A Review of Behavioral Energy Reduction Programs and Implementation of a Pilot Peer-to-Peer Led Behavioral Energy Reduction Program for a Low-Income Neighborhood

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Energy Poverty

2.2. Values and Motivation of Energy Consumption

2.3. Peer-to-Peer Education

3. Case

3.1. Case Study Overview: Pilot Peer-to-Peer Energy Reduction Program

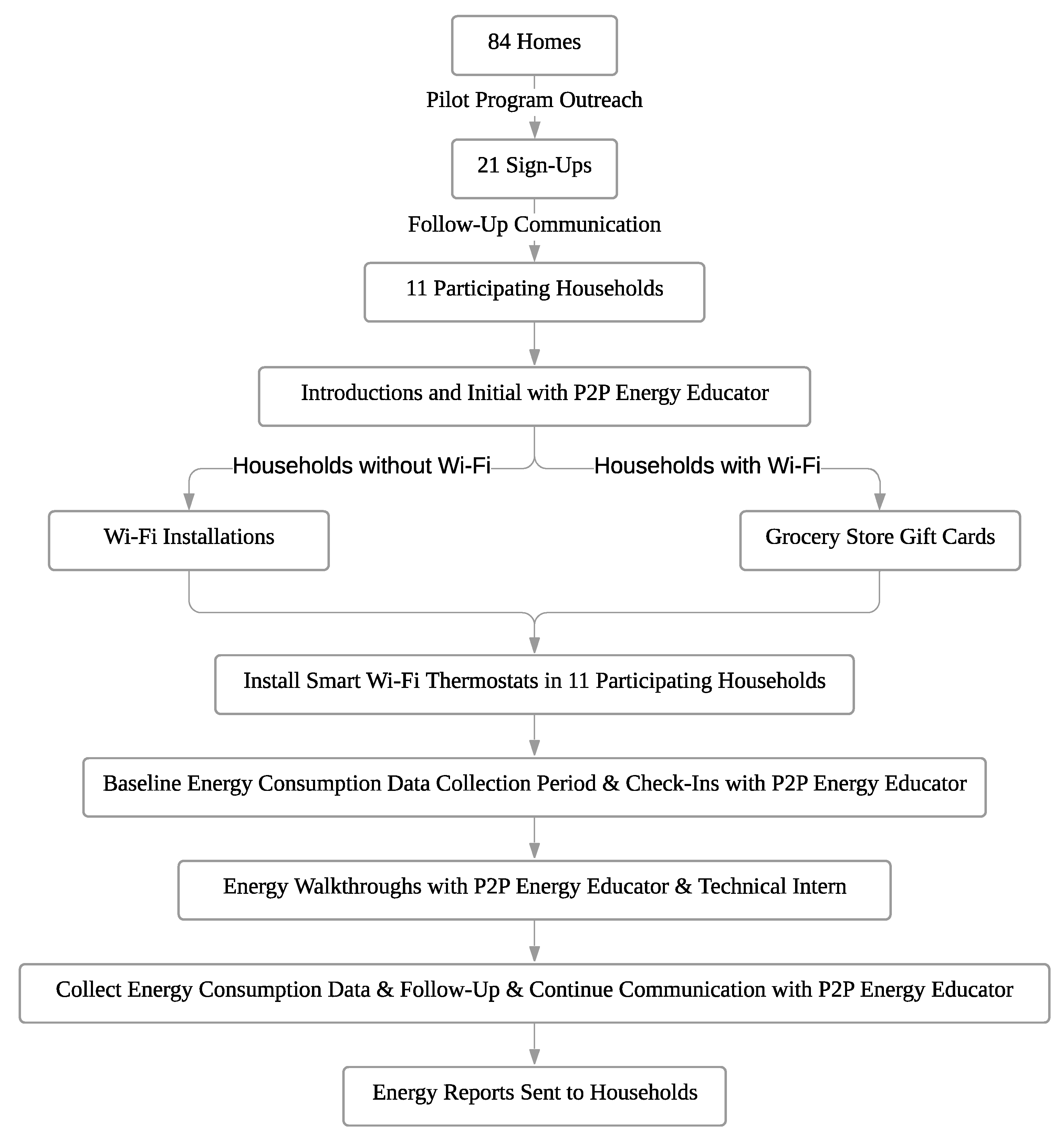

3.2. Pilot Program

3.3. Program Status at Completion of Pilot Program

4. Methods

4.1. Participant Survey

4.2. Interviews

4.3. Tracking Energy Consumption and Measurement of Savings

5. Results

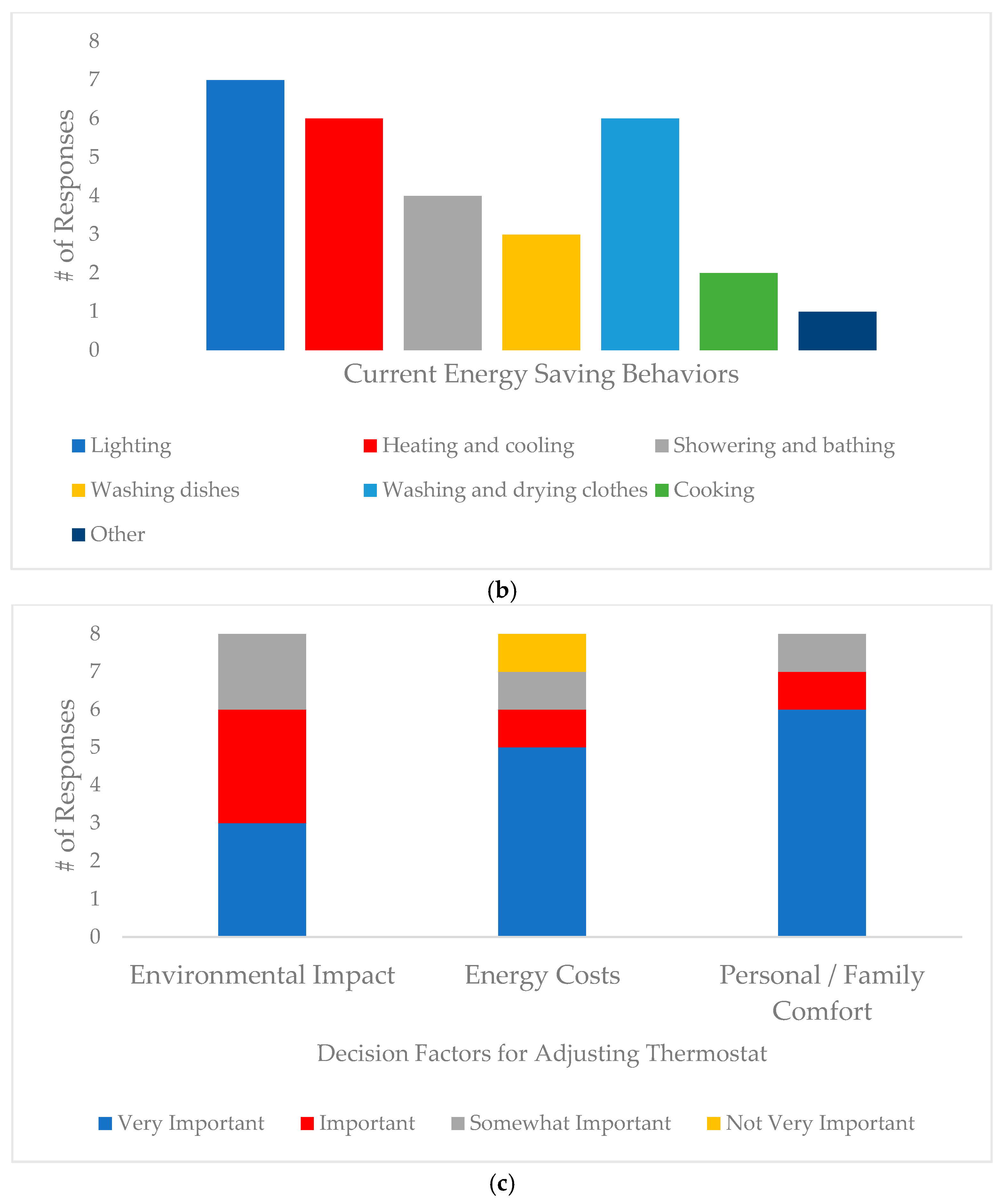

5.1. Participant Survey

5.2. Interviews

5.2.1. Community Empowerment and Sense of Control

5.2.2. Education and Training

5.2.3. Program Impact and Reach

5.2.4. Program Requirements and Logistics

5.2.5. Program as Integrative and Collaborative

5.3. Preliminary Home Energy Usage Result

6. Discussion and Improved Program Design

6.1. Maximizing Program Impact

6.2. Understanding Program Reach

6.3. P2P Energy Educator

6.4. Additional Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C—Summary for Policymakers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/ (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- U.S. Energy-Related Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 2019. Energy Information Administration. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/environment/emissions/carbon/ (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Pellegrini-Masini, G.; Pirni, A.; Maran, S. Energy justice revisited: A critical review on the philosophical and political origins of equality. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 59, 101310:1–101310:7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Hernández, D.; Geronimus, A.T. Energy efficiency as energy justice: Addressing racial inequities through investments in people and places. Energy Effic. 2020, 13, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Dworkin, M.H. Energy justice: Conceptual insights and practical applications. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simcock, N.; Frankowski, J.; Bouzarovski, S. Rendered invisible: Institutional misrecognition and the reproduction of energy poverty. Geoforum 2021, 124, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S. A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: Overcoming the energy poverty–fuel poverty binary. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS): 2015 RECS Survey Data. Energy Information Administration. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2015/ (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Bednar, D.J.; Reames, T.G. Recognition of and response to energy poverty in the United States. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drehobl, A.; Ross, L.; Roxana, A. How High Are Household Energy Burdens? American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. Available online: https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/u2006.