Abstract

Waste-to-energy (WtE) is national policy. From this view, WtE technology has been promoted. Many WtE projects in Thailand were unsuccessful due to several problems. This research aimed to analyze the key barriers impacting the WtE project development in Thailand. The Interpretive Structural Model (ISM) and Cross-Impact Matrix Multiplication Applied to Classification (MICMAC) analysis tool have been used to evaluate the barriers that significantly in the development of WtE projects. In this study, WtE projects focused on electricity power generation in order to correspond to the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) target and power purchase agreement constrain of the government. The barriers were obtained from six sections consisting of social issues, environment, national policy, technology, economy, and project management. From six sections, there are 20 barriers that were identified. The ISM and MICMAC analysis showed that the key barriers impacting the WtE projects development were insufficient amount of waste and poor waste management planning. These two barriers correspond with many studies in Thailand and other countries. The project developers or investors must take these two barriers and other barriers with less impact mentioned in this study into account before developing the WtE projects in Thailand.

1. Introduction

The world is building up more waste than ever, and waste generation will increase by 40% and 19% of daily per capita for developing and developed countries [1]. In Southeast Asia, seven key countries (i.e., Malaysia, Myanmar, Indonesia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) have a combined population of more than 630 million people. In 2030, municipal solid waste (MSW) generation rate is expected to be 1.6 kg per person per day or around 400 million tons a year [2].

The National Economic and Social Development Plan of Thailand mentions that community energy is the country’s government policy for sustainable energy development. The WtE concept is a solution to meet the policy requirement, both solving energy problems and solving waste problems [3]. Complete community waste management from the start of waste to final disposal and recycling waste should proceed as much as possible. The solution, therefore, requires comprehensive and concrete waste management, sorting, recycling, and efficient disposal. Most importantly, it must be emphasized that the community or the locality can have self-management. The technology used must be the technology that is suitable both technically and economically [4]. It is very important to be friendly to the environment. The management approach must be balanced and have sustainable development among the economy, society, natural resources, and environment [5,6].

The community solid waste disposal site in the Thailand 2020 report of Pollution Control Department (PCD) revealed that, from 2016 to 2020, the community solid waste disposal sites and community solid waste transfer stations had 3262 locations. In this number, 2274 sites are still open for service, representing 70% of the total number. Additionally, the rest of the 30% of community solid waste has closed or stopped operations; the total number of these sites is 989 places [7]. As mentioned above regarding the national policy on WtE, the Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency, Ministry of Energy, Thailand, then has set up the target of producing electricity from waste to 975 MW in 2037, which is a part of Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP: 2018–2037) [8]. As we know, many projects in the WtE projects were unsuccessful due to several problems. For example, an insufficient waste supply to generate electricity throughout the year impacts the project to proceed. Some plants have a conflict in waste scramble due to the waste’s limitation, and some areas have a cost for waste management. The environmental problem is also a significant barrier to the WtE project, and it may breach the terms of the license and cause complaints from the people in the surrounding community [1,3,6,9,10].

According to the complicated problems of WtE project development in Thailand, this research aimed to analyze the key barriers impacting the WtE project development in Thailand. For reliability, the authors employed Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) and Cross-Impact Matrix Multiplication Applied to Classification (MICMAC) method to analyze the barriers, which are the most critical factor for the WtE projects and must be considered before the future development of WtE projects in Thailand. In this study, the WtE projects focused on electricity power generation in order to correspond to AEDP target and power purchase agreement constrain of the government [3,8].

The structure of this paper is as follows. After this introduction section, where the general information of WtE in Thailand and study objective is presented, it is followed by a literature review that presents important background related to this study and research gab. Materials and methods, a description of this study methodology, data, and variables used are then discussed, and it is followed by the results and discussion sections. Finally, it closes with the conclusions, limitations of the study, and future research guidelines.

