This prospective cohort study therefore sets out to examine the recent trends in both the clinical and some epidemiological patterns of all facial injuries from all causes seen in our practice, a low resource one in a developing country. It also assessed the in-hospital treatment outcomes, and the levels of the patients’ satisfaction with this treatment in this setting.

Patients and Methods

This was a prospective cohort observational study spanning from January to December 2010. Clinical records of consecutive patients who were evaluated and treated for maxillofacial injuries by us were prospectively entered into predesigned forms. Information obtained included patients’ biodata and time of hospital presentation; location of the traumatic event; etiology of trauma;; use of personal protective devices in cases of RTC; types of the facial injuries (and associated nonfacial injuries); treatment provided; outcome of the treatment; and the duration of hospital stay. The socioeconomic classes were categorized as Class 1 (high social class), Classes 2 to 3 (middle class) and Classes 4 to 5 (low social classes) using a local scale by Oyedeji, 1985.[

13] Children were considered as individuals younger than 16 years.

In our unit, osseous maxillofacial injuries were usually diagnosed based on plain radiographs mainly as computed tomographic (CT) scan was not readily affordable to most patients. However, a cranial CT scanning was mandatory for all head injured patients. The plain radiographic views used were the occipitomental, true lateral and submentovertical views of the skull for upper and middle third facial fracture; the true lateral view of the jaws, and, left and right oblique views of the mandible for lower third facial fractures; and the Reverse Towne view for suspected condylar fractures.

The facial esthetic outcome of the treatment received was measured using a numeric rating scale which ranged from 0 to 10, 0 being the worst possible esthetic outcome and 10 the best possible outcome. The responses so obtained were then graded as follows: not satisfied for 0 to 3, fairly satisfied for 4 to 6, moderately satisfied for 7 to 8 and very satisfied for 9 to 10. The functional outcome was assessed based on the occlusion achieved according to the extent of cuspal interdigitation. The occlusion was considered very satisfactory when pretrauma cuspal interdigitation and incisal relationship involving the full complement of the dentition was achieved; moderately satisfactory when just the posterior teeth were fully interdigitated; and not satisfactory when either only the teeth on one side or none were interdigitated.

The SPSS version 18 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis. Descriptive data of categorical variables are presented in frequencies and proportions, and in tables. Continuous variables are presented in ranges, means ( standard deviation) and medians. The Chi-squared test was used to explore for associations between categorical variables; the Student t-test for continuous variables. The p value < 0.05 was set as level of statistical significance.

Results

A total of 259 consecutive patients of maxillofacialtraumawere studied. These accounted for 11.2% of the 2,308traumapatients seen during the study period. Of the 259 patients, 206 (79.5%) were males and 53 (20.5%) were females, male to female ratio was 3.9:1. The age ranged from 2 to 85 years; mean 32.21 years ( 16.588 years) and, median 30.0 years. There were 222 adults and adolescents, and 37 children. Thus, the pediatric population constituted 14.3%.

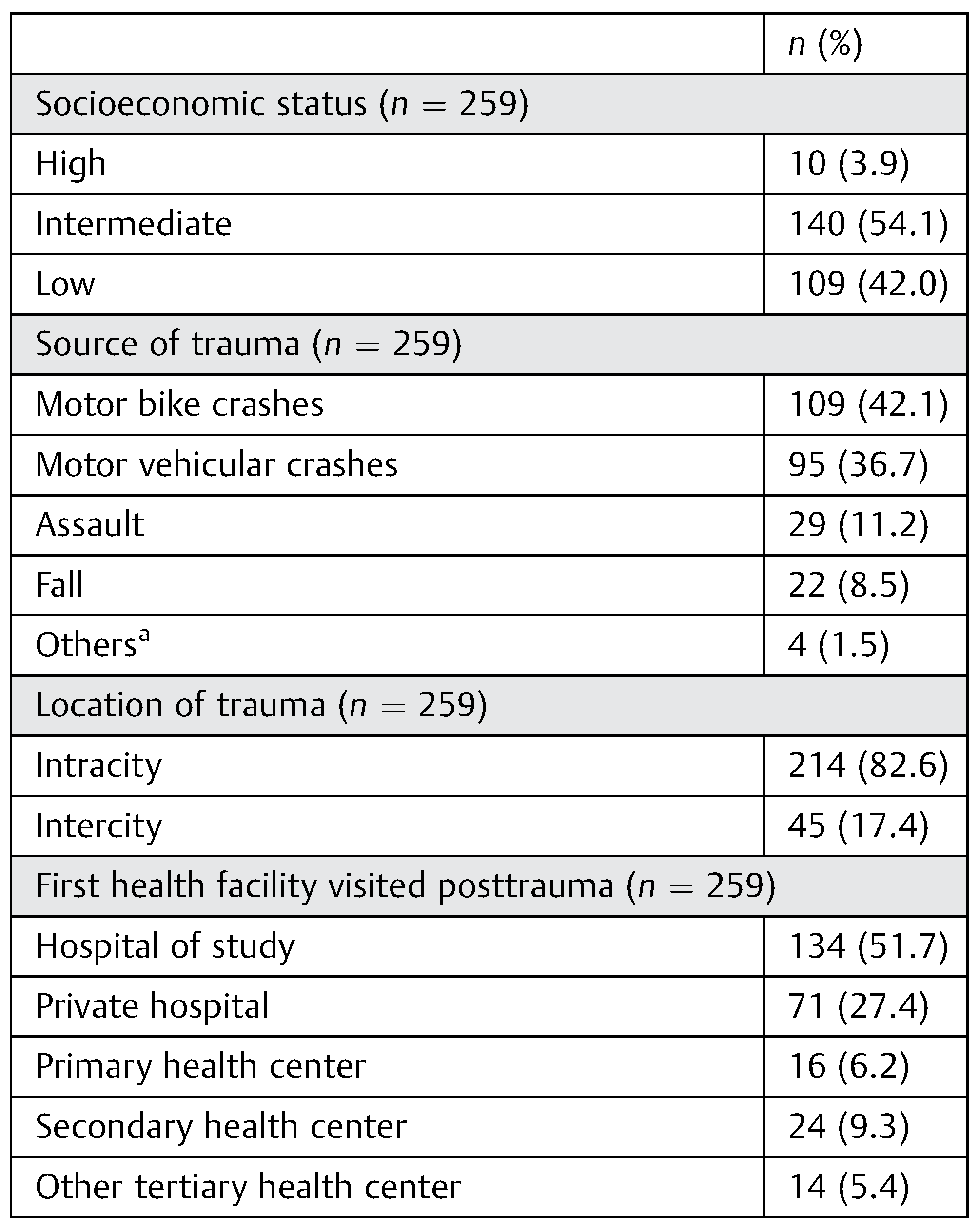

More than half (54.1%) of the patients were of the intermediate socioeconomic class.

