Green but Unpopular? Analysis on Purchase Intention of Heat Pump Water Heaters in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. HPWHs

2.1.2. Theoretical Background

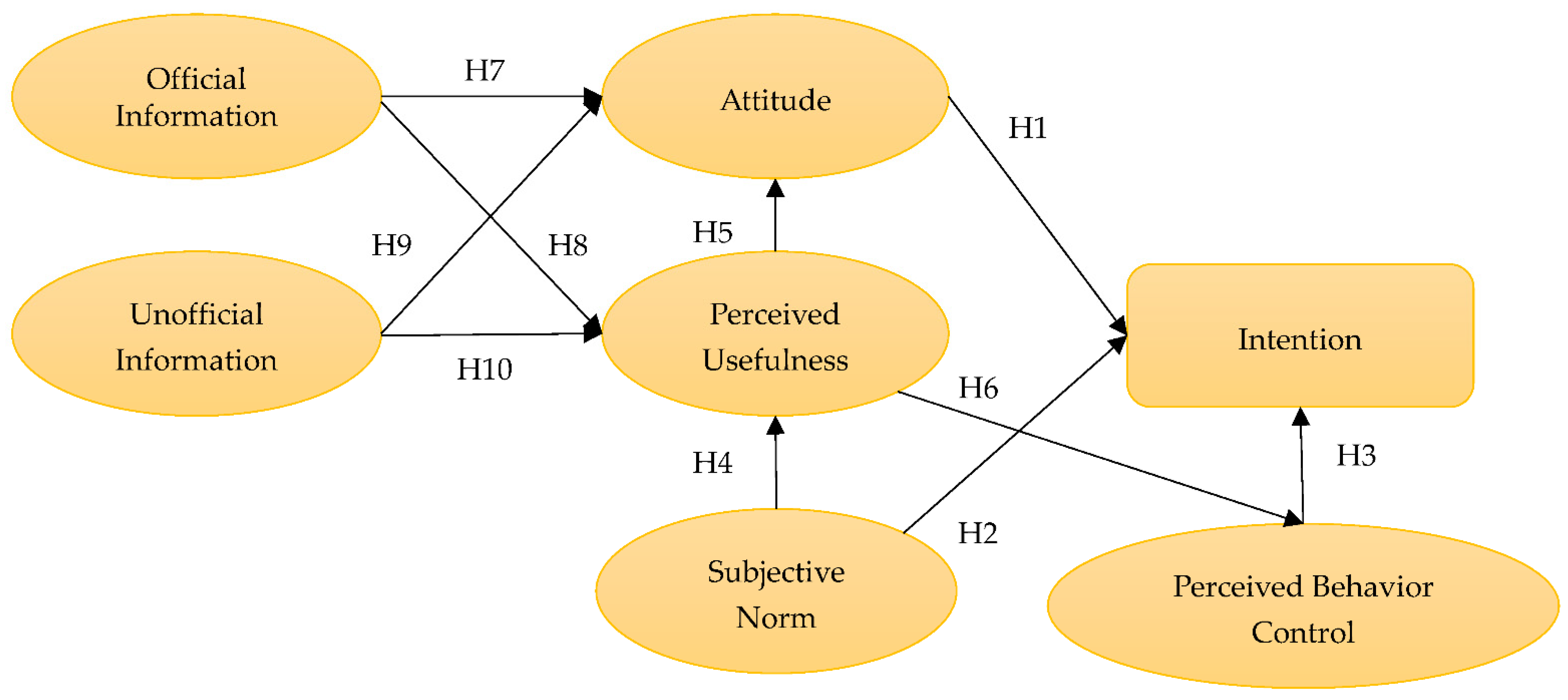

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2.2. Effect of Perceived Usefulness

