1. Introduction

Municipal solid waste (MSW) is a complex mixture produced by households as well as commercial and service activities. The current treatment and disposal methods include landfilling, material recycling (especially for metals, glass, paper products, and plastics) and energy recovery in waste-to-energy (WtE) plants. Composting and biogas production (via anaerobic digestion) are also employed for biodegradable waste fractions. Sadly, adequate waste management is only widespread in parts of Europe, North America, and Asia. Worldwide, an estimated 70% of the solid waste is dumped in uncontrolled dumps or landfills, causing an array of hygienic and environmental problems, including uncontrolled CH

4 emissions, a highly potent GHG (Greenhouse Gas) [

1]. With an increasing population, improving standards of living for many as well as stronger environmental awareness can only mean that more MSW will be produced in the future, but also that both material recycling and WtE capacities will have to increase on a massive scale.

The development soon-to-be impacting the waste management sector is related to climate change and GHG emissions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scenarios [

2] modelled for Earth’s climate evolution in the coming decades show that the Paris’ agreement ambitious goals to mitigate temperature increase can only be met with carbon capture and storage (CCS), and, in all probabilities, solutions allowing for negative CO

2 emissions, in other words, removing CO

2 from the atmosphere. With MSW being mainly biogenic, more than 50% in most European cases [

3], CCS integrated with WtE can be a viable CO

2 negative alternative in addition to BECCS (Bioenergy carbon capture and storage).

How can CCS be applied to WtE? The main characteristics of WtE are rather different from oil/gas/coal-fired power/heat generation systems, for which CCS has been largely developed. The vast majority of WtE plants in the world are grate-fired installations with a MSW throughput of approx. 200,000 tons per year per plant [

3] (European average) and producing heat (district heat, processed heat for the industry) and/or power. Western MSW has a lower heating value of about 8–12 MJ/kg and is highly heterogeneous. It contains many minor and trace compounds not found in other solid fuels, and its properties will vary over time, both on a minute and season basis, making stable operation a challenge and limiting overall energy efficiency. Each ton of MSW produces about one ton of CO

2 during combustion. CO

2 concentrations in the flue gas are comparable to (wet basis) coal incineration, and a highly advanced flue gas treatment is required to meet emissions values limits. WtE plants are on average much smaller than coal-fired power plants, making downscaling and economy of scale an issue when considering CCS integration.

Despite these specific conditions, post-combustion CO

2 capture based on solvents such as amines appears to be promising, as demonstrated by the pilot testing performed by Fortum Oslo Varme in their WtE plant in Klemetsrud, Oslo, Norway [

4]. However, for greenfield applications, innovative capture solutions can offer additional benefits. Oxyfuel combustion is combustion using pure oxygen or a mixture of oxygen and (recirculated) flue gas (i.e., mainly CO

2) as an oxidizer instead of using air. In this context, the advantages of oxyfuel combustion for CCS are obvious: the exhaust gas is mainly composed of CO

2 that can easily be captured through water condensation and removal of impurities. The proposed technological combination (oxyfuel combustion + energy production + flue gas treatment + CCS) for a new generation of WtE plants will offer net negative CO

2 emissions + minimal emissions + energy recovery (heat and power from non-recyclables) + safe thermal waste treatment (sanitization, destruction of organic contaminants, reduction in volume and weight). This will make WtE an integral part of a more circular economy.

Oxyfuel combustion has so far been developed and demonstrated for coal [

5], for which it has shown great potential. The use of pure oxygen in addition to air or full substitution for combustion in industrial processes has been known for many years [

6] for its advantages in terms of higher temperature, lower flue gas volumes, and higher heat transfer rate, amongst others. In the context of MSW oxyfuel combustion integrated with CCS, it seems preferable to keep or modified as little as possible the main features of air-fired grate combustion to benefit from this robust technology experience and know-how. This would include keeping temperatures close to air combustion (especially in the combustion chamber) via flue gas recycling to avoid the need for expensive materials and alloys as well as prevent ash-related challenges such as slagging. However, only limited work has been performed on biomass and waste. The studies using coal have only limited relevance as these three fuels are fundamentally different. Key fundamental findings from oxyfuel combustion of coal include: (1) the oxyfuel combustion environment (N

2, CO

2) affects the combustion process (devolatilization and char burnout), e.g., the overall char burning rate is lower with CO

2 than with N

2 [

7,

8]; (2) to obtain flame stability and ignition similar to air, a O

2 concentration of 30 vol% is necessary in CO

2 [

9]; (3) a general observation (but it cannot be generalized) is that NO

x emissions are lower in oxyfuel combustion on an energy basis (mg/MJ) [

10] but the NO

x concentration (ppm or mg/Nm

3) in the flue gas of oxy-combustion is usually similar or higher than that in air combustion [

11].

As already mentioned, MSW is highly heterogeneous and contains high levels of moisture and ash, as well as several minor and trace elements not found in coal. Existing studies are focusing on extremely small-scale experiments (thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) for kinetics studies) of individual waste or biomass fractions or investigate the pyrolysis process as the first stage of combustion. Results concerning the combustion process and selected emissions have shown that oxyfuel combustion of MSW is worth exploring further [

12]. Key findings on fundamental aspects (TGA of single waste fractions) are similar to coal’s, e.g., the negative effects of CO

2 on flame stability and ignition [

13], or NO

x emissions that are usually reported to decrease with oxy fuel combustion but not in all studies [

14,

15].

However, the topic requires more laboratory-scale (larger than TGA), well-controlled experimental studies with MSW-like mixtures, rather than individual homogeneous fractions and using advanced analytical measurements. It is especially interesting to explore several key aspects simultaneously in a continuous thermal conversion process, namely temperature, combustion stability, and emissions, as performed in this study.

