Abstract

This study analyzes the evolution of Pakistan’s energy policies from 1990 to 2024, documenting their transition from a singular focus on generation capacity to an integrated approach prioritizing renewable energy and efficiency. Through a systematic literature review of 110 initially screened studies, with 50 meeting the inclusion criteria and 22 selected for in-depth analysis, we evaluated policy effectiveness and identified implementation barriers. Our methodology employed predefined criteria focusing on energy efficiency, environmental sustainability, and climate impact, utilizing the Web of Science and Scopus databases. Early policies like the National Energy Conservation Policy (1992) and the Energy Policy (1994) emphasized energy security through generation capacity expansion while largely neglecting renewable sources and efficiency improvements. The policy landscape evolved in the 2000s with the introduction of renewable energy incentives and efficiency initiatives. However, persistent challenges include short-term planning, inconsistent implementation, and fossil fuels dependence. Recent framework like the Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy (2019) and the National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Plan (2020–2025) demonstrate progress toward sustainable energy practices. However, institutional, financial, and regulatory barriers continue to constrain effectiveness. We recommend that Pakistan’s energy strategy prioritize the following: (1) long-term planning horizon; (2) enhanced fiscal incentives; and (3) strengthened institutional support to meet global energy security and climate resilience standards. These measures would advance Pakistan’s sustainable energy transition while supporting both energy security and environmental objectives.

1. Introduction

Global energy demand has risen steadily in recent decades, creating significant pressure on energy security while exacerbating climate change [1]. Energy efficiency improvements have emerged as a critical strategy to address these dual challenges, simultaneously curbing growing energy demand and reducing global CO2 emissions [2,3]. The International Energy Agency [4] estimates that strategic energy efficiency measures could contribute over one-third of the total greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions required for climate stabilization. Furthermore, enhancing energy efficiency can both alleviate household financial burdens and reduce emissions [5].

Despite these benefits, energy policies in developed countries (including the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia) have demonstrated inconsistent approaches to climate change and energy security. This inconsistency stems from inadequate long-term planning, ambiguous objectives, and insufficient guidance on optimal energy efficiency intervention [6,7,8]. Such policy shortcomings have contributed to rising GHG emissions across both developed and emerging economies [9]. Consequently, energy efficiency has gained recognition as a cost-effective solution for addressing energy security and emissions reduction [10], establishing it as a vital research priority for climate-conscious policymakers.

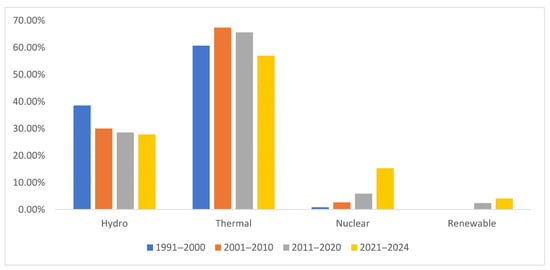

Pakistan’s energy policy evolution reflects these global challenges. The initial 1990s policies prioritized generation capacity expansion while largely overlooking renewable energy and efficiency measures. As the energy crisis intensified, 2000s frameworks gradually incorporated alternative energy sources with greater environmental consideration. However, implementation has been hampered by bureaucratic inefficiencies, limited financing, and inconsistent enforcement. Recently, initiatives like the Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy of 2019 and the National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Plan (2020–2025) represent more comprehensive approaches integrating renewable energy efficiency and environmental concerns. Despite these advances, renewable energy’s share in the national energy mix remains modest (Figure 1), while persistent implementation challenges continue to constrain policy effectiveness.

Figure 1.

Pakistan’s primary energy supply by source (source: Pakistan Economy Dashboard).

Improving energy efficiency is essential to enhancing environmental sustainability and reducing Pakistan’s energy demand. Empirical research demonstrates that energy efficiency measures can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, thereby supporting global climate change mitigation efforts [11]. These improvements offer multiple additional benefits: they relieve pressure on national energy infrastructure, decrease dependence on fossil fuels, strengthen energy security, promote sustainable development, and ensure a cleaner environment for future generations [12]. Furthermore, such measures conserve valuable resources while reducing the financial burden of energy imports [13].

Over recent decades, Pakistan’s government has implemented numerous policies to address persistent energy security challenges. However, these initiatives have frequently proven ineffective due to fundamental design flaws, inconsistent implementation, and inadequate measurement of outcomes. This study systematically examines the evolution of government policies and regulatory frameworks designed to promote energy efficiency in Pakistan.

This analysis highlights Pakistan’s historical energy challenges, primarily focusing on increasing generation capacity at the expense of energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. As the country transitioned toward renewable energy and more sustainable practices, it faced significant barriers, including economic constraints, institutional limitations, and inconsistent regulatory enforcement. This study assesses key policy indicators to determine whether specific targets have been achieved.

This research identifies uncertainties within policy frameworks and evaluates how shifting priorities—from energy generation to renewable energy and conservation—have shaped policy outcomes. Ultimately, it seeks to offer insights into the ongoing evolution of these policies, assessing their influence on energy efficiency initiatives and subsequent actions. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of how energy policies have shaped Pakistan’s current energy landscape and highlights the actions needed to ensure sustainable energy security.

1.1. Research Gap and Novelty of the Study

This study examines Pakistan’s energy policies from 1990 to 2024, a period that encapsulates critical shifts in the country’s energy strategy. The early 1990s marked the first formal energy conservation initiatives, such as the National Energy Conservation Policy (1992), while the 2000s introduced renewable energy incentives. The post-2010 era saw policies grappling with the energy crisis and sustainability, culminating in recent frameworks like the Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy of 2019 and the National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Plan (2020–2025). This timeframe allows for a comprehensive assessment of policy evolution, from supply-side fixes to integrated approaches balancing energy security, efficiency, and environmental sustainability.

While the existing literature has examined Pakistan’s energy policies in isolation or focused on specific sectors, this research offers a longitudinal analysis spanning three decades (1990–2024). It systematically evaluates policy shifts, implementation barriers, and alignment with global sustainability standards. By employing a structured comparative framework, the study identifies persistent institutional and fiscal challenges, factors often overlooked in earlier research. This approach provides actionable insights for policymakers seeking to reconcile energy security with climate commitments.

First, this study provides a holistic review of Pakistan’s energy policy evolution across four distinct phases, using a systematic literature review framework to ensure methodological rigor. Second, identifying persistent implementation challenges—such as institutional inefficiencies, short-term planning, and fiscal constraints—that have hindered policy effectiveness despite progressive shifts towards renewables and efficiency. Third, it offers comparative insights into how Pakistan’s policies align (or diverge) with international best practices, particularly in balancing energy security, economic feasibility, and environmental sustainability.

