The ophthalmic subspecialty of orbit and oculofacial surgery covers a wide range of surgeries which includes the eyelids, lacrimal, orbital, and adjacent nasal spaces of the oculofacial skeleton. As such, practices differ according to training and personal experience, location of practice which affects the availability of supporting services such as radiological and pathological expertise and personal success rates. These factors result in a wide range of practice differences which are evolving quickly aided by the rapid advances of new technology. There have been multiple large survey-based studies conducted in developed countries such as Australia, United Kingdom, and the United States [

1,

2,

3,

4]. They have helped to summarize the current “flavor” of oculofacial surgical practices in the region and provide insight to the similarities or differences in the management of common oculofacial-related conditions. However, to our current knowledge, there have not been similar surveys on the current common practices among oculofacial surgeons in the Asia-Pacific region.

Methods

Our study was a web-based anonymous survey conducted between May 2012 and December 2012. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, with ethics approval obtained from the National Healthcare Group Institutional Review Board.

The online survey was designed to include questions with multiple choices and open-ended free answers if appropriate. The survey was created using the online software program SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey.com, Portland, OR). The participants were invited to take part via e-mail invitation and all responses were kept anonymous. The e-mail addresses were obtained from the Asia-Pacific Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (APSOPRS) Web site which included the contacts of all its registered members. However, the authors recognized that the APSOPRS register only included a select group of oculofacial surgeons who subscribed to the society. To extend the survey to other oculofacial surgeons in the Asia-Pacific region, invitations were also sent to oculofacial surgeons who are known to the authors of this study. The first invitation was sent out on May 1, 2012, to a total of 131 e-mail addresses and responses were collected for the next 3 weeks. Subsequently, a second invitation was re-sent to all the e-mail addresses again to encourage participation by those who have not responded and responses were collected for a further 3 weeks. The collection of responses ended on December 31, 2012. Unanswered questions were excluded from further analysis. All the responses were collated and analyses were performed using the statistical software, Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, version 18.0, Chicago, IL).

The questionnaire was designed after a detailed literature review of previous oculofacial surveys with input from an experienced oculofacial surgeon (G.S.). The questions, based on the participants’ practice patterns, are listed as follows.

Training and Practice

Have you had any formal oculofacial fellowship training?

Did you receive your training locally or internationally?

With regard to your oculofacial practice, are you practicing full time, part-time, or minimal?

With regard to your oculofacial practice, are you in solo, group, multispecialty, or institutional practice?

What is the most common type of orbital surgery you performed?

Orbital Floor Fracture

- 6.

Of all orbital floor fractures, what is the estimated percentage of blowout versus non-blowout fractures?

- 7.

If surgical repair was indicated for adult orbital floor blowout fracture, when is your preferred time for surgical intervention?

- 8.

What is your choice of implant for adult blowout fracture repair?

- 9.

For pediatric blowout fractures without soft tissue entrapment, when is your preferred time for intervention?

- 10.

What is your choice of implant for pediatric blowout fracture repair?

- 11.

What is your preferred approach for orbital floor blowout fracture repair?

- 12.

What is the most common complication following orbital wall fracture repair?

- 13.

How long do you routinely follow-up uncomplicated orbital wall fracture patients?

