Modelling End-User Behavior and Behavioral Change in Smart Grids. An Application of the Model of Frame Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction and State of Research

1.1. Feedback, Information and the Role(s) of End-Users in Future Energy Systems

1.2. Agent-Based Modelling and Simulation of Future Energy Systems

1.3. Purpose and Structure of This Paper

- How do different modes of governance affect the performance of the grid, especially when considering a heterogeneous agent population?

- How can we model heterogeneous end-users and use them as a ‘social ingredient’ to improve technical grid models?

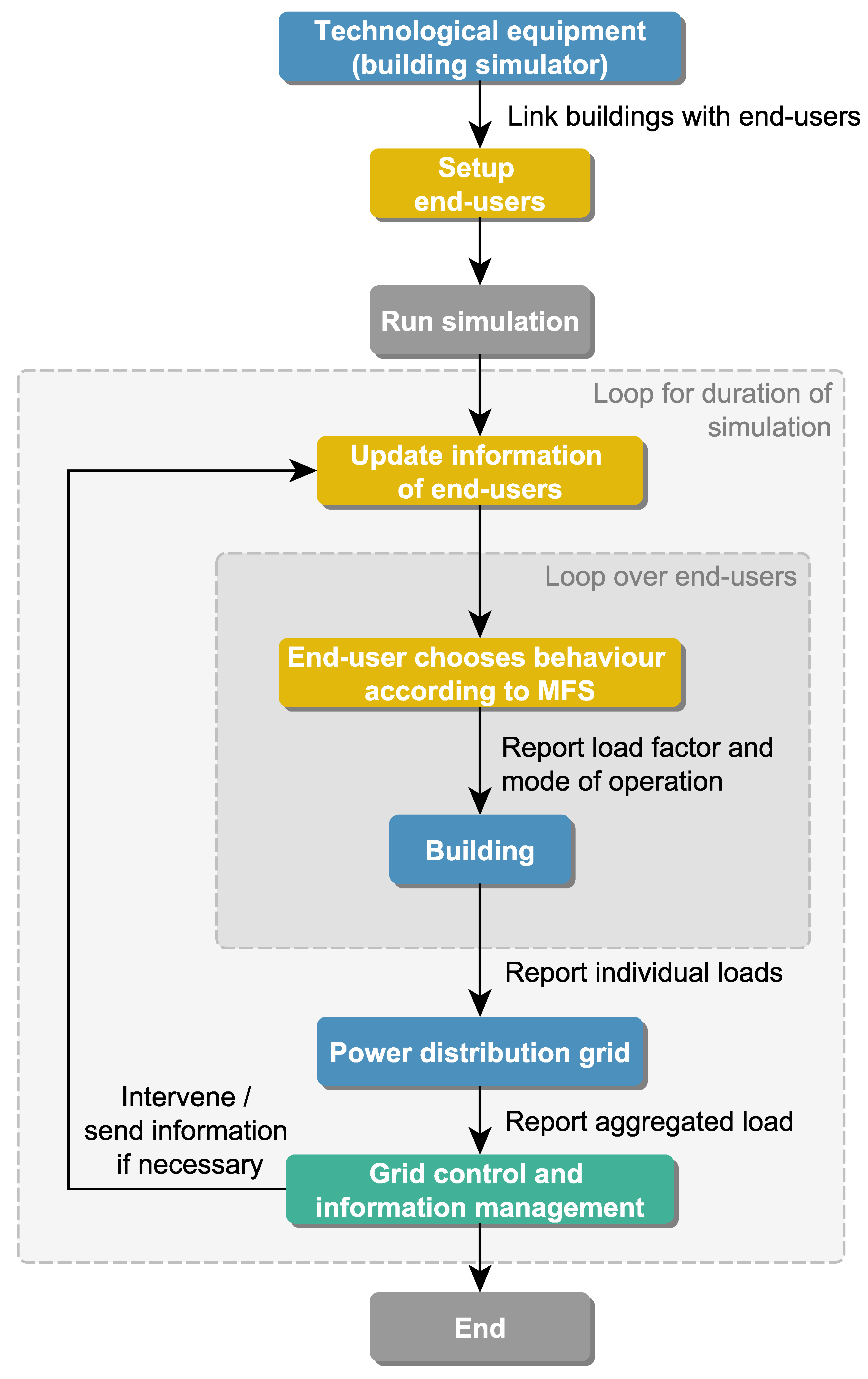

2. An Interdisciplinary Co-Simulation Framework for Future Power Distribution Grids

- Decentral self-organization: All actors make their decisions independently; there is no exchange of information or intervention on part of the DSO (i.e., neither control nor coordination).

- Distributed, soft control: The DSO intervenes and sends feedback and incentives (cf. Tables 1 and 2) to end-users, hoping that they adjust their behavior and contribute to solving the problem at hand. Since end-users’ contribution to collective problem-solving is an integral part of the incentive here, this constitutes a mixed mode of governance that links soft control and coordination.

- Central, strong control: By contract, the DSO is allowed to directly access end-users’ EMSs and retrieve grid-beneficial flexibilities automatically. End-users receive the same information as in soft control; however, the EMS processes this information automatically, leaving the end-user no further leeway in their decision.

3. Agent-Based Model for Residential End-Users’ Behavior

3.1. Purpose

3.2. Theoretical Background

- The selection of a frame (“What kind of situation is this?”),

- the selection of a script (“Which way of acting is appropriate?”),

- and lastly the selection of an action (“What am I going to do?”) [42] (p. 99).