Motor bike crashes were the commonest source oftraumain this study. They accounted for 42.1% of the patients (

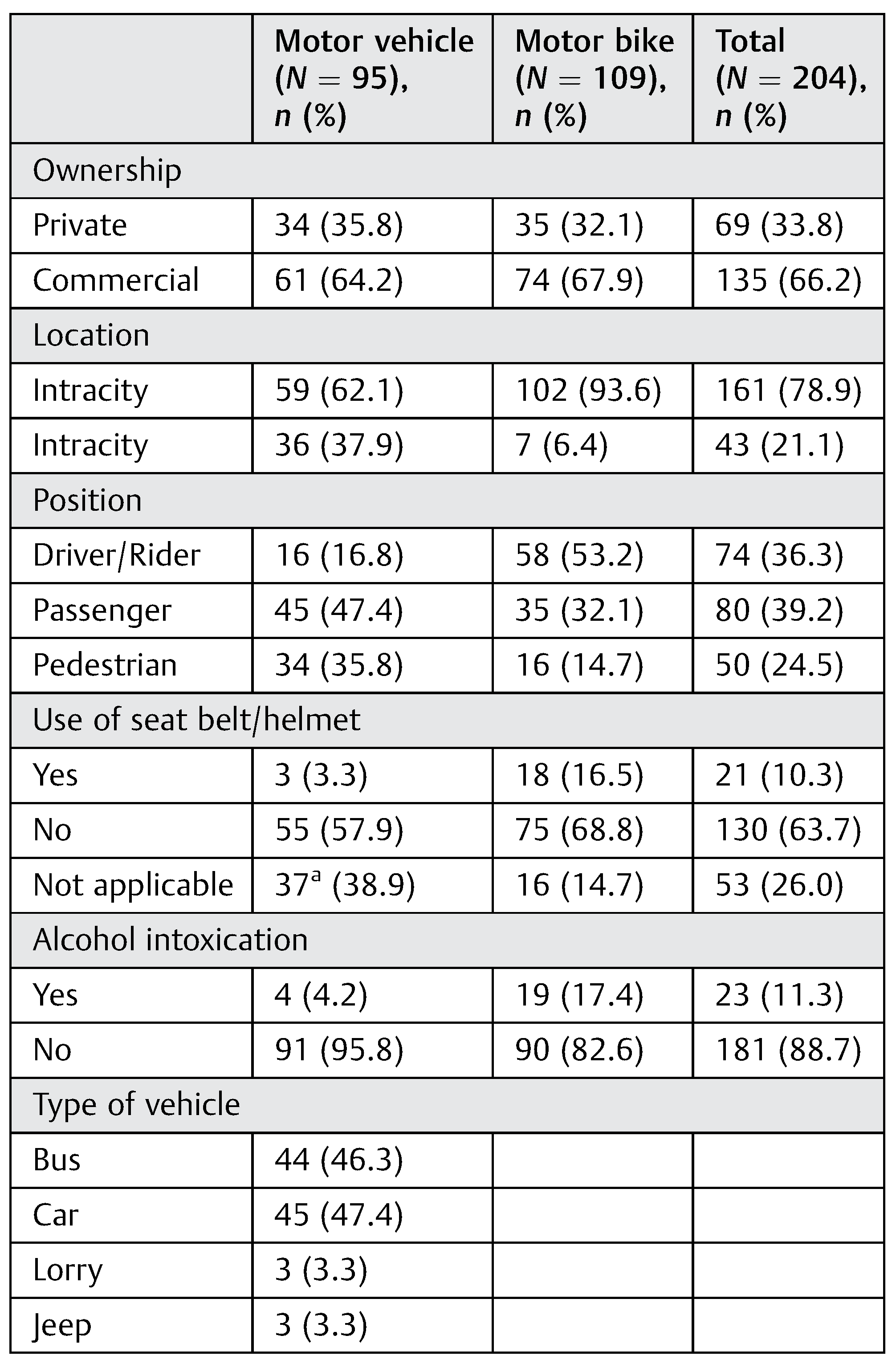

Table 1). RTC, involving motor vehicles and motor bikes jointly accounted for 78.8% of the patients; 66.2% of the involved automobiles were commercially owned and the commonest form of vehicles were cars,

Table 2. Only 10% claimed to be compliant with their behind-the-wheel protective device, that is, use of seat belts or helmets when the crashes occurred (

Table 2). Also, history of associated alcohol intoxication was positive in 11.3%.