2. Literature Review

2.1. WtE Technologies

WtE technologies convert municipal and industrial solid waste into electricity and/or heat for industrial processing or supply energy to the utility grid. The WtE plants burn waste in an incinerator at high temperatures and convert the heat to make steam for driving the steam turbine that creates electricity and/or direct use of the hot water [1,3,6,11,12]. The different methods to convert WtE are employed based on climatic environments, population, type of waste produced, and geographical conditions of the region. In the WtE process, there are many options used to treat waste and convert it to energy. Energy can be generated by treating MSW via energetic and non-energetic pathways. Recycling, reuse, and composting result from the non-energetic ways of waste management. Recycling means using materials, for example, plastic waste and metals, in order to make new products [6,13]. This aims to reduce the amount of waste that is sent to landfills. Additionally, this aims to prevent pollution. Composting refers to the biodegradation of economical and reliable waste disposal. It is widely used in developing countries. Pyrolysis and gasification are new technologies for WtE, and they are used in developed countries. During these processes, synthetic gas which is called syngas is produced. Syngas is composed of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane. They can be used for heating purpose and in turbines, engines, fuel cells, or boilers to generate electricity [14]. The WtE technologies are classified into three techniques, including thermal conversion, physical, and biochemical conversion techniques, as shown in Figure 1 [1,15]. MSW management has become a need in some developing countries, such as Thailand, especially in urban areas. On the contrary, developed countries try to handle the waste safely and dispose of them economically and technologically. For example, in England, sustainable waste management model using stock-and-flow has been proposed to improve resource efficiency and reduce waste from landfills [16]. The WtE technologies for converting WtE are anaerobic digestion, incineration, pyrolysis, gasification, and recycling [1,15,17].

Figure 1.

Types of WtE technologies.

2.2. WtE in Thialand

Thailand has had a long history of WtE projects with two main objectives. The first is to manage the problem regarding the amount of waste, and the second is to increase the electric generation from waste. Thailand’s MSW generation is about 1.13 kg per person per day [7,18,19,20]. Therefore, waste management tends to become more severe due to the increasing rate of population and the expansion of economic, social, and behavioral changes in consumption [21,22,23]. According to the Pollution Control Department (PCD) report in 2021, the MSW in Thailand including Bangkok, Chonburi, Samut Prakan, Nonthaburi, and Nakhon Ratchasima, which are the top five provinces that generate most of the MSW of the country. The amount of the country’s MSW occurring was about 25 million tons per year, or about 69,300 tons/day in 2020 [7,18,19].

The amount of waste that occurs in Thailand is as follows. The amount of waste is about 17,700 tons/day in the northeast, about 9100 tons/day in the south, about 4300 tons/day in the north, about 6000 tons/day in the east, about 16,600 tons/day in the central, about 3300 tons/day in the west, and about 12,300 tons/day in Bangkok [7]. Interestingly, Bangkok is only one city, but the amount of waste is higher than many regions in Thailand (around 18% from total). The amount of waste generated per person per day in Thailand is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3 showing the amount of waste generation and utilization.

Figure 2.

The generation rate per person of waste in Thailand [7,18,19].

Figure 3.

The amount of waste generation and utilization in Thailand [7,19].

For waste disposal, the method or technology used needs to take the elements and the properties of waste into account. It will change according to the climate, seasons, and economic behavior of life in each community/city, but the overview of waste in various provinces in Thailand still has similar elements and properties. However, waste in Thailand has very high humidity because the MSW contents are composed mainly of organic waste (63–68%) [3,10]. Thus, this property is theoretically more viable for biochemical conversion process than the other techniques. In European Union (EU) countries, biochemicals such as biogas produced from waste are part of the EU’s policy. There is a case study from Poland and Germany revealing that they both have similar agriculture and MSW properties. As a result, biogas plants are popularly installed. Nonetheless, most of biogas plants use waste from animal husbandry, not MSW [24].

However, based on the WtE supported scheme of the Ministry of Energy, the project economy is more important for investors rather than considering suitable methods [3,10]. By this sense, even this presented organic property is a disadvantage of waste utilization in the form of energy and fuel production. Therefore, the suitability of thermal technology is an exciting issue for producing energy from waste. Previously, the landfill was the preferred method, but nowadays, the areas for the landfills are not easy to find. Additionally, landfills cause pollution since there is wastewater from the garbage heap affecting surface water and underground water. Moreover, there is a bad smell from the garbage heap that disrupts the villagers’ livelihoods [25]. From the above-mentioned problems, it can be said that incineration is inevitable. Therefore, the right technology needs to be chosen in order to have the most negligible impact on living organisms and the environment, and the most significant benefit from waste is a leading alternative. Nowadays, waste disposal technology has been developed, and it can convert waste into energy. The advantage of producing electricity from waste is that WtE processes are effective in combating climate change arising from global warming. It is possible to generate renewable energy and reduce carbon emissions [3,26]. Additionally, this helps to reduce waste disposal problems. However, there are some limitations, such as opposition from neighboring communities. Additionally, some technologies are costly, and there is a cost for proper waste management before it is converted into energy. It must also have appropriate technology for dealing with dust, fumes, and substances generated from incineration. Additionally, there are restrictions on ownership of waste; for example, investors who set up a power plant may not be the owner of a waste disposal site.

