Abstract

Temporomandibular joint ankylosis (TMJA) is a severe disorder described as an intracapsular union of the disc-condyle complex to the temporal articular surface with bony fusion. The management of this disability is challenging and rarely based on surgical and rehabilitation protocols. We describe the treatment in two young adults affected by Goldenhar syndrome and Pierre Robin sequence with reankylosis after previous surgical treatments. There are three main surgical procedures for the treatment of TMJA: gap arthroplasty, interpositional arthroplasty, and joint reconstruction. Various authors have described reankylosis as a frequent event after treatment. Treatment failure could be associated with surgical errors and/or inadequate intensive postoperative physiotherapy. Surgical treatment should be individually tailored and adequate postoperative physiotherapy protocol is mandatory for success.

Temporomandibular joint ankylosis (TMJA) is a severe disorder described as an intracapsular union of the disc-condyle complex to the temporal articular surface with bony fusion. This leads to a restriction or complete immobility of mandibular movements and mouth opening. Trauma is the main cause of ankylosis. The limited mouth opening determines functional alteration and disability, esthetic deformity, and severe psychological distress [1].

TMJA in childhood is a condition that must be diagnosed and treated promptly because mandibular growth can be altered and could be the cause of facial asymmetry.

Kazanjian [2] classified TMJA as true when there are osseous or fibrous adhesions between the surface of TMJ and as false because of other pathologies not directly related to the joint.

Rowe classified TMJA according to the location of the problem (intra/extra articular), type of tissues involved (osseous/fibrous/both), and the extent of fusion (complete/incomplete) [3].

Management of TMJA is difficult, and there is no surgical protocol. The following three main surgical procedures have been proposed for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) release and reconstruction: gap arthroplasty, interpositional arthroplasty, and joint reconstruction.

Clauser et al. describe the surgical treatment and related follow-up in two patients affected by congenital craniofacial malformation with recurrence of ankylosis after previous surgical treatments.

Patients and Methods

We describe the treatment in two young adults affected by Goldenhar syndrome and Pierre Robin sequence with reankylosis after previous surgical treatments.

Preoperative assessment in each patient included clinical history, imaging (panoramic X-ray, computed tomographic [CT] scan and magnetic resonance imaging), laboratory test, complete physical examination, TMJ examination including maximal incisal opening (MIO) before and after surgery, and mandibular movements.

The Goldenhar patient, a 28-year-old woman, had undergone 33 operations in different centers for left TMJA (Figure 1). Following left costochondral graft (CCG), cartilage reabsorption had occurred. Ankylosis with severe limited mouth opening started 11 years after vitallium endoprosthesis placement. Clinical evaluation revealed 9-mm MIO, no lateral movements, and protrusion with poor oral hygiene and associated depression. Pain and muscle contracture were also present. Surgical planning included the following: left ankylotic bone removal, cleaning of the prosthesis, and forced mouth opening. The operation was performed under general anesthesia with nasal fiber-optic–assisted intubation.

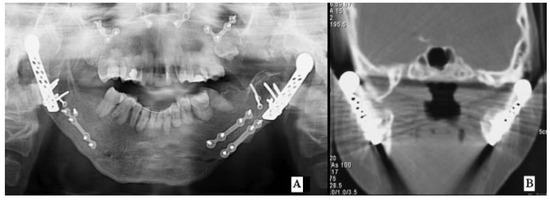

Figure 1.

(A) Goldenhar’s preoperative orthopantomogram. Bilateral temporomandibular joint ankylosis. (B) Preoperative coronal CT scan with right prosthesis dislocation. CT, computed tomography.

The TMJ was approached via a preauricular incision with wide exposure of the temporomandibular joint and the ankylotic block. The bony mass was removed by means of secondary gap arthroplasty with temporalis muscle flap (TMF) (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4). The Pierre Robin sequence patient was a 27-year-old woman with bilateral TMJA who had many operations in different centers. Five years after positioning of bilateral condilar prosthesis she developed left ankylosis with right vitallium endoprostheses dislocation. MIO was 13 mm with no lateral and protrusion movements, very poor oral hygiene (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Postoperative panoramic X-ray. Release of ankylotic bone and stabilization after right semivertical osteotomy.