By addressing these gaps, this study contributes to both academic discourse and policymaking by highlighting actionable strategies to enhance Pakistan’s energy transition. The findings are particularly relevant for developing economies facing similar challenges in reconciling energy security with climate commitments.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the methodology, including the systematic literature review framework and policy evaluation criteria. Section 3 analyzes the evolution of Pakistan’s energy efficiency policies across four distinct phases (1990–2024). Section 4 compares these policies, identifying key challenges and inconsistencies. Finally, Section 5 concludes with policy recommendations aimed at fostering sustainable energy security.

1.2. Background of Energy Efficiency in Pakistan

For decades, the Pakistani government has overlooked energy efficiency and conservation as key strategies, prioritizing increased energy supply over demand reduction. According to the World Bank’s Regulatory Indicators for Sustainable Energy Efficiency (RISE), Pakistan scores only 28 out of 100, highlighting significant gaps in policies, regulations, and financing mechanisms that lag behind its global standards.

To address its energy challenges, Pakistan has partnered with foreign organizations to build new power plants, upgrade transmission and distribution networks, and attract foreign investment to expand production capacity [14]. However, resolving the energy crisis requires sustained efforts, long-term planning, and comprehensive policy reforms. Institutional energy efficiency and conservation efforts remain inadequate, with no dedicated federal authority to implement programs across all sectors [15]. Key barriers include high upfront costs, inconsistent policies, lack of incentives, and limited public engagement [16].

In the 21st century, environmental scientists and policymakers have increasingly recognized energy efficiency and conservation as critical tools for reducing emissions and combating climate change [17]. For Pakistan, adopting these measures across all sectors represents the most cost-effective path to achieving climate goals while minimizing economic burdens. Despite current challenges, Pakistan’s energy sectors hold substantial untapped potential for energy efficiency, offering an economically viable solution to simultaneously address the energy crisis and climate change.

2. Methodology

2.1. Systematic Review

This study employed a systematic literature review following the methodology of Wallace et al. [18] to examine Pakistan’s energy policies. We conducted comprehensive searches across Scopus and Web of Science databases using keywords “Energy Policies Pakistan,” “Energy Efficiency and Energy Security,” and “Environmental Impact.” Our selection process applied three strict inclusion criteria: publications must be in English, focus specifically on Pakistan’s energy policy, and have been published in the year 2000 or later.

The initial search yielded 110 potentially relevant articles. Through a rigorous multi-stage screening process, we first narrowed these down to 70 studies by selecting only English-language publications from 2000 onward that focused on Pakistan’s energy sector. Applying our inclusion criteria more stringently reduced this to 50 studies. Finally, we implemented a quality assessment threshold based on Wallace et al. [18], which resulted in the selection of 22 high-quality studies that met all methodological standards.

This systematic approach ensured that the selected literature maintained methodological rigor while being highly relevant to Pakistan’s unique energy policy landscape. The careful screening process guaranteed that all included studies aligned perfectly with our research objectives and provided reliable, focused insights into Pakistan’s energy policy evolution. The systematic literature review is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Systematic literature review.

2.2. Searching the Literature

This review incorporated studies that specifically addressed energy efficiency and conservation concerning climate change. Selection prioritized research relevant to Pakistan’s energy policy landscape, particularly works examining energy efficiency/conservation policies, sustainable environments, and climate change implications. Energy efficiency has been globally recognized as a cost-effective strategy for reducing emissions and energy demand while supporting economic resilience and environmental objectives [5]. Existing research demonstrates that enhanced energy efficiency could alleviate Pakistan’s fossil fuel dependence, decrease energy expenditures, and boost industrial competitiveness [36,40]. The urgency of environmental sustainability is magnified by Pakistan’s acute vulnerabilities to climate risks, including water scarcity and extreme weather events, which underscores the necessity for policies promoting long-term ecological stability [30,41]. This focus aligns with Pakistan’s Paris Agreement commitments to emission reduction and sustainable energy transition [42,43]. These selection criteria enable systematic evaluation of policy integration with critical parameters, revealing their efficacy in emissions and sustainable development support.

Section 3 and Section 4 employ a systematic, multi-dimensional approach to assess Pakistan’s energy policy evolution from 1990 to 2024. The analysis adapts Howlett and Cashore [44] policy evolution model through a phased framework that divides the policy landscape into four distinct phases, each marked by unique policy priorities, technological contexts, and environmental considerations. This comprehensive approach evaluates seven key parameters: energy security, electricity generation, renewable energy integration, energy efficiency, environmental sustainability, fiscal incentives, and institutional feasibility. As detailed in Table 2, the structured comparative methodology captures nuanced policy shifts across different eras, revealing how domestic needs, technological progress, and global sustainability trends have shaped Pakistan’s energy policy trajectory. The phased framework serves as an analytical tool to critically examine policy achievements, shortcomings, and strategic transitions in national energy management approaches.

Table 2.

Policy comparison framework.

2.3. Assessment of Validity

This study systematically examines Pakistan’s Energy policies from 1990 to 2024, focusing specifically on energy efficiency/conservation, environmental sustainability, and climate impact. The analysis employs Howlett and Cashore’s policy evolution framework [44], adapted to account for Pakistan’s distinctive institutional and socioeconomic context. This framework proves particularly appropriate for Pakistan’s energy sector, as it accommodates both incremental policy adjustment (“layering”) and fundamental objectives shifts (“drift”)—features that characterize the country’s irregular reform trajectory.

This analysis divides the study period into four phases (I: 1990–2002; II: 2002–2013; III: 2013–2019; IV: 2019–2024). Phased demarcation followed three key criteria: (1) major policy milestones (e.g., the 2006 Renewable Energy policy making Phase II’s commencement); (2) evolving priority shifts (from energy security to sustainability); and (3) external catalysts, including global climate commitments and domestic energy crises. This phased approach builds on existing empirical research into Pakistan’s energy challenges [36,45], while the framework’s institutional focus helps explain persistent implementation shortcomings like bureaucratic inefficiencies and myopic planning.

The systematic literature review (summarized in Table 1) documents each selected study’s primary focus, methodology, and key findings, providing an organized synthesis of Pakistan’s energy policy research. Our analytical approach employed structured thematic categorization, prioritizing studies that addressed three core dimensions: (1) energy efficiency/conservation policy measures; (2) environmental impact assessments; and (3) CO2 emission trend analysis in Pakistan’s energy sector.