3.3. Entities, State Variables, and Scales

- General attributes

- Static MFS-related attributes

- Situational information

- Results of the MFS decision process

- Energy-related output

- Dissatisfaction-related attributes

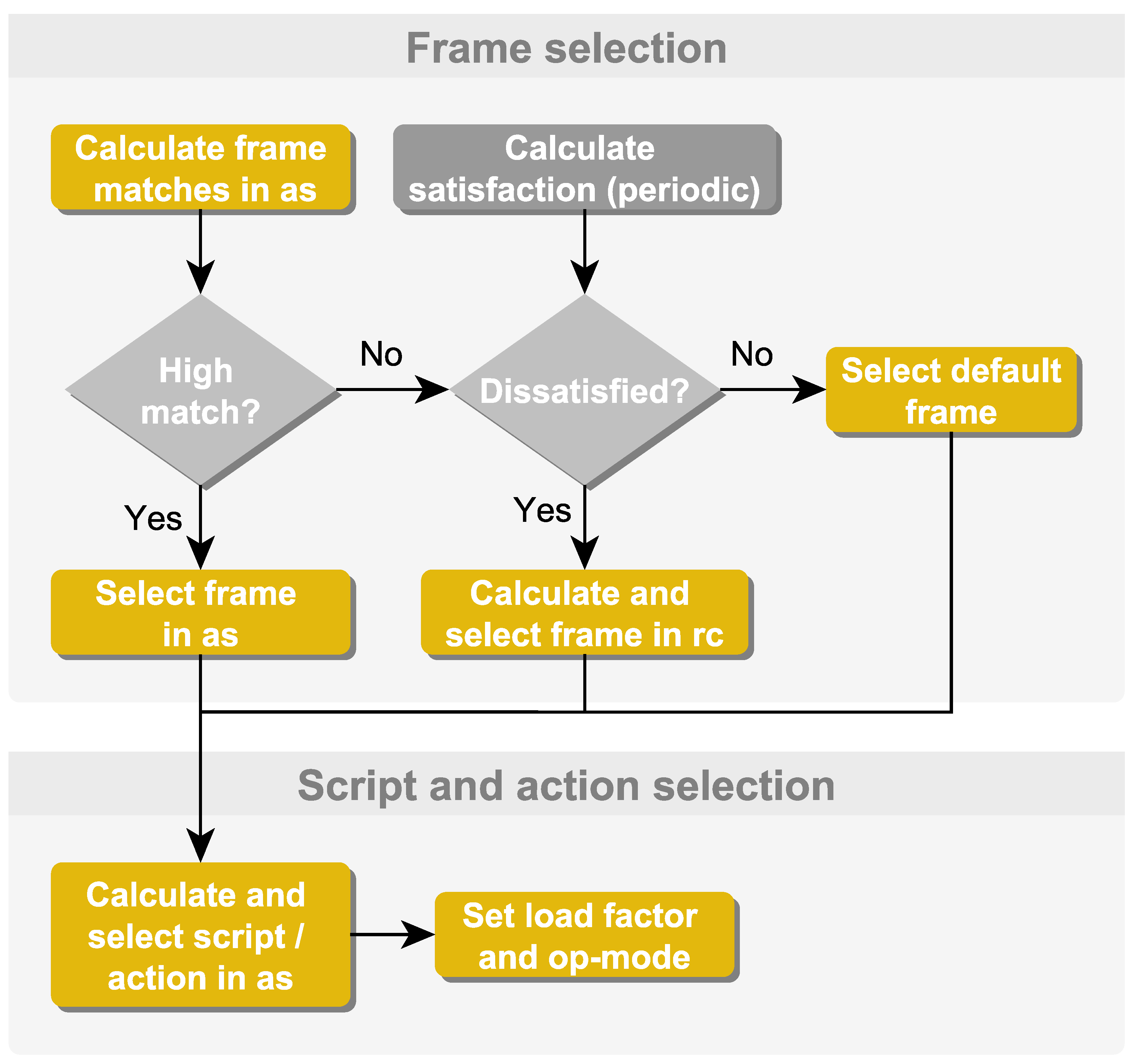

3.4. Individual Decision-Making

- End-users select another frame or script in as-mode if the match (i.e., the perceived fittingness of frames and scripts, max. value 1) of the best option is sufficiently high (above 0.8) or higher than the other options (twice as high as second best option’s match);

- End-users can switch from as-mode to rc-mode if no match stands out and they are dissatisfied with their past behavior (see Section 3.5.4).

3.4.1. Frame Selection in as-Mode

| Algorithm 1: Presence of Situational Objects |

| If request present = True: |

| If request duration > spontaneity threshold: |

| o = (request duration − spontaneity threshold)/attitude (capped at 1) |

| Else: o = 0 |

| Else: o = 0 |

3.4.2. Frame Selection in rc-Mode

3.4.3. Script and Action Selection in as-Mode

- “Business as usual” (script 0): The end-user does not change their actions at all and behaves as usual.

- “Adjusting power consumption” (script 1): The end-user changes their behavior, i.e., increasing or decreasing consumption within reasonable limits relative to their standard behavior (cf. Table 1). Additionally, the end-user changes the settings of their EMS to ‘cost-optimal’.

- “Following recommendation of DSO” (script 2): The end-user adjusts their power consumption (see above) and additionally changes the EMS to a ‘grid-beneficial setting’, if available.

3.5. Further Design Concepts

3.5.1. Interactions and Social Influence

3.5.2. Empirical Background and Agent Heterogeneity

- Hesitant skeptics: Typically not inclined to act and skeptical about interventions and the benefits of smart metering; aspire conformity within their social network.

