The Influence of Party Organization Involvements in Corporate Governance on Innovation: Evidence from China’s Private-Owned Enterprises

Abstract

:1. Introduction

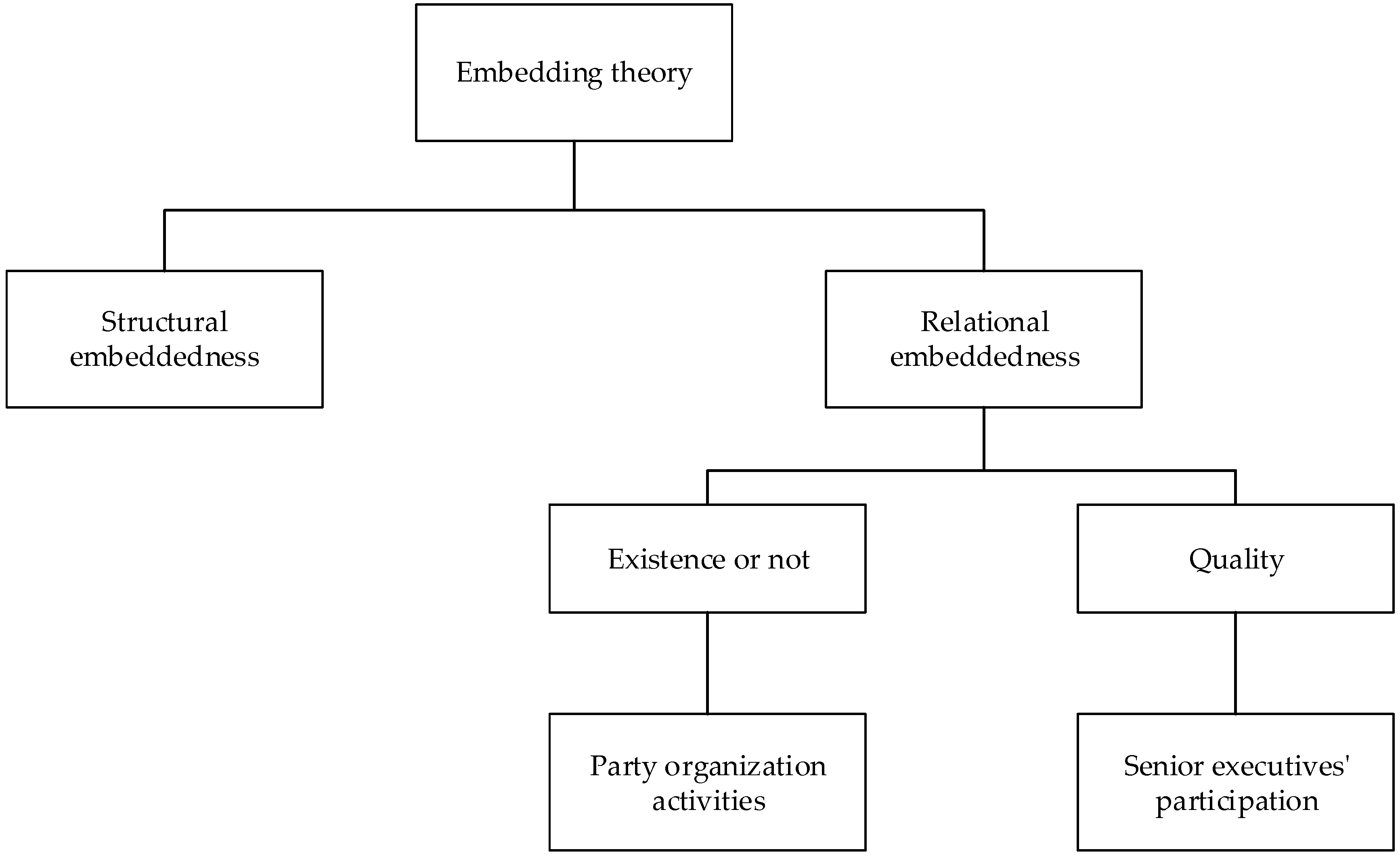

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Party Organization Involvements in Corporate Governance and POEs’ Innovation