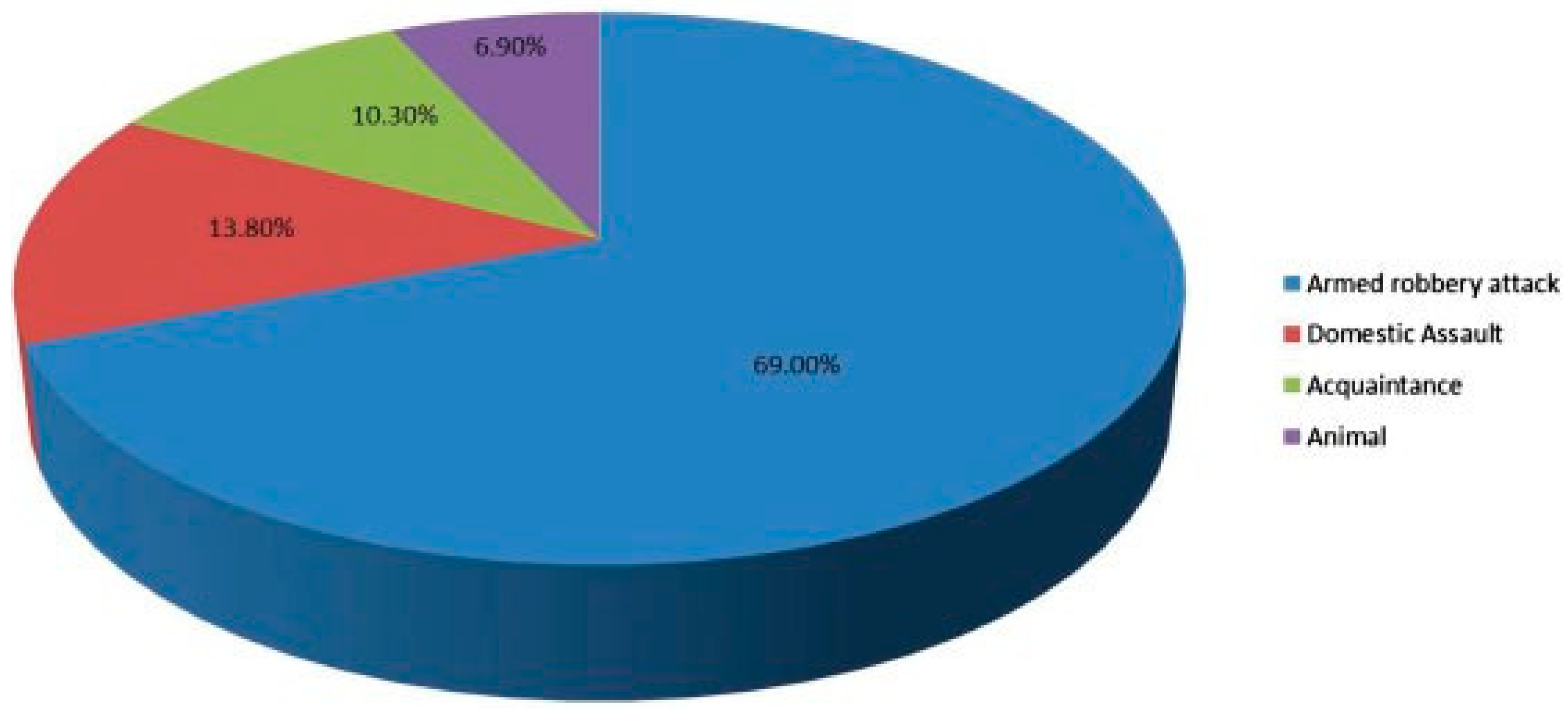

Armed robbery attack was the commonest form of assault. It represented 69.0% of this cause of facial trauma. Assault from close relations including male consorts came a distant second with 13.8% (

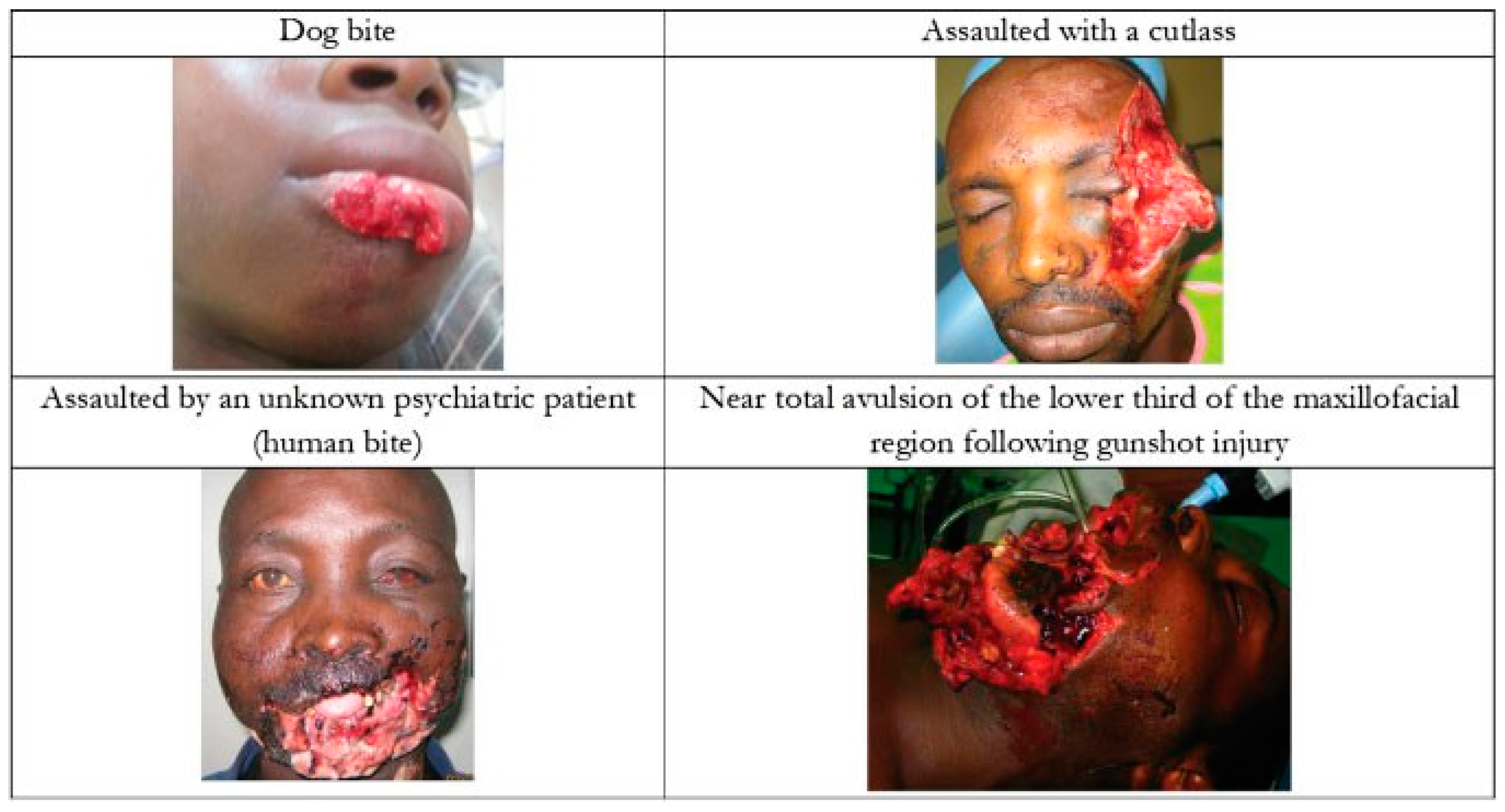

Figure 1). Injuries from assault were among the most gruesome of the cases seen in this study (

Figure 2). In this study, 72.8% of the cases of fall were recorded among patients in the first and second decades of life; those in the first decade accounted for 45.5% of the cases.