This approach allowed for a comprehensive examination of policy developments, tracking while capturing critical sustainability objectives and climate mitigation strategies. By organizing the literature around these thematic pillars, this study achieves a nuanced understanding of Pakistan’s policy response to sustainability challenges. The methodological approach enables a systematic evaluation of policy evolution, particularly the interrelationship between energy efficiency improvements, environmental sustainability goals, and climate resilience building within Pakistan’s national energy management paradigm.

3. Energy Efficiency Policy Regimes from 1990 to 2024

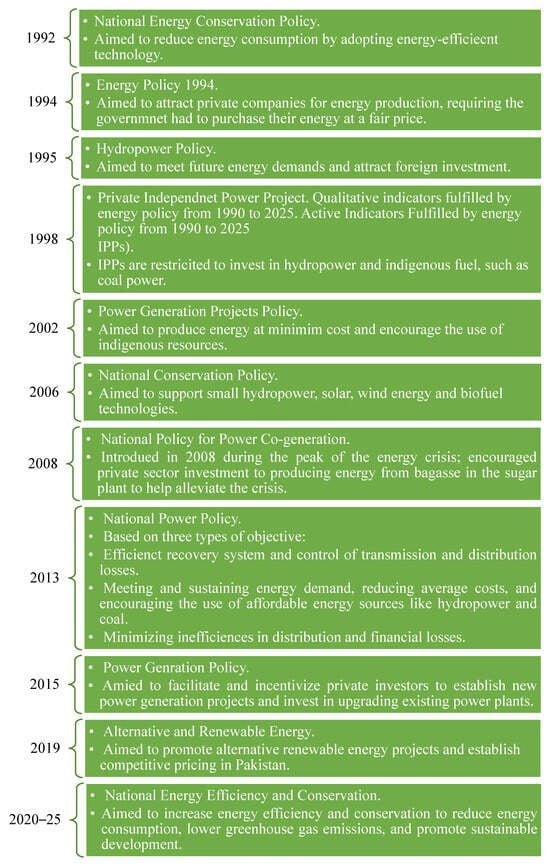

This study analysis Pakistan’s energy policy evolution through four distinct phases (1990–2002, 2002–2013, 2013–2019, 2019–2024), delineated by three critical criteria: (1) major police milestones (e.g., the 2006 Renewable Energy Policy marking Phase II); (2) shifts in dominant priorities (from energy security to sustainability); and (3) structural transformations in energy governance. This periodization framework aligns with Pakistan’s political–economic transitions and global energy trends, facilitating systematic policy comparison. The overview of the Pakistan energy policy is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Pakistan energy policies overview.

The National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority [46] identifies energy efficiency improvement as s cost-effective strategy to address Pakistan’s rising energy demand while reducing CO2 emissions. The early 2000s witnessed rapid urbanization and industrial growth that precipitated sharp increases in both energy consumption and emissions. The World Bank emphasizes that all nations must strengthen energy efficiency measures, highlighting their dual role in sustainable development and the necessity of government leadership in prioritizing such initiatives.

Our analytical framework systematically examines five key parameters across each phase: primary policy objective, implementation mechanisms, institutional configurations, external influences, and measurable outcomes. Adapted from Howlett and Cashore’s policy dynamics model [44], this approach incorporates energy-specific metrics tailored to Pakistan’s context. Phase transition reflects fundamental shifts in these parameters rather than mere chronological progression, particularly when new policy instruments coincide with institutional restructuring or respond to critical energy crises. For example, the Phase I–II transition (2002) marked both renewable energy incentives and new regulatory bodies, while Phase III simultaneously featured emergency generation measures and emerging efficiency standards. The multidimensional analysis reveals substantive differentiation between periods with nominally similar sustainability goals but varying implementation rigor and outcomes.

However, effective energy efficiency promotion requires a comprehensive national policy supported by innovative institutional and fiscal mechanisms [47]. NEECA identifies three key adoption barriers: economic constraints, institutional and governance challenges, and information gaps. Overcoming these obstacles demands well-designed regulations, robust policy measures, and effective enforcement mechanisms. Our analysis of Pakistan’s policy evolution specifically evaluates the potential impact of large-scale energy-efficient technology deployment, assessing how successive policy regimes have addressed these implementation challenges while balancing energy security and sustainability objectives.

3.1. Policy Evaluation

Pakistan’s energy policies have historically prioritized increasing energy generation capacity to meet growing demand [48]. This approach contrasts with the global shift toward climate change-conscious policymaking that increasingly emphasizes energy efficiency measures [49]. Contemporary economic policies worldwide now recognize energy efficiency as a driver of prosperity, simultaneously reducing greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption [50,51]. Enhanced efficiency regulations not only conserve resources but also yield significant economic benefits, including reduced energy cost and positive environmental externalities [36]. Energy conservation has consequently emerged as a critical strategy for addressing climate change, advancing sustainable development, and strengthening energy security.

Pakistan’s energy policy evolution can be analyzed through four distinct phases that reflect changing domestic priorities and global influences [28]. The initial phase during the 1990s responded to fossil fuel scarcity by emphasized conservation, most notably through the National Energy Conservation Policy of 1992. Malik et al. [28] highlight ENERCON’s pivotal role during this period in promoting energy-efficient technologies and establishing foundational conservation measures.

The second phase emerged in the 2000s with a renewed focus on cost-effective solutions and domestic resources utilization. This strategic shift became evident through landmark policies like the Renewable Energy Policy of 2006, which sought to diversify energy sources and decrease reliance on imported fossil fuels [45]. The post-2010 period marked the third phase, characterized by efforts to resolve persistent energy shortages while integrating renewable energy sources. Key initiatives during this stage included the National Power Policy in 2013 and the Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy in 2019, which aimed to simultaneously expand generation capacity and promote sustainability practices [29].

The current fourth phase represents Pakistan’s most progressive approach, prioritizing energy efficiency and climate change mitigation through policies like the National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Plan (2020–2025). These measures align with international sustainability commitments while delivering tangible economic benefits through efficiency improvements [36]. This four-phase framework corresponds with Howlett and Cashore policy evolution model [44], demonstrating how changing societal, economic, and environmental priorities have progressively reshaped Pakistan’s energy sector. The model provides a valuable analytical tool for assessing both achievement and ongoing challenges in the country’s energy policy development.

3.1.1. Phase I: Foundational Conservation Policy (1990–2002)

The inaugural phase (1990–2002) marked Pakistan’s first structured attempt at energy governance, characterized by three defining features that ultimately limited its effectiveness despite its pioneering status: first, conservation objectives were narrowly framed, focusing exclusively on industrial efficiency; second, implementation relied on voluntary audits rather than regulatory mandates; third, while the creation of the Energy Conservation Center (ENERCON) represented institutional innovation, the organization lacked substantive enforcement powers. These constrained parameters, when analyzed through our policy evolution framework, explain the phase’s limited impact on Pakistan’s broader energy landscape.

