Abstract

The article presents the results of the application of an original methodology for designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance in accordance with the principles of sustainable development. The methodology was verified using a computational example involving the selection of a compromise solution for a single-family residential building with a positive energy balance located in Warsaw, Poland. Three different models of decision-makers’ preferences were created, taking into account selected decision sub-criteria. Three technical solutions were identified, permissible according to the principles and guidelines for designing buildings with a positive energy balance. As a result of the performed calculations, the final order of the analyzed variants was obtained, from the most preferred to the least accepted solution. Variant 2 is definitely the most advantageous solution, being the best in a group of 20 to 26 evaluation sub-criteria—depending on the adopted model of the decision-maker’s preferences. Its ranking index Ri ranged from 0.773 to 0.764, while for the other variants it was much lower and varied from 0.258 to 0.268 for variant 1, and from 0.208 to 0.226 for variant 3. The methodology used for the case study proved to be applicable. The developed methodology facilitates the process of designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance, which is an extremely complex process.

1. Introduction

Environment-friendly and human-friendly construction takes into account the prevention of excessive depletion of the natural environment by saving its resources, including fossil fuels, as well as preventing its pollution. The increase in the welfare of the society occurs synergistically with the protection of the natural environment when harmony is maintained. An important characteristic of the idea of sustainable development is its multidimensionality, i.e., such development of the basic elements of the system shaping the future of the human community, that is, the environment, society and economy, that none of them poses a threat to the others. There is no doubt that commercial buildings have an impact on the above-mentioned elements. The built environment is responsible for around 30–40% of the world’s total primary energy use. Therefore, it has a high reduction potential that can be used to improve the energy performance of individual buildings [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

Increasing importance is attached to methods improving the efficiency of the use of fossil fuels or replacing their use with renewable energy carriers. The synergy of these actions for housing industry may contribute to a decrease in the share of households in the final primary energy consumption, and thus to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions to the natural environment, which is consistent with the idea of sustainable development.

In order to counteract climate change, it is necessary to introduce changes in the process of designing residential buildings by:

- reducing the demand for heat, cooling and electricity, which is influenced by the shape, structure and energy profile of the building and its technical equipment,

- using unconventional and renewable energy sources,

- increasing the efficiency of systems used to ensure climate comfort in the building,

- increasing the efficiency of energy conversion by household appliances,

- enabling bidirectional energy flow in any of its forms,

- taking maximum advantage of natural (passive) support strategies for heating, cooling and using natural light.

The preparation of a construction project is essentially a decision-making process and therefore requires creative thinking. Nowadays, there are many computer tools available to support the design project, for example, drawing programs such as AutoCAD, 3D modeling tools—SketchUp, simulation software—EnergyPlus, TRNSYS, DOE-2, PHPP, i.e., computational programs simulating energy consumption [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

The traditional process of designing residential buildings based only on the relationship or cooperation between the architect and the investor is changing due to a number of different parameters and criteria. The group of participants in the construction process is growing. The architect is joined by industry designers (installer, electrician, constructor), as well as consultants, specialists in their profession, such as interior designer or energy advisor. The architect—as the main coordinator of the project—collects information on the client’s expectations regarding the concept of the building, its shape, form, equipment and functional and spatial layout; knows the limitations, the local climate, proposes an appropriate location and position of the building in the area. At this stage, the architect should have knowledge of the impact of the selection of individual solutions on investment and operating costs, energy consumption and meeting the required climatic comfort in the indoor environment. In these areas, an analyst/consultant can provide support. In the implementation phase of the investment, problems between the investor, designer, contractor and user can be avoided at an early stage. The role of the analyst is to illustrate to the decision-maker (most often the investor), the architect and other participants of the construction process how individual changes to the building, e.g., the structure (compact/wide body) or the use of appropriate construction and material solutions will affect certain decision-making criteria, including initial costs, operating costs, user comfort or utility and primary energy consumption. Thanks to such analyses, created as early as the concept stage and then at the stage of adopted solutions preferred by the decision-maker, a well-considered, coherent design vision of the building is created, meeting all the previously established evaluation criteria [9,10,11,12].