2.2.3. Effect of Information Sources

3. Methodology

3.1. Structural Equation Model

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Survey Mode

3.3. Data Overview

4. Results

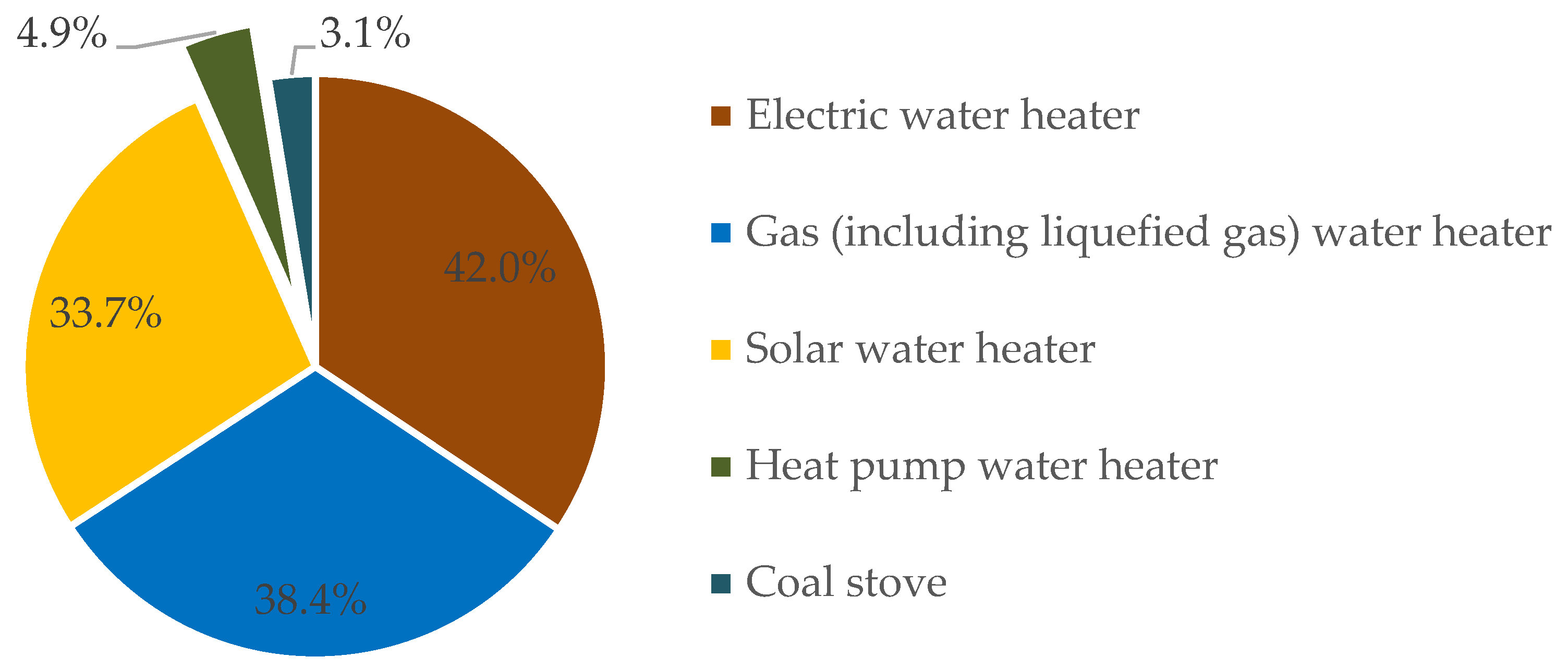

4.1. Respondents’ Usage and Purchase Intention for HPWHs

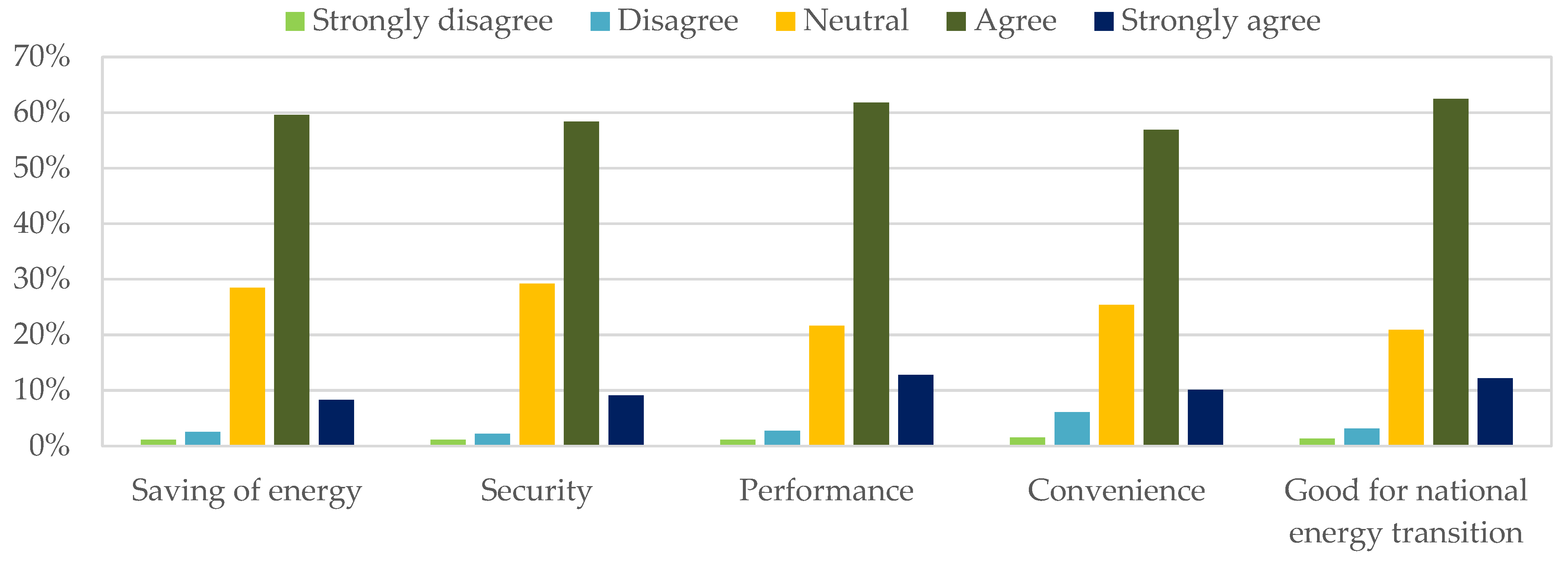

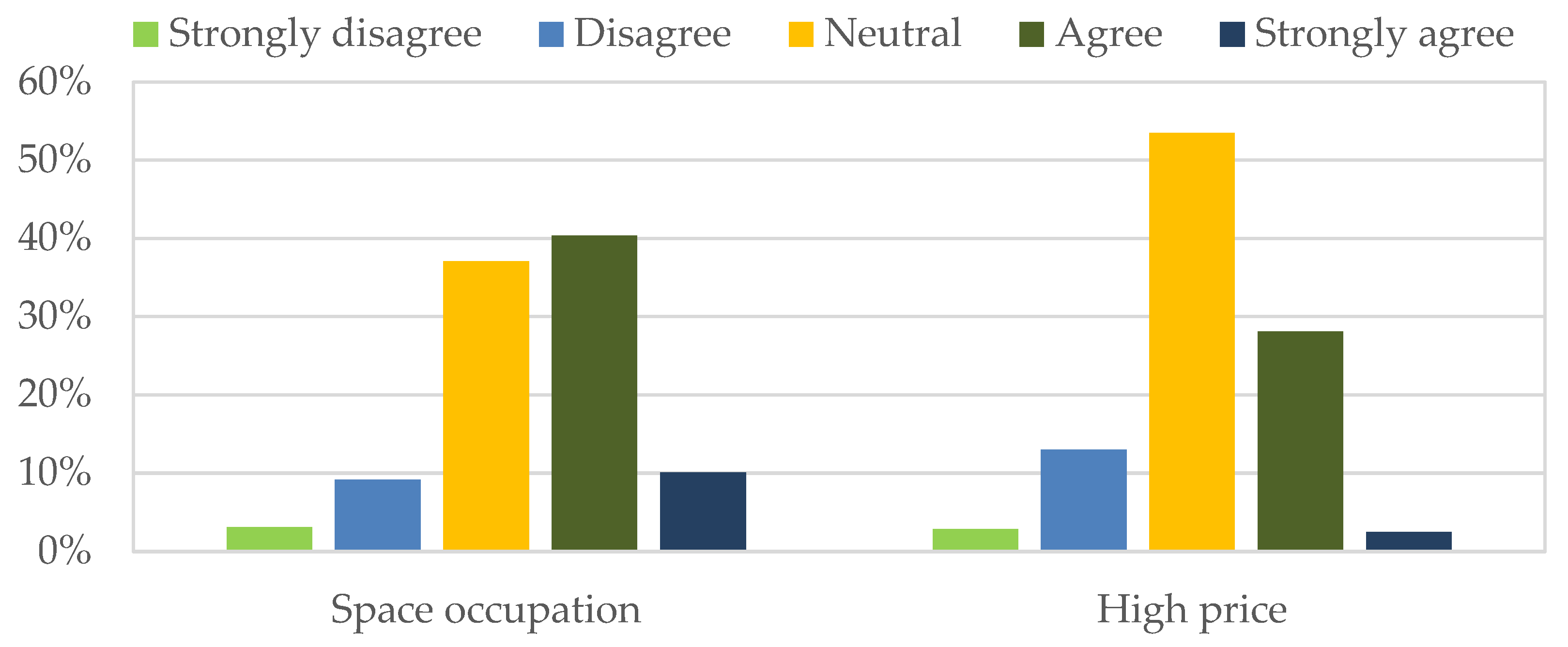