In this work, we aim at demonstrating the feasibility of oxyfuel combustion with MSW using lab-scale experiments and discuss advantages as well as any showstopper for this technology in the context of CCS integration for WtE. We will carry out this work by comparing air and oxy-combustion characteristics for MSW at different conditions and determining the fundamental behavior of MSW during oxyfuel combustion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Set-Up

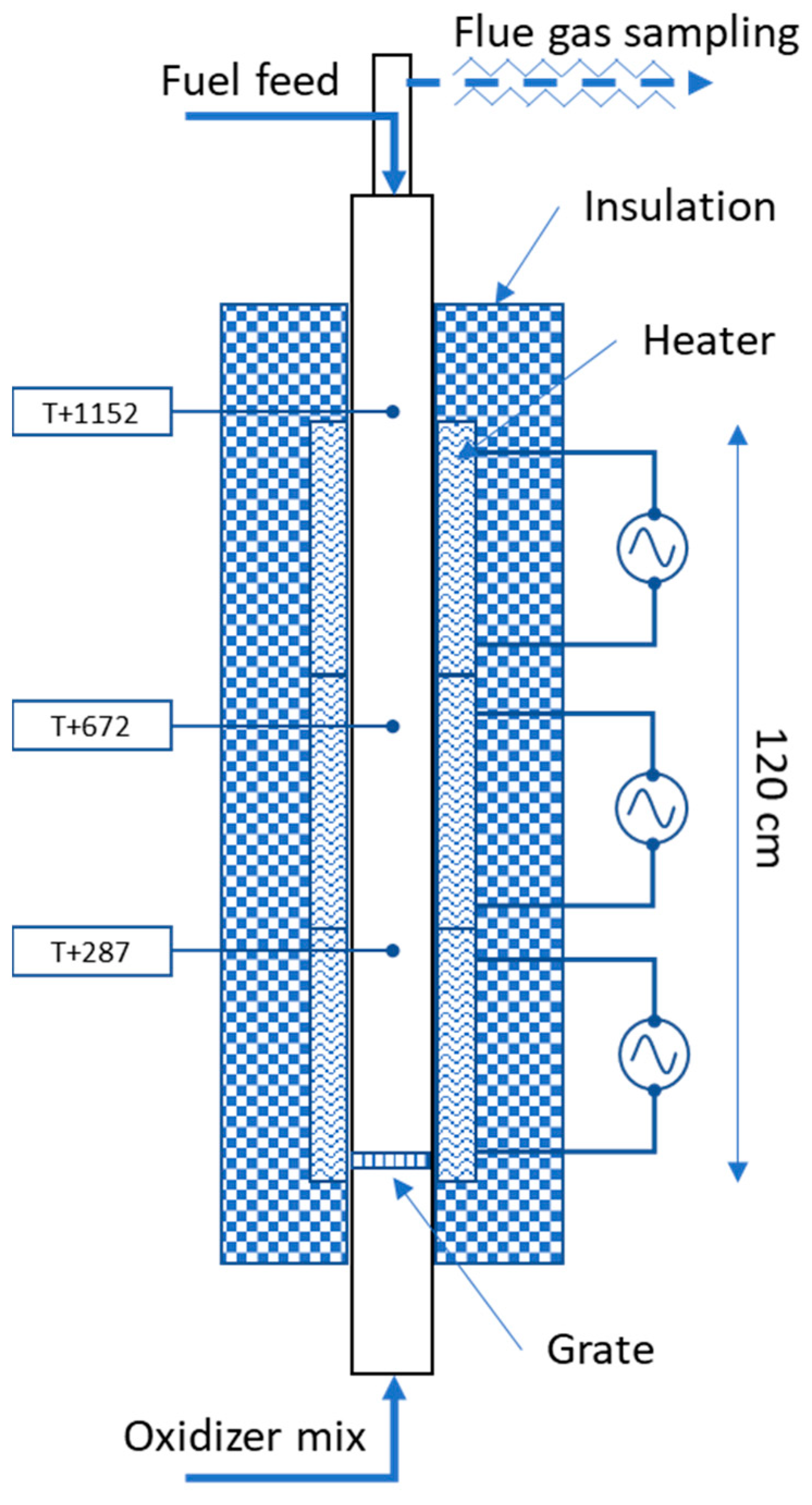

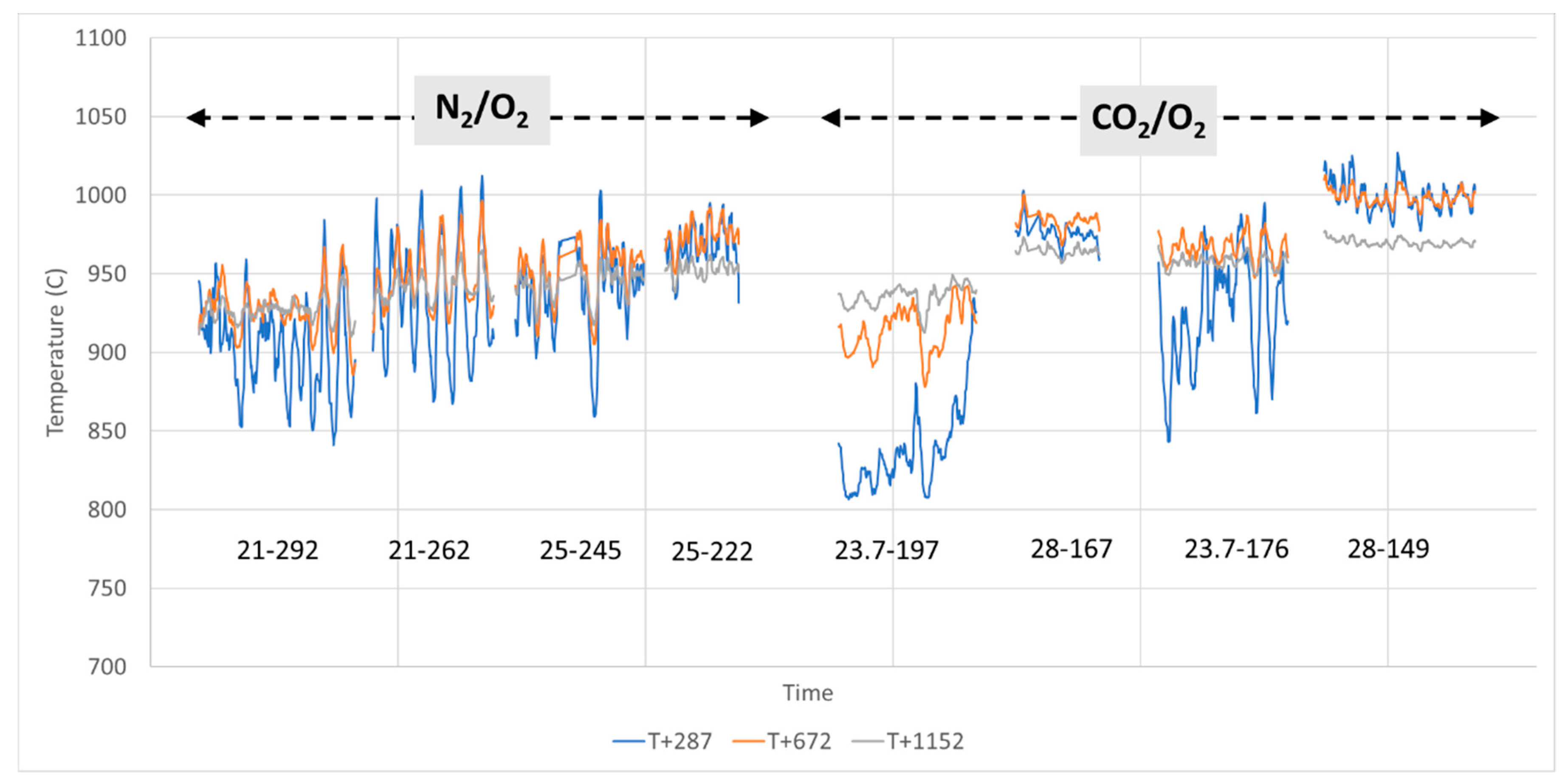

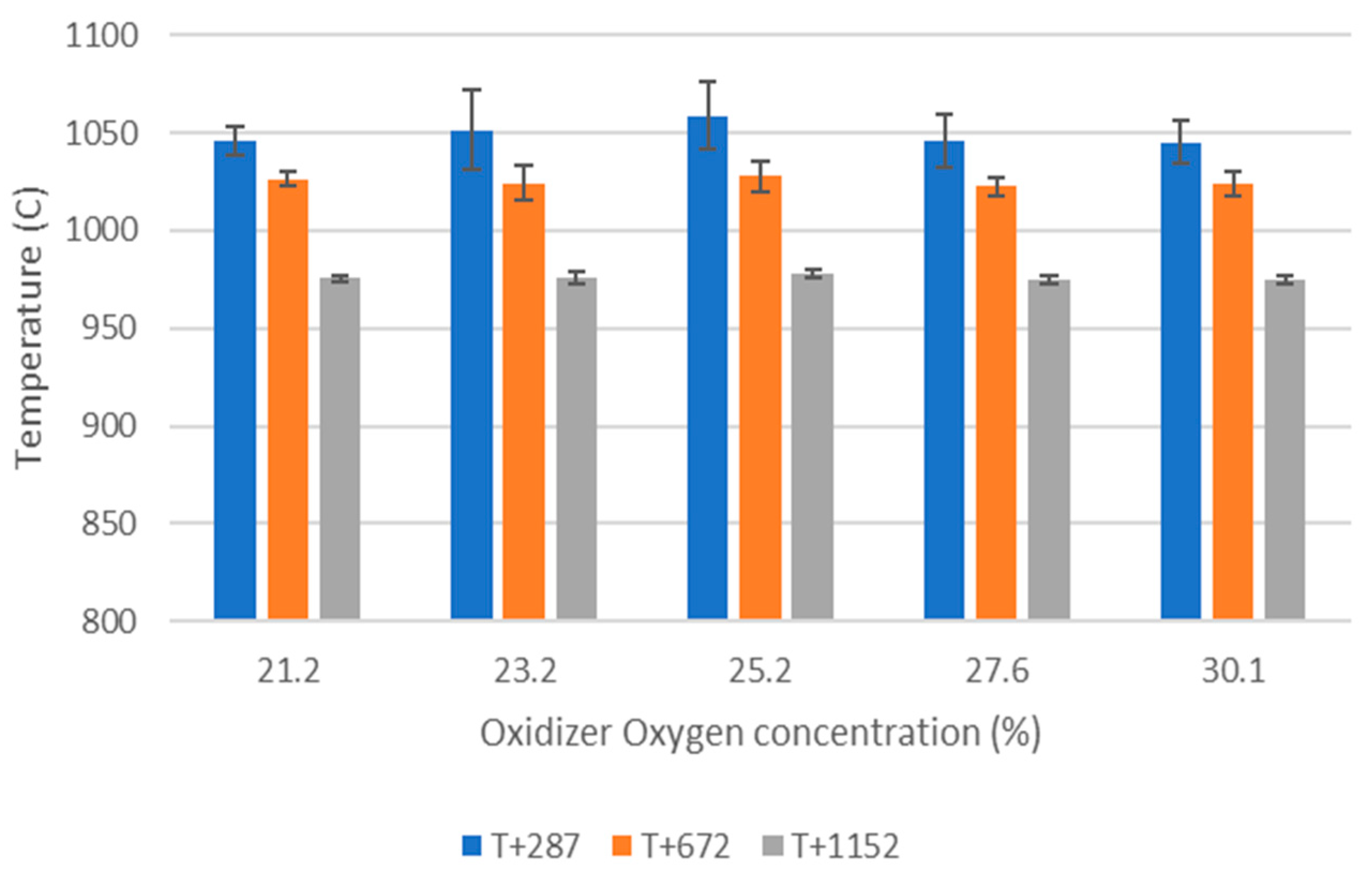

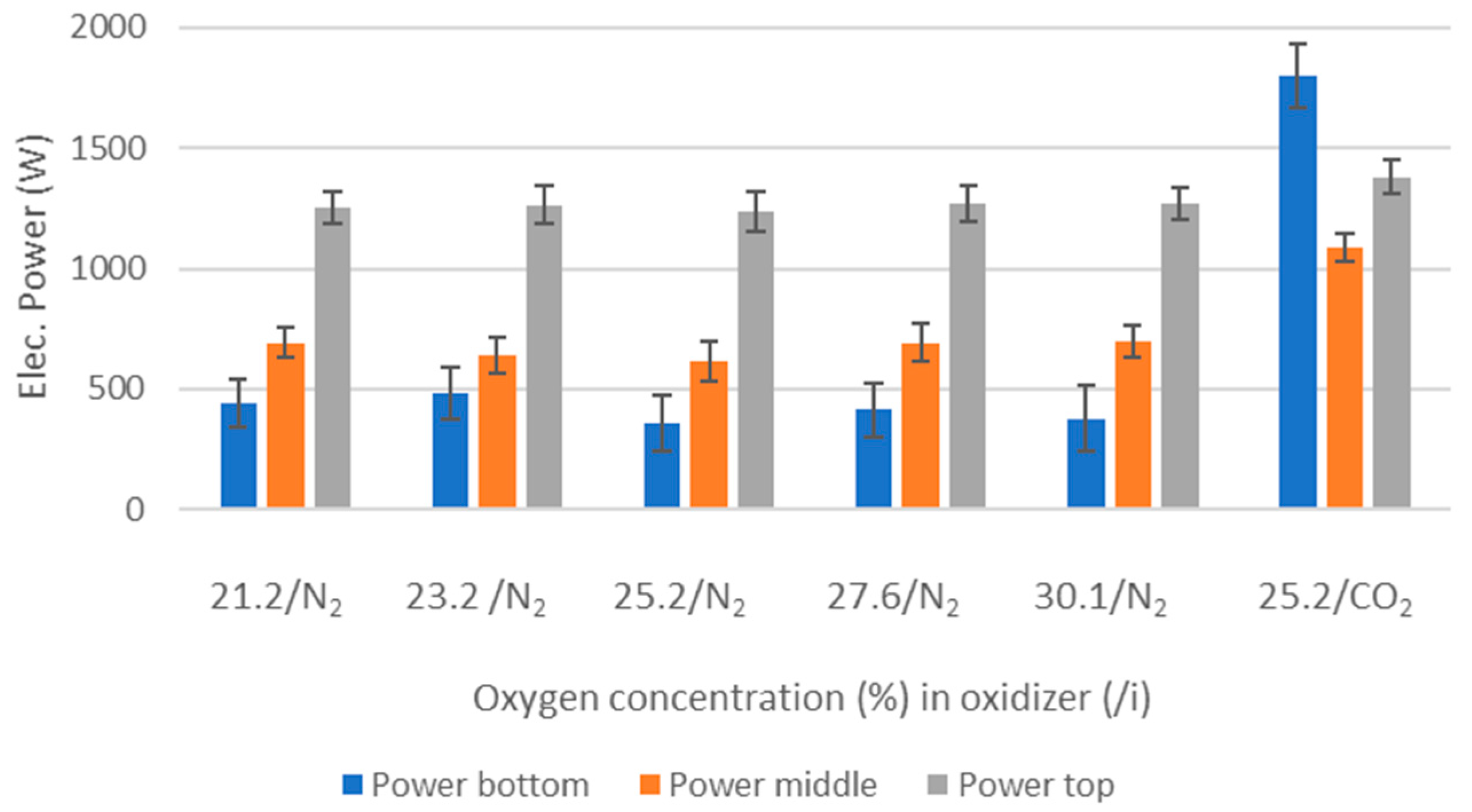

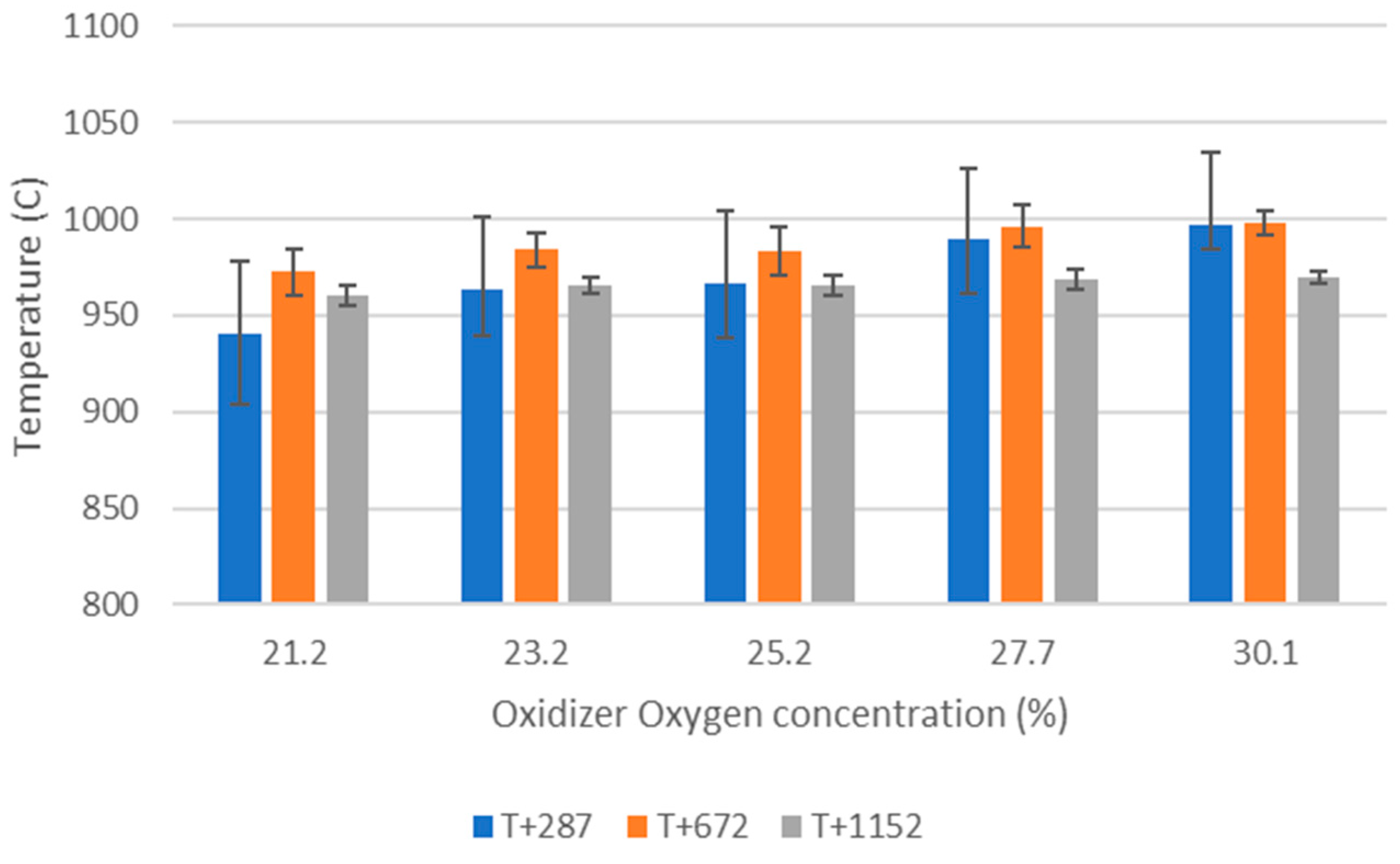

Figure 1 shows the vertical tube furnace (VTF) reactor used in this study. It includes a 2000 mm long, 120 mm inner diameter tube, at the bottom of which a perforated grate is placed. The ceramic tube is surrounded by 3 separate electric heaters and insulation. Three thermocouples (T+287, T+672 