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Getting Energy Efficiency to the People Who Need It Most. Governing: The Future of States and Localities. Available online: https://www.governing.com/gov-institute/voices/col-cities-energy-efficiency-low-moderate-income-households.html (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Ouyang, J.; Hokao, K. Energy-saving potential by improving occupants’ behavior in urban residential sector in Hangzhou City, China. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Su, T.D.; Bui, T.D.; Dang, V.T.B.; Nguyen, B.Q. Financial development and energy poverty: Global evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 35188–35225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Energy Outlook 2018. International Energy Agency. 2018. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/77ecf96c-5f4b-4d0d-9d93-d81b938217cb/World_Energy_Outlook_2018.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Analysis of the Voluntary National Reviews Relating to Sustainable Development Goal 7: 2018. United Nations. 2018. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/258321159DESASDG7_VNR_Analysis2018_final.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Energy Access Outlook 2017: From Poverty to Prosperity. International Energy Agency. 2017. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/9a67c2fc-b605-4994-8eb5-29a0ac219499/WEO2017SpecialReport_EnergyAccessOutlook.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Jessel, S.; Sawyer, S.; Hernández, D. Energy, Poverty, and Health in Climate Change: A Comprehensive Review of an Emerging Literature. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 357:1–357:19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Office of Community Services: LIHEAP Fact Sheet. Administration for Children & Families: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ocs/resource/liheap-fact-sheet-0 (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Weatherization Assistance Program. Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/wap/weatherization-assistance-program (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Roth, J.; Hall, N. Assessment of LIHEAP and WAP Program Participation and the Effects on Wisconsin’s Low-Income Population: An Examination of Program Effects on Arrearage Levels and Payment Patterns. ACEEE Summer Study Energy Effic. Build. 2006, 7-226–7-238. Available online: https://www.aceee.org/files/proceedings/2006/data/papers/SS06_Panel7_Paper19.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Normative, Gain and Hedonic Goal Frames Guiding Environmental Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Values, Environmental Concern, and Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.; Sunstein, C. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grilli, G.; Curtis, J. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours: A review of methods and approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110039:1–110039:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Establishing a Peer Education Program. The University of Kansas: Community Tool Box. Available online: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/implement/improving-services/peer-education/main (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Ten Cate, O.; Durning, S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med. Teach. 