2.2. The Mechanisms of the Party Organization Involvements Affecting POEs’ Innovation

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

3.2. Model Setting and Variable Definition

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Variables

4.2. Results of Regression Analysis

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. PSM Sample Selection

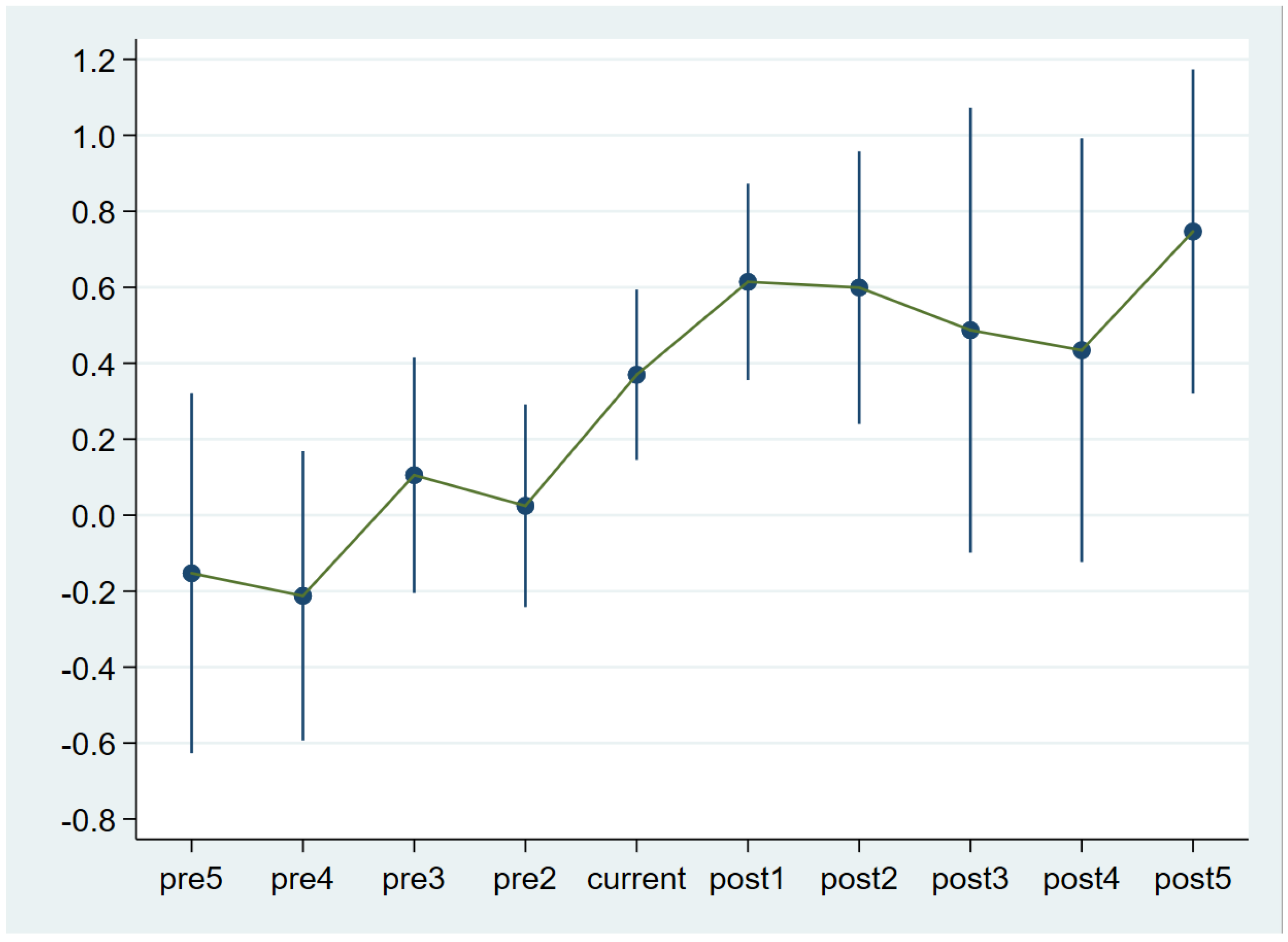

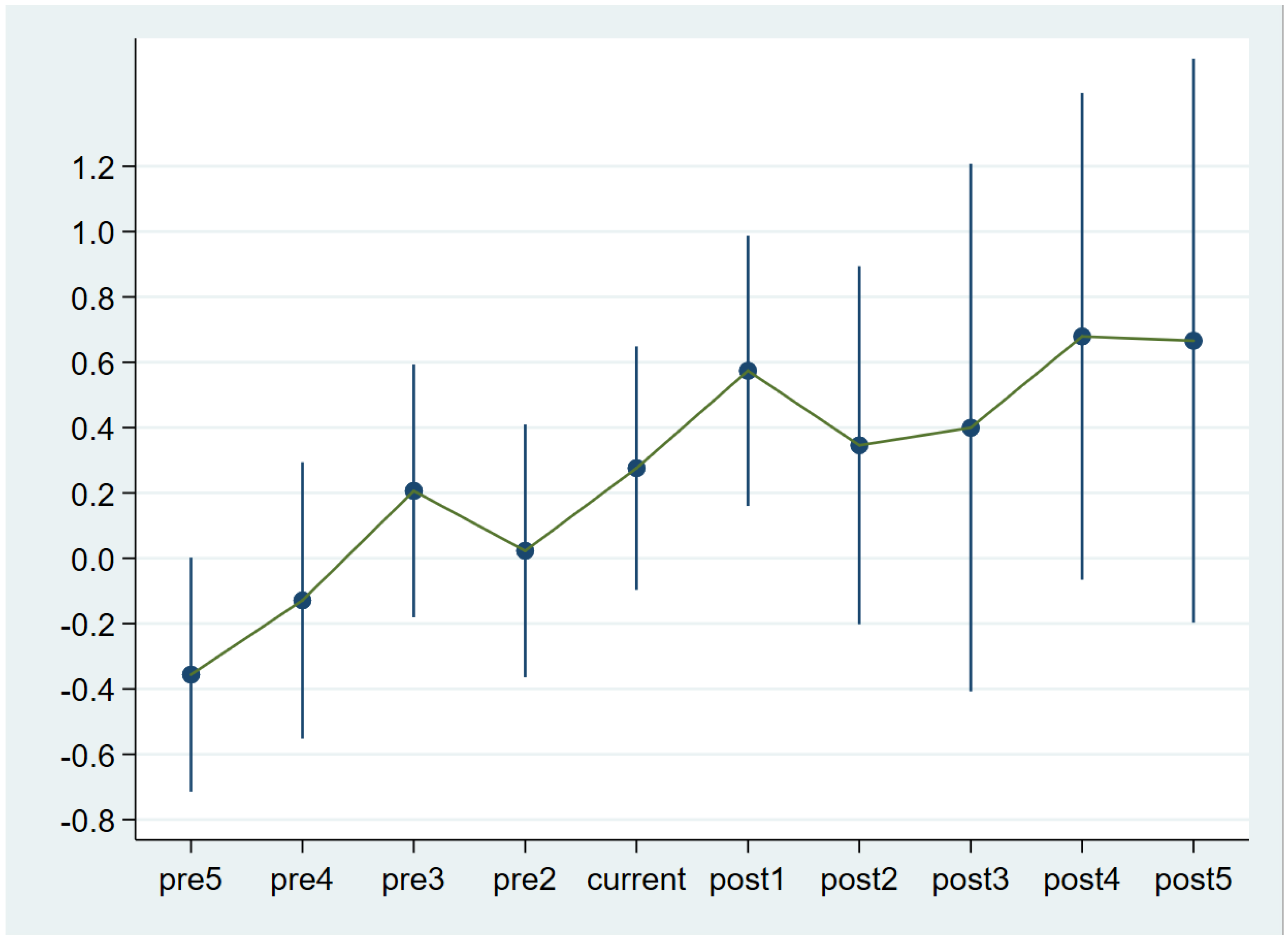

4.3.2. DID Analysis

4.3.3. Substituting the Dependent Variable

5. Further Exploration

5.1. Analysis of Probable Mechanisms

5.1.1. R&D Investment

5.1.2. Operating Risk

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.2.1. Party Organization Involvements, Family Businesses, and Corporate Innovation

5.2.2. Party Organization Involvements, Government Subsidies, and Corporate Innovation

5.2.3. Party Organization Involvements, Factor Intensity, and Corporate Innovation

5.2.4. Party Organization Involvements, Spatial Distribution, and Corporate Innovation

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Full Term | Abbreviation | Number | Full Term | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Private-owned enterprises | POEs | 16 | propensity score matching | PSM |

| 2 | State-owned enterprises | SOEs | 17 | difference-in-differences | DID |

| 3 | Research and development | R&D | 18 | Return on operating cash flow | OCF |

| 4 | Communist party of China | CPC | 19 | Growth rate of operating revenue | Growth |

| 5 | The board chairman or CEO of an enterprise participates in activities | Senior executives’ participation (Participate) | 20 | Current ratio | CR |

| 6 | Party organization activities | Party | 21 | Total assets | TA |

| 7 | Non-invention application | InApply | 22 | Debt to asset ratio | Lever |

| 8 | Utility model application | UApply | 23 | Proportion of independent directors | Director |

| 9 | Design application | DApply | 24 | Duality of the chairman of the board and CEO | Merge |

| 10 | Age of listed company | Age | 25 | Operating risk | Roabd |

| 11 | Shareholding of the largest shareholder | First | 26 | Family firm | Family |

| 12 | Number of directors | Bd | 27 | Government grants | dbGover |

| 13 | Control group | Treat | 28 | Factor industry classification | Factor |

| 14 | Eastern, central and western region | Fdzx | 29 | Northern, southern region | Fnb |

| 15 | Industry | Ind | 30 | Region | Area |

| Full Sample: 2003–2017 | |||||

| Non Participation of the Senior Executives | Participation of the Senior Executives | t-Value | |||

