Abstract

Energy communities led by local citizens are vital for achieving the European energy transition goals. This study examines the design of a regional energy community in a rural area of Spain, aiming to address the pressing issue of rural depopulation. Seven villages were selected based on criteria such as size, energy demand, population, and proximity to infrastructure. Three energy valorization scenarios, generating eight subscenarios, were analyzed: (1) self-consumption, including direct sale (1A), net billing (1B), and selling to other consumers (1C); (2) battery storage, including storing for self-consumption (2A), battery-to-grid (2B), and electric vehicle recharging points (2C); and (3) advanced options such as hydrogen refueling stations (3A) and hydrogen-based fertilizer production (3B). The findings underscore that designing rural energy communities with a focus on social impact—especially in relation to depopulation—requires an innovative approach to both their design and operation. Although none of the scenarios alone can fully reverse depopulation trends or drive systemic change, they can significantly mitigate the issue if social impact is embedded as a core principle. For rural energy communities to effectively tackle depopulation, strategies such as acting as an energy retailer or aggregating individual villages into a single, unified energy community structure are crucial. These approaches align with the primary objective of revitalizing rural communities through the energy transition.

1. Introduction

The deployment of energy communities (ECs) plays a crucial role in Europe’s decarbonization efforts. These initiatives not only transform the role of citizens in the energy transition but also empower them to achieve greater energy autonomy, contribute to the democratization of the energy system, and mitigate the impact of energy price volatility. Moreover, ECs foster positive societal change by enhancing the local value and resilience of the regions in which they are implemented.

The European Union defined ECs in two directives: the Renewable Energy Directive EU 2018/2001 (REDII) and the revised Internal Electricity Market Directive EU 2019/944 [1,2]. These Directives define the ‘Renewable Energy Communities’ (RECs) and the ‘Citizen Energy Communities’ (CECs), respectively. Both Directives promote community participation in the energy transition as well as sustainable energy practices [3]. The main differences between RECs and CECs lie in their geographical and technological scope. RECs require members to be located near the renewable project and are limited to renewable energy, while CECs have no geographic or technological restrictions. Both allow participation from individuals, local authorities, and small/microenterprises, although RECs require that members’ primary activities are unrelated to their involvement. RECs can operate broadly in the renewable energy market, whereas CECs focus on member-targeted energy services and broader electricity sector activities [4].

Although citizen-led initiatives for generating and/or self-consuming clean energy are not entirely new, both CECs and RECs are specifically designed to deliver environmental, economic, and social benefits to their members or stakeholders. While the environmental advantages of renewable technologies are well established, and economic gains are increasingly evident given current energy prices, the social benefits remain poorly defined and insufficiently integrated into the planning and implementation of RECs and CECs.

This study addresses that gap by proposing a research approach focused on how an energy community (EC) can define and implement a social roadmap aligned with the techno-economic performance. The goal is to enhance the local social impact generated by a REC/CEC through strategic surplus energy valorization, understanding surplus as the amount of energy production that exceeds a defined energy demand. To this end, we review the current mechanisms available to ECs in Spain for managing energy surpluses—acknowledging that variations may exist across countries—and propose three distinct surplus valorization scenarios. These scenarios are then evaluated regarding both economic viability and the social value they generate within their respective regions. The overarching objective is to assess the potential of ECs to foster local value creation through integrated social and economic strategies.

1.1. Type of Valorization Strategies

Option 1: Energy surplus selling.

In the simplified monthly net-billing system, surplus electricity revenues are deducted from the self-consumer’s monthly bill, offering advantages such as reduced administrative burden, exemption from grid-access charges and generation taxes, and non-taxable savings [5,6]. However, in Spain, it is limited to installations under 100 kWp, and savings cannot exceed the bill’s value—certain fixed charges remain uncompensated [5,6]. Alternatively, direct selling enables users to sell surplus electricity at market prices (minus a 7% generation tax and EUR 0.5/MWh grid fee), without billing limits or capacity constraints. However, it involves higher administrative complexity [5,6]. Dasí-Crespo et al. (2023) [6] found that net billing leads to higher electricity costs and longer payback periods, while López Prol and Steininger (2020) [5] noted it offers higher returns, albeit with capped total benefits.

Another option is for an energy community to operate as an energy retailer, enabling it to sell surplus energy directly to consumers [7,8].

Option 2: Energy surplus storage: electric storage and hydrogen storage.

Energy storage is essential due to the intermittent nature of renewable energy production, caused by climatology variability and mismatches between production and demand, which can lead to grid instability or hostile prices. Grid-scale storage supports the expansion of low-emission energy sources and ensures clean energy availability during periods of low renewable generation [9,10]. Various energy storage methods, including compressed air, pumped hydro, flywheels, capacitors, superconducting magnets, thermal storage, battery storage (BES), and hydrogen storage, are explored in the literature [9,11]. This paper focuses on batteries and hydrogen storage.

Batteries offer rapid response times, high energy efficiency, and commercial potential, but face challenges such as high costs, short lifespans, and temperature sensitivity [10,11]. They allow surplus solar energy to be stored for later use at electricity tariff rates, although their higher initial costs can be offset as solar technology prices drop [12]. In Spain, energy communities (CECs/RECs) can install shared energy storage systems (art. 5.7 RD 244/2019 [13]). The legislation stipulates that energy stored in shared batteries must be used exclusively to offset the demand of self-consumers associated with the energy community. There is no option to inject this energy into the grid for compensation unless the community operates as an energy retailer. In this case, they are also allowed to use surplus energy for additional purposes, such as supplying public charging stations.

Different types of batteries are described in the literature for different applications for energy storage: Lead-acid (Pb-A), Lithium-ion (Li-ion), Nickel-cadmium (Ni-Cd), Vanadium-based flow, Sodium-sulfur (Na-S) and Aluminum-ion, among others [10,11,14,15].

Lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries are the most used in renewable energy systems. The advantages include a long cycle life, a wide temperature range, rapid charging, high energy density, and high efficiency. However, they also have some drawbacks, including high initial costs and the need for frequent charging. Li-ion batteries typically achieve efficiencies of around 90–94% with system costs ranging from EUR 540 to EUR 3600/kWh [10,11,14,15]. However, prices are dropping quickly. According to Bloomberg [16], by the end of 2023, prices fell below EUR 129/kWh.

Hydrogen storage is a promising alternative for managing energy surpluses in renewable energy systems, mainly due to its high energy density (33 kWh/kg) [17] and versatility. Green hydrogen—produced via water electrolysis using renewable electricity—offers a clean, zero-emission energy carrier suitable for seasonal storage, with potential applications in fuel cells, internal combustion engines, and as a precursor for other energy vectors [9,17,18,19,20].

Electrolyzers, which split water into hydrogen and oxygen, play a key role in this process. While theoretical electrolyzer efficiency is around 80–85% [17], practical values vary between 56–87.6%, with an average of approximately 75% depending on the technology and operating conditions [19,21,22,23]. Solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, often coupled with electrolyzers, show average efficiencies of around 21.9% [24], which results in a solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency of about 17% [25]. Other studies report STH efficiencies ranging from 5.1% to 31.5% [26,27,28], with current commercial performance typically below 20% [18]. Although direct photoelectrolysis is still under development, it shows promise, with experimental efficiencies reaching up to 30% [27].

Hydrogen production efficiency also depends on the electricity input required per kilogram of hydrogen. Reported values range between 45–83 kWh/kg H2, depending on the electrolyzer type and conditions [29,30].

From an economic perspective, the cost of green hydrogen is currently a limitation. The levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) varies widely across studies: from EUR 1–2.7/kg H2 [18] to values as high as EUR 30.4/kg H2 for small-scale off-grid systems [30]. More typical ranges are EUR 3.3–9.7/kg H2 [17,23,28]. Electrolyzer capital costs also differ by type: EUR 477–1335/kW for alkaline, EUR 1049–1716/kW for PEM, and EUR 2670–5540/kW for SOEC, with projected reductions expected by 2030 [31].

