Conventional access to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) involves a composite preauricular incision [

1]. Tortuous superficial temporal vessels are encountered multiple times within this plane, and the capsule and condyle can be difficult to visualize where it is located deeply beneath masseter attachments. Significant retraction is required merely to expose the condyle, and visualization of the coronoid and anterior ramus is not typically possible. Such continuous anterior retraction in an attempt to improve exposure portends possible neuropraxia to the frontal branch of the facial nerve when using this composite technique.

Moreover, the preauricular scar is unsightly, frequently not healing in an aesthetic fashion. Other approaches have been reported, including the postauricular [

2,

3] and endaural [

3]. However, these also carry several disadvantages, including extended temporal scarring and reports of perichondritis [

4]

Facial skin flaps, for cosmetic procedures (rhytidectomy), parotidectomy, and facial reanimation, have been described to be concealed along facial subunits while providing maximum surgical access [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Rhytidectomy dissection techniques also typically entail manipulation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) layer, for tissue redraping [

9] The benefit of creating component tissue layers can be applied to TMJ exposure.

We report on an anterior hairline, preauricular posttragal incision, in conjunction with a deep SMAS flap to approach the TMJ. Importantly, this approach allows for wide surgical access, including the entire coronoid process, and facilitates protection of the facial nerve and superficial temporal vessels, while enhancing cosmesis.

Methods

All patients who underwent a component approach to the TMJ and coronoid were identified and included in this report. All patients were operated on by a single surgeon (D.S.) from June 2011 to July 2012 (

Table 1).