- Eco-responsible helpers: Exhibit a strong sense of responsibility and a constant need to act; prioritize environmental concerns over all other needs.

- Cost-conscious materialists: Most likely to act due to cost-minimizing reasons.

- Spendthrifts: No prominent dispositions, but put high trust in DSOs’ and municipal utilities’ interventions; while group conformity is important, cost-related issues play an inferior role.

3.5.3. Stochasticity

3.5.4. Learning

3.6. Implementation Details

4. Results

4.1. Scenario Definition and Experimental Set-Up

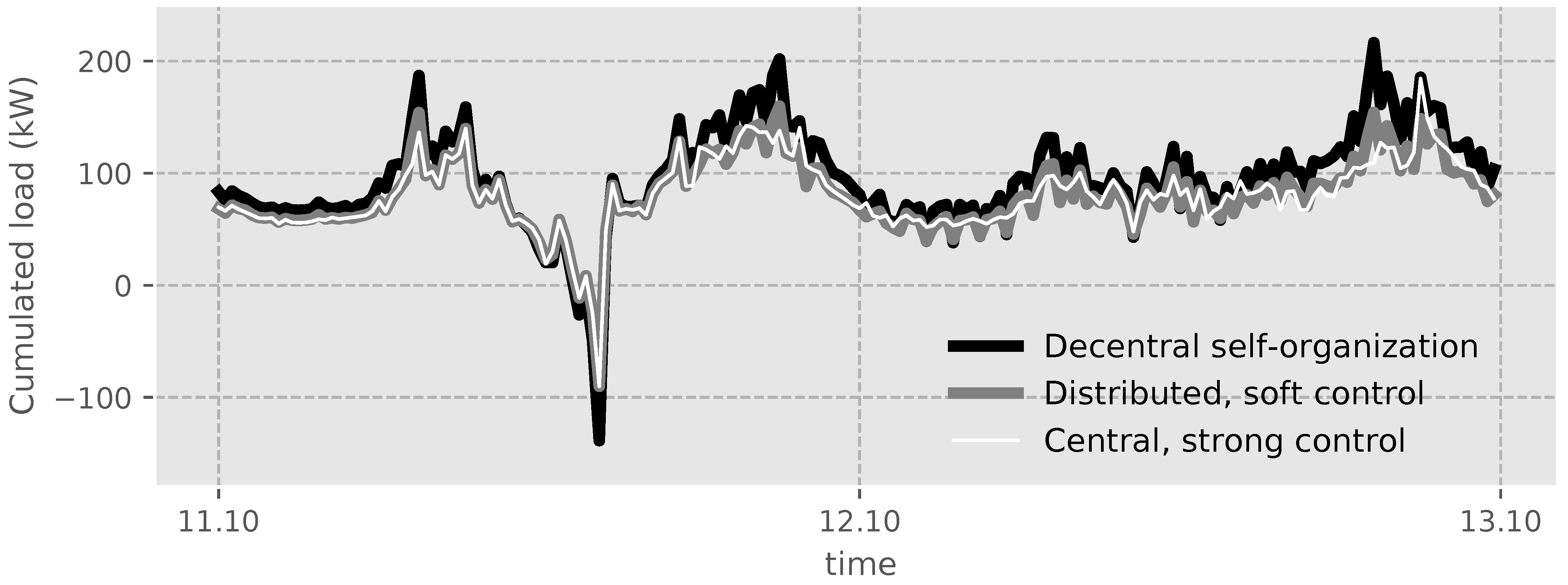

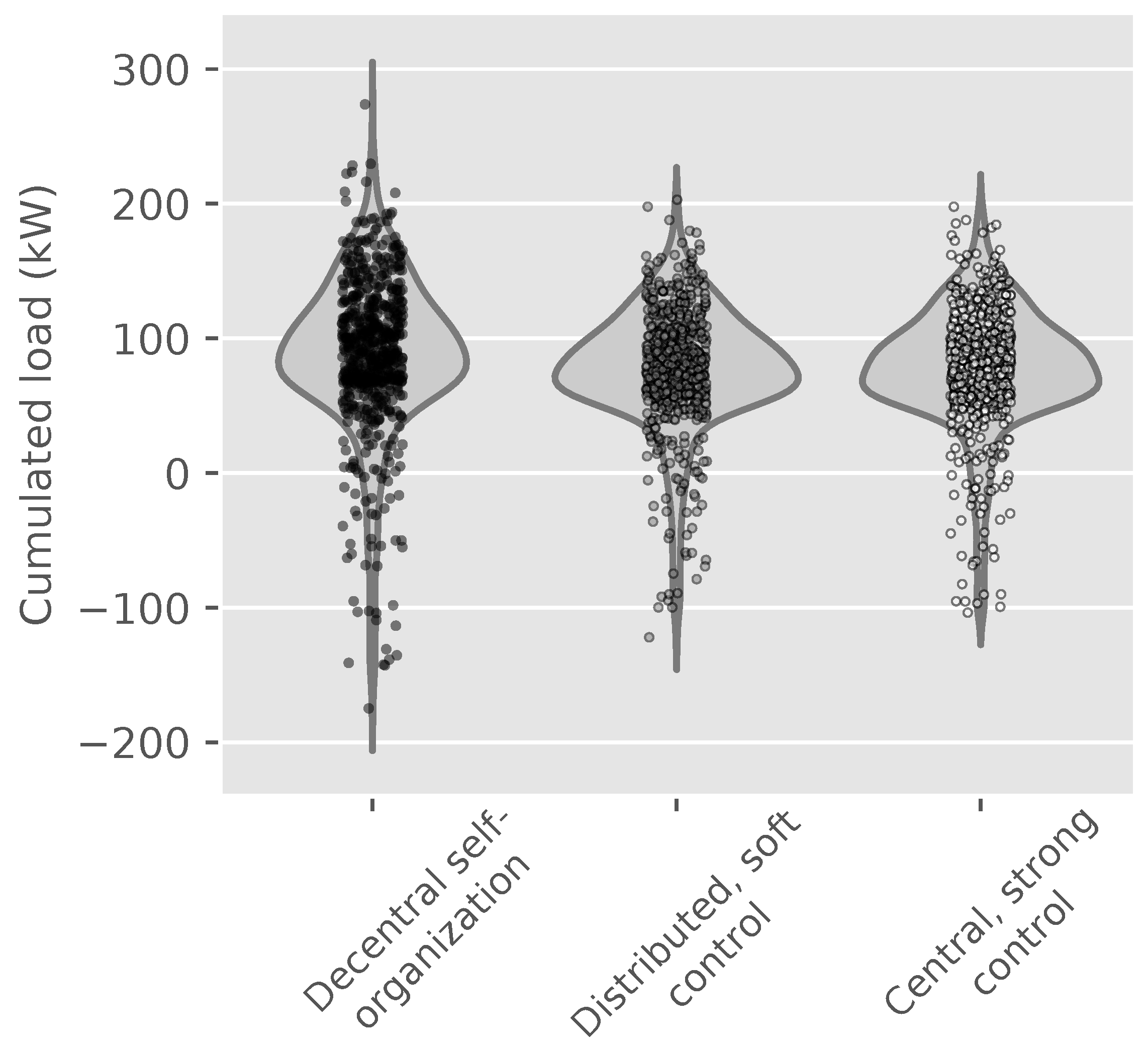

4.2. Simulation Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | MFS Variable | Relates to | Operationalization | No. of Items | Examples 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chronic accessibility | Frame (as) | Personal ascription of responsibility concerning success of energy transition (frame 1) | 4 | “I’m always trying to make a contribution to the energy transition.” “The success of the energy transition is beyond my capabilities.” (neg.) |

| 2 | Presence of situational objects | Frame (as) | Self-reported spontaneity and impulsive behavior | 4 | “I usually take my time before making decisions.” (neg.) “I often decide by gut feeling.” |

| 3 | Presence of situational objects | Frame (as) | Attitude towards possibilities of smart metering | 4 | “I find the use of a Smart Meter interesting due to the possibilities of use.” |

| 4 | Preferences | Frame (rc) | Subjectively evaluated preferences when making decisions; relate to (1) costs, (2) eco-friendliness, (3) social norm and (4) grid-beneficial behavior | 1 for each preference | When making electricity-related decisions, it is important to me that… “… the environment is treated with care.” (eco-friendliness) “… I meet the expectations of people who are important to me.” (social norm) |