There is no doubt that when designing energy-efficient buildings, and especially residential buildings with a positive energy balance, an interdisciplinary approach combining the investor’s guidelines, the architect’s vision, the competence of engineers and the work of an analyst, whose role is to help in choosing a compromise solution, becomes necessary.

2. Materials and Methods

Paper [16,17] presents an original methodology for designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance, consistent with the principles of sustainable development. In the present paper, a decision was made to test it on a computational example involving the selection of a compromise solution for a single-family residential building with a positive energy balance. Three different models were included of decision-makers’ preferences (“Current/future user”, “Designer/Architect” and “All decision makers”) including a selection of decision sub-criteria. Three technical solutions were identified, permissible according to the principles and guidelines for designing buildings with a positive energy balance. It should be emphasized that all of the adopted variants of solutions meet the guidelines of the passive house standard according to the Passive House Institute (PHI)—the Passive House Plus (PH Plus) standard [13,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. The methodology consists of five steps. The first is the construction of an input database for a specific project, the second is the identification of permissible and acceptable solutions. The third stage is the creation of a set of decision criteria and identification of the relation between them, which is determined by surveying a group of experts using the Delphi method. The fourth stage consists in determining the preferences of the decision-maker with the use of a target group survey utilizing social research. An algorithm completes the fifth stage, in which the values of the variables are calculated and normalized, and a ranking of permissible and acceptable variants of solutions is created, concluded with the choice of a compromise solution.

3. Applied Methodology and Results

3.1. STAGE 1—Creating the Input Database for a Specific Project

The creation of the input database was carried out in accordance with the basic principles of designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance. To select a set of permissible and acceptable solutions, the following input database was adopted:

- (a)

- a building with a usable area of approx. 200 m2, inhabited by a family of three (2 adults and 1 child),

- (b)

- passive house standard—PH Plus, in accordance with Passive House Institute (PHI),

- (c)

- location and climate—the city of Warsaw, south-oriented building,

- (d)

- location in unprotected terrain—no natural shade,

- (e)

- simple architectural and spatial form,

- (f)

- standard manner and profile of use of a residential building,

- (g)

- strict requirements for climatic comfort—a building equipped with active heating, cooling, lighting and mechanical balanced ventilation systems with high-efficiency heat recovery (≥75%)

- (h)

- restrictions resulting from Polish regulations, in line with, e.g., the Regulation of the Minister of Infrastructure and Construction on technical conditions to be met by buildings and their location,

- (i)

- maximum integration with the external environment, e.g., by using natural resources,

- (j)

- building completion time—maximum 5 years,

- (k)

- maximum investment costs of PLN 1.5 million,

- (l)

- the range of values of characteristics (from minimum to maximum) that describe the decision criteria from the set of evaluation criteria and sub-criteria.

The input database can be freely modified in the first stage of the methodology. The level of detail of the input database depends on the analyst or decision-maker and the time spent on the analysis.

3.2. STAGE 2—Identification of Permissible and Acceptable Solutions for a Residential Building with a Positive Energy Balance

Three technical solutions were identified that are permissible and acceptable according to the created input database and meet the previously imposed requirements, guidelines and limitations.

3.2.1. Variant No. 1

The building is designed in framing technology with the use of an I-beam as the basic structural element filled with wood wool that serves as thermal and acoustic insulation. The roof is made of wooden I-beams filled with wood wool. The building is founded on a foundation slab insulated with extruded polystyrene with an integrated heating and cooling system supplied from a Split-system air-to-water heat pump. The first floor of the building is heated and cooled with the use of capillary mats connected to the central heating and cooling system. Preparation of domestic hot water from the central heat source, i.e., an air-to-water heat pump with a domestic hot water tank with a capacity of 300 L. The building is equipped with a mechanical balanced ventilation system with high-efficiency heat recovery. On the south side of the roof of the building, there is a photovoltaic installation using polycrystalline panels (39 units) with a total power of 9.75 kWp. The building design of the House with a winter garden was prepared by Pasywny m2 design studio, a private investor.