4.2. Respondents’ Perceptions about HPWHs

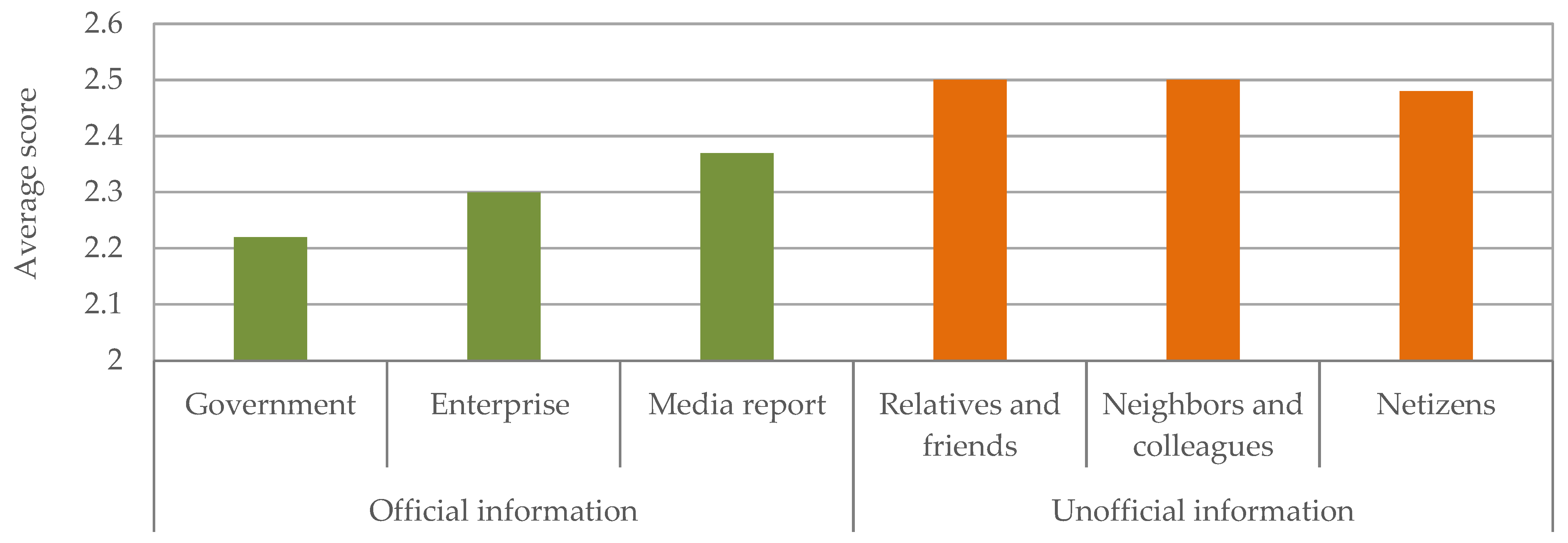

4.3. Respondents’ Information Sources about HPWHs

4.4. Factors Affecting Respondents’ Purchase Intention for HPWHs

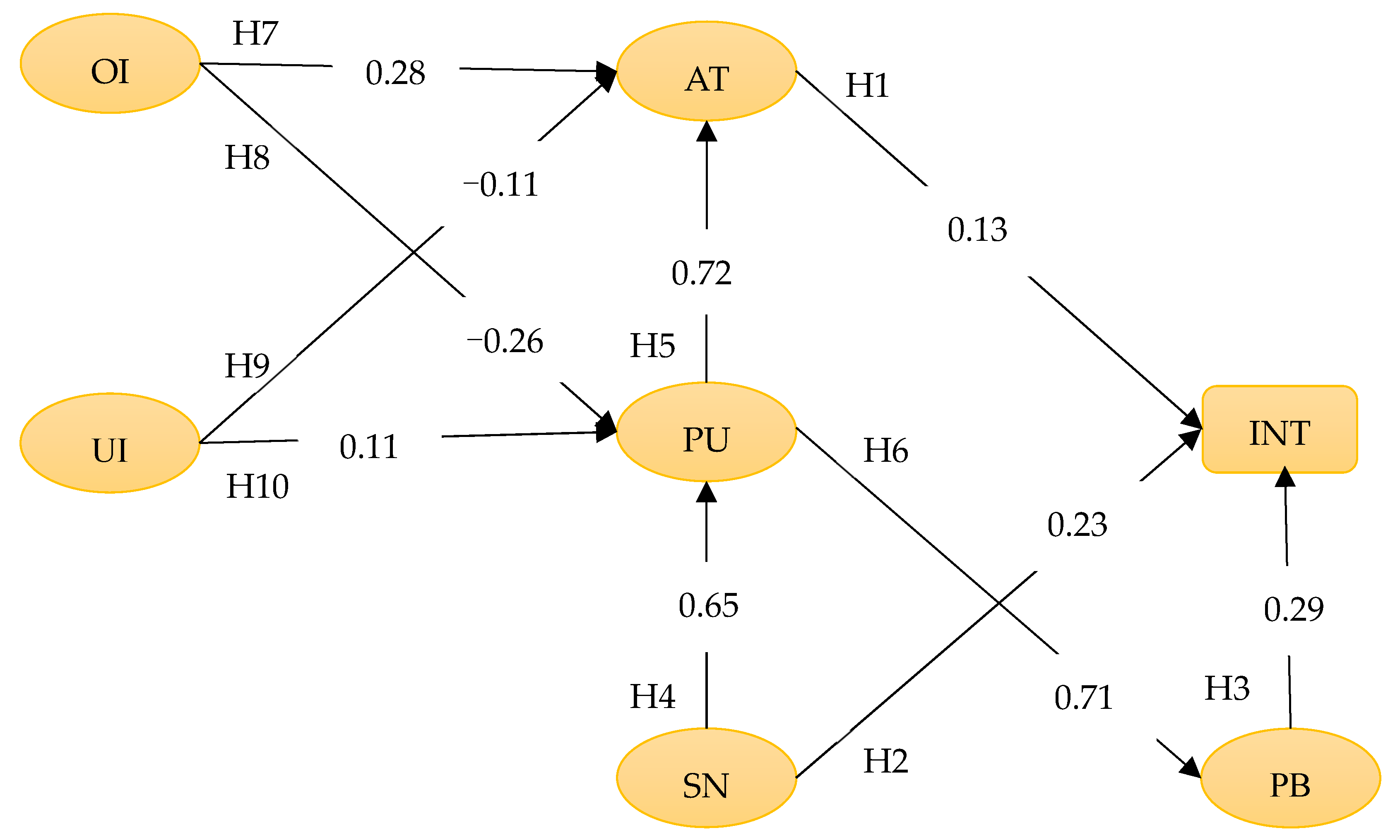

5. Discussion

6. Policy Implications

7. Conclusions

- In the Yangtze River Delta region of eastern China, HPWHs are not more popular than water heaters directly heated by electricity and natural gas;

- A high proportion of respondents recognize the environmental benefits and efficiency advantages of HPWHs. However, the large volume (HPWH occupies too much space) and high price of HPWHs dissatisfy consumers;

- Most consumers pay more attention to the large volume than to the high price of HPWHs;