Results

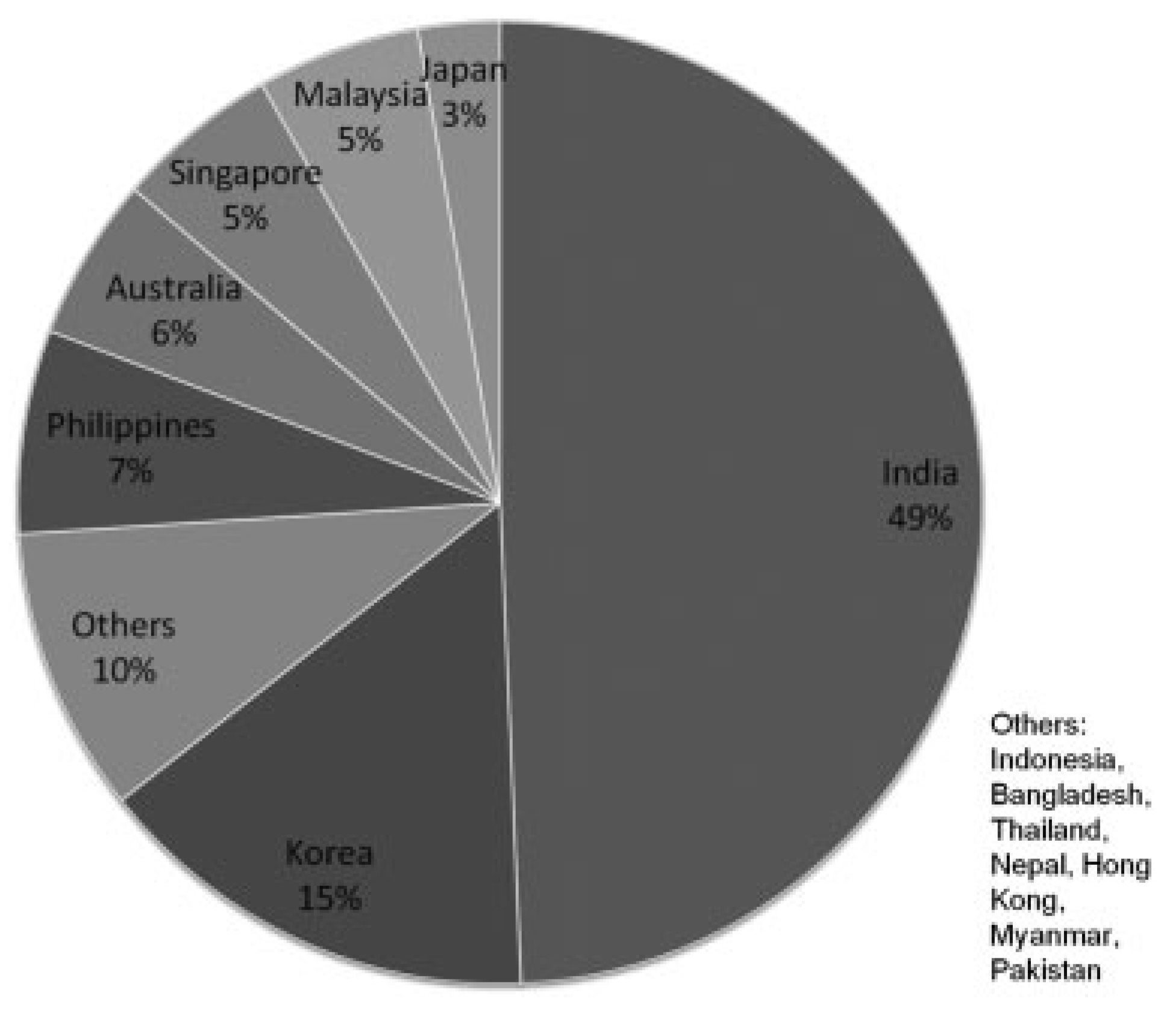

A total of 131 invitations were sent out between May 2012 and December 2012. Seven e-mail addresses were invalid at the time the survey was conducted. Of the remaining 124, 74 (59.7%) attempted the survey. Of the 74 responses, 93.2% were fully completed and 6.8% were partially completed. Responses were collected from a total of 14 countries and the breakdown of the country of practice of the participants is shown in

Figure 1. The countries with the most responses were India and Korea. Of the 74 responses, 67 (90.5%) received formal oculofacial fellowship training, 30 (48.4%) were trained outside their country of practice, 56 (75.7%) were full-time practicing oculofacial surgeons, 47 (63.5%) practiced in an institution, and 52 (70.3%) were registered members of APSOPRS.

The most common orbital surgery performed were enucleations or eviscerations (29/52 respondents, 55.8%), tumor resection (18/52, 34.6%), traumatic orbital wall fracture repair (15/52, 28.9%), and thyroid orbitopathy surgery (8/52, 15.4%).

Of all the orbital floor fractures, blowout fractures were much more commonly encountered (68.4%) compared with non-blowout fractures (31.6%). Most respondents (40/50, 80.0%) performed orbital floor fracture repair alone, and the rest (10/50, 20.0%) performed surgery with surgeons from other disciplines (plastics surgery, maxillofacial surgery, otolaryngology, and neurosurgery).