| Observed Value | Mean Value | Observed Value | Mean Value | ||

| Age | 7101 | 6.1917 | 313 | 8.5591 | −2.3674 *** |

| CR | 7101 | 0.0318 | 313 | 0.0224 | 0.0094 *** |

| TA | 7101 | 9.3956 | 313 | 9.6310 | −0.2430 *** |

| Lever | 7101 | 0.3657 | 313 | 0.4073 | −0.0416 *** |

| OCF | 7101 | 0.0443 | 313 | 0.0514 | −0.0071 * |

| Growth | 7101 | 0.3413 | 313 | 0.2183 | 0.1230 |

| First | 7101 | 0.3336 | 313 | 0.3134 | 0.0202 ** |

| Bd | 7101 | 10.4784 | 313 | 11.3003 | −0.8219 *** |

| Director | 7101 | 0.3849 | 313 | 0.3718 | 0.0132 ** |

| Merge | 7101 | 0.3725 | 313 | 0.2620 | 0.1105 *** |

| Subsample 1: 2003–2011 | |||||

| Non Participation of the Senior Executives | Participation of the Senior Executives | t-Value | |||

| Observed value | mean value | Observed value | mean value | ||

| Age | 1768 | 5.5764 | 48 | 6.8542 | −1.2778 ** |

| CR | 1768 | 0.0295 | 48 | 0.0186 | 0.0109 |

| TA | 1768 | 9.2434 | 48 | 9.4721 | −0.2288 *** |

| Lever | 1768 | 0.4139 | 48 | 0.4629 | −0.0489 * |

| OCF | 1768 | 0.0416 | 48 | 0.0601 | −0.0185 |

| Growth | 1768 | 0.3582 | 48 | 0.2395 | 0.1187 |

| First | 1768 | 0.3410 | 48 | 0.3123 | 0.0287 |

| Bd | 1768 | 11.0096 | 48 | 12.0833 | −1.0737 ** |

| Director | 1768 | 0.3584 | 48 | 0.3499 | 0.0086 |

| Merge | 1768 | 0.2777 | 48 | 0.2292 | 0.0485 |

| Subsample 2: 2012–2017 | |||||

| Non Participation of the Senior Executives | Participation of the Senior Executives | t-Value | |||

| Observed Value | Mean Value | Observed Value | Mean Value | ||

| Age | 5333 | 6.3956 | 265 | 8.8679 | −2.4723 *** |

| CR | 5333 | 0.0326 | 265 | 0.0231 | 0.0095 *** |

| TA | 5333 | 9.4461 | 265 | 9.6687 | −0.2226 *** |

| Lever | 5333 | 0.3498 | 265 | 0.3973 | −0.0475 *** |

| OCF | 5333 | 0.0452 | 265 | 0.0498 | −0.0046 |

| Growth | 5333 | 0.3357 | 265 | 0.2144 | 0.1213 |

| First | 5333 | 0.3311 | 265 | 0.3136 | 0.0175 ** |

| Bd | 5333 | 10.3023 | 265 | 11.1585 | −0.8562 *** |

| Director | 5333 | 0.3937 | 265 | 0.3757 | 0.0180 *** |

| Merge | 5333 | 0.4039 | 265 | 0.2679 | 0.1360 *** |

| Full sample: 2003–2017 | |||||||||

| Apply | IApply | InApply | |||||||

| NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | |

| ATT difference | 0.1920 * | 0.1940 *** | 0.2420 *** | 0.1180 | 0.1540 ** | 0.1920 ** | 0.2450 ** | 0.1730 ** | 0.2240 *** |

| (1.95) | (2.65) | (3.35) | (1.15) | (2.00) | (2.53) | (2.11) | (2.00) | (2.63) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Subsample 1: 2003–2011 | |||||||||

| Apply | IApply | InApply | |||||||

| NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | |

| ATT difference | 0.0640 | 0.1750 | 0.2230 | 0.0260 | 0.0020 | −0.0490 | 0.0020 | 0.2130 | 0.3250 |

| (0.28) | (1.00) | (1.40) | (0.11) | (0.01) | (−0.28) | (0.01) | (0.99) | (1.64) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Subsample 2: 2012–2017 | |||||||||

| Apply | IApply | InApply | |||||||

| NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | |

| ATT difference | 0.1500 | 0.1980 ** | 0.2150 *** | 0.2030 * | 0.1960 ** | 0.2150 *** | 0.0470 | 0.1590 * | 0.1760 * |

| (1.34) | (2.40) | (2.65) | (1.77) | (2.32) | (2.59) | (0.37) | (1.65) | (1.83) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Panel A: The Intermediary Effect of R & D Investment | |||||||

| Variable Name | Coefficient | Estimation Standard Error | t-Value | p > |t| | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| The effect of the Participate on Apply | Executive | 0.172 | 0.063 | 2.72 | 0.007 | 0.048 | 0.297 |

| The effect of the Participate on Input | Executive | 0.157 | 0.051 | 3.08 | 0.002 | 0.057 | 0.257 |

| The effect of the Participate on Input and Apply | Input | 0.352 | 0.015 | 23.10 | 0.000 | 0.322 | 0.382 |

| Executive | 0.117 | 0.061 | 1.92 | 0.055 | −0.002 | 0.236 | |

| Panel B: The Intermediary Effect of Operating Risk | |||||||

| Variable Name | Coefficient | Estimation Standard Error | t-Value | p > |t| | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| The effect of the Participate on Apply | Executive | 0.211 | 0.098 | 2.16 | 0.031 | 0.020 | 0.403 |

| The effect of the Participate on operating risk | Executive | −0.004 | 0.003 | −1.54 | 0.125 | −0.010 | 0.001 |

| The effect of Participate on operating risk and Apply | Roabd | −2.377 | 0.488 | −4.87 | 0.000 | −3.334 | −1.420 |

| Executive | 0.201 | 0.098 | 2.06 | 0.040 | 0.009 | 0.392 | |

| Panel A: Sobel Test of the Intermediary Effect of R&D Investment | ||||

| Coefficient | Estimation Standard Error | Z-Value | p > |z| | |

| Sobel | 0.0541 | 0.0239 | 2.2620 | 0.0237 |

| Goodman-1 (Aroian) | 0.0541 | 0.0239 | 2.2610 | 0.0238 |

| Goodman-2 | 0.0541 | 0.0239 | 2.2640 | 0.0236 |

| Panel B: Sobel Test of Intermediary Effect of Enterprise Operating Risk | ||||

| Coefficient | Estimation Standard Error | Z-Value | p > |z| | |

| Sobel | 0.0106 | 0.0072 | 1.464 | 0.1431 |

| Goodman-1 (Aroian) | 0.0106 | 0.0073 | 1.437 | 0.1507 |

| Goodman-2 | 0.0106 | 0.0071 | 1.493 | 0.1353 |

| Family Enterprise | Non Family Enterprise | Government Subsidies Are above Average | Government Subsidies Are below Average | Labour- Intensive | Capital- Intensive | Technology-Intensive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Apply | Apply | Apply | |||||

| Participate | 0.1787 *** | 0.2418 | 0.2003 ** | 0.1388 | 0.1351 | 0.2128 * | 0.1584 * |

| (2.72) | (0.48) | (2.39) | (1.37) | (0.89) | (1.82) | (1.72) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Intercept | −10.9400 *** | −11.1690 * | −11.4435 *** | −6.6425 *** | −6.7879 *** | −6.9829 *** | −12.9187 *** |

| (−22.85) | (−1.87) | (−15.58) | (−9.30) | (−6.73) | (−8.41) | (−25.05) | |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 5504 | 94 | 2841 | 2697 | 857 | 1450 | 3291 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3461 | 0.564 | 0.3819 | 0.2495 | 0.3144 | 0.2466 | 0.3824 |