| 5 | Chronic accessibility | Script (as) | Experiences with energy saving behavior (script 1) | 6 | How often have you done the following in the past year? “Unplugged electrical appliances (e.g., computers, televisions, etc.) when they were not in use.” |

| 6 | Chronic accessibility | Script (as) | Trust in recommendations of DSO/electric utility (script 2) | 5 | “I think that my electric utility makes a competent impression.” |

| No. | Scale | Source; Based on | Internal Consistency of Scale* | Mean | Standard Deviation | Explained Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Five-level Likert scale (agreement) | [93,94] | 0.785 | 3.70 | 0.93 | 63.17% |

| 2 | Five-level Likert scale (agreement) | [95] | 0.690 | 2.91 | 0.74 | 52.04% |

| 3 | Five-level Likert scale (agreement) | [96,97] | 0.913 | 3.97 | 0.85 | 79.53% |

| 4 | Rating scale, adds up to 100% for all preferences. | Own custom scale | - | 0.40 (1), 0.37 (2), 0.07 (3), 0.16 (4) | 0.20 (1), 0.17 (2), 0.07 (3), 0.10 (4) | - |

| 5 | Five-level scale (frequency) | [98,99,100] | ** | 3.52 | 0.57 | - |

| 6 | Five-level Likert scale (agreement) | [96] | 0.904 | 3.56 | 0.75 | 72.64% |

Appendix B

| Cluster Means and Parametrization * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFS-Variable | Refers to | Description (Short) | Hesitant Skeptics | Eco-Responsible Helpers | Cost-Conscious Materialists | Spendthrifts |

| Chronic accessibility | Frame (as) | Personal responsibility | 0.56 (−0.95) | 0.83 (0.51) | 0.65 (−0.48) | 0.75 (0.07) |

| Presence of sit. objects | Frame (as) | Spontaneity ** | - | - | - | - |

| Presence of sit. objects | Frame (as) | Attitude *** | 3.75 (−2.01) | 1.73 (0.35) | 2.02 (0.01) | 1.90 (0.15) |

| Preferences | Frame (rc) | Eco-friendliness | 0.15 (−0.86) | 0.49 (0.73) | 0.24 (−0.58) | 0.36 (−0.27) |

| Preferences | Frame (rc) | Cost | 0.44 (0.38) | 0.29 (−0.34) | 0.58 (0.64) | 0.34 (−0.43) |

| Preferences | Frame (rc) | Grid-beneficial | 0.26 (1.02) | 0.18 (0.23) | 0.12 (−0.33) | 0.12 (−0.44) |

| Preferences | Frame (rc) | Social norm | 0.15 (1.12) | 0.03 (−0.42) | 0.05 (−0.27) | 0.17 (0.78) |