The early 1990s presented significant energy sector challenges, mounting inefficiencies and a growing gap between energy demand and supply. The government respondent with policy initiatives to address the energy crisis and improve utilization across sectors. ENERCON, established in 1986 but becoming operational in the early 1990s, emerging as a central institution in these efforts. The 1992 National Energy Conservation Policy (NECP) represented a landmark initiative, aiming to reduce consumption through the promotion of energy-efficient technologies and practices in key sectors including industry, transport, and agriculture. The policy introduced measures such as energy audits, equipment retrofitting, and incentives for efficient appliances, yielding measurable energy savings and raising awareness in targeted industries. ENERCON’s audit program, for instance, enabled industrial facilities to implement energy-saving measures that reduced both cost and consumption.

Concurrently, the 1994 and 1998 energy policies pursed complementary objectives focused on thermal energy expansion and private sector participation. These frameworks offered tax and duty incentives to independent power producers (IPPs), with minimal environmental regulations, to rapidly increase generation capacity. While successful in attracting private investment and expanding supply, these policies priorities immediate production increases over efficiency improvements or environmental considerations.

Several systemic constraints undermined the phase’s potential impact. Implementation suffered from bureaucratic inefficiencies and poor interagency coordination, while the absence of robust financial incentives limited adoption of energy-efficient technologies among businesses and households. Technical challenges included inadequate infrastructure and expertise, with many industries lacking access to modern technologies or qualified professionals to facilitate implementation. Consequently, while generation capacity increased, the phase achieved minimal progress on environmental sustainability or long-term economic efficiency, reflecting the prevailing prioritization of crisis response over comprehensive energy sector reform.

3.1.2. Phase II: Renewable Energy Transition (2002–2013)

The 2002–2013 period marked Pakistan’s concerted shift toward renewable energy adoption, through the transition revealed significant policy implementation challenges. This phase began with the 2002 Energy policy that prioritized affordable energy generation through domestic resources while granting independent power producers (IPPs) problematic flexibility in fuel selection. The policy’s allowance for imported fossil fuel, while initially boosting generation capacity, ultimately contributed to supply chain vulnerabilities that exacerbated Pakistan’s energy crisis in subsequent years.

The year 2006 marked a significant turning point in Pakistan’s energy policy with the introduction of two landmark initiatives that demonstrated conceptual progress in energy planning. These policies showed measurable advancement across key analytical parameters: they expanded policy objectives to include fuel diversification, introduced tax incentives for private investors, and established renewable energy task forces as institutional mechanisms. However, analysis reveals that inconsistent implementation of these tools, particularly the continued provision of fossil fuel subsidies, created fundamental policy incoherence that ultimately undermined sustainability goals.

ENERCON and the Ministry of Environment jointly introduced the National Energy Conservation Policy 2006, which represented a substantial evolution from previous approaches. This comprehensive framework focused on promoting renewable energy while improving end-use efficiency across all consumption sectors. It introduced numerous sector-specific conservation measures and, for the first time, emphasized the development of alternative energy projects, including small hydropower plants, solar arrays, wind farms, and biofuel sources. The policy ambitiously sought to create an energy conservation market that would raise public awareness and improve efficiency among diverse consumer groups, thereby enhancing environmental quality.

Simultaneously, the government released the Policy for Development of Renewable Energy for Power Generation in 2006, which established three clear objectives: first, to accelerate development of renewable energy technologies; second, to supplement energy supply for growing demand; and third, to create financial incentives to attract investment in renewable energy markets. Together, these policies represented Pakistan’s most progressive energy planning effort to date.

Despite these advances, the 2006 National Energy Conservation Policy faced significant implementation challenges that limited its effectiveness. A primary constraint was the lack of regulatory authority to enforce efficiency measures, leaving compliance largely voluntary. The policy framework also suffered from inadequate implementation and monitoring mechanisms, resulting in inconsistent application across sectors. Furthermore, it failed to adequately address the economic barriers to adoption, particularly high upfront costs and limited financing options for energy-efficient technologies, which substantially constrained its potential impact on national energy consumption patterns and efficiency improvements.

3.1.3. Phase III: National Power Policy

The post-2010 period saw Pakistan confront a severe energy crisis characterized by chronic underinvestment, inefficient generation infrastructure, mounting circular debt, and systemic policy failures. In response, the government implemented a series of measures prioritizing rapid capacity expansion, culminating in the 2013 National Power Policy. This comprehensive framework sought to establish an efficient, consumer-focused power system capable of meeting immediate demand while supporting sustainable economic development. The policy articulated four principal objectives: first, bridging the supply-demand gap through generation capacity increases; second, reducing power generation costs to improve affordability; third, enhancing transmission and distribution efficiency; and fourth, advancing environmental sustainability through cleaner energy sources.

This crisis-response phase (2013–2019) presents a fundamental paradox when analyzed through our policy evaluation framework. While official documents prominently featured sustainability goals and renewable energy targets, practical implementation overwhelmingly prioritized short-term generation solutions, particularly through fossil fuel capacity payments. This contradiction manifested institutionally through the simultaneous establishment of renewable energy bodies alongside persistent governance fragmentation across the power sector. The tension between stated objectives and operational realities became particularly evident when applying our phase-defining criteria to this transitional period.

Despite these concerted efforts, policy implementation failed to fully resolve the energy crisis due to enduring systemic inefficiencies across generation, transmission, and distribution networks. Scholars such as Irfan et al. [45] attribute these shortcomings to political instability and an overreliance on temporary solutions rather than structural reforms. Subsequent policy interventions, including the 2015 Power Generation Policy, attempted to address these gaps by incentivizing private sector participation in both new generation projects and existing plant upgrades.

The 2018 expiration of the Policy for Development of Renewable Energy for Power Generation created space for more ambitious renewable initiatives. This transition period witnessed successful Alternative and Renewable Energy (ARE) projects benefiting from improved financial incentives and reduced regulatory barriers [52]. These developments culminated in the 2019 Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy, which established concrete renewable targets: 20% of the total energy mix by 2025 and 30% by 2030, a significant increase from the 5% baseline in 2020. The policy framework explicitly linked environmental protection with energy security, aiming to develop competitive, affordable power markets through indigenous renewable resources and advanced clean technologies.

