1. Introduction

Implementing the “smart city” concept is one of the ways of responding to the current challenges of rapid urbanization [

1,

2]. In practice, it is a municipality’s response to the continuously emerging challenges connected with urban management, a way of gaining a competitive edge, improving the quality of life of its inhabitants, reducing energy needs, protecting the environments, preventing depopulation processes and so on. In order to effectively tackle these issues, municipalities are not only required to introduce innovative “smart” technologies and solutions, but also to conduct an active local governmental policy open to all the stakeholders within the municipal community, as well as to initiate multi- and intersectoral collaboration between them [

3].

The process was complex and stretched over time. Initially, municipalities began to implement ICT solutions and coordinate their governance activities to improve the quality of life of residents [

4,

5,

6]; then, they focused on the creative engagement of human capital [

7], and finally began to take the advantages offered by sustainable development [

8] gradually transforming from Smart City 1.0 to Smart City 4.0 [

9]. Some smart cities are evolving into Human Smart Cities, which use technology, open data, and citizen engagement to solve urban problems [

10], while others have gone a step further by treating ‘smart’ solutions as a tool to achieve sustainability goals [

8,

11].

In the process of adopting the smart city concept, cities’ authorities have faced a variety of barriers and challenges in implementing a strategic approach [

5,

12], developing mechanisms for collective thinking and action by various groups of stakeholders [

7,

13], or leadership [

14,

15,

16] and smart governance [

4,

5,

17].

Using an evidence-based approach, smart specializations have emerged [

18] and business ecosystems have been developed around them [

19], such as by the creation of innovative clusters [

20]. As a result, smart city ecosystems have been formed [

21,

22,

23] while the smart city began to be treated as a smart city innovation ecosystem [

24,

25].

The implementation of the smart city concept has been of particular importance in post-socialist cities [

26,

27], which experienced the effects of the political and socio-economic transformation of the early 1990s [

28]. To capitalize on the benefits of integration in international networks and improve their competitive advantage, many municipalities have positioned the implementation of a smart city concept as a new paradigm for rapid and sustainable socio-economic growth [

29].

This study aims to present the processes and mechanisms of creating a holistic Smart City Ecosystem Model (SCEM) linking the business and stakeholder ecosystems. Based on the literature review and in-depth analyses of a case study that represents an example of a post-socialist peripheral metropolis (Lublin, Poland) we demonstrate that the implementation of tailored strategic thinking based on adaptation to global trends, exploitation of development potentials and niches as well as interactions among stakeholders operating at different levels of governance and engagement allow for the coordination and mobilization of development processes leading to the creation of effective smart city ecosystems. We also present the long-term effects of smart specialization in terms of creating innovative clusters and building business ecosystems around them. The results of the analysis led to the formulation of the Smart City Ecosystem Model (SCEM), which may be contextually applied in other cities.

The contributions of the study are as follows: (1) it provides new insights into smart governance, leadership in creating a sustainable and human smart city; (2) it provides analyses of strategic choices in the creation of a stakeholder ecosystem, while competitive business ecosystems based on smart specializations provide new opportunities for the design and implementation of smart city strategies. Therefore, the study provides a new multidimensional policy framework for smart cities at both strategic and operational levels that can improve the holistic management of smart and sustainable cities and communities. This study can serve as a starting point for undertaking research on the mechanisms for implementing strategic thinking and their effects on creating smart city ecosystems.

The study area is Lublin (Eastern Poland), one of the mid-size cities located on the peripheries of Central Eastern Europe, which experienced economic collapse during the political transformation and the post-socialist transition towards a market economy [

30], and which based their post-transformation trajectory of genuine convergence on implementing smart city solutions [

27] as well as the processes of metropolization [

31]. The city authorities are devising and successfully implementing their own accelerated and elaborate developmental path in accordance with Smart City 3.0 and 4.0 logic, involving citizens in co-managing the city and shaping its future, as well as creating efficient stakeholder and competitive business ecosystems.

The paper is structured as follows: after an introduction (

Section 1), scene-setting literature review (

Section 2), materials, methods and the case study characteristics (

Section 3) were presented. The analytical procedure and the developed models are summarized in

Section 4, followed by a discussion in

Section 5 and conclusions in

Section 6 (

Figure 1).

4. Results

4.1. Towards Smart City Strategy

4.1.1. Post-Transformation Development

After 1989, the city experienced several problems related to its political and socio-economic transformation, including rapid delayed post-transformational deindustrialization [

84], and therefore Lublin did not take advantage of the opportunities offered by the globalization and internationalization processes. It was affected by a delayed economic transformation, and the problems reached their peak at the turn of the century. The delayed (frozen) transformation of Lublin was associated with a few phenomena [

30], such as the liquidation of practically the entire automotive sector (caused, in turn, by the collapse of Daewoo Motors in Korea in 2000, a strategic investor in the Lublin automotive industry) and four bank headquarters which gave employment to several thousand people and had strong multiplier effects on the city economy. Furthermore, a large number of companies from the remaining sectors were unable to restructure quickly, falling in value chains or market position rankings in their industries, which caused stagnation and made the impression of “freezing” economic development in Lublin [

30]. As a result, one could observe the increasing outflow of staff and capital outside the city and the lack of public policies aimed at supporting local development [

30,

81]. In 2002, the employment rate dropped to a historical minimum of 97,000 people, accounting for 61 percent of the value from 1990. Even accession to the European Union in 2004 did not change the situation.

Only since 2007 has rapid economic growth been observed through the use of unique and effective methods of strengthening endogenous potential. First, these methods were based on cultural activities and linked to Lublin’s efforts to become a European Capital of Culture 2016. As a result, The Jagiellonian Fair, the Night of Culture, the Magicians’ Carnival (Carnaval Sztukmistrzów) and the Urban Highline Festival—unique and spectacular events that attract around 300,000 tourists annually—were initiated. Moreover, Lublin was awarded the title of a historical monument, and three objects connected with the Lublin Union were inscribed on the European heritage list. These initiatives introduced Lublin to the national and international arena. Secondly, the Lublin economic zone was established, which, in the subsequent years, attracted more investors and generated thousands of new workplaces. New events and investments were effectively promoted in Poland and abroad by the new Lublin’s brand and a coherent system of visual identification of the city refers to the colors of the crest of Lublin and the history of the city. The slogan “Lublin, a city of inspiration” reflects the spirit and abilities of the city and its citizens [

85].