| Northern Region | Southern Region | Eastern Region | Central Region | West Region | Yangtze River Delta | Pearl River Delta | Beijing Tianjin Hebei Region | Other Regions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Apply | Apply | Apply | |||||||

| Participate | 0.4426 *** | −0.0473 | 0.1547 * | 0.0729 | 0.2803 | 0.2588 *** | −0.1889 | 0.6897 ** | 0.1749 * |

| (4.63) | (−0.53) | (1.80) | (0.61) | (1.31) | (2.71) | (−0.79) | (2.04) | (1.74) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Intercept | −12.6417 *** | −10.7056 *** | −12.5667 *** | −7.7520 *** | −12.0202 *** | −9.7860 *** | −14.7859 *** | −14.7667 *** | −9.7684 *** |

| (−18.31) | (−15.53) | (−22.47) | (−7.05) | (−7.06) | (−8.64) | (−11.41) | (−9.20) | (−13.35) | |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 2452 | 3146 | 4233 | 915 | 450 | 2139 | 1007 | 588 | 1864 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3823 | 0.3749 | 0.3711 | 0.4057 | 0.4474 | 0.3850 | 0.4731 | 0.4825 | 0.3402 |

References

- Xiaoyang, J.; Sheng, L. A factor market distortion research based on enterprise innovation efficiency of economic kinetic energy conversion. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 44, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshirian, F.; Tian, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W. Stock market liberalization and innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 139, 985–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Teng, T. R&D internationalization and innovation performance of Chinese enterprises: The mediating role of returnees and foreign professionals. Growth Chang. 2021, 52, 2194–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Sun, X. Does internationalization strategy promote enterprise innovation performance?—The moderating effect of environmental complexity. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 43, 1721–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J. Higher education and corporate innovation. J. Corp. Finance 2022, 72, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shan, Y.; Tian, G.; Hao, X. Labor cost, government intervention, and corporate innovation: Evidence from China. J. Corp. Finance 2020, 64, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tian, X. Finance and Corporate Innovation: A Survey. Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2018, 47, 165–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amore, M.D.; Schneider, C.; Žaldokas, A. Credit supply and corporate innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 109, 835–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-H.; Tian, X.; Xu, Y. Financial development and innovation: Cross-country evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 2014, 112, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, T.; Jian, Z. Corruption pays off: How environmental regulations promote corporate innovation in a developing country. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Smith, J.; White, R. Corruption and corporate innovation. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2020, 55, 2124–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Martinsson, G.; Petersen, B.C. Law, stock markets, and innovation. J. Financ. 2013, 68, 1517–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fang, L.H.; Lerner, J.; Wu, C. Intellectual property rights protection, ownership, and innovation: Evidence from China. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2017, 30, 2446–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, Y.; Xiong, G.; Mardani, A. Environmental information disclosure and corporate innovation: The “Inverted U-shaped” regulating effect of media attention. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Wang, C.; Liao, J.; Fang, Z.; Cheng, F. Economic policy uncertainty exposure and corporate innovation investment: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Financ. J. 2021, 67, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Hou, F. Trade policy uncertainty and corporate innovation evidence from Chinese listed firms in new energy vehicle industry. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Lee, C.-C.; Zhou, F. How does fiscal policy uncertainty affect corporate innovation investment? Evidence from China’s new energy industry. Energy Econ. 2021, 105, 105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.S.; Huang, C.W.; Hwang, C.Y.; Wang, Y. Voluntary disclosure and corporate innovation. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2022, 58, 1081–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Gao, X.; Billings, B.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Technological Innovation. J. Manag. Account. Res. 2021, 34, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhu, Z. The effect of ESG rating events on corporate green innovation in China: The mediating role of financial constraints and managers’ environmental awareness. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, M.D.; Bennedsen, M. Corporate governance and green innovation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2016, 75, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, V.S. Corporate Governance and CEO Innovation. Atl. Econ. J. 2017, 46, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio-López, D.; Cabeza-García, L.; González-Álvarez, N. Corporate governance and innovation: A theoretical review. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 28, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Mbanyele, W.; Sun, J. Managerial R&D hands-on experience, state ownership, and corporate innovation. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 72, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Ke, Y.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, Y. CEO Foreign Experience and Green Innovation: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Wen, W. Managerial foreign experience and corporate innovation. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 48, 752–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Wu, Q. Board Networks and Corporate Innovation. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 3618–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, A.M.; Wang, B.; Wang, X. Shareholder coordination and corporate innovation. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2020, 47, 730–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Zheng, Y. The impact of chief executive officers’ (CEOs’) overseas experience on the corporate innovation performance of enterprises in China. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Kim, C. Employment stability and corporate innovation. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2020, 27, 1722–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.X.; Weathers, J. Employee treatment and firm innovation. J. Bus. Finance Account. 2019, 46, 977–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Yuan, Q.B. Institutional investors’ corporate site visits and corporate innovation. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 48, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Reenen, J.V.; Zingales, L. Innovation and institutional ownership. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lerner, J.; Wulf, J. Innovation and Incentives: Evidence from Corporate R&D. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2007, 89, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Yan, Y.; Hao, J.; Wu, J. Retail investor attention and corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2022, 115, 106308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloc, F. Corporate governance and innovation: A survey. J. Econ. Surv. 2011, 26, 835–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. China’s government spending and global inflation dynamics: The role of the oil price channel. Energy Econ. 2022, 110, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrala, R.; Orlandi, F. Win-win? Assessing the global impact of the Chinese economy. Asia Glob. Econ. 2021, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The Influence of Party Organization’s Participation in External Governance on the Innovation of China’s State-Owned Enterprises. Open J. Political Sci. 2020, 10, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.; Cheng, H.Y. Participation of communist party organizations in corporate governance and innovation: Empirical evidence from listed state-owned enterprises. J. Syst. Manag. 2021, 30, 401–422. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.I. Chinese communist party’s grass-roots organizations in enterprises since the 1990s: Changes and challenges. East Asian Policy 2019, 11, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Lin, B.; Li, J. Political Control, Corporate Governance and Firm Value: The Case of China. J. Corp. Financ. 2022, 72, 102161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opper, S.; Wong, S.M.L.; Hu, R.Y. Party power, market and private power: Chinese Communist Party persistence in China’s listed companies. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2002, 19, 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, M. How do Party organizations’ boundary-spanning behaviors control worker unrest? A case study on a Chinese resource-based state-owned enterprise. Empl. Relat. 2017, 39, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, W.R.; Davis–Sramek, B.; Baucus, M.S.; Germain, R.N. Commitment in Franchising: The Role of Collaborative Communication and a Franchisee’s Propensity to Leave. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Furuoka, F.; Idris, A. Mapping the relationship between transformational leadership, trust in leadership and employee championing behavior during organizational change. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2021, 26, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinaghian, L.; Kim, Y.; Srai, J. A relational embeddedness perspective on dynamic capabilities: A grounded investigation of buyer-supplier routines. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 85, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Rennings, K. Environmental innovation and employment dynamics in different technology fields—An analysis based on the German Community Innovation Survey 2009. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gimmon, E.; Teng, Y.; He, X. Political embeddedness and multi-layered interaction effects on the performance of private enterprises: Lessons from China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2021, 16, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.C.; Wong, S. Political control and performance in China’s listed firms. J. Comp. Econ. 2004, 32, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K.I.; Brødsgaard, K.E. Corporate Governance with Chinese Characteristics: Party Organization in State-owned Enterprises. China Q. 2022, 250, 486–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Luo, Z.; Wei, X. Social insurance with Chinese characteristics: The role of communist party in private firms. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 37, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, L.-A. Political connections, financing and firm performance: Evidence from Chinese private firms. J. Dev. Econ. 2008, 87, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xu, X. The role of communist party branch in employment protection: Evidence from Chinese private firms. Asia-Pacific J. Account. Econ. 2021, 29, 1518–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Xie, J.D.; Yuan, W. The CPC Party organizations in privately-controlled firms and earnings management. China J. Account. Studies 2019, 7, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haveman, H.A.; Jia, N.; Shi, J. The dynamics of political embeddedness in China. Adm. Sci. Q. 2016, 62, 67–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Chan, K.C. Communist party control and stock price crash risk: Evidence from China. Econ. Lett. 2016, 141, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, J.; Deng, Y.; Bordignon, M. The rise of red private entrepreneurs in China: Policy shift, institutional settings and political connection. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 61, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Li, A.; Ke, J.; Yuan, J. The governance role of corporate party organization on innovation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, C.; Liu, D. Political Party System and Enterprise Innovation: Is China Different? Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beladi, H.; Hou, Q.; Hu, M. The party school education and corporate innovation: Evidence from SOEs in China. J. Corp. Finance 2022, 72, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.L.; Shang, D.; Pan, L.L. Embedding of party organizations and innovation investment of private enterprises: Micro evidence from the national survey of private enterprises. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 44, 99–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J.R. Does the pay gap in the top management team incent enterprise innovation?—Based on property rights and financing constraints. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 1290–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Yang, R.L.; Yang, J.D. Anti-corruption and firm’s innovations: An explanation from political connections. China Ind. Econ. 2015, 7, 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, K.; Stiglitz, J.E.; Block, F.L. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, 2nd ed.; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R. Alliances and networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.; Behrens, D.; Krackhardt, D. Redundant governance structures: An analysis of structural and relational embeddedness in the steel and semiconductor industries. Strat. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B. Social structure and competition in interfirm net-works: The paradox of embeddedness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhu, P. The impact of organisational ageing and political connection on organisation technology innovation: An empirical study of IT industry and pharmaceutical industry in China. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2014, 22, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.-C.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, C. Political connections, network centrality and firm innovation. Finance Res. Lett. 2019, 28, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M. Politically connected firms. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, J.; Li, M.; Mao, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, J. The impact of network embeddedness on radical innovation performance-intermediators of innovation legitimacy and resource acquisition. Int. J. Technol. Policy Manag. 2017, 17, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, O.; Yue, H.; Zhong, Q. China’s Anti-Corruption Campaign and Financial Reporting Quality. Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 37, 1015–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Sevilir, M. Board connections and M&A transactions. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 103, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L. Building the Rule of Law in China; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Griliches, Z. Patent Statistics as Economic Indicators: A Survey. J. Econ. Lit. 1990, 28, 1661–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Cornaggia, J.; Mao, Y.; Tian, X.; Wolfe, B. Does banking competition affect innovation? J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. How does stock market liberalization influence corporate innovation? Evidence from Stock Connect scheme in China. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2020, 47, 100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.W.; He, W.; He, Z.L.; Lu, J. Patent regime shift and firm innovation: Evidence from the second amendment to China’s patent law. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2014, 2014, 14174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovtchinnikov, A.V.; Reza, S.W.; Wu, Y. Political Activism and Firm Innovation. J. Financial Quant. Anal. 2019, 55, 989–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.L.; Xu, Y. Outspoken Insiders: Political Connections and Citizen Participation in Authoritarian China. Political Behav. 2017, 40, 629–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, M. Conducting R&D in Countries with Weak Intellectual Property Rights Protection. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozi’c, L.; Rajh, E. The factors constraining innovation performance of SMEs in Croatia. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istrazivanja 2016, 29, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koeller, C.T. Innovation, market structure and firm size: A simultaneous equations model. Manag. Decis. Econ. 1995, 16, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griliche, Z. Productivity, R&D, and basic research at the firm level in the 1970′s. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, C. Can Bank Debt Governance and Internal Governance Promote Enterprise Innovation? Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 139, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Nugent, J.B. Coordinating China’s economic growth strategy via its government-controlled association for private firms. J. Comp. Econ. 2018, 46, 1273–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. Research on Corporate Governance of Party Organizations Participating in the Reform of Mixed Ownership of State-owned Enterprises from the Perspective of Organization Structure—Based on the CSME Analysis Framework. 2019. Available online: https://webofproceedings.org/proceedings_series/article/artId/9871.html (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Kacperczyk, A.; Beckman, C.M.; Moliterno, T.P. Disentangling risk and change: Internal and external social comperison in the mutual fund industry. Adm. Sci. Q. 2015, 60, 28–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Jiang, F.; Wu, S.-Y. Does short-maturity debt discipline managers? Evidence from cash-rich firms’ acquisition decisions. J. Corp. Finance 2018, 53, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.J. Organization embedding and financial violation. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 228–243+253. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Boubakri, N.; Cosset, J.-C.; Saffar, W. The role of state and foreign owners in corporate risk-taking: Evidence from privatization. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 108, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering baron and kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Definition | Code | Calculation Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Patent application | Apply | Ln (Number of patent applications of the enterprise in the current year + 1) | |