| Chronic accessibility | Script (as) | Experience energy saving | 0.62 (−0.76) | 0.75 (0.43) | 0.64 (−0.55) | 0.73 (0.25) |

| Chronic accessibility | Script (as) | Trust utility | 0.64 (−0.51) | 0.73 (0.10) | 0.67 (−0.25) | 0.77 (0.38) |

| Share (N = 95 ****) | 9.5% (9) | 41.1% (39) | 30.2% (29) | 18.8% (18) | ||

References

- Järventausta, P.; Repo, S.; Rautiainen, A.; Partanen, J. Smart grid power system control in distributed generation environment. Annu. Rev. Control. 2010, 34, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesnetzagentur. Flexibility in the Electricity System. Status Quo, Obstacles and Approaches for a Better Use of Flexibility; Bundesnetzagentur: Bonn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, J.; Barton, B.; Carrington, G.; Doering, A.; Ford, R.; Hopkins, D.; Lawson, R.; McCarthy, A.; Rees, D.; Scott, M.; et al. The energy cultures framework: Exploring the role of norms, practices and material culture in shaping energy behaviour in New Zealand. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 7, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, T.; Nye, M.; Burgess, J. Keeping energy visible? Exploring how householders interact with feedback from smart energy monitors in the longer term. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.Q.; Nieuwenhijsen, I.; De Vries, B.B.; Blokhuis, E.E.; Schaefer, W.W. Intervention strategy to stimulate energy-saving behavior of local residents. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, T. Beyond energy feedback. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 46, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrangrad, M. A review of demand side management business models in the electricity market. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, B.; Ford, R.; Squiers, C. Energy feedback technology: A review and taxonomy of products and platforms. Energy Effic. 2013, 7, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulden, M.; Bedwell, B.D.; Rennick-Egglestone, S.; Rodden, T.; Spence, A. Smart grids, smart users? The role of the user in demand side management. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döbelt, S.; Jung, M.; Busch, M.; Tscheligi, M. Consumers’ privacy concerns and implications for a privacy preserving Smart Grid architecture—Results of an Austrian study. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 9, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, C.; Darras, B.; Bean, E.; Srivastava, A.; Frickel, S. Privacy, technology, and norms: The case of Smart Meters. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 51, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgornik, A.; Sucic, B.; Blazic, B. Effects of customized consumption feedback on energy efficient behaviour in low-income households. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 130, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvaronavičienė, M.; Prakapienė, D.; Garškaitė-Milvydienė, K.; Prakapas, R.; Nawrot, Ł. Energy Efficiency in the Long-Run in the Selected European Countries. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 11, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madlener, R.; Turner, K. After 35 Years of Rebound Research in Economics: Where Do We Stand? In Rethinking Climate and Energy Policies: New Perspectives on the Rebound phenomenon; Santarius, T., Walnum, H.J., Aall, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 17–36. ISBN 978-3-319-38805-2. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish, B.; Heptonstall, P.; Gross, R.; Sovacool, B.K. A systematic review of motivations, enablers and barriers for consumer engagement with residential demand response. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vries, G. Public Communication as a Tool to Implement Environmental Policies. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2019, 14, 244–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; De Vries, G. Social Innovation and the Energy Transition. Sustainability 2018, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Energy Citizenship: Psychological Aspects of Evolution in Sustainable Energy Technologies. In Governing Technology for Sustainability; Murphy, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 63–86. ISBN 9781849771511. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Coping with tragedies of the commons. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 1999, 2, 493–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. The research agenda on social acceptance of distributed generation in smart grids: Renewable as common pool resources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselink, L.X.; Chappin, E. Adoption of energy efficient technologies by households—Barriers, policies and agent-based modelling studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 99, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, I.; Kasmire, J. Theory. In Agent-Based Modelling of Socio-Technical Systems; van Dam, K.H., Nikolic, I., Lukszo, Z., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 11–71. ISBN 978-94-007-4932-0. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz, G.; Alkemade, F.; De Haan, F.; Köhler, J.; Trutnevyte, E.; Luthe, T.; Halbe, J.; Papachristos, G.; Chappin, E.; Kwakkel, J.; et al. Prospects of modelling societal transitions: Position paper of an emerging community. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 17, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevska, J.; Douw, J.; Mengolini, A.; Nikolic, I. An Agent-Based Model of Electricity Consumer: Smart Metering Policy Implications in Europe. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, F. An Empirically Grounded Model of Green Electricity Adoption in Germany: Calibration, Validation and Insights into Patterns of Diffusion. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopha, B.M.; Klöckner, C.A.; Hertwich, E.G. Adoption and diffusion of heating systems in Norway: Coupling agent-based modeling with empirical research. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2013, 8, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotts, N.M.; Polhill, J.G. Experiments with a Model of Domestic Energy Demand. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasimeni, F. Community-Based Adoption and Diffusion of Micro-Grids: Analysis of the Italian Case with Agent-Based Model. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrakas, V.; Papadelis, S.; Flamos, A. An agent-based model to simulate technology adoption quantifying behavioural uncertainty of consumers. Appl. Energy 2019, 255, 113795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappin, E.; Afman, M.R. An Agent-Based Model of Consumer Lighting. In Agent-Based Modelling of Socio-Technical Systems; van Dam, K.H., Nikolic, I., Lukszo, Z., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 181–200. ISBN 978-94-007-4932-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.; Holtz, G.; Chappin, E. Agent-based assessment framework for behavior-changing feedback devices: Spreading of devices and heating behavior. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 98, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Lee, S. An empirically grounded model for simulating normative energy use feedback interventions. Appl. Energy 2016, 173, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Xiao, F.; Wang, S. Neighborhood-level coordination and negotiation techniques for managing demand-side flexibility in residential microgrids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringler, P.; Keles, D.; Fichtner, W. Agent-based modelling and simulation of smart electricity grids and markets–A literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaimi, J.; Rahim-Amoud, R.; Merghem-Boulahia, L. Energy Management in the Smart Grids via Intelligent Storage Systems. In Contemporary Approaches and Methods in Fundamental Mathematics and Mechanics; Alonso-Betanzos, A., Sanchez-Maroño, N., Fontenla-Romero, O., Polhill, G., Craig, T., Bajo Peréz, J., Corchado, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, I.F.; Gonçalves, I.; Lopes, M.A.; Antunes, C.H. A multi-agent system approach to exploit demand-side flexibility in an energy community. Util. Policy 2020, 67, 101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čaušević, S.; Warnier, M.; Brazier, F.M. Self-determined distribution of local energy resources for ensuring power supply during outages. Energy Inform. 2019, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovati, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, P.; Olsmats, C.; Maturi, L. Optimal Simulation of Three Peer to Peer (P2P) Business Models for Individual PV Prosumers in a Local Electricity Market Using Agent-Based Modelling. Buildings 2020, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, E.; Higginson, S.; Grunewald, P.; Darby, S.J. Simulating residential demand response: Improving socio-technical assumptions in activity-based models of energy demand. Energy Effic. 2018, 11, 1583–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, J.; Engel, D.; Lehnhoff, S. Conceptual Design of an Agent-Based Socio-Technical Demand Response Consumer Model. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 16th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Porto, Spain, 18–20 July 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 680–685, ISBN 978-1-5386-4829-2. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, L.C.; Aoki, A.R.; Lambert-Torres, G.; Lambert-De-Andrade, N.; Paterakis, N.G. An Agent-Based Approach for the Planning of Distribution Grids as a Socio-Technical System. Energies 2020, 13, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroneberg, C. Frames, scripts, and variable rationality: An integrative theory of action. In Analytical Sociology: Actions and Networks; Manzo, G., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo Rodríguez, D.I.; Hoffmann, S.; Adelt, F.; Myrzik, J.; Weyer, J. A Socio-Technical Simulation Framework for Collaborative Management in Power Distribution Grids. In Proceedings of the International ETG Congress 2017, Bonn, Germany, 28–29 November 2017; VDE: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2017. ISBN 9783800745050. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, H. Soziologie. Allgemeine Grundlagen; Campus: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1993; ISBN 9783593349602. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, H. The Rationality of Everyday Behavior. Ration. Soc. 1993, 5, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, H.; Kroneberg, C. An Integrative Theory of Action: The Model of Frame Selection. In Order on the Edge of Chaos; Lawler, E.J., Thye, S.R., Yoon, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 63–85. ISBN 9781139924627. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, D.I.H.; Hinker, J.; Myrzik, J.M. On the problem formulation of model predictive control for demand response of a power-to-heat home microgrid. In Proceedings of the 19th Power Systems Computation Conference PSCC, Genua, Italy, 20–24 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weyer, J.; Adelt, F.; Hoffmann, S. Governance of Complex Systems: A Multi-Level Model; Technische Universität Dortmund: Dortmund, Germany, 2015; Volume 42, Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2003/34132 (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- BDEW. Smart Grid Traffic Light Concept. Design of the Amber Phase; Federal Association of the German Energy and Water Industries: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, B.; Bohn, F.; Dreßler, G.; Groeneveld, J.; Klassert, C.; Martin, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schulze, J.; Weise, H.; Schwarz, N. Describing human decisions in agent-based models—ODD + D, an extension of the ODD protocol. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 48, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, V.; Berger, U.; Bastiansen, F.; Eliassen, S.; Ginot, V.; Giske, J.; Goss-Custard, J.; Grand, T.; Heinz, S.K.; Huse, G.; et al. A standard protocol for describing individual-based and agent-based models. Ecol. Model. 2006, 198, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilensky, U. NetLogo. 1999. Available online: https://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/ (accessed on 30 January 2019).

