Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to this work as follows: Conceptualization, K.S. and M.K.; Methodology, K.S.; Software, K.S. and T.A.; Validation, K.S. and M.K.; Formal Analysis, K.S.; Investigation, K.S. and M.K.; Resources, M.K.; Data Curation, K.S. and T.A.; Writing–Original Draft Preparation, K.S.; Writing–Review & Editing, K.S. and K.M.; Visualization, K.S.; Supervision, M.S. and T.W.; Project Administration, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Floor plan of verification room.

Figure 1.

Floor plan of verification room.

Figure 2.

System configuration.

Figure 2.

System configuration.

Figure 3.

Status of CRAC.

Figure 3.

Status of CRAC.

Figure 4.

Setting of return temperature.

Figure 4.

Setting of return temperature.

Figure 5.

Power consumption of CRAC.

Figure 5.

Power consumption of CRAC.

Figure 6.

Supply temperature of CRAC.

Figure 6.

Supply temperature of CRAC.

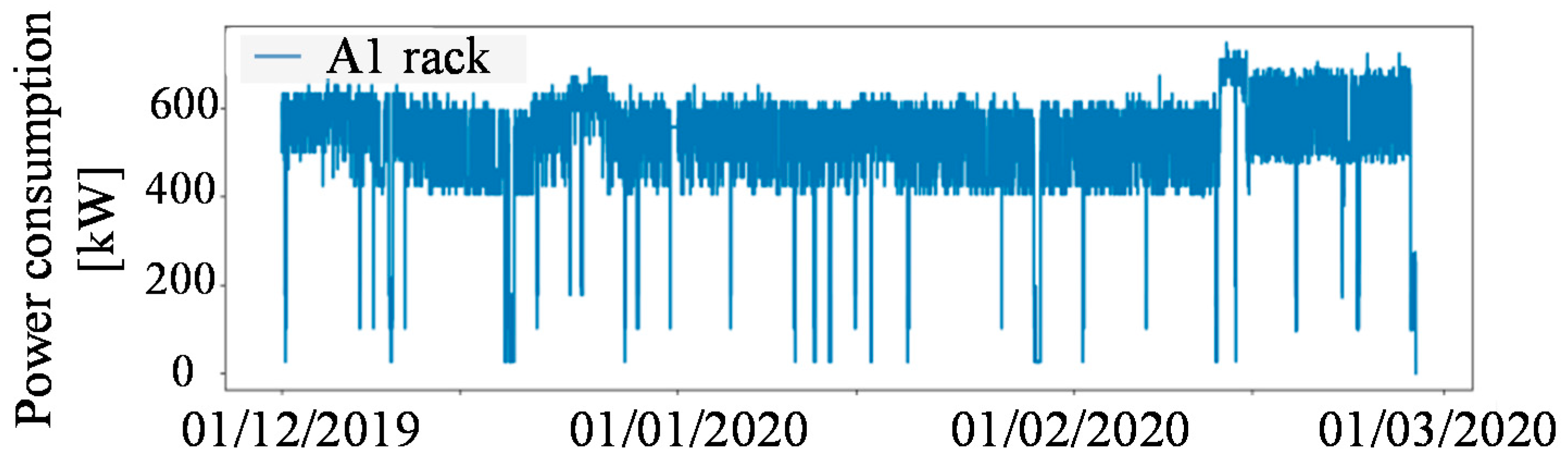

Figure 7.

Power consumption of A1 rack.

Figure 7.

Power consumption of A1 rack.

