The Influence of High-Performance Work Systems on the Innovation Performance of Knowledge Workers

Abstract

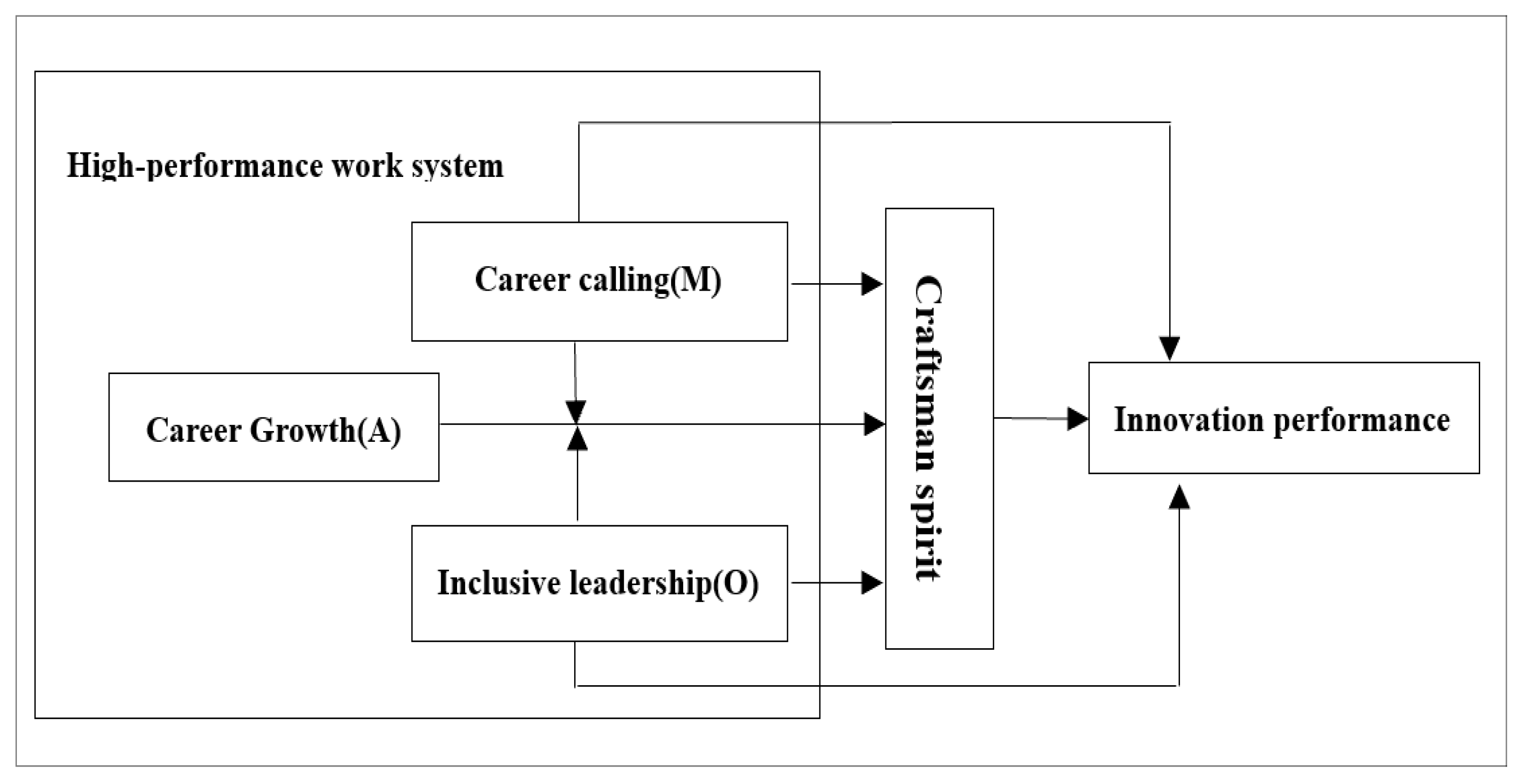

1. Introduction

- From the perspective of the non-material incentive, this research combines the variables at the individual-level and the organizational-level and establishes a cross-level high-performance work system for knowledge workers, which effectively makes up the deficiencies of the single-level incentive system.

- This research not only reveals the mechanism and boundary conditions between the high-performance system and innovation performance, but also effectively enriches the implication of relevance theory.

- This research proposes a series of feasible strategies to improve the innovation performance of knowledge workers, which can help enterprise managers better apply high-performance work systems to management practices.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

