1. Introduction

In the present day, globalization processes, a high level of innovation, and high levels of investment expenditure have caused fast socioeconomic development in most world economies. These processes have also an impact on the development of new lifestyles and consumption styles which have contributed to the establishment of the renewable energy sector, which is currently one of the fastest developing branches of the global economy [

1].

Entrepreneurship is considered to be a key factor in economic development and is a factor that increases living standards [

2]. Entrepreneurship can be defined as a process which comprises actors searching for opportunities and generating new knowledge, and comprises the co-evolution of knowledge, firms, industrial structures, and institutions [

3]. According to traditional entrepreneurship policy, policy making is mostly top-down and the implementation of this kind of policy is mainly undertaken at the national level [

4]. Entrepreneurship policy initiatives have been argued to be implemented without much coordination and to be insufficiently focused on maximizing the positive effects between complementary actions [

5]. Policymakers responsible for supporting entrepreneurs rely on current and updated measurements of entrepreneurship and system approach towards more holistic activities. They are focused on developing connections through network structures, building new institutional capabilities, and producing benefits from synergies between different stakeholders [

6,

7]. The growing prominence of entrepreneurship stimulation policies has drawn the attention of researchers to the local and regional causes and significance of the activities of local government. Local government (LG) is increasingly involved in supporting entrepreneurship and local development [

8]. The role of LG in local development has been widely discussed in research studies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], which have pointed out that local, regional, and national entrepreneurial development programming is complex, dependent on the type of organization and stakeholders involved, and requires coordination. The research findings published in [

16] indicated that policy makers need to understand the role of public sector institutions in the creation of local entrepreneurship, as this role can extend into innovative leadership in governance of enterprises and entrepreneurship at the local and regional tiers.

The developing economy and development of entrepreneurship require constant input of energy, the demand for which is consistently growing. However, the economic and ecological aspects of this energy balance should be a priority. Of course, energy planning should be done in such a way to ensure that all consumer needs for energy supply are met [

17]. It is worth to emphasizing that in Poland, coal continues to be the most important fuel source for electricity production, even though its market share is declining. The process of decarbonization is very important and it has had an essential impact on the conversion of the energy sector in Poland [

18].

LG can stimulate entrepreneurship through local legal regulations and organizational and institutional solutions, and can influence the location of new companies through area management concerning the use of public property, spatial development plans that precisely indicate the principles of area management, and by creating conditions conducive to the development of entrepreneurship [

19]. LGs should make decisions and undertake activities that are environmentally friendly and are also acceptable by society [

18,

20]. Recent research contributions related to forms of entrepreneur support by LGs refer to the potential investment attractiveness of local administrative units and entrepreneurial activities undertaken by LGs [

16].

LG can undertake activities and support institutional solutions to stimulate entrepreneurship, thus promoting the development of regional and local economies [

21]. However, not all LGs have developed self-enforcement mechanisms for supporting local entrepreneurship [

22]. Institutions at a regional and local level [

6] matter because they may support active behavior of LGs. Paying attention to local and micro-environment conditions for enterprises is recommended by scholars, e.g., [

23] recommends undertaking in-depth research on factors affecting the degree of entrepreneurship in regions to identify and isolate them. In addition to the activities of LGs aimed at supporting entrepreneurship in the economic context, a group of activities related to supporting ecological solutions should be highlighted. Among LG activities, fostering local sustainable development by enhancing entrepreneurial activity has been discussed [

24]. These activities are not the key point of our research; however, they constitute a significant group of activities and give a new role to LGs.

Unfortunately, there is insufficient entrepreneurial activity in the public sector. This may be related to the risk aversion of public organizations and their bureaucratic structures [

25].

In the subject literature, there is a substantial amount of research on LG instruments and activities that support entrepreneurs and local economic growth [

26]. There is also ample research confirming that government policies and regulations can promote or hinder innovation [

27]. Local authorities play a complementary role to national policy in the context of supporting both innovation in the economy and the development of a sustainable economy [

28]. The development of concepts focusing on entrepreneurship in the public sector led us to the analysis of the role and place of LGs in creating a local entrepreneurship environment. Finally, stimulation of local entrepreneurship and local commerce through a concrete set of initiatives is indicated as one of the key areas for mitigation in local contexts of the effects of the global pandemic which took place in 2020 [

29]; therefore, our paper is intended to identify and assess the significance of LGs’ different bottom-up initiatives for supporting entrepreneurship development at a local level. Bottom-up initiatives were purposefully selected as, in comparison, top-down initiatives led by the central government have proven to be prone to multiple failures and also to be ineffective from the perspective of local and regional disparities [

30]. A key element of the bottom-up approach proposed by Carvalho and Smith [

30] was encouragement of local entrepreneurship. In the present study, we investigated what kind of activities aimed at supporting the development of local entrepreneurship predominantly are undertaken by LGs in Poland.

