1. Introduction

The purpose of setting up companies, regardless of the form of organization, is to make a profit within an organized framework by making expenses which then generate revenue. The result of economic activity, determined as a difference between revenue and expenditure, has generated discussions and various research on the decisive role of management in profit-making.

Is it the sole purpose of the management of the economic entity? For efficient activity, the management team will aim to reduce spending and maximize revenues. Looking from the account of commitments, revenue does not automatically mean receipts, nor does expenditure automatically involve payments made. This increasingly asks the question: is the result of the economic activity in the entity’s cash flow?

From the financial accounting point of view, the operating cash flow represents the cash generated from the daily activities of a business, or in other words, the positive cash flow available from the basic operations of a trading company. The operating cash flow indicates when a company may need external financing or if it generates enough cash flow and does not need external financing to maintain current operations.

At the same time, compared to the conventional ways of measuring profitability such as net income, and the fact that the activity of trading companies is characterized by the totality of fixed assets such as machines and equipment that can reduce the net income as a result of the impairment, the operating cash flow can be a measure of the profitability of the operating activity [

1] Thus, the operating cash flow of a company provides a more appropriate picture of current cash holdings than the artificially reduced net income with the reversible and irreversible impairment adjustments, because the latter are expenses calculated and not paid, so it is not reflected in cash. The operating cash flow is a financial accounting indicator, component of earnings, being equal to earnings minus non-cash earnings (also called accruals) [

2].

We can say that the operating cash flow and earnings have the same information content, this statement being validated by the research of several specialists through the analysis of companies listed on various capital markets [

3,

4,

5].

In respect to the relationship between the earnings management and the free cash flow, the field’s literature shows that those companies that have a generous free cash flow tend to increase their earnings [

6].

Although important, the determination of a cash flow is not a voluntary action by economic entities, the task of drawing up this situation is applicable only to those entities meeting the size criteria set for this purpose [

7,

8]. This aspect was a brake on a wider investigation; the situation of energy companies can be found in Romania only in the case of companies listed on BVB, the regulated market sector.

In this article, we focused our attention on the companies from the Romanian energy sector listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange, because they are large, profitable companies with high liquidity, which are preferred by Romanian and foreign investors, most of them being controlled by the Romanian state through its direct participations. We were attracted to the energy sector because of the impact that its expansion has on the evolution of economies around the world and because of its dynamics in the sense of gradually shifting to the use of energy from renewable sources.

On the Romanian energy market (wholesale) there are about 10 operators/carriers in the natural gas sector (among OMV Petrom S.A., SNTGN Transgaz S.A. and S.N.G.N. Romgaz S.A.), respectively, and approx. 15 electricity producers/carriers (including CNTEE Transelectrica, Societatea Energetica Electrica S.A., SN Nuclearelectrica S.A., S.C. OMV Petrom S.A.). The Romanian State, through the Ministry of Energy, holds the stakes in these important companies operating on the energy market. In some companies, it has a majority stake so far (S.N.G.N. Romgaz S.A., SNTGN Transgaz S.A., SN Nuclearelectrica S.A., C.N.T.E.E. Transelectrica, CONPET SA), in some the participation of the Romanian state is a minority (S.C. OMV Petrom SA, Societatea Energetica Electrica S.A, Romeptrol Rafinare SA) [

9].

The liberalization of the electricity and natural gas market of Romania, started in 2012 in accordance with Directive 2012/27/EU reformed by the EU Directive 2019/944, was a long and complex process that ended on 31 December 2020. Thus, starting with 2021, in Romania the energy system operates on the basis of free market mechanisms, which must lead to competitive energy markets to an integration of markets for the transition to a cleaner production of electricity and natural gas, the ultimate goal being the sale of low carbon energy [

10].

Due to the removal of state restrictions and the liberalization of the electricity and gas markets, new research opportunities have emerged as the electricity and gas can now be sold and traded on several stock markets, each with its own specificity [

11]. In Romania, energy is traded on the Romanian Commodities Exchange.