Despite current cost challenges, studies suggest that integrating solar PV and electrolyzer systems (e.g., using direct DC coupling and shared infrastructure) can reduce investment costs—up to 20% in 100 MW plants—making green hydrogen increasingly competitive in the energy market [18].

Several studies have compared hydrogen and battery-based energy storage systems. Zaik et al. (2023) highlight that while batteries are well-suited for small-scale energy systems and short-term storage, hydrogen presents clear advantages for long-term and seasonal storage due to its ability to stabilize fluctuations in electricity generation from renewable sources [19]. Similarly, Brey (2021) concludes that hydrogen is the most suitable energy storage and management solution to meet the requirements of the Spanish energy system by 2030 and 2050 [21].

The application of hydrogen in the transport sector has been widely studied and compared to conventional fuels. In terms of energy efficiency, hydrogen outperforms gasoline, storing approximately 2.6 times more energy per unit mass. However, due to its lower volumetric energy density, hydrogen requires around four times more storage volume to deliver the same energy, which reduces vehicle driving range in practice [20]. Lao et al. (2021) compared hydrogen with diesel use in vehicles, highlighting that fuel cells operate at efficiencies of 60–80%, significantly higher than diesel engines (<40%) [32]. Additionally, diesel engines operate at higher temperatures (800–1000 °C), leading to emissions of pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), whereas hydrogen combustion produces only water, posing no environmental harm [32]. Their study also showed that heavy-duty trucks powered by hydrogen could reduce energy consumption per 100 km by up to 82% compared to their diesel counterparts.

Nonetheless, when comparing hydrogen and battery-electric vehicles (BEVs), the literature indicates that BEVs achieve nearly twice the efficiency of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, which explains why manufacturers currently tend to prioritize battery-powered over hydrogen-powered vehicles [18].

Moreover, there are some other uses of hydrogen. The integration of electricity generation, hydrogen production, and other valuable products is beneficial for the local economy [20]. To cite some products from hydrogen: for the agriculture sector, the synthesis of ammonia with other nitrogenated fertilizers [17,19,20,33]; for metal refining, such as nickel, tungsten, molybdenum, copper, zinc, uranium, and lead [19,20]; for industrial applications for hydrogen-based steel making and chemicals [18]; for the synthesis of methanol, ethanol, dimethylether (DME), e-methane, and Fischer–Tropsch fuels [18,19,20].

1.2. Social Impact of ECs

Europe is currently facing a major social challenge in rural areas, which are increasingly affected by depopulation. These regions often contend with a range of difficulties, including limited employment opportunities, restricted access to public services and commercial facilities, and underdeveloped infrastructure—particularly in energy, transportation, and communication.

While rural areas do offer certain advantages—such as improved quality of life, more living space, lower pollution levels, and more affordable housing—these benefits are frequently overshadowed by the disadvantages. Consequently, many individuals opt to relocate to urban centers in search of better opportunities, further accelerating the trend of rural depopulation [34].

In 2021, rural areas accounted for 45% of the European Union’s territory. However, only 21% of the population resided in these regions during that same year. Between 2015 and 2020, rural areas experienced an average annual population decline of 0.1% [35].

ECs offer a promising solution to the challenges faced by rural areas. From a social standpoint, ECs bring significant benefits by fostering citizen engagement, empowering local communities, and strengthening social cohesion.

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify the indicators that can be used to measure the social impacts of community-based projects, bioenergy initiatives, social farming, and similar undertakings. These indicators help us understand how ECs can contribute to improving the quality of life in rural areas—by creating local employment opportunities and promoting sustainable development. As for the later purpose of this paper, the identified indicators were categorized into six groups based on their community-level impact: (1) Local capacity building, (2) Improvement of the local economy, (3) Behavioral changes within the community, (4) Energy security and access, (5) Employment, and (6) Civic participation. These categories were further grouped into three broader dimensions:

- Individual well-being—focuses on personal outcomes, such as success, education, health, and overall welfare.

- Community well-being—refers to social factors that influence the cohesion and development of a particular community or region.

- Societal impacts—encompasses broader, systemic effects that extend beyond local boundaries and contribute to addressing global social challenges.

A summary of these indicators is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Social indicators organized at the community level.

Recognizing the potential of ECs to generate local value and deliver meaningful social benefits, residents of the Calatayud region in Zaragoza, Spain—a rural area encompassing 67 villages and 20 hamlets—embraced ECs as a strategic solution to counter rural depopulation and promote regional revitalization.

In this context, the central research question is: How can the social impact of an energy community be maximized beforehand?

Most existing EC initiatives tend to view social impact as a secondary outcome—emerging from technical design decisions and the legal or administrative processes involved in project implementation, such as organizing meetings, maintaining engagement, or fostering participatory actions. Likewise, environmental benefits are often treated as indirect results of the decentralized technologies adopted, influenced by available public subsidies, rather than being deliberate objectives of the project.

This approach raises a fundamental question: Can the expected social impacts of an energy community serve as the driving force behind its technical design? If so, what framework or methodology is needed to support this shift?

We propose a paradigm change—moving away from rigid, predefined models focused solely on maximizing self-consumption. Instead, we suggest developing a flexible roadmap that integrates techno-economic scenarios with measurable social outcomes. This methodology enables ECs to be tailored to the specific needs, contexts, and priorities of different regions.

There is a growing need to address the challenges associated with implementing energy community (EC) models. However, there is still a lack of empirical evidence regarding their social benefits, as well as standardized methodologies for assessing social impact. Mapping the relationship between different energy models and their societal impacts allows policymakers and stakeholders to design inclusive and context-sensitive strategies. The innovative approach of this paper enables assessing indicators of social impact to enhance civic participation, address energy poverty, and support a just, equitable energy transition that delivers maximum benefit to all members of society. This study focuses on rural areas, where depopulation is an increasingly significant reality. The authors of this work maintain a research focus in this area, having previously developed models for EC-driven projects within university communities, where social impact is the primary design driver [42,43].

2. Methodology

The methodology employed in this paper first assesses the economic impact of different technical scenarios by converting the energy surplus of the EC into monetary value, facilitating a clear understanding of how to valorize them. Subsequently, this economic value is transformed into social value by reallocating the financial benefits towards the intended purpose, aiming to generate local returns for the area. These benefits are analyzed in terms of equivalent person-years—understood as the number of minimum-wage jobs that could be created per year in each scenario and village—providing a tangible measure of the social impact generated.

2.1. Case Study

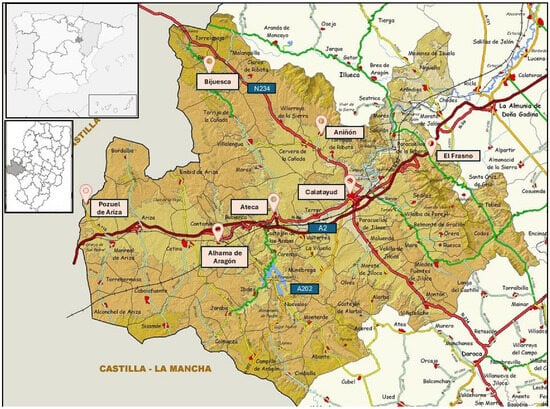

The case study for this research is in the Calatayud region of Zaragoza, Spain (Figure 1), and it has been conducted within the framework of the JALON (LIFE) project [44], which aims to establish a regional EC in a rural area of 2518 km2 to address social challenges. This regional energy community, called CERCA, aims to simplify bureaucratic procedures by centrally managing all installations across the 67 villages and 20 hamlets in the region. The goal is to minimize the administrative burden typically associated with these kinds of projects, especially in the smallest municipalities.

Figure 1.

Location of the seven villages analyzed in this paper and the main roads considered for Scenarios 2C and 3A (source: Aragonería [45] and modified by the authors).

