Consumer Preferences for Wood-Pellet-Based Green Pricing Programs in the Eastern United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Methods

3.1. Econometric Analysis

3.2. Attributes and Corresponding Levels

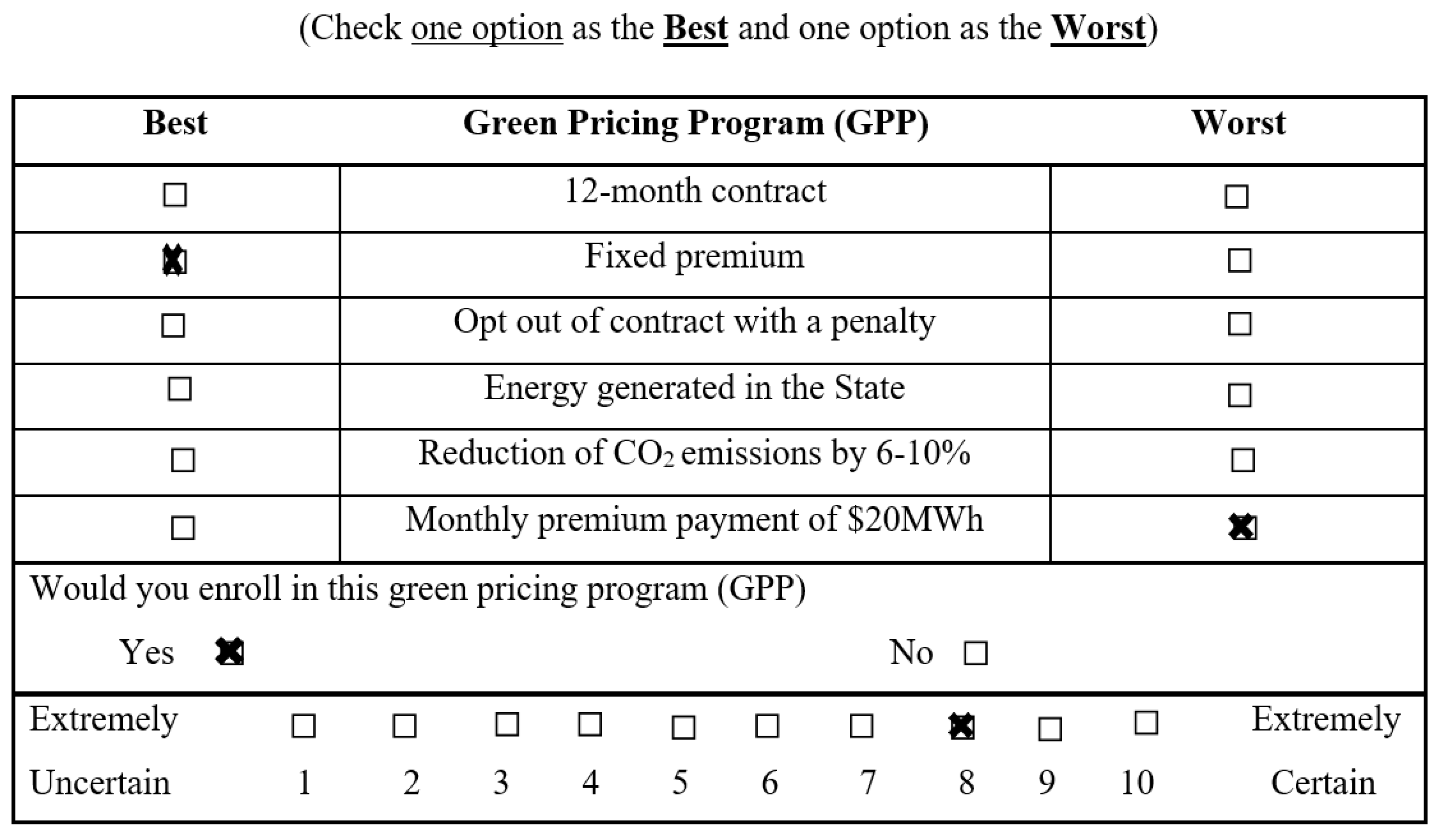

3.3. Data Collection

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. State Socio-Demographic Variables