Time to Intervention and Orbital Implant

Table 1 shows the preferred time to intervention for blowout orbital floor fractures without soft tissue entrapment. The preferred time for surgical intervention was most commonly within 2 weeks (31/51, 60.8%). Meanwhile, in pediatric orbital floor blowout fractures, the preferred time for surgical intervention was most commonly immediate to 2 weeks postinjury (40/47, 85.1%).

Table 2 compares the choices of orbital implant used for orbital floor fracture repairs. The most popular implant of choice for adult and pediatric blowout fractures was the porous polyethylene (Medpor Surgical Implants; Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) implant (36/51, 70.6% and 24/49, 49.0%, respectively). However, for pediatric blowout fracture repair, the silicone sheet (22.5%) and bioresorbable implant (24.5%) were also popular choices.

Intraoperative Surgical Approach

The preferred approach for orbital floor blowout fracture was transconjunctival (via infratarsal or inferior fornix incision) (42/51, 82.4%). The remaining minority of participants preferred the subciliary approach (9/51, 17.7%). Most of the surveyed oculofacial surgeons did not use an endoscope or any intraoperative navigation for orbital floor fracture repairs (3/48, 6.3% used an endoscope and 2/48, 4.2% made use of intraoperative navigation).

Postoperative Complications and Review

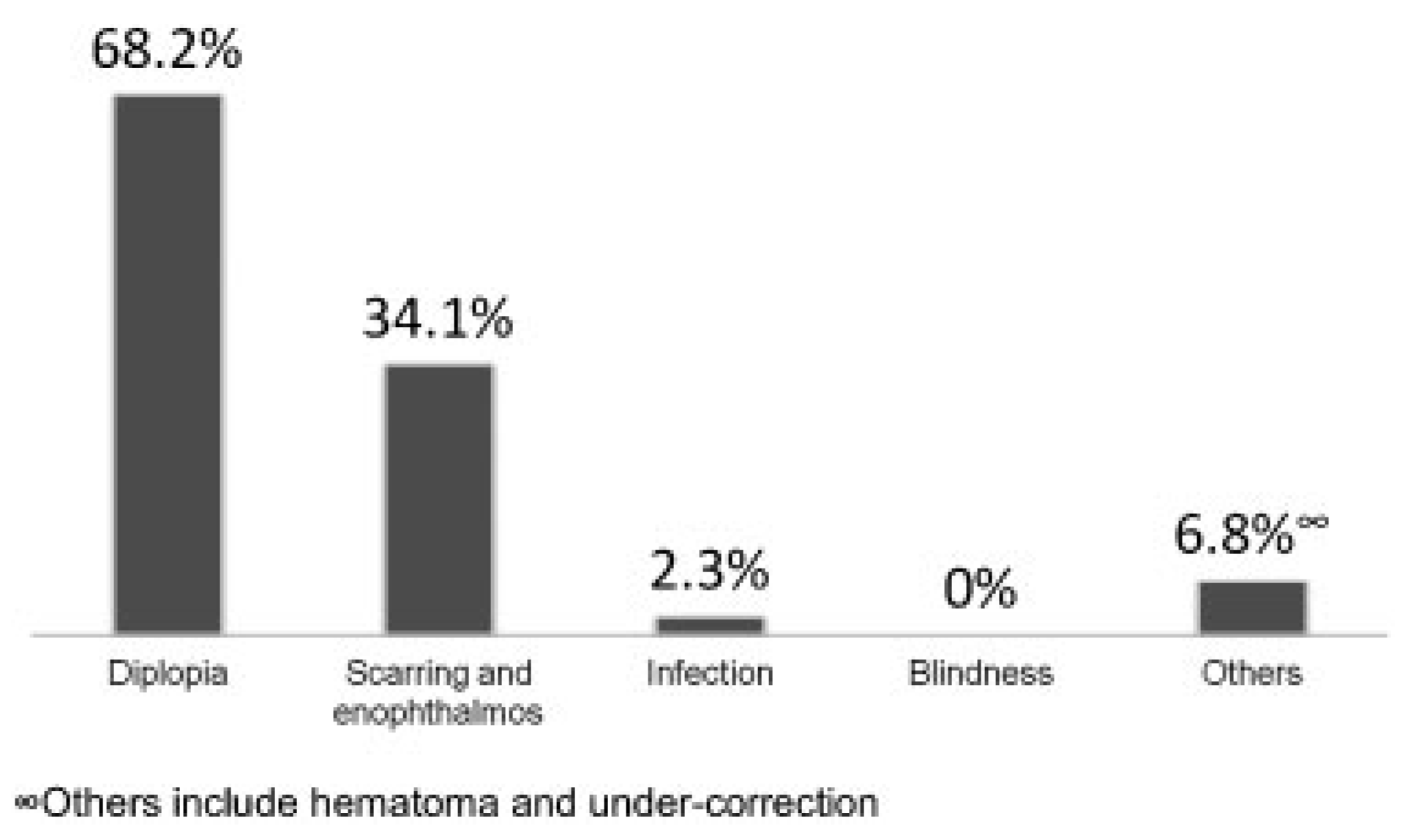

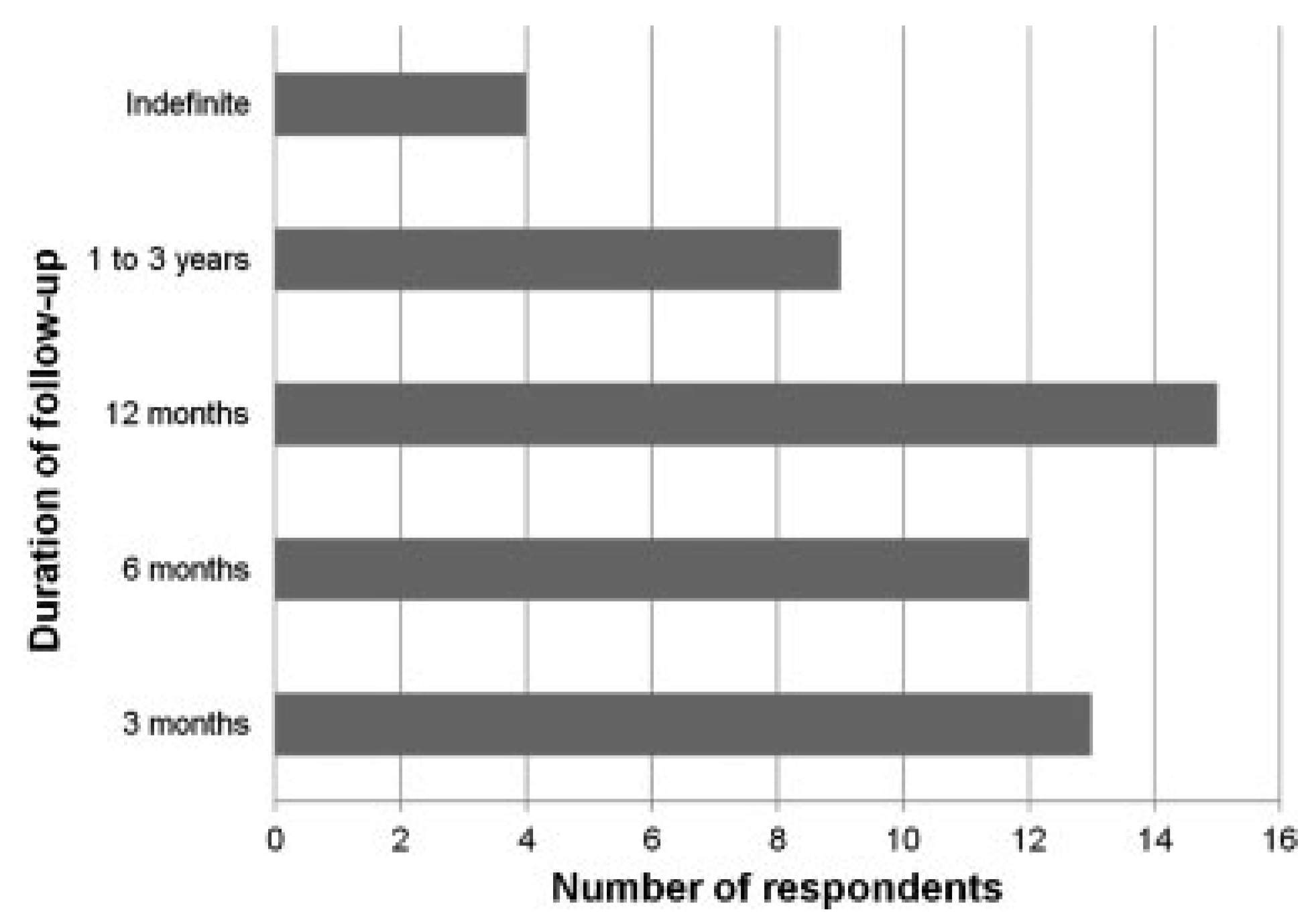

Figure 2 shows the most common complications after orbital floor fracture repair, and diplopia (30/44, 68.2%) was the most common complication. Although no participants reported blindness as the most common complication in their practice, up to 8.0% (4/49 respondents) encountered patients with blindness after orbital floor fracture repair. The duration of follow-up for uncomplicated repair of orbital floor fracture is shown in

Figure 3. Most of the oculofacial surgeons would prefer to follow-up patients for 3 to 12 months (40/49, 81.6%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first survey of oculofacial surgeons within the Asia-Pacific region although similar surveys have been performed in predominantly Caucasian countries among oral and maxillofacial surgeons [