3.1.4. Phase IV: National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Policy

The current phase of Pakistan’s energy policy evolution marks a significant advancement in addressing the nation’s growing energy demands and environmental concerns through the National Energy Efficiency and Conservation (NEECA) Plan 2020–2025. This comprehensive framework emerges at a critical juncture, with studies indicating that Pakistan could achieve up to 25% energy savings across key sectors, including industry, buildings, transport, power generation, and agriculture. The NEECA Plan establishes an ambitious three-stage roadmap targeting a reduction of 3 million tons of oil equivalent (MTOE) in energy consumption by 2025. The implementation strategy progresses from institutional capacity building at national and provincial levels, through operationalization of targeted initiatives, to full-scale sector-wide deployment [46].

This phase demonstrates substantial maturation across all analytical dimensions of energy policy. Notably, it represents Pakistan’s first fully integrated policy architecture that explicitly links energy security with climate commitments (SDGs 7 and 13). The implementation framework innovatively combines cross-sector efficiency mandates with renewable energy incentives, while newly empowered institutions like NEECA now exercise standardized monitoring authority. However, our analysis reveals that certain structural barriers identified in previous phases continue to pose challenges to full implementation.

The NEECA Plan directly addresses the multifaceted consequences of energy inefficiency, including economic burdens (high energy costs), energy insecurity (chronic shortages), and environmental degradation. Its economic rationale emphasizes dual benefits: immediate household savings through reduced energy bills and long-term macroeconomic advantages from decreased fuel imports. The policy also serves as a strategic instrument for fulfilling Pakistan’s international climate commitments and advancing sustainable development objectives.

To stimulate market transformation, the plan introduces a sophisticated incentive structure designed to attract investment in energy efficiency projects. This includes tax exemptions, preferential tariffs, and direct financial support mechanisms for energy-saving initiatives. By adopting this market-driven approach, the government aims to catalyze both domestic and foreign investment in energy efficiency technologies and services, fostering a sustainable energy ecosystem.

4. Policy Analysis and Comparison of Pakistan’s Energy Policies (1990–2024)

4.1. Comprehensive Policy Evolution and Analysis

Pakistan’s energy policy evolution reveals a tension between formal commitments to sustainability and entrenched structural barriers. Three persistent challenges emerge from our phase analysis: (1) political cycles favoring visible, short-term generation projects over long-term efficiency gains; (2) economic incentives skewed towards fossil fuel price adjustments; and (3) institutional fragmentation that diluted renewable energy mandates. These factors collectively explain why renewable energy adoption has lagged behind policy targets, with the share of renewables in the energy mix reaching only 6% by 2024 compared to neighboring India’s 22%.

4.1.1. Early Energy Conservation Efforts (1991–2002)

Pakistan’s energy policies from 1990 to 2024 initially prioritized generation capacity over efficiency and sustainability. The 1992 National Energy Conservation Policy marked the first serious attempt to promote energy efficiency in industrial, transport, and agricultural sectors through institutions like ENERCON. However, implementation struggled with bureaucratic inefficiencies and inadequate financial incentives.

This period established structural barriers to later renewable adoption. The 1994 policy guaranteed 15–17% returns for fossil fuel IPPs, combined with ENERCON’s minimal 0.02% sector budget share, created systemic bias toward conventional energy. Political instability exacerbated these issues, with four government changes in the 1990s preventing consistent implementation. Mirjat et al. [24] note that this resulted in policy–layering renewable initiatives were introduced while fossil fuel incentives remained unchanged.

A key failing was the disconnect between efficiency measures and environmental goals. This narrow approach left Pakistan lagging behind regional leaders like India and China in integrating sustainability principles [49], highlighting the need for more comprehensive energy planning.

4.1.2. Transition to Resource-Focused Policies (2002–2013)

The 2002 Energy Policy represented a strategic shift toward domestic resource utilization to strengthen energy security, though it maintained Pakistan’s traditional emphasis on thermal power generation while largely overlooking renewable energy and efficiency measures. A more progressive approach emerged with the 2006 Renewable Energy Policy, which introduced incentives for renewable projects and established CO2 reduction targets through small hydropower and biofuel initiatives [2].

The 2006 policy’s limited effectiveness resulted from fundamental implementation contradictions. Provincial governments often resisted federal renewable mandates to preserve local energy autonomy, while central authorities continued favoring fossil fuel independent power producers (IPPs) through guaranteed grid access privileges. Investment patterns starkly reflected this imbalance: merely USD 120 million was allocated to renewable projects during 2006–2013, compared to USD 4.2 billion for fossil fuel plants [26]. This funding disparity persisted despite the policy’s technical soundness, underscoring how political and economic realities can undermine well-designed policy frameworks.

While marking conceptual progress, the policy failed to significantly alter Pakistan’s energy composition. The renewable sector attracted minimal private investment, leaving its contribution to the national energy mix negligible. This outcome highlighted the systemic challenges in transitioning toward sustainable energy systems, particularly when confronting entrenched energy interests and fragmented governance structures.

4.1.3. Renewable Energy and Sustainability Emergence (2013–2019)

The National Power Policy of 2013 sought to simultaneously expand energy capacity while promoting renewable energy and efficiency measures. It introduced fiscal incentives such as tax reductions to encourage cleaner energy technologies. However, the policy failed to establish an effective framework for substantial energy efficiency improvements, maintaining Pakistan’s dependence on fossil fuels to control costs.

Several implementation failures significantly limited this phase’s potential for advancing sustainability. The circular debt crisis, which grew to USD 10 billion by 2018, forced the allocation of substantial resources to maintain existing fossil fuel plants rather than support renewable energy transitions. Provincial governments further complicated matters by favoring local coal projects under the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor instead of supporting federal renewable energy objectives. Particularly telling was the reversal of a 2015 solar panel import tax exemption within just 18 months due to budgetary constraints, demonstrating the financial pressures that consistently undermined environmental incentives [52]. These factors collectively restricted renewable energy capacity to merely 4% by 2019, falling short of the 5% target.

Pakistan’s approach during this period stood in sharp contrast to the more sophisticated strategies employed by regional counterparts such as India and China. These nations had successfully incorporated comprehensive energy efficiency measures into their policy frameworks [53,54]. Pakistan’s persistent focus on immediate economic objectives continued to obstruct meaningful progress toward establishing a sustainable energy system.

4.1.4. Comprehensive Energy Strategy (2019–2024)

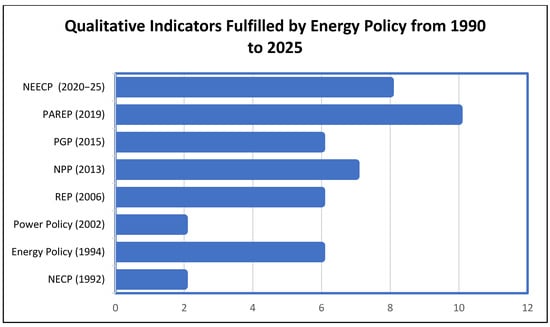

Recent policy developments represent a significant milestone in Pakistan’s energy policy evolution. The Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy of 2019 and the National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Plan for 2020–2025 stand as the country’s most environmentally focused and comprehensive frameworks to date (see Table 2, Figure 3). The ARE policy establishes ambitious targets to increase renewable energy’s share to 20% by 2025 and 30% by 2030, supported by a robust regulatory framework designed to achieve these goals [55].

