Study on Support Mechanisms for Renewable Energy Sources in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Policy Background and Identification of the RES Support Mechanism in Poland

2.1. Short Review of Climate and Energy Policy

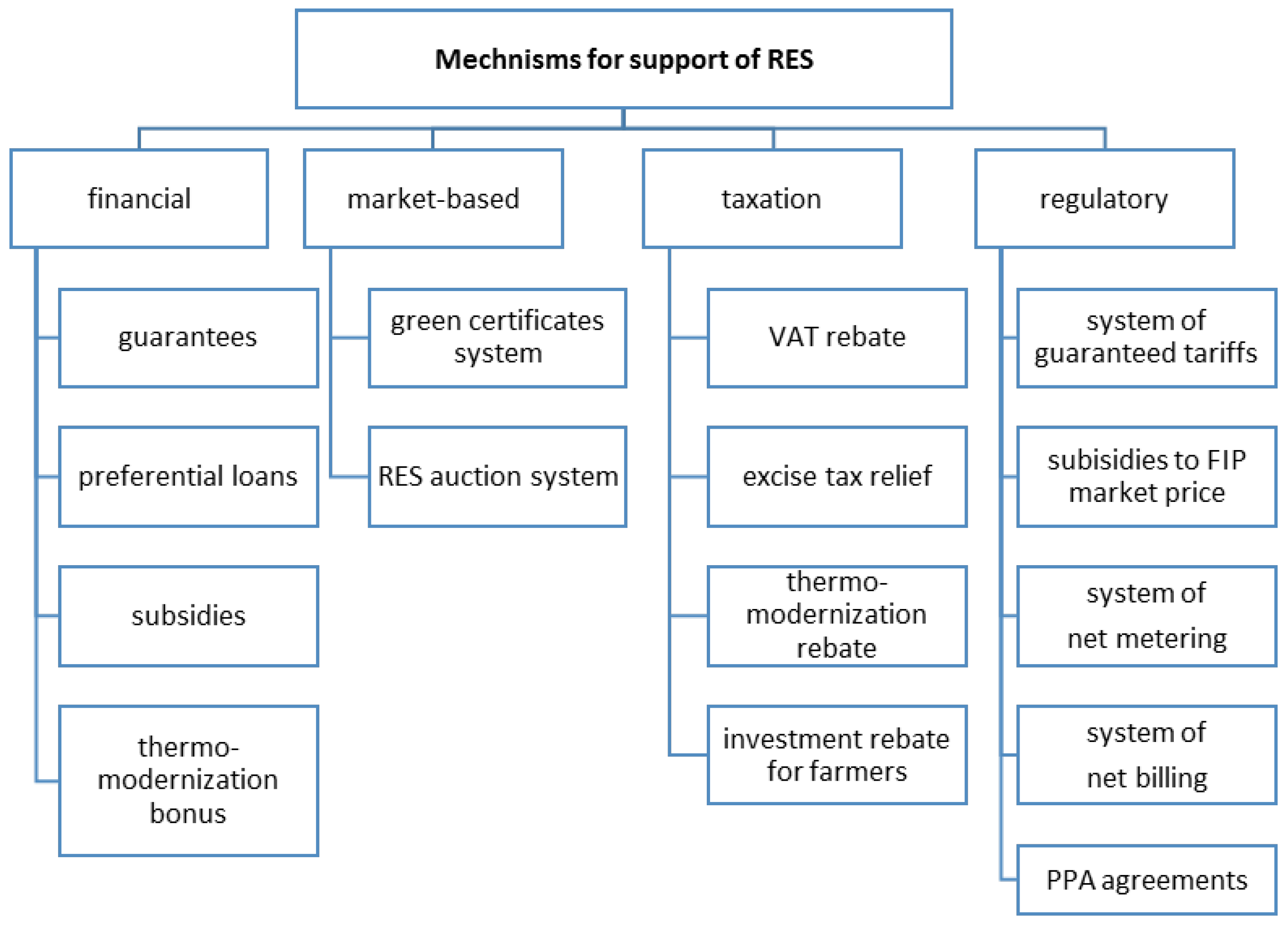

2.2. Identification of Support Mechanisms for RES in Poland

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Conceptual Background and Hypotheses Development

3.2. RES in Poland

- no more than 56% of coal in electricity generation in 2030;

- at least 23% of RES in gross final electricity energy consumption in 2030;

- implementation of nuclear energy in 2033;

- a 30% reduction in GHGo emissions by 2030 (compared to 1990);

- a 23% reduction in primary energy consumption by 2030 (compared to PRIMES projections from 2007).

3.3. Factors Determining the Production of Electricity Using RES

3.4. Forecasting the Structure of Energy Production from RES in Poland

3.5. Test Procedure

- Yt—dependent variable,

- Xt1, Xt2, …, Xtk—explanatory variables,

- εt—random component.

- —smoothed values over period t, α—smoothing constant (.

- Ct—smoothed value of the increase in trend value assessments in period t,

- α, β—smoothing constants (.

- dt—assessment of the seasonality index in period t,

- m—number of phases in the cycle,

- α, β, γ—smoothing constants (

4. Results

4.1. Trends in Energy Use in Poland

4.2. Modeling/Forecasting

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Poland, as a country with an electricity production sector based on coal and imported gas, must make significant efforts to decarbonize its economy;

- Significant volatility of Polish regulations related to the promotion of RES increases uncertainty for producers, prosumers and RES investors;

- In Poland, many instruments supporting RES are used, with some being phased out and new ones being introduced, which makes the support system opaque and inconsistent, and also results in difficulties in assessing the effectiveness and efficiency of individual instruments;

- The volume of Polish energy production from RES and the amount of capacity installed in Poland will increase (with the exception of hydropower), but to a level inadequate to ensure the implementation of climate policy goals;

- The conducted prediction indicates that the rich and diversified set of currently used RES support instruments will not ensure the fulfilment of the requirements of RES share in energy production and the expected reduction in GHG emissions, NO2 and NOx or dust.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Zhou, B. Red Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 14 September 2019).