1,

2].

Orbital floor fracture may occur in isolation or not uncommonly in combination with other injuries. However, for the purpose of this survey, the questionnaire focused on isolated orbital floor fracture and its management. Up to one-third of the respondents stated that orbital floor fracture repair was the most common orbital surgery in their practice and orbital floor blowout fracture was much more commonly encountered than non-blowout fractures. In addition, our results showed that most (80.0%) respondents operated alone without support from other disciplines. However, this may be an underestimation because the survey focused on isolated orbital floor fractures which are less complex and less frequent than cases associated with other injuries.

Our results showed a difference in the preferred time for intervention between adults and pediatric patients. The participants tended to intervene earlier for pediatric patients (immediate to 2 weeks postinjury) compared with adult patients (within 2 weeks). This may be due to the difference in the bony structure of the orbital floor between children and adults. Due to the relative elasticity of the pediatric orbital floor, exposure to blunt trauma tend to produce a “green-stick” fracture and higher risk of soft tissue entrapment. Clinically, diplopia from soft tissue entrapment may be difficult to distinguish from periorbital swelling especially in an uncooperative pediatric patient. As such, oculofacial surgeons are more cautious in the management of pediatric orbital floor fractures due to the severe consequences of ischemia and contracture if entrapped soft tissues are not released surgically early [

7,