The companies in the energy field analyzed by us are included in the BET-NG index basket, which reflect the share prices evolution of energy companies that are traded on a regulated market such as the B.S.E. The maximum weight of a company in the index basket is 30, 28%, currently owned by OMV Petrom SA. The BET-NG index had a similar evolution to that of the BET index following the trend of the Romanian economy, having a crash in 2011 and 2012, followed by a slight increase since 2013. During 2015, the index had decreased by 14.02% due to lower prices of goods, especially oil. In the present, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the value of the BET-NG index has decreased by 166 points, canceling the increases registered in the last 3 years [

12]

Being controlled by the Romanian state, these companies are considered safe investments by investors; they give very good returns and generous dividends compared to other companies listed on the Romanian capital market.

The purpose of our research is to analyze the operating cash flow and profitability indicators and the determination of a causal or dependency relationship with labor productivity or managements rates in case of the companies from the energy sector listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. In this respect, we issue two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. The operating cash flow and profitability indicators are directly correlated with the labor productivity and management rates.

Hypothesis 2. The operating cash flow and profitability indicators are significantly influenced by the management rates but are not influenced in any way by the labor productivity.

To test these assumptions, we start from the study of the related literature and the mentioning of reference works for the theme of our research, followed by the presentation of the research methodology and data used. In the main section of our study, we first describe the analyzed variables, including their time characteristics. Afterwards, we verify the hypothesized relationships and present the related results. The last section, that of the conclusions, foreshadows the response to the assumptions and the recommendations following the research carried out.

2. Literature Review

In his paper, Dayong Zhang [

13] briefly presents the following concepts: energy finance, energy and financial markets, energy corporate finance, green finance and investment, energy derivative markets and last developments on the energy market. The interdisciplinary concept of energy finance is defined as the connection between energy markets and financial markets and requires the analysis of energy and companies operating in this sector from a financial point of view.

In recent years, more and more researchers are focused on understanding the financing of energy companies and investment decisions in companies from this sector.

The dependence or relationship between the profit and cash flow generated multiple and diverse research. Performance analysis based solely on the information provided by the profit and loss account is not sufficient if it is not correlated with the economic entity’s ability to generate cash or cash equivalents [

14].

In their paper, H. Akono and E. T. Nwaeze [

2] analyzed the relevance of the use of the operating cash flow as a measure of performance, conditioned by the importance of working capital managements, in the CEO’s contracts of the companies. They used a compensation regression and the results suggest that firms include measures of the operating cash flow in contracts largely to provide incentives.

The relationship between the cash flow and firm performance has been studied and analyzed over time in both developed and developing countries [

15,

16,

17]. However, the results show both a negative relationship, between the cash flow and firm performance, as well as a positive one [

14]. Bingilar and Oyadenghan [

18] examined in their study the relationship between the cash flow and corporate performance for six companies in the food and beverage sector. Data collection was conducted from the annual reports of the companies and was statistically analyzed using the multiple regression technique. According to the results, between the operating and financing cash flows and corporate performance there is a significant positive relationship, and between the investing cash flow and corporate performance there is a significant negative relationship.

In their paper, Muhammad and Aminatu [

17] examined the impact of the operating cash flow on the financial performance of companies, in the case of five listed conglomerate companies for a period of 10 years. To determine the variation of financial performance, they used regression techniques, descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. The results showed a positive and significant impact between the cash flow from operational activities and the financial performance represented by the ROA, and a positive and significant impact when the financial performance was represented by the ROE.

Farshadfara and Monem [

19] applied to the financial data of the companies, listed on the Australian Stock Exchange, the ordinary least squares regression models. The research was conducted for the period 1992–2004 and the results showed that in the case of profitable companies, the components of the cash flow contribute significantly to the predictive ability of earnings.