2007, 29, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M.L.; Ghorob, A.; Hessler, D.; Yamamoto, R.; Thom, D.H.; Bodenheimer, T. Are Low-Income Peer Health Coaches Able to Master and Utilize Evidence-Based Health Coaching? Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, S36–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thorn, D.H.; Ghorob, A.; Hessler, D.; De Vore, D.; Chen, E.; Bodenheimer, T.A. Impact of Peer Health Coaching on Glycemic Control in Low-Income Patients with Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Marshak, H.H.; de Silva, P.; Silberstein, J. Evaluation of a Peer-Taught Nutrition Education Program for Low-Income Parents. J. Nutr. Educ. 1998, 30, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuso, R. Low-Income Pregnant Mothers’ Experiences of a Peer-Professional Social Support Intervention. J. Community Health Nurs. 2003, 20, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twin Towers Neighborhood in Dayton, Ohio (OH), 45410 Detailed Profile. City-Data. Available online: https://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Twin-Towers-Dayton-OH.html (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Prototype—Twin Towers, East Dayton, Ohio. CleanEnergy4All. Available online: https://cleanenergy4all.org/project/twin-towers-neighborhood/ (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Housing and Economic Development. East End Community Services. Available online: https://www.east-end.org/housing-and-economic-development (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Noar, S. Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change in Health and Risk Messaging. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. 2017. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-324 (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stenner, K.; Hobman, E.V. The Socio-Demographic and Psychological Predictors of Residential Energy Consumption: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2015, 8, 573–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrus, G.; Passafaro, P.; Bonnes, M. Emotions, habits and rational choices in ecological behaviours: The case of recycling and use of public transportation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Data Online. National Centers for Environmental Information. Available online: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/ (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Al Tarhuni, B.; Naji, A.; Broderick, P.G.; Hallinan, K.P.; Brecha, R.J. Large Scale Residential Energy Efficiency Prioritization Enabled by Machine Learning. Energy Effic. 2019, 12, 2055–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanezi, A.; Hallinan, K.P.; Huang, K. Automated Residential Energy Audits Using a SmartWiFi Thermostat-Enabled Data Mining Approach. Energies 2021, 14, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Dayton Electricity Rates. Electricity Local. Available online: https://www.electricitylocal.com/states/ohio/dayton/#ref (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Greenhouse Gases Equivalencies Calculator—Calculations and References. Environmental Protection Agency. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gases-equivalencies-calculator-calculations-and-references (accessed on 2 March 2021).