- Adelt, F.; Weyer, J.; Hoffmann, S.; Ihrig, A. Simulation of the Governance of Complex Systems (SimCo): Basic Concepts and Experiments on Urban Transportation. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2018, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroneberg, C.; Yaish, M.; Stocké, V. Norms and Rationality in Electoral Participation and in the Rescue of Jews in WWII. Ration. Soc. 2010, 22, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, H. Wie wirken Subkulturen der Gewalt? Das Zusammenspiel von Internalisierung und Verbreitung gewaltlegitimierender Normen in der Erklärung von Jugendgewalt. Kölner Z. Soziol. Sozialpsychol. 2016, 68, 457–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroneberg, C.; Kalter, F. Rational Choice Theory and Empirical Research: Methodological and Theoretical Contributions in Europe. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2012, 38, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, H.; Kneip, T. The impact of attitudes and behavioral costs on environmental behavior: A natural experiment on household waste recycling. Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 40, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Dilley, L.; Crawford, J. Energy consumption behaviour: Rational or habitual? disP Plan. Rev. 2014, 50, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, W. Stimulating the diffusion of photovoltaic systems: A behavioural perspective. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Wood, W. Interventions to Break and Create Consumer Habits. J. Public Policy Mark. 2006, 25, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, L. Mental models: A robust definition. Learn. Organ. 2013, 20, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, W. Modelling Consumer Behaviour. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.A.; Jager, W. Stimulating diffusion of green products. J. Evol. Econ. 2002, 12, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Ernst, A. Agent-based modeling of the diffusion of environmental innovations—An empirical approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2009, 76, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Dowlatabadi, H. Models of Decision Making and Residential Energy Use. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2007, 32, 169–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevska, J.; Gangale, F.; Mengolini, A. Evolving Role of Distribution System Operators in End User Engagement. In Proceedings of the CIRED Workshop 2016, Helsinki, Finland, 14–15 June 2016; Institution of Engineering and Technology: London, UK, 2016. ISBN 978-1-78561-202-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kroneberg, C. Die Definition der Situation und die variable Rationalität der Akteure/The Definition of the Situation and the Variable Rationality of Actors. Z. Soziol. 2005, 34, 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, B.; Zinger, J.F.; Ford, R. The effects of feedback on energy conservation: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1205–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plenz, M.; Hirschl, B. Prosumer im Energiesystem. Ökol. Wirtsch. 2016, 31, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, W. Breaking ’Bad Habits’: A Dynamical Perspective on HABIT Formation and Change. In Human Decision Making and Environmental Perception. Understanding and Assisting Human Decision Making in Real-Life Settings; Liber Americum for Charles Vlek; Jager, W., Hendrickx, L., Steg, L., Eds.; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Büscher, C.; Sumpf, P. “Trust” and “confidence” as socio-technical problems in the transformation of energy systems. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2015, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SurveyCircle. Research Website SurveyCircle; Mannheim. 2020. Available online: https://www.surveycircle.com (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Plinke, W.; Weiber, R. Multivariate Analysemethoden; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-662-46075-7. [Google Scholar]