4.2. Introductory Questions

4.3. Paired Estimates for BWS

4.4. Estimation of Binary Choice Task

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roni, M.S.; Chowdhury, S.; Mamun, S.; Marufuzzaman, M.; Lein, W.; Johnson, S. Biomass co-firing technology with policies, challenges, and opportunities: A global review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIA. 2021. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=427&t=3 (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Slade, R.; Bauen, A.; Gross, R. Global bioenergy resources. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellets Fuel Institute (PFI). 2021. Available online: https://www.pelletheat.org/what-are-pellets- (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Garcia, R.; Gil, M.V.; Rubiera, F.; Pevida, C. Pelletization of wood and alternative residual biomass blends for producing industrial quality pellets. Fuel 2019, 251, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pellet Council (EPC). A European Success Story. Available online: https://epc.bioenergyeurope.org/about-pellets/pellets-basics/wood-pellets-a-european-success-story/ (accessed on 24 September 2019).

- U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC). International Trade in Wood Pellets: Current Trends and Future Prospects. 2018. Available online: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/executive_briefings/wood_pellets_ebot_final.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- EIA. 2021. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/steo/report/renew_co2.php (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Mei, B.; Wetzstein, M. Burning wood pellets for US electricity generation? A regime switching analysis. Energy Econ. 2017, 65, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerndt, M.E.; Aguilar, F.X.; Skog, K. Resource potential for renewable energy generation from co-firing of woody biomass with coal in the Northern U.S. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 59, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roni, M.S.; Ekisioglu, S.D.; Searcy, E.; Jha, K. A supply chain network design model for biomass co-firing in coal-fired power plants. Transp. Res. Part E 2014, 61, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.M.; Kooten, G.C. Economics of co-firing coal and biomass: An application to Western Canada. Energy Econ. 2015, 48, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, E.; Ojumu, G.; Adozssi, E. Economic impact of wood pellet co-firing in South and West Alabama. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2013, 17, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Butler, J.; Leon, M.A. Biomass co-firing options on the emission reduction and electricity generation costs in coal-fired power plants. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Eksioglu, S.D.; Khademi, A. Analyzing Tax Incentives for Producing Renewable Energy by Biomass Cofiring. IISE Trans. 2017, 50, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, B.; Golden, J.S. Life cycle assessment of co-firing coal and wood pellets in the Southeastern United States. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, A.H.; Ha-Duong, M.; Tran, H.A. Economics of co-firing rice straw in coal power plants in Vietnam. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.M.; Venn, T.J.; Anderson, N.M. Social preferences toward energy generation with woody biomass from public forests in Montana, USA. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 73, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susaeta, A.; Lal, P.; Alavalapati, J.; Mercer, E. Random preferences towards bioenergy environmental externalities: A case study of woody biomass-based electricity in the Southern United States. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Lautala, P. Optimal Level of Woody Biomass Co-Firing with Coal Power Plant Considering Advanced Feedstock Logistics System. Agriculture 2018, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for the New Energy Economy, Colorado State University. Green Power Pricing Programs. March 2017. Available online: https://spotforcleanenergy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/31f410651541de4633f9bb77ad42f0ca.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Bae, J.H.; Rishi, M. Increasing consumer participation rates for green pricing programs: A choice experiment for South Korea. Energy Econ. 2018, 74, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Green Power Partnership—Green Power Pricing; 2019. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/greenpower (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Bae, J.H.; Rishi, M.; Li, D. Consumer preferences for a green certificate program in South Korea. Energy 2011, 230, 120726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, E.; Heeter, J.; Sauer, J. Status and Trends in the U.S. Voluntary Green Power Market: 2017 Data; NREL/TP-6A20-72204; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy19osti/72204.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Green Power markets. 2019. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/green-power-markets/green-power-pricing#two (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- Borchers, A.M.; Duke, J.M.; Parsons, G.R. Does willingness to pay for green energy differ by source? Energy Policy 2007, 35, 3327–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, K.; Persson, L. Windfarms-Where and how to place them? A choice experiment approach to measure consumer preferences for characteristics of wind farm establishments in Sweden. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 105, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koto, P.S.; Yiridoe, E.K. Expected willingness to pay for wind energy in Atlantic Canada. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpan, L.M.; Xu, X.; Raney, A.A.