S. F. Orpurt and Y. Zang [

20] investigated the informational value of the direct method of calculating the operating cash flow. Using future models to predict cash flows and earnings, the authors concluded that the direct method is better to investors because it more accurately estimates companies’ future profits or cash flows.

Amah, et al. [

16] examined in 2016 the relationship between the cash flow and the performance of four banks listed on the Nigerian Stock Exchange. The analyzed data were collected from the annual report on the banks’ accounts and using the correlation method, and found a significant and strong positive relationship between the operating cash flow and the performance of the analyzed banks, and a negative and weak relationship between the investing cash flow and financial cash flow on the one hand, and the performance of banks on the other.

The relationship between the cash flow and the financial performance was examined by the authors Sunday and Babatunde [

15] on the twenty-seven insurance companies listed on the Nigerian Stock Exchange. The results showed that, for the period 2009–2014, the cash flow was statistically significant to determine the financial performance of insurance companies. During the period under review, it was highlighted that the operating cash flow is directly and significantly related to the financial performance of companies. The results also showed that the cash flow from financing activities does not significantly influence financial performance.

The authors Justyna Franc-Dabrowska, et al. [

21] analyzed the weighted average cost of capital for a group of companies from the energy sector listed on the European Stock Exchanges, from the point of view of the investors and the market risk. In their research, the authors point out that equity financing is two times more expensive than debt financing and shows the negative correlation between the cost of capital and the future cash flow of the company.

In Romania, the issue of cash flows was studied by Găban [

22], analyzing small and medium enterprises for the period 2006–2014. The author identifies in the field of financial analysis the importance of the cash flow based on financial reports. The results show that, in terms of current business financing, investment financing or decisions without a constant pursuit of cash flows, management decisions can be erroneous.

Sabău-Popa Diana, Boloș M. and Bradea I. [

23] analyzed the correlation between capital structure and the performance in case of BSE listed companies that belong to the energy sector. The results of this study emphasize a significant negative correlation between leverage and performance. Most of the companies analyzed by these authors present a low level of debt and a very good level of financial stability rate. They interpreted these results as a strong point of these companies.

In their paper, I. Pervan, J. Arneric and M. Malcak [

4], tested the information content of earnings and the operating cash flow in the context of investors’ decisions on the Zagreb Stock Exchange. Using the GARCH models on the financial accounting data of the 10 companies that are within the CROBEX10 index, the authors show that both performance measures—earnings and the operating cash flow—have high information content.

3. Data and Methodology

A panel of 8 energy companies that belong to the BET-NG index was constructed for a period of 8 years (2011–2018). Data were gathered from the financial statements of the companies, publicly available on the Bucharest Stock Exchange website and were processed by the authors of this paper.

Analyses were conducted in Tableau 2020.1.0, SPSS 26, STATA 15 and Eviews 7. The variables used in the analysis are presented in

Table 1.

The most relevant variables for measuring the profitability of companies are return on assets (ROA) which reflects the net income returned as a percentage of the shareholders’ equity, and return on equity (ROE) which shows how effective a firm management is using its assets to generate income [

23,

24].

The average labor productivity was calculated by dividing the annual turnover by the average number of employees. This indicator reflects the efficiency with which the work of the employees of the company in question is spent.

The average duration of inventory turnover reflects the number of days required for the renewal of stocks. It is an indicator of influence for the operating cash flow because it takes into account all types of stocks [

25].

The average duration of payment of the suppliers and the average duration of the receivables are influential indicators for the operating cash flow of the companies, but more relevant is the difference between them, which, if positive, leads to a favorable situation for the company, meaning that it receives the money from customers in a shorter period than the one in which it pays suppliers [

26].

Following the analyses step, the normality was evaluated and all the variables underwent transformation procedures, on the one hand to reduce skewness in data and, on the other, to allow for interpretation in terms of growth rates.

The first step was the descriptive analysis of the evaluated variables (see

Table 2 and

Figure 1 in the Results Section).