| Invention application | IApply | Ln (Number of invention applications of the enterprise in the current year + 1) | ||

| Non-invention application | InApply | Ln (Total number of applications for utility models and designs of the enterprise in the current year + 1) | ||

| Utility model application | UApply | Ln (Number of utility model applications of the enterprise in the current year + 1) | ||

| Design application | DApply | Ln (Number of design applications of the enterprise in the current year + 1) | ||

| Independent variable | Party organization activities | Party | If the enterprise organizes party activities in that year, the value is 1; Otherwise, it is 0 | |

| Senior executives’ participation in activities | Participate | If the board chairman or CEO participates in the party organization activities, the value is 1; Otherwise, it is 0 | ||

| Control variable | Company fundamentals | Age of listed company | Age | Company listing age |

| Current ratio | CR | Current assets/current liabilities | ||

| Total assets | TA | Logarithm of total assets at the end of the year | ||

| Debt to asset ratio | Lever | Total liabilities/total assets | ||

| Return on operating cash flow | OCF | Net cash flow from operating activities/total assets | ||

| Growth rate of operating revenue | Growth | (main business income of this year–main business income of last year)/main business income of last year | ||

| Corporate governance | Shareholding of the largest shareholder | First | Shareholding of the largest shareholder/total shareholding of the enterprise | |

| Number of directors | Bd | Number of directors | ||

| Proportion of independent directors | Director | Number of independent directors/board of directors | ||

| Duality of the chairman of the board and CEO | Merge | If the chairman of the board and CEO of the enterprise are combined in one year, the value is 1; Otherwise, it is 0 | ||