and T+1152, the number indicating the distance from the grate in millimeters) placed as shown in the figure allow to monitor the temperature inside the reactor.

The feedstock is introduced from the top using a feeding screw while the oxidizer gas mixture is introduced from the bottom section. The exhaust gas exiting the reactor at the top section is sampled and passed through a heated line to an FTIR analyzer and then after condensation of its water content, to an O2 analyzer. The FTIR analyzer (Gasmet DX-4000) has a 0.4 L volume cell with a 5 m pathlength and an 8 cm−1 resolution. It monitors major and minor species of interest including water vapor and used a factory-set calibration setup specifically designed for high CO2 (up to 85%) and high water vapor (up to 50%) concentrations. Two calibration series are used for CO, one at ppm level and the other at low% level. The O2 analyzer is of paramagnetic type, which has a better accuracy and utilization range than the built-in zirconium cell found in the FTIR instrument.

Up to total gas flow rates of approximately 290 NL/min (at 1000 °C), the reactor flow is laminar. The Reynolds number is approximately 1200–1300 for the gas flow rates of interest in this study (160–170 NL/min). The residence time in the reactor is estimated to be ca. 1.6 s. in the heated and insulated zone for gas flow rates of 150–170 NL/min at 1000 °C. The pressure was measured at the top and the bottom of the reactor tube to detect any blockage. Ash samples are collected at the end of each day. The experimental reproducibility has been investigated and is good.

2.2. Materials/Feedstocks

One feedstock is used in this study: model MSW pellets.

MSW is a complex, changing, heterogeneous mixture made of a variety of materials, i.e., food, paper, plastic, woody, and non-woody biomass, textiles, metal, glass, and more. Each material can be divided into sub-fractions, e.g., the plastic fraction is made of HDPE (high density polyethylene), PVC (polyvinylchloride), PE (polyethylene), PS (polystyrene), etc. In this study, it is deemed essential to have a good control over the fuel properties while realistically portraying the main characteristics of MSW. After careful consideration, the following mixture (or model MSW) was selected: 10 wt% cardboard (packaging box), 40 wt% virgin wood (from wood pellets) and 50 wt% white office paper, with the overall properties listed in

Table 1. The resulting mixture exhibits an elemental composition close to many western-type MSW [

3]. It is a simplified MSW, but correctly reflects the main aspects of MSW, most importantly, moderate energy content (less than 20 MJ/kg) and high ash content (above 5 wt%).

Plastic (less than 10–12 wt% in most EU MSW) was not included due to the risk of melting on the grate that could damage the reactor. Furthermore, increasing material recycling rates will soon reduce its content in MSW going to WtE.

