The Balance of Outlays and Effects of Restructuring Hard Coal Mining Companies in Terms of Energy Policy of Poland PEP 2040

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Polish Economy Transformation

1.2. Structural Changes

1.3. The Nature of Restructuring

1.4. The Course of Restructuring the Coal Mining Industry in Poland

- Dominant role of the market mechanism of resource allocation, and attributing an exogenous function to economic policies;

- Building long-lasting and high competitiveness;

- Increased effectiveness of managing creative resources as a result of their restructuring.

- Separation of non-production activities from coal mines and outsourcing of selected support processes;

- Reduction in employment—the main cost-generating factor;

- Adjustment of output to domestic demand and profitable export;

- Reduction in production capacity and liquidation of selected coal mines.

- 1996–1997—technical restructuring and suspension of the liquidation programme [86];

2. Research Methodology

- H1.

- Restructuring is not a uniform process in terms of its intensity in time and achieved results, which allows for its periodization and the determination of its effectiveness;

- H2.

- The main driver of changes was the replacement of human labour by objectified labour (machines and equipment), leading to the increased productivity of labour and a more efficient use of assets under the conditions of a stable capital structure;

- H3.

- Effective management and economic relationships resulting from restructuring ensured companies’ stability and long-term operations;

- H4.

- The incurred costs of restructuring contributed to changes to the energy mix (its desired time and degree), reducing the related expenditure.

- Labour and tangible costs productivity;

- Asset productivity;

- Asset–capital structure;

- Fixed asset renewal.