- UN Climate Change Conference. (COP26) at the SEC—Glasgow 2021, UN Climate Change Conference at the SEC—Glasgow. 2021. Available online: https://ukcop26.org/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- COP 21|UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/conferences/past-conferences/paris-climate-change-conference-november-2015/cop-21 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Nestle, I. Evaluation of Risk in Cost-Benefit Analysis of Climate Change. In Economics and Management of Climate Change; Hansju, B., Antes, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 23–35. Available online: https://link-1springer-1com-10fzxbuki00d5.han.uek.krakow.pl/chapter/10.1007/978-0-387-77353-7_3, (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- KLIMADA. Przyszłe Zmiany Klimatu, Scenariusze Klimatyczne Polski w XXI Wieku. Available online: http://klimada.mos.gov.pl/zmiany-klimatu-w-polsce/przyszle-zmiany-klimatu/ (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- State and Trends in Adaptation 2020. Global Center Adaptation. 2020. Available online: https://gca.org/reports/state-and-trends-in-adaptation-report-2020/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- FPFIS. Economic Analysis of Selected Climate Impacts, EU Science Hub—European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/economic-analysis-selected-climate-impacts (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Ziervogel, G.; New, M.; van Garderen, E.A.; Midgley, G.; Taylor, A.; Hamann, R.; Stuart-Hill, S.; Myers, J.; Warburton, M. Climate change impacts and adaptation in South Africa. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmuth, M.E. Climate Risk Management in Africa: Learning from Practice; International Research Institute for Climate and Society: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Rakshit, S.; Nag, A.; Ray, M.; Kharbikar, H.L.; Shubha, K.; Sarkar, S.; Paul, S.; Roy, S.; Maity, A.; et al. Climate Change Risk Perception, Adaptation and Mitigation Strategy: An Extension Outlook in Mountain Himalaya. In Conservation Agriculture; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 257–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, M.J. Banks, climate risk and financial stability. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2019, 27, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plac, K. Climate as an area of strategic intervention in urban development. Bibl. Reg. 2020, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak, A.; Europejska Agencja Środowiska. Urban Adaptation in Europe: How Cities and Towns Respond to Climate Change; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2800/324620 (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Dickson, E.; Baker, J.L.; Hoornweg, D.; Asmita, T. Urban Risk Assessments: An Approach for Understanding Disaster and Climate Risk in Cities; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Urban Adaptation in Europe: How Cities and Towns Respond to Climate Change. Publication. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/urban-adaptation-in-europe (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Sokołowski, M.M. Artificial intelligence and climate-energy policies of the EU and Japan. In Regulating Artificial Intelligence in Industry; Bielicki, D., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. Council Resolution of 21 June 1989 on the Greenhouse Effect and the Community (89/C 183/03); Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 1989.

- Draft Council Resolution on the Greenhouse Effect and the Community Com 1998/656 Final. 1988. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/ALL/?uri=CELEX:51988PC0656&qid=1643809398380, (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Boasson, E.L.; Wettestad, J. EU Climate Policy: Industry, Policy Interaction and External Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Climate Change Programme. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-action/european-climate-change-programme_pl (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Climate & Energy Package. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2020-climate-energy-package_en (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Wojtkowska-Łodej, G.; Nyga-Łukaszewska, H. Convergence or divergence of the European Union’s energy strategy in the Central European countries? CES Work. Pap. 2019, 11, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPE 2020 A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. COM(2010) 2020 Final. 2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/AUTO/?uri=CELEX:52010DC2020&qid=1643832215833&rid=1 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- European Environment Agency. Trends and Projections in Europe 2016—Tracking Progress Towards Europe’s Climate and Energy Targets, EEA Raport 29; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016.

- Kryk, B.; Guzowska, M. Implementation of Climate/Energy Targets of the Europe 2020 Strategy by the EU Member States. Energies 2021, 14, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/european-statistical-system/legislation-in-force (accessed on 16 February 2017).