In the paper, we refer to an entrepreneurial notion of LG, which has been used by researchers in several contexts, e.g., Bellone and Goerl [

31], Moon [

32], and Luke [

33,

34]. In our research, LG refers to formal authorities of local administrative unit (LAU in EU nomenclature) level 2, formerly NUTS level 5, which are represented by public sector managers acting on behalf of and for the public good of local groups, and who also usually live and work in local regions. In order to achieve the aim of the paper and identify the activities of LGs, the authors analyzed in detail the 447 local administrative units of one of the Central and Eastern European countries—Poland. Poland is an example of a country transformed via the most effective economic transformation approach of “shock therapy” [

35]. The country has experienced transformation of the economy and territorial divisions, as well as decentralization of power and finance. There has been a transition from top-down to bottom-up management. We decided to analyze a country in which changes could be observed over a relatively short time (30 years since the transformation of the post-Soviet economy into capitalism). Poland is a country in which the private sector has existed since the 1990s and has been supported since 2000, and it could draw on global models of LG activities. Worldwide, many countries are looking for bottom-up activities that will result in entrepreneurship development alongside state government policy and frameworks. Therefore, this research has implications both for scholars who study local development and the geography of entrepreneurship and for policy makers.

On the basis of the conducted literature review, we noticed a research gap regarding LGs’ entrepreneurial activities, particularly regarding the relationship between LGs’ entrepreneurial activities (herein called bottom-up initiatives) and the local entrepreneurship level (understood here as the number of entrepreneurs active within the territory of the LG). The goal of the present paper is to present different bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LGs in Poland to support entrepreneurship in their local units. Another aim of the research was to investigate whether there is any relationship between a higher variety of bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LG managers and a higher local entrepreneurship level.

The paper is organized as follows: the first section presents the literature review concerning the theoretical background of entrepreneurial LG. The second section describes the methodology of the research. In the third part, the results of our own research are presented and then discussed. The last section concludes the paper by commenting on the research and suggesting possible future developments.

2. Entrepreneurial Local Government: Theoretical Background

In order to define entrepreneurial LG, we refer to previous descriptions of entrepreneurship and then outline their connections with LG. Entrepreneurship is usually associated with the private sector; however, internal entrepreneurship exists in all types of organizations, including the public sector. It is very important to emphasize that the public sector operates under different conditions from the private sector, particularly in areas such as environment, objectives, responsibilities, and financing [

36]. Entrepreneurship in the public sector has been defined by Leyden and Link as the “supporting of innovative public policy initiatives that create better economic prosperity by changing a status-quo economic environment into one that is more favorable to entrepreneurs” [

37]. For example, entrepreneurship can be manifested through different changes, e.g., changes in laws, regulations, etc., in order to boost entrepreneurship and foster innovation and economic development [

38]. Entrepreneurs can be individuals or group of actors, but they need a well-developed leadership capacity in order to determine the direction for change with, through and by people [

39]. To sum up, entrepreneurial LG can be understood as LG (meaning people who have legal authority and are responsible for the development of a particular LG unit) that undertakes different initiatives and actions in order to create a supportive entrepreneurship environment, advancing socioeconomic development and the comparative attractiveness of the LG unit for inhabitants, tourists, entrepreneurs, etc.

Combining a strategic vision of development with bottom-up activities undertaken by LGs provides opportunities for effective economic performance [

40]. LGs can partly influence factors such as economic environment, social environment (labor, demographic situation, migration, crime level, etc.), legal environment (laws and regulations, tax policy), competition, and cultural environment (tradition, customs, values, norms, taboos, or beliefs). Numerous scholars have proven the impact of LG support on business activities [

41]. The attitudes, competencies, and actions of local authorities aimed at attracting investors are recognized as determinants of local development processes [

42].

“Top-down” and “bottom-up” theoretical approaches are the main ways of dealing with the development of entrepreneurship environments. One can find both opponents and supporters of these theories. The role of LG in socioeconomic development has been discussed in the scientific literature concerning local development [

43]. LG cooperates with inhabitants, entrepreneurs, and other local actors, as well as providing services for residents and businesses [

44]. Therefore, the activities of LG are very important in satisfying the needs of citizens and entrepreneurs [

45]. In this paper, LGs’ bottom-up activities are understood as nonobligatory activities supporting entrepreneurship that have an impact on the development of the local entrepreneurship environment. Bottom-up initiatives include promotional and organizational activities (e.g., conferences and meetings with entrepreneurs, supporting entrepreneurs in the field of advertising and promotion), training and consulting activities (e.g., legal and economic consultancy, training in business activities), and information activities including online (e.g., information about projects, entrepreneurship development programs, possibilities to obtain financial resources from EU funds, investments, available commercial premises, available co-working spaces, the activity of LG in social media).

