Influence of Wind Turbines as Dominants in the Landscape on the Acceptance of the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Public Acceptance of RES

1.2. Impact of Wind Turbines on the Landscape

2. Materials and Methods

- n—sample size

- N—population size

- Z—coefficient depending on the confidence level adopted, with a confidence level of 0.95

- d—prediction error is assumed to be ±5% (0.05)

- X2—chi-square test

- i—number of lines

- j—number of columns

- Oij—the actual frequency in the i-th row of the j-th column

- Eij—the predicted frequency in the i-th row of the j-th column

3. Results

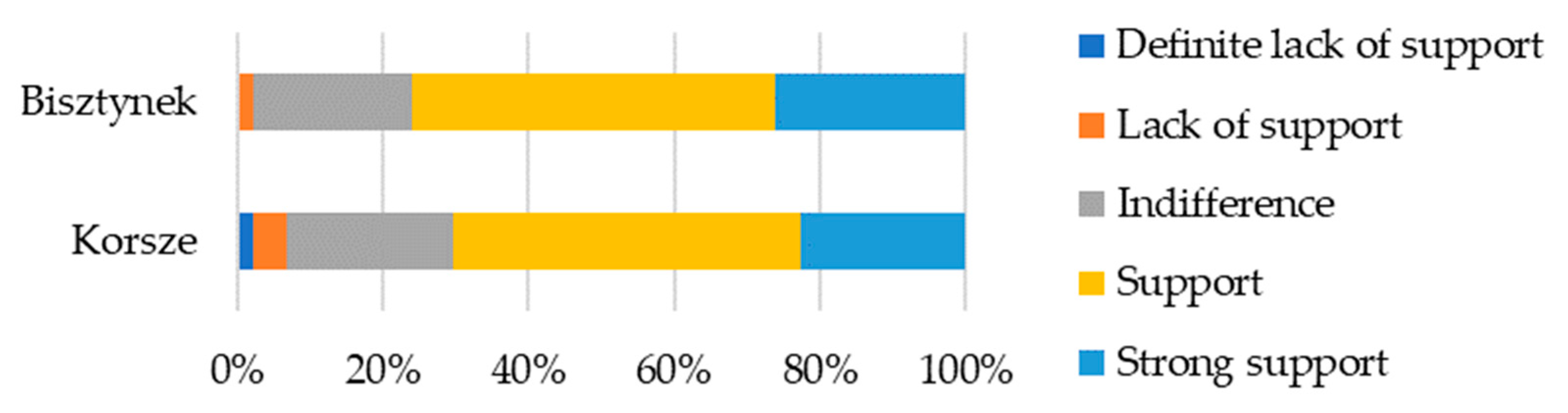

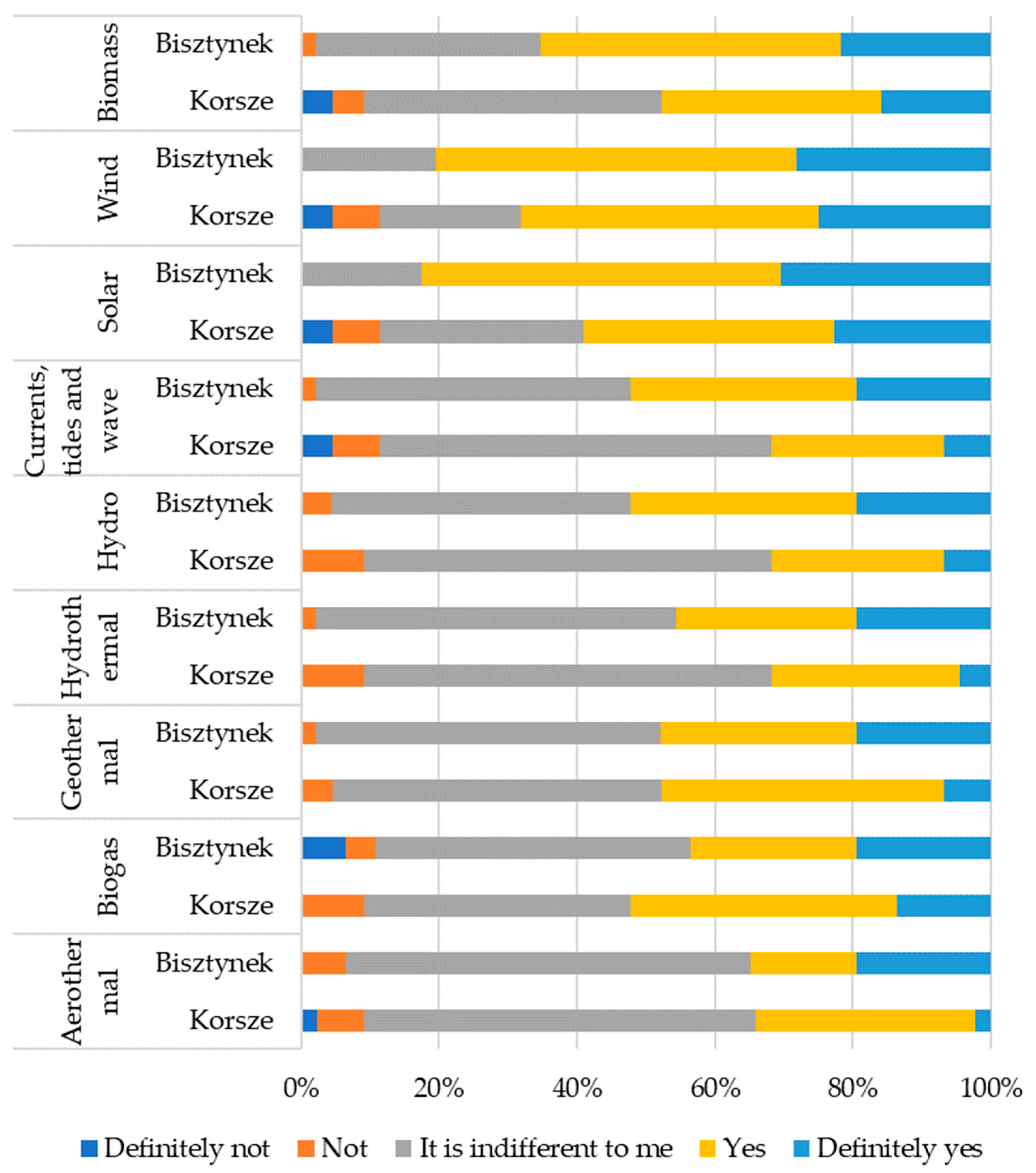

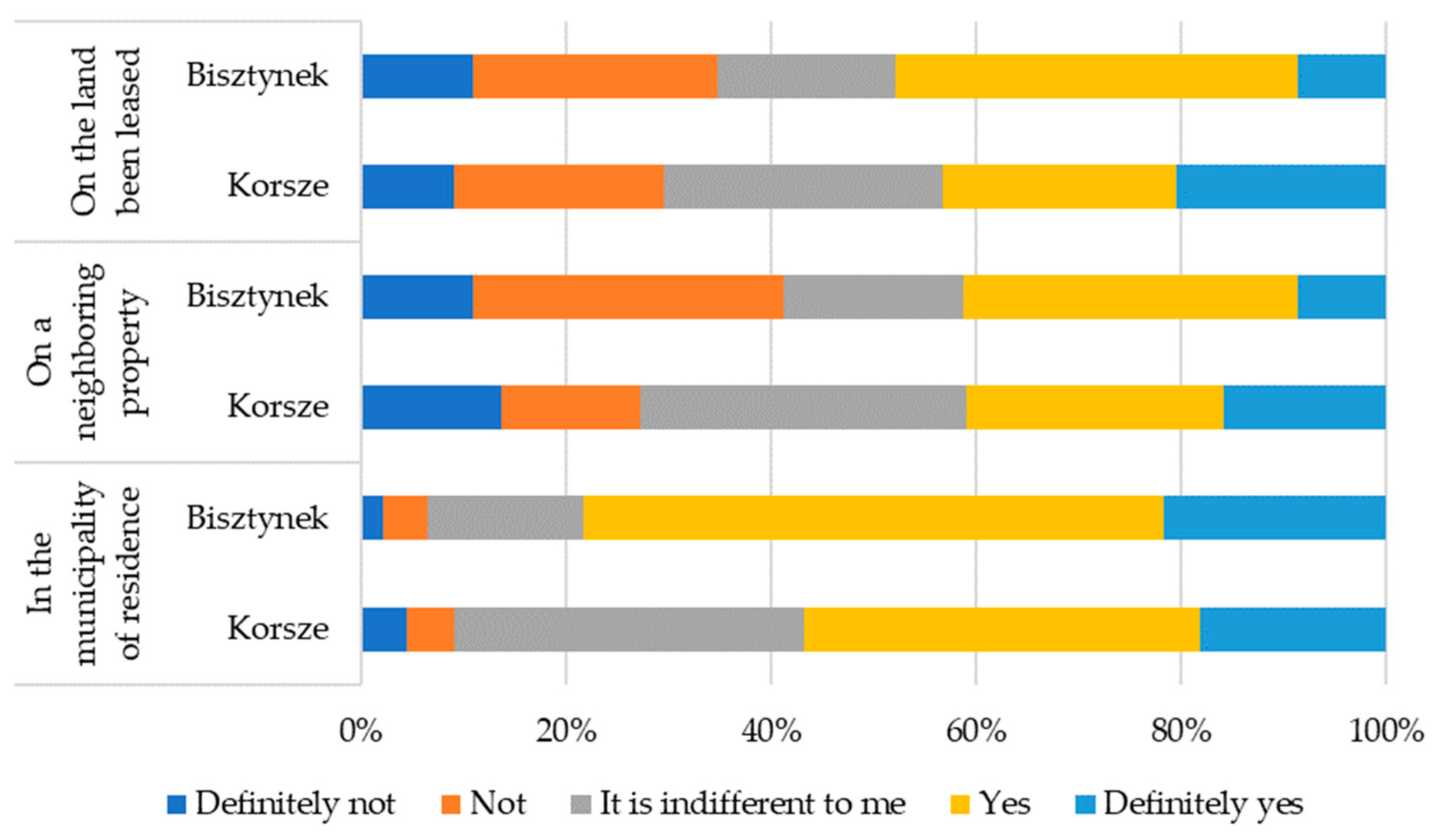

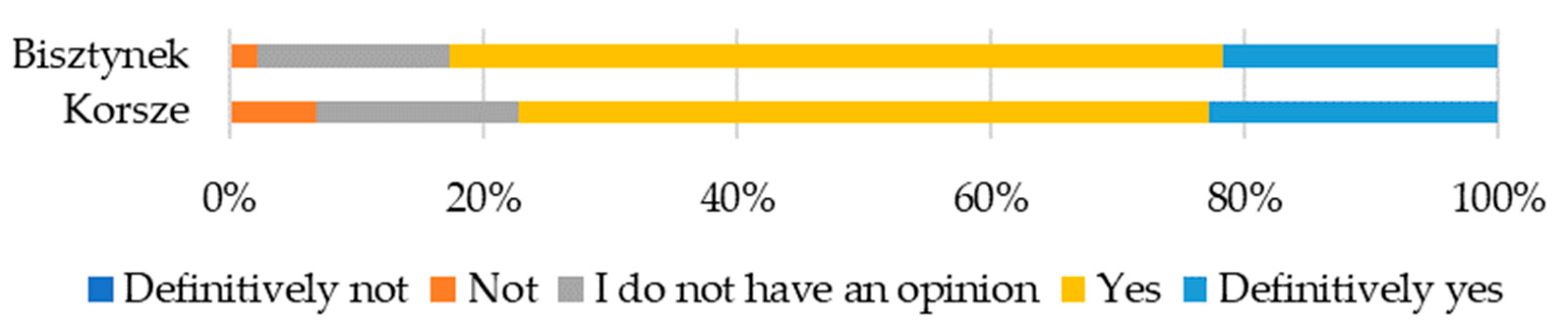

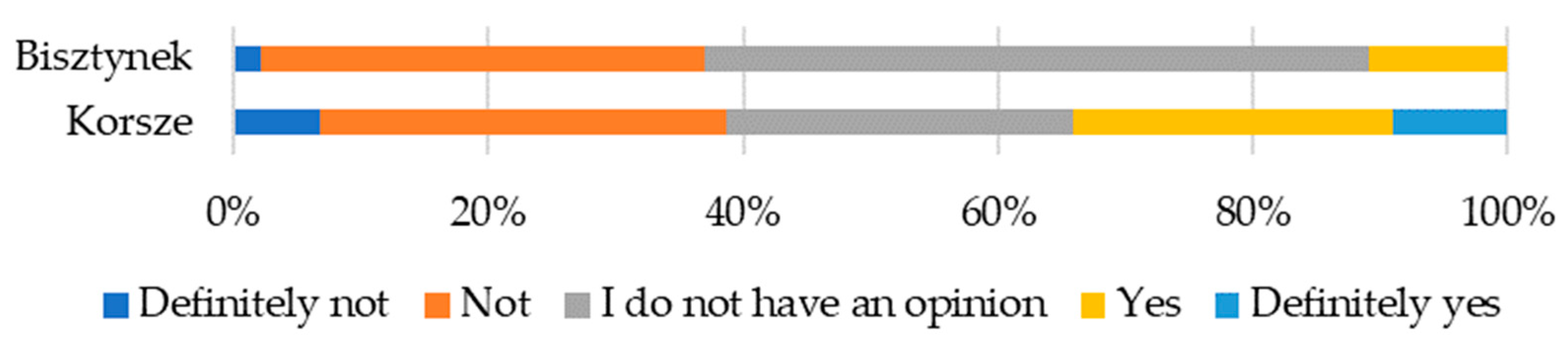

3.1. Knowledge of and Support for Wind Energy Development