- Q&A: How ‘Fit for 55’ Reforms Will Help EU Meet Its Climate Goals. Carbon Brief. 29 July 2021. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/qa-how-fit-for-55-reforms-will-help-eu-meet-its-climate-goals (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992. United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Kyoto Protocol—Targets for the First Commitment Period|UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-kyoto-protocol/what-is-the-kyoto-protocol/kyoto-protocol-targets-for-the-first-commitment-period (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- COP 24|UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/conferences/past-conferences/katowice-climate-change-conference-december-2018/sessions-of-negotiating-bodies/cop-24 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Malec, M. The prospects for decarbonisation in the context of reported resources and energy policy goals: The case of Poland. Energy Policy 2021, 161, 112763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowski, W.M. Target for national carbon intensity of energy by 2050: A case study of Poland’s energy system. Energy 2012, 46, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzikuć, M.; Gorączkowska, J.; Piwowar, A.; Dzikuć, M.; Smoleński, R.; Kułyk, P. The analysis of the innovative potential of the energy sector and low-carbon development: A case study for Poland. Energy Strat. Rev. 2021, 38, 100769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ney, R. Niektóre uwarunkowania polskiej polityki energetycznej. Polityka Energetyczna 2009, 12, 5–17. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-article-BPB7-0019-0006 (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Ustawa z Dnia 24 Lutego 1990 r. O Likwidacji Wspólnoty Węgla Kamiennego i Wspólnoty Energetyki i Węgla Brunatnego 1990. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19900140089 (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Ustawa z Dnia 10 Kwietnia 1997 r.—Prawo Energetyczne. 1997. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19970540348 (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Wohlgemuth, N.; Wojtkowska-Łodej, G. Policies for the promotion of renewable energy in Poland. Appl. Energy 2003, 76, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiek, K. Kształtowanie rynku energii w Polsce. Zesz. Nauk. Akad. Ekon. Krakowie 2005, 668, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gabryś, H.L. Jak zmieniała się energetyka w Polsce w ciągu ostatnich dwudziestu kilku lat? (Niekoniecznie obiektywny, ale za to nieco emocjonalny osąd współkreatora i uczestnika tych zmian). Energetyka 2014, 7, 377–381. Available online: https://www.cire.pl/pliki/2/jakzmienialasieenergetykawpolscewciaguostatnichdwudziestukilkulat.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2030 Roku. Ministerstwo Gospodarki. 2009. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/aktywa-panstwowe/polityka-energetyczna-polski-do-2030-roku (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040 r.—Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/polityka-energetyczna-polski (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Wnioski z Analiz Prognostycznych na Potrzeby Polityki Energetycznej Polski Do 2050 Roku—Załącznik 2. Do Polityki Energetycznej Polski Do 2050 Roku; Ministerstwo Gospodarki: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. Available online: https://bip.mos.gov.pl/fileadmin/user_upload/bip/strategie_plany_programy/Polityka_energetyczna_Polski/zal._2_do_PEP2040_-_Wnioski_z_analiz_prognostycznych_2021-02-02.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Krajowy Plan na Rzecz Energii i Klimatu na Lata 2021–2030: Cele i Zadania Oraz Polityki i Działania, Ministerstwo Energii RP. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/poland_draftnecp_en.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Gurgul, H.; Lach, Ł. The electricity consumption versus economic growth of the Polish economy. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bildirici, M.E.; Kayıkcı, F.; Kayikçi, F. Economic Growth and Electricity Consumption in Emerging Countries of Europa: An ARDL Analysis. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2012, 25, 538–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bayar, Y.; Özel, H.A. Electricity Consumption and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies. J. Knowl. Manag. Econ. Inf. Technol. 2014, 4, 1–18. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/spp/jkmeit/1453.html (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Khobai, H. Electricity Consumption and Economic Growth: A Panel Data Approach to BRICS Countries; Department of Economics, Nelson Mandela University: Gqeberha, South Africa, 2017; Volume 1707, Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/mnd/wpaper/1707.html (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Engel, H.; Purta, M.; Speelman, E.; Szarek, G.; van der Pluijm, P. Neutralna Emisyjnie Polska 2050; McKinsey: Charlotte, NA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/pl/our-insights/carbon-neutral-poland-2050 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Mazurek-Czarnecka, A. Solar Energy is an Important Trend in the Development of the Energy Sector in Poland; Cordoba, Spain, 2021; pp. 4515–4522. Available online: https://ibima.org/accepted-paper/solar-energy-is-an-important-trend-in-the-development-of-the-energy-sector-in-poland/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Mielczarski, W. Odnawialne Źródła Energii jako element Nowego Zielonego Ładu. ACADEMIA-Mag. Pol. Akad. Nauk. 2021, 1, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska, K.; Ancygier, A.; Solorio, I.; Jörgens, H. Poland at the renewable energy policy crossroads: An incongruent Europeanization? In A Guide to EU Renewable Energy Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjærseth, J.B. Implementing EU climate and energy policies in Poland: Policy feedback and reform. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlik, L.; Mokrzycki, E. Changes in the Structure of Electricity Generation in Poland in View of the EU Climate Package. Energies 2019, 12, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar, A. Agricultural Biogas—An Important Element in the Circular and Low-Carbon Development in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnatowska, R.; Moryń-Kucharczyk, E. The Place of Photovoltaics in Poland’s Energy Mix. Energies 2021, 14, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnatowska, R.; Moryń-Kucharczyk, E. Current status of wind energy policy in Poland. Renew. Energy 2018, 135, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M.; Saki, S. Forecasting the Structure of Energy Production from Renewable Energy Sources and Biofuels in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziembicki, P.; Kozioł, J.; Bernasiński, J.; Nowogoński, I. Innovative System for Heat Recovery and Combustion Gas Cleaning. Energies 2019, 12, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igliński, B.; Iglińska, A.; Koziński, G.; Skrzatek, M.; Buczkowski, R. Wind energy in Poland—History, current state, surveys, Renewable Energy Sources Act, SWOT analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechota, G.; Igliński, B. Biomethane in Poland—Current Status, Potential, Perspective and Development. Energies 2021, 14, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, M.B.; Igliński, B.; Kujawski, W.; Iwański, P. Energy Transition in Poland—Assessment of the Renewable Energy Sector. Energies 2021, 14, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paska, J.; Sałek, M.; Surma, T. Current status and perspectives of renewable energy sources in Poland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Grobelski, T.; Harembski, M. Is energy policy a public issue? Nuclear power in Poland and implications for energy transitions in Central and East Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, B.; Staliński, A.; Trąpczyński, P. Public policy support and the competitiveness of the renewable energy sector—The case of Poland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanés-Montero, P.; Arroyo-Farrona, A.; Pérez-Calderón, E. Assessment of the Influence of Feed-In Tariffs on the Profitability of European Photovoltaic Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alolo, M.; Azevedo, A.; El Kalak, I. The effect of the feed-in-system policy on renewable energy investments: Evidence from the EU countries. Energy Econ. 2020, 92, 104998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Renewable Energies in the Middle East and North Africa: Policies to Support Private Investment; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/renewable-energies-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa_9789264183704-en (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Pożyczka na Produkcję i Dystrybucję Energii ze Źródeł Odnawialnych. BGK. Available online: https://www.bgk.pl/podmioty-rynku-mieszkaniowego/efektywnosc-energetyczna-i-oze/pozyczka-na-produkcje-i-dystrybucje-energii-ze-zrodel-odnawialnych-z-projektu-inwestycje-innowacje-energetyka-dla-wojewodztwa-dolnoslaskiego/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Mój Prąd. Available online: https://mojprad.gov.pl/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- GLOBEnergia. Znamy Budżet Programu Mój Prąd 4.0—Nowy Nabór Ruszy w I Kwartale 2022 Roku. Available online: https://globenergia.pl/znamy-budzet-programu-moj-prad-4-0-nowy-nabor-ruszy-w-i-kwartale-2022-roku/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Dyduch, J.; Rosiek, K. Analiza wpływów i wydatków funduszy ekologicznych w latach 1997-2008. In Ocena Funduszy Ekologicznych w Świetle Ich Dalszego Funkcjonowania w Polsce; Górka, K., Małecki, P.P., Eds.; Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2011; pp. 59–118. [Google Scholar]