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z. Politics, values, and morals: Assessing consumer responses to the framing of residential renewable energy in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 46, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, L.; O’Shaughnessy, E.; Heeter, J.; Mills, S.; DeCicco, J.M. Will consumers really pay for green electricity? Comparing stated and revealed preferences for residential programs in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Physical Society (APS). Integrating Renewable Electricity on the Grid—A Report by the APS Panel on Public Affairs. 2015. Available online: https://www.aps.org/policy/reports/popa-reports/upload/integratingelec.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Herbes, C.; Friege, C.; Baldo, D.; Mueller, K.M. Willingness to pay lip service? Applying a neuroscience-based method to WTP for green electricity. Energy Policy 2015, 87, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbes, C.; Ramme, L. Online marketing of green electricity in Germany—A content analysis of providers’ websites. Energy Policy 2014, 66, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluoch, S.; Lal, P.; Wolde, B.; Susaeta, A.; Soto, J.R.; Smith, M.; Adams, D.C. Public Preferences for Longleaf Pine Restoration Programs in the Southeastern United States. For. Sci. 2021, 67, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Lal, P.; Oluoch, S.; Vedwan, N.; Smith, A. Valuation of sustainable attributes of hard apple cider: A best-worst choice approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.R.; Adams, D.C.; Escobedo, F.J. Landowner attitudes and willingness to accept compensation from forest carbon offsets: Application of best-worst choice modeling in Florida USA. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 63, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.R.; Escobedo, F.J.; Khachatryan, H.; Adams, D.C. Consumer demand for urban forest ecosystems services and disservices: Examining trade-offs using choice experiments and best-worst scaling. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, S.J.; Escobedo, F.J.; Soto, J.R. Recognizing the insurance value of resilience: Evidence from a forest restoration policy in the southeastern US. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, T.N.; Louviere, J.J.; Peters, T.J.; Coast, J. Best-worst scaling: What it can do for health care research and how to do it. J. Health Econ. 2007, 26, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP). Biomass Cofiring in Coal-Fired Boilers. 2019. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy04osti/33811.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Morrison, M.; Brown, T.C. Testing the effectiveness of certainty scales, cheap talk, and dissonance-minimization in reducing hypothetical bias in contigent valuation studies. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2009, 44, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, A.; Hanley, N.; Wright, R. Valuing the attributes of renewable energy investments. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1004–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, A.; Colombo, S.; Hanley, N. Rural versus urban preferences for renewable energy developments. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, F.; Lotz, S. Domestic uptake of green energy promoted by opt-out tariffs. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeznig, J.; Henzie, S.L.; Wustenhagen, R. Whatever the customer wants, the customer gets? Exploring the gap between consumer preferences and default electricity products in Germany. Energy Policy 2013, 53, 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Oluoch, S.; Lal, P.; Bevacqua, A.; Wolde, B. Consumer willingness to pay for community solar in New Jersey. Electr. J. 2021, 34, 107006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagebiel, J.; Muller, J.R.; Rommel, K. Are consumers willing to pay more for electricity from cooperatives? Results from an online Choice Experiment in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Phelps, G.; Tortora, R.; Swift, K.; Kohrell, J.; Berck, J.; Messer, B.L. Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the Internet. Soc. Sci. Res. 2009, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. Census Data. 2019. Available online: www.census.gov/data.html (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Adams, D.C.; Bwenge, A.N.; Lee, D.J.; Larkin, S.L.; Alavalapati, J.R.R. Public preferences for controlling upland invasive plants in state parks: Application of a choice model. For. Policy Econ. 2011, 13, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). State Renewable Portfolio Standards. 2022. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/energy/state-renewable-portfolio-standards-and-goals (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Gilligan, C. US News and World Report: 10 States That Produce the Most Renewable Energy. 2022. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/slideshows/these-states-use-the-most-renewable-energy (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Bird, L.; Swezey, B.; National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Green Power Marketing in the United States: A Status Report (Eight Edition). Technical Report NREL/TP-620-38994. 2005. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy06osti/38994.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Flynn, T.N.; Louviere, J.J.; Peters, T.J.; Coast, J. Estimating preferences for a dermatology consultation using best-worst scaling: Comparison of various methods of analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gai, D.H.B.; Shittu, E.; Attanasio, D.; Weigelt, C.; LeBlanc, S.; Dehghanian, P.; Skylar, S. Examining community solar programs to understand accessibility and investment: Evidence from the U.S. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112600. [Google Scholar]