3.2.2. Variant No. 2

The building is designed in traditional technology, with the use of silicate bricks with reinforced concrete as a supporting structural element, external walls covered with graphite polystyrene for thermal and acoustic insulation. The roof is made of I-beams filled with wood wool. The building is founded on a foundation slab insulated with extruded polystyrene with an integrated heating and cooling system supplied from a glycol-water heat pump with a lower heat source in the form of a vertical exchanger (3 vertical tubes). The first floor of the building is heated and cooled with the use of a thermally active ceiling connected to the central heating and cooling system. Preparation of hot domestic water from the central heat source, i.e., a glycol-water heat pump with a domestic hot water tank with a capacity of 300 L. The building is equipped with a mechanical balanced ventilation system with high-efficiency heat recovery integrated with the lower heat source of the heat pump through an air-to-water heat exchanger (pre-heater/cooler), acting as a ground heat exchanger (GHE) for heating the exhaust air in winter and cooling it in summer. On the roof of the building, on the south side, there is a photovoltaic installation using polycrystalline panels (36 units) with a total power of 9.36 kWp. The building design of the Solar house was prepared by Pasywny m2 design studio, a private investor.

3.2.3. Variant No. 3

The building is designed in framing technology with the use of an I-beam as the basic structural element filled with wood wool that serves as thermal and acoustic insulation. The roof is made of wooden I-beams filled with wood wool. The building is founded on a foundation slab insulated with extruded polystyrene. It is heated and cooled with the use of a Multi Split heating and cooling air-conditioning system with one outdoor unit and five indoor wall-mounted units. The direct electric floor-heating installation serves as a peak heat source. Preparation of domestic hot water from an individual heat source, i.e., a domestic hot water heat pump with a capacity of 270 L, integrated with the mechanical ventilation system, from which it extracts heat from the exhaust air during the heating season, and from the supply air during the cooling season. The domestic hot water installation recovers heat from gray water in showers. The building is equipped with a mechanical balanced ventilation system with high-efficiency heat recovery, integrated with the domestic hot water installation. On the south side of the roof of the building, there is a photovoltaic installation using monocrystalline panels (33 units) with a total power of 9.735 kWp. The building design of the House with a mezzanine was prepared by Pasywny m2 design studio, a private investor.

The basic parameters of the selected variants of single-family residential buildings with a positive energy balance are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic parameters for the variants of single-family residential buildings with positive energy balance.

Architectural visualizations of the analyzed single-family residential buildings with a positive energy balance are presented in Supplementary A.

The results of the energy balance calculations for the analyzed single-family residential buildings were carried out in PHPP—version 9.6b, exergy balances were calculated in Annex 49 Pre-Design Tool.

3.3. STAGE 3—Selection of a Set of Decision Criteria and Identification of the Relations between the Criteria

The decision criteria for the selection of a residential building with a positive energy balance were described and selected in a dissertation [16]. In turn, in accordance with the proposed methodology and using the DEMATEL method, the relation between individual main criteria and sub-criteria of evaluation should be determined. For that purpose, research was conducted in accordance with the concept of the Delphi method. The study is described in detail in [17]. The evaluating body is a group of experts surveyed using an original expert questionnaire. The prepared questionnaire was sent to experts in the field of architecture and urban planning, construction, environmental engineering or energy. The selection of the group of respondents for the study was intended and strictly defined—it consisted of specialists employed in scientific units, research units and those operating in business, who should be considered experts due to their interests, knowledge and expertise.

The conducted research ended with determining the weights of the relations between individual criteria and sub-criteria. At this stage, it is possible to select specific evaluation criteria, rejecting those of exclusively effect character and/or minor importance for the choice of a compromise solution. The analyst and/or decision-maker may also decide to allow the specified sub-criteria of evaluation. Table 2 lists the criteria and sub-criteria of evaluation along with the values of the calculated relation weights.

Table 2.

Selected decision criteria for choosing a single-family residential building with a positive energy balance together with the relation weights.

The decision criteria with the highest level of relationship weights are use of natural heating, cooling and lighting strategies (NST) and Shape factor (A/V). The decision criteria with a high level of relationship weights are: Total usable energy consumption (UETOTAL), Sum of exergy generated by renewable energy sources (BGEN,RES), Utilization of the generated renewable energy (UTILRES) and Total final energy consumption (FETOTAL). The decision criteria with the lowest level of relationship weights are compliance with the acoustic comfort parameters (AC), Compliance with the visual comfort parameters (VC) and Total service life of renewable energy installation (TRES).