2.3. ISM and MICMAC

ISM have been found in the Scopus database in over 5000 documents. Since 2007, there had been an exponential increase of using this technique from 46 documents to 1200 documents in the year 2020. With major contributions of articles from India, China, the USA, the UK, and Iran, ISM technique is being used in many disciplines’ subjects such as business, engineering, computer science, decision science, environmental science, social science, and so on. ISM supports in creating models of the variables, resulting in the existing interrelationship structure among them. This technique helps a group of people or decision makers to debate and share their knowledge and achieve consensus on the relationships among the variables. The participators can share their ideas without any knowledge of mathematical complexity involved in the underlying steps. The ISM process does not add any information but brings in structural value. MICMAC supports in classification of the variables into one of the four categories, namely dependent, independent, linkage, and autonomous variables. ISM together with MICMAC becomes a strong tool to visualize the structure of variables along with the interrelationships among them [27].

Most countries, both in developed and developing countries, have problems about waste management implementation. These problems include technical and non-technical problems depending on each country’s contexts as reported in the literature mentioned above. In order to solve those problems, the exact root cause or barriers need to be found out since the beginning before implementing the solution. WtE project development in Thailand is also the same. To succeed in an implementation, the key barriers should be identified. From the literature, the ISM and MICMAC techniques are the most suitable tools for investigating and pointing out the priority problems of project’s unsuccess that need to be considered before developing the WtE.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Development of ISM for WtE Project in Thailand

This research studied the barriers that impacted the failure of WtE projects development in Thailand. The barriers mentioned in this study were gathered from the related literature and documents from reliable agencies and experts’ experience in the WtE field. All barriers were analyzed to determine the impact of the barriers, which influenced the unsuccess of WtE project development in Thailand by using ISM and MICMAC analysis. In addition, the structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM) was developed to analyze the obstacles affecting success and failure. Microsoft Excel software was also used in ISM and MICMAC process. The methodology of this research is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The ISM structural flow of this research.

The research’s objective was to analyze the barriers that impacted the success of WtE projects in Thailand. In this study, the qualitative methodology was most suitable. ISM with MICMAC analysis was employed. Although ISM has been used for a few decades, it is still the most widely used research technique. It is more beneficial than other techniques since it supports both the non-numeric and numeric research models. Besides, it is more convenient when explanation, investigation, and analysis are required through conducting interviews, questionnaires, and a literature review. Therefore, this technique suits this present research [27,28,29]. This research also used a systematic literature review of WtE projects and gathered barriers from the experts in WtE development in Thailand for the preliminary idea and barrier identification. ISM is an accommodating modeling method, and it is a tool used for approaching complex issues carefully, using logical thinking, and then distributing the results. It can be said that it is better than other easy-to-understand methods. The ISM process is composed of the following. (1) Identifying critical variables for this work was the barriers that impact WtE development. (2) The structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM) was then created in order to identify the relationships among barriers. (3) A reachability matrix method was developed. (4) In the following step, testing was transitivity. (5) Deriving model levels were set by employing the reachability matrix. (6) The relationship was translated, and the ISM model was drawn. (7) Finally, the inconsistencies were reviewed and revised accordingly [27,28,29].