Additionally, the time features of the data were assessed, namely autocorrelation and stationarity [

27]. For example, the main endogenous variable (FNTREZEXPL) turned out to be stationary.

Panel data models were constructed. Due to the fact that there are only 8 companies in our sample, we first estimated the random effects regression models and applied the Hausman and the Breusch–Pagan Lagrange multiplier tests to evaluate whether the random effects model is the most suitable, or whether the fixed effects model should be used instead [

28,

29]. The starting point was the model described by Equation (1).

The robustness of the relationships found was evaluated through two different procedures. The first one is to evaluate the heteroskedasticity and respecify the final models in the robust form. To evaluate heteroskedasticity, the modified Wald test was employed. The robust specification corrects for the heteroskedasticity in the error term. The second approach is to introduce control variables in the regression model and analyze if the initial relationships change in terms of intensity and significance. This approach leads to a respecification of Equation (1) in the following manner:

In case signs and the significance change with the introduction of the control variables, the initial influences are not stable and additional information alters them. Consequently, other more important relationships should be searched for and evaluated.

Another controlling action was to replace the main endogenous variable, FNTREZEXPL (which evaluates economic performance in terms of cash flow), with two others—ROA and ROE (which make the evaluation in terms of incomes). For both variables, the same procedure was followed as in the case of the FNTREZEXPL, namely the estimation of Equation (1), evaluation of the type of effects to be used in the construction of the model, and the estimation of Equation (2) with the introduction of the exogenous control factors. As in the case of the main regression model, the final equations for ROA had to be estimated with fixed effects in the robust form. When ROE was considered, the most suitable model proved to be with random effects.

The first step of the analysis was to descriptively analyze the variables. As

Table 2 shows, high variability was observed in data, results that led to transformations intended to reduce this variation (logarithm, standardization, etc.). The transformed values were used in the panel regression models.

Nuclearelectrica SA presents an upward evolution of profitability rates, labor productivity and the operating cash flow, even if the level of its indicators is below the average level highlighted in

Table 2. In contrast, the duration of inventory rotation is quite long, and there is an unfavorable negative gap between the payment period of suppliers and the duration of collection of receivables.

Romgaz SA presents very good values—above average—throughout the analyzed period for the profitability rates, operating cash flow, and average duration of inventory rotation. In contrast, the labor productivity takes values below the average shown in

Table 2, and there is an unfavorable negative gap between the payment period of suppliers and the duration of collection of receivables.

OMV Petrom SA has in the analyzed period the highest values of the indicators ROA, ROE, and of the operating cash flow, the labor productivity taking values below the average highlighted in

Table 2. The average duration of inventory rotation takes values slightly above average and there is an unfavorable negative gap between the payment period of suppliers and the duration of collection of receivables.

Rompetrol Rafinare SA is the only company that, during the analyzed period, registers a duration of inventory rotation below the average highlighted in

Table 2, and a favorable gap between the payment period of suppliers and the duration of collection of receivables. Instead, profitability rates and labor productivity are below average.