- Formann, A. Die Latent-Class-Analyse: Einführung in Die Theorie und Anwendung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S. A Review of Unquestioned Standards in Using Cluster Analysis for Data-Driven Market Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference 2002 (ANZMAC 2002), Melbourne, Australia, 2–4 December 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Broman Toft, M.B.; Schuitema, G.; Thøgersen, J. Responsible technology acceptance: Model development and application to consumer acceptance of Smart Grid technology. Appl. Energy 2014, 134, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OFFIS. Mosaik—A Flexible Smart Grid Co-Simulation Framework; OFFIS: Oldenburg, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://mosaik.offis.de/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Scheffler, J.U. Bestimmung der Maximal Zulässigen Netzanschlussleistung Photovoltaischer Energiewandlungsanlagen in Wohnsiedlungsgebieten. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Chemnitz, Fakultät für Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik, Chemnitz, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hierzinger, R.; Herry, M.; Seisser, O.; Steinacher, I.; Wolf-Ebert, S. Energy Styles Klimagerechtes Leben der Zukunft. Energy Styles als Ansatzpunkt für Effiziente Policy Interventions; Österreichische Energieagentur: Wien, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, R. The double-edged sword of decentralized energy autonomy. Energy Policy 2018, 113, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, P.; Rigby, D.; Azapagic, A. Energy self-sufficiency, grid demand variability and consumer costs: Integrating solar PV, Stirling engine CHP and battery storage. Appl. Energy 2015, 155, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Bradley, K.J. Best Practice Recommendations for Designing and Implementing Experimental Vignette Methodology Studies. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmüller, C.; Steiner, P.M. Experimental Vignette Studies in Survey Research. Methodology 2010, 6, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostiukevych, R.; Mishchuk, H.; Zhidebekkyzy, A.; Nakonieczny, J.; Akimov, O. The impact of European integration processes on the investment potential and institutional maturity of rural communities. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 13, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, L.M.; Fischer, L.-B.; Newig, J.; Lang, D.J. Driving factors for the regional implementation of renewable energy-A multiple case study on the German energy transition. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M.; Rudolph, D. Conceptualizing rural energy transitions: Energizing rural studies, ruralizing energy research. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 73, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G. Legitimacy and field development: Electricity transition(s) in Germany. Glob. Trans. 2019, 1, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, B.; Gross, R.; Heptonstall, P. On demand: Can demand response live up to expectations in managing electricity systems? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 51, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavytskyy, A.; Kharlamova, G.; Giedraitis, V.; Šumskis, V. Estimating the interrelation between energy security and macroeconomic factors in European countries. J. Int. Stud. 2018, 11, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaat, S.; Jager, W.; Dickert, S.; Schaat, S.; Jager, W.; Dickert, S.; Schaat, S.; Jager, W.; Dickert, S. Psychologically Plausible Models in Agent-Based Simulations of Sustainable Behavior. In Agent-Based Modeling of Sustainable Behaviors; Alonso-Betanzos, A., Sanchez-Maroño, N., Fontenla-Romero, O., Polhill, G., Craig, T., Bajo Peréz, J., Corchado, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-3-319-46330-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A.; Matthies, E.; Höger, R. Verantwortungszuschreibung Intern Spezifisch; Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). 2014. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6102/zis63 (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Martens, T.; Rost, J.; Gresele, C. Verantwortung für Umweltprobleme; Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). 2014. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6102/zis205 (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Kovaleva, A.; Beierlein, C.; Kemper, C.J.; Rammstedt, B. Eine Kurzskala zur Messung von Impulsivität nach dem UPPS-Ansatz: Die Skala Impulsives-Verhalten-8 (I-8). GESIS-Working Papers; Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften: Mannheim, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-F.; Xu, X.; Arpan, L. Between the technology acceptance model and sustainable energy technology acceptance model: Investigating smart meter acceptance in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 25, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riester, J. Energie 4.0—Die Digitalisierung der Energiewirtschaft. Eine Empirische Untersuchung zur Verbraucherseitigen Akzeptanz der Smart Meter Technologie und Implikationen für deren Vermarktung; Hochschule Hof: Hof, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-935565-29-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brosch, T.; Patel, M.; Sander, D. Affective Influences on Energy-Related Decisions and Behaviors. Front. Energy Res. 2014, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schahn, J. Skalensystem zur Erfassung des Umweltbewusstseins (SEU3); Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). 1999. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6102/zis167 (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. How do socio-demographic and psychological factors relate to households’ direct and indirect energy use and savings? J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, T. Book Review: A Concise Guide to Market Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-662-56706-7. [Google Scholar]