Figure 3.

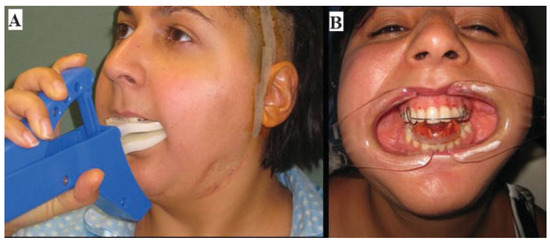

Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) maximum interincisal opening after 2-year follow-up.

Figure 4.

Postoperative physiotherapy. (A) Therabite. (B) Andreasen type monobloc activator.

Figure 5.

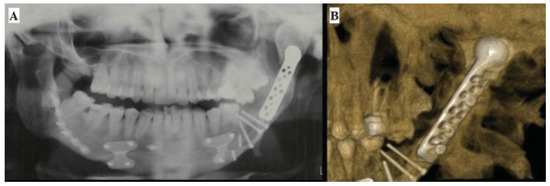

Pierre Robin sequence. (A) Left ankylotic mass with prosthesis implication. (B) Three-dimensional CT reconstruction of the left ankylosis. CT, computed tomography.

Following fiber-optic–assisted intubation, the patient underwent removal of the right prosthesis, semivertical ramus osteotomy, and a strip of TMF rotation. On the left side, a bony ankylosis removal was performed, with preservation of the prosthesis and interposition of TMF (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8). In each patient, suction drains were placed to avoid edema and a pressure dressing was applied.

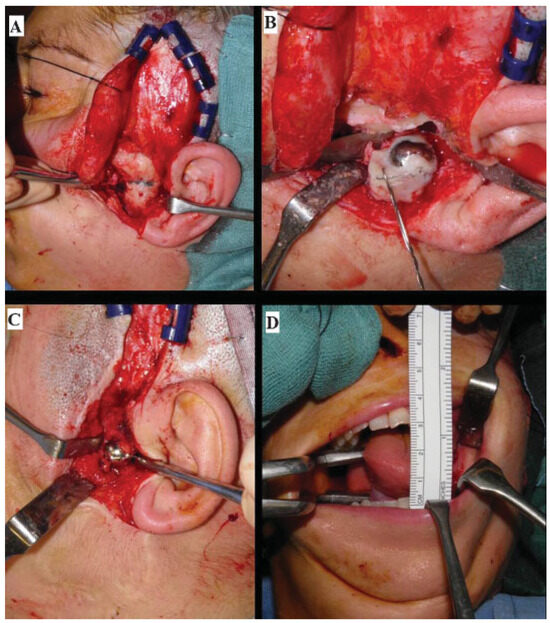

Figure 6.

Postoperative orthopantomogram. Gap after bony ankylotic block resected (black arrow).

Figure 7.

Intraoperative views. (A) Preauricular incision and TMJ ankylosis. (B) The gap after resection of ankylotic mass. (C) Interpositional arthroplasty using temporalis fascia and muscle. (D) Forced mouth opening with distraction of the muscle and tissue. TMJ, temporomandibular joint.

Figure 8.

(A) Severe restricted mouth opening. (B) Mouth opening after 2-year follow-up.

Forced mouth opening was performed during surgery, and intensive early and prolonged physiotherapy in accordance with our protocol started immediately after surgery.

The patients were initially put on a soft diet and were gradually moved to a solid meal the next week.

Physiotherapy was performed for at least 6 months after the operation to reduce recurrence of ankylosis in and limitation of mouth opening and movements. Authors’ protocol consisted an early manual active and passive physiotherapy 10 minutes 4 times a day and 1 week postoperatively the use of intraoral devices (TheraBite; Atos Medical Ab, Hörby, Sweden, spreaders, etc.) for at least 6 months.

Results

No complications such as infections, hematomas, or facial nerve involvement were observed after surgery. The maximal mouth opening achieved intraoperatively was 30 mm. MIO remained stable 6 months after surgery. The last follow-up (2 years) confirmed the results with no recurrence of ankolysis. Oral functions including speaking, eating, chewing, hygiene, as well as improved quality of life were regained.