4.1.2. Strategic Approach Implementation

In 2011, the city implemented a strategic approach to its development and commenced work on a new strategy for Lublin. The two-year strategic process involved the participation of approximately 500 people in its creation. Lublin’s 2020 strategy [

86] defines four areas of strategic intervention: openness, friendliness, entrepreneurship and academia. It was the first city development strategy in Poland to employ the concept of regional smart specialization, implemented at the municipal level.

In the process of building the strategy for Lublin, the Lublin Development Council was established by the mayor. It consisted of experts representing various circles, including academia, business, culture, and non-governmental organizations. The Council gave its opinion on the strategy document, and in the following years of strategy implementation, most of the Council members have carried out voluntary work aiding the social and economic development of the city. The strategic process initiated an extremely important step that presented a major obstacle in Lublin’s development: building trust between various stakeholders in the city. It was a very important foundation for building new initiatives and institutions in the city, and after the functional complexity of Lublin had increased, it allowed the first metropolization processes to begin. These were no longer controlled by the city and its structures.

The development of the Lublin 2020 strategy has also led to the beginning of new strategic thinking of both the city authorities and numerous institutions cooperating with it, and it initiated Lublin’s transition to a smart city. This provided the basis for implementing smart city dimensions, which were refined in the new Lublin 2030 Strategy [

87] (

Table 1). These will be discussed in the subsequent sections of the article.

In view of the above, a very important element of the Lublin 2030 Strategy is its monitoring and evaluation system, which consists of four main elements, complementing each other and compensating for each other’s weaknesses: (a) monitoring of quantitative indicators and metrics; (b) monitoring the implementation of tasks and key projects; (c) social surveys; (d) evaluation of the effects of implementation in the form of expert debates devoted to assessing the implementation of goals in five development areas. Based on the experience and results of research conducted in the preparatory phase of the development of the Lublin 2030 strategy (

Supplementary Materials File S1), this system provides sophisticated monitoring activities (for each dimension of the smart city), including not only several hundred hard direct indicators, but also a set of numerous indirect and hidden metrics obtained from social surveys and the local data ecosystem (for example, the level of satisfaction of residents and businesses with the use of city services, the quality of the local investment climate, the sense of fairness in the redistribution of resources by the city government, etc.).

4.2. Smart Specialization for Business Ecosystems

4.2.1. Smart Specialization as a Base for Business Ecosystems Development

The selection processes of businesses were targeted at indicating the key sectors for the present and future development of the city. The conditions that determined the choice of a given specialization included, among other things, the economic assets of Lublin and previous specializations (historically developed in Lublin), barriers for the relocation (withdrawal) of investors from a given line of business in the city, the ease of attracting further investors to the sector or whether the given sector is a future industry. As the outcome of the selection processes, eight sectors (smart specializations) were chosen: three priority sectors (food industry, BPO/SSC, and IT) and five complementary sectors (logistics and transport, renewable energy, automotive industry, health services and pharmacy and biotechnology. Lublin adopted its smart specializations shortly after the concept had been introduced by the EU in 2011 [

88] and a few years before the region and Poland [

89], which enabled faster development of the selected economic sectors by attracting new investors thanks to dedicated promotional and information activities.

4.2.2. Building Competitive and Innovative Business Ecosystems

The strategy and activities related to its implementation trigger the co-creation of business ecosystems by the city in various models (

Table 2). In the years 2012–2022, the city of Lublin initiated and implemented, most often successfully, five large ecosystem programs, as detailed in

Table 2. The earliest program of the Lublin IT Upland (the word ‘Upland’ refers to the location of the city on the Lublin Upland), i.e., the construction of an IT hub in Lublin, was initiated. The choice of this project as the first one was associated with several factors, including a certain tradition of the IT sector in Lublin and the availability of staff and graduates of universities and offices. The barrier to its development, in turn, was not the factors related to infrastructure availability, because the location of the IT sector is not so much conditioned by them as the industry sector. Projects for other service ecosystems, such as innovative medicine and medical services, were launched in turn.

