Transorbital Orbitocranial Penetrating Injury with an Iron Rod

Abstract

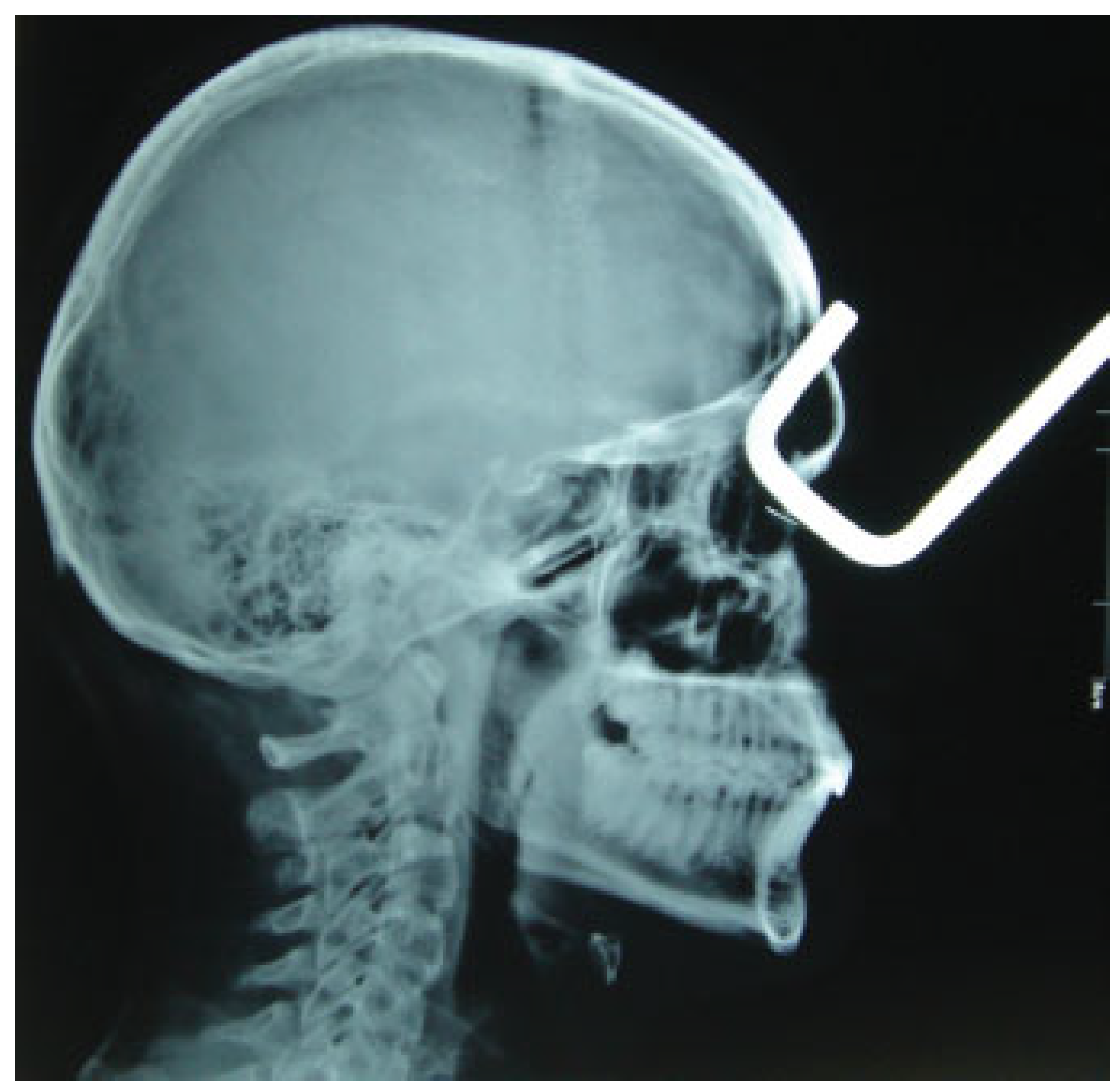

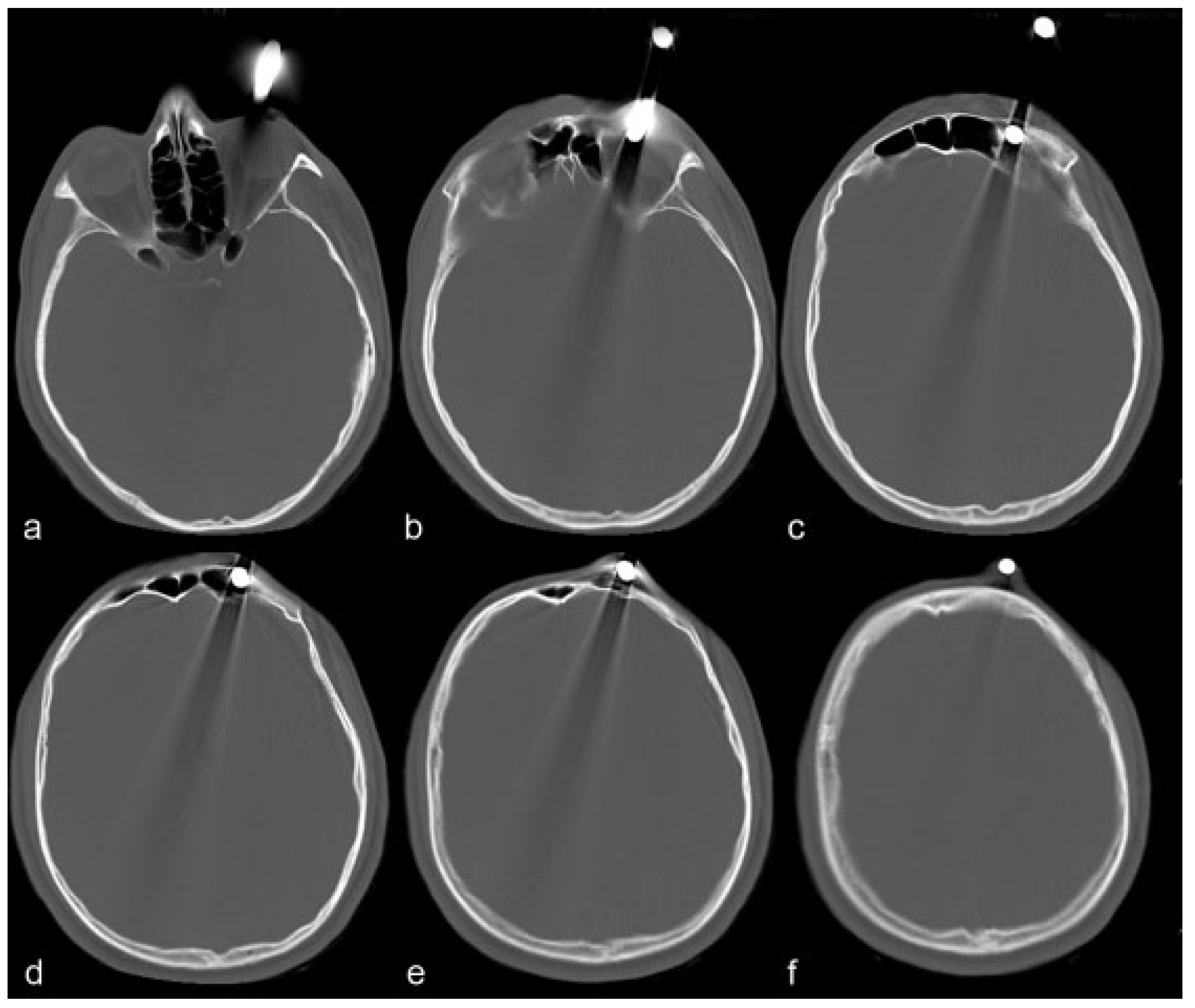

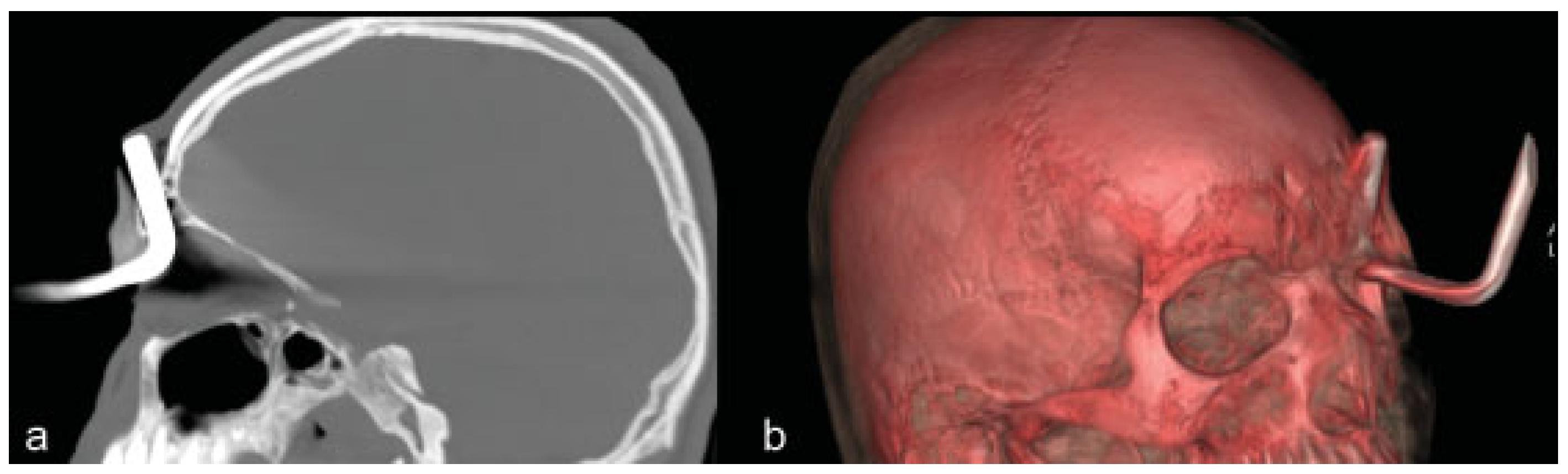

:Case Report

Discussion

Conclusions

References

- Agrawal, A.; Pratap, A.; Agrawal, C.S.; Kumar, A.; Rupakheti, S. Transorbital orbitocranial penetrating injury due to bicycle brake handle in a child. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2007, 43, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, W.S.; Saad, F.; Carvalhal, E.S.; De Amorim, R.L.O.; Figuereido, E.G.; Teeixera, M.J. Transorbital stab penetrating brain injury. Report of a case. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2009, 80, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huiszoon, W.B.; Noë, P.N.; Manten, A. Fatal transorbital penetrating intracranial injury caused by a bicycle hand brake. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulbaki, A.; Al-Otaibi, F.; Almalki, A.; Alohaly, N.; Baeesa, S. Transorbital craniocerebral occult penetrating injury with cerebral abscess complication. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. Med. 2012, 2012, 742186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, M.D.; Gunel, M.; Servat, J.J.; Levin, F. Extraction of fronto-orbital shower hook through transcranial orbitotomy. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma. Reconstr. 2014, 7, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasamo, S.; Asakura, T.; Kusumoto, K.; et al. Transorbital penetrating brain injury [in Japanese]. No Shinkei Geka 1992, 20, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Hata, H.; Hiratsuka, H.; Suganuma, Y.; Inaba, Y. Penetrating transorbital brain injury and intracranial foreign body (author’s transl) [in Japanese]. No Shinkei Geka 1978, 6, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan, M.S.; Indira Devi, B. Fatal penetrating orbitocerebral injury by bicycle brake handle. Indian. J. Neurotrauma 2007, 4, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Eseoğlu, M.; Güdü, B.O.; Demir, I. Transorbital orbitocranial penetrating injury caused by a metal bar. J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2012, 3, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Chiang, Y.H.; Hsieh, C.T.; Sun, J.M.; Hsia, C.C. Transorbital penetrating brain injury by branchlet: A rare case. J. Emerg. Med. 2011, 41, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.F.; Nikas, D.L.; Becker, D.P. Diagnosis and treatment of moderate and severe head injuries in adults. Youmans Neurological Surgery. Sounder Company 1996, 3, 1678–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Satyarthee, G.D.; Borkar, S.A.; Tripathi, A.K.; Sharma, B.S. Transorbital penetrating cerebral injury with a ceramic stone: Report of an interesting case. Neurol. India 2009, 57, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, C.; Kaliaperumal, C.; Jadun, C.K.; Dias, P.S. Transorbital intracranial penetrating injury-an anatomical classification. Surg. Neurol. 2009, 71, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turbin, R.E.; Maxwell, D.N.; Langer, P.D.; et al. Patterns of transorbital intracranial injury: A review and comparison of occult and nonoccult cases. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2006, 51, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, F.U.; Suri, A.; Mahapatra, A.K. Fatal penetrating brainstem injury caused by bicycle brake handle. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2005, 41, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Sukul, B.; Das, S.K. Fatal transorbital head injury by bicycle brake handle. J. Forensic. Leg. Med. 2009, 16, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seex, K.; Koppel, D.; Fitzpatrick, M.; Pyott, A. Trans-orbital penetrating head injury with a door key. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 1997, 25, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.L.; Lee, H.C.; Cho, D.Y. Management of transorbital brain injury. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2007, 70, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, A.A.; Eropkin, S.V.; Kornienko, V.N.; et al. Late diagnosis and removal of a large wooden foreign body in the cranio-orbital region. J. Craniofac Surg. 1996, 7, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.J.; Bancroft, L.W.; Kransdorf, M.J. Wooden foreign bodies: Imaging appearance. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002, 178, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E.; Gudeman, S.K.; Holgate, R.C.; Saunders, R.A. Penetrating intracranial wood wounds: Clinical limitations of computerized tomography. J. Neurosurg. 1988, 68, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Cho, K.H.; Shin, Y.S.; et al. Penetrating craniofacial injuries in children with wooden and metal chopsticks. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2006, 42, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, L.A.; Jarrett, W.H. Intracranial complications of penetrating orbital injuries. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1964, 71, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bursick, D.M.; Selker, R.G. Intracranial pencil injuries. Surg. Neurol. 1981, 16, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandertop, W.P.; de Vries, W.B.; van Swieten, J.; Ramos, L.M. Recurrent brain abscess due to an unexpected foreign body. Surg. Neurol. 1992, 37, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, G.E.; Ekinciler, O.F.; Karaküçük, S. Diagnosis and management of a biorbital pencil injury. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1993, 71, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, T.; Okuchi, K.; Nogami, K.; Hata, M.; Murao, Y. Transorbital penetrating injury by a chopstick—Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2001, 41, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, N.; Jamjoom, A.; Teimory, M. Penetrating orbitocranial injury. Injury 1991, 22, 326–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitakami, A.; Kirikae, M.; Kuroda, K.; Ogawa, A. Transorbital-transpetrosal penetrating cerebellar injury—Case report. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo) 1999, 39, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.G. Brain abscess related to metal fragments 47 years after head injury. Case report. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splavski, B.; Vranković, D.; Sarić, G.; et al. Early surgery and other indicators influencing the outcome of war missile skull base injuries. Surg. Neurol. 1998, 50, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Bhasker, S.K.; Singh, B.K. Transorbital penetrating brain injury with a large foreign body. J. Ophthalmic. Vis. Res. 2013, 8, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the author. The Author(s) 2015.

Share and Cite

Agrawal, A.; Reddy, V.U.; Kumar, S.S.; Hegde, K.V.; Rao, G.M. Transorbital Orbitocranial Penetrating Injury with an Iron Rod. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2016, 9, 145-148. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1551545

Agrawal A, Reddy VU, Kumar SS, Hegde KV, Rao GM. Transorbital Orbitocranial Penetrating Injury with an Iron Rod. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2016; 9(2):145-148. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1551545

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgrawal, Amit, V. Umamaheswara Reddy, S. Satish Kumar, Kishor V. Hegde, and G. Malleswara Rao. 2016. "Transorbital Orbitocranial Penetrating Injury with an Iron Rod" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 9, no. 2: 145-148. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1551545

APA StyleAgrawal, A., Reddy, V. U., Kumar, S. S., Hegde, K. V., & Rao, G. M. (2016). Transorbital Orbitocranial Penetrating Injury with an Iron Rod. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 9(2), 145-148. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1551545