| Other variables | Invention application_1 | IApply_1 | Ln (total invention applications of the enterprise in the current year and the next year + 1) | |

| Non-invention application_1 | InApply_1 | Ln (total non-invention applications of the enterprise in the current year and the next year + 1) | ||

| Patent application_2 | Apply_2 | Ln (total patent applications of the enterprise in the current year and the next two years + 1) | ||

| Invention application_2 | IApply_2 | Ln (total number of invention applications of the enterprise in the current year and the next two years + 1) | ||

| Non-invention application_2 | InApply_2 | Ln (total non-invention applications of the enterprise in the current year and the next two years + 1) | ||

| Control group | Treat | If Party organization activities have been held in the sample interval, 1; Party organization activities never held are 0 | ||

| R & D investment | Input | Ln (R & D investment of the enterprise in the current year) | ||

| Operating risk | Roabd | Referring to the research of Boubakri et al. [92], the standard deviation of return on assets obtained through industry and annual mean adjustment and rolling calculation with every three years as the observation window period is used as the variable to measure the volatility of return on enterprise risk assets. | ||

| Family firm | Family | If the actual controller of the enterprise is a natural person or family, the value is 1; Otherwise, it is 0 | ||

| Government grants | dbGover | If the government subsidy obtained by the enterprise in the current year is greater than the sample average value, the value is 1; Otherwise, it is 0 | ||

| Factor-industry classification | Factor | According to the proportion of fixed assets and R & D expenditure, all industries are divided into three categories. If they are labor-intensive, they are assigned as 1; Capital-intensive is assigned as 2; Technology-intensive is assigned a value of 3 | ||

| Northern, southern region | Fnb | If the enterprise belongs to the northern region, the value is 1; Otherwise, it is 0 | ||

| Eastern, central and western regions | Fdzx | If the enterprise belongs to the eastern region, the value is 1; 2 in the central region; 3 in the western region | ||

| Region | Area | If the enterprise belongs to the Yangtze River Delta, the value is 1; the Pearl River Delta is assigned as 2; Beijing Tianjin Hebei regions are assigned as 3; other regions are assigned as 4 | ||

| Year | Year | Dummy variable | ||

| Industry | Ind | Virtual variables are classified according to the industry category names of listed companies on the official website of the CSRC | ||

| Full Sample: 2003–2017 | ||||||||

| Observed | Mean | Standard Deviation | min | max | p1 | p50 | p99 | |

| Apply | 7414 | 2.9230 | 1.2450 | 0.6930 | 6.0870 | 0.6930 | 2.9440 | 6.0870 |

| IApply | 7414 | 2.0120 | 1.2480 | 0.0000 | 5.2040 | 0.0000 | 1.9460 | 5.2040 |

| InApply | 7414 | 2.2300 | 1.4310 | 0.0000 | 5.6840 | 0.0000 | 2.3030 | 5.6840 |

| UApply | 7414 | 1.9660 | 1.4370 | 0.0000 | 5.3980 | 0.0000 | 1.9460 | 5.3980 |

| DApply | 7414 | 0.7660 | 1.1480 | 0.0000 | 4.5330 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 4.5330 |

| Party | 7414 | 0.1200 | 0.3250 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Participate | 7414 | 0.0422 | 0.2011 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Subsample 1: 2003–2011 | ||||||||

| Observed | Mean | Standard Deviation | min | max | p1 | p50 | p99 | |

| Apply | 1816 | 2.4410 | 1.1580 | 0.6930 | 5.4030 | 0.6930 | 2.3980 | 5.4030 |

| IApply | 1816 | 1.5380 | 1.1290 | 0.0000 | 4.6440 | 0.0000 | 1.3860 | 4.6440 |

| InApply | 1816 | 1.7570 | 1.3440 | 0.0000 | 4.9200 | 0.0000 | 1.7920 | 4.9200 |

| UApply | 1816 | 1.4160 | 1.3080 | 0.0000 | 4.6630 | 0.0000 | 1.0990 | 4.6630 |

| DApply | 1816 | 0.6720 | 1.0750 | 0.0000 | 4.0780 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 4.0780 |

| Party | 1816 | 0.0610 | 0.2400 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Participate | 1816 | 0.0264 | 0.1605 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Subsample 2: 2012–2017 | ||||||||

| Observed | Mean | Standard Deviation | min | max | p1 | p50 | p99 | |

| Apply | 5598 | 3.0810 | 1.2350 | 0.6930 | 6.2710 | 0.6930 | 3.0910 | 6.2710 |

| IApply | 5598 | 2.1660 | 1.2470 | 0.0000 | 5.3420 | 0.0000 | 2.0790 | 5.3420 |

| InApply | 5598 | 2.3850 | 1.4290 | 0.0000 | 5.8830 | 0.0000 | 2.4850 | 5.8830 |

| UApply | 5598 | 2.1450 | 1.4350 | 0.0000 | 5.5800 | 0.0000 | 2.1970 | 5.5800 |

| DApply | 5598 | 0.7970 | 1.1710 | 0.0000 | 4.6730 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 4.6730 |

| Party | 5598 | 0.1390 | 0.3460 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Participate | 5598 | 0.0473 | 0.2124 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Full Sample: 2003–2017 | |||||

| Activities of Non-Party Organizations | Organized Party Activities | t-Value | |||

| Observed Value | Mean Value | Observed Value | Mean Value | ||

| Age | 6524 | 6.0500 | 890 | 7.9720 | −1.9220 *** |

| CR | 6524 | 0.0300 | 890 | 0.0230 | 0.0070 *** |

| TA | 6524 | 9.3730 | 890 | 9.6310 | −0.2570 *** |

| Lever | 6524 | 0.3620 | 890 | 0.4070 | −0.0450 *** |

| OCF | 6524 | 0.0440 | 890 | 0.0470 | −0.0030 |

| Growth | 6524 | 0.2210 | 890 | 0.2410 | −0.0200 |

| First | 6524 | 0.3320 | 890 | 0.3340 | −0.0020 |

| Bd | 6524 | 10.4140 | 890 | 10.9200 | −0.5070 *** |

| Director | 6524 | 0.3850 | 890 | 0.3800 | 0.0050 |

| Merge | 6524 | 0.3730 | 890 | 0.3280 | 0.0450 *** |

| Subsample 1: 2003–2011 | |||||

| Activities of Non-Party Organizations | Organized Party Activities | t-Value | |||

| Observed Value | mean Value | Observed Value | Mean Value | ||

| Age | 1705 | 5.5740 | 111 | 5.8920 | −0.3180 |

| CR | 1705 | 0.0260 | 111 | 0.0260 | 0.0010 |

| TA | 1705 | 9.2380 | 111 | 9.4020 | −0.1640 *** |

| Lever | 1705 | 0.4130 | 111 | 0.4420 | −0.0290 |

| OCF | 1705 | 0.0420 | 111 | 0.0340 | 0.0080 |

| Growth | 1705 | 0.2230 | 111 | 0.2300 | −0.0070 |

| First | 1705 | 0.3390 | 111 | 0.3510 | −0.0120 |

| Bd | 1705 | 10.9830 | 111 | 11.2430 | −0.2600 |

| Director | 1705 | 0.3580 | 111 | 0.3590 | −0.0010 |

| Merge | 1705 | 0.2730 | 111 | 0.3330 | −0.0610 |

| Subsample 2: 2012–2017 | |||||

| Activities of Non-Party Organizations | Organized Party Activities | t-Value | |||