2.2. Research Hypothesis

2.2.1. The Influence of Career Growth on Innovation Performance of Knowledge Workers

2.2.2. The Influence of Career Calling on Innovation Performance of Knowledge Workers

2.2.3. The Influence of Inclusive Leadership on Innovation Performance of Knowledge Workers

2.2.4. The Intermediary Role of the Craftsman Spirit

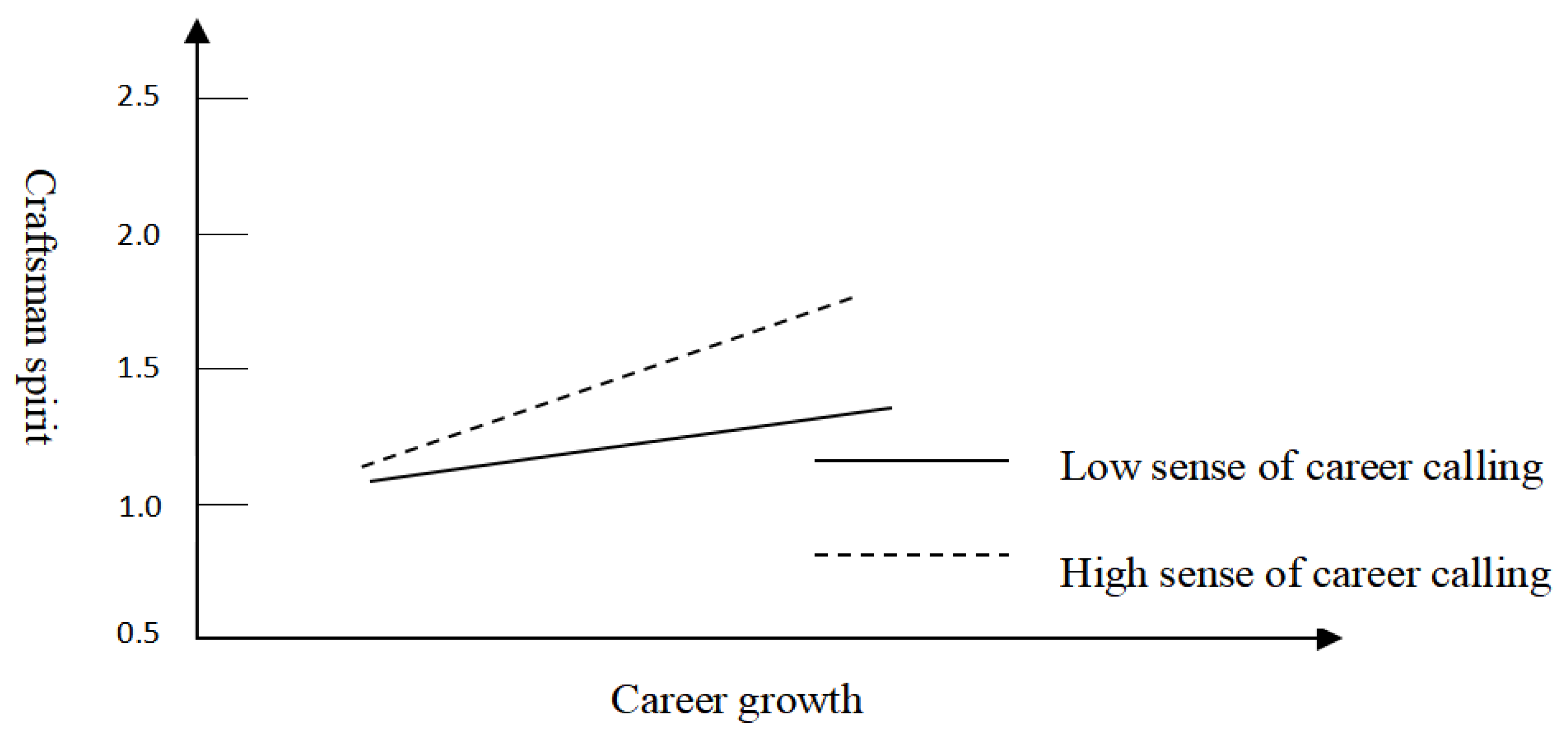

2.2.5. The Moderating Role of Career Calling

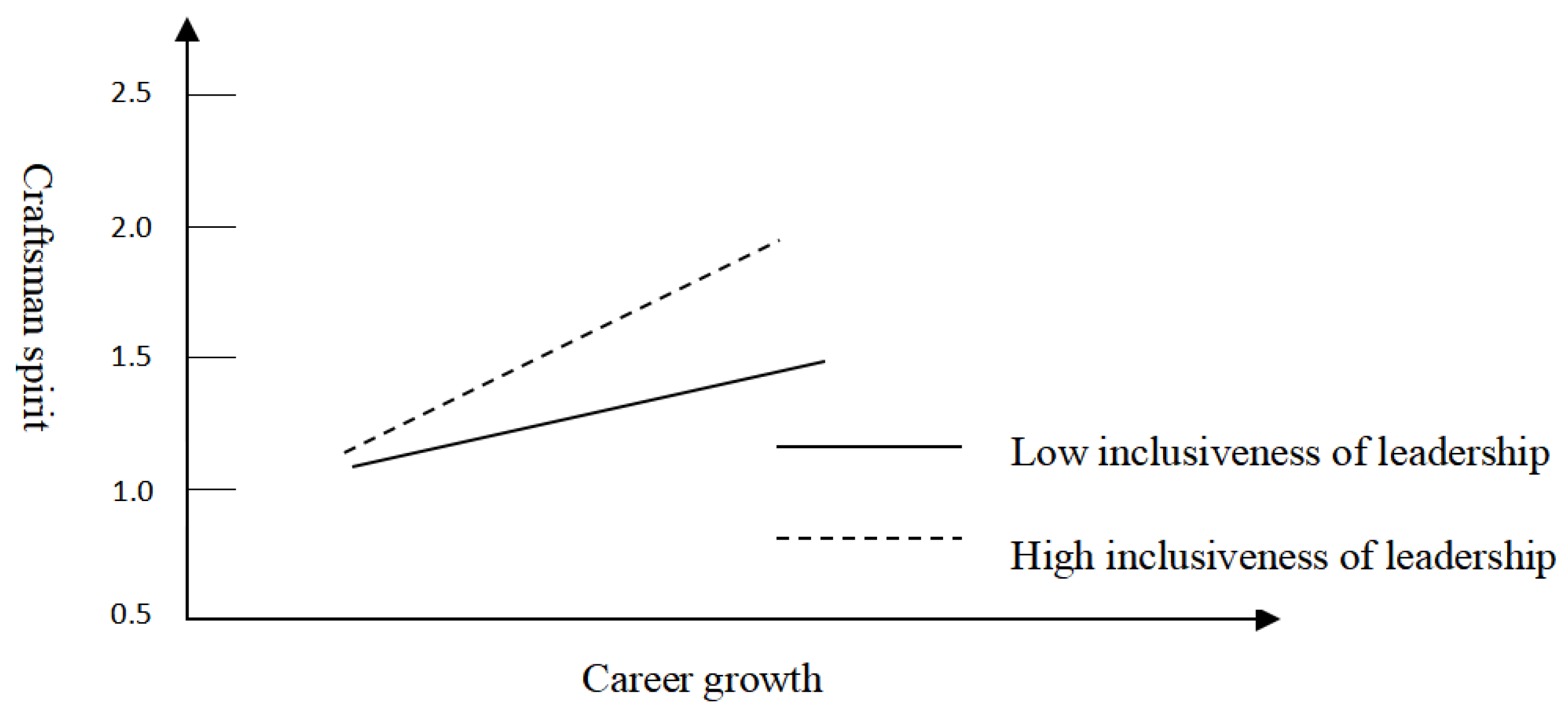

2.2.6. The Moderating Role of Inclusive Leadership

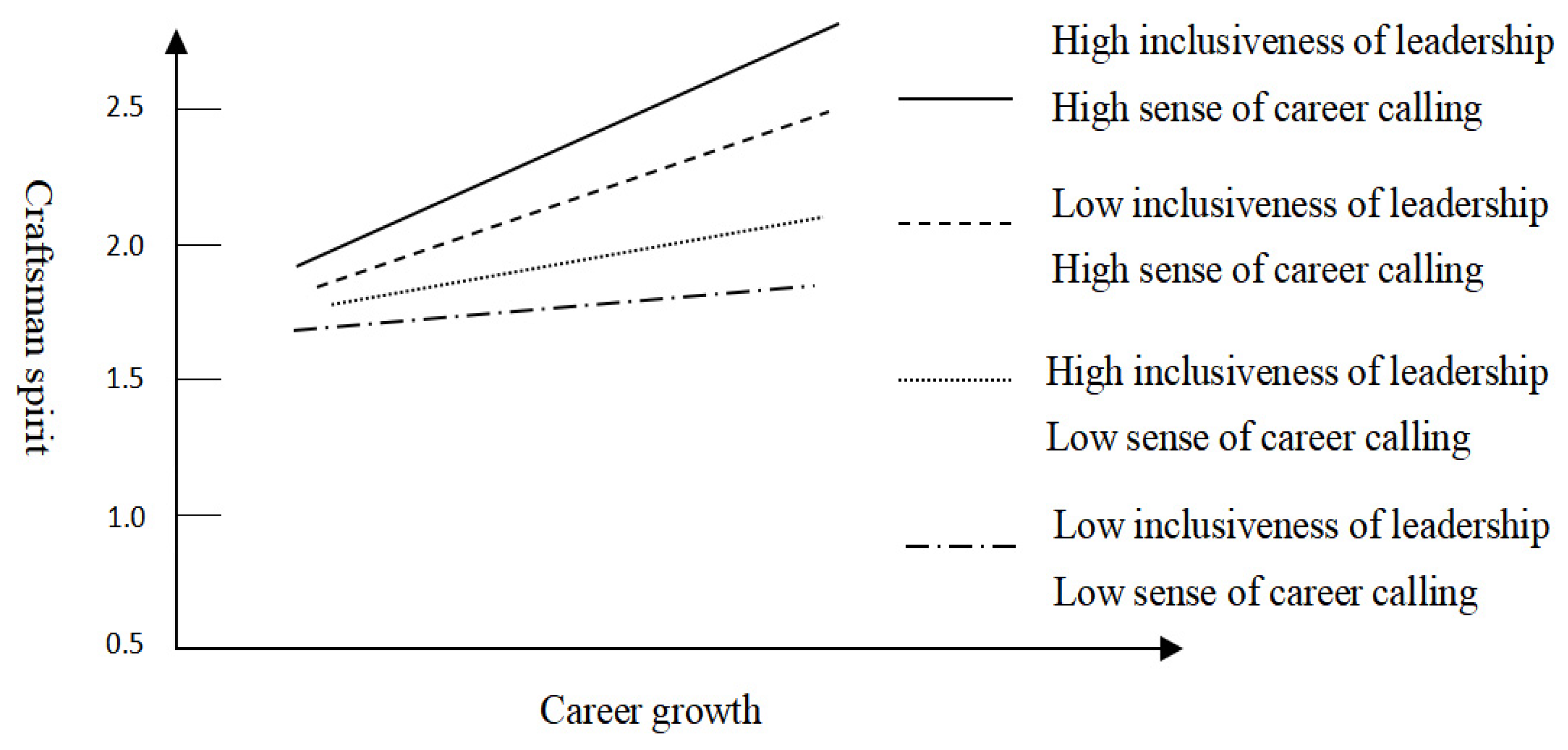

2.2.7. The Moderating Role of the Interaction between Career Calling and Inclusive Leadership

3. Research Design and Method

3.1. Measurement Scales

3.2. Small Sample Investigation

3.3. Formal Investigation

3.4. Reliability and Validity Test

3.5. Descriptive Statistical Analysis and Correlation Analysis

3.6. Hypothesis Test

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Limitations and Direction for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muzam, J. The Challenges of Modern Economy on the Competencies of Knowledge Workers. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Xiang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Research on the Configuration of Value Chain Transition in Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises. Systems 2022, 10, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Fan, L. The performance of knowledge workers based on behavioral perspective. J. Hum. Resour. Sustain. Stud. 2015, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramona-Diana, L. The development of the future european knowledge workers. An academic perspective. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 4, 339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Nayeri, M.D. A model on knowledge workers performance evaluation. Rev. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Nawaz, F.; Hussain, S.; Sousa, M.J.; Wang, M.; Sumbal, M.S.; Shujahat, M. Individual knowledge management engagement, knowledge-worker productivity, and innovation performance in knowledge-based organizations: The implications for knowledge processes and knowledge-based systems. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 2019, 25, 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, B.; Rađenović, T. Knowledge workers: Human capital in the function of increasing intellectual potential and performances of enterprises. Ekon. Izazovi 2017, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramona-Diana, L. The future knowledge worker: An intercultural perspective. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2015, 3, 675–691. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. The interplay between the social and economic human resource management systems on innovation capability and performance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 2150074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.T. How spirituality, climate and compensation affect job performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gulyani, G.; Sharma, T. Total Rewards Components and Work Happiness in New Ventures: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement; Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum For Empirical Scholarship 2018; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Tsai, M. Strengthening long-term job performance: The moderating roles of sense of responsibility and leader’s support. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuron, L.K.; Lyons, S.T.; Schweitzer, L.; Ng, E.S. Millennials’ work values: Differences across the school to work transition. Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahn, H.J.; Galambos, N.L. Work values and beliefs of ‘Generation X’ and ‘Generation Y’. J. Youth Stud. 2014, 17, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwkamp-Memmer, J.C.; Whiston, S.C.; Hartung, P.J. Work values and job satisfaction of family physicians. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Králiková, K.; Králik, J. Atmosphere in Workplace Mirror of Society. Soc. Econ. Rev. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekawati, I. Improving Work Productivity through the Improvement of Organizational Atmosphere and Culture. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agriculture, Social Sciences, Education, Technology and Health (ICASSETH 2019); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, M.A. The mediating role of work atmosphere in the relationship between supervisor cooperation, career growth and job satisfaction. J. Workplace Learn. 2019, 31, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Zhu, L. Individuals’ career growth within and across organizations: A review and agenda for future research. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande Griek, O.H.; Clauson, M.G.; Eby, L.T. Organizational career growth and proactivity: A typology for individual career development. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohunakin, F.; Adeniji, A.; Oludayo, O.; Osibanjo, O. Perception of frontline employees towards career growth opportunities: Implications on turnover intention. Verslas Teor. Ir Prakt. 2018, 19, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Khan, M.S.; Raza, A.; Shahzad, I.A. Influence of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2021, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manresa, A.; Bikfalvi, A.; Simon, A. Exploring the relationship between individual and bundle implementation of High-Performance Work Practices and performance: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Cao, Y. High-performance work system, work well-being, and employee creativity: Cross-level moderating role of transformational leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellner, A.; Townsend, K.; Wilkinson, A. ‘The mission or the margin?’ A high-performance work system in a non-profit organisation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 1938–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, A.; Verma, S.; Datta, S.K. High performance work system in India: Examining the role of employee engagement. J. Asia-Pac. Bus. 2016, 17, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.; Hsu, C.; Shih, H. Experienced high performance work system, extroversion personality, and creativity performance. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Cultivation of craftsman spirit in employment and entrepreneurship education in colleges. J. Front. Educ. Res. 2021, 1, 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yangchun, F.; Chaoying, C. Influence of inclusive talent development model on the employees’ craftsman spirit. Sci. Res. Manag. 2018, 39, 154. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E.; Bailey, T.R.; Berg, P.B.; Kalleberg, A.L. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High-Performance Work Systems Pay Off; Cornell University Press: Kithaca, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Su, X. Zhang, H. The Influence mechanism of the mentoring relationship on the innovation performance of the new generation of migrant workers under the background of high-quality development of manufacturing industry: A dual regulatory intermediary model. Macro Qual. Res. 2020, 8, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Liu, J. A study on the influence of career growth on work engagement among new generation employees. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 6, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dialoke, I.; Nkechi, P.A.J. Effects of career growth on employees performance: A study of non-academic staff of Michael Okpara University of Agriculture Umudike Abia State, Nigeria. Singap. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 5, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, F.; Zhao, F.; Faraz, N.A.; Qin, Y.J. How inclusive leadership paves way for psychological well-being of employees during trauma and crisis: A three-wave longitudinal mediation study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourke, J.; Titus, A.; Espedido, A. The key to inclusive leadership. Harvard Business Review, 6 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Randel, A.E.; Galvin, B.M.; Shore, L.M.; Ehrhart, K.H.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Kedharnath, U. Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.; Matkin, G. The Evolution of Inclusive Leadership Studies: A literature review. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, Q.; Perry, J.L. Inclusive leadership in thought and action: A thematic analysis. Group Organ. Manag. 2022, 47, 755–778. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Research on the Effect of Training on Knowledge Workers’ Turnover in Small and Micro Business—Based on the Perspective of Game Theory. J. Putian Univ. 2017, 24, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Fan, Y.; Ma, G. The Effect of Status on Creative Performance of Knowledge Workers from the Perspective of Risk-Taking and Creativity-Related Support. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2016, 37, 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Elangovan, A.R.; Pinder, C.C.; Mclean, M. Callings and organizational behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, E.M.; Duffy, R.D.; Borges, N.J.; Braun, T.L.; Jordan, K.P.; Marino, J.F. Called to medicine: Physicians’ experiences of career calling. Career Dev. Q. 2017, 65, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Mcelroy, J.C.; Morrow, P.C.; Liu, R. The relationship between career growth and organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Mcelroy, J.C. Corrigendum to ‘Organizational career growth, affective occupational commitment and turnover intentions’. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mládková, L.; Zouharová, J.; Nový, J. Motivation and knowledge workers. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, C.; Myerson, J. Space for thought: Designing for knowledge workers. Facilities 2011, 29, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Tartari, V.; Huang, K.G.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Bercovitz, J. Knowledge worker mobility in context: Pushing the boundaries of theory and methods. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, H.; Parker, R.J. Career growth opportunities and employee turnover intentions in public accounting firms. Br. Account. Rev. 2013, 45, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, R.P.; Burnett, D.D. A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Guterman, H.A. Situation trait relevance, trait expression, and cross-situational consistency: Testing a principle of trait activation. J. Res. Pers. 2000, 34, 397–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kanfer, R. Toward a systems theory of motivated behavior in work teams. Res. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 223–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Meira, J.V.; Hancer, M. Using the social exchange theory to explore the employee-organization relationship in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 670–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyak-Hai, L.; Rabenu, E. The new era workplace relationships: Is social exchange theory still relevant? Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 11, 456–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N. The influencing outcomes of job engagement: An interpretation from the social exchange theory. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social behavior as exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrow, S.R.; Tosti Kharas, J. Calling: The development of a scale measure. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praskova, A.; Creed, P.A.; Hood, M. The development and initial validation of a career calling scale for emerging adults. J. Career Assess. 2015, 23, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P.; Autin, K.L.; Allan, B.A. Examining predictors and outcomes of a career calling among undergraduate students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, M.; Dalla Rosa, A.; Gerdel, S. Career Calling and Task Performance: The Moderating Role of Job Demand. J. Career Assess. 2022, 30, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P.A.; Kaya, M.; Hood, M. Vocational identity and career progress: The intervening variables of career calling and willingness to compromise. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.W.; Lucianetti, L. Within-individual increases in innovative behavior and creative, persuasion, and change self-efficacy over time: A social-cognitive theory perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Collins, M.A.; Conti, R.; Phillips, E.; Picariello, M.; Ruscio, J.; Whitney, D. Creativity in Context: Update to the Social Psychology of Creativity; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhani, T.; Hadizadeh Moghadam, A.; Azimi, S. Organizational Obstruction and Its Reducing Factors: A Study of the Impact of Psychological Empowerment, innovation Atmosphere and Employee Voice in Organization. Public Manag. Perspect. 2019, 8, 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, J.; Song, H. Correlation study on organizational innovation atmosphere and nurses′ job satisfaction. Chin. J. Hosp. Adm. 2019, 231–234. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/wpr-756595 (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Mengli, G.; Jun, F. An empirical analysis of the influence mechanism of external innovation atmosphere on service innovation performance. Sci. Res. Manag. 2018, 39, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Schabram, K.; Maitlis, S. Negotiating the challenges of a calling: Emotion and enacted sensemaking in animal shelter work. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 584–609. [Google Scholar]