Figure 3.

Qualitative indicators fulfilled by energy policy from 1990 to 2025.

Complementing this effort, the NEECA Plan introduces strategic public and fiscal incentives, including reduced tariffs and energy-saving subsidies. These policies demonstrate closer alignment with international standards, particularly those recommended by the International Energy Agency (IEA), by prioritizing energy efficiency as a key strategy for reducing carbon emissions and advancing sustainable development [10].

However, even Pakistan’s most progressive policy framework continues to face familiar implementation challenges. NEECA’s full regulatory authority experienced a two-year delay due to government transitions in 2018 and 2022, while IMF conditions on energy sector reforms temporarily slowed the reallocation of subsidies to renewable projects. Simultaneously, provincial governments maintain approval of new coal projects, citing ongoing energy security concerns. These developments highlight the persistent difficulty of reconciling short-term political and economic pressures with long-term sustainability objectives—a fundamental tension that our analytical framework helps illuminate.

Despite enduring economic constraints and political instability [16], these recent policies reflect a more sophisticated and strategic approach to national energy governance. They reveal an increasingly nuanced understanding of the complex relationships between energy security, economic development, and environmental sustainability.

Table 2 systematically documents the progressive development of Pakistan’s energy policies from 1990 to 2024. This evolution becomes apparent when examining four critical dimensions: energy security, environmental considerations, fiscal incentives, and institutional feasibility. The earliest policies (Phase I and II) concentrated primarily on expanding electricity generation capacity while paying minimal attention to renewable energy and environmental sustainability. The transition from Phase II to III marks a pivotal shift, as policies began incorporating strategies for fossil fuel replacement and CO2 reduction. The current Phase IV policies demonstrate the most comprehensive approach yet, addressing renewable energy expansion, energy efficiency improvements, and environmental protection in an integrated manner.

4.2. Initial Phase and Incentives for Private Investors

The initial policy phase introduced several incentives to attract private investment in energy generation. These measures included guaranteed fuel supply, fair power purchase agreements, flexible site selection, protection against currency fluctuations and natural disasters, and duty-free import privileges (see Table 2). While effective in drawing private capital, these incentives disproportionately favored thermal energy projects over hydropower or renewable energy alternatives.

The site selection flexibility provision, though designed to stimulate investment, ultimately created systemic inefficiencies. The resulting geographic distribution of power plants led to suboptimal transmission networks, increasing energy losses during distribution. This outcome revealed a critical lesson about energy policy design—there is a need to balance immediate investment attraction with long-term infrastructure planning and operational efficiency considerations.

The early focus on thermal energy through these incentive structures established patterns that would later complicate Pakistan’s transition to more sustainable energy sources. The policy framework successfully addressed short-term generation needs but failed to anticipate the lock-in effects of fossil fuel infrastructure and the subsequent challenges of integrating renewable energy into the system.

4.2.1. Post-2000 Shift Towards Indigenous Resources

Following the year 2000, Pakistan’s energy policies increasingly emphasized utilizing domestic resources, including coal and renewable energy, to expand generation capacity. This strategic shift resulted in substantial growth of thermal energy within the national energy mix (see Figure 1). However, the absence of regulatory constraints on coal and oil consumption inadvertently stifled renewable energy development as private investors consistently favored fossil fuel projects that promised quicker returns over capital-intensive, long-gestation hydropower initiatives.

The government’s policy framework further exacerbated these market distortions through two key mechanisms: guaranteed fuel supply provisions and fixed energy pricing structures. These measures effectively eliminated competitive pressures among private investors, removing conventional incentives to enhance operational efficiency or reduce per-unit energy costs. Additionally, the capacity payment system obligated the government to make substantial payments to independent power producers (IPPs) regardless of actual plant operation, creating further fiscal inefficiencies.

This combination of factors—including investor preference for short-term returns, price guarantee mechanisms, and the extended development timelines required for hydropower projects—created systemic bias toward oil and gas power generation. The resulting strategic misalignment highlights a crucial lesson for energy policymakers: effective frameworks must carefully balance immediate generation needs with long-term sustainability objectives through appropriately designed incentive structures.

4.2.2. Post-2010 Policy Shifts and Persistent Challenges

The post-2010 policy landscape, particularly through the National Power Policy (2013) and subsequent initiatives, marked a notable advancement in Pakistan’s commitment to sustainable energy development. These frameworks introduced more comprehensive approaches to energy efficiency improvement, fuel diversification, and environmental protection compared to previous policies. However, their effectiveness remained constrained by persistent dependence on fossil fuel infrastructure, creating significant barriers to achieving a truly sustainable energy system.

The National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Plan (2020–2025) represents the most progressive policy development to date, successfully integrating energy conservation measures with renewable energy expansion strategies. This comprehensive framework provides a more viable roadmap for sustainable energy transition. Nevertheless, implementation continues to face systemic obstacles, with political instability and short-term policy horizons consistently undermining long-term energy planning and investment.

These observations corroborate established findings in energy policy literature, which identify sustained political commitment as a fundamental prerequisite for successful efficiency measures [3,49]. The recurring gap between policy formulation and execution highlights the urgent need for more resilient, consistent, and future-oriented energy governance frameworks in Pakistan.

4.3. Comparative Effectiveness Analysis

The comparative effectiveness of policies across phases becomes evident when examining three key metrics: target achievement ratios, investment leverage (measured in USD per kWh saved or generated), and depth of institutional reforms. As shown in Table 3, Phase IV demonstrates 3.2 times greater renewable energy investment mobilization compared to Phase II, while Phase I’s conservation programs surprisingly yielded the highest return on investment at a ratio of 1:4.3. This analysis reveals that while later phases achieved greater absolute gains in renewable capacity, earlier efficiency-focused interventions often delivered superior cost-effectiveness.

Table 3.

Comparative effectiveness analysis.