Majority of the traumatic events, 82.3%, occurred in intracity locations, that is within the large African metropolitan city (~ 5 million people) in which our clinical practice was based. But our health facility was the first port of call in only 51.7% (

Table 1). Nonetheless, the mean time to presentation in our hospital was about the same for the patients who were injured intracity, 17.10 24.05 hours, and those without, (i.e., intercity), 17.46 25.07 hours (

p ¼ 0.93). The mean time to presentation for treatment of their facial injuries was highly significantly much shorter,

p < 0.001, in those who came primarily to our unit than in those who had first presented in some other health facilities before being turned over to our service, (5.73 12.87 vs. 29.42 27.32, 95% confidence interval [CI] —28.86 to —18.52) hours.

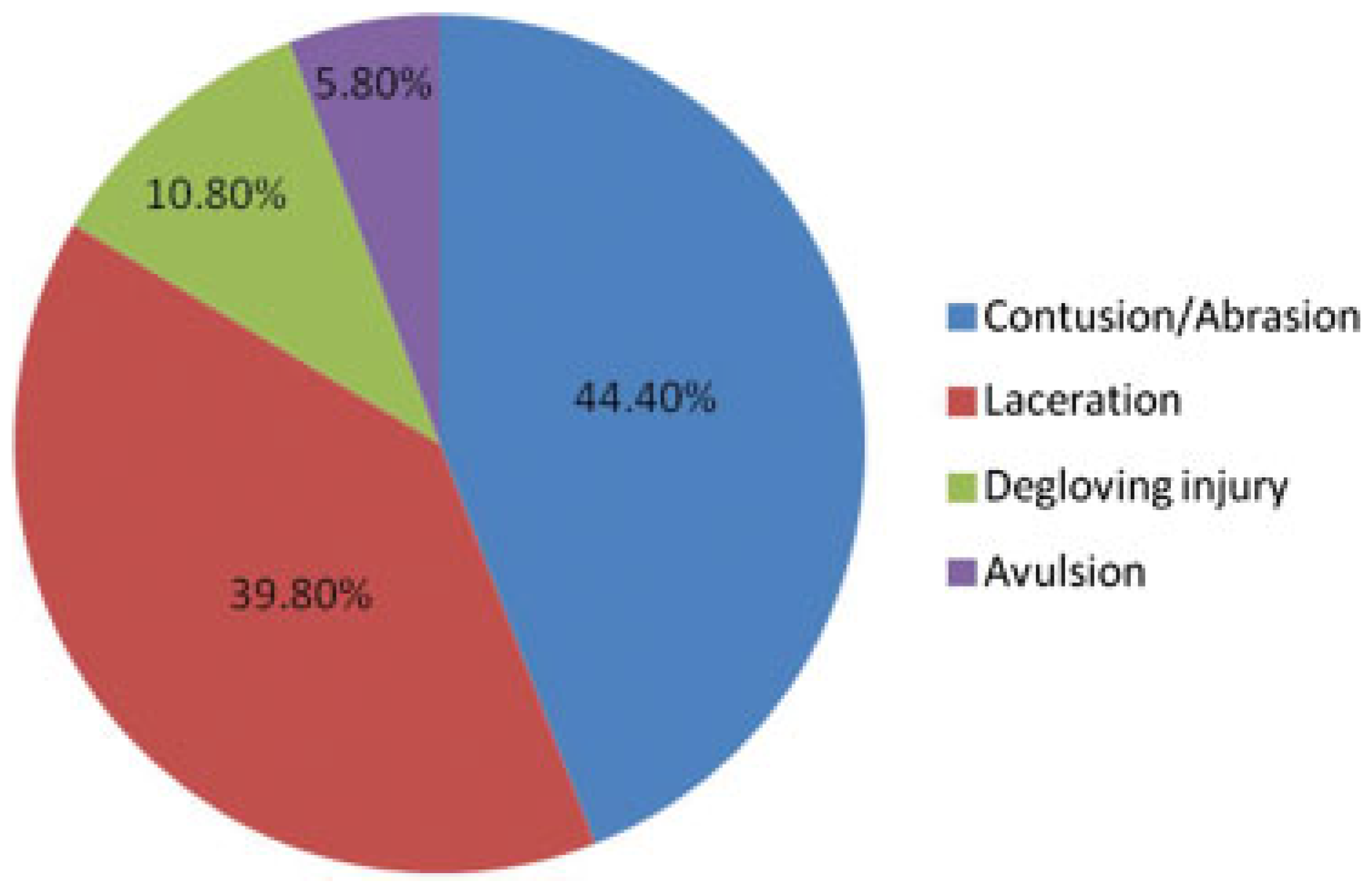

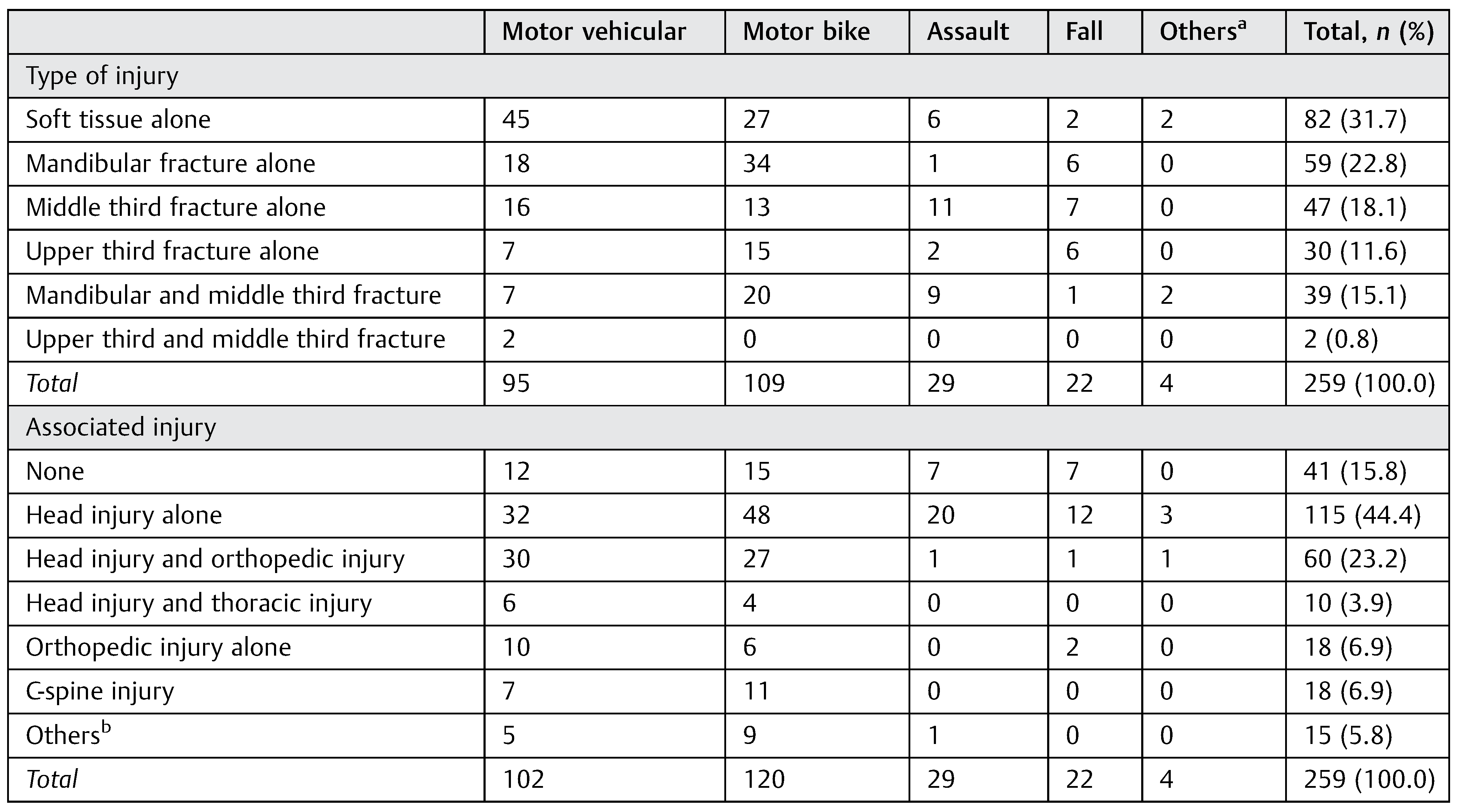

Contusions and or abrasions were the commonest types of soft tissue injury (44.4%) and the commonest site, approximately 40%, for these injuries was the cheek/zygomaticotemporal region. About one third (31.7%) of the patients sustained soft tissue injuries alone. (

Figure 3,

Table 3 and

Table 4). Solitary facial skeletal fracture involved the mandibular bone most commonly (22.8%). The fracture of the mandibular body had the highest frequency among the mandibular fractures while zygomatic complex fracture was the commonest for the midfacial fractures (

Table 4).

One other noteworthy finding of this prospective cohort is that only 15.8% of the study population had no injuries in any other body system apart from the maxillofacial ones. The rest of them, overwhelming majority, sustained associated injuries in the other body systems including the head and neck, chest and abdomen, and the muscular–skeletal system,