3.2. Identification of the Critical Barriers to the WtE Project

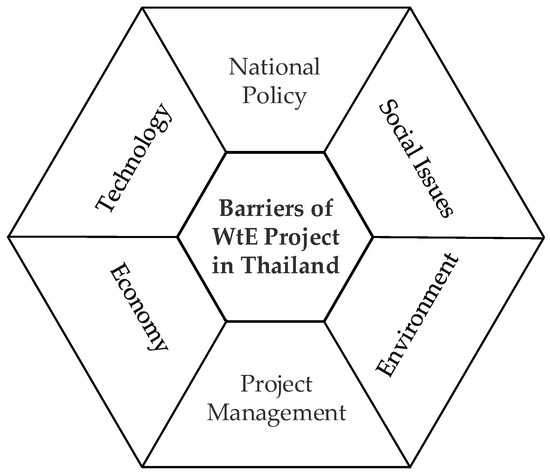

There are critical barriers which affect the success of WtE project development in Thailand. According to the literature review, study all barriers were classified into six sections as shown in Figure 5 [1,5,6,7,9,10,12,15,16,17,19,21,22,23,25]. The 20 barriers were gathered from the related literature, reliable agencies’ reports, and experts’ experience in the WtE field. The sources of barriers of this study are shown in Table 1.

Figure 5.

The six sections barriers classified.

Table 1.

Sources of barriers of this study.

The critical barriers are related to WtE project development in Thailand, and they can be divided into six sections, consisting of social issues, environment, national policy, technology, economy, and project management. The social issues, environment, national policy, and project management are general aspects that should be taken into account in any WtE project. The aspect of technology was chiefly selected in order to determine the proven capacity of the WtE options via the reference plants. Electrical efficiency is used to assess the performance of the WtE options according to electricity generation and the power production in order to quantify the amount of energy generated by a WtE technology. The economic aspect was the next aspect to determine the cost required to install a WtE technology and its operation cost. The reference plants’ specific capital and operation costs were then investigated using the literature review. From Table 1, this research compiled various problems and summarized them into 20 barriers that affected the development of the WtE project in Thailand. A total of 20 barriers are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Keys barriers to the WtE project development in Thailand.

3.3. Development of SSIM

The Structural Self Interaction Matrix (SSIM) is the direction of the relationship between barriers; 20 barriers in this research were compared between column and row of each parameter. For analyzing the barriers to developing SSIM, the following four characters were used to denote the direction of the relationship between barriers (i) and (j): [27,28,29]

V: Barrier i will help to achieve barrier j.

A: Barrier j will help to achieve barrier i.

X: Barrier i and j will help to achieve each other.

O: Barrier i and j are unrelated.

For creating an SSIM relationship table with each variable arranged in rows and columns, apply four symbols (V, A, X and O) instead of a barrier relationship [37]. The authors created the SSIM table, which is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM-V, A, X, O) of this research.

3.4. Reachability Matrix (RM)

In this study, 20 barriers influencing the development of the WtE projects in Thailand were related to the establishment of social issues, environment, national policy, technology, economy, and project management. The SSIM (Table 3) is able to create a Reachability Matrix (RM) relationship table by removing the associated SSIM comparisons from symbols to numbers instead. The 20 barriers were compiled based on reviews from experts in the field of WtE in Thailand. The cause–effect relationship of each barrier was accomplished, and all the data were used to create the RM relationship as shown in Table 3. The reachability matrix acquired from the SSIM provides the linkage of elements in the second form. The relationships represented by the symbols V, A, X, and O in SSIM are replaced by binary symbols of 0 and 1 using the following directions [38,39,40,41].

If i, j in SSIM is V, then i, j entry in the reachability matrix converts 1 and j, i as 0.

If i, j in SSIM is A, then i, j entry in the reachability matrix converts 0 and j, i as 1.

If i, j in SSIM is X, then i, j entry in the reachability matrix converts 1 and j, as 1.

If i, j in SSIM is O, then i, j entry in the reachability matrix converts 0 and j, i as 0.

As a result, the reachability matrix can be developed as previously explained. The reachability matrix of each barrier is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reachability Matrix (RM) relationship symbol.

3.5. Level Partition of Barriers

According to the RM of barriers in Table 4, this work involves identifying a reachability set and an antecedent set for each barrier, as those emerged from the existing RM (Table 4). The reachability set of barriers includes the barrier itself and every other barrier that it affects (“V” or “X” relationship). On the other hand, the antecedent set includes the respective barrier and all the barriers that impact it (“A” relationship). The intersection set comprises the common barriers in these two sets.