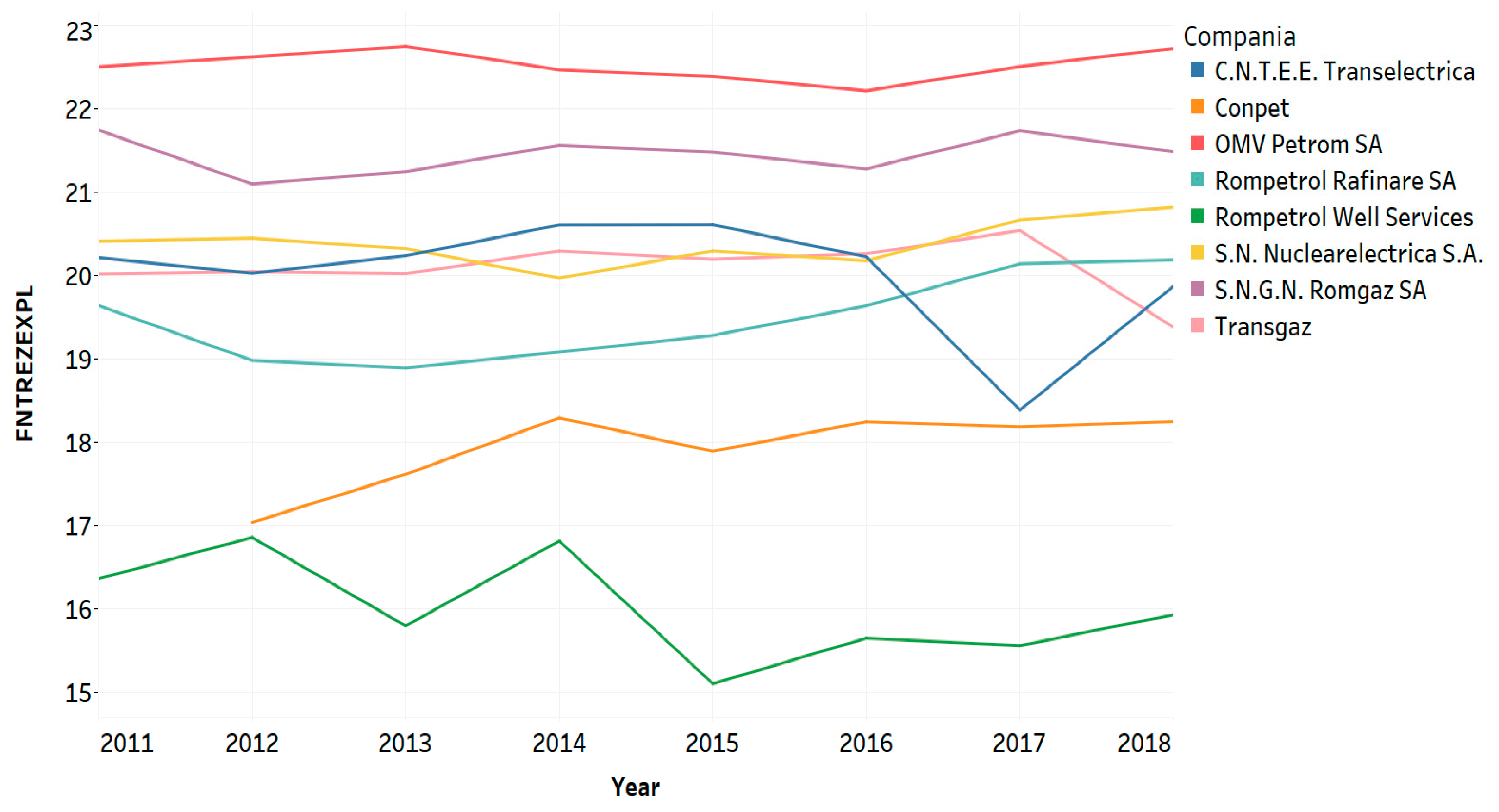

From

Figure 1, it can be noticed that the highest values of the operating flow belong to the company OMV Petrom SA and the lowest ones to Rompetrol Well Service SA.