LGs’ activities for entrepreneurship can be discussed as a separate system and as a part of the national policy. It is significant that particular LGs differ from each other, causing unequal entrepreneurial activity and explaining why the most important LG factors for entrepreneurship development have to be searched for [

46]. Moreover, some LGs have self-enforcement mechanisms to support local entrepreneurship via a variety of bottom-up initiatives and some do not [

19].

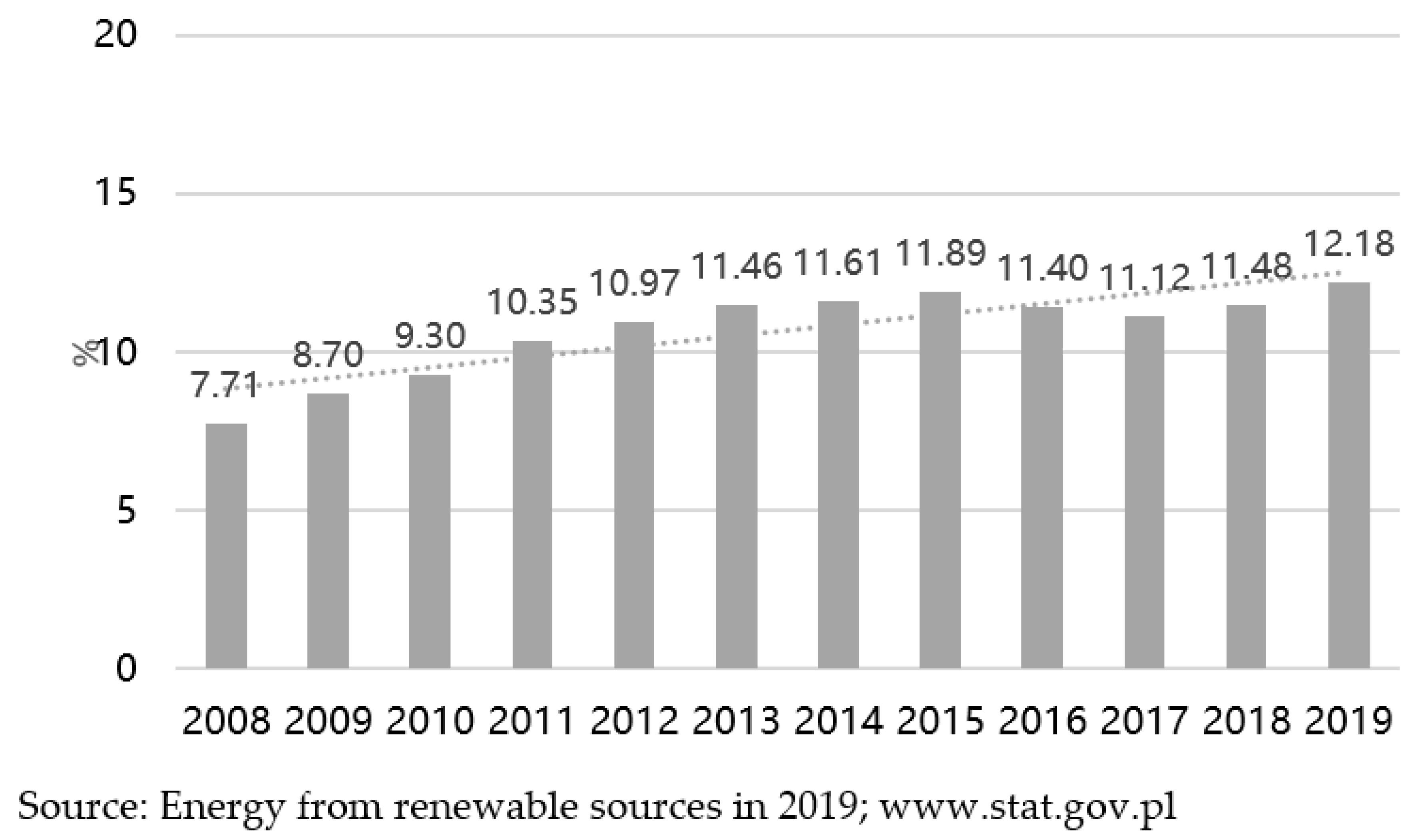

As mentioned earlier, there has been a notable increase in the importance of activities related to supporting ecological solutions. The obligation to produce renewable energy results from international agreements, EU law, and national documents. At the local level, the reason to invest in renewable energy sources (RES) is to ensure energy independence. The need to act results from the recommendations of Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources. Poland and other member states are obliged to ensure a certain proportion of energy from renewable sources in their gross final energy consumption (see

Figure 1).

The importance of this challenge and the set requirements mobilized countries to decentralize their activities. Projects have been implemented at the government level as well as directly involving LGs. Therefore, it has become necessary to look for a compromise solution that takes into account the possibilities of LGs and the local energy market in relation to the achievement of the assumed goals. According to the current data from the main portal monitoring system for European Union funding (mapadotacji.pl), Polish LAU/LGs took part in and benefited from cofinancing for 1222 projects. The projects concern activities related to the construction of renewable energy sources as well as both direct and indirect activities aimed at reducing the consumption of high-emission energy.