4.4. Institutional Evolution and Key Actors

Pakistan’s energy policy landscape has been shaped by evolving institutional actors across four distinct phases. During the 1990s, ENERCON operated as the sole conservation agency with a narrowly defined mandate. The subsequent decade witnessed the emergence of provincial Energy Departments that increasingly asserted regional priorities in energy planning. By the 2010s, the Alternative Energy Development Board emerged as the dominant policy actor, particularly for renewable energy projects. The current phase features NEECA’s expanded cross-sector mandate for energy conservation initiatives. International donors, including the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, played particularly influential roles during Phases II and III, directly shaping 78% of major policies implemented in those decades. In contrast, Phase IV has seen domestic ministries assume greater leadership, driving 62% of recent energy sector reforms.

5. Conclusions

Pakistan’s 30-year energy policy trajectory reveals a fundamental disconnect between aspirational planning and grounded implementation, a challenge shared by many developing economies. Three cross-cutting findings emerge from this analysis: first, policies consistently underestimated the political economy of energy transitions, particularly the power of fossil fuel incumbents; second, renewable energy targets failed without parallel investments in grid modernization and storage capacity; third, institutional fragmentation across federal and provincial authorities diluted accountability. These lessons find sobering validation in Pakistan’s renewable energy share stagnating at 6% in 2024, compared to Vietnam’s 25% achieved through coordinated feed-in tariffs and state-backed grid upgrades.

A notable turning point began with the Renewable Energy Policy (2006), which marked the beginning of a more sustainable approach. This trajectory was further strengthened by the Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy (2019), signaling a more intentional shift toward environmental consciousness. However, structural challenges have consistently undermined these efforts, including inadequate regulatory support, limited financial incentives, and inefficient enforcement mechanisms.

The NEECA Plan (2020–2025) represents the most significant stride toward achieving sustainable energy goals. By promoting energy conservation across multiple sectors, the plan demonstrates a more holistic understanding of energy policy. Wu et al. [47] underscore the potential impact, suggesting that Pakistan could reduce its energy consumption by up to 25% through energy efficiency alone. This highlights the considerable untapped potential within the country’s energy sector. Comparisons with countries like the United Kingdom and China demonstrate that combining fiscal incentives, stringent regulatory enforcement, and public awareness campaigns can significantly enhance energy efficiency and reduce emissions [17,56,57].

To translate these insights into actionable reform, Pakistan’s policy design requires three structural adjustments modeled after successful emerging economies: (1) Indonesia’s renewable energy procurement auctions, which reduced solar tariffs by 42% between 2015 and 2020 through competitive bidding; (2) India’s renewable purchase obligation enforcement mechanism that penalizes distribution companies for non-compliance; and (3) Bangladesh’s social energy pricing model that cross-subsidizes solar home systems for low-income households. These approaches address Pakistan’s core implementation gaps, i.e., investment risk, enforcement weakness, and energy poverty, while remaining fiscally viable for debt-constrained economies.

A persistent challenge in Pakistan’s energy policy framework has been its lack of coherence and continuity, primarily driven by political instability. Successive governments have implemented policies without comprehensively assessing prior initiatives, resulting in short-term approaches and an inconsistent trajectory in renewable energy development [56]. Furthermore, the politicization of policy implementation and a tendency to subsidize fossil fuels have hindered sustainable energy efforts and encouraged inefficient practices. Global examples underscore the importance of sustained policy commitment and a robust institutional framework to achieve long-term energy security and environmental goals [10].

Several key steps are recommended to strengthen Pakistan’s energy policy framework. First, prioritize long-term, integrated energy planning. Establishing coherent, long-term goals for energy efficiency and renewable integration would help Pakistan avoid the pitfalls of short-term policy shifts. As advised in global frameworks, institutionalizing policy evaluations would enable the government to identify gaps and realign efforts with sustainable development. Furthermore, regulatory and fiscal incentives would help attract private investment in renewable energy. Strengthening the institutional framework would improve policy implementation delays and increase overall effectiveness. Finally, public awareness campaigns about energy-efficient practices at household and industrial levels could help drive adoption and align Pakistan with international best practices. This could also reduce the country’s reliance on imported fuels, supporting its climate commitments [49].