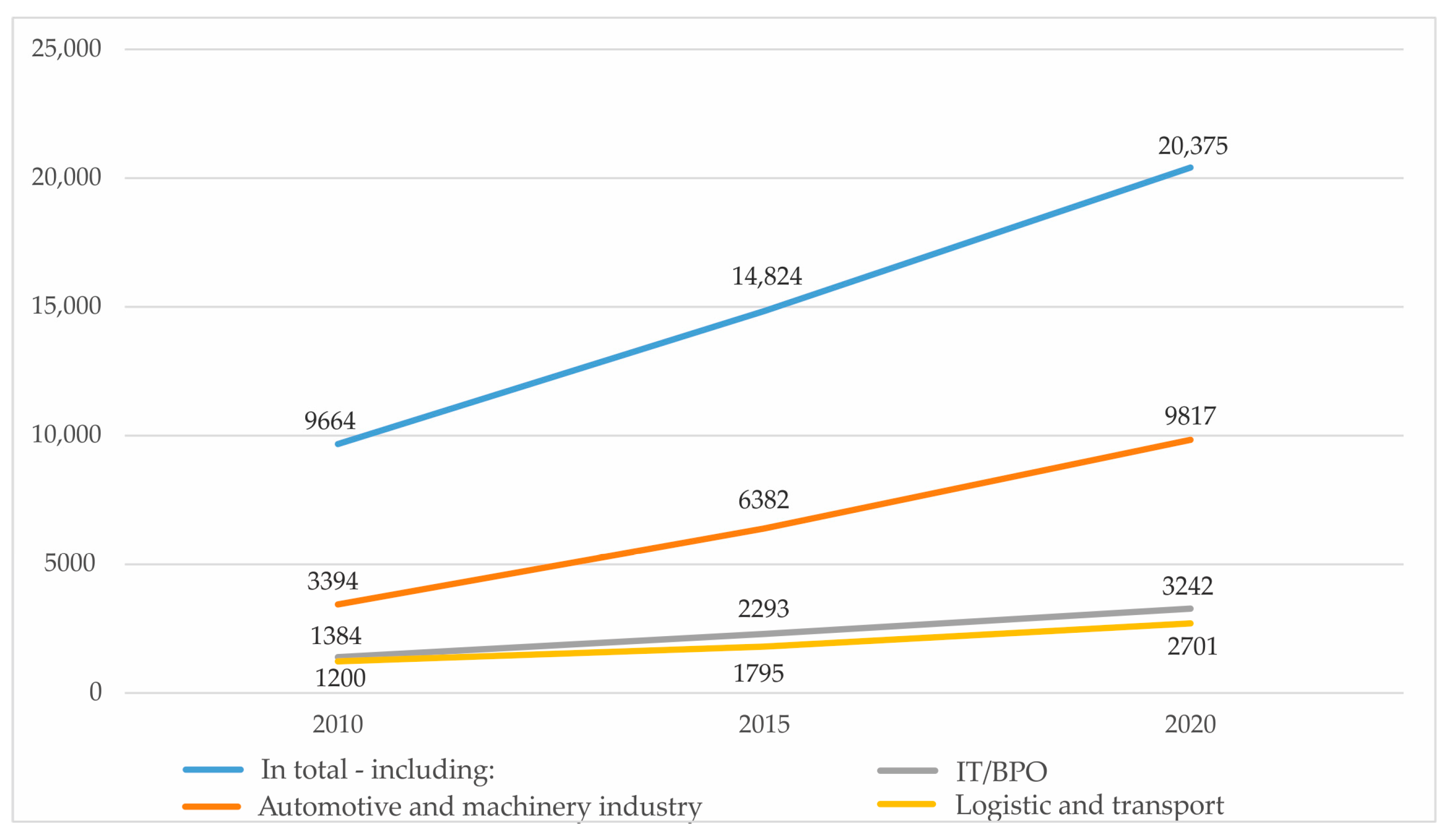

4.2.3. Development of Priority Sectors

Processes stimulating entrepreneurship and providing support for business ecosystems resulted in a rapid increase in employment in priority sectors. It has tripled in IT/BPO and doubled in the automotive and machinery industry, as well as logistics and transport, over the last ten years (

Figure 3). In the years 2010–2020, despite the transport cut-off, a total of approximately seventy new investors were attracted to the city of Lublin. The total number of new investment projects, including local reinvestments, exceeded 120. Lublin is currently an important business services center in the country and the largest in East Poland. The position of Lublin as a place of BPO (Business Process Outsourcing)/SSC (Shared Service Centre) business is comparable to that of Varna, Tallinn, and Riga due to its low operating costs and low critical mass [

90]. Lublin has also joined the trend of migration of new outsourcing investments observed in CEE and is gaining popularity similar to that of Brno, Ostrava, Debrecen, Miskolc, Brasov or Timisoara [

91]. Lublin is one of the main developing locations in Poland [

92], which is distinguished in terms of growth of both employment and new investments [

93].

4.3. Collective Thinking and Action—Ecosystem of Stakeholders

Working on this strategy, Lublin 2020 (2011–2012) proceeded with the involvement of various stakeholders. At open meetings and public debates, the main assumptions of the strategy were developed. The draft was widely consulted by about 2000 people. These activities resulted in an unprecedented integration of various communities: scientists, businesses, cultural communities, city activists, etc., and the development of cross-sector cooperation mechanisms. The creation of collaborative ecosystems in line with the quadruple helix has begun [

49,

76], with “city” representing the local government and local government institutions; “citizens”—city residents, community activists, and civil society institutions; “business”, encompassing a wide range of public and private enterprises; and, finally, “academia”, comprising the universities and research centers, as well as scientists, scholars and students. The collaborative efforts of these stakeholders, which have harnessed the resources of new knowledge, technologies, products, and services, have dynamized, among other things, the formation of clusters [

94], or support of the Lublin’s bicycle ecosystem [

95]. Notably, ecosystems continue to operate and expand their reach by “pulling in” stakeholders from across the region (e.g., cyclists, medical business, etc.), Poland (e.g., cluster and corporate entities and BEIs, start-ups, creative businesses) and the world (university and foreign student ecosystems) [

94].

Projects initiated by the business community focused on improving the quality of life in the city are also noteworthy. An example of this may be the project of greening the Lublin Special Economic Zone, coordinated by the City Hall and implemented by urban planners and students from Lublin universities. A number of these projects are directed towards the youth, including Lublin Urban Club (Skende Shopping Centre—the City Hall—urban planners—students), or “Entrepreneurial Kids” (city–business–universities), which has been also conducted in Ukraine since 2021, and has continued despite the ongoing war in the country. These projects not only facilitate the creation of stakeholder ecosystem through multi-sectoral actions; they also creatively engage the citizens in the promotion of innovativeness and entrepreneurship, and, more broadly, in the city’s sustainable development.

Our research further showed that each group was characterized by specific attributes (

Figure 4), the mobilization of which allowed the city to achieve the best results in creating an ecosystem of stakeholders. Four elements were crucial. First, the actions of all stakeholders were guided by a common and coherent vision stemming from the assumptions of smart and innovative strategy and the brand “Lublin—a city of inspiration” [

85], with which most residents identify [

94]. For the vision to come into effect and stakeholders to be motivated to action, responsible leadership of the city government was required. The city government was the initiator, coordinator or active participant in most of the activities related to the creation and maintenance of an ecosystem. Third, the city’s activities mobilized not only city officials, but also all other ecosystem stakeholders, and through active participation, their involvement increased. Finally, this translated into an improvement in the competencies of ecosystem participants, both soft, such as those open to new challenges and willing to cooperate, as well as hard, including the acquisition of new knowledge related to the problems and phenomena occurring in the city, and management and leadership skills (

Figure 4). Similar collaborative mechanisms were used on a larger scale in the process of building the Lublin 2030 strategy, integrating a multitude of stakeholders in the city, and expanded cooperation using collaborative learning processes to create business ecosystems.