3. Results

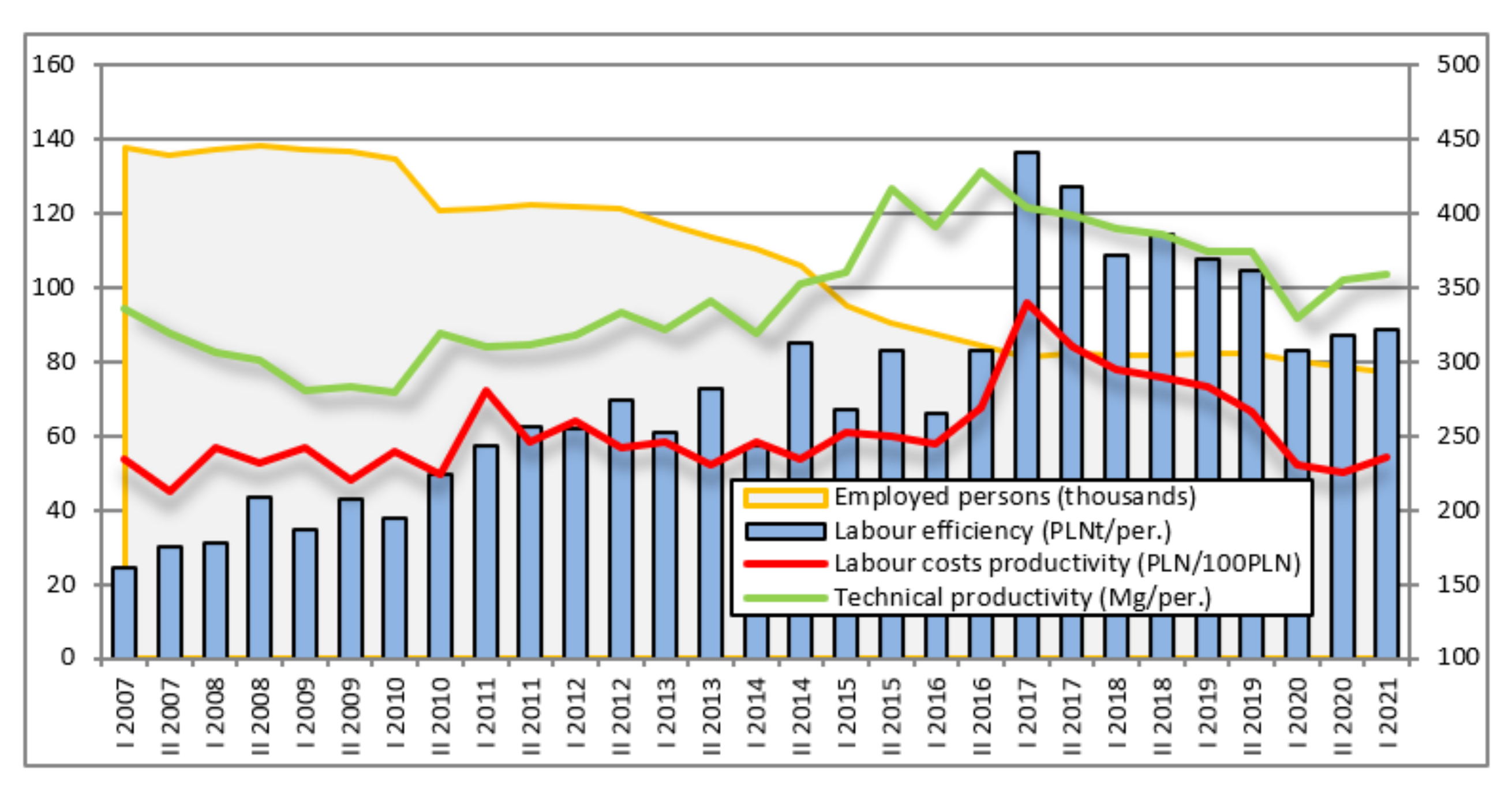

3.1. Labour Costs and Tangible Costs

3.2. Partial Cost Intensity Components vs. Asset Productivity

3.3. Asset–Capital Structure

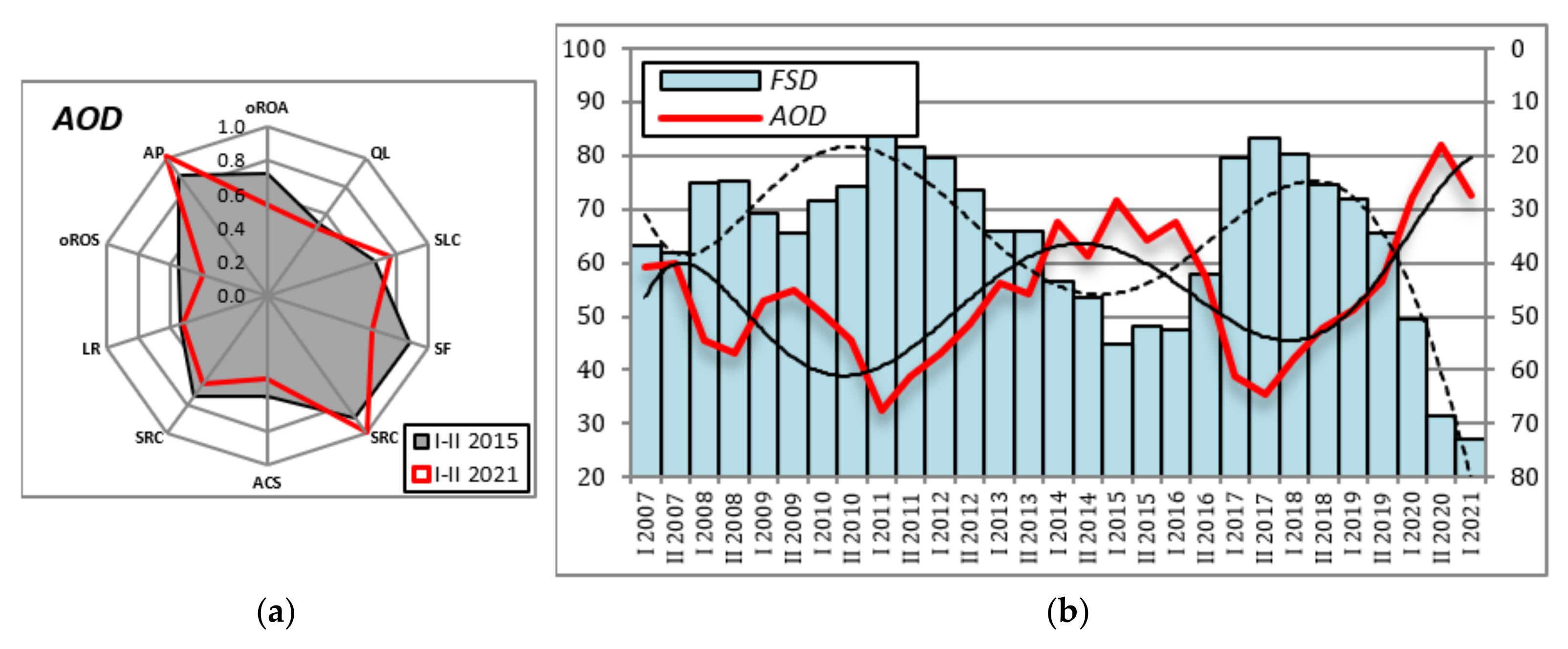

3.4. Renewal of Fixed Production Resources

3.5. The Measure of Restructuring and Its Factors

3.6. Financial Results and Their Determinants after 2006

4. Discussion

- Relatively low-cost intensity related to tangible costs, accompanied by the lack of limitations of the contribution of labour to the obtained results, justifies the statement that technological advancement processes are not characterised by high intensity (the replacement of human labour by objectified labour). Moreover, despite two distinct periods of short-term decreases in the share of labour costs, this share in the last analysed years was similar to that at the beginning of the process [121]. The originally intense outsourcing activities tended to decline (coal mining companies became less inclined to cooperate with other entities) [122]. Generally, the evaluation of changes in the productivity of labour costs and tangible costs was negative—the period of 31 years as not marked by visible progress in this area—and the current level of productivity was comparable with that recorded in the early 1990s.

- Current asset productivity remained unchanged after 1997, which contradicts the universal and expected trend of increasing the efficiency of current asset management [123]. Fixed asset productivity is of key significance to coal mining—a capital intensive industry. Unfortunately, productivity levels tended to decrease steadily after initial increases (until 1997), which should be regarded as a negative phenomenon in the context of the general advancement of techniques and technologies of coal extraction. Generally, the assessment of changes in asset productivity and its potential to generate financial effects (revenue from sales) was negative, and negative trends prevailed, particularly after 2011.

- The stability of activities is created by appropriate relations between the sources and the period of the availability of capital and the investment of capital in fixed and current assets [124]. This indicates the need to adhere to the balance sheet rules of thumb. Unfortunately, coal mining companies failed to act in accordance with this rule throughout the period of the 31 analysed years (operating well below recommended standards). Moreover, this trend was accompanied by increasing levels of asset immobilization and decreasing levels of self-financing. This violates the fundamental principles of economics and effective performance [125]. The combined impact of these factors indicates a serious threat to going concern and a bankruptcy predictor [126]. Therefore, the assessment of changes in the asset–capital structure was highly negative.