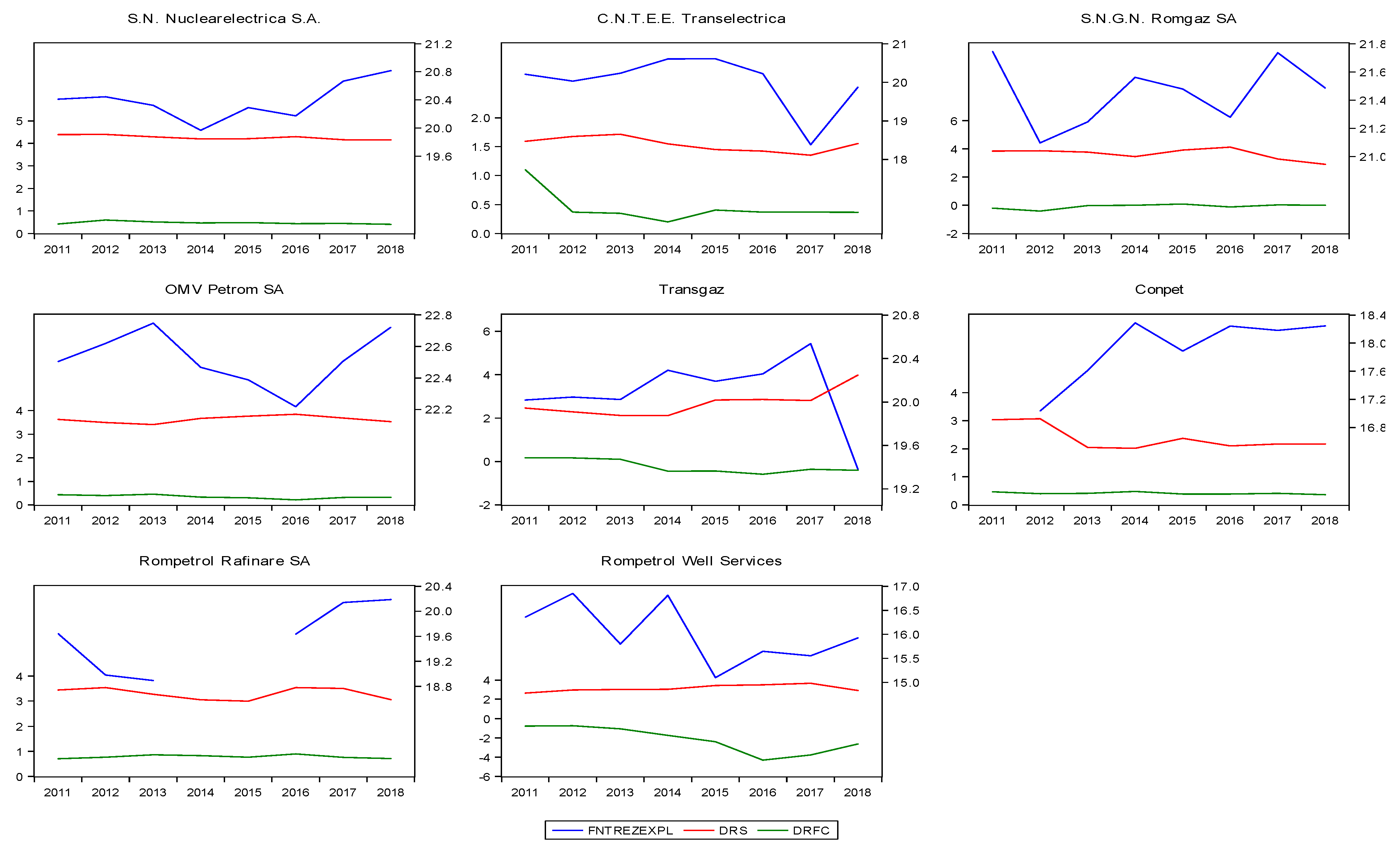

Figure 2 emphasizes that the duration of inventory rotation has a similar evolution with a gap between the average payment period of suppliers and the collection of receivables.