4.4. Leadership and Coordination of Development Processes by the City

Coordination and integration of development processes by the city is a crucial element in smart city ecosystem development. In this context, we can discuss two aspects. One of the key tasks of the local government, especially in post-socialist cities, is to restore and modernize industry and services and attract external investors to the priority sectors [

84]. The city achieved these goals by building its own entrepreneurial ecosystem and promoting pro-business attitudes among the investors and residents. The creation of modern business ecosystems is the result of the city’s coordination of many economic strategies, a skillful adaptation of global solutions, and the effect of the chosen path of smart specialization. It should be emphasized that the city was the initiator of all these actions, and it succeeded in coordinating their implementation based on cooperation with business and academia, including attracting new businesses and strengthening the existing ones, stimulating knowledge transfer from universities, bringing university programs closer to the requirements of the labor market or supporting economic and competence-building events, and thus co-creating related business ecosystems.

One of the examples is the Lublin subzone of the special economic zone, launched in 2007 with the support of EU funds (EUR 25M). From the beginning, the zone’s development was supported and coordinated by the city (the Department for Investor Services was launched for this purpose). The comparison of 2010 and 2021 shows a considerable increase in the number of investors (13 in 2010, 84 in December 2021), special economic zone permits (13 and 36, respectively), and workplaces (600 and 6500, respectively). Similar trends are observed in the case of start-ups. Together with the Lublin Science and Technology Park and over thirty other entities, in 2015, the city of Lublin built a platform aimed at incubating new innovative businesses, particularly those in the area of IT and biotechnology. Within seven years, their number increased from 20 to 330. The city’s conscious and coordinated pro-business policies have provided a strong boost to entrepreneurship and employment growth. In the years 2010–2020, total employment in Lublin increased from 115,000 to 127,500. As much as 90% of this growth was due to new business projects, almost exclusively in the IT and modern business services sector. It is worth mentioning that a strong increase in employment was observed in local production companies, which were promoted in global value chains.

Another element of building the city’s ecosystem potential, due to the public policy of coordination, is the ability to search for and manage development niches. In the case of Lublin, this is exemplified by the internationalization of higher education. Although Lublin does not have a long tradition in this field, and the majority of the nine universities were established after World War II, today, Lublin is the sixth university center in Poland, with 61,000 students, and more than 14,000 graduates annually. Due to the close cooperation between the city and universities, and joint promotional activities carried out under the program “Study in Lublin” (initiated and run by the city), the number of foreign students has increased five-fold since 2010, from 1400 to almost 8000 in 2021, and its internationalization rate is now one of the highest in the country (12% in 2020 compared to 1.7% in 2010). The city’s objective is to reach 15% in 2025, which would be comparable to top OECD-performing countries [

96]. In 2016, the American College Magazine listed Lublin as one of the top ten student-friendly cities in Europe. Another niche is the creative industry. The local creative sector includes over 4300 businesses. Lublin is perceived as the fifth most creative city in Poland [

97].

The coordination of development processes is not possible without external financing. The city authorities pursue a broad pro-investment policy. Over the last ten years, EUR 1.5 billion has been invested. Flagship investments such as a new stadium, roads, low-carbon emission public transport, infrastructure for culture, or new public spaces not only create the image of a modern city, but also improve the quality of life of its inhabitants.

In 2014–2021, Lublin developed its cooperation with the neighboring communes as part of the implementation of Integrated Territorial Investments (ITIs) (under the EU CP 2014–2020; allocation EUR 105M) in the Lublin Functional Area, which consists of 16 communes, covers an area of 1582 km

2 and has almost 548,000 inhabitants. The ITIs implementation process is an example of a top-down rather than a bottom-up initiative [

98], although it has a positive impact on building a culture of intermunicipal cooperation and leads to wide-ranging effects in the form of investments in the metropolitan multimodal (bus and railway) station, public transport, revitalization and green areas, which are important for the city and the entire functional area. In 2020, the Lublin FUA was enlarged by another six municipalities and four counties. In 2022, the Lublin Metropolitan Area (LMA) Association was established; under this heading, it will continue to conduct joint activities for the development of the Lublin metropolis. Currently, the association is developing key documents, i.e., the supra-local strategy and SUMP, which will influence the further development of the smart city ecosystem.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the city has received numerous awards and distinctions for its activities, including the international Smart City Certificate in 2019, as well as first place in Europe in the category of promoting entrepreneurial spirit in the European Entrepreneurship Promotion Awards (EEPA 2022) for the “Entrepreneurial Kids” project, seventh place in the ranking of European student-friendly cities and fifth place among seventy-five European metropolises in the talent pool category (Emerging Europe Business Friendly City Perception Survey, 2019). Lublin is also one of three Polish cities to have received the European Energy Award (EEA) certificate for developing and implementing local energy, climate and transport policies in accordance with the principle of sustainable development (2022) and holds first place in Poland in the Europolis report—green cities, produced by the Polish Robert Schuman Foundation (2021).