Technique

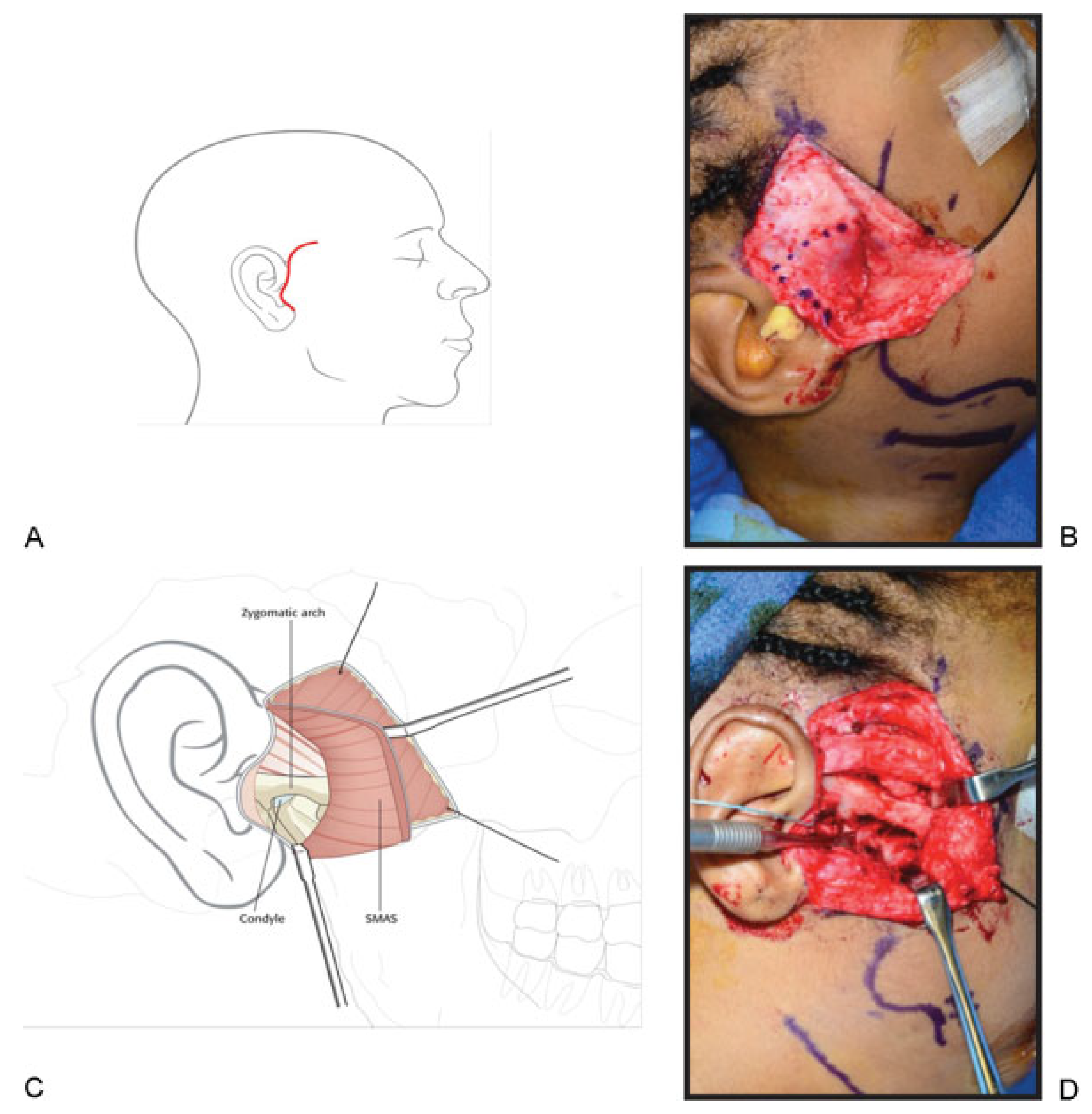

The surgical field is prepped and local anesthesia administered. A beveled incision is made from the anterior temporal hairline to the root of the helix, then carried along the preauricular crease to the retrotragal location, terminating at the ear lobule-posterior cheek junction (“reverse hockey stick”) (

Figure 1A). The skin flap is raised subcutaneously toward the malar eminence and the expected trajectory of the frontal branch is then demarcated with surgical ink atop the SMAS (pretragal to lateral brow) [

10] (

Figure 1B). A deep SMAS flap is raised beginning horizontally above the zygomatic arch and coursing preauricularly (

Figure 1C). This is subperiosteal along the arch, and incorporates the superior extent of parotideomasseteric fascia. The masseter is then divided from the attachments on the arch to expose the TMJ capsule (