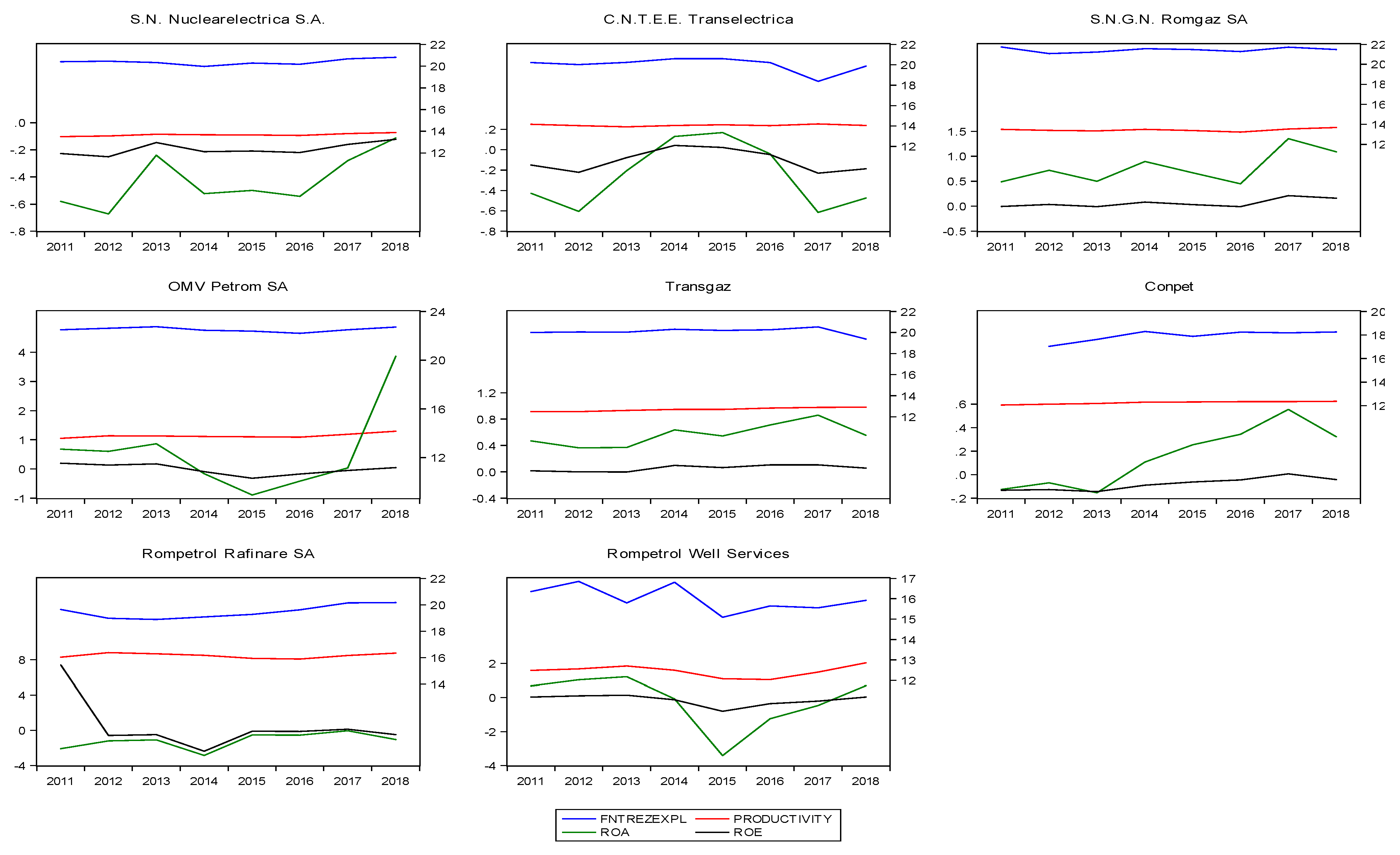

Figure 3 reflects a similar evolution for the operating cash flow, return on equity, and labor productivity, in the case of all the assessed companies.

As it can be seen in the

Table 3, the procedures conducted revealed that for the present sample, the fixed effects model is the most suitable (Breusch–Pagan

p-value = 0.000). The model was respecified in the fixed effects form and homoskedasticity evaluated, due to the high variation in data emphasized by the descriptive analysis. The modified Wald test turned out to be highly significant (

p-value = 0.000), emphasizing heteroskedasticity problems. The final model (FE) was constructed in the robust form.