| End-User Variable | Values | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Type | “Eco-helper”, “Spendthrift”, “Materialist”, “Skeptic” | Affiliation to one of the four empirical agent-clusters; determines the parametrization concerning decision-making relevant variables. |

| Technological equipment | “Inflexible electrical devices only”, “PV system only”, “PV system with battery storage”, “PV system and heating pump”, “Heating pump only” | One of five predefined equipment configurations; input from the building simulator; static and does not change over time. | |

| Social network | List of agents | Consists of 20 other randomly selected end-users; static and does not change over time. | |

| B | Frame-related dispositions | Chronic accessibility (value btw. 0 and 1), Presence of situational objects (btw. 0 and 1), Associative link (btw. 0 and 1), Spontaneity threshold (btw. 0 and 4), Attitude (btw. 1 and 5) | Variables for calculating the matches of the frames; static and does not change over time. Relevant for as-mode. |

| Frame-related preferences | Number between 0 and 1 for each of the four preferences (cost savings, eco-friendliness, social norm and compliance) | Relates to the importance of the four quantitative information (“information profile”) and the probability to perceive a need to act (frame 1), if these information reveal a discrepancy. Relevant for rc-mode. | |

| Script- and action-related dispositions | Chronic accessibility (value btw. 0 and 1), Temporary accessibility (btw. 0 and 1) | Variables for calculating the matches of the scripts. Relevant for as-mode. | |

| C | Information profile | List of values for each of the four quantitative information (costs, own consumption, consumption of peers, share of cooperation) in course of time | An agent’s memory concerning current and historical information. Gets updated when grid control sends a request. Relevant for rc-mode. |

| D | Match | Number between 0 and 1 for each frame and script/action | Relates to the fit and suitability of a frame/script in a given situation. |

| Current frame | “No need to act” (0), “Need to act” (1) | The currently chosen frame. | |

| Current script and action | “Doing nothing” (0), “Adjusting power consumption” (1), “Following recommendation” (2) | The currently chosen script and action. | |

| E | Current mode of operation | “Cost-optimal”, “Grid-beneficial” | Simplified settings for the EMS that an agent possesses. Cost-optimal settings are the default for all types of equipment; grid-beneficial settings are available to all but inflexible electricity devices. |

| Current load factor | Value between 0.5 and 2 | Modification (percentage) of the standard load profile (building simulator) of an end-user, indicating that they may habitually use more or less power. Values get updated due to behavioral changes: Each selection of script/action 1 or 2 results in a 10% de-/increase of the previous value; 10% of that change (i.e., 1% of the old value) will remain in the next step, indicating familiarization effects. | |

| F | Dissatisfaction threshold | Value between 0 and 1 | Threshold for determining the dissatisfied status. |

| Dissatisfied? | Boolean | An agent’s dissatisfaction with regard to its current situation, compared to the past. Used for determining decision-making in rc-mode. Gets updated every day. |

| Type | Feedback (f) | Reference (r) | Threshold (for Frame 1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power consumption | personal power consumption of the last 24 h | historical average of the personal power consumption | >10% deviation |

| Electricity cost | average electricity costs of the last 24 h | historical average of electricity costs | >10% deviation |

| Social comparison | personal power consumption of the last 24 h | average consumption of other households in the personal social network | >10% deviation |

| Cooperativeness | none | share of households that pledged their support in the past (i.e., share of households that followed the request/recommendation) | <50% supporters |

| Share | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population | Hesitant skeptics | 10% |

| Eco-responsible helpers | 40% | |

| Cost-conscious materialists | 30% | |

| Spendthrifts | 20% | |

| Building modernization | PV systems only | 35% |

| PV systems with battery storage | 10% | |

| PV systems and heating pumps | 5% | |

| Heating pumps only | 10% | |

| Inflexible electricity devices only | 40% | |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Maximum | Minimum | 0.99-Percentile | 0.01-Percentile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decentral self-organization | 88.3 | 57.7 | 273.8 | −174.8 | 208.3 | −118.5 |

| Distributed, soft control | 77.6 | 44.0 | 203.0 | −122.0 | 166.9 | −81.8 |

| Central, strong control | 77.7 | 44.0 | 197.8 | −103.6 | 173.7 | −84.7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoffmann, S.; Adelt, F.; Weyer, J. Modelling End-User Behavior and Behavioral Change in Smart Grids. An Application of the Model of Frame Selection. Energies 2020, 13, 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246674

Hoffmann S, Adelt F, Weyer J. Modelling End-User Behavior and Behavioral Change in Smart Grids. An Application of the Model of Frame Selection. Energies. 2020; 13(24):6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246674

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoffmann, Sebastian, Fabian Adelt, and Johannes Weyer. 2020. "Modelling End-User Behavior and Behavioral Change in Smart Grids. An Application of the Model of Frame Selection" Energies 13, no. 24: 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246674

APA StyleHoffmann, S., Adelt, F., & Weyer, J. (2020). Modelling End-User Behavior and Behavioral Change in Smart Grids. An Application of the Model of Frame Selection. Energies, 13(24), 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246674