The level of barriers was determined after completing the RM matrix (Table 5). In this step, intersections and reachability sets were matched. The complete matching was identified as level I and held the top level in the hierarchy. The next levels were then identified later on. In this study, for example, as shown in Table 6, for the barrier B2, the intersection and reachability sets were matched. This is similar to the barriers B5, B7, B11, B12, B17, and B19 that were obtained at level I. Level II components were obtained by eliminating the level I barriers and repeating step until no more barriers remaining as shown in Table 7 (Level II) and Table 8 (Level III) [29,37,38,39,40,41].

Table 5.

The reachability matrix of this research.

Table 6.

RM level partition matrix I.

Table 7.

RM level partition II.

Table 8.

RM level partition III.

Based on the RM (Table 5), the barriers were brought to arrange the “level partition” of the critical barriers of Thailand’s WtE project development. The 20 critical barrier factors were divided into three groups of variables: reachability set, antecedent set, and intersection set as mentioned above. Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 present the existing level partition of barriers of this study.

3.6. MICMAC Analysis

The RM relationship data from Table 5 again were categorized into the elements by MICMAC method by calculating the values of driving power and dependence power of barriers. The MICMAC entails a graphical representation of the barriers according to their driving and dependence power in four clusters of variables: autonomous, dependent, linkage, and independent. The four MICMAC quadrants are the following. Quadrant 1 was autonomous factors. They were weak dependence power and weak driving power. Quadrant 2 was dependent factors which had strong dependence power but weak driving power. Quadrant 3 was linkage factors that had strong dependence power and strong driving power. Quadrant 4 was independent factors that had high driving power but weak dependence power [38,39,40,41]. Figure 6 illustrates the classification of the barriers into these four quadrants to evaluate the employment of SSIM practices. The authors employed this figure to gain further insight into the ISM-based model and evaluate the barriers from the implementation perspective. It involved classifying the identified barriers based on their driving and dependence powers, which the authors determined in the final reachability matrix.

Figure 6.

Dependence power vs. driving power by MICMAC analysis.

Figure 6 shows the classification of the critical barriers according to the quadrants of MICMAC analysis as follows. Quadrant 1 was an autonomous group consisting of poor waste management planning (B3). Quadrant 2 was the dependence group. In this study, there were no variables that belonged to this quadrant. Quadrant 3 was linkage drivers. They were variables that caused system instability and could also be classified into independent variables or dependence variables. It is because they could affect other variables and could be affected by other variables as well. In this present research, the most of variables belonged to this group consisting of B1, B2, B4, B5, B6, B7, B8, B9, B10, B11, B12, B13, B14, B15, B16, B17, B18, B19, and B20. Additionally, Quadrant 4 was independent drivers. In this study, there were no variables that belonged to this quadrant.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Critical Barriers to the WtE Project in Thailand

This research is the study on an ISM technique and MICMAC analysis aiming to evaluate the barriers that significantly impact the development of WtE projects in Thailand. The ISM is a complex structural model, and it employs drawings and mathematical comparison in order to resolve complex numerical and non-numeric problems. It is a set of direct and indirect analysis that includes an interactive and structured learning process which is related to the issues needed to be solved, and it is used to describe the meaning of each parameter’s link to the research question. The barriers can be divided into six sections: social issues, environment, national policy, technology, economy, and project management. Twenty barriers influencing the development of Thailand’s WtE project as mentioned in Section 3.2 result from all these six sections.

4.2. Results of ISM Analysis for WtE Project in Thailand

Regarding analyzing the cause–effect relationship of barrier factors using structural modeling ISM and including hierarchy relationship structure as described in Section 3.5, it was found that the highest levels of barriers that were affecting WtE project development in Thailand were an insufficient amount of waste (B1) and poor waste management planning (B3). The issues of B1 and B3 were the most impacting factors in the ISM analysis, consistent with the results reported by credible agencies in Thailand related to the projects [3,7,9,10] and experts’ comments. It was revealed that the main problem in project development was the inability to keep the plant running year-round due to the amount of waste, which would later match the problem of B1 and B3. The level partitions of ISM analysis of this research are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The level partitions of this research analysis.