Discussion

TMJA in childhood is a condition that must be diagnosed and promptly treated.

Mandibular hypomobility may be responsible for problematic airways maintenance, malnutrition and delayed growth, negative impact on speech development, limited access for oral hygiene and dental care, muscle contraction, and atrophy [4].

Mandibular growth in children can be altered in TMJA and could be the cause of facial asymmetry. When ankylosis is unilateral there may also be unilateral hypoplasia of the mandible and chin deviation on the affected side; when bilateral, it results in retrognathia, mandibular alveolar protrusion, open bite, bird-face appearance, and hypertrophic and thick coronoid process [5].

The main cause of ankylosis is trauma followed, in order of frequency, by local or systemic infection, such as ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis.2 Ankylosis can also be a result of TMJ surgery [6,7].

In trauma, age and type of fracture influence the occurrence of TMJA. Ankylosis is more likely to develop in childhood given the greater potential for growth in the child as compared with the adult. Intracapsular condylar fracture is the most dangerous cause of ankylosis [8,9,10].

Differential diagnosis should be based on systemic muscle pathology, head and neck trauma, infection (e.g., trismus for tetanus infection), hard and soft tissue pathologies such as myositis ossificans [11], neurologic diseases, pure muscular contracture or scarring of masticatory muscles after radiotherapy, and coronoid hyperplasia.

In 1986, Sawhney [12] proposed a classification of TMJA based on X-ray films; however, with the development of CT scan new classifications were reported with the purpose of improving evaluation of the degree and type of ankylosis to plan the best possible intervention.

Aggarwal et al. [13] and Ferretti et al. [14] divided bony ankylosis into following two types according to the morphology of the ankylosed joint on coronary CT: Type M, partial joint fusion presenting with medial dislocation of condylar head and fusion between the lateral ramus stump and the articular fossa; Type N, total joint fusion manifesting as no medial dislocation of condylar head and fusion between the total condyle and the glenoid fossa [13].

In the past few years, Yan et al. [15] described the relationship between mouth opening and computerized tomographic features of posttraumatic TMJA, and He et al. [8] described four types of traumatic ankylosis on the basis of coronal CT scan of 124 joints.

Three main surgical procedures have been proposed for TMJ release and reconstruction, namely, gap arthroplasty, interpositional arthroplasty, and joint reconstruction.

The advantages of gap arthroplasty are its simplicity and short operating time, but the disadvantages include shortening of the mandibular ramus, open bite, and increased risk of recurrence of ankylosis [6,7,16].

In interpositional arthroplasty, different materials have been described: skin, dermis, TMF, buccal fat pad [17],cartilage and CCG as autogenous tissue and acrylic, proplast-Teflon and silastic as alloplastic materials [17,18].

According to Rowe, interpositional substance placed between the bony surface reduces the possibility of reankylosis [4].

Unpredictable reabsorption and donor-site morbidity as well as foreign body reaction should, however, be taken into consideration [2,6,19,20].

Moreover, some conditions such as multiple TMJ operation, severe heterotopic ossification, and fibrosis of soft tissue increase the risk of reankylosis [21]. In heterotopic ossification, pluripotent cells are induced to differentiate into fibroblasts, chondroblasts, and osteoblasts. This leads to a partial or total reankylose of the articulation with an increase in pain and progressive limited mouth opening [17].

Dolwick and Aufdemorte suggested the early removal of silastic sheet [22].

Singh et al. described a successful management in treatment of 10 TMJA through use of buccal fat pad as an interpositional graft [17].

Because of its proximity to the surgical area, TMF is the most commonly used interposition material [1,23,24,25,26,27]. Fibrosis and scar contracture of the temporalis muscle and depression in temporal region and chronic headache have been described [26,28].

According to Vasconcelos et al. there is no consensus regarding the ideal interpositional graft [6]. When the TMJ is anatomically and functionally impaired, joint reconstruction is suggested. CCG, clavicular graft, coronoid process, iliac crest, and metatarsus can be used.

Because of its growth, biocompatibility, workability, great adaptability to the glenoid fossa, and anatomical similarity to the condyle, CCG is considered the best option for TMJ reconstruction [6,29].