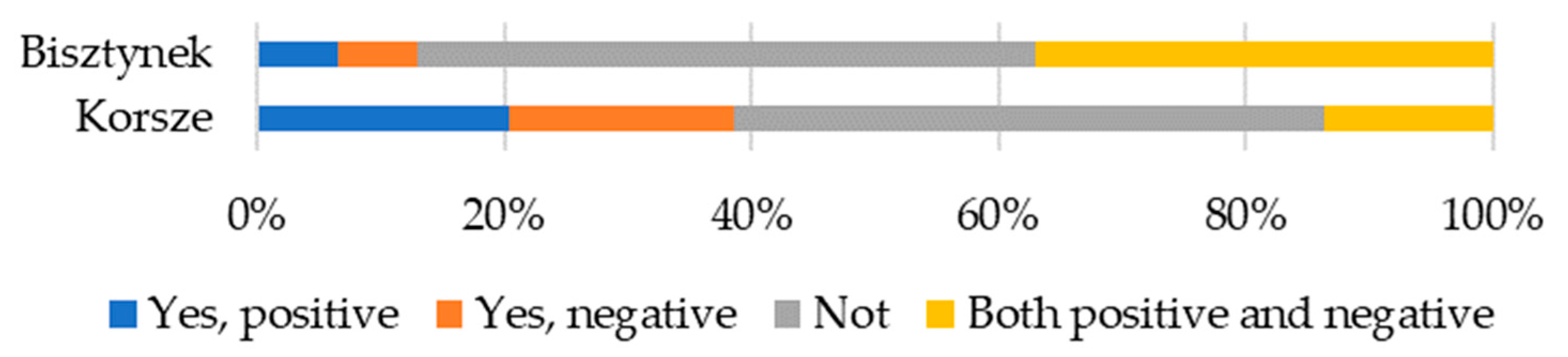

3.2. Assessment of the Impact of Wind Energy Investments on the Landscape According to Respondents

3.2.1. Assessment of the Importance of the Positive Effects of the Construction of Wind Turbines in the Municipalities of Korsze and Bisztynek

3.2.2. Assessment of the Importance of the Negative Effects of the Construction of Wind Turbines in the Municipalities of Korsze and Bisztynek