In level III of the ISM analysis, there are only two barriers (Table 8): the insufficient amount of waste (B1) and poor waste management planning (B3). These two barriers are the most important for investors or developers who want to invest in the WtE projects in Thailand. They must consider barriers B1 and B3 before making their decision. The MICMAC analysis revealed that only B3 fell into Quadrant 1, and others fell into Quadrant 3. Critical barriers intersect with B1 consisting of B2, B8, B9, B11, B12, B13, B15, B16, B17, and B19 as presented in Table 5 (RM level partition matrix I). Critical barriers intersect with B3 consisting of B8, B11, B12, B16, B17, and B19 as also presented in Table 5. The results of the RM showed that when all the data were arranged in the level partitions of ISM analysis, they were grouped in Level II (Table 6). There were remaining only two variables: wrong selection of location (B15) and environmental problems (B16). The parameters in Level II (B15 and B16) had less impact on WtE project development compared to the effects in Level III.

4.3. Results of MICMAC Analysis for WtE Project in Thailand

In this research, according to Section 3.6, 19 barriers fall in Quadrant 3, a linkage group with strong driving and dependence power. The barriers in this group consist of 19 barriers, as mentioned in previous section, which can be divided into six sections: social issues, environment, national policy, technology, economy, and project management. The 19 barriers fall in Quadrant 3 consisting of the social issues section which consists of insufficient amount of waste (B1), quality of waste for electricity generation (B2), people’s resistance to separating their waste at home (B4), competition for waste management in the area of responsibility (B5), insufficient public education for the community (B12), limited community participation (B13), and labor conflict (B14). The environment section mainly focuses on environmental problems (B16), such as air, water, and sound issues, and the problem of landscape and visual aspects (B17). The national policy consists of unsupported WtE policy (B19) and weak and inadequate regulation (B20). The technology section consists of the wrong selection of WtE technology (B6). The economic section consists of poor project cash flow management (B7), risk of slow economic development (B8), slow payback period (B9), poor information on the actual costs (B10), lack of financing mechanisms with attractive conditions for investors (B11), and a wrong selection of location (B15). The project management section consists of poor contract management of licensing (B18). From the results of MICMAC analysis, it was found that there were quite a lot of barriers linked into each other for the development of WtE projects in Thailand. It is because the ISM analysis showed that, in the six sections mentioned, the 19 barriers fell in the Quadrant 3. This quadrant has high driving power and dependence power or linked driver; all barriers which are falling in this area are severe problems, and there is a connection among the barriers. The 19 barriers must be considered, and the solution to improve needs to be found before the investors or project developers create a project on the WtE in Thailand. However, poor waste management planning (B3) falls in Quadrant 1. It is a dependence variable which has a high impact on WtE development. It is because, in the 19 barriers, if any occur, they will also affect B3 as well. Therefore, effective waste management should prioritize and act on these factors.

4.4. Disscusions of WtE Project in Thailand Barriers

The insufficient amount of waste (B1) and poor waste management planning (B3) are the critical barriers that must be taken into account before developing the WtE project in Thailand. Therefore, the project developers or investors must consider B1 and B3 before developing the WtE Project. MICMAC analysis results showed that 19 barriers were classified as linkage drivers (Quadrant 3), and only one barrier (i.e., B3) was identified as an independent group (Quadrant 1) as shown in Figure 6. A high-priority critical barriers are the two barriers (B1 and B3), classified into Level III of ISM level partition. The important barriers affecting the WtE development in Thailand are the insufficient amount of waste and waste management for the project because many barriers are linked to these two barriers (i.e., B1 and B3) which are the same as the research results concerning the WtE project in Thailand.

The research results corresponding with many studies in Thailand presented that the insufficient amount of waste is related to WtE projects selection, and the poor waste management planning is the most important factor in WtE projects’ success [3,7,9,10]. Compared with other countries, an insufficient amount of waste is also a critical issue in WtE projects’ sustainability [24], and problem of waste management planning is always an issue of both developed and developing countries [1,6,16,21].

5. Conclusions

The barriers in this study were obtain from six sections consisting of social issues, environment, national policy, technology, economy, and project management. From six sectors, there are 20 barriers that were identified. The ISM and MICMAC study showed that the key barriers impacting the WtE project development in Thailand were an insufficient amount of waste (B1) and poor waste management planning (B3). These two barriers should be considered before implementing the WtE projects. The ISM and MICMAC analysis is an effectively tool which can help for decision making of WtE. The ISM creates a complex structural model, and it helps to resolve complex numerical and non-numeric problems. ISM is used to describe the meaning of each barrier’s link to this research question. Together with MICMAC, it is a strong tool to illustrate the structure of barriers along with the interrelationships among them.