| Program Details | Description |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood Location | Twin Towers neighborhood in Dayton, Ohio |

| Financial support | Ohio Housing Finance Authority |

| Residence type | Low-income rent-to-purchase housing |

| Neighborhood median income | $32,542 [33] |

| Average household size | 7.8 People [33] |

| Neighborhood racial demographics | White, Black, Asian, Hispanic or Latino, two or more races, American Indian [33] |

| Participants racial demographics | Black, White |

| P2P energy educator racial demographics | White |

| Program developers’ racial demographics | White |

| Position | Description (Roles, Responsibilities, and Contributions) |

|---|---|

| P2P Energy Educator | Responsible for interactions with residents and was the point of contact between the participating households and the rest of the program; served as a mentor and peer to the residents and provided education on energy saving behaviors and tools; responsible for relationship building with residents; established initial communication with households who signed up for the program; scheduled meetings for thermostat installations, energy walkthroughs, and all other interactions; assisted with thermostat installation; and maintained regular communication with residents to follow-up on meetings and address questions. |

| Technical Intern | Worked closely with the P2P energy educator interacting with households but with a greater focus and background on the technical aspects of energy savings; assisted with initial outreach and thermostat installations; created preparatory materials and documents for household interactions and energy walkthroughs; and kept track of technical related issues and concerns from interactions. |

| Nonprofit Director | Focused on determining and navigating the role of the energy reduction program within the overall purpose of the nonprofit; sought to create partnerships and make connections with other community organizations to further the work of the program; primary fund-raiser for the non-profit; and managed the budget. |

| Program Innovator and Energy Analyst | Collected historical energy data on residences, identifying the opportunity to realize behavior-based savings; responsible for the ideation of the program with the intent to build capacity within the neighborhood; introduced and proposed this program to the nonprofit director and was the primary figure in the development of the program and the early stages of partnership development; worked with utilities to collect energy data for participating residences; and responsible for the measurement of savings realized for each residence and collectively. |

| Program Coordinator | Community partner who worked for the nonprofit, managing numerous programs and initiatives; began working with the program near the end of implementation of the pilot program and transitioned into the role of overseeing the program; restructured the program and prepared for a new P2P energy educator after the initial pilot program; and focused on story development of the nonprofit and program to increase presence and awareness within the neighborhood. |

| House | Energy (kWh) | Cost ($) 1 | CO2 (Metric Ton) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −191 | −$22.52 | −0.14 |

| 2 | −327 | −$38.55 | −0.23 |

| 3 | 156 | $18.39 | 0.11 |

| 4 | −489 | −$57.65 | −0.35 |

| 5 | 216 | $25.47 | 0.15 |

| 6 | 1002 | $118.14 | 0.71 |

| 7 | −65 | −$7.66 | −0.05 |

| 8 | −950 | −$112.01 | −0.67 |

| Average | −81 | −$9.55 | −0.06 |

| Total | −648 | −$76.40 | −0.46 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoody, J.; Galli Robertson, A.; Richard, S.; Frankowski, C.; Hallinan, K.; Owens, C.; Pohl, B. A Review of Behavioral Energy Reduction Programs and Implementation of a Pilot Peer-to-Peer Led Behavioral Energy Reduction Program for a Low-Income Neighborhood. Energies 2021, 14, 4635. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14154635

Hoody J, Galli Robertson A, Richard S, Frankowski C, Hallinan K, Owens C, Pohl B. A Review of Behavioral Energy Reduction Programs and Implementation of a Pilot Peer-to-Peer Led Behavioral Energy Reduction Program for a Low-Income Neighborhood. Energies. 2021; 14(15):4635. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14154635

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoody, Jennifer, Anya Galli Robertson, Sarah Richard, Claire Frankowski, Kevin Hallinan, Ciara Owens, and Bob Pohl. 2021. "A Review of Behavioral Energy Reduction Programs and Implementation of a Pilot Peer-to-Peer Led Behavioral Energy Reduction Program for a Low-Income Neighborhood" Energies 14, no. 15: 4635. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14154635

APA StyleHoody, J., Galli Robertson, A., Richard, S., Frankowski, C., Hallinan, K., Owens, C., & Pohl, B. (2021). A Review of Behavioral Energy Reduction Programs and Implementation of a Pilot Peer-to-Peer Led Behavioral Energy Reduction Program for a Low-Income Neighborhood. Energies, 14(15), 4635. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14154635