After carrying out the analysis performed with the DEMATEL method, it is possible to characterize in detail the relations or their absence, between the main criteria and the sub-criteria for the process of designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance. All relationships between the various criteria and sub-criteria should be taken into account. The advantage of the method used is that it is transparent in reflecting the interrelationship between a wide set of elements. The analyst—on the basis of the assessments expressed by the experts in the response—may submit his comments on the effects (direction and significance) between the factors. On the basis of the analysis performed, the analyst may remove from the set of criteria/sub-criteria those that show a strong effect character, which means that they are also influenced by other criteria/sub-criteria. The same criteria/sub-criteria can also remain in the set of evaluation criteria/sub-criteria, providing added value for the decision-maker (wider set of decision-making criteria) so that the decision-maker is aware that all factors (features) influencing the design process of residential buildings with a positive energy balance have been considered. Due to a computational example, it was decided to keep all evaluation criteria and sub-criteria.

3.4. STAGE 4—Determination of the Profile of the Decision-Maker’s Preferences

After selecting an acceptable set of decision criteria, proceed to stage 4 of the methodology for designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance, i.e., the determination of the profile of the decision-maker’s preferences. It is prepared using a social research method, i.e., a target group survey. A statistical measurement of a representative population should be performed, answers should be obtained and a statistical analysis should be carried out. The study is described in detail in a dissertation [16].

After analyzing the collected data, the target profile of the decision-maker’s preferences was created using the AHP/ANP method, which includes assigning direct weights to the previously selected decision criteria and sub-criteria. The data used to create the preferences of the decision-maker were obtained by means of previously conducted social research, namely a target group survey. A statistical measurement of the represented group was performed (22 respondents—“Current/Future user” group, 17 respondents—“Designer/Architect” group, and 53 respondents in the “All decision-makers” group). For the analyzed groups of decision-makers, Table 3 presents the weights for the main evaluation criteria, whereas Table 4 shows the weights for individual evaluation sub-criteria. All presented weights were calculated using the AHP/ANP method.

Table 3.

Weight vectors for the main evaluation criteria—“Current/Future user” and “Designer/Architect”.

Table 4.

Weight vectors for all evaluation sub-criteria—“Current/Future user” and “Designer/Architect”.

Table 5 lists the preference weights normalized as part of a whole for all evaluation sub-criteria for groups of decision-makers “Current/Future user” and “Designer/Architect”, as well as comparatively for the group “All decision-makers”.

Table 5.

Normalized weights of preferences for all evaluation sub-criteria-“Current/Future user”, “Designer/Architect” and “All decision-makers”.

The level of significance of the decision criteria depends on the group of decision makers. For the group “All decision makers” the most significant criterions are: Total prime cost of the investment (TCINV), Analysis of the building’s life-cycle cost (LCC) and Total usable energy consumption (UETOTAL). The least important criteria are compliance with the visual comfort parameters (VC) and Impact of the building and its installations on the surrounding environment (IENV). For the group “Current/Future user” the most significant criterions are: Total generated usable renewable energy (UERES), Analysis of the building’s life-cycle cost (LCC) and Total prime cost of the investment (TCINV). The least important criteria are compliance with the visual comfort parameters (VC) and Impact of the building and its installations on the surrounding environment (IENV). For the group “Designer/Architect” the most significant criterions are: Total usable energy consumption (UETOTAL), Use of natural heating, cooling and lighting strategies (NST), Total prime cost of the investment (TCINV) and Total generated usable renewable energy (UERES). The least important criteria are compliance with the visual comfort parameters (VC), Impact of the building and its installations on the surrounding environment (IENV) and Compliance with the acoustic comfort parameters (AC). Due to a computational example, it was decided to keep all evaluation criteria and sub-criteria.

If the created profile is acceptable, proceed to stage five of the methodology, otherwise you have to conduct another survey or expand or narrow the target group. There are no grounds for rejecting the created profile of preferences for the selected target groups. In line with the above, move on to step 5 of the proposed methodology.

3.5. STAGE 5—Choosing the Compromise Solution

The last stage of the proposed methodology for designing residential buildings with positive energy balance begins with the calculation of target weights for the decision criteria, which are based on the previously obtained relation weights and decision-makers’ priorities. Table 6 compiles the target preference weights for all evaluation sub-criteria for the “Current/Future user” and “Designer/Architect” groups of decision-makers, and comparatively for the group “All decision-makers”.