4.5. Smart Governance for Sustainable and Human Smart City

4.5.1. Adaptation to Global Trends: Towards Sustainable City

Lublin fits into Smart city 4.0 efforts by implementing integrated IoT infrastructure to increase the efficiency of municipal services and businesses and by improving the environment. The city, with the cooperation of business partners, built the required infrastructure (IT, Wi-Fi, LPWA, 5G, ITS) and data management systems for public transport and mobility, traffic management, energy-efficient LED lighting, buildings, energy, waste collection and recycling, electricity and heat supply, water supply and consumption, public safety and health. In its ‘smart’ actions, Lublin aims to reduce CO2 emissions and energy consumption and efficiently follow global trends to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

The city is constantly implementing smart city solutions to manage and optimize urban infrastructure. This has resulted in a 30% share of zero-emission transport in the public transport fleet over the last five years by developing, for example, a city bike system, a electric scooter sharing system and a trolley bus fleet using ITS solutions. The development of the city bicycle system (Lubelski Rower Miejski—LRM) is also notable, placing Lublin among the top cities in Poland (from 2014 to 2020, the number of registered users increased from 22,200 to 119,000, doubling the number of bicycles (to 900) and bicycle stations (to 98) [

95]. These activities are providing tangible environmental benefits. Over the next four years, on account of the introduction of new smart solutions, the city intends to achieve a 50% zero emission rolling stock index.

Building energy efficiency is a noticeable trend in the activities of the city and municipal companies. The city is implementing and financially supporting a number of investment and monitoring activities in the low-carbon building sector, such as thermal modernization, changing a heating system to non-carbon (e.g., under the “Program for Low Energy Purification (PONE)”) and conducting energy audits of buildings. MPWIK Sp. z o.o. (water and sewerage company) utilizes 70% of its own energy from biogas and photovoltaic farms. LPEC S.A., a heating energy company, employs the Building Emission Certification system and introduces “NO SMOG” labels, as well as using technologies that enable almost maintenance-free management of the entire city heating system. More than 75% of buildings in Lublin operated by LPEC are certified. Energy consumption and CO

2 emissions have been reduced by more than 55% in the schools covered by the thermal modernization program. These actions are reflected in the improvement in air quality [

55].

4.5.2. Human Smart City Lublin

Smart Human Cities can only be smart if they use data analytics to provide ‘smartness’, not only in terms of automating routine functions, but also in understanding, monitoring, analyzing and planning different aspects of the city, improving the quality of life of its residents and building a trusted governance model that engages and empowers citizens in co-creating solutions to collective social challenges [

10]. Lublin follows in this path, implementing new solutions in the realm of big data, e.g., the Open Data Lublin Portal offered 82 data sets, which constitutes a repository of knowledge for inhabitants, students, scholars, non-profit organizations and companies (

http://www.otwartedane.lublin.eu (accessed on 17 January 2023)), and a contact center for the inhabitants. Thanks to the availability and analysis of the collected data, a number of services for residents are being created, including projects of a social nature which promote equality, integration and social inclusion; for instance, the S.O.S for Seniors’ telecare system, and the Problem Reporting System “Let us Fix It” [

27]. Many services available to every citizen are operated using the IoT system. With the available data and analysis, city authorities are able to develop their environmental program to focus more on sustainable consumption of resources and monitor the economic assets of the city and changes in the labor market, such as monitoring of the increase in employment, especially in priority industries and sectors; growth of investment expenditures and payroll; and the entrepreneurship boom.

Participation and implementation of the “right to the city” in practice support the identification of the Lublin community with the city. Many top-down and bottom-up activities have been initiated in recent years; for example, the civic budget, the first green civic budget in Poland [

99], the “Walkable Lublin” initiative under the 2014 Year of Jan Gehl and its continuation to improve public spaces for pedestrians and people with disabilities [

100], the Foresight Lublin 2050 survey and the citizens’ panel devoted to working out solutions to improve air quality in Lublin or the future of the EU (within EUROCITIES).

To achieve evolution to a Human Smart City, city administrations must build trust with the community and test cooperation and citizen participation. To do this, it is important to identify the various needs of the community through citizen involvement [

10]. This is crucial in the context of building the city’s vision and development strategy. Lublin has successfully met this challenge. In 2018, the Foresight Lublin 2050 survey was conducted, which is a unique example of pre-strategic measures. On the basis of surveys conducted among many stakeholders, experts developed four scenarios ((1) Open Mind; (2) Digital Senior; (3) Analog Diversity; (4) Closed Gate) for the city’s development until 2050, which included the use of smart solutions and tools. The novelty is that risks were also taken into account, including the foreseen conflict in Ukraine. It is worth mentioning that this scenario was used by decision makers, who prepared appropriate tools for the refugee crisis in 2022. Thus, the city and its structures were fully prepared for the migration wave.

The culmination of participatory activities in Lublin was the enactment of a new strategy for the city’s development until 2030, in which nearly 15,000 residents and hundreds of experts participated (due to the COVID-19 pandemic, work on the strategy and consultations with stakeholders were also conducted online). It was one of the most advanced strategic planning processes in Europe, realized in the most sophisticated strategic–participatory models. The project was implemented within the framework of the Smart Human Cities program and is a unique example of effective inclusion of various stakeholders in shaping the future of the city in accordance with the principles of Smart City 3.0.

4.6. Main Factors of Development of Lublin as a Smart City 3.0 and 4.0

The analysis of the external and internal development factors of Lublin which facilitated the creation of ecosystems based on the principles of Smart City 3.0 and 4.0 is composed of numerous elements which connect people, the economy, the environment and technology. The external factors primarily include accession to the EU and the possibility of using EU funds and solutions and, on the other hand, the opening of labor and trade markets, whereas the most important internal factors are those related to the intensification of contacts in the business sphere; the internationalization of higher education; the creation of new strategic thinking about the city, its inhabitants and resources; and engagement of stakeholders in the creation of Lublin’s future (

Table 3).

4.7. Smart City Ecosystem Model

Analyses of the drivers, processes, policies and activities which facilitated the creation of ecosystems based on the principles of Smart City 3.0 (and partially 4.0) led to the formulation of a holistic Smart City Ecosystem Model (SCEM) (

Figure 5). The stages described below provide a clear understanding of its essence.