- Gahan, P.; Theilacker, M.; Adamovic, M.; Choi, D.; Harley, B.; Healy, J.; Olsen, J.E. Between fit and flexibility? The benefits of high-performance work practices and leadership capability for innovation outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 414–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembhard, I.M.; Edmondson, A.C. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 941–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Another Look at Social Exchange: Two Dimensions of Reciprocity. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2014, 2014, 10144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, R.K.; Wright, S.L.; Heaphy, E.D. A critique of the Leader-Member Exchange construct: Back to square one. Leadersh. Q. 2020, 31, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B.; Tran, T.B.H.; Park, B.I. Inclusive leadership and work engagement: Mediating roles of affective organizational commitment and creativity. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N. Leader-member exchange theory. In The Oxford Handbook of Leader-Member Exchange; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rockstuhl, T.; Dulebohn, J.H.; Ang, S.; Shore, L.M. Leader–member exchange (LMX) and culture: A meta-analysis of correlates of LMX across 23 countries. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladić, N.; Maletič, D.; Maletič, M. Determinants of Innovation Capability: An Exploratory Study of Inclusive Leadership and Work Engagement. Qual. Innov. Prosper. 2021, 25, 130–152. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, B.; Abdullah, I.; Zaffar, M.A.; Ul Haque, A.; Rubab, U. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of psychological empowerment. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, D.; Guo, W. Inclusive leadership and team innovation: The role of team voice and performance pressure. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, C.C.; Yu, Z. Inclusion and inclusion management in the Chinese context: An exploratory study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 856–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B.J.; Eldridge, B.M.; Steger, M.F.; Duffy, R.D. Development and validation of the calling and vocation questionnaire (CVQ) and brief calling scale (BCS). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 242–263. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Acad Manag Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: Oxford, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Rajiani, I.; Musa, H.; Hardjono, B. Research article ability, motivation and opportunity as determinants of green human resources management innovation. Res. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moussa, M.; Bright, M.; Varua, M.E. Investigating knowledge workers’ productivity using work design theory. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2017, 66, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernaus, T.; Mikulić, J. Work characteristics and work performance of knowledge workers. EuroMed J. Bus. 2014, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, D.; Ellemers, N. Social identity theory. In Social Psychology in Action; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A. Social identity theory. In Understanding Peace and Conflict through Social Identity Theory; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. Inclusive leadership and social justice for schools. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2006, 5, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.; Gagné, M.; Morin, A.J.; Van den Broeck, A. Motivation profiles at work: A self-determination theory approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, D.L. Perceptions of career agency and career calling in mid-career: A qualitative investigation. J. Career Assess. 2021, 29, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.U. Turnover of highly educated R&D professionals: The role of pre-entry cognitive style, work values and career orientation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 299–317. [Google Scholar]

- Biswakarma, G. Organizational career growth and employees’ turnover intentions: An empirical evidence from Nepalese private commercial banks. Int. Acad. J. Organ. Behav. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 3, 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X. Congruence in career calling and employees’ innovation performance: Work passion as a mediator. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2021, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Kim, D. Organizational career growth and career commitment: Moderated mediation model of work engagement and role modeling. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 4287–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Eisenberger, R.; Baik, K. Perceived organizational support and affective organizational commitment: Moderating influence of perceived organizational competence. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 558–583. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Nawaz, M.M. Antecedents and outcomes of perceived organizational support: A literature survey approach. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; King, C.E. Empowering employee sustainability: Perceived organizational support toward the environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, D. Factors Affecting Employees’ Turnover Intension:A Quantitive Study of Some New Variables. Manag. Rev. 2007, 19, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M. Development and validation of the new generation of migrant workers’ craftsmanship scale in manufacturing industry. J. Manag. 2020, 17, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, H.A.N.; Jianqiao, L.; Lirong, L. Model of development and empirical study on employee job performance construct. J. Manag. Sci. China 2007, 10, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Balkin, D.B.; Roussel, P.; Werner, S. Performance contingent pay and autonomy: Implications for facilitating extra-role creativity. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.; Lewis, K.J. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Salenger Inc. 1987, 14, 987–990. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Number of Items | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Career growth | 3 | Zhangmian and Zhangde. [101] |

| Career calling | 12 | Dobrow [58] |

| Inclusive leadership | 9 | Carmeli et al. [89] |

| Craftsman spirit | 8 | Liqun et al. [102] |

| Innovation performance | 8 | Hanyi et al. [103] |

| Statistical Items | Frequency | Percentage | Statistical Items | Frequency | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 198 | 54.4 | Working Age | 5 years and below | 120 | 33.0 |

| Female | 166 | 45.6 | |||||

| Age | 25 and under | 57 | 15.7 | 6–10 years | 184 | 50.5 | |

| 26–35 years old | 236 | 64.8 | 11–20 years | 55 | 15.1 | ||

| 36–45 years old | 55 | 15.1 | 21 years and above | 5 | 1.4 | ||

| 46–55 years old | 14 | 3.8 | Position | Grassroots staff | 284 | 78.0 | |

| 56 years and over | 2 | 0.5 | |||||

| Education | College degree or below | 15 | 4.1 | Grassroots Manager | 54 | 14.8 | |