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Europejska Konwencja Krajobrazowa, Sporządzona we Florencji dnia 20 Października 2000 r. 2000. Available online: http://ochronaprzyrody.gdos.gov.pl/tekst-i-zalozenia-konwencji-krajobrazowej (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Badora, K. Ocena wpływu farm wiatrowych na krajobraz–aspekty metodyczne i praktyczne. Problemy Ekologii Krajobrazu 2011, 31, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Armand, D.L. Nauka o Krajobrazie; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1980; p. 335. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak, M. Syntezy Krajobrazowe: Założenia, Problemy, Zastosowania; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 1998; p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Ostaszewska, K. Geografia krajobrazu. In Wybrane Zagadnienia Metodologiczne; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- Richling, A.; Solon, J. Ekologia Krajobrazu; Wyd., V., Ed.; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2011; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Myga-Piątek, U. Spór o pojęcie krajobrazu w geografii i dziedzinach pokrewnych. Przegląd Geogr. 2001, 73, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Degórski, M.; Ostaszewska, K.; Richling, A.; Solon, J. Contemporary directions of landscape study in the context of the implementation of the European Landscape Convention. Przegląd Geogr. 2014, 86, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plit, F. Landscape in the space or the space in the landscape. Diss. Cult. Landsc. Comm. 2014, 24, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczyński, W. Leksykon Wiedzy Geograficznej; Jedność: Kielce, Poland, 2007; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, T.J.; Chmielewski, S.; Kułak, A. Perception and projection of the landscape: Theories, applications Expectations. Przegląd Geogr. 2019, 91, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, T.; Sharpe, D.; Jenkins, N.; Bossanyi, E. Wind Energy Handbook; Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2001; p. 642. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualetti, M.J.; Gip, P.; Righter, R.W. (Eds.) Wind Power in View. Energy Landscapes in a Crowded World; Academic Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gipe, P. Wind Energy Basics: A Guide to Home- and Community-Scale Wind Energy Systems, 2nd ed.; Chelsea Green Publishing Company: Hartford, VT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stryjecki, M.; Mielniczuk, K. Wytyczne w Zakresie Prognozowania Oddziaływań na Środowisko Farm Wiatrowych; GDOŚ: Warszawa, Poland, 2011; Available online: https://fnez.pl/wpcontent/uploads/2020/06/Wytyczne.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Badora, K. Zalecenia w Zakresie Uwzględnienia Wpływu Farm Wiatrowych na Krajobraz w Procedurach Ocen Oddziaływania na Środowisko; Generalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska: Warsaw, Poland, 2017.