- The process of investing in fixed assets, considering its high instability, did not balance their wear and tear and, consequently, decapitalization [127] (pp. 127–138). It had a negative impact on asset productivity, hindering technical and technological advancement, particularly after a sharp decline in investment after 2012. Proper relationships between fixed asset investment and the wear and tear process were maintained only in the period of 2003–2012 [128]. At that time, investment outlays increased while the latter process was at a stable level. Apart from this period, fixed asset management was not properly focused and ineffective.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Transition, The First Ten Years: Analysis and Lessons for Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 1–164. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/14042 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Kołodko, G.W.; Nuti, M.D. The Polish Alternative. Old Myths, Hard Facts and New Strategies in the Successful Transformation of the Polish Economy; Wider: Helsinki, Finland, 1997; pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Szpor, A.; Ziółkowska, K. The Transformation of the Polish Coal Sector, GSI Report; The International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2018; pp. 1–25. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/transformation-polish-coal-sector.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Peña, J.I.; Rodríguez, R. Are EU’s Climate and Energy Package 20-20-20 targets achievable and compatible? Evidence from the impact of renewables on electricity prices. Energy 2019, 183, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryk, B.; Guzowska, M. Implementation of Climate/Energy Targets of the Europe 2020 Strategy by the EU Member States. Energies 2021, 14, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whither Are You Headed, Polish Coal? Development Prospects of the Polish Hard Coal Mining Sector; Warsaw Institute for Economic Studies: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; pp. 1–48. Available online: https://wise-europa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Whither-are-you-headed-Polish-coal.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Fuksa, D. Opportunities and Threats for Polish Power Industry and for Polish Coal: A Case Study in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauers, H.; Oei, P.-Y. The political economy of coal in Poland: Drivers and barriers for a shift away from fossil fuels. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozowska, S.; Wendt, J.A.; Tomaszewski, K. The Challenges of Poland’s Energy Transition. Energies 2021, 14, 8165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywda, J.; Krzywda, D.; Androniceanu, A. Managing the Energy Transition through Discourse. The Case of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAP 2022. Program dla Sektora Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce do 2030r. Wraz z Kierunkami Transformacji Sektora i Korektami z 11 Stycznia 2022 (Program for the Hard Coal Mining Sector in Poland until 2030 Along with Directions for Transformation of the Sector and Revisions of 11 January 2022); Ministerstwo Aktywów Państwowych (MAP): Warszawa, Poland, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/21157355-d3e6-4ea2-8cfc-3e7a4d87696f (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Csaba, L. The Capitalist Revolution in Eastern Europe: A Contribution to the Economic Theory of Systemic Change; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 1995; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Gelb, A.H.; Grey, C. The Transformation of Economies in Central and Eastern Europe. World Bank Policy Res. Ser. 1991, 17, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dewatripont, M.; Roland, G. Transition as a process of large-scale institutional change. Econ. Transit. 1996, 4, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; Kochanowicz, J.; Mizsei, K.; Muñoz, O. Intricate Links: Democratization and Market Reforms in Latin America and Eastern Europe; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1994; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Budnikowski, A. Transition from a centrally planned economy to a market economy: The case of Poland. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1992, 41, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornai, J. The Socialist System. The Political Economy of Communism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, P.G. From Central Planning to Market Economy: Some Microeconomic Issues. Econ. J. 1990, 100, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eucken, W. Die Grundlagen der Nationalökonomie: Über Die Lebensnahe Soziale Marktwirtschaft; Books on Demand: NorderStedt, Germany, 2021; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, O. The Economics of Post-Communist Transition; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, G. Transition and Economics: Politics, Markets and Firms; The IMT Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mickiewicz, T. Economic Transition in Central Europe and the CIS; Palgrave-McMillan: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005; pp. 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Murell, P. Evolution in Economics and in the Economic Reform of the Centrally Planned Economies; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 1991; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin, R. Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner, M. A Primer in European Macroeconomics; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 1997; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Gros, D.; Steinherr, A. Economic Transition in Central and Eastern Europe: Planting the Seed; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; p. 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koźmiński, A. How It All Happened. Essays in Political Economy of Transition; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2008; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodko, G.W. Sukces na Dwie Trzecie. Polska Transformacja Ustrojowa i Lekcje na Przyszłość (Success at Two Thirds. Poland’s Systemic Transformation and Lessons for the Future). Ekonomista 2007, 6, 799–836. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, J. The Disharmonies, Dilemmas and Effects of the Transformation of the Polish Economy. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P.F. Post-Capitalist Society; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Transition Report. Recovery and Reform 2010; European Bank for Reconstruction and Development: London, UK, 2010; Available online: https://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/transition/tr10.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Fischer, S.; Sahay, R.; Vegh, C.A. Stabilization and Growth in Transition Economies: The Early Experience. J. Econ. Perspect. 1996, 10, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidrmuc, J. Forecasting Growth in Transition Economies: A Reassessment; ZEI: Bonn, Germany, 2001; pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, O. Assesment of the Economic Transition in Central and Eastern Europe—Theoretical Aspects of Transition. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, D.; Radulescu, R. The sequencing of reform in transition economies. J. Comp. Econ. 2005, 33, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslund, A.; Boone, P.; Johnson, S.; Fischer, S.; Ickes, B.W. How to Stabilize: Lessons from Post-Communist Countries. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 1996, 1996, 217–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, L.; Moers, L. Growth empirics with institutional measures for transition countries. Econ. Syst. 2001, 25, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, A.; Kisunko, G.; Weder, B. Institutions in Transition: Reliability of Rules and Economic Performance in Former Socialist Countries; Working Paper; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; Volume 1809, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehr, K. Reforms and Economic Growth in Transition Economies: Complementarity, Sequencing, and Speed. Eur. J. Comp. Econ. 2005, 2, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Megginson, W.L.; Netter, J.M. From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on Privatization. J. Econ. Lit. 2001, 39, 321–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heybey, B.; Murrell, P. The relationship between economic growth and the speed of liberalization during transition. J. Policy Reform 1999, 3, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, E.C. Review of Economic Rhythm: A Theory of Business Cycles, by E. Wagemann. J. Bus. Univ. Chic. 1931, 4, 101–103, Original book: Wageman, E. Economic Rhythm: A Theory of Business Cycles; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1930. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2349127 (accessed on 10 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Lhomme, J. Materiaux pour une theorie de la structure economique et sociale. Rev. Econ. 1954, 5, 843–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, S. Economic Growth of Nations. Total Output and Production Structure; HUP Belknap Press Imprint: Cambridge, UK, 2013; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Naisbitt, J.; Aburdene, P. Megatrends 2000. New Directions for Tomorrow; Sidgwick and Jackson: London, UK, 1990; pp. 120–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, J. The Role of Structural Policies in Counteracting the Crisis. In Moving from the Crisis to Sustainability. Emerging Issues in the International Context; Calabro, G., D’Amico, A., Lanfranchi, M., Moschella, G., Pulejo, L., Salomone, R., Eds.; Edizioni Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2011; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rainelli, M. Économie industrielle et droit économique dans la Revue d’économie industrielle. Revue D’économie Industrielle 2010, 129–130, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, R.B. Making Industrial Policy. Foreign Aff. 1982, 60, 852–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaziner, I.C.; Reich, R.B. Minding America’s Business: The Decline and Rise of the American Economy. Polit. Soc. 1982, 11, 509–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, W.; Primi, A. Theory and Practice of Industrial Policy. Evidence from the Latin American Experience. UN Cepal 2009, 187, 1–51. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/4582-theory-and-practice-industrial-policy-evidence-latin-american-experience (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1942; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Koźmiński, A.; Obłój, K. Zarys Teorii Równowagi Organizacyjnej (Outline of Organizational Balance Theory); PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 1989; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H. Challenges in Researching Corporate Restructuring. J. Manag. Stud. 1993, 30, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, J.A.F.; Freeman, R.E.; Gilbert, D.R. Management; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1995; p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Danovi, A.; Magno, F.; Dossena, G. Pursuing Firm Economic Sustainability through Debt Restructuring Agreements in Italy: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.W. Management; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 394–396. [Google Scholar]