Biodegradable waste (e.g., food) was not included to avoid hygienic issues during storage and handling of the model MSW. However, it is represented by wood in the model MSW. Like plastic, food waste (in the EU) will be increasingly sorted out for separate treatment (or collected separately) to fulfill EU material recovery rates targets.

Metal and glass were not used as they mainly act as heat sinks (even though melting might happen, for example, for aluminium).

The model MSW is prepared by shredding the various constituents to approximately 5–6 mm particles before mixing them thoroughly (including wetting to ease blending and pelletizing) at the pre-defined proportions. The resulting mixture is then pelletized before being dried to approximately 3–5 wt% moisture content.

2.3. Practical Comments on the Set-Up: Feeding System and Changing Operational Conditions

The screw used for fuel feeding had a direct impact on the overall appearance of the emissions trace that exhibited what can be described as small oscillations or variations. The feeding system employed resulted in a kind of “pulsed” (rather than continuous) introduction of pellets, dropping 1–3 at a time before a pause of up to a few seconds depending on the feeding rate. In addition, it was observed that the screw sometime broke pellets while feeding. These phenomena were responsible for minor and random variations but did not have any effect on the validity of the results that are presented as average values. Note that this comment does not apply to large emissions peaks observed when operating conditions are changed and that are due to other processes, e.g., a transient, unstable combustion process.

Furthermore, two distinct events lead to unstable conditions: (a) experiment start-up, as it takes a few minutes for the process to stabilize when feedstock is first introduced, and (b) when changing experimental conditions.

2.4. Method/Procedure and General Comments on the Experiments

The overall procedure of an experiment follows these steps (see

Figure 1):

The reactor is heated overnight and left to stabilize at a given reactor temperature, typically 1000 °C. A moderate flow of air is maintained.

The reactor is operated continuously at a defined fuel effect (i.e., fuel feeding rate), typically 1.3 kg/h, via a screw feeder placed at the top of the VTF furnace.

The oxidizer mixture (air, N2 or CO2 with various O2 concentration) reaches the grate and the feedstock from below (typical total gas flow rate in: 150–300 NL/min).

Temperatures (3 thermocouples are placed inside the reactor (see

Figure 1); pressure difference (between reactor top and bottom) and gas emissions (exiting from the top of the reactor to an FTIR) are measured and recorded continuously.

Each experimental period (time during which all parameters are kept constant) lasts from approx. 45 min to approx. 2 h.

The key parameters and variables in this study (experimental matrix in next section):

Feedstock–model MSW.

Fuel feeding rate–fixed at 1.3 kg/h.

Reactor temperature (electrically controlled)–fixed at 1000 °C.

Oxidizer/gas mass flow rate in—varying or fixed.

O2 concentration—varying from 21 to 30 vol%.

Oxidizer composition—CO2 or N2 together with varying O2 concentrations.

The main experimental results investigated in this study:

The calculated carbon mass balance was satisfying for the experiments, on average 100–120%. Deviations may be due imperfect waste fractions mix in the pellets, varying moisture content (the pellets were not stored under controlled humidity conditions), and analysis limitations, e.g., varying logging time.

The Results and Discussion section provides a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation and comparison with relevant literature, as well as the conclusions that can be drawn from them.