- Gospodarka Energetyczno-Paliwowa w latach 2021 i 2022. 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/energia/gospodarka-paliwowo-energetyczna-w-latach-2021-i-2022,4,18.html (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Globalna Energia. 2024. Available online: https://globenergia.pl/288-gw-mocy-elektrycznej-i-27-produkcji-z-oze-podsumowanie-energetyczne-2023-roku/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Bielewicz, J. “Zielona” inflacja już tu jest. Obs. Finans. 2022, 2, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Energia ze źródeł Odnawialnych w 2022 r; 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/wyszukiwarka/?query=tag:energia+ze+%C5%BAr%C3%B3de%C5%82+odnawialnych (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Sikora, J.; Zimniewicz, K. Renewable energy sources as a way to prevent climate warming in Poland. Econ. Environ. 2023, 85, 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive–EU–2023/2413–EN–EUR-Lex (europa.eu). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/2413/oj (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Strzałkowski, M.; Suchomska, J. Konflikt w przestrzeni i przestrzeń dla konfliktu: Wpływ partycypacji społecznej na spory w przestrzeni publicznej. Dyskurs Dialog 2019, 2, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwińska, A. Konflikty w przestrzeni społecznej miasta. Space Soc. Econ. 2009, 9, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, J.; Hoen, B. Thirty years of North American wind energy acceptance research: What have we learned? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 29, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badora, K. Społeczna percepcja energetyki wiatrowej na przykładzie farmy wiatrowej Kuniów. Proc. ECOpole 2017, 11, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolwig, S.; Bolkesjø, T.F.; Klitkou, A.; Lund, P.D.; Bergaentzlé, C.; Borch, K.; Olsen, O.J.; Kirkerud, J.G.; Chen, Y.K.; Gunkel, P.A.; et al. Climate-friendly but socially rejected energy-transition pathways: The integration of techno-economic and socio-technical approaches in the Nordic-Baltic region. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 67, 101559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska-Dąbrowska, M.; Świdyńska, N.; Napiórkowska-Baryła, A. Attitudes of Communities in Rural Areas towards the Development of Wind Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Wind power and the NIMBY-myth: Institutional capacity and the limited significance of public support. Renew. Energy 2000, 21, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek-Szczepańska, M. Wizerunek energetyki wiatrowej i jej oddziaływania na społeczeństwo w świetle doniesień mediów regionalnych i lokalnych w Polsce. Czas. Geogr. 2023, 94, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K. Blowing in the wind: A brief history of wind energy and wind power technologies in Denmark. Energy Policy 2021, 152, 112–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintz, G.; Leibenath, M. The politics of energy landscapes: The influence of local anti-wind initiatives on state policies in Saxony, Germany. Energy. Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, L.S.; Boudet, H.S.; Karmazina, A.; Taylor, C.L.; Steel, B.S. Opposition “overblown”? Community response to wind energy siting in the Western United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 43, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiniti, G.; Daras, T.; Tsoutsos, T. Analysis of the Community Acceptance Factors for Potential Wind Energy Projects in Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Beyond NIMBYism: Towards an integrated framework for understanding public perceptions of wind energy. Wind Energy 2005, 8, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, S.; Konisky, D.M.; Atiq, Z.; Land, N. Energy infrastructure, NIMBYism, and public opinion: A systematic literature review of three decades of empirical survey literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 093007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassmer, R.W.; Wahid, I. Does the Likely Demographics of Affordable Housing Justify NIMBYism? Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 29, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Social acceptance revisited: Gaps, questionable trends, and an auspicious perspective. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 46, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocavini, G. The Trans-Adriatic Pipeline and the Nimby Syndrome. Roma Tre Law Rev. 2019, 1, 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Han, Y.H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.D. The community residents’ NIMBY attitude on the construction of community ageing care service centres: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 22, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X.; Fu, L.; Wang, J. Exploring Factors Influencing Scenarios Evolution of Waste NIMBY Crisis: Analysis of Typical Cases in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthoora, T.; Fischer, T.B. Power and perception—From paradigms of specialist disciplines and opinions of expert groups to an acceptance for the planning of onshore windfarms in England—Making a case for Social Impact Assessment (SIA). Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markuszewska, I. The Energy Landscape versus the Farming Landscape: The Immortal Era of Coal? Energies 2021, 14, 7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Bai, X.; Duan, N. Comprehensive Evaluation of NIMBY Phenomenon with Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process and Radar Chart. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Chen, Y.; Cui, C.; Xia, B.; Ke, Y.; Skitmore, M.; Liu, Y. How to Shape Local Public Acceptance of Not-in-My-Backyard Infrastructures? A Social Cognitive Theory Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, Y.; Ono, Y. Susceptibility to threatening information and attitudes toward refugee resettlement: The case of Japan. J. Peace Res. 2023, 60, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Environmental disputes in China: A case study of media coverage of the 2012 Ningbo anti-PX protest. Glob. Media China 2017, 2, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, C.; Xia, B.; Cui, C.; Coffey, V. Impact of community engagement on public acceptance towards waste-to-energy incineration projects: Empirical evidence from China. Waste Manag. 2018, 76, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundheim, S.H.; Pellegrini-Masini, G.; Klöckner, C.A.; Geiss, S. Developing a Theoretical Framework to Explain the Social Acceptability of Wind Energy. Energies 2022, 15, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Duan, X.; Ji, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, H. Evolutionary game analysis of stakeholder behavior strategies in ‘Not in My Backyard’ conflicts: Effect of the intervention by environmental Non-Governmental Organizations. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantál, B. Living on coal: Mined-out identity, community displacement and forming of anti-coal resistance in the most region, Czech Republic. Resour. Policy 2016, 49, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Conceptualising social impacts. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2002, 22, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borch, K.; Munk, A.; Dahlgaard, V. Mapping wind-power controversies on social media: Facebook as a powerful mobilizer of local resistance. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Laike, T. Intention to respond to local wind turbines: The role of attitudes and visual perception. Wind Energy 2007, 10, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindmarsh, R. Hot air ablowin! ‘Media-speak’, social conflict and the ‘decoupled’ Australian wind farm controversy. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2013, 44, 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazeta pomorska.pl–Gazeta Pomorska, naszemiasto.pl–Nasze Miasto. Available online: https://pomorska.pl/konstantynowo-we-wsi-ma-powstac-park-wiatrowy-mieszkancy-protestuja/ar/7207748 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Jasiński, A.W.; Kacejko, P.; Matuszczak, K.; Szulczyk, J.; Zagubień, A. Elektrownie Wiatrowe w Środowisku Człowieka; Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk Komitet Inżynierii Środowiska: Lublin, Poland, 2022; Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://kis.pan.pl/images/stories/pliki/pdf/Monografie/Monografia178.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwi3wZnW5f6FAxX2RfEDHSx-DbkQFnoECBEQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1UwKC8GG1VIRCsia4fjPQm (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Mroczek, B. Akceptacja Dorosłych Polaków dla Energetyki Wiatrowej i Innych Odnawialnych Źródeł Energii, Streszczenie Raportu z Badań; Pomorski Uniwersytet Medyczny, Polskie Stowarzyszenie Energetyki Wiatrowej: Szczecin, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krohn, S.; Damborg, S. On public attitudes towards wind power. Renew Energy 1999, 16, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Planning of renewables schemes: Deliberative and fair decision-making on landscape issues instead of reproachful accusations of non-cooperation. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2692–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini-Masini, G. Wind Power and Public Engagement: Co-Operatives and Community Ownership; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevenant, M.; Antrop, M. Transdisciplinary landscape planning: Does the public have aspirations? Experiences from a case study in Ghent (Flanders, Belgium). Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryszkowska, B.; Starczewski, T.; Chodkowska-Miszczuk, J. Rozwój energetyki wiatrowej w przestrzeni submiejskiej a percepcja krajobrazu kulturowego. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2018, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolak, M.; Pawelec, P. Problematyka ocen krajobrazu w kontekście lądowych farm wiatrowych w Polsce. Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. 2023, 64, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.R.; Lumsden, C.; O’Dowd, S.; Birnie, R.V. ‘Green On Green’: Public perceptions of wind power in Scotland and Ireland. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2005, 48, 853–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akincza, M.; Mazur, A. Wpływ elektrowni wiatrowych na krajobraz kulturowy Warmii, Mazur i Powiśla. Teka Kom. Archit. Urban. Stud. Kraj. 2013, 8, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinek, R.; Myczkowski, Z. Ocalić wiatr. Potrzeba zmian w ochronie krajobrazu kulturowego Ciechocinka. Wiadomości Konserw. 2023, 73, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożętka, B. Pozyskiwanie energii wietrznej a zmiany krajobrazu. Konsekwencje dla funkcji rekreacyjnej. Kraj. Rekreac. Kształtowanie Wykorzystanie Transform. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2010, XVII, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gutersohn, H. Harmonie in der Landschaft; Vogt-Schild A.G.: Solothurn, Switzerland, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Nadaï, A.; van der Horst, D. Introduction: Landscapes of Energies. Landsc. Res. 2010, 35, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecki, S.; Jusińska, D. Wpływ energetyki wiatrowej na otoczenie naturalne—Opinie ludności. Energetyka 2015, 2, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G.; Ferraro, G. The Social Acceptance of Wind Energy: Where We Stand and the Path Ahead; EUR 28182 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betakova, V.; Vojar, J.; Sklenicka, P. Wind turbines location: How many and how far? Appl. Energy 2015, 151, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleaner Energy. Available online: https://cleanerenergy.pl/2022/03/29/polskie-farmy-wiatrowe-edp-renewables-maja-juz-747-mw-mocy/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Raport o stanie gminy Korsze w roku 2020. 2021. Available online: https://bip.korsze.pl/wiadomosci/12608/wiadomosc/574172/raport_o_stanie_gminy_korsze_za_2020_rok (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Projekt Założeń do Planu Zaopatrzenia w Ciepło, Energię Elektryczną i Paliwa Gazowe dla Miasta i Gminy Korsze na lata 2021–2035. 2021. Available online: https://konsultacje.korsze.pl/attch/documentfile/file-2-14-1629091561.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Instalacje budowlane. Available online: https://www.instalacjebudowlane.pl/7935-24-87-elektrownie-wiatrowe--wietrznosc-w-polsce.html (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Lorenc, H. (Ed.) Atlas klimatu Polski; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rynek energetyczny. 2023. Available online: https://www.rynekelektryczny.pl/najwieksze-farmy-wiatrowe-w-polsce/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Local Data Bank. 2024. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Prognoza Oddziaływania na Środowisko do Miejscowego Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Miasta Bisztynek. 2018. Available online: http://www.bisztynek.pl/asp/pliki/10_2018/bisztynek_pos_tekst.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Zoderer, B.M.; Tasser, E.; Erb, K.H.; Lupo Stanghellini, P.S.; Tappeiner, U. Identifying and mapping the tourists’ perception of cultural ecosystem services. A case study from an Alpine region. Land Use Policy 2016, 56, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domon, G. Landscape as resource. Consequences, challenges and opportunities for rural development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, M.; Nasar, J.L.; Chun, B. Neighborhood satisfaction, physical and perceived naturalness and openness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernik, J.; Gawroński, K.; Dixon-Gough, R. Social and economic conflicts between cultural landscapes and rural communities in the English and Polish systems. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senetra, A. Badania ankietowe jako element konstrukcji metody bonitacyjnej oceny wartości estetyczno-widokowych krajobrazów na przykładzie wiejskich obszarów pojeziernych. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2016, 15, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, K.; Obieraj, A. Sampling Methodology in Social Sciences. Bezpieczeństwo Tech. Pożarnicza 2013, 4, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajowiecki, J.; Sztuba, W.; Lasocki, K. Polska Energetyka Wiatrowa 4.0. TPA Poland. 2022. Available online: http://psew.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/skompresowany-raport-22Polska-energetyka-wIatrowa-4.022-2022-.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Niewiadomski, A. Lokalizowanie odnawialnych źródeł energii na obszarach wiejskich w świetle zasad planowania przestrzennego. Stud. Iurid. 2022, 91, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specification | Municipality Korsze | Municipality Bisztynek | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 41 | 65 |

