Abstract

Energetic ionic liquids (EILs) have various industrial applications because they release chemically stored energy under certain conditions. They can avoid some environmental problems caused by traditionally used toxic fuels. EILs, which are environmentally friendly and safer, are emerging as an alternative source for hypergolic bipropellant fuels. This review focuses on the crucial thermophysical properties of the EILs. The properties of imidazolium and triazolium-based ionic liquids (ILs) are discussed here. The thermophysical properties addressed, such as glass transition temperature, viscosity, and thermal stability, are critical for designing EILs to meet the need for sustainable energy solutions. Imidazolium-based ILs have tunable physical properties making them ideal for use in energy storage while triazolium-based ILs have thermal stability and energetic potential. As a result, it is important to understand and compile thermophysical properties so they can help researchers synthesize tailored compounds with desirable characteristics, advancing their application in energy storage and propulsion technologies.

1. Introduction

Current research is focused on advancing the transition from conventional fuels to innovative green propellants with the aim of implementing them widely in spacecraft missions. These environmentally friendly alternatives promise a more sustainable approach to space missions, enhancing safety and paving the way for greener technological solutions. Human health and the environment are significantly impacted by the use of conventional fuels like hydrazine and nitric acid, used in rocket fuels. This crucial topic is explored by Nguyen and Chenoweth in their review [1,2,3]. Longtime contact with these chemicals has been linked with several types of cancer, neurological damage, and liver failure. Green propellants have emerged as a substitute for conventional toxic and carcinogenic propellants. Green propellants are less toxic, and cleaner, and will provide high performance when compared with traditional propellants for future spacecraft. Zhang and Shreeve [4,5,6,7] have studied the importance of energetic ionic liquids (EILs) as explosives and propellant fuels and have described this finding as a new journey in ionic liquid (IL) chemistry.

Propellants are energetic compounds (a mixture of gas, liquid, and solid states) that go through an immense combustion process and give rise to a massive amount of hot gases, which are utilized to push a rocket, missile, and launcher. Chemical propellants are categorized as solid, liquid, and cryogenic propellants. Additionally, liquid propellants are subdivided into monopropellants and bipropellants. The classification and the application of EILs in space propulsion are discussed by Kamal and others in their work [8,9,10,11,12].

Monopropellants are usually used in small missiles and satellites, which require comparatively low thrust. Monopropellants are single or multiple-component propellants and do not need any other propellants for their decomposition. Monopropellants can be stored in a single reservoir and can be decomposed with the aid of other catalysts or another ignition method such as thermal or electrical ignition [5,13,14]. Hydrazine has shown good performance for a long time, but it requires careful handling and transportation due to its toxicity, high volatility, and carcinogenic nature. As a result, it has raised the financial cost for the space industry. Monopropellants exhibit different disadvantages that lead to higher costs during their handling and storage, including (i) their high vapor pressure, (ii) their toxic and carcinogenic nature, (iii) their high crystallization point (2.0 °C for hydrazine), and (iv) their risk of detonation (sensitivity to adiabatic compression) [15,16,17].

Bipropellants are formed with the combination of two liquid components, a fuel (or reducer) and an oxidizer. These are stored individually, and when they meet one another in the combustion chamber, they can ignite naturally or by an ignition system. Bipropellants display higher energy content compared with monopropellants, with higher to moderate thrust and more effective propulsive performance. Bipropellants are used in large liquid rocket boosters, upper-stage propulsion modules, and spacecraft propulsion [18,19,20]. Current bipropellants that are commonly used are hydrazine, methanol, hydrogen, kerosene, monomethylhydrazine (MMH), and unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH). Oxidizers typically used are nitric acid and nitrogen tetroxide (N2O4), a mixed oxide of nitrogen, hydrogen peroxide, or liquid oxygen. Monopropellant hydrazine and its derivatives for bipropellant systems (MMH and UDMH) have been the most prevalent space propulsion system since the fifties [21,22]. There is no doubt that bipropellant hydrazine with a common oxidizer exhibits good performance and has a long functional history, for storage and handling it needs sophisticated and intricate procedures, and extensive safety precautions must be maintained by skilled operators. Thus, expanding safety concerns and the necessity for developing nontoxic propellants have led to the idea of green propellants and green propulsion, and considerable efforts have been made to obtain environmentally friendly and insensitive energetic materials [8,21,22,23,24]. Conventional MMH is still widely used for its reliability and performance; however, efforts are ongoing to replace it with green propellants. EILs fall under hypergolic propellants depending on their chemical composition and interactions with oxidizers. Triazolium and imidazolium-based EILs with energetic anions like dicyanamide or nitro groups are still under development in order to investigate their hypergolic behavior with oxidizers.

Energetic materials are compounds that have a substantial amount of energy stored in them and which are capable of release under certain circumstances (e.g., heat, shock, friction, and electrostatic discharge). EILs are mixed with a premixed oxidizer and with a fuel ionic propellant. The premixed oxidizers are salts that are dissolved in ILs. Ionic fuels or molecular fuels are referred to as ionic fuel propellants to finish the production of the premixed propellant [19,25]. As mentioned earlier, it is a goal to replace the propellant fuels that are being used today in space propulsion, such as hydrazine, that still exhibit comparable properties and performance. Ideal properties for a perfect propellant fuel include the following: an ionic fuel that ignites spontaneously with an oxidizer; thermal and moisture stability to ensure safe handling and long-term storage; resistance to impact and friction to minimize sensitivity-related risks; and a liquid state at room temperature to facilitate its use in liquid rocket engine [2,5,26]. There are some advantages of using EILs, such as low melting point, low viscosity, and high thermal stability, which have advantages when compared with conventional energetic materials. EILs have extremely low volatility and less chance of human exposure during handling and storage. Easy storage, handling, transportation, and processing of these materials are easier and safer, reducing the cost when compared with the complex and expensive handling cost of the previous propellants. The liquid energetic material can effectively avoid the polymorphism problem that may happen with solid energetic materials [19].

EILs as a green propellant are still comparatively new in research and still developing. However, a comprehensive understanding of their thermophysical properties remains limited, which hinders the processing and optimization of these propellants with the necessary knowledge [27]. Key properties, such as enthalpy of formation and heat of combustion, are important as they directly determine the energy released during application. In addition, understanding properties like density, melting temperature and phase behavior is essential to optimize the reliability and effectiveness of EIL-based systems. Gaining insight into these thermophysical properties can facilitate the development of compatible EILs with multiple oxidizers. This article, therefore, summarizes the thermophysical properties of EILs as documented in the relevant literature [19,28].

2. Types of EILs as Green Propellants

2.1. HAN, ADN, and HNF-Based Propellants

Hydroxylammonium nitrate (HAN), ammonium dinitramide (ADN), and hydroxylammonium nitrate fuel (HNF)-based propellants are the pioneering generation of EILs used in monopropellant applications. These propellants are characterized by their ionic compounds, typically utilized in concentrated aqueous solutions to control performance and the maximum achievable temperature in a controlled flow. Achieving a zero-oxygen balance ensures that the propellant contains an IL as an ionic oxidizer paired with a fuel. Due to their advantageous properties, these oxidizers are considered among the most promising [15,29,30].