The FNTREZEXPL is significantly influenced by the DRS and DRF_C. The DRS has a negative influence upon the performance of the Romanian energy companies evaluated based on the operating cash flow. The difference between the DRF and the DRC positively determines the increase in the operating cash flow of these companies. However, the endogenous variable is more significantly influenced by the DRS (p-value = 0.019). The estimated productivity does not have any impact upon the operating cash flow of the analyzed sample (p-value = 0.492).

To verify the robustness of the results, we also controlled for the relationships initially found. For this, we considered two variables, AI and TURNOVER. The correlation matrix emphasized that these two variables are highly correlated. Consequently, we constructed two controlling models for each control factor (Equation (2)). The fixed effects robust model turned out to be the most relevant in all cases.

Table 4 shows that the initial relationships found between the DRS and the dependent variable holds, the coefficient being almost the same, both in the presence of AI and of TURNOVER (with significance at the 5% critical level). The FNTREZEXPL is negatively influenced by the DRS. However, the introduction of these control factors alters the influence of the DRF_C, which becomes insignificant. In relation to productivity, results are the same—there was no significant impact upon the operating cash flow in the presence of the control factors. Out of the last two, only the TURNOVER is significantly and positively influencing the dependent variable.

In conclusion, we can state that in the initial regression, an increase in the DRS leads to a decrease in the operating cash flow, while an increase in the DRF_C (difference between DRF and DRC), has a positive impact upon it. However, only the first relationship remains stable in the presence of the used control factors. They cancel the relationship between the DRF_C and FNTREZEXPL. Additionally, an increase in the turnover of the energy companies listed at the BSE leads to a better financial and economic performance.

Up to this point, we evaluated the impact of the considered factors upon performance expressed through the operating cash flow. The last robustness check procedure that we conducted consisted in replacing the FNTREZEXPL with ROA and ROE in order to evaluate how the factors impact the financial and economic performance seen from the income point of view (see

Table 5 and

Figure 4).

It can be seen from

Figure 4 the uncorrelated and unrelated evolution of ROA and ROE on the one hand, and the duration of inventory rotation and the gap between the payment period of suppliers and the duration of receivables collection on the other hand.

In comparison with the FNTREZEXPL, which is significantly influenced by the DRS, neither ROA nor ROE is. The DRS has no effect upon performance in terms of income for the evaluated energy companies. Another important difference is the fact that, regardless of the specification, productivity is always significant with a positive coefficient, as expected. The difference between the DRF and DRC is positively related to ROA but only in the initial model or in the presence of AI. When the turnover is included in the model, its significance disappears. The second performance indicator in terms of income, ROE, does not have any relationship with the DRF_C.

Among the control factors, only the AI significantly influences ROA, but in a negative manner. An increase in AI would lead to a decrease in performance in terms of ROA. Again, ROE is not significantly connected with AI, while the turnover does not affect any of the two performance indicators.

4. Conclusions and Limits

In this paper, we analyzed the link between companies’ performance in terms of cash and income, and the labor productivity or management rates in case of the companies from the energy sector listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange, because they are large, profitable companies with high liquidity, which are preferred by Romanian and foreign investors, most of them being controlled by the Romanian state through its direct participations.

Using panel regression models, we can state that an increase in the DRS leads to a decrease in the operating cash flow and the productivity has no significant impact upon the operating cash flow in the presence of the control factors. Additionally, an increase in the turnover of the energy companies listed at the BVB leads to a better financial and economic performance.

In comparison with the operating cash flow, the DRS has no effect upon ROA or ROE for the evaluated energy companies. Another important difference is the fact that productivity is always significant with a positive coefficient, as expected.

Through this research we set out to analyze the influences on the operating cash flow in case of energy companies from Romania.

From the period analyzed, because of the lack of data for a series of indicators, a sample of only eight companies was used. Taking a larger sample, future research can empirically analyze the operating cash flow by selecting the variables for which data are available.