8]. On the contrary, adult orbital floor blowout fracture tend to be larger with bony fragments depressing into the maxillary sinus. Thus, a more conservative approach is preferred, and this also allows periorbital edema and hemorrhage to subside, facilitating surgical repair. Courtney et al. published a similar survey in year 2000 comprising 187 fellows of the British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and most of the respondents preferred to delay surgery by 6 to 10 days which was consistent with our results in adult patients. However, there was no differentiation of patients’ age group and the results could be an average of both adult and pediatric patients [

1]. In 2004, Lynham et al. published a similar survey of members of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons and reported up to 51 and 90% of the respondents preferred to delay surgical intervention by 5 to 10 days and less than 14 days, respectively [

2]. The optimal time to intervene surgically is highly controversial with multiple studies showing contrasting results, which probably reflected the differences in methodology, definitions, and the wide range of presentations of patients with orbital floor blowout fractures [

6,

9,

10]. Our results showed that most oculofacial surgeons in the Asia-Pacific region preferred to delay surgical intervention for adult patients and adopted a more cautious approach for pediatric patients.

The preferred choice of implant was the porous polyethylene (Medpor) implant for both adult and pediatric patients and it has superseded earlier implants to be the most popular implant for oculofacial surgeons in the Asia-Pacific region. For pediatric patients, more than one-third of the respondents also chose to use silicone sheet and Supramid sheet implants (Supramid, S. Jackson Inc., Alexandria VA). In a 12-year retrospective study by Prowse et al., silicone sheet implants performed favorably compared with nonsilicone implants (not including porous polyethylene) in terms of complication rates such as infection, implant extrusion, and patient satisfaction [

11]. A decade ago, the silicone implant such as the Silastic implant (Silastic; Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, MI) was the most popular implant used for orbital floor fracture repair [

1]. Other popular choices included autologous bone implants, resorbable membranes, and titanium mesh [