The development of HAN-based propellant can be traced back to liquid gun propellant research conducted by the U.S. Army. Two main categories of HAN aqueous solutions are HAN/tri-ethanol-ammonium nitrate (HAN/TEAN) and HAN/di-ethyl hydroxyl ammonium nitrate (HAN/DEHAN). However, due to their relatively low combustion pressure, and higher combustion temperature, reaching 2227 °C these propellants are deemed unsuitable for rocket propulsion. To address these limitations the HAN-based green monopropellant, Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) is a high-performance green propellant invented at Air Force Research Laboratory in 1998, targeting space propulsion applications [31,32,33,34].

During decomposition, and when compared with hydrazine, Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) reaches a much higher temperature, around 1827 °C, whereas hydrazine releases about 926.8 °C. This characteristic makes Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) a better monopropellant. Additionally, Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) also boasts a 63% increase in density and a 13% rise in specific impulse compared with hydrazine. The propellant’s minimal toxicity hazards and good mixture stability in a range of temperature ranges, as well as its high solubility and low vapor pressure, ensures safety in storage and handling [35,36].

Despite the fact that Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) is an excellent green propellant, it has a drawback: its high flame temperature. This makes it difficult to produce cost-effective and simply designed thrusters, especially for small satellites [37,38]. However, continuous improvements are being made to make Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) even more beneficial for the spacecraft community.

Green electrical monopropellant (GEM) is composed of HAN, ADN, (2,2’-dipyridyl), (1,2,4-triazole), 1H-pyrazol, and water, and is another HAN-based EIL. The Digital Solid-State Propulsion Company (Reno, NV, USA) makes this EIL a superior replacement for Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) for use in a multi-mode propulsion system. A “multi-mode” system is a satellite propulsion system that defines a shared propellant tank that operates in two or multiple separate modes, such as an electric high-specific impulse mode and a chemical high-thrust mode. GEM is appealing as an EIL because it can be electrically ignited without any heavy catalytic beds while possessing a large volumetric specific impulse when compared with Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) [39,40].

Green monopropellants based on ADN mostly consist of fine liquid propellants (FLPs)—103, 105, 106, 107—and liquid monopropellants (LMPs)—103S—with FLP-106 and LMP-103S being the most generated. Fuels, such as methanol, monomethyl-formamide, and dimethyl-formamide are used to make these EILs. Ammonia is required to be placed in conjunction with methanol and ADN to raise the pH of the mixture, without the ammonia, methanol and ADN cannot be mixed together [41,42].

The ignition process for ADN-based green monopropellants can be undertaken thermally, electrically, or with heated catalytic beds. Resistive heating can be used to ignite these propellants by running an electrical current through them [43]. Glow plug ignition has successfully met the requirements for ignition behavior and decomposition for both LMP-103S and FLP-106 [44,45,46]. Lower combustion temperatures are one beneficial property of LMP-103S and the FLP series over the Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E). This allows for the development of thrusters using materials with lower melting temperatures and simpler designs for thruster development.

2.2. New EILs

Recent research is focused mostly on the growing interest and popularity of recently introduced EILs [4]. Those recent EILs should include the following properties: low viscosity, better stability, a surface tension of less than 100 dyne/cm, a density of more than 1.4 g/cm3, and a melting point of less than −40 °C [29,47,48].

The imidazolium, triazolium, and tetrazolium compounds with nitrogen and carbon substituents are the most recently used families of EILs [49,50]. For those new propellants, it is crucial to achieve zero oxygen balance. Among these, 1-ethyl-4,5-dimethyltetrazolium tetranitroaluminate, 1,5-diamino-4-methyltetrazolium hexanitrolanthanate, and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetranitroborate are some examples of newly synthesized EILs [51].

2.3. Potential Applications of EILs as Green Propellants in Different Fields

2.3.1. Space Propulsion

Researchers have recently become interested in exploring the various applications of currently used EILs [48]. For example, HAN-based monopropellants, which have been used in the development of liquid gun propellants, were found to be unsuitable for rocket propulsion because of their low combustion pressure. This enables a path to the further development of Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) which is a HAN-based green monopropellant created by the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory for space propulsion applications [16,52]. AF-M315E underwent extensive development and was tested on 1 N and 22 N thrusters in space through the Green Propellant Infusion Mission, launched in 2019 on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy Rocket, USA. Since 2000, SHP163, which is a HAN-based green propellant has been manufactured for space propulsion at the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS) in Japan. It is composed of 73.6 wt.% HAN, 3.9 wt.% ammonium nitrate, 16.3 wt.% methanol, and 6.2 wt.% water [39,53]. This propellant has a density of 1.4 g/cm3 and can gain a high volumetric specific impulse of 396 g·s/cm3, which beats Air Force Monopropellant 315E (AF-M315E) in comparable situations (0.7 MPa chamber pressure and 50:1 nozzle expansion ratio at freezing conditions). SHP163 is well known for its safe, stable and improved high-energy performance. A 1 N class thruster was used on the RAPIS-1 satellite, which was launched by Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) in 2019, SHP163 was investigated in space as a compound of the Green Propellant Reaction Control System [32,53,54].

New EILs from the families of imidazolium, triazolium, and tetrazolium are being created for monopropellant applications in space propulsion. One of the potential anions for these liquid propellants is 3,5-dinitro-1,2,4-triazolate. Several EILs incorporating this anion, as well as others, are now under development for their better performance in space propulsion applications [53].

2.3.2. Military

EILs have been investigated as potential new explosives and propellants, with a broader range of military and industrial uses. They show potential for several practical benefits in applications when compared with conventional propellants in military applications. These benefits are improved efficiency, payload capacity, and precision in rocket propulsion systems [53,55].

EILs can be used in making weapons, explosives, and safe propellants because of their better resistance to stress and impact. Furthermore, they can also be used in energy storage systems and missile guidance systems, highlighting their versatility in various military contexts. The physicochemical properties of EILs are crucial in influencing the performance of EILs. Further research and improvement are necessary to maximize their application in military technology [15,56].

2.3.3. Civilian

Compared with the previous conventional fossil fuels, which are less efficient and more harmful to the environment, EILs can produce electricity in a cleaner, more efficient way. EILs have a melting temperature below 100 °C and consist solely of ions. Those properties make ILs suitable for numerous applications such as transportation in airplanes and cars, as they can help reduce pollutants and increase fuel efficiency [55,57].

EILs offer promising advancements in energy storage systems. Their low vapor pressure and high thermal stability make them potential candidates for use in electrochemical energy storage and conversion systems [58,59]. This opens the way for the creation of more green and efficient energy storage solutions. Additionally, EILs offer several advantages, including high energy density, better thermal stability, less toxicity, and low hygroscopicity. These properties reduce the risks associated with handling and storage and make EILs a safer alternative. Further study and innovation are required to realize their potential fully [60,61].

2.4. Comparison of the Performance of EILs with Conventional Propellants

Compared with traditional propellants, EILs are better in several important areas, such as effectiveness, safety, and environmental impact. EILs provide increased energy density when compared with traditional propellants and give more specific impulse and payload capacity, which is essential in aerospace and military applications. Zhang and Shreeve [4] have pointed out these potentials in their review of EILs, describing them as a significant advancement in IL chemistry. They show greater burning rates or enhanced thermal stability, properties which are made possible because EILs may be adapted to meet the needs of various applications. The disadvantage of EILs is that they may have a lower density than conventional propellants, leading to less thrust and reduced overall performance.