| Bachelor degree | 255 | 70.1 | Middle manager | 22 | 6.0 | ||

| Master’s degree | 82 | 22.5 | |||||

| Doctorate | 12 | 3.3 | Senior management | 4 | 1.1 | ||

| Construct | Code | Item | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Career Growth α = 0.843 AVE = 0.648 CR = 0.846 | CG1 | The company can provide me with the opportunity to keep up with new trends related to work. | 0.716 |

| CG2 | The company can provide me with relevant resources to learn new knowledge or improve professional skills. | 0.860 | |

| CG3 | The company enables me to continuously grow and improve in my work. | 0.831 | |

| Career Calling α = 0.929 AVE = 0.599 CR = 0.931 | CC1 | I am full of enthusiasm for my work. | 0.712 |

| CC2 | Being in my profession gives me great satisfaction. | 0.768 | |

| CC3 | When describing who I am to others, I usually think of my career first. | 0.770 | |

| CC4 | My career will always be a part of my life. | 0.787 | |

| CC5 | I feel a sense of mission about my career. | 0.747 | |

| CC6 | In a sense, my career has always been in my heart. | 0.762 | |

| CC7 | Even if I didn’t do this job, I often think about doing it. | 0.818 | |

| CC8 | Joining my current career makes my life more meaningful. | 0.798 | |

| CC9 | Engaging in my career can deeply touch my heart and bring me joy. | 0.796 | |

| Inclusive Leadership α = 0.838 AVE = 0.663 CR = 0.782 | IL1 | My leaders are willing to listen to new ideas. | 0.664 |

| IL2 | My leadership focuses on new opportunities to improve their work. | 0.745 | |

| IL3 | My leader is willing to discuss the desired goals and new ways to achieve them. | 0.710 | |

| IL4 | When I encounter problems, my leader will provide guidance at any time. | 0.799 | |

| IL5 | My leader is a real member of the team (it can be said that he/she can be found at any time). | 0.835 | |

| IL6 | I can find leaders to consult professional problems at any time. | 0.822 | |

| IL7 | My leader is willing to listen to my request. | 0.802 | |

| IL8 | My leader encourages me to go to him/her when I encounter sudden or emerging problems. | 0.695 | |

| IL9 | I can easily approach my leader and discuss sudden or emerging problems with him/her. | 0.899 | |

| Craftsman spirit α = 0.866 AVE = 0.686 CR = 0.878 | CS1 | Master post knowledge and skills. | 0.687 |

| CS2 | Pay attention to detail management. | 0.736 | |

| CS3 | Choose an effective way to work. | 0.823 | |

| CS4 | Insist on studying and improving the existing skills and working mode. | 0.785 | |

| CS5 | Pursue the perfection and perfection of products. | 0.661 | |

| CS6 | Existing work is a lifelong career and value pursuit. | 0.892 | |

| CS7 | Take the initiative to put forward suggestions to improve product quality. | 0.840 | |

| CS8 | Proactively meet or exceed customer needs for products. | 0.876 | |

| Innovation performance α = 0.854 AVE = 0.587 CR = 0.863 | IP1 | I will provide new ideas to improve the existing situation. | 0.691 |

| IP2 | I can actively support innovative ideas. | 0.724 | |

| IP3 | I often get praise from my superiors for my innovative ideas. | 0.820 | |

| IP4 | I can turn innovative ideas into practical applications. | 0.830 | |

| IP5 | I will put forward some original solutions to problems through learning. | 0.556 | |

| IP6 | I can introduce innovative ideas in a systematic way. | 0.654 |

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 1.46 | 0.48 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2 Age | 2.09 | 0.71 | 0.036 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3 educations | 2.25 | 0.58 | 0.012 | 0.027 * | 1 | |||||||

| 4 working ages | 1.85 | 0.72 | 0.030 | 0.821 * | −0.112 | 1 | ||||||

| 5 job level | 1.30 | 0.63 | 0.031 | 0.714 * | 0.094 | 0.563 * | 1 | |||||

| 6 CG | 3.11 | 10.05 | −0.075 * | −0.072 | 0.037 | −0.072 | −0.097 | 1 | ||||

| 7 CC | 3.04 | 10.22 | −0.014 | 0.056 | 0.153 | 0.027 | 0.043 * | 0.450 ** | 1 | |||

| 8 IL | 3.18 | 00.88 | 0.056 | −0.139 | −0.091 | −0.071 | −0.151 | 0.322 ** | 0.399 ** | 1 | ||

| 9 CS | 2.88 | 00.94 | 0.128 * | 0.064 | 0.132 ** | 0.073 | 0.035 | 0.432 ** | 0.480 ** | 0.429 ** | 1 | |

| 10 IP | 2.94 | 10.02 | 0.175 * | 0.102 | −0.191 * | 0.068 | 0.076 | 0.321 ** | 0.506 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.496 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Innovation Performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Gender | 0.163 * | 0.074 | 0.113 * | 0.124 * |

| Age | −0.088 | −0.094 | −0.090 | −0.914 |

| Education | −0.128 * | −0.117 * | −0.097 * | −0.144 * |

| Working years | 0.261 | 0.249 | 0.262 | 0.236 |

| Position | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.016 |

| Career growth | 0.335 ** | |||

| Career calling | 0.172 ** | |||

| Inclusive leadership | 0.162 ** | |||

| R2 | 0.021 | 0.287 | 0.164 | 0.152 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.019 | 0.282 | 0.157 | 0.147 |