The project plans to install a total renewable energy capacity of 4 MWp, with 825 kWp already deployed. The project roadmap includes PV installations of 3, 15, and 60 kWp. However, the case studies presented in this paper refer only to selected villages with 3 kWp and 60 kWp installations.

For this study, seven villages—Alhama de Aragón, Aniñón, Ateca, Bijuesca, Calatayud, El Frasno, and Pozuel de Ariza—were selected for analysis. These villages vary in terms of geographic location from the main roads (see Figure 1, identified as A2, A-202, and N-234), population size, and number of electricity contracts, as detailed in Table 2).

Table 2.

Villages characteristics.

Since this study is conducted using aggregated consumption data, the individual consumption patterns of the residents or specific variations within each population are unknown. This limits the ability to perform a detailed analysis at the individual level and may affect the accuracy of consumption projections and the impact on energy distribution within the community. Population data were obtained from the official census. Energy demand was obtained from [46].

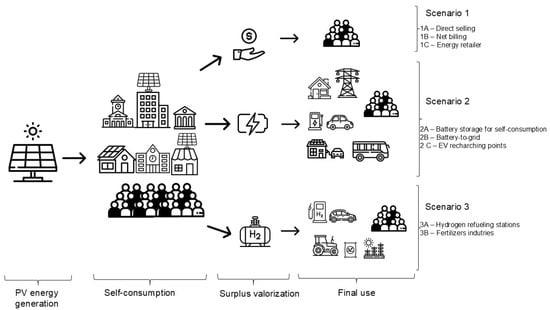

2.2. Technical Scenarios Definition

The approach identifies distinct scenarios for utilizing the energy surplus, which are depicted in Figure 2. The energy pathway is divided into four stages: generation of PV energy, self-consumption in the villages, surplus valorization, and final use. Regarding surplus management, the following scenarios have been considered, and each further divided into subscenarios:

Figure 2.

Visual scheme of the different scenarios proposed in this paper.

- Direct Sale to the Power Grid (Scenario 1): This scenario evaluates selling the surplus, with the aim of generating revenue that can be reinvested in local projects. It includes three subscenarios:

- Direct Sale (Subscenario 1A): Selling the surplus to the grid without intermediaries.

- Net Billing (Subscenario 1B): A simplified mechanism for compensating the surplus produced and injected into the grid against the consumer’s electricity bill.

- Sell to Other Consumers (Subscenario 1C): Selling the surplus to other consumers, acting as an energy retailer.

- Battery Storage (Scenario 2): This scenario examines storing the energy surplus in batteries for future use, including powering electric vehicle (EV) charging points. Three subscenarios are considered:

- Storage for Self-Consumption (Subscenario 2A): Utilizing stored surplus energy to cover the energy demands of local energy community members during times of low solar output.

- Battery-to-Grid (Subscenario 2B): Using stored surplus energy for grid injection, acting as an energy retailer.

- EV Charging Points (Subscenario 2C): Using stored surplus energy to power EV charging stations, promoting sustainable mobility.

- Hydrogen Strategies (Scenario 3): This scenario involves converting the surplus energy into hydrogen through electrolysis, and exploring its potential uses. Two subscenarios are included:

- Hydrogen Refueling Stations (Subscenario 3A): Implementing infrastructure to supply hydrogen as a clean fuel for transportation.

- Fertilizer Production (Subscenario 3B): Using hydrogen to synthesize ammonia for fertilizer production can support the local agricultural industry. Although such industries are highly energy-intensive—requiring approximately 15,000 MWh per day—we include this scenario as part of a tentative policy roadmap aimed at promoting the optimal use and valorization of energy within rural energy communities, particularly within the framework of a defined autonomous community.

2.3. Techno-Economic Assessment Methodology

For the calculation of the economic impact of the different scenarios, evaluating the costs of the installations for each scenario is required. All scenarios have in common the PV facilities.

PV installations are calculated based on public 2022 real data of the villages [46]. It is assumed that the EC accounted for 14% of the total annual energy consumption of each village, based on a uniform energy demand distribution across the population. According to the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, this percentage corresponds to the early adopters [47]. Additionally, it was considered a self-sufficiency ratio (SSR) of 34% of the energy consumption for the EC, with the remainder being procured from the grid [5,48]. A 55.92% factor assesses the EC’s consumption relative to production.

The sizing of the PV facilities was determined by dividing annual energy production by the solar hour equivalent in the region (1550 h [49]) to determine the capacity each village required for EC consumption. We considered facilities with capacities of 3 and 60 kWp, with costs of EUR 1.84 and EUR 0.74/Wp, respectively. This way, the PV facilities are dimensioned, and the total cost is calculated.

2.3.1. Scenario 1

In this scenario, the surplus PV production is sold. In Scenarios 1A and 1B, energy is supplied to the grid, while in Scenario 1C, it is delivered to other neighbors. In the latter case, and within the Spanish regulatory framework, the EC must act as an energy retailer.

In direct selling (Scenario 1A), the payment received for surplus energy is variable and tied to the market energy price [6]. A comparison of daily energy prices for selling and purchasing from the grid in 2023 revealed that the average selling price was EUR 0.0871/kWh [50], while the average purchasing price was EUR 0.1468/kWh [51]. A 7% energy production fee and a grid-access fee of EUR 0.5/MWh are factored in.

On the other hand, the simplified monthly net-billing system (Scenario 1B) applies only to villages with installations below 100 kWp, according to national legislation [13]. This analysis specifically pertains to systems with a maximum installed capacity of 60 kWp. A comparison of daily surplus energy prices from self-consumption under the simplified compensation mechanism for 2023 was conducted using data from the Spanish Grid Regulator (REE). The average daily price for surplus energy in 2023 was calculated at EUR 0.0857/kWh [52].

Additionally, common self-consumption expenses, accounting for 15.62% of the selling price, are considered.

Scenario 1C, which involves operating as an energy retailer, is applied uniformly across all villages. Several taxes are imposed on the energy retailer: a 21% VAT, a 5.11% electricity tax [53], and an economic activities tax of EUR 0.721/kWp [54]. Additionally, a 7% tax on energy production and a grid-access fee of EUR 0.50/MWh are considered. To operate legally, the energy retailer must be registered in the Retailers’ Registry, which incurs a one-time tax of EUR 97.45 [55], applicable only in the first year. The EC sells surplus electricity at the market price (EUR 0.1468/kWh), plus a management fee of EUR 0.05/kWh.

2.3.2. Scenario 2

In this scenario, surplus energy is valorized through various strategies, including the use of batteries as a storage solution.

In this study, Li-ion batteries are the chosen energy storage system to analyze in Scenario 2, with an average efficiency of 92% and an average price of EUR 129/kWh [16]. A lifespan of 10 years has been considered.

This scenario proposes three distinct cases for surplus energy storage and use:

Scenario 2A: Total energy surplus storage in batteries. In this case, batteries are sized to store all the energy surplus, considering the cost of batteries. Surplus energy is sold to the members of the EC at market price (EUR 0.1468/kWh).

Scenario 2B: Total energy surplus storage in batteries for grid injection. In this scenario, the cost of batteries for storing all the surplus is considered. The price is set at the market price (EUR 0.1468/kWh), plus a management fee of EUR 0.05/kWh. It considers a grid-access fee of EUR 0.50/MWh and a tax on energy production of 7%.

Scenario 2C: Installation of EV charging points. This case considers towns located near high-traffic roads. To determine eligibility, we calculated the distance between each town and the nearest major road (A2, A-202, or N-234), selecting towns within a 10 km radius. The efficiency of EV charging points is assumed to be 45–50%, and the amount of energy available for EVs is determined by the surplus PV production. The energy is sold to users at a rate of EUR 0.5/kWh [56]. Additionally, the cost of each charging point is estimated at EUR 2000 [57]. Each point requires a minimum of 177 kWh/day. Any remaining surplus energy is sold to the grid, including taxes. Towns with insufficient surpluses for building an EV charging point are excluded from the analysis. A lifespan of 9 years has been considered for the chargers [58]. If there is remaining surplus energy, it is sold to the grid. Although not addressed in this paper, assessing local energy needs for electric vehicles and hydrogen could, on its own, justify the installation of EV or hydrogen stations (Scenario 3A) in villages—even those not located near major roads.