- Stigka, E.K.; Paravantis, J.A.; Mihalakakou, G.K. Social acceptance of renewable sources: A review of contingent valuation applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, Y. Market segmentation and willingness to pay for green electricity among urban residents in China: The case of Jiangsu Province. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamma, K.; Mai, R.; Cometta, C.; Loock, M. Engaging customers in demand response programs: The role of reward and punishment in customer adoption in Switzerland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 74, 101927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, J.K.; Geiger, N. Policy attributes, perceived impacts, and climate change policy preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 77, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/380641/leading-us-states-by-coal-production/ (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Drake, B.; Smart, J.C.; Termansen, M.; Hubacek, K. Public preferences for production of local and global ecosystem services. Reg Env. Chang. 2013, 13, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.C.; Cherry, T.L. Willingness to pay for a Green Energy program: A comparison of ex-ante and ex-post hypothetical bias mitigation approaches. Resour. Energy Econ. 2007, 29, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Green Energy Attributes | Description | Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Length of contract (LC) | The contract length for the energy provision service that involves supply of electricity and a renewable energy certificate (REC). | 6 months (6 M) 12 months (12 M) 24 months (24 M) * |

| Variability of payments (VP) | Variability of payments due to market factors can be accounted for by RECs that have a fixed premium or fluctuating premium. | Fixed premium (FP) Fluctuating premium ± 5% (F5) Fluctuating premium ± 10% (F10) * |

| Flexibility of contract (FC) | The electricity consumer has the option to opt out of the contract with or without a penalty. | Opt out of contract with a penalty (PEN) * Opt out of contract without a penalty (NOPEN) |

| Location of energy generation (LG) | The location of the energy provision service can be In State or out of state. | In State (IN-STATE) Out of state (OUT-STATE) * |

| Reduction in CO2 Emissions (RC) | Co-firing conversion plants that incorporate wood pellets can result in local reduction of CO2 emissions. | 1–5% (LOW) * 6–10% (MED) 11–20% (HIGH) |

| Green Pricing Premium Payment (GP) | The payment vehicle in the form of a biomass renewable energy certificate (REC) added to the monthly electricity bill. With a charge for every Megawatt hour of electricity supplied to the consumer. | USD 10/MWh USD 20/MWh USD 30/MWh USD 40/MWh * |

| Category | Sample Population (n = 2000) | US Census a |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 39.50 | 39.62 |

| Household size (people) | 2.64 | 2.58 |

| Education attainment (high school or higher %) | 97.35 | 89.62 |

| Female (%) | 50.00 | 51.20 |

| Median household income (USD USD) | 74,999.50 | 69,902.40 |

| Monthly power bill (USD USD) | 123.32 | 122.15 |

| Employment rate (%) | 52.45 | 58.88 |

| Alabama | New Jersey | New York | Pennsylvania | Virginia | Pooled States | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff (Std Dev) | ||||||

| Attribute impacts | ||||||

| LC | 0.139 (0.093) | −0.131 (0.094) | 0.424 (0.095) *** | 0.299 (0.095) ** | 0.341 (0.095) *** | 0.213 (0.042) *** |

| VP | 0.328 (0.094) *** | 0.071 (0.095) | 0.478 (0.095) *** | 0.324 (0.095) *** | 0.519 (0.096) *** | 0.342 (0.042) *** |

| FC | 0.238 (0.086) ** | 0.063 (0.087) | 0.279 (0.087) *** | 0.202 (0.087) ** | 0.403 (0.087) *** | 0.235 (0.039) *** |

| LG | 0.348 (0.087) *** | 0.350 (0.089) *** | 0.534 (0.088) *** | 0.429 (0.089) *** | 0.556 (0.090) *** | 0.440 (0.040) *** |

| RC | 0.970 (0.094) *** | 1.215 (0.096) *** | 1.186 (0.094) *** | 1.375 (0.097) *** | 1.544 (0.097) *** | 1.249 (0.043) *** |

| Level scale values | ||||||

| M6 | −0.559 (0.091) *** | −0.516 (0.092) *** | −0.270 (0.091) *** | −0.656 (0.093) *** | −0.577 (0.093) *** | −0.510 (0.041) *** |

| M12 | 0.308 (0.091) *** | 0.448 (0.092) *** | 0.338 (0.091) *** | 0.477 (0.093) *** | 0.449 (0.093) *** | 0.400 (0.041) *** |

| FP | −0.875 (0.088) *** | −1.075 (0.090) *** | −0.859 (0.089) *** | −1.376 (0.090) *** | −1.110 (0.090) *** | −1.051 (0.040) *** |