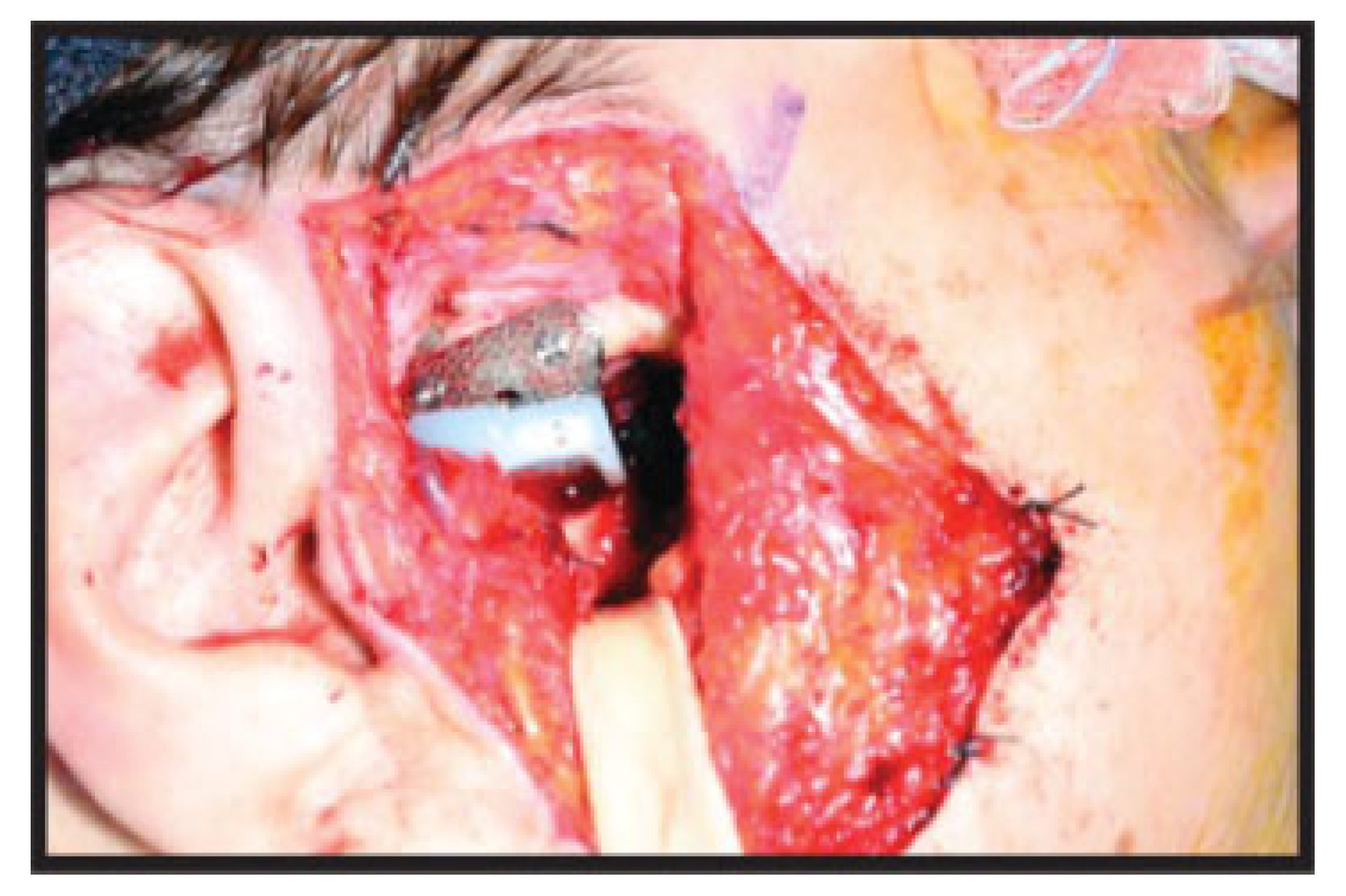

Figure 1C,D). The capsule is then incised and the lateral pole of the condyle encountered. Dissection is continued posteriorly toward the neck and anteriorly to the sigmoid. The coronoid can then be exposed following additional takedown of the masseter muscle and subper-iosteal dissection anteriorly. Alloplastic or autologous reconstruction is then undertaken (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). We present four cases of the component approach to the TMJ and coronoid process (

Table 1). Follow-up demonstrated preserved cosmesis and facial nerve function in all cases (

Figure 4).

Discussion

Reconstruction of TMJ structures is challenging for many reasons, not the least of which is the difficulty obtaining sufficient exposure. The ideal approach allows for wide access, avoidance of vital structures, and optimal esthetics. Maintaining the facial tissue planes together, as a composite flap, limits easy exposure of the sigmoid and anterior structures of the TMJ, as well as the coronoid. More tension is required to retract this composite tissue anteriorly risking traction on the facial nerve. Even with such robust retraction, this conventional approach allows only minimal exposure, with pertinent structures located deep in the field and visibility for dissection and hemostasis limited. In addition to the unsightly incision location, the continued tension from retraction can traumatize the skin edges, perhaps increasing scarring. Recently, Pau et al. described a modified preauricular approach to include a trans-tragal extension [

11]. This modification provided greater access to the condyle but may not reduce the need for retraction (1/16 patients developed temporary impairment of a branch of the facial nerve) and access to the coronoid is insufficient.

Incisions posterior to the ear with dissection through the cartilaginous auditory canal have also been described. The resulting flap from this postauricular design is elevated and reflected anteriorly, providing excellent exposure of the lateral and deep structures of the TMJ; however, serious complications of the external auditory canal (EAC) including stenosis, infection, and necrosis, as well as prolonged operating time are associated with this procedure [

2] Alternatively, an incision from the inferior portion of the anterior meatal wall extending superiorly to the preauricular crease and through the soft tissue into the temporal hair region has been used clinically. This endaural approach provides exposure of the lateral and posterior TMJ with limited anterior exposure [

3] In both the postauricular and endaural approaches, the facial nerve is well protected within the flap, but coronoid access remains limited and canal stenosis can occur.

Shortcomings of the conventional preauricular exposure are addressed in our procedural design by including the anterior temporal hairline and extending the incision posttragally. This rhytidectomy-styled dissection separates anatomic components allowing for deep SMAS flap elevation as well as increased exposure of the TMJ, condyle, and coronoid process. Improved visualization decreases the need for retraction and consequent risk of injury to the facial nerve. Additionally, posttragal extension of the incision conceals a significant portion of the scar, effectively reducing scar visibility. The incision within the preauricular crease utilizes the natural contours of the ear, further reducing scar visibility, and a beveled incision perpendicular to the underlying hair follicles in the temporal hair-bearing region allows preservation and regrowth of hair anterior and posterior to the incision [

6,

12]. Finally, with increased exposure of all structures of the TMJ, this approach proves to be flexible and versatile in its surgical application including acquired or congenital defects.

Conclusion

We report on a component approach to the TMJ and coronoid process, and demonstrate implementation in four heterogeneous cases. The rhytidectomy incision with a deep SMAS flap improves access (to the TMJ, sigmoid, and coronoid process), lessens the amount of retraction required (and thus risk of damage to the facial nerve), and creates a more inconspicuous scar.