In order to succeed in WtE projects development in Thailand, the policy makers should reconsider and reformulate the WtE support program strategy. Promoting electricity generation from MSW with the intention to help reduce the amount of waste locally may not be achieved. Because of regulation, MSW cannot transfer across other areas of each local government’s responsibility. With this reason, most of WtE power plant projects are unsuccessful due to insufficient amount of waste in the project’s areas and also poor waste management planning. Strong waste management implementation from government and all stakeholders should be the first priority options to solve the problem of the amount of waste, and it is followed by promoting of WtE power plants. The limitation of this study is due to the ISM technique. This will be high performance when those who use are knowledgeable and familiar with interpreting the data. The interpretation of linkage can vary since it sometimes depends on the ISM users [40].

An insufficient amount of waste in the WtE power plant development is current country constraints. For future research work, finding of the key success of WtE under this context is expected, between the MSW (limitation from transfer across areas) and refuse derived fuel (RDF) (non-limitation of transfer across areas). Additionally, the key success of the projects of each option (i.e., MSW and RDF) should be investigated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J. and N.K.; methodology, N.J. and N.K.; software, N.J. and N.K.; validation, N.J., N.K., M.K. and P.T.; formal analysis, N.J., N.K., M.K. and P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.J. and N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.K., M.K. and P.T.; visualization, N.J. and N.K.; supervision, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and effort towards improving our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Khan, I.; Chowdhury, S.; Techato, K. Waste to Energy in Developing Countries—A Rapid Review: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policies in Selected Countries of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Mohanty, C.R.C.; Khajuria, A. State of Plastics Waste in Asia and the Pacific Issues, Challenges and Circular Economic Opportunities; Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan (MOEJ): Tokyo, Japan, 2020; ISBN 4-906236-94-4. [Google Scholar]

- Jutidamrongphan, W. Sustainable Waste Management and Waste to Energy Recovery in Thailand. In Advances in Biofuels and Bioenergy; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, U.; Zamenian, H.; Koo, D.D.; Goodman, D.W. Waste-to-Energy (WTE) Technology Applications for Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) Treatment in the Urban Environment. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng. 2015, 5, 504–508. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, E.; Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M. The Key to Sustainable Economic Development: A Triple Bottom Line Approach. Resources 2022, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Osman, A.; Farghali, M.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Recycling municipal, agricultural and industrial waste into energy, fertilizers, food and construction materials, and economic feasibility: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollution Control Department (PCD), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. The Community Solid Waste Disposal Site in Thailand 2020 Report; Pollution Control Department (PCD), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021; ISBN 978-616-316-641-8. [Google Scholar]

- Alternative Energy Development Plan 2018-2037 (AEDP 2018); Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency, Ministry of Energy: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. (In Thai)

- Yukalang, N.; Clarke, B.; Ross, K. Barriers to Effective Municipal Solid Waste Management in a Rapidly Urbanizing Area in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017, 14, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonpa, S.; Sharp, A. Waste-to-energy policy in Thailand. Energy Sources B Econ. Plan. Policy 2017, 12, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, D.; Aldás, C.; López, G.; Kaparaju, P. Municipal solid waste as a valuable renewable energy resource: A worldwide opportunity of energy recovery by using Waste-To-Energy Technologies. Energy Procedia 2017, 134, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabie, C. Converting, Municipal Waste to Energy through the Biomass Chain, a Key Technology for Environmental Issues in (Smart) Cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muri, H.I.D.I.; Hjelme, D.R. Sensor Technology Options for Municipal Solid Waste Characterization for Optimal Operation of Waste-to-Energy Plants. Energies 2022, 15, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, K.; Saini, K. Emerging Technologies for Waste to Energy Production: A General Review. Preprints 2021, 2021010376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Alam, S.R.; Bin-Masud, R.; Prantika, T.R.; Pervez, M.N.; Islam, M.S.; Naddeo, V. A Review on Characteristics, Techniques, and Waste-to-Energy Aspects of Municipal Solid Waste Management: Bangladesh Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.S.; Yang, A. Development of a system model to predict flows and performance of regional waste management planning: A case study of England. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbejule, A.; Shamsuzzoha, A.; Lotchi, K.; Rutledge, K. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Process to Select Waste-to-Energy Technology in Developing Countries: The Case of Ghana. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollution Control Department (PCD), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. Information on Municipal Solid Waste of Thailand. 2021. Available online: www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/PCD_MSWM%20policy.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2022). (In Thai).