| F5 | 0.187 (0.088) *** | 0.319 (0.089) *** | 0.101 (0.089) | 0.359 (0.089) *** | 0.273 (0.090) ** | 0.247 (0.040) *** |

| NOPEN | 1.081 (0.074) *** | 1.214 (0.076) *** | 0.967 (0.074) *** | 1.555 (0.076) *** | 1.310 (0.075) *** | 1.216 (0.034) *** |

| INSTATE | 0.761 (0.075) *** | 0.527 (0.077) *** | 0.508 (0.074) *** | 0.814 (0.077) *** | 0.704 (0.077) *** | 0.659 (0.034) *** |

| MED | 0.450 (0.090) *** | 0.292 (0.090) *** | 0.325 (0.089) *** | 0.398 (0.092) *** | 0.299 (0.091) *** | 0.346 (0.040) *** |

| HIGH | 0.541 (0.091) *** | 0.677 (0.091) *** | 0.427 (0.089) *** | 0.691 (0.092) *** | 0.551 (0.091) *** | 0.574 (0.041) *** |

| USD 10/MWH | −1.530 (0.104) *** | −1.346 (0.106) *** | −1.345 (0.105) *** | −1.683 (0.107) *** | −1.714 (0.106) *** | −1.512 (0.047) *** |

| USD 20/MWH | 1.046 (0.104) *** | 1.098 (0.106) *** | 1.057 (0.105) *** | 1.355 (0.107) *** | 1.413 (0.108) *** | −1.183 (0.047) *** |

| USD 30/MWH | 0.456 (0.104) *** | 0.453 (0.107) *** | 0.587 (0.104) *** | 0.601 (0.107) *** | 0.633 (0.106) *** | 0.541 (0.047) *** |

| No. of observations | 72,000 | 72,000 | 71,970 | 72,000 | 71,970 | 359,910 |

| No. of respondents | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 2000 |

| Log likelihood | −7421.826 | −7421.826 | −7711.252 | −7355.097 | −7421.699 | −37,670.374 |

| Binary Logit | Calibrated Model (Certainty Scale 7 Cut Off) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute Level | Parameter Estimates | WTP (USD) | Parameter Estimates | WTP (USD) |

| M6 | 0.230 (0.042) *** | 17.13 | 0.341 (0.050) *** | 77.28 |

| M12 | 0.097 (0.044) ** | 7.25 | 0.306 (0.053) *** | 69.31 |

| FP | 0.122 (0.045) ** | 9.06 | 0.165 (0.054) ** | 37.37 |

| F5 | 0.077 (0.045) * | 5.74 | 0.112 (0.054) ** | 25.38 |

| NOPEN | 0.084 (0.036) ** | 6.28 | 0.151 (0.042) *** | 34.30 |

| INSTATE | 0.069 (0.036) * | 5.10 | 0.238 (0.042) *** | 54.03 |

| MED | 0.116 (0.045) ** | 8.61 | 0.273 (0.055) *** | 61.92 |

| HIGH | 0.209 (0.043) *** | 15.55 | 0.447 (0.506) *** | 101.33 |

| GP | −0.013 (0.001) *** | −0.004 (0.001) ** | ||

| No. of respondents | 2000 | |||

| No. of Observations | 23,994 | |||

| Log likelihood | −8237.32 | −12,016.41 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oluoch, S.; Lal, P.; Susaeta, A.; Smith, M.; Wolde, B. Consumer Preferences for Wood-Pellet-Based Green Pricing Programs in the Eastern United States. Energies 2024, 17, 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17081821

Oluoch S, Lal P, Susaeta A, Smith M, Wolde B. Consumer Preferences for Wood-Pellet-Based Green Pricing Programs in the Eastern United States. Energies. 2024; 17(8):1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17081821

Chicago/Turabian StyleOluoch, Sydney, Pankaj Lal, Andres Susaeta, Meghann Smith, and Bernabas Wolde. 2024. "Consumer Preferences for Wood-Pellet-Based Green Pricing Programs in the Eastern United States" Energies 17, no. 8: 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17081821

APA StyleOluoch, S., Lal, P., Susaeta, A., Smith, M., & Wolde, B. (2024). Consumer Preferences for Wood-Pellet-Based Green Pricing Programs in the Eastern United States. Energies, 17(8), 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17081821