Moreover, the Association of Municipalities Polish Network “Energie Cités” in Poland has been cooperating with LGs to shape the local low-carbon economy, efficient energy and renewable energy use, and environmental education and climate protection. Polish LGs have joined in the participation and implementation of international projects, of which the most recent are EnPower (low-cost methods and tools for alleviating energy poverty in a community), S3UNICA (intelligent energy-saving solutions on university campuses), MULTIPLY (cooperation between cities to integrate sustainable transport, energy, and spatial planning solutions), GRAD (green roofs as a tool of adaptation to climate change for urban areas—a German inspiration for Poland), EYES (young active participants in energy and climate planning in the city), and ENTRAIN (Interreg Central Europe: planning the development of heating systems using renewable energy sources to improve air quality) [

47].

The Research Hypothesis

The local entrepreneurship environment has mutual relationships with LG representatives who may, for example through changes in local taxes and charges, influence incentives for setting up a new business. There are many other factors including geographical, historical, socioeconomic, and political which also have direct impacts on the local entrepreneurship environment. Heffner and Klemens discussed activities and examples of public sector actions at the local level and focused on social, administrative, and technical services. The authors underlined importance of LGs’ activities for rural LAUs in particular [

48].

The bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LGs might correspond with the stimulation of entrepreneurship at a LAU level, and therefore might impact local development processes. In the paper, we decided to investigate this phenomenon at both the theoretical and empirical research levels.

Therefore, in this paper, based on the studies by Heffner and Klemens [

48] and Godlewska and Pilewicz [

49], the following hypothesis was examined: The higher the variety of bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LG managers, the higher the local entrepreneurship level.

In the methodology section, the authors describe how entrepreneurship level was measured or assessed.

We determined a higher variety of bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LG managers using information provided on LGs’ websites about entrepreneurship development programs, projects, or events; LGs’ activities on social media, i.e., Facebook or Twitter; providing free-of-charge training on how to set up a business activity; establishing a department for supporting local entrepreneurship that is open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs; and organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product). We defined a higher local entrepreneurship level as a higher number of active entrepreneurs in the LG territory in total.