EILs have some safety benefits for military applications, such as resistance to shock and stress, reducing the possibility of unwanted explosion. In military applications, where safety is crucial, these properties are vital. Hypergolic EILs could be a promising alternative to the commonly used hydrazine. Hypergolic EILs possess several desirable features including low vapor pressure, resistance to outside factors, negligible corrosivity, low inflammability, low toxicity, and ease of handling. This low toxicity and hygroscopicity make hypergolic EILs easier to handle and store, while also reducing their environmental impact. Secure storage and handling are crucial for both military and civil uses. Compared with hydrazine, which has been used commonly for a long time, hypergolic ILs could be a better alternative because of their excellent characteristics [62,63].

Hypergolic EILs combine the qualities of conventional fuels with the hypergolic qualities required for liquid bipropellants. There is much consideration currently ongoing in this new field to the creation of safer and more effective propellants for use in the military and commercial industries.

EILs have some environmental advantages over traditional propellants. They can be produced with less harm to the environment by incorporating renewable resources in exchange for fossil fuels. Additionally, EILs generate fewer pollutants and reduce greenhouse gas emissions [4]. This reduction in emissions is significant for civilian applications with a major environmental impact, including transportation and electricity production.

EILs are less damaging to the environment, which makes handling and storing them easier and less likely to pollute the environment. EILs offer a more ecologically friendly substitute for conventional propellants and have the ability to greatly reduce the environmental impact of a range of industrial and commercial operations [5,19,30].

Conventional propellants provide greater density and thrust, but they have low energy density. Conventional propellants are sensitive to certain factors such as unintentional ignition or explosion due to shock and impact [64,65]. Additionally, they further raise the risk of environmental contamination and air pollution. EILs are more efficient than conventional fuels, less toxic, and have less environmental impact. However, before EILs are commercially accepted as a better choice of propellants, there are still challenges that need to be addressed. These difficulties need to be decreased in order to enhance their performance, to make their synthesis procedures easy, and to ensure their safety and compatibility with other materials. While EILs show promise as environmentally friendly propellants, further study is required to realize their potential fully [4].

2.5. Case Studies and Experimental Results of EIL Applications

Many case studies and experimental findings have found the potential of EILs as environmentally friendly propellants. Below are some notable examples.

2.5.1. Space Propulsion

Scientists have researched and investigated the effective use of EILs as monopropellants for spacecraft. EILs have been synthesized and investigated for parameters that include impulse and burn rate [4]. These EILs have high density and an appropriately high decomposition temperature. The findings ensure that the EILs are thermally stable and have a high specific impulse, making them a good alternative to conventional monopropellants. This research expresses the potential of EILs to replace traditional propellants with enhanced efficiency and reduced environmental impact [66,67].

2.5.2. Military Applications

A recent study has shown EILs to be an efficient propellant for mortar systems. The stabilizer chamber of the mortar round served as the primary ignition charge in these investigations [68]. The burn rate and mechanical stress sensitivity are important characteristics that have been studied for a variety of EILs. Researchers have found that EILs are a good alternative to conventional mortar propellants because they burn quickly and are not sensitive. Therefore, EILs can provide improved safety and better performance for military use [66].

2.5.3. Power Generation

In the field of power production, it has been found that EILs perform well in solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). The relevant work synthesized ILs and investigated the power output and durability of these liquids [68]. According to Zhang and Shreeve’s [4] findings, EILs show strong high-power output, making them a suitable substitute for traditional fossil fuels in SOFCs.

ILs have some important characteristics, including strong electric conductivity, better thermal stability, low melting point, strong polarity, low volatility, and structural designability, among other beneficial physicochemical characteristics. Because of these excellent qualities, ILs are suitable choices for broader uses, such as organic reaction solvents. Compared with conventional organic solvents, ILs pose a number of advantages, including versatility, reusable catalysts, and easier product recovery. All of these properties make chemical reactions a more environmentally sustainable process [69,70,71].

2.5.4. Transportation

Zhang and Shreeve’s [4] research indicates that EILs can work as internal combustion engines [4]. These EILs have shown the capability for propellant applications such as pumping fluids, shredding wires and fasteners, starting aviation engines, and driving turbines. Various experiments have ensured EIL’s characteristics on fuel economy and energy density. Their study shows that EILs are a great replacement due to their energy density and fuel efficiency when compared with traditional fuels.

The informative findings of these experiments and case studies demonstrate the importance of EILs as environmentally friendly propellants. EILs have the potential to be widely adopted as green propellants in the field of various applications. However, further research is still required to improve their performance characteristics and ensure their use with other materials. This current research will be mandatory for realizing the full potential of EILs in practical implications [4,19].

2.6. Thermophysical Properties of EILs

Understanding the thermophysical properties of EILs is crucial to ensure proper handling, better transportation, effective application, and minimum environmental impact. These properties, including density, viscosity, and volatility, serve as important parameters for safe storage and handling, thermal stability and strength of the component, the optimal condition for the manufacturing process, and their different applications.

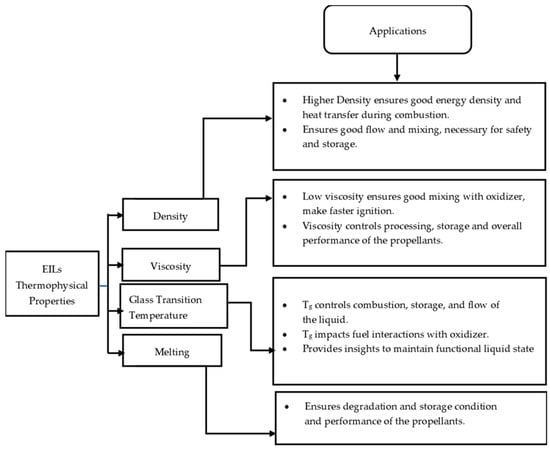

Figure 1 shows the thermophysical properties of EILs and their importance in various applications. Understanding the glass transition temperature (Tg) of EILs ensures stability under operational conditions, helping to prevent vaporization or crystallization in critical applications. Viscosity plays a vital role in enabling smooth flow in propulsion systems, minimizing clogging or pumping issues. These thermophysical properties are crucial as they allow researchers to design EILs tailored to specific applications, influencing their behavior under different conditions and determining their suitability for specific use. The key thermophysical properties of EILs are summarized below.

Figure 1.

The thermophysical properties of EILs and their importance in applications.

2.6.1. Density

Density plays a crucial role in understanding the relationship between EILs and pressure and temperature. Factors such as temperature, pressure, and chemical compositions help to determine the density of EILs. Different techniques, such as pycnometry, vibrating tube densitometry, and oscillating U-tube densitometry are used to measure the density of the EILs. A higher density indicates a larger mole number in a given volume. Therefore, it provides a higher energy contribution to explosive components. Density is an essential indicator of the energy performance of energetic materials. The density of EILs is controlled by their chemical composition, structure, and surrounding temperature and pressure. For instance, at 25 °C and sea level, the density of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate is 1.248 g/cm3, whereas, that of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium nitrate is 1.295 g/cm3. EILs’ density may change with the change of both temperature and pressure. For instance, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate has a density of 1.241 g/cm3 at 50 °C, which decreases as the temperature increases [4,72].

