Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Control Scheme for Quadcopter UAVs with a Total Loss of Actuator

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Review

1.2. Main Contributions

2. Quadcopter Modeling

3. Methodology

3.1. Robust Fault Diagnosis using Nonlinear Observer

3.1.1. Fault Diagnosis using Normal Thau Observer Design

3.1.2. Fault Diagnosis Using Adaptive Sliding Mode Thau Observer

3.1.3. Stability Analysis

3.2. Attitude Controller

3.2.1. Modeling of Quadcopter in Faulty Operation

3.2.2. Adaptive Sliding Mode Control for Attitude System

3.3. Position Controller

3.4. Fault-Tolerant Controller

4. Simulation Results

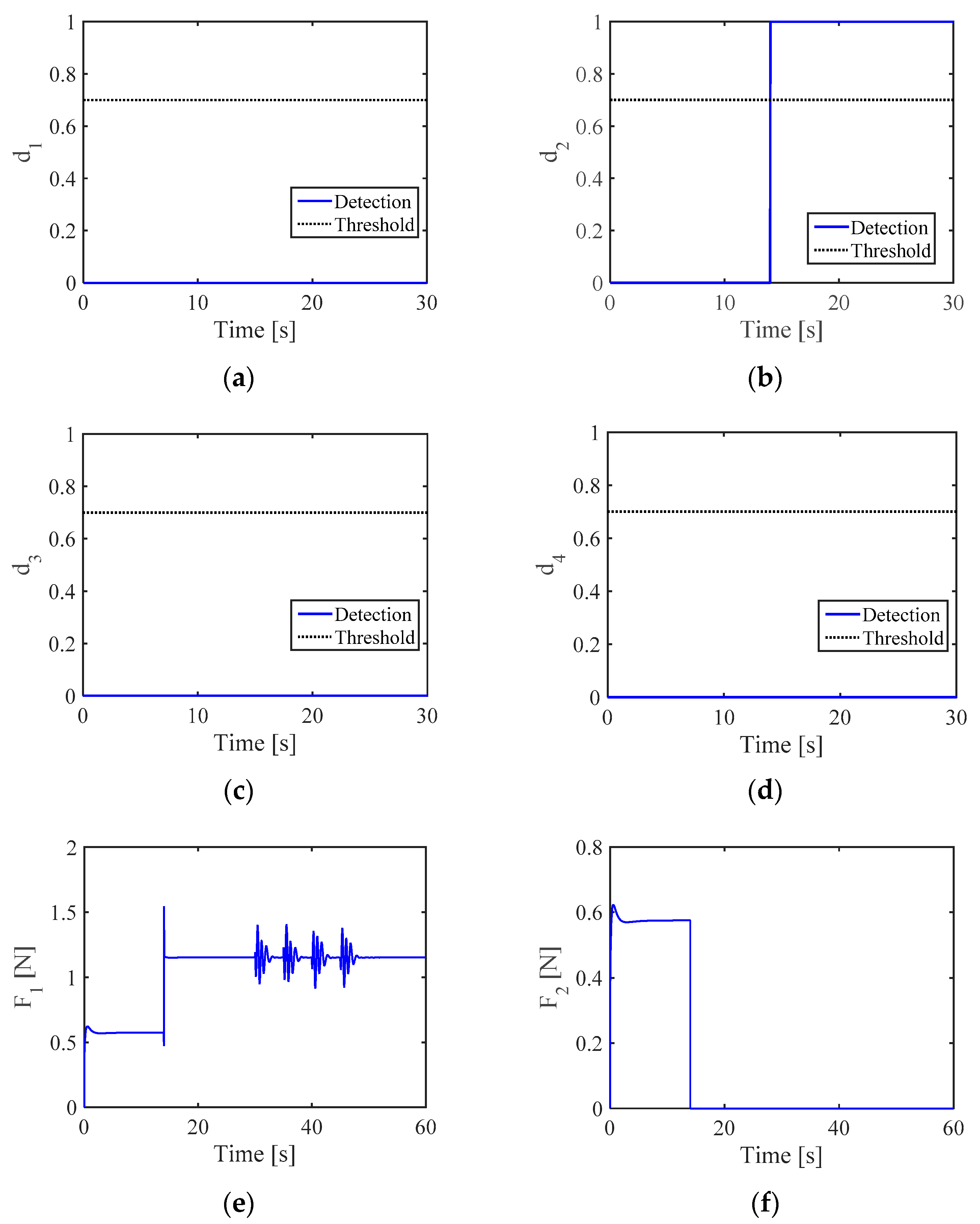

4.1. Fault Diagnosis Results

4.2. Fault-Tolerant Control Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tayebi, A.; MaGilvray, S. Attitude stabilization of a VTOL quadrotor aircraft. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2006, 14, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birk, A.; Wiggerich, B.; Bulow, H.; Pfingsthorn, M.; Schwertfeger, S. Safety, Security, and Rescue missions with an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2011, 64, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdos, D.; Erdos, A.; Watkins, S.E. An experimental UAV system for search and rescue challenge. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2013, 28, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Son, L.H.; Vo, M.T.; Lee, M.Y.; Baik, S.W. A cluster-based boosting algorithm for bankruptcy prediction in a highly imbalanced dataset. Symmetry 2018, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Lee, M.Y.; Park, J.R.; Baik, S.W. Oversampling techniques for bankruptcy prediction: novel features from a transaction dataset. Symmetry 2018, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Chen, T.; Shibasaki, R.; Kumagai, H.; Ahmed, A. UAV-Borne 3-D Mapping System by Multisensor Integration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nex, F.; Remondino, F. UAV for 3D mapping applications: Review. Appl. Geomat. 2014, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippitt, C.D.; Zhang, S. The impact of small unmanned airborne platforms on passive optical remote sensing: A conceptual perspective. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 4852–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, F.; Mirzaei, M.; Gordon, B.W.; Zhang, Y. Fault tolerant control of a quadrotor UAV using sliding mode control. In Proceedings of the Conference on Control and Fault Tolerant Systems, Nice, France, 6–8 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Gordon, B.W. Nonlinear Fault-Tolerant Control of a quadrotor UAV based on sliding mode control technique. In Proceedings of the 8th IFAC Symposium on Fault Detection, Supervision and Safety of Technical Processes (SAFEPROCESS), Mexico City, Mexico, 29–31 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Freddi, A.; Lanzon, A.; Longhi, S. A feedback linearization approach to fault tolerance in quadrotor vehicles. In Proceedings of the 18th World Congress the International Federation of Automatic Control, Milano, Italy, 28 August–2 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour, J.; Aberkane, S.; Ponsart, J.-C. Feedback linearization approach for standard and fault tolerant control: Application to a quadrotor UAV testbed. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 570, 082003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Xiao, B. Adaptive fault tolerant control using integral sliding mode strategy with application to flexible spacecraft. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2013, 44, 2273–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.M. Adaptive sliding mode fault-tolerant control for an unmanned aerial vehicle. Unmanned Syst. 2017, 5, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chamseddine, A. Fault tolerant flight control techniques with application to a quadrotor UAV testbed. In Automatic Flight Control Systems—Latest Developments; Editor, T., Lombaerts, Eds.; Intech: London, UK, 2012; Volume 5, pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Merheb, A.-R.; Noura, H.; Bateman, F. Active fault tolerant control of quadrotor UAV using sliding mode control. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft systems, Orland, FL, USA, 27–30 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Gordon, B.W. Passive and active nonlinear fault-tolerant control of a quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle based on the sliding mode control technique. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 2013, 227, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, J.; Henry, D.; Zolghadri, A. Development of an active fault-tolerant flight control strategy. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2008, 31, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Qi, J.; Theilliol, D.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Song, D.; Hua, C. A review on fault diagnosis and fault tolerant control methods for single-rotor aerial vehicle. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2014, 73, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J. Integrated active fault-tolerant control using IMM approach. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2001, 37, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzon, A.; Freddi, A.; Longhi, S. Flight control of quadrotor vehicle subsequent to a rotor failure. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2014, 37, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.W.; Andrea, R.D. Stability and control of a quadrocopter despite the complete loss of one, two, or three propellers. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lippiello, V.; Ruggiero, F.; Serra, D. Emergency landing for a quadrotor in case of a propeller failure: A backstepping approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Merheb, A.-R.; Noura, H.; Bateman, F. Emergency control of AR Drone Quadrotor UAV suffering a total loss of one rotor. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.; Hong, S.K. Sliding mode Thau observer for actuator fault diagnosis of quadcopter UAVs. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.; Hong, S.K. Robust fault diagnosis for a quadrotor with actuator fault. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 70, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.P.; Hong, S.K. Fault-tolerant control of quadcopter UAVs using robust adaptive sliding mode approach. Energies 2018, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, Z.; Noura, H.; Younes, Y.A. Systematic fault tolerant control based on adaptive Thau observer estimation for quadrotor UAVs. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2015, 25, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freddi, A.; Longhi, S.; Monteriù, A. A model-based fault diagnosis system for a mini-quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on Advanced Control and Diagnosis, Zielona Gora, Poland, 19–20 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, X. Actuator fault estimation for a class of nonlinear descriptor systems. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2014, 45, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, N.P.; Hong, S.K. Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Control Scheme for Quadcopter UAVs with a Total Loss of Actuator. Energies 2019, 12, 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12061139

Nguyen NP, Hong SK. Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Control Scheme for Quadcopter UAVs with a Total Loss of Actuator. Energies. 2019; 12(6):1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12061139

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Ngoc Phi, and Sung Kyung Hong. 2019. "Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Control Scheme for Quadcopter UAVs with a Total Loss of Actuator" Energies 12, no. 6: 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12061139

APA StyleNguyen, N. P., & Hong, S. K. (2019). Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Control Scheme for Quadcopter UAVs with a Total Loss of Actuator. Energies, 12(6), 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12061139