3. Materials and Methods

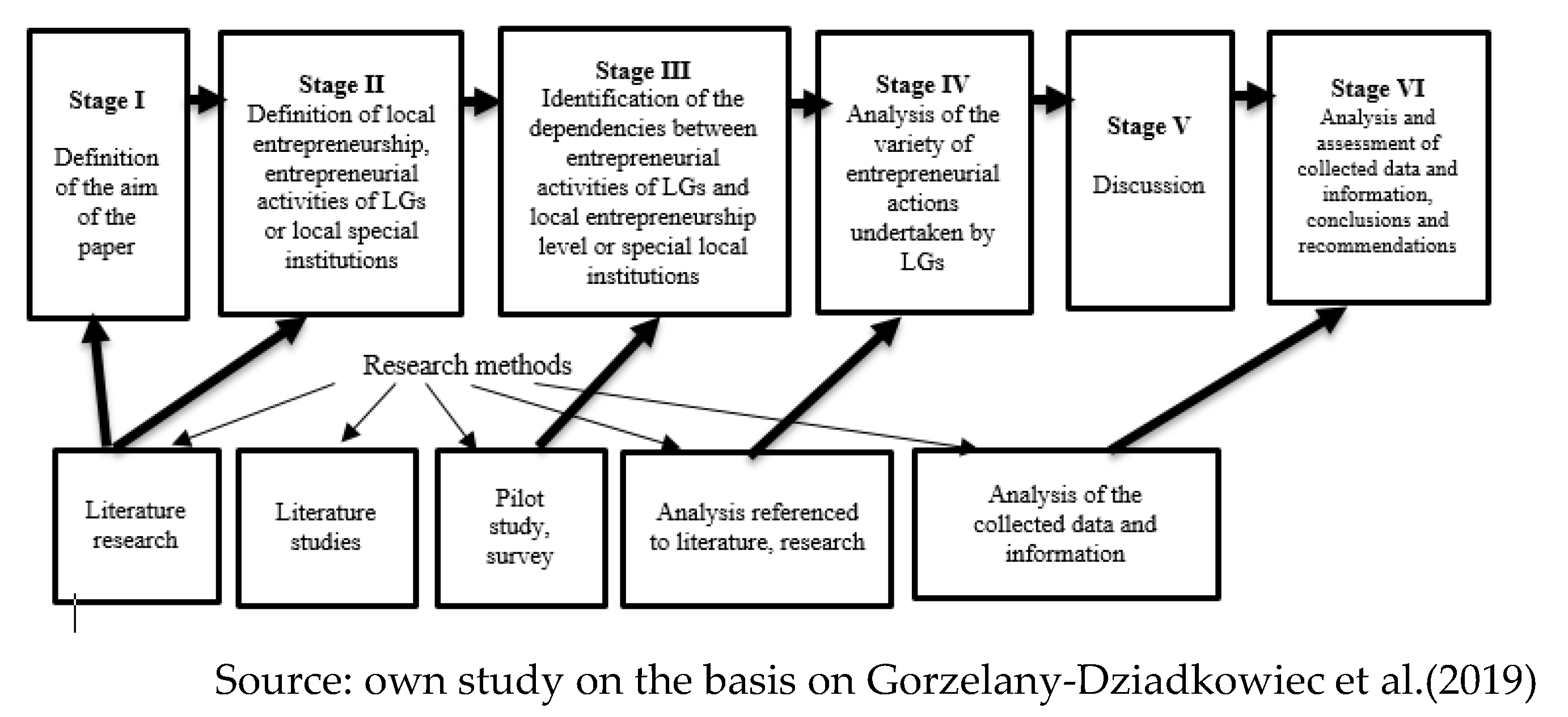

The geography of entrepreneurship highlights the critical importance of LGs for the development of business climates at a local level. In this paper, the authors drew upon theories of local economic development, geography of entrepreneurship, public entrepreneurship, and “top-down” or “bottom-up” theoretical approaches. Moreover, Olsson et al. [

8] and Xing et al. [

21] highlight the critical importance of LGs in studying entrepreneurship at the local level. For this reason, in response to calls for research on the interaction between entrepreneurial actions undertaken by LGs and local entrepreneurship development [

16,

29,

49], and to better understand the state of play and investigate research gaps, the authors chose a six-stage approach (see

Figure 2).

Despite the widely held belief that entrepreneurial activities undertaken by LGs matter when it comes to local entrepreneurship development, there were no studies that provided evidence of the significance of LGs’ different bottom-up initiatives for supporting the development of entrepreneurship at a local level.

The analytical framework of the paper is based on the methodology of stepwise regression analysis described by Agostinelli [

50] and Ing and Lai [

41].

In order to achieve the objectives of the paper, empirical research with representatives of Polish LGs residing in LAUs was conducted and data were statistically processed and interpreted. The survey was intended to verify the hypothesis and to check the relationships between LG bottom-up initiatives and local entrepreneurship level. The authors primarily utilized a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) research method to pilot and improve the electronic survey draft prepared with n = 50 representatives of LGs. The authors used stratified random sampling to collect answers from all three types of local administrative unit (urban, urban–rural, rural) from almost all (13 out of 16) voivodeships in Poland. The CATI pilot was performed between 5 and 14 June 2020.

Secondly, to ensure increased comprehensiveness of the questionnaire and fit to research objectives, authors performed in-depth interviews (IDIs) with n = 3 representatives using simple random sampling from the sample used for the CATI pilot, ensuring representation of one urban, one urban–rural, and one rural LG. The IDI pilot was performed between 22 and 30 June 2020. The pilot research allowed the authors to prepare a final questionnaire. Having finalized the research questionnaire, the authors utilized a third research method—an electronic survey based on the finalized, standardized questionnaire—which is presented in detail in

Appendix A. At the time of the study, there were 2477 local administrative units (LAU level 2, formerly the NUTS level 5) in Poland, which constituted the theoretical population, study population, and also the final research sample, as the authors decided to research all local administrative units. With an assumed 95% level of confidence parameter and a 5.0% expected error rate (requiring n = min. 333), final responses to the electronic survey were provided by 447 participants, which enabled the error rate to be lowered to 3.9%. The respondents of our research were representatives of local administrative units (managers). The electronic survey and coding of the answers were performed between 3 and 31 July 2020. To achieve a high level of responses and automation in answer coding, the authors used the professional research platform Webankietka, on which the electronic survey was deployed and then disseminated among the final research sample. The final research sample was fully representative (except for cities with district rights) in terms of corresponding with the prevalence of the types of local administrative unit within the total population of local administrative units in Poland: (i) rural municipalities (rural LGs) were 61% in the population vs. 59% in the sample; (ii) urban–rural municipalities (urban–rural LGs) were 26% in the population vs. 24% in the sample; (iii) urban municipalities (urban LGs) were 10% in the population vs. 11% in the sample; and (iv) cities with district rights (city LGs) were 3% in the population vs. 6% in the sample. However, these differences were considered insignificant. In our study, we investigated local regions—local administrative units (LAUs) level 2 (formerly know, as the NUTS level 5 for European Union statistical reporting)—which, in Poland, are represented by vogts, mayors, or presidents depending on the LAU size, and other LG managers such as heads of departments and heads of sections executing the duties of LAU office. Our research sample included LG managers such as vogts, mayors, and residents (62.5%), heads of departments (15%), and other LG managers such as senior clerks, junior clerks, and other staff for the delivery of public sector services for entrepreneurs (22.5%). A total 93% of respondents in the research sample had higher education and 89% of them had more than 5 years of professional experience. Of the researched respondents, 33% had gained previous professional experience in the business sector and 27% of them ran their own business entity. For not more than 1% of the research sample, a computer imputation procedure using IMB SPSS version 26 was applied in order to eliminate missing records.