- Mikołajczyk, Z. Techniki Organizatorskie w Rozwiązywaniu Problemów Zarządzania (Organizational Techniques in Solving Management Problems), 3rd ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1999; pp. 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gajdzik, B.; Gawlik, R. Choosing the Production Function Model for an Optimal Measurement of the Restructuring Efficiency of the Polish Metallurgical Sector in Years 2000–2015. Metals 2018, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.-H.; Tsai, C.-C. A Model Constructed to Evaluate Sustainable Operation and Development of State-Owned Enterprises after Restructuring. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Marx, M.; Stevenson, H.H. The tools of cooperation and change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lis, A. Typologia restrukturyzacji (Typology of restructuring). Przegląd Organizacji 2004, 4, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, J.F.; Copeland, T.E. Managerial Finance; Dryden Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 1083–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, J. The Stance, Factors, and Composition of Competitiveness of SMEs in Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Adventage. Creating and Sustaining Superiorer Performance; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Slatter, S. Corporate Recovery. A Guide to Turnaround Management; Penguin Business: London, UK, 1984; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Hurry, D. Restructuring in the global economy: The consequences of strategic linkages between Japanese and U.S. firms. Strat. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicksler, J.; Chen, A.H. An Economic Analysis of Interest Rate Swaps. J. Financ. 1986, 41, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, T.; Koller, T.; Murrin, J. Valuation—Measuring and Managing the Values of Companies; John Wiley Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Lisowski, A. Górnictwo Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce (Hard Coal Mining in Poland); Śląsk: Katowice, Poland, 1996; pp. 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dubiński, J.; Turek, M. Szanse i Zagrożenia Rozwoju Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce (Opportunities and Threats for the Development of Hard Coal Mining in Poland). Wiadomości Górnicze 2012, 63, 626–633. Available online: https://www.gwarkowie.pl/images/pliki/publicystyka/szanse-i-zagrozenia-rozwoju-gornictwa-wegla-kamiennego-w-polsce-339.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Kaczmarek, J. Intensywność i efekty transformacji gospodarczej (Intensity and Effects of Economic Transformation). Przegląd Organizacji 2016, 10, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowski, A. Górnictwo Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce. Ku Następnej Generacji Kopalń i Sektora (Hard Coal Mining in Poland. Towards the Next Generation of Mines and the Branch); GIG: Katowice, Poland, 2006; pp. 20–82. Available online: http://www.sbc.org.pl/Content/133902/Lisowski%201996_2005razem.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Kotelska, J. Przesłanki procesu restrukturyzacji górnictwa węgla kamiennego w Polsce (Reasons for the restructuring process of hard coal mining in Poland). ZN WSH Zarządzanie 2018, 19, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbownik, A.; Bijańska, J. Restrukturyzacja Polskiego Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Latach 1990–1999 (Restructuring of the Polish Hard Coal Industry in 1990–1999); Wyd. Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2000; pp. 14–86. Available online: http://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/Content/33660/REPO_37652_2000_Restrukturyzacja-pol_0000.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Riley, R.; Tkocz, M. Local responses to changed circumstances: Coalmining in the market economy in Upper Silesia, Poland. GeoJournal 1999, 48, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlik, L. Opportunities and Threats for Hard Coal Mining in Poland. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Q. 2017, 24, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paszcza, H. Procesy Restrukturyzacyjne w Polskim Górnictwie Węgla Kamiennego w Aspekcie Zrealizowanych Przemian i Zmiany Bazy Zasobowej (Restructuring Processes in the Polish Hard Coal Mining Industry in the Aspect of Realised Transformations and Change of the Resource Base). Górnictwo i Geoinżynieria 2010, 34, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dilling, R. Zadania Spółek Węglowych w Zakresie Technicznej Restrukturyzacji Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego (Tasks of Coal Companies in the Scope of Technical Restructuring of Hard Coal Mining). Przegląd Górniczy 1993, 9, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, M.; Śniegocki, A.; Wetmańska, Z. Od Restrukturyzacji do Trwałego Rozwoju. Przypadek Górnego Śląska (From Restructuring to Sustainable Development. The Case of Upper Silesia); Wise Europa, WWF Polska: Warszawa, Poland, 2018; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyk, E.J.; Kaczmarek, J.; Fijorek, K.; Kopacz, M. Efficiency and Financial Standing of Coal Mining Enterprises in Poland in Terms of Restructuring Course and Effects. Min. Resour. Manag. 2020, 36, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MPiH 1991. Program Reform i Harmonogramy Restrukturyzacji w Sektorze Energetycznym (Program of Reforms and Restructuring Schedules for the Energy Sector); Ministerstwo Przemysłu i Handlu (MPiH): Warszawa, Poland, September 1991. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/49265 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MPiH 1992. Propozycje w Sprawie Programów Restrukturyzacji Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego i Brunatnego Gazownictwa i Elektroenergetyki, Ciepłownictwa i Przemysłu Paliw Ciekłych (Proposals of Restructuring Programs for Hard Coal and Lignite Mining, Gas and Electric Power, Heating and Liquid Fuels Industries); Ministerstwo Przemysłu i Handlu (MPiH): Warszawa, Poland, 1992. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/49265 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MPiH 1993. Restrukturyzacja Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce—Realizacja Pierwszego Etapu w Ramach Możliwości Finansowych (Hard Coal Mining Restructuring in Poland—Implementation of the First Stage within the Financial Possibilities); Ministerstwo Przemysłu i Handlu (MPiH): Warszawa, Poland, 1993. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/49265 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MPiH 1993. Program Powstrzymania Upadłości Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce w 1993 Roku (Program of Stopping the Hard Coal Mining Industry Collapse in Poland in 1993); Ministerstwo Przemysłu i Handlu (MPiH): Warszawa, Poland, 1993. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/49265 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MPiH 1994. Restrukturyzacja Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego—Program dla Realizacji Drugiego Etapu w Okresie 1994–1995 (Hard Coal Mining Industry Restructuring—Program for the Implementation of the Second Stage in 1994–1995); Ministerstwo Przemysłu i Handlu (MPiH): Warszawa, Poland, 1994. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/49265 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MPiH 1996. Górnictwo Węgla Kamiennego—Polityka Państwa i Sektora na lata 1996–2000. Program Dostosowania Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego do Warunków Gospodarki Rynkowej i Międzynarodowej Konkurencyjności (Hard Coal Mining—Policy of the State and the Sector for 1996–2000. Program of Adjusting Hard Coal Mining to Market Economy and International Competitiveness Condition); Ministerstwo Przemysłu i Handlu (MPiH): Warszawa, Poland, 1996. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/49265 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MG 1998. Reforma Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce w Latach 1998–2002 (Hard Coal Mining Restructuring in Poland in 1998–2002); Ministerstwo Gospodarki (MG): Warszawa, Poland, 1998. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/51718 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MG 2000. Korekta Programu Rządowego „Reforma Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce w Latach 1998–2002 (Correction of the Government Program Hard Coal Mining Restructuring in Poland in 1998–2002); Ministerstwo Gospodarki (MG): Warszawa, Poland, 2000. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/51718 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MG 2002a. Program Restrukturyzacji Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce w Latach 2003–2006 z Wykorzystaniem Ustaw Antykryzysowych i Zainicjowaniem Prywatyzacji Niektórych Kopalń (Program of Hard Coal Mining Restructuring in Poland in 2003–2006 Using Anti-Crisis Acts and Initiating the Privatization of Selected Mines); Ministerstwo Gospodarki (MG): Warszawa, Poland, 2002. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/51718 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MG 2002b. Restrukturyzacja Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Latach 2004–2006 Oraz Strategia na lata 2007–2010 (Hard Coal Mining Restructuring in 2004–2006 and Strategy for 2007–2010); Ministerstwo Gospodarki (MG): Warszawa, Poland, 2002. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/51718 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- MGiP 2004. Plan Dostępu do Zasobów Węgla Kamiennego w Latach 2004–2006 Oraz Plan Zamknięcia Kopalń w Latach 2004–2007 (Plan of Access to Hard Coal Resources in 2004–2006 and the Plan of Closing down Mines in 2004–2007); Ministerstwo Gospodarki i Pracy (MGiP): Warszawa, Poland, 2004. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/51720 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- Fornalczyk, A.; Choroszczak, L.; Mikulec, M. Restrukturyzacja Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego (Restructuring of Hard Coal Mining); Poltext: Warszawa, Poland, 2008; pp. 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Polski Węgiel: Quo Vadis? Perspektywy Rozwoju Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce (Polish Coal: Quo Vadis? Prospects for Hard Coal Mining Development in Poland); Wise: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; pp. 1–48. Available online: https://wise-europa.eu/2015/06/15/polski-wegiel-quo-vadis-perspektywy-rozwoju-gornictwa-wegla-kamiennego-w-polsce/ (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Lisowski, A. Recovery Plan of Hard Coal Mining Industry and Better Use of Coal in the Polish Economy in the Future. Przegląd Górniczy 2015, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- MG 2006. Strategia Działalności Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce w Latach 2007–2015 (Strategy for Hard Coal Mining Operation in Poland in 2007–2015); Ministerstwo Gospodarki (MG): Warszawa, Poland, 2006. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/zespol/-/zespol/51718 (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Rybak, A.; Rybak, A. Analysis of the Main Coal Mining Restructuring Policy Objectives in the Light of Polish Mining Companies’ Ability to Change. Energies 2020, 13, 3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máca, V.; Melichar, J. The Health Costs of Revised Coal Mining Limits in Northern Bohemia. Energies 2016, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Cao, H.; Wang, C.; Yao, C. A System Dynamics Model for Ecological Environmental Management in Coal Mining Areas in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavloudakis, F.; Roumpos, C.; Karlopoulos, E.; Koukouzas, N. Sustainable Rehabilitation of Surface Coal Mining Areas: The Case of Greek Lignite Mines. Energies 2020, 13, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frejowski, A.; Bondaruk, J.; Duda, A. Challenges and Opportunities for End-of-Life Coal Mine Sites: Black-to-Green Energy Approach. Energies 2021, 14, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuss, M.; Makieła, Z.; Herdan, A.; Kuźniarska, G. The Corporate Social Responsibility of Polish Energy Companies. Energies 2021, 14, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.; Kuźniarska, A.; Makieła, Z.J.; Sławik, A.; Stuss, M.M. Does ESG Reporting Relate to Corporate Financial Performance in the Context of the Energy Sector Transformation? Evidence from Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raport 2019. Górnictwo Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce (Report 2019. Hard Coal Mining in Poland); Instytut Gospodarki Surowcami Mineralnymi i Energią PAN: Kraków, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://min-pan.krakow.pl/projekty/2018/07/31/raport-gornictwo-wegla-kamiennego-w-polsce-2017/ (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- ME 2018a. Program dla Sektora Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce (Program for Hard Coal Mining Sector in Poland); Ministerstwo Energii (ME): Warszawa, Poland, 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/aktywa-panstwowe/program-dla-sektora-gornictwa-wegla-kamiennego-w-polsce (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- ME 2021. Umowa Społeczna Dotycząca Transformacji Sektora Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego oraz Wybranych Procesów Transformacji Województwa Śląskiego (Social Agreement on the Transformation of the Hard Coal Mining Sector and Selected Transformation Processes in the Silesian Province); Ministerstwo Energii (ME): Warszawa, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/aktywa-panstwowe/umowa-spoleczna (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- ME 2018b. Program dla Sektora Górnictwa Węgla Brunatnego w Polsce (Program for Lignite Mining in Poland); Ministerstwo Energii (ME): Warszawa, Poland, 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/aktywa-panstwowe/rada-ministrow-przyjela-program-dla-sektora-gornictwa-wegla-brunatnego-w-polsce (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Kaczmarek, J. Mezostruktura Gospodarki Polski w Okresie Transformacji. Uwarunkowania, Procesy, Efektywność (Mesostructure of the Polish Economy during Transformation. Determinants, Processes, Efficiency); Difin Press: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 19–39, 59–80, 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Alves Dias, P.; Miranda Barbosa, E.; Peteves, E.; Vázquez Hernández, C.; Gonzalez Aparicio, I.; Kanellopoulos, K.; Kapetaki, Z.; Nijs, W.; Shortall, R.; Mandras, G.; et al. EU Coal Regions: Opportunities and Challenges Ahead; Joint Research Centre, EC: Luxembourg, 2018; pp. 1–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauers, H.; Oei, P.-Y.; Walk, P. Comparing coal phase-out pathways: The United Kingdom’s and Germany’s diverging transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 37, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, A.; Winterton, J.; Newby, M. The restructuring of the British coal industry. Camb. J. Econ. 1985, 9, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oei, P.-Y.; Brauers, H.; Herpich, P. Lessons from Germany’s hard coal mining phase-out: Policies and transition from 1950 to 2018. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlhorst, D. Germany’s energy transition policy between national targets and decentralized responsibilities. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2015, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, K.S.; Pfluger, B.; Geels, F.W. Transformative policy mixes in socio-technical scenarios: The case of the low-carbon transition of the German electricity system (2010–2050). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 151, 119259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnheim, B.; Geels, F.W. Regime destabilisation as the flipside of energy transitions: Lessons from the history of the British coal industry (1913–1997). Energy Policy 2012, 50, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, J. The Mechanisms of Creating Value vs. Financial Security of Going Concern—Sustainable Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.C.; Koski, J.L.; Mitton, T. Analysis for Financial Management, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 35–89. [Google Scholar]

- Block, S.; Hirt, G.; Danielsen, B. Foundations of Financial Management, 17th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 250–348. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrusewicz, W. Analiza Finansowa Przedsiębiorstwa. Teoria i Zastosowanie (Financial Analysis of the Enterprise. Theory and Application); Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; pp. 135–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, J. The concept and measurement of creating excess value in listed companies. Eng. Econ. 2018, 29, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlik, L. Koszty Bieżącej Produkcji Węgla Według Rozporządzeń Unii Europejskiej a Koszty Własne Sprzedanego Węgla Według Dotychczasowych Statystyk Górnictwa (Costs of Current Coal Production According to European Union Regulations versus the Costs of Sold Coal According to Previous Mining Statistics). Polityka Energetyczna 2004, 7, 409–420. Available online: https://se.min-pan.krakow.pl/publikacje/04_14lg_pe.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Jonek-Kowalska, I.; Turek, M. Dependence of Total Production Costs on Production and Infrastructure Parameters in the Polish Hard Coal Mining Industry. Energies 2017, 10, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiński, J.; Turek, M. Wybrane Aspekty Zmian Restrukturyzacyjnych w Polskim Górnictwie Węgla Kamiennego w Latach 1990–2008 (Selected Aspects of Restructuring Changes in Polish Hard Coal Mining in 1990–2008). Res. Rep. Min. Environ. 2009, 2, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, J. The effectiveness of working capital management strategies in manufacturing enterprises. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2019, 2019, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuksa, D. Innovative Method for Calculating the Break-Even for Multi-Assortment Production. Energies 2021, 14, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, B.; Bhar, C.; Mondal, S. Performance Assessment Based on the Relative Efficiency of Indian Opencast Coal Mines Using Data Envelopment Analysis and Malmquist Productivity Index. Energies 2020, 13, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, J.; Alonso, S.L.N.; Sokołowski, A.; Fijorek, K.; Denkowska, S. Financial threat profiles of industrial enterprises in Poland. Oecon. Copernic. 2021, 12, 463–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarski, S.; Kaczmarek, J. The Interdependencies of Processes Related to Cost Productivity and Fixed Asset Recovery. In Developmental Challenges of the Economy and Enterprises after Crisis; Kaczmarek, J., Kolegowicz, K., Eds.; Cracow University of Economics, Foundation of Cracow University of Economics: Cracow, Poland, 2014; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jonek-Kowalska, I. Long-term Analysis of the Effects of Production Management in Coal Mining in Poland. Energies 2019, 12, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, J. Uwarunkowania i Przebieg Procesu Likwidacji Kopalń Węgla Kamiennego (Determinants and the Process of Hard Coal Mines Liquidation). Studia Ekonomiczne Akademia Ekonomiczna w Katowicach 2006, 37, 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Tkocz, M. Effects of hard coal mining restructuring in Poland. Stud. Ind. Geogr. Comm. Pol. Geogr. Soc. 2006, 9, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamola-Cieślik, M. Bezpieczeństwo Energetyczne Polski a Sytuacja Ekonomiczna Kompanii Węglowej S.A. po 2014 roku (Energy Security of Poland and the Economic Situation of Kompania Węglowa S.A. after 2014). Bezpieczeństwo Teoria i Praktyka 2016, 1, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kamola-Cieślik, M. The Government’s Policy in the Field of Hard Coal Mining Restructuration as an Element of Poland’s Energy Security. Pol. Polit. Sci. Yearb. 2017, 46, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restructuring and Privatizing the Coal Industries in Central and Eastern Europe and the CIS; World Energy Council: London, UK, 2000; pp. 1–199. Available online: https://www.worldenergy.org/assets/downloads/PUB_Restructuring_and_privatizing_coal_in_CIES_2004_WEC.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Rutkiewicz, K. Restrukturyzacja górnictwa węgla kamiennego w Polsce w świetle zmian międzynarodowej polityki paliwowo-energetycznej latach 1989–2019 (Restructuring of hard coal mining in Poland in the light of changes in the international fuel and energy policy in 1989–2019). In Kierunki Polityki Gospodarczej w Warunkach Niestabilności Rynków; Żabiński, A., Żabiński, A., Eds.; Wyd. UE we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2021; pp. 92–107. Available online: https://bazawiedzy.upwr.edu.pl/info/article/UPWra890719440e54b71ae1ece893a173ca1/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Gwiazda, A. Restrukturyzacja górnictwa węgla kamiennego w Polsce—Aspekt organizacyjny (Restructuring of hard coal mining in Poland—Organizational aspect). Przegląd Organizacji 2011, 1, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makieła, Z. Wyniki Realizacji Programów Restrukturyzacji Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego po 1989 r. (Results of Hard Coal Mining Restructuring Programmes after 1989). Prace Komisji Geografii Przemysłu PTG 2020, 4, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Smoliło, J.; Chmiela, A.; Gajdzik, M.; Menéndez, J.; Loredo, J.; Turek, M.; Bernardo-Sánchez, A. A New Method to Analyze the Mine Liquidation Costs in Poland. Mining 2021, 1, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecka, U.; Śniegocki, A.; Wetmańska, Z. Ukryty Rachunek za Węgiel 2017. Wsparcie Górnictwa i Energetyki Węglowej w Polsce—Wczoraj, Dziś i Jutro (Hidden Coal Account 2017: Support for Coal Mining and Coal Energy in Poland—Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow); Wise Europa: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; pp. 1–44. Available online: https://wise-europa.eu/2017/09/19/ukryty-rachunek-wegiel-premiera-raportu/ (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Informacja o Wynikach Kontroli Restrukturyzacji Finansowej i Organizacyjnej Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Latach 1990–2001 (Information on the Results of the Audit of the Financial and Organizational Restructuring of the Hard Coal Mining Industry in the Years 1990–2001); NIK, Delegatura w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2002; pp. 1–81. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/kontrole/wyniki-kontroli-nik/kontrole,1186.html (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Ukryty Rachunek za Węgie (Hidden Coal Account); WiseEuropa: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; pp. 1–44. Available online: https://wise-europa.eu/2017/09/19/ukryty-rachunek-wegiel-premiera-raportu/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Funkcjonowanie Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Latach 2007–2015 na tle Założeń Programu Rządowego (Functioning of the Hard Coal Mining Sector in the Years 2007–2015 against the Background of the Government Programme); NIK, Delegatura w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2016; pp. 1–114. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/kontrole/P/15/074/LKA/ (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- How to Financially Support the Transition of Coal Regions in Europe with a View to the SDG; CEEweb for Biodiversity: Budapest, Hungary, 2017; pp. 1–30. Available online: https://www.ceeweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Transition-of-coal-regions.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Mokrzycki, E.; Ney, R.; Siemek, J. Global Reserves of Energy Fossil Resources—Conclusions for Poland. Rynek Energii 2008, 6, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge, D. Estimating long-term world coal production with logit and probit transforms. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2011, 85, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA 2016. Coal. Medium Term Market Report. Market Analysis and Forecast to 2021; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 1–141. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/medium-term-coal-market-report-2016 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Zhao, S.; Alexandroff, A. Current and future struggles to eliminate coal. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, K.; Beynont, H.; Hudson, R. Coalfields Regeneration: Dealing with the Conseąuences of Industrial Decline; The Policy Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- EC 2011. A Roadmap for Moving to a Competitive Low Carbon Economy in 2050; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/com/com_com(2011)0112_/com_com(2011)0112_pl.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- EP 2013. European Parliament Resolution of 14 March 2013 on the Energy Roadmap 2050, a Future with Energy; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2016; Available online: http://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52013IP0088 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- 2020 Climate & Energy Package; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2020-climate-energy-package_en (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- PEP 2040. Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040r. (PEP 2040 Energy Policy of Poland until 2040; Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/polityka-energetyczna-polski-do-2040-r-przyjeta-przez-rade-ministrow (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Fit for 55% Package; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0550 (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Green Deal. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en#key-steps (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Giunta, A.; Lagendijk, A.; Pike, A. Restructuring Industry and Territory. The Experience of Europe’s Regions; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, D.; Parry, D. Managing industrial decline: The lessons of a decade of research on industrial contraction and regeneration in Britain and other EU coal producing countries. Min. Technol. 2003, 112, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Hou, W.; Chang, J. Changing Coal Mining Brownfields into Green Infrastructure Based on Ecological Potential Assessment in Xuzhou, Eastern China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Zhu, Q.; Naseem, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Ivascu, L. Mining Industry Impact on Environmental Sustainability, Economic Growth, Social Interaction, and Public Health: An Application of Semi-Quantitative Mathematical Approach. Processes 2021, 9, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xiao, W. Quantifying the Impacts of Coal Mining and Soil-Water Conservation on Runoff in a Typical Watershed on the Loess Plateau, China. Water 2021, 13, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaczmarek, J. The Balance of Outlays and Effects of Restructuring Hard Coal Mining Companies in Terms of Energy Policy of Poland PEP 2040. Energies 2022, 15, 1853. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15051853

Kaczmarek J. The Balance of Outlays and Effects of Restructuring Hard Coal Mining Companies in Terms of Energy Policy of Poland PEP 2040. Energies. 2022; 15(5):1853. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15051853

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaczmarek, Jarosław. 2022. "The Balance of Outlays and Effects of Restructuring Hard Coal Mining Companies in Terms of Energy Policy of Poland PEP 2040" Energies 15, no. 5: 1853. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15051853

APA StyleKaczmarek, J. (2022). The Balance of Outlays and Effects of Restructuring Hard Coal Mining Companies in Terms of Energy Policy of Poland PEP 2040. Energies, 15(5), 1853. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15051853