In using alloplastic materials, the advantages are as follows: analog anatomy to real joint, absence of donor-site morbidity, possibility to restore the vertical dimension, reduction in surgery time, and a lower risk of recurrent ankylosis [6,30]. Foreign body reaction, mobility of the implant with displacement, and implant fracture have been reported [6,29,31].

According to Güven, surgical treatment should be chosen according to the extent and type of ankylosis, patient age, onset and time of surgery, and whether the ankylosis is unilateral or bilateral [5].

Nogueira and Vasconcelos described that the rate of facial nerve injury (31%) was related to the complexity of surgery. This is caused by the type of ankylosis, and the nerve lesions were shown to be of a temporary nature (after 3 months all the patients displayed normal function) [32].

Even if treatment of this condition is surgical, adequate postoperative physiotherapy is required. Physiotherapy after surgery is necessary to disrupt and prevent adhesion, soft tissue contractions, and to stimulate normal muscle function [33,34].

According to Su-Gwan early mobilization could be the cause of bleeding and hematoma resulting in delayed healing [35].

Conclusion

Management of TMJA is difficult as no standardized surgical protocols have been suggested. Failure and reankylosis are common. In pediatric age, the aim of surgery is to recover morphology and function with normal growth, appropriate speech development, dental occlusion, and normal development of the facial skeleton.

The best treatment is yet to be found because no consensus in the literature has been established. Surgical treatment must be tailor-made for each patient and adequate postoperative Rehabilitative Physiotherapy Protocol (RPP) is necessary to achieve success.

Treatment of this condition is surgical. However, in our experience the outcome depends on an adequate postoperative RPP. The therapy focuses on maintaining or improving the mouth opening achieved at the time of surgery. Prolonged postoperative physical therapy is crucial for success. After surgery and physiotherapy, accurate monitoring of the patient is mandatory to prevent recurrence of ankylosis and to improve the initial interincisal opening obtained [36].

The success of surgical treatment has been related to the amount of immediate postoperative mouth opening. RPP includes passive and active exercise and self-distraction technique as part of a home program. The therapy focuses on maintaining or improving the mouth opening achieved at the time of surgery. Prolonged postoperative physical therapy from a minimum of 6 months to 1 year is crucial for success.

In pediatric age, patient and family must all be educated as to its importance for long-term results. Different devices can be used for active and passive physiotherapy such as bite block, removable activator appliances, spatulas, springs, tweezers, splints, wedges, and TheraBite.

Our postoperative RPP is as follows: positioning mouth opener immediately after surgery for 3 days, after the 3rd day the patient starts with self-manual physiotherapy and TheraBite exercise for approximately 10 minutes, 10 times a day. Orthopedic treatment during the night with Andresen Type Monobloc Activator device is part of the protocol. Starting from the 6th week we suggest mandibular exercise with a physiotherapist twice a week. Mandibular exercise, intraoral device and TheraBite must be continued for not less than 1 year to maintain and improve the mouth opening obtained at the time of surgery and to avoid recurrence of ankylosis.

Forced mouth opening and muscle/tissue stretching under sedation and local anesthesia the day after surgery is a part of the protocol.

The safest technique for securing the airway could be a basal fiber-optic–assisted intubation with the patient awake and under local anesthesia.

Treatment failure may be associated with surgical errors and/or inadequate intensive physiotherapy. Because the stomatognathic system represents a dynamic and evolving condition, biologic equilibrium is required for normal function and morphology.