- Consumers’ purchase intention for HPWHs does not differ significantly by income level or living environment, yet positively correlates with housing area. Compared to residents living in smaller houses, residents living in larger houses show higher purchase intention.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Bian, X.-J.; Tan, W.; Song, J. The indirect energy consumption and CO2 emission caused by household consumption in China: An analysis based on the input-output method. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 163, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, L.; Xue, B. Survey on the households’ energy-saving behaviors and influencing factors in the rural loess hilly region of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, D. Policy implications of the purchasing intentions towards energy-efficient appliances among China’s urban residents: Do subsidies work? Energy Policy 2017, 102, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Long, R.; Chen, H. Factors influencing energy-saving behavior of urban households in Jiangsu Province. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.-S.; Ooi, H.-Y.; Goh, Y.-N. A moral extension of the theory of planned behavior to predict consumers’ purchase intention for energy-efficient household appliances in Malaysia. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahangian, S.A.; Tabesh, M.; Yazdanpanah, M. How can socio-psychological factors be related to water-efficiency intention and behaviors among Iranian residential water consumers? J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 288, 112466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, R.; Sultana, S.; Masud, M.M.; Jafrin, N.; Al-Mamun, A. Consumers’ environmental ethics, willingness, and green consumerism between lower and higher income groups. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, R.; Antunes, D. Energy efficiency and appliance purchases in Europe: Consumer profiles and choice determinants. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7335–7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, B.; Schleich, J. What’s driving energy efficient appliance label awareness and purchase propensity? Energy Policy 2010, 38, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhao, M. Factors and mechanisms affecting green consumption in China: A multilevel analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Guo, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Analysis of factors influencing residents’ habitual energy-saving behaviour based on NAM and TPB models: Egoism or altruism? Energy Policy 2018, 116, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W.; Ford, N. The household energy gap: Examining the divide between habitual- and purchase-related conservation behaviours. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 1425–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Li, B.; Fan, X.; Fu, Z. Application of an air source heat pump (ASHP) for heating in Harbin, the coldest provincial capital of China. Energy Build. 2017, 138, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/qt/201206/t20120608_967818.html?code=&state=123 (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- The National Energy Administration. Available online: http://zfxxgk.nea.gov.cn/auto84/201812/t20181219_3562.htm (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- The Heat Pump Professional Committee of China Energy Conservation Association. Available online: http://www.chpa.org.cn/Index/show/catid/2/id/39.html (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Carroll, Z.; Couzo, E. Should North Carolina require more efficient water heaters in homes? A cost-benefit analysis. Energy Policy 2021, 150, 112113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh, C.E.; Sikhonza, M.; Tangwe, S. Linear Regression Analysis and Techno-Economic Viability of an Air Source Heat Pump Water Heater in a Residence at a University Campus. Energies 2021, 14, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y. Using air source heat pump air heater(ASHP-AH) for rural space heating and power peak load shifting. Energy Procedia 2017, 122, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R. Study on Performance of Air Source Heat Pump Water Heater. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 608–609, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepbasli, A.; Kalinci, Y. A review of heat pump water heating systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1211–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.; Bowers, C.; Elbel, S.; Hrnjak, P. Development of high-efficiency carbon dioxide commercial heat pump water heater. HVACR Res. 2013, 19, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Hao, X.; Zhang, D. The computation on compressor model of DC inverter based on the intelligent sensing algorithm of water heater system performance. Clust. Comput. 2019, 22, 5165–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willem, H.; Lin, Y.; Lekov, A. Review of energy efficiency and system performance of residential heat pump water heaters. Energy Build. 2017, 143, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Mi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Experimental Research of a Water-Source Heat Pump Water Heater System. Energies 2018, 11, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Treichel, C.; Cruickshank, C.A. Energy analysis of heat pump water heaters coupled with air-based solar thermal collectors in Canada and the United States. Energy 2021, 221, 119801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G.L.; Anderson, T.; Behnia, M. Seasonal performance rating of heat pump water heaters. Sol. Energy 2004, 76, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.S.; Seo, J.-H.; Lee, M.