Our dependent variable was the number of active entrepreneurs (understood as business entities) in the LG territory in total. The selection of our dependent variable was underlined by the literature detailing measurement of entrepreneurship at LAU level. The formal and legally traceable characteristic of new enterprise registration has been proposed as a measure of entrepreneurship (Giones and Fox, 2019). New enterprise registration or registered activity of existing enterprises in respected business records are indicated as entrepreneurship markers at the LAU level (Katz and Gartner, 1988). These data were collected from the Central Statistical Office of Poland for the year 2019. The independent variables were chosen from the above-mentioned electronic survey of Polish LGs. The selection of independent variables was underlined by the literature detailing bottom-up initiatives at the LG level, which refer to activities undertaken beyond those defined as obligatory in the locally relevant legal acts. The list of independent variables, i.e., the bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LGs in our research, was as follows:

- (a)

Providing information on the LG website about entrepreneurship development programs, projects, or events (Shackelton, Fisher, Dawson 2004; Zaidi, Qteishat 2012);

- (b)

LG activity on social media, i.e., Facebook or Twitter (Agostino, 2013; Faber, Budding, Gradus, 2020);

- (c)

Providing free-of-charge training on how to set up a business activity (Jones 2007; Grujic 2019, Richert-Kazmierska, 2012)

- (d)

Establishing a department for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs (Massón-Guerra, 2019; Munoz, Kibler, 2016);

- (e)

Organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) (Grodek-Szostak, Siguencia, Kajrunajtys 2019; Kabus, 2017).

Data for the independent variables were gathered through the survey performed on the research sample of LG managers detailed above.

The independent variables we decided to investigate, such as providing information on LG websites and LG activity on social media have also been discussed in the context of digitization activities oriented towards the decarbonization of economy by public administration institutions [

51]. Social media, the usage of which by LGs we decided to investigate, is the subject of contemporary research as a promising channel for increasing interest and engagement in energy and environmental sustainability topics [

52]. This aspect of our research design contributes to the exploration of energy transition in Poland and the channels used for related public education [

1]. The control variable were collected from the Central Statistical Office of Poland for the year 2019 and were as follows:

- ➢

total income per capita—hereinafter referred to as INCOME;

- ➢

total expenditure per capita—hereinafter referred to as EXPEND;

- ➢

share of registered unemployed in the working age population—hereinafter referred to as UNEMPL.

The empirical model was synthesized in the following equation:

where

- ➢

NoAEi = the number of active entrepreneurs in the LG territory in total;

- ➢

i = a particular LG;

Qn = the bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LGs, such as providing information on LG websites about entrepreneurship development programs, projects, or events (Q1); LG activity on social media, i.e., Facebook or Twitter (Q2); providing free-of-charge training on how to set up a business activity (Q3); establishing a department for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs (Q4); and organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (Q5);

- ➢

a1, a2, a3, a4, and a5 designate the factors that affect the number of active entrepreneurs in a LG territory in total other than Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, and Q5;

- ➢

b1, b2, b3, b4, and b5 measure the change in the number of active entrepreneurs in a LG territory in total due to changes in Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, and Q5;

- ➢

Ɛni designated the error terms or the gap between the number of active entrepreneurs in a LG territory observed in total, and those estimated for a given value of Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, and Q5.

4. Results

The statistical results (see

Table 1) showed that the most popular bottom-up LG initiatives among LG managers were providing information on the LG website about entrepreneurship development programs, projects, or events, and LG activity on social media, i.e., Facebook or Twitter. Moreover, an average of 2853 entrepreneurs were active on each LG territory.

The selected dependent variable was the number of active entrepreneurs on LG territory in total, due to the fact that the distribution of the number of active entrepreneurs on LG territory in total (see

Table 2) was symmetrical (under 1).

The regression analysis was performed with a stepping procedure. At each step of analysis, the independent variable with the lowest probability corresponding to F of those not yet in the equation was added to the model, if the probability was sufficiently small (see

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9). Variables already included in the regression equation were removed from the equation if the associated probability of F became sufficiently high. The procedure ended when no variable could be excluded or included. Moreover, stepwise regression analysis allowed only those predictors (variables) that significantly predicted the dependent variable, i.e., the level of local entrepreneurship development, to be entered into the model. Therefore, from the many unnecessary variables that did not contribute anything to the model, we obtained those variables that actually affected the prediction of the dependent variable. Moreover, the stepwise method allowed us to eliminate the problem of collinearity. Successively introducing predictors also took into account the mutual correlation between them.