2.3.3. Scenario 3

This scenario explores the valorization of energy surpluses through hydrogen storage, with two distinct approaches: hydrogen refueling stations (HRSs) to supply hydrogen vehicles (Scenario 3A), and hydrogen production for use in fertilizers (Scenario 3B).

In Scenario 3A, the focus is on HRSs, which are like EV charging points (Scenario 2C). Only towns located within 10 km of major roads are considered. Towns with insufficient surpluses for building an HRS are excluded from the analysis. Two types of HRS are evaluated: Type 1 (20 kg H2 capacity) and Type 2 (60 kg H2 capacity). The storage requirements for light vehicles (5 kg H2) and heavy vehicles (30–35 kg H2) are also considered. The efficiency of the HRS is 64 kWh per kg of H2, meaning that 1 kg of hydrogen requires 64 kWh of electricity. Type 1 stations need a minimum surplus of 1280 kWh/day of PV energy, while Type 2 stations require 3840 kWh/day. Any surplus electricity beyond the needs of the HRS is sold to the grid, including taxes. Hydrogen at the HRS is sold at EUR 10/kg H2 [59]. The installation cost for the HRS is based on a study by Repsol, with an average cost of EUR 1,800,000 for an HRS that can store 100 kg H2 [60]. If there is remaining surplus energy, it is sold to the grid.

In Scenario 3B, the potential for producing hydrogen through electrolysis and using it to create ammonia (NH3) for fertilizers is analyzed. Hydrogen is produced via the electrolysis of water (green hydrogen), with nitrogen (N2) extracted from the air. The electrolysis process requires an electrolyzer, which has an efficiency of 64 kWh per kg of H2. The cost of the electrolyzer, including the compressor, is based on 2022 price predictions at EUR 669.1/kW. Water consumption for the electrolyzer is 0.01054 m3 of water per kg of H2, with water priced at EUR 1.52/m3 in the Aragón region. The hydrogen is then stored in a tank that requires a compressor with an efficiency of 88%, consuming 4 kWh per kg of compressed H2 [61]. The cost of the compressor is factored into the overall price. A lifespan of 15 years has been considered for the electrolyzers [62].

Next, the hydrogen is used in a Haber–Bosch reactor for NH3 production, with a consumption rate of 0.6 kWh per kg of NH3 produced. An air separation unit (ASU) is used to extract nitrogen from the air, consuming 0.119 kWh per kg of N2 [63]. The price for the reactor and ASU is estimated at EUR 870/kW [62]. Since the surplus energy is not sufficient to cover the entire process, energy is purchased from the grid for these operations. The process follows the required ratio of raw materials: 5.7 kg of NH3 is produced for every 1 kg of H2, and 4.7 kg of N2 is needed per kg of H2.

Finally, to determine the economic viability, the amount of NH3 produced is converted into a monetary value, based on a 2022 market price of EUR 976.6/ton of NH3 [64].

2.4. Social Assessment Methodology

Assessing the indicators outlined in the literature is crucial for evaluating the social impact of a defined EC scheme. We categorize these indicators into two distinct groups:

- Monetary Value Indicators: These reflect the economic impact and the reinvestment of benefits back into the community.

- Informative Value Indicators: These capture both qualitative and quantitative aspects related to social and environmental impact.

Once the values are defined, and considering that the goal of the EC is to act as a revitalizing element for the local economy, fostering population growth, we establish the following workflow:

- Financial Benefit (Economic Profitability): This is achieved through surplus management, which varies across scenarios. The benefits are assessed over 5, 10, 20, and 28-year periods.

- Investment and Operational Costs: These costs, which are necessary to create and maintain the EC as a cooperative, including hired workers, are subtracted from the EC’s benefits in each scenario. It is assumed that 14% of the population participates with a EUR 100/share.

- Taxation of Profits: Profits are taxed at a rate of 19%, with the resulting revenue assumed to be reinvested by local authorities into education, healthcare, infrastructure, and other community services.

- Participants’ Gains: Participants benefit from reduced electricity costs due to self-consumption ensuring a 34% SSR, leading to energy savings that are not included in the impact since it is not a collective impact, but an individual impact.

- Profit Distribution: This aspect will depend on the specific configuration of the EC. While economic benefits should not be the main objective of these structures, as stated in the European Directive, profitability is not prohibited. The key issue is to what extent the other benefits outlined in the Directive are also met. In our model, 20% of the profits—after covering costs and taxes, as described in points 2 and 3—are distributed among the cooperative members. This allocation aims to incentivize collective participation in energy communities over individual installations. Those with standalone systems can generally handle the surplus through net billing, achieving comparable profitability.Although these are private funds, they could contribute to an increase in local GDP, serving as a key indicator of social impact. However, this increase in GDP is not considered in the analysis since the funds do not remain within the cooperative’s management and it is not easy to link them to a local impact.

- Retained Profits: The remaining 80% of the profits are retained by the cooperative and reinvested to generate social value and stimulate the local economy. The allocation of these funds is guided by the cooperative’s social roadmap and may include initiatives such as supporting the creation of new businesses, fostering social cohesion through festivals, tourism programs, clubs, and promotional campaigns, raising awareness of key issues, improving access to energy, and providing job training and skill development programs aimed at creating new employment opportunities in the region.

- Person-Year Equivalent: Based on Spain’s 2022 minimum wage of EUR 14,000 per year [65], we calculate the equivalent number of person-years that 80% of profits (point 6) would generate for each village over the assessment period. This is used to estimate the potential increase in population. We also identify the cost of generating such a person-year equivalent under each scenario.

It is important to highlight that this work does not claim that the job positions indicated as person-year equivalents will be directly created. The aim is to assess the benefits obtained in terms of employment potential and the cost of generating such jobs. However, how these jobs would be created remains a “black box” that, as noted above in point 6, requires a strategy focused on indirectly creating the social and economic conditions necessary for these jobs to eventually emerge.

3. Results

In this section, an evaluation of the three scenarios is conducted, focusing on both techno-economic and social aspects.

3.1. Economic Profitability

For each village in the Calatayud region, the three surplus valorization scenarios are analyzed. Economic profitability is determined using net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), and the profitability index. The NPV represents the current value of the net cash flows resulting from a specific investment, IRR is defined as the value at which NPV equals zero, and the profitability index is calculated as the NPV divided by the initial investment for each village and scenario [66,67]. The profitability index represents the amount of money obtained for each EUR invested in the project. If the profitability index is greater than 1, this means that the scenario is profitable for the village [66]. Villages with a positive NPV and an IRR above 10% are considered economically viable, while those failing to meet both criteria are excluded from this study. These economic results are summarized in Table 3 where the first column indicates the initial investment requested to set up a technological scenario. The following subsections provide a detailed analysis of these findings.

Table 3.

Economic assessment of the seven villages selected (28 years). For easy visual comparison, feasible scenarios are formatted in green font, while non-feasible scenarios are shown in red font.

3.2. Social Assessment

Once the scenarios are economically assessed, the social impact is subsequently evaluated. To do so, an additional economic analysis is conducted over different investment payback periods—5, 10, 20, and 28 years—following the methodology outlined in Section 2.4. The aim is to identify from which year onwards the generated revenues could be translated into “equivalent person-years”, representing a potential increase in the local population (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Returns of investments in terms of equivalent person-years.

Only scenarios with a positive NPV are considered for the social impact analysis, as these indicate a financial return that can be reinvested into social outcomes.