4. Conclusions

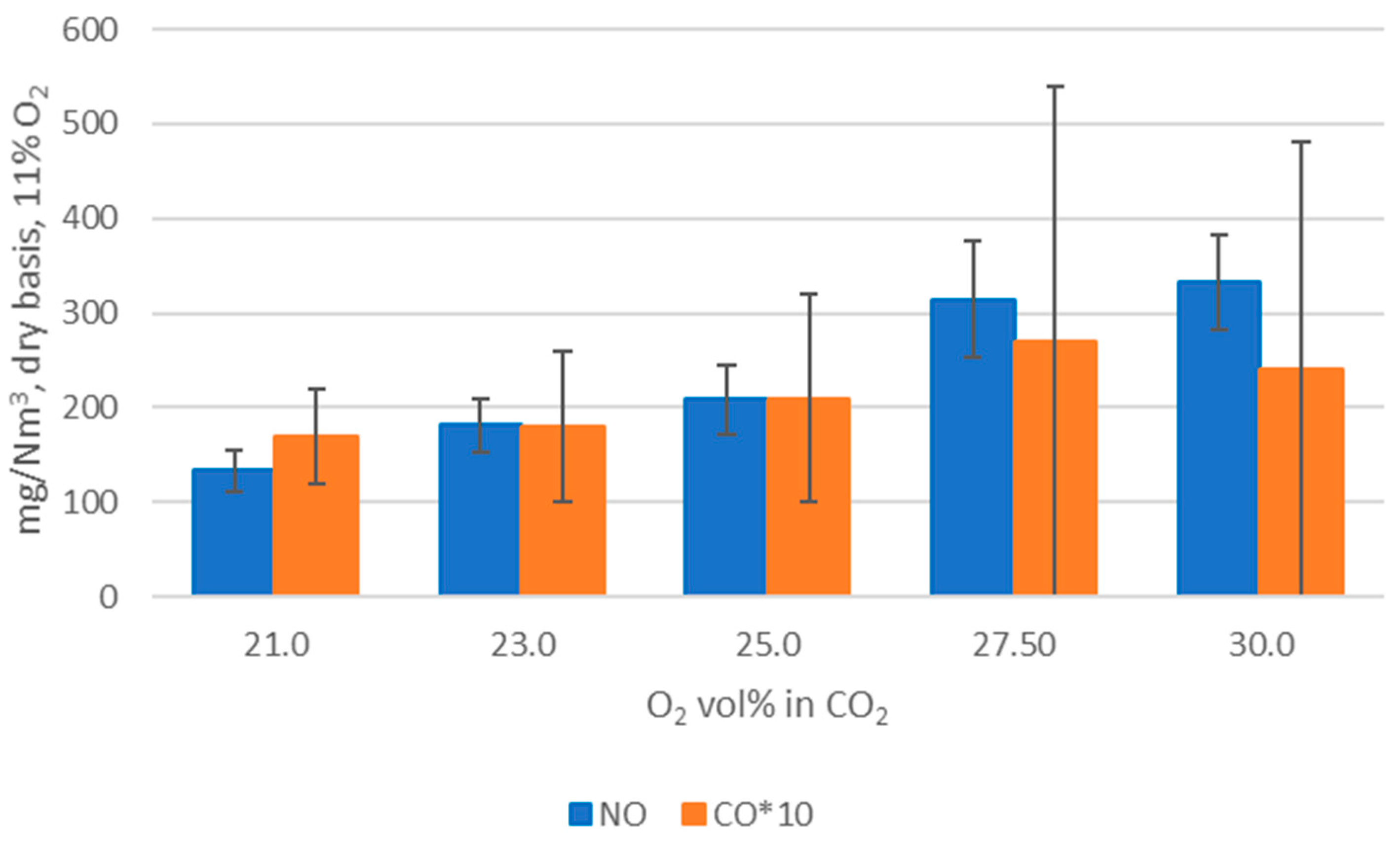

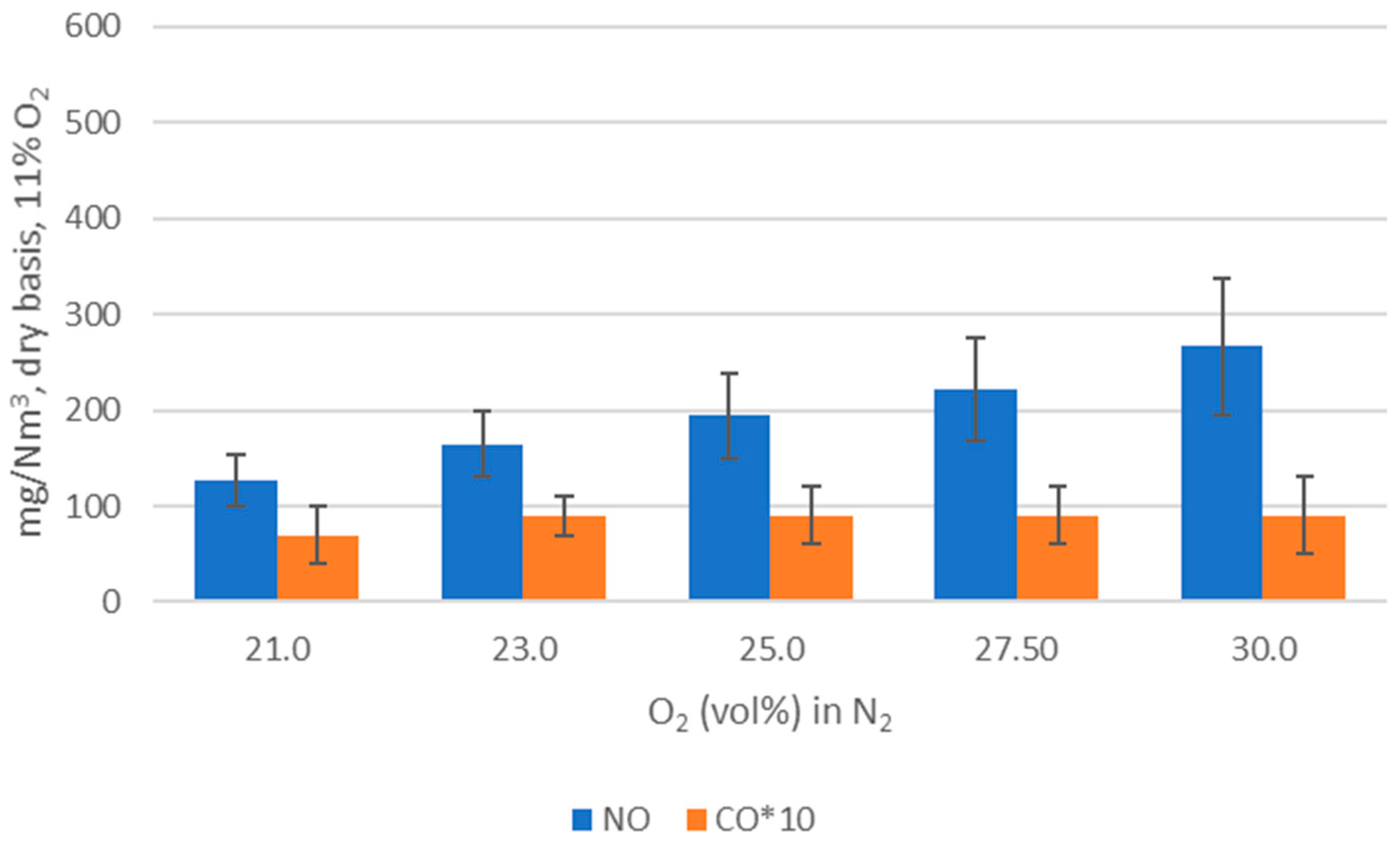

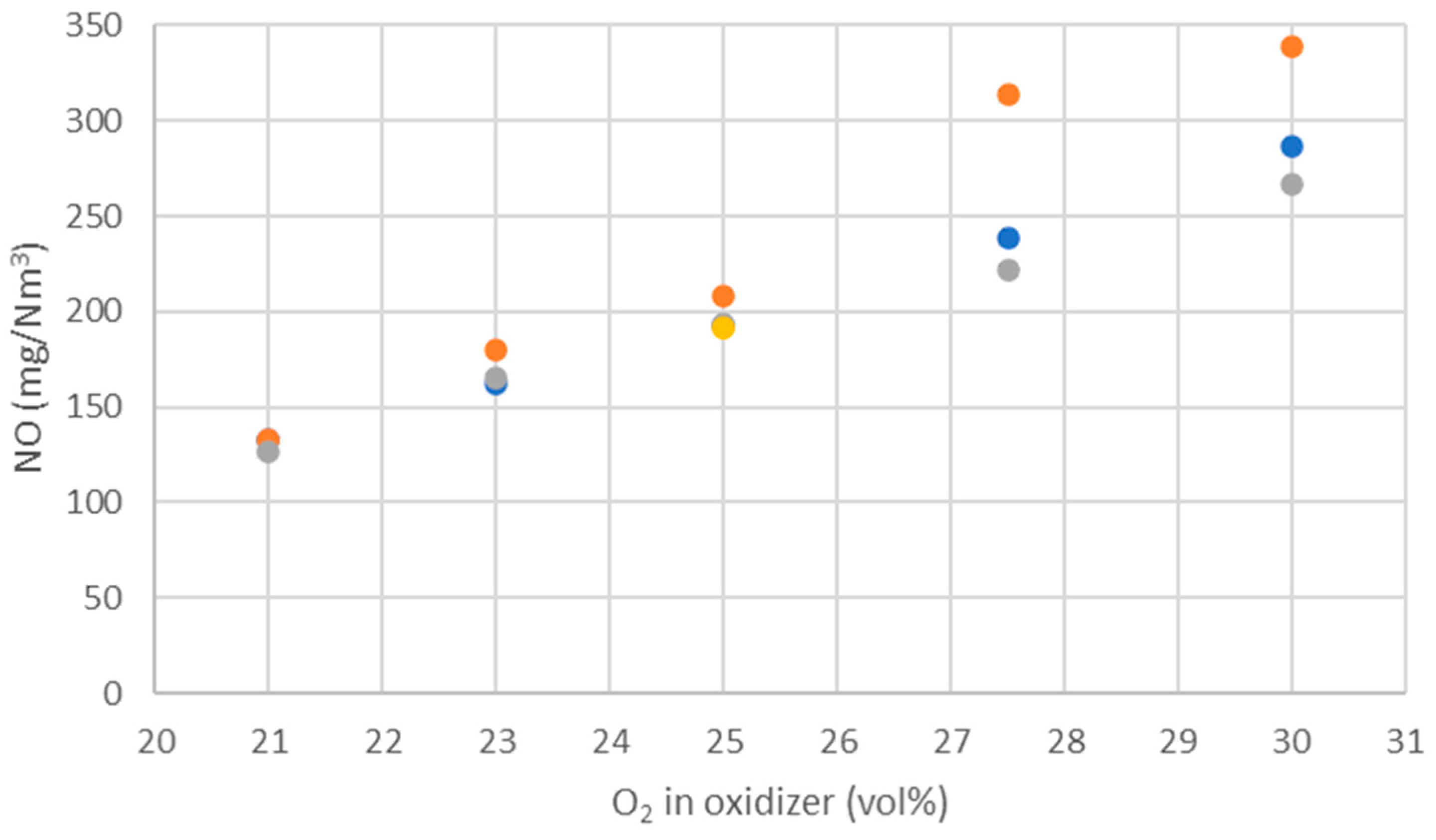

WtE with advanced gas cleaning system destroys contaminants and reduces the weight and volume of mixed waste that cannot be recycled. It also produces mainly renewable energy as MSW is predominantly of biogenic origin. Combined with CCS, WtE would hence offer the potential for carbon negative emissions, a key measure to fight climate change. Several CCS technologies exist or are under development and oxyfuel combustion integrated with CCS has shown to be a promising technology for solid fuels such as coal. The experimental assessment of oxyfuel combustion in a laboratory scale reactor performed and reported in this study shows that a model MSW can satisfactorily be combusted under different oxyfuel conditions provided that the oxygen concentration in the oxidizer is carefully adapted. The results also indicate that there is no unsurmountable showstopper for the further development of MSW oxyfuel combustion. The results in this study contribute to the further development of oxyfuel combustion as they confirm that stable combustion can be attained under different operating oxyfuel conditions, using both N2 and CO2, for a complex mixture. Stable combustion with high CO2 concentrations (in the range of 78–87 vol% in the flue gas) was attained even though CO2’s higher heat capacity (compared with N2) impacts the combustion process negatively. Working at these conditions will greatly facilitate the implementation of CO2 capture. The results also indicate that NOx emissions will be increasing with O availability, a trend observed both with N2 and CO2.

The aforementioned challenges can be addressed, e.g., with adequate combustion chamber design, appropriate local O2 concentrations, advanced recirculated flue gas strategy (amount, temperature, wet/dry, raw/clean), and primary and secondary measures for NOx. Further oxyfuel combustion development should be considered in the perspective of a system building upon air-fired grate combustion technology with combustion temperatures below 1200 °C to benefit from the existing know-how while avoiding excessive material costs. This is especially important to be able to handle untreated, mixed, unrecyclable waste.

Further studies should advance further oxyfuel combustion and include experiments with higher O2 concentrations, (bottom and fly) ash analysis, other waste mixtures, kinetics, different reactor temperatures, study of local conditions, and the effects of heterogeneity, temperature measurements in a waste bed under oxyfuel conditions, advanced oxidizer supply strategies, and optical study to observe the combustion process in situ.