-Y. Heat transfer characteristics of the heat exchangers for refrigeration, air conditioning and heat pump systems under frosting, defrosting and dry/wet conditions—A review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 113, 1071–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, Z.; Hao, P.; Huan, C.; Wang, T. Performance investigation of a novel frost-free air-source heat pump water heater combined with energy storage and dehumidification. Appl. Energy 2015, 139, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.R.; Song, S.M.; Yin, J.M.; Kim, M.H.; Bullard, C.W.; Hrnjak, P.S. Experimental results of transcritical CO2 heat pump for residential application. Energy 2003, 28, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.W.; Kang, H.; Yoon, W.J.; Kim, Y. Performance comparison between a single-stage and a cascade multi-functional heat pump for both air heating and hot water supply. Int. J. Refrig. 2013, 36, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, M.S. Performance investigation of a cascade heat pump water heating system with a quasi-steady state analysis. Energy 2013, 63, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Nie, J.; Li, Y. Techno-economic analysis of air source heat pump applied for space heating in northern China. Appl. Energy 2017, 207, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj, M.; Karthick, L.; Dhivagar, R. Performance and economic analysis of a heat pump water heater assisted regenerative solar still using latent heat storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 196, 117263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Jin, H.; Gu, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Shen, X. Studies on the online intelligent diagnosis method of undercharging sub-health air source heat pump water heater. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 169, 114957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.J.; Wu, J.Y.; Wang, R.Z. A new approach to energy consumption prediction of domestic heat pump water heater based on grey system theory. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, G. Willingness to pay a price premium for energy-saving appliances: Role of perceived value and energy efficiency labeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Wang, S.; Yan, S. Exploring the effects of normative factors and perceived behavioral control on individual’s energy-saving intention: An empirical study in eastern China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Qin, H.; Wang, S. Young people’s behaviour intentions towards reducing PM2.5 in China: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.P.; Chakraborty, A.; Roy, M. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to explore circular economy readiness in manufacturing MSMEs, India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Chan, E.H.W. Critical Factors Influencing the Adoption of Smart Home Energy Technology in China: A Guangdong Province Case Study. Energies 2019, 12, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogiemwonyi, O. Factors influencing generation Y green behaviour on green products in Nigeria: An application of theory of planned behaviour. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2022, 13, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berki-Kiss, D.; Menrad, K. The role emotions play in consumer intentions to make pro-social purchases in Germany—An augmented theory of planned behavior model. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.; Anokye, N.K.; Pokhrel, S. What interventions increase commuter cycling? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaime Torres, M.M.; Carlsson, F. Direct and spillover effects of a social information campaign on residential water-savings. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 92, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C.; Rothengatter, T. A review of intervention studies aimed at household energy conservation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.L.; Delmas, M.A.; Locke, S.L.; Singh, A. Information strategies for energy conservation: A field experiment in India. Energy Econ. 2017, 68, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holbert, R.L.; Kwak, N.; Shah, D.V. Environmental Concern, Patterns of Television Viewing, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Integrating Models of Media Consumption and Effects. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2003, 47, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yue, C.; Li, J.; Zhu, J.; Chen, H.; Wei, J. The Influence of Information Intervention Cognition on College Students’ Energy-Saving Behavior Intentions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, C.; Liu, H.; Zheng, S. The role of public information in increasing homebuyers’ willingness-to-pay for green housing: Evidence from Beijing. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 129, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffaro, F.; Micheletti Cremasco, M.; Roccato, M.; Cavallo, E. Drivers of farmers’ intention to adopt technological innovations in Italy: The role of information sources, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 76, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Yu, Y.; Urban, F. Green transition of energy systems in rural China: National survey evidence of households’ discrete choices on water heaters. Energy Policy 2018, 113, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abreu, J.; Wingartz, N.; Hardy, N. New trends in solar: A comparative study assessing the attitudes towards the adoption of rooftop PV. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Hung, C.-W. Elucidating the factors influencing the acceptance of green products: An extension of theory of planned behavior. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 112, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffashi, S.; Shamsudin, M.N. Transforming to a low carbon society; an extended theory of planned behaviour of Malaysian citizens. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Nilashi, M.; Samad, S.; Abdullah, R.; Mahmoud, M.; Alkinani, M.H.; Yadegaridehkordi, E. Factors impacting consumers’ intention toward adoption of electric vehicles in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ge, J. Electric vehicle development in Beijing: An analysis of consumer purchase intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangunić, N.; Granić, A. Technology acceptance model: A literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, F.; Teo, T.; Zhou, M. Chinese students’ intentions to use the Internet-based technology for learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, J.; Wetzels, M. A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model: Investigating subjective norm and moderation effects. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, M.; Shaw, K. An extension of technology acceptance model for mHealth user adoption. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustofa, R.H.; Pramudita, D.A.; Atmono, D.; Priyankara, R.; Asmawan, M.C.; Rahmattullah, M.; Mudrikah, S.; Pamungkas, L.N.S. Exploring educational students acceptance of using movies as economics learning media: PLS-SEM analysis. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2022, 39, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.J.; Hovland, C.I.; McGuire, W.J.; Abelson, R.P.; Brehm, J.W. Attitude Organization and Change: An Analysis of Consistency among Attitude Components. (Yales Studies in Attitude and Communication); Yale University Press: London, UK, 1960; Volume III. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Li, G. Determinants of energy-saving behavioral intention among residents in Beijing: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2014, 6, 053127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Yadav, R. The impact of shopping motivation on sustainable consumption: A study in the context of green apparel. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iovino, R.; Iraldo, F. The circular economy and consumer behaviour: The mediating role of information seeking in buying circular packaging. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3435–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momsen, K.; Ohndorf, M. When do people exploit moral wiggle room? An experimental analysis of information avoidance in a market setup. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, S.; Kondo, K.; Nogata, D.; Ben, H. The determinants of household energy-saving behavior: Survey and comparison in five major Asian cities. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, K.; Söderholm, P. The devil is in the details: Household electricity saving behavior and the role of information. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 1578–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, S.A.N.; Tolmie, C.R. Millennials’ green consumption behaviour: Exploring the role of social media. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. Service co-creation in social media: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.K.; Totten, J.W. Self-construal’s role in mobile TV acceptance: Extension of TAM across cultures. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Wang, S. Antecedents of consumers’ intention to purchase energy-efficient appliances: An empirical study based on the technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kave, L. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Municipal Development & Reform Commission. Available online: https://fgw.sh.gov.cn/fgw_zyjyhhjbh/20211101/4b0c855698fc49f19c6ef03e7620c3be.html (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Jiangsu Provincial Development and Reform Commission. Available online: http://fzggw.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2012/10/31/art_4646_6650111.html (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Zhejiang Provincial Development and Reform Commission. Available online: http://fzggw.zj.gov.cn/art/2016/9/10/art_1599544_34398176.html (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- The People’s Government of Zhejiang Province. Available online: http://www.zj.gov.cn/art/2021/4/1/art_1229005922_2266196.html (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Anhui Provincial Development and Reform Commission. Available online: http://fzggw.ah.gov.cn/public/7011/139439451.html (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding pro-environmental behavior: A comparison of sustainable consumers and apathetic consumers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehurst, G.; Afonso, C.; Gonçalves, H.M. Re-examining green purchase behaviour and the green consumer profile: New evidences. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ji, C.; He, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Tourists’ waste reduction behavioral intentions at tourist destinations: An integrative research framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Law, R.; Schuckert, M. Mediating effects of attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control for mobile payment-based hotel reservations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Impact of Online Consumer Reviews on Sales: The Moderating Role of Product and Consumer Characteristics. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, A.; Lantz, B. Information dissemination and residential solar PV adoption rates: The effect of an information campaign in Sweden. Energy Policy 2020, 142, 111540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-W.; Namkung, Y. The information quality and source credibility matter in customers’ evaluation toward food O2O commerce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, H.; Goto, M.; Sueyoshi, T. Consumer choice on ecologically efficient water heaters: Marketing strategy and policy implications in Japan. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, N.; MacGregor, S.; Catney, P.; Dobson, A.; Ormerod, M.; Robinson, Z.; Ross, S.; Royston, S.; Marie Hall, S. Factors influencing perceptions of domestic energy information: Content, source and process. Energy Policy 2014, 65, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Item | Mean | Skewness | Kurtosis | Standardized Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | AT1 | 3.37 | −0.272 | 0.386 | 0.666 | 0.836 |