4. Discussion

Different technological scenarios have been developed for seven municipalities to manage a specific amount of energy surplus. The benefits generated in each case have been translated, following the previously described methodology, into a figure of equivalent person-years. It has been observed that these benefits vary depending on the municipality, the scenario considered, and the strategy adopted.

The following section analyses the results to identify not only the strategy that would yield the highest social return in each town but also the critical technical design aspects that can significantly influence the scale of the resulting social impact.

4.1. Scenario 1

In the case of direct selling, certain municipalities—specifically Alhama de Aragón, Aniñón, Ateca, Calatayud, and El Frasno—achieve profitability under Scenario 1A. In contrast, others—Bijuesca and Pozuel de Ariza—do not reach economic viability when selling surplus energy to the grid.

Regarding net billing, villages with 60 kWp installations are profitable in this scenario, while small villages such as Pozuel de Ariza and Bijuesca are not profitable. However, this scenario has no social benefits since the economic benefits generated are at the individual level and therefore cannot be used for the benefit of the community.

Comparing net billing and direct selling to the grid, net billing shows a profitability of approximately double that of direct selling. However, it should be noted that the benefits generated in net billing are individual, since they are deducted from the electricity bill, and no retained profits are obtained for the community.

It is important to highlight that municipalities with the lowest investment levels—typically those with the smallest energy demand, based on the assumption that only 14% of the population participates—are unable to achieve profitability from surplus energy sales under any scenario. Several factors contribute to this outcome. First, the net-billing scheme does not fully offset the cost of the residual energy that must still be purchased. Second, although all installations were designed under the same parameters, municipalities with higher energy demand benefit from significantly lower specific installation costs—up to an order of magnitude lower—due to economies of scale. Consequently, villages equipped with 3 kWp PV systems cannot achieve economic viability through surplus energy sales, as their installation costs are nearly double those of villages served by 60 kWp systems.

These findings reinforce the idea that greater collective aggregation enhances community benefits, as consolidating higher demand enables the deployment of larger-capacity installations at significantly more favorable unit costs. However, it is important to underscore the vulnerability of the direct selling scenario, where profitability is highly sensitive to external variables—most notably the price of energy sold directly to the grid, which is externally determined. Fluctuations in that parameter can ultimately dictate whether a village remains economically viable or not.

In terms of social impact, direct selling—Scenario 1A—results in a population growth of less than 2% after 28 years. The overall social impact is even lower under a net-billing scheme—Scenario 1B—since it considers just the profits individually, achieving no social impact.

The last option explored for the EC involves establishing it as an energy retailer—Scenario 1C—allowing it to sell surplus electricity directly. This scenario demonstrates remarkable economic profitability, with the profitability index reaching up to 2.72 in most villages. Lower profitability is observed in villages with smaller populations, lower demand, and consequently reduced surpluses—such as Bijuesca and Pozuel de Ariza. Nevertheless, even in these cases, the profitability index is greater than 1.

Regarding social impact, Scenario 1C results in population growth—measured in equivalent person-years—only in those villages with 60 kWp facilities; in other words, medium-sized villages. Interestingly, this scenario generates social benefits—when they exist—as early as year 5, in contrast to the selling and net-billing scenarios, where value creation typically begins around year 10. As for the case of the smaller villages, although the scenario shows profitability, this is not enough to generate equivalent person-years.

The results underscore that the current models, where ECs focus solely on managing surplus energy through direct selling or similar mechanisms, may offer some individual-level benefits but fail to generate the monetary value required to support collective outcomes or enable systemic change.

However, if we ask whether any of the scenarios support systemic transformation, the answer depends on the baseline. Considering that the annual rural depopulation rate is 0.1% according to [35], but in Spain is estimated at 0.7% [68], a reversal in trend would require a cumulative repopulation rate ranging from 2.8% to 19.6% by year 28. Managing surpluses through net billing does not lead to any collective social impact, and direct selling remains below 2.8%, except in two villages where it reaches 4%. Although, as mentioned, these figures are sensitive to the actual depopulation rate in the area, it seems reasonable to argue that Scenarios 1A and 1B —the most common in the energy communities—may help slow down depopulation, provided that surplus management is handled properly, as detailed. However, they do not appear to be sufficient to fundamentally reverse the overall trend.

Although none of the villages under these scenarios could individually drive a systemic transformation, our case study focuses on an energy community that brings together the 67 villages within the comarca. In other words, this case study possesses the administrative capacity to operate beyond the boundaries of each village, functioning as a unified entity. This structure greatly facilitates citizen-led management, as it eliminates the need to replicate the same organizational model 67 times and enables the benefits of aggregation—for instance, in negotiating offers.

The key question, however, is whether this unified approach can deliver benefits that exceed those achievable by each village acting independently, particularly when it comes to managing energy surpluses. Specifically, we explore whether under Scenario 1C—direct sales to third parties—the collective community (all 67 villages) can generate greater social benefits than the sum of what each village could achieve on its own.

The results clearly indicate that implementing a regional energy community to manage surpluses across numerous small villages produces a significant social impact. It achieves a population growth rate of 26.26%, which is notably higher than both the individual village rates and their combined total (14.09%). These levels are consistent with what would be expected from a systemic shift, even under the worst-case depopulation scenarios.

From an economic perspective, although the collective project (CERCA) does not surpass the profitability of most individual villages, it is nonetheless profitable under Scenario 1C. It outperforms the smaller villages in terms of return, making it possible for them to participate in and benefit from the broader social impact.

While this analysis does not differentiate between large and small villages, the energy community itself would be responsible for setting regional priorities. This governance model ensures that even the smallest towns can receive meaningful benefits—something that would be far less likely if surplus management was conducted individually at the village level.

4.2. Scenario 2—Battery Storage

The 28-year economic evaluation reveals that under Scenario 2A—battery storage with energy delivered at EUR 0.1468/kWh—smaller villages become unprofitable, while larger ones remained profitable. Scenario 2B shows the same trends as the previous scenario, with a minor increase; this is explained by the identical investment costs, but the electricity injected into the grid is sold at EUR 0.05/kWh above Scenario 2A.

Although we used a battery price of EUR 129/kWh, aligned with Bloomberg projections, real-world data from Calatayud installers suggests higher costs (approximately EUR 183/kWh). This indicates that Scenario 2A would not be a viable option if battery prices exceed the EUR 129/kWh assumption. Indeed, under these optimistic cost assumptions, battery storage remains less economically attractive compared to any of the energy-selling scenarios.

Furthermore, in the case of battery use, additional analysis is needed to assess the feasibility of operating with two charge/discharge cycles per day—potentially enabled by smaller storage capacities—as opposed to the single-cycle assumption used in this study. It is also important to highlight that the analysis prioritizes methodological simplicity, which may introduce certain limitations. Specifically, energy storage values are based on annual averages, potentially distorting the representation of daily storage dynamics, and consequently, the accuracy of the financial evaluation.

By contrast, Scenario 2C demonstrates economic viability in municipalities capable of deploying EV charging stations—benefiting only the larger villages. Alhama de Aragón and Ateca have 2 EV charging stations/each, while Calatayud can deploy 24 EV charging stations. Compared to Scenario 2A, where batteries are managed at a lower price point, this scenario proves to be more profitable.

From a social return perspective, Scenario 2A offers profitability from year 10 onward in the larger villages, while small ones do not show profitability. However, when the “battery” is managed as an EV charging point (Scenario 2C), there is a measurable increase in equivalent person-years from year 5 onwards in all towns where charging infrastructure is installed.

Moreover, although only the largest village approaches the threshold that might be considered indicative of a real systemic change, all participating towns show a consistently positive trend starting as early as year 5.

In any case, the results are more compelling in the energy-selling scenarios, such as Scenario 1C, where the community acts as an energy retailer.

Finally, and once again, we would like to highlight the value of the EC’s ability to operate at a regional scale, aggregating the surplus energy from all villages as a single unit. This implies that they can aggregate the energy of those villages that can participate in a scenario because they do not have enough surpluses. This case has been analyzed for Scenarios 2B and 2C.