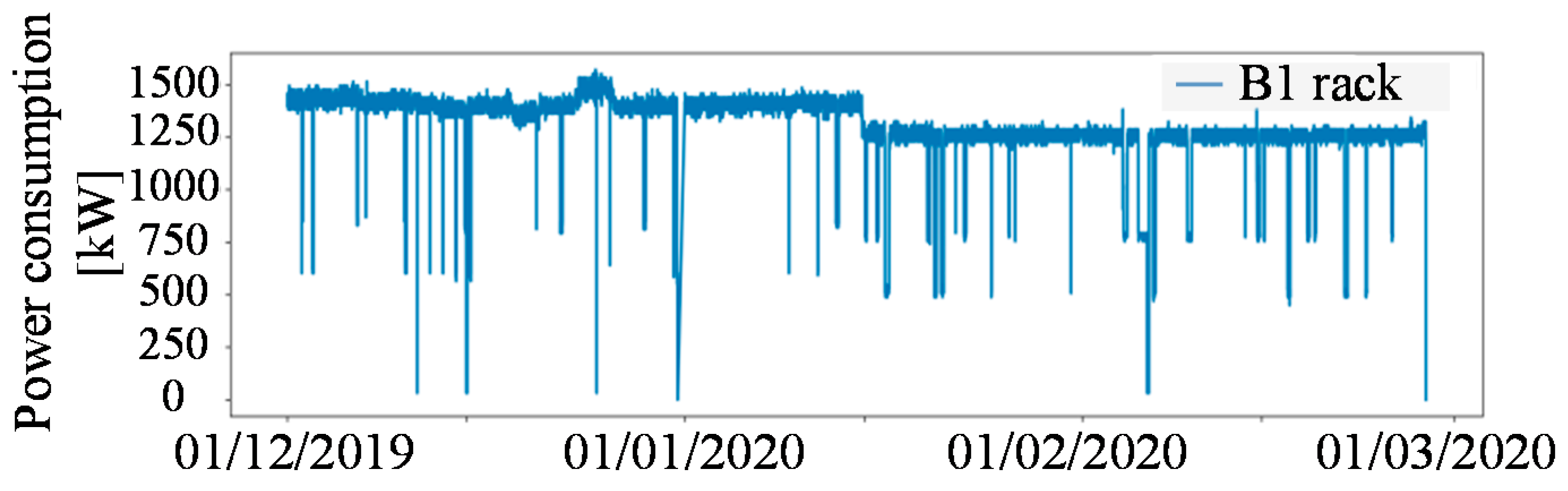

Figure 8.

Power consumption of B1 rack.

Figure 8.

Power consumption of B1 rack.

Figure 9.

Time-series change of rack intake temperature in each rack row. (a) Rack intake temperature in A rack row. (b) Rack intake temperature in B rack row.

Figure 9.

Time-series change of rack intake temperature in each rack row. (a) Rack intake temperature in A rack row. (b) Rack intake temperature in B rack row.

Figure 10.

Time-series change of rack intake temperature in each rack row. (a) Rack intake temperature in C rack row. (b) Rack intake temperature in D rack row.

Figure 10.

Time-series change of rack intake temperature in each rack row. (a) Rack intake temperature in C rack row. (b) Rack intake temperature in D rack row.

Figure 11.

Time-series changes of rack intake temperature classified as above or below 24 °C. (line: average value, over line: mean + standard deviation (SD), under line: mean − SD).

Figure 11.

Time-series changes of rack intake temperature classified as above or below 24 °C. (line: average value, over line: mean + standard deviation (SD), under line: mean − SD).

Figure 12.

Image of gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT).

Figure 12.

Image of gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT).

Figure 13.

Image of blocks (case where only one CRAC is operating).

Figure 13.

Image of blocks (case where only one CRAC is operating).

Figure 14.

Image of blocks (case where both CRACs are operating).

Figure 14.

Image of blocks (case where both CRACs are operating).

Figure 15.

Time-series changes of rack intake temperature in C rack row. (a) Rack intake temperature in C rack row (in the case of one CRAC suddenly stopping while only one CRAC is operating). (b) Rack intake temperature in C rack row (in the case of one CRAC suddenly stopping while two CRACs are operating).

Figure 15.

Time-series changes of rack intake temperature in C rack row. (a) Rack intake temperature in C rack row (in the case of one CRAC suddenly stopping while only one CRAC is operating). (b) Rack intake temperature in C rack row (in the case of one CRAC suddenly stopping while two CRACs are operating).

Table 1.

Specifications of verification server room and computer room air conditioner (CRAC).

Table 1.

Specifications of verification server room and computer room air conditioner (CRAC).

| Item | Data |

|---|

| Room size (m2) | 140 |

| Number of rack for ICT equipment | 26 |

| Number of CRAC | 2 |

| Number of task ambient CRAC | 2 |

| Cooling capacity of CRAC (kW) | 45 |

Table 2.

CRAC operation patterns and stop times.

Table 2.

CRAC operation patterns and stop times.

| The Number of Operation of CRAC | Stopping CRAC | The Number of Experiments Per Stopping Time |

|---|

| 2 min | 5 min | 10 min | 20 min |

|---|

One CRAC suddenly stops

While only one CRAC is operating | CRAC1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| CRAC2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

One CRAC suddenly stops

While both CRACs are operating | CRAC1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| CRAC2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

Table 3.

Range of correlation coefficient in rack row.

Table 3.

Range of correlation coefficient in rack row.

| Row | Range of Correlation Coefficient in Rack Row |

|---|

| A | 0.01~0.32 |

| B | 0.01~0.37 |

| C | 0.01~0.42 |

| D | 0.01~0.27 |

Table 4.

Explanatory variables.

Table 4.

Explanatory variables.

| No | Explanatory Variable |

|---|

| 1 | Elapsed time after CRAC is stopped |

| 2 | Identification of stopping CRAC (CRAC1 or CRAC2) |

| 3 | Identification of rack |

| 4 | Rack intake temperature 1 min before CRAC is stopped |

| 5 | Rack power consumption 1 min before CRAC is stopped |

| 6 | Cooling capacity of CRAC1 1 min before CRAC is stopped |

| 7 | Cooling capacity of CRAC2 1 min before CRAC is stopped |

Table 5.

Outline of each model.

Table 5.

Outline of each model.

| No | Model Name | Description |

|---|

| 1 | Unified model | Construct a unified model without classifying all data. |

| 2 | Models by the number of stopping CRACs | Construct a model that classifies data according to the number of stopping CRACs. |

| 3 | Models by the stopping CRACs | Construct a model that classifies data according to the stopping CRAC (CRAC1 or CRAC2). |

| 4 | Integrated model of Model 2 and Model 3 | Construct a model that classifies data according to the number of stopping CRACs (CRAC1 or CRAC2). |

| 5 | Models by rack | Construct a model for each rack. |

Table 6.

Dataset of block for 5-fold cross-validation.

Table 6.

Dataset of block for 5-fold cross-validation.

| The Number of Operation of CRACs after Experiment | Stopping CRAC | The Number of Blocks |

|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 |

|---|

| The number of CRACs is zero | CRAC1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| CRAC2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| The number of CRACs is one | CRAC1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| CRAC2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

Table 7.

Evaluation index value of each model (all experiment patterns = 60 patterns).

Table 7.

Evaluation index value of each model (all experiment patterns = 60 patterns).

| Model Number (No.) | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| No. 1 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.50 | 2.07 |

| No. 2 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 2.48 |

| No. 3 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 3.78 |

| No. 4 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.53 | 3.33 |

| No. 5 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 3.68 |

Table 8.

Evaluation index value of each model (the case where one CRAC suddenly stops while only one CRAC is operating).

Table 8.

Evaluation index value of each model (the case where one CRAC suddenly stops while only one CRAC is operating).

| Model No. | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| No. 1 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.30 | 2.06 |

| No. 2 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 2.46 |

| No. 3 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 3.26 |

| No. 4 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 3.33 |

| No. 5 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.39 | 3.68 |

Table 9.

Evaluation index value of each model (the case where one CRAC suddenly stops while both CRACs are operating).

Table 9.

Evaluation index value of each model (the case where one CRAC suddenly stops while both CRACs are operating).

| Model No. | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| No. 1 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 2.07 |

| No. 2 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.53 | 2.48 |

| No. 3 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 3.78 |

| No. 4 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 2.87 |

| No. 5 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 2.71 |

Table 10.

Evaluation index value extracting only the data of each model where CRAC1 stopped.

Table 10.

Evaluation index value extracting only the data of each model where CRAC1 stopped.

| Model No. | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| No. 1 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 1.90 |

| No. 2 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 2.46 |

| No. 3 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 3.26 |

| No. 4 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 3.33 |

| No. 5 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 2.66 |

Table 11.

Evaluation index value extracting only the data of each model where CRAC2 stopped.

Table 11.

Evaluation index value extracting only the data of each model where CRAC2 stopped.

| Model No. | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| No. 1 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 2.07 |

| No. 2 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.52 | 2.48 |

| No. 3 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 3.78 |

| No. 4 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 3.15 |

| No. 5 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.49 | 3.68 |

Table 12.

Evaluation index value extracted only for results where the stop time of CRAC is less than 10 min.

Table 12.

Evaluation index value extracted only for results where the stop time of CRAC is less than 10 min.

| Model No. | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| No. 1 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.31 | 1.53 |

| No. 2 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 2.46 |

| No. 3 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 3.78 |

| No. 4 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 3.33 |

| No. 5 | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 2.25 |

Table 13.

Evaluation index value extracted only for results with a stop time of 10 min or more.

Table 13.

Evaluation index value extracted only for results with a stop time of 10 min or more.

| Model No. | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| No. 1 | 0.90 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 2.07 |

| No. 2 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 2.48 |

| No. 3 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 3.26 |

| No. 4 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 2.87 |

| No. 5 | 0.86 | 0.58 | 0.73 | 3.68 |

Table 14.

Feature importance of each explanatory variable.

Table 14.

Feature importance of each explanatory variable.

| No. | Explanatory Variable | Feature Importance |

|---|

| 1 | Elapsed time after CRAC is stopped | 35.69 |

| 2 | Identification of stopping CRAC (CRAC1 or CRAC2) | 5.38 |

| 3 | Identification of rack | 18.91 |

| 4 | Rack intake temperature 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 15.79 |

| 5 | Rack power consumption 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 6.88 |

| 6 | Cooling capacity of CRAC1 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 5.01 |

| 7 | Cooling capacity of CRAC2 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 12.34 |

Table 15.

Evaluation index values when only one of the explanatory variables is used.

Table 15.

Evaluation index values when only one of the explanatory variables is used.

| Model No. | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| Rack intake temperature 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.59 | 3.28 |

| Rack power consumption 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 4.97 |

| Cooling capacity of CRAC1 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 4.51 |

| Cooling capacity of CRAC2 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.73 | 3,38 |

| (Reference) All explanatory variables are used | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 2.48 |

Table 16.

Evaluation values when one of the explanatory variables was deleted.

Table 16.

Evaluation values when one of the explanatory variables was deleted.

| Model No. | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| Rack intake temperature 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 4.38 |

| Rack power consumption 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 2.47 |

| Cooling capacity of CRAC1 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.55 | 2.57 |

| Cooling capacity of CRAC2 1 min before CRAC is stopped | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.47 | 2.49 |

| (Reference) All explanatory variables are used | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 2.48 |

Table 17.

Evaluation index value when the number of training datasets was changed.

Table 17.

Evaluation index value when the number of training datasets was changed.

| Percentage of Dataset | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| 1.0 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 2.48 |

| 0.8 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.59 | 2.76 |

| 0.6 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 2.93 |

| 0.4 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 4.04 |

| 0.2 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 6.54 |

Table 18.

Evaluation values when the CRAC1 dataset was excluded from the training data.

Table 18.

Evaluation values when the CRAC1 dataset was excluded from the training data.

| Excluded Datasets | Stopping CRAC | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| CRAC1 | CRAC1 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 2.41 |

| None (all data is used) | CRAC1 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.55 | 2.46 |

| CRAC1 | CRAC2 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.55 | 2.56 |

| None (all data is used) | CRAC2 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 2.06 |

Table 19.

Evaluation values when the CRAC2 dataset was excluded from the training data.

Table 19.

Evaluation values when the CRAC2 dataset was excluded from the training data.

| Excluded Datasets | Stopping CRAC | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| CRAC2 | CRAC1 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 5.25 |

| None (all data is used) | CRAC1 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.55 | 2.46 |

| CRAC2 | CRAC2 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 4.75 |

| None (all data is used) | CRAC2 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 2.06 |

Table 20.

Evaluation index value when the stopping time of training data was excluded.

Table 20.

Evaluation index value when the stopping time of training data was excluded.

| Stopping Time of Dataset | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| All | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 2.48 |

| Less than ten minutes | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.58 | 3.92 |

| Less than five minutes | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 5.49 |

| Less than two minutes | 0.46 | 0.66 | 1.24 | 6.63 |

Table 21.

Evaluation index based on the time before stopping available.

Table 21.

Evaluation index based on the time before stopping available.

| Available Data | Evaluation Index |

|---|

| R2 | Correct Rate | RMSE | Max Peak Error |

|---|

| 1 min ago | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 2.48 |

| 30 min ago | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.61 | 3.84 |

| 60 min ago | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 3.72 |

| 6 h ago | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 3.88 |

| 24 h ago | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 3.05 |

| 72 h ago | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 4.76 |

| 7 days ago | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 4.48 |