| Men | 59 | 35 | |

| Age (years) | 18–25 | 9 | 9 |

| 26–36 | 32 | 30 | |

| 37–50 | 32 | 35 | |

| Above 50 | 27 | 26 | |

| Education | Primary/secondary | 9 | 2 |

| Professional | 20 | 20 | |

| Secondary | 34 | 41 | |

| Higher | 36 | 37 | |

| Positive Effects of Wind Turbine Construction | Respondents from the Group That Indicated only Positive Impacts | Respondents from the Group That Indicated Positive as well as Negative Impacts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korsze | Bisztynek | Korsze | Bisztynek | |

| Landscape diversification | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Raising tourist attractions | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| Building of positive associations with the municipality | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Integration with the surrounding nature | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Clean-up of the area as a result of the landscaping work | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Improvement of aesthetics in areas with a disturbed landscape, e.g., mine sites, industrial areas, etc. | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Negative Effects of Wind Turbine Construction | Respondents from the Group That Indicated only Negative Impacts | Respondents from the Group That Indicated Negative as Well as Positive Impacts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korsze | Bisztynek | Korsze | Bisztynek | |

| Disruption of the harmonious landscape | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Introduction of a very strong visual stimulus—tall power plant structures are the dominant high-altitude component of the landscape | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Overshadowing of naturally or culturally valuable landscape elements | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

| Interference with ecosystems | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Depletion of the area of natural trees and bushes | 6 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Degradation of existing natural and compositional values | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Świdyńska, N.; Witkowska-Dąbrowska, M.; Jakubowska, D. Influence of Wind Turbines as Dominants in the Landscape on the Acceptance of the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17133268

Świdyńska N, Witkowska-Dąbrowska M, Jakubowska D. Influence of Wind Turbines as Dominants in the Landscape on the Acceptance of the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland. Energies. 2024; 17(13):3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17133268

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚwidyńska, Natalia, Mirosława Witkowska-Dąbrowska, and Dominika Jakubowska. 2024. "Influence of Wind Turbines as Dominants in the Landscape on the Acceptance of the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland" Energies 17, no. 13: 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17133268

APA StyleŚwidyńska, N., Witkowska-Dąbrowska, M., & Jakubowska, D. (2024). Influence of Wind Turbines as Dominants in the Landscape on the Acceptance of the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland. Energies, 17(13), 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17133268