Scenario 2B shows lower profitability when managing the energy surpluses with CERCA than most of the villages. The requested battery dimensions and operation and maintenance costs are higher due to the volume of energy to store.

In Scenario 2C, we make use of the surpluses from all the villages, including those located beyond the 10 km radius. This is possible because our specific EC, acting as an energy retailer, can allocate these surpluses to power EV chargers located in strategically chosen sites across the region. In this case, the surplus is all managed to deploy 31 EV charging stations with no remaining surplus, optimizing the design of the scenario. In the case of social impact, it is evident how this management case achieves significantly higher percentages of population growth than when considering the individual villages. The rate of 21.36% is also a value that can be considered a systemic change for the depopulation rate.

4.3. Scenario 3—Hydrogen Storage

Scenario 3A—the hydrogen refueling station—is only viable for energy outputs exceeding 467,200 kWh/year, and its applicability is further limited to towns located near highways, as was also the case in Scenario 2C. This restriction narrows its implementation to a single village, where both the techno-economic assessment and the social impact are positive. Calatayud could deploy two HRSs and sell the remaining surplus to the grid. The second and third villages in terms of surplus generation could also potentially access this scenario, provided that the SSR (self-sufficiency ratio threshold is adjusted to a lower value.

In case the EC could manage the energy surplus collectively operating as CERCA, it would not achieve profitability since the number of HRSs that could deploy is the same as the Calatayud village. In this case, the investment is higher, because the different facilities deployed in all the towns are considered.

Ultimately, all the towns demonstrate substantial profitability under Scenario 3B, with IRR figures exceeding 200% and the overall profitability index reaching approximately 19. This scenario stands out as the most economically advantageous across all municipalities. Scenario 3B offers very high profitability ratios, meaning that the return on investment is extremely high and very substantial profits are generated. At this point, an important question arises: Could villages of this size and nature realistically finance a project like Scenario 3B? Or is it simply a conceptual exercise with limited real-world applicability? To illustrate the scale of the challenge, it is worth noting that projects of this magnitude typically require an average energy demand of around 15,000 MWh per day. By contrast, the combined surplus generated by these villages amounts to just 11 MWh per day—a figure that falls significantly short of what would be needed to justify the deployment of such infrastructure.

From a social perspective, Scenario 3A, which involves the deployment of HRSs, shows a slight increase in population from year 10 onward in Calatayud, the only town capable of implementing HRSs. However, the population growth rate under Scenario 3A is lower than that observed in Scenarios 1A and 2C. Considering that the investment required for Scenario 3A is approximately five times higher, Scenarios 1A and 2C appear to be more favorable options when the objective is to maximize social return and impact.

On the other hand, the results indicate that all the villages begin generating benefits in Scenario 3B by year 5. Remarkably, population growth in this scenario surpasses 200% in most villages from year 5 onward, on average. The economic gains allow for an average investment equivalent to 20,118 person-years in year 5 across the towns analyzed. Moreover, this scenario is the only one showing positive outcomes for Pozuel de Ariza and Bijuesca from a social point of view.

Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that the required investment and technical complexity of Scenario 3B make its practical implementation in a local EC highly unlikely. In contrast, while Scenario 3A would require external financial support, it could become a viable option as hydrogen technology matures.

4.4. Global Assessment

From a social impact perspective, a critical question is how much initial investment is required to generate such an increment in population—understood in terms of full-time equivalent person-years—for each scenario and municipality. Can this value be quantified? The answer is affirmative (Table 5). It is worth noting that each full-time equivalent person-year is valued at EUR 14,000. Although the initial investment varies by scenario and municipality, it is assumed to remain constant throughout the social impact analysis. Consequently, evaluating this indicator across different time horizons is essential for capturing the evolution of long-term social returns and assessing the sustainability of each intervention.

Table 5.

Investment required for adhering a person in each village, scenario, and year analyzed (EUR/person-year equivalent) (only profitable scenarios are shown).

Overall, a clear trend is observed across all scenarios: the longer the time horizon, the lower the investment required to generate one full-time equivalent job. In other words, by year 28, the investment needed to achieve one equivalent person-year is significantly reduced compared to year 5.

However, from an operational and decision-making perspective, ECs should only consider those scenarios in which the investment required to generate one equivalent person-year is lower than its economic valuation (set at EUR 14,000). For example, although Scenario 1A—direct selling—is economically viable in certain municipalities (as shown in Table 3) and may even have a potential impact on population growth (Table 4), it does not constitute an effective strategy in terms of social return. This is because the investment required to generate one equivalent person-year exceeds the value of the person-year itself, thus failing to justify the investment from a social impact perspective.

By contrast, Scenario 1C presents a more favorable profile. From year 10 onward, the generated value per equivalent person-year remains below the EUR 14,000 threshold, meaning investment becomes socially viable. However, it is important to highlight that this strategy should be viewed as a medium-term approach, as it does not reach social viability by year 5—at which point the investment still exceeds the acceptable benchmark.

The two battery scenarios (2A and 2B) show socially viable results; however, the investment required to create one job is higher than the EUR 14,000 limit, so the investment is not socially justified, except for Calatayud, which surpasses the limit in year 20 and onward.

Furthermore, preliminary comparisons between Scenarios 2C and 3A—focused on EV charging points and HRSs, respectively—suggest that hydrogen infrastructure may yield comparable results in terms of equivalent person-years generated (see Table 3 and Table 4). However, as previously noted, Scenario 2C appears more feasible and realistic due to its lower initial investment requirements. This is further supported by the analysis in Table 5, which shows that Scenario 2C remains below the EUR 14,000 threshold from year 20 onward.

Finally, Scenario 3B emerges as the one with the highest potential in terms of both economic and social returns. It requires the lowest investment per equivalent person-year across all scenarios analyzed and offers substantial long-term benefits. Nevertheless, this scenario is also the least realistic due to its high entry barriers, both in terms of required knowledge and capital investment. These constraints may limit its scalability and applicability in the short to medium term.

Assuming that surplus energy is fully managed by CERCA, as a regional energy community, one could expect positive outcomes in terms of job creation. Since CERCA handles all surpluses collectively, it can enable scenarios that would otherwise be unviable for individual small towns, as illustrated in Table 4. However, a closer analysis of the cost per unit of population increase—measured as the value of each equivalent person-year—reveals that this value is higher than in villages that have demonstrated the ability to generate equivalent person-years under the different scenarios. The reasons for this are as follows:

- In Scenario 1C, the inclusion of surplus management from Bijuesca and Pozuel results in higher growth rates. However, these villages rely on more expensive small-scale facilities (3 kWp), which significantly increases the investment required. As a result, the cost per equivalent person-year becomes higher.

- In Scenarios 2A, 2B, and 2C, which incorporate battery storage, centralized management through CERCA leads to a greater number of batteries, higher overall capacity, and increased operation and maintenance costs. While this allows more villages to participate, it also raises the total investment required, making it less efficient in terms of cost per equivalent person-year compared to individual village-level approaches.

- In Scenario 3A, the deployment of hydrogen-related infrastructure (HRSs) is limited to the same scale as in Calatayud, since the total combined surplus from all towns is still insufficient to justify an additional installation. The remaining surplus is sold to the grid, and profitability is not achieved. This is due to the significantly higher investment involved, as it includes the PV infrastructure of all contributing villages—even though not all of the generated energy is ultimately utilized.

A more optimized management of CERCA’s data and operations could potentially lead to more favorable outcomes. This approach should be adopted if there is a shared commitment to inclusivity, ensuring that smaller villages are not left behind. However, it is important to acknowledge that under a collective surplus management model, larger villages may experience a reduced social impact compared to managing the surpluses independently.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusion of this research is that energy communities (ECs) have significant potential as instruments for rural revitalization. This study presents a clear and replicable methodological framework for integrating social impact as a central design criterion, rather than treating it as a secondary outcome. Our findings underscore the importance of aligning technical design choices with socially-driven objectives to enhance the contribution of ECs to territorial development.