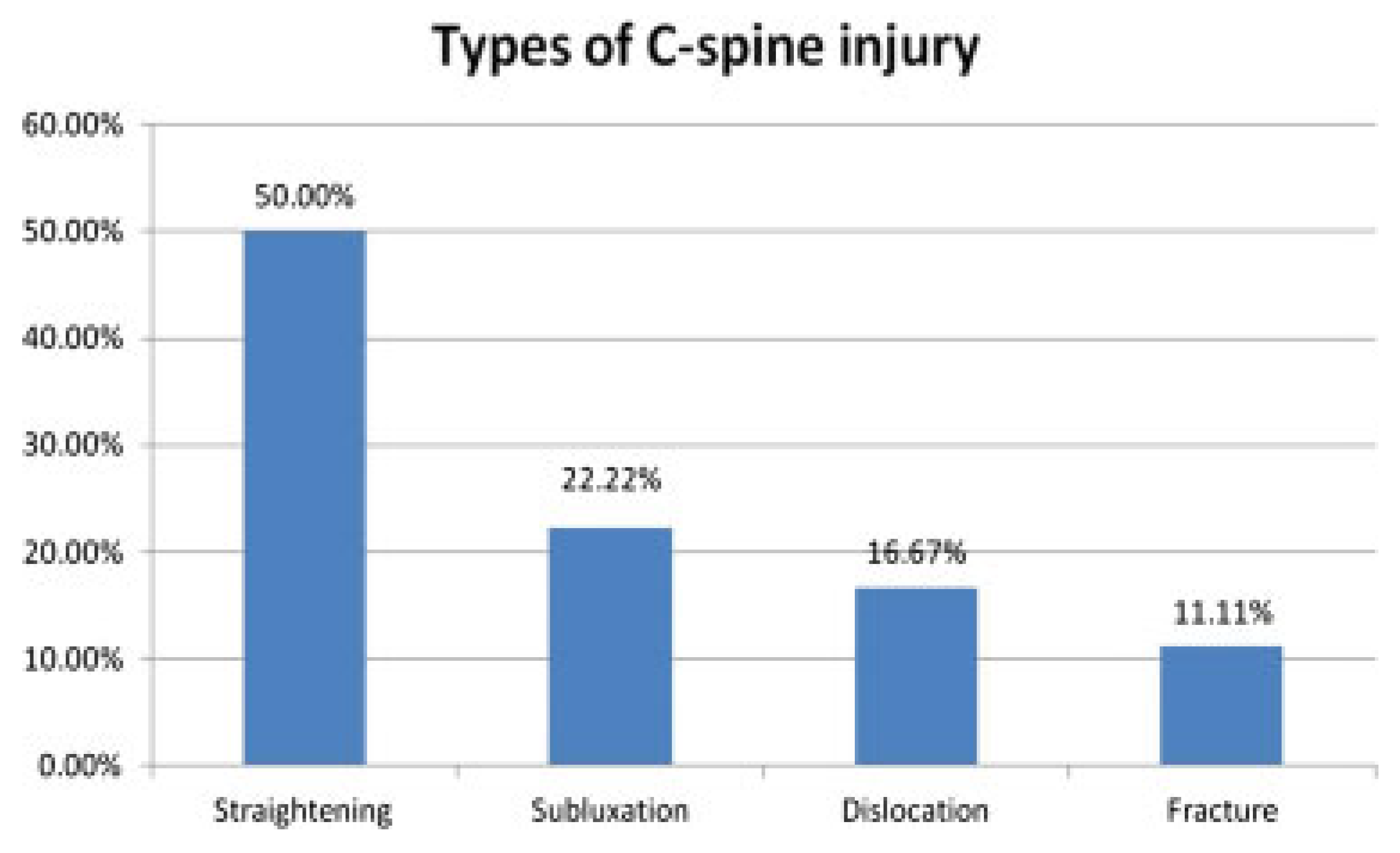

Table 3. What is more, head injury had the highest frequency, 44%, amongst these associated injuries. Mild head injury accounted for the commonest type of associated head injury (52.5%); while straightening was the commonest type of C spine injury seen (

Figure 4).

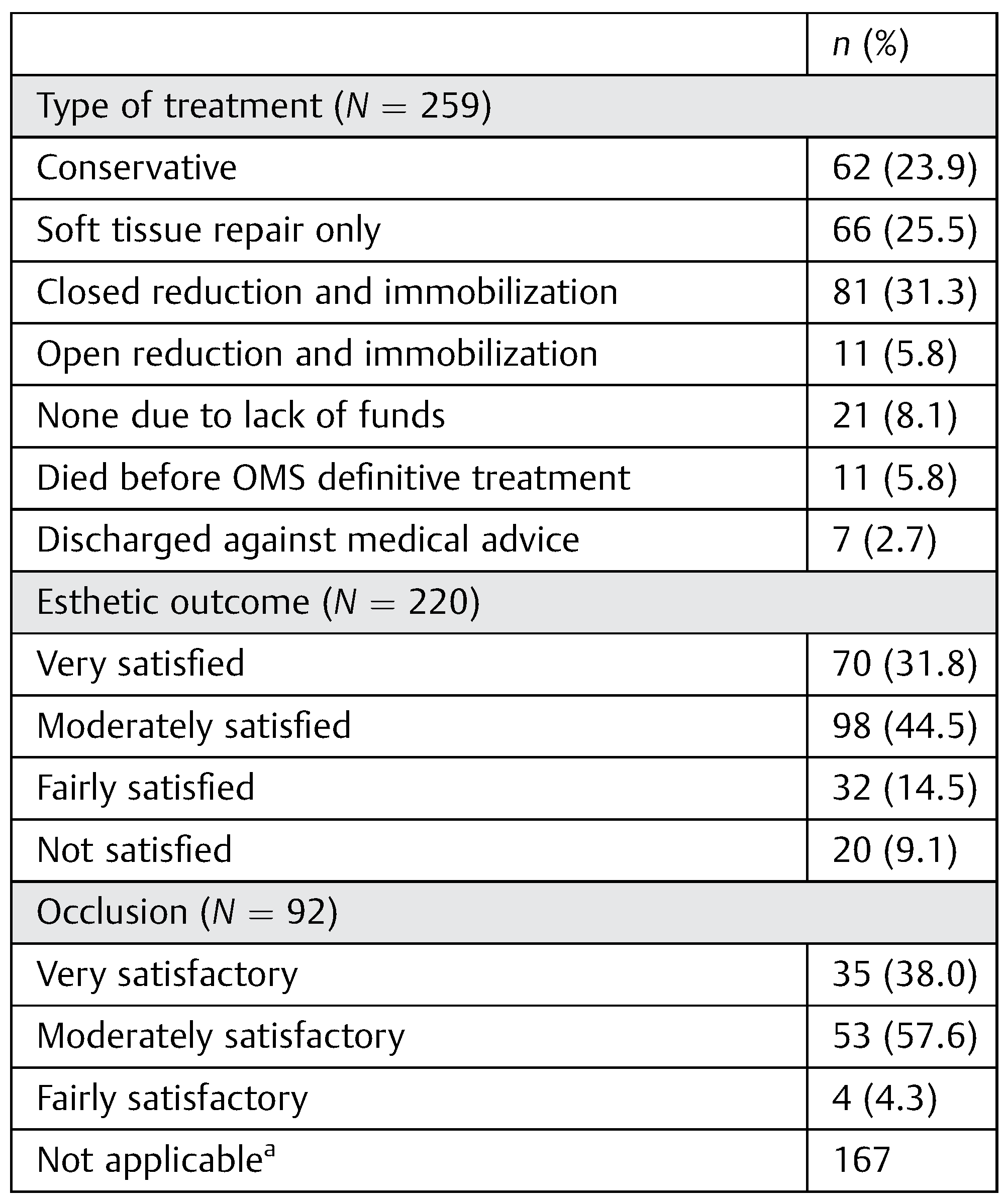

Among the 92 of 259 patients (37.1%) who had active treatment of their maxillofacial skeletal injuries in this study, closed reduction and immobilization was deployed in 81 (88.0% of this treatment group); and, open surgical reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in only 11 (12.0%) patients. This was often due, in many cases in the former group, to the fact of the nonaffordability of the proposed surgical ORIF.