References

- Guruprasad, Y.; Chauhan, D.S.; Cariappa, K.M. A Retrospective Study of Temporalis Muscle and Fascia Flap in Treatment of TMJ Ankylosis. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2010, 9, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanjian, V.H. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis with mandibular retrusion. Am J Surg 1955, 90, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, N.L. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1982, 27, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Galiè, M.; Consorti, G.; Tieghi, R.; et al. Early surgical treatment in unilateral coronoid hyperplasia and facial asymmetry. J Craniofac Surg 2010, 21, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güven, O. A clinical study on temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children. J Craniofac Surg 2008, 19, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, B.C.; Porto, G.G.; Bessa-Nogueira, R.V.; Nascimento, M.M. Surgical treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis: followup of 15 cases and literature review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2009, 14, E34–E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaban, L.B.; Perrott, D.H.; Fisher, K. A protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990, 48, 1145–1151, discussion 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Yang, C.; Chen, M.; et al. Traumatic temporomandibular joint ankylosis: our classification and treatment experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011, 69, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E., III. Complications of mandibular condyle fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998, 27, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, M.A.; Oliveira, J.X.; Cavalcanti, M.G. Computed tomography imaging findings of simultaneous bifid mandibular condyle and temporomandibular joint ankylosis: case report. Braz Dent J 2007, 18, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundlach, K.K. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2010, 38, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawhney, C.P. Bony ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint: follow-up of 70 patients treated with arthroplasty and acrylic spacer interposition. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986, 77, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Berry, M.; Bhargava, S. Bony ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint: a computed tomography study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1990, 69, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, C.; Bryant, R.; Becker, P.; Lawrence, C. Temporomandibular joint morphology following post-traumatic ankylosis in 26 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005, 34, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, E.; An, J. The relationship between mouth opening and computerized tomographic features of posttraumatic bony ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011, 111, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, H.; Miyamoto, H.; Ogi, N.; Kurita, K.; Goss, A.N. The effect of gap arthroplasty on temporomandibular joint ankylosis: an experimental study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001, 30, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Dhingra, R.; Sharma, B.; Bhagol, A.; Kumar, P. Retrospective analysis of use of buccal fat pad as an interpositional graft in temporomandibular joint ankylosis: preliminary study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011, 69, 2530–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitroulis, G. The interpositional dermis-fat graft in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004, 33, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolford, L.M.; Pitta, M.C.; Reiche-Fischel, O.; Franco, P.F. TMJ Concepts/ Techmedica custom-made TMJ total joint prosthesis: 5-year follow-up study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tideman, H.; Bosanquet, A.; Scott, J. Use of the buccal fat pad as a pedicled graft. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1986, 44, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egemen, O.; Ozkaya, O.; Filinte, G.T.; Uscetin, I.; Akan, M. Two-stage total prosthetic reconstruction of temporomandibular joint in severe and recurrent ankylosis. J Craniofac Surg 2012, 23, e520–e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolwick, M.F.; Aufdemorte, T.B. Silicone-induced foreign body reaction and lymphadenopathy after temporomandibular joint arthroplasty. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1985, 59, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omura, S.; Fujita, K. Modification of the temporalis muscle and fascia flap for the management of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996, 54, 794–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, A.W.; Shepherd, J.P. Fascia lata interpositional arthroplasty in the treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis caused by psoriatic arthritis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992, 21, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, L.; Curioni, C.; Spanio, S. The use of the temporalis muscle flap in facial and craniofacial reconstructive surgery. A review of 182 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1995, 23, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, M.; Badri, A.; Moharamnejad, N. Treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis: gap and interpositional arthroplasty with temporalis muscle flap. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009, 13, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrel, M.A.; Kaban, L.B. The role of a temporalis fascia and muscle flap in temporomandibular joint surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990, 48, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitroulis, G. The interpositional dermis-fat graft in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004, 33, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntosh, R.B. The use of autogenous tissues for temporomandibular joint reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000, 58, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Hensher, R.; McLeod, N.; Kent, J. Reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint autogenous compared with alloplastic. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002, 40, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speculand, B.; Hensher, R.; Powell, D. Total prosthetic replacement of the TMJ: experience with two systems 1988-1997. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000, 38, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, R.V.; Vasconcelos, B.C. Facial nerve injury following surgery for the treatment of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2007, 12, E160–E165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- House, J.W.; Brackmann, D.E. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985, 93, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qudah, M.A.; Qudeimat, M.A.; Al-Maaita, J. Treatment of TMJ ankylosis in Jordanian children—a comparison of two surgical techniques. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2005, 33, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su-Gwan, K. Treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis with temporalis muscle and fascia flap. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001, 30, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, N.N.; Kalra, R.; Shetye, S.P. New protocol to prevent TMJ reankylosis and potentially life threatening complications in triad patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012, 41, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the author. The Author(s) 2013.