Pressure also plays an important role in the alteration of density; for instance, the density of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate increases from 1.248 g/cm3 at standard atmospheric pressure to 1.275 g/cm3 under 300 MPa [4].

Strong molecular interaction of a material determines the density of a fluid. Energetic groups like nitroxide (NO2), nitrate (NO3), and cyanide (CN) in the EIL structure enhance detonation performance by increasing hydrogen bonding. Thermal conductivity determines how well a substance transfers heat, and thermal conductivity increases with density because denser EILs have more effective molecular activity for heat transfer [4].

Precise density measurements are mandatory for understanding EIL behavior in various situations. The density impacts other essential properties like viscosity and thermal conductivity of EILs and can change their performance in applications such as heat transfer in fluids and lubricants. Nonetheless, understanding EIL behavior requires understanding the complex interplay between these properties, as density alone cannot fully explain them [72].

2.6.2. Viscosity

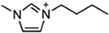

Viscosity is a crucial thermophysical property that significantly influences the performance of EILs in various applications. It defines fluid’s resistance to flow and can be subject to changes in different temperature, pressure, and chemical composition. Techniques such as capillary viscometry, rotational rheometry, and dynamic light scattering are commonly used to measure viscosity by measuring the flow behavior of EILs. The viscosity of EILs can vary widely based on their chemical structure and environmental conditions. For instance, at 25 °C and atmospheric pressure, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide exhibits a viscosity of 74.6 cP, while 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide has a viscosity of 164.4 cP. High viscosities in ILs often arise from extensive hydrogen bond networks, which reduce the mobility of the interaction of the molecules in the liquids. Additionally, electrostatic and van der Waals forces, alongside hydrogen bonding, control the viscosities of EILs [4].

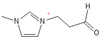

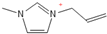

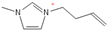

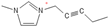

The viscosity of EILs can vary with changes in temperature and pressure. For instance, the viscosity of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethyl sulfonyl) imide decreases to 44.7 cP at 50 °C, demonstrating a reduction as temperature increases. Conversely, pressure has the opposite effect: under 300 MPa, the viscosity of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethyl sulfonyl) imide increases from 164.4 cP at ambient pressure to 227.6 cP. Additionally, incorporating electron-rich anions like N(CN)2 and BH2(CN) with imidazolium-based cations can produce EILs with lower viscosities, such as the hypergolic IL 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanoborate, which has a viscosity of only 12.4 cP at 25 °C. This is significantly higher than traditional hydrazine-based fuels, such as UDMH, which has a viscosity of 0.51 cP at 25 °C. IL-based propellants are closely tied to the discovery of hypergolic ILs with moderate viscosities [4,73].

The viscosity of EILs directly impacts their flow behavior and pumping characteristics. High-viscosity EILs can create pressure drops and reduce flow rates in piping systems and machinery. This could lead to challenges in fuel delivery systems and heat transfer applications where high flow rates are necessary. Higher viscosity EILs increase operational costs and wear on pumps due to more drastic pressure drops [4,73]. Understanding the viscosity of EILs across a range of chemical compositions, temperatures, and pressures is crucial for their effective use in various applications, such as lubricants and heat transfer fluids. However, viscosity is just one of many factors influencing flow behavior and pumping characteristics, necessitating a comprehensive approach to system design for optimal performance [74,75].

2.6.3. Melting Temperature

Melting points (Tm) and decomposition temperatures (Td) of EILs are crucial when seeking to understand their operational temperature range. The accurate measurement of EILs’ melting temperatures can be achieved using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). The melting temperature of EILs can be changed by altering specific anions and cations [73].

EILs show a wide range of melting points, ranging from room temperature to approximately 100 °C. EILs generally have lower melting points than high-melting energetic salts, especially if large, asymmetric ions with shielded or delocalized charges are used. This is because of their lower lattice energies. Unlike traditional ILs, the strong hydrogen-bonding interactions of molecules in EILs often make a closely packed crystal lattice, thus resulting in higher melting points due to the presence of energetic groups such as –NO2, –N3, –CN, and azoles [51].

The design and combination of appropriate cations and anions are crucial to producing room-temperature EILs. Nitrogen-rich heterocycles, which have low symmetry (e.g., imidazolium, triazolium, and tetrazolium) are usually selected as cations because they disrupt crystal lattice packing within the cation [76,77]. For energetic anions, those based on nitrate (NO3−), azide, dicyanamide, and nitrocyanamide have lower melting points. Including fuel-rich functional groups such as allyl and vinyl into the cations can additionally reduce the melting points of EILs. The extent of anion–cation interaction, and the type and strength of these reactions, also play a significant role in determining the melting points of EILs [4].

2.6.4. Glass Transition Temperature

The Tg indicates the change of the material’s glassy-rigid state to a more rubbery and flexible state. Tg can be measured using DSC and TGA. The Tg of an amorphous material is a temperature at which it shifts from glassy, and brittle to a flexible and rubbery state. The EILs that remain liquid at room temperature, such as hypergolic ILs, are selective candidates for use in the propulsion system and show glass transition in heating and cooling cycles. A material’s chemical structure and molecular mobility can manipulate their Tg [78,79].

The dimensions of the cation and anions can contribute to the fluctuation of the Tg of the EILs. Changes in chemical composition and impurities in the material can also change the Tg. Higher molecular mobility generally leads to a lower Tg, which is a key factor in determining the Tg of EILs [4].

Tg is essential when seeking to understand the mechanical and thermal properties of the EILs. EILs that have higher Tg exhibit good thermal stability at high temperatures because of their better resistance to thermal degradation. Furthermore, lower Tg values exhibit more degradation of the materials while exposed to thermal stress, which can cause changes in their chemical composition over time and decrease their efficiency [80]. Mechanical properties of EILs can change due to factors such as chemical composition, molecular mobility, and the impurities present in the liquid. EILs can be used in different applications, such as energy storage devices and solvents. These properties are crucial for understanding the correlation between the Tg and mechanical properties.

The glass transition is regulated by the cohesive energy force in the salt, which is influenced by repulsive Pauli forces from overlapping closed electron shells and attractive Coulomb and van der Waals interactions [81,82]. As EILs cool down, they transition from a supercooled liquid state to an amorphous solid state during the glass transition phase. Van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions control the properties of the glass transition.

Several factors can change the Tg of EILs, including the size, symmetry, hydrogen-bonding interactions, and charge delocalization of the ions. Generally, Tg can be lowered by reducing the size of the cation or increasing its asymmetry. The following Table 1 demonstrates the thermophysical properties of EILS.

Table 1.

Important physicochemical properties of imidazolium-based EILs.

Triazolium-based ILs show excellent thermophysical properties that make them acceptable to various applications. They have strong molecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, which increase their conductivity and high viscosity. Due to the strong molecular interactions their viscosity is very high and decreases with increasing temperature. Because of the hydrogen bonding they show a low melting point. Their degradation temperature is high, which makes them more thermally stable [95,96]. Below, Table 2 presents some thermophysical properties of triazolium-based ILs.