- Górka, K.; Rosiek, K. Zmiany roli funduszy ochrony środowiska i gospodarki wodnej w finansowaniu polityki ekologicznej w Polsce. Zesz. Nauk. Akad. Ekon. Krakowie 2007, 732, 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, G.D.; Zylicz, T. The role of Polish environmental funds: Too generous or too restrictive? Environ. Dev. Econ. 1999, 4, 413–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecki, P.P. The Role of Ecological Fees in the Functioning of Polish Environmental Protection and Water Management Funds. Econ. Environ. Stud. 2010, 1, 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Dofinansowanie w Nowej Wersji Programu Energia Plus. gramwzielone.pl. Available online: https://www.gramwzielone.pl/trendy/103903/dofinansowanie-w-nowej-wersji-programu-energia-plus (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Energia Plus. WFOSiGW. Available online: http://wfosigw.olsztyn.pl/srodki-unijne/doradztwo-energetyczne-old/energia-plus/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Dotacje OZE—Jakie Dofinansowanie w 2022? Enerad.pl. Available online: https://enerad.pl/aktualnosci/dotacje-oze/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Premia Termomodernizacyjna z Funduszu Termomodernizacji i Remontów. BGK. Available online: https://www.bgk.pl/male-i-srednie-przedsiebiorstwa/modernizacja-i-rewitalizacja/premia-termomodernizacyjna-z-funduszu-termomodernizacji-i-remontow/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Program Priorytetowy «AGROENERGIA»”, WFOŚiGW Poznań. Available online: https://www.wfosgw.poznan.pl/programy/program-priorytetowy-agroenergia/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Dz. U. z 2018 r. poz. 2389, Ustawa z Dnia 20 Lutego 2015 r. O Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20150000478 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Urząd Regulacji Energetyki. System Aukcyjny dla Odnawialnych Źródeł energii ma 5 lat. Urząd Regulacji Energetyki. Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/pl/urzad/informacje-ogolne/aktualnosci/8739,System-aukcyjny-dla-odnawialnych-zrodel-energii-ma-5-lat.html (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Dz.U. 2018 poz. 2525, Rozporządzenie Ministra Finansów z Dnia 28 Grudnia 2018 r. w Sprawie Zwolnień od Podatku Akcyzowego. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180002525, (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- IPPP1/4512-702/15-2/AW—Pismo Wydane Przez: Izba Skarbowa w Warszawie—OpenLEX. Available online: https://sip.lex.pl/orzeczenia-i-pisma-urzedowe/pisma-urzedowe/ippp1-4512-702-15-2-aw-pismo-wydane-przez-izba-skarbowa-w-184828489 (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Dz.U. 2018 poz. 1276, Ustawa z Dnia 7 Czerwca 2018 r. O Zmianie Ustawy o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180001276, (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Soliński, B. Support mechanisms for the promotion renewable energy sources—Feed in Tariff and Tradable Green Certifi-cates comparison. Energy Policy J. 2008, 11, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Urząd Regulacji Energetyki. Podstawowe Informacje i Wzory. Urząd Regulacji Energetyki. Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/pl/oze/systemy-fitfip/7634,Podstawowe-informacje-i-wzory.html (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Zmiany w Systemie Opustów Prosumentów ma Zachęcić do Inwestycji w Magazyny Energii. Serwis Informacyjny Cire 24. Available online: https://www.cire.pl/artykuly/serwis-informacyjny-cire-24/sejm-komisja-chce-aby-system-opustow-dla-prosumentow-obowiazywal-do-31-marca-2022-r (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- System Opustów dla Prosumentów do 31 Marca 2022 r. wnp.pl. Available online: https://www.wnp.pl/energetyka/system-opustow-dla-prosumentow-do-31-marca-2022-r,502462.html (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Umowy PPA w Polsce. Co Warto o Nich Wiedzieć? GRAMwZIELONE.pl. Available online: https://gramwzielone.pl/umowy-ppa-w-polsce-co-warto-o-nich-wiedziec (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Skorupka, M.J.; Mikłaszewicz, B. Umowa PPA (Power Purchase Agreement) w Polsce”, KBPP, 10 Czerwiec 2021. Available online: https://kbpp.pl/pl/aktualnosci/umowa-ppa-power-purchase-agreement-w-polsce/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Levy, A. From Hotelling to Backstop Technology. Faculty of Business—Economics Working Papers. 2000. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/commwkpapers/25 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Hotelling, H. The Economics of Exhaustible Resources. J. Political Econ. 1931, 39, 137–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, S.; Fisher, A.C. Hotelling’s «Economics of Exhaustible Resources»: Fifty Years Later. J. Econ. Lit. 1981, 19, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C.; Salant, S. On Hotelling, Emissions Leakage, and Climate Policy Alternative. Resour. Future Discuss. Pap. 2010, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Graczyk, A.M. Gospodarowanie Odnawialnymi Zródłami Energii w Ekonomii Rozwoju Zrównoważonego: Teoria i Praktyka; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tahvonen, O. Fossil Fuels, Stock Externalities, and Backstop Technology. Can. J. Econ. 1997, 30, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.C. Resource and Environmental Economics; CUP Archive: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska, K. Poland’s Clash Over Energy and Climate Policy: Green Economy or Grey Status Quo? In The European Union in International Climate Change Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- PS. Energochłonność Pierwotna PKB z Korektą Klimatyczną (SDG_7.1A). Available online: https://sdg.gov.pl/ (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Eurostat. Energy Productivity (SDG_07_30). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_07_30/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- PS. Zasady Metodyczne Sprawozdawczości Statystycznej z Zakresu Gospodarki Paliwami i Energią Oraz Definicje Stosowanych Pojęć. 2006. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/energia/zasady-metodyczne-sprawozdawczosci-statystycznej-z-zakresu-gospodarki-paliwami-i-energia-oraz-definicje-stosowanych-pojec,7,1.html (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- URE. Informacja nr 44/2016 Informacja Prezesa Urzędu Regulacji Energetyki w Sprawie Stosowania Pojęcia Mocy Zainstalowanej Elektrycznej; URE: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Aktywów Państwowych RP. Transformacja Sektora Elektroenergetycznego w Polsce. Wydzielenie Wytwórczych Aktywów Węglowych ze Spółek z Udziałem Skarbu Państwa. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/aktywa-panstwowe/program-transformacji-sektora-elektroenergetycznego (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources and Amending and Subsequently Repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC; Dz.U. L 140 z 5.6.2009, str. 16—62. 2009. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/28/oj/eng, (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Text with EEA Relevance.), t. 328. 2018. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/2001/oj/eng, (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- PS. Ekonomiczne Aspekty Ochrony Środowiska 2020/Economic Aspects of Environmental Protection 2020. stat.gov.pl. 