Table 6.

Target weights for all evaluation sub-criteria—“Current/Future user”, “Designer/Architect” and “All decision makers”.

In turn, the values of the variables characterizing individual variants of permissible solutions should be calculated alongside providing preferences characterizing a given indicator. This is how a decision matrix used in the TOPSIS method is created, which is the first step. The calculations were made in accordance with the formulas and relations of the TOPSIS method. The data for the calculations and their results are presented in Supplementary B, while Table 7 presents the numerical values of the calculated indicators along with the preferences for selected evaluation sub-criteria.

Table 7.

Numerical values of indicators and their preferences for selected sub-criteria of evaluation.

Table 8 presents the maximum permissible numerical values of the indicators along with a reference to the formula that should be used when calculating a given indicator for selected sub-criteria of evaluation.

Table 8.

Permissible numerical values of indicators for selected evaluation sub-criteria.

The obtained numerical values of the indicators (see Table 7) are then normalized, which is the second step when using the TOPSIS method. After normalization, all indicators are stimulants (see Table 9).

Table 9.

Normalized values of indicators for selected evaluation sub-criteria.

The next step (according to the TOPSIS method) is to multiply the obtained values after normalization (see Table 9) by the target weights of the evaluation criteria (see Table 6), thus obtaining evaluations adjusted for each variant. Due to the fact that all adjusted evaluations are stimulants, the positive-ideal solution for each of the evaluation criteria is the variant with the maximum value of the adjusted evaluation, while the negative-ideal solution will be the variant with the minimum value (according to the TOPSIS method—step 4). The adjusted evaluations and the indication of the positive-ideal and negative-ideal solutions are included in Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12. Each of the tables refers to a different group of decision-makers.

Table 10.

Adjusted evaluations of the sub-criteria of evaluation for individual variants—the “All decision makers” group.

Table 11.

Adjusted evaluations of the sub-criteria of evaluation for individual variants—the “Current/Future user” group.

Table 12.

Adjusted evaluations of the sub-criteria of evaluation for individual variants—the “Designer/Architect” group.

According to the TOPSIS method, to create the final ranking of variants in descending order, in step 5 of the method, calculate the distance of each variant from the positive-ideal and negative-ideal solution, and then calculate the index of similarity of individual variants to the positive-ideal solution. The distances and the ranking index for all permissible variants and for 3 groups of decision-makers are summarized in Table 13.

Table 13.

Positive-ideal and negative-ideal solutions for individual groups of decision-makers, distances of the analyzed variants from the positive-ideal and negative-ideal solutions, and ranking factors.

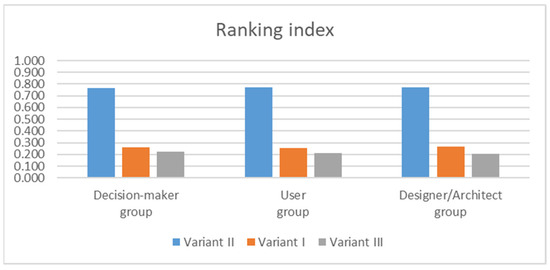

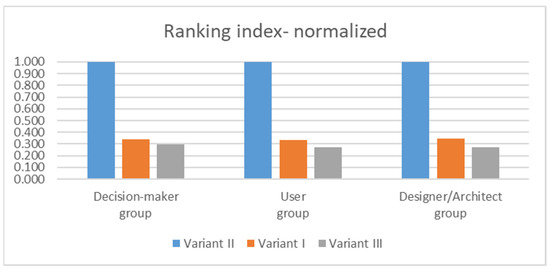

The final ranking in descending order was presented in Table 14 and in Figure 1. The final normalized ranking in descending order was presented in Table 15 and in Figure 2.

Table 14.

Final ranking of variants.

Figure 1.

Final ranking of variants.

Table 15.

Final ranking of variants—normalized.

Figure 2.

Final ranking of variants—normalized.