Of the 220 patients for whom the response was available more than three quarters reported being very or at least moderately satisfied with the esthetic outcome of the treatment received. And more than 90% of those who had active treatment of their maxillofacial skeletal injury reported very satisfactory or moderately satisfactory functional outcome (

Table 5).

Thirty-nine patients were not admitted into the wards but stayed in the hospital’s emergency section for varying number of days which ranged from 0.3 to 8.0 days, mean of 3.0 days ( 1.744 days) and median 3.0 days. For the entire study population however, the mean length of hospital stay was 12.6 ( 4.423 days) days. This increased to 16.6 ( 9.886 days) days in those patients with associated injuries in other body systems apart from the maxillofacial region; and reduced to 7.8 ( 5.222 days) days in those without associated injuries, p < 0.001 (95% CI, —11.879 to —5.634)

Discussion

In the developed world, interpersonal violence and sporting activities rank high among the causes of maxillofacial trauma.[

14] This is in contrast to developing countries where RTC

top the charts, a finding that has been documented by some earlier Nigerian authors.[

2,

3,

6,

10,

15,

16] The persistence of RTC as the leading cause of maxillofacialtraumain our environment has been attributed to the poor state of roads and the nonenforcement of traffic rules.[

3,

4] However, authors in Northern Nigeria have documented assault as the commonest cause of maxillofacial injury.[

1] This they attributed to increased violent tendency because of the high unemployment rate among the youths and the downward trend of the Nigerian economy.

Young adults within the third decade of life have universally been the ones most vulnerable to trauma.[

2,

3] In contrast, pediatric maxillofacial injuries appear uncommon with incidence ranging between 1 and 14%.[

17,

18,

19] This lower incidence was similarly noted in our study and has been attributed to socioenvironmental, general physical and craniomaxillofacial anatomic factors in the pediatric age groups including a higher cranial to facial skeleton size, softer and more elastic bones, protective thick soft tissues, and lack of pneumatization of the paranasal sinuses.[

17] It has also been suggested that incomplete communication with a pediatric patient, inadequate radiographic examination in the restless child and or late presentation of the patient by family or guardian may contribute to injuries being missed in this group of patients.[

17]

Of the two genders, the male has usually hitherto been noted to be two to three times more involved in traumaticmaxillofacial injuries, irrespective of the etiology and age group.[

1,

3,

14,

19]

However, female involvement in maxillofacial injuries appears to be on the rise in the current era. The male to female ratio of 3.9:1 in this study fell short of the previous documentation of 7.6:1 and 5.3:1 from this same center.[

16,

20] This may be due to the fact that more women are engaging in outdoor activities due to many contemporary socioeconomic reasons.

Most of the traumatic events in this study occurred in intracity locations. This is in contrast to the findings of Fasola et al 10 years ago at the same center.[

3] It is possible that there are more maxillofacial specialists in other centers in surrounding cities wheretraumapatients outside the city of study are taken, thereby reducing the number of patients seen in our tertiary center.

Presentations in hospitals within 24 hours of injury have been reported by other authors. Ugboko et al[

2] reported that one-third of their patients reported within this period whereas Solagberu et al[

4] reported that 88.4% of their patients reported within the same period. About half of our own patient population reported within 6 hours of injuries which may not be unrelated to the fact that about the same percentage of patients presented at our center as the first port of call. Meanwhile, more than 50% of the remaining half had previously visited privately owned health facilities before presenting at our center for definitive treatment. Also, utilization of public primary and secondary health centers in the management of maxillofacialtraumaappears to be minimal among this patient cohort, even for otherwise minor softtissue injuries. Less than a quarter of our patient population reported in these facilities. Speculative reasons for the underutilization of other health centers may include lack of manpower and facilities in those places. However, further studies will be required to determine why primary and secondary health centers are not being used to allow a tertiary center such as ours focus on more complex cases.

Though RTC still remain the commonest etiology of maxillofacialtraumain our environment, the type of vehicle most commonly involved has changed. About 30 years ago, lorries were commonly used to commute people and goods from one place to another in our geographical area, and therefore were the most commonly involved in RTC.[

10] Two decades later, cars in the form of taxis became the most commonly used and then accounted for the highest proportion of RTC at that time.[

1,

2,

3] Today, the motorcycles have become a very prominent feature of the public transportation landscape. Maxillofacial injuries sustained as a consequence of motorcycle crashes can be quite extensive as illustrated in

Figure 5, most especially so, because they are by default ridden without protective helmets. The incentives to their use for this purpose include the fact that they can negotiate unmotorable roads and move faster within and without traffic gridlocks; increasing volumes of informal trading activities in the evolving societies of the developing world requiring faster means of commercial transportation; and the fact that the motorcycle transportation “business” is relatively inexpensive to get running for the teeming mass of the unemployed youths in these climes.[

4] Furthermore, it is essentially an unregulated transport system; it also appears to be for all comers; hence, individuals can become commercial riders without undergoing any necessary prelicensing tests.[

4] Also, many of these riders are young men who have a tendency to be daring, and reckless.[

3,

4,

16]

This chaotic transport situation has not failed to exact its toll on the society. Motor cycle crashes, especially intracity, are increasingly becoming major contributors of much of thetraumaburdens in the developing world. In this study, much unlike previous ones, half of the patients involved in RTC were motorcycle crashes, significantly higher than in the reports of other authors which ranged from 10.3 to 45.5%.[

3,

4,

16]

While Solagberu et al[

4] did not record any use of helmet in their study, 16.5% of the patients involved in motorcycle crashes in this study claimed they wore helmets, whereas only 3.3% of the motor vehicular crash victims had seat belts on at the time of injury. The use of seat belts in this study is very small compared with the observation of Cummings in the United States in which he reported a 39.1% use of seat belts in crashes that involved at least one death.[

21] There is therefore an urgent need for the enforcement of the use of these protective devices in our country as they have been found to reduce the incidence of facialtraumaduring a motor vehicular crash by as much as from approximately 17 to 8%.[

22] Alcohol intoxication can impair both mental alertness and motor coordination thus constituting a risk factor for RTC. The frequency of alcohol intoxication recorded in this study appears low in comparison with previous studies such as 31.0%.[

23] However, the true incidence of alcohol intoxication in the study is difficult to confirm as the blood alcohol meter required to do this was not available in our practice. Those considered to be under the influence of alcohol either gave a positive history or alcohol was perceived in their breath during the course of examination.