As indicated above, for a long time, Lublin, like many post-socialist cities, was not able to recover from post-transformation shock. The city’s developmental trajectory was complicated and can be divided into several stages corresponding to particular components of the model distinguished in

Section 3.1,

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3,

Section 4.4 and

Section 4.5.

Dynamic development processes triggered by the change of the paradigm of thinking about the city (2007), initiated and coordinated by the city, resulted, on one hand, in the mobilization of the inhabitants and civil servants in connection to political changes in the city and placing the emphasis on developing the cultural sector. On the other hand, it led to the economic opening in connection with the establishment of the Special Economic Zone in Lublin. Since then, all the activities within the city have been branded with the “Lublin—City of Inspiration” trademark, which increased their recognizability in Poland and abroad. These initiatives and actions became the basis that was developed during the participatory process of developing the Lublin 2020 strategy.

The development of the Lublin 2020 strategy, which, in many of its solutions, preceded the later selected strategic documents in Poland, was a turning point in establishing a broader framework of cooperation between the municipality with external stakeholders and their involvement in the process. Apart from that, the analyses accompanying the development of the strategy led to the formulation of Lublin’s smart specialization, which preceded the 3S of the Lublin voivodeship and Poland’s smart specializations by several years.

Thanks to stakeholders’ input and designation of the smart specializations, Lublin’s directions of economic development were set in a structured framework. The city effectively engages companies and universities in the creation of new, innovative entities and the development of ‘smart’ clusters created based on smart specializations, thereby strengthening business ecosystems.

Engaging the citizens, academia and, more recently, businesses in various aspects of the city’s life and including them in cogoverning contributed to a snowball effect which fostered the establishment of further interactions and activities (often bottom-up). As a result, it laid the foundations for the formation of an ecosystem of stakeholders in a quadruple helix framework.

Lublin introduced smart governance to improve the quality and accessibility of public services, increasing public participation in decision making. In line with the Smart Human City principles, the city uses many sophisticated technologies to connect and engage various stakeholders and motivates communities by stimulating and supporting their collaboration efforts, increasing the wellbeing and quality of life of citizens.

Municipal institutions are carrying out many activities, initiatives and investments tailored to global trends. Implementation of dedicated Smart city 4.0 solutions improved the quality of life of citizens, boosted economic development and provided environmental benefits.

The city initiates and coordinates many actions related to enhancing business ecosystems (e.g., directed at acquiring new investors and promoting entrepreneurship) and fostering stakeholder involvement. Additionally, a broadscale process of internationalizing many sectors of the economy and science is being conducted. Strong leadership has contributed to the growth of interconnections within the Lublin Functional/Metropolitan Area.

These processes led to the entrenchment of an ecosystem of stakeholders and competitive business ecosystems that strengthen human capital and sustainability, as well as providing a strong foundation for the development of an effective smart city ecosystem.

It needs to be stressed that these actions are part of the innovative aspect of the implementation of Smart City policy based on a number of initiatives undertaken as part of the city’s development strategy. Their success was determined by the factors which have already been pointed out, i.e., the integration of urban policies, adopting a clear strategy of brand building as well as an approach mainly based on the city’s and citizens’ needs [

3]. To this, one may also add the formation of an ecosystem of stakeholders engaged in the life of the city, who actively participate in shaping the city’s future, business ecosystems developing around the ‘smart’ clusters, as well as responsible leadership.

We are entitled to attempt to formulate the following model for two reasons. First, in our opinion, the presented generalization is justified, because Lublin is one of the medium-sized cities from CEE countries which underwent socio-economic transformation utilizing and efficiently combining a number of development paths characteristic of post-socialist cities [

33,

101,

102,

103,

104]. Second, due to the concentration of various development challenges and different sophisticated ways of solving them, the example of Lublin may contribute to a better understanding of the essence of development problems in other peripheral cities which apply smart tools and processes to build their smart city ecosystems [

22,

25]. As can be seen from the example of Lublin, the implementation of this model leads to sustainable economic growth and to an increase in the quality of human capital. It also helps to effectively manage development processes and can therefore be considered an optimal model for smart city management [

5,

12,

72].

5. Discussion

The challenges faced by the peripherally located cities that have experienced the negative effects of political and socio-economic transformation are still among the current themes addressed in the literature [

103,

104]. Although at first glance, Lublin’s developmental path is similar to the trajectory of other peripherally located cities, such as Oulu in Finland, or the cities in southern Italy [

105], Lublin’s example, as demonstrated in this study, is unique in comparison. Being aware of the limitations of this study, we argue that in addition to nationally determined differences [

106] and trajectories of population changes [

107], the pace of post-socialist transition and the scale-dependent specificity of socio-demographic, economic and spatial changes [

33,

104], there are other factors which contribute to building the capacity of post-socialist peripheral metropolises. The example of Lublin demonstrates that, apart from a dynamic and often unpredictable character of a socio-political transition, there are explicitly city-specific internal and contextual conditions which impact the developmental trajectory of a given center. Above all, these include the skillful formation of an ecosystem of stakeholders and implementation of smart solutions (from smart governance to smart specialization) on a managerial and operational level. This inspires activities and initiatives that strengthen metropolitan functions connected with, among others, the intensification of international contacts in the business sphere, the internationalization of higher education institutions, as well as, ultimately, planned creation of a brand that is recognized domestically and internationally, initiating cooperation within a Functional Urban Area and Metropolis. It should be noted that these activities are part of the innovative aspect of the implementation of smart city policy, which is based on a number of initiatives undertaken as part of the city development strategy [

18,

57,

71] and evidenced smart specialization [

61]. It forms the foundation for diverse economic transformations [

66,

67].