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ekonomiczne-aspekty-ochrony-srodowiska-2019,14,1.html (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- PS. Energia ze Źródeł Odnawialnych w 2019 Roku/Energy from Renewable Resources 2019. 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/energia/energia-ze-zrodel-odnawialnych-w-2020-roku,10,4.html (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Dz.U. 2016 poz. 961, Ustawa z Dnia 20 Maja 2016 r. O Inwestycjach w Zakresie Elektrowni Wiatrowych. 2016. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20160000961 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Księżopolski, K.; Maśloch, G. Time Delay Approach to Renewable Energy in the Visegrad Group. Energies 2021, 14, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfreda, A.; Ravazzolo, F.; Rossini, L. Comparing the forecasting performances of linear models for electricity prices with high RES penetration. Int. J. Forecast. 2020, 36, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, C.; Pinson, P.; Bessa, R.J. Towards Data Markets in Renewable Energy Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 12, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.; Bessa, R.J.; Browell, J.; Pinson, P. The future of forecasting for renewable energy. WIREs Energy Environ. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M. Analyzing Similarities between the European Union Countries in Terms of the Structure and Volume of Energy Production from Renewable Energy Sources. Energies 2020, 13, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xu, G.; Cai, P.; Tian, L.; Huang, Q. Development forecast of renewable energy power generation in China and its influence on the GHG control strategy of the country. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celiktas, M.S.; Kocar, G. From potential forecast to foresight of Turkey’s renewable energy with Delphi approach. Energy 2010, 35, 1973–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daim, T.; Harell, G.; Hogaboam, L. Forecasting renewable energy production in the US. Foresight 2012, 14, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirosław, P. Prognozowanie ultrakrótkoterminowe mocy generowanej w odnawialnych źródłach energii z wykorzystaniem logiki rozmytej. Przegląd Elektrotech. 2014, 90, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Liu, R. Ultra-short-term wind power prediction using ANN ensemble based on PCA. In Proceedings of the 7th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, Harbin, China, 2–5 June 2012; Volume 3, pp. 2108–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Yong, C.; Feng, X.; Chuanzhi, X.; Xiaofang, S.; Dongkuo, S.; Maosheng, D.; Jun, Z.; Li, X.; Jiafeng, S.; et al. Ultra-short-term wind power prediction and its application in early-warning system of power systems security and stability. In Proceedings of the 2011 4th International Conference on Electric Utility Deregulation and Restructuring and Power Technologies (DRPT), Weihai, China, 6–9 July 2011; pp. 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.; Negnevitsky, M. Very Short-Term Wind Forecasting for Tasmanian Power Generation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2006, 21, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Savkin, A.V. A Method for Short-Term Wind Power Prediction with Multiple Observation Points. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2012, 27, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, P. Analiza statystyczna danych do prognozowania ultrakrótkoterminowego produkcji energii elektrycznej w systemach fotowoltaicznych. Przeglad Elektrotech. 2014, 90, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczyński, D.; Piotrowski, P. Prognozowanie Dobowej Produkcji Energii Elektrycznej Przez Turbinę Wiatrową z Horyzontem 1 Doby”, Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, nr R. 90, nr 9, s. 113–117. 2014. Available online: http://pe.org.pl/articles/2014/9/31.pdf, (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Zielińska-Sitkiewicz, M.; Chrzanowska, M.; Furmańczyk, K.; Paczutkowski, K. Analysis of Electricity Consumption in Poland Using Prediction Models and Neural Networks. Energies 2021, 14, 6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUCALC. European-Calculator. Available online: https://www.european-calculator.eu/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Jónsson, T.; Pinson, P.; Nielsen, H.A.; Madsen, H. Exponential Smoothing Approaches for Prediction in Real-Time Electricity Markets. Energies 2014, 7, 3710–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Puig, V.; Quevedo, J. Prognosis of Water Quality Sensors Using Advanced Data Analytics: Application to the Barcelona Drinking Water Network. Sensors 2020, 20, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.-J.; Li, L. Application Study of Comprehensive Forecasting Model Based on Entropy Weighting Method on Trend of PM2.5 Concentration in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 7085–7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobet, A.; Escobet, T.; Quevedo, J.; Molina, A. Sensor-Data-Driven Prognosis Approach of Liquefied Natural Gas Satellite Plant. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2020, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.; Selvarasan, I.; Begum A, J. Short-Term Forecasting of Total Energy Consumption for India-A Black Box Based Approach. Energies 2018, 11, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.W. Triple seasonal methods for short-term electricity demand forecasting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 204, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Ahmar, A.S. Forecasting of primary energy consumption data in the United States: A comparison between ARIMA and Holter-Winters models. AIP Conf. Proc 2017, 1885, 020163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trull, O.; García-Díaz, J.C.; Troncoso, A. Application of Discrete-Interval Moving Seasonalities to Spanish Electricity Demand Forecasting during Easter. Energies 2019, 12, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño, M.D.; Arango, A.; Lotero, L.; Jimenez, M. Modelos de series temporales para pronóstico de la demanda eléctrica del sector de explotación de minas y canteras en Colombia. Rev. EIA 2021, 18, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, G.P.; Dikaiakos, C.; Dramountanis, A.; Papaioannou, P.G. Analysis and Modeling for Short- to Medium-Term Load Forecasting Using a Hybrid Manifold Learning Principal Component Model and Comparison with Classical Statistical Models (SARIMAX, Exponential Smoothing) and Artificial Intelligence Models (ANN, SVM): The Case of Greek Electricity Market. Energies 2016, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Bao, Y. Equipping Seasonal Exponential Smoothing Models with Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Electricity Consumption Forecasting. Energies 2021, 14, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, M.; Yumusak, N. Year Ahead Demand Forecast of City Natural Gas Using Seasonal Time Series Methods. Energies 2016, 9, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of 18 June 2020 on the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment, and Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088, t. 198. 2020. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/852/oj/eng (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Klimat Polski 2020; IMGW-PIB: Warszawa, Poland, 2021.