2]. However, in the same aforementioned study, more than half of the respondents felt that the Silastic implant was not the ideal material but more modern implants such as the porous polyethylene were not yet readily available. Silicone/Silastic implant was reported to have a significant riskof persistent eyelid edema, silicone-associated tissue reaction, infection, implant migration [

12,

13] and up to 13% require implant removal [

14]. As such, the shift in choice of implant is contrasting and in slightly more than a decade, the porous polyethylene (Medpor) implant has become the most popular implant. Unlike the silicone implant, the Medpor implant’s unique lattice architecture allows fibrovascular and bone ingrowth which provides resistance against infection and extrusion [

15,

16,

17]. In addition, the Medpor implant is highly malleable which makes it easy to contour and customize to bony defects. Furthermore, Medpor can be combined with titanium for improved strength and support.

Our results showed that the preferred surgical approach for orbital floor fracture repair is the inferior transconjunctival incision (either via infratarsal or inferior fornix). Compared with the subciliary incision, the transconjunctival incision is scarless and it does not give up intraoperative surgical exposure. Often, these patients with orbital floor fractures also have concomitant injuries such as lacerations, abrasions, and other facial fractures which may require further surgical intervention. As such, a transconjunctival incision will aid in improving cosmesis for these patients. On the contrary, a transconjunctival incision may need to be combined with a lateral canthotomy for additional exposure, this requires a longer time to perform and increases the risk of ectropion [

18]. The subciliary incision has been reported to induce iatrogenic ectropion, persistent sclera show, and a visible scar [

19,

20]. Previous surveys over the past few years have indicated that infraorbital and subciliary incisions were the most popular surgical approach, with a minority (7–12% of the respondents) preferring the transconjunctival approach [

1,

2]. This may reflect a shift in the preferred surgical approach as surgeons become more comfortable with the transconjunctival approach. Alternatively, the difference in surgical approach may be attributable to difference in surgeons’ surveyed (oculofacial surgeons in our survey compared with oral and maxillofacial surgeons). The use of intraoperative endoscope and navigation was not popular among oculofacial surgeons in this region. The purchase and maintenance of this expensive equipment may be a deterring factor especially in developing countries.

Postoperatively, the most common complications encountered were diplopia and enophthalmos. Blindness is an uncommon complication but nearly 10% of the respondents encountered this devastating complication in their practice. For uncomplicated repair of orbital floor fracture, most of the respondents seemed to agree that patients should be reviewed for 3 to 12 months postoperatively.

The limitations of the study need to be mentioned. First, the response rate of our study was not high (58.3%) although a response rate of higher than 60% has been suggested as a minimum response rate required for sufficient validity of a survey [

21]. Other similar surveys had response rates ranging from 73 to 87% [

1,

2]. The lower response rate could be attributable to the wide geographical dispersion of the oculofacial surgeons targeted by the survey, language incompatibility, and limited internet access in certain countries. Despite this, the responders to our survey included participants from 14 countries across the Asia-Pacific region and our results may provide a reasonable representation of the current practices of oculofacial surgeons. Second, as the study was survey based, the validity and reliability of the responses obtained depended on the honesty of the participants. However, as the study was anonymous, it encouraged participants to provide unbiased answers including unusual answers contrary to the common practice. The management of orbital floor blowout fracture is complex and is still largely controversial despite well-conducted clinical trials and studies. Furthermore, recommendations from clinical trials may not reflect the current “flavor” of clinical practice. As such, a survey of surgeons’ preferences may be a better representation of evidence-based medicine in clinical practice. Currently, we are planning to set up an ophthalmic trauma registry in a tertiary ophthalmology referral unit in Singapore. This registry would facilitate future prospective studies on oculofacial trauma including orbital floor blowout fractures.

In conclusion, we reported the results of the first survey of oculofacial surgeons within the Asia-Pacific region on the management of orbital floor blowout fractures. Compared with previous comparable surveys (from year 2000 to 2004), the duration to surgical intervention remained comparable but there is a contrasting change in preferred surgical approach and choice of orbital implant. Postoperative diplopia was the most commonly encountered complication and most oculofacial surgeons preferred to follow-up their patients regularly (for uncomplicated repair of orbital floor fracture) for up to 12 months.