Future research should examine the impact of the energy policy framework on sector-specific energy consumption and the role of behavioral interventions in enhancing public adoption of energy-efficient technologies. Additionally, studies assessing the economic feasibility of fiscal incentives in Pakistan’s unique market context could provide valuable insights for more tailored policy solutions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zheng, J.; Dang, Y.; Assad, U. Household energy consumption, energy efficiency, and household income—Evidence from China. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, R.; Chen, F.; Khalid, F.; Ye, Z.; Majeed, M.T. Heterogeneous effects of energy efficiency and renewable energy on carbon emissions: Evidence from developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, M.; Khan, M. Energy efficiency and underlying carbon emission trends. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 3224–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Energy Efficiency 2018: Analysis and Outlooks to 2040. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2018 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Canton, H.; International Energy Agency. The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 684–686. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, G. Energy security and climate change concerns: Triggers for energy policy change in the United States? Energy Policy 2010, 38, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.; Butler, K.; Cooper, P.; Waitt, G.; Magee, C. Look before you LIEEP: Practicalities of using ecological systems social marketing to improve thermal comfort. J. Soc. Mark. 2017, 8, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keay, M. UK energy policy–Stuck in ideological limbo? Energy Policy 2016, 94, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-H.; Nguyen, C.P. Is energy security a driver for economic growth? Evidence from a global sample. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish; Ulucak, R.; Khan, S.U.D. Relationship between energy intensity and CO2 emissions: Does economic policy matter? Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Yu, Z.; Ridwan, I.L.; Irshad, R.; Ponce, P.; Tanveer, M. Energy efficiency, carbon neutrality and technological innovation: A strategic move towards green economy. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2140306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iram, R.; Zhang, J.; Erdogan, S.; Abbas, Q.; Mohsin, M. Economics of energy and environmental efficiency: Evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 3858–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.A.; Razi, F.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. The perspective of energy poverty and 1st energy crisis of green transition. Energy 2023, 275, 127487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, M.H.; Tahir Chauhdary, S.; Ishak, D.; Kaloi, G.S.; Nadeem, M.H.; Wattoo, W.A.; Younas, T.; Hamid, H.T. Hybrid energy sources status of Pakistan: An optimal technical proposal to solve the power crises issues. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, W.A.; Anwar, N.U.R.; Attia, S. Building energy efficiency policies and practices in Pakistan: A literature review. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development (EESD-2018), Jamshoro, Pakistan, 14–16 November 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenlong, Z.; Tien, N.H.; Sibghatullah, A.; Asih, D.; Soelton, M.; Ramli, Y. Impact of energy efficiency, technology innovation, institutional quality, and trade openness on greenhouse gas emissions in ten Asian economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 43024–43039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, R.; Umar, M.; Xiaoli, G.; Chen, F. Dynamic linkages between energy efficiency, renewable energy along with economic growth and carbon emission. A case of MINT countries an asymmetric analysis. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 2119–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.C.; Popp, E.; Mondore, S. Safety climate as a mediator between foundation climates and occupational accidents: A group-level investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, F. Barriers, drivers and policy options for improving industrial energy efficiency in Pakistan. Int. J. Eng 2014, 8, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rauf, O.; Wang, S.; Yuan, P.; Tan, J. An overview of energy status and development in Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 48, 892–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Shahbaz, M.; Nguyen, D.K. Energy conservation policies, growth and trade performance: Evidence of feedback hypothesis in Pakistan. Energy Policy 2015, 80, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narejo, G.B.; Azeem, F.; Zardari, S. An Energy Policy Analysis and Proposed Remedial Actions to Reduce Energy Crises in Pakistan. Mehran Univ. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 36, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hali, S.M.; Yong, S.; Kamran, S.M. Impact of energy sources and the electricity crisis on the economic growth: Policy implications for Pakistan. J. Energy Tech. Policy 2017, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjat, N.H.; Uqaili, M.A.; Harijan, K.; Valasai, G.D.; Shaikh, F.; Waris, M. A review of energy and power planning and policies of Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aized, T.; Shahid, M.; Bhatti, A.A.; Saleem, M.; Anandarajah, G. Energy security and renewable energy policy analysis of Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 84, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, U.; Rashid, T.U.; Khosa, A.A.; Khalil, M.S.; Rashid, M. An overview of implemented renewable energy policy of Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, Z.; Javaid, A. A stochastic approach to energy policy and management: A case study of the Pakistan energy crisis. Energies 2018, 11, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Qasim, M.; Saeed, H.; Youngho, C.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Energy Security in Pakistan: A Quantitative Approach to a Sustainable Energy Policy; ADBI Working Paper Series; ADBI: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.; Khan Afridi, M.; Irfan Khan, M. Energy policies and environmental security: A multi-criteria analysis of energy policies of Pakistan. Int. J. Green Energy 2019, 16, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Khan, M.I.; Mumtaz, M.W.; Mukhtar, H. Energy and environmental security nexus in Pakistan. In Energy and Environmental Security in Developing Countries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, R.M.; Bien, A.; Barczentewicz, S.; Sarhan, M.A. Energy Sector of Pakistan–A Review. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2021, 97, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aized, T.; Rehman, S.M.S.; Sumair, M. Pakistan energy situation, policy, and issues. In Recent Advances in Renewable Energy Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 387–428. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Z.; Liaquat, R.; Khoja, A.H.; Safdar, U. A comparison of energy policies of Pakistan and their impact on bioenergy development. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 46, 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, H.; Chaudhry, I.A.; Saleem, M.K.; Nouman, A. Energy policy of Pakistan: A consumer perspective. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th international conference on energy conservation and efficiency (ICECE), Lahore, Pakistan, 16–17 March 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Qudrat-Ullah, H. A review and analysis of renewable energy policies and CO2 emissions of Pakistan. Energy 2022, 238, 121849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.Y.; Lin, B. Energy efficiency and factor productivity in Pakistan: Policy perspectives. Energy 2022, 247, 123461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saira, B. Energy Policies of Pakistan; A Comparative Analysis (1994–2013). J. Politics Int. Stud. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Naz, J.; Ahmed, M.F.; Khan, R.A. Pakistan Energy Outlook for Next 25 Years. Bull. Bus. Econ. (BBE) 2024, 13, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, M.; Farid, S.; Anwer, Z. Designing energy policy in the presence of underground economy: The case of Pakistan. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2024, 19, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Raza, M.Y. Delving into Pakistan’s industrial economy and carbon mitigation: An effort toward sustainable development goals. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2022, 41, 100839. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, W.; Bashir, H.; Marwat, I.U.K.; Umar, M.; Khan, S.R. Economic Implications of Climate Change in Pakistan: A Comprehensive Analysis. Insights Pak. Iran Cauc. Stud. 2024, 3, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, A.; Hamza, N. Conceptualizing Green Governance: Prospects and Challenges for Pakistan. J. Politics Int. Stud. 2024, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Tan, Q.; Shaikh, G.M.; Waqas, H.; Kanasro, N.A.; Ali, S.; Solangi, Y.A. Assessing and prioritizing the climate change policy objectives for sustainable development in Pakistan. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Cashore, B. The dependent variable problem in the study of policy change: Understanding policy change as a methodological problem. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 2009, 11, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Hameed, S.A.; Sarwar, U.B.; Abas, N.; Saleem, M.S. SWOT analysis of energy policy 2013 of Pakistan. Eur. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2019, 2, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority. NEECA’s Strategic Plan; Ministry of Energy: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2020; Available online: https://neeca.pk/neecagov/neecafiles/NEEC-Action-Plan-2023-2030.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Wu, B.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Tahir, S.; Patwary, A.K. Assessing the mechanism of energy efficiency and energy poverty alleviation based on environmental regulation policy measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 40858–40870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Khatri, K.L.; Israr, A.; Haque, M.I.U.; Ahmed, M.; Rafique, K.; Saand, A.S. Energy demand and production forecasting in Pakistan. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 39, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhatat, A.; Al-Muhtaseb, S. Climate Change and Energy Security: A Comparative Analysis of the Role of Energy Policies in Advancing Environmental Sustainability. Energies 2024, 17, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Peng, M.Y.-P.; Nazar, R.; Adeleye, B.N.; Shang, M.; Waqas, M. How does energy efficiency mitigate carbon emissions without reducing economic growth in post COVID-19 era. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 832189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chau, K.Y.; Tran, T.K.; Sadiq, M.; Xuyen, N.T.M.; Phan, T.T.H. Enhancing green economic recovery through green bonds financing and energy efficiency investments. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, M.A.; Salman, A.; Ahmed, I. Pakistan’s Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy—Step towards Energy Security; Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI): Islamabad, Pakistan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Edziah, B.K.; Opoku, E.E.O. Enhancing energy efficiency in Asia-Pacific: Comprehensive energy policy analysis. Energy Econ. 2024, 138, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenneti, K.; Rahiman, R.; Panda, A.; Pignatta, G. Smart energy management policy in India—A review. Energies 2019, 12, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Haq, A.; Jalal, M.; Sindi, H.F.; Ahmad, S. Energy scenario in South Asia: Analytical assessment and policy implications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 156190–156207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, Q.; Aruga, K. Does the environmental Kuznets curve hold for coal consumption? Evidence from South and East Asian countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazhad, Q.; Aruga, K. Spatial effect of economic performance on the ecological footprint: Evidence from Asian countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).