| ∆R2 | 0.019 | 0.274 | 0.146 | 0.134 |

| F | 110.975 * | 190.458 ** | 130.773 ** | 110.274 ** |

| VIF | 1.002–2.289 | 1.003–2.291 | 1.002–2.412 | 1.006–2.291 |

| Path | Effect | Coefficient | Standard Error | 95% Deviation Corrected Confidence Interval | Proportion in Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG→CS→IP | Dircet | 0.111 | 0.042 | [0.028, 0.193] | 41.11% |

| Indirect | 0.159 | 0.026 | [0.111, 0.212] | 58.89% | |

| Total | 0.270 | 0.042 | [0.187, 0.351] | - | |

| CC→CS→IP | Dircet | 0.348 | 0.049 | [0.252, 0.444] | 68.77% |

| Indirect | 0.158 | 0.026 | [0.107, 0.211] | 31.23% | |

| Total | 0.506 | 0.045 | [0.417, 0.596] | - | |

| IL→CS→IP | Dircet | 0.403 | 0.046 | [0.314, 0.493] | 74.63% |

| Indirect | 0.137 | 0.026 | [0.091, 0.194] | 25.37% | |

| Total | 0.540 | 0.044 | [0.455, 0.627] | - |

| Variables | Craftsman Spirit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Gender | 0.125 | 0.057 | 0.052 | 0.064 | 0.058 | 0.041 | 0.051 | 0.050 |

| Age | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.022 | 0.019 | 0.027 | 0.024 |

| Education | −0.089 | −0.071 | −0.077 | −0.089 | −0.083 | −0.092 | −0.083 | −0.091 |

| Working Years | 0.177 ** | 0.161 * | 0.145 ** | 0.143 * | 0.150 ** | 0.183 | 0.167 * | 0.167 ** |

| Position | −0.008 | −0.012 | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.015 | −0.008 | −0.017 | −0.013 |

| Main effect | ||||||||

| CG | 0.443 * | 0.432 ** | 0.417 ** | 0.405 ** | 0.386 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.346 ** | |

| CC | 0.097 * | 0.088 | 0.027 | 0.016 | ||||

| IL | 0.172 * | 0.158 * | 0.133 * | 0.116 * | ||||

| Regulatory effect | ||||||||

| CG × CC | 0.114 ** | 0.076 | 0.063 | |||||

| CG × IL | 0.063 * | 0.020 | 0.017 | |||||

| CC × IL | 0.048 | −0.023 | ||||||

| Interactive Regulatory Utility | ||||||||

| CG × CC × IL | 0.132 * | |||||||

| R2 | 0.075 | 0.242 | 0.259 | 0.271 | 0.284 | 0.293 | 0.302 | 0.315 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.071 | 0.236 | 0.255 | 0.266 | 0.273 | 0.286 | 0.293 | 0.309 |

| ∆R2 | 0.067 | 0.232 | 0.247 | 0.252 | 0.263 | 0.278 | 0.286 | 0.297 |

| F | 60.688 ** | 230.108 ** | 210.680 ** | 200.074 ** | 220.184 ** | 210.046 ** | 180.941 ** | 170.357 ** |

| VIF | 10.023–20.311 | 10.013–20.355 | 10.012–20.211 | 10.106–20.281 | 10.113–20.153 | 10.223–20.411 | 10.212–20.433 | 10.266–20.307 |

| Research Hypothesis | Result |

|---|---|

| H1. The career growth has a significant positive influence on the innovation performance of knowledge workers. | Support |

| H2. The career calling has a significant positive influence on the innovation performance of knowledge workers. | Support |

| H3. Inclusive leadership has a significant positive influence on the innovation performance of knowledge workers. | Support |

| H4. The craftsman spirit plays an intermediary role between career growth and innovation performance of knowledge workers. | Support |

| H5. The craftsman spirit plays an intermediary role between career calling and innovation performance of knowledge workers. | Support |

| H6. The craftsman spirit plays an intermediary role between inclusive leadership and innovation performance of knowledge workers. | Support |

| H7. Career calling has a positive regulating influence on the relationship between career growth and the craftsman spirit of knowledge workers. | Support |

| H8. Inclusive leadership has a positive regulating influence on the relationship between career growth and the craftsman spirit of knowledge workers. | Support |

| H9. The interaction between career calling and inclusive leadership has a positive regulating influence on the relationship between career growth and the craftsman spirit of knowledge workers. | Support |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, Y.; Liu, Y. The Influence of High-Performance Work Systems on the Innovation Performance of Knowledge Workers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215014

Ding Y, Liu Y. The Influence of High-Performance Work Systems on the Innovation Performance of Knowledge Workers. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):15014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215014

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Yu, and Yijun Liu. 2022. "The Influence of High-Performance Work Systems on the Innovation Performance of Knowledge Workers" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 15014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215014

APA StyleDing, Y., & Liu, Y. (2022). The Influence of High-Performance Work Systems on the Innovation Performance of Knowledge Workers. Sustainability, 14(22), 15014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215014