| AT2 | 3.44 | −0.342 | 0.484 | 0.883 | ||

| AT3 | 3.59 | −0.461 | 0.758 | 0.854 | ||

| SN | SN1 | 2.78 | −0.089 | 0.148 | 0.754 | 0.782 |

| SN2 | 3.26 | −0.470 | 0.233 | 0.904 | ||

| SN3 | 3.54 | −0.778 | 1.103 | 0.615 | ||

| PB | PB1 | 3.61 | −0.934 | 1.420 | 0.753 | 0.846 |

| PB2 | 3.69 | −0.783 | 1.381 | 0.824 | ||

| PB3 | 3.69 | −0.657 | 1.222 | 0.840 | ||

| PU | PU1 | 3.71 | −0.777 | 1.793 | 0.860 | 0.886 |

| PU2 | 3.72 | −0.713 | 1.677 | 0.866 | ||

| PU3 | 3.82 | −0.869 | 2.022 | 0.823 | ||

| OI | OI1 | 2.22 | 0.277 | −1.157 | 0.907 | 0.941 |

| OI2 | 2.30 | 0.187 | −1.026 | 0.919 | ||

| OI3 | 2.37 | 0.090 | −1.174 | 0.927 | ||

| UI | UI1 | 2.50 | −0.016 | −0.958 | 0.881 | 0.891 |

| UI2 | 2.50 | 0.063 | −1.038 | 0.845 | ||

| UI3 | 2.48 | −0.007 | −1.040 | 0.842 |

| Variables | UI | OI | PU | PB | SN | AT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | UI | 1 | |||||

| OI | 0.605 | 1 | |||||

| PU | 0.066 | −0.023 | 1 | ||||

| PB | 0.110 | 0.079 | 0.691 | 1 | |||

| SN | 0.194 | 0.275 | 0.574 | 0.552 | 1 | ||

| AT | 0.111 | 0.201 | 0.687 | 0.593 | 0.549 | 1 | |

| Test indices | CR | 0.892 | 0.941 | 0.886 | 0.848 | 0.807 | 0.847 |

| AVE | 0.733 | 0.842 | 0.722 | 0.651 | 0.588 | 0.651 | |

| 0.856 | 0.918 | 0.850 | 0.807 | 0.767 | 0.807 |

| Variables | Number | Percentage (%) | Purchase Intention | Significance Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living space | <60 m2 | 31 | 7.0 | 3.26 | 0.001 |

| 60–90 m2 | 99 | 22.2 | 3.25 | ||

| 90–140 m2 | 241 | 54.2 | 3.48 | ||

| 140–280 m2 | 58 | 13.0 | 3.59 | ||

| >280 m2 | 16 | 3.6 | 3.94 | ||

| Living environment | city district | 239 | 53.7 | 3.44 | 0.895 |

| suburban area | 103 | 23.1 | 3.43 | ||

| rural area | 103 | 23.1 | 3.48 | ||

| Household income per month | 0–270 Yuan | 4 | 0.90 | 3.50 | 0.581 |

| 270–1100 Yuan | 11 | 2.47 | 3.45 | ||

| 1100–2050 Yuan | 27 | 6.07 | 3.63 | ||

| 2050–4500 Yuan | 107 | 24.04 | 3.44 | ||

| 4500–9800 Yuan | 179 | 40.22 | 3.47 | ||

| 9800–22,500 Yuan | 110 | 24.72 | 3.38 | ||

| 22,500–41,000 Yuan | 7 | 1.57 | 3.00 | ||

| Fit Indices | CFI | GFI | TLI | NFI | IFI | RNSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold value | <3.00 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | <0.08 |

| Structural model | 2.889 | 0.952 | 0.911 | 0.941 | 0.929 | 0.952 | 0.065 |

| Path | Unstandardized Path Coefficient | C.R. | p Value | Hypotheses | Decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | → | INT | 0.208 | 2.220 | 0.027 | H1 | Supported |

| SN | → | INT | 0.296 | 4.052 | *** | H2 | Supported |

| PB | → | INT | 0.407 | 4.793 | *** | H3 | Supported |

| SN | → | PU | 0.659 | 11.297 | *** | H4 | Supported |

| PU | → | AT | 0.560 | 11.629 | *** | H5 | Supported |

| PU | → | PB | 0.636 | 12.659 | *** | H6 | Supported |

| OI | → | AT | 0.140 | 5.155 | *** | H7 | Supported |

| OI | → | PU | −0.160 | −4.283 | *** | H8 | Not Supported |

| UI | → | AT | −0.065 | −2.056 | 0.040 | H9 | Not Supported |

| UI | → | PU | 0.076 | 1.765 | 0.078 | H10 | Not Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, S.; Li, F.; Xie, W. Green but Unpopular? Analysis on Purchase Intention of Heat Pump Water Heaters in China. Energies 2022, 15, 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15072464

Bai S, Li F, Xie W. Green but Unpopular? Analysis on Purchase Intention of Heat Pump Water Heaters in China. Energies. 2022; 15(7):2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15072464

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Shucai, Fangyi Li, and Wu Xie. 2022. "Green but Unpopular? Analysis on Purchase Intention of Heat Pump Water Heaters in China" Energies 15, no. 7: 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15072464

APA StyleBai, S., Li, F., & Xie, W. (2022). Green but Unpopular? Analysis on Purchase Intention of Heat Pump Water Heaters in China. Energies, 15(7), 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15072464