- Importujemy Coraz Więcej Prądu i… Ratujemy Sąsiadów Eksportem—WysokieNapiecie.pl. Available online: https://wysokienapiecie.pl/35185-importujemy-coraz-wiecej-pradu-ratujemy-sasiadow-eksportem/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Chaurasiya, P.K.; Kumar, V.K.; Warudkar, V.; Ahmed, S. Evaluation of wind energy potential and estimation of wind turbine characteristics for two different sites. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2021, 42, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasiya, P.K.; Rajak, U.; Singh, S.K.; Verma, T.N.; Sharma, V.K.; Kumar, A.; Shende, V. A review of techniques for increasing the productivity of passive solar stills. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date, Place and Name of the Event | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| The period before 1992 | Extensive debates supporting symbolic policy building towards a consensus, which creates foundations for the concept of sustainable development. |

| The period from 1998–2004 | A new direction of development with the shift into carbon pricing, resulting from attitude changes in Germany and Great Britain [20]. Emphasis placed on revising existing policies. The first European Climate Change Program (ECCP) is announced. Three out of 11 ECCP working groups are dedicated directly to energy issues: energy supply, energy demand and energy efficiency in end-use equipment and industrial processes [21]. |

| The period from 2005–2010 | In 2004, the European Environmental Agency points out that the GHE reduction targets are not achievable [21]. As a result, 2005 sees the launch of Phase 1 of the implementation of the EU Emissions Trading System. However, it is only the 2007 proposal of the 20-20-20 by 20 package and its adaptation in 2009 that sets the true boundaries and direction of change [22], especially for the countries of Central and Eastern Europe [23]. Ultimately, by 2010 the direction of climate policy development metamorphoses “from pieces to package” [18], and at the same time the integration of climate and energy policy objectives takes place. |

| The period 2010–2020 | The Europe 2020 strategy sets goals in terms of decarbonizing the economy, increasing the share of RES and supporting the growth of energy efficiency [24]. There is also focus on the development of monitoring strategy implementation progress and by 2016, it is anticipated that there is a real chance of achieving them [25]. Detailed studies and analyses indicate that the targets are not being achieved evenly both between them (with the least progress being made in energy efficiency) and between countries [26]. New energy targets are set: at least 40% cuts in greenhouse gas emissions (from 1990 levels), at least 32% share for RES and at least 32.5% improvement in energy efficiency [27]. |

| The period 2020 to now | The EU publishes its Green Deal, a new strategy for growth. Its aim is to build a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy that will have reached net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and that economic growth will include the optimal use of natural resources [27]. |

| The Fit for 55 package is the largest EU initiative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, with a total of 13 legislative proposals. The proposed legislation includes a new EU forest strategy, a CO2 charging mechanism at the borders (CBAM), a social instrument for climate action and two transport initiatives focused on the deployment of sustainable aviation fuels, ReFuelEU Aviation, and on sustainability of the European maritime space, FuelEU Maritime. Amendments are to be enacted to the EU CO2 Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the Land and Forest Land Use Regulation (LULUCF), the Renewable Energy Directive (RED), the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) and the Regulation setting CO2 emission standards. These policies are also to be adapted to a more ambitious climate target for passenger cars. The Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Directive (AFID) and the Energy Taxation Directive will be revised [28]. |

| Date, Place and Name of the Event | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Earth Summit Rio de Janerio (1992) | Setting the fundamental principles in socio-economic policy, which require that environmental protection be taken into account. Ends with the adoption of documents: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Agenda 21, Convention on the Conservation of Biological Diversity and Declaration on the direction of development, protection and use of forests [29]. |

| Kyoto Protocol (1997) | Defining binding greenhouse gas reduction targets, to be achieved through three market mechanisms: a carbon market between countries (emission trading—ET), the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and the Joint Implementation Mechanism (JI) [30]. |

| 2015 conference in Paris—COP21 | The landmark climate summit, ending with an agreement that every five years starting from 2020, each country should present new, ever higher climate goals and prepare adaptation plans, which are implemented at the national level. Another agreed objective was to redirect investments towards low-carbon development [4]. |

| 2018 climate summit in Katowice—COP24 | Refinement of the framework targets agreed in Paris. However, several of them remain unresolved: the global emissions trading system, length of commitment periods and forms for emission reporting [31]. |

| 2021 climate summit in Glasgow- COP26 | The climate summit sets targets for five areas: electromobility, hydrogen, clean energy, steel and agriculture. The rules for the functioning of the global emissions trading system are clarified. Forms for emission reporting are agreed in order to verify whether the emission reduction targets in individual countries are actually being met as planned. A major decision, adopted unanimously, concerns the development and distribution of clean technologies, while gradually eliminating coal capacity and phasing out fossil fuel subsidies [3]. Countries are required to present new, higher reduction targets for 2030. Among the many declarations, there are also those that concern the reduction in methane emissions, the reduction in deforestation, as well as the financial alliance for the goals of Net Zero [31]. |

| Mechanism | Instrument | Characteristics | Beneficiary of Support | Amount of Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial mechanisms | Preferential loans | Preferential loans are loans granted for the implementation of projects in the area of installations generating energy from RES | The financing is intended for: organizational units of local government units, public finance sector units—other than those listed above | Preferential interest rates ranging from 0.25% to 0.5% per annum. |

| My Electricity Program | Grants from the “My Electricity” program are supported to increase the production of electricity from photovoltaic micro-installations (micro-PV). Beneficiaries receive reimbursement of costs incurred for the purchase and installation of a PV | This type of support may be granted to persons who generate electricity solely for their own needs and have a contract with the distribution system operator, which regulates issues related to the introduction into the grid of photovoltaic energy produced in micro-PV. | In the first two editions, the support amounted to PLN 5000. In subsequent editions, the support amounted to PLN 3000. | |

| Clean Air Program | The program grants non-refundable grants or subsidies intended for the repayment of part of the bank loan for the purchase and installation of a PV | As part of the program, natural persons who own a residential building can apply for funding for the replacement of old furnaces and boilers for solid fuel. | The amount of support ranges from 15–90% of the eligible investment costs and depends on the family’s income. | |

| Thermo-modernization bonus | The thermo-modernization bonus is an instrument granted by BGK. Its main purpose is to reimburse the costs incurred for the thermal modernization of buildings. The bonus can only be used if you take out a loan to complete the investment. | The thermo-modernization bonus can be used by: - owners of single-family houses, - legal persons (housing cooperatives and commercial law companies), - local government units, - housing communities | The premium may amount to up to 21% of the costs of the thermo-modernization project, provided that it also provides for the installation of micro-installations of RES. | |

| Energy Plus Program | Energy Plus is a program implemented by the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management, its aim is to reduce the negative impact of enterprises on the environment and improve air quality. | Support under the program may be granted to entrepreneurs performing business activity | Support provided up to 50% of the eligible costs in the case of a grant or up to 85% of the eligible costs in the case of a preferential loan. If support is used in the form of a preferential loan, it is possible to partially redeem it up to 10% | |

| Biznesmax Guarantee | The Biznesmax guarantee is a bank guarantee program granted by BGK and consists in free securing a loan for investments in ecological innovations, including PV. | Support in this form can be used by small and medium-sized enterprises that want to install PV at home. | The support is offered for a period of 20 years with a guarantee range of up to 80% of the loan with a maximum amount of up to EUR 2.5 million. The support provided by the bank also includes an interest rate subsidy | |

| Agroenergy | The aim of this program is to increase the energy production from RES in the agricultural sector. Financial support covers projects involving the purchase and installation of PV | Support under this scheme is open to private persons and legal persons who own or lease agricultural property and whose total agricultural area ranges from 1 ha to 300 ha and who have run an agricultural holding for at least one year before submitting the application. | Aid in the form of grants up to 13% (for installations from 30 < kW ≤ 50) or up to 20% (for installations from 10 < kW ≤ 30) of the eligible investment costs | |