Through the evaluation of eight technical scenarios, we measured social returns in terms of equivalent person-years. The analysis reveals that surplus energy management, while not sufficient to reverse rural depopulation trends in many cases, can contribute to slowing them—provided that social impact is embedded into the community’s governance and operational design.

Among the scenarios considered, net-billing schemes yield limited social benefits, as they generate individual rather than collective returns. In such models, self-consumers benefit disproportionately, and the absence of community-level profit significantly limits systemic impact. Even in economically viable surplus-selling models (direct selling), the social return remains marginal—affecting barely 1% of the population after 28 years—and the investment-to-impact ratio remains high.

In contrast, enabling an EC to operate as an energy retailer presents the highest potential in both economic and social terms. By selling electricity to third parties, ECs can achieve the strongest returns. However, this model entails considerable technical and regulatory complexity, often beyond the reach of citizen-led initiatives. Furthermore, it is subject to substantial uncertainties due to energy price volatility and the challenges of long-term forecasting.

As a more feasible and lower-risk alternative, particularly for medium-sized and larger municipalities, surplus management through the operation of electric vehicle (EV) charging stations emerges as a promising solution. This approach offers measurable social benefits, more predictable returns, and less technical burden.

Battery-based models, such as storage for self-consumption or battery-to-grid applications, are not financially viable in the smallest villages, and while potentially profitable in others, they face major barriers due to technical complexity. Conversely, more innovative approaches—including EV charging, hydrogen refueling stations (HRSs), and hydrogen-based fertilizer production—demonstrate higher long-term profitability. Among these, EV charging stands out for its earlier and more consistent social impact, while hydrogen-based fertilizer production offers the greatest potential for broad territorial revitalization, although it exceeds the technical and operational capacities of most communities.

This study also highlights the structural challenges faced by smaller villages. Higher electricity production costs limited surplus generation, and the inability to implement advanced technologies restrict participation in the most promising strategies. Nonetheless, this research suggests that stronger forms of local association—such as joint initiatives across multiple villages—may offer a viable path to achieving economies of scale and broader community impact. While smaller villages typically lack critical infrastructure, such as road access, they also exhibit greater potential for social cohesion and citizen engagement.

To this end, we explored a supra-structure model in which several villages are unified under a single EC that owns and manages all local facilities. This configuration reduces administrative burdens and resource requirements, and is particularly suited to rural, citizen-led contexts. However, the average cost per equivalent person in this shared model remains higher than in larger villages acting independently, raising the question of inter-village solidarity: Can stronger, more resource-rich municipalities support smaller ones to enable fair access to energy benefits and comparable electricity prices?

From an economic return point of view, it is difficult to find flexible scenarios that show a systematic change in the depopulation trend. However, this does not imply an absence of social impact. Indeed, there are scenarios in which the valorization of the surpluses can be associated with incipient changes in the trend. Each village needs to find a way to utilize this money for reverting to effective employment with strategies that are still to be defined and tested, which is still a “black box”. Some of the strategies could be financing wage costs for workers who settle in the village, and the maintenance of jobs associated with leisure facilities during the winter, etc.

Moreover, our study intends to quantify the social impact with respect to the motivation to establish an EC expressed by the neighbors of the region. As shown in Table 1, we found other social impacts in the literature that are not evaluated or quantified in this paper. The reason for this choice is that the neighbors did not look at these goals when setting up the EC.

Ultimately, our research emphasizes the need to evaluate rural energy projects not only through techno-economic lenses, but also by applying rigorous social impact metrics. In regions such as Calatayud (Spain), where depopulation threatens long-term viability, energy transition projects must prioritize local development and population retention. While our study is subject to limitations—including the reliance on aggregate energy data and estimated social indicators—it proposes a methodological foundation that can be replicated and adapted to other rural contexts. In conclusion, balancing profitability with social sustainability is essential for the success of ECs as engines of territorial revitalization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.C.; Formal analysis, L.N. and A.B.C.; Funding acquisition, A.B.C.; Investigation, C.S.-C. and A.B.C.; Methodology, A.B.C.; Project administration, A.B.C.; Resources, A.B.C.; Supervision, L.N. and A.B.C.; Validation, L.N. and A.B.C.; Visualization, C.S.-C.; Writing—original draft, C.S.-C.; Writing—review and editing, C.S.-C., L.N., and A.B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received funds from the European Union’s LIFE program under grant agreement No: 101076395. Funding from the Comunidad de Madrid through the TEC-2024/ECO-72 Program (CM-FOREVERPV) is also gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASU | Air separation unit |

| CEC | Citizen Energy Community |

| EC | Energy community |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| HRSs | Hydrogen refueling stations |

| IRR | Internal rate of return |

| kWp | Kilowatt peak |

| LCOH | Levelized cost of hydrogen |

| Li-ion | Lithium-ion |

| MWh | Megawatt hour |

| N2 | Nitrogen |

| Na-S | Sodium-sulfur |

| Ni-Cd | Nickel-cadmium |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| NPV | Net present value |

| Pb-A | Lead-acid |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| REC | Renewable Energy Community |

