | 95.6 | 61.6 | 305 | 73.2 | 656,748 | 3886 |

| 151 | EW | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.030 | Para | 0.005 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.500 | 15.55 | 82.3 | 78.2 | 95.5 | 61.5 | 304 | 73.2 | 655,822 | 3881 |

| 152 | EW | Para | 0.035 | Para | 0.035 | Para | 0.010 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.500 | 15.55 | 82.4 | 77.5 | 96.2 | 61.4 | 304 | 73.2 | 651,657 | 3856 |

| 153 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.010 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.500 | 15.55 | 82.8 | 78.5 | 94.5 | 61.4 | 304 | 73.2 | 657,790 | 3892 |

| 154 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.010 | Avg | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.500 | 15.55 | 83.0 | 79.0 | 93.1 | 61.0 | 302 | 73.2 | 655,320 | 3878 |

| 155 | EW | Para | 0.035 | Para | 0.025 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 79.8 | 78.3 | 93.5 | 58.4 | 313 | 79.3 | 669,998 | 3964 |

| 156 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.035 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.7 | 78.4 | 94.2 | 59.6 | 320 | 79.3 | 685,375 | 4055 |

| 157 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.8 | 78.2 | 94.5 | 59.7 | 320 | 79.3 | 684,140 | 4048 |

| 158 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.045 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.8 | 77.9 | 94.7 | 59.6 | 320 | 79.3 | 681,201 | 4031 |

| 159 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.2 | 78.4 | 94.0 | 59.8 | 321 | 79.3 | 686,852 | 4064 |

| 160 | EW | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.5 | 78.7 | 93.2 | 59.8 | 321 | 79.3 | 687,385 | 4067 |

| 161 | EW | Para | 0.040 | Para | 0.020 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 79.3 | 78.2 | 92.7 | 57.5 | 308 | 79.3 | 657,319 | 3889 |

| 162 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.045 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 5.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.2 | 78.2 | 94.2 | 59.8 | 321 | 79.3 | 683,795 | 4046 |

| 163 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.9 | 81.3 | 97.6 | 64.2 | 344 | 79.3 | 755,567 | 4471 |

| 164 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 6.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 81.0 | 80.0 | 96.2 | 62.4 | 334 | 79.3 | 726,272 | 4297 |

| 165 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 8.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.8 | 82.4 | 98.4 | 65.5 | 351 | 79.3 | 777,231 | 4599 |

| 166 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.2 | 81.8 | 97.5 | 64.0 | 343 | 79.3 | 752,424 | 4452 |

| 167 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 8.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.1 | 82.9 | 98.4 | 65.3 | 350 | 79.3 | 776,482 | 4595 |

| 168 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Para | 0.030 | Avg | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 82.4 | 81.3 | 96.4 | 64.6 | 346 | 79.3 | 647,490 | 3831 |

| 169 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Para | 0.025 | Avg | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 82.3 | 81.5 | 96.4 | 64.6 | 347 | 79.3 | 768,198 | 4546 |

| 170 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Para | 0.020 | Avg | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 82.1 | 81.7 | 96.3 | 64.6 | 347 | 79.3 | 768,789 | 4549 |

| 171 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Avg | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 15.55 | 80.0 | 83.4 | 90.3 | 60.2 | 323 | 79.3 | 716,083 | 4237 |

| 172 | EW | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 35.0 | 72.8 | 81.4 | 92.4 | 54.8 | 294 | 79.3 | 686,972 | 4065 |

| 173 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.040 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 35.0 | 75.8 | 79.6 | 97.8 | 59.0 | 316 | 79.3 | 685,887 | 4059 |

| 174 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.045 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 35.0 | 76.0 | 79.5 | 97.9 | 59.1 | 317 | 79.3 | 683,667 | 4045 |

| 175 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.050 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 35.0 | 76.2 | 79.3 | 97.9 | 59.2 | 317 | 79.3 | 693,523 | 4104 |

| 176 | EW | Para | 0.015 | Para | 0.050 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 35.0 | 77.0 | 79.5 | 97.7 | 59.8 | 321 | 79.3 | 701,808 | 4153 |

| 177 | EW | Para | 0.010 | Para | 0.050 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 35.0 | 77.8 | 79.8 | 97.3 | 60.4 | 324 | 79.3 | 680,325 | 4026 |

| 178 | EW | Para | 0.020 | Para | 0.055 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 35.0 | 76.3 | 79.1 | 97.9 | 59.1 | 317 | 79.3 | 673,495 | 3985 |

| 179 | EW | Para | 0.025 | Para | 0.050 | Flat | 0 | n/a | 7.38 | 220 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 35.0 | 75.5 | 79.0 | 98.0 | 58.5 | 314 | 79.3 | 766,451 | 4535 |