| Market mechanisms | Tradable green certificates system | Under this system, producers of RES are granted a certificate for each unit of energy they produce. This certificate is transferable and tradeable on the market | Power generators. The certificate of origin is granted only to electricity generated in a given RES installation for the first time before the date of entry into force of Chapter Four of the RES Act, i.e., before 1 July 2016 | The energy producer receives income from the physical sale of the produced energy, the price of which is set on the electricity market and additionally on the market of transferable certificates of origin of energy, i.e., certificates, specially designated for this purpose. |

| RES auction system | The RES auction is announced and carried out by the President of the Energy Regulatory Office (ERO) using the Internet Platform The first auction took place on 30 December 2016. Within a given basket of energy producers, the auction is won by those entities that offer the lowest price for the sale of energy | Power producers | The electricity production receives support in the form of a surcharge when the amount of the subsidy, depending on the outcome of the auction, is lower than the sale price (the average daily price of energy on the Polish Power Exchange (PPE). If the price of energy is higher, the producer is obliged to transfer the surplus. Auction winners receive a guarantee of a steady income from each MWh generated for the next 15 years | |

| Tax mechanisms | VAT relief | These are tax exemptions from activities related to the production of RES, which may relate to exemption from turnover, income, agricultural tax, as well as VAT and excise duty | Owners (investors) of houses with a usable area not exceeding 300 m2, apartments with a usable area of up to 150 m2, as well as objects covered by the social housing program | Reduction in the VAT rate from 23% to 8% |

| Excise tax relief | Owners of PV and consuming the electricity produced | Exemption from excise duty on the consumption of electricity produced from generators with a total capacity not exceeding 1 MW by entities that consume the energy produced | ||

| Thermo-modernization relief | Owners or co-owners of single-family residential buildings who carry out in their home investments of a thermo-modernization nature, including the installation of a PV, solar collectors and a heat pump | As part of which for a period of up to six consecutive years you can deduct a total of PLN 53,000 from income. This limit also applies to spouses, so in total they can make a deduction in the amount of PLN 106,000. | ||

| Investment relief for farmers | Relief granted to agricultural tax payers for expenses incurred for the purchase and installation of photovoltaic, wind and biogas installations and water fall | The relief is granted after the completion of a given investment and consists in deducting from the agricultural tax due on land located in the commune in which the investment was made in the amount of 25% of investment outlays documented by the accounts. | ||

| Regulatory mechanisms | Feed-in-tariff system | The FIT system is a mechanism covering installations with an installed capacity of less than 500 kW | Producers of electricity from biogas, biomass and hydroelectric power plants | The generator is entitled to conclude with the obligated seller a contract for the sale of electricity at a fixed price, which is 90% of the reference price |

| Feed-in premium system | The FIP system is a mechanism covering installations with an installed capacity of not less than 500 kW and not more than 1 MW. | Producers of electricity from biogas, biomass and hydroelectric power plants | The system is based on subsidies to the market price, i.e., covering 90% of the value of the so-called negative balance, which is the difference between the reference price announced for a given installation and the market average value of electricity sales | |

| System of net-metering | The system is valid until 31 March 2022—for prosumers with an installation connected to the power grid | Prosumers producing electricity in PV up to 50 kWp | Discount in installations up to: −10 kWp in a ratio of 1 to 0.8; −50 KWp in a ratio of 1 to 0.7. Prosumers who receive permission to connect micro-installations to the network until the date of entry into force of the Act will be settled on the current discounted rules for 15 years. | |

| System of net-billing | System valid from 1 April 2022—for new electricity prosumers | Prosumers producing electricity. | Prosumers will sell surplus energy introduced into the grid, will have a deposit—records of funds kept monthly and from it will be able to pay for the energy consumed | |

| PPAs | A contract for the purchase of renewable electricity on the basis of which a natural or legal person agrees to purchase renewable electricity directly from an electricity producer | Producer and consumer of electricity | In Poland, various models of PPAs are possible and acceptable: - on-site—the manufacturer’s RES installation is located directly at the recipient’s receiving installation, - near site direct wire RES installation is located in the vicinity of the recipient, and the electricity is transmitted by a dedicated distribution line, - off site—generated electricity from RES installations, is sent to the recipient via the transmission |

| Variable Category | Specification | Unit | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic variables | GDP in Poland | (PLN billions) | X1 |

| The average price of electricity in Poland | (PLN/MWh) | X2 | |

| Expenditures on fixed assets to protect atmospheric air and climate | (PLN billions) | X3 | |

| Environmental variables | NOx emissions from the electricity energy sector | (thousands of tons) | X4 |

| Emission of SO2 by the electricity energy sector | (thousands of tons) | X5 | |

| Dust emission by the electricity energy sector | (thousands of tons) | X6 | |

| Greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity energy sector | (kt ekw. CO2) | X7 | |

| Industry variables | Total electricity energy production in Poland of which | (GWh) | X8 |

| -power plants | (GWh) | X9 | |

| -industrial power plants | (GWh) | X10 | |

| Electricity consumption in Poland | (GWh) | X11 |

| Prognostic Model | Miara Walidacji | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 | Y5 | Y6 | Y7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause-and-effect | MAPE | 0.095 | 0.031 | 0.115 | 0.175 | 0.172 | 0.010 | 0.085 |

| RMSE | 323.272 | 6.617 | 59.317 | 69.677 | 144.917 | 13.032 | 309,909.010 | |

| RMSPE | 0.204 | 0.040 | 0.151 | 0.364 | 0.126 | 0.003 | 0.176 | |

| Brown | MAPE | 0.151 | 0.042 | 0.102 | 0.461 | 0.125 | 0.007 | 0.151 |

| RMSE | 487.302 | 7.024 | 117.986 | 96.306 | 377.688 | 7.955 | 486,839.235 | |

| RMSPE | 0.189 | 0.056 | 0.158 | 0.544 | 0.152 | 0.008 | 0.189 | |

| Holt | MAPE | 0.181 | 0.117 | 0.103 | 0.408 | 0.109 | 0.028 | 0.138 |

| RMSE | 784.176 | 23.495 | 112.727 | 92.488 | 379.613 | 41.576 | 618,551.631 | |

| RMSPE | 0.246 | 0.136 | 0.162 | 0.526 | 0.135 | 0.044 | 0.190 | |

| Winters | MAPE | 0.117 | 0.070 | 0.154 | 0.602 | 0.142 | 0.009 | 0.255 |

| RMSE | 407.653 | 12.065 | 131.649 | 103.208 | 475.744 | 13.738 | 600,937.960 | |

| RMSPE | 0.178 | 0.106 | 0.224 | 0.637 | 0.195 | 0.014 | 0.314 |

| Prognostic Model | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 | Y5 | Y6 | Y7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause-and-effect | 0.7190 ** | 0.9967 *** | 0.9929 *** | 0.3007 | 0.9981 *** | 0.9197 *** | 0.9434 *** |