Nevertheless, it is important to note the issue of leadership and the role of the local authorities in the coordination of developmental processes [

16]. Essentially, there are two contrasting approaches discussed in literature on the topic [

12]. The first points to the necessity of making the right policy choices and implementing them in an effective manner within the existing administrative structures [

43]. The other emphasizes that the role of city administrators should be to develop support mechanisms to deal with a variety of problems [

1], which makes the authorities an inactive participant in the stakeholder ecosystem. However, they still play a key role in connecting organizations across the entire city [

108]. Our research combines these two approaches and proves that city authorities should, on the one hand, strengthen the capacity of municipal systems to deal with diverse problems by, among other things, initiating and coordinating processes within the city. On the other hand, they should serve as the link connecting active stakeholders and play a key role both in the initiation of activities and the consolidation of those organizations in the entire city which have common goals and complementary skills. This is a way to meet one of the most crucial challenges currently facing local governments in Smart City 3.0 and 4.0 [

10,

11]; that is, basing a city’s development on the creative participation of its inhabitants.

The key to success in this process is smart governance, and although the debate on this matter is still in its early stages [

57], the results of our study make it possible to indicate the factors which are responsible for it. In principle, they are compatible with the term defined by Meijer et al. [

12], although conscious, consistent, responsible and committed leadership, a participatory approach to city management and co-determination of the city’s resources and shaping structures of cooperation necessary to aid the development of intelligent cities through creative bureaucracy and urban infrastructure which serves both the inhabitants and the administration, as well as the ability to initiate cooperation within the ecosystem, come to the fore. Our research indicates that it is also important to adapt various business and management models to the city’s advantage, which enables the creation of a beneficial social and investment climate for smart cities. At the same time, one must notice that such efforts require new modes of multimodal management, both on a supra-regional level and in relation to their integrated internal development and relationship with the neighboring municipalities within the functional (2015) and, currently, the metropolitan area (2022). This allows better direction of the mode of planning and policy implementation by integrating it and applying it to supra-local needs. A practical implementation of this claim is the currently consulted Lublin Metropolitan Area supra-local development strategy, which is an example of an integrated strategic planning document setting common development directions and goals for the entire metropolitan area. Another example is the Lublin 2030 Strategy, adopted in 2022, in which the “Metropolis” development axis is one of the five leading ones.

An important aspect of smart governance is the cooperation between various stakeholders who actively participate in the collective decision-making process in order to create and implement public policy, as well as in managing public programs or assets [

48,

77]. While engaging stakeholders may play a key role, this area is still relatively poorly studied [

109]. Fernandez-Anez et al. [

49] suggested that understanding stakeholders’ views and aligning them with future strategies can provide a holistic view of smart city management. This study fills in this gap and indicates that including local communities and entities in the decision-making process with the proper utilization of social and institutional capital, as well as the potential of the municipality, is enormously significant for developing a multilateral relationship between public and private entities. This, alongside the inclusive and mobilizing policy of the city, leads to the creation of an ecosystem of stakeholders and translates to a more effective and informed governance of the city by way of easing effective cooperation of the authorities with social and business leaders. Moreover, in this study, we have demonstrated that it is crucial to work out mechanisms of collective thinking and cooperation of four groups of stakeholders (the city, entrepreneurs, academia and civil society), which are characterized by distinct traits and motives for action (

Figure 4). Additionally, effective engagement of stakeholders results in them sometimes assuming the role of an initiator and coordinator of the activities conducted in the city; thus, they actively participate in planning its development. As the example of Lublin proves, this is an integral element of Human Smart City success.

In Lublin, the Human Smart City approach is gaining tremendous support from the city government, which is influencing more effective responses to key challenges such as low-carbon strategies, urban environment, sustainable mobility and social inclusion through a more sustainable, holistic application of technology. This is in line with European trends [

10]. In addition, Lublin is effectively leveraging modern technologies, data and stakeholder engagement to build sustainable development, improving environmental quality and carbon neutrality, and thus creating a more resilient Smart city 4.0. All activities, including those related to spatial policy, are being conducted with respect for the environment and the exploitation of its potentials (landforms, greenery) for many years and are part of the city’s development paradigm. They are supported by activities concerning the planning of a coherent and diverse transportation system throughout the metropolitan area (new SUMP 2022), or the implementation of 15 min city solutions. These are very strongly highlighted in the Lublin 2030 Strategy, and are also currently being tested in Lublin’s districts through the development of sustainable neighborhood strategies. All these activities and initiatives are aimed not only at improving the quality of life of citizens, but also at fostering sustainable communities.

Smart City 3.0 and 4.0 projects, which undoubtedly include activities undertaken in Lublin, foster the creation of versatile urban ecosystems as well as solving coordination problems within the entire smart city ecosystem. A residential and business-friendly environment can attract and retain people, companies and investments that are fundamental to economic development. This depends not only on a flexible normative and legal framework, but also on a strong network between the various stakeholders in this ecosystem. In addition, a city conducive to the creation of clusters, start-ups as well as new sectors and industries, collaborative spaces and using innovative tools developed with partners from science and business communities, has already achieved the effect of synergy in the entire urban ecosystem. Lublin successfully engages stakeholders in the effective deployment of modern technologies, diverse sets of open data, and the achievement of climate targets and sustainability goals.

This is also connected with another important issue concerning the resolution of coordination problems in the entire smart city ecosystem. As the city’s highly sophisticated and diverse functions are matched in a democratic urban community by a wide range of local and supra-local agents with diverse and sometimes opposing interests, policy decisions are the result of input from different interest groups with different levels of power. Diversity is an important asset of cities, as long as the various interests of the particular stakeholders are harmonized with the benefit for the entire community [

31]. The issue is how to work that out. Lublin’s example shows that it is possible to achieve through a long-lasting and consistent policy of dialogue with engaged inhabitants and other stakeholders, which is institutionalized and depoliticized. This enables the development of the city to be based on the creative engagement of its citizens.

In light of all these factors, the SCEM defined in our article seems to respond to all of these challenges and constitutes a genuine contribution to the discourse on the optimal models of governing smart cities [

12,

49] in the stream of smart governance [

6] and the creation of smart city ecosystems [

22]. In order for the model to function, it is necessary to arrange all of its aspects in an integrated and comprehensive manner to achieve synergy.