4. Discussion

The most compromise solution for a single-family residential building with a positive energy balance is the construction of the building in accordance with variant no. 2 for the created input database. The same result was obtained for all three groups of decision-makers, with slight differences in value between the groups resulting from different preferences of decision-makers. The other two variants are definitely worse solutions according to the multi-criteria analysis carried out, and they are at a similar level in terms of evaluation.

The solution consistent with variant no. 2 in an overwhelming number of decision criteria was the ideal solution, according to the TOPSIS method, for 26 sub-criteria in the group “Decision maker”, for 23 sub-criteria in the group “Current/Future user”, and for 20 sub-criteria in the group “Designer/Architect”, with respect to 30 sub-criteria of evaluation. Its ranking index Ri ranged from 0.773 to 0.764, while for the other variants it was much lower and varied from 0.258 to 0.268 for variant 1, and from 0.208 to 0.226 for variant 3. The compromise solution was by far the best in many evaluation sub-criteria, especially in: Analysis of the building’s life-cycle cost (LCC), Utilization of the generated renewable energy (UTILRES), Dynamic generation cost of renewable energy installation (DGCRES), Carbon Dioxide Emission Index (ECO2), Total usable energy consumption (UETOTAL), Total final energy consumption (FETOTAL), Total service life of the building (TLIFE), Coherence of renewable energy sources (CRES). However, the compromise solution turned out to be the most distant from the positive-ideal solution for several evaluation sub-criteria, including Total prime cost of the investment (TCINV) and Shape factor (A/V). The use of the proposed methodology for designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance allows the analyst and the decision-maker to perform a detailed analysis of the selection of a compromise variant from a group of possible solutions, taking into account the adopted models of the decision-maker’s preferences and the decision criteria selected for analysis, and to objectively select the most-compromise solution.

5. Conclusions

The applicability of the proposed methodology was verified by using it in the selected case study. As a result of the performed calculations, the final order of the analyzed variants was obtained, from the most preferred to the least accepted solution. The methodology used for the case study proved to be applicable. Using the presented methodology, it is possible to determine the evaluation criteria with a strong causal character, which, to the greatest extent, affect the other evaluation criteria. These criteria illustrate the primary factors to focus on for designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance. They are prioritized and further improvement potential must be sought within them. It should be noted that the subject of the analysis were only single-family residential buildings. The applicability of the presented methodology can be extended to include other types of objects. For this purpose, statistical surveys of the target group (decisionmakers) should be re-conducted. The selected group of decision sub-criteria can be modified by introducing additional or changing the existing sub-criteria. The research carried out by the Delphi method (survey by a team of experts) is unified and can also be used for other types of buildings. The profile of preferences of the decision maker should be individually adjusted for other types of building and taking into account other entities, local conditions and priorities. The developed methodology facilitates the process of designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance, which is an extremely complex process. It may be used by an individual investor, developers, city authorities, public utility entities, private sector entities and other target groups.