Table 2.

Thermophysical properties of triazolium-based EILs.

3. Discussion

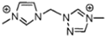

The thermophysical properties of ILs can be significantly controlled by the combination of cations and anions. Here, we are focused mainly on imidazolium and triazolium-based ILs due to their better stability and relatively low viscosity.

Anions play a crucial role in the determination of the hypergolic behavior of the EILs. For instance, EILs that have nitrate or azide anions did not show hypergolic behavior during contact with traditional oxidizers, while EILs containing the same cation with the N(CN)2 anion shows hypergolic behavior. The hypergolic behavior of a material depends on several factors, including the kinetics of reactions with an oxidizer, interfacial properties between the oxidizer and the fuel, processing conditions, etc. [85].

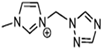

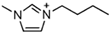

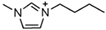

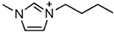

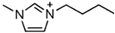

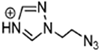

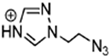

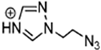

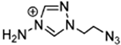

1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium ([bmim])-based EILs, with the combination of nitrogen-containing anions such as nitrate ([NO3]), azide ([N3]), and dicyanamide ([N(CN)2]), have recently gained attention because of their potential as hypergolic substances capable of igniting spontaneously upon contact with an oxidizer [85].

The novel 1-Butyl-3-methyllimidazolium 3,5-dinitro-1,2,4 triazolate EILs (melting point 35 °C) provide a wide range of potentiality to pair with new ILs. 1-Butyl-3-methyllimidazolium 3,5-dinitro-1,2,4 triazolate can be paired with analogous tetramethylammonium, tetraethyl ammonium, and tetrabutylammonium and can improve the thermophysical properties of EILs [83].

1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolim 5-nitrobenzotriazolate and 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolim 5-nitrobenzimidazolate monohydrate show low Tg of −41 °C and −34 °C due to their lower symmetry, diffuse charge distribution, and freezing and melting transitions [87].

Marcin Smiglak [48] and their group undertook DSC experiments on these EILs and found that 1-Hexyl-4-nitroimidazolium picrate and 1-Hexyl-4-nitroimidazolium nitrate show supercooled behavior because of the formation of glass around −33 °C and −63 °C, respectively, and a crystallization transition before melting [89]. 1-methyl-2-nitroimidazolium Picrate, 1-ethyl-2-nitroimadazolium Picrate, 1-ethyl-4-nitroimidazolium Picrate, 1-Butyl-2Methyl-4-nitroimidazolium Picrate, and 1- Pentyl-2Methyl-4-nitroimidazolium Picrate showed wide transition on heating; however, they do not exhibit any crystallization on cooling and heating. DSC results of this group of EILs were found to show a glass transition which is below 0 °C, then, when above room temperature, was found to show a second glass-like transition at the second and third DSC cycles [89].

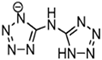

Hydrogen-bonding sites lead to more delocalized electron density around the ring, weakening interactions with the heterocyclic ring and thus lowering the lattice energy, which is related to the lower melting points [42]. EILs based on triazolate anions offer advantages in energetic applications due to improved oxygen balance and nitrogen content. These properties are significant for applications that require lower combustion temperatures, such as gas generators for airbags or fire extinguishing systems.

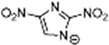

The EILs based on 4-nitro-1,2,3-triazolate exhibit lower Tg than EILs based on 4-nitroimidazolate. They often show higher thermal stabilities than analogous 4-nitroimidazolate salts. The structural difference between 4-nitro-1,2,3-triazo-late and 4-nitroimidazolate involves replacing a carbon atom with a nitrogen atom in 4-nitroimidazolate. This situation increases the number of hydrogen-bond acceptor sites in the anion [87].

Triazolium-based EILs have two carbon groups in their structure, making them more open to be combined with various functional groups. These groups contribute to the release of more heat and energy, allowing broader applications in fields such as high explosives and gas generators. Heterocyclic EILs, characterized by a high density of nitrogen and reduced amounts of hydrogen and carbon in their structure, achieve good oxygen balance. This balance is critical for enhancing energy release during reactions and ensuring a better combustion. A lower hydrogen and carbon content optimizes the oxidizer-to-fuel ratio, maximizing energy output [98].

Table 2 lists triazolium-based EILs paired with a variety of anions, such as 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazolate, 5-nitroimino-tetrazolate, 3-nitro-5-trifluoromethyl-1,2,4-triazolate, 3,5-dinitro-1,2,4-triazolate, 4,5-dinitro-imidazolate, 3,5-dinitro-pyrazolate, and 5-nitro-tetrazolate. These anions combine with triazolium or tetrazolium cations to form novel EILs.

3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol, when combined with a triazolium-based cation, exhibits a high density (1.93 g/cm3), low sensitivity, and a moderate heat of formation (−101.1 kJ/mol). These EILs are composed of densely packed molecules, enabling them to store a substantial amount of energy per unit volume and withstand high temperatures without degradation. Moreover, some of these EILs demonstrate low shock and friction sensitivity, which is crucial for safety in practical applications [99,105].

The anion in EILs plays an important role because it defines the viscosity, density, thermal stability, and thermal conductivity. Furthermore, the selection of anions can also define the toxicity and environmental impact of certain compounds. We can see that the increase of nitrogen atoms in heterocycles increases the standard enthalpy of the formation of the generated energetic compound. The enthalpy properties of those liquids are regulated by the structure of the compound. EILs from Tri-69 to Tri-80 show stability in air and moisture. From observation, the anion also influences the Tg of the EIL. We observed higher melting points of dinitro cyanomethanide-based salts (Tri-75 to Tri-80) when compared with nitro dicyanomethanide-based salts (Tri-69 to Tri 74). A higher melting temperature was observed for 1,4-Dimethyl-5-aminotetrazolium nitrodicyanomethanide (Tri-70) and 1,4-Dimethyl-5-aminotetrazolium dinitro cyanomethanide-based salts. The phase transition temperature alters depending on the combination of the cation and anion pair. Here, we observed that 1,5-Diamino-4-methyltetrazolium dinitro cyanomethanide (Tri-75) has a higher melting temperature, whereas 1,4-Dimethyl-5-aminotetrazolium dinitro cyanomethanide (Tri-76) decomposes before the phase transition temperature. Dinitro cyanomethanide salts (Tri-75 to Tri-80) generally have higher densities when compared with nitro dicyanomethanide (Tri-69 to Tri 74), because of their concentration of nitro groups, the ability of the bond formation of hydrogen bonding also increased. Based on the cations with a constant anion, the density of the salts is 1,5-diamino-4-methyltetrazolium > 1,4-dimethyl-5-aminotetrazolium > 1,4,5-trimethyltetrazolium > 1,4-dimethyltriazolium > 1,3-dimethylimidazolium [102].

High nitrogen tetrazole-based energetic salts have received attention because of their good energetic properties and better thermal stabilities. They contain high nitrogen density in their structure which makes them release more energy and are versatile when bonding with other functional groups. Furthermore, their decomposition releases nitrogen gas which is completely environment friendly [93]. Tetrazole-based EILs have good thermal stability. They remain unchanged under high heat. However, they have only one carbon atom in their structure and cannot combine with other functional parts to change their structure or make them better [98].