| Observed Value | Mean Value | Observed Value | Mean Value | ||

| Age | 4819 | 6.2120 | 779 | 8.2680 | −2.0560 *** |

| CR | 4819 | 0.0320 | 779 | 0.0230 | 0.0090 *** |

| TA | 4819 | 9.4210 | 779 | 9.6650 | −0.2430 *** |

| Lever | 4819 | 0.3440 | 779 | 0.4020 | −0.0580 *** |

| OCF | 4819 | 0.0450 | 779 | 0.0490 | −0.0040 * |

| Growth | 4819 | 0.2200 | 779 | 0.2440 | −0.0240 |

| First | 4819 | 0.3300 | 779 | 0.3320 | −0.0020 |

| Bd | 4819 | 10.2150 | 779 | 10.8690 | −0.6540 *** |

| Director | 4819 | 0.3940 | 779 | 0.3830 | 0.0120 *** |

| Merge | 4819 | 0.4090 | 779 | 0.3270 | 0.0810 *** |

| Panel A: Party and Patent Application | |||

| Apply | |||

| 2003–2017 | 2003–2011 | 2012–2017 | |

| Party | 0.2160 *** | 0.1580 | 0.2123 *** |

| (5.70) | (1.56) | (5.19) | |

| Intercept | −10.6480 *** | −8.7430 *** | −10.7850 *** |

| (−25.29) | (−10.29) | (−22.59) | |

| Controls | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control |

| N | 7414 | 1816 | 5598 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3530 | 0.3210 | 0.3440 |

| Panel B: Participate and Patent Application | |||

| Apply | |||

| 2003–2017 | 2003–2011 | 2012–2017 | |

| Participate | 0.1770 *** | 0.1900 | 0.1820 *** |

| (2.97) | (1.28) | (2.79) | |

| Intercept | −10.8030 *** | −8.7740 *** | −10.9500 *** |

| (−25.69) | (−10.33) | (−22.96) | |

| Controls | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control |

| N | 7414 | 1816 | 5598 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3510 | 0.3200 | 0.3420 |

| Panel A: Party and Invention Patent Application, Non-Invention Patent Application | ||||||

| 2003–2017 | 2003–2011 | 2012–2017 | ||||

| IApply | InApply | IApply | InApply | IApply | InApply | |

| Party | 0.1430 *** | 0.2250 *** | −0.0350 | 0.1820 * | 0.1720 *** | 0.2110 *** |

| (3.61) | (5.26) | (−0.35) | (1.72) | (3.97) | (4.58) | |

| Intercept | −11.5750 *** | −9.4800 *** | −10.2260 *** | −5.9670 *** | −11.4930 *** | −10.1970 *** |

| (−26.28) | (−19.88) | (−12.03) | (−6.71) | (−22.73) | (−18.95) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 7414 | 7414 | 1816 | 1816 | 5598 | 5598 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.2960 | 0.3720 | 0.2850 | 0.4160 | 0.2790 | 0.3770 |

| Panel B: Participate and Invention Patent Application, Non-Invention Patent Application | ||||||

| 2003–2017 | 2003–2011 | 2012–2017 | ||||

| IApply | InApply | IApply | InApply | IApply | InApply | |

| Participate | 0.1340 ** | 0.1630 ** | −0.0230 | 0.2650 | 0.1820 *** | 0.1520 ** |

| (2.16) | (2.41) | (−0.15) | (1.55) | (2.64) | (2.07) | |

| Intercept | −11.6730 *** | −9.6450 *** | −10.2150 *** | −6.0400 *** | −11.6200 *** | −10.3670 *** |

| (−26.57) | (−20.26) | (−12.03) | (−6.18) | (−23.03) | (−19.29) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 7414 | 7414 | 1816 | 1816 | 5598 | 5598 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.2950 | 0.3710 | 0.2850 | 0.3310 | 0.2780 | 0.3750 |

| Panel C: Party and Non-Invention Patent Application | ||||||

| 2003–2017 | 2003–2011 | 2012–2017 | ||||

| UApply | DApply | UApply | DApply | UApply | DApply | |

| Party | 0.2290 *** | 0.1090 *** | 0.1820 * | 0.1530 | 0.2230 *** | 0.0870 ** |

| (5.58) | (2.74) | (1.72) | (1.50) | (4.97) | (2.00) | |

| Intercept | −9.5610 *** | −4.8830 *** | −5.9670 *** | −2.1830 ** | −9.9730 *** | −6.0730 *** |

| (−20.97) | (−11.04) | (−6.71) | (−2.54) | (−19.05) | (−11.98) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 7414 | 7414 | 1816 | 1816 | 5598 | 5598 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.4310 | 0.1610 | 0.4160 | 0.1920 | 0.4150 | 0.1770 |

| Panel D: Participate and Non-Invention Patent Application | ||||||

| 2003–2017 | 2003–2011 | 2012–2017 | ||||

| UApply | DApply | UApply | DApply | UApply | DApply | |

| Participate | 0.1570 ** | −0.0060 | 0.1730 | 0.1960 | 0.1680 ** | −0.0580 |

| (2.42) | (−0.09) | (1.72) | (1.11) | (2.35) | (−0.83) | |

| Intercept | −9.7310 *** | −4.9820 *** | −6.0130 *** | −2.2110 ** | −10.1500 *** | −6.1640 *** |

| (−21.37) | (−11.29) | (−6.76) | (−2.57) | (−19.41) | (−12.19) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 7414 | 7414 | 1816 | 1816 | 5598 | 5598 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.4290 | 0.1600 | 0.4150 | 0.1920 | 0.4130 | 0.1770 |

| Full Sample: 2003–2017 | |||||||||

| Apply | IApply | InApply | |||||||

| NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | |

| ATT difference | 0.2070 *** | 0.2190 *** | 0.2250 *** | 0.1330 ** | 0.1320 *** | 0.1430 *** | 0.2250 *** | 0.2330 *** | 0.2360 *** |

| (3.47) | (4.51) | (4.71) | (2.16) | (2.61) | (2.88) | (3.24) | (4.11) | (4.24) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Subsample 1: 2003–2011 | |||||||||

| Apply | IApply | InApply | |||||||

| NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | |

| ATT difference | 0.0970 | 0.1440 | 0.2030 * | −0.2430 | −0.1320 | −0.0700 | 0.3320 * | 0.2540 * | 0.303 ** |

| (0.63) | (1.24) | (1.83) | (−1.47) | (−1.06) | (−0.59) | (1.75) | (1.71) | (2.14) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Subsample 2: 2012–2017 | |||||||||

| Apply | IApply | InApply | |||||||

| NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | NNM | RM | KM | |

| ATT difference | 0.2120 *** | 0.2120 *** | 0.2180 *** | 0.1550 ** | 0.1670 *** | 0.1550 *** | 0.2260 *** | 0.2150 *** | 0.2190 *** |

| (3.30) | (4.02) | (4.17) | (2.32) | (3.11) | (2.84) | (3.05) | (3.49) | (3.61) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Apply | Apply | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2011 | 2003–2012 | 2003–2011 | 2003–2012 | |