Lublin’s experience can be applied to other cities implementing smart city strategies, just as Lublin should benefit from selected ‘smart’ tools developed and successfully implemented in other urban centers. In terms of creating innovative business ecosystems, the experience of Helsinki, in the area of initiating and coordinating technology clusters, with a very strong component of cooperation on the local government–university–business line, is interesting [

110]. This resulted in the creation of innovative enterprises, including in the open innovation model. However, the models used in Helsinki were not immune to weaknesses, such as the lack of diversity in technology base. This model succeeded in Lublin due to the focus on increasing the number of students in IT majors and attracting new technology investors as part of the IT sector ecosystem project coordinated by Lublin (

Table 2). A very good benchmark for Lublin in the area of implementing a comprehensive smart city model are solutions from Vienna. The experience of that city shows the adverse impact of social polarization and unbalanced stakeholder involvement in the implementation of smart city strategies [

49]. Potentially, this could be a barrier to the implementation of Lublin’s strategy in years to come, especially in the situation of successive waves of refugee influxes and the associated socio-income polarization.

6. Conclusions

This study focuses on presenting the developmental path of a peripherally situated post-socialist city which integrates state-of-the-art smart governance solutions and implements them on a strategic and operational level. It details the process of devising a developmental strategy and making strategic decisions, as well as the engagement of various stakeholders in the decision-making process. Moreover, we have demonstrated the benefits of designating directions of economic development stemming from defining and implementing smart specialization, skillful adaptation to global trends, focused internationalization, building a city brand as well as the role of municipal authorities in the initiation and coordination of these sorts of activities. Additionally, the process of forming stakeholder ecosystems as well as competitive business ecosystems was analyzed; together, these became essential elements of the Smart City 3.0 and 4.0’s success. All of these components have been reflected in the Smart City Ecosystem Model. It should be emphasized that, as a result of the implemented smart city strategy, Lublin has developed not only an innovative business ecosystem, but also a strong culture of cooperation among all stakeholders and multifaceted projects and activities of various partners.

The example of Lublin may be the source of numerous observations, both for decision makers in peripheral cities and metropolises, as well as decision makers at various other levels in developing and developed countries. Municipalities should, first of all, apply a systemic approach to the coordination and steering of the development of the municipal ecosystem, entrusting tasks to external stakeholders (in the model of providing access to resources without the necessity of owning them). This means introducing multilevel governance engaging all groups of cooperating stakeholders (quadruple helix). The key element is also the process of elaborating a city strategy and creating a city brand. This allows creative inclusion of the inhabitants and other stakeholders within discussions on the future of the city. Some of the people and institutions engaged in this process will later be productively engaged in the city’s development, becoming its ambassadors. At the same time, it is crucial to take advantage of global, national, regional and local developmental impulses and adapt all of the solutions to the unique assets of the city. These may be selected elements connected with the economic specialization, as well as choosing either contextual niches of the global market or properties and dimensions characteristic of a smart city.

The uniqueness of Lublin’s approach to the process of building and implementing development strategies is not only due to the abovementioned processes. Central to the analyzed model was the key role of the city government, as an inspirer, creator and coordinator of policies implemented in Lublin in a model of advanced cooperation and sharing of resources with stakeholders. The second element became the institutional continuity of activities implemented over many years, thanks to the favorable political climate in the city, and the third was the implementation of hundreds of policies in all areas of the city’s functioning and its ecosystems. These activities can be described as an integrated mobilization of decision makers and stakeholders.

These successes are followed by certain development problems concerning the coordination of numerous current activities, as well as future ones. Like a well-functioning corporation, Lublin has reached a critical point. This concerns both the processing and adaptation of new solutions and the acquisition and processing of a growing amount of sophisticated data. Another big challenge for implementing Lublin’s strategy is the ongoing armed conflict in Ukraine. Despite the city’s good preparation for the refugee crisis, there are many risks that may limit the effectiveness of the implementation of city policies. The key one is the lower propensity of business, both Polish and foreign, to invest in eastern Poland, which has implications for building the city’s innovative potential.

The city’s new development strategy for 2030 clearly emphasizes the different nature of the challenges facing the city over the next few decades. The key factor among them is the transition from a model of rapid extensive growth to a model of smart growth, with constant adaptation to new global and regional urban development conditions: the energy and climate transition, changes in global value chains, new geopolitics in Europe or the inclusion of youth in urban life. The latter challenge, for instance, will be materialized through the nomination of Lublin for the European Youth Capital in 2023.

In general, smart city policies are not broadly discussed in the literature [

111], and thus our study allows us to create a framework which may assist public and/or private decision makers in the implementation of an effective policy, as well as its practical application in governing a city. The results of our analysis revealed a set of drivers of smart city development. We have proven that implementing strategic thinking adapted to the challenges and problems of specific cities, even those that are peripheral and socio-economically disadvantaged. Using existing potentials and niches with the ability to involve different stakeholder groups in the process and creating the right business climate yields the desired results and allows shaping of an efficient urban ecosystem that effectively supports the development of Smart City 3.0 and 4.0. Tracing the entire process of developing an ecosystem and the strategic choices made not only by the authorities, but also by the particular stakeholders which accompany it, is undoubtedly a significant contribution to the discussion on smart governance. Responsible leadership and wise management are the catalysts in this process, as are the use of state-of-the-art tools and participation in regional to global networks. Developing these themes has allowed us to create an implementable model of a smart ecosystem for a peripheral metropolis that creates a new multidimensional smart city policy framework. This model can be fully or partially adopted in cities with metropolitan/Smart City 3.0 and 4.0 ambitions. This comprehensive effort to provide a clearer picture for the creation of a stakeholder ecosystem may play an important role in the design and implementation of a smart city strategy. Therefore, this study contributes both to the theory and practical implementation of smart cities. It may also be a point of departure for conducting studies on implementing strategic thinking, the processes which accompany it, as well as the effects in the form of the formulation of urban ecosystems. That, in turn, may provide a basis for expanding the model presented in this study.