| Brown | 0.9966 *** | 0.9740 *** | 0.9880 *** | 0.8343 ** | 0.9220 *** | 0.9193 *** | 0.3247 |

| Holt | 0.9828 *** | 0.9770 *** | 0.9482 *** | 0.9895 *** | 0.1208 | −0.4336 | −0.3996 |

| Wintersa | −0.4703 | 0.9843 *** | 0.9574 *** | 0.9736 *** | 0.7367 ** | 0.1319 | 0.8195 * |

| Y1—capacity installed including hydroelectric power plants in professional power plants (GW) | ||||

| Explanatory variables | B | Std.Dev. | p | R2 |

| W. free | 2061.151 | 193.509 | 0.000 | 51.695% |

| X5 | 1.638 | 0.423 | 0.002 | |

| Y2—Biogas installations (MW) | ||||

| Explanatory variables | B | Std.Dev. | p | R2 |

| W. free | −20.0743 | 8.6708 | 0.038 | 99.02% |

| X1 | 0.096 | 0.015 | 0.000 | |

| X3 | −10.035 | 4.328 | 0.043 | |

| X4 | −0.987 | 0.161 | 0.000 | |

| X7 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.033 | |

| X8 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| Y3—Biomass installations (MW) | ||||

| Explanatory variables | B | Std.Dev. | p | R2 |

| W. free | 952.845 | 1063.773 | 0.391453 | 99.29% |

| X1 | 0.753 | 0.138 | 0.000 | |

| X3 | −152.227 | 38.793 | 0.003 | |

| X4 | −5.044 | 1.443 | 0.006 | |

| X7 | −0.015 | 0.005 | 0.010 | |

| X8 | 0.032 | 0.007 | 0.001 | |

| Y4—Solar installations (MW) | ||||

| Explanatory variables | B | Std.Dev. | p | R2 |

| W. free | 3288.597 | 930.145 | 0.006 | 87.982% |

| X1 | 0.766 | 0.091 | 0.000 | |

| X8 | −0.028 | 0.006 | 0.001 | |

| Y5—Wind energy installations (MW) | ||||

| Explanatory variables | B | Std.Dev. | p | R2 |

| W. free | −5373.940 | 2060.655 | 0.026 | 99.43% |

| X1 | 1.854 | 0.409 | 0.001 | |

| X3 | −375.959 | 77.954 | 0.001 | |

| X4 | −36.984 | 4.058 | 0.000 | |

| X9 | 0.046 | 0.016 | 0.017 | |

| X10 | 0.849 | 0.194 | 0.001 | |

| Y7—Energy from RES (MW) | ||||

| Explanatory variables | B | Std.Dev. | p | R2 |

| W. free | 4,670,506.497 | 2,425,406.916 | 0.076 | 48.390% |

| X5 | 2034.811 | 567.634 | 0.003 | |

| X9 | −19.249 | 6.905 | 0.015 | |

| Y6—Hydropower Installations | |

|---|---|

| Forecast horizon | Alpha |

| h = 1 | 0.533474 |

| h = 2 | 0.383742 |

| h = 3 | 0.303612 |

| h = 4 | 0.255496 |

| Year | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 | Y5 | Y6 | Y7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2182.533 | 293.5098 | 1697.77 | 530.5487 | 7265.854 | 975.8987 | 2,235,184 |

| 2022 | 2105.383 | 332.03 | 1940.236 | 653.0178 | 8409.41 | 975.6088 | 2,196,625 |

| 2023 | 2027.666 | 375.3642 | 2207.836 | 769.7024 | 9690.534 | 969.7484 | 2,151,760 |

| 2024 | 1955.97 | 426.6483 | 2528.482 | 912.3445 | 11183.87 | 976.2505 | 2,124,591 |

| Year | Type of Ex Ante Prediction Error | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 | Y5 | Y7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | absolute | 166.048 | 4.385 | 39.308 | 57.569 | 96.046 | 170,048.958 |

| relative | 7.608% | 1.494% | 2.315% | 10.581% | 1.322% | 7.608% | |

| 2022 | absolute | 183.355 | 5.267 | 47.214 | 71.477 | 115.769 | 197,505.638 |

| relative | 8.709% | 1.586% | 2.433% | 10.946% | 1.377% | 8.991% | |

| 2023 | absolute | 201.287 | 6.306 | 56.527 | 87.873 | 139.274 | 226,450.964 |

| relative | 9.927% | 1.680% | 2.560% | 11.417% | 1.437% | 10.524% | |

| 2024 | absolute | 218.161 | 7.617 | 68.283 | 108.214 | 167.692 | 261,934.571 |

| relative | 11.154% | 1.785% | 2.700% | 11.861% | 1.499% | 12.329% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazurek-Czarnecka, A.; Rosiek, K.; Salamaga, M.; Wąsowicz, K.; Żaba-Nieroda, R. Study on Support Mechanisms for Renewable Energy Sources in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 4196. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15124196

Mazurek-Czarnecka A, Rosiek K, Salamaga M, Wąsowicz K, Żaba-Nieroda R. Study on Support Mechanisms for Renewable Energy Sources in Poland. Energies. 2022; 15(12):4196. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15124196

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazurek-Czarnecka, Agnieszka, Ksymena Rosiek, Marcin Salamaga, Krzysztof Wąsowicz, and Renata Żaba-Nieroda. 2022. "Study on Support Mechanisms for Renewable Energy Sources in Poland" Energies 15, no. 12: 4196. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15124196

APA StyleMazurek-Czarnecka, A., Rosiek, K., Salamaga, M., Wąsowicz, K., & Żaba-Nieroda, R. (2022). Study on Support Mechanisms for Renewable Energy Sources in Poland. Energies, 15(12), 4196. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15124196