- Pollution Control Department (PCD), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. Booklet on Thailand State of Pollution 2018; Pollution Control Department (PCD), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; ISBN 978-616-316-511-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pudcha, T.; Phongphiphat, A.; Wangyao, K.; Towprayoon, S. Forecasting Municipal Solid Waste Generation in Thailand with Grey Modelling. Environ. Nat. Resour. J. 2023, 21, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Agrawal, A. Recent trends in solid waste management status, challenges, and potential for the future Indian cities—A review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menikpura, S.N.M.; Sang-Arun, J.; Bengtsson, M. Assessment of environmental and economic performance of Waste-to-Energy facilities in Thai cities. Renew. Energy 2016, 86, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gour, A.A.; Singh, S.K. Solid Waste Management in India: A State-of-the-Art Review. Environ. Eng. Res. 2023, 28, 220249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A.; Choma´c-Pierzecka, E.; Kokiel, A.; Różycka, M.; Stasiak, J.; Soboń, D. Economic Conditions of Using Biodegradable Waste for Biogas Production, Using the Example of Poland and Germany. Energies 2022, 15, 5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaverková, M.D. Landfill Impacts on the Environment—Review. Geosciences 2019, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peerapong, P.; Limmeechokchai, B. Waste to Electricity Generation in Thailand: Technology, Policy, Generation Cost, and Incentives of Investment. Eng. J. 2016, 20, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Qahmash, A. SmartISM: Implementation and Assessment of Interpretive Structural Modeling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudatama, U.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Nazief, B.A.A. Approach Using Interpretive Structural Model (ISM) to Determine Key Sub-Factors at Factors: Benefits, Risk Reductions, Opportunities and Obstacles in Awareness IT Governance. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2018, 96, 5537–5549. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq, M.; Naz, S.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, M.N.; Mata, P.N.; Maqbool, S. A Study on Emerging Management Practices of Renewable Energy Companies after the Outbreak of COVID-19: Using an Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemidat, S.; Achouri, O.; El Fels, L.; Elagroudy, S.; Hafidi, M.; Chaouki, B.; Ahmed, M.; Hodgkinson, I.; Guo, J. Solid Waste Management in the Context of a Circular Economy in the MENA Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Y.H.; Yong, H.N.A. Barriers and critical success factors towards sustainable hazardous waste management in electronic industries–A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 669, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Abrar, F.; Nandy, R.K. Generation of Electricity Using Solid Waste in Chittagong. Am. J. Eng. Res. 2019, 8, 162–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bag, S.; Mondal, N.; Dubey, R. Modeling barriers of solid waste to energy practices: An Indian perspective. Global J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2016, 2, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ferronato, N.; Torretta, V. Waste Mismanagement in Developing Countries: A Review of Global Issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleya, P.; Ci, C.X.; Wen, C.L. Challenges in Enhancing Solid Waste Management towards Sustainable Environment: Local Council Perspectives. J. Adv. Res. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2019, 16, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Saseanu, A.S.; Gogonea, R.-M.; Ghita, S.I.; Zaharia, R.Ş. The Impact of Education and Residential Environment on Long-Term Waste Management Behavior in the Context of Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.F.; Chiang, F.-Y.; Le, T.H.A.; Lin, S.-W. Using the ISM Method to Analyze the Relationships between Various Contractor Prequalification Criteria. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uk, Z.C.; Basfirinci, C.; Mitra, A. Weighted Interpretive Structural Modeling for Supply Chain Risk Management: An Application to Logistics Service Providers in Turkey. Logistics 2022, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, M.; Konanahalli, A.; Dwarapudi, R.; Janardhanan, M. Assessment of Barriers and Strategies for the Enhancement of Off-Site Construction in India: An ISM Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushil. Interpreting the Interpretive Structural Model. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2012, 13, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, S. Sustainable Development of Foodservices under Uncertainty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).