| STH | Solar-to-hydrogen |

References

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2019/ 944 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity and Amending Directive 2012/27/EU; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Council of European. Regulators Regulatory Aspects of Self-Consumption and Energy Communities; Council of European: Strasbourg, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Biresselioglu, M.E.; Limoncuoglu, S.A.; Demir, M.H.; Reichl, J.; Burgstaller, K.; Sciullo, A.; Ferrero, E. Legal Provisions and Market Conditions for Energy Communities in Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Turkey: A Comparative Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Prol, J.; Steininger, K.W. Photovoltaic Self-Consumption Is Now Profitable in Spain: Effects of the New Regulation on Prosumers’ Internal Rate of Return. Energy Policy 2020, 146, 111793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasí-Crespo, D.; Roldán-Blay, C.; Escrivá-Escrivá, G.; Roldán-Porta, C. Evaluation of the Spanish Regulation on Self-Consumption Photovoltaic Installations. A Case Study Based on a Rural Municipality in Spain. Renew. Energy 2023, 204, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Ley 24/2013, de 26 de Diciembre, Del Sector Eléctrico; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto 2019/1997, de 26 de Diciembre, Por El Que Se Organiza Regula El Mercado de Producción de Energía Eléctrica; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pellow, M.A.; Emmott, C.J.M.; Barnhart, C.J.; Benson, S.M. Hydrogen or Batteries for Grid Storage? A Net Energy Analysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1938–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wei, Y.L.; Cao, P.F.; Lin, M.C. Energy Storage System: Current Studies on Batteries and Power Condition System. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3091–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani-Sanij, A.R.; Tharumalingam, E.; Dusseault, M.B.; Fraser, R. Study of Energy Storage Systems and Environmental Challenges of Batteries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Castillo, C.; Heleno, M.; Victoria, M. Self-Consumption for Energy Communities in Spain: A Regional Analysis under the New Legal Framework. Energy Policy 2021, 150, 112144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto 244/2019; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- May, G.J.; Davidson, A.; Monahov, B. Lead Batteries for Utility Energy Storage: A Review. J. Energy Storage 2018, 15, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsiborács, H.; Hegedűsné Baranyai, N.; Vincze, A.; Háber, I.; Pintér, G. Economic and Technical Aspects of Flexible Storage Photovoltaic Systems in Europe. Energies 2018, 11, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BloombergNEF Lithium-Ion Battery Pack Prices Hit Record Low of $139/KWh. Available online: https://about.bnef.com/blog/lithium-ion-battery-pack-prices-hit-record-low-of-139-kwh/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Berrada, A.; Laasmi, M.A. Technical-Economic and Socio-Political Assessment of Hydrogen Production from Solar Energy. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartiainen, E.; Breyer, C.; Moser, D.; Román Medina, E.; Busto, C.; Masson, G.; Bosch, E.; Jäger-Waldau, A. True Cost of Solar Hydrogen. Sol. RRL 2022, 6, 2100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaik, K.; Werle, S. Solar and Wind Energy in Poland as Power Sources for Electrolysis Process—A Review of Studies and Experimental Methodology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 11628–11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Ghoshal, S.K. Hydrogen the Future Transportation Fuel: From Production to Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brey, J.J. Use of Hydrogen as a Seasonal Energy Storage System to Manage Renewable Power Deployment in Spain by 2030. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 17447–17457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA District Heat Production by Fuel, 2010–2020 and in the Net Zero Scenario, 2030. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/district-heat-production-by-fuel-2010-2020-and-in-the-net-zero-scenario-2030 (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Jang, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, D.; Han, W.B.; Kang, S. Techno-Economic Analysis and Monte Carlo Simulation of Green Hydrogen Production Technology through Various Water Electrolysis Technologies. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 258, 115499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Siefer, G.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Bothe, K.; Hao, X. Solar Cell Efficiency Tables (Version 61). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2023, 31, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, T.L.; Kelly, N.A. Predicting Efficiency of Solar Powered Hydrogen Generation Using Photovoltaic-Electrolysis Devices. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astakhov, O.; Smirnov, V.; Rau, U.; Merdzhanova, T. Prediction of Limits of Solar-to-Hydrogen Efficiency from Polarization Curves of the Electrochemical Cells. Sol. RRL 2022, 6, 2100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Seitz, L.C.; Benck, J.D.; Huo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ng, J.W.D.; Bilir, T.; Harris, J.S.; Jaramillo, T.F. Solar Water Splitting by Photovoltaic-Electrolysis with a Solar-to-Hydrogen Efficiency over 30%. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaner, M.R.; Atwater, H.A.; Lewis, N.S.; McFarland, E.W. A Comparative Technoeconomic Analysis of Renewable Hydrogen Production Using Solar Energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2354–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Making the Breakthrough: Green Hydrogen Policies and Technology Costs; International Renewable Energy Agency: Masdar City, United Arab Emirates, 2021; ISBN 978-92-9260-314-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, O.; Rehme, J.; Cerin, P. Levelized Cost of Hydrogen for Refueling Stations with Solar PV and Wind in Sweden: On-Grid or off-Grid? Energy 2022, 241, 122906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). The Future of Hydrogen; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lao, J.; Song, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J. Reducing Atmospheric Pollutant and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Heavy Duty Trucks by Substituting Diesel with Hydrogen in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei-Shandong Region, China. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 18137–18152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Ammonia Technology Roadmap Towards More Sustainable Nitrogen Fertiliser Production; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Urban-Rural Europe-Population Projections. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Urban-rural_Europe_-_population_projections#SE_MAIN_TT (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Predominantly Rural Regions Experience Depopulation. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230117-2 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Fedorova, E.; Pongrácz, E. Cumulative Social Effect Assessment Framework to Evaluate the Accumulation of Social Sustainability Benefits of Regional Bioenergy Value Chains. Renew. Energy 2019, 131, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berka, A.L.; Creamer, E. Taking Stock of the Local Impacts of Community Owned Renewable Energy: A Review and Research Agenda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3400–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, M.L.J.; Wicke, B.; Faaij, A.P.C.; van der Hilst, F. Projecting Socio-Economic Impacts of Bioenergy: Current Status and Limitations of Ex-Ante Quantification Methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 115, 109352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basset, F. The Evaluation of Social Farming through Social Return on Investment: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsikopoulos, D.; Vrettos, C. The Social Impact of Energy Communities in Greece; Heinrich Böll Foundation Greece and ELECTRA Energy Cooperative: Athens, Greece, 2023; ISBN 9786185580186. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S.; Brown, D.; Cárdenas Álvarez, J.P.; Chitchyan, R.; Fell, M.J.; Hahnel, U.J.J.; Hojckova, K.; Johnson, C.; Klein, L.; Montakhabi, M.; et al. Social and Economic Value in Emerging Decentralized Energy Business Models: A Critical Review. Energies 2021, 14, 7864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal, A.B.; Narvarte, L.; Victoria, M.; Fialho, L.; Zhang, Z.; Sanz-Cuadrado, C.; Bokalič, M. Igniting University Communities: Building Strategies That Empower an Energy Transition through Solar Energy Communities. Sol. RRL 2023, 7, 2300498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal, A.B.; Sanz-Cuadrado, C.; Zhang, Z.; Victoria, M.; Fialho, L.; Cavaco, A.; Bokalič, M.; Narvarte, L. Delving into the Modeling and Operation of Energy Communities as Epicenters for Systemic Transformations. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JALON. Available online: https://jalon-ce.eu/es/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Mapa de La Comarca de Comunidad de Calatayud. Zaragoza Aragoneria. Available online: https://www.aragoneria.com/mapas/comarcas/comunidaddecalatayud.php (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- DATADIS. Available online: https://datadis.es/queries (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Red Eléctrica de España (REE). Autoconsumo en los Hogares; Red Eléctrica de España: Alcobendas, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS). Available online: https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Red Eléctrica Precio Mercado SPOT Diario. Available online: https://www.esios.ree.es/es/analisis/600?vis=1&start_date=01-01-2023T00%3A00&end_date=31-12-2023T23%3A55&compare_start_date=31-12-2022&groupby=day (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Red Eléctrica Término de Facturación de Energía Activa Del PVPC 2.0TD. Available online: https://www.esios.ree.es/es/pvpc?date=22-10-2022 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Red Eléctrica Precio de La Energía Excedentaria Del Autoconsumo Para El Mecanismo de Compensación Simplificada (PVPC). Available online: https://www.esios.ree.es/es/analisis/1739?vis=1&start_date=01-01-2023T00%3A00&end_date=31-12-2023T23%3A55&compare_start_date=31-12-2022&groupby=day (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Ley 38/1992, de 28 de Diciembre, de Impuestos Especiales; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto Legislativo 1175/1990, de 28 de Septiembre, Por El Que Aprueban Las Tarifas y La Instrucción Del Impuesto Sobre Económicas; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de Aragón Tasa 14. Por Servicios En Materia de Ordenación de Actividades Industriales, Energéticas, Metrológicas, Mineras y Comerciales. Modelo 514. Apartado 5. Tarifa 11.1. Available online: https://aplicaciones.aragon.es/alq/alq?dga_accion_app=buscar_tarifas&multiple=N&sri_tasa=14&sri_modelo=514&sri_modelo_id=1 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- European Comission Electric Vehicle Recharging Prices. Available online: https://alternative-fuels-observatory.ec.europa.eu/consumer-portal/electric-vehicle-recharging-prices (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- CharBox Cargador Para Empresas Con Pedestal EBusiness E-30. Available online: https://www.cargadorcocheelectrico.net/cargador-empresas-pedestal-ebusiness-e-30/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- EDP Energía El Cuidado de Un Cargador Eléctrico. Available online: https://www.edpenergia.es/es/blog/movilidad-sostenible/cuidado-cargador-electrico/#:~:text=Mantenimiento%20de%20cargadores%20de%20veh%C3%ADculos,unos%20ocho%20o%20diez%20a%C3%B1os (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Cano, J. Madrid Abre Su Propia “Hidrogenera”; El Coche de Hidrógeno, Más Cerca. El Español 2021. Available online: https://www.elespanol.com/motor/20210128/madrid-abre-primera-hidrogenera-coche-hidrogeno-cerca/554446376_0.html (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Griñán, G.G. ¿Dónde Podre Llenar Mi Vehículo de Hidrógeno y a Qué Precio? 2023. Available online: https://openroom.fundacionrepsol.com/es/contenidos/donde-llenar-vehiculo-hidrogeno-precio/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).