4. Conclusions

EILs could be a better alternative to conventional alternatives such as hydrazine and can lead to a better advancement in the field of non-toxic green propellants. Important thermophysical properties of imidazolium and triazolium-based ILs, which are environmentally safer for the space industry, have been discussed in this review.

These ILs show some excellent and important properties, such as good thermal stability, low melting point, and low viscosities. Furthermore, they have low volatility, which makes the ILs more beneficial for better handling, safe storage, and transportation. However, these EILs are still in the progressive stage and need further research in order to synthesize more, achieve a better understanding of them, and craft their properties for industrial and academic applications.

Continued study and development are required to understand their full potential and enhance their wider acceptance in aerospace and other industries. This review paper serves as both a consolidated reference for researchers and a guide for engineers advancing the design and application of EILs across multiple disciplines.

Author Contributions

Conception, summary and evaluation of thermophysical properties, including density, viscosity, and glass transition temperature, and integrated framework N.S.; literature review, framework linking properties and applications and interpretation: A.B. (Aishorjo Bablee); draft manuscript preparation, literature review, compiling tables and data. A.A. provided insightful information on EILs, and J.G.; A.B. (Ariful Bhuiyan) and N.S. reviewed the work as a whole and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), grant number FA9550-22-1-0296.

Acknowledgments

OpenAI’s ChatGPT 3.0 has been used to find the background information, organizing the content and refining language of the manuscript. Furthermore, Elicit has been used for the selection of relevant references. All content obtained by ChatGPT 3.0 was thoroughly evaluated for correctness and relevance to the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nguyen, H.V.N.; Chenoweth, J.A.; Bebarta, V.S.; Albertson, T.E.; Nowadly, C.D. The Toxicity, Pathophysiology, and Treatment of Acute Hydrazine Propellant Exposure: A Systematic Review. Mil. Med. 2021, 186, e319–e326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, U.; Kumbhakarna, N.; Chowdhury, A. Green Hypergolic Ionic Liquids: Future Rocket Propellants. J. Ion. Liq. 2022, 2, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (PDF) Green Propellant: A Study. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290429002_Green_Propellant_A_Study (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Zhang, Q.; Shreeve, J.M. Energetic ionic liquids as explosives and propellant fuels: A new journey of ionic liquid chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10527–10574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosseir, A.E.S.; Cervone, A.; Pasini, A. Review of State-of-the-Art Green Monopropellants: For Propulsion Systems Analysts and Designers. Aerospace 2021, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shreeve, J.M. Ionic Liquid Propellants: Future Fuels for Space Propulsion. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2013, 19, 15446–15451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challenges and Economic Benefits of Green Propellants for Satellite Propulsion | Request PDF. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324219718_Challenges_and_Economic_Benefits_of_Green_Propellants_for_Satellite_Propulsion (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Kamal, F.; Yann, B.; Rachid, B.; Charles, K. Application of Ionic Liquids to Space Propulsion. Appl. Ion. Liq. Sci. Technol. 2011, 447, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, D.; Chehroudi, B. Liquid Propellants and Combustion: Fundamentals and Classifications. Encycl. Aerosp. Eng. 2010, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Dave, P.N. Solid propellants: AP/HTPB composite propellants. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 2061–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S.; Chandramohan, K. A Review on the Development of Various Types of Rocket Propellants. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2021, 10, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombare, B.; Shekhar, S.; Malhotra, V. On the effect of energetic material induction in cryogenic propellants under elevated pressure conditions. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2341, 030014. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, D.L.; Zakrzwski, C.M.; Thomas, M.A. MEMS-based satellitemicropropulsion via catalyzed hydrogen peroxide decomposition. Smart Mater. Struct. 2001, 10, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitrous Oxide as a Green Monopropellant for Small Satellites | Request PDF. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253398401_Nitrous_Oxide_as_a_Green_Monopropellant_for_Small_Satellites (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Freudenmann, D.; Ciezki, H.K. ADN and HAN-Based Monopropellants—A Minireview on Compatibility and Chemical Stability in Aqueous Media. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2019, 44, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, T.W.; Brand, A.J.; McKay, M.B.; Tinnirello, M. Reduced Toxicity, High Performance Monopropellant at the US Air Force Research Laboratory; Air Force Research Laboratory: Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH, USA, 2010; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Negri, M. Replacement of Hydrazine: Overview and First Results of the H2020 Project Rheform. In Proceedings of the 6th European Conference for Aeronautics and Space Sciendes (EUCASS), Kraków, Poland, 29 June–3 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu, R.V.; Aversa, R.; Akash, B.; Bucinell, R.; Corchado, J.; Apicella, A.; Petrescu, F.I. Modern Propulsions for Aerospace-A Review. J. Aircr. Spacecr. Technol. 2017, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac Sam, I.; Gayathri, S.; Santhosh, G.; Cyriac, J.; Reshmi, S. Exploring the possibilities of energetic ionic liquids as non-toxic hypergolic bipropellants in liquid rocket engines. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 350, 118217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.P.; Rovey, J.L. Dual-mode propellant properties and performance analysis of energetic ionic liquids. In Proceedings of the 50th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting Including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, Nashville, TN, USA, 9–12 January 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurilov, M.; Kirchberger, C.; Freudenmann, D.; Stiefel, A.; Ciezki, H. A method for screening and identification of green hypergolic bipropellants. Int. J. Energetic Mater. Chem. Propuls. 2018, 17, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlotti, S.; Maggi, F. Evaluating New Liquid Storable Bipropellants: Safety and Performance Assessments. Aerospace 2022, 9, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remissa, I.; Jabri, H.; Hairch, Y.; Toshtay, K.; Atamanov, M.; Azat, S.; Amrousse, R. Propulsion Systems, Propellants, Green Propulsion Subsystems and their Applications: A Review. Eurasian Chem. -Technol. J. 2023, 25, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, D.; Grinstein, D.; Kuznetsov, A.; Natan, B.; Schlagman, Z.; Habibi, A.; Elyashiv, M. Green Comparable Alternatives of Hydrazines-Based Monopropellant and Bipropellant Rocket Systems. In Aerospace Engineering; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yin, P.; Zhang, J.; Shreeve, J.M. Cyanoborohydride-based ionic liquids as green aerospace bipropellant fuels. Chemistry 2014, 20, 6909–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciezki, H.K. Ionic Liquids in Propulsion Applications. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2019, 44, 1071–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordness, O.; Brennecke, J.F. Ion Dissociation in Ionic Liquids and Ionic Liquid Solutions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12873–12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J.A.P.; Carvalho, P.J.; Oliveira, N.M.C. Predictive methods for the estimation of thermophysical properties of ionic liquids. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 7322–7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiao, E.; Cook, C.; Hu, A.; Murugesu, M. Recent developments in the field of energetic ionic liquids. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2014, 2, 8153–8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Vijayalakshmi, K.P.; George, B.K. Imidazolium based energetic ionic liquids for monopropellant applications: A theoretical study. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 71896–71902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, M.; Lafko, D.; Zwahlen, J.; Costa, W. Development of busek 0.5 N green monopropellant thruster. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites, Logan, UT, USA, 12–15 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt, D.; Brewster, G.; Christofferson, S.; Wucherer, E.J. Development and testing of new, man-based monopropellants in small rocket thrusters. In Proceedings of the 34th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Cleveland, OH, USA, 13–15 July 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovsky, R.S. Han-based monopropellant assessment for spacecraft. In Proceedings of the 32nd Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 1–3 July 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masse, R.; Overly, J.; Allen, M.; Spores, R. A new state-of-the-art in AF-M315E thruster technologies. In Proceedings of the 48th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Atlanta, GA, USA, 30 July–1 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dambach, E.M.; Cho, K.Y.; Pourpoint, T.L.; Heister, S.D. Ignition of Advanced Hypergolic Propellants. In Proceedings of the 46th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Nashville, TN, USA, 25–28 July 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.M.; Yilmaz, N. Advances in Hypergolic Propellants: Ignition, Hydrazine, and Hydrogen Peroxide Research. Adv. Aerosp. Eng. 2014, 2014, 729313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arestie, S.; Lightsey, E.G.; Hudson, B. Development of a modular, cold gas propulsion system for small satellite applications. J. Small Satell. 2012, 1, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Anis, A. Cold Gas Propulsion System—An Ideal Choice for Remote Sensing Small Satellites. In Remote Sensing—Advanced Techniques and Platforms; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wucherer, E.J.; Christofferson, S.S.; Reed, B. Assessment of high performance HAN-monopropellants. In Proceedings of the 36th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Las Vagas, NV, USA, 24–28 July 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, R.; Oommen, C. Cerium oxide based active catalyst for hydroxylammonium nitrate (HAN) fueled monopropellant thrusters. RSC Adv 2018, 8, 22293–22302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnamperuma, C.; Lemmon, R.M.; Mariner, R.; Calvin, M. Formation of adenine by electron irradiation of methane, AMMONIA, and water. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1963, 49, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamachi, M.Y.; Oliveira, J.I.S.; Kawamoto, A.M.; Dutra, R.d.C.L. ADN—The new oxidizer around the corner for an environmentally friendly smokeless propellant. J. Aerosp. Technol. Manag. 2009, 1, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingborg, N.; Larsson, A.; Elfsberg, M.; Appelgren, P. Characterization and Ignition of ADN-Based Liquid Monopropellants. In Proceedings of the 41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Tucson, AZ, USA, 10–13 July 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.; Negri, M.; Ciezki, H.; Schlechtriem, S. Preliminary tests on thermal ignition of ADN-based liquid monopropellants. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 158, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, W.; Bhosale, V.K.; Yoon, H. Performance Evaluation of Ammonium Dinitramide-Based Monopropellant in a 1N Thruster. Aerospace 2024, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yu, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, J. Experimental Research on Microwave Ignition and Combustion Characteristics of ADN-Based Liquid Propellant. Micromachines 2022, 13, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiglak, M.; Pringle, J.M.; Lu, X.; Han, L.; Zhang, S.; Gao, H.; Macfarlane, D.R.; Rogers, R.D. Ionic liquids for energy, materials, and medicine. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 9228–9250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiglak, M.; Metlen, A.; Rogers, R.D. The second evolution of ionic liquids: From solvents and separations to advanced materials--energetic examples from the ionic liquid cookbook. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G. Functionalized imidazolium salts for task-specific ionic liquids and their applications. Chem. Commun. 2006, 10, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriyko, Y.O.; Reischl, W.; Nauer, G.E. Trialkyl-Substituted Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids for Electrochemical Applications: Basic Physicochemical Properties. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2009, 54, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.B.; Haiges, R.; Schroer, T.; Christe, K.O. Oxygen-balanced energetic ionic liquid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2006, 45, 4981–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackheim, R.L.; Masse, R.K. Green Propulsion Advancement: Challenging the Maturity of Monopropellant Hydrazine. J. Propuls. Power 2014, 30, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumi, T.; Hori, K. Successful development of HAN based green propellant. Energetic Mater. Front. 2021, 2, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woschnak, A.; Krejci, D.; Schiebl, M.; Scharlemann, C. Development of a green bipropellant hydrogen peroxide thruster for attitude control on satellites. Prog. Propuls. Phys. 2013, 4, 689–706. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza, A. Thermoanalytical Studies on the Decomposition Of Energetic Ionic Liquids. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.; Lee, B.; Song, M.; Jang, S.; Kwon, K.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.G. Novel 4,5-Dinitro-N,N′-dialkylimidazolium Cations as Candidates for High-energy Materials. Bull Korean Chem Soc 2021, 42, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Kumar, H.; Singla, M. Diverse applications of ionic liquids: A comprehensive review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 351, 118556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, R.; Thakur, R.C.; Singh, L. An overview of deep eutectic solvents: Alternative for organic electrolytes, aqueous systems & ionic liquids for electrochemical energy storage. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 82, 592–626. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, M.; Thomas, M.L.; Zhang, S.; Ueno, K.; Yasuda, T.; Dokko, K. Application of Ionic Liquids to Energy Storage and Conversion Materials and Devices. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7190–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Gui, C.; Sun, L.; Hu, Y.; Lyu, H.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; Yu, G. Energy Applications of Ionic Liquids: Recent Developments and Future Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 12170–12253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Xin, J.; Miao, Q.; Wang, J. Ionic liquid-based green processes for energy production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7838–7869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gao, H.; Shreeve, J.N.M. Borohydride Ionic Liquids and Borane/Ionic-Liquid Solutions as Hypergolic Fuels with Superior Low Ignition-Delay Times. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2969–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, D.; Zhang, J.; Shreeve, J.M. Borohydride Ionic Liquids as Hypergolic Fuels: A Quest for Improved Stability. Chemistry 2015, 21, 13297–13301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöyer, H.F.R.; Schnorhk, A.J.; Korting, P.A.O.G.; Van Lit, P.J.; Mul, J.M.; Gadiot, G.M.H.J.L.; Meulenbrugge, J.J. High-performance propellants based on hydrazinium nitroformate. J. Propuls. Power 1995, 11, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, M.; Stoops, D.R.; Rudy, T.P.; Hermsen, R.W. Optimization of Spark and ESD Propellant Sensitivity Tests. A review. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 1990, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, U.; Senapathi, K.; Srinivasulu, K.M.; Desingu, J.; Chowdhury, A. Energetic ionic liquid hydroxyethylhydrazinium nitrate as an alternative monopropellant. Combust. Flame 2020, 215, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Huang, S.; Wang, K.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Q. Synthesis and Properties of Triaminocyclopropenium Cation Based Ionic Liquids as Hypergolic Fluids. Chem. A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 4620–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q. Novel applications of ionic Liquids in molecular crystallization. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kianfar, E.; Mafi, S. Ionic liquids: Properties, application, and synthesis. Fine Chem. Eng. 2020, 2, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, G.; Dhariwal, J.; Saha, M.; Trivedi, S.; Banjare, M.K.; Kanaoujiya, R.; Behera, K. Ionic liquids: Environmentally sustainable materials for energy conversion and storage applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 10296–10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, K.S.; Chia, W.Y.; Wang, K.; Chang, C.K.; Leong, H.Y.; Maaris, M.N.B.; Show, P.L. Development of proton-exchange membrane fuel cell with ionic liquid technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paduszyński, K. Extensive Databases and Group Contribution QSPRs of Ionic Liquid Properties. 3: Surface Tension. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 5705–5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Huang, J.F.; Dai, S. Studies on thermal properties of selected aprotic and protic ionic liquids. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 2473–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S. Insight into the Relationship between Viscosity and Hydrogen Bond of a Series of Imidazolium Ionic Liquids: A Molecular Dynamics and Density Functional Theory Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 18848–18854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, M.C.M.; Avelino, H.M.N.T.; Caetano, F.J.P.; Fareleira, J.M.N.A. Viscosity measurements of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate (EMIM OTf) at high pressures using the vibrating wire technique. Fluid Phase Equilib 2020, 505, 112354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drab, D.M.; Shamshina, J.L.; Smiglak, M.; Hines, C.C.; Cordes, D.B.; Rogers, R.D. A general design platform for ionic liquid ions based on bridged multi-heterocycles with flexible symmetry and charge. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3544–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Hussey, C.L. Electrochemical applications of room-temperature ionic liquids. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2007, 16, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, M.Y.; Prikhod’ko, S.A.; Adonin, N.Y.; Kirilyuk, I.A.; Adichtchev, S.V.; Surovtsev, N.V.; Dzuba, S.A.; Fedin, M.V. Structural Anomalies in Ionic Liquids near the Glass Transition Revealed by Pulse EPR. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 4607–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocharova, V.; Wojnarowska, Z.; Cao, P.F.; Fu, Y.; Kumar, R.; Li, B.; Novikov, V.N.; Zhao, S.; Kisliuk, A.; Saito, T.; et al. Influence of Chain Rigidity and Dielectric Constant on the Glass Transition Temperature in Polymerized Ionic Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 11511–11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranyai, K.J.; Deacon, G.B.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Pringle, J.M.; Scott, J.L. Thermal degradation of ionic liquids at elevated temperatures. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cooper, E.I.; Angell, C.A. Ionic liquids: Ion mobilities, glass temperatures, and fragilities. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 6170–6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.; Panyoyai, N.; Shanks, R.; Kasapis, S. Effect of sodium chloride on the glass transition of condensed starch systems. Food Chem. 2015, 184, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritzky, A.R.; Singh, S.; Kirichenko, K.; Holbrey, J.D.; Smiglak, M.; Reichert, W.M.; Rogers, R.D. 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium 3,5-dinitro-1,2,4-triazolate: A novel ionic liquid containing a rigid, planar energetic anion. Chem. Commun. 2005, 7, 868–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiglak, M.; Reichert, W.M.; Holbrey, J.D.; Wilkes, J.S.; Sun, L.; Thrasher, J.S.; Kirichenko, K.; Singh, S.; Katritzky, A.R.; Rogers, R.D. Combustible ionic liquids by design: Is laboratory safety another ionic liquid myth? Chem. Commun. 2006, 24, 2554–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedrov, D.; Borodin, O. Thermodynamic, dynamic, and structural properties of ionic liquids comprised of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium cation and nitrate, azide, or dicyanamide anions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 12802–12810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Hawkins, T.; Rosander, M.; Mills, J.; Vaghjiani, G.; Chambreau, S. Liquid azide salts and their reactions with common oxidizers IRFNA and N2O4. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 6082–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiglak, M.; Hines, C.C.; Wilson, T.B.; Singh, S.; Vincek, A.S.; Kirichenko, K.; Katritzky, A.R.; Rogers, R.D. Ionic liquids based on azolate anions. Chemistry 2010, 16, 1572–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritzky, A.R.; Yang, H.; Zhang, D.; Kirichenko, K.; Smiglak, M.; Holbrey, J.D.; Reichert, W.M.; Rogers, R.D. Strategies toward the design of energetic ionic liquids: Nitro- and nitrile-substituted N,N′-dialkylimidazolium salts. New J. Chem. 2006, 30, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiglak, M.; Hines, C.C.; Reichert, W.M.; Vincek, A.S.; Katritzky, A.R.; Thrasher, J.S.; Sun, L.; McCrary, P.D.; Beasley, P.A.; Kelley, S.P.; et al. Synthesis, limitations, and thermal properties of energetically-substituted, protonated imidazolium picrate and nitrate salts and further comparison with their methylated analogs. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 702–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gao, H.; Ye, C.; Shreeve, J.M. Strategies toward syntheses of triazolyl- Or triazolium-functionalized unsymmetrical energetic salts. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Tao, G.-H.; Parrish, D.A.; Shreeve, J.M. Liquid dinitromethanide salts. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.H.; Tang, M.; He, L.; Ji, S.P.; Nie, F.D.; Huang, M. Synthesis, Structure and Property of 5-Aminotetrazolate Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 3070–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Xiao, H. Structure–property relationships of energetic nitrogen-rich salts composed of triaminoguanidinium or ammonium cation and tetrazole-based anions. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2013, 40, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiglak, M.; Hines, C.C.; Reichert, W.M.; Shamshina, J.L.; Beasley, P.A.; McCrary, P.D.; Kelley, S.P.; Rogers, R.D. Azolium azolates from reactions of neutral azoles with 1,3-dimethyl-imidazolium-2-carboxylate, 1,2,3-trimethyl-imidazolium hydrogen carbonate, and N,N-dimethyl-pyrrolidinium hydrogen carbonate. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, C.; Maginn, E.J. Molecular simulation study of some thermophysical and transport properties of triazolium-based ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 18026–18039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Hoz, A.T.; Brauer, U.G.; Miller, K.M. Physicochemical and thermal properties for a series of 1-alkyl-4-methyl-1,2,4-triazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 9944–9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Arritt, S.W.; Twamley, B.; Shreeve, J.M. Energetic salts from N-aminoazoles. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 7972–7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwich, C.; Klapötke, T.M.; Sabaté, C.M. 1,2,4-triazolium-cation-based energetic salts. Chemistry 2008, 14, 5756–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Gao, Y.; Twamley, B.; Shreeve, J.M. Energetic azolium azolate salts. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 5068–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Shreeve, J.M. Energetic Ionic Liquids from Azido Derivatives of 1,2,4-Triazole. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 2142–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Gao, H.; Twamley, B.; Shreeve, J.M. Energetic salts of 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazole-5-one, 5-nitroaminotetrazole, and other nitro-substituted azoles. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gao, H.; Ye, C.; Twamley, B.; Shreeve, J.M. Heterocyclic-based nitrodicyanomethanide and dinitrocyanomethanide salts: A family of new energetic ionic liquids. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gao, H.; Piekarski, C.; Shreeve, J.M. Azolium Salts Functionalized with Cyanomethyl, Vinyl, or Propargyl Substituents and Dicyanamide, Dinitramide, Perchlorate and Nitrate Anions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 2007, 4965–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierstorfer, J.; Klapötke, T.M. High Energy Materials. Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics. By Jai Prakash Agrawal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Verma, R.D.; Meshri, D.T.; Shreeve, J.M. Energetic nitrogen-rich salts and ionic liquids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2006, 45, 3584–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).