The frequency of assault as the facial injury causingtraumawas second to RTC in this study; and armed robbery attack was the commonest type of the assault. This is as been similarly observed by Olasoji et al,[

1] but in contrast to the observation of some other authors where spousal violence was described as the commonest.[

24] Assault by animals was however limited to two cases of dog bite. This incidence of animal assault appears low compared with the Northern region of the same country where knocks from cows have been reported to be a very common form of attack by an animal.[

25]

Fall is the usually reported commonest etiology of maxillofacial fracture in individuals younger than 16 years.[

18] In our study, majority of the victims of fall were also children in the first decade of life. This high prevalence of fall among children may be because of the fact that children are more involved in activities such as playing, running, jumping both at school, and while running errands.[

26] It may also be that their motor coordination is not yet optimal and as such they are a group of people who can stumble and fall easily. Maxillofacial injuries following falls have been hardly reported before in the literature from our geographical region.

The pattern of maxillofacial injuries seen in this study ranged from soft tissue contusions and minimal abrasions to severe hemifacial avulsions as illustrated in

Figure 5. But laceration was the commonest type of soft tissue injury in this study, corroborating the findings of previous authors.[

2,

27,

28] The commonest site for the soft tissue injuries was the cheek and the zygomaticotemporal region with almost 50% presenting as lacerations (

Table 4 and

Figure 3). The site of common occurrence is similar to the findings of other authors from the same center.[

1]

The mandible has been documented to be the most common bone fractured in the maxillofacial complex following trauma.[

1,

2,

6,

10] This was similarly found in our study.

Overall 90 cases involved the mandible, 39.8% of which occurred with midfacial fractures. This was much higher than the 8.0% dual occurrence recorded by Olasoji et al in 2002.[

1] The body of the mandible has been previously documented to be the most fractured site of the mandible.[

1,

2,

10] This was similarly observed in our study.

In another light, the zygomatic complex has usually been documented to be the commonest site of midfacial fracture by local authors.[

1,

6,

16,

29] This was followed by the Le Fort II fracture.[

16,

29] However, some other authors have documented nasal complex fracture as the commonest midfacial fracture followed by zygomatic complex fracture.[

30] This difference may be attributable to the fact that plain radiograph, which is the most common mode of imaging in our environment may not readily detect nasal complex fractures.

Trauma to the maxillofacial region poses a significant challenge to both the patient and surgeon.[

31] This is especially so when delay in treatment has resulted in malunion or malpositioning of tissues of the maxillofacial complex. Because of severe logistics constraints of our low-resource practice closed reduction and immobilization with the use of suspension wires still remains the commonest type of treatment for maxillofacial fractures.[

1,

2] However, open reduction and internal fixation with bone plates are now being used a little more frequently compared with the 70s and 80s when there was no record of their use at all.[

2,

6,

10]

The local literature was much sparse as regards the outcome of treatment of patients who sustained maxillofacial injuries. Chung et al reported an 83.8% satisfaction with esthetics and only 4.8% malocclusion rate for their analysis of 105 patients treated for maxillofacial injuries.[

32] This degree of satisfaction is much higher than the ones recorded in our study and may be attributable to our inability to treat these fractures soon after the injury as the financial demand of having a surgical intervention often delayed the time of definitive treatment despite an early presentation. This is a sad feature of the out-of-pocket private funding of all aspects of health care in our country. Also, the closed method of treatment employed majorly for the maxillofacial fracture would have prevented a direct and probably more accurate reduction of the fractures thus preventing the achievement of optimum esthetic and functional results. As shown in

Table 5, the definitive treatments could not be achieved in as many as 40 patients (16.6%) for various logistic constraints of our low-resource health system alluded to earlier.

It was observed that pretrauma occlusion was achievable in only one third of the patients (very satisfied,

Table 5). This most likely would be because of the fact that very few of the patients had their treatment done as open reduction and immobilization which is a more accurate method of treating fractures. Though about half of the patient population in our study were of the intermediate socioeconomic class, this categorization has to be considered in the context of the fact that Nigeria is a developing country with a human development index of 0.471. This means Nigeria is ranked as 153 of 187 comparable countries (1990–2013 Human Development Reports by UNICEF). Thus, affordability of an expensive treatment that is not life threatening is considered by most to be unattainable despite counselling on the obvious benefits of an open reduction over closed reduction. Unfortunately, the National Health Insurance Scheme is still at its developmental phase and most of our patients could not benefit from it, therefore the main source of funding for treatment was out-of-pocket funding.

The duration of time spent on admission in a hospital following an injury can be a measure of the socioeconomic impact of that injury on an individual’s life. This is important because it translates to a period of being out of work as well as increased responsibilities on friends and relatives who have to visit the hospital almost every day of the admission to ensure that all needs are catered for. A period of about 2 weeks is required for admission of a patient with maxillofacial injury in our environment but this reduces to about a week if patient did not sustain associated injury to other regions of the body. For reasons, not addressed in this study, some patients sometimes spent an average of 3 days in the accident and emergency section before being able to be admitted to the wards or discharged from the hospital, as the case may be.

The proportion of patients who were discharged against medical advice was much lower than 29.8% reported by Solagberu et al[

4] but is similar to the 4.2% reported by Odelowo.[

33]

Although RTC is a major etiology of maxillofacial trauma, assault and fall represent a significant etiology of maxillofacialtraumaand should be studied further. Maxillofacialtraumaposes a significant socioeconomic burden on affected individuals which is made worse by the presence of associated injuries. The outcome of the current management standard of care of maxillofacialtraumain our practice is not very satisfactory due mainly to the logistics constraints of our patient population. Thus, there is a need for more objective mode of treatment such as open reduction and internal fixation. More local studies on the outcome of management of maxillofacialtraumaare also called for. This will not only improve the available literature on them but should also assist as an audit of management of these injuries in this region. It would especially be a great aid in the formulation of relevant health policies for this neglected public health problem.