| Treat × Party | 0.1580 | 0.1720 ** | ||

| (1.56) | (2.08) | |||

| Treat × Participate | 0.1900 | 0.2214 * | ||

| (1.28) | (1.81) | |||

| Intercept | −8.7430 *** | −9.5310 *** | −8.7740 *** | −9.5696 *** |

| (−10.29) | (−12.91) | (−10.33) | (−12.97) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control |

| N | 1816 | 2511 | 1816 | 2511 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3210 | 0.3280 | 0.3200 | 0.3274 |

| Panel A: Party and Corporate Innovation | ||||||

| Apply_1 | IApply_1 | InApply_1 | Apply_2 | IApply_2 | InApply_2 | |

| Party | 0.1310 ** | 0.0300 | 0.1740 *** | 0.1420 *** | 0.0400 | 0.1740 *** |

| (2.54) | (0.52) | (2.70) | (2.87) | (0.70) | (2.73) | |

| Intercept | −10.2790 *** | −12.0150 *** | −9.4960 *** | −9.5760 *** | −11.5180 *** | −9.4620 *** |

| (−17.00) | (−17.62) | (−12.60) | (−16.50) | (−17.27) | (−12.67) | |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 4461 | 4461 | 4461 | 4461 | 4461 | 4461 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3490 | 0.3080 | 0.3850 | 0.3680 | 0.3260 | 0.4000 |

| Panel B: Participate and Corporate Innovation | ||||||

| Apply_1 | IApply_1 | InApply_1 | Apply_2 | IApply_2 | InApply_2 | |

| Participate | 0.1480 * | 0.065 | 0.1550 | 0.1730 ** | 0.092 | 0.157 |

| (1.77) | (0.69) | (1.49) | (2.15) | (1.00) | (1.52) | |

| Intercept | −10.3350 *** | −12.0220 *** | −9.5770 *** | −9.6340 *** | −11.5250 *** | −9.5430 *** |

| (−17.10) | (−17.65) | (−12.71) | (−16.61) | (−17.31) | (−12.79) | |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 4461 | 4461 | 4461 | 4461 | 4461 | 4461 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3490 | 0.3080 | 0.3840 | 0.3670 | 0.3260 | 0.4000 |

| Panel A: The Intermediary Effect of R & D Investment | |||||||

| Variable Name | Coefficient | Estimation Standard Error | T-Value | p > |t| | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| The effect of the Party on Apply | Party | 12.0210 | 2.391 | 5.030 | 0.000 | 7.334 | 16.707 |

| The effect of the Party on Input | Party | 0.0900 | 0.030 | 2.950 | 0.003 | 0.030 | 0.150 |

| The effect of the Party on Input and Apply | Input | 18.6320 | 0.974 | 19.130 | 0.000 | 16.723 | 20.541 |

| Party | 10.3460 | 2.324 | 4.450 | 0.000 | 5.789 | 14.903 | |

| Panel B: The Intermediary Effect of Operating Risk | |||||||

| Variable Name | Coefficient | Estimation Standard Error | T-value | p > |t| | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| The effect of the Party on Apply | Party | 0.1500 | 0.0550 | 2.7200 | 0.0070 | 0.0420 | 0.2570 |

| The effect of the Party on operating risk | Party | −0.0030 | 0.0020 | −1.5400 | 0.1230 | −0.0060 | 0.0010 |

| The effect of the Party on operating risk and Apply | Roabd | −0.9160 | 0.4760 | −1.9200 | 0.0540 | −1.8490 | 0.0170 |

| Party | 0.1470 | 0.0550 | 2.6800 | 0.0070 | 0.0390 | 0.2550 | |

| Panel A: Sobel Test of the Intermediary Effect of R&D Investment | ||||

| Coefficient | Estimation Standard Error | Z-Value | p > |z| | |

| Sobel | 1.7580 | 0.7330 | 2.3990 | 0.0160 |

| Goodman-1 (Aroian) | 1.7580 | 0.7330 | 2.3970 | 0.0170 |

| Goodman-2 | 1.7580 | 0.7320 | 2.4010 | 0.0160 |

| Panel B: Sobel Test of Intermediary Effect of Enterprise Operating Risk | ||||

| Coefficient | Estimation Standard Error | Z-Value | p > |z| | |

| Sobel | 0.0100 | 0.0050 | 2.1910 | 0.0280 |

| Goodman-1 (Aroian) | 0.0100 | 0.0050 | 2.1550 | 0.0310 |

| Goodman-2 | 0.0100 | 0.0050 | 2.2290 | 0.0260 |

| Family Enterprise | Non Family Enterprise | Government Subsidies Are above Average | Government Subsidies Are below Average | Labour- Intensive | Capital- Intensive | Technology-Intensive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Apply | Apply | Apply | |||||

| Party | 0.2030 *** | 0.4640 | 0.1940 *** | 0.2200 *** | 0.0940 | 0.2000 *** | 0.2600 *** |

| (4.85) | (1.21) | (3.65) | (3.51) | (0.93) | (2.61) | (4.73) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Intercept | −11.1120 *** | −8.6440 | −11.2800 *** | −6.4890 *** | −6.6970 *** | −6.7990 *** | −12.7580 *** |

| (−23.36) | (−1.43) | (−15.35) | (−9.08) | (−6.59) | (−8.17) | (−24.75) | |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 5504 | 94 | 2841 | 2697 | 857 | 1450 | 3291 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3540 | 0.5700 | 0.3840 | 0.2530 | 0.3140 | 0.2480 | 0.3860 |

| Northern Region | Southern Region | Eastern Region | Central Region | West Region | Yangtze River Delta | Pearl River Delta | Beijing Tianjin Hebei Region | Other Regions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Apply | Apply | Apply | |||||||

| Party | 0.3140 *** | 0.1110 ** | 0.2050 *** | 0.1250 | 0.4840 *** | 0.2690 *** | 0.0810 | 0.4390 *** | 0.2120 *** |

| (5.14) | (2.04) | (4.18) | (1.48) | (3.08) | (4.47) | (0.68) | (2.92) | (3.15) | |

| Controls | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Intercept | −12.3500 *** | −9.9710 *** | −11.9470 *** | −7.5370 *** | −12.2330 *** | −9.7340 *** | −11.9290 *** | −14.7410 *** | −9.6180 *** |

| (−17.62) | (−14.43) | (−21.20) | (−6.73) | (−7.12) | (−8.56) | (−9.12) | (−9.04) | (−13.01) | |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Ind | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| N | 2452 | 3146 | 4233 | 915 | 450 | 2139 | 1007 | 588 | 1864 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.3810 | 0.3670 | 0.3640 | 0.4060 | 0.4610 | 0.3890 | 0.4430 | 0.4780 | 0.3410 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.; Hao, N. The Influence of Party Organization Involvements in Corporate Governance on Innovation: Evidence from China’s Private-Owned Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416334

Liu X, Zhou J, Wu Y, Hao N. The Influence of Party Organization Involvements in Corporate Governance on Innovation: Evidence from China’s Private-Owned Enterprises. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416334

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaoxue, Jingyun Zhou, You Wu, and Na Hao. 2022. "The Influence of Party Organization Involvements in Corporate Governance on Innovation: Evidence from China’s Private-Owned Enterprises" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416334