The proposed methodology is universal, has an open set of evaluation criteria and can be applied anywhere in the world. It may be helpful at the stage of verification of competition works undertaken in public tenders in order to select the most advantageously designed facility.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en14165162/s1. Supplementary A: Visualizations of the analyzed single-family residential buildings. Supplementary B: Calculation of the values of variables, i.e., the values of decision criteria for individual variants of permissible solutions for single-family residential buildings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R. and T.M.; methodology, B.R.; formal analysis, B.R.; investigation, B.R.; resources, B.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R.; writing—review and editing, T.M.; visualization, B.R.; supervision, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was funded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, research subsidy number SBAD/0948/2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This work is based on the results of Bartosz Radomski Ph.D. thesis entitled “The methodology of designing residential buildings with a positive energy balance” (original title: “Metodyka projektowania budynków mieszkalnych o dodatnim bilansie energetycznym” under the supervision of Tomasz Mroz.). The data presented in this study are openly available in https://sin.put.poznan.pl/files/download/35489, accessed on 10 July 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kabak, M.; Köse, E.; Kırılmaz, O.; Burmaoglu, S. A fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making approach to assess building energy performance. Energy Build. 2014, 72, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepbasli, A. Low exergy (LowEx) heating and cooling systems for sustainable buildings and societies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonski, M.; Schrag, T. Linear Optimisation of a Settlement Towards the Energy-Plus House Standard. Energies 2019, 12, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ciancio, V.; Falasca, S.; Golasi, I.; de Wilde, P.; Coppi, M.; de Santoli, L.; Salata, F. Resilience of a Building to Future Climate Conditions in Three European Cities. Energies 2019, 12, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rucińska, J.; Trząski, A. Measurements and Simulation Study of Daylight Availability and Its Impact on the Heating, Cooling and Lighting Energy Demand in an Educational Building. Energies 2020, 13, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berouine, A.; Ouladsine, R.; Bakhouya, M.; Essaaidi, M. Towards a Real-Time Predictive Management Approach of Indoor Air Quality in Energy-Efficient Buildings. Energies 2020, 13, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygierek, K.; Ferdyn-Grygierek, J.; Gumińska, A.; Baran, Ł.; Barwa, M.; Czerw, K.; Gowik, P.; Makselan, K.; Potyka, K.; Psikuta, A. Energy and Environmental Analysis of Single-Family Houses Located in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampelis, N.; Sifakis, N.; Kolokotsa, D.; Gobakis, K.; Kalaitzakis, K.; Isidori, D.; Cristalli, C. HVAC Optimization Genetic Algorithm for Industrial Near-Zero-Energy Building Demand Response. Energies 2019, 12, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, X.; Tian, Z.; Chen, W.; Si, B.; Jin, X. A review on building energy efficient design optimization from the perspective of architects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Loosemore, H. The multi-criterion optimization of building thermal design and control. Building Simulation. In Proceedings of the Seventh International IBPSA Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 13–15 August 2001; pp. 873–880. [Google Scholar]

- Caldas, L.; Norford, L.K. Genetic Algorithms for Optimization of Building Envelopes and the Design and Control of HVAC Systems. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2003, 125, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dytczak, M. Wybrane Metody Rozwiązywania Wielokryterialnego Problemów Decyzyjnych w Budownictwie; Oficyna Wydaw Politech Opolskiej: Opole, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Passive House Institute (PHI). Passive House Planning Package, Energy Balance and Passive House Design Tool for Quality Approved Passive Houses and EnerPHit Retrofits; Version 9; PHI: Darmstadt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedmohammadreza, H.; Wahid, M.; Hamed, H.S. Assessing the Energy and Indoor Air Quality Performance for a Three-Story Building Using an Integrated Model, Part One: The Need for Integration. Energies 2019, 12, 4775. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid, F.; Fayaz, M.; Aljarbouh, A.; Mir, M.; Aamir, M. Imran Energy Consumption Optimization and User Comfort Maximization in Smart Buildings Using a Hybrid of the Firefly and Genetic Algorithms. Energies 2020, 13, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomski, B. The Methodology of Designing Residential Buildings with a Positive Energy Balance (Original Title: Metodyka Projektowania Budynków Mieszkalnych o Dodatnim Bilansie Energetycznym). Ph.D. Thesis, Poznań University of Technology, Faculty of Environmental and Power Engineering, Poznań, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Radomski, B.; Mróz, T. The Methodology for Designing Residential Buildings with a Positive Energy Balance—General Approach. Energies 2021, 14, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.passiv.de/ (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Passive House Institute (PHI). Criteria for the Passive House, EnerPHit and PHI Low Energy Building Standard; Version 9f; Passive Passive House Institute (PHI): Darmstadt, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Radomski, B. Projektowanie instalacji sanitarnych w budynkach pasywnych—studium przypadku. Inżynier Budownictwa 2016, 9, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Radomski, B. Projektowanie w budynkach pasywnych instalacji ziębniczej, przygotowania ciepłej wody użytkowej i wentylacji mechanicznej nawiewno-wywiewnej. Inżynier Budownictwa 2016, 11, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Radomski, B.; Bandurski, K.; Mróz, T.M. Rola parametrów komfortu klimatycznego w budynkach pasywnych. Instal 2017, 10, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Firląg, S. Cost-Optimal Plus Energy Building in a Cold Climate. Energies 2019, 12, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mróz, T.M.; Radomski, B. Aspekty energetyczne współczesnego środowiska zabudowanego. Przegląd Bud. 2018, 7–8, 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Erhorn, H. The Age of Positive Energy Buildings Has Come; Franhofer Institute for Building Physics: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012; pp. 1433–1443. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).