All independent variables, such as organizing events at the national and regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs; establishing departments for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs; or LG activity on social media, i.e., Facebook or Twitter, were correlated with the dependent variable, i.e., the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory (see

Table 3). These correlations were significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

In order to verify which of the variables best explained the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory, a linear regression analysis was performed using the stepwise method. Organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product); establishing departments for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs, and LG activity on social media, i.e., Facebook or Twitter, were introduced into the model in three steps (F value in regression analysis (3, 441) = 21.69;

p < 0.001). Together, these variables accounted for 12.3% of the variance of the dependent variable, i.e., the number of active entrepreneurs in total on LG territory (see

Table 5).

Organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) turned out to be the strongest predictor. The second strongest predictor was establishing a department for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs (see

Table 8). The number of entrepreneurs in total active on a LG territory grew if predictors of bottom-up initiatives such as organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) and establishing a department for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs were met (see

Table 9).

In order to verify if control variables the best explained the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory, a linear regression analysis was performed using the stepwise method.

All control variables, including total income per capita, total expenditure per capita, and share of registered unemployed in the working age population, were correlated with the dependent variable, i.e., the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory (see

Table 10). These correlations were significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Total income per capita, total expenditure per capita, and share of registered unemployed in the working age population were introduced into the model in three steps (F value in regression analysis (3, 441) = 19.004;

p < 0.001). Together, these variables accounted for only 10.8% of the variance of the dependent variable, i.e., the number of active entrepreneurs in total on LG territory (see

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12). This means that the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory grew if predictors of control variables such as total income per capita, total expenditure per capita, and share of registered unemployed in the working age population were met.

5. Discussion

Authors all over the world have analyzed and discussed the instruments and activities used by local-level authorities in order to support local economic development [

9,

13,

19,

53,

54]. Most authors when assessing the degree of effectiveness of LGs’ instruments supporting entrepreneurship in Poland have pointed out the difficulties in Polish conditions. One study on this subject discovered that it is not easy to specify which instruments are the most effective and that it is important to use several different tools to support entrepreneurship simultaneously [

45]. It is also important to support sustainable entrepreneurship, by for example by enhancing use of renewable energy sources. This in turn depends on the pace of technological progress, on the pressure of different groups encouraging reduced emission of greenhouse gases, and, above all, on the possibilities of creating an integrated system of biomass production [

17]. Increasing the popularity of electric vehicles used by, for example, the business sector is one solution for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and helping the economy to become more sustainable [

55].

Godlewska and Morawska [

22] argue, in contrast with our results, that LGs without self-enforcement mechanisms do not support development of local entrepreneurship. However, our analysis revealed that bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LGs to support entrepreneurship such as organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) and establishing departments for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs correspond with the number of entrepreneurs in total active in LG territories, a measure which increased if the above-mentioned predictors of bottom-up initiatives were met. This means that bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LG managers may support the development of local entrepreneurship, i.e., increase the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory.

On the other hand, research conducted on Norwegian LGs, in contrast with our results, underlines the importance of leadership characteristic of LGs and the strength of the local economy for the support of local entrepreneurship by LGs [

46]. However, in our research, we focused on the impact of bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LG managers and we proved that the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory grew if the above-mentioned predictors of bottom-up initiatives were met. Nevertheless, the importance of leadership characteristics of Polish LGs and the power of local economy need further research.

Wołowiec and Skica [

19] highlighted, in line with our results, that activities of LGs such as the improvement of infrastructure conditions, the selection of areas for investment, the lease of communal facilities for economic activities, and the creation of capital back-up comprised of loan funds are important for the location of economic activity and may be also important for LG support of local entrepreneurship. However, they did not investigate whether the variety of bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LGs mattered for support of the development of local entrepreneurship. Our contribution to further development of the topic investigated by scholars resulted from noticing that what matters are bottom-up initiatives like organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) and establishing departments for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs, which correspond with the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory.

Moreover, our analysis revealed that bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LG have an impact on the total number of entrepreneurs active on LG territory. However, there are also other important factors which matter for the total number of entrepreneurs active on LG territory. One of such factor, according to Godlewska and Pilewicz [

49], may be the potential investor attractiveness of local regions. These other factors will require further investigation. At present, we can observe that governments more often support high-growth business than facilitate the creation of new firms [

4].

6. Conclusions

The results obtained from critical analysis of the literature showed that LGs undertake more activities of various resource intensiveness and complexity to strengthen entrepreneurship environments at a local level.

On the side of empirical research conducted, we have contributed to the existing evidence of Wolowiec and Skica by indicating a variety of initiatives undertaken by LGs to stimulate entrepreneurship at the local level. We have indicated that the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory grows if predictors of bottom-up initiatives such as organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) and establishing departments for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs are met [

19].

The key point of the LG policy is to undertake activities that not only stimulate the creation of new enterprises but also strengthen the performance of the already existing ones Though the traditional view of supporting entrepreneurship maintains that it is largely a function of policy makers at higher levels, LGs are increasingly involved in entrepreneurship through local initiatives [

8].

LGs are continuously challenged to transform and to offer efficient, effective, and economical services. With respect to the general exploratory research hypothesis, it can be concluded that LGs undertake various bottom-up initiatives aiming at fostering entrepreneurial activity in their territory. The most popular examples of these activities include providing information on LG websites about entrepreneurship development programs, projects, or events, and LG activity on social media, i.e., Facebook or Twitter.

Our results confirmed that the number of entrepreneurs in total active on LG territory grew only if predictors of bottom-up initiatives such as organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) and establishing departments for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs were met. Other bottom-up initiatives undertaken by LGs were not important for the development of local entrepreneurship. LGs can also contribute to the development of local economies through the development of institutional arrangements aimed at boosting entrepreneurial activity [

21].

To sum up, LGs are important actors that influence entrepreneurial activities [

56]. The results of our research are in contrast with the research conducted so far and show that it is very important that LGs undertake particular bottom-up initiatives such as organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) and establishing departments for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs, because only these initiatives have impact on the growth of the total number of entrepreneurs active on LG territory.

LGs which build a helpful entrepreneurship environment that causes a surge in the level of socioeconomic development and the comparative attractiveness of the LG are called entrepreneurial LGs. Therefore, LGs can support entrepreneurship through the development of the entrepreneurship environment. The paper concludes that LGs and their activity are an important factor influencing entrepreneurship. Thus, we recommend that all LGs undertake activities supporting entrepreneurship such as organizing events at the national or regional scale that enable networking among entrepreneurs (trade fairs, exhibitions, conferences, forums, competitions for the best entrepreneur/product) and establishing departments for supporting local entrepreneurship open to cooperation with local entrepreneurs, due to the empirically proven positive impact on the development of entrepreneurship, and then on the economic and social development of the local economy.

As Marks-Bielska [

57] and others have noted, in order for an LG to develop, it must have a certain level of efficiency in its executive activities, including the right skills of leaders [

57]. This result inspired us to conduct further research on the importance of leadership characteristics of LG managers in the development of entrepreneurship at the local level.

Our empirical research method proved to be effective due to the sampling applied and response ratio achieved, which enabled proper statistical reasoning. However, this study has several limitations. The first relates to the significant diversity of LGs’ activities in different LAUs and further research will be require to define and measure the effective ones. Another limitation of our research relates to the rigorousness criteria applied for the literature review, referring to databases selected and used, protocol of data extraction, and selection and elimination from further studies. Second, there is a limitation related to the use of a single country’s data. The focus on a sample of LAUs from Poland, on the one hand, was a deliberate action (to take into account specificity of conditions), but on the other hand may bring additional issues related to the implementation by LGs of specific activities to support entrepreneurship. Therefore, research in other countries should be developed. A further limitation relates to the number of factors supporting local entrepreneurship. Future research may develop classifications of bottom-up initiatives to increase their preciseness and describe their results. In addition, future research may focus on the interdependencies of LGs and local entrepreneurship and on the development of indicators to measure the quality and quantity of LGs’ activities.

To date, to reduce the economic inequality between countries and overcome the ecological crisis, many projects have been established. Reducing fossil fuel consumption and adopting more conservative patterns of natural resource consumption are key challenges for well-developed countries [

18]. The study has several implications for energy security. Energy security is a public good; thus, encouraging sustainable behavior and environmental identity should be a key point of public policy. Undoubtedly, both renewable energy projects and LG support for ecologically friendly behavior are necessary [

52]. In the present research, we only underline the importance of separate and unfathomable activities of LG referring to renewable energy source. We recommend the planning and implementation of detailed research on this type of LG activity and its connections with the entrepreneurial activities of the business sectors in particular LAUs. We are interested in the benefits that these activities bring not only for LGs in the environmental context, but also as direct economic benefits for companies.

Moreover, our research can be a point of reference and a starting point for extended future research on initiatives undertaken by LGs to stimulate the creation and absorption of innovations at the local level, including environmental ones. The implementation of renewable energy policy by LG can make a significant contribution to mitigating climate change, improving energy security, and increasing social, economic, and environmental benefits [

58]. Our research can be a starting point for a further research concerning, for example, the needs of entrepreneurs and their expectations of LG activities. It would also be interesting to investigate how local business entities assess the activities of LGs in the field of supporting entrepreneurship (which activities are the important and useful for them and which are not). Another interesting subject for future research in this field could be the analysis of LG activities in the context of developing innovative local units, especially in the field of renewable energy sources.

.

.