SWOT Analysis for the Promotion of Energy Efficiency in Rural Buildings: A Case Study of China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. RBEE in China

2.1. Characteristics of Rural Residential Buildings

2.2. Current Situation of RBEE

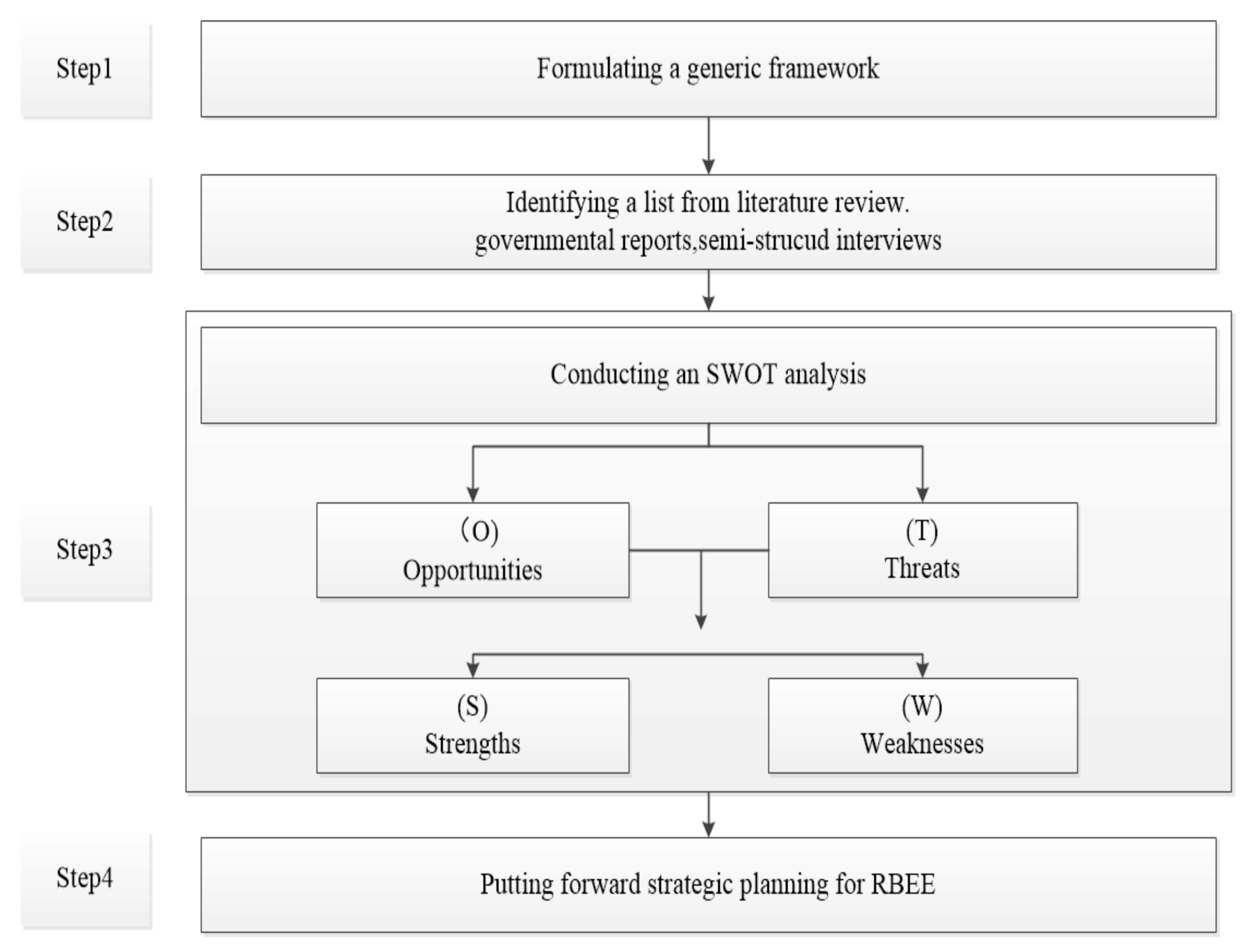

3. Research Methodology

4. SWOT Analysis of RBEE in Rural China

4.1. Opportunities

4.1.1. O1—Top-to-Bottom Policy Support

4.1.2. O2—New Socialist Initiatives in the Countryside

4.1.3. O3—Appeals for Enhancing RBEE

4.2. Threats

4.2.1. T1—Lack of Policies and Standards

4.2.2. T2—Unreasonable Energy Structure

4.2.3. T3—Lack of Supervision Mechanism

4.3. Strengths

4.3.1. S1—Significant Energy Efficiency Potential

4.3.2. S2—Abundant Renewable Energy Resources

4.3.3. S3—Requirements for Improving Living Comfort

4.4. Weaknesses

4.4.1. W1—Poor Energy Efficiency Awareness

4.4.2. W2—Inadequate Knowledge and Information

4.4.3. W3—Low Income of Rural Residents

5. Strategies for Promoting RBEE

5.1. Strategy 1—Formulating a Carrot-and-Stick Policy Governance Mechanism

5.2. Strategy 2—Establishing Technology R&D Institutions in Local Regions

5.3. Strategy 3—Promoting Demonstration Projects of RBEE

5.4. Strategy 4—Carrying out RBEE Training

5.5. Strategy 5—Providing Economic Subsidies

6. Conclusions

Nomenclature List

| BEE | Building energy efficiency |

| RBEE | Rural building energy efficiency |

| SWOT | Strength-weakness-opportunity-threat |

| MOHURD | Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development |

| L | Literature reviews |

| I | Semi-structured interviews |

| G | Governmental reports |

| MOF | Ministry of Finance |

| GOOSC | General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China |

| MOIIT | Ministry of Industry and Information Technology |

| BEERCTU | Building Energy Efficiency Research Center of Tsinghua University |

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, B.J.; Yang, L.; Ye, M.; Mou, B.; Zhou, Y. Overview of rural building energy efficiency in China. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Yu, S.; Song, B.; Deng, Q.; Liu, J.; Delgado, A. Building energy efficiency in rural China. Energy Policy 2014, 64, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 13th Five-Year Plan for Building Energy Saving and Green Building Development. Available online: http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/201703/t20170314_230978.html (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Lu, S.; Tang, X.; Ji, L.; Tu, D. Research on Energy-Saving Optimization for the Performance Parameters of Rural-Building Shape and Envelope by TRNSYS-GenOpt in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone of China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y. Eco-labels and willingness-to-pay: A Hong Kong study. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2012, 1, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H. A SWOT analysis of successful construction waste management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Wang, P.; Li, J.; Yue, G.; Yang, X. Energy and environment in Chinese rural buildings: Situations, challenges, and intervention strategies. Build. Environ. 2015, 91, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.-J.; Yang, L.; Griffy-Brown, C.; Mou, B.; Zhou, Y.-N.; Ye, M. The assessment of building energy efficiency in China rural society: Developing a new theoretical construct. Technol. Soc. 2014, 38, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yin, S. Investigating the critical factors to improve rural buildings energy efficiency. J. Constr. Technol. 2014, 16, 70–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Spaargaren, G.; Mol, A.P.J.; Heerink, N.; Wang, C. Low carbon rural housing provision in China: Participation and decision making. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 35, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Su, F.; Tao, R. Rural residential properties in China: Land use patterns, efficiency and prospects for reform. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, H. Synthetic evaluation of new socialist countryside construction at county level in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2011, 3, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Urbanization for rural sustainability—Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.M.; Chen, G.Q. An overview of energy consumption of the globalized world economy. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 5920–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.M.; Chen, G.Q.; Chen, B. Embodied Carbon Dioxide Emission by the Globalized Economy: A Systems Ecological Input-Output Simulation. J. Environ. Inform. 2015, 21, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.M.; Chen, G.Q.; Zhou, J.B.; Jiang, M.M.; Chen, B. Ecological input–output modeling for embodied resources and emissions in Chinese economy 2005. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2010, 15, 1942–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Q.; Guo, S.; Shao, L.; Li, J.S.; Chen, Z.M. Three-scale input–output modeling for urban economy: Carbon emission by Beijing 2007. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2013, 18, 2493–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chen, G.Q. Multi-scale input-output analysis for multiple responsibility entities: Carbon emission by urban economy in Beijing 2007. J. Environ. Account. Manag. 2013, 1, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Chen, G.Q.; Lai, T.M.; Ahmad, B.; Chen, Z.M.; Shao, L.; Ji, X. Embodied greenhouse gas emission by Macao. Energy Policy 2013, 59, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.Y.; Chen, G.Q.; Shao, L.; Li, J.S.; Alsaedi, A.; Ahmad, B.; Guo, S.; Jiang, M.M.; Ji, X. Embodied energy consumption of building construction engineering: Case study in E-town, Beijing. Energy Build. 2013, 64, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Chen, G.Q.; Chen, Z.M.; Guo, S.; Han, M.Y.; Zhang, B.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Ahmad, B. Systems accounting for energy consumption and carbon emission by building. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2014, 19, 1859–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STDPC. Report on the Development of Chinese Building Energy Conservation; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.Q. SWOT analysis of domestic private enterprises in developing infrastructure projects in China. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2013, 14, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.M.; Kim, H.; Yamaguchi, H. Renewable energy in eastern Asia: Renewable energy policy review and comparative SWOT analysis for promoting renewable energy in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Energy Policy 2014, 74, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, J.O.; Elkarmi, F.; Alasis, E.; Kostas, A. Employment of renewable energy in Jordan: Current status, SWOT and problem analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, A.G.; Dumencu, A.; Atanasiu, M.V.; Panaite, C.E.; Dumitrașcu, G.; Popescu, A. SWOT analysis of the renewable energy sources in Romania—case study: Solar energy. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 147, 012138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Mao, C.; Hou, L.; Wu, C.; Tan, J. A SWOT Analysis for Promoting Off-site Construction under the Backdrop of China’s New Urbanisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 173, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, L. SWOT Analysis for PCDM Development in Building Energy Conservation in China. Energy Procedia 2012, 16, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shen, L.Y.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Drew, D.S. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats for Foreign-Invested Construction Enterprises: A China Study. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2006, 132, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.Y.; Zhao, L.Y.; Liu, Z.L. Influences of new socialist countryside construction on the energy strategy of china and the countermeasures. Energy 2010, 35, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Qin, L. Study on status, trends and development of building energy efficiency in rural areas in Northern China. J. Build. Sci. 2010, 26, 7–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sha, K.; Wu, S. Multilevel governance for building energy conservation in rural China. Build. Res. Inform. 2016, 44, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Si, Y.; Huang, C.; Yang, J.; Huang, B.; Li, W. Present situation and future prospect of renewable energy in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shan, M.; Yang, M.; Yang, X. Development approach and emission reduction potential of energy saving in rural buildings. J. Constr. Technol. 2010, 5, 40–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, B.; Chen, G. Rural energy in China: Pattern and policy. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 2813–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, S.; He, Z.; Shu, W.; Wang, D. Analysis on the difficulties and Countermeasures of energy-saving retrofitting of rural buildings in Chinese hot summer and cold winter areas. Real Estate Biwkly 2017, 9, 204. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wimala, M.; Akmalah, E.; Sururi, M.R. Breaking through the Barriers to Green Building Movement in Indonesia: Insights from Building Occupants. Energy Procedia 2016, 100, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Barriers’ and policies’ analysis of China’s building energy efficiency. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Jiang, Y. Roadmap for China’s Building Energy Conversation; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.-Q.; Liu, C.-X.; Sun, Z.-Y. A survey of China’s low-carbon application practice—Opportunity goes with challenge. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2895–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEECRTU. Research Report on the Annual Development of Chinese Building Energy Conservation; China Architecture &Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Tao, L. Research on Environmental Legal System Innovation in Construction New rural. J. Yunnan Univ. 2011, 24, 78–82. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- BEECRTU. Annual Development Report of Chinese Building Energy Saving; China Architecture &Building Press: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Dong, L.; Duan, H. On Comprehensive Evaluation and Optimization of Renewable Energy Development in China. Resour. Sci. 2011, 33, 431–440. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. Potential Analysis on Energy and Resources of Green Towns in Severe Cold Area. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Industrial University, Harbin, China, June 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S. A Research on Chinese Migrant Workers’ Employment Studys. J. Econ. Theory Manag. Res. 2011, 2, 93–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; He, B.; Jiao, L.; Song, X.; Zhang, X. Research on the development of main policy instruments for improving building energy-efficiency. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillon, L.; Poon, C.S. Sustainable construction aspects of using prefabrication in dense urban environment: A Hong Kong case study. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2008, 26, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cooper, P.; Daly, D.; Ledo, L. Existing building retrofits: Methodology and state-of-the-art. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Wu, Y. Target-oriented obstacle analysis by PESTEL modeling of energy efficiency retrofit for existing residential buildings in China’s northern heating region. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 2098–2101. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, N. Analysis and proposal of implementation effects of heat metering and energy efficiency retrofit of existing residential buildings in northern heating areas of China in “the 11th Five-Year Plan” period. Energy Policy 2012, 45, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatioto, A.; Ciulla, G.; Ricciu, R. An overview of energy retrofit actions feasibility on Italian historical buildings. Energy 2017, 137, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, E. Office building retrofitting strategies: Multicriteria approach of an architectural and technical issue. Energy Build. 2004, 36, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, E.; da Silva, M.G.; Antunes, C.H.; Dias, L. Multi-objective optimization for building retrofit strategies: A model and an application. Energy Build. 2012, 44, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Question | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | What are the opportunities for Rural Building Energy Efficiency (RBEE)? | What are the external prospects that can be taken advantage of for RBEE? |

| What is the governmental guidance for promoting RBEE? | ||

| Q2 | What are the threats to RBEE? | What are the external negative factors that restrict the development of RBEE? |

| Q3 | What are the strengths of RBEE? | What are the benefits of promoting RBEE? |

| Q4 | What are the weaknesses of RBEE? | What are the internal negative factors that restrict the development of RBEE? |

| N | Position | Company | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Project manager | Safety construction company in Changqing County in East China | 1 |

| 2 | Village leader | Zhou Village in Zhangqiu County | 2 |

| 3 | Rural resident | Zhou Village in Zhangqiu County | 2 |

| 4 | Researcher | Shandong Jianzhu University | 1 |

| 5 | Designer | Tong Yuan Design Company | 1 |

| 6 | Green building material supplier | Thermal insulation material company | 1 |

| 7 | Official | Department of Village and Town | 1 |

| 8 | Official | Department of Energy Conservation Science and Technology | 1 |

| Analysis | SWOT | Type | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| “O + T” Analysis | O1—top-to-bottom policy support | G | MOHURD, 13th Five-Year for Building Energy-Saving and Green Building Plan (2016–2020) |

| O2—new socialist initiatives in the countryside | G, L | Yang, et al. [30], Proposal of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party for the 11th Five-Year Plan for national economic and social development | |

| O3—appeals for enhancing RBEE | G, L | Wu, et al. [31], Development of Chinese BEE Report in 2016 | |

| T1—lack of policies and standards | L, I | Sha and Wu [32] | |

| T2—unreasonable energy structure | L, I, G | Zhang, et al. [33], Guidance on Expanding BEE Pilot Project in 2009, official from the Department of Energy Conservation Science and Technology | |

| T3—lack of supervising mechanism | I, G | An official from the Department of Village and Town, 13th Five-Year Plan for Building Energy-Saving and Green Building Development | |

| “S + W” Analysis | S1—significant energy efficiency potential | L, I, G | He, Yang, Ye, Mou and Zhou [1], Li, et al. [34], an official from the Department of Village and Town, notice of carrying out the green rural housing construction in 2013 |

| S2—abundant renewable energy resources | L, G | Zhang, et al. [35], Development of Chinese BEE Report in 2016 | |

| S3—requirements for improving living comfort | L, I | Wu, Liu and Qin [31], rural resident, village leaders | |

| W1—poor building energy-saving consciousness | L, I | Ai, et al. [36], an official from the Department of Village and Town in Shandong Province | |

| W2—inadequate knowledge and information | L, I | Wimala, et al. [37], village leaders | |

| W3—low-income level of rural residents | L, I | Sha and Wu [32], village leaders |

| Year | Regulations | Issuers | Contents Regarding RBEE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Accelerating the implementation of renewable energy building applications in rural areas | MOF, MOHURD | Renewable energy resources used in rural schools, rural residential buildings, village or town governmental offices, and health centers |

| 2009 | Guidance on Expanding BEE Pilot Project for Dangerous Rural Reconstruction | MOHURD | Focusing on energy-saving measures for building envelopes in walls, doors, roofs, and windows to improve the thermal comfort of rural residential buildings |

| 2013 | Green Building Action Plan | Office of the State Council | Promoting green rural housing construction, preparing technical guides for green buildings in villages or towns, freely providing technical services |

| 2013 | Notice of carrying out green rural housing construction | MOIIT, MOHURD | Exploring green rural housing construction method and technology; popularizing native green buildings; promoting green building materials to the countryside; demonstrating project of green rural housing |

| 2015 | Action Plan to Promote the Production and Application of Green Building Materials | MOIIT, MOHURD | Promoting green building materials to the countryside; preparing a green material product catalog for green rural housing |

| 2017 | 13th Five-Year Plan for Building Energy-Saving and Green Building Development | MOHURD | Economically developed areas and key development areas should make a breakthrough in RBEE, and the proportion of energy-saving measures should be over 10% |

| Environment | Planning | |

|---|---|---|

| External Environment | Opportunities (O) | 1. Top-to-bottom policy support; 2. Construction of new socialist initiatives in the countryside; 3. Appeals for enhancing RBEE. |

| Threats (T) | 1. Lack of policies and standards; 2. Unreasonable energy structure; 3. Lack of supervision mechanism. | |

| Internal Environment | Strengths (S) | 1. Significant energy efficiency potential; 2. Abundant renewable energy resources; 3. Requirements for improving living comfort. |

| Weaknesses (W) | 1. Poor energy efficiency awareness; 2. Inadequate knowledge and information; 3. Low income of rural residents. | |

| SO strategies | S2: Establishing technology Research and Development (R&D) institutions in local regions; S3: Promoting demonstration projects of RBEE. | |

| WO strategies | S4: Carrying out RBEE training; S5: Providing economic subsidies to rural residents. | |

| ST strategies | S1: Formulating a carrot-and-stick policy governance mechanism; S3: Promoting demonstration projects of RBEE. | |

| WT strategies | S1: Formulating a carrot-and-stick policy governance mechanism; S5: Providing economic subsidies to rural residents. | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Guo, S.; Wu, Z.; Alsaedi, A.; Hayat, T. SWOT Analysis for the Promotion of Energy Efficiency in Rural Buildings: A Case Study of China. Energies 2018, 11, 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11040851

Zhang L, Guo S, Wu Z, Alsaedi A, Hayat T. SWOT Analysis for the Promotion of Energy Efficiency in Rural Buildings: A Case Study of China. Energies. 2018; 11(4):851. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11040851

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lin, Shan Guo, Zezhou Wu, Ahmed Alsaedi, and Tasawar Hayat. 2018. "SWOT Analysis for the Promotion of Energy Efficiency in Rural Buildings: A Case Study of China" Energies 11, no. 4: 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11040851

APA StyleZhang, L., Guo, S., Wu, Z., Alsaedi, A., & Hayat, T. (2018). SWOT Analysis for the Promotion of Energy Efficiency in Rural Buildings: A Case Study of China. Energies, 11(4), 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11040851