Sustainable Hydrogen Production from Seawater Electrolysis: Through Fundamental Electrochemical Principles to the Most Recent Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

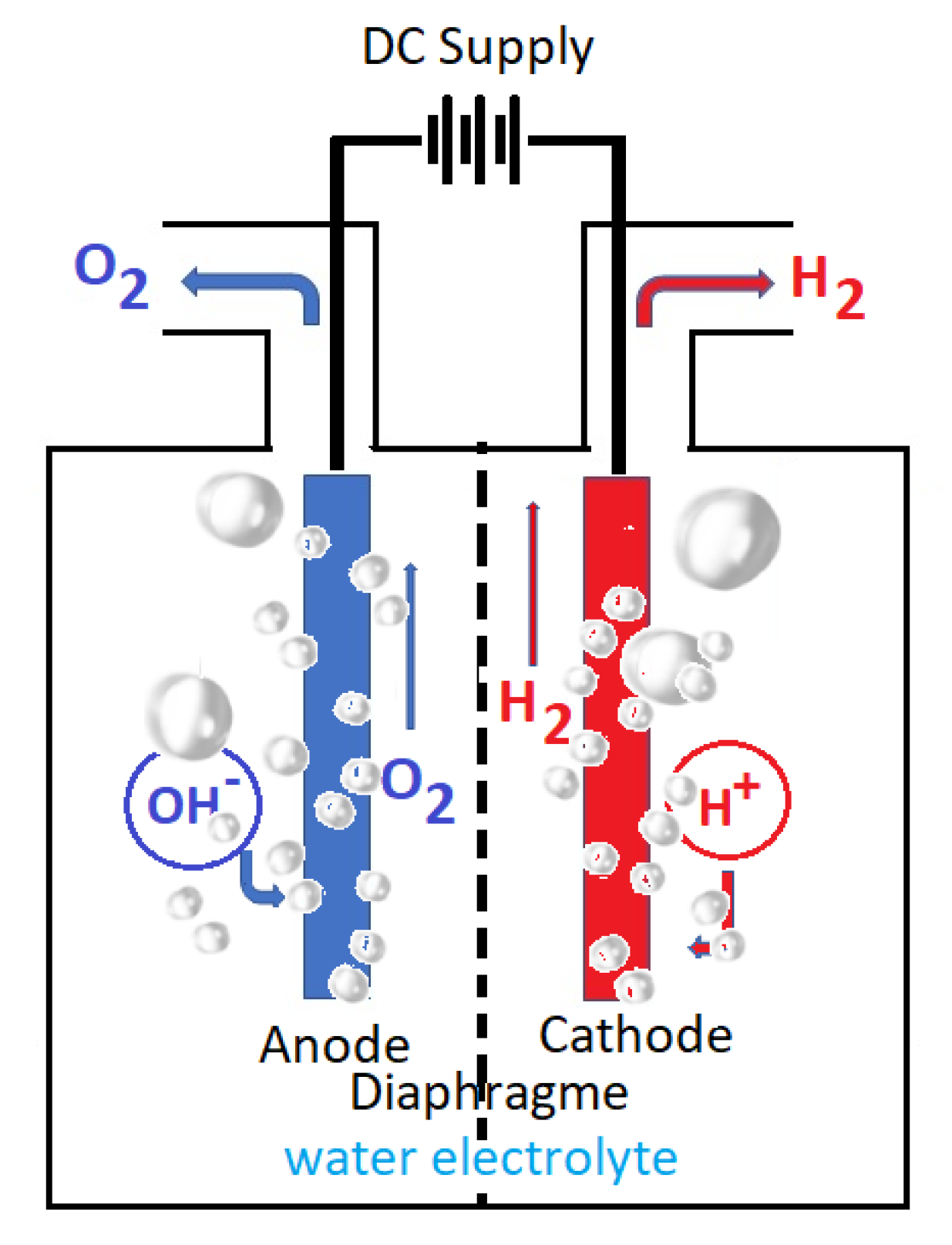

2. An Overview of Water Electrochemistry

2.1. Thermodynamic Considerations: The Theoretical Voltage of Water Decomposition

2.2. Balance of Voltage

2.3. The Electrode Separated Gases

2.4. The Consumed Water during Electrolysis

2.5. Thermal and Electrical Balance

2.6. Transport and Electrical Resistance

2.7. Polarization of the Electrodes

- -

- the cathodic polarization is negative (ηc < 0), and the net cathodic current density, iK, is given by the equation:

- -

- the anodic polarization, ηa > 0, and the anodic net current density, iA, is given by the equation:

2.8. Main Water Electrolysis Cell Types

2.8.1. Alkaline Electrolyzer

2.8.2. PEM Electrolyzer

2.8.3. Solid Oxide Electrolyzer

3. Newest Trends in Seawater Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production

3.1. Specificity of Seawater Electrolysis

- -

- Electrolysis to produce alkalis, hydrogen, and oxygen.

- -

- Electrolysis to produce alkalis, hydrogen, oxygen, and chlorine.

- -

- Electrolysis to produce hydrogen and sodium hypochlorite (NaClO).

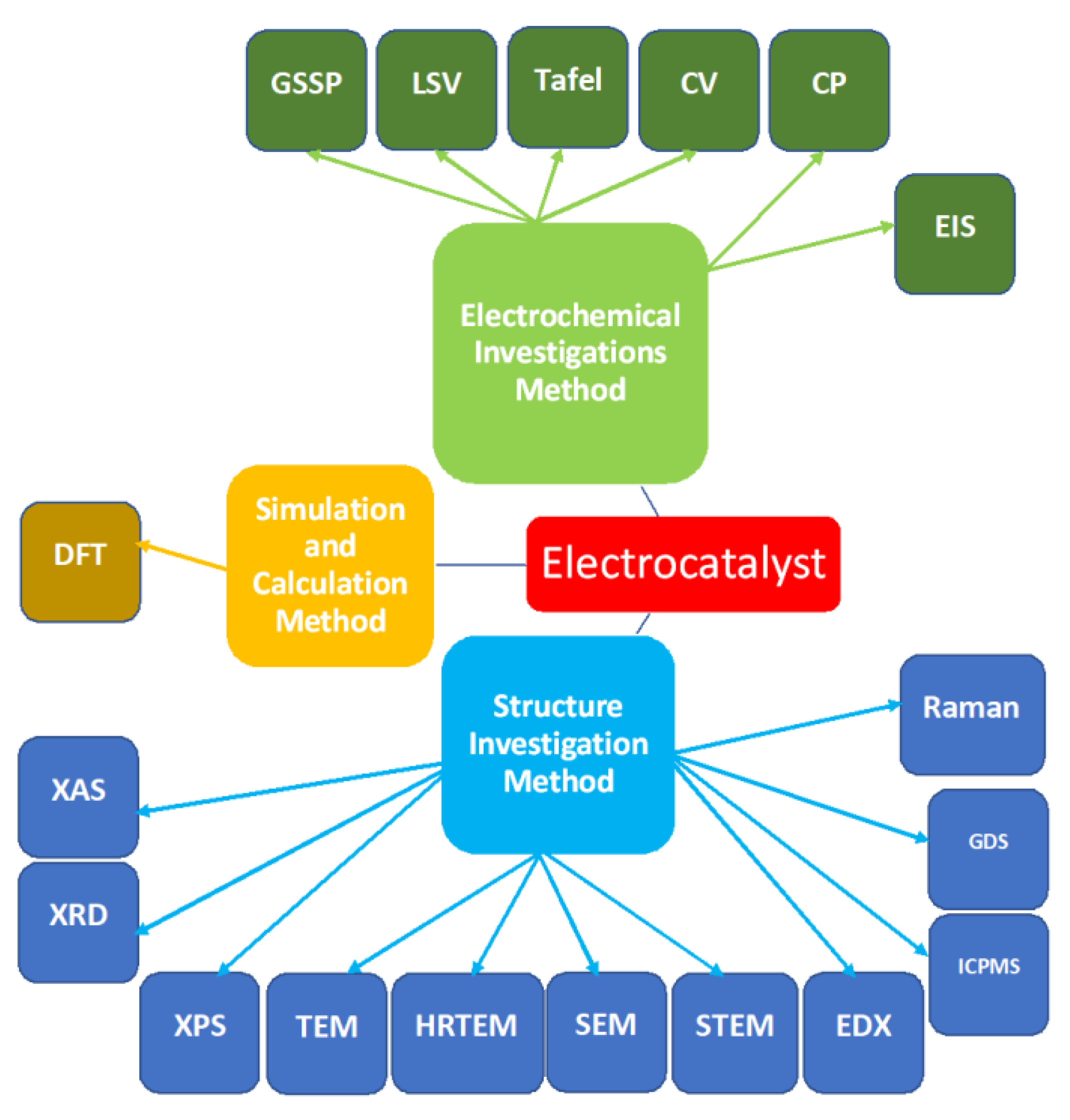

3.2. Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Production

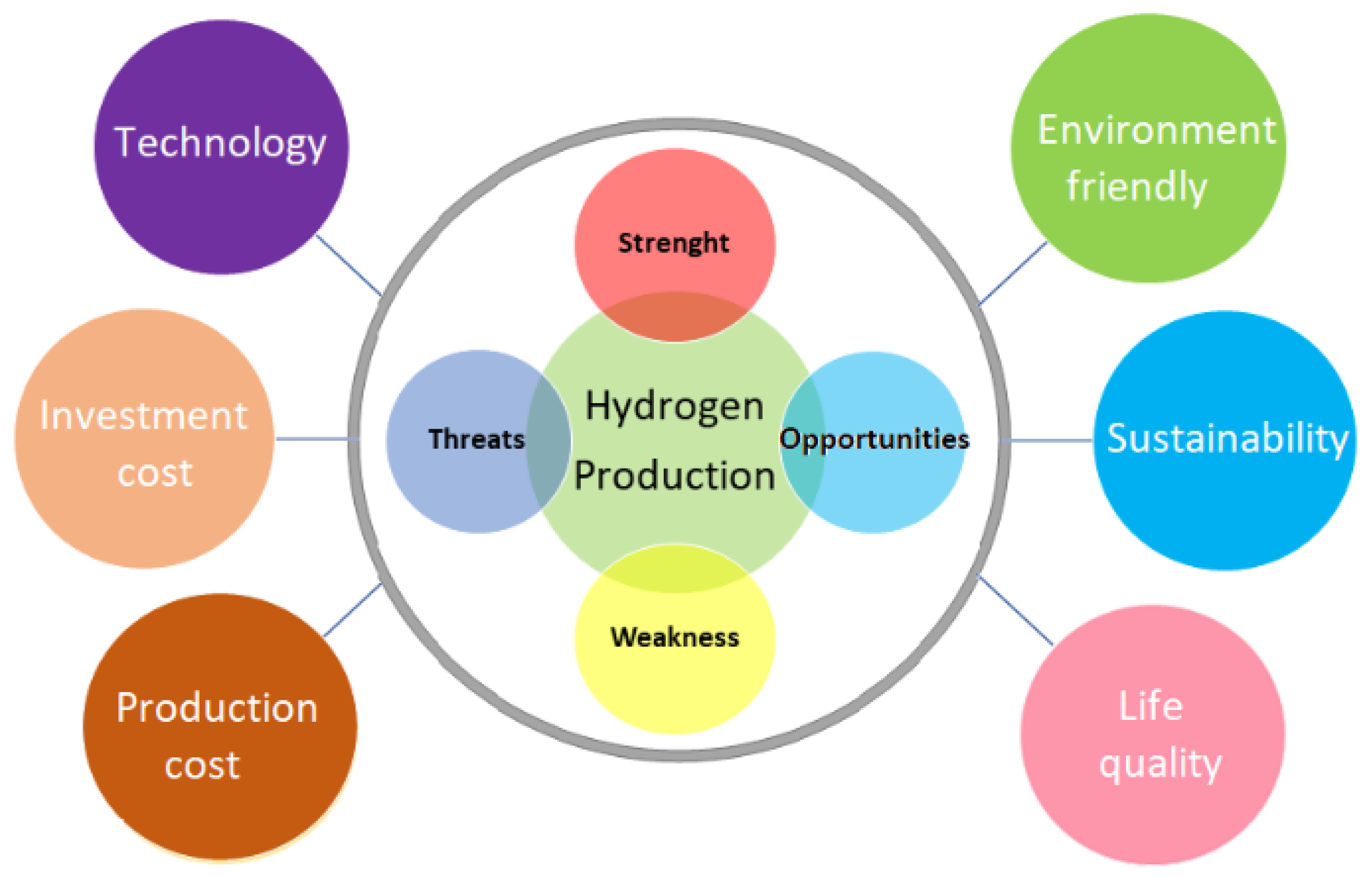

3.3. Economic Considerations

3.4. Environmental Considerations

3.5. Emergent Electrochemical Technologies for Seawater

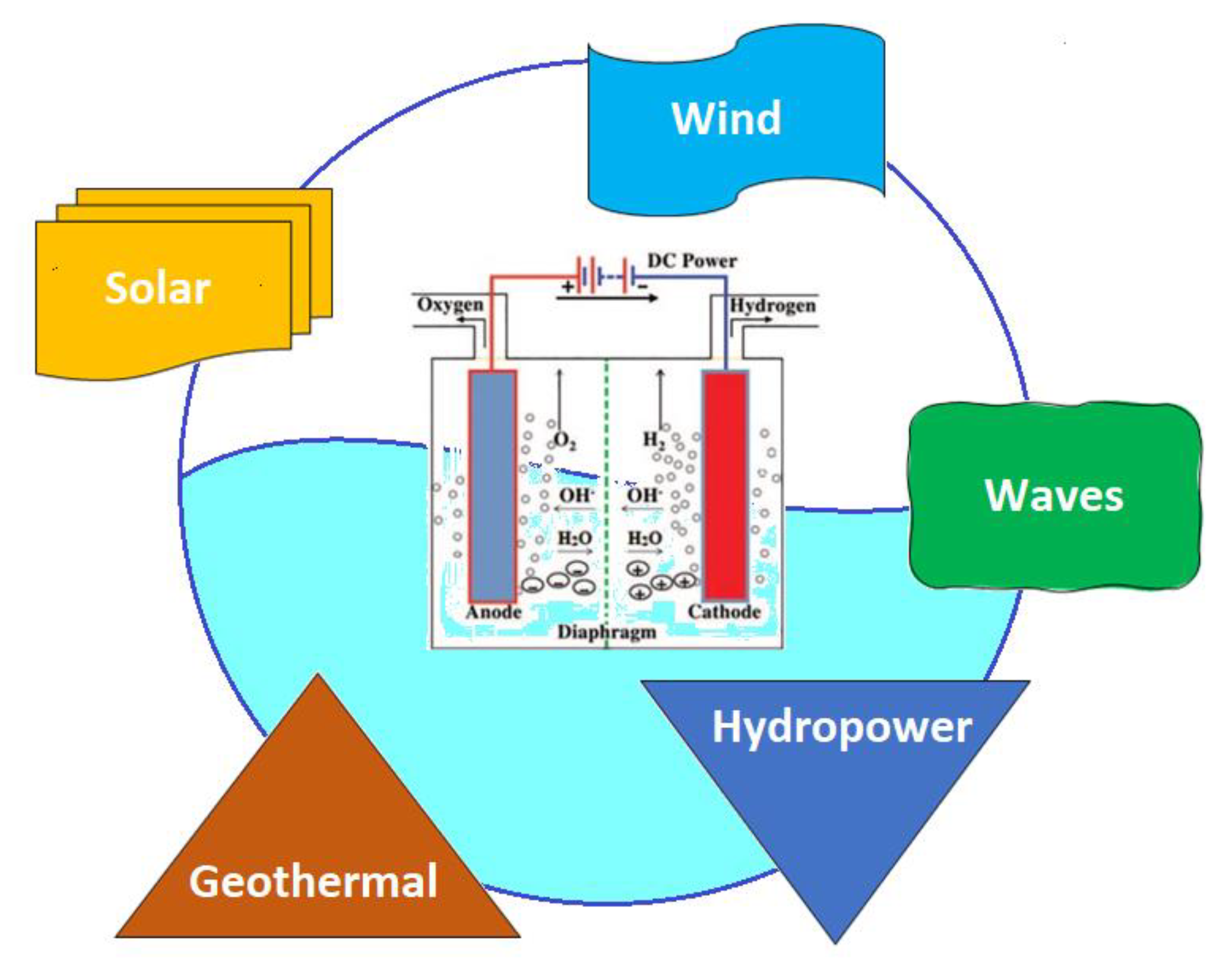

3.6. Renewables Energies for Seawater Electrolysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, S.; Lu, A.; Zhong, C.-J. Hydrogen production from water electrolysis: Role of catalysts. Nano Converg. 2021, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmo, M.; Fritz, D.L.; Mergel, J.; Stolten, D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4901–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, Y.; Antar, A. Hydrogen Generation by Water Electrolysis. In Advances In Hydrogen Generation Technologies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.; Khaloofah Al Mesfer, M.; Naseem, H.; Danish, M. Hydrogen Production by Water Electrolysis: A Review of Alkaline Water Electrolysis, PEM Water Electrolysis and High Temperature Water Electrolysis. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. (IJEAT) 2015, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, G.; Cronin, L. Hydrogen from Water Electrolysi s School of Chemistry, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom. 2016. Available online: http://www.chem.gla.ac.uk/cronin/images/pubs/Chisholm-Chapter_16_2016.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Hora, C.; Dan, F.C.; Rancov, N.; Badea, G.E.; Secui, C. Main Trends and Research Directions in Hydrogen Generation Using Low Temperature Electrolysis: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2022, 15, 6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Orosa, L.; Chinarro, E.; Guinea, D.; García-Alegre, M.C. Hydrogen Production by Wastewater Alkaline Electro-Oxidation. Energies 2022, 15, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, B.; Squires, D.; Barton, J.; Strickland, D.; Wijayantha, K.G.U.; Carroll, J.; Wilson, J.; Brenton, M.; Thomson, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of Low Carbon Hydrogen Production from Offshore Wind Using Battolyser Technology. Energies 2022, 15, 5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, S.U. Theoretical Basis of Electrocatalysis. In Electrocatalysts for Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Evolution-Theory to Design; Ray, A., Mukhopadhyay, I., Pati, R.K., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wei, W.; Song, L.; Ni, B.-J. Hybrid Water Electrolysis: A New Sustainable Avenue for Energy-Saving Hydrogen Production. Sustain. Horiz. 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, A.; Karishma, S.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Yaashikaa, P.R.; Jeevanantham, S.; Gayathri, B. Microbial electrolysis cells and microbial fuel cells for biohydrogen production: Current advances and emerging challenges. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Mehta, N.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Hefny, M.; Al-Hinai, A.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Rooney, D.W. Hydrogen production, storage, utilisation and environmental impacts: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 20, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarahy, A.M.; Eloffy, M.G.; Hammad, A.; Saber, A.N.; El-Sherif, D.M.; Mohsen, A.; Abouzid, M.; Elwakeel, K.Z. Hydrogen production from wastewater, storage, economy, governance and applications: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, F.; Anda, M.; Shafiullah, G.M. Hydrogen production for energy: An overview. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 3847–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Jiao, Z.; Bai, S.; Qiu, H.; Guo, L. Photochemical Systems for Solar-to-Fuel Production. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2022, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, J.; Zhong, C.; Deng, Y.; Han, X.; Hu, W. Recent progresses of micro-nanostructured transition metal compound-based electrocatalysts for energy conversion technologies. Sci. China Mater. 2021, 64, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Weng, C.-C.; Ren, J.-T.; Yuan, Z.-Y. An overview and recent advances in electrocatalysts for direct seawater splitting. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2021, 15, 1408–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Zhao, H.; Zou, W.; Chen, Z.; Cao, W.; Fang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Recent Progresses in Electrocatalysts for Water Electrolysis. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2018, 1, 483–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, X.; Jiao, L. PEM water electrolysis for hydrogen production: Fundamentals, advances, and prospects. Carbon Neutrality 2022, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhou, W. Water Splitting: From Electrode to Green Energy System. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Wang, D.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Hwang, B.-J.; Dai, H. A mini review on nickel-based electrocatalysts for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Res. 2015, 9, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, S.M.; Müller, M.; Robinius, M.; Stolten, D. The investment costs of electrolysis–A comparison of cost studies from the past 30 years. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, M.F.; Sarigul-Klijn, N. Hydrogen Production Methods. In The Green Energy Ship Concept; SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, D.V. Membraneless Electrolyzers for Low-Cost Hydrogen Production in a Renewable Energy Future. Joule 2017, 1, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilion, F. Hybrid renewable energy systems for desalination. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Khan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Djire, A. Recent development in electrocatalysts for hydrogen production through water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 32284–32317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, G.; Opitz, A.K.; Kogler, S.; Fleig, J. Correlation between hydrogen production rate, current, and electrode overpotential in a solid oxide electrolysis cell with La0.6Sr0.4FeO32d thin-film cathode. Monatsh Chem. 2014, 145, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaliere, P. Hydrogen from Electrolysis. In Hydrogen Assisted Direct Reduction of Iron Oxides; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 185–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp, S.; Thanh, N.; Klingenhof, M.; Bruckner, S.; Hauke, P.; Strasser, P. Efficient direct seawater electrolysers using selective alkaline NiFe-LDH as OER catalyst in asymmetric electrolyte feeds. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucera, J. Desalination: Water from Water; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Badea, G.E.; Maior, I.; Cojocaru, A.; Corbu, I. The cathodic evolution of Hydrogen on nickel in artificial seawate. Rev. Roum. De Chim. 2007, 52, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Cojocaru, A.; Badea, G.E.; Maior, I.; Cret, P.; Badea, T. Kinetics of the Hydrogen evolution reaction on 18Cr-10Ni stainless steel in artificial seawater. Part I. Influence of potential. Rev. Roum. De Chim. 2009, 54, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Badea, G.E.; Maior, I.; Cojocaru, A.; Pantea, I.; Badea, T. Kinetics of the Hydrogen evolution reaction on 18Cr-10Ni stainless steel in artificial seawater. Part II. Influence of temperature. Rev. Roum. De Chim. 2009, 54, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, W.; Sun, T.; Yang, T.; Xi, S.; Waqar, M.; Kou, Z.; Lyu, Z.; Feng, Y.P.; Wang, J.; Pennycook, S.J. Efficient hydrogen evolution of oxidized Ni-N3 defective sites for alkaline freshwater and seawater electrolysis. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2003846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Qin, J.; Wang, Z.; Yu, M.; Wu, X.; Sun, X.; Qiu, J. Energy-saving hydrogen production by chlorine-free hybrid seawater splitting coupling hydrazine degradation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Han, C.; Cui, Y.; Sang, S.; Liu, K.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q. Hydrophilic NiFe-LDH/Ti3C2Tx/NF electrode for assisting efficiently oxygen evolution reaction. J. Solid State Chem. 2021, 295, 121943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, V.V.; Podlovchenko, B.I.; Frolov, K.V.; Volkov, M.A.; Khanin, D.A. A new promising Pt(Mo2C) catalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction prepared by galvanic displacement reaction. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2022, 26, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, S.; Ebrahimi, S.; Niasar, M.S. Commercial materials as cathode for hydrogen production in microbial electrolysis cell. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 36, 1987–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, S.H.; Miao, J.W.; Zhang, L.P.; Gao, J.; Wang, H.; Tao, H.; Hung, S.; Vasileff, V.; Qiao, S.Z.; Liu, B. An earth-abundant catalyst-based seawater photoelectrolysis system with 17.9% solar-to-hydrogen efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Jin, B.; Zheng, Y.; Jin, H.; Jiao, Y.; Qiao, S. Charge State Manipulation of Cobalt Selenide Catalyst for Overall Seawater Electrolysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jin, B.; Vasileff, A.; Jiao, Y.; Qiao, S.-Z. Interfacial nickel nitride/sulfide as a bifunctional electrode for highly efficient overall water/seawater electrolysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 8117–8121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Lang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Kong, W.; Peng, O.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Cheng, J.; He, T.; Amini, A.; et al. Polyoxometalate-Derived Hexagonal Molybdenum Nitrides (MXenes) Supported by Boron, Nitrogen Codoped Carbon Nanotubes for Efficient Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution from Seawater. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1805893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golgovici, F.; Pumnea, A.; Petica, A.; Manea, A.C.; Brincoveanu, O.; Enachescu, M.; Anicai, L. Ni–Mo alloy nanostructures as cathodic materials for hydrogen evolution reaction during seawater electrolysis. Chem. Pap. 2018, 72, 1889–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhu, Q.; Song, S.; McElhenny, B.; Wang, D.; Wu, C.; Qin, Z.; Bao, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. Non-noble metal-nitride based electrocatalysts for high-performance alkaline seawater electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, F.; Reier, T.; Pawolek, Z.; Gliech, M.; Strasser, P. Design Criteria, Operating Conditions, and Nickel-Iron Hydroxide Catalyst Materials for Selective Seawater Electrolysis. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Pei, W.; Yang, P.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, J. Engineering Multifunctional Collaborative Catalytic Interface Enabling Efficient Hydrogen Evolution in All pH Range and Seawater. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Li, G.D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Feng, L.L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Zou, X. Electrocatalytic H2 production from seawater over Co, N-codoped nanocarbons. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 2306–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresp, S.; Dionigi, F.; Loos, S.; Ferreira de Araujo, J.; Spöri, C.; Gliech, M.; Dau, H.; Strasser, P. Direct electrolytic splitting of seawater: Activity, selectivity, degradation, and recovery studied from the molecular catalyst structure to the electrolyzer cell level. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1800338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wu, L.B.; McElhenny, B.; Song, S.W.; Luo, D.; Zhang, F.H.; Yu, Y.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z.F. Ultrafast room-temperature synthesis of porous S-doped Ni/Fe (oxy)hydroxide electrodes for oxygen evolution catalysis in seawater splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 3439–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Z.; Zhu, M.Z.; Cao, Z.Y.; Zhu, P.; Cao, Q.; Xu, X.Y.; Xu, C.X.; Yin, Z.Y. Heterogeneous bimetallic sulfides based seawater electrolysis towards stable industrial-level large current density. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 291, 120071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayen, P.; Saha, S.; Ramani, V. Selective seawater splitting using pyrochlore electrocatalyst. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 3978–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.J.; Zhao, X.J.; Miao, J.; Yang, W.T.; Wang, C.T.; Pan, Q.H. ZIF-L-Co@carbon fiber paper composite derived Co/Co3O4@C electrocatalyst for ORR in alkali/acidic media and overall seawater splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 33028–33036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.H.; Lin, C.Y. Iron phosphate modified calcium iron oxide as an efficient and robust catalyst in electrocatalyzing oxygen evolution from seawater. Faraday Discuss. 2019, 215, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.R.; Kumar, A.; Lee, J.J.; Yang, T.H.; Na, S.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Luo, Y.G.; Liu, X.H.; Hwang, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Stable complete seawater electrolysis by using interfacial chloride ion blocking layer on catalyst surface. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 2020, 8, 24501–24514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Kenney, M.J.; Meng, Y.; Hung, W.H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.E.; Prasanna, R.; Li, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Solar-driven, highly sustained splitting of seawater into hydrogen and oxygen fuels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 6624–6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Z.; Sato, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Izumiya, K.; Kumagai, N.; Hashimoto, K. Electrochemical characterization of degradation of oxygen evolution anode for seawater electrolysis. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 116, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.J.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Xi, H.; Li, C.H. Seawater splitting for hydrogen evolution by robust electrocatalysts from secondary M(M = Cr, Fe, Co, Ni, Mo) incorporated Pt. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 9423–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.Y.; Tang, Q.W.; He, B.L.; Yang, P.Z. Robust electrocatalysts from an alloyed Pt-Ru-M (M = Cr, Fe, Co, Ni, Mo)-decorated Ti mesh for hydrogen evolution by seawater splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 2016, 4, 6513–6520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Cui, Z.; Zhu, S.; Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Liang, Y. Structure engineering of electrodeposited NiMo films for highly efficient and durable seawater splitting. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 365, 137366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Liu, X.; Vasileff, A.; Jiao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.Z. Single-crystal nitrogen-rich two-dimensional Mo5N6 nanosheets for efficient and stable seawater splitting. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 12761–12769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wu, L.B.; Song, S.W.; McElhenny, B.; Zhang, F.H.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z.F. Hydrogen generation from seawater electrolysis over a sandwich-like NiCoN|NixP|NiCoN microsheet array catalyst. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 2681–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shi, J. Co-electrolysis toward value-added chemicals. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrin, R.A.; Dincer, I. A Novel Multigeneration Energy System for a Sustainable Community. In Environmentally-Benign Energy Solutions. Green Energy and Technology; Dincer, I., Colpan, C., Ezan, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K. Key Materials for Global Carbon Dioxide Recycling. In Global Carbon Dioxide Recycling; SpringerBriefs in Energy; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Q.; Guo, J.; Feng, X.; et al. Synergetic Function of the Single-Atom Ru–N4 Site and Ru Nanoparticles for Hydrogen Production in a Wide pH Range and Seawater Electrolysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 15250–15258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Song, H.; Chang, J.; Lu, S. N-doped carbon dots coupled NiFe-LDH hybrids for robust electrocatalytic alkaline water and seawater oxidation. Nano Res. 2020, 15, 7063–7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Song, L.; Tang, M.; Feng, Z. Oxygen Evolution Efficiency and Chlorine Evolution Efficiency for Electrocatalytic Properties of MnO2-based Electrodes in Seawater. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2019, 34, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszczyńska, A.; Szczygieł, I. Electrocatalytic activity for the hydrogen evolution of the electrodeposited Co–Ni–Mo, Co–Ni and Co–Mo alloy coatings. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 45, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Buch, C.; Herraiz-Cardona, I.; Ortega, E.; García-Antón, J.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Study of the catalytic activity of 3D macroporous Ni and NiMo cathodes for hydrogen production by alkaline water electrolysis. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2016, 46, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Qin, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, C. V-doped Ni3N/Ni heterostructure with engineered interfaces as a bifunctional hydrogen electrocatalyst in alkaline solution: Simultaneously improving water dissociation and hydrogen adsorption. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 3489–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Ning, P.; Xin, P.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Uvdal, K.; Hu, Z. Nested hollow architectures of nitrogen-doped carbon-decorated Fe, Co, Ni-based phosphides for boosting water and urea electrolysis. Nano Res. 2021, 15, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, C.; Xu, S.; Huang, M.; Wen, Y.; Shi, X.-R. DFT-assisted rational design of CoMxP/CC (M = Fe, Mn, and Ni) as efficient electrocatalyst for wide pH range hydrogen evolution and oxygen evolution. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8897–8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Liang, J.; Luo, Y.; Cui, G.; Tang, B.; Liu, Q.; Yan, X.; Hao, H.; et al. Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles encapsulated in conductive nanowire array for high-performance alkaline seawater oxidation. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 6084–6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; He, H.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Z.; Ma, N.; Wang, B.; Zheng, L.; Li, R.; Wei, Y.; et al. Interface construction of NiCo LDH/NiCoS based on the 2D ultrathin nanosheet towards oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 4986–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Ren, G.; Cheng, T.; Xu, Y.; Huang, X. The exclusive surface and electronic effects of Ni on promoting the activity of Pt towards alkaline hydrogen oxidation. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 5865–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, G.; Ji, Q.; Qu, J.; Liu, H. Arrayed Cobalt Phosphide Electrocatalyst Achieves Low Energy Consumption and Persistent H2 Liberation from Anodic Chemical Conversion. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yu, Q.; Zhai, X.; Chi, J.; Cui, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, J.; Wang, L. Reduction-induced interface reconstruction to fabricate MoNi4-based hollow nanorods for hydrazine oxidation assisted energy-saving hydrogen production in seawater. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8846–8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Dong, K.; Fang, X.; Zheng, D.; Alshehri, A.A.; Sun, X. N, O-doped carbon foam as metal-free electrocatalyst for efficient hydrogen production from seawater. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8922–8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutyła, D.; Palarczyk, M.; Kołczyk, K.; Kowalik, R.; Żabiński, P. Electrodeposition of Electroactive Co–B and Co–B–C Alloys for Water Splitting Process in 8 M NaOH Solutions. Electrocatalysis 2017, 9, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Yan, H.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Xie, Y.; Wu, A.; Jiang, L.; Tian, C.; Wang, R.; et al. Multi-touch cobalt phosphide-tungsten phosphide heterojunctions anchored on reduced graphene oxide boosting wide pH hydrogen evolution. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Chi, J.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Deng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Dual-strategy of hetero-engineering and cation doping to boost energy-saving hydrogen production via hydrazine-assisted seawater electrolysis. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manazoğlu, M.; Hapçı, G.; Orhan, G. Electrochemical Deposition and Characterization of Ni-Mo Alloys as Cathode for Alkaline Water Electrolysis. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2015, 25, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Liu, Y.; Peng, S.; Lan, F.; Lu, S.; Xiang, Y. Effects of bicarbonate and cathode potential on hydrogen production in a biocathode electrolysis cell. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2013, 8, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, P.; Xing, W. Cobalt nitride nanoflakes supported on Ni foam as a high-performance bifunctional catalyst for hydrogen production via urea electrolysis. J. Chem. Sci. 2019, 131, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, L.; Li, Y. Phosphorus-induced electronic structure reformation of hollow NiCo2Se4 nanoneedle arrays enabling highly efficient and durable hydrogen evolution in all-pH media. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8771–8782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Li, S.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Guan, J. Advances and challenges in two-dimensional materials for oxygen evolution. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8714–8750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, M.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D. A self-supported heterogeneous bimetallic phosphide array electrode enables efficient hydrogen evolution from saline water splitting. Nano Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, W.; Feng, X.; Wang, B. Synergizing high valence metal sites and amorphous/crystalline interfaces in electrochemical reconstructed CoFeOOH heterostructure enables efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8857–8864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Z.; Lin, W.; Yang, X.; Gu, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhuang, Z. Improving the water electrolysis performance by manipulating the generated nano/micro-bubbles using surfactants. Nano Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tian, X.; Feng, L. Efficient bifunctional catalysts of CoSe/N-doped carbon nanospheres supported Pt nanoparticles for methanol electrolysis of hydrogen generation. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8936–8945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Chang, G.-R.; Feng, Y.; Yao, X.-Z.; Yu, X.-Y. Regulating Ni site in NiV LDH for efficient electrocatalytic production of formate and hydrogen by glycerol electrolysis. Rare Met. 2022, 41, 1583–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Záchenská, J.; Jorík, V.; Vančo, L.; Mičušík, M.; Zemanová, M. Ni–Fe Cathode Catalyst in Zero-Gap Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Electrocatalysis 2022, 13, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ren, J.T.; Yuan, Z.Y. Interface engineering for boosting electrocatalytic performance of CoP-Co2P polymorphs for all-pH hydrogen evolution reaction and alkaline overall water splitting. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Lan, C.; Chen, B.; Wang, F.; Liu, T. Noble-metal-free catalyst with enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction activity based on granulated Co-doped Ni-Mo phosphide nanorod arrays. Nano Res. 2020, 13, 3321–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Hu, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Chen, F.; Hu, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Deng, Y.; Qin, Z.; et al. Heterogeneous lamellar-edged Fe-Ni(OH)2/Ni3S2 nanoarray for efficient and stable seawater oxidation. Nano Res. 2020, 14, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, G.; Xu, G.; Li, J.; Ye, X.; Gao, H. Highly selective electrocatalytic Cl− oxidation reaction by oxygen-modified cobalt nanoparticles immobilized carbon nanofibers for coupling with brine water remediation and H2 production. Nano Res. 2020, 14, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Bai, X.; Tang, T. Recent progress and prospect of carbon-free single-site catalysts for the hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Nano Res. 2021, 15, 818–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, W.; Xu, G.; Ma, T.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L. Corrosive-coordinate engineering to construct 2D-3D nanostructure with trace Pt as efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Sci. China Mater. 2021, 65, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; An, Y.; Xu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Yuan, W. Activating lattice oxygen of two-dimensional MnXn−1O2 MXenes via zero-dimensional graphene quantum dots for water oxidation. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 3053–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, D.; Xu, Y. Mn-doped NiP: Facile synthesis and enhanced electrocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Z.; Song, G.-L.; Wu, P.; Zheng, D. A corrosion-reconstructed and stabilized economical Fe-based catalyst for oxygen evolution. Nano Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Staffell, I.; Hawkes, A.; Nelson, J.; Few, S. Future cost and performance of water electrolysis: An expert elicitation study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30470–30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tontu, M. Performance assessment and economic evaluation of trigeneration energy system driven by the waste heat of coal-fired power plant for electricity, hydrogen and freshwater production. J Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headley, A.; Randolf, G.; Virji, M.; Ewan, M. Valuation and cost reduction of behind-the-meter hydrogen production in Hawaii. MRS Energy Sustain. 2020, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musharavati, F.; Ahmadi, P.; Khanmohammadi, S. Exergoeconomic assessment and multiobjective optimization of a geothermal-based trigeneration system for electricity, cooling, and clean hydrogen production. J. Therm. Anal. 2021, 145, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhai, B.; Mu, H.; Peng, X.; Wang, C.; Patwary, A.K. Evaluating an economic application of renewable generated hydrogen: A way forward for green economic performance and policy measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 15144–15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menin, L.; Benedetti, V.; Patuzzi, F.; Baratieri, M. Techno-economic modeling of an integrated biomethane-biomethanol production process via biomass gasification, electrolysis, biomethanation, and catalytic methanol synthesis. Biomass-Convers. Biorefinery 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, M.G.; Hazrat, M.A.; Sattar, M.A.; Jahirul, M.I.; Shearer, M.J. The future of hydrogen: Challenges on production, storage and applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 272, 116326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serag, S.; Echchelh, A. Technical and Economic Study for Electricity Production by Concentrated Solar Energy and Hydrogen Storage. Technol. Econ. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy 2022, 7, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Wang, L. Revisiting solar hydrogen production through photovoltaic-electrocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Front. Energy 2021, 15, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamaki, K.; Watanabe, A.; Usui, S.; Matsuda, H.; Sakashita, W.; Kato, R.; Endo, H.; Sato, M. Photoelectrochemical visible light zero-bias hydrogen generation with membrane-based cells designed for decreasing overall water electrolysis voltage and water dissociation: The second stage. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2019, 49, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Zhang, S.; Deng, S.; An, D.; Hoang, N.B. Impact factors and novel strategies for improving biohydrogen production in microbial electrolysis cells. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 346, 126588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.; Mubashar, R.; Irshad, M.; Gillani, S.; Tahir, M.B.; Khalid, N.R.; Yasmin, A.; Shehzad, M.A. A Comprehensive Study on Methods and Materials for Photocatalytic Water Splitting and Hydrogen Production as a Renewable Energy Resource. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 3837–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Hori, T.; Teranishi, S.; Nagao, M.; Hibino, T. Intermediate-temperature electrolysis of energy grass Miscanthus sinensis for sustainable hydrogen production. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Bhatnagar, P.; Dhingra, S.; Upadhyay, U.; Sreedhar, I. Wastewater treatment and energy production by microbial fuel cells. Biomass-Convers. Biorefinery 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, K. Hydrogen production with sea water electrolysis using Norwegian offshore wind energy potentials. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2014, 5, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Herrero, I.; Margallo, M.; Onandía, R.; Aldaco, R.; Irabien, A. Connecting wastes to resources for clean technologies in the chlor-alkali industry: A life cycle approach. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2017, 20, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yao, W.; Wang, J.; Cui, Z. Thermodynamic Analysis of Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Based Combined Cooling, Heating, and Power System Integrated with Solar-Assisted Electrolytic Cell. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, M.K.; Nijhawan, P.; Oberoi, A.S. Hydrogen fuel and fuel cell technology for cleaner future: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 15607–15626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, C.; Sun, S.; Huang, Y.; Meng, G.; Han, A.; Liu, J. Mesoporous Fe3O4@C nanoarrays as high-performance anode for rechargeable Ni/Fe battery. Sci. China Mater. 2020, 64, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Zhang, C.; Yin, K.; Zhao, M.; Du, Y.; Wu, Q.; Lu, X. A new high-performance rechargeable alkaline Zn battery based on mesoporous nitrogen-doped oxygen-deficient hematite. Sci. China Mater. 2021, 65, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Q.; Ba, D.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. Recent advances in materials and device technologies for aqueous hybrid supercapacitors. Sci. China Mater. 2021, 65, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rarotra, S.; Mandal, T.K.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Microfluidic Electrolyzers for Production and Separation of Hydrogen from Sea Water using Naturally Abundant Solar Energy. Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, M.R.; Meghdadi Isfahani, A.H.; Kumar, R.; Mohammadidoust, A.; Bewoor, A. Thermal performance analysis of a novel solar-assisted multigeneration system for hydrogen and power generation using corn stalk as biomass. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Qolipour, M.; Momeni, M. Energy supply for water electrolysis systems using wind and solar energy to produce hydrogen: A case study of Iran. Front. Energy 2019, 13, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, P.D.; Perrone, A.; Silvello, A. Water Electrolysis for the Production of Hydrogen to Be Employed in the Ironmaking and Steelmaking Industry. Metals 2021, 11, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, R.; Das, P. A Review on Architecture, Performance and Reliability of Hybrid Power System. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. B 2020, 101, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furfari, S.; Clerici, A. Green hydrogen: The crucial performance of electrolysers fed by variable and intermittent renewable electricity. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y. Industrial hydrogen production technology and development status in China: A review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, K.; Liu, C.; Cao, X.; Sun, H.; Dong, Y. Analysis, Modeling and Control of a Non-grid-connected Source-Load Collaboration Wind-Hydrogen System. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 2355–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, H.; Lakouraj, M.M.; Liu, J. Techno-economic feasibility evaluation of a standalone solar-powered alkaline water electrolyzer considering the influence of battery energy storage system: A Korean case study. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 38, 1617–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Jha, B.; Panda, M.K. Operation and Control of a Hybrid Isolated Power System with Type-2 Fuzzy PID Controller. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 2018, 42, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirkoohi, M.G.; Tyagi, R.D.; Vanrolleghem, P.A.; Drogui, P. Artificial intelligence techniques in electrochemical processes for water and wastewater treatment: A review. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidas, L.; Castro, R. Recent Developments on Hydrogen Production Technologies: State-of-the-Art Review with a Focus on Green-Electrolysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauns, J.; Turek, T. Alkaline Water Electrolysis Powered by Renewable Energy: A Review. Processes 2020, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiga, P.; Doi, N.; Wong, C.; Santosa, D.M.; Kuo, L.-J.; Gill, G.A.; Silverstein, J.A.; Avalos, N.M.; Crum, J.V.; Engelhard, M.H.; et al. The Influence of Transitional Metal Dopants on Reducing Chlorine Evolution during the Electrolysis of Raw Seawater. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Kamaroddin, M.F.; Sabli, N.; Tuan Abdullah, T.A.; Siajam, S.I.; Abdullah, L.C.; Abdul Jalil, A.; Ahmad, A. Membrane-Based Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production: A Review. Membranes 2021, 11, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bideau, D.; Mandin, P.; Benbouzid, M.; Kim, M.; Sellier, M.; Ganci, F.; Inguanta, R. Eulerian Two-Fluid Model of Alkaline Water Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production. Energies 2020, 13, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chloride (Cl−) | Sodium (Na+) | Magnesium (Mg2+) | Calcium (Ca2+) | Total Dissolved Salts TDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19,345 | 10,752 | 2710 | 1295 | 416 | 35,000 |

| Type of Electrocatalyst | References |

|---|---|

| Pt-based | [1,9,16,17,18,19,20,40,41,57,58,98] |

| Ni-based | [1,16,17,18,19,20,21,29,31,32,33,36,38,43,48,57,58,59,62,66,68,69,75,82,91,92] |

| Fe based | [1,16,18,19,20,29,44,48,49,53,55,57,58,66,81,98,101] |

| Mo based | [16,17,19,20,43,44,50,57,58,59,60,77] |

| Co based | [1,16,17,18,19,20,35,40,47,50,52,57,58,61,80,96] |

| Cr based | [9,17,32,33,57,58] |

| Ti based | [17,21,57] |

| Ru based | [9,17,18,19,58] |

| Ir, based | [17,18,20] |

| W based | [17,18,80] |

| Selenides | [1,16,17,18,19,20,40,85,90] |

| Phosphides | [1,16,17,18,19,20,53,71,72,76,80,81,87,93,94,100] |

| Carbides/C based | [1,16,17,18,19,20,36,37,42,46,47,52,65,78,79,80,84,86,90,96,97,99] |

| Nitrides | [9,16,17,18,19,20,34,41,44,60,61,65,70,77,84,90,97] |

| Reaction | Type | References |

|---|---|---|

| Main | HER | [17,29,31,32,33,36,39,41,44,49,50,51,53,54,55,56,57,59,63,64,66,67,73,77,78,81,87,95,96,98,101] |

| OER | [17,29,36,40,41,50,53,54,55,56,57,59,64,66,67,73,101] | |

| Secundary | ClER | [81] |

| COR | [98] | |

| GOR | [91] | |

| ORR | [52] | |

| HzOR | [77] | |

| UOR | [88] | |

| MOR | [90] |

| Electrocatalyst | Electrode Reaction | Overpotential, mV | Current Density, mA/cm2 | Tafel Slope, mV/Decade | Cell Voltage, V | Cell Current Density, mA/cm2 | Stability, h | Faradaic Efficiency, % | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiMoS | HER | - | 14,6 | - | 1.9 | 100 | 17.9 | [39] | |

| MNiNS, Ni/Pt–C, Ni/Ir–C | OER, HER | 197–524 | 100 | 58.8–308.2 | 1.8 | 48.3 | 12 | [41] | |

| Co-Se | OER, HER | 268–280 | 100 | 40.4–61.4 | 1.8 | 10.3 | 12 | [40] | |

| (h-MoN NPs)/BNCNTs | HER | 78 | 10 | 46 | [42] | ||||

| Ni–Mo alloys | HER | 103–900 | 44,571 | 105–158 | 86.7–100 | [43] | |||

| NiMoN@NiFeN, Ni/IrO2 | OER | 277–542 | 100–500 | 58.6–86.7 | 1.6–1.72 | 400 | 48 | [44] | |

| MXene, carbide | HER | 225 | 98 | [46] | |||||

| NiFe- OH/ Pt | 1.6 | 200 | 100 | [48] | |||||

| S-doped Ni/Fe (O)OH | HER | 300–398 | 100–500 | 1.83–1.95 | 500–1000 | [49] | |||

| Ni3S2/Co3S4 (NiCoS), (NiMoS) | OER, HER | 2.08 | 800 | 100 | 17.9 | [50] | |||

| Co/Co3O4@C | ORR | [52] | |||||||

| (CaFeOx|FePO4) oxide | OER | 710 | 10 | 10 | [53] | ||||

| FeOOH/ β-Ni–Co-OH | OER, HER | 1.57–2.02 | 20–1000 | 378 | [54] | ||||

| Ni-Fe-OH | OER, HER | 0.4–1000 | 11.9 | [55] | |||||

| PtM (Cr, Fe, Co, Ni, Mo)/Ti | OER | 172 | [57] | ||||||

| Pt–Ru–M (Cr, Fe, Co, Ni, Mo) | OER | 172 | [58] | ||||||

| NiMo/Ni, NiMoO4 | OER, HER | 1.563 | 10 | [59] | |||||

| Mo5N6 | HER | [60] | |||||||

| Ni-N3 | HER | 102–139 | 10 | 200 | 14 | [34] | |||

| NiCoN, NixP | HER | 165 | 10 | [61] | |||||

| NiCo@C | HER | 200 | 1.34 | 2.53 | 310 | 60–140 | [62] | ||

| MnO2 | OER | 1000 | 4200 | [64] | |||||

| NiFe-LDH | OER | 260 | 100 | 43.4 | 20–50 | [66] | |||

| NiFe-LDH | OER | 2.4 | 800 | 12 | 94 | [29] | |||

| MnO2-based Electrodes | OER | 47.2–100 | [67] | ||||||

| Ni(OH)2 | OER | 340–382 | 100 | 1.65 | 80 | [73] | |||

| MoNi/NF | HER, OER | 219 | 100 | 40–120 | 1000 | 100 | [77] | ||

| MFC-N,O doped C | HER | 161 | 10 | 97.5 | 76 | [78] | |||

| CoP-WP/rGO | HER | 96–208 | 10 | 36–125 | 1000 | 30 | [80] | ||

| FeCo-Ni2P, MIL-FeCoNi | HER | 201–310 | 100–1000 | 29–45 | >500 | 100 | [81] | ||

| Ni2P-FeP | HER | 89 | 10 | 1.68 | 100 | 90 | [87] | ||

| Fe-Ni(OH)2/Ni3S2 | OER | 269 | 10 | 46 | 27 | 95 | [95] | ||

| Co/GCFs | ClOR, HER | 181.8 | 10 | 10–20 | 98 | [96] | |||

| Pt-NiFe PBA | HER, OER | 29–210 | 10 | 1.46–1.48 | 12 | 100 | [98] | ||

| Graphite | 3–4.5 | 25.48–71.99 | [17] | ||||||

| Co, Ni/C | HER | [47] | |||||||

| NiCo/MXene | 0.7–1.0 | 0.7–1.0 | 500 | 140 | [35] |

| Method Type | Method Name | References |

|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Chronopotentiometry (CP) | [29,73,75] |

| Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) | [35,40,41,42,43,44,49,55,61,66,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,78,80,81] | |

| Cyclic voltammetry (CV) | [55,66,67,74,76,80,95,96] | |

| Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) | [31,32,33,41,43,46,69,71,74,77,80,95,96] | |

| Structure investigation | X-ray diffraction (XRD) | [10,16,41,43,44,67,72,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,96] |

| X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) | [41,44,66,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,80,81,87,95,96,97] | |

| Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) | [40,41,44,81] | |

| Dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (DF-STEM) | [44] | |

| Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) | [35,40,41,44,73,74,75,76,81,87,95,96,97] | |

| High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) | [40,41,44,66,73,74,75,76,81] | |

| Scanning electron micrography (SEM), | [16,35,43,44,55,66,69,71,72,73,74,76,77,78,79,87,95,96,97] | |

| Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) | [43,44,73,75,76,78,96] | |

| Raman spectroscopy | [10,52,72,78,95] | |

| X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) | [10,34] | |

| Glow discharge spectroscopy | [79] | |

| Calculation & simullation | Density functional theory (DFT) | [9,10,34,39,60,70,75,95] |

| Involved Process | Electrolyte | Energy Input | Technology | Energy Efficiency (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolysis | Water Brine seawater | Electric | AE PEM SOC | 62–82 67–84 75–90 | [13,14,15,39,110,111,113] |

| Electrophotolysis | Water seawater | Photonic Electric | Photoelectro-chemical | 0.5–12 | [13,14,15,39,110,111,113] |

| Bioelectrolysis | Biomass | Bioenergy Electric | Microbial Nitrogen fixation | 70–80 10 | [11,13,17,38,112,115] |

| Thermochemical Electrolysis | Fuels Water Metals Hydrides | Heat Electric Chemical reaction | Plasma reforming Redox reactions | 9–85 | [12,13,107,114] |

| Emergent Technology | References |

|---|---|

| Anion exchange membrane (AEM) | [14,17,73,108,115] |

| Membrane electrolyzer | [12,14,116,117] |

| Unitized regenerative technology | [14,118,119] |

| Battolyser technology | [12,14,120,121,122] |

| Type of Renewable Source | References |

|---|---|

| Solar energy | [10,24,25,39,55,63,104,109,110,118,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,131,132] |

| Wind energy | [25,63,104,116,125,126,128,130,132] |

| Geothermal energy | [25,63,105] |

| Microhydropower | [132] |

| Waves energy | [25] |

| Hybrid renewable energy | [10,25,63,105,123,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135] |

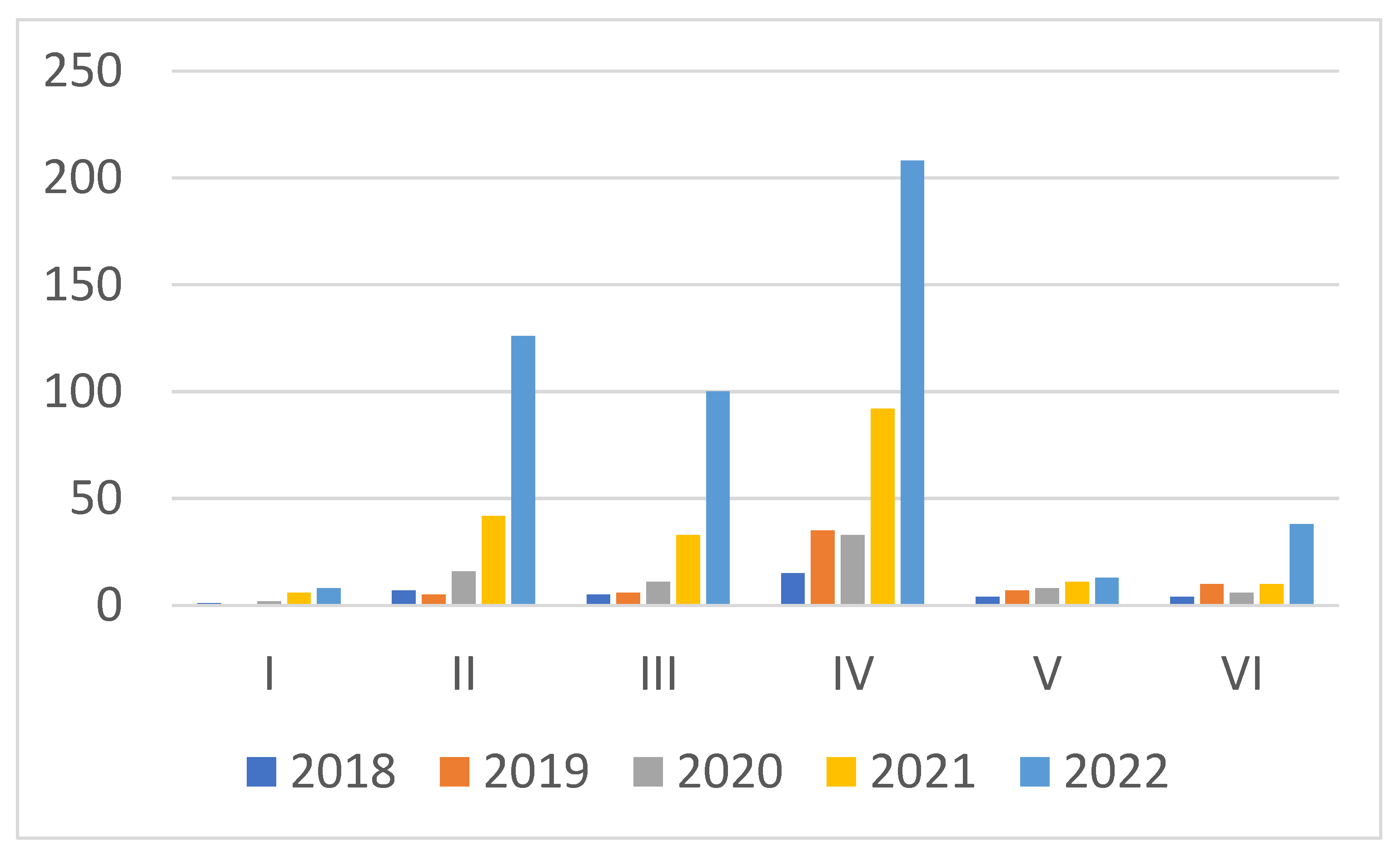

| Search No. | All the Words | Exact Phrase | Number of Found Articles 2018–2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Electrocatalyst and seawater and splitting | seawater splitting | 37 |

| II | electrocatalyst and seawater and splitting | seawater | 196 |

| III | Electrocatalyst and seawater and hydrogen and production | hydrogen production | 155 |

| IV | seawater and electrolysis and hydrogen and production | hydrogen production | 383 |

| V | seawater and electrolysis and hydrogen and production and waste | hydrogen production | 43 |

| VI | seawater and electrolysis | seawater electrolysis | 103 |

| VII | seawater and electrolysis | - | 2370 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badea, G.E.; Hora, C.; Maior, I.; Cojocaru, A.; Secui, C.; Filip, S.M.; Dan, F.C. Sustainable Hydrogen Production from Seawater Electrolysis: Through Fundamental Electrochemical Principles to the Most Recent Development. Energies 2022, 15, 8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15228560

Badea GE, Hora C, Maior I, Cojocaru A, Secui C, Filip SM, Dan FC. Sustainable Hydrogen Production from Seawater Electrolysis: Through Fundamental Electrochemical Principles to the Most Recent Development. Energies. 2022; 15(22):8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15228560

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadea, Gabriela Elena, Cristina Hora, Ioana Maior, Anca Cojocaru, Calin Secui, Sanda Monica Filip, and Florin Ciprian Dan. 2022. "Sustainable Hydrogen Production from Seawater Electrolysis: Through Fundamental Electrochemical Principles to the Most Recent Development" Energies 15, no. 22: 8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15228560

APA StyleBadea, G. E., Hora, C., Maior, I., Cojocaru, A., Secui, C., Filip, S. M., & Dan, F. C. (2022). Sustainable Hydrogen Production from Seawater Electrolysis: Through Fundamental Electrochemical